Fossil Calibration in Molecular Clock Dating: Validation Methods, Challenges, and Best Practices for Evolutionary Research

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the critical role of fossil calibration in validating molecular clock models for estimating evolutionary timescales.

Fossil Calibration in Molecular Clock Dating: Validation Methods, Challenges, and Best Practices for Evolutionary Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the critical role of fossil calibration in validating molecular clock models for estimating evolutionary timescales. Aimed at researchers and scientists in evolutionary biology and genomics, we explore the foundational principles of molecular dating, the methodological approaches for incorporating fossil data, and the significant impact of calibration choice on divergence time estimates. Through case studies and comparative analyses, we address common sources of error and present optimization strategies to enhance the accuracy and reliability of molecular time trees, with implications for biogeography, speciation studies, and understanding evolutionary responses to past environmental change.

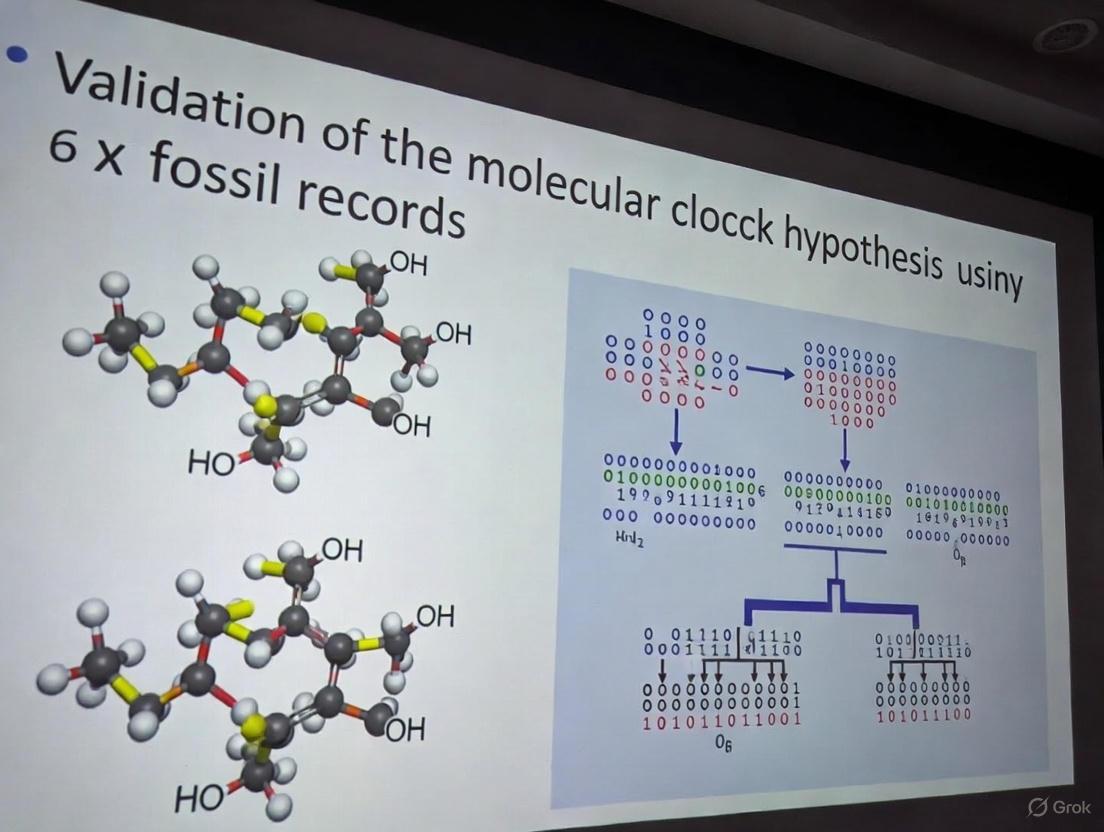

The Molecular Clock Hypothesis and the Imperative of Fossil Calibration

The Molecular Clock Hypothesis (MCH) represents a foundational concept in evolutionary biology, proposing that the rates of amino acid changes in proteins and nucleotide changes in DNA are approximately constant over time [1]. First proposed by Émile Zuckerkandl and Linus Pauling in the 1960s, this hypothesis emerged from their observations that the rate of amino acid substitution in proteins like cytochrome c, hemoglobin, and fibrinopeptides appeared to follow a time-dependent pattern [1]. The immediate appeal of this hypothesis was its potential to serve as a tool for estimating evolutionary timelines—researchers could compare molecular sequences between species and, if the substitution rate was known, calculate divergence times from common ancestors, potentially overcoming gaps in the fossil record [1].

Over subsequent decades, the initial enthusiasm for a universal molecular clock faced significant challenges. As more protein and DNA sequence data became available, researchers discovered that molecular substitution rates were not as "clocklike" as initially hoped. Rates were found to vary between different evolutionary lineages and over time, leading to substantial controversy and debate within the evolutionary community [1]. The neutral theory of molecular evolution, proposed by Motoo Kimura in 1968, offered a theoretical framework by suggesting that mutations in non-coding regions or synonymous substitutions (those not changing the amino acid sequence) would be unaffected by natural selection and thus might accumulate at more constant rates [1]. Despite this theoretical advancement, empirical evidence continued to show variations even in supposedly neutral mutations, leading most evolutionists to conclude by the 1980s that very few genes or neutral sequences behaved precisely like a clock [1].

In contemporary science, the strict molecular clock hypothesis has largely been replaced by more sophisticated relaxed clock models that accommodate rate variations across lineages and through time [1] [2]. These modern approaches have transformed the MCH from a simple timing tool into a powerful framework for investigating diverse evolutionary processes, including the timing of species divergences, the origins of epidemics, and even the molecular basis of circadian rhythms in biomedical contexts [3] [4] [5].

Modern Molecular Dating Methods: A Technical Comparison

The landscape of molecular dating has evolved significantly from the initial strict clock assumption, with current methods designed to handle the inherent rate variation observed in empirical datasets. These methods can be broadly categorized into Bayesian approaches and fast dating methods, each with distinct theoretical foundations and computational requirements.

Methodological Foundations

Bayesian methods represent the gold standard in molecular dating, implementing complex models that account for uncertainty in multiple parameters. These methods use Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling to approximate posterior distributions of divergence times, incorporating prior information such as fossil calibrations and models of rate variation across branches [2] [6]. Common Bayesian implementations include BEAST, MCMCTree, and PhyloBayes, which can model both autocorrelated rates (where descendant branches have similar rates to their ancestors) and uncorrelated rates (where each branch has an independent rate drawn from a specific distribution) [2] [6].

Fast dating methods have emerged to address the computational challenges of Bayesian approaches, particularly with large phylogenomic datasets. The two most prominent are:

Penalized Likelihood (PL): Implemented in software like treePL, this approach uses a likelihood component combined with a penalty function that minimizes rate changes between adjacent branches, assuming some degree of autocorrelation in evolutionary rates [2] [6]. A key element is the smoothing parameter (λ), optimized through cross-validation, which controls the permitted level of rate variation across the phylogeny [2].

Relative Rate Framework (RRF): Implemented in RelTime, this method minimizes differences in evolutionary rates between ancestral and descendant lineages individually rather than using a global penalty function [2]. RRF does not require a cross-validation step and can accommodate rate differences between sister lineages while maintaining computational efficiency [2].

Performance Comparison of Dating Methods

Recent comparative studies have evaluated the performance of these methods across multiple empirical datasets. A 2022 analysis of 23 phylogenomic datasets provides quantitative insights into how fast dating methods compare to Bayesian approaches, which serve as the benchmark [2].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Molecular Dating Methods

| Method | Computational Speed | Node Age Accuracy | Uncertainty Estimation | Calibration Flexibility | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bayesian (BEAST, MCMCTree) | Slow (days to weeks) | Benchmark standard | Comprehensive (posterior distributions) | High (multiple priors) | Definitive analyses, small to medium datasets |

| Penalized Likelihood (treePL) | Intermediate (hours to days) | Consistent but with low uncertainty | Limited (bootstrap) | Low (hard-bounded) | Large datasets with autocorrelated rates |

| Relative Rate Framework (RelTime) | Fast (minutes to hours) | Statistically equivalent to Bayesian | Analytical confidence intervals | Moderate (calibration densities) | Large phylogenomic screens, hypothesis testing |

The comparative analysis revealed that RRF via RelTime was computationally faster (more than 100 times faster than treePL) and generally provided node age estimates statistically equivalent to Bayesian divergence times [2]. Additionally, RRF showed advantages in its ability to incorporate calibration density distributions rather than requiring hard bounds [2]. Conversely, PL with treePL consistently exhibited low levels of uncertainty in its estimates, potentially underestimating the true variance in divergence times [2].

