Concatenation vs. Coalescent Models in Phylogenomics: Navigating Introgression and ILS for Accurate Species Tree Inference

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of concatenation and multispecies coalescent (MSC) approaches for phylogenetic inference, with a special focus on datasets impacted by introgression and incomplete lineage sorting (ILS).

Concatenation vs. Coalescent Models in Phylogenomics: Navigating Introgression and ILS for Accurate Species Tree Inference

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of concatenation and multispecies coalescent (MSC) approaches for phylogenetic inference, with a special focus on datasets impacted by introgression and incomplete lineage sorting (ILS). Aimed at researchers and bioinformaticians, we explore the foundational principles of both methods, detail their application workflows, and address key challenges like model violation and gene tree estimation error. Through empirical case studies and statistical validation frameworks, we demonstrate why the MSC model often outperforms concatenation in complex evolutionary scenarios. The review concludes with practical guidance for method selection and discusses the implications of these phylogenomic advancements for tracing the evolutionary origins of biomedically relevant traits and genes.

The Roots of Discordance: Understanding Gene Tree Conflict, ILS, and Introgression

The central challenge in modern phylogenomics lies in reconciling the differences between gene trees and species trees. A gene tree represents the evolutionary history of a single gene or locus, based on the genetic sequences of different individuals or species. In contrast, a species tree represents the actual evolutionary history of the species themselves—the true pattern of lineage splitting and descent over time [1]. The paradox emerges from the widespread observation that these trees are often incongruent, meaning they display different branching patterns. This incongruence presents a fundamental challenge for phylogeneticists who must choose analytical approaches that can accurately recover species relationships from conflicting genetic signals.

The debate between two primary methodological frameworks—concatenation versus multispecies coalescent (MSC) models—forms the core of contemporary discussions on addressing this paradox. Concatenation approaches combine data from all genes into a single "supermatrix" and infer one phylogenetic tree, implicitly assuming all genes share the same evolutionary history. Conversely, MSC approaches explicitly model gene tree variation resulting from biological processes like incomplete lineage sorting (ILS), providing a more sophisticated but computationally demanding framework for species tree inference [2]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these competing methodologies, evaluating their performance, underlying assumptions, and applicability to empirical phylogenomic data sets.

Biological Foundations of Incongruence

Primary Mechanisms Creating Gene Tree Discordance

Gene tree-species tree incongruence arises from several distinct biological processes that cause individual genes to have evolutionary histories that diverge from the overall species history.

Incomplete Lineage Sorting (ILS): ILS occurs when multiple gene lineages persist through successive speciation events. This happens when the genetic polymorphisms in an ancestral population are not fully sorted into distinct monophyletic lineages by the time subsequent speciation occurs [1] [3]. The probability of ILS increases when the time between speciation events is short relative to the population size, creating a situation where gene trees may reflect the random sorting of ancestral polymorphism rather than species divergence history. ILS is considered one of the most common biological sources of gene tree variation [2].

Hybridization and Introgression: These processes involve genetic exchange between previously separated lineages, typically through hybridization. When individuals from different species breed, their offspring contain genetic material from both parental species [1]. Consequently, different genes in hybrid genomes reflect different evolutionary histories—some genes tracing back to one parent species, others to the second parent species. This creates strong incongruence as randomly selected genes may tell conflicting stories about species relationships.

Horizontal Gene Transfer (HGT): Particularly prominent in bacterial evolution, HGT involves the direct transfer of genetic material between distantly related species, bypassing vertical inheritance [3]. Genes acquired through HGT carry the evolutionary history of their donor species rather than the recipient species, creating dramatic discordance between the transferred gene's phylogeny and the species tree.

Gene Duplication and Loss (Hidden Paralogy): When gene duplication events occur, creating paralogous copies, and subsequent gene loss eliminates some copies, the resulting gene tree may reflect this complex history of duplication and loss rather than species relationships [3] [4]. If researchers inadvertently include paralogous sequences in their analyses without proper identification, this "hidden paralogy" can produce strongly supported but misleading phylogenetic signals.

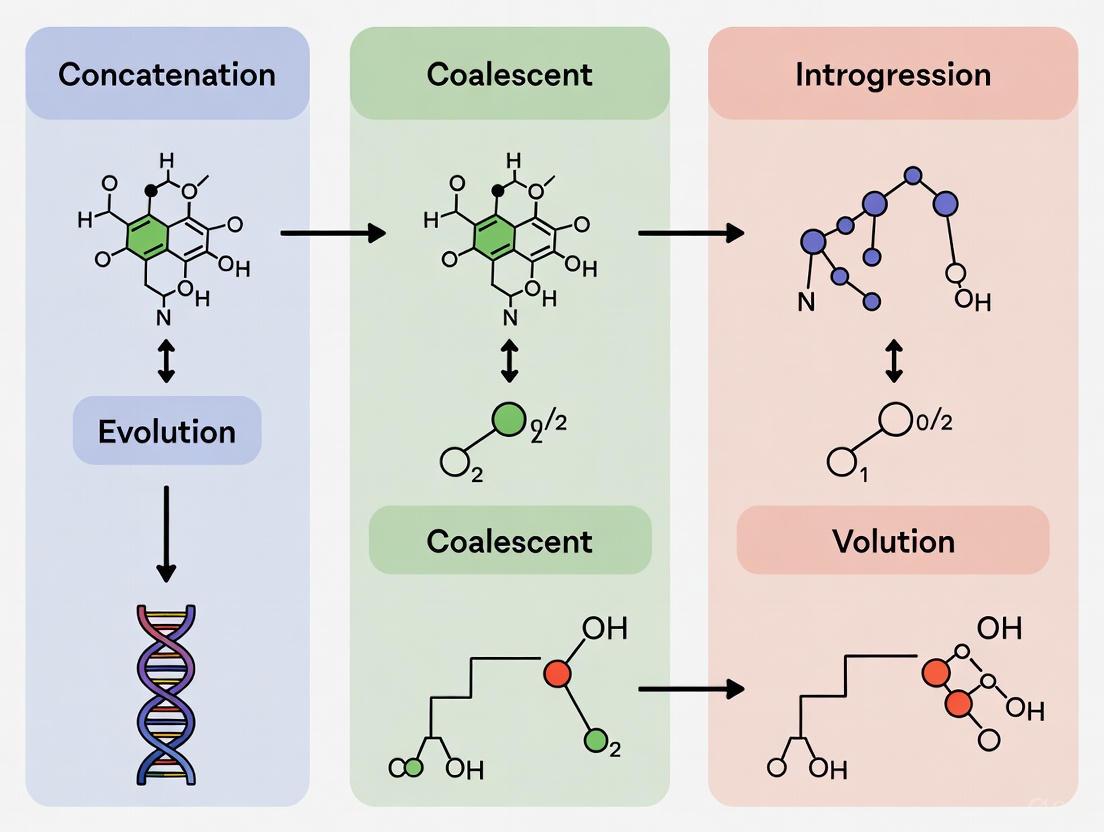

Visualizing the Paradox

The following diagram illustrates the primary biological processes that create discordance between gene trees and the species tree.

Methodological Frameworks: Concatenation vs. Coalescent

Core Principles and Assumptions

The concatenation and multispecies coalescent approaches differ fundamentally in how they handle multi-locus data and model evolutionary processes.

Concatenation Framework: The concatenation method combines sequence alignments from all genes into a single supermatrix, from which a unified phylogenetic tree is inferred. This approach implicitly assumes that all genes share the same underlying topology (topological congruence) and evolutionary history [2]. The model essentially treats the entire dataset as evolving from a single tree, ignoring the potential for gene tree heterogeneity due to biological processes like ILS. Proponents of concatenation sometimes argue that it benefits from increased statistical power when gene tree variation is minimal or primarily caused by estimation error rather than biological processes [2].

