Explicit vs. Implicit Solvent Models in Molecular Dynamics: A Comprehensive Guide for Computational Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of explicit and implicit solvent models for molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, tailored for researchers and professionals in computational biophysics and drug development.

Explicit vs. Implicit Solvent Models in Molecular Dynamics: A Comprehensive Guide for Computational Researchers

Abstract

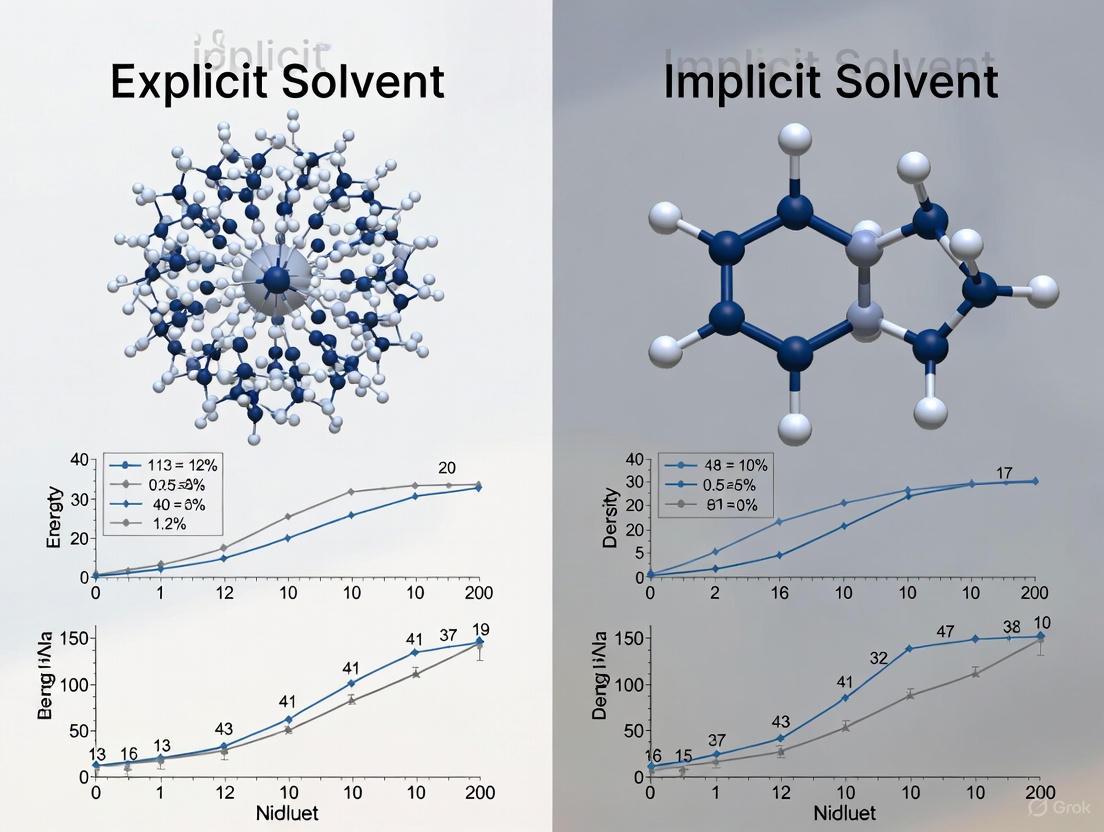

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of explicit and implicit solvent models for molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, tailored for researchers and professionals in computational biophysics and drug development. It covers the foundational principles of both approaches, detailing how explicit models treat solvent molecules individually while implicit models use a continuum approximation. The scope extends to methodological applications across diverse systems like proteins, nucleic acids, and ligands, offering practical guidance for troubleshooting common pitfalls and optimizing simulation protocols. A critical validation section synthesizes evidence from benchmark studies on solvation energy accuracy, conformational sampling efficiency, and performance in modeling complex biological processes, empowering scientists to make informed choices for their specific research objectives.

Understanding the Core Principles: How Explicit and Implicit Solvent Models Work

In molecular dynamics (MD) research, the choice of how to model the solvent environment is a fundamental decision that significantly influences the accuracy, computational cost, and biological relevance of simulations. The two primary approaches—explicit and implicit solvation—represent distinct paradigms for incorporating solvent effects. This guide provides an objective comparison of their performance, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies, to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

Core Principles and Theoretical Foundations

The explicit and implicit solvent models are grounded in different physical representations and theoretical frameworks.

Explicit Solvent Models treat solvent as discrete molecules, with each water molecule or ion represented as an individual particle [1]. This approach employs classical molecular mechanics (MM) force fields to compute interactions, utilizing terms for bond stretching, angle bending, torsions, and non-bonded interactions described by potentials like Lennard-Jones [1]. Models such as TIP3P and the Simple Point Charge (SPC) model are widely used for water, typically fixing molecular geometry and placing parametrized point charges on interaction sites [1]. This paradigm provides a spatially resolved, physical description of the solvent, enabling the study of specific solute-solvent interactions like hydrogen bonding and micro-solvation effects [1] [2].

Implicit Solvent Models, also known as continuum models, replace discrete solvent molecules with a homogeneously polarizable medium characterized by macroscopic properties like the dielectric constant (ε) [1] [3]. The solute is embedded in a molecular-shaped cavity within this continuum. The model accounts for solvation free energy through several components: cavity formation (energy cost of creating a void in the solvent), electrostatic interactions (stabilization of the solute's charge distribution), and non-electrostatic contributions from dispersion and repulsion [1] [4]. The electrostatic component is typically computed by solving the Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) equation or its efficient approximation, the Generalized Born (GB) equation [3] [4].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Solvent Models

| Feature | Explicit Solvent Models | Implicit Solvent Models |

|---|---|---|

| Solvent Representation | Discrete molecules (e.g., TIP3P water) [1] | Continuum dielectric medium [1] |

| Theoretical Basis | Molecular mechanics force fields [1] | Continuum electrostatics (PB/GB) [3] [4] |

| Key Interactions | Specific H-bonds, van der Waals, direct solute-solvent contacts [2] | Mean-field electrostatic and non-polar effects [1] [3] |

| Spatial Resolution | Atomistic, spatially resolved [1] | Averaged, no atomic detail of solvent [1] |

Performance and Efficiency Benchmarking

Quantitative comparisons reveal critical trade-offs between physical accuracy and computational efficiency, which are highly system-dependent.

Accuracy in Reproducing Physical Behavior

Explicit models generally provide a more realistic physical description because they capture specific, local solvent interactions. They accurately reproduce solvent density fluctuations and ordering around solutes, which is crucial for processes like ion solvation and the stabilization of specific protein conformations through water-bridged hydrogen bonds [1]. Implicit models, being a mean-field approximation, fail to capture these local fluctuations and specific interactions, which can be a significant source of inaccuracy [1] [5]. For instance, a 2017 study found that explicit models showed better agreement with experimental solvation free energies for organic molecules than the tested implicit models [6].

However, implicit models can provide a reasonable description of the thermodynamic behavior of bulk solvent and are successfully applied to compute hydration Gibbs energies (ΔhydG) when specific solvent effects are less critical [1] [3].

Computational Cost and Sampling Speed

The computational demand of the two paradigms differs drastically, directly impacting the feasible timescales for simulation.

Explicit solvent simulations are computationally expensive because they require simulating thousands of solvent molecules. The majority of the computational cost is spent calculating solvent-solvent interactions, which scale poorly with system size [7] [5]. A key benchmark study systematically compared the particle mesh Ewald (PME) explicit solvent method with a Generalized Born (GB) implicit solvent model [8]. The speedup in conformational sampling for implicit solvent was found to be highly dependent on the type of conformational change, as detailed in Table 2.

Table 2: Conformational Sampling Speedup of Implicit vs. Explicit Solvent

| Type of Conformational Change | System Description | Approximate Sampling Speedup (GB vs. PME) |

|---|---|---|

| Small (Dihedral flips) | Protein (4,812 atoms) | ~1-fold (minimal speedup) [8] |

| Large (DNA unwrapping, tail collapse) | Nucleosome complex (25,100 atoms) | ~1 to 100-fold [8] |

| Mixed (Protein folding) | Miniprotein (166 atoms) | ~7-fold [8] |

The study concluded that this speedup is primarily due to the reduction in solvent viscosity in implicit models, which smoothens the free-energy landscape and reduces friction during conformational transitions, rather than major alterations to the free-energy landscapes themselves [8]. Furthermore, the algorithmic computational cost of implicit models is lower for small systems because they eliminate the need to compute forces for thousands of solvent atoms [8].

