Decoding Adaptation: How Comparative Genomics is Revolutionizing Our Fight Against Disease Vectors

This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and drug development professionals on how comparative genomics is transforming the study of disease vector adaptation.

Decoding Adaptation: How Comparative Genomics is Revolutionizing Our Fight Against Disease Vectors

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and drug development professionals on how comparative genomics is transforming the study of disease vector adaptation. We explore the foundational principles of genetic and physical maps, delve into advanced methodologies like whole-genome sequencing and hybrid capture that enable pathogen genome retrieval directly from field samples, and address key challenges in analyzing mixed DNA templates. By highlighting validation through phylogenetic analysis and case studies on ticks and mosquitoes, we demonstrate how genomic insights into immune function, blood-feeding, and co-evolution are directly informing the development of novel diagnostics, targeted therapies, and innovative vector control strategies to mitigate the global burden of vector-borne diseases.

The Genomic Blueprint: Uncovering the Evolutionary Arms Race Between Vectors and Pathogens

Genomic mapping provides the foundational framework for understanding the biology, evolution, and adaptive capabilities of disease vectors. In the context of insects that transmit human pathogens, such as mosquitoes, tsetse flies, and sand flies, deciphering their genomic architecture is crucial for developing targeted control strategies [1] [2]. Genetic maps and physical maps represent two complementary approaches to charting genomes, each with distinct methodologies and applications. While genetic maps depict the relative positions of genes based on recombination frequencies, physical maps provide absolute locations of molecular markers and genes along chromosomes [3]. The integration of these mapping approaches enables researchers to investigate synteny—the conservation of gene order across related species—which reveals evolutionary relationships and genomic changes underpinning vector adaptation and vectorial capacity [3] [4]. With over 20% of all infectious human diseases being vector-borne, causing more than one million deaths annually, advanced genomic studies of these insects have become indispensable tools in global health initiatives [2].

Comparative Analysis of Genetic and Physical Maps

Genetic and physical maps serve as critical tools in vector genomics, each with unique strengths and limitations. The table below summarizes their core characteristics and applications:

| Feature | Genetic Maps | Physical Maps |

|---|---|---|

| Basis of Construction | Recombination rates between markers during meiosis [3] | Physical location of DNA sequences on chromosomes (e.g., via FISH, sequence assembly) [3] |

| Map Units | Centimorgans (cM) [3] | Base pairs (bp), Kilobases (kb), Megabases (Mb) [3] |

| Key Features | - Reveals recombination landscape (e.g., suppressed recombination in centromeres) [3]- Affected by crossover distribution [3] | - Unaffected by recombination variation [3]- Provides absolute physical position [3] |

| Primary Applications | - Trait mapping (QTL analysis) [3]- Comparative mapping (synteny studies) [3]- Breeding program design | - Genome sequence assembly and anchoring [3]- Candidate gene identification- Study of structural variations |

| Limitations | - Resolution limited by recombination frequency and population size [3]- Distance variation due to crossover hot/cold spots [3] | - Requires sophisticated molecular techniques and resources [3]- Does not directly inform on functional genetic linkage |

Experimental Protocols for Map Construction and Synteny Analysis

Protocol 1: Constructing a Genetic Linkage Map

This protocol outlines the key steps for developing a genetic map, a common approach in vector genomics [5] [6].

- Cross Design and Population Development: Create a mapping population from a controlled cross between two genetically distinct vector individuals (e.g., insect strains with different phenotypes). Common designs include F2 intercross or backcross populations [6].

- Genotype Data Collection: Genotype each individual in the mapping population using a high-density molecular marker system. For modern studies, this typically involves:

- Linkage Analysis: Use computational software (e.g., JoinMap, R/qtl) to group markers into linkage groups corresponding to chromosomes, based on their co-segregation patterns.

- Map Ordering and Distance Calculation: Determine the linear order of markers within each linkage group and calculate the genetic distance between them in centimorgans (cM), based on the observed recombination frequencies [3] [6].

Protocol 2: Establishing Synteny and Colinearity

This protocol describes how to identify conserved genomic blocks between different vector species [3] [5].

- Ortholog Identification: Identify orthologous genes (genes in different species that originated from a common ancestor) between the two species being compared. This is typically done using BLAST or similar sequence alignment tools to find highly conserved coding sequences [3] [7].

- Map Alignment: Align the genetic or physical maps of the two species based on the positions of the shared orthologous markers or genes.

- Synteny Block Detection: Identify contiguous chromosomal segments, known as synteny blocks, where the gene order is conserved between the two species. This can be visualized with tools like CMap or Strudel [3] [7].

- Analysis of Rearrangements: Document genomic rearrangements, such as inversions and translocations, which break synteny. These evolutionary events can be inferred when conserved blocks are found on different chromosomes or in a different order [3].

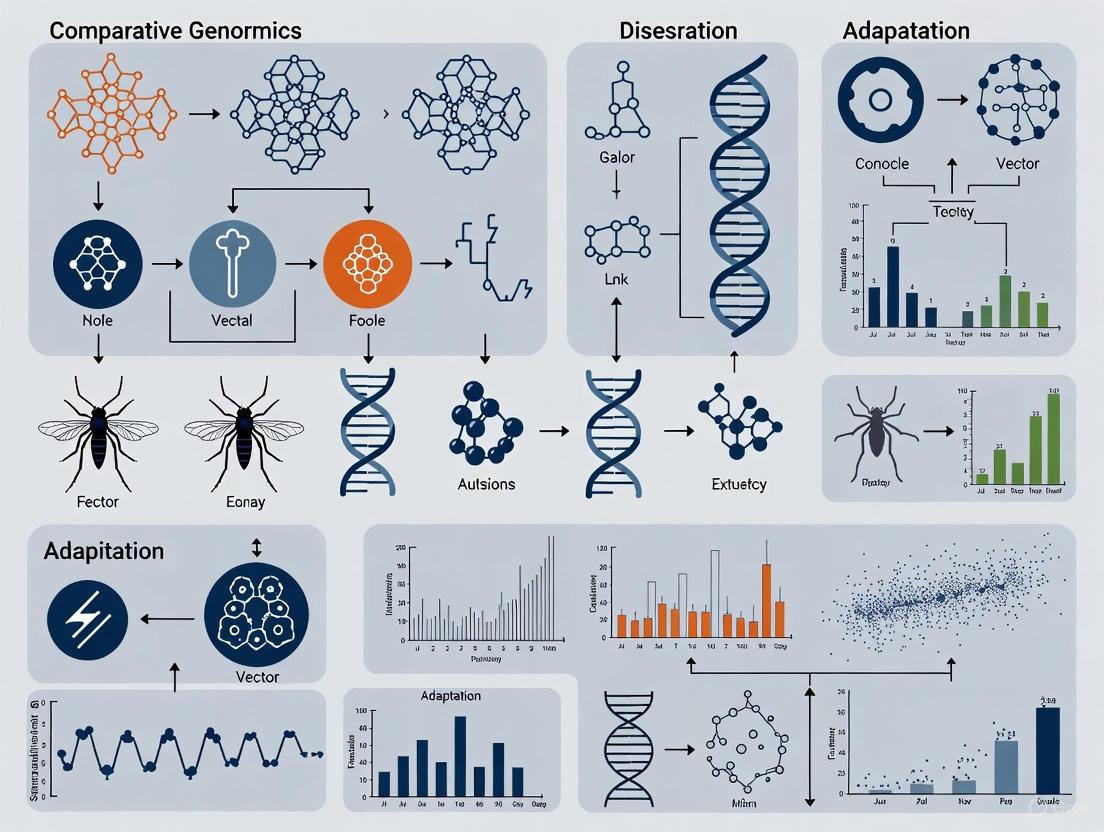

The following diagram illustrates the core logical workflow and relationships in comparative genomics for disease vector research:

Successful genomic research on disease vectors relies on a suite of specialized reagents, databases, and computational tools. The table below details essential resources for mapping and synteny studies:

