Fitness Landscapes and Epistasis: Navigating Molecular Evolution from Theory to Clinical Application

This article synthesizes current research on fitness landscapes and epistasis to provide a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals.

Fitness Landscapes and Epistasis: Navigating Molecular Evolution from Theory to Clinical Application

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on fitness landscapes and epistasis to provide a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational concepts of genotype-to-fitness maps and the pivotal role of epistatic interactions in directing evolutionary trajectories. The content covers advanced methodologies for landscape reconstruction, the impact of environmental factors like drug pressure on landscape topography, and the statistical frameworks used to validate models against empirical data. By integrating theoretical insights with practical applications, particularly in understanding and predicting antimicrobial resistance, this resource aims to bridge the gap between evolutionary theory and the design of more robust therapeutic strategies.

The Topography of Evolution: Unraveling Fitness Landscapes and Epistasis

In evolutionary biology, the fitness landscape is a foundational model for visualizing the relationship between genotypes and reproductive success [1]. First introduced by Sewall Wright in 1932, this powerful metaphor conceptualizes genotypes as locations in a multidimensional space, with fitness represented as height, thus creating a topography of peaks (high fitness) and valleys (low fitness) [1] [2]. For decades, this heuristic has guided scientific intuition about evolutionary dynamics, suggesting that populations evolve by moving toward fitness peaks. However, recent empirical and theoretical advances have dramatically refined this classical concept, revealing a much more complex architecture in which genotype-phenotype (GP) maps play a central role [3] [4].

This whitepaper examines the modern conceptualization of fitness landscapes within the context of molecular evolution research, focusing particularly on the implications of epistatic interactions for evolutionary trajectories and drug development strategies. We synthesize insights from combinatorially complete empirical studies, analyze the structural properties of genotype networks, and provide technical protocols for landscape mapping. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these architectural principles is no longer abstract theory but a practical necessity for predicting resistance evolution and engineering stable biomolecules.

Historical Foundations and Theoretical Frameworks

Wright's Original Conceptualization

Sewall Wright's pioneering 1932 paper introduced fitness landscapes as a way to visualize evolution in genotypic space [1] [2]. His model made several key assumptions: each genotype has a well-defined replication rate (fitness); similar genotypes are close in the landscape; and evolution proceeds through a series of small genetic changes toward fitness maxima [1]. Wright visualized these landscapes as mountainous terrains with local peaks (points where all paths lead downhill) and valleys (regions from which many paths lead uphill) [1]. This topographical metaphor became iconic in evolutionary biology, particularly through Wright's influential diagrams depicting evolutionary dynamics across different population genetic regimes [2].

Despite its intuitive appeal, Wright's conceptualization faced significant challenges. His biographer, William Provine, criticized these diagrams as "unintelligible" and "meaningless in any precise sense" because Wright provided no explicit method for producing them from actual biological data [2]. Wright himself acknowledged that his representations were "useless for mathematical purposes" but defended them as necessary simplifications for understanding complex evolutionary processes [2]. This tension between heuristic value and mathematical precision continues to inform discussions about fitness landscape models.

The Genotype-Phenotype Map Framework

The modern extension of Wright's framework incorporates the formal concept of the genotype-phenotype (GP) map, coined by Pere Alberch in 1991 [5]. This model conceptualizes the relationship between an organism's full hereditary information (genotype) and its actual observed properties (phenotype) with greater sophistication than a straightforward one-to-one mapping [5]. The GP map framework accommodates several key features: a parameter space where phenotypes exhibit varying stability; transformational boundaries dividing different phenotype states; and explanations for polymorphism and polyphenism in populations [5].

Critical to this framework is the concept of genotype networks—sets of mutationally interconnected genotypes that all produce the same phenotype [3]. These networks reveal that the mapping from genotype to phenotype is typically many-to-one, with a highly skewed distribution where most phenotypes are realized by few genotypes, while a few phenotypes are realized by many genotypes [3]. This organization has profound implications for evolutionary dynamics, influencing robustness, evolvability, and the accessibility of phenotypic variations.

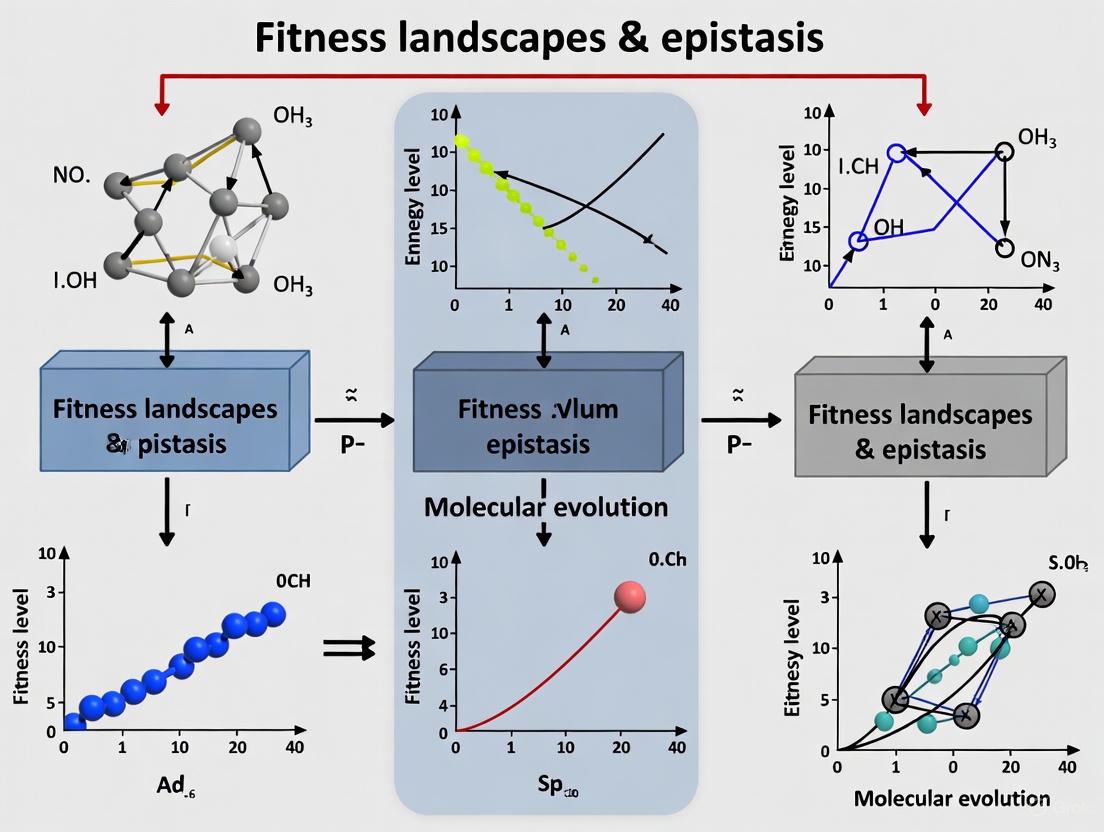

Figure 1: The conceptual evolution of fitness landscape theory from Wright's original metaphor to the modern synthesis incorporating empirical GP maps.

Empirical Mapping of Fitness Landscapes

Methodological Approaches

Combinatorially Complete Studies

A powerful approach for empirical landscape mapping involves creating combinatorially complete datasets in which researchers construct and assay all possible combinations of a set of mutations [6]. For n genetic changes, this requires analysis of 2n different combinations, enabling comprehensive assessment of epistatic interactions [6]. The experimental protocol typically involves:

- Selection of Mutations: Identifying specific amino acid residues or nucleotides where mutations affect the phenotype of interest.

- Combinatorial Construction: Systematically creating all possible combinations of selected mutations.

- Phenotypic Assaying: Quantifying fitness or fitness proxies (growth rate, enzyme activity, binding affinity) for each genotype under controlled conditions.

- Epistasis Analysis: Calculating interaction effects between mutations across different genetic backgrounds.

This approach has been applied to diverse biological systems, including metabolic enzymes, drug targets, viral proteins, and visible morphological mutants [6].

