From Atoms to Action: How Newton's Equations Power Molecular Dynamics in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the central role of Newton's equations of motion in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development.

From Atoms to Action: How Newton's Equations Power Molecular Dynamics in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the central role of Newton's equations of motion in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development. It covers the foundational physics, from the basic F=ma principle to its application in calculating atomic trajectories. The article delves into core numerical integration methods like the Verlet algorithm, explores the wide-ranging applications in studying biomolecules and drug binding, and addresses current