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Description | Application in Vector Genomics |

|---|---|---|

| BAC (Bacterial Artificial Chromosome) Libraries | Vectors that carry large DNA inserts (100-200 kb) for physical mapping and sequencing [3] [6]. | Used to construct physical maps, sequence complex regions, and bridge gaps in genome assemblies [6]. |

| SNP Genotyping Array | A high-throughput platform for scoring thousands of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms across many individuals [6]. | Genotyping mapping populations for high-density genetic map construction and QTL analysis [5] [6]. |

| BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) | Algorithm for comparing primary biological sequence information against databases [7]. | Identifying orthologous genes and sequences across different vector species for synteny analysis [3] [7]. |

| Strudel | A standalone Java application for the interactive comparison of genetic and physical maps [7]. | Visualizing conserved synteny blocks and genomic rearrangements between multiple vector genomes [7]. |

| VectorBase | A NIAID-supported bioinformatics resource center for invertebrate vectors of human pathogens. | Accessing curated genome assemblies, annotations, and analysis tools for mosquitoes, ticks, and other vectors [2]. |

| CMap (Comparative Map Viewer) | A web-based tool within platforms like GRAMENE for comparing maps from different species [3]. | Aligning linkage maps of different vector species to explore conserved gene orders and evolutionary relationships [3]. |

Research Applications and Impact on Public Health

The integration of genetic and physical maps with synteny analysis has profoundly impacted public health research by illuminating the genomic basis of vectorial capacity—the ability of an insect to transmit a pathogen [1] [2]. For instance, comparative genomics among mosquitoes, tsetse flies, and sand flies has revealed species-specific expansions of chemosensory gene families, which underpin host-seeking behaviors [1]. Similarly, comparing the compact genome of the tsetse fly (Glossina morsitans) to mosquito genomes has uncovered genetic adaptations related to its viviparous reproduction and obligate relationship with bacterial symbionts, which are critical for its competence in transmitting trypanosomes [1] [2]. These insights, derived from map-based studies, help identify potential molecular targets for disrupting vector reproduction or host-pathogen interactions. Furthermore, consensus genetic maps, like the one developed for Citrus species, demonstrate the power of this approach for validating genome assemblies and pinpointing regions with low recombination, which has direct parallels in identifying insect genomic islands under selection from insecticide pressure [5]. As genomic technologies continue to advance, they will further enable researchers to track and trace the evolutionary adaptations of disease vectors in a rapidly changing climate, informing more resilient and targeted disease control strategies [8] [9].

The battle against vector-borne diseases, responsible for over one million human deaths annually, is being transformed by comparative genomics [10]. By decoding the genomes of insects like mosquitoes, tsetse flies, and sand flies, researchers can now identify the precise genomic signatures of natural selection that underpin their adaptation as disease vectors. This evolutionary arms race has equipped these species with specialized traits for hematophagy (blood-feeding), enhanced reproduction, and increased vector competence—the ability to acquire, maintain, and transmit pathogens [1]. The sharp decline in next-generation sequencing (NGS) costs has facilitated the agnostic interrogation of insect vector genomes, giving medical entomologists access to an ever-expanding volume of high-quality genomic and transcriptomic data [10]. This guide objectively compares the genomic features shaping adaptation across major disease vectors, providing researchers with the experimental protocols and analytical frameworks needed to advance this critical field.

Comparative Genomics of Major Disease Vectors

Table 1: Comparative Genomic Features of Major Disease Vectors

| Vector Species | Primary Diseases Transmitted | Genome Size & Features | Key Adaptive Traits | Genomic Evidence of Selection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mosquitoes (Anopheles gambiae, Aedes aegypti) | Malaria, Dengue, Zika, Yellow Fever, Chikungunya [10] | Large, TE-rich genomes; Expanded chemosensory and antiviral gene families [1] | Broad arbovirus transmission capacity; Diverse host-seeking strategies [1] | Rapidly evolving chemosensory repertoires; Adaptive immunity genes [1] [10] |

| Tsetse Flies (Glossina spp.) | African Trypanosomiasis (Sleeping Sickness) [1] | Compact genomes; Viviparous reproduction adaptations; Obligate symbiosis [1] | Lactation and viviparity; Host-seeking specialization; Obligate symbionts aid trypanosome transmission [1] | Specialized reproductive and metabolic genes; Co-evolved symbiont dependencies [1] |

| Sand Flies (Phlebotomus spp.) | Leishmaniasis [1] | Streamlined genomes; Species-specific immune responses [1] | Salivary factors facilitating Leishmania infection [1] | Salivary gland gene families; Immune pathway adaptations [1] |

| Kissing Bugs (Triatoma spp.) | Chagas Disease (Trypanosoma cruzi) [1] | Moderate genome size; Lineage-specific immune adaptations [1] | Moderate fecundity; Specific immune adaptations for T. cruzi transmission [1] | Lineage-specific immune gene families; Detoxification enzymes [1] |

The divergent evolution of these vectors is evident in their genomic architecture. Mosquitoes possess large, transposable element (TE)-rich genomes and expanded antiviral gene families, which support their capacity for broad arbovirus transmission [1]. In contrast, tsetse flies have more compact genomes with genomic adaptations for viviparity (live birth) and an obligate symbiotic relationship with Wigglesworthia bacteria, which provides essential nutrients and influences trypanosome transmission [1]. Sand flies exhibit streamlined genomes and species-specific immune responses that facilitate Leishmania infection, while kissing bugs show moderate fecundity and lineage-specific immune adaptations that enable them to transmit Trypanosoma cruzi across species [1]. These genomic differences directly shape each vector's capacity to transmit disease.

Experimental Protocols for Detecting Selection Signatures

Genome-Wide Scans for Natural Selection

Identifying genomic regions under natural selection requires a multi-faceted approach. Key methodologies include:

- Population Genetic Statistics: Calculating metrics like Tajima's D, FST, and π ratios to detect signatures of selective sweeps and local adaptation.

- Comparative Phylogenomics: Analyzing patterns of sequence conservation and divergence across related species to identify rapidly evolving genes and regulatory elements.

- Functional Validation: Using RNA interference (RNAi) or CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing to knock down candidate genes and assess changes in phenotype, such as pathogen susceptibility or host-seeking behavior [10].

The following workflow outlines a standard pipeline for analyzing vector genomes to identify signatures of natural selection, from sequencing to functional validation.

Transcriptomic Analyses of Vector-Pathogen Interactions

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) provides highly quantitative transcript abundance data, offering a wealth of sequence, isoform, and expression information for the vast majority of encoded genes in a vector species [10]. This approach is particularly powerful for:

- De novo transcriptome assembly: Generating valuable sequence information for molecular evolutionary analyses and quantitative gene expression profiles even in the absence of a high-quality reference genome [10].

- Differential expression analysis: Identifying genes that are upregulated or downregulated in response to pathogen infection, which can reveal key immune and cellular pathways involved in vector competence.

- Single-cell RNA-seq: Enabling the identification of cell-type-specific markers and receptors, which is crucial for targeted vector control strategies [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Vector Genomics

| Reagent / Resource | Primary Function | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerases | Accurate amplification of target sequences | Genome sequencing, PCR-based genotyping, and library construction for NGS. |

| RNAi Reagents | Targeted gene knockdown | Functional validation of candidate genes affecting vector competence or physiology [10]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | Precise genome editing | Knock-out or knock-in mutations to confirm gene function and explore gene drive strategies for vector control [10]. |

| Species-Specific Genome Databases | Reference sequences and annotations | Essential for read alignment, variant calling, and evolutionary analyses. |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Biomolecular interaction analysis | Measuring binding affinity of peptides or antibodies to vector or pathogen targets [11]. |

Data Integration and Interpretation

The relationship between genomic features, adaptive traits, and vectorial capacity is complex. The following diagram illustrates the logical pathway from genetic adaptation to public health impact, highlighting key genomic determinants at each stage.

Interpreting genomic data within an evolutionary framework is paramount. Natural selection leaves distinct signatures on vector genomes. For instance, stabilizing selection accelerates the loss of large-effect alleles contributing to trait variation, while directional selection drives the loss of alleles that move phenotypes away from an optimal value [12]. These evolutionary processes can hamper the accuracy of polygenic scores when predicting ancient phenotypes, underscoring the dynamic nature of vector genomes and the importance of considering selection in analyses [12].

The integration of comparative genomics with evolutionary biology provides an unprecedented lens through which to view the drivers of adaptation in disease vectors. The distinct genomic signatures outlined in this guide—from the expanded immune gene families in mosquitoes to the symbiotic dependencies in tsetse flies—highlight the power of natural selection in shaping vectorial capacity. For researchers and drug development professionals, these insights open new avenues for targeted disease control. The experimental protocols and analytical tools detailed herein provide a roadmap for discovering the next generation of interventions, from novel insecticides to gene drive systems, ultimately contributing to the reduction of the global burden of vector-borne diseases.

Ticks represent a significant global threat to livestock health and human medicine as vectors of numerous pathogens. Comparative genomics of ticks provides crucial insights into the evolutionary adaptations that underpin their parasitic success and capacity for disease transmission. This case study focuses on two species of considerable economic and medical importance: the Asian long-horned tick, Haemaphysalis longicornis, and the southern cattle tick, Rhipicephalus microplus. These species exhibit fundamentally different life history strategies—H. longicornis is a three-host tick with remarkable environmental resilience, while R. microplus is a one-host tick specifically adapted to cattle [13]. Understanding the genetic basis of their immune and metabolic adaptations reveals how arthropod vectors evolve to exploit hosts, transmit pathogens, and survive in diverse ecological niches, with significant implications for developing novel control strategies against tick-borne diseases.

Comparative Genomic Profiles of Target Tick Species

The foundation of comparative genomic analysis begins with understanding the fundamental genetic architecture of the target species. Advanced sequencing technologies have enabled researchers to assemble increasingly complete genomes for both H. longicornis and R. microplus, revealing significant structural differences.

R. microplus possesses one of the largest arthropod genomes sequenced to date, estimated at approximately 7.1 Gbp and consisting of nearly 70% repetitive DNA [14]. A hybrid Pacific Biosciences/Illumina assembly approach generated a draft genome of 2.0 Gbp represented in 195,170 scaffolds, with annotation predicting 24,758 protein-coding genes [14]. In contrast, while a precise genome size for H. longicornis is not provided in the available literature, resequencing efforts of 177 individuals indicate a less complex genomic architecture, though still containing significant structural variation [13] [15].

Table 1: Genomic Characteristics of H. longicornis and R. microplus

| Genomic Feature | H. longicornis | R. microplus |

|---|---|---|

| Genome Size | Information not available in search results | ~7.1 Gbp [14] |

| Repetitive DNA | Information not available in search results | ~70% [14] |

| Assembly Size | Information not available in search results | 2.0 Gbp [14] |

| Protein-Coding Genes | Information not available in search results | 24,758 [14] |

| Scaffolds | Information not available in search results | 195,170 [14] |

| Sample Size (Population Genomics) | 161-177 samples [13] [15] | 138-151 samples [13] [15] |

| Life Cycle Strategy | Three-host tick [13] | One-host tick [13] |

Population genomic analyses of these species reveal contrasting evolutionary patterns. Analysis of 161 H. longicornis and 140 R. microplus genomes demonstrated distinct population structures, with R. microplus exhibiting stronger geographic clustering facilitated by geographical proximity, while H. longicornis shows less population differentiation across mainland China [13]. These differences reflect their distinct host association strategies and ecological plasticity.

Diagram 1: Genomic Analysis Workflow for Comparative Tick Studies. This workflow illustrates the process from sample collection through comparative genomic analysis of H. longicornis and R. microplus, highlighting key differences in population structure and structural variation (SV) profiles.

Immune and Metabolic Gene Adaptations

Genetic Basis of Host-Pathogen Interactions

The evolutionary arms race between ticks, their hosts, and the pathogens they transmit has driven specialized adaptations in immune and metabolic genes. Genomic analyses of R. microplus and H. longicornis have identified specific genes under natural selection that are associated with vector competence and host adaptation.

In R. microplus, significant signals of natural selection were identified in the immune-related gene DUOX and the iron transport gene ACO1, suggesting their importance in the tick's biology and potential role in pathogen defense [13]. The DUOX gene is involved in generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) as part of the innate immune response, while ACO1 (Aconitase 1) plays a crucial role in iron homeostasis, which is particularly relevant for blood-feeding organisms. Iron metabolism in ticks has been identified as potentially having "a role in microbial infection, which is central to host–pathogen interactions" [13].

For H. longicornis, selection was observed in pyridoxal-phosphate-dependent enzyme genes associated with heme synthesis [13]. This adaptation is crucial for managing the toxic effects of heme derived from blood meals and reflects the metabolic challenges of hematophagy. Additionally, significant correlations were identified between the abundance of pathogens, such as Rickettsia and Francisella, and specific tick genotypes, highlighting the role of R. microplus in maintaining these pathogens and its adaptations that influence immune responses and iron metabolism [13].

Structural Variations in Adaptive Evolution

Structural variations (SVs) represent another crucial mechanism of genomic evolution in ticks. A comprehensive analysis of 156 H. longicornis and 138 R. microplus individuals identified 8,370 and 11,537 SVs, respectively [15]. These SVs included deletions (DELs), duplications (DUPs), insertions (INSs), and inversions (INVs), with DUPs exhibiting longer median lengths in R. microplus compared to H. longicornis.

Notably, researchers identified a 5.2-kb deletion in the cathepsin D gene in R. microplus and a 4.1-kb duplication in the CyPJ gene in H. longicornis, both likely associated with vector-pathogen adaptation [15]. Cathepsin D is a protease involved in blood meal digestion, and its structural variation may reflect adaptation to specific host proteins or pathogen transmission mechanisms. The CyPJ gene duplication in H. longicornis may enhance this species' ability to process diverse blood meals from multiple hosts throughout its life cycle.

Table 2: Key Adaptive Genes and Structural Variations in Tick Species

| Adaptation Type | H. longicornis | R. microplus |

|---|---|---|

| Immune Genes | Selection in pyridoxal-phosphate-dependent enzyme genes [13] | DUOX (immune response) under selection [13] |

| Metabolic Genes | Associated with heme synthesis [13] | ACO1 (iron transport) under selection [13] |

| Key Structural Variations | 4.1-kb duplication in CyPJ gene [15] | 5.2-kb deletion in cathepsin D gene [15] |

| Pathogen Associations | Carries 30+ human pathogens [16] | Specific genotypes correlate with Rickettsia and Francisella [13] |

| Host Range | Generalist (wide host range) [13] | Specialist (cattle-specific) [13] |

Experimental Protocols for Genomic Analysis

Genome Sequencing and Assembly Methodologies

Advanced genomic analysis of ticks requires sophisticated sequencing and assembly approaches to overcome challenges posed by their large, repetitive genomes. The R. microplus genome project employed a hybrid sequencing strategy combining Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) long-read sequencing with Illumina short-read sequencing to capture both the unique and highly repetitive fractions of the genome [14].

Sample Preparation: Genomic DNA was extracted from pooled collections of eggs from the Deutsch strain of R. microplus. Very high molecular weight genomic DNA was purified using reassociation kinetics (Cot) protocols to select for the unique low-copy genome fraction [14].

Sequencing Protocols: PacBio sequencing generated long reads averaging 5.7 kb in length, providing crucial spanning across repetitive regions. These were complemented by Illumina sequencing of Cot-selected DNA, which provided high-accuracy short reads for error correction [14].

Assembly Pipeline: The assembly process utilized customized approaches optimized for Cloud-based computational resources. Error correction of PacBio reads was performed using the assembled set of Illumina-generated contigs. This hybrid approach produced an assembly of 2.0 Gbp in 195,170 scaffolds with an N50 of 60,284 bp, significantly improving representation of the repetitive genome fractions compared to earlier attempts [14].

Population Genomic Analysis of Structural Variation

Analysis of structural variation across tick populations provides insights into evolutionary adaptations. Recent research performed whole-genome sequencing of 328 tick samples (177 H. longicornis and 151 R. microplus) with a mean read coverage of approximately 8X [15].

Variant Discovery: A comprehensive SV discovery pipeline combined multiple detection algorithms (Manta, Lumpy, and SVseq2) to reduce false positives. The discovered SVs were then genotyped at the population level using svimmer and graphtyper2 [15].

Quality Control: After initial SV calling, researchers applied stringent filtering criteria, removing individuals with significantly decreased SV counts and outliers identified through principal component analysis. This resulted in high-quality SV maps for 156 H. longicornis and 138 R. microplus individuals [15].

Functional Annotation: SVs were annotated relative to gene features and regulatory regions to identify potentially functional variants. Highly differentiated SVs between populations were prioritized for further analysis of their potential roles in local adaptation, particularly focusing on genes associated with blood digestion, immune defense, and pathogen transmission [15].

Metabolic Pathway Adaptations for Hematophagy

The evolutionary transition to hematophagy required extensive metabolic adaptations in ticks. Both H. longicornis and R. microplus have developed specialized pathways to handle the unique challenges of blood feeding, though with species-specific variations reflecting their distinct life history strategies.

Blood digestion generates large amounts of heme, which is toxic at high concentrations. H. longicornis exhibits selection in pyridoxal-phosphate-dependent enzyme genes associated with heme synthesis and degradation [13]. This adaptation likely helps manage heme toxicity across its three-host life cycle, where the tick must process blood meals from potentially different host species at each life stage.

R. microplus, as a one-host tick, has evolved specialized iron metabolism pathways, evidenced by selection signals in the ACO1 (Aconitase 1) gene [13]. Iron transport and storage are crucial for this species, which remains on a single bovine host throughout its parasitic life stages and must efficiently process large volumes of iron-rich blood while avoiding iron-mediated oxidative stress.

Transcriptomic analyses reveal that R. microplus demonstrates different gene expression patterns when feeding on tick-resistant versus susceptible cattle breeds [17]. Among 13,601 examined transcripts, researchers identified 297 highly expressed transcripts that were significantly differentially expressed in ticks feeding on resistant cattle (Bos indicus) compared to susceptible cattle (Bos taurus) [17]. These included genes encoding enzymes involved in primary metabolism, stress response, defense mechanisms, and cuticle formation, highlighting the metabolic plasticity required to overcome host defenses.

Diagram 2: Metabolic and Immune Adaptations to Hematophagy. This diagram contrasts the key metabolic and immune adaptations in H. longicornis and R. microplus that enable their parasitic lifestyles and influence pathogen transmission capabilities.

Cutting-edge research in tick genomics requires specialized reagents, databases, and analytical tools. The following table summarizes key resources that enable comprehensive study of immune and metabolic gene evolution in ticks.

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Tick Genomics

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Application in Tick Research |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic Databases | CattleTickBase [14], BmiGI Version 2 [18] | Access to curated genomic and transcriptomic data for R. microplus |

| Sequencing Technologies | PacBio Long-Read Sequencing, Illumina Short-Read Sequencing [14] | Hybrid genome assembly to overcome repetitive regions |

| Bioinformatic Tools | BWA (alignment) [13], GATK (variant calling) [13], Manta/Lumpy/SVseq2 (SV detection) [15] | Genome alignment, SNP calling, and structural variation detection |

| Population Genomic Software | VCFtools [16], IQ-TREE (phylogenetics) [16], STRUCTURE [13] | Population structure analysis and evolutionary inference |

| Tick Colonies | Laboratory-maintained colonies (e.g., Deutsch strain of R. microplus [14]) | Controlled experiments on tick biology and vector-pathogen interactions |

| Pathogen Detection Assays | Meta-transcriptomic sequencing [16], PCR-based pathogen screening | Characterization of tick microbiomes and pathogen presence |

| Gene Expression Analysis | RNA sequencing [19], Multidimensional Protein Identification Technology (MudPIT) [19] | Transcriptomic and proteomic profiling of tick tissues |

Comparative genomic analysis of H. longicornis and R. microplus reveals how evolutionary forces have shaped distinct immune and metabolic adaptations in these economically significant disease vectors. The findings from these studies highlight several important directions for future research and tick control development.

First, the species-specific genetic adaptations—such as the selection in DUOX and ACO1 genes in R. microplus and pyridoxal-phosphate-dependent enzymes in H. longicornis—provide promising targets for novel tick control strategies [13]. These could include vaccines designed to disrupt critical metabolic processes or small molecule inhibitors that target species-specific pathways.

Second, the documented structural variations, particularly the 5.2-kb deletion in the cathepsin D gene in R. microplus and the 4.1-kb duplication in the CyPJ gene in H. longicornis, offer insights into mechanisms of rapid adaptation to environmental pressures [15]. Monitoring these variations across geographic populations could serve as early warning systems for emerging acaricide resistance or changes in vector competence.

Finally, the contrasting genetic architectures between these species—with R. microplus exhibiting stronger geographic structure while H. longicornis shows remarkable genetic homogeneity across diverse environments—provides a natural experiment for understanding how life history traits shape genomic evolution [13]. This knowledge enhances our fundamental understanding of arthropod evolution while providing practical insights for developing targeted vector control strategies that account for species-specific biological differences.

The integration of genomic tools with ecological studies represents the future of tick research, enabling the development of precision control methods that are both effective and environmentally sustainable. As climate change and global trade continue to alter tick distributions and pathogen transmission dynamics, these genomic resources will become increasingly valuable for protecting animal and human health from tick-borne diseases.

The intricate dance of host-pathogen co-evolution represents one of the most dynamic processes in evolutionary biology, where genetic changes in one species drive adaptive changes in the other. In disease systems involving arthropod vectors and their microbial pathogens, this co-evolutionary arms race has profound implications for global public health. Vectors such as mosquitoes, ticks, and kissing bugs have developed sophisticated genomic adaptations that influence their capacity to transmit pathogens, while pathogens have concurrently evolved counter-strategies to exploit vector biology. Understanding these reciprocal genomic signatures is crucial for developing novel control strategies against vector-borne diseases, which collectively account for substantial global morbidity and mortality. This review synthesizes recent advances in comparative genomics that reveal how vectors and microbes genetically shape each other, highlighting key experimental approaches and findings that are reshaping our understanding of these complex biological relationships.

The genomic conflict between vectors and pathogens operates across multiple fronts, encompassing immune evasion, nutritional adaptation, and reproductive strategies. For instance, ticks have evolved complex salivary proteins that modulate host defenses, creating favorable environments for pathogen establishment [13]. Simultaneously, pathogens like Rickettsia species have developed mechanisms to manipulate the tick's antioxidant systems, thereby evading vector immune responses [13]. Similarly, in mosquito populations, the process of self-domestication and adaptation to human environments has been accompanied by genomic changes that enhance their vectorial capacity for arboviruses [20]. These co-evolutionary dynamics occur across varying temporal scales, from rapid adaptations in recently invasive populations to ancient genetic conflicts reflected in endogenous viral elements maintained across millennia [20].

Molecular Mechanisms of Vector-Pathogen Adaptation

Genomic Adaptations in Disease Vectors

Disease vectors exhibit remarkable genomic specialization that reflects their long-standing relationships with pathogens. Comparative genomics reveals significant divergence in key gene families across major vector species, including mosquitoes, tsetse flies, and sand flies [1]. These differences in chemosensory gene repertoires, immune pathways, and symbiotic associations fundamentally shape vector competence and host-seeking behaviors.

Table 1: Genomic Features of Major Disease Vector Species

| Vector Species | Genome Size Characteristics | Key Adaptive Features | Primary Pathogens |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mosquitoes (Aedes aegypti) | Large, TE-rich genomes | Expanded antiviral gene families, chemosensory gene expansions | Dengue, Zika, Chikungunya, Yellow Fever viruses |

| Tsetse flies (Glossina spp.) | Compact genomes | Viviparous reproduction adaptations, obligate symbiosis with Wigglesworthia | Trypanosomes (Sleeping sickness) |

| Sand flies (Phlebotomus spp.) | Streamlined genomes | Species-specific immune responses, salivary factors | Leishmania parasites |

| Kissing bugs (Triatoma spp.) | Moderate-sized genomes | Lineage-specific immune adaptations, redox homeostasis | Trypanosoma cruzi (Chagas disease) |

The domestication process in Aedes aegypti mosquitoes provides a compelling example of how behavioral adaptation drives genomic divergence. The domestic Aedes aegypti aegypti (Aaa) ecotype exhibits significant genetic differentiation from its wild ancestor Aedes aegypti formosus (Aaf), with 186 genes identified as "Aaa molecular signatures" [20]. These signatures arose primarily from standing genetic variation in African populations and were co-opted for self-domestication through genomic and functional redundancy. The adaptive shift involved fine regulation of chemosensory, neuronal, and metabolic functions, parallel to domestication processes observed in mammals like rabbits and silkworms [20]. This domestication genomic landscape has direct implications for vectorial capacity, as Aaa mosquitoes demonstrate higher competence for arbovirus transmission compared to their wild counterparts.

Pathogen Counter-Adaptation Strategies

Pathogens have evolved sophisticated mechanisms to overcome vector defenses and enhance their transmission potential. The cry toxin produced by Bacillus thuringiensis tenebrionis (Btt) exemplifies how pathogen virulence factors evolve in response to host immune pressures. When experimentally evolved in immune-primed red flour beetles, Btt pathogens showed no change in average virulence but exhibited a notable increase in virulence variability among independent lines [21]. Genomic analysis revealed that this increased variability was associated with heightened activity of mobile genetic elements, particularly prophages and plasmids. The expression of Cry toxin was linked to evolved differences in copy number variation of the cry-carrying plasmid, demonstrating how pathogen genome plasticity facilitates adaptation to host immune pressures [21].

Arboviruses like chikungunya virus (CHIKV) demonstrate similar adaptive capacity through targeted mutations that enhance vector compatibility. During the 2025 Foshan outbreak in China, mosquito-derived CHIKV strains contained adaptive mutations E1-A226V and E2-L210Q in the envelope proteins that significantly increase viral adaptability to Aedes albopocytus mosquitoes [22]. These sequential adaptations enhance midgut infection and dissemination in mosquitoes without compromising fitness, enabling the virus to exploit Ae. albopictus as a more efficient urban vector across wider geographic ranges [22]. The appearance of these mutations in outbreak settings highlights the real-time evolutionary arms race between vectors and pathogens.

Experimental Evolution: Direct Observation of Co-evolution

Experimental evolution approaches provide controlled systems to directly observe host-pathogen co-evolutionary dynamics. In the Tribolium castaneum-Bacillus thuringiensis model, pathogens evolved through eight selection cycles in immune-primed versus non-primed hosts revealed that innate immune memory drives increased variance in pathogen virulence without necessarily altering mean virulence [21]. This finding challenges traditional assumptions about directional selection on virulence and highlights how host immune pressures can maintain pathogen diversity rather than driving uniform adaptation.

The experimental protocol for such studies typically involves:

- Host priming: Initial exposure of hosts to non-lethal pathogen doses to activate immune memory

- Selection cycles: Sequential passages of pathogens through primed or control host groups

- Virulence assessment: Measurement of host mortality rates and pathogen loads

- Genomic sequencing: Whole genome analysis of evolved pathogen lines to identify genetic changes

- Mobile element activity: Special attention to prophages, plasmids, and transposons as hotspots of rapid adaptation [21]

These experimental evolution studies demonstrate that innate immune memory, previously considered a simpler form of immunity compared to vertebrate adaptive immunity, exerts substantial selective pressure on pathogens. This has important implications for applications of immune priming in pest control and public health, as even primitive forms of immune memory can shape pathogen evolution in unexpected ways [21].

Genomic Methodologies for Studying Co-evolution

Genome-to-Genome Analysis

The genome-to-genome (g2g) approach represents a powerful methodology for identifying specific genetic interactions between hosts and pathogens. This method involves systematic testing for statistical associations between genetic variants in both organisms, revealing how particular host alleles predispose to infection with specific pathogen strains [23]. In a landmark study of tuberculosis, researchers conducted paired analysis of human and Mycobacterium tuberculosis genomes from 1556 patients, performing over 850 million regression models between host and pathogen variants [23]. This approach identified a significant association between a human intronic variant (rs3130660) in the FLOT1 gene and a specific subclade of Mtb Lineage 2, with individuals carrying the rs3130660-A allele having ten times higher likelihood of infection with the interacting bacterial strain [23].

Table 2: Key Analytical Methods in Vector-Pathogen Co-evolution Research

| Methodology | Key Principle | Application Example | Technical Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome-to-Genome (g2g) Analysis | Statistical association between host and pathogen variants | Identifying human FLOT1 variant associated with Mtb subclade [23] | Paired host-pathogen genomic data, high-performance computing |

| Landscape Genomics | Correlation of genetic variation with environmental factors | Identifying local adaptation in California Ae. aegypti populations [24] | Whole-genome sequencing, environmental data layers |

| Experimental Evolution | Direct observation of evolution in controlled conditions | Bacillus thuringiensis evolution in immune-primed beetles [21] | Laboratory host-pathogen system, sequential passage |

| Phylogenomic Dating | Molecular dating of divergence events | Reconstructing Ae. aegypti global dispersal history [25] | Time-calibrated phylogenetic trees, molecular clock models |

The g2g methodology involves several critical steps:

- Paired sequencing: Generation of whole-genome data for both host and pathogen from the same infection

- Variant calling: Identification of high-quality SNPs in both genomes

- Association testing: Systematic testing of all host-pathogen variant pairs using mixed effects models

- Covariate adjustment: Controlling for population structure, relatedness, and demographic factors

- Functional validation: Linking associated variants to molecular phenotypes through eQTL analysis and experimental assays [23]

This approach revealed that the associated human variant acts as an eQTL for FLOT1 expression in lung tissue, and the interacting Mtb strains exhibited altered redox states due to a thioredoxin reductase mutation, illustrating the molecular interface of this genetically matched interaction [23].

Landscape Genomics of Vector Adaptation

Landscape genomics provides a powerful framework for understanding how environmental heterogeneity drives local adaptation in disease vectors. This approach integrates whole-genome sequencing with environmental data to identify loci under selection in specific ecological conditions. A study of recently invasive Ae. aegypti populations in California employed landscape genomics to investigate rapid adaptation to heterogeneous environments [24]. Researchers sequenced 96 mosquitoes from 12 geographic districts and analyzed associations with 25 topo-climate variables, identifying 112 genes showing strong signals of local environmental adaptation [24].

The analytical workflow for landscape genomics typically includes:

- Variant discovery: Whole-genome sequencing of vector populations across environmental gradients

- Environmental data collection: Compilation of climate, land use, and other ecological variables

- Population structure analysis: Accounting for neutral genetic structure using PCA and admixture analysis

- Genotype-environment association: Using methods like BayPass and LFMM to detect outlier loci

- Functional annotation: Linking adaptive loci to biological processes and pathways [24]

This approach identified selection signals in heat-shock proteins and other stress-response genes, illustrating how invasive populations rapidly adapt to novel climatic conditions [24]. These findings have practical implications for predicting vector expansion under climate change scenarios and designing targeted vector control strategies.

Insect-Specific Viruses as Evolutionary Proxies

Insect-specific viruses (ISVs) represent promising tools for reconstructing vector evolutionary history and dispersal patterns. These viruses maintain long-term associations with their insect hosts and experience lower selective pressure compared to arboviruses, resulting in more stable evolutionary rates [25]. Studies of ISVs including Phasivirus phasiense (PCLV), cell-fusing agent virus (CFAV), and Aedes anphevirus (AeAV) in global Ae. aegypti populations have provided insights into the vector's historical dispersal routes [25].

The application of ISVs in evolutionary studies involves:

- Viral genome sequencing: From vector populations across different geographic regions

- Phylogenetic analysis: Reconstruction of evolutionary relationships among viral strains

- Recombination detection: Identification of recombination events that complicate evolutionary analysis

- Divergence time estimation: Molecular dating of viral lineage splits to infer vector dispersal history [25]

Analysis of ISVs in Ae. aegypti has revealed genetically structured diversity patterns associated with geography, provided evidence for multiple introductions into the Americas between the 17th and 19th centuries, and documented recent dispersal into Oceania [25]. The varying evolutionary dynamics of different ISVs (e.g., recombination frequency, mutation rates) make them complementary tools for studying vector evolution across different temporal scales.

Signaling Pathways in Vector-Pathogen Interactions

The co-evolutionary arms race between vectors and pathogens operates through several key molecular pathways that mediate immune recognition, nutritional competition, and cellular invasion. The following diagrams illustrate central signaling pathways involved in these interactions.

Diagram 1: Key Signaling Pathways in Vector-Pathogen Interactions. This diagram illustrates three core pathways mediating co-evolutionary dynamics: immune recognition, nutritional competition, and cellular invasion. The FLOT1-mediated phagosome maturation pathway represents a documented example of host-pathogen genetic interaction identified through genome-to-genome analysis [23].

The immune recognition pathway begins with vector pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) detecting pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), triggering conserved immune signaling cascades including IMD, Toll, and JAK/STAT pathways [13]. These signals ultimately induce effector genes such as antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) that determine pathogen clearance or persistence. The nutritional immunity pathway centers on competition for essential nutrients like iron, with vectors employing limitation strategies and pathogens countering with siderophores and acquisition systems [13]. The cellular invasion pathway highlights how pathogens exploit vector receptors for entry, with subsequent intracellular survival dependent on manipulating vesicle trafficking and phagosome maturation processes, including FLOT1-mediated mechanisms [23].