Protein Binding Microarrays

Recent advances in high-throughput technologies have enabled unprecedented empirical mapping of GP architectures. Protein binding microarrays provide particularly comprehensive data, measuring transcription factor binding preferences to all possible double-stranded DNA sequences of length eight (32,896 sequences) [3]. Each genotype is a DNA sequence, with the phenotype defined as its ability to bind one or more transcription factors [3]. The binding affinity is typically reported as an E-score, a nonparametric rank-based variant of the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney statistic ranging from -0.5 to 0.5 [3]. This technology enables high-resolution analysis of genotype network properties at scale.

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for combinatorially complete fitness landscape studies, from mutation selection to epistasis analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 1: Essential research reagents and methodologies for empirical fitness landscape mapping

| Reagent/Method | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Binding Microarrays | High-throughput measurement of transcription factor binding preferences to all possible DNA sequences of fixed length | Mapping DNA-protein interaction landscapes for 525 TFs across three eukaryotic species [3] |

| Combinatorially Complete Libraries | Systematic construction of all possible combinations of a set of mutations | Analysis of 2^n combinations of n mutations to precisely quantify epistatic effects [6] |

| E-score Metric | Nonparametric, rank-based statistic ranging from -0.5 to 0.5 that correlates with relative dissociation constant | Proxy for relative binding affinity in protein-DNA interaction studies; threshold of >0.35 indicates specific binding [3] |

| Genotype Network Analysis | Graph-based representation of mutational connections between genotypes with the same phenotype | Reveals small-world, assortative networks with extensive overlap and interface between different phenotypes [3] |

Architectural Properties of Empirical GP Maps

Universal Structural Features

Analysis of empirical GP maps from diverse biological systems has revealed striking commonalities in their architectural properties [3]:

Many-to-One Mapping: Most GP maps are highly redundant, with multiple genotypes producing the same phenotype. This redundancy creates extensive neutral networks of mutationally connected genotypes with identical phenotypes.

Skewed Genotype Distribution: The distribution of genotypes across phenotypes is highly non-uniform, with most phenotypes represented by few genotypes, while a few phenotypes are realized by many genotypes.

Mutational Interconnectedness: Genotypes with the same phenotype tend to form large, interconnected networks where any genotype can be transformed into any other through a series of mutations that preserve the phenotype.

Extensive Overlap: The genotype networks of different phenotypes ubiquitously interface with one another, enabling evolutionary transitions between phenotypes through minimal mutational changes.

These structural properties have profound implications for evolutionary dynamics, facilitating both phenotypic stability (robustness) and the capacity for evolutionary innovation (evolvability).

Epistasis and Landscape Ruggedness

Epistasis—the interaction between mutations whereby the effect of one mutation depends on the presence of others—fundamentally shapes fitness landscape topography [6]. Empirical studies have revealed several consistent patterns:

Table 2: Patterns of epistasis observed in empirical fitness landscapes

| Pattern | Description | Evolutionary Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Diminishing Returns Epistasis | Beneficial mutations have smaller effects when they occur in fitter genetic backgrounds [6] | Constrains infinite fitness growth; promotes diversity in adapting populations |

| Sign Epistasis | The sign (beneficial/deleterious) of a mutation's effect changes depending on genetic background [6] | Creates fitness valleys; constrains evolutionary pathways |

| Reciprocal Sign Epistasis | Two mutations are each deleterious alone but beneficial in combination [6] | Creates alternative fitness peaks; can trap populations at local optima |

| Concavity-Driven Epistasis | Negative epistasis arises from concave mappings from biochemical traits to fitness [6] | Explains prevalence of diminishing returns pattern across biological systems |

Landscape "ruggedness" refers to the prevalence of multiple fitness peaks and valleys, which is directly determined by patterns of epistasis. While early theoretical work suggested that high-dimensional landscapes might be overwhelmingly rugged, empirical studies reveal that biological fitness landscapes are often smoother than expected from random models, with correlated fitness effects among related genotypes [6].

Evolutionary Dynamics on Fitness Landscapes

Constrained Evolutionary Trajectories

One of the most robust findings from empirical landscape studies is that the number of accessible evolutionary paths is typically severely limited [6]. Among all theoretically possible mutational pathways, only a small fraction is "permissible"—meaning that each step increases fitness without traversing fitness valleys [6]. This constraint arises primarily from sign epistasis, which creates fitness valleys that cannot be crossed by natural selection without temporary reductions in fitness [6].

For example, in a classic study of TEM β-lactamase evolution, only approximately 6 of 120 possible evolutionary pathways to increased antibiotic resistance were accessible under selection [6]. Similar constraints have been observed across diverse biological systems, including metabolic enzymes, viral proteins, and transcription factor binding sites.

From Static Landscapes to Dynamic Seascapes

The classical fitness landscape model is static, but real evolutionary environments are constantly changing. The concept of fitness seascapes extends the model to account for this dynamism, representing adaptive surfaces whose peaks and valleys shift over time due to changing environments, drug exposures, immune surveillance, and co-evolutionary interactions [1].

Factors driving fitness seascape dynamics include [1]:

- Environmental fluctuations: Changes in resource availability, temperature, or other abiotic factors

- Therapeutic interventions: Drug exposure and cycling in clinical treatments

- Host-pathogen coevolution: Red Queen dynamics, where species must constantly evolve to maintain their fitness relative to interacting species

- Immune system pressure: Particularly relevant for pathogens and cancer cells

This dynamic framework is essential for modeling long-term evolutionary outcomes, especially in clinical contexts where drug cycling strategies deliberately alter selective pressures to steer pathogen evolution toward less resistant genotypes [1].

Figure 3: Comparison of evolutionary trajectories in static fitness landscapes versus dynamic fitness seascapes. In dynamic environments, previously beneficial mutations can become deleterious (red arrows), and neutral paths can become accessible (yellow nodes), fundamentally altering evolutionary outcomes.

Applications in Molecular Evolution and Drug Development

Predicting and Managing Antibiotic Resistance

Fitness landscape models have proven particularly valuable for understanding and combating the evolution of antibiotic resistance. Studies of resistance enzymes like TEM β-lactamase have revealed how constrained evolutionary pathways can be exploited therapeutically [6]. Key insights include:

Pathway Predictability: The limited number of accessible evolutionary paths to high-level resistance enables prediction of likely resistance trajectories in clinical settings.

Collateral Sensitivity: Some resistance mutations increase susceptibility to other antibiotics, creating opportunities for intelligent drug cycling protocols that steer pathogen evolution toward more susceptible genotypes.

Adaptive Reversions: Under certain selective pressures, previously selected resistance mutations can become deleterious and revert to wild-type, potentially restoring drug susceptibility [6].

These principles have informed the development of evolution-based treatment strategies that explicitly account for fitness landscape topography to delay resistance emergence and extend drug efficacy.

Protein Engineering and Synthetic Biology

In protein engineering, fitness landscape models guide the design of biomolecules with novel functions. Instead of purely random mutagenesis approaches, landscape-aware strategies leverage insights about GP map architecture:

Neutral Network Exploration: Directing evolution through neutral spaces allows sampling of diverse genotypes while maintaining function, increasing the probability of discovering new functional innovations.

Epistasis-Aware Design: Accounting for epistatic interactions prevents dead-end designs where beneficial individual mutations combine poorly.

Multi-functionality Engineering: The overlapping nature of genotype networks enables design of molecules with multiple specificities or conditional functions.

For synthetic biologists, understanding the architecture of empirical GP maps facilitates more predictable engineering of genetic circuits and metabolic pathways by anticipating how components will interact in novel genetic contexts [4].

Future Directions and Technical Challenges

Despite significant advances, several important challenges remain in fitness landscape research. Key frontier areas include:

High-Dimensional Visualization: Current visualization methods struggle with the high dimensionality of real biological genotype spaces. New computational approaches, such as eigenvector-based projections of evolutionary accessibility, are being developed to create more informative low-dimensional representations [2].

Environmental Robustness: Most empirical landscapes are characterized under fixed laboratory conditions. Understanding how landscapes transform across environmental gradients is essential for predicting evolution in natural settings.

Multi-scale Integration: Linking molecular-level fitness landscapes to organismal and population-level dynamics remains conceptually and technically challenging.

Timescale Dynamics: While the fitness seascape concept acknowledges environmental change, formalizing how landscapes evolve over different timescales—from ecological to evolutionary—requires new theoretical frameworks.

For researchers and drug development professionals, addressing these challenges will enable more accurate predictions of evolutionary trajectories and more sophisticated therapeutic interventions that explicitly account for evolutionary constraints and opportunities inherent in fitness landscape architecture.