Factors influencing the accuracy and precision of molecular dating include gene function (genes under strong negative selection, such as those involved in core biological functions like ATP binding and cellular organization, tend to provide more consistent estimates), alignment length, rate heterogeneity between branches, and average substitution rate [7]. Shorter alignments with high rate heterogeneity and low average substitution rates generally provide less reliable dating information, resulting in reduced statistical power [7].

Experimental Approaches: Validating Molecular Clocks

Workflow for Molecular Dating Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the generalized workflow for conducting molecular dating analysis, integrating steps from empirical studies and methodological comparisons:

Assessing Temporal Signal and Clock Violations

A critical step in molecular dating involves verifying the presence of sufficient temporal signal in the dataset—the measurable accumulation of genetic differences over time that enables divergence time estimation [4]. Common approaches include:

- Root-to-tip regression: Plotting genetic distances of sequences from an inferred root against their sampling dates to assess correlation [4].

- Date-randomization tests: Randomizing sampling dates across sequences to determine if the true dataset produces significantly better temporal structure than randomized versions [4].

- Bayesian evaluation of temporal signal (BETS): Statistical assessment of whether sequence data contain meaningful temporal information [4].

The rabies virus (RABV) provides an interesting case study for examining molecular clock assumptions. With its unusually extended and variable incubation periods (ranging from days to over a year), researchers have investigated whether RABV evolution follows a per-generation rather than per-time-unit model of mutation accumulation [4]. Simulation studies comparing these models found that at RABV's characteristic low substitution rate (approximately 0.17 substitutions per genome per generation), the per-generation and molecular clock models were difficult to distinguish in contemporary outbreaks, as extreme incubation periods tend to average out over multiple generations [4].

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Molecular Dating Research

| Tool/Resource | Function | Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| BEAST2 | Bayesian evolutionary analysis | MCMC sampling with relaxed clock models |

| MCMCTree | Bayesian dating with approximate likelihood | Divergence time estimation for large datasets |

| treePL | Penalized likelihood dating | Fast dating with autocorrelated rates |

| RelTime | Relative rate framework dating | Fast dating without global rate autocorrelation |

| TempEst | Temporal signal analysis | Root-to-tip regression visualization |

| PAML | Phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood | Suite of evolutionary genetics tools |

Molecular Clocks Beyond Evolutionary Biology: Applications in Medicine and Pharmacology

While originally developed for evolutionary studies, molecular clock concepts have found significant applications in biomedical research, particularly through the lens of circadian biology. The discovery of clock and clock-controlled genes in mammals in 1997 revealed that biological rhythms impact both normal physiology and disease pathophysiology, creating opportunities for timed therapeutic interventions [3].

Circadian Clocks in Drug Response

Chronopharmacology investigates how biological rhythms influence drug pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics [3]. Research has demonstrated that the effectiveness and toxicity of many drugs vary depending on their administration timing relative to circadian rhythms:

- Antitumor drugs: Dosing-time-dependent differences in therapeutic outcomes and safety profiles have been observed for multiple chemotherapeutic agents [3].

- Chronopharmacokinetics: Daily variations affect each stage of drug processing—absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination—due to rhythmic changes in gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, hepatic, and renal functions [3].

- Chronopharmacodynamics: Biological rhythms at cellular and subcellular levels cause dosing-time differences in drug effects unrelated to pharmacokinetics, potentially explained by rhythms in receptor numbers or conformation, second messenger systems, and signal transduction pathways [3].

Molecular Clocks in Depression and Antidepressant Response

Recent research has revealed intriguing connections between molecular clocks in specific brain regions and neuropsychiatric disorders. A 2024 study demonstrated that the prefrontal cortex molecular clock modulates the development of depression-like phenotypes and rapid antidepressant response in mice [5]. Key findings include:

- Clock gene disruptions: In a mouse model of depression, the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) showed increased expression of circadian negative loop genes (Per2, Cry2) and decreased expression of positive clock regulators (Rorα, Rorβ) [5].

- Ketamine effects: The rapid antidepressant ketamine counteracted these changes, downregulating clock suppressor genes and potentiating positive regulators, suggesting its mechanism may involve modulation of circadian clock function [5].

- Genetic manipulations: Selective knockout of the core clock gene Bmal1 in mPFC excitatory neurons delayed the development of depression-like behavior, while Per2 silencing produced antidepressant-like effects [5].

The following diagram illustrates the molecular interplay within the circadian clock system and its potential manipulation for therapeutic purposes:

The Molecular Clock Hypothesis has undergone substantial transformation since its initial formulation—evolving from a simplistic assumption of rate constancy to sophisticated models that accommodate the complex reality of molecular evolution. This evolution has expanded its applications from primarily dating species divergences to informing pharmaceutical development and understanding disease mechanisms.

Future developments in molecular dating will likely focus on integrating multiple genomic loci to overcome the limitations of single-gene analyses [7], developing more realistic models of rate variation that better capture evolutionary processes [4] [6], and improving statistical frameworks for assessing uncertainty in divergence time estimates [7] [2]. Similarly, in biomedical applications, research is advancing toward chronotherapeutic drug delivery systems that synchronize drug concentrations with biological rhythms [3] and pharmacological manipulation of molecular clocks as novel treatment strategies for various disorders [5].

The continued refinement of molecular clock methodologies, coupled with their expanding applications across biological disciplines, ensures that this once-controversial hypothesis will remain a fertile ground for scientific discovery, bridging evolutionary history with therapeutic innovation.

Molecular clocks provide the primary neontological tool for estimating the temporal origins of clades, functioning by measuring evolutionary time through genetic changes that accumulate at relatively constant rates [8]. The fundamental principle relies on the neutral theory of molecular evolution, which posits that most mutations are neutral and accumulate at a rate proportional to time [8]. However, converting genetic distances into absolute geological time represents a significant challenge in evolutionary biology because genetic distance alone is a product of both time and substitution rate (T = D / (2R)) [8]. Without external calibration, molecular clocks can estimate relative divergence times but cannot provide absolute ages in millions of years.

Calibration serves as the critical bridge between relative genetic distances and absolute geological time by providing independent age constraints for specific nodes in a phylogeny. The paramount importance of calibration stems from the reality that even sophisticated molecular dating methods cannot accurately convert genetic distances to geological time without external temporal anchors [9]. Current patterns in calibration practices reveal that over half of all phylogenetic analyses implement one or more fossil dates as constraints, followed by geological events and secondary calibrations (15% each) [9]. This comparison guide examines the performance, experimental data, and methodological protocols of different calibration approaches, providing researchers with evidence-based guidance for selecting appropriate calibration strategies in molecular clock studies.

Comparative Analysis of Calibration Methods

Performance Metrics Across Calibration Types

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Major Calibration Methods

| Calibration Type | Frequency of Use | Typical Error Range | Key Strengths | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fossil Calibrations | 52% of analyses [9] | Varies with fossil quality; ~12% with optimal placement [10] | Provides direct historical evidence; Well-established protocols [9] | Limited availability for many clades; Interpretation challenges [9] |

| Geological Events | 15% of analyses [9] | Highly variable; dependent on vicariance assumption validity | Useful when fossils are absent; Multiple potential calibration points [9] | Assumes vicariance causation; Dating of events may be uncertain [9] |

| Secondary Calibrations | 15% of analyses [9] | ~10% overestimation with low precision [11] | Unlimited source of constraints; Enables dating of poorly calibrated clades [11] | Compounded errors from original study; Overly narrow confidence intervals [11] |

| Sampling Dates | 4% of analyses [9] | High precision for recent divergences | Excellent for rapidly evolving organisms; Point calibrations with exact dates [9] | Limited to recent timeframes; Requires heterochronous data [9] |

| Substitution Rates | 12% of analyses [9] | Variable based on rate appropriateness | Direct application without external evidence; Useful for viral evolution [9] | Laboratory rates may not reflect natural settings; Circularity risks [9] |

Quantitative Error Analysis Across Methodologies

Table 2: Error Analysis of Molecular Dating Under Different Calibration Scenarios

| Calibration Scenario | Analysis Method | Average Divergence Time Error | Key Findings | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unlinked speciation/substitution rates | Uncorrelated prior (BEAST 2) | 12% of node age | Most accurate scenario when model matches reality | [10] |

| Punctuated evolution model | Autocorrelated prior (PAML) | Up to 91% of node age | Worst-case scenario with model mismatch | [10] |

| Secondary vs. Primary Calibrations | RelTime analysis | ~10% overestimation (secondary) | Secondary calibrations produce predictable overestimation | [11] |

| Distant Primary Calibrations | RelTime analysis | Similar error rate but ~2x better precision | Few primary calibrations yield more precise estimates | [11] |

| Internal vs. External Fossil Constraints | Bayesian relaxed clock | Significant reduction in variation with internal constraints | Internal calibrations produce more consistent results | [12] |

Experimental Protocols for Molecular Clock Calibration

Fossil Calibration Protocol with Cross-Bracing Methodology

Objective: To implement fossil calibrations using pre-LUCA (Last Universal Common Ancestor) gene duplicates with cross-bracing to reduce uncertainty in divergence time estimates [13].

Methodology Details:

- Gene Selection: Identify universal paralogues that duplicated before LUCA with two or more copies in LUCA's genome (e.g., catalytic and non-catalytic subunits from ATP synthases, elongation factor Tu and G, signal recognition protein and signal recognition particle receptor) [13].

- Phylogenetic Analysis: Construct gene trees where the root represents the pre-LUCA duplication, and LUCA is represented by two descendant nodes [13].

- Cross-Bracing Implementation: Apply the same fossil calibrations to both sides of the gene tree, effectively doubling the calibration points and reducing uncertainty when converting genetic distance to absolute time [13].

- Calibration Placement: Use soft-uniform bounds with maximum-age bound based on the Moon-forming impact (4,510 Ma ± 10 Myr) and minimum bound based on definitive fossil evidence (e.g., 2,954 Ma ± 9 Myr for oxygenic photosynthesis evidence) [13].

- Molecular Dating: Perform analyses under both autocorrelated rates (GBM) and independent-rates log-normal (ILN) relaxed-clock models to account for different patterns of rate variation [13].

Validation: Compare results from single genes and concatenations that exclude each gene in turn to ensure consistent timescales [13].

Internal Constraint Calibration Strategy for Crown Group Ages

Objective: To accurately estimate the age of crown group Palaeognathae using internal fossil constraints to avoid underestimation [12].

Methodology Details:

- Taxon Sampling: Include representative species from all major lineages (13 extant and extinct moa for nuclear datasets; 31 species covering all extant and extinct lineages for mitogenomic datasets) [12].

- Data Types: Assemble multiple genomic sequences from nuclear (noncoding CNEE and UCE, coding first and second codon positions) and mitogenomic datasets [12].

- Internal Calibration Placement: Position fossil calibrations within the clade of interest rather than solely on external nodes. For Palaeognathae, this includes fossils such as Emuarius, Diogenornis fragilis, and Lithornithidae [12].

- Comparison Framework: Analyze datasets with and without internal calibrations while keeping other parameters constant [12].

- Node Age Estimation: Use Bayesian relaxed clock methods with multiple MCMC runs to ensure convergence and adequate posterior sampling [12].

Key Finding: Studies including at least one internal calibration within Palaeognathae consistently placed the crown group origin around the K-Pg boundary (62-68 Ma), while analyses with only external calibrations produced significantly younger estimates (Eocene, ~51 Ma) [12].

Performance Evaluation of Secondary Calibrations

Objective: To quantify the amount of errors in estimates produced by secondary calibrations relative to true times and primary calibrations [11].

Methodology Details:

- Experimental Design: Create two nested phylogenies (Tree A with 173 species, Tree B with 71 species) that share one overlapping ingroup node to serve as the secondary calibration point [11].

- Sequence Simulation: Generate 446 gene alignments using empirical parameters (length, GC content, initial evolutionary rate) under a HKY model, with branch lengths altered according to an autocorrelated model [11].

- Calibration Scheme: In Tree A, use three primary calibrations at nodes of varying depths (63.9, 209.4, and 220.2 mya). Use the overlapping node (167 mya) as a secondary calibration for Tree B [11].

- Error Introduction: Test primary calibrations with increasingly larger uncertainties (0-20% departure from true time) and biases (balanced, skewed younger, skewed older) [11].

- Time Estimation: Analyze concatenated datasets using RelTime with HKY model, uniform rates among sites, and local clocks [11].

Validation Metric: Calculate the percentage difference between estimated and true node ages across multiple replicates to establish error patterns [11].

Visualization of Calibration Strategies and Outcomes

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Molecular Clock Calibration

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| BEAST | Software Package | Bayesian evolutionary analysis sampling trees; implements relaxed molecular clocks | Primary software for Bayesian molecular dating with multiple calibration types [14] [9] |

| ALE | Algorithm | Probabilistic gene- and species-tree reconciliation | Inferring gene family evolution accounting for duplications, transfers, and losses [13] |

| RelTime | Software Method | Relative dating method with minimal assumptions | Fast divergence time estimation, particularly useful for testing calibration approaches [11] |

| PAML | Software Package | Phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood | Implements various molecular clock models including autocorrelated priors [10] |

| KEGG Orthology | Database | Functional annotation of gene families | Gene content analysis and functional inference for ancestral genomes [13] |

| Primary Fossil Calibrations | Data Resource | Dated fossil occurrences with phylogenetic placement | Gold standard for node calibration when available with appropriate quality [9] [12] |

| Cross-Bracing Paralogs | Genetic Data | Pre-LUCA gene duplicates with conserved functions | Reducing uncertainty in deep evolutionary dating through duplicate calibration [13] |

| Geological Event Timeline | Data Resource | Dated geological events causing vicariance | Alternative calibration when fossils are limited or absent [9] |

The conversion of genetic distances to geological time remains dependent on careful calibration strategy regardless of methodological advances in molecular evolutionary models. Empirical evidence demonstrates that calibration choice significantly impacts divergence time estimates, with internal fossil constraints providing more consistent and biologically plausible results than external calibrations alone [12]. The performance trade-offs between calibration types indicate that fossil calibrations, when properly implemented following best practices, yield the most reliable temporal estimates [9].

Secondary calibrations, while providing an unlimited source of calibration points, introduce predictable errors including approximately 10% overestimation with low precision compared to primary calibrations [11]. However, they may serve as useful exploratory tools when primary calibrations are extremely limited. For crown group age estimation, evidence strongly supports the implementation of multiple internal calibrations to avoid significant underestimation that occurs when relying solely on external node constraints [12].

Future directions in molecular clock calibration should focus on integrating genomic-scale data with improved fossil interpretations, developing models that account for relationships between substitution rates and speciation, and creating more sophisticated probabilistic frameworks that better capture calibration uncertainty. Through strategic implementation of appropriate calibration methodologies, researchers can more accurately convert genetic distances into geological time, thereby providing robust temporal frameworks for understanding evolutionary history.

Molecular clock analyses estimate the timing of evolutionary events by measuring the accumulation of genetic mutations over time. However, to convert these relative genetic distances into absolute geological time, the clock must be "calibrated" using independent evidence. The choice of calibration source is a critical decision that directly controls the accuracy and reliability of the resulting divergence time estimates. Researchers primarily rely on three calibration sources: the fossil record, geological events, and secondary estimates from previous molecular dating studies. Each source presents distinct advantages, limitations, and methodological considerations that must be carefully balanced within the context of a study's goals and constraints.

The ongoing validation of molecular clocks with the fossil record represents a core challenge in evolutionary biology. As this guide will demonstrate, the scientific community is moving toward increasingly sophisticated approaches that combine multiple lines of evidence, acknowledge inherent uncertainties, and explicitly model the complexities of both molecular evolution and the fossil record.

Fossil Record Calibrations

The fossil record provides the most direct form of calibration for molecular dating, offering tangible evidence of past life. Fossil calibrations anchor phylogenetic trees in geological time by establishing minimum age constraints for lineages. The fundamental workflow involves identifying a fossil with confident phylogenetic placement, determining its geological age, and translating this information into a calibration prior for molecular clock analysis.

The following diagram illustrates the primary workflow for applying fossil calibrations in molecular clock research, from data collection to the final calibrated timetree:

Key Advantages and Limitations

The primary strength of fossil calibrations lies in their provision of direct empirical evidence of evolutionary history. Carefully placed fossils offer temporal benchmarks that are independent of molecular data, creating a powerful framework for testing evolutionary hypotheses [15]. Furthermore, the fossil record provides crucial contextual information about past biodiversity, paleoenvironments, and morphological evolution that cannot be inferred from molecular data alone [16].

However, several significant limitations must be acknowledged:

Temporal Incompleteness: The fossil record is inherently fragmentary, with the first appearance of a species in the record almost always post-dating its actual evolutionary origin [17]. This creates a persistent challenge known as the "first appearance date" (FAD) problem, where the true origin of a lineage precedes its fossil evidence by an unknown duration [17].

Phylogenetic Uncertainty: Confidently placing fossil taxa on a phylogeny based solely on morphological characters is often challenging and can be a source of significant error in calibration [15] [17].

Spatial and Taxonomic Biases: Fossil preservation is not uniform across regions, environments, or taxonomic groups. Terrestrial organisms, soft-bodied taxa, and tropical environments are consistently underrepresented, creating systematic gaps in calibration potential [16] [17].

Best Practices and Recent Innovations

To maximize reliability, researchers should select fossils with confident phylogenetic placements and use well-justified prior distributions that account for the uncertainty in the fossil's age and phylogenetic position [15]. A promising recent innovation is the "cross-bracing" technique, which uses genes that duplicated before the last universal common ancestor (LUCA). This approach applies the same fossil calibrations to multiple descendant lineages, effectively doubling the calibration points and reducing uncertainty in deep-time estimates [13].

Geological Event Calibrations

Principles and Applications

Geological event calibrations, also known as biogeographic calibrations, use dated geological events that likely caused vicariance (population splitting) to constrain divergence times. This method relies on establishing a causal link between a geological event and the isolation of lineages. Common examples include the formation of mountain ranges, changes in sea levels, or the emergence of land bridges.

Table 1: Common Geological Events Used for Calibration

| Geological Event | Divergence Example | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Continental Drift | Mammal divergences following Gondwana breakup [15] | Requires precise paleogeographic reconstruction |

| Mountain Uplift | Andean uplift driving speciation [15] | Must confirm vicariance rather than dispersal |

| Isthmus Formation | Marine species separations by Isthmus of Panama [15] | Dating of closure must be precise |

| River Formation | Amazonian speciation events | Requires robust paleodrainage models |

Advantages and Critical Caveats

When applicable, geological calibrations can provide highly precise and reliable calibration points, particularly for younger divergences where the geological record is well-dated. They are especially valuable for groups with poor fossil records but strong biogeographic signals. Unlike fossil calibrations, geological events can theoretically provide maximum constraint ages that closely approximate actual divergence times.

The most significant challenge is establishing a robust causal link between the geological event and the biological divergence. Alternative explanations, such as dispersal after the event or earlier divergence, must be rigorously excluded. Recent applications have demonstrated success when combining geological calibrations with other independent evidence, such as the use of horizontal gene transfer events between dated microbial lineages [18].

Secondary Calibrations

Definition and Implementation

Secondary calibrations (sometimes called "molecularly-derived calibrations") involve using node ages previously estimated from molecular clock analyses as calibration points in new studies. This approach has become increasingly common as phylogenomic datasets expand faster than the availability of new fossil evidence. In practice, a researcher might take a divergence time estimate (e.g., 4.2 Ga for LUCA [13]) and its confidence interval from a published study and apply it to calibrate their own analysis.

Quantitative Error Analysis

The use of secondary calibrations has been historically controversial due to concerns about error propagation. A 2020 simulation study quantified these errors by comparing time estimates from secondary calibrations against true simulated times and those derived from distant primary calibrations [18].

Table 2: Error Comparison Between Calibration Types (Simulation Data)

| Calibration Type | Average Inaccuracy | Precision (CI Width) | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Secondary Calibrations | ~10% overestimation | Low precision (wider CIs) | Errors are predictable and mirror primary calibration errors |

| Distant Primary Calibrations | Comparable error rates | ~2x better precision | Increasing dataset size improves precision more than accuracy |

The study revealed that while estimates from secondary calibrations showed predictable patterns of error, they exhibited lower precision (wider confidence intervals) compared to primary calibrations. This finding suggests that secondary calibrations may be most useful for exploring plausible evolutionary scenarios rather than producing highly precise date estimates [18].

Guidelines for Use

Secondary calibrations should not be considered a direct replacement for primary evidence. They may be appropriate when:

- No suitable primary calibrations are available for the clade of interest

- The study aims to explore broad evolutionary timescales rather than test specific hypotheses

- Uncertainty is properly incorporated and acknowledged in the interpretation

- The source study used rigorous methods and well-justified primary calibrations

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Comparisons

Core Molecular Clock Methodologies

Molecular clock analyses have evolved from strict clocks assuming constant evolutionary rates to more sophisticated "relaxed clock" models that accommodate rate variation across lineages [15]. The two primary frameworks for implementing these models are:

Bayesian Relaxed Clocks: Implemented in software like BEAST2, these methods use Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling to estimate posterior distributions of divergence times, explicitly incorporating uncertainty in fossil calibrations, evolutionary rates, and phylogenetic relationships [15].

RelTime Method: A non-Bayesian approach that provides faster computation for large datasets by estimating relative divergence times that are subsequently converted to absolute time using calibrations [18].

The multispecies coalescent (MSC) model represents a significant recent advancement, as it explicitly accounts for the difference between gene divergence and species divergence, which can be substantial when ancestral populations are large [15]. This is particularly important for accurately estimating recent divergences.

Integrated Protocol for Cross-Braced Calibration

A recent groundbreaking study on dating the last universal common ancestor (LUCA) provides an exemplary protocol for sophisticated calibration integration [13]:

- Gene Selection: Identify ancient gene duplicates that predate LUCA (e.g., ATP synthase subunits, aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases)

- Fossil Calibration: Apply microbial fossil calibrations with soft bounds, using Moon-forming impact (4.51 Ga) as maximum constraint

- Cross-Bracing: Apply the same calibrations to both copies of duplicated genes, doubling calibration points

- Phylogenetic Reconciliation: Use probabilistic algorithms (e.g., ALE) to account for gene duplication, transfer, and loss

- Model Testing: Compare results under both autocorrelated (GBM) and independent (ILN) rate models

This approach yielded an LUCA estimate of ~4.2 Ga (4.09-4.33 Ga) with a genome of at least 2.5 Mb, demonstrating the power of integrated methodology [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Computational Tools and Resources for Molecular Clock Calibration

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| BEAST2 | Software Package | Bayesian evolutionary analysis | Divergence time estimation with multiple calibrations [15] |

| MCMCtree | Software Package | Bayesian molecular dating | Fossil-calibrated relaxed clock analyses [15] |

| RelTime | Algorithm | Non-Bayesian relative dating | Fast analysis of large datasets [18] |

| ALE | Reconciliation Algorithm | Gene tree-species tree reconciliation | Modeling gene duplication, transfer, loss [13] |

| Paleobiology Database | Data Repository | Fossil occurrence data | Sourcing fossil calibration information [16] |

| KEGG/COG | Functional Database | Orthologous gene families | Functional annotation and gene family analysis [13] |

The comparison of calibration sources reveals that each approach carries distinct advantages and limitations that must be carefully weighed within any molecular dating study. Fossil calibrations provide direct but incomplete evidence, geological calibrations offer precision when causal links are robust, and secondary calibrations enable analyses when primary evidence is lacking but introduce predictable error patterns.

The field is increasingly moving toward integrative approaches that combine multiple calibration types while explicitly modeling their uncertainties. Future progress will likely come from several frontiers: improved fossil interpretation using functional diversity metrics [16], expanded use of genomic-scale mutation rate estimates [15], and the development of more sophisticated models that better reconcile the inevitable tensions between the molecular and fossil records. As these methodological advances continue, researchers must maintain rigorous standards in calibration selection, transparent reporting of uncertainties, and thoughtful interpretation of divergence time estimates within the context of all available evidence.

Molecular clock analyses, which estimate species divergence times from genetic data, have become a cornerstone of evolutionary biology, biogeography, and the study of diversification dynamics. The accuracy of these dating analyses is fundamentally dependent on the calibration points used to convert genetic distances into geological time. Calibration practices represent the most significant source of variation in molecular dating estimates, with inappropriate selection or implementation leading to substantially erroneous conclusions [9]. These errors can propagate through the scientific literature, affecting downstream analyses that rely on accurate temporal frameworks.

This guide examines the perils of improper calibration through empirical case studies, highlighting how both over- and under-estimation can distort our understanding of evolutionary history. We objectively compare the performance of different calibration strategies across taxonomic groups, providing experimental data and methodologies that researchers can apply to validate their own molecular clock analyses against the fossil record.

Calibration Types and Their Inherent Challenges

Molecular dating methods rely on various calibration types, each with distinct advantages and vulnerabilities. Understanding these categories is essential for recognizing potential sources of error in divergence time estimation.

Fossil Calibrations: The earliest known fossil assigned to a lineage provides a minimum age constraint on the divergence event at the base of its clade. When the fossil record is of sufficient quality, calibration uncertainty can be modeled using parametric distributions between minimum and maximum bounds (soft bounds) [9]. The primary challenge lies in the correct phylogenetic placement of fossils and accounting for the incompleteness of the fossil record [19].

Geological Calibrations: These are assigned to nodes based on the assumption that phylogenetic divergence was caused by vicariance events, such as the emergence of land bridges or islands. While useful for groups with poor fossil records, these calibrations assume a perfect correspondence between geological events and lineage splitting, which may not always reflect biological reality [9].

Secondary Calibrations: These are node ages derived from previous molecular clock analyses, applied to new datasets without reference to the original calibrations. While they provide an seemingly infinite source of calibration points, they risk compounding and propagating errors from earlier studies [11] [9].

Substitution Rate Calibrations: A known substitution rate is applied to sequence data to convert genetic distance into time. These rates may be estimated from direct observation of change in serially sampled data or indirectly from previously dated phylogenies [9].

Sampling Date Calibrations: For rapidly evolving organisms like viruses and bacteria, known sample ages are assigned to terminal nodes. Temporal information comes from the date of sequence isolation or radiocarbon dating of preserved material [9].

Table: Frequency of Different Calibration Types in Molecular Dating Literature (2007-2013)

| Calibration Type | Frequency in Literature | Primary Strengths | Primary Vulnerabilities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fossil | 52% | Direct historical evidence; tangible link to geological time | Incomplete record; challenging phylogenetic placement |

| Geological Event | 15% | Applicable to fossil-poor clades; precise dates often available | Assumes vicariance cause; may oversimplify biogeography |

| Secondary Calibration | 15% | Unlimited source; enables dating without primary data | Compounds prior errors; often overconfident (narrow CIs) |

| Substitution Rate | 12% | Direct for serially sampled data; simple application | Rate transferability issues; dependent on original calibration |

| Sampling Date | 4% | Highly precise for terminals; excellent for recent divergences | Limited to fast-evolving organisms; requires ancient DNA |

Case Studies of Calibration Error

Case Study 1: The Flightless Birds - How Internal Constraints Resolve Dating Conflicts

A striking example of how calibration strategy dramatically affects divergence estimates comes from studies of the Palaeognathae, an ancient bird lineage including ostriches, rheas, tinamous, and extinct moa and elephant birds.

The Discrepancy: Phylogenomic studies have consistently estimated the origin of crown Palaeognathae around the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) boundary (~66 million years ago), with one notable exception suggesting a much younger Early Eocene age (~51 million years ago) [20].

Experimental Comparison: Researchers investigated whether this conflict stemmed from differences in genomic data type or calibration strategy. They analyzed multiple datasets—mitogenomes, conserved non-exonic elements (CNEE), ultraconserved elements (UCE), and coding sequences—under different calibration schemes [20].

Root Cause Analysis: The Eocene estimate was produced by a study that placed all fossil calibrations within the Neognathae clade (sister to Palaeognathae), with no internal Palaeognathae calibrations and no calibrations at the deep neornithine root. In contrast, studies recovering the K-Pg age included at least one fossil calibration at the neornithine root, and most included internal Palaeognathae calibrations [20].

Resolution: Re-analysis of the dataset that originally produced the Eocene age, but with the addition of internal fossil constraints, consistently recovered the K-Pg age estimate of 62-68 million years ago. This demonstrates that calibration strategy had a greater impact on age estimates than the type of molecular data used [20].

Table: Impact of Calibration Strategy on Crown Palaeognathae Age Estimates

| Data Type | Calibration Strategy | Estimated Age (Ma) | Key Fossil Priors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclear (PRM) | No internal palaeognath calibrations | ~51 Ma (Eocene) | All within Neognathae |

| Nuclear (CNEE) | With internal calibrations | 62-68 Ma (K-Pg) | Neornithine root + internal Palaeognathae |

| Mitogenomic | With internal calibrations | 62-68 Ma (K-Pg) | Neornithine root + internal Palaeognathae |

| Multiple Nuclear | With internal calibrations | 62-68 Ma (K-Pg) | Neornithine root + internal Palaeognathae |

Case Study 2: The Volvocine Algae - Independent Origins and Temporal Frameworks

Research on volvocine algae (a group spanning from unicellular to multicellular organisms) demonstrates how robust, fossil-calibrated molecular clocks can reconstruct the sequence of evolutionary innovation.

Methodology: To establish a geological timeline for this group with a sparse direct fossil record, researchers employed a cross-clade calibration approach. They used 14 fossil taxa across Archaeplastida (red algae, streptophytes, and chlorophytes) to calibrate a phylogeny using 263 single-copy nuclear genes from 164 taxa [21].

Finding: This analysis revealed that multicellularity evolved independently twice in volvocine algae: once in the Tetrabaenaceae family (possibly as early as the Cretaceous) and again in the common ancestor of Goniaceae and Volvocaceae during the Carboniferous-Triassic [21].

Broader Implication: This study showcases a best-practice protocol for groups with limited direct fossils: leveraging a robust, fossil-calibrated backbone phylogeny of a larger, related clade to estimate divergence times within the focal group. This approach avoids the circularity of secondary calibrations while providing a geologically contextualized timeline.

Case Study 3: Quantifying Error in Secondary vs. Primary Calibrations

The use of secondary calibrations is often discouraged, but the magnitude of their error has been quantified through simulation studies.

Experimental Design: A simulation study created two nested phylogenies (Trees A and B) sharing an overlapping node. Tree A was calibrated with three primary calibrations, and the overlapping node age was then used as a secondary calibration for Tree B. The performance of this secondary calibration was compared to using distant primary calibrations from Tree A [11].

Key Results: Contrary to some previous findings, secondary calibrations did not consistently produce younger estimates. However, they did demonstrate predictable error patterns and lower precision [11].

- Accuracy: Estimates based on secondary calibrations were generally overestimated by approximately 10% compared to true times.

- Precision: The confidence intervals for estimates derived from distant primary calibrations were roughly twice as precise as those from secondary calibrations. This means secondary calibrations often produce estimates that are inaccurate yet appear deceptively certain (with overly narrow confidence intervals) [11] [9].

Recommendation: If secondary calibrations must be used, researchers should generously inflate the uncertainty bounds associated with them to account for this compounded error and avoid overconfident conclusions.

Experimental Protocols for Robust Molecular Dating

Protocol: Fossil Calibration with Cross-Clade Constraints

This protocol is adapted from methodologies used in the volvocine algae study [21] and is ideal for groups with a poor direct fossil record.

- Taxon Sampling: Assemble a comprehensive dataset that includes the focal group (e.g., volvocine algae) along with multiple representatives from its broader phylogenetic context (e.g., Archaeplastida).

- Fossil Selection: Identify robust, well-vetted fossils from across the broader clade. Prioritize fossils with unambiguous phylogenetic placements and reliable geological ages.

- Sequence Alignment and Model Selection: Use appropriate software (e.g., MAFFT, MUSCLE) for sequence alignment. Partition data and select best-fit substitution models using tools like PartitionFinder or ModelTest.

- Divergence Time Analysis: In a Bayesian framework (e.g., BEAST2, MCMCTree), implement a relaxed clock model (e.g., uncorrelated lognormal) to account for rate variation among lineages.

- Calibration Placement: Assign fossil calibrations as priors to the corresponding nodes in the broader clade. Use appropriate parametric distributions (e.g., lognormal, exponential) to reflect the uncertainty of the fossil minimum ages.

- Divergence Estimation: The analysis will then estimate node ages for the entire tree, including the focal group, based on the genetic data and the fossil constraints from the broader clade.

Protocol: Testing Sensitivity to Calibration Strategy

This protocol, informed by the palaeognath bird studies [20], is crucial for evaluating the robustness of divergence time estimates.

- Dataset Assembly: Compile a phylogenomic dataset for the group of interest.

- Calibration Scheme Design: Design multiple calibration schemes:

- Scheme A: Using only external/outgroup fossil calibrations.

- Scheme B: Including one or more carefully justified internal fossil calibrations.

- Scheme C: Using secondary calibrations from published literature.

- Comparative Analysis: Run identical molecular clock analyses (same data, models, priors) for each calibration scheme.

- Divergence Comparison: Compare the resulting age estimates and their confidence intervals for key nodes of interest (e.g., crown group origin).

- Robustness Assessment: Identify nodes with significant variation across analyses. Results that are stable across multiple calibration schemes are considered more robust. Treat estimates from analyses with only external calibrations or secondary calibrations with caution if they conflict with those derived from internal fossil constraints.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table: Key Reagents and Software for Molecular Clock Analyses

| Item/Resource | Category | Function in Analysis | Example Tools/Citations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fossil Calibration Databases | Data Resource | Provide vetted fossil data and recommended calibration priors | Paleobiology Database; Fossil Calibration Database |

| Sequence Alignment Tools | Software | Align nucleotide/amino acid sequences for phylogenetic analysis | MAFFT, MUSCLE, ClustalW |

| Model Selection Programs | Software | Determine best-fit substitution model for phylogenetic data | PartitionFinder, ModelTest-NG, jModelTest |

| Bayesian Evolutionary Analysis | Software | Perform molecular clock dating with complex models | BEAST2, MrBayes, MCMCTree (PAML) |

| Relaxed Clock Models | Analytical Model | Account for variation in substitution rates across lineages | Uncorrelated Lognormal (UCLN); Uncorrelated Gamma (UCG) [15] |

| Multispecies Coalescent (MSC) Models | Analytical Model | Jointly estimate species divergence and ancestral population sizes while accounting for incomplete lineage sorting | StarBEAST2 [15] |

| Conserved Loci | Genomic Markers | Provide phylogenetically informative data for divergence dating at different time scales | Ultraconserved Elements (UCEs), Conserved Non-Exonic Elements (CNEEs) [20], single-copy nuclear genes [21] |

Inappropriate calibration remains a critical peril in molecular dating, capable of producing estimates that are overconfident, inaccurate, or both. The case studies presented here demonstrate that:

- Calibration strategy can outweigh data influence: The choice and placement of fossil priors can have a greater impact on estimated divergence times than the type of molecular data analyzed [20].

- Internal constraints are crucial: Relying solely on external or distant calibrations can lead to significant underestimation of node ages, as evidenced by the palaeognath bird case.

- Secondary calibrations compound error: While sometimes necessary, secondary calibrations introduce predictable inaccuracies and should be used with caution and appropriately inflated uncertainties [11].

- Cross-clade calibration is a powerful alternative: For groups with poor fossil records, leveraging the robust fossil record of a broader related clade provides a more reliable temporal framework than resorting to secondary calibrations [21].

Robust molecular dating requires careful calibration practices, including sensitivity analyses of different calibration schemes and a critical assessment of the fossil record. By adopting the experimental protocols and analytical frameworks outlined here, researchers can mitigate the perils of inappropriate calibration and produce more reliable estimates of the evolutionary timescale.

In the field of evolutionary biology, accurately reconstructing historical timelines is fundamental to understanding the origins and relationships of species. Two distinct approaches for calculating evolutionary rates have emerged: the genealogical mutation rate and the phylogenetic mutation rate [22]. The genealogical mutation rate, measured by comparing closely related individuals with known relationships, reflects observable mutations within recent generations. In contrast, the phylogenetic mutation rate is calculated by counting fixed genetic differences between species and dividing by their estimated time since divergence from a common ancestor [22]. This critical distinction in methodology and temporal scope creates significant discrepancies in estimated timelines of evolution, with profound implications for interpreting everything from human origins to microbial evolution. Understanding these differing approaches provides a essential foundation for validating molecular clocks with fossil records.

Quantitative Comparison of Time-Scale Methodologies

Table 1: Core Distinctions Between Genealogical and Phylogenetic Mutation Rates

| Characteristic | Genealogical Mutation Rate | Phylogenetic Mutation Rate |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Data Source | Comparisons of closely related individuals [22] | Fixed differences between species [22] |

| Time Scale | Recent, observable generations [22] | Deep evolutionary time [22] |

| Mutation Rate | Generally faster [22] | Generally slower by orders of magnitude [22] |

| Implications for Human Origins | Places Y Chromosome Adam and Mitochondrial Eve within biblical timeframe [22] | Suggests much earlier origins for modern humans |

| Dependence on Fossil Calibration | Limited | Critical for establishing divergence times |

Table 2: Impact of Time-Scale Selection on Evolutionary Dating

| Organism Group | Genealogical Timeline Estimate | Phylogenetic Timeline Estimate | Key Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modern Bacteria | Not applicable | Last common ancestor: 4.4-3.9 billion years ago [23] | Genomic records with geochemical boundaries [23] |

| Volvocine Algae | Not applicable | Multicellularity evolved Carboniferous-Triassic to Cretaceous [21] | Fossil-calibrated molecular clocks [21] |

| Major Bacterial Phyla | Not applicable | Ancestors in Archaean-Proterozoic (2.5-1.8 billion years ago) [23] | Genomic data with machine learning predictions [23] |

Experimental Protocols for Time-Scale Determination

Genealogical Mutation Rate Protocol

The genealogical approach requires specific methodological rigor. The first step involves sample selection of individuals with known familial relationships, often from pedigree databases or controlled breeding experiments. Researchers then conduct whole-genome sequencing of these related individuals to identify DNA sequence differences. The key analysis phase involves counting de novo mutations by comparing offspring genomes to parental sequences, establishing a direct measure of mutation accumulation across a known number of generations. Finally, the mutation rate calculation is performed by dividing the total observed mutations by the number of meioses (generation transfers) and the total analyzable genomic sites [22]. This protocol yields a directly observed, measurable mutation rate, though its application is necessarily limited to recent time scales.

Phylogenetic Mutation Rate Protocol with Fossil Calibration

The phylogenetic mutation rate protocol employs fundamentally different methods suited for deep evolutionary time. The initial step involves orthologous gene identification across the target species, ensuring comparison of truly homologous sequences. Researchers then perform multiple sequence alignment and calculate the number of fixed differences - genetic changes that have become universal in each species. The critical fossil calibration step follows, where fossil evidence of divergence times is incorporated to establish minimum age constraints for specific evolutionary splits [21]. For example, in volvocine algae studies, researchers sampled "14 fossil taxa across the three major Archaeplastida clades (Rhodophyta, Streptophyta, and Chlorophyta)" to calibrate molecular clocks across "an interval of at least one billion years" [21]. Finally, molecular clock modeling employs statistical approaches (often Bayesian methods) to estimate substitution rates that explain the observed genetic differences within the fossil-calibrated timeframe [23] [21].

Figure 1: Phylogenetic mutation rate protocol with essential fossil calibration steps highlighted.

Current Research Applications & Methodological Validation

Microbial Evolution Studies

Recent research on bacterial evolution demonstrates sophisticated implementation of fossil-calibrated molecular clocks. Scientists from Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology addressed the challenge of dating microbial evolution by using the Great Oxygenation Event (GOE) approximately 2.3 billion years ago as a critical time boundary [23]. Their innovative approach combined genomic records with probabilistic methods to infer ancient gene content and machine learning algorithms to predict oxygen usage in ancestral bacteria [23]. This methodology revealed that "at least three lineages had aerobic lifestyles before the GOE – the earliest nearly 900 million years before," suggesting oxygen use long before atmospheric accumulation [23]. The study established that "the last common ancestor of all modern bacteria lived sometime between 4.4 and 3.9 billion years ago," providing a comprehensive timeline for bacterial evolution [23].

Multicellularity Evolution Research

Research on volvocine algae exemplifies how molecular clocks calibrated with external fossil evidence can reconstruct evolutionary transitions. Researchers analyzed "263 single-copy nuclear genes drawn from 164 taxa across the Archaeplastida" to establish divergence times within this key group [21]. Without direct volvocine fossils, they leveraged "14 fossil taxa across the Archaeplastida" including red algae fossils "that may be 1.6 billion years old" to calibrate their molecular clocks [21]. This approach enabled them to determine that "multicellularity arose independently twice in the volvocine algae" - once during the Carboniferous-Triassic in Goniaceae + Volvocaceae, and possibly again during the Cretaceous in Tetrabaenaceae [21]. Furthermore, they could correlate "multicellularity with the acquisition of anisogamy and oogamy," tracing the stepwise evolution of complex traits [21].

Figure 2: Integrated workflow combining genomic inference with external validation sources.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Time-Scale Studies

| Tool/Resource | Category | Primary Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bayesian Evolutionary Analysis | Statistical Software | Models sequence evolution with time constraints | Dating bacterial divergence using fossil priors [23] |

| Whole-Genome Sequencing | Laboratory Technique | Determines complete DNA sequence | Identifying de novo mutations in pedigrees [22] |

| Machine Learning Algorithms | Computational Tool | Predicts ancestral traits from genomic data | Inferring oxygen use in ancient bacteria [23] |

| Fossil Calibration Database | Curated Resource | Provides minimum age constraints for divergences | Archaeplastida fossils for volvocine dating [21] |

| Multiple Sequence Alignment Tools | Bioinformatics Software | Aligns homologous sequences across taxa | Calculating fixed differences between species [22] |

Critical Assessment & Research Implications

The distinction between genealogical and phylogenetic time-scales represents more than a methodological curiosity - it poses fundamental questions about evolutionary rates and timelines. The observation that "genealogical mutation rates are generally several orders of magnitude faster than phylogenetic estimates" creates significant challenges for evolutionary models [22]. Evolutionary biologists sometimes invoke "natural selection or genetic drift to explain away the discrepancy," though population modeling suggests these explanations may be insufficient [22].

For drug development professionals and biomedical researchers, these distinctions have practical importance. Understanding mutation rates informs models of pathogen evolution, cancer development, and the emergence of drug resistance. The genealogical rate better reflects observable, contemporary mutation processes relevant to disease progression, while phylogenetic rates provide context for deeper evolutionary constraints on protein function and interaction networks. The integration of both approaches, validated through fossil evidence where available, creates the most powerful framework for understanding biological change across time scales from epidemiological to evolutionary.

A Practical Framework for Fossil Calibration and Molecular Dating

Molecular dating represents a cornerstone of evolutionary biology, transforming our understanding of the temporal dimensions of the tree of life. The molecular clock hypothesis, initially proposed by Zuckerkandl and Pauling, has undergone significant refinement with the development of Bayesian relaxed clock models that accommodate the reality of rate variation across lineages. These sophisticated statistical approaches allow evolutionary rates to vary among branches according to specified probabilistic models, thereby reconciling genetic distances with divergence times without imposing a strict clock-like constraint. Concurrently, Bayesian methods provide a coherent framework for incorporating fossil calibrations as probabilistic priors, explicitly acknowledging the inherent uncertainty in the paleontological record. This review synthesizes current methodologies for implementing Bayesian relaxed clocks, with particular emphasis on model selection, calibration treatment, and experimental validation, providing researchers with a critical framework for evaluating molecular dating analyses within the broader context of validating molecular clocks with fossil records research.

Understanding Rate Heterogeneity Models

The Spectrum of Clock Models

Bayesian molecular dating methods primarily operate under three classes of clock models, each making distinct assumptions about how evolutionary rates vary across phylogenetic trees. The strict clock model assumes a constant substitution rate across all branches, an assumption often violated in real datasets, particularly those spanning deep evolutionary timescales or diverse taxonomic groups. In contrast, relaxed clock models explicitly accommodate rate variation through two principal frameworks: autocorrelated and uncorrelated models.

Autocorrelated relaxed clocks operate under the assumption that evolutionary rates change gradually over time, resulting in correlation between ancestral and descendant lineage rates. Implemented in software such as MultiDivTime, these models typically parameterize rate evolution as a lognormal distribution with the mean equal to the rate of the ancestral branch. The variance is often modeled as proportional to branch length duration, meaning that rates on shorter branches show greater similarity to their ancestral rates.

Uncorrelated relaxed models, available in packages like BEAST and MCMCTree, treat the rate on each branch as an independent draw from a specified underlying distribution, typically lognormal or exponential. This approach does not assume any relationship between rates on adjacent branches, making it particularly suitable for datasets where evolutionary rates may change abruptly due to shifts in life history, metabolic rates, or environmental factors.

Performance Under Varying Evolutionary Conditions

Simulation studies have revealed critical insights into the performance characteristics of different clock models under controlled conditions. The strict clock model performs adequately only when the actual rate variation among lineages is minimal (σ ≤ 0.1), where σ represents the standard deviation of log rate across branches. When the true rate variation exceeds this threshold (σ > 0.1), strict clock analyses produce significantly biased estimates of node ages [24].

The uncorrelated relaxed clock model demonstrates robust performance across various levels of rate heterogeneity, effectively recovering node ages even under high rate variation (σ = 2.0). However, this robustness comes at the cost of precision, with posterior intervals on divergence times becoming substantially wider compared to strict clock analyses, particularly when rate variation is pronounced [24]. This trade-off between accuracy and precision represents a fundamental consideration in model selection.

Autocorrelated models show intermediate performance characteristics, performing well under moderate rate variation but struggling when rates evolve according to an uncorrelated process. Notably, no single method demonstrates perfect robustness when the assumed model of lineage rate change mismatches the actual process governing rate evolution, highlighting the importance of accurate model specification [25].

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of Clock Models Under Different Levels of Rate Variation

| Clock Model | Low Rate Variation (σ ≤ 0.1) | High Rate Variation (σ > 0.1) | Posterior Interval Width |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strict Clock | Accurate estimates | Biased estimates | Narrowest intervals |

| Uncorrelated Relaxed Clock | Accurate estimates | Accurate estimates | Wider intervals, increases with σ |

| Autocorrelated Relaxed Clock | Accurate estimates | Variable performance depending on correlation | Intermediate intervals |

Bayesian Frameworks for Clock Modeling

Statistical Foundations

Bayesian relaxed clock analysis employs Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithms to approximate the joint posterior distribution of phylogenetic trees, divergence times, and evolutionary rate parameters. The fundamental Bayesian equation for these analyses can be expressed as:

p(g,r,Φ|D) = [p(D|g,r,Φ) × p(r) × p(g) × p(Φ)] / p(D)

Where g represents the time tree with divergence times, r denotes the branch-specific rates, Φ encompasses additional evolutionary parameters such as substitution model parameters, and D represents the sequence alignment. The term p(r) constitutes the relaxed clock prior that governs how rates vary across branches, while p(g) includes the tree process prior and calibration densities [26].

A significant computational advancement in this domain is the development of operators that maintain constant genetic distances while proposing changes to rates and times. These operators recognize that the phylogenetic likelihood remains unchanged when the product of rate and time (the genetic distance) is held constant for reversible substitution models. This approach improves MCMC mixing efficiency, particularly for large datasets, by exploring the correlated parameter space of rates and times more effectively [26].

Implementation in Software Packages

Multiple software packages implement Bayesian relaxed clock methods with varying algorithmic strategies:

BEAST2 employs an uncorrelated relaxed clock model where rates for each branch are independently drawn from a lognormal distribution. The package utilizes various proposal mechanisms, including the recently developed Constant Distance operator, which simultaneously modifies node times and adjacent branch rates while preserving implied genetic distances. This approach has demonstrated up to half an order of magnitude improvement in effective samples per hour for large datasets [26].

MCMCTree, part of the PAML package, implements both correlated and uncorrelated relaxed clock models through an approximate likelihood framework. The program uses a multivariate normal distribution to approximate the likelihood surface, enabling computationally efficient dating of large phylogenies.

RevBayes provides a modular platform for specifying complex relaxed clock models, including both uncorrelated and autocorrelated approaches. The implementation allows for tight integration with fossil calibration models through its graphical model framework [27].

Table 2: Bayesian Molecular Dating Software and Their Features

| Software | Relaxed Clock Models | Calibration Treatment | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| BEAST2 | Uncorrelated (lognormal, exponential) | User-specified priors on nodes | Constant Distance operator, Bayesian model averaging |

| MCMCTree | Correlated, Uncorrelated | Soft bounds, skewed distributions | Approximate likelihood, large phylogeny capability |

| RevBayes | Correlated, Uncorrelated | Direct fossil incorporation | Modular model specification, fossilized birth-death |

| MultiDivTime | Correlated | Minimal and maximal bounds | Autocorrelated rate model, posterior time prediction |

Fossil Calibrations: Strategies and Uncertainties

Calibration Design and Implementation

Fossil calibrations represent the crucial link between molecular sequence divergence and geological time, serving as the ultimate source of absolute time information in molecular dating analyses. In Bayesian frameworks, fossil evidence is typically incorporated through prior distributions on the ages of specific nodes, with careful consideration of the non-uniform nature of fossil preservation and taxonomic uncertainty.

The translated lognormal distribution has emerged as a widely used calibration prior, as its shape effectively captures paleontological realities: a hard minimum bound representing the oldest confidently dated fossil, a peak probability near the mean age of the oldest fossil, and a soft maximum bound that allows for increasingly older (but less probable) dates to account for gaps in the fossil record [28]. Alternatively, normal distributions with soft bounds provide symmetrical uncertainty around a calibration point, while hard-bound uniform distributions may be employed when testing the compatibility of multiple calibrations.

A critical practice involves comparing user-specified priors with the effective joint priors produced by the dating software, as complex interactions between multiple calibration priors and tree process priors can result in marginal priors that differ substantially from the original specifications. This evaluation is typically performed by running MCMC analyses without sequence data, allowing researchers to identify and correct unintended prior configurations [29].

Impact of Calibration Scheme on Accuracy

Empirical and simulation studies have demonstrated that both the number and placement of fossil calibrations significantly impact the accuracy and precision of divergence time estimates. Analyses incorporating multiple well-distributed calibrations generally produce more reliable estimates than those relying on a single or few calibration points. Deeper calibrations (closer to the root) tend to provide more accurate rate and time estimates compared to shallow calibrations, as they encompass a greater proportion of the total evolutionary history represented in the phylogeny [30].

The practice of treating calibrations as either correct or incorrect represents an oversimplification; Bayesian methods naturally accommodate calibration quality as existing on a continuum from highly accurate to poor. When multiple candidate calibrations are included in an analysis, the posterior distribution can be used to evaluate their relative accuracy—accurate calibrations will show posterior estimates that reflect the prior, while poor calibrations will demonstrate posterior estimates forced away from the prior [28].

Notably, the sensitivity of time estimates to calibration choice varies with evolutionary conditions. Under low among-lineage rate variation, different calibration schemes may produce concordant estimates, while the same calibrations under high rate variation may yield substantially divergent results. This highlights the complex interplay between rate model specification and calibration implementation in molecular dating [30].

Experimental Validation and Protocol Design

Simulation-Based Evaluation

Computer simulation represents a powerful approach for validating molecular dating methods, as it permits direct comparison of estimated parameters with known true values. Well-designed simulation studies typically incorporate naturally derived evolutionary parameters, including variation in sequence length, evolutionary rate, GC content, and transition-transversion ratios drawn from empirical datasets [25].

A well-calibrated simulation study follows a three-stage process: (1) parameters and trees are repeatedly sampled from the prior distributions of the full model; (2) sequence alignments are simulated using these parameters under either autocorrelated or uncorrelated rate change models; (3) the same models are used to infer divergence times from the simulated alignments, with recovery of true parameter values indicating proper implementation [26]. Such studies have demonstrated that when the assumed model of lineage rate change matches the simulation model, Bayesian methods produce accurate time estimates with appropriate coverage probabilities (95% credibility intervals contain the true value in ≥95% of simulations) [25].

Figure 1: Workflow for validating molecular clock methods using computer simulation. The process evaluates method performance under different rate variation models.

Empirical Validation with Known Fossil Records

Empirical validation of relaxed clock methods utilizes groups with extensive fossil records to compare molecular date estimates with paleontological evidence. This approach tests the method's ability to recover known divergence times outside the set of calibrations, providing a real-world assessment of accuracy. The protocol involves:

Calibration Selection: Identify multiple well-constrained fossil calibrations representing minimum node ages with carefully justified maximum bounds based on comprehensive fossil evidence.

Cross-Validation: Systematically exclude each calibration in turn while using the remaining calibrations to estimate its age, comparing molecular estimates with the known fossil evidence [28].

Model Comparison: Calculate marginal likelihoods or use information criteria to compare the fit of different clock models (strict, uncorrelated, autocorrelated) to the empirical data.

Sensitivity Analysis: Evaluate the impact of different calibration priors (lognormal, normal, uniform) on posterior time estimates to assess robustness to prior specification.

This approach was effectively applied in testing proposed standard calibrations within vertebrates, demonstrating that a bird-crocodile calibration (~247 Mya) appeared accurate, while a bird-lizard calibration (~255 Mya) was substantially too recent [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Successful implementation of Bayesian relaxed clock analyses requires both biological and computational resources. The following table outlines key components of the molecular dating toolkit:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Bayesian Molecular Dating

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Markers | RAG-1, c-mos, cyt b, COI | Provide phylogenetic signal across appropriate evolutionary timescales |

| Fossil Specimens | Hesperocyon gregarius (caniforms) | Node calibration with minimum age constraints |

| Bayesian Software | BEAST2, MCMCTree, RevBayes, MultiDivTime | Implement relaxed clock models and MCMC sampling |

| Analytical Tools | Tracer, TreeAnnotator | Assess MCMC convergence and summarize posterior distributions |

| Sequence Management | GenBank, BOLD | Source comparative sequence data for phylogenetic analysis |

Method Selection Guide

Choosing appropriate clock models and calibration strategies depends on specific dataset characteristics and research questions. The following decision framework supports appropriate method selection:

For shallow phylogenies with recent divergence times (e.g., intraspecific variation or closely related species), strict clock models often perform well due to limited expected rate variation among lineages. The likelihood ratio test provides guidance, though it has limited power to detect low levels of rate variation (σ = 0.01-0.1) [24].

For deeper phylogenetic scales with substantial taxonomic diversity, uncorrelated relaxed clock models generally offer the most robust performance across different patterns of rate heterogeneity. These models accommodate both gradual and abrupt rate changes without assuming correlation between adjacent branches.

When fossil information is abundant, incorporating multiple calibrations across the phylogeny improves accuracy by reducing the average distance between calibrated and uncalibrated nodes. For data-poor groups with limited fossils, careful selection of a single deep calibration with appropriately justified bounds becomes critical.

Figure 2: Decision framework for selecting appropriate clock models and calibration strategies based on dataset characteristics.