Research Reagent Solutions for Co-evolution Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Vector-Pathogen Co-evolution Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina NovaSeq 6000, PacBio HiFi | Whole genome sequencing of vectors and pathogens | High coverage, variant detection, structural variant analysis |

| Bioinformatic Tools | BWA-MEM, GATK, Freebayes, Trinity | Variant calling, genome assembly, phylogenetic analysis | Handling of repetitive regions, mobile elements, and complex polymorphisms |

| Vector Sampling | BG-Sentinel traps, CO₂ baiting | Field collection of vector populations | Standardized sampling across geographical gradients |

| Pathogen Detection | Multiplex qPCR (e.g., Vcheck M Canine Vector 8 Panel), RT-qPCR | Screening for pathogen infections and co-infections | High sensitivity for low parasitemia, capacity for co-infection detection |

| RNA Analysis | TRI Reagent, Ribo-Zero rRNA depletion kits | Transcriptomic studies of vector responses and pathogen gene expression | Preservation of RNA integrity, removal of host ribosomal RNA |

| Functional Validation | RNAi, CRISPR-Cas9 systems | Gene knockout and knockdown studies in vectors | Confirmation of gene function in immune responses and vector competence |

The research reagents listed in Table 3 represent essential tools for investigating vector-pathogen co-evolution. The Vcheck M Canine Vector 8 Panel, for instance, is a multiplex real-time PCR test capable of detecting co-infections with up to eight vector-borne pathogens, providing valuable data on pathogen prevalence and interactions in field-collected samples [26]. Similarly, BG-Sentinel traps have been widely used for standardized collection of Ae. aegypti mosquitoes across different geographical regions, enabling comparative studies of population genomics and local adaptation [24]. For genomic studies, the AaegL5 reference genome has served as the foundation for population genomic analyses of Ae. aegypti, facilitating the identification of adaptive loci and signatures of selection [20] [24].

The study of host-pathogen co-evolution between disease vectors and microbes has entered a transformative era with the advent of comparative genomics approaches. Research has revealed that far from being static relationships, these biological interactions represent dynamic genetic conflicts characterized by reciprocal adaptation and counter-adaptation. Key insights include the role of vector immune pressures in driving pathogen virulence variation, the identification of specific host-pathogen genetic variant interactions through genome-to-genome analysis, and the documentation of rapid local adaptation in invasive vector populations.

Future research directions will likely focus on integrating multi-omics approaches (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics) to obtain system-level understanding of vector-pathogen interactions. The expanding application of gene drive technologies for vector control makes understanding co-evolutionary dynamics increasingly urgent, as genetic interventions may themselves become selection pressures that shape future evolution. Additionally, the growing availability of genomic resources for diverse vector species will enable more comprehensive comparative analyses to identify conserved and lineage-specific adaptation mechanisms. As climate change and globalization continue to alter the distribution of vector-borne diseases, understanding the genetic underpinnings of vector-pathogen co-evolution will be crucial for developing sustainable strategies to mitigate their impact on human and animal health.

From Sequence to Solution: Cutting-Edge Tools and Applications in Vector Genomics

The study of pathogen genomics within their disease vectors—such as ticks, mosquitoes, and other arthropods—presents a unique set of challenges for researchers. A central obstacle is the significant disparity between pathogen and host DNA, where the target pathogen genomic material is often vastly outnumbered by the vector's own DNA. This "host-DNA hurdle" can obscure pathogen detection, reduce sequencing efficiency, and compromise the quality of assembled genomes, ultimately impeding our understanding of vector-pathogen adaptation and coevolution. The field of comparative genomics for disease vector adaptation research relies heavily on obtaining high-quality genomic data from pathogens directly within their vectors to uncover the molecular mechanisms driving evolution and transmission [13] [2].

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies have revolutionized our ability to study vector-borne diseases, enabling agnostic interrogation of vector genomes and transcriptomes [2]. However, without targeted enrichment, metagenomic sequencing of vector samples yields predominantly vector-derived sequences, making pathogen genome assembly inefficient and often incomplete. To address this limitation, two principal target enrichment methodologies have emerged: amplicon sequencing and hybridization capture [27]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these approaches, with a specific focus on how hybrid capture techniques are overcoming the host-DNA barrier to advance our understanding of pathogen genomics in vector-borne disease research.

Target Enrichment Methodologies: Principles and Workflows

Hybrid Capture-Based Enrichment

The hybrid capture method enriches genomic regions of interest (ROIs) using sequence-specific, single-stranded oligonucleotide "baits" or "probes" that hybridize to target sequences [27]. These probes, which can be DNA or RNA, are typically biotinylated to enable retrieval using streptavidin-coated magnetic beads after hybridization [27] [28]. The fundamental workflow involves several key steps: first, the input DNA is fragmented through enzymatic or mechanical methods; next, sequencing adapters are ligated to create a library; this library is then denatured and hybridized with the biotin-labeled capture probes; the probe-bound targets are isolated using magnetic pulldown; and finally, the enriched library is amplified via PCR before sequencing [27] [28].

A significant innovation in this field is the development of simplified hybrid capture workflows that eliminate traditional complexities. Methods like the "Trinity" approach remove bead-based capture steps, multiple washes, and post-hybridization PCR by directly loading hybridization products onto functionalized streptavidin flow cells [29]. This streamlined process reduces the total workflow time by over 50% while maintaining or improving capture specificity and library complexity [29].

Amplicon-Based Enrichment

In contrast to hybrid capture, amplicon-based enrichment utilizes polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to amplify genomic regions of interest with primers flanking the target areas [27]. Through multiplex PCR, hundreds to thousands of primers work simultaneously to amplify all target regions, creating amplicons that are then converted into sequencing libraries by adding barcodes and platform-specific adapters [27] [30]. Several variations of this method have been developed, including long-range PCR, droplet PCR, microfluidics-based approaches, and anchored multiplex PCR, each offering specific advantages for particular applications [27].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental procedural differences between these two enrichment approaches:

Comparative Performance Analysis in Pathogen Research

Technical Comparison of Key Parameters

The selection between hybrid capture and amplicon sequencing involves trade-offs across multiple technical parameters that directly impact research outcomes in vector-pathogen studies. The following table summarizes these key differences based on current methodological capabilities:

| Feature | Hybrid Capture | Amplicon Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Targets | Virtually unlimited panel size [31] | Flexible, usually <10,000 amplicons [31] |

| Input DNA Requirement | 1-250 ng for library prep; 500 ng into capture [30] | 10-100 ng [30] |

| Workflow Steps | More steps and hands-on time [31] [28] | Fewer steps, more streamlined [31] |

| Total Time | More time required (12-24 hours traditional; 5+ hours simplified) [29] [28] | Less time required [31] |

| Cost per Sample | Higher cost [31] | Generally lower cost per sample [31] |

| Variant Detection Range | Comprehensive for all variant types (SNPs, indels, CNVs, fusions) [28] | Ideal for SNVs and small indels [28] |

| On-Target Rate | High but requires optimization [31] | Naturally higher due to primer specificity [31] |

| Uniformity of Coverage | Greater uniformity across targets [31] | Variable due to PCR bias [27] |

| Sensitivity | <1% variant frequency [30] | <5% variant frequency [30] |

Application-Specific Performance in Vector-Pathogen Studies

Recent comparative studies demonstrate how these technical differences translate into practical performance variations in pathogen genomics research. A 2025 diagnostic comparison of sequencing methods for lower respiratory infections found that capture-based tNGS identified 71 pathogen species, outperforming amplification-based tNGS (65 species) and showing significantly higher accuracy (93.17%) and sensitivity (99.43%) when benchmarked against comprehensive clinical diagnosis [32].

For studying coevolution between vectors and pathogens, hybrid capture offers distinct advantages in detecting novel variants and structural variations. Research on tick-pathogen adaptation revealed that hybrid capture approaches enabled identification of selection signatures in immune-related genes like DUOX and iron transport gene ACO1 in R. microplus ticks, providing insights into the genomic mechanisms of vector-pathogen coevolution [13]. The ability to profile all variant types comprehensively makes hybrid capture particularly valuable for discovering novel adaptations in vector and pathogen genomes [28].

In genomic surveillance during outbreaks, hybrid capture has proven invaluable. During the 2025 chikungunya outbreak in Foshan, China, hybrid capture methods enabled the first whole-genome sequencing of mosquito-derived CHIKV strains, revealing critical adaptive mutations (E1-A226V and E2-L210Q) that enhanced viral adaptability to Ae. albopictus vectors [22]. This capacity to generate complete pathogen genomes from complex vector samples underscores hybrid capture's utility in tracking evolutionary adaptations in near real-time.

Experimental Protocols for Vector-Pathogen Studies

Simplified Hybrid Capture Protocol for Pathogen Enrichment

The following protocol adapts the simplified hybrid capture approach for pathogen genome enrichment from vector samples, based on methodologies successfully used in recent studies [29]:

Sample Preparation and Library Construction

- Vector Sample Processing: Homogenize vector specimens (e.g., tick, mosquito) using motor-driven tissue grinders in DMEM supplemented with 2% FBS. Centrifuge at 8000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C and collect supernatant [22].

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Extract total nucleic acids using viral RNA/DNA kits. For integrated pathogen detection, include DNase treatment for RNA sequencing and RNase treatment for DNA sequencing [32].