As fitness landscape models continue to evolve from Wright's original metaphor to increasingly sophisticated empirical GP maps, they provide an indispensable framework for understanding and engineering evolutionary processes across biological systems.

Epistasis, the phenomenon where the effect of a genetic mutation depends on the presence or absence of other mutations, fundamentally shapes evolutionary trajectories and outcomes. This technical guide examines epistasis as a central force in molecular evolution, exploring its mechanisms through fitness landscape models, its role in compensatory evolution and drug resistance, and the experimental methods quantifying its effects. We synthesize recent research demonstrating how gene-gene interactions create historical contingency, constrain evolutionary paths, and foster emergent evolutionary phenomena. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these dynamics is critical for predicting resistance evolution and developing combination therapies that exploit genetic constraints.

Conceptual Foundations

- Fitness Landscape Definition: A fitness landscape represents the mapping between genotypes and their reproductive success, conceptualized as a topography where height corresponds to fitness. Peaks represent high-fitness genotypes, and valleys represent low-fitness genotypes.

- Epistasis as Landscape Ruggedness: Epistasis introduces nonlinearities into this mapping, creating correlations between genotypes that make landscapes "rugged" with multiple peaks and valleys rather than smooth, single-peaked surfaces.

- Evolutionary Consequences: Rugged landscapes constrain evolutionary paths, create historical contingency where evolutionary outcomes depend on the order of mutations, and can trap populations at local fitness optima rather than global optima.

Quantifying Epistatic Interactions

The table below summarizes the key quantitative measures used to characterize epistasis in evolutionary genetics:

Table 1: Quantitative Measures of Epistasis

| Measure | Calculation | Interpretation | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interaction Score (S) | ( S=\frac{v{obs}-v{exp}}{\sigma} ) | Quantifies deviation from expected phenotype under no interaction | Large-scale phenotypic data [7] |

| ε Score | ( ε = v{obs} - v{exp} ) | Raw phenotypic difference from expectation | Yeast genetic networks [7] |

| Fraction of Variation (φ) | ( φ=ρi^2-ρ{i-1}^2 ) | Proportion of fitness variance explained by epistatic order | Genotype-fitness maps [8] |

| Trajectory Similarity (θ) | 0.0 (identical) to 1.0 (non-overlapping) | Measures how epistasis alters evolutionary path probabilities | Pathway accessibility analysis [8] |

Theoretical Models of Epistasis in Evolutionary Dynamics

Tradeoff-Induced Landscape (TIL) Model

The TIL model provides a framework for understanding how universal antagonistic pleiotropy shapes evolutionary trajectories under stress conditions such as antimicrobial exposure [9].

Model Specifications:

- Genotype (σ): Binary vector representing L mutation sites

- Phenotypes: Null-fitness (rσ) and resistance level (mσ)

- Fitness function: ( fσ(x)=rσ/(1+(x/m_σ)^α) ) where x is stress level

- Assumption: All mutations exhibit antagonistic pleiotropy (increase resistance while decreasing null-fitness)

Key Findings:

- Biphasic Evolution: Initial adaptation rapidly accumulates resistance mutations with high fitness costs, followed by a slow phase of "exchange compensation" where high-cost mutations are replaced by low-cost alternatives

- Epistasis-Mediated Compensation: Compensation occurs without environmental change or reversion through epistatic interactions that alter selection pressures on resistance mutations

- Drug Resistance Implications: This mechanism explains persistence of resistant pathogens even after drug withdrawal and informs treatment strategies

High-Order Epistasis and Evolutionary Trajectories

Beyond pairwise interactions, high-order epistasis (interactions between three or more mutations) significantly influences evolutionary outcomes:

- Prevalence: High-order epistasis is statistically detectable across diverse biological systems, though typically with smaller magnitude than additive or pairwise effects [8]

- Trajectory Alteration: Computational removal of high-order epistasis from experimental genotype-fitness maps demonstrates its profound impact on evolutionary path probabilities and accessibility

- Unpredictability: High-order interactions make evolutionary trajectories fundamentally unpredictable from individual mutation effects alone, creating profound historical contingency

Table 2: Contributions of Different Epistatic Orders to Fitness Variation Across Experimental Datasets

| Dataset | Organism/System | Additive (%) | Pairwise Epistasis (%) | High-Order Epistasis (%) | Total Epistasis (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | E. coli genomic mutations | 94.0 | 3.8 | 2.2 | 6.0 |

| II | β-lactamase enzyme | 85.1 | 8.9 | 6.0 | 14.9 |

| IV | E. coli genomic mutations | 90.5 | 6.5 | 3.0 | 9.5 |

| VI | HIV envelope glycoprotein | 67.8 | 20.1 | 12.1 | 32.2 |

Epistasis in Regulatory Genetics and Diploid Systems

Biophysical Models of Regulatory Interactions

In diploid systems, regulatory interactions between transcription factors and cis-binding sites create complex epistatic networks with distinctive evolutionary dynamics:

- Thermodynamic Foundation: Molecular interactions follow biophysical principles where binding affinity depends on complementary shape and charge configurations

- Emergent Heterozygote Advantage: Modeled systems show broad ridges of heterozygote superiority in fitness landscapes, promoting stable polymorphisms without overdominant selection [10]

- Context-Dependent Dominance: Phenotypic dominance emerges from competitive binding between transcription-factor variants, varying with genetic background

Polymorphism Maintenance

Regulatory epistasis facilitates stable polymorphism maintenance through:

- Frequency-Dependent Selection: The fitness of regulatory genotypes depends on their frequency in populations

- Multi-locus Interactions: Epistatic interactions across multiple loci create balancing selection in heterogeneous environments

- Stable Equilibria: Broad regions of genotype space support protected polymorphisms where heterozygotes have higher fitness than corresponding homozygotes

Experimental Methodologies for Quantitative Epistasis Analysis

Multicellular Organism Protocol

Extending quantitative epistasis analysis to developmental traits in metazoans requires specialized methodologies:

- System: Caenorhabditis elegans model organism

- Gene Inactivation: RNA interference (RNAi) by feeding on mutant backgrounds for high-throughput dual-gene inactivation

- Phenotypic Scoring: Automated imaging systems for quantitative measurement of developmental phenotypes (body length, sex ratio)

- Quality Control: Flagging low-worm-count plates, assessing inter-replicate variation, removing irreproducible data points

Statistical Analysis and Genetic Interaction Scoring

- Fitness Normalization: Mutant values divided by wild-type values to obtain normalized fitness metrics

- Neutrality Models: Multiplicative model for fitness traits ((f{ab} = fa f_b) for non-interacting genes)

- Interaction Scoring:

- S-score adaptation for varying sample sizes: (S=\frac{v{obs}-v{exp}}{\sigma})

- Minimum bound placed on σ for small sample sizes to improve reproducibility

- Score interpretation: zero (no interaction), negative (aggravating), positive (alleviating)

Table 3: Experimental Reagents and Solutions for Quantitative Epistasis Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Specifications | Application | Function in Experimental Pipeline |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNAi Library | 114 clones for sex ratio, 109 for body length | Gene inactivation | High-throughput dual-gene knockdown in C. elegans |

| Mutant Strains | 36 sex ratio mutants, 31 body length mutants | Genetic background | Provide stable genetic context for RNAi testing |

| Automated Imaging System | Custom-developed platform | Phenotypic quantification | High-throughput measurement of body length and sex ratio |

| Statistical Pipeline | S-score with minimum bound | Data analysis | Detects genetic interactions from phenotypic data |

| Quality Control Metrics | Worm count thresholds, variation assessment | Data validation | Ensures reproducibility and flags synthetic lethality |

Workflow Visualization

Implications for Drug Resistance and Therapeutic Development

Exchange Compensation and Resistance Management

The epistasis-mediated exchange compensation mechanism has profound implications for antimicrobial resistance management:

- Persistence Prediction: Resistant strains can maintain resistance while reducing fitness costs without drug withdrawal, explaining persistent resistance in populations

- Treatment Strategies: Understanding this process informs drug cycling protocols and combination therapies that target compensatory pathways

- Evolution Forecasting: Models incorporating epistatic compensation improve predictions of resistance evolution in clinical settings

Research Reagent Solutions for Resistance Studies

Table 4: Essential Research Materials for Epistasis Studies in Drug Resistance

| Material/Resource | Specifications | Research Application | Key Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Combinatorial Mutant Libraries | All binary combinations of 5 mutations (32 genotypes) | Landscape mapping | Enables complete epistasis measurement across genotype space |

| Dose-Response Assay Systems | Hill-type response curves with variable stress levels | Phenotypic characterization | Quantifies fitness across environmental gradients |

| High-Throughput Sequencing | Whole-genome variant calling | Genotype monitoring | Tracks mutation dynamics during experimental evolution |

| Bioinformatics Pipelines | Walsh polynomial decomposition | Epistasis quantification | Partitions fitness variation into additive and epistatic components |

| Evolutionary Simulation Platforms | Wright-Fisher with SSWM assumptions | Theoretical modeling | Predicts evolutionary trajectories on empirical fitness landscapes |

Epistasis stands as a central determinant of evolutionary dynamics, transforming our understanding of adaptation, compensation, and resistance evolution. Through fitness landscape models, we observe how gene-gene interactions create evolutionary contingency, constrain trajectories, and generate emergent properties like heterozygote advantage and cost-free resistance maintenance. For researchers and drug development professionals, incorporating epistatic principles into experimental design and therapeutic strategy is no longer optional but essential for predicting evolutionary outcomes and designing effective interventions. The methodologies and frameworks presented here provide the technical foundation for advancing these applications across evolutionary biology, genomics, and clinical medicine.

Epistasis, or gene-gene interaction, fundamentally shapes evolutionary trajectories by influencing how mutations combine to affect fitness. In recent decades, research has revealed two seemingly contradictory patterns of epistasis. On one hand, idiosyncratic epistasis refers to highly specific, context-dependent interactions between particular mutations that create profound historical contingency, tightly constraining the paths available to natural selection [11]. On the other hand, global epistasis describes seemingly non-specific, systematic patterns where the fitness effect of a mutation varies predictably with the background fitness of the organism, typically manifesting as diminishing-returns for beneficial mutations and increasing-costs for deleterious mutations [12]. This technical guide examines the relationship between these phenomena, synthesizing recent advances that demonstrate how widespread idiosyncratic interactions can generate the consistent patterns observed in global epistasis, with significant implications for evolutionary predictability and therapeutic intervention.

Core Concepts: Defining the Spectrum of Epistatic Interactions

Idiosyncratic Epistasis: The Specificity of Genetic Context

Idiosyncratic epistasis arises from specific biological and physical interactions between particular mutations. These interactions reflect the unique molecular details of the mutations involved and can occur at various orders—from pairwise interactions to complex higher-order interactions involving multiple mutations [11]. The presence of extensive idiosyncratic epistasis suggests that evolutionary outcomes may be highly contingent on the specific historical sequence of mutations, potentially limiting repeatability and predictability. Studies of complete fitness landscapes at the scale of individual proteins or pathways have typically revealed this type of complex, specific interaction, highlighting the potential for epistasis to create evolutionary path dependence [11].

Global Epistasis: Systematic Patterns Across the Genome

Global epistasis describes consistent patterns observed across diverse genetic backgrounds, where mutations systematically become less beneficial (diminishing-returns) or more deleterious (increasing-costs) as background fitness increases [12]. This phenomenon is characterized by a approximately linear relationship between background fitness and mutational effects, which can be formalized as:

si = sadditive,i + sgenotype,i - ciy [12]

Where si represents the fitness effect of a mutation at locus i, sadditive,i is its additive effect, sgenotype,i captures genotype-dependent idiosyncratic epistasis, ci quantifies the strength of global epistasis for that locus, and y is the background fitness. This consistent pattern has been observed in microbial evolution experiments where parallel populations show remarkably similar fitness trajectories despite accumulating different mutations [12].

Theoretical Integration: How Idiosyncrasy Generates Global Patterns

Recent theoretical work demonstrates that global epistasis can emerge generically as a consequence of widespread idiosyncratic epistasis. When a mutation affects many independent epistatic interactions across the genome, the cumulative effect can manifest as a systematic dependence on background fitness [11] [12]. This occurs because adaptation selects for genotypes with a bias toward positive interactions. When a mutation occurs in such an adapted background, it is statistically more likely to disrupt these beneficial arrangements, leading to the characteristic diminishing-returns pattern [12]. This provides a unifying framework where apparent global patterns ultimately originate from numerous specific interactions, resolving the apparent contradiction between the two descriptions of epistasis.

Experimental Methodologies: Mapping Complex Fitness Landscapes

Hierarchical CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Drive System

A groundbreaking experimental approach for constructing complete fitness landscapes employs a hierarchical CRISPR-Cas9 gene drive system in Saccharomyces cerevisiae that enables combinatorial genome editing across multiple loci [11]. This method allows researchers to systematically assemble and analyze all possible combinations of target mutations through an iterative process:

- Strain Preparation: Haploid strains of opposite mating type containing inducible Cre recombinase and SpCas9 genes are mutated at specific loci, with guide RNAs (gRNAs) targeting wild-type alleles integrated into their genomes [11].

- Diploid Formation and Gene Drive: Strains are mated to form diploids heterozygous at target loci, followed by induced expression of Cas9 and gRNAs to create double-strand breaks at wild-type alleles. These breaks are repaired using mutated homologous chromosomes, making the diploid homozygous with >95% efficiency [11].

- gRNA Recombination: Simultaneous Cre expression induces recombination between Lox sites, physically linking gRNAs on the same chromosome [11].

- Library Generation: Sporulation produces haploid progeny with linked gRNAs, enabling iterative cycles that exponentially expand genotype libraries—from 2 to 4 loci, then to 8, and ultimately to 16 loci (65,536 genotypes) in just four cycles [11].

Table 1: Key Components of Hierarchical CRISPR Gene Drive System

| Component | Type/Function | Experimental Role |

|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 | CRISPR-associated nuclease | Creates double-strand breaks at wild-type alleles |

| Cre recombinase | Site-specific recombinase | Induces recombination between Lox sites to link gRNAs |

| Guide RNAs (gRNAs) | Targeting RNAs | Direct Cas9 to specific genomic loci |

| Lox sites | Recognition sequences for Cre recombinase | Flank gRNA arrays to enable physical linking |

| Pseudo-WT loci | Synonymous variants | Control for gRNA recognition without amino acid changes |

Landscape Construction and Fitness Measurement

In a landmark study, this system was used to construct a near-complete fitness landscape spanning 10 missense mutations in 10 genes across 8 chromosomes in yeast, sampling diverse cellular functions including membrane stress response, mitochondrial stability, and nutrient sensing [11]. Key steps included:

- Mutation Selection: Identified mutations from studies of natural variation and experimental evolution to maximize fitness variance while minimizing pathway-specific idiosyncratic interactions [11].

- Barcode Integration: Before the final mating cycle, all strains were transformed with unique DNA barcodes near the LYS2 locus to enable high-throughput fitness measurements via sequencing [11].

- Genotype Validation: All strains were genotyped at all 10 loci, with 875 of 1024 (85.4%) possible genotypes represented in the final library [11].

- Fitness Assays: Conducted replicate bulk barcode sequencing fitness assays in haploid and homozygous diploid versions across six stressful environments, tracking relative fitness from changes in barcode frequencies over 49 generations [11].

Data Analysis and Epistasis Quantification

Fitness data were analyzed using LASSO regularization to infer background-averaged additive and epistatic effects for each mutation and combination of mutations [11]. This statistical approach helps manage the high dimensionality of the parameter space in complete fitness landscapes, distinguishing idiosyncratic interactions from systematic global patterns.

Diagram 1: CRISPR Gene Drive Workflow (62 characters)

Quantitative Findings: From Specific Interactions to Global Patterns

Environmental Dependence of Epistatic Networks

Analysis of the 10-mutation fitness landscape across six environments revealed substantial environmental influence on epistatic interactions [11]. The correlation of genotype fitnesses, additive effects of individual mutations, and pairwise interactions between mutations all varied considerably across conditions, demonstrating that epistasis is highly sensitive to environmental context [11]. While some pairwise interactions remained relatively constant as additive effects changed, most exhibited considerable variation across environments, indicating that both the magnitude and sign of epistatic interactions can be environmentally dependent [11].

Table 2: Environmental Conditions in Fitness Landscape Analysis

| Environment | Stress Condition | Key Observations |

|---|---|---|

| YPD + 0.4% acetic acid | Membrane stress | Distinct epistatic patterns compared to other conditions |

| YPD + 6 mM guanidium chloride | Protein folding stress | Environment-specific interaction networks |

| YPD + 35 μM suloctidil | Membrane composition stress | Notable differences between haploid/diploid fitness landscapes |

| YPD @ 37°C | Thermal stress | Consistent diminishing-returns pattern across genotypes |

| YPD + 0.8 M NaCl | Osmotic stress | Systematic global epistasis emerging from idiosyncratic interactions |

| SD + 10 ng/mL 4NQO | DNA damage stress | Distinct pattern of increasing-costs for deleterious mutations |

Mathematical Framework for Global Epistasis Emergence

The emergence of global epistasis from widespread idiosyncratic interactions can be formally described using fitness landscape models. In this framework, fitness (y) is mapped to a biallelic genotype (xi = ±1) through a generalized mathematical expression:

Where y¯ is the average fitness, the fᵢ terms represent additive effects, and the higher-order terms capture epistatic interactions [12]. When a locus interacts with many independent partners, the fitness effect of mutating that locus can be shown to follow the relationship:

Where the first term represents the additive component, the second term captures global epistasis linearly dependent on background fitness, and the third term represents residual genotype-specific idiosyncratic epistasis [12]. The parameter v~ᵢ quantifies the strength of global epistasis for each locus and is determined by the structure of its epistatic interactions across the genome [12].

Diagram 2: Global Pattern Emergence (67 characters)

Compensatory Evolution: Epistasis in Therapeutic Contexts

Exchange Compensation in Resistance Evolution

Epistasis plays a crucial role in compensatory evolution, particularly in the context of drug resistance. A tradeoff-induced landscape (TIL) model demonstrates how exchange compensation enables recovery of null-fitness without losing resistance benefits [9]. This model incorporates universal antagonistic pleiotropy, where every resistance-increasing mutation reduces null-fitness (fitness in the absence of stress), formalized as:

Where rσ is the null-fitness, mσ is the resistance level, x is drug concentration, and α is the Hill coefficient [9]. Evolution in this landscape occurs in two phases: an initial rapid gain in resistance accompanied by null-fitness loss, followed by a slower phase where high-cost resistance mutations are replaced by low-cost alternatives through epistatic interactions, partially restoring null-fitness without compromising resistance [9].

Implications for Antibiotic Treatment Strategies

The epistasis-mediated compensation mechanism has direct implications for drug development and treatment strategies. Traditional views suggest that compensation requires either reversion to the sensitive genotype or secondary-site compensatory mutations [9]. However, the exchange compensation model demonstrates that resistance costs can be reduced even while maintaining constant drug pressure, through the epistasis-guided substitution of resistance mutations [9]. This suggests that long-term treatment may naturally select for resistant strains with minimal fitness costs, potentially explaining the persistence of resistant pathogens in clinical settings.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Epistasis Research

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Epistasis Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Hierarchical CRISPR-Cas9 | Combinatorial genome editing | Construction of complete fitness landscapes [11] |

| Cre-Lox recombination system | Site-specific recombination | Physical linking of gRNA arrays [11] |

| DNA barcoding system | High-throughput fitness tracking | Competitive fitness assays in pooled libraries [11] |

| EINVis software | Epistatic interaction visualization | Network analysis of genetic interactions [13] |

| Tradeoff-Induced Landscape (TIL) model | Theoretical modeling | Studying resistance/compensatory evolution [9] |

| Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) | DNA sequence data analysis | Processing next-generation sequencing data [14] |

The synthesis of global and idiosyncratic epistasis represents a significant advance in evolutionary genetics, demonstrating how consistent patterns emerge from specific interactions. This integrated perspective has profound implications for predicting evolutionary trajectories, understanding constraints on adaptation, and developing therapeutic strategies against evolving pathogens. The experimental and computational methodologies reviewed here provide researchers with powerful tools to dissect these complex genetic interactions across diverse biological systems and environmental contexts. As these approaches continue to develop, they promise to enhance our ability to forecast evolutionary outcomes and design effective interventions against evolving threats in medicine and biotechnology.

In evolutionary biology, a fitness landscape is a conceptual map that connects genotypes to their reproductive success. The shape of this landscape is fundamentally sculpted by epistasis—the phenomenon where the effect of one mutation depends on the presence of other mutations in the genome. For years, research has revealed that epistatic interactions add substantial complexity to genotype-phenotype maps, making evolutionary trajectories difficult to predict. However, a significant simplification emerged with the discovery of global epistasis, where the fitness effect of a mutation often correlates with the fitness of its genetic background in a surprisingly linear relationship [15]. This regular pattern has allowed researchers to reconstruct fitness landscapes and infer adaptive paths.

Despite these advances, a critical factor has been frequently overlooked: the environment. Environmental variation is a major driver of evolution, yet its capacity to modulate patterns of epistasis has received little attention. This is particularly relevant for antimicrobial resistance (AMR) evolution, where drug concentrations create a dynamic environment that can shape adaptive trajectories in unpredictable ways [15]. This whitepaper synthesizes recent findings to demonstrate how drug concentration acts as a powerful environmental modulator of global epistasis, reshaping the fitness landscape and altering evolutionary predictions.

Core Concepts: From Global Epistasis to Environmental Modulation

Quantifying Epistasis in a Fitness Landscape

To understand environmental modulation, one must first grasp how epistasis is measured. In a given fitness landscape, the fitness effect of a focal mutation (i) is calculated as:

Δfi = f(B+i) - f(B)

where f(B) is the fitness of the genetic background without the mutation, and f(B+*i*) is the fitness of the same background with the mutation added [15].

The strength of epistasis for that mutation is quantified as the variance of its fitness effects across different genetic backgrounds, relative to the variance in background fitness itself: var(Δfi) / var(f(B)) [15]. A high value indicates that the mutation's effect is highly dependent on its genetic context.

Epistasis is considered "global" when this variable fitness effect, Δfi, is strongly correlated with the background fitness, f(B). The degree to which epistasis is global is quantified by the coefficient of determination (R²) of a linear regression between these two variables [15].

The P. falciparum DHFR Drug Resistance Landscape

A compelling model system for studying environmental modulation is the evolution of drug resistance in the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. A key study analyzed a fitness landscape of four mutations (C59R, I164L, N51I, S108N) in the gene encoding the dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) enzyme, a target of antifolate drugs like pyrimethamine [15]. These mutations are associated with resistance across the globe.

In this system, researchers quantified the growth rates of 15 different parasite genotypes across a gradient of pyrimethamine concentrations (from 0 to 10³ μM). The observed epistatic interactions were complex; at high drug concentrations, the quadruple mutant had lower fitness than expected from the sum of individual mutation effects, whereas in a drug-free environment, epistasis reduced the deleteriousness of the combined mutations [15]. This suggested that drug dose was a critical variable determining the landscape's topography.

Quantitative Evidence: Drug Concentration Reshapes Epistatic Patterns

The analysis of the DHFR landscape revealed that drug concentration profoundly modulates both the strength and shape of global epistasis for individual mutations.

Table 1: Modulation of Global Epistasis for DHFR Mutations by Pyrimethamine Concentration

| Mutation | Low Drug Concentration | High Drug Concentration | Key Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| C59R | Diminishing returns epistasis (negative slope) | Increasing returns epistasis (positive slope) | Slope of global epistasis relationship reverses |

| S108N | More predictable (global) epistasis (R² ~0.2) | Highly idiosyncratic epistasis (lower R²) | Epistasis becomes less predictable from background |

| N51I | Strong epistasis (var ratio ~1) | Weaker epistasis (lower var ratio) | Dependency on genetic background decreases |

| I164L | --- | --- | Epistasis strength constant; becomes more global (higher R²) |

As illustrated in Table 1, mutation C59R undergoes a dramatic shift. At low drug doses, it exhibits a pattern of diminishing returns—its beneficial effect is smaller in fitter genetic backgrounds. At high doses, this flips to increasing returns—the mutation has a larger beneficial effect in fitter backgrounds [15]. Other mutations show different modulation patterns; for instance, epistasis for S108N becomes more idiosyncratic with increasing drug concentration, while for I164L it becomes more globally predictable [15].

Table 2: Key Quantitative Metrics for Epistasis Analysis in the DHFR Study

| Metric | Formula/Description | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Fitness (f) | Relative growth rate measured experimentally | Determines selection pressure on a genotype. |

| Fitness Effect (Δf) | Δf = f(B+i) - f(B) | Measured effect of adding a specific mutation. |

| Strength of Epistasis | var(Δfi) / var(f(B)) | Values near 1 indicate strong background-dependency. |

| Linearity (Global-ness) | R² of Δf ~ f(B) regression | High R² (>0.7) indicates epistasis is largely global. |

This environmental modulation means that a mutation's evolutionary fate—whether it is favored or disfavored by natural selection—cannot be assessed in isolation. It depends on both the genetic background in which it arises and the drug concentration in the environment.

Mechanistic Insights: Connecting Environment to Gene Interactions

The modulation of global epistasis by drug concentration is not a mysterious black box. It can be traced back to how the environment alters specific gene-by-gene interactions. The research on the DHFR landscape suggests that this modulation can be quantitatively explained by how specific gene-by-gene interactions are modified by drug dose [15].

Extending theoretical work, the study posits that the distribution of these fine-grained, environment-dependent genetic interactions determines the emergent strength and shape of global epistasis across different drug doses. In essence, the drug environment changes the underlying biochemical constraints, which in turn alters how mutations interact with each other, finally manifesting as a shift in the global epistasis pattern [15]. This provides a mechanistic bridge connecting environmental change to the topography of the fitness landscape.

Experimental Protocols for Studying Environmental Modulation

Constructing a Genotype Panel and Fitness Assay

1. Genotype Selection: Select a set of mutations known to be involved in the trait of interest (e.g., drug resistance). Genetically engineer a combinatorial set of all possible variants. The DHFR study used 15 genotypes covering all combinations of 4 mutations [15].

2. Environmental Gradient Setup: Establish a range of relevant environmental conditions. For drug studies, this involves creating a concentration gradient. The protocol should include a no-drug control and a series of concentrations (e.g., from 10⁻² μM to 10³ μM for pyrimethamine) to capture a wide range of selective pressures [15].

3. High-Precision Fitness Measurement: Culture each genotype in triplicate across all environmental conditions. Fitness is quantified as the growth rate relative to a reference genotype (e.g., the slowest-growing genotype in the absence of the drug). Use high-throughput methods to ensure accuracy and reproducibility [15].

Quantifying Epistasis and Global Patterns

1. Calculate Fitness Effects: For each mutation i and each genetic background B in the panel, compute the fitness effect Δfi = f(B+i) - f(B). Perform this calculation for every environmental condition [15].

2. Analyze Epistasis Strength and Linearity:

- For each mutation and environment, calculate the strength of epistasis as var(Δfi) / var(f(B)).

- Perform a linear regression of Δfi against f(B) for each mutation in each environment to obtain the R² value, which indicates the "global-ness" of epistasis [15].

3. Model Modulation: Statistically compare the slopes of the global epistasis relationships and the variance ratios across different environmental conditions to identify significant modulation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Epistasis-Environment Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Example from DHFR Study |

|---|---|---|

| Combinatorial Mutant Library | Enables measurement of mutation effects across diverse genetic backgrounds. | 15 genotypes of P. falciparum with combinations of 4 DHFR mutations [15]. |

| Environmental Modulator | Creates the selective pressure gradient to test genotype-by-environment interactions. | Pyrimethamine or cycloguanil drug concentration gradient (10⁻² to 10³ μM) [15]. |

| High-Precision Growth Assay | Quantifies fitness (relative growth rate) of each genotype in each condition. | Culturing system and metric for parasite growth rate relative to a reference strain [15]. |

| The "Guilt-by-Association" Principle | Computational principle assuming similar drugs interact with similar proteins; used in network-based DTI prediction [16]. | (Used in related DTI prediction models like GLDPI for inferring unknown interactions from network topology [16]). |

| Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) | Machine learning technique to address class imbalance; generates synthetic minority class data. | (Used in related ML-based Drug-Target Interaction prediction to balance datasets and reduce false negatives [17]). |

Visualizing the Mechanistic Link

The following diagram synthesizes the proposed mechanism by which drug concentration alters the patterns of epistasis, from the environmental trigger to the resulting evolutionary consequences.

Implications and Future Directions

The evidence that drug concentration can reshape global epistasis has profound implications. For evolutionary theory, it underscores that fitness landscapes are not static but are fluid entities that change with the environment. For the predictability of evolution, particularly in the critical context of antimicrobial resistance, it highlights a sobering limitation: trajectories inferred in one environment may not hold in another [15]. This complexity necessitates a new generation of models that explicitly incorporate environmental variation into the global epistasis framework.

Future research should focus on elucidating the precise structural and biochemical mechanisms that link drug concentration to changes in specific genetic interactions. Furthermore, integrating these findings with machine learning approaches, such as the epistatic transformer used to model higher-order epistasis in proteins [18], could yield powerful predictive models. The ultimate goal is to forecast the evolution of drug resistance with greater accuracy, enabling the development of smarter drug deployment strategies and novel therapeutic interventions that anticipate and counter evolutionary escape paths.

Adaptive evolution is fundamentally a search process across a fitness landscape, a conceptual framework mapping genotypes to reproductive success. Within these landscapes, epistatic interactions (non-additive effects between mutations) create evolutionary topography characterized by varying degrees of ruggedness. Highly rugged landscapes contain numerous local fitness peaks separated by valleys of lower fitness, potentially constraining evolutionary paths and outcomes. Understanding these constraints is crucial for predicting evolutionary trajectories in diverse fields, including antimicrobial resistance, cancer progression, and protein engineering. This technical guide examines the relationship between landscape ruggedness, peak accessibility, and evolutionary constraints through recent empirical findings and methodological advances, providing researchers with both theoretical frameworks and practical experimental approaches.

Empirical Evidence of Rugged yet Navigable Landscapes

The Highly Rugged Regulatory Landscape of TetR

A groundbreaking 2024 study mapping the regulatory landscape of the bacterial transcription factor TetR provides unprecedented empirical insight into realistic landscape topography. Researchers employed an in vivo massively parallel reporter assay to quantify repression strength for 17,765 transcription factor binding site (TFBS) variants, creating a comprehensive fitness landscape for this prokaryotic gene regulator [19].

Key findings revealed a strikingly rugged landscape with 2,092 distinct peaks of strong transcriptional repression, yet only a minority provided stronger repression than the wild-type sequence. The landscape exhibited widespread epistatic interactions between mutations, where the fitness effect of one mutation depended on genetic background. Despite this extreme ruggedness—characteristics traditionally expected to constrain adaptation—evolutionary simulations demonstrated surprising navigability: approximately 20% of evolving populations reached high peaks, which possessed large basins of attraction (genotypes from which adaptive walks converge to a particular peak) [19].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of the TetR Regulatory Landscape [19]

| Landscape Feature | Measurement | Evolutionary Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Total peaks identified | 2,092 peaks | High ruggedness with many local optima |

| Peaks stronger than wild-type | Few peaks | Global optimum difficult to identify |

| Epistatic interactions | Frequent | Non-additive effects create rugged topography |

| Populations reaching high peaks | ~20% | Substantial navigability despite ruggedness |

| Peak fitness-basin size correlation | Positive | Higher peaks tend to have larger attraction basins |

| Evolutionary predictability | Low | Outcome contingent on mutational path |

Comparative Landscape Analyses

Research across diverse biological systems reveals substantial variation in landscape navigability. A 2025 analysis examining the probability of reaching high peaks (PHP) by adaptive walks across multiple empirical and theoretical landscapes found that PHP varies significantly among systems [20]. In every landscape examined, a positive correlation existed between a peak's fitness and the size of its basin of attraction. However, this correlation alone does not guarantee high navigability, as other factors including the distribution and interconnectedness of peaks significantly influence evolutionary outcomes [20].

Notably, PHP in empirical landscapes was generally comparable to or smaller than that in same-size Rough Mount Fuji landscapes of similar ruggedness. The Rough Mount Fuji model represents an intermediate topography between perfectly additive (smooth) and completely random (maximally rugged) landscapes. These findings indicate that lowering landscape ruggedness consistently boosts PHP, confirming a fundamental relationship between landscape topography and evolutionary constraint [20].

Methodologies for Fitness Landscape Mapping

Sort-Seq for High-Throughput Regulatory Phenotyping

The TetR study employed a sophisticated sort-seq pipeline to quantify the functional effects of thousands of genetic variants in vivo. The following diagram illustrates the core workflow:

Figure 1: Workflow for mapping regulatory fitness landscapes using sort-seq.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Library Generation: Randomize eight critical base-pair positions in the tetO2 binding site, creating a theoretical library of 65,536 (4^8) unique TFBS variants [19].

Plasmid Engineering: Clone variants into a reporter plasmid where TFBS sequence controls transcription of a GFP reporter gene. Strong TetR binding represses GFP expression, creating a quantitative link between binding affinity and fluorescence [19].

Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS):

- Transform library into Escherichia coli expressing TetR

- Grow cells without inducer to maintain repression

- Sort cell populations into 13 bins based on GFP fluorescence intensity

- Include controls: wild-type TFBS (high repression) and promoter-less vector (background fluorescence) [19]

Deep Sequencing: Isolate plasmids from each bin and perform high-throughput sequencing to determine variant abundance in each fluorescence bin [19].

Repression Strength Calculation: Use bin distributions to compute repression strength for each variant, normalized to wild-type repression. Apply stringent quality filters (minimum 30 sequencing reads per variant) [19].

Validation and Quality Control

- Technical replicates show high reproducibility (Pearson's R = 0.971-0.991) [19]

- Plate reader assays validate sort-seq repression measurements for selected variants [19]

- Inducer controls confirm TetR-specific effects (derepression with anhydrotetracycline) [19]

Bayesian Inference from Phylogenetic Trees

For systems where comprehensive variant libraries are impractical, tree-structured branching processes enable fitness landscape inference from evolutionary histories. The FiTree method applies a Bayesian framework to single-cell tumor mutation trees, inferring fitness effects and epistatic interactions from cancer phylogenetic data [21].

Table 2: Computational Methods for Fitness Landscape Inference

| Method | Application Context | Key Features | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sort-seq & MPRAs | Regulatory sequences, proteins | Direct functional measurement, high precision | Limited to tractable sequence spaces |

| FiTree | Tumor evolution, microbial populations | Leverages natural evolutionary histories, accounts for epistasis | Requires high-resolution phylogenetic trees |

| ALEsim | Laboratory evolution experiments | Optimizes ALE experimental design | Based on simulation rather than direct measurement |

Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE) Experiments

Adaptive Laboratory Evolution provides an experimental framework to observe evolution in real-time under defined conditions. ALE involves serial passaging of microbial populations, promoting accumulation of beneficial mutations that can be characterized through genomic analysis [22] [23].

The ALEsim simulator optimizes key parameters:

- Passage size: Affects efficiency of beneficial mutation fixation

- Mutation rate: Estimated at 10^(-6.9) to 10^(-8.4) beneficial mutations per cell division for E. coli [23]

- Experimental duration: Determined by fitness convergence rather than fixed timepoints

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Fitness Landscape Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| TetR repressor system | Model prokaryotic regulatory system | Mapping TFBS fitness landscapes [19] |

| Fluorescent reporter genes (e.g., GFP) | Quantitative phenotypic readout | Sort-seq repression measurements [19] |

| Barcoded variant libraries | Tracking genotype frequencies | Massive parallel functional assays [19] |

| Flow cytometer with sorter | Physical separation by fluorescence | FACS binning for sort-seq [19] |

| High-throughput sequencer | Variant identification and quantification | Deep sequencing of sorted populations [19] |

| ALEsim simulator | Optimizing evolution experiments | Designing efficient ALE protocols [23] |

| FiTree package | Bayesian fitness inference | Analyzing tumor mutation trees [21] |

Implications for Evolutionary Prediction and Intervention

The empirical finding that highly rugged landscapes can remain navigable has profound implications for evolutionary forecasting in biological applications. The accessibility of high peaks despite extensive epistasis suggests that evolutionary constraints may be less severe than traditionally predicted by theoretical models of maximally rugged landscapes [19] [20].

Therapeutic Applications

In cancer evolution, methods like FiTree that infer fitness landscapes from tumor phylogenies can identify likely evolutionary trajectories and predict resistance mutations. The Bayesian framework quantifies uncertainty in future mutational events, potentially informing therapeutic strategies that anticipate or constrain evolutionary paths [21].

In antimicrobial resistance, understanding the ruggedness of landscapes for drug target genes can help predict the accessibility of resistance mutations and design combination therapies that create evolutionary valleys between resistant genotypes.

Protein and Metabolic Engineering

The navigability of rugged landscapes supports directed evolution approaches for engineering novel enzyme functions or metabolic pathways. Even with epistatic constraints, sufficient evolutionary exploration can discover high-fitness solutions, especially when employing recombination to jump between adaptive peaks.

The synthesis of recent empirical evidence reveals that biological fitness landscapes, while often highly rugged due to pervasive epistasis, frequently maintain evolutionary navigability through structural features including correlated fitness networks and expanded basins of attraction surrounding high peaks. This resolved paradox—rugged yet navigable landscapes—emerges from the non-random structure of biological genotype-phenotype maps, where historical contingencies and mutational paths shape outcomes without deterministically fixing them.

For researchers investigating evolutionary constraints across biological domains, from antibiotic resistance to cancer progression, these findings emphasize that predicting evolutionary trajectories requires empirical landscape mapping rather than relying solely on theoretical models. The methodologies detailed herein—from high-throughput functional assays to phylogenetic inference—provide a toolkit for quantifying ruggedness and peak accessibility in specific systems of interest, ultimately enhancing our ability to forecast and potentially direct evolutionary processes.

From Sequence to Function: Mapping and Leveraging Landscapes in Biomedicine

High-throughput sequencing (HTS) has revolutionized the study of molecular evolution by enabling the detailed experimental characterization of fitness landscapes. The ability to sequence hundreds of thousands of variants in parallel provides the quantitative data necessary to understand how protein sequences map to functional outputs, revealing the complex epistatic interactions that shape evolutionary trajectories. Current sequencing technologies offer unprecedented accuracy, with some platforms now achieving Q40 standards (equivalent to one error in 10,000 bases), enabling more precise mapping of functional sequences in in vitro selection experiments [24]. This technical guide provides a comprehensive framework for employing HTS in delineating fitness landscapes, with particular emphasis on practical methodologies for researchers investigating epistasis and molecular evolution.

High-Throughput Sequencing Technology Landscape

The selection of appropriate sequencing technology is fundamental to experimental design for fitness landscape studies. The market offers diverse platforms with complementary strengths for different aspects of in vitro selection analysis.

Table 1: Sequencing Platforms and Their Applications in Fitness Landscape Studies

| Platform Type | Key Platforms | Accuracy | Read Length | Applications in Fitness Landscapes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short-Read (NGS) | Illumina NovaSeqX, Element AVITI, PacBio Onso | Q30-Q40 (1 error/1,000-10,000 bases) | Short (bp) | Deep mutational scanning, variant enumeration, enrichment calculations |

| Long-Read | PacBio Revio, Oxford Nanopore | Q28-Q30 | Long (kb+) | Full-length aptamer/peptide sequencing, structural variant detection |

| Emerging/Long-read Kits | Illumina Complete Long Reads, Element LoopSeq | Varies | 5-10kb | Hybrid approaches for longer constructs |

Recent advancements have significantly improved sequencing accuracy, with platforms like Element Biosciences' AVITI and PacBio's Onso now routinely achieving Q40 (99.99% accuracy) [24]. This enhanced accuracy is particularly valuable for detecting rare variants in deep mutational scanning experiments and for precisely quantifying sequence enrichment across selection rounds. For studies focusing on DNA-binding domains or larger peptide constructs, long-read technologies and specialized kits that generate long-read information from short-read platforms offer valuable alternatives for obtaining complete sequence information [24].

Bioinformatics Pipelines for HTS Data Analysis

Specialized bioinformatics tools are essential for processing the massive datasets generated by HTS experiments in in vitro selection. These pipelines transform raw sequencing data into quantitative fitness metrics.

EasyDIVER+ for In Vitro Evolution Data

EasyDIVER+ represents an advanced analytical pipeline specifically designed for HTS data from in vitro evolution of nucleic acids or amino acids [25]. This enhanced tool builds upon the original EasyDIVER pre-processing capabilities and introduces critical analytical features for fitness landscape studies:

- Processing of Raw Sequencing Data: Accepts paired-end, demultiplexed Illumina read files as input

- Enrichment Calculations: Computes enrichment values for each unique sequence across consecutive selection rounds

- Visualization Platform: Provides customizable graphical representations of sequence metrics

- Peptide Data Specialization: Offers specific functionality for analyzing mRNA display selections, addressing a significant gap in earlier tools [25]

The pipeline enables researchers to track the evolutionary trajectory of individual sequences through multiple rounds of selection, providing the quantitative data necessary for constructing empirical fitness landscapes.

Benchmarking in Bioinformatics

The exponential growth of computational methods for single-cell and HTS data analysis has highlighted the importance of rigorous benchmarking. Recent assessments have evaluated 282 papers, including 130 benchmark-only papers, to establish standards for methodological evaluations in the field [26]. This benchmarking landscape provides valuable guidance for selecting appropriate analytical tools for fitness landscape studies, with emerging best practices focusing on dataset diversity, method robustness, and downstream evaluation metrics.

Experimental Methodologies for Fitness Landscape Mapping

Comprehensive fitness landscape mapping requires sophisticated experimental designs that combine ancestral sequence reconstruction with deep mutational scanning.

Phylogenetic Tree Synthesis and Characterization

The LacI/GalR transcriptional repressor family study provides a powerful example of experimental fitness landscape delineation [27]. This approach synthesized and characterized 1,158 extant and ancestral DNA-binding domains (DBDs) through the following methodology:

Phylogenetic Inference: Reconstruction of 577 ancestral sequences from 581 extant LacI homologs with mean posterior probability of 93%, indicating strong statistical support [27]

Library Construction: Chip-based oligonucleotide synthesis of DBD sequences cloned into plasmid libraries encoding chimeric variants with an invariant ligand-binding domain from EcLacI

Functional Characterization: Measurement of affinity for E. coli lac operator sequence across all 1,158 DBDs

Deep Sequencing Verification: Confirmation of complete library coverage with minimal skew through deep sequencing of the plasmid library

This experimental design enabled comprehensive mapping of sequence-function relationships across evolutionary timescales, revealing an extremely rugged fitness landscape with high levels of epistasis [27].

Deep Mutational Scanning (DMS) Protocol

DMS provides complementary data on local fitness landscapes around specific sequences. The core protocol involves:

Library Generation: Creating a diverse variant library through error-prone PCR or oligonucleotide synthesis

Functional Selection: Applying selective pressure (e.g., binding to target, enzymatic activity)

HTS Quantification: Sequencing pre- and post-selection populations to quantify enrichment

Fitness Calculation: Determining fitness scores based on frequency changes

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Fitness Landscape Experiments

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Oligonucleotide Chip Synthesis | Parallel synthesis of variant libraries | Generating 1,158 DBD variants for LacI/GalR study [27] |

| mRNA Display Platforms | In vitro selection of peptides | High-throughput sequencing of peptide selections [25] |

| Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction Algorithms | Computational inference of ancestral proteins | Generating phylogenetic trees for experimental characterization [27] |

| EasyDIVER+ Pipeline | Analysis of HTS data from in vitro evolution | Calculating enrichment values across selection rounds [25] |

Case Study: Rugged Fitness Landscapes in LacI/GalR Evolution

The comprehensive analysis of the LacI/GalR family illustrates the power of HTS approaches for revealing fundamental principles of molecular evolution. The experimental characterization of 1,158 DBDs revealed:

- Extreme Ruggedness: Most sequences showed no affinity for the E. coli lac operator, with functional repressors separated by extensive valleys of non-functional sequences [27]

- High Epistasis: Up to 32/60 amino acid substitutions in functional DBDs compared to EcLacI DBD, indicating strong context-dependence of mutational effects [27]

- Rapid Specificity Switching: Gain/loss of function between adjacent phylogenetic nodes, suggesting quick evolutionary transitions in DNA specificity [27]

The molecular basis for this ruggedness appears to stem from the necessity for regulators to simultaneously evolve specificity for asymmetric operator half-sites while minimizing detrimental regulatory crosstalk [27]. This contrasts with the smoother fitness landscapes observed in many enzyme evolution studies, where promiscuous activities can be gradually optimized.

Rugged Fitness Landscape with Epistasis

Workflow: Integrated HTS and In Vitro Selection

The complete workflow for fitness landscape delineation combines experimental selection with comprehensive sequencing and computational analysis.

HTS Fitness Landscape Workflow

Data Visualization and Accessibility in Scientific Communication

Effective visualization of fitness landscape data requires careful attention to accessibility principles to ensure clear communication of complex relationships:

- Color Contrast: Maintain minimum 3:1 contrast ratio for graphical elements and 4.5:1 for text elements [28]

- Dual Encodings: Use patterns, textures, or direct labels in addition to color to convey meaning [29]

- Text Alternatives: Provide comprehensive descriptions of trends and patterns for non-visual users [29]

- Simplified Visualizations: Prefer familiar chart types over complex novelties to enhance comprehension [29]

These principles are particularly important for representing multidimensional fitness landscape data, where epistatic interactions create complex topographic features that must be clearly communicated to diverse scientific audiences.

High-throughput sequencing technologies, combined with sophisticated in vitro selection methodologies, have enabled unprecedented experimental delineation of fitness landscapes. The integration of ancestral sequence reconstruction with deep mutational scanning provides both evolutionary depth and local resolution, revealing the fundamental role of epistasis in constraining evolutionary trajectories. As sequencing accuracy continues to improve and analytical tools like EasyDIVER+ become more advanced, researchers are better equipped to unravel the complex relationship between protein sequence, function, and evolvability, with significant implications for understanding molecular evolution and engineering novel biological functions.

The computational reconstruction of genetic sequences and their frequencies before and after selection provides a powerful lens through which to study molecular evolution. This approach allows researchers to move beyond static sequence analysis to dynamic models that capture how populations adapt under selective pressures. Within the broader context of fitness landscapes and epistasis research, these reconstruction methodologies enable scientists to decode the complex interplay between genotype, phenotype, and environment that drives evolutionary change. The ability to accurately model these processes has profound implications for understanding drug resistance evolution, engineering proteins with novel functions, and reconstructing ancestral molecular states [9].

At the heart of this field lies the fundamental concept that selection acts on phenotypic variations arising from genetic diversity, altering sequence frequencies in predictable ways. Computational reconstruction serves as the bridge between observed genetic data and the inferred evolutionary dynamics that generated that data. By integrating population genetics, structural biology, and sophisticated algorithms, researchers can now model the trajectories of sequence evolution with increasing accuracy, revealing how epistatic interactions and fitness landscape topography guide evolutionary outcomes [30] [9].

Theoretical Foundations: Fitness Landscapes and Epistasis

Fitness Landscape Models

Fitness landscapes provide a conceptual framework for visualizing evolution as navigation on a topological surface where height corresponds to fitness. In these landscapes, genotypes represent coordinates, and the connectedness of genotypes reflects their mutational accessibility. The structure of these landscapes—particularly their ruggedness—profoundly influences evolutionary dynamics. Rugged landscapes with multiple peaks emerge from epistatic interactions, where the fitness effect of a mutation depends on the genetic background in which it occurs [9].

The Tradeoff-Induced Landscape (TIL) model offers an empirically grounded framework for studying evolution under universal antagonistic pleiotropy. In this model, fitness depends on two key phenotypes: stress resistance level (σ) and null-fitness (defined as fitness in the absence of stress). Each mutation simultaneously affects both phenotypes in opposite directions, creating the fundamental tradeoff that shapes the landscape. The mathematical representation of fitness in this model follows a Hill-type response curve:

fσ(x) = rσ / [1 + (x/mσ)^α]

Where rσ represents the null-fitness, mσ the resistance level, x the environmental stress variable (e.g., drug concentration), and α the Hill coefficient determining curve steepness [9].

Epistasis and Compensatory Evolution

Epistasis plays a crucial role in shaping evolutionary trajectories on fitness landscapes. Research has revealed a phenomenon called "exchange compensation," where initial adaptation occurs through rapid accumulation of resistance mutations with high fitness costs, followed by a slower phase where these are replaced by lower-cost mutations. This process occurs without reverting to the original environment and demonstrates how changing epistatic interactions enable compensatory evolution even under constant selective pressure [9].

Table 1: Key Parameters in Fitness Landscape Models