Experimental and Simulation Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and meaningful results, specific protocols must be followed for simulations using either paradigm.

Protocol for Explicit Solvent Simulations

- System Setup: The solute (e.g., a protein or drug-like molecule) is placed in the center of a simulation box. The box is then filled with pre-equilibrated solvent molecules (e.g., TIP3P water) using tools like GROMACS, CHARMM, or Tinker [1] [9]. The size of the box is chosen to ensure the solute is separated from its periodic image by a sufficient distance (e.g., 1.0 nm or more).

- Neutralization and Ion Concentration: Ions (e.g., Na⁺, Cl⁻) are added to neutralize the system's net charge and to achieve a physiologically relevant ionic concentration (e.g., 150 mM NaCl) [9].

- Energy Minimization: The system undergoes energy minimization (e.g., via steepest descent or conjugate gradient algorithms) to remove any steric clashes and unfavorable interactions introduced during setup.

- Equilibration: Short simulations are run with positional restraints on the solute's heavy atoms. This allows the solvent and ions to relax around the solute. Typically, equilibration is done first in the NVT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature) to stabilize the temperature, followed by the NPT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) to stabilize the density [8].

- Production MD: The restraints are removed, and a production MD simulation is run to sample the system's dynamics. Long-range electrostatics are typically handled using the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method [8].

Protocol for Implicit Solvent Simulations

- Model Selection: Choose an appropriate implicit solvent model (e.g., GB-Neck2, PCM, or SMD) based on the solute and property of interest [1] [3] [5].

- Parameter Assignment: The solute is described using a molecular mechanics force field (e.g., AMBER, CHARMM). The implicit model requires parameters such as the solvent dielectric constant (e.g., ~80 for water), solute dielectric constant (often set to 1-4 for the interior of biomolecules), and atomic radii which are used to define the cavity [3] [4].

- Simulation Setup: Since there are no explicit solvent molecules, the system consists only of the solute. No box or periodic boundary conditions are strictly necessary, though they can sometimes be used.

- Energy Calculation and Dynamics: The solvation free energy is calculated on-the-fly as a mean-field potential. For GB models, this involves computing the effective Born radii for each atom, which measure their degree of burial, and then using an analytical formula to compute the polarization energy [3] [8]. This term is added to the vacuum force field energy and forces for energy evaluations and MD propagation.

The workflow below illustrates the fundamental differences in setting up and running these simulations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

This section details essential computational tools and models used in solvent simulations.

Table 3: Essential Tools and Models for Solvent Simulations

| Tool/Solution | Type | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| TIP3P / SPC Water Models [1] | Explicit Solvent Force Field | Classical, non-polarizable models representing water with 3 interaction sites; widely used for biomolecular simulations. |

| GB-Neck2 [5] | Implicit Solvent Model | A Generalized Born model designed to improve the accuracy of Born radii calculations, a common modern implicit solvent. |

| Polarizable Continuum Model (PCM) [1] [4] | Implicit Solvent Model | A quantum chemical implicit model that solves the Poisson equation for a solute in a molecular-shaped cavity. |

| Solvation Model based on Density (SMD) [1] [4] | Implicit Solvent Model | A universal solvation model parameterized for a wide range of solvents and solutes, often used in quantum chemistry. |

| Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) [8] | Computational Algorithm | An efficient method for handling long-range electrostatic interactions in periodic explicit solvent simulations. |

| Machine Learning Potentials (MLPs) [2] [5] | Emerging Technology | Surrogate models (e.g., ACE, eSEN) trained on quantum data to provide near-quantum accuracy at lower cost for explicit solvent MD. |

Emerging Trends and Future Outlook

The field is rapidly evolving with new technologies that aim to bridge the gap between the accuracy of explicit solvents and the speed of implicit models.

Machine Learning-Augmented Implicit Models are showing great promise. For example, a recent Graph Neural Network (GNN) based implicit model was trained on a diverse set of 3 million molecular structures to learn the mean forces exerted by an explicit solvent environment [5]. This model achieved accuracy on par with explicit solvent simulations while providing an up to 18-fold increase in sampling rate, addressing the long-standing challenge of capturing local solvation effects with a continuum description [5].

Machine Learning Potentials for Explicit Solvent are another frontier. These ML models are trained on high-level quantum mechanical data for specific solute-solvent clusters, then used to run explicit solvent MD at a fraction of the computational cost of direct quantum mechanics [2] [7]. This approach allows for the routine modeling of chemical reactions in explicit solvent, capturing specific solute-solvent interactions that are missed by implicit models [2].

Furthermore, large-scale datasets like Meta's Open Molecules 2025 (OMol25) and pre-trained universal models are providing unprecedented resources to develop and benchmark the next generation of both explicit and implicit solvent methodologies [10].

In molecular dynamics (MD) research, the choice between explicit and implicit solvent models represents a fundamental trade-off between computational cost and physical detail. Explicit models, which simulate individual solvent molecules, are computationally expensive and limit sampling. Implicit solvent models address this by representing the solvent as a continuous dielectric medium, dramatically accelerating simulations and improving sampling efficiency [11] [12]. Among these, the Poisson–Boltzmann (PB), Generalized Born (GB), and Polarizable Continuum Model (PCM) families are the most widely used. This guide provides a objective comparison of these three core implicit solvent models, detailing their theoretical bases, accuracy, computational performance, and applicability in biomolecular simulations and drug development.

Theoretical Foundations and Key Differences

At the core of implicit solvent models is the partitioning of the solvation free energy, ΔGsolv, into polar (electrostatic) and nonpolar components [11] [13]. The polar component is calculated differently by each model, while the nonpolar component is often estimated based on the Solvent-Accessible Surface Area (SASA) or related terms accounting for cavity formation and van der Waals interactions [11] [12] [13].

The following diagram illustrates the shared conceptual foundation and key differentiators of each model.

Model Formulations

Poisson–Boltzmann (PB) Model: The PB equation provides a rigorous mathematical description of electrostatic interactions between a solute and a surrounding dielectric medium, incorporating spatial variations in dielectric properties and ionic strength [11]. It is solved numerically on a grid, which is computationally demanding but is often considered an accuracy standard for biomolecular electrostatics [14] [15].

Generalized Born (GB) Model: The GB model is a pairwise analytical approximation to the PB formalism [11]. Its computational efficiency stems from avoiding numerical solutions and representing the electrostatic solvation energy as a sum over atom pairs [14] [12]. This makes it particularly suitable for MD simulations where forces must be calculated frequently.

Polarizable Continuum Model (PCM): PCM and its variants, such as the Conductor-like Screening Model (COSMO), were developed primarily in the context of quantum chemistry to include solvation effects in electronic structure calculations [11] [16]. These models use a boundary element method to represent the solvent as a polarizable continuum and are adept at describing solvent effects on molecular properties, spectra, and reaction mechanisms [11] [13].

Performance and Accuracy Comparison

Quantitative Accuracy in Biomolecular Applications

Experimental and benchmark studies directly compare the performance of these models in predicting solvation and binding energies. The table below summarizes key findings from a study comparing implicit solvent models and their implementations for protein-ligand binding [14].

Table 1: Accuracy comparison of implicit solvent models for solvation and binding energy calculations

| System Tested | Metric | Poisson-Boltzmann (APBS) | Generalized Born (GBNSR6) | COSMO (MOPAC) | PCM (DISOLV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small Molecules (104) | Correlation (r) with Explicit Solvent | 0.953 - 0.966 | 0.953 - 0.966 | 0.87 - 0.93 | 0.953 - 0.966 |

| Small Molecules (104) | Correlation (r) with Experiment | 0.87 - 0.93 | 0.87 - 0.93 | 0.87 - 0.93 | 0.87 - 0.93 |

| Proteins (19) | Correlation (r) with Explicit Solvent | 0.65 - 0.99 | 0.65 - 0.99 | 0.65 - 0.99 | 0.65 - 0.99 |

| Protein-Ligand Complexes (15) | Correlation (r) with Explicit Solvent | 0.76 - 0.96 | 0.76 - 0.96 | 0.76 - 0.96 | 0.76 - 0.96 |

| Overall Assessment | Most accurate for desolvation energies | Best combination of accuracy and speed | Good for small molecules, parameter sensitive | High numerical accuracy, computationally intensive |

A central finding is that for small molecules, all tested implicit solvent models show a high correlation (0.87–0.93) with experimental hydration energies [14]. Furthermore, for ligands, the correlation with explicit solvent results was similarly high (0.953–0.966) for PB, GB, and PCM implementations within the same parameterization, suggesting that the choice of force field and parameters can be as critical as the choice of model itself [14]. For calculating desolvation energies of protein-ligand complexes, the Poisson–Boltzmann equation and the Generalized Born method were identified as the most accurate [14].

Computational Cost and Practical Performance

The theoretical complexity of each model directly impacts its computational speed and typical applications.

Table 2: Computational characteristics and typical use cases

| Model | Computational Cost | Scalability | Typical Applications in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) | High (Numerical grid-based) | Slower for large systems | Benchmarking; analysis of static structures; binding energy calculations [14] [15] |

| Generalized Born (GB) | Low (Analytical, pairwise) | Excellent for large systems | Molecular dynamics simulations; protein folding; long-timescale conformational sampling [14] [12] |

| PCM/COSMO | Medium to High (Boundary elements) | Slower for large solutes | Quantum chemistry calculations; reaction mechanism studies; spectroscopy prediction [11] [16] |

The Generalized Born model consistently offers the best combination of accuracy and computational speed for biomolecular MD simulations [14] [12]. Its efficiency enables the simulation of large systems and enhanced conformational sampling that would be prohibitively expensive with explicit solvent or PB models.

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

To ensure reliable comparisons, studies follow rigorous benchmarking protocols. The following workflow visualizes a typical methodology for evaluating implicit solvent models against explicit solvent references and experimental data.

Key steps in the protocol include [14]:

- Test Set Construction: Assembling a diverse set of structures, including small molecules, proteins, and protein-ligand complexes, to ensure comprehensive benchmarking. For example, a referenced study used 19 small proteins, 104 small molecules, and 15 protein-ligand complexes [14].

- Parameterization: Performing calculations using consistent force fields (e.g., MMFF94, AMBER) or quantum-chemical methods (e.g., semi-empirical PM7) to isolate the effect of the solvation model from other variables [14].

- Reference Data Generation: Using explicit solvent simulations (e.g., Thermodynamic Integration with the TIP3P water model) as a computational reference, and experimental hydration energies where available, for validation [14].

- Calculation and Analysis: Running solvation energy calculations with each implicit model and evaluating performance through linear correlation coefficients and absolute errors against the reference data.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Selecting the right software tools is critical for applying these models in research. The table below lists key software packages and their supported implicit solvent methods.

Table 3: Key software implementations for implicit solvent modeling

| Software / Tool | Supported Implicit Models | Primary Function and Context |

|---|---|---|

| APBS [14] | Poisson-Boltzmann | Calculates electrostatic properties for biomolecules; often used for analysis of static structures. |

| DISOLV & MCBHSOLV [14] | PCM, COSMO, S-GB | Implements multiple models with high numerical accuracy; used in docking and inhibitor development. |

| GBNSR6 [14] | Generalized Born | A GB implementation noted for high accuracy in estimating hydration free energies of small molecules and proteins. |

| MOPAC [14] | COSMO | Features semi-empirical quantum chemistry with COSMO solvation; popular for post-processing docking results. |

| BIOVIA Discovery Studio [17] | GB, PB | Provides GUI-driven workflows for MD and docking using CHARMm, including implicit solvent (GB/PB) simulations. |

| Quantum Chemistry Packages | PCM, COSMO, SMD | Software like Gaussian, ORCA, and GAMESS implement these models for electronic structure calculations in solution [11] [16]. |

Future Directions

The field of implicit solvation is being advanced through machine learning (ML) and hybrid approaches [11] [16]. ML-augmented models are now being developed to act as accurate surrogates for PB calculations or to provide residual corrections to GB/PB baselines, learning from explicit solvent data to capture effects like specific hydrogen bonding [11] [16]. Furthermore, knowledge transfer from molecular mechanics to quantum mechanics is enabling the creation of ML-based implicit solvents compatible with any functional and basis set, offering a promising path to more accurate and efficient solvation treatments in quantum chemistry [16].

The choice of how to represent the solvent environment is a fundamental consideration in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, directly influencing the accuracy, computational cost, and biological relevance of the results. In the study of biomolecules and drug development, solvent effects modulate structure, stability, dynamics, and function [18]. Researchers are primarily faced with two opposing paradigms: explicit solvent models, which treat each solvent molecule as a discrete entity, and implicit solvent models, which average solvent effects into a continuous, polarizable medium [8] [18]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these approaches, framed within the broader thesis of optimizing computational resources for scientific discovery. We summarize quantitative performance data, detail experimental protocols from key studies, and visualize complex workflows to inform researchers and development professionals.

Core Concepts and Fundamental Trade-offs

Explicit Solvent Models

Explicit solvent models, such as the TIP3P water model used with the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method for handling long-range electrostatics, place individual solvent molecules around the solute [8]. This offers a high-degree of realism by capturing specific solute-solvent interactions, such as hydrogen bonding, and solvent-solvent correlations. The main drawback is computational expense, as simulating thousands of solvent molecules drastically increases the number of particles and interactions that must be computed at every simulation step [2] [18].

Implicit Solvent Models

Implicit solvent models, such as the Generalized Born (GB) model, approximate the solvent as a continuous dielectric medium characterized by a dielectric constant [8] [18]. This drastically reduces the number of particles in the simulation, leading to lower computational costs. A key advantage is the reduction of solvent viscosity, which can speed up conformational sampling by lowering the friction experienced by the solute [8]. However, these models lack atomic-level detail for solvent interactions, which can be critical for processes like ligand binding or where specific solvent structuring plays a role [2].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The trade-offs between explicit and implicit solvent models can be quantified in terms of conformational sampling speed, computational resource requirements, and accuracy in reproducing experimental observables. The following tables summarize key findings from comparative studies.

Table 1: Comparative Sampling Speed and Computational Efficiency

| System/Process Studied | Explicit Solvent (PME) | Implicit Solvent (GB) | Observed Speedup in Conformational Sampling | Key Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small Conformational Changes (Dihedral angle flips in a protein) [8] | Baseline | Comparable | ~1-fold | Sampling rate of dihedral transitions |

| Large Conformational Changes (Nucleosome tail collapse, DNA unwrapping) [8] | Baseline | Significantly faster | ~1 to 100-fold | Rate of large-scale structural transitions |

| Mixed Changes (Folding of a miniprotein) [8] | Baseline | Faster | ~7-fold | Folding rate |

| Computational Cost (Algorithmic) | High for large systems due to explicit water interactions [8] | Lower for small systems; scaling can vary [8] | Highly system-dependent | Simulation time steps per processor (CPU) time |

Table 2: Accuracy and Practical Application Benchmarks

| Aspect | Explicit Solvent | Implicit Solvent | Notes and Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Realism | High; captures specific solute-solvent interactions [2] | Lower; lacks atomic detail of solvent [2] | Critical for processes reliant on specific molecular recognition |

| Free Energy Landscapes | Can be altered by implicit model approximations [8] | Altered thermodynamics can affect kinetics and populations [8] | Requires validation for the system of interest |

| Solvation Free Energy Prediction | Accurate but computationally intensive (e.g., via MD) [19] | Reasonable accuracy with efficient methods (e.g., uESE continuum model) [19] | uESE with MMFF94 structures offers efficient, reasonably accurate predictions [19] |

| Conformational Ensembles | Gold standard (within force field accuracy) [20] | New GNN-based implicit solvent (GNNIS) shows high accuracy vs. explicit [20] | GNNIS reduces computation time from days to minutes for organic solvents [20] |

Emerging Paradigms: Machine-Learned Potentials and Hybrid Methods

Machine-learned potentials (MLPs) have emerged as powerful surrogates for quantum mechanical calculations, offering near-first-principles accuracy at a fraction of the computational cost [21] [22] [2]. These can be applied in several ways to address the solvent representation challenge.

Full Explicit Solvation with MLPs

MLPs can be trained to describe an entire system, including both solute and explicit solvent molecules, at a quantum-chemical level of theory. This approach, while potentially expensive, allows for highly accurate modeling of chemical reactions in solution [2]. For instance, a general active learning (AL) strategy can generate efficient MLPs for a Diels-Alder reaction in water and methanol, yielding reaction rates that agree with experimental data [2].

Table 3: The Researcher's Toolkit: Key Computational Methods

| Research Reagent (Method/Model) | Type | Primary Function | Example Implementation/Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) [8] | Explicit Solvent | Efficiently handles long-range electrostatic interactions in periodic systems. | Often used with TIP3P water model. |

| Generalized Born (GB) [8] | Implicit Solvent | Approximates solvation energy via an analytical formula; reduces system size. | Various parameterizations exist (e.g., in AMBER). |

| FieldSchNet [21] | ML/MM Model | Machine-learned interatomic potential for excited-states; incorporates MM electric field effects. | Used for nonadiabatic dynamics (e.g., furan in water). |

| Active Learning (AL) Loop [2] | ML Training Workflow | Constructs data-efficient training sets for MLPs by iteratively identifying and adding new, informative configurations. | Uses descriptor-based selectors like SOAP. |

| Universal Model for Atoms (UMA) [10] | Machine-Learned Potential | A universal neural network potential trained on massive datasets (e.g., OMol25). | Provides high accuracy across diverse chemical spaces. |

| GNN-based Implicit Solvent (GNNIS) [20] | Machine-Learned Solvation | A graph neural network that rapidly predicts conformational ensembles in organic solvents. | Reduces computation time from days to minutes. |

Hybrid ML/MM Approaches

A promising alternative is the hybrid Machine Learning/Molecular Mechanics (ML/MM) scheme, which mirrors the established QM/MM concept. In this setup, an MLP describes the core region of interest (e.g., a chromophore), while the surrounding environment is treated with a classical MM force field [21]. The FieldSchNet architecture, for example, is designed to incorporate the electric field generated by the MM point charges, enabling accurate excited-state nonadiabatic dynamics of molecules in explicit solvents, such as furan in water [21]. This approach can significantly reduce cost while maintaining a high degree of accuracy by limiting the quantum-mechanical treatment to the essential part of the system.

Workflow for Developing Machine-Learned Potentials

The construction of robust and data-efficient MLPs for solvated systems often relies on iterative active learning workflows. The following diagram illustrates a general strategy for training MLPs to model chemical processes in explicit solvents.

Active Learning for MLPs: This workflow shows the iterative process of building an MLP. It begins with a small initial training set from reference calculations (e.g., cluster models with explicit solvent). An initial MLP is trained and used to run molecular dynamics. New structures encountered during MD are analyzed by a selector (e.g., using Smooth Overlap of Atomic Positions (SOAP) descriptors) to determine if they are outside the known data distribution. If so, they are added to the training set, and the model is retrained. This loop continues until the MLP is robust for production simulations [2].

The choice between explicit and implicit solvent models involves a clear, quantifiable trade-off between atomic detail and computational cost. Explicit models remain the gold standard for capturing specific solvent effects but at a high computational price, which can slow conformational sampling. Implicit models offer significant speedups and are excellent for rapid sampling and screening, though they risk missing nuanced, specific interactions. Emerging methods, particularly machine-learned potentials and hybrid ML/MM schemes, are blurring these traditional lines. By offering routes to near-quantum accuracy with reduced computational burden, either for full explicit solvent systems or in hybrid embeddings, they represent a powerful new toolkit for simulating complex biological and chemical processes in their native solvent environments.

This guide objectively compares the performance of explicit-solvent and implicit-solvent methods in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, focusing on how they model the two key physical components of solvation free energy: the electrostatic (ΔGelec) and non-polar (ΔGvdW) contributions. Supporting experimental data and detailed methodologies are provided to inform the selection of approaches for research and drug development.

Defining the Solvation Free Energy Components

In computational studies, the process of transferring a solute from a gas phase into an aqueous solution is conceptually decomposed into two stages. First, a cavity is created in the solvent to accommodate the uncharged solute, with the associated free energy termed the non-polar component (ΔGvdW). Second, the solute cavity is gradually charged, with the associated free energy termed the electrostatic component (ΔGelec) [23]. While the total solvation free energy (ΔG) is a state function, its decomposed components are path-dependent and defined by this specific thermodynamic process [23].

The table below summarizes the physical origins and common modeling approaches for these two components.

| Solvation Component | Physical Origin | Common Explicit-Solvent Calculation Method | Common Implicit-Solvent Approximation Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Polar (ΔGvdW) | Cost of cavity formation; solute-solvent van der Waals interactions [23]. | Thermodynamic Integration (TI) or Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) [23]. | Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA) [23]. |

| Electrostatic (ΔGelec) | Polarization of the solvent by the charged solute [23]. | Thermodynamic Integration (TI) or Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) [23]. | Poisson-Boltzmann (PB), Generalized Born (GB), or Linear Response Approximation [23]. |

Performance Comparison: Explicit vs. Implicit Solvation

The choice between explicit and implicit solvent models involves a direct trade-off between computational accuracy and efficiency, which is quantified in the table below.

| Performance Metric | Explicit-Solvent Models (e.g., PME/TIP3P) | Implicit-Solvent Models (e.g., Generalized Born) |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Speed (Conformational Sampling) | Baseline (1x) | 1x to 100x faster, highly system-dependent [8]. |

| Typical ΔGvdW Accuracy | High (Benchmark) | Moderate; SASA-based models can be inaccurate for organic molecules [23]. |

| Typical ΔGelec Accuracy | High (Benchmark) | High for common biological molecules; can fail for systems with high charge density [24]. |

| Handling of Solvent Viscosity | Physically accurate | Effectively reduces solvent friction, accelerating large-scale conformational changes [8]. |

| Treatment of Specific Water Interactions | Excellent | Poor |

Supporting Experimental Data

A systematic study comparing the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) explicit-solvent method and a GB implicit-solvent model found the speedup in conformational sampling to be highly system-dependent [8]:

- For small conformational changes (e.g., dihedral angle flips), the speedup was approximately 1-fold.

- For large conformational changes (e.g., nucleosome tail collapse, DNA unwrapping), the speedup ranged from ∼1-fold to ∼100-fold [8].

- For a mixed case (folding of a miniprotein), the speedup was approximately 7-fold [8].

The primary driver for this accelerated sampling is the reduction of effective solvent viscosity in implicit models, rather than major alterations to the underlying free-energy landscapes [8].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility, here are the detailed methodologies for key computational experiments cited in this guide.

Protocol 1: Calculating ΔGvdW Using Proximal Distribution Functions (pDFs)

This method uses pre-computed structural data to estimate solvation free energies rapidly [23].

- pDF Generation: From MD simulations of small peptide molecules (e.g., alanine and glycine monomers), calculate proximal distribution functions (pDFs) for each solute atom type. A pDF, g⊥k(r), describes the average solvent density around the nearest solute atom k,

- Solvent Structure Reconstruction: For a larger solute (e.g., deca-alanine), reconstruct the 3D solvent density around it by assigning a pre-computed pDF to every grid point in the space surrounding the solute, based on the identity of and distance to the nearest solute atom,

- Energy Calculation: Use the reconstructed solvent density to estimate the average solute-solvent van der Waals interaction energy (UvdW),

- Thermodynamic Integration: Calculate ΔGvdW by numerically integrating UvdW along a pathway that gradually scales the van der Waals interactions between the solute and solvent.

This pDF-based approach has been shown to reproduce benchmark ΔGvdW values from explicit-solvent TI within ∼1 kcal/mol accuracy for systems like butane, propanol, and polyglycine [23].

Protocol 2: Deep-Learning for Poisson-Boltzmann Solvation Forces

This protocol uses a deep neural network to approximate the results of a Poisson-Boltzmann calculation, dramatically speeding up implicit-solvent simulations [25].

- Training Data Generation: Use a program like SurfPB to solve the Poisson-Boltzmann equation for many thousands of molecular snapshots. For each snapshot, calculate the decomposed solvation free energy and the corresponding solvation force on every atom,

- Network Architecture and Training: Build a deep neural network where the input data are the internal coordinates of the molecule. Train the network using the data from Step 1, so that it learns to predict the solvation free energies and atomic forces directly from the molecular structure,

- Simulation Application: Integrate the trained model into an MD simulation. At each step, the network provides the solvation forces, bypassing the need to solve the computationally expensive PB equation.

This method has been demonstrated to generate free-energy landscapes for peptides like Ala-dipeptide and Met-enkephalin that closely resemble those obtained from explicit-solvent simulations [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below catalogues essential computational tools and methods for solvation free energy studies.

| Research Reagent | Function in Solvation Studies |

|---|---|

| Thermodynamic Integration (TI) | A rigorous, benchmark method for calculating free energy differences in explicit solvent by slowly coupling/decoupling interactions [23]. |

| Proximal Distribution Functions (pDFs) | Pre-computed, transferable functions that reconstruct solvent density around solutes for rapid estimation of ΔGvdW [23]. |

| Generalized Born (GB) Model | An implicit-solvent method that provides an analytical approximation for electrostatic solvation free energy (ΔGelec), offering speed advantages [8]. |

| Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) Solver | An implicit-solvent method that numerically solves a fundamental equation of electrostatics to compute ΔGelec, often considered more accurate than GB but slower [25]. |

| Neural Network Potentials (NNPs) | Machine-learning models (e.g., Meta's eSEN, UMA) trained on quantum chemical data to provide highly accurate and fast potential energy surfaces, bridging the gap between accuracy and cost [10]. |

| Variational Implicit-Solvent Model (VISM) | A coarse-grained model that determines equilibrium solute-solvent interfaces and solvation free energies by minimizing a free-energy functional [26]. |

Computational Workflows in Solvation Modeling

The diagram below illustrates the logical relationships and workflow differences between the primary methods discussed for calculating solvation properties.

Choosing Your Solvent Model: Practical Applications Across Biomolecular Systems

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are indispensable tools for studying the structure, function, and dynamics of biological molecules, with particular importance in understanding protein folding and conformational changes. A central choice in setting up these simulations is how to represent the solvent environment. Explicit solvent models treat water molecules as individual entities, providing high accuracy at the cost of substantial computational resources. In contrast, implicit solvent models treat the solvent as a continuous dielectric medium, offering significant computational advantages while traditionally sacrificing some accuracy [8] [27].

This guide objectively compares these approaches, focusing on the application of implicit solvent models for studying protein folding and conformational dynamics. We provide experimental data, detailed methodologies, and practical resources to help researchers select appropriate models for their specific scientific questions.

Fundamental Principles and Computational Speed

How Implicit Solvent Models Work

Implicit solvent models, particularly the Generalized Born (GB) model, approximate solvation effects through mathematical formulations rather than explicit water molecules. These models calculate solvation free energy by combining polar (electrostatic) and non-polar (cavity formation) contributions. The electrostatic component is typically derived from the Generalized Born equation, while the non-polar component is often estimated using the solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) [28] [8].

The fundamental energy equations in GB models are:

[ E{ij}^{elec} = E{ij}^{vac} + E_{ij}^{solv} ]

[ E{ij}^{solv} = -\frac{1}{2}\left[1\epsilon{in} - \frac{\exp(-0.73\kappa f{ij}^{GB})}{\epsilon{out}}\right]\frac{qi qj}{f_{ij}^{GB}} ]

[ f{ij}^{GB} = \sqrt{r{ij}^2 + Bi Bj \exp(-r{ij}^2/4Bi B_j)} ]

Here, (Bi) and (Bj) are effective Born radii representing atomic burial, (qi) and (qj) are atomic charges, (r{ij}) is interatomic distance, and (\epsilon{in}) and (\epsilon_{out}) are internal and external dielectric constants [8].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The table below summarizes key performance differences between explicit and implicit solvent models observed in comparative studies:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Explicit vs. Implicit Solvent Models

| Performance Metric | Explicit Solvent (TIP3P/PME) | Implicit Solvent (GB) | Speedup Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small conformational changes(dihedral angle flips) | Reference baseline | Comparable sampling | ~1-fold [8] |

| Large conformational changes(nucleosome tail collapse, DNA unwrapping) | Reference baseline | Significantly faster sampling | ~1-100 fold [8] |

| Mixed changes(miniprotein folding) | Reference baseline | Faster sampling | ~7-fold [8] |

| Computational efficiency(simulation steps per CPU time) | Slower for small systems | Faster for small systems | System-dependent [8] |

| Sampling accuracy(native structure preference) | High accuracy | 14/17 proteins correct [29] | N/A |

The performance advantages of implicit solvent models stem from two key factors: reduced computational burden from eliminating explicit water molecules, and lower effective solvent viscosity that accelerates conformational sampling [8]. As one study noted, "implicit-solvent simulations can speed up conformational sampling significantly" due to these combined effects [8].

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Standard Implicit Solvent Simulation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a typical workflow for protein folding studies using implicit solvent models:

Detailed Simulation Protocol

Based on successful protein folding studies, the following protocol has demonstrated effectiveness across various protein systems:

System Setup:

- Start with fully extended protein structures or experimental coordinates when available

- Employ the GB-Neck2 implicit solvent model with mbondi3 intrinsic atomic radii

- Use the ff14SBonlysc force field, which combines ff99SB with updated side chain dihedral parameters [29]

Simulation Parameters:

- Utilize the AMBER14 software package with GPU acceleration

- Apply no cutoff for nonbonded interactions in implicit solvent

- Use a 2-fs time step with bonds involving hydrogen constrained using SHAKE

- Maintain constant temperature using Langevin dynamics with a collision frequency of 1-2 ps⁻¹ [29]

Enhanced Sampling (for larger proteins):

- Implement replica exchange molecular dynamics (REMD) with 24-48 replicas

- Temperatures typically span 270-550 K, exponentially spaced

- Attempt exchanges between neighboring temperatures every 1-2 ps

- This approach enables comprehensive sampling of folded and unfolded states [29]

Validation Metrics:

- Calculate Cα root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) relative to experimental structures

- Compute fraction of native contacts (Q) using a cutoff of 4.5 Å

- Perform cluster analysis to identify predominant conformations

- Compare backbone order parameters with experimental NMR data when available [29]

Key Research Findings and Applications

Success in Protein Folding Predictions

Comprehensive folding studies have demonstrated the capabilities of modern implicit solvent models. One landmark study simulated 17 proteins with diverse sizes, secondary structures, and topologies, achieving successful folding to native-like conformations (Cα RMSD < 3Å) for 16 of the 17 systems [29].

Table 2: Protein Folding Performance with Implicit Solvent Models

| Protein System | Size (aa) | Topology | Simulation Method | Minimum Cα RMSD (Å) | Native Preference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLN025 | 10 | β-hairpin | Standard MD | < 2.0 | Yes [29] |

| Trp-cage | 20 | α-helical | Standard MD | < 2.0 | Yes [29] |

| Fip35 WW domain | 35 | β-sheet | Standard MD | < 2.0 | Yes [29] |

| Villin HP36 | 36 | α-helical | Standard MD | < 2.0 | Yes [29] |

| BBA | 38 | α/β | Standard MD | < 2.0 | Yes [29] |

| Homeodomain | 56 | α-helical | REMD | 1.9 | Yes [29] |

| α3D | 73 | α-helical | REMD | 2.5 | Yes [29] |

| λ-repressor | 80 | α-helical | REMD | 4.4 | Yes [29] |

| NuG2 | 92 | α/β | REMD | 4.8 | No [29] |

The exceptional performance across diverse protein topologies indicates that current implicit solvent models have achieved significant transferability. As the study concluded, this approach enables "accurate all-atom simulated folding for 16 of 17 proteins with a variety of sizes, secondary structure, and topologies" using relatively inexpensive GPU hardware [29].

Conformational Sampling Across Systems

The efficiency of implicit solvent models varies significantly depending on the type of conformational change being studied:

- Small changes like dihedral angle flips show minimal sampling advantage

- Large-scale changes such as nucleosome tail collapse and DNA unwrapping demonstrate dramatic speedups of 1-100 fold

- Mixed changes like miniprotein folding show approximately 7-fold sampling acceleration [8]

This variability highlights the system-dependent nature of implicit solvent advantages, suggesting that researchers should select solvent models based on their specific sampling requirements.

Emerging Innovations: Machine Learning Approaches

Machine Learning Potentials for Implicit Solvation

Recent advances integrate machine learning with implicit solvation to address traditional limitations. The λ-Solvation Neural Network (LSNN) represents a significant innovation by combining graph neural networks with alchemical variable derivatives to enable accurate free energy calculations [28].

Traditional machine learning potentials trained solely through force-matching determine energies only up to an arbitrary constant, making them unsuitable for absolute free energy comparisons. The LSNN approach overcomes this limitation by incorporating derivatives with respect to electrostatic (λₑₗₑc) and steric (λₛₜₑᵣᵢc) coupling factors during training [28].

The diagram below illustrates this novel machine learning framework:

Training Methodology and Performance

The LSNN model employs an expanded loss function that incorporates multiple physical derivatives:

[ \mathcal{L} = wF\left(\left\langle\frac{\partial U{\text{solv}}}{\partial\mathbf{r}i}\right\rangle - \frac{\partial f}{\partial\mathbf{r}i}\right)^2 + w{\text{elec}}\left(\left\langle\frac{\partial U{\text{solv}}}{\partial\lambda{\text{elec}}}\right\rangle - \frac{\partial f}{\partial\lambda{\text{elec}}}\right)^2 + w{\text{steric}}\left(\left\langle\frac{\partial U{\text{solv}}}{\partial\lambda{\text{steric}}}\right\rangle - \frac{\partial f}{\partial\lambda{\text{steric}}}\right)^2 ]

This approach, trained on approximately 300,000 small molecules, achieves free energy predictions with accuracy comparable to explicit-solvent alchemical simulations while offering computational speedups, establishing "a foundational framework for future applications in drug discovery" [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Computational Tools for Implicit Solvent Simulations

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Simulation Software | AMBER, CHARMM, GROMACS | Provides implementations of implicit solvent models and force fields for MD simulations [8] [29] |

| Implicit Solvent Models | GB-Neck2, GBMV2, SASA | Calculate solvation effects without explicit water molecules [28] [29] |

| Force Fields | ff14SBonlysc, CHARMM36m | Define potential energy functions and parameters for proteins [27] [29] |

| Enhanced Sampling | Replica Exchange MD (REMD) | Accelerates conformational sampling, especially for larger proteins [29] |

| Machine Learning Potentials | LSNN, eSEN, UMA | Neural network potentials trained on quantum chemical data for accurate energy predictions [28] [10] |

| Analysis Tools | RMSD, Native Contact Fraction, Cluster Analysis | Quantify simulation accuracy and identify predominant conformations [29] |

| Specialized Hardware | GPU Accelerators | Dramatically increase simulation speed, enabling microsecond/day performance [29] |

Implicit solvent models have evolved into sophisticated tools that successfully balance computational efficiency with physical accuracy for protein folding and conformational dynamics studies. While explicit solvent models remain the gold standard for certain applications, modern implicit solvent approaches can achieve native-like folding for diverse protein topologies with significantly reduced computational resources.

The integration of machine learning potentials represents the cutting edge, addressing traditional limitations in free energy calculations while maintaining computational advantages. As these methods continue to mature, they offer promising avenues for accelerating drug discovery and expanding our understanding of biomolecular dynamics across previously inaccessible timescales.

This guide objectively compares the performance of explicit and implicit solvent models in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of nucleic acids, focusing on DNA/RNA flexibility and protein-nucleic acid interactions.

Performance Comparison of Solvent Models

The table below summarizes the core performance characteristics, advantages, and limitations of explicit and implicit solvent models based on current research.

| Feature | Explicit Solvent Models | Implicit Solvent Models (Standard GBSA) | Implicit Solvent Models (Advanced/Hybrid) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Cost | High; large system size due to explicit water molecules [12] [30] | Lower; no explicit solvent degrees of freedom [12] [31] | Moderate; higher than standard implicit but lower than explicit [30] |

| Sampling Speed | Slower; limited by solvent viscosity [12] [32] | Faster (∼1 to 100-fold); reduced solvent friction [12] [32] | Varies; designed for improved sampling efficiency [30] |

| Typical Applications | High-accuracy studies of structure, dynamics, and specific ion/water binding [30] [1] | Protein folding, long-timescale conformational changes, rapid screening [31] [3] | Challenging nucleic acid systems (e.g., RNA), incorporating specific ion effects [30] |

| Treatment of Electrostatics | Explicit Coulombic interactions with water and ions [1] | Continuum dielectric (e.g., Generalized Born, Poisson-Boltzmann) [31] [3] | Combined physics-based and empirical corrections (e.g., LD+PB) [30] |

| Treatment of Nonpolar Interactions | Explicit van der Waals and hydrophobic interactions [1] | Empirical model (e.g., Solvent-Accessible Surface Area, SASA) [31] [3] | Often includes improved nonpolar terms [31] |

| Performance with Nucleic Acids | Generally robust but computationally demanding [30] | Often poor; can cause irrational structural distortion in RNAs [30] | More robust; better stability for RNA duplexes, hairpins, and tRNAs [30] |

| Key Limitations | Computationally expensive, slow conformational sampling [12] [30] | Poor handling of specific solute-solvent interactions (e.g., H-bonds), flawed electrostatics for highly charged molecules [12] [30] [31] | Parameterization complexity, may not capture all explicit solvent effects [30] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Data

Quantitative Speed Comparison in Conformational Sampling

A systematic study compared the sampling speed of explicit (TIP3P water with Particle Mesh Ewald) and implicit (Generalized Born) solvent models for various biomolecular conformational changes [32]. The results are summarized in the table below.

| System and Conformational Change | Simulation Time (Explicit) | Simulation Time (Implicit) | Sampling Speedup (GB vs. PME) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small (Dihedral angle flips in a protein) | Nanosecond to microsecond scale | Nanosecond to microsecond scale | ~1-fold (minimal speedup) [32] |

| Large (Nucleosome tail collapse, DNA unwrapping) | Nanosecond to microsecond scale | Nanosecond to microsecond scale | ~1 to 100-fold (highly variable) [32] |

| Mixed (Folding of a miniprotein) | Nanosecond to microsecond scale | Nanosecond to microsecond scale | ~7-fold (at same temperature) [32] |

Experimental Protocol: The simulations were performed using the AMBER software package. The explicit solvent model used was TIP3P water with Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) for handling long-range electrostatics. The implicit solvent model was a Generalized Born (GB) model. For each system, multiple MD simulations were run with both solvent models, and the speed of conformational change was assessed by measuring the time taken to observe specific transitions (e.g., dihedral flips, folding events). The speedup was calculated as the ratio of the time required to observe the transition in explicit solvent versus implicit solvent [32].

Novel Implicit Solvent Model for RNA Stability

Experimental Challenge: Standard implicit solvent models like GBSA often fail to maintain the native structure of RNA, leading to severe irrational distortion early in simulations. This is attributed to inadequate treatment of electrostatic screening and dielectric saturation effects near the highly charged RNA backbone [30].

Proposed Solution: A novel implicit solvent model that combines the Langevin-Debye (LD) model to account for dielectric saturation with the Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) equation to describe screening by monovalent counter-ions [30].

Experimental Protocol:

- System Preparation: Three RNA systems of increasing complexity were studied: a 20-nucleotide (nt) A-form RNA duplex, a 29-nt sarcin/ricin loop (SRL rRNA), and a 75-nt tRNA. Initial structures were obtained from the PDB or built with tools like TINKER. Critical Mg²⁺ ions from crystal structures were retained [30].

- Simulation Details: Simulations were performed using a modified version of the TINKER/MD package (STINKER) with the AMBER99 force field. The electrostatic interaction energy was calculated using the combined LD+PB model. Key parameters included a Debye-Hückel screening constant (κ) of 0.15 (∼225 mM NaCl) for the duplex and κ=0.1 (∼100 mM NaCl) for SRL rRNA and tRNA. A solvation energy term based on solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) was added [30].

- Analysis: The structural stability of simulations using the novel LD+PB model was compared against simulations with traditional implicit solvent models and, where available, explicit solvent simulations. Metrics like Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) from native crystal structures were used to assess stability [30].

Results: The LD+PB implicit solvent model provided reasonable agreement with explicit solvent simulations and maintained structural stability for all three RNA targets, which traditional GBSA models failed to do [30].

Emerging Machine Learning and Benchmarking Approaches

The field is rapidly evolving with new data-driven approaches. The Open Molecules 2025 (OMol25) dataset provides over 100 million molecular snapshots calculated with high-accuracy density functional theory (DFT), heavily featuring biomolecules [33] [10]. This resource trains Machine Learned Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) that can simulate large systems with DFT-level accuracy much faster, showing promise for modeling complex nucleic acid interactions [33].

Concurrently, new standardized benchmarking frameworks are being developed to objectively compare MD methods. One such framework uses weighted ensemble sampling to efficiently explore protein conformational space and supports evaluating both classical and machine learning-based models across more than 19 metrics [34].

Experimental Workflows and Methodologies

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and key components of the novel implicit solvent model developed for RNA simulations, as detailed in the experimental protocol [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The table below lists key computational tools and parameters used in the featured implicit solvent experiments for nucleic acids [30].

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in Nucleic Acid Simulation |

|---|---|

| AMBER99 Force Field | A molecular mechanics force field providing parameters for potential energy calculations of DNA and RNA molecules [30]. |

| Generalized Born (GB) Model | An approximate implicit solvent model that calculates electrostatic solvation energy; standard versions often fail for RNA but are a baseline for development [30] [31]. |

| Langevin-Debye (LD) Model | Accounts for dielectric saturation, a phenomenon where the screening ability of water is reduced near highly charged groups like the RNA backbone [30]. |

| Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) Equation | A more rigorous implicit solvent model that describes electrostatic interactions between the solute and a continuum solvent with ions [30] [3]. |

| Solvent-Accessible Surface Area (SASA) | Models the non-polar contribution to solvation energy, which is the cost of creating a cavity in the solvent and the van der Waals interactions [30] [3]. |

| Debye-Hückel Screening Constant (κ) | A parameter that controls the shielding by salt ions in the implicit solvent; it is set to mimic specific NaCl concentrations (e.g., 100mM or 225mM) [30]. |

| STINKER/TINKER MD Package | Molecular dynamics software used to run the simulations with the modified LD+PB implicit solvent model [30]. |

Strategies for Protein-Ligand Binding and Free Energy of Solvation Calculations

The accurate calculation of protein-ligand binding affinities and solvation free energies represents a cornerstone of computational biophysics and structure-based drug design. These predictions hinge critically on how the solvent environment is modeled, leading to two predominant computational strategies: explicit solvent models, which treat solvent molecules as discrete entities, and implicit solvent models, which represent the solvent as a continuous dielectric medium [35]. The choice between these approaches involves a fundamental trade-off between computational efficiency and physical accuracy, a balance that must be carefully considered for research and development applications. This guide provides an objective comparison of these strategies, focusing on their performance in quantifying protein-ligand interactions and solvation thermodynamics, framed within the broader thesis of explicit versus implicit solvent molecular dynamics research.

Fundamental Principles of Solvation Modeling

Explicit Solvent Models

Explicit solvent models simulate individual solvent molecules, typically using rigid water models such as TIP3P, TIP4PEw, and OPC [36]. These models explicitly represent specific solute-solvent interactions, including hydrogen bonding and microscopic hydrophobic effects. The main computational cost arises from the need to simulate thousands of water molecules and average over their configurations to obtain thermodynamic properties. The Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method is commonly used to handle long-range electrostatic interactions in these periodic systems [8].

Implicit Solvent Models

Implicit solvent models approximate the solvent as a featureless continuum with dielectric properties of water, dramatically reducing computational cost by eliminating explicit solvent degrees of freedom [35]. The Generalized Born (GB) model provides an analytical approximation for electrostatic solvation energy [36] [8], while Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) models offer more numerically exact solutions to the continuum electrostatic equations [14]. Other approaches include the Polarized Continuum Model and COSMO [14]. The solvation free energy (ΔGs) in these models is calculated as the sum of polar (electrostatic) and non-polar (cavity formation and van der Waals) components [35].

Performance Comparison: Accuracy and Efficiency

Accuracy in Solvation and Binding Free Energy Prediction

The accuracy of solvent models varies significantly depending on the system being studied and the specific property being calculated. The table below summarizes key performance metrics from comparative studies.

Table 1: Accuracy Comparison of Solvent Models for Various Molecular Systems

| System Type | Model Category | Representative Models | Performance Metrics | Reference Standard |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small Molecules | Implicit | PCM, GB, COSMO, PB | High correlation with experiment (R=0.87-0.93) for hydration energies [14] | Experimental hydration energies |

| Small Molecules | Explicit | TIP3P, TIP4PEw, OPC | Generally better agreement with experiment than implicit models [6] | Experimental hydration energies |

| Protein-Ligand Complexes | Implicit | GBNSR6 | RMSD=7.04 kcal/mol from TIP3P reference; reducible with parameter scaling [36] | Explicit solvent (TIP3P) |

| Protein-Ligand Complexes | Explicit | TIP3P vs. TIP4PEw | Significant differences in ΔΔGpol (up to ~9 kcal/mol) between models [36] | Cross-comparison of explicit models |

| Protein Solvation | Implicit | Various | Substantial discrepancies (up to 10 kcal/mol) from explicit solvent reference [14] | Explicit solvent (TIP3P) |

For small molecules, multiple implicit solvent models show strong correlation with experimental hydration free energies, with correlation coefficients ranging from 0.87 to 0.93 [14]. However, a 2017 comparative study found that explicit solvent models generally provided better agreement with experimental solvation free energies than implicit models for organic molecules in organic solvents [6].

For protein-ligand binding energy calculations, the deviations between implicit and explicit models can be substantial. One study reported a root mean square deviation (RMSD) of 7.04 kcal/mol for GBNSR6 implicit binding affinities compared to TIP3P explicit reference values [36]. Notably, this discrepancy is comparable to the variations observed between different explicit water models themselves (e.g., RMSD of 5.30 kcal/mol between TIP4PEw and TIP3P) [36]. The absolute electrostatic binding free energy (ΔΔGpol) estimates between different explicit models can differ by up to ~9 kcal/mol, highlighting the absence of a uncontested "gold standard" [36].

Computational Efficiency and Sampling Speed

The computational efficiency advantage of implicit solvent models translates into significantly faster conformational sampling, though the magnitude of this speedup is highly system-dependent.

Table 2: Computational Efficiency Comparison Between Implicit and Explicit Solvent Models

| Conformational Change Type | System Description | Sampling Speedup (GB vs. PME) | Primary Speedup Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small Changes | Dihedral angle flips in proteins | ~1-fold (minimal speedup) [37] | Algorithmic efficiency |

| Large Changes | Nucleosome tail collapse, DNA unwrapping | ~1 to 100-fold [37] [32] | Reduced solvent viscosity |

| Mixed Changes | Folding of a miniprotein | ~7-fold [37] [32] | Combined factors |

| General | Various biomolecular systems | ~2 to 20-fold commonly reported [8] | Reduced degrees of freedom |

For small conformational changes such as dihedral angle flips, implicit solvent provides minimal sampling speedup (~1-fold) when simulations are run at the same temperature [37]. However, for larger-scale conformational changes such as nucleosome tail collapse and DNA unwrapping, implicit solvent models can accelerate sampling by between approximately 1 and 100 times [37] [32]. For mixed conformational changes like miniprotein folding, speedups of approximately sevenfold have been observed [37] [32].

This enhanced sampling speed primarily stems from reduced effective solvent viscosity in implicit solvent simulations rather than fundamental alterations to the free-energy landscape [37] [8]. The computational speedup is particularly pronounced for smaller systems where the implicit solvent calculation overhead is minimal compared to explicit solvent calculations [8].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Protocol for Explicit Solvent Binding Free Energy Calculations

Explicit solvent calculations typically follow a rigorous thermodynamic pathway to compute binding affinities:

System Preparation: The protein-ligand complex is solvated in a water box (e.g., TIP3P, TIP4PEw) with dimensions ensuring sufficient clearance between the solute and box edges. Counterions are added to neutralize the system [36].

Equilibration: The system undergoes energy minimization and gradual heating to the target temperature (e.g., 300 K), followed by equilibration in the NPT ensemble to achieve proper density [36].

Thermodynamic Integration: The binding free energy is computed using alchemical transformation methods where the ligand is gradually decoupled from its environment. The coupling parameter (λ) is varied from 0 (fully interacting) to 1 (non-interacting) in discrete steps [35].

Analysis: The free energy difference is calculated by integrating the derivative of the Hamiltonian with respect to λ over the transformation pathway: ΔG = ∫⟨∂U/∂λ⟩λ dλ [35].

This protocol is computationally demanding but provides a theoretically rigorous approach for estimating binding affinities, serving as a reference standard for implicit model validation [36].

Standard Protocol for Implicit Solvent Binding Free Energy Calculations

Implicit solvent calculations utilize continuum approximations to streamline the binding affinity estimation:

Structure Preparation: The protein-ligand complex is prepared with appropriate protonation states, often determined using computational tools like the H++ server to set titratable groups according to computed pKa values at the isoelectric point [36].

Surface Definition: The solvent-accessible surface is defined using algorithms such as the Lee-Richards molecular surface, which determines the dielectric boundary between solute and continuum solvent [36].

Energy Calculation: The electrostatic solvation energy is computed using Generalized Born (e.g., GBNSR6) or Poisson-Boltzmann methods. The binding free energy is estimated as: ΔGbind = ΔGs(complex) - ΔGs(protein) - ΔGs(ligand) [35].

Parameter Optimization: For GB models, effective Born radii are calculated to represent the degree of atom burial within the solute. These parameters may be optimized through single scaling factor adjustments to improve agreement with explicit solvent references [36].

This protocol is significantly faster than explicit solvent calculations, enabling rapid screening of multiple ligand poses and chemical modifications during drug design campaigns.

Visualization of Method Selection and Applications

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for selecting between implicit and explicit solvent approaches based on research objectives and system characteristics:

Diagram 1: Decision workflow for selecting between implicit and explicit solvent models based on research objectives, system characteristics, and available computational resources.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools and Methods for Solvation Free Energy Calculations

| Tool/Solution | Type | Primary Function | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| GBNSR6 | Implicit Solvent Model | Generalized Born approximation for electrostatic solvation | Protein-ligand binding affinity prediction [36] |

| APBS | Implicit Solvent Model | Numerical solution of Poisson-Boltzmann equation | Electrostatic potential mapping, solvation energy calculation [14] |

| TIP3P/TIP4PEw/OPC | Explicit Water Models | Rigid water models for explicit solvent simulations | Reference calculations, accurate binding free energies [36] |

| Thermodynamic Integration | Computational Method | Alchemical transformation for free energy calculation | Benchmarking implicit models, high-accuracy binding affinities [36] [35] |

| MMFF94/Amber12 | Force Fields | Molecular mechanical potential functions | Energy evaluation with implicit/explicit solvents [14] |

| DISOLV/MCBHSOLV | Software | Implementation of multiple implicit solvent models | Comparative studies, solvation energy calculations [14] |

The choice between explicit and implicit solvent models for protein-ligand binding and solvation free energy calculations involves navigating a fundamental trade-off between computational efficiency and physical accuracy. Explicit solvent models generally provide higher accuracy, particularly for systems with specific solvent interactions, but at substantially greater computational cost. Implicit solvent models offer remarkable efficiency gains—often orders of magnitude faster—enabling broader conformational sampling and high-throughput screening applications, though with potentially compromised accuracy for certain molecular systems.

For research requiring the highest possible accuracy in binding affinity prediction, particularly in systems with critical solvent-mediated interactions, explicit solvent models remain the preferred choice when computational resources permit. For applications demanding rapid sampling of conformational space or screening of multiple ligand candidates, implicit solvent models provide an efficient alternative with acceptable accuracy for many practical applications. The emerging generation of neural network potentials trained on massive quantum chemical datasets promises to potentially bridge this accuracy-efficiency gap in the future [10], but traditional explicit and implicit approaches will continue to serve as essential tools in computational biophysics and drug discovery for the foreseeable future.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are extensively used to study the structure and function of biological systems and to estimate critical properties like protein-ligand binding free energy, a crucial application in computer-aided drug discovery [28]. However, a significant factor affecting the accuracy and efficiency of these simulations is the treatment of solvation effects. Traditional explicit solvent models, which simulate individual solvent molecules surrounding the solute, offer high accuracy but at a substantial computational cost, often making them prohibitive for screening millions of drug candidates [28] [11].

Implicit solvent models (also known as continuum solvent models) provide a faster alternative by replacing discrete solvent molecules with a dielectric continuum, dramatically reducing the number of particle-particle interactions that need to be calculated [38] [12]. The primary advantage of this approach is computational efficiency, enabling rapid conformational exploration, enhanced sampling, and the simulation of large systems that would be otherwise infeasible [11] [12]. Classical implicit models like Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) and Generalized Born (GB) calculate the solvation free energy by partitioning it into polar (electrostatic) and non-polar (cavity formation and van der Waals) components, often estimated using the solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) [28] [11].

Despite their speed, these traditional implicit models have inherent limitations. The continuum approximation struggles to capture specific solvent-mediated interactions, such as water bridges, hydrogen bonds, and ion effects. They may also inadequately represent entropic contributions and the heterogeneous nature of biological environments [11] [38]. This accuracy-speed trade-off has motivated the integration of machine learning (ML) techniques to develop a new generation of implicit solvent models that aim to achieve near-explicit solvent accuracy while retaining computational efficiency [28] [11].

Performance Comparison: ML-Augmented vs. Traditional Solvent Models

The table below summarizes a objective performance comparison of various solvent modeling approaches, based on data from recent scientific publications.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Solvent Models for Molecular Dynamics

| Model Category | Specific Model | System Tested | Key Performance Metrics | Computational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Explicit Solvent | TIP3P [28] | Small Molecules [28] | Gold standard for accuracy; Captures specific solvent interactions [11] [2] | Low; High computational cost limits sampling and screening scale [28] [11] |

| Classical Implicit Solvent | GBSA / PBSA [28] | General Biomolecules [11] | Moderate accuracy; Prone to errors in non-polar contributions and local solvation effects [28] [11] | High; Significantly faster than explicit solvent by eliminating solvent degrees of freedom [11] [12] |

| ML-Augmented Implicit Solvent | LSNN (Lambda Solvation Neural Network) [28] | ~300,000 small molecules [28] | Free energy predictions comparable to explicit-solvent alchemical simulations [28] [39] | High; Offers computational speedup over explicit solvent [28] |

| ML-Augmented Implicit Solvent | DeepPot-SE based Model [38] | Alanine Dipeptide [38] | Predicted forces deviated by 0.4 kcal mol⁻¹ Å⁻¹ from reference; Free energy surface RMSD < 0.9 kcal mol⁻¹ [38] | Cost-effective for both training and inference in QM/MM simulations [38] |

| ML-Based Explicit Surrogate | ACE with Active Learning [2] | Diels-Alder reaction in water/methanol [2] | Reaction rates in agreement with experimental data; Captures specific solute-solvent interactions [2] | High as an ML potential; Lower cost than full QM simulation but requires training data generation [2] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The LSNN Model for Free Energy Calculations

A major drawback of many ML-based implicit solvent models is their reliance on force-matching alone. This approach optimizes a model to predict the forces on solute atoms but leaves the potential energy defined only up to an arbitrary constant, making the models unsuitable for calculating absolute free energies [28].

Core Innovation: The LSNN model introduces a novel training methodology that extends beyond force-matching. In addition to matching forces, the model is trained to match the derivatives of the solvation energy with respect to alchemical variables (specifically, electrostatic and steric coupling factors, ( \lambda{\text{elec}} ) and ( \lambda{\text{steric}} )) [28]. These variables are central to alchemical free energy calculation methods.

Modified Loss Function: The model is trained by minimizing a modified loss function ( \mathcal{L} ) [28]: [ \mathcal{L} = wF \left( \left\langle \frac{\partial U{\text{solv}}}{\partial \mathbf{r}i} \right\rangle - \frac{\partial f}{\partial \mathbf{r}i} \right)^2 + w{\text{elec}} \left( \left\langle \frac{\partial U{\text{solv}}}{\partial \lambda{\text{elec}}} \right\rangle - \frac{\partial f}{\partial \lambda{\text{elec}}} \right)^2 + w{\text{steric}} \left( \left\langle \frac{\partial U{\text{solv}}}{\partial \lambda{\text{steric}}} \right\rangle - \frac{\partial f}{\partial \lambda{\text{steric}}} \right)^2 ] Here, ( wF ), ( w{\text{elec}} ), and ( w{\text{steric}} ) are empirically tuned weights, ( U{\text{solv}} ) is the reference solvation potential, and ( f ) is the model's prediction. This multi-term loss ensures the model learns a consistent energy landscape where free energies can be meaningfully compared across different chemical species [28].

Architecture and Training: LSNN is a Graph Neural Network (GNN) trained on a large dataset of approximately 300,000 small molecules. The non-polar solvation contribution is predicted by the GNN and combined with an estimated polar component [28].

ML-Based Implicit Solvent from Explicit Solvent Data

Another approach, exemplified by work on alanine dipeptide, involves "deriving" an implicit solvent model directly from explicit solvent MD simulations [38].

Core Concept: The goal is to build a machine learning potential (MLP) that captures the solute-solvent interactions from an Average Solvent Environment Configuration (ASEC). The ASEC represents the average effect of the solvent on the solute, effectively creating a mean field potential [38].

Workflow and Training: The model is trained to minimize a loss function that measures the difference between the forces predicted by the MLP and the reference forces derived from explicit solvent simulations. The reference forces are computed as the mean forces on solute atoms averaged over multiple solvent configurations from explicit solvent MD [38]. This protocol can be applied to both molecular mechanics (MM) and quantum mechanical (QM) descriptions of the solute, enabling accurate and efficient ab initio MD simulations in solution [38].

Active Learning for Explicit Solvent ML Potentials

For modeling chemical reactions in explicit solvent where specific solute-solvent interactions are critical, a robust strategy involves using active learning (AL) to build machine learning potentials [2].

Workflow: This iterative process begins with a small set of reference configurations. An initial MLP is trained and used to run MD simulations. Structures that the MLP is uncertain about (identified using descriptor-based selectors like Smooth Overlap of Atomic Positions (SOAP)) are selected for computing reference QM energies and forces and are added to the training set. The model is retrained, and the cycle repeats until the MLP is robust and accurate [2]. This method ensures data efficiency by selectively labeling the most informative configurations.