- Library Preparation: Fragment DNA via enzymatic treatment or mechanical shearing. Prepare sequencing libraries using platform-specific kits (e.g., IDT xGen Exome Sequencing Kit Trinity, Twist for Element Exome 2.0, or Roche KAPA EvoPrep). For PCR-free workflows, use enzymatic library prep kits to maintain library complexity [29].

Hybridization and Capture

- Hybridization Reaction: Pool libraries (3-24 μg total input) and combine with biotinylated probes targeting pathogen genomes. Include Human Cot DNA and binding reagent. Hybridize for 1-16 hours depending on protocol specificity requirements [29].

- Streamlined Capture: For simplified workflows, directly load hybridization product onto streptavidin-functionalized flow cells, eliminating bead-based capture and multiple wash steps. For traditional approaches, use magnetic streptavidin bead pulldown followed by temperature-controlled washes [29].

Amplification and Sequencing

- Library Amplification: For traditional protocols, amplify captured DNA using 8-12 cycles of PCR with platform-compatible primers. For streamlined approaches, proceed directly to on-flow cell amplification [29].

- Sequencing: Sequence on Illumina, Element AVITI, or comparable platforms. For comprehensive pathogen detection, aim for 0.1-20 million reads per sample depending on panel size [29] [32].

Amplicon Sequencing Protocol for Targeted Pathogen Detection

Primer Design and Validation

- Multiplex Primer Panel Design: Design primers flanking target regions in pathogen genomes. For comprehensive detection of diverse pathogens, use 198+ pathogen-specific primers spanning bacteria, viruses, fungi, mycoplasma, and chlamydia [32].

- Primer Validation: Test primer specificity and amplification efficiency against reference strains. Optimize primer concentrations to ensure uniform coverage across targets [27].

Library Preparation and Sequencing

- Target Amplification: Perform ultra-multiplex PCR amplification using pathogen-specific primers. Conduct two rounds of PCR amplification to enrich target pathogen sequences [32].

- Library Construction: Purify PCR products using bead-based cleanup. Amplify with primers containing sequencing adapters and sample barcodes [30].

- Quality Control and Sequencing: Assess library quality using fragment analyzers and fluorometers. Sequence on appropriate platforms (e.g., Illumina MiniSeq) with 100 bp single-end reads, targeting approximately 0.1 million reads per library [32].

Research Reagent Solutions for Pathogen Enrichment

Successful implementation of hybrid capture for pathogen genome enrichment requires specific research reagents and materials. The following table outlines essential solutions for establishing these workflows in vector-pathogen studies:

| Research Reagent | Function | Example Products |

|---|---|---|

| Biotinylated Probe Panels | Target-specific enrichment of pathogen sequences | IDT xGen Pan-Cancer Panel, Twist Pan-Viral Panel, GMS Myeloid Panel |

| Library Preparation Kits | Fragmentation, adapter ligation, and library amplification | IDT xGen Exome Sequencing Kit, Roche KAPA EvoPrep, Element Elevate Enzymatic Library Prep Kits |

| Hybridization Reagents | Facilitate specific probe-target hybridization | xGen Hybridization Buffer, Trinity Binding Reagent, Human Cot DNA |

| Capture Beads/Flow Cells | Immobilization and separation of target-probe complexes | Streptavidin magnetic beads, Streptavidin-functionalized flow cells (Element Biosciences) |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Isolation of pathogen nucleic acids from vector samples | QIAamp UCP Pathogen DNA Kit, MagPure Pathogen DNA/RNA Kit |

| Target Enrichment Panels | Predesigned sets targeting specific pathogen groups | Respiratory Pathogen Detection Kit, IDT xGen Exome v2 Panel |

The strategic selection between hybrid capture and amplicon sequencing methodologies depends heavily on the specific research objectives in vector-pathogen adaptation studies. Hybrid capture technologies, particularly newer simplified workflows, offer compelling advantages for comprehensive genomic characterization, discovery of novel variants, and studying complex evolutionary adaptations between vectors and pathogens. The method's capacity to handle larger genomic regions, detect diverse variant types, and provide more uniform coverage makes it particularly suitable for exploratory research on unknown pathogen adaptations and vector-pathogen coevolution.

Amplicon sequencing remains a valuable tool for targeted detection of known pathogens, rapid screening during outbreaks, and situations with limited nucleic acid input or computational resources. Its simplicity, lower cost, and faster turnaround time make it practical for surveillance applications and diagnostic confirmation.

As vector-borne diseases continue to pose significant global health challenges, the refined application of hybrid capture methods will play an increasingly important role in overcoming the host-DNA hurdle. These enrichment strategies enable researchers to generate high-quality pathogen genomic data from complex vector samples, accelerating our understanding of transmission dynamics, adaptive evolution, and the development of targeted interventions for disease control.

This guide provides an objective comparison of modern sequencing platforms and methodologies used for the genomic and transcriptomic analysis of vectors, with a specific focus on applications in disease vector adaptation research.

The choice between long-read and short-read sequencing technologies is fundamental, as each offers distinct advantages for different aspects of vector genomics.

Table 1: Comparison of Sequencing Technology Platforms

| Feature | Short-Read Sequencing (NGS) | Long-Read Sequencing (e.g., Oxford Nanopore, PacBio) |

|---|---|---|

| Read Length | Short (50-300 bp) | Long (several thousand to >10,000 bp) |

| Primary Applications | SNV and small indel detection, RNA-seq expression profiling | Structural variants, repetitive regions, de novo assembly, full-length transcript isoforms |

| Advantages | High per-base accuracy, low cost per gigabase, well-established protocols | Resolves mapping ambiguity, detects complex variation, captures complete transcripts |

| Limitations | Limited in complex genomic regions and for phasing haplotypes | Historically higher error rates, though modern chemistry has greatly improved accuracy [33] |

| Best for Vector Research | Variant screening across populations, gene expression studies | Building high-quality reference genomes, studying structural adaptation, resolving resistance gene clusters |

Performance and Validation Data

The implementation of a comprehensive long-read sequencing platform for genetic diagnosis demonstrates the performance achievable with current technologies. Validation using a benchmarked sample (NA12878) determined the analytical sensitivity at 98.87% and a specificity exceeding 99.99% [33].

Furthermore, a study evaluating 167 clinically relevant variants—including 80 SNVs, 26 indels, 32 SVs, and 29 repeat expansions—achieved an overall detection concordance of 99.4% (95% CI: 99.7%–99.9%) [33]. This demonstrates the capability of a single, integrated long-read assay to detect a broad spectrum of genetic variation with high accuracy, which is directly applicable to characterizing the diverse genomic alterations in disease vectors.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Comprehensive Variant Detection via Long-Read Sequencing

This protocol, adapted from a clinical diagnostics pipeline, is designed for broad detection of genetic variation in vectors, from single nucleotides to large structural variants [33].

- Sample Preparation: High-molecular-weight DNA is sheared, typically using g-TUBEs, to achieve a target fragment size distribution where approximately 80% of fragments are between 8 kb and 48.5 kb. DNA quality and quantity are assessed using instrumentation like an Agilent Tapestation and Qubit fluorometer [33].

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Libraries are prepared for sequencing on platforms such as the Oxford Nanopore PromethION. The process involves adapting the sheared DNA fragments for the specific sequencing technology.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: This is a crucial step where an integrated pipeline utilizes a combination of multiple, publicly available variant callers (eight were used in the cited study) to accurately identify SNVs, indels, SVs, and repetitive elements [33].

- Validation: The pipeline's performance is benchmarked against well-characterized reference samples with known variants to confirm sensitivity and specificity.

Protocol 2: Transcriptome Sequencing for Insecticide Resistance

This protocol outlines the process for identifying gene expression changes associated with traits like insecticide resistance in vectors such as Aedes aegypti [34].

- Sample Collection & Strain Selection: Collect vector samples from the field. For comparative studies, include a susceptible reference strain (e.g., Bora7) and a resistant strain (e.g., KhanhHoa7) [34].

- RNA Extraction & Library Prep: Extract total RNA from the samples. Prepare sequencing libraries, which historically have been well-suited for Illumina short-read platforms for transcript quantification.

- Sequencing & Data Analysis: Sequence the libraries to a sufficient depth (e.g., generating over 65 million reads per strain). Assemble the reads into genes and perform differential expression analysis to identify upregulated and downregulated genes in the resistant strain compared to the susceptible one [34].

- Functional Analysis: Focus on key gene families implicated in resistance mechanisms, such as Cytochrome P450s, Glutathione S-transferases (GST), and ABC transporters [34].

Diagram 1: Workflow for vector genome and transcriptome sequencing.

Key Reagents and Research Solutions

Successful sequencing projects depend on high-quality starting material and reliable reagents.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|

| g-TUBEs (Covaris) | Used for gentle shearing of genomic DNA to the ideal fragment size for long-read library preparation [33]. |

| DNA/RNA Extraction Kits (e.g., Qiagen DNeasy) | For the purification of high-quality, intact nucleic acids from vector samples, which is critical for long-read sequencing [33]. |

| Oxford Nanopore Ligation Sequencing Kit | Prepares the sheared and end-prepped DNA for sequencing on Nanopore platforms by adding motor proteins and adapters [33]. |

| Single-Microbe DNA Barcoding Kit (Atrandi Biosciences) | Enables high-throughput single-cell DNA barcoding and whole-genome amplification within semi-permeable capsules for microbiome studies [35]. |

| ZymoBIOMICS Gut Microbiome Standard | A defined microbial community used as a spike-in control to validate sample preparation and sequencing accuracy in metagenomic studies [35]. |

Analysis of Signaling and Metabolic Pathways in Vector Adaptation

Genomic and transcriptomic analyses reveal key molecular pathways involved in vector adaptation. Research on the dengue mosquito (Aedes aegypti) has shown that insecticide resistance is driven by the concerted upregulation of metabolic detoxification pathways [34].

Key genes significantly overexpressed in resistant strains include:

- Cytochrome P450s (CYP4C21, CYP4G15, CYP6A8, CYP9E2)

- Glutathione S-transferase (GST1)

- ABC transporters [34]

These genes represent core components of the metabolic resistance pathway, enabling vectors to break down or expel insecticides.

Diagram 2: Core metabolic pathway for insecticide resistance.

Vector-borne diseases present a formidable challenge to global public health, with their transmission dynamics intricately shaped by the complex molecular interactions between pathogens, vectors, and human hosts. The emerging field of comparative genomics has begun to unravel the molecular determinants of vector competence—the inherent capacity of an insect to transmit diseases. Key genomic features separating vector insects from their non-vector counterparts include expansions in gene families related to immunity, olfaction, digestion, detoxification, and salivary secretion [36]. These molecular adaptations, forged through natural selection and urban adaptations, create the fundamental biological context in which diagnostic technologies must operate.

Within this genomic framework, multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) panels represent a technological revolution for diagnosing vector-borne diseases. These assays enable the simultaneous detection of multiple pathogens in a single reaction, addressing the critical challenge of symptomatic overlap between different infections. For diseases like dengue, Zika, and chikungunya, which share similar clinical presentations including fever, rash, and arthralgia, multiplex PCR provides a powerful tool for accurate differential diagnosis, guiding appropriate clinical management and public health responses [37]. This review comprehensively compares the performance characteristics, methodological approaches, and practical applications of various multiplex PCR platforms for vector-borne disease diagnostics, contextualized within the genomic landscape of disease transmission.

Performance Comparison of Multiplex PCR Panels

The diagnostic performance of multiplex PCR panels varies significantly across different platforms and target pathogens. The following table summarizes key performance metrics from recent evaluations of multiplex PCR systems for detecting vector-borne and other infectious diseases.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Selected Multiplex PCR Panels

| Platform/Assay | Target Pathogens | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Turnaround Time | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BioFire FilmArray Global Fever Panel [38] [39] | 19 pathogens including Crimean-Congo HFV, Dengue, Ebola, Plasmodium spp. | 85.71% overall (varies by pathogen: CCHFV 100%, Dengue 100%, Plasmodium spp. 95.65%, Leptospira 50%) | 96.0% negative percentage agreement | <1 hour | Low detection for Salmonella enterica spp. and Leptospira spp. |

| ZCD Multiplex rRT-PCR [37] | Zika, Chikungunya, and Dengue viruses | Improved Zika detection vs. comparator | High specificity; no cross-reactivity with other arboviruses | ~1.5 hours | Limited to three pathogens; requires optimization |

| FMCA-based Multiplex PCR [40] | SARS-CoV-2, Influenza A/B, RSV, Adenovirus, M. pneumoniae | LOD: 4.94-14.03 copies/µL | No cross-reactivity with non-target respiratory pathogens | 1.5 hours | Not specifically designed for vector-borne pathogens |

| BioFire FilmArray Pneumonia Panel [41] | 18 bacteria, 3 atypical bacteria, 7 antibiotic resistance genes | 89% vs. conventional culture | 83% vs. conventional culture | 2.5-4 hours | Limited spectrum for some bacteria |

The BioFire FilmArray Global Fever Panel demonstrates particularly strong performance for high-consequence viral pathogens like Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever, Dengue, Ebola, and Marburg viruses, with perfect agreement (100%) compared to conventional diagnostics in recent studies [38] [39]. However, its lower sensitivity for bacterial pathogens like Leptospira (50%) and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi (0% in limited samples) highlights a significant limitation for comprehensive febrile illness testing [38]. This variability underscores the importance of understanding platform-specific strengths and weaknesses when selecting diagnostic tools for specific clinical and research applications.

For respiratory pathogens, the FMCA-based multiplex PCR shows exceptional analytical sensitivity with limits of detection between 4.94 and 14.03 copies/µL and high precision (intra-assay CVs ≤ 0.70%, inter-assay CVs ≤ 0.50%) [40]. This technical performance is comparable to more established systems but at a significantly reduced cost (approximately $5 per sample), demonstrating the potential for economic accessibility in resource-limited settings.

Methodological Approaches in Multiplex PCR Development

Nucleic Acid Extraction and Sample Preparation

The foundation of any reliable multiplex PCR assay lies in optimal nucleic acid extraction and sample preparation. For the ZCD assay (Zika, Chikungunya, and Dengue multiplex RT-PCR), RNA extraction is performed using 200 µL of sample with automated systems like the KingFisher Flex Purification System and MagMAX viral/pathogen nucleic acid isolation kits [42]. This standardized approach ensures consistent yield and purity, critical for assay reproducibility. Similarly, in the FMCA-based respiratory panel, nucleic acids are extracted from nasopharyngeal swabs using automated systems with integrated RNA/DNA extraction kits, with some protocols incorporating a centrifugation step (13,000 × g for 10 minutes) to remove debris from stored samples [40].

Primer and Probe Design Strategies

Sophisticated primer and probe design is essential for specific multiplex detection. The ZCD assay employed primers and probes designed against highly conserved regions of each viral genome, with in silico verification using the BLAST tool against NCBI databases to ensure specificity [37]. For the FMCA-based respiratory panel, researchers introduced an innovative approach using base-free tetrahydrofuran (THF) residues at specific probe positions, creating abasic sites that minimize the impact of potential base mismatches among different subtypes on the probe's melting temperature [40]. This modification enhances probe-target hybridization stability across variant strains, improving assay robustness.

Amplification Conditions and Detection Methods

Amplification protocols must balance sensitivity with specificity in multiplex formats. The ZCD assay uses the following cycling conditions: 52°C for 15 minutes for reverse transcription, followed by 94°C for 2 minutes, then 45 cycles of 94°C for 15 seconds, 55°C for 20 seconds (with acquisition), and 68°C for 20 seconds [37]. The FMCA-based approach employs reverse transcription-asymmetric PCR with unequal primer ratios to favor production of single-stranded DNA, enhancing probe accessibility during subsequent melting curve analysis [40]. For detection, the FMCA method performs post-PCR melting curve analysis from 40°C to 80°C at 0.06°C/s, generating distinct melting peaks for each pathogen.

Genomic Insights into Vector-Pathogen Interactions

Understanding the molecular basis of vector competence provides crucial context for developing targeted diagnostic approaches. Comparative genomics reveals that the differential ability of insect species to transmit pathogens stems from variations in key immunological pathways, salivary gland proteins, and midgut receptors [36]. The diagram below illustrates the primary molecular pathways determining vector competence for disease transmission.

These molecular pathways directly impact pathogen load and distribution within the vector, which in turn influences detection sensitivity and sampling strategies for surveillance. The Toll, IMD, and JAK-STAT immunological pathways modulate pathogen susceptibility and replication within vectors [36]. Additionally, salivary gland tropism and midgut infection barriers determine the efficiency of pathogen transmission and potential detection in different vector tissues [36]. Understanding these genomic factors enables more targeted diagnostic development, as primer and probe design can be optimized for pathogen strains most likely to overcome these vector-specific barriers.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions