De Novo Drug Design in 2025: A Comparative Guide to AI Methods, Benchmarks, and Clinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of modern de novo drug design methods for researchers and drug development professionals.

De Novo Drug Design in 2025: A Comparative Guide to AI Methods, Benchmarks, and Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of modern de novo drug design methods for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational shift from traditional rule-based approaches to AI-driven generative models, detailing core methodologies like chemical language models and graph neural networks. The content covers practical applications, troubleshooting for common challenges like data quality and model interpretability, and rigorous validation frameworks. By synthesizing insights from recent peer-reviewed studies and clinical-stage platforms, this guide serves as a strategic resource for selecting, optimizing, and validating computational methods to accelerate the design of novel therapeutic candidates.

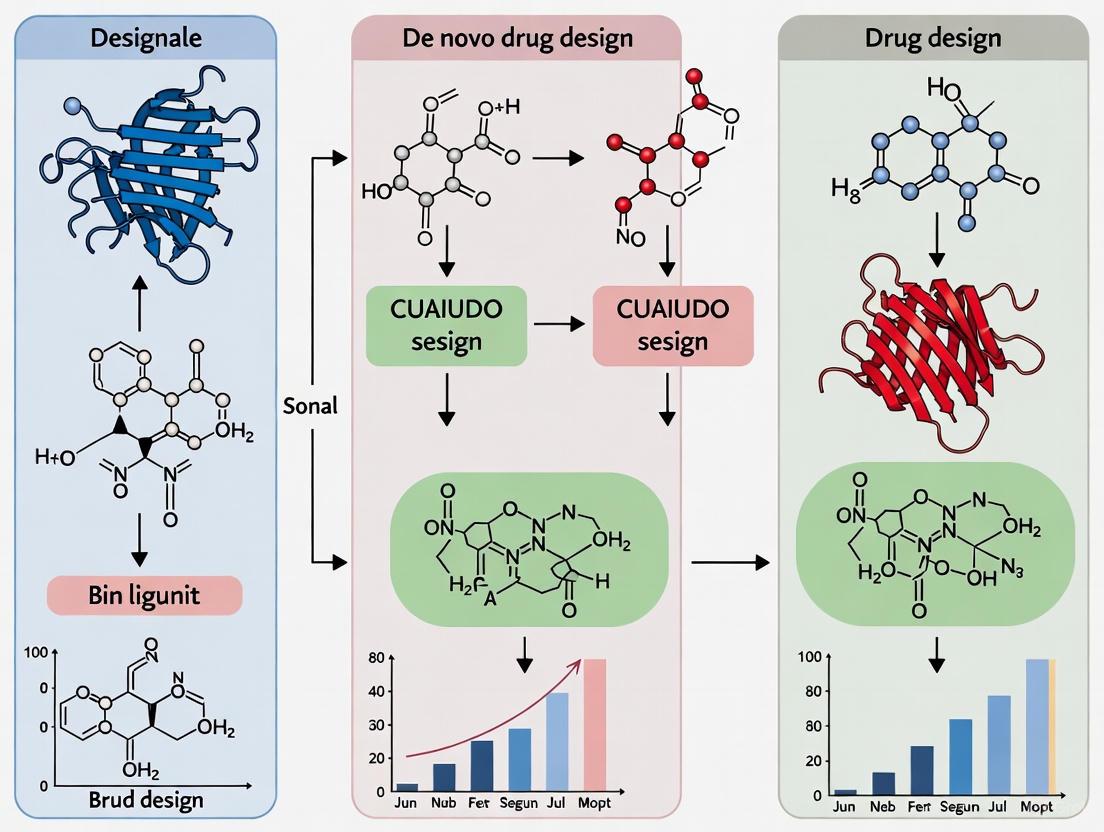

From Rules to AI: The Foundational Shift in De Novo Drug Design

De novo drug design is a computational strategy for generating novel molecular structures from scratch without using a pre-existing compound as a starting point [1] [2]. In an industry where traditional drug discovery is notoriously time-consuming and expensive, often exceeding a billion dollars per approved drug, de novo methods aim to automate the creation of chemical entities tailored to specific therapeutic targets and optimal drug-like properties [1]. The field has undergone a significant transformation, evolving from early conventional growth algorithms to the current state-of-the-art, which is dominated by generative artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning [2] [3]. This guide objectively compares the performance of these evolving methodologies, providing researchers with a clear framework for evaluating their application in modern drug discovery campaigns.

Core Principles of De Novo Design

The practice of de novo design is built upon several foundational principles that differentiate it from other computational approaches.

- Generation from Atomic or Fragment Building Blocks: Methods construct molecules either atom-by-atom or by assembling larger chemical fragments, exploring a chemical space estimated to contain up to 10^63 drug-like molecules [1] [2].

- Objective-Driven by Constraints: The generation process is guided by a set of constraints, which can be derived from the three-dimensional structure of a biological target (structure-based design) or from the properties of known active binders (ligand-based design) [2] [3].

- Multi-Parameter Optimization: Successful candidates must simultaneously satisfy multiple criteria, including biological activity, target selectivity, synthesizability, and favorable ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) profiles [1] [4].

- Integration within the Design-Make-Test-Analyze (DMTA) Cycle: The true impact of de novo design is realized when it is embedded within an iterative feedback loop, where computationally generated molecules are synthesized, tested experimentally, and the results are used to refine the next round of design [1] [3].

Table 1: Key Design Strategies and Their Applications

| Design Strategy | Core Principle | Typical Application Phase | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scaffold Hopping [1] | Modifying a molecule's core structure while maintaining similar biological activity. | Hit-to-Lead, Lead Optimization | Generates novel intellectual property while retaining efficacy. |

| Scaffold Decoration [1] | Adding functional groups to a core scaffold to enhance interactions with the target. | Hit-to-Lead, Lead Optimization | Fine-tunes properties like potency and selectivity. |

| Fragment-Based Design [1] | Growing, linking, or merging small, weakly-binding fragments into a single, high-affinity molecule. | Hit Discovery | Explores chemical space efficiently from small, simple starting points. |

| Chemical Space Sampling [1] | Selecting a diverse subset of molecules from the vast array of possibilities for further investigation. | Hit Discovery | Maximizes the potential for discovery by prioritizing diversity. |

Comparative Analysis of Methodologies

Conventional vs. Modern Machine Learning Approaches

Traditional de novo methods often relied on evolutionary algorithms and fragment-based assembly. While effective, these methods frequently proposed molecules that were difficult or impossible to synthesize, limiting their broad application [1] [2]. The introduction of generative AI around 2017 catalyzed a paradigm shift, enabling rapid, semi-automatic design and optimization [1].

Performance Benchmarking of AI Models

The following table synthesizes experimental data from benchmark studies, which evaluate models on tasks such as generating molecules with specific properties or optimizing for bioactivity.

Table 2: Benchmarking of Generative Models for De Novo Design

| Model / Framework | Architecture Type | Key Reported Performance Metrics | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| DRAGONFLY [3] | Interactome-based Deep Learning (GTNN + LSTM) | Outperformed fine-tuned RNNs on 67% of metrics for 20 macromolecular targets; achieved Pearson r ≥ 0.95 for property control [3]. | Ligand- and structure-based generation without task-specific fine-tuning. |

| Structured State-Space (S4) Model [5] | Structured State-Space Sequence Model | Superior performance in 67% of analyzed metrics compared to LSTM and GPT; generates structurally diverse molecules [5]. | General de novo design with long-sequence learning. |

| Fine-Tuned RNN (Baseline) [3] | Recurrent Neural Network | Baseline performance for comparison; generally outperformed by DRAGONFLY and S4 on novelty, synthesizability, and bioactivity [3]. | Ligand-based molecular generation. |

| MolScore Framework [6] | Benchmarking Platform | Unifies evaluation (e.g., GuacaMol, MOSES); integrates 2,337 pre-trained QSAR models and docking scores for holistic assessment [6]. | Objective scoring and benchmarking of generative models. |

Key findings from these benchmarks indicate that modern architectures like DRAGONFLY and S4 demonstrate superior ability to generate molecules that are not only bioactive but also novel and synthesizable, addressing critical limitations of earlier methods [3] [5]. The shift towards "zero-shot" or "few-shot" learning, as seen with DRAGONFLY, is particularly promising for accelerating the DMTA cycle by reducing the need for extensive, task-specific data and training [3].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The experimental validation of de novo designed molecules relies on a suite of computational and experimental tools.

Table 3: Key Reagents and Tools for De Novo Design Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| DRAGONFLY [3] | Generates novel molecules using drug-target interactome data. | Prospective design of PPARγ partial agonists confirmed by crystal structure [3]. |

| MolScore [6] | Provides multi-parameter scoring and benchmarking for generative models. | Configuring an objective function that combines docking score, similarity, and synthetic accessibility [6]. |

| Docking Software [6] | Predicts how a small molecule binds to a protein target. | Virtual screening of generated compound libraries to prioritize synthesis candidates. |

| QSAR Models [6] [3] | Predicts biological activity based on molecular structure. | Pre-screening for on-target bioactivity using pre-trained models (e.g., on ChEMBL data) [6]. |

| Retrosynthetic Tools (e.g., AiZynthFinder, RAScore) [6] [3] | Evaluates the synthesizability of a proposed molecule. | Filtering out generated structures with low synthetic feasibility before experimental efforts [3]. |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

To ensure reliability, methodologies must be validated through standardized protocols. Below is a core workflow for evaluating a generative model's performance, integrating tools like MolScore.

Detailed Methodology

- Objective Definition: Clearly define the multi-parameter objective. For example: "Generate novel inhibitors for kinase X with a predicted pIC50 > 7, similarity to known actives (Tanimoto < 0.5), and obeying Lipinski's Rule of Five." [6]

- Benchmark Configuration: Using a framework like MolScore, configure the scoring functions to reflect the objective. This typically involves:

- Bioactivity Prediction: Utilizing pre-trained QSAR models from databases like ChEMBL or structure-based docking simulations [6] [3].

- Physicochemical & ADMET Properties: Calculating molecular descriptors (e.g., LogP, molecular weight) and applying predictive filters [2].

- Synthesizability Assessment: Employing a metric like the Retrosynthetic Accessibility score (RAScore) to penalize molecules that are difficult to make [3].

- Novelty & Diversity Checks: Ensuring generated molecules are new and structurally diverse compared to a reference set of known actives [6].

- Library Generation & Scoring: Run the generative model (e.g., S4, DRAGONFLY) for a set number of steps. In each step, the model proposes new molecules, which MolScore validates, scores, and filters to produce a final "desirability score" between 0 and 1 for each molecule [6].

- Performance Evaluation: After the run, evaluate the model's output using a standardized suite of metrics, such as those from the MOSES benchmark. Key metrics include Validity (percentage of chemically valid SMILES), Uniqueness, Novelty (not in the training set), and Fréchet ChemNet Distance (FCD) which measures how closely the distribution of generated molecules matches the distribution of real drug-like molecules [6].

- Prospective Validation: The highest-ranking generated molecules are then chemically synthesized and subjected to in vitro and in vivo testing (e.g., binding assays, functional assays) to confirm the model's predictions. A successful outcome, such as the determination of a co-crystal structure matching the predicted binding mode, provides the strongest validation [3].

Industry Impact and Future Outlook

The impact of AI-driven de novo design is already materializing. Drugs developed using these methods, such as DSP-1181, EXS21546, and DSP-0038, have progressed to clinical trials [1]. The successful prospective application of the DRAGONFLY framework to design potent partial agonists for the PPARγ nuclear receptor, later confirmed by a crystal structure, stands as a landmark achievement for the field [3].

Future developments will likely focus on improving the accuracy of "zero-shot" generation, better integration of synthetic complexity during the design phase, and a more holistic evaluation of generated molecules that moves beyond computational benchmarks to real-world efficacy and safety [1] [6] [3]. As these tools become more sophisticated and integrated into the pharmaceutical industry's workflow, they hold the promise of substantially reducing the time and cost associated with bringing new, life-saving treatments to patients.

The pursuit of new therapeutic entities is a fundamental challenge in biomedical research, traditionally characterized by immense costs and time-intensive processes. The emergence of de novo drug design, which involves creating molecular candidates with specific properties from scratch, represents a paradigm shift in addressing this challenge [1]. This approach aims to automate the creation of new chemical structures tailored to specific molecular characteristics, leveraging knowledge from existing, effective molecules to design novel ones with unique structural features [1].

The core of this revolution lies in how molecules are represented computationally. The vast 'chemical universe' is estimated to contain up to 10^60 drug-like molecular entities, posing a significant challenge to de novo design [7]. The evolution from simple string-based notations to sophisticated, AI-driven embeddings is reshaping how researchers explore this chemical space, moving from manual, rule-based systems to models that can learn and generate molecular structures with desired pharmaceutical properties. This article charts this evolution, providing a detailed comparison of molecular representation methods and their impact on the efficiency and success of modern drug discovery.

The Foundational Role of SMILES and SELFIES

The journey into computational molecular representation began with line notations that translate molecular structures into machine-readable strings. The Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) emerged as one of the most widely adopted representations, offering a concise and human-readable format for representing chemical structures using ASCII characters to depict atoms and bonds within a molecule [8]. For instance, the molecule climbazole is represented as CC(C)(C)C(=O)C(N1C=CN=C1)OC2=CC=C(C=C2)Cl [9]. This simplicity facilitated the exchange and analysis of chemical information by researchers and led to its widespread adoption in cheminformatics databases like PubChem [8].

However, despite its extensive use, SMILES notation possesses significant limitations that impact its performance in generative AI models:

- Robustness Issues: SMILES can generate semantically invalid strings when used in generative models, often resulting in invalid molecule outputs that hamper automated approaches to molecule design and discovery [8].

- Representation Ambiguity: A single SMILES string can correspond to multiple molecules, or conversely, different strings can represent the same molecule, creating complications in database searches and comparative studies [8].

- Structural Limitations: SMILES sometimes struggles to represent certain chemical classes like organometallic compounds or complex biological molecules [8].

To address these limitations, SELF-Referencing Embedded Strings (SELFIES) was developed as a more robust alternative. Unlike SMILES, every SELFIES string guarantees a molecule representation without semantic errors [8]. This robustness is crucial in computational chemistry applications, particularly in molecule design using models like Variational Auto-Encoders (VAE). Experiments have shown that SELFIES consistently produces molecules with random mutations of valid strings, while SMILES often generates invalid strings when mutated [8].

Table 1: Comparison of SMILES and SELFIES Representations

| Feature | SMILES | SELFIES |

|---|---|---|

| Validity Guarantee | No - can generate invalid structures | Yes - always produces valid molecular structures |

| Representation Consistency | Single molecule can have multiple representations | More consistent representation |

| Handling Complex Molecules | Struggles with organometallics and complex biological molecules | Better handling of complex chemical classes |

| Usage in Generative Models | May require extensive filtering of invalid outputs | More reliable for automated molecular generation |

| Adoption & Support | Widely adopted and supported | Growing but less widespread support |

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Evaluation of Molecular Representations

Evaluating the performance of different molecular representations requires examining their performance across specific drug discovery tasks. Recent research has provided quantitative insights into how these representations impact model accuracy and efficiency.

Tokenization Methods in Chemical Language Models

A critical aspect of using string-based molecular representations in AI models is tokenization - how these strings are broken down into smaller units for processing by machine learning algorithms. Recent research has introduced novel tokenization approaches that significantly impact model performance:

- Byte Pair Encoding (BPE): A traditional tokenization method that iteratively merges the most frequent pairs of characters or tokens [8].

- Atom Pair Encoding (APE): A novel approach specifically designed for chemical languages that preserves the integrity and contextual relationships among chemical elements [8].

Research comparing these tokenization methods revealed that APE, particularly when used with SMILES representations, significantly outperforms BPE in classification tasks [8]. The study evaluated performance using ROC-AUC metrics across three distinct datasets for HIV, toxicology, and blood-brain barrier penetration, demonstrating that APE enhances classification accuracy by better preserving chemical structural integrity [8].

Hybrid Fragment-SMILES Tokenization for ADMET Prediction

Another innovative approach combines the advantages of fragment-based and character-level representations through hybrid tokenization. This method leverages both SMILES strings and molecular fragments - sub-molecules containing specific functional groups or motifs relevant for physicochemical properties [9].

Research findings indicate that while an excess of fragments can impede performance, using hybrid tokenization with high-frequency fragments enhances results beyond base SMILES tokenization alone [9]. This hybrid approach advances the potential of integrating fragment- and character-level molecular features within Transformer models for ADMET property prediction.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Molecular Representation Methods

| Representation Method | Model Architecture | Application | Performance Metrics | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMILES + BPE | BERT-based models | Biophysics/physiology classification | ROC-AUC | Baseline performance |

| SMILES + APE | BERT-based models | Biophysics/physiology classification | ROC-AUC | Significant improvement over BPE |

| SELFIES + BPE | BERT-based models | Biophysics/physiology classification | ROC-AUC | Comparable to SMILES with same tokenization |

| Hybrid Fragment-SMILES | Transformer | ADMET prediction | Various metrics | Enhanced results over SMILES alone with optimal fragments |

| Graph Representations | Graph Neural Networks | Molecular property prediction | Varies by study | Captures structural information effectively |

Emerging Architectures: From Language Models to Geometric Representations

The evolution of molecular representations has progressed beyond simple string-based approaches to incorporate more sophisticated AI-driven architectures that capture richer structural information.

Chemical Language Models (CLMs)

Chemical language models represent a significant advancement by borrowing methods from natural language processing and adapting them to molecules represented as strings like SMILES [7]. These models learn the distribution of molecules in training sets, then generate molecules similar to but different from those in the training sets [10]. When combined with evolutionary algorithms or reinforcement learning, the properties of generated molecules can be further optimized [10].

Several neural network architectures have been successfully applied to CLMs:

- Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs): Particularly those with Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU), can learn the low-dimensional distribution of molecular sequence grammar and chemical space with SMILES representations as input [10]. These models can automatically generate molecular structures with high drug-like properties with efficacy as high as over 90% [10].

- Variational Autoencoders (VAE): These consist of an encoder that maps input molecular structure into latent variables and a decoder that recovers the hidden variables to the SMILES sequence [10]. This creates a "feature space" or "drug space" representing the complete set of targeted drugs.

- Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs): These employ two neural networks - a generator that produces random SMILES and a discriminator that distinguishes these from real molecules in the training set [10]. Through adversarial training, the generator learns to produce increasingly realistic molecular representations.

Graph-Based and 3D Representations

While SMILES and SELFIES operate as 1D string representations, more advanced approaches directly model molecular structure as graphs or 3D geometries:

- Graph Representations: These model atoms as nodes and bonds as edges, naturally capturing molecular topology. Architectures like Graph Transformer-based Generative Adversarial Networks have been developed for target-specific de novo design of drug candidate molecules [11]. For example, DrugGEN, an end-to-end generative system, represents molecules as graphs and processes them using a generative adversarial network comprising graph transformer layers [11].

- 3D Structure-Based Models: Emerging approaches like equivariant diffusion models generate molecules in 3D space based on protein pockets, incorporating critical spatial and structural information for drug-target interactions [11].

The following diagram illustrates the evolutionary pathway of molecular representations from traditional notations to modern AI-driven approaches:

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

To ensure reproducibility and provide clear insights into the comparative evaluation of molecular representations, this section details key experimental methodologies from cited research.

Tokenization Comparison Protocol

The experimental protocol for comparing tokenization methods, as described in the SMILES and SELFIES tokenization study, follows this workflow [8]:

Detailed Methodology [8]:

- Datasets: Three distinct datasets for HIV, toxicology, and blood-brain barrier penetration were used to ensure comprehensive evaluation across different biophysics and physiology classification tasks.

- Representation Conversion: All molecules were converted to both SMILES and SELFIES representations to enable direct comparison.

- Tokenization Application: Both BPE and APE tokenization methods were applied to each representation type.

- Model Architecture: BERT-based transformer models were implemented with consistent architecture across all experiments.

- Evaluation Metric: Performance was evaluated using ROC-AUC as the primary metric, with statistical significance testing to validate results.

- Analysis: Comparative analysis focused on how tokenization techniques influence the performance of chemical language models.

Hybrid Tokenization Methodology

The hybrid fragment-SMILES tokenization approach follows this experimental design [9]:

- Fragment Library Construction: Molecules are broken apart into smaller pieces to reveal important structural and functional features not easily discernible from atomic-level representation.

- Frequency Analysis: Fragments are analyzed for occurrence frequency, with a significant number found to appear rarely.

- Cutoff Application: Various models with varying frequency cutoffs are constructed to produce a fragment spectrum of models.

- Hybrid Encoding: Fragment and SMILES representations are combined using a hybrid encoding technique.

- Pre-training Strategies: Both one-phase and two-phase pre-training techniques are employed.

- Model Evaluation: Performance is assessed using the MTL-BERT model, an encoder-only Transformer that achieves state-of-the-art ADMET predictions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

To facilitate practical implementation of these molecular representation techniques, the following table details key computational tools and resources referenced in the research:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Molecular Representation Research

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| SMILES Strings | Molecular Representation | Text-based representation of chemical structures | Foundation for chemical language models |

| SELFIES Strings | Molecular Representation | Robust molecular representation guaranteeing validity | Generative models where validity is crucial |

| Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) | Tokenization Algorithm | Sub-word tokenization by merging frequent character pairs | Baseline tokenization for chemical language models |

| Atom Pair Encoding (APE) | Tokenization Algorithm | Chemical-aware tokenization preserving element relationships | Enhanced classification accuracy in BERT models |

| Transformer Architecture | Model Framework | Self-attention based neural network architecture | State-of-the-art ADMET prediction models |

| Fragment Libraries | Molecular Fragments | Collection of sub-molecular structural units | Hybrid tokenization approaches |

| BERT-based Models | Pre-trained Models | Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers | Transfer learning for chemical tasks |

| Chemical Databases (e.g., ChEMBL) | Data Resource | Curated collections of bioactive molecules | Training data for generative models |

The evolution of molecular representations from simple line notations to sophisticated AI-driven embeddings represents a fundamental transformation in de novo drug design. SMILES established a crucial foundation for computational chemistry, while SELFIES addressed critical validity limitations for generative applications. The emergence of advanced tokenization methods like APE and hybrid fragment-SMILES approaches has further enhanced model performance by preserving chemical integrity and incorporating meaningful structural motifs.

Current state-of-the-art approaches increasingly leverage graph-based representations and geometric deep learning that naturally capture molecular topology and 3D structure. As these methods continue to evolve, the integration of multi-modal representations combining strengths of different approaches shows particular promise for advancing predictive accuracy and generative capability in drug discovery.

The quantitative comparisons presented in this article demonstrate that while no single representation excels universally across all applications, the strategic selection and innovation of molecular representations directly impacts the success of AI-driven drug discovery. Researchers must therefore carefully consider representation choices based on their specific task requirements, whether prioritizing validity guarantees, structural richness, or predictive performance for particular pharmaceutical properties.

Scaffold hopping, also known as lead hopping, is a fundamental strategy in modern drug discovery aimed at identifying isofunctional molecular structures that share similar biological activity but possess chemically different core structures [12] [13]. First introduced as a formal concept in 1999 by Schneider et al., scaffold hopping has since evolved into a sophisticated discipline that enables medicinal chemists to discover novel chemotypes while maintaining desired pharmacological properties [12] [14]. This approach serves multiple critical purposes in drug development: it provides a path to overcome undesirable properties of lead compounds such as toxicity or metabolic instability; it enables the creation of novel patentable structures that circumvent existing intellectual property; and it facilitates the exploration of broader chemical space to identify backup candidates for promising leads [12] [14] [15].

The central premise of scaffold hopping rests on the preservation of key pharmacophore features—the spatial arrangement of functional groups essential for biological activity—while fundamentally altering the molecular scaffold that connects these features [13] [15]. This strategy appears to contradict the similarity-property principle, which states that structurally similar molecules tend to have similar properties; however, it successfully operates because scaffolds with different connectivity can still position critical pharmacophore elements in similar three-dimensional orientations [12]. The effectiveness of scaffold hopping is exemplified by numerous successful drug pairs throughout pharmaceutical history, including the transformation from morphine to tramadol through ring opening, and the development of vardenafil as a scaffold hop from sildenafil through heterocyclic replacements [12] [13].

Classification of Scaffold Hopping Approaches

Scaffold hopping strategies can be systematically categorized based on the structural relationship between original and modified compounds. Sun et al. (2012) classified these approaches into four major categories of increasing complexity and structural deviation [12] [14]. Understanding these categories provides medicinal chemists with a conceptual framework for designing scaffold hopping campaigns.

Heterocycle Replacements

Heterocycle replacements represent the smallest degree of structural change in scaffold hopping, typically involving the swapping of carbon and heteroatoms within aromatic rings or the replacement of one heterocycle with another [12]. This approach constitutes a 1° hop according to the classification system proposed by Boehm et al., where scaffolds are considered different if they require distinct synthetic routes, regardless of the apparent structural similarity [12]. A classic example includes the development of vardenafil from sildenafil, where a subtle rearrangement of nitrogen atoms within the fused ring system resulted in a distinct patentable entity while maintaining PDE5 inhibitory activity [12] [13]. Similarly, the COX-2 inhibitors rofecoxib (Vioxx) and valdecoxib (Bextra) differ primarily in their 5-membered heterocyclic rings connecting two phenyl rings, yet were developed and marketed by different pharmaceutical companies [12].

Ring Opening or Closure

Ring opening and closure strategies involve more significant structural modifications, classified as 2° hops, where ring systems are either opened to increase molecular flexibility or closed to reduce conformational entropy [12]. The transformation from morphine to tramadol represents a historic example of ring opening, where three fused rings were opened to create a more flexible molecule with reduced side effects and improved oral bioavailability [12]. Conversely, the development of cyproheptadine from pheniramine demonstrates ring closure, where both aromatic rings were connected to lock the molecule into its active conformation, significantly improving binding affinity to the H1-receptor and enabling additional medical benefits in migraine prophylaxis through 5-HT2 serotonin receptor antagonism [12].

Peptidomimetics

Peptidomimetics involves replacing peptide backbones with non-peptide moieties while maintaining the ability to interact with biological targets typically recognized by peptides or proteins [12]. This approach is particularly valuable for developing drug-like molecules from peptide leads, which often suffer from poor pharmacokinetic properties. Cresset Group's consulting team has demonstrated successful application of this strategy through field-based scaffold hopping, transforming a therapeutically interesting peptide AMP1 analogue into a small non-peptide synthetic mimetic while conserving electrostatic field properties [15]. This method enables the transition from complex natural products to synthetically tractable small molecules with improved drug-like properties.

Topology-Based Hopping

Topology-based hopping represents the most significant degree of structural alteration, where the overall shape and spatial arrangement of pharmacophores are maintained despite fundamental changes in molecular connectivity [12]. This approach can lead to high degrees of structural novelty and is often facilitated by computational methods that analyze three-dimensional molecular properties rather than two-dimensional connectivity [12] [13]. Methods such as feature trees (FTrees) analyze the overall topology and fuzzy pharmacophore properties of molecules, enabling identification of structurally diverse compounds with similar biological activity by navigating chemical space based on molecular descriptors rather than structural similarity [13].

Table 1: Classification of Scaffold Hopping Strategies

| Category | Degree of Change | Key Characteristics | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heterocycle Replacements | 1° (Small) | Swapping atoms in aromatic rings; replacing heterocycles | Sildenafil to Vardenafil; Rofecoxib to Valdecoxib |

| Ring Opening/Closure | 2° (Medium) | Opening fused rings to increase flexibility; closing rings to reduce conformational entropy | Morphine to Tramadol (opening); Pheniramine to Cyproheptadine (closure) |

| Peptidomimetics | 2°-3° (Medium-Large) | Replacing peptide backbones with non-peptide moieties | AMP1 peptide analogue to small synthetic mimetic |

| Topology-Based Hopping | 3° (Large) | Maintaining 3D shape and pharmacophore arrangement despite fundamental connectivity changes | FTrees-based identification of structurally diverse analogs |

Computational Methods for Scaffold Hopping

The rise of sophisticated computational methods has dramatically transformed scaffold hopping from a serendipitous art to a systematic science. These approaches can be broadly categorized into traditional rule-based methods and modern artificial intelligence-driven techniques, each with distinct advantages and applications.

Traditional Computational Approaches

Traditional scaffold hopping methods rely on well-established computational techniques that utilize explicit molecular representations and similarity metrics. Virtual screening through molecular docking predicts potential binders by assessing complementary between small molecules and target binding sites, offering the advantage of discovering chemically unrelated candidates without structural information from known binders [13]. Pharmacophore constraints can enhance success rates by ensuring generated molecular poses feature critical interactions with the target [13]. Topological replacement methods, implemented in tools like SeeSAR's ReCore functionality, identify molecular fragments with similar 3D coordination of connection points, enabling rational substitution of core structures while maintaining decoration geometry [13]. Shape similarity approaches, valuable when limited target information is available, screen for compounds sharing similar molecular shape and pharmacophore feature orientation to query molecules [13].

Feature-based similarity methods, such as Feature Trees (FTrees), analyze overall molecular topology and "fuzzy" pharmacophore properties, translating this data into molecular descriptors that facilitate identification of structurally diverse compounds with similar feature arrangements [13]. These traditional methods have proven successful in numerous applications but face limitations in exploring novel chemical regions beyond predefined rules and expert knowledge [14].

AI-Driven Molecular Representation and Generation

Artificial intelligence has revolutionized scaffold hopping through advanced molecular representation methods and generative models that transcend traditional rule-based approaches [14]. Modern AI-driven methods employ deep learning techniques to learn continuous, high-dimensional feature embeddings directly from complex molecular datasets, capturing both local and global molecular characteristics that may be overlooked by traditional methods [14].

Language model-based representations adapt natural language processing techniques to molecular design by treating Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) strings or other string-based representations as chemical "languages" [14]. Graph-based representations utilize graph neural networks (GNNs) to directly model molecular graph structures, enabling comprehensive capture of atomic relationships and connectivity patterns [14]. Reinforcement learning approaches, such as the RuSH (Reinforcement Learning for Unconstrained Scaffold Hopping) framework, employ iterative optimization processes where AI agents learn to generate molecules with high three-dimensional and pharmacophore similarity to reference compounds but low scaffold similarity [16] [17]. These AI-driven methods significantly expand exploration of chemical space and facilitate discovery of novel scaffolds that maintain target bioactivity.

Table 2: Computational Methods for Scaffold Hopping

| Method Category | Key Technologies | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Virtual Screening | Molecular docking, pharmacophore constraints | Can discover chemically unrelated candidates; structure-based approach | Dependent on quality of target structure; computationally intensive |

| Topological Replacement | ReCore, connection vector similarity | Maintains geometry of decorations; rational scaffold substitution | Limited to known fragment libraries; may miss novel geometries |

| Shape Similarity | ROCS, molecular superposition | Effective when target structure unknown; ligand-based approach | May overemphasize shape over specific interactions |

| Feature-Based Similarity | FTrees, molecular descriptors | Identifies distant structural relatives; fuzzy pharmacophore matching | Requires careful parameter tuning; complex interpretation |

| AI-Driven Generation | Reinforcement learning (RuSH), GNNs, transformers | Unconstrained exploration; data-driven novelty; optimizes multiple properties | Requires large datasets; potential synthetic accessibility issues |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Implementing successful scaffold hopping campaigns requires systematic experimental protocols that integrate computational design with experimental validation. The following sections detail established workflows and methodologies.

Reinforcement Learning Framework (RuSH)

The RuSH approach represents a cutting-edge methodology for scaffold hopping using reinforcement learning with unconstrained molecule generation [17]. This framework consists of a multi-stage process beginning with molecule generation using long short-term memory (LSTM) networks trained on drug-like molecules from databases such as ChEMBL [17]. These generative models act as initial "priors" that can be further fine-tuned through transfer learning with reference bioactive molecules.

The reinforcement learning agent generates SMILES strings (64 per epoch in the published implementation), which are subsequently scored using a specialized scoring function that combines two-dimensional scaffold dissimilarity rewards with three-dimensional shape and pharmacophore similarity rewards [17]. The ScaffoldFinder algorithm identifies inclusion of reference decorations in generated designs via maximum common substructure matching, allowing parametric "fuzziness" to enable generative exploration [17]. A partial reward system addresses sparse reward problems in reinforcement learning by awarding intermediate scores to designs containing some but not all reference decorations [17].

For three-dimensional assessment, an ensemble of geometry-optimized conformers (up to 32 per enumerated stereoisomer) is generated using tools like OMEGA, with each conformer compared to the crystallographic reference pose using Rapid Overlay of Chemical Structures (ROCS) for shape and "color" (pharmacophore) similarity scoring [17]. The final score combines 2D and 3D rewards through a weighted harmonic mean, ensuring balanced optimization of both objectives [17]. A diversity filter prevents overrepresentation of specific Bemis-Murcko scaffolds and stores high-scoring designs for subsequent analysis [17].

Virtual Screening Workflow with Blaze

Cresset's Blaze software implements a virtual screening workflow for scaffold hopping that begins with preparation of the reference molecule and target protein structure [15]. The software generates a set of interaction fields that capture the molecule's electrostatic and shape properties, which are used to search commercial compound vendor collections for potential replacements [15]. Results are ranked by field similarity scores, followed by docking studies to validate binding modes and interaction conservation [15]. This approach enables identification of "whole molecule" replacements with novel scaffolds that maintain critical interactions with the biological target [15].

Fragment Replacement with Spark

The Spark software implements a fragment-based scaffold hopping approach through systematic replacement of molecular components [15]. The process begins with fragmentation of the reference molecule into core and substituent regions, followed by searching for alternative fragments that maintain similar attachment geometry and interaction patterns [15]. Reconstructed molecules are scored based on their field similarity to the original compound, with top-ranking candidates selected for synthesis and biological testing [15]. This method is particularly valuable for lead optimization scenarios where specific molecular liabilities need to be addressed while maintaining core pharmacological activity [15].

Comparative Analysis of Scaffold Hopping Methods

Evaluating the performance of different scaffold hopping approaches requires examination of multiple criteria, including scaffold novelty, preservation of bioactivity, computational efficiency, and synthetic accessibility.

Performance Metrics and Benchmarking

The RuSH framework has demonstrated promising results in scaffold hopping case studies across multiple protein targets, including PIM1 kinase, HIV1 protease, JNK3, and soluble adenyl cyclase (ADCY10) [17]. In these studies, RuSH successfully generated molecules with high three-dimensional similarity to reference compounds (ROCS shape and color scores >1.0 in optimal cases) while achieving significant scaffold divergence (Tanimoto distances on ECFP fingerprints approaching 0.7-0.9 for scaffold dissimilarity) [17]. Comparative analysis with established methods like DeLinker and Link-INVENT revealed advantages in unconstrained generation, with RuSH producing molecules with better three-dimensional property conservation and broader scaffold diversity [17].

Traditional fingerprint-based methods typically achieve successful scaffold hops in 10-30% of cases depending on the target and similarity thresholds, with performance varying significantly based on molecular complexity and the specific fingerprint algorithm employed [14]. Field-based methods like those implemented in Cresset's software have demonstrated success rates of 20-40% in prospective applications, particularly for targets with well-defined binding pockets and strong electrostatic requirements [15].

Application-Specific Considerations

The optimal scaffold hopping strategy varies significantly depending on the specific application context and available structural information. For hit-to-lead optimization where speed and intellectual property generation are priorities, virtual screening of commercial compound collections using tools like Blaze offers rapid identification of novel scaffolds with confirmed availability [15]. For lead optimization scenarios with specific property liabilities, fragment replacement approaches using Spark provide controlled exploration of structural alternatives while maintaining key interactions [15]. When maximum scaffold novelty is required, AI-driven approaches like RuSH offer the greatest potential for exploring uncharted chemical territory, though potentially at the cost of increased synthetic challenges [17].

The availability of structural information significantly influences method selection. When high-quality target structures are available, structure-based methods including docking and pharmacophore-constrained virtual screening typically yield superior results [13]. For targets with limited structural information, ligand-based approaches including shape similarity and field-based methods provide viable alternatives [13] [15].

Table 3: Application-Based Method Selection Guide

| Application Context | Recommended Methods | Key Considerations | Expected Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hit-to-Lead (Fast Follower) | Virtual screening (Blaze), similarity searching | Compound availability; IP position; rapid results | Novel scaffolds with confirmed availability; patentable leads |

| Lead Optimization (Liability Mitigation) | Fragment replacement (Spark), topological replacement | Specific property improvement; synthetic tractability | Controlled scaffold modifications; improved ADMET properties |

| Maximum Novelty Exploration | AI-driven generation (RuSH), topology-based hopping | Exploration breadth; synthetic accessibility assessment | High scaffold diversity; potential for breakthrough designs |

| Peptide-to-Small Molecule | Field-based methods, peptidomimetics | Conservation of key interactions; drug-likeness | Orally available small molecules from peptide leads |

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful implementation of scaffold hopping campaigns requires access to specialized computational tools and compound resources. The following table outlines key solutions available to researchers.

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for Scaffold Hopping

| Tool/Resource | Type | Key Functionality | Application in Scaffold Hopping |

|---|---|---|---|

| SeeSAR | Interactive software | Molecular docking, pharmacophore constraints, similarity scanning | Virtual screening with pharmacophore constraints; rapid evaluation of scaffold alternatives |

| ReCore (SeeSAR) | Fragment replacement | Topological replacement based on 3D connection vectors | Rational scaffold substitution while maintaining decoration geometry |

| FTrees (infiniSee) | Chemical space navigation | Feature tree-based similarity searching using molecular descriptors | Identification of structurally diverse compounds with similar pharmacophore features |

| Blaze (Cresset) | Virtual screening software | Field-based similarity searching of compound databases | Whole molecule replacement with novel scaffolds; commercial compound sourcing |

| Spark (Cresset) | Fragment replacement software | Systematic molecular fragment replacement with scoring | Idea generation for synthetic targets; fragment-based scaffold optimization |

| RuSH Framework | AI-generated platform | Reinforcement learning for unconstrained scaffold hopping | Maximum novelty exploration; multi-parameter optimization |

| ROCS | Shape similarity tool | Rapid overlay and comparison of 3D molecular shapes | 3D similarity assessment for ligand-based scaffold hopping |

| ZINC Database | Compound library | Commercially available compounds for virtual screening | Source of purchasable compounds for experimental validation |

| ChEMBL Database | Bioactivity database | Curated bioactive molecules with target annotations | Training data for AI models; reference compounds for similarity searching |

Scaffold hopping has evolved from a serendipitous medicinal chemistry practice to a systematic discipline powered by sophisticated computational methods. The strategic replacement of molecular cores while preserving bioactivity represents a cornerstone of modern drug discovery, enabling intellectual property generation, liability mitigation, and exploration of novel chemical space. Traditional approaches including heterocycle replacements, ring opening/closure, peptidomimetics, and topology-based strategies provide established conceptual frameworks for scaffold design, while contemporary computational methods ranging from virtual screening to AI-driven generative models offer increasingly powerful implementation pathways.

The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that method selection must be guided by specific project needs, available structural information, and desired outcomes. Virtual screening approaches offer practical solutions for rapid identification of purchasable compounds, while fragment replacement enables controlled optimization of specific molecular regions. AI-driven generation methods like RuSH represent the cutting edge for maximal novelty exploration, though requiring careful consideration of synthetic accessibility. As computational power continues to grow and algorithms become increasingly sophisticated, the integration of multiple approaches within structured workflows will likely yield the most successful scaffold hopping campaigns, accelerating the discovery of novel bioactive compounds to address unmet medical needs.

The traditional drug discovery process is notoriously slow and inefficient, taking over a decade and costing approximately $2.6 billion on average for a new drug to reach the market, with a failure rate exceeding 90% [18] [19]. De novo drug design—the computational process of generating novel molecular structures from scratch—has emerged as a powerful strategy to combat these challenges. By exploring the vast chemical space more efficiently than traditional high-throughput screening (HTS), these methods aim to accelerate early discovery timelines and design compounds with optimized properties from the outset, thereby reducing late-stage attrition [2] [1]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of contemporary de novo design methodologies, evaluating their performance in generating bioactive, synthesizable, and novel compounds against industry benchmarks.

Comparative Analysis of De Novo Drug Design Methodologies

The landscape of de novo drug design has evolved from conventional computational growth algorithms to advanced generative artificial intelligence (AI) models. The table below compares the core approaches, their underlying technologies, and key performance drivers.

Table 1: Comparison of De Novo Drug Design Methodologies

| Methodology | Core Technology | Key Drivers for Accelerating Timelines | Key Drivers for Reducing Attrition | Representative Tools/Algorithms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structure-Based Design | Molecular docking, scoring functions, fragment-based sampling [2] | Rapid exploration of chemical space without synthesis; direct targeting of protein active sites [2] | Optimizes binding affinity and selectivity early; improves likelihood of target engagement [2] | LUDI, SPROUT, CONCERTS [2] |

| Ligand-Based Design | Pharmacophore modeling, QSAR, similarity search [2] | No need for protein structural data; fast generation based on known active compounds [2] | Leverages proven bioactive scaffolds; can predict and maintain favorable ADMET properties [2] [1] | TOPAS, SYNOPSIS, DOGS [2] |

| Generative AI: Chemical Language Models (CLMs) | Deep Learning (LSTM, Transformer), NLP on SMILES strings [3] [7] | "Zero-shot" generation of novel compound libraries tailored to specific properties without application-specific fine-tuning [3] | Explicitly designed for synthesizability and drug-likeness; integration of predictive bioactivity models [3] [1] | DRAGONFLY, Fine-tuned RNNs [3] |

| Generative AI: Deep Interactome Learning | Graph Neural Networks (GNN), CLMs [3] | Combines ligand and 3D protein structure information for targeted design; no need for transfer learning [3] | Incorporates complex drug-target interaction networks; demonstrates prospective success in generating potent, selective agonists [3] | DRAGONFLY (GTNN + LSTM) [3] |

| Reinforcement Learning (RL) | Reinforcement Learning, RNNs, Transformers [20] | Efficiently navigates vast chemical space towards a property goal without labeled data [20] | Advanced frameworks (e.g., ACARL) model complex Structure-Activity Relationships (SAR) and "activity cliffs" [20] | ACARL, REINVENT [20] |

Performance Benchmarking and Experimental Data

Prospective experimental validation is the ultimate benchmark for any de novo design method. The following table summarizes key experimental results from recent state-of-the-art studies.

Table 2: Experimental Benchmarking of Generated Compounds

| Evaluation Metric | Deep Interactome Learning (DRAGONFLY) [3] | Activity Cliff-Aware RL (ACARL) [20] | Standard Chemical Language Models (CLMs) [3] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Protein | Human PPARγ (Nuclear Receptor) [3] | Multiple relevant protein targets [20] | 20 well-studied targets (e.g., nuclear receptors, kinases) [3] |

| Reported Bioactivity | Potent partial agonists with favorable selectivity profiles [3] | Superior binding affinity compared to state-of-the-art baselines [20] | Variable performance, often inferior to interactome-based methods [3] |

| Structural Validation | Crystal structure of ligand-receptor complex confirmed anticipated binding mode [3] | Not explicitly mentioned | N/A |

| Synthesizability | Top-ranking designs were chemically synthesized [3] | Framework considers synthetic accessibility | RAScore assessment integrated [3] |

| Novelty | Structural novelty confirmed [3] | Generates diverse structures [20] | Lower novelty scores compared to DRAGONFLY [3] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear framework for evaluation, this section details the core experimental methodologies cited in the performance benchmarks.

Protocol 1: Prospective Validation with Deep Interactome Learning [3] This protocol outlines the procedure for the prospective generation and validation of novel PPARγ agonists using the DRAGONFLY framework.

- Model Input and Setup: The DRAGONFLY model, pre-trained on a drug-target interactome (~263,000 bioactivities from ChEMBL for structure-based design), is utilized. The input is the 3D structure of the PPARγ binding site.

- Molecular Generation: The model generates novel molecular structures using its graph-to-sequence (GTNN + LSTM) architecture without further fine-tuning. Generation is constrained by desired physicochemical properties (e.g., molecular weight, lipophilicity).

- In Silico Evaluation: Generated molecules are ranked using a combination of:

- QSAR Models: Kernel Ridge Regression (KRR) models trained on ECFP4, CATS, and USRCAT descriptors predict pIC50 values for PPARγ.

- Synthesizability: The Retrosynthetic Accessibility Score (RAScore) filters for readily synthesizable compounds.

- Novelty: A rule-based algorithm quantifies scaffold and structural novelty against known bioactive molecules.

- Experimental Validation: Top-ranking designs are:

- Chemically synthesized.

- Characterized biophysically and biochemically for PPARγ activity and selectivity against related nuclear receptors.

- Subjected to X-ray crystallography to determine the ligand-receptor complex structure.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Activity Cliff-Aware Reinforcement Learning [20] This protocol describes the training and evaluation of the ACARL model, which is designed to navigate complex structure-activity landscapes.

- Problem Formulation: De novo design is framed as a combinatorial optimization problem: (\arg \max_{x\in \mathcal{S}} f(x)), where (f) is a molecular scoring function (e.g., docking score).

- Activity Cliff Identification: An Activity Cliff Index (ACI) is calculated for molecular pairs from databases like ChEMBL. The ACI quantifies the disparity between high structural similarity (e.g., Tanimoto similarity) and large differences in biological activity (e.g., pKi).

- Model Training:

- Base Model: A transformer decoder is pre-trained as a chemical language model on a large corpus of SMILES strings.

- Reinforcement Learning Fine-tuning: The model is fine-tuned using a proprietary reinforcement learning (RL) framework. A novel contrastive loss function is applied to explicitly amplify the influence of identified activity cliff compounds during RL, guiding the generator towards high-impact regions of the chemical space.

- Experimental Evaluation:

- Targets: ACARL is evaluated on multiple biologically relevant protein targets.

- Benchmarking: The model's performance in generating high-affinity molecules is compared against other state-of-the-art RL-based and generative models.

- Oracle: Structure-based docking software, which authentically reflects activity cliffs, is used as the scoring function to evaluate generated molecules.

Visualizing Workflows and Relationships

The following diagrams illustrate the key experimental workflows and conceptual relationships described in this guide.

Deep Interactome Learning Workflow

Activity Cliff-Aware Reinforcement Learning

Successful implementation and validation of de novo drug design methods rely on a suite of computational and experimental resources.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in De Novo Design | Relevance to Drivers |

|---|---|---|---|

| ChEMBL [3] [20] | Database | Public repository of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties and annotated binding affinities. | Provides curated data for model training and validation; reduces noise in initial target identification. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) [2] [19] | Database | Source of 3D structural data for biological macromolecules, primarily proteins. | Enables structure-based design; critical for assessing target druggability and defining active sites. |

| Chemical Language Model (CLM) [3] [7] | Software/Tool | Generates novel molecular structures represented as text strings (e.g., SMILES). | Accelerates exploration of chemical space; enables "zero-shot" design without starting templates. |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) [3] [19] | Software/Tool | Processes molecular graph structures to learn complex representations of molecules and binding sites. | Improves prediction of drug-target interactions by learning from interactome networks. |

| Retrosynthetic Accessibility Score (RAScore) [3] | Software/Metric | Computes the feasibility of synthesizing a given molecule. | Directly reduces attrition by filtering out non-synthesizable candidates early in the design cycle. |

| Docking Software [20] | Software/Tool | Predicts the preferred orientation and binding affinity of a small molecule to a protein target. | Serves as a key experimental oracle for in silico validation, accurately reflecting activity cliffs. |

AI Architectures in Action: A Deep Dive into Generative Methodologies

The process of drug discovery has long been characterized by its high costs, lengthy timelines, and substantial attrition rates. In recent years, generative artificial intelligence (AI) has emerged as a transformative technology, offering new paradigms for designing therapeutic molecules. Among these approaches, Chemical Language Models (CLMs) represent a particularly innovative methodology that treats molecular structures as sequences, applying advanced natural language processing techniques to the domain of chemistry. This approach frames the challenge of de novo drug design—the creation of novel molecular entities from scratch—as a language modeling problem, where generating a valid and effective drug candidate is analogous to generating a grammatically correct and meaningful sentence [21].

CLMs typically operate on string-based molecular representations, most notably the Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES), which encodes the structure of a molecule using a linear string of characters [21] [22]. By pre-training on large corpora of existing chemical structures, CLMs learn the underlying "grammar" and "syntax" of chemistry, enabling them to generate novel, valid molecular designs. Their integration with reinforcement learning (RL) further enhances their utility, allowing models to be fine-tuned toward generating molecules with specific, desirable properties such as high efficacy, target selectivity, and optimal pharmacokinetic profiles [21] [23]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of CLMs against other prominent de novo design methods, examining their performance, underlying protocols, and practical applications in modern drug discovery.

Performance Comparison of De Novo Drug Design Methods

The following table summarizes the core characteristics and performance metrics of CLMs alongside other established de novo design approaches. This comparison highlights the distinct advantages and trade-offs of each methodology.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of De Novo Drug Design Methods

| Method | Key Principle | Typical Molecular Representation | Relative Training Cost | Sample Efficiency | Notable Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Language Models (CLMs) | Causal language modeling/next-token prediction [21] | SMILES, SELFIES (sequence-based) [22] | Medium (lower when fine-tuning) [21] | High (benefits from pre-training) [21] | High novelty and validity; ideal for goal-directed design via RL [23] |

| Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) | Two networks (generator & discriminator) in competition [21] | Molecular graph, fingerprint (vector-based) | High | Medium | Can produce highly drug-like molecules |

| Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) | Learn latent, compressed representation of input data [21] | Molecular graph, fingerprint (vector-based) | Medium | Medium | Continuous latent space allows for smooth interpolation |

| Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD) | Molecular docking and scoring based on 3D target structure [24] | 3D Atomic coordinates & forces | Very High | Low | Directly incorporates target geometry and interactions |

Quantitative performance benchmarks reveal the practical impact of these methods. For instance, one study demonstrated that a CLM optimized with reinforcement learning could generate molecules with 99.2% achieving high efficacy (pIC50 > 7) against the amyloid precursor protein, while maintaining 100% validity and novelty [21]. Furthermore, CLMs have demonstrated significant efficiency gains in industrial applications. Companies like Exscientia have reported AI-driven design cycles that are approximately 70% faster and require 10 times fewer synthesized compounds than traditional industry norms, underscoring the sample efficiency of these approaches [25].

A critical consideration in evaluating any generative model is the scale of the generated library. Research has shown that using too few generated designs (e.g., 1,000-10,000) can lead to misleading findings when assessing metrics like distributional similarity to a target set. The Fréchet ChemNet Distance (FCD) between generated molecules and a fine-tuning set only stabilizes when more than 10,000 designs are considered, and in some cases, over 1 million are needed for a representative evaluation [22]. This finding is a crucial pitfall in model comparison that all practitioners should note.

Experimental Protocols: How CLMs Are Built and Evaluated

Core Training and Optimization Workflow

The development of a CLM for drug discovery follows a multi-stage process that combines supervised learning with reinforcement learning. The standard protocol can be broken down into the following key steps:

- Pre-training: A base model (e.g., a Generative Pre-trained Transformer (GPT) or Recurrent Neural Network) is trained on a large, diverse corpus of known chemical structures (e.g., from public databases like ChEMBL) in a self-supervised manner. The objective is simple next-token prediction, which teaches the model the fundamental rules of chemical syntax and the distribution of chemical space [22] [23].

- Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT): The pre-trained model is subsequently fine-tuned on a smaller, curated dataset of molecules known to be active against a specific therapeutic target of interest. This adapts the model's output to a more relevant region of chemical space [21].

Reinforcement Learning (RL) Optimization: This is the goal-directed phase. The fine-tuned model is further optimized using RL algorithms, most commonly REINFORCE or its variants [23]. The process is defined as follows:

- Agent: The CLM.

- Action: Selecting the next token in the sequence.

- State: The sequence of tokens generated so far (a partially built molecule).

- Reward: A function that scores a fully generated molecule based on desired properties (e.g., predicted binding affinity, solubility, synthetic accessibility). The REINFORCE algorithm updates the model parameters to maximize the expected reward, following the gradient estimate:

( \nabla J(\theta) = \mathbb{E}{\tau \sim \pi{\theta}} \left[ \sum{t=0}^{T} \nabla{\theta} \log \pi{\theta}(a{t} | s_{t}) \cdot R(\tau) \right] )

where ( \tau ) is a complete trajectory (generated molecule), ( R(\tau) ) is its reward, and ( \pi_{\theta} ) is the policy (CLM) [23].

- Regularization: Techniques like experience replay, hill-climbing (selecting top-k molecules for training), and using baselines to reduce variance in gradient estimates are often employed to stabilize training and improve performance [23].

CLM Reinforcement Learning Optimization Workflow

Benchmarking and Evaluation Metrics

Robust evaluation is critical for comparing CLMs and other generative models. The following metrics are standard in the field:

- Validity: The percentage of generated molecular strings that correspond to a chemically valid molecule. Well-trained CLMs can achieve rates of nearly 100% [21].

- Uniqueness: The fraction of generated molecules that are distinct from one another, assessing the model's diversity and not its tendency to "mode collapse."

- Novelty: The proportion of generated molecules not present in the training set, indicating true de novo design.

- Frèchet ChemNet Distance (FCD): Measures the biological and chemical similarity between the generated set and a reference set (e.g., known active molecules). A lower FCD indicates the generated molecules are more similar to the desired chemical space [22].

- Drug-likeness and Property Predictions: Metrics like Quantitative Estimate of Drug-likeness (QED) or predictions from proprietary models for specific properties (e.g., pIC50 for potency) are used to gauge quality [21] [22].

Table 2: Key Evaluation Metrics for De Novo Design Models

| Metric | Definition | Interpretation | Common Pitfalls |

|---|---|---|---|

| Validity | % of syntactically correct and chemically valid structures [21] | Fundamental measure of model reliability. | High validity does not guarantee usefulness or novelty. |

| Uniqueness | % of non-duplicate molecules in a generated library [22] | Measures diversity of output. Low uniqueness indicates mode collapse. | Highly dependent on the number of designs generated [22]. |

| FCD | Distance between distributions of generated and reference molecules [22] | Lower FCD is better, indicating closer match to reference. | Requires large sample sizes (>10,000) for stable results [22]. |

| Success Rate | % of generated molecules satisfying a complex goal (e.g., pIC50 > 7) [21] | Direct measure of goal-directed optimization performance. | Highly dependent on the accuracy of the reward model. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Implementing and applying CLMs requires a suite of computational tools and chemical resources. The following table details key components of the modern CLM research stack.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CLM-Based Drug Discovery

| Item/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Database | Data | Provides pre-training and fine-tuning data for CLMs. | ChEMBL, PubChem, ZINC [22] |

| Molecular Representation | Language | The "alphabet" and "grammar" for the CLM. | SMILES, DeepSMILES, SELFIES [23] |

| Deep Learning Framework | Software | Enables building, training, and deploying neural network models. | PyTorch, TensorFlow, JAX |

| CLM Architecture | Model | The core neural network that learns and generates sequences. | GPT, LSTM, Structured State-Space Sequence (S4) models [22] |

| Reinforcement Learning Library | Software | Provides algorithms for goal-directed optimization. | REINFORCE is a common choice for CLMs [23] |

| Property Prediction Model | Tool | Serves as the reward function during RL optimization. | Predicts affinity (pIC50), solubility, toxicity, etc. [21] |

| Cheminformatics Toolkit | Software | Handles molecule validation, standardization, and descriptor calculation. | RDKit, OpenBabel |

Chemical Language Models represent a powerful and now established paradigm in de novo drug design, distinguished by their ability to treat molecular generation as a sequence modeling problem. When integrated with reinforcement learning, they demonstrate exceptional capability for goal-directed optimization, producing novel, valid, and potent drug candidates with high efficiency. The experimental data shows that CLMs can achieve remarkable success rates and significantly compress early-stage discovery timelines [21] [25].

However, their effective application requires careful attention to methodological details, particularly concerning the scale of generated libraries for robust evaluation [22] and the choice of RL components for stable training [23]. As the field progresses, the fusion of CLMs with other data modalities, such as large-scale phenotypic screening data and structural biology information, as seen in industry mergers [25], promises to further enhance their predictive power and success rates. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the comparative strengths, operational protocols, and potential pitfalls of CLMs is essential for leveraging their full potential in the ongoing quest to accelerate the delivery of new therapeutics.

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) for Molecular Graph Generation

The field of de novo drug design has been revolutionized by deep generative models, with Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) emerging as a particularly powerful architecture for molecular graph generation. Unlike traditional methods that rely on simplified molecular representations, GNNs operate directly on graph structures where atoms represent nodes and chemical bonds represent edges, naturally preserving the structural information of molecules [26]. This capability is crucial for exploring the vast chemical space to discover novel therapeutic candidates with desired properties. This guide provides a comparative analysis of GNN-based generative frameworks against other computational approaches, examining their performance, experimental protocols, and implementation requirements within the context of modern drug discovery pipelines.

Comparative Performance of Molecular Generation Methods

Quantitative Comparison of Generative Frameworks

The table below summarizes the performance of various molecular generation methods across key metrics relevant to drug design, based on benchmarking studies conducted on the ZINC-250k dataset [27].

| Method Category | Specific Model | Key Metrics | Performance Summary |

|---|---|---|---|

| GNN-Based Generative (Autoregressive) | GraphAF (with advanced GNNs) | DRD2, Median1, Median2 [27] | State-of-the-art results, outperforming 17 non-GNN-based methods [27] |

| GNN-Based Generative (RL-Based) | GCPN (with advanced GNNs) | DRD2, Median1, Median2 [27] | Matches or surpasses non-GNN methods on complex objectives [27] |

| Non-GNN Deep Learning | Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) | Validity, Diversity [28] | Good diversity but can struggle with structural validity [28] |

| Non-GNN Deep Learning | Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) | Validity, Diversity [28] | Moderate performance, often require post-processing for validity [28] |

| Traditional Computational | Genetic Algorithms (GA) | Property Optimization [27] | Effective but computationally expensive, limited exploration [27] |

| Traditional Computational | Bayesian Optimization (BO) | Property Optimization [27] | Sample-efficient but struggles with high-dimensional spaces [27] |

| Diffusion Models | E(3) Equivariant Diffusion Model (EDM) [29] | 3D Structure Stability [29] | High-quality 3D geometry generation; can be combined with GNNs as denoising networks [29] |

Impact of GNN Architecture on Generative Performance

A critical study investigating the expressiveness of GNNs in generative tasks evaluated six different GNN architectures within the GCPN and GraphAF frameworks [27]. The findings reveal two key insights:

- Advanced GNNs Enhance Performance: Replacing the commonly used R-GCN model with more advanced GNNs (e.g., GATv2, GSN, GearNet) led to significant performance improvements in generating molecules with desired properties [27].

- No Direct Correlation with Expressiveness: Counterintuitively, the study found that the theoretical expressiveness of a GNN is not a necessary condition for its success in generative tasks. A more expressive GNN does not guarantee superior generative performance [27].

Beyond Traditional Metrics: The Need for Broader Evaluation

The comparison also highlighted a limitation in standard evaluation practices. Commonly used metrics like Penalized logP and QED (Quantitative Estimate of Drug-likeness) often reach a saturation point and fail to effectively differentiate between modern generative models [27]. This underscores the importance of employing a broader set of objectives, such as DRD2, Median1, and Median2, for a more statistically reliable and meaningful evaluation of a model's capabilities in de novo molecular design [27].

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

To ensure fair and reproducible comparisons, studies in this field typically follow a structured experimental protocol.

Standardized Workflow for Model Evaluation

The following diagram illustrates the common workflow for training and evaluating molecular generative models.

Detailed Methodological Breakdown

- Dataset: The ZINC-250k dataset is a widely adopted benchmark. It contains approximately 250,000 drug-like molecules that are readily synthesizable, providing a diverse and realistic foundation for training and evaluation [27].

- Pre-training: Models are initially trained to learn the general distribution of chemical space by reconstructing molecules or generating valid structures from the ZINC-250k dataset. This phase focuses on fundamental rules of chemistry, such as valency [27] [28].

- Fine-tuning / Optimization: Following pre-training, models are optimized for specific molecular properties. This is often achieved using Reinforcement Learning (RL), where the generative model is an agent that receives rewards for generating molecules with high scores on target properties like drug-likeness (QED) or binding affinity (DRD2) [27].

- Evaluation: The generated molecules are assessed on a suite of metrics. Validity checks if the graph structure corresponds to a real molecule, uniqueness ensures novelty, and diversity measures the coverage of chemical space. Additionally, property-specific scores (e.g., QED, SA (Synthetic Accessibility), and custom objectives like DRD2) are calculated to gauge success in the design task [27] [28].

GNN Frameworks for Molecular Generation

Different GNN-based frameworks approach the generation process with distinct strategies. The following diagram contrasts two primary paradigms: autoregressive and one-shot generation.

- Autoregressive Frameworks (e.g., GCPN, GraphAF): These models construct a molecule sequentially, adding one atom or bond at a time. GCPN (Graph Convolutional Policy Network) formulates this as a Markov decision process reinforced with policy gradients to optimize for desired properties. GraphAF (Flow-based Autoregressive Model) uses an invertible transformation to generate molecules, allowing for efficient probability density estimation [27].

- One-Shot Generation Frameworks (e.g., GraphEBM): These models generate the entire molecular graph in a single step. GraphEBM uses an Energy-Based Model (EBM) to learn the data distribution and can be trained to generate molecules with specific traits in one pass [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation and experimentation in this field rely on a suite of key software tools and datasets, which function as essential "research reagents."

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| ZINC-250k Dataset [27] | Dataset | A benchmark dataset of ~250k drug-like molecules for training and evaluating generative models. |

| PyTorch / TorchDrug [27] | Framework | Deep learning frameworks used for implementing and training GNN models and generative frameworks. |

| RDKit [26] | Cheminformatics Library | A fundamental toolkit for cheminformatics, used to process SMILES strings, handle molecular graphs, and calculate chemical descriptors and properties. |

| TorchDrug [27] | Library | A library built on PyTorch specifically for drug discovery, providing implementations of GCPN, GraphAF, and various GNNs. |

| Open Graph Benchmark (OGB) [30] | Benchmark Suite | Provides standardized datasets and benchmarks to ensure fair and comparable evaluation of graph ML models. |

| GraphSAGE [31] | GNN Algorithm | A specific GNN architecture designed for inductive learning, known for its scalability to large graphs, often used in production systems. |

| Graphormer [30] | GNN Architecture | A graph transformer model that has shown state-of-the-art performance on molecular property prediction tasks. |

GNN-based models for molecular graph generation represent a powerful and versatile paradigm in de novo drug design. Experimental evidence demonstrates that frameworks like GCPN and GraphAF, especially when enhanced with advanced GNNs, can match or surpass traditional and non-GNN deep learning methods across a range of molecular objectives. The field is evolving beyond simple metrics, with a growing emphasis on sophisticated objectives and robust, scalable architectures like graph transformers. While challenges remain—such as the need for better explainability and integration of 3D structural information—GNNs have firmly established themselves as an indispensable tool for accelerating the discovery of novel therapeutic candidates.