Multispecies Coalescent Framework: The MSC model explicitly accounts for gene tree variation by modeling the coalescent process within species lineages. Rather than assuming a single tree for all genes, the MSC estimates the species tree from the distribution of gene trees, incorporating the expected discordance due to ILS [2]. The model treats loci as independent estimates of the species tree, conditional on the species tree and population genetic parameters, thereby accommodating the inherent stochasticity of gene lineage sorting within diverging populations.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The table below summarizes key performance metrics for concatenation and coalescent approaches based on empirical and simulation studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Concatenation vs. Coalescent Approaches

| Performance Metric | Concatenation Approach | Multispecies Coalescent Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Model Rejection Rates | Rejected for ~38% of loci in empirical studies [2] | Rejected for ~11% of loci (significantly lower than concatenation) [2] |

| Behavior with High ILS | Inconsistent under some tree space regions with high ILS [2] | Consistent estimator even in high ILS conditions [2] |

| Effect on Branch Length Estimates | Underestimates temporal duration in incongruent regions; overestimates in congruent regions [5] | More accurate estimation of branch lengths by accounting for gene tree variation [5] |

| Divergence Time Estimation | Biased by topological incongruence; erroneous estimation of substitution numbers [5] | Better accounts for gene tree variation, improving divergence time estimates [5] |

| Computational Demand | Lower computational requirements | Higher computational demands due to integration over gene trees |

Impact on Divergence Time Estimation

The choice between methodological frameworks significantly impacts divergence time estimates. When topological incongruence between gene trees and the species tree is not accounted for in concatenation approaches, the temporal duration of branches in affected regions of the species tree is underestimated, while the duration of other branches is considerably overestimated [5]. This bias stems from erroneous estimation of the number of substitutions along branches in the species tree, modulated by assumptions inherent to divergence time estimation such as those relating to the fossil record or among-branch substitution rate variation [5].

Analyses selecting only loci with gene trees topologically congruent with the species tree, or only branches from each gene tree that are congruent, demonstrate that the effects of topological incongruence can be reduced. However, even with these selective approaches, error in divergence time estimates persists due to temporal incongruences between divergence times in species trees and gene trees [5].

Empirical Evidence and Case Studies

Model Fit Across the Tree of Life

Large-scale comparisons across 47 phylogenomic datasets collected from across the tree of life provide compelling empirical evidence regarding model performance. Tests for substitution models and the concatenation assumption of topologically congruent gene trees suggest that poor fit of substitution models (rejected by 44% of loci) and concatenation models (rejected by 38% of loci) is widespread [2]. A substantial violation of the concatenation assumption of congruent gene trees is consistently observed across six major groups: birds, mammals, fish, insects, reptiles, and other invertebrates [2].

In contrast, among loci adequately described by a given substitution model, the proportion rejecting the MSC model is significantly lower at approximately 11% [2]. Bayesian model validation and comparison strongly favor the MSC over concatenation across all datasets, with the concatenation assumption of congruent gene trees rarely holding for phylogenomic datasets with more than 10 loci [2].

Biological Realism and Model Assumptions

The superior performance of MSC models stems from their more realistic representation of evolutionary processes. Concatenation approaches oversimplify the complexity inherent in species diversification by ignoring biological phenomena like deep coalescence, hybridization, recombination, and gene duplication/loss that are commonly observed during species history [2]. The fundamental motivation for MSC models extends beyond accommodating gene tree variation to recognizing the conditional independence of loci in the genome, wherein recombination and random drift render gene tree topologies and branch lengths independent of one another, conditional on the species tree [2].

The Challenge of Model Violations

Both concatenation and coalescent approaches face challenges when their underlying assumptions are violated. A recent study using tetrapod mitochondrial genomes to control for biological sources of variation (due to their haploid, uniparentally inherited, non-recombining nature) found that levels of discordance among mitochondrial gene trees were comparable to those found in studies assuming biological variation [6]. More complex and biologically realistic sequence evolution models, including covarion models to incorporate site-specific rate variation across lineages (heterotachy) and partitioned models to incorporate variable evolutionary patterns by codon position, improved model fit but still inferred highly discordant mitochondrial gene trees [6]. This "Mito-Phylo Paradox" suggests that significant gene tree discordance in empirical data may persist even with improved models, raising questions about whether this variation could be biological in nature after all [6].

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Considerations

Standard Phylogenomic Workflow

The following diagram outlines a comprehensive workflow for phylogenomic analysis that incorporates both concatenation and coalescent approaches, enabling methodological comparison.

Key Methodological Steps

Orthology Assessment: Proper identification of orthologous genes is critical, as inclusion of paralogous sequences can create strong but misleading phylogenetic signals. Hidden paralogy represents a significant source of incongruence that can mislead both concatenation and coalescent analyses if not properly addressed [3] [4].

Substitution Model Selection: Selection of appropriate substitution models for each locus or partition significantly impacts gene tree estimation. Poorly fitting models can generate gene tree error that masquerades as biological discordance [6]. Methods like PartitionFinder can be used to select optimal partitioning schemes and substitution models.

Gene Tree Estimation with Confidence Assessment: Individual gene trees should be estimated with methods that account for site-specific rate variation and other complexities. Bootstrap resampling (BS) or posterior probabilities (PP) provide measures of confidence for each gene tree [2].

Species Tree Inference Under Both Frameworks: Implementing both concatenation and MSC analyses enables direct comparison of resulting topologies and branch lengths. Commonly used software for coalescent analysis includes *BEAST, ASTRAL, and SVDquartets, while RAxML and IQ-TREE are frequently used for concatenation analyses [2].

Model Comparison and Validation: Statistical tests for model adequacy, including posterior predictive simulation, Bayes factors, and topological tests, help determine which framework provides a better fit to the empirical data [2].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Phylogenomic Analysis

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence Alignment | MAFFT, MUSCLE, PRANK | Multiple sequence alignment of loci | Different algorithms handle indels and evolutionary events differently |

| Substitution Model Selection | PartitionFinder, ModelTest | Identify best-fit nucleotide substitution models | Critical for reducing systematic error in gene tree estimation [6] |

| Gene Tree Inference | RAxML, IQ-TREE, MrBayes | Estimate phylogenetic trees for individual loci | Account for rate heterogeneity among sites; assess confidence with bootstrapping |

| Concatenation Analysis | RAxML, ExaBayes, PhyloBayes | Infer species trees from concatenated supermatrices | Assumes topological congruence across all genes [2] |

| Coalescent Analysis | *BEAST, ASTRAL, SVDquartets | Estimate species trees accounting for gene tree discordance | Explicitly models ILS; more computationally intensive [2] |

| Divergence Time Estimation | BEAST2, MCMCTree | Estimate temporal dimensions of phylogenies | Require fossil calibrations or other temporal constraints [5] |

| Gene Tree Discordance Analysis | PhyParts, DiscoVista, DensiTree | Quantify and visualize conflict among gene trees | Identifies regions of species tree with high incongruence [5] |

| Introgression Tests | D-statistics, PhyloNet, HyDe | Detect and quantify hybridization and introgression | Essential for identifying non-tree-like evolutionary processes |

The empirical evidence strongly favors the multispecies coalescent framework over concatenation for species tree inference in most phylogenomic contexts. The MSC model consistently demonstrates better fit to empirical data across diverse taxonomic groups, with significantly lower rejection rates (~11% versus ~38% for concatenation) [2]. The key advantage of coalescent methods lies in their biological realism—they explicitly account for the gene tree variation expected under population genetic processes like incomplete lineage sorting, rather than treating it as noise or error [2].

Nevertheless, the complexity of genomic evolution ensures that no single method is universally optimal. The most robust phylogenetic inferences emerge from approaches that: (1) implement both concatenation and coalescent analyses to assess congruence and conflict; (2) utilize high-quality data with appropriate model selection to minimize estimation error; and (3) acknowledge and investigate biological sources of discordance rather than assuming they represent analytical artifacts. As phylogenomic datasets continue growing in size and taxonomic breadth, methods that simultaneously account for multiple sources of incongruence—ILS, introgression, and horizontal transfer—will become increasingly essential for reconstructing the evolutionary history of life.

Incomplete lineage sorting (ILS) is a fundamental evolutionary phenomenon wherein the genealogical history of a gene differs from the species tree due to the retention of ancestral genetic polymorphisms across successive speciation events [7]. Also termed hemiplasy or deep coalescence, ILS occurs when multiple alleles of a gene exist in an ancestral population and are distributed unevenly among daughter species during rapid speciation, creating discordance between gene trees and species trees [7]. Understanding ILS is critical for phylogenomic research, particularly in distinguishing between true species relationships and gene tree discordance caused by ancestral polymorphism retention. The prevalence of ILS is heightened in lineages with large effective population sizes and short inter-speciation intervals, such as in hominids and various plant species [7] [8].

This guide objectively compares two primary analytical frameworks for handling ILS: the concatenation approach, which assumes a single underlying topology for all genes, and the multispecies coalescent (MSC) model, which explicitly accounts for gene tree variation arising from ILS. We evaluate their performance using empirical data, statistical tests, and experimental protocols to provide researchers with evidence-based recommendations for phylogenomic inference.

Conceptual Framework of ILS

Mechanisms and Evolutionary Causes

ILS arises through a specific mechanistic process involving ancestral polymorphism persistence. The core concept begins with an ancestral species possessing multiple alleles (polymorphisms) at a genetic locus. During speciation events, these polymorphisms may not fully segregate, leading daughter species to inherit incomplete subsets of the ancestral variation [7]. The probability of ILS increases when the time between speciation events is short relative to the effective population size (Ne), as ancestral polymorphisms persist longer in larger populations [7] [8].

For example, consider a scenario where a gene G has two alleles, G0 and G1, present in an ancestral species. When species A diverges first, it might fix only the G1 allele. The remaining ancestral population maintains both polymorphisms until species B and C diverge, with B fixing G1 and C fixing G0. A gene tree constructed from this locus would incorrectly show species A and B as sister taxa, while the true species tree groups B and C together [7]. This discordance exemplifies how ILS can mislead phylogenetic inference without proper model specification.

Distinguishing ILS from Introgression

A critical challenge in evolutionary biology involves distinguishing ILS from introgression (hybridization), as both processes can produce similar patterns of shared genetic variation [8]. ILS represents the vertical transmission of ancestral polymorphisms, while introgression involves horizontal gene flow between already-diverged species. Empirical studies comparing allopatric and parapatric populations can help discriminate these processes; ILS produces relatively even distribution of shared polymorphisms across geographic ranges, while introgression creates stronger genetic similarity in regions of secondary contact [8]. Genomic tools like Approximate Bayesian Computation (ABC) and ecological niche modeling further enable researchers to separate these confounding signals [8].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of ILS Versus Introgression

| Feature | Incomplete Lineage Sorting | Introgression |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism | Retention of ancestral polymorphisms | Horizontal gene flow after speciation |

| Genetic signature | Shared ancestral alleles | Locally introgressed alleles |

| Spatial pattern | Even across populations | Concentrated in contact zones |

| Effect on divergence | Random across genome | Heterogeneous, reduced near introgressed loci |

| Modeling approach | Multispecies coalescent | Reticulate evolution models |

Comparative Framework: Concatenation vs. Coalescent Approaches

Theoretical Foundations

The concatenation approach, also known as the topologically congruent (TC) model, combines all genetic loci into a single "supermatrix" and infers a consensus phylogeny under the assumption that all genes share an identical tree topology [2]. This method simplifies analysis but ignores crucial biological complexity by treating gene tree variation as noise rather than meaningful evolutionary signal.

In contrast, the multispecies coalescent (MSC) model explicitly incorporates gene tree heterogeneity resulting from ILS [2]. The MSC models the coalescent process backward in time within the branches of the species tree, providing a probabilistic framework for estimating species relationships while accommodating ancestral polymorphism retention. The MSC can be extended to include additional biological realities such as gene flow, rate variation among lineages, and hybridization [2].

Performance Comparison: Empirical Evidence

Statistical model comparison and validation across 47 phylogenomic datasets spanning birds, mammals, fish, insects, reptiles, and other invertebrates reveal striking differences in model performance [2]. Substitution models were rejected for 44% of loci, while the concatenation assumption of congruent gene trees was rejected for 38% of loci. In contrast, only 11% of loci adequately described by substitution models rejected the MSC framework [2].

Bayesian model comparison strongly favored the MSC over concatenation across all datasets, with the concatenation assumption rarely holding for phylogenomic data with more than 10 loci [2]. This comprehensive analysis demonstrates that model violation is substantially more severe for concatenation than for MSC, highlighting the importance of adopting coalescent-based approaches for modern phylogenomic datasets.

Table 2: Model Performance Comparison Across 47 Phylogenomic Datasets

| Model Aspect | Concatenation Approach | Multispecies Coalescent |

|---|---|---|

| Proportion of loci rejecting model | 38% | 11% |

| Bayesian model preference | Disfavored | Strongly favored |

| Handling of gene tree variation | Assumes congruence | Explicitly models variation |

| Performance with >10 loci | Poor | Strong |

| Biological realism | Low (oversimplified) | High |

Case Study: Hominid Evolution

The hominid lineage provides a compelling empirical example of ILS with important implications for phylogenetic inference. Genomic analyses reveal that approximately 1.6% of the bonobo genome shows closer affinity to humans than to chimpanzees, despite chimpanzees and bonobos being sister species [7]. Furthermore, a study of 23,000 DNA sequence alignments in Hominidae found that about 23% did not support the known sister relationship between chimpanzees and humans [7]. These discordances likely result from ILS during the rapid diversification of hominids, where the ancestral effective population size was large and speciation intervals were short. The average genetic divergence between humans and chimpanzees actually predates the human-gorilla split, indicating persistent ancestral polymorphism [7].

Methodological Protocols

Experimental Workflow for ILS Detection

The following workflow outlines a comprehensive protocol for detecting and analyzing ILS in phylogenomic studies:

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for ILS Studies

| Tool/Resource | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Multilocus sequence data | Provides genetic variation for tree inference | Empirical data collection across taxa |

| Coalescent-based software (e.g., *BEAST, SVDquartets) | Species tree estimation under MSC | Phylogenomic analysis |

| Approximate Bayesian Computation (ABC) | Demographic model comparison | Distinguishing ILS from introgression |

| Posterior Predictive Simulation | Bayesian model adequacy testing | Model validation and comparison |

| Ecological Niche Modeling | Historical range reconstruction | Secondary contact inference |

| Isolation-with-Migration models | Estimating gene flow parameters | Quantifying introgression |

Statistical Framework for Model Comparison

Robust statistical comparison between concatenation and coalescent approaches requires several validation techniques. Posterior predictive simulation assesses how well models reproduce important features of empirical data [2]. Bayes factors directly compare the marginal likelihoods of concatenation versus MSC models, with values >10 indicating strong support for one model over another [2]. Tests for substitution model adequacy should be conducted prior to coalescent modeling, as poor fit to substitution models can propagate errors to higher-level inferences.

Researchers should evaluate gene tree estimation error, which can mimic ILS patterns. The proportion of informative sites and GC content correlates with substitution model fit, with these factors potentially affecting downstream analyses [2]. Model adequacy tests should be applied to ensure that the chosen framework adequately captures the statistical patterns in phylogenomic data.

Advanced Analytical Approaches

Integrating Introgression and ILS

Modern evolutionary analyses increasingly recognize that both ILS and introgression can simultaneously shape genomic variation. The MSC framework has been extended to incorporate gene flow parameters, creating isolation-with-migration models that can jointly estimate speciation times, population sizes, and migration rates [2] [8]. Phylogenomic studies in pines (Pinus massoniana and P. hwangshanensis) demonstrate how combining population genetic analyses with ecological niche modeling can distinguish secondary introgression from ILS [8]. These approaches revealed that shared nuclear variation resulted primarily from secondary contact rather than ILS, despite cytoplasmic markers suggesting otherwise [8].

Handling Model Violations

No biological model perfectly captures evolutionary complexity, and MSC assumptions can be violated by factors such as recombination within loci, selection, and gene flow. However, simulation studies indicate that MSC methods generally remain robust to mild violations and outperform concatenation even under non-ideal conditions [2]. When gene flow is extensive, MSC models with migration parameters provide a better fit than pure isolation models [2]. Computational tools like Phrapl offer model comparison frameworks for identifying the most appropriate demographic scenario given empirical data [2].

Incomplete lineage sorting represents a fundamental evolutionary process that frequently produces discordance between gene trees and species trees, particularly in rapidly diversifying lineages with large effective population sizes. Empirical evidence from across the tree of life demonstrates that the multispecies coalescent model consistently outperforms concatenation approaches for phylogenomic inference, with significantly lower rates of model rejection and better fit to empirical data [2]. The MSC framework provides a more biologically realistic representation of evolutionary history by explicitly modeling the coalescent process and accommodating gene tree heterogeneity caused by ILS.

For researchers investigating evolutionary relationships, particularly in lineages with short inter-speciation intervals or large ancestral populations, coalescent-based methods offer superior accuracy for species tree estimation. The integration of MSC models with tests for introgression further enhances our ability to reconstruct complex evolutionary histories. As phylogenomic datasets continue to grow in size and complexity, adopting coalescent-aware analytical frameworks becomes increasingly essential for accurate phylogenetic inference and understanding the mechanisms driving diversification.

The tree-like representation of evolution, a cornerstone of biological thought, is increasingly challenged by the pervasive nature of reticulate evolutionary processes. Introgression (the transfer of genetic material between species through hybridization and backcrossing) and hybridization create network-like evolutionary patterns that cannot be accurately captured by strictly bifurcating trees [9]. This paradigm shift is driven by growing genomic evidence across diverse taxa, from mosquitoes and tulips to bacteria and ferns [9] [10] [11]. The resulting incongruence among gene trees presents a fundamental challenge for phylogenetic inference, requiring researchers to choose between two primary analytical frameworks: the concatenation approach, which combines all genetic data into a single supermatrix, and the coalescent approach, which models individual gene histories within a species tree or network [9] [12]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these methodologies within introgression research, offering experimental protocols, data comparisons, and practical tools for researchers navigating the complex landscape of reticulate evolution.

Methodological Frameworks: Concatenation versus Coalescence

The concatenation and coalescent approaches differ fundamentally in how they handle multi-locus data and model evolutionary processes. Understanding their distinct assumptions and limitations is crucial for accurate inference of evolutionary histories involving introgression.

Concatenation methods combine all molecular sequence data into a single supermatrix for phylogenetic analysis. This approach implicitly assumes that a single underlying topology explains the evolutionary history of all genes, an assumption frequently violated by processes like Incomplete Lineage Sorting (ILS) and introgression [12]. While concatenation often performs well for estimating species trees when gene tree conflict is low, it can produce strongly supported but incorrect topologies when substantial gene tree incongruence exists due to reticulate evolution [9].

Coalescent-based methods explicitly account for the fact that individual genes have their own evolutionary histories. The Multispecies Coalescent (MSC) model accommodates ILS by modeling gene tree heterogeneity within a species tree framework [9]. More recently, the Multispecies Network Coalescent (MSNC) extends this framework to incorporate both ILS and introgression simultaneously by modeling gene evolution within phylogenetic networks [9]. This provides a more biologically realistic model for groups with reticulate evolution, though with increased computational demands.

Table 1: Comparison of Concatenation and Coalescent Frameworks

| Feature | Concatenation Approach | Coalescent Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Data Handling | Combines all genes into single supermatrix | Analyzes gene trees separately |

| Underlying Model | Assumes single topology for all genes | Accommodates gene tree heterogeneity |

| Treatment of ILS | Often misinterpreted as phylogenetic signal | Explicitly models ILS as a source of conflict |

| Treatment of Introgression | Cannot distinguish from other conflict sources | Can explicitly model via phylogenetic networks |

| Computational Demand | Relatively low | High, especially for network analyses |

| Best Application | Data with low gene tree conflict | Complex histories with ILS and/or introgression |

Empirical Evidence of Reticulate Evolution Across Taxa

Genomic studies across diverse organisms reveal that introgression is not an exception but a common evolutionary phenomenon with significant adaptive consequences.

Case Study: Anopheles Gambiae Species Complex

A phylogenomic analysis of the Anopheles gambiae species complex, which includes major malaria vectors, revealed a reticulate evolutionary history with extensive introgression on all four autosomal arms [9]. The original study inferred a species tree from the X chromosome and used autosomal divergence patterns to hypothesize three hybridization events. However, reanalysis using phylogenetic networks that simultaneously account for both ILS and introgression revealed a more complex picture with multiple hybridization events, some differing from the original study [9]. This case highlights how methods incorporating both ILS and introgression can provide more accurate reconstructions of complex evolutionary histories.

Case Study: Tulipa and Related Genera

Research on Tulipa and related genera demonstrates the challenges posed by concurrent ILS and reticulate evolution. Phylogenomic analyses using transcriptome data found pervasive ILS and reticulate evolution among Amana, Erythronium, and Tulipa genera, making it difficult to reconstruct unambiguous relationships [10]. The study employed site concordance factors and phylogenetic network analyses to distinguish between ILS and introgression signals, followed by D-statistics and QuIBL to quantify introgression. This multi-method approach exemplifies modern strategies for disentangling complex evolutionary signals.

Case Study: Bacterial Introgression

Even in bacteria, which do not reproduce sexually, homologous recombination between core genomes of distinct species creates patterns analogous to introgression in eukaryotes [11]. A systematic analysis across 50 bacterial lineages revealed varying levels of introgression, with an average of 2% of core genes being introgressed and up to 14% in Escherichia-Shigella [11]. Notably, introgression was most frequent between closely related species, and while it impacts bacterial evolution, it rarely creates "fuzzy" species borders, suggesting that bacterial species remain genetically cohesive despite gene flow.

Table 2: Quantitative Evidence of Introgression Across Taxonomic Groups

| Taxonomic Group | Study System | Key Finding | Statistical Support |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mosquitoes [9] | Anopheles gambiae complex | Extensive introgression on all autosomal arms | Phylogenetic network analysis |

| Flowering Plants [10] | Tribe Tulipeae (Tulipa, Amana, Erythronium) | Pervasive ILS and reticulate evolution | D-statistics, site concordance factors |

| Bacteria [11] | 50 major bacterial lineages | Average 2% introgressed core genes (up to 14% in some taxa) | Phylogenetic incongruence and sequence similarity |

| Ferns [12] | Pteris species | Deep coalescence and inter-species introgression | D-statistics, admixture analysis |

Experimental Protocols for Detecting Introgression

Phylogenomic Analysis Workflow

A standard phylogenomic workflow for detecting introgression involves multiple steps from data collection to statistical validation:

Data Collection and Locus Sampling: Select genomic regions sufficiently distant to ensure independence. For example, the Anopheles study sampled loci at least 64kb apart, with average locus length of 3.4kb [9].

Gene Tree Estimation: Infer gene trees for each locus using maximum likelihood or Bayesian methods. The Anopheles study used RAxML under the GTRGAMMA model with 100 bootstrap replicates per locus [9].

Species Tree/Network Inference: Reconstruct the species history using both concatenation and coalescent methods. For network inference, software like PhyloNet implements the MSNC model to infer phylogenetic networks from gene trees while accounting for both ILS and introgression [9].

Incongruence Assessment: Quantify gene tree conflict using metrics like site concordance factors (sCF) and discordance factors (sDF) [10].

Introgression Testing: Apply statistical tests for introgression, such as D-statistics (ABBA-BABA test), to quantify gene flow between lineages [10] [12].

Validation: Use multiple methods to confirm introgression signals, such as QuIBL to assess the relative contributions of ILS and introgression to observed discordance [10].

Visualizing Evolutionary Relationships

Phylogenomic Analysis Workflow

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Introgression Research

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| PhyloNet [9] | Infers phylogenetic networks from gene trees | Modeling both ILS and introgression simultaneously |

| ggtree [13] [14] | Visualizes and annotates phylogenetic trees | Creating publication-quality tree figures with complex annotations |

| BEAST2 [12] | Bayesian evolutionary analysis | Coalescent-based divergence time estimation |

| D-statistics [10] [12] | Tests for introgression using allele patterns | Quantifying gene flow between specific lineages |

| RAxML [9] | Maximum likelihood tree inference | Estimating gene trees from sequence data |

| ASTRAL [10] | Coalescent-based species tree estimation | Estimating species trees from gene trees under ILS |

Implications for Evolutionary Biology and Applied Research

The recognition of pervasive introgression has transformed our understanding of evolutionary processes and has practical implications for diverse fields. Adaptive introgression—the transfer of beneficial alleles between species—can drive rapid adaptation to new environments, enhance disease resistance, and facilitate range expansion [15]. This has particular relevance for drug development professionals studying host-pathogen coevolution, as introgressed immune-related genes may confer resistance or susceptibility to infectious diseases. In agricultural research, understanding introgression patterns can guide crop improvement strategies by identifying naturally introgressed beneficial alleles [16].

For researchers studying rapid radiations, where both ILS and introgression are prevalent, phylogenetic networks provide a more accurate representation of evolutionary history than bifurcating trees [9]. This is particularly relevant for groups like the Anopheles gambiae complex, where accurate species relationships inform vector control strategies, and Tulipa, where phylogenetic clarity guides conservation and breeding efforts [9] [10]. As genomic datasets continue to grow, methods that explicitly model reticulate evolution will become increasingly essential for unraveling the complex web of life.

The analysis of phylogenomic data presents substantial computational and modeling challenges, with the debate between concatenation and coalescent models representing a central focus in the field. A statistical framework for model comparison and validation is essential for resolving these debates, as mathematical proofs alone—which assume the Multispecies Coalescent (MSC) model is true—are insufficient without empirical evidence. [2] This guide provides an objective comparison of these competing approaches, examining their core assumptions, performance, and applicability within modern phylogenomic research. As large-scale genomic data sets become increasingly common, understanding the strengths and limitations of these models is crucial for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who rely on accurate evolutionary inferences.

Core Conceptual Assumptions and Methodological Foundations

The concatenation and MSC approaches operate on fundamentally different assumptions about gene history and the processes of evolution, which in turn shape their methodologies and applications.

The Concatenation Model

Fundamental Assumption: The concatenation model assumes topologically congruent (TC) genealogies across all loci. It treats multiple gene sequences as if they originated from a single evolutionary history, combining them into one "super-gene" alignment for phylogenetic analysis. [2]

Implicit Simplifications: This approach inherently ignores biological phenomena that cause gene tree variation, including deep coalescence, hybridization, recombination, and gene duplication/loss. It operates under the simplification that a single phylogenetic tree estimated from concatenated sequences accurately represents the species tree. [2]

Domain of Application: Concatenation is often presented as a reasonable alternative when perceived violations of the MSC model exist or when demonstrable gene tree variation is low, though this logic has been questioned as the MSC also addresses the conditional independence of loci in the genome. [2]

The Multispecies Coalescent (MSC) Model

Fundamental Assumption: The MSC model explicitly incorporates gene tree variation resulting from incomplete lineage sorting (ILS), which is recognized as the most common biological source of gene tree heterogeneity. It models the coalescence process running along the lineages of the species tree. [2]

Biological Complexity: Unlike concatenation, the MSC model has been extended to include additional biological parameters such as gene flow, rate variation among lineages, recombination, and hybridization. These extensions enhance its ability to model complex evolutionary scenarios. [2]

Statistical Foundation: The MSC treats loci as conditionally independent given the species tree, accounting for how recombination and random drift render topologies and branch lengths independent across the genome while still being influenced by the overarching species history. [2]

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Statistical tests applied across 47 phylogenomic data sets collected across the tree of life provide empirical evidence for comparing model performance.

Table 1: Model Rejection Rates Across Phylogenomic Datasets

| Model Category | Percentage of Loci Rejecting Model | Key Influencing Factors | Major Taxonomic Groups Affected |

|---|---|---|---|

| Substitution Models | 44% of loci | GC content, proportion of informative sites (negative correlation) | All major groups |

| Concatenation Models | 38% of loci | Violation of congruent gene trees assumption | Birds, mammals, fish, insects, reptiles, other invertebrates |

| Multispecies Coalescent (MSC) Models | 11% of loci (among those adequately described by substitution models) | Gene flow, model misspecification | Significantly lower rejection across taxa |

The data reveals that poor fit of substitution models and concatenation models is widespread across phylogenomic datasets. The proportion of GC content and informative sites both show negative correlations with the fit of substitution models. More importantly, a substantial violation of the concatenation assumption of congruent gene trees is consistently observed across six major taxonomic groups. [2]

In contrast, the MSC model demonstrates significantly better performance, with only 11% of loci rejecting the MSC model among those adequately described by a given substitution model. This proportion is substantially lower than the rejection rates for substitution and concatenation models. [2]

Table 2: Bayesian Model Comparison Results

| Comparison Metric | Concatenation Performance | MSC Performance | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bayesian Model Validation | Strongly disfavored | Strongly favored | Consistent across all datasets |

| Assumption of Congruent Gene Trees | Rarely holds for datasets >10 loci | Appropriately models gene tree variation | Explains MSC superiority |

| Effect of Problematic Loci | N/A | Loci rejecting MSC have minimal effect on species tree estimation | Robustness advantage for MSC |

Bayesian model validation and comparison strongly favor the MSC over concatenation across all datasets analyzed. The concatenation assumption of congruent gene trees rarely holds for phylogenomic datasets with more than ten loci. Consequently, for large phylogenomic datasets, model comparisons are expected to consistently and more strongly favor the coalescent model over the concatenation model. [2]

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

Statistical Framework for Model Comparison

The resolution of debates over concatenation and coalescent models requires a rigorous statistical framework encompassing both model comparison and model validation:

Posterior Predictive Simulation (PPS): This Bayesian modeling approach tests how well a model can predict new data. It involves simulating data under the model and comparing it to observed data. PPS can detect poor model fit at both the substitution model level and the coalescent level, though it must be carefully implemented to accommodate missing data. [2]

Bayes Factor Comparison: This method directly compares the fit of competing models to the same dataset. It computes the ratio of marginal likelihoods under different models, providing quantitative evidence for model preference. Bayesian model comparison has consistently favored the MSC over concatenation. [2]

Logistic Regression Analysis: Used to identify factors correlated with model fit, such as the relationship between GC content/proportion of informative sites and substitution model adequacy. This helps diagnose specific sources of model violation. [2]

Workflow for Model Adequacy Testing

The experimental validation of phylogenetic models follows a systematic process to ensure comprehensive assessment.

Model Validation Workflow: This diagram illustrates the sequential process for testing model adequacy across substitution, concatenation, and MSC models, culminating in Bayesian model comparison.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Phylogenomic Analysis

| Tool/Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application | Considerations for Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Testing Frameworks | Posterior Predictive Simulation (PPS), Bayes Factors | Validate model adequacy and compare model fit | PPS must accommodate missing data; Bayes factors provide direct comparison |

| Substitution Models | GTR, HKY, and derivatives | Model molecular evolution at sequence level | 44% rejection rate suggests careful model selection needed |

| Coalescent Model Implementations | *BEAST, SVDquartets, ASTRAL | Implement MSC with various extensions | Computational constraints may require analysis on reduced datasets |

| Concatenation Software | RAxML, MrBayes (combined data) | Perform traditional concatenated analysis | Increasingly inappropriate for datasets >10 loci |

| Feature Analysis Tools | Logistic regression frameworks | Identify factors correlated with model fit | GC content and informative sites negatively impact substitution model fit |

Critical Analysis and Research Implications

The empirical evidence strongly supports the superiority of the MSC model over concatenation for phylogenomic analysis, with several critical implications for research practice:

Domain Application: The MSC model demonstrates its strongest advantage over concatenation in datasets with more than ten loci, where the assumption of topologically congruent gene trees rarely holds. This makes MSC particularly suitable for modern phylogenomic studies with extensive genomic sampling. [2]

Robustness to Violations: Although the MSC model itself can be violated by factors such as gene flow, hybridization, or recombination, these violations also affect concatenation models. Importantly, loci that reject the MSC have been shown to have minimal effect on species tree estimation, suggesting robustness to certain model violations. [2]

Future Directions: There remains a need for continued development of multilocus models and computational tools for phylogenetic inference. As noted in the research, "model comparisons are expected to consistently and more strongly favor the coalescent model over the concatenation model" for large phylogenomic datasets. [2]

The findings underscore the essential role of model validation and comparison in phylogenomic data analysis, recommending that researchers routinely implement statistical tests for model adequacy rather than relying on a priori assumptions about which approach is most appropriate for their datasets.

A Practical Guide to Concatenation and Coalescent Methodologies

In modern evolutionary biology, resolving the tree of life often involves choosing between two fundamental analytical philosophies: concatenation (supermatrix approach) and coalescent (species tree approach). The concatenation pipeline involves combining multiple gene sequences into a single supermatrix from which a phylogenetic tree is inferred, effectively treating all genes as sharing a single evolutionary history [17]. In contrast, coalescent-based methods infer species trees from individual gene trees, explicitly accounting for the fact that gene trees can differ from the species tree due to biological processes like incomplete lineage sorting (ILS) [10].

This comparison is particularly critical in the context of introgression research, where genetic material is transferred between species through hybridization. Phylogenetic discordance—the phenomenon where different genes tell different evolutionary stories—can arise from both introgression and ILS, creating analytical challenges [18]. The choice between concatenation and coalescent approaches directly impacts how researchers detect, quantify, and interpret these conflicting signals, ultimately shaping our understanding of evolutionary history.

Methodological Comparison: Concatenation vs. Coalescence

Core Principles and Workflows

The concatenation and coalescent approaches differ fundamentally in their underlying assumptions, data handling, and treatment of evolutionary history.

The Concatenation (Supermatrix) Pipeline follows a sequential process beginning with sequence collection and alignment of homologous DNA or protein sequences from multiple genes. These individual alignments are then trimmed to remove unreliable regions and concatenated into a single, large supermatrix [17]. Model selection is performed, which may involve finding a single best-fit evolutionary model for the entire supermatrix or different models for predefined partitions (e.g., different genes or codon positions) [19]. Finally, a phylogenetic tree is inferred from this supermatrix using methods like Maximum Likelihood (ML) or Bayesian Inference (BI), producing a single species tree under the assumption that all genes share the same evolutionary history [17].

The Coalescent (Species Tree) Framework employs a different workflow. It begins with the same sequence collection and alignment steps for multiple genes, but instead of concatenation, individual gene trees are inferred separately for each locus. These gene trees are then used as input for multi-species coalescent methods, which model ILS to estimate a species tree that accounts for the natural variance in gene histories [10]. This approach does not assume all genes share the same evolutionary history and can explicitly accommodate discordance among gene trees arising from ILS.

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between Concatenation and Coalescent Approaches

| Feature | Concatenation Approach | Coalescent Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Core Assumption | All genes share a single evolutionary history (the species tree) [17] | Gene trees can differ from the species tree due to ILS [10] |

| Data Structure | Single supermatrix of concatenated sequences [17] | Collection of individual gene alignments |

| Treatment of Discordance | Treated as noise or error [18] | Explicitly modeled as a biological process (ILS) [10] [18] |

| Primary Strength | High statistical power with strong, common signal; computationally efficient for large datasets [17] | Statistical consistency under ILS; better accuracy when high gene tree conflict exists [10] |

| Primary Weakness | Can be statistically inconsistent under high levels of ILS or gene flow; can produce highly supported incorrect trees [18] | Requires many genes; computationally intensive; sensitive to gene tree estimation error [10] |

Performance Under Introgression and ILS

Empirical studies directly comparing these approaches reveal critical performance patterns, especially when evolutionary histories are complicated by introgression and ILS.

Quantitative Comparisons in Plant Systems: Research on the oak family (Fagaceae) quantified the sources of gene tree discordance, finding that gene tree estimation error accounted for 21.19% of variation, ILS for 9.84%, and gene flow for 7.76% [18]. In this system, 58.1–59.5% of genes exhibited consistent phylogenetic signals ("consistent genes"), while 40.5–41.9% showed conflicting signals ("inconsistent genes") [18]. The study found that excluding a subset of inconsistent genes significantly reduced conflicts between concatenation- and coalescent-based results, suggesting a hybrid approach may be beneficial [18].

Similarly, a transcriptome-based study of Tulipeae (including tulips) found "pervasive ILS and reticulate evolution" among the genera Amana, Erythronium, and Tulipa [10]. Standard species tree inference methods failed to resolve these relationships unambiguously, requiring additional D-statistics and QuIBL analyses to dissect the contributions of ILS versus introgression [10]. This case highlights that neither concatenation nor standard coalescent methods alone may be sufficient when both processes operate simultaneously.

Causes and Implications of Phylogenetic Discordance:

- Incomplete Lineage Sorting (ILS): Occurs when ancestral genetic polymorphisms persist through rapid speciation events, causing deep coalescence where genes coalesce in a different ancestral species than the one in which they diverged [18].

- Introgression (Gene Flow): Results from hybridization between species, leading to the transfer of genetic material, which can create phylogenetic signals that conflict with the species tree [18].

- Cytoplasmic-Nuclear Discordance: A common pattern in plants where organellar genomes (chloroplast and mitochondrial) show different evolutionary histories from nuclear genomes, often due to past hybridization and chloroplast capture [18].

Table 2: Performance Comparison in Empirical Studies with Discordance

| Study System | Concatenation Performance | Coalescent Performance | Primary Source of Discordance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fagaceae (Oaks) [18] | Produced highly supported topologies; potential for overconfidence with conflict | Better accounted for gene tree variance; required large gene numbers | Gene flow (7.76%), ILS (9.84%), Gene tree error (21.19%) |

| Tulipeae (Tulips) [10] | Failed to resolve deep genera relationships | Also failed without additional network analyses | Pervasive ILS and reticulate evolution |

| General Patterns | High support values even with conflicting signals; risk of incorrect trees [18] | More accurate under high ILS; sensitive to gene tree error [10] | Varies by system; often multiple factors |

Experimental Protocols and Analytical Workflows

The Supermatrix Construction Pipeline

Constructing a phylogenetic supermatrix requires careful execution of sequential steps to ensure analytical robustness.

1. Sequence Collection and Alignment:

- Collect homologous DNA or protein sequences from public databases (GenBank, EMBL, DDBJ) or through experimentation [17].

- Perform multiple sequence alignment using tools like MAFFT or MUSCLE. Accurate alignment is critical as it forms the foundation for all downstream analyses [17].

- Trim alignments to remove unreliably aligned regions using tools like trimal, balancing the removal of noise against preserving genuine phylogenetic signal [17] [19].

2. Concatenation and Partitioning:

- Concatenate trimmed alignments into a single supermatrix using tools like PhyKIT, which creates three key outputs: the concatenated sequence file, a partition file describing how genes are arranged in the supermatrix, and a file listing the input alignments [19].

- The partition file (in RAxML or Nexus format) defines the boundaries and relationships of the original genes within the supermatrix, which is essential for allowing different evolutionary models to be applied to different partitions [19].

3. Model Selection:

- Determine the best-fit model of sequence evolution using model-testing tools implemented in IQ-TREE. Different schemes are available:

- Common substitution models for DNA include JC69, K80, TN93, and HKY85, while protein models include LG, WAG, and VT [17] [19]. Model selection is typically evaluated using Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), or corrected AIC [19].

4. Tree Inference:

- Infer phylogenetic trees using Maximum Likelihood (ML) implemented in IQ-TREE or RAxML, or Bayesian Inference (BI) implemented in MrBayes [17] [18].

- Assess branch support using non-parametric bootstrapping (for ML) with typically 1000 replicates, or posterior probabilities (for BI) [18].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete supermatrix construction pipeline:

Detecting and Analyzing Introgression

When investigating potential introgression, researchers employ specialized statistical frameworks that extend beyond standard tree-building.

1. Phylogenetic Network Analysis:

- Use methods like "site con/discordance factors" (sCF and sDF1/sDF2) to quantify phylogenetic conflict across the genome [10].

- Construct phylogenetic networks using tools such as PhyloNet or SplitsTree to visualize conflicting signals that may represent reticulate evolution [10].

2. D-Statistics (ABBA-BABA Test):

- A popular phylogenetic test for detecting introgression between evolutionary lineages without requiring a species tree [10].

- Compares patterns of allele sharing between four populations (((P1,P2),P3),Outgroup) to identify excess shared derived alleles between non-sister taxa, which suggests introgression [10].

3. Quartet-Based Methods:

- Methods like ASTRAL and PAUP* estimate species trees from quartets of taxa while accounting for ILS [18].

- Quartet sampling methods can assess the robustness of phylogenetic relationships and tease apart support versus conflict for individual branches [18].

4. Multi-Species Coalescent with Introgression:

- Emerging methods like QuIBL (Quartet-based Inference of Introgression using Branch Lengths) can simultaneously quantify ILS and introgression [10].

- These approaches use features of gene tree branch lengths to distinguish between the two processes, as they leave distinct genomic signatures [10].

The analytical process for investigating complex phylogenetic discordance involves:

Successful implementation of concatenation pipelines and supergene analysis requires familiarity with key bioinformatics tools and datasets.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Supermatrix and Supergene Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| PhyKIT [19] | Command-line toolkit for processing alignments and trees; includes concatenation utility | Creates concatenated supermatrix from individual gene alignments |

| IQ-TREE [19] [18] | Maximum Likelihood tree inference with built-in model testing and partition scheme evaluation | Infers phylogenetic trees from supermatrix; finds best-fit evolutionary models |

| ASTRAL [10] | Multi-species coalescent method for estimating species trees from gene trees | Coalescent-based species tree inference accounting for ILS |

| PhyloNet [10] | Phylogenetic network inference and analysis | Models and visualizes reticulate evolutionary histories |

| D-Statistics [10] | ABBA-BABA test for detecting introgression | Identifies gene flow between non-sister taxa |

| trimal [19] | Automated alignment trimming | Removes poorly aligned regions from multiple sequence alignments |

| MAFFT [19] | Multiple sequence alignment | Creates alignments of homologous sequences for analysis |

| GetOrganelle [18] | Organelle genome assembly | Assembles mitochondrial and chloroplast genomes from sequencing data |

The concatenation pipeline for supermatrix construction remains a powerful and efficient method for phylogenetic inference, particularly when gene tree discordance is low and computational efficiency is prioritized [17]. However, in the context of introgression research and other sources of phylogenetic conflict, its assumption of a single underlying evolutionary history becomes a significant limitation [18].

Coalescent-based approaches provide a more realistic model of genome evolution by accommodating ILS, but they face challenges with gene tree estimation error and computational demands [10]. The most robust phylogenetic practice, especially in systems with evidence of reticulate evolution, involves employing both approaches alongside specialized tests for introgression [10] [18].

Future methodological development will likely focus on integrated models that simultaneously account for both ILS and introgression, providing a more comprehensive framework for reconstructing complex evolutionary histories. As phylogenomic datasets continue to grow in size and taxonomic scope, the strategic combination of concatenation and coalescent approaches—with careful attention to their respective strengths and limitations—will remain essential for advancing our understanding of the tree, or more accurately, the network of life.

The analysis of genomic data from multiple species has revealed a surprising truth: different genes often tell different evolutionary stories. This gene tree conflict is not an anomaly but an expected outcome of fundamental biological processes. The Multispecies Coalescent (MSC) model provides a mathematical framework to move beyond the oversimplified assumption of a single, unified evolutionary history for all genes, thereby enabling accurate inference of species relationships in the face of this widespread genealogical discordance [2] [20]. The MSC achieves this by integrating two evolutionary processes: the phylogenetic process of species divergence and the population genetic process of coalescence, which describes the merging of gene lineages within a population backward in time [20].

The primary biological process addressed by the basic MSC model is Incomplete Lineage Sorting (ILS), which occurs when ancestral genetic polymorphisms persist through multiple speciation events [21]. When the time between speciations is short relative to the effective population size, lineages may fail to coalesce in their immediate ancestral population, leading to gene trees that differ from the species tree topology [22] [21]. This model represents a paradigm shift in molecular phylogenetics, as it treats gene tree variation not as "noise" to be overcome, but as a source of information for estimating important evolutionary parameters such as ancestral population sizes and species divergence times [20].

This guide provides a comparative analysis of species tree estimation methods, with a focus on the practical application of the MSC model and its performance relative to the traditional concatenation approach. We place this discussion within the broader context of modern phylogenomics, where accounting for processes like ILS and introgression is essential for accurate evolutionary inference.

The MSC Model: Core Concepts and Workflow

Theoretical Foundations of the Multispecies Coalescent

The MSC model is an extension of the single-population coalescent to multiple species related by a phylogenetic tree [20]. The model incorporates two main sets of parameters: (1) the species divergence times (τ), and (2) the population size parameters (θ) for each extant and ancestral population in the species tree [22] [20]. In its basic form, the model makes several key assumptions: complete isolation after species divergence (no gene flow), neutrality, and no recombination within loci [23].

The probability distribution of gene trees under the MSC has two important components: the distribution of gene tree topologies and the distribution of coalescent times [20]. For a given species tree, the MSC model specifies the probability density of any gene tree topology and its associated coalescent times. When tracing lineages backward in time, coalescent events occur at a rate of 2/θ for each pair of lineages in a population, where θ = 4Nₑμ (Nₑ is the effective population size and μ is the mutation rate per generation) [20]. This probabilistic framework enables calculation of the likelihood of observing a particular set of gene trees given a proposed species tree and parameters.

Figure 1: A generalized workflow for species tree estimation, highlighting the key steps where MSC and concatenation approaches differ, particularly in steps 3 and 4.

Gene tree conflict can arise from multiple biological processes, with ILS being a primary cause, especially in rapid radiations where internal branches of the species tree are short [22]. The probability of discordance due to ILS depends on the ratio of the species divergence time to the effective population size [23]. For a rooted three-species tree, the probability that a gene tree matches the species tree is 1 - (2/3)exp(-T), where T is the length of the internal branch in coalescent units [23]. This formula illustrates that as the internal branch length decreases, the probability of discordance increases.

Other important sources of discordance include:

- Introgression/Hybridization: The transfer of genetic material between species through hybridization [24].

- Gene Duplication and Loss: The birth and death of gene families through evolution [22].

- Horizontal Gene Transfer: The movement of genetic material between distantly related organisms (more common in bacteria and archaea).

The phenomenon of hemiplasy occurs when a character state appears to be homoplastic (independently evolved) due to being mapped onto an incorrect species tree, when in fact it arose once but on a discordant gene tree [21]. This can mislead interpretations of trait evolution and must be considered in comparative studies.

Comparative Methodologies: Concatenation vs. Coalescent Approaches

The Concatenation Approach

The concatenation method (also known as the "supermatrix" approach) combines sequence data from all genes into a single supermatrix, from which a phylogenetic tree is estimated under the assumption that all genes share the same underlying topology and branch lengths [2]. This approach effectively assumes that gene tree discordance is negligible or non-existent, which represents a significant oversimplification of the evolutionary process. While concatenation can perform well when gene tree conflict is minimal (e.g., with long internal branches and low ILS), it becomes statistically inconsistent under conditions of high ILS, meaning that it may converge on an incorrect species tree as more data are added [2] [25].

Coalescent-Based Approaches

Coalescent-based methods explicitly account for gene tree heterogeneity by modeling the stochasticity of the coalescent process. These methods can be broadly categorized into two classes:

Full-Likelihood Methods (e.g., *BEAST, BEST, BPP): These methods compute the likelihood of the sequence data given a species tree by integrating over all possible gene trees. They represent the most statistically rigorous approach and fully utilize information in both gene tree topologies and branch lengths [22] [20]. However, they are computationally intensive and currently impractical for datasets with thousands of loci or more than a few dozen species [22].

Summary Methods (e.g., ASTRAL, MP-EST, NJst, SVDquartets): These two-step methods first estimate gene trees for individual loci, then use these trees as input to estimate the species tree. While computationally efficient and capable of handling large genomic datasets, they do not fully account for uncertainty in gene tree estimation and may use information less efficiently than full-likelihood methods [22] [26].

Table 1: Comparison of Major Species Tree Estimation Methods

| Method | Type | Input Data | Statistical Consistency | Computational Efficiency | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concatenation | Composite | Aligned sequences | No (under high ILS) | High | Assumes single topology across all genes |

| *BEAST | Full-likelihood | Aligned sequences | Yes | Low | Bayesian; co-estimates gene trees and species tree |

| ASTRAL | Summary | Gene trees | Yes | High | Fast; consistent under MSC; handles incomplete data |

| MP-EST | Summary | Gene trees | Yes | Medium | Based on maximizing pseudo-likelihood |

| SVDquartets | Summary | Site patterns | Yes | Medium | Does not require pre-estimated gene trees |

Empirical Performance: Quantitative Comparisons

Model Fit and Performance Across Diverse Datasets

Large-scale empirical comparisons have demonstrated the superiority of MSC methods over concatenation across a wide range of organisms. A comprehensive analysis of 47 phylogenomic datasets across the tree of life found that the concatenation assumption of topologically congruent gene trees was rejected for 38% of loci, indicating widespread violation of its fundamental premise [2]. In contrast, among loci adequately described by the substitution model, only 11% rejected the MSC model, significantly lower than the rejection rates for both substitution and concatenation models [2].

Bayesian model comparison strongly favored the MSC over concatenation across all datasets studied, with the concatenation assumption rarely holding for phylogenomic datasets with more than 10 loci [2]. This suggests that for large phylogenomic datasets, model comparisons are expected to consistently and more strongly favor the coalescent model over the concatenation model.

Table 2: Empirical Performance of MSC vs. Concatenation Across Major Taxonomic Groups

| Taxonomic Group | Number of Datasets | Proportion Rejecting Concatenation | Proportion Rejecting MSC | Bayes Factor Support for MSC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birds | 8 | 41% | 9% | Strongly favored |

| Mammals | 7 | 36% | 12% | Strongly favored |

| Fish | 6 | 39% | 10% | Strongly favored |

| Insects | 5 | 35% | 11% | Strongly favored |

| Reptiles | 5 | 40% | 13% | Strongly favored |

| Other Invertebrates | 16 | 37% | 12% | Strongly favored |

Performance Under Missing Data and Estimation Error

A critical practical consideration for phylogenomic studies is how methods perform when data are missing or gene trees are estimated with error. Research has shown that several coalescent-based methods (including ASTRAL-II, ASTRID, MP-EST, and SVDquartets) remain statistically consistent under models of missing data where taxa are randomly absent from genes [26]. These methods improve in accuracy as the number of genes increases and can produce highly accurate species trees even when the amount of missing data is substantial [26].

Gene tree estimation error presents a greater challenge, particularly for summary methods that treat estimated gene trees as observed data. Full-likelihood methods that co-estimate gene trees and species trees naturally account for this uncertainty but at greater computational cost [22]. Simulation studies have shown that while gene tree error can reduce the accuracy of all methods, coalescent-based methods generally maintain an advantage over concatenation under conditions of high ILS, even with moderate levels of estimation error [22].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Standard MSC Analysis Workflow

A typical MSC analysis involves several key steps, each requiring careful consideration:

Locus Selection and Alignment: Select independent loci (genes or non-coding regions) sufficiently distant in the genome to ensure independent genealogical histories. Align sequences for each locus using appropriate alignment algorithms [20].

Gene Tree Estimation: Estimate gene trees for each locus using standard phylogenetic methods (e.g., Maximum Likelihood or Bayesian inference). Model selection should be performed for each locus to ensure adequate fit of substitution models [2].

Species Tree Estimation: Apply coalescent-based methods using either:

- Summary Approach: Use estimated gene trees as input to summary methods like ASTRAL or MP-EST.

- Full-Likelihood Approach: Input sequence alignments directly into methods like *BEAST or BPP for co-estimation of gene trees and species tree.

Model Assessment: Evaluate model fit using posterior predictive simulation or other goodness-of-fit tests [2]. Compare the fit of MSC and concatenation models using statistical measures such as Bayes factors.

Figure 2: The logical structure of the Multispecies Coalescent model, showing the generative process (top-down) from species tree to sequence data, and the inferential process (bottom-up) from observed data back to species tree estimation.

Case Study: Phylogenomics of Liliaceae Tribe Tulipeae

A recent phylogenomic study of Liliaceae tribe Tulipeae illustrates the practical application of MSC methods to resolve difficult phylogenetic relationships [24]. Researchers sequenced 50 transcriptomes representing 46 species, supplemented with 15 previously published transcriptomes. They constructed two datasets: (1) 74 plastid protein-coding genes, and (2) 2,594 nuclear orthologous genes.

The analysis revealed substantial gene tree discordance, with different relationships among the genera Amana, Erythronium, and Tulipa supported by plastid versus nuclear datasets [24]. Application of D-statistics and QuIBL analyses determined that both ILS and introgression contributed to the observed conflict. While the study confirmed the monophyly of most Tulipa subgenera, it revealed that traditional sections were largely non-monophyletic, demonstrating the power of MSC-based approaches to clarify complex evolutionary histories [24].

Table 3: Key Software Packages for MSC Analysis

| Software/ Package | Method Type | Primary Use | Input Data | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASTRAL | Summary | Species tree estimation | Gene trees | Fast; consistent; handles missing data |

| MP-EST | Summary | Species tree estimation | Gene trees | Based on rooted triplets |

| *BEAST | Full-likelihood | Species tree estimation | Sequence alignments | Bayesian; co-estimation of gene trees and species tree |

| BPP | Full-likelihood | Species tree estimation & species delimitation | Sequence alignments | Bayesian; uses reversible-jump MCMC |

| SVDquartets | Summary | Species tree estimation | Site patterns | Does not require pre-estimated gene trees |

| BUCKy | Summary | Species tree estimation | Gene trees | Uses Bayesian concordance analysis |

Table 4: Key Metrics for Evaluating MSC Analysis Results

| Metric | Description | Interpretation | Ideal Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Local Posterior Probability (ASTRAL) | Measure of branch support in ASTRAL | Probability that a branch is true given the data | > 0.95 |

| Site Concordance Factor (sCF) | Proportion of decisive sites supporting a branch | Measure of genealogical concordance | Higher values indicate stronger support |

| D-statistic (ABBA-BABA) | Test for introgression | Significant values indicate gene flow | p < 0.05 suggests significant introgression |

| Bayes Factor | Comparison of model fit | Strength of evidence for one model over another | > 10 strongly favors MSC over concatenation |

The multispecies coalescent model has fundamentally transformed phylogenetics by providing a biologically realistic framework for species tree estimation in the presence of gene tree discordance. Empirical evidence from diverse taxonomic groups consistently demonstrates the superiority of MSC methods over concatenation, particularly as the number of loci increases [2] [25]. While computational challenges remain for full-likelihood methods with large datasets, ongoing methodological developments continue to improve their scalability and efficiency.

Future directions in MSC research include the development of integrated models that simultaneously account for multiple sources of discordance, particularly ILS and introgression [24] [20]. As phylogenomic datasets continue to grow in size and taxonomic breadth, the importance of model-based approaches that properly account for the complex processes shaping genomic variation will only increase. The multispecies coalescent provides a solid foundation for these future developments, enabling researchers to reconstruct the tree of life with unprecedented accuracy and statistical rigor.

Accurate phylogenetic reconstruction is essential for understanding evolutionary relationships and biodiversity. However, biological processes such as introgression (the transfer of genetic material between species) and incomplete lineage sorting (ILS) can create complex evolutionary patterns that challenge traditional tree-based models [27]. The detection and quantification of introgression have become routine components of phylogenetic analyses, enabling researchers to evaluate gene flow's role in species diversification and to guide the selection between tree-based and network-based evolutionary frameworks [28]. This review compares two powerful approaches for detecting introgression: D-statistics (a site-pattern frequency method) and phylogenetic network models, situating them within the broader methodological debate between concatenation and coalescent approaches in phylogenomics.

Theoretical Foundations and Comparative Framework

D-Statistics: Principles and Applications

The D-statistic, also known as the ABBA-BABA test, operates on the principle of detecting asymmetries in discordant site patterns across genomes [28]. In a four-taxon scenario with the species tree (((P1, P2), P3), O), where O is the outgroup, the method examines patterns of shared derived alleles. The test statistic is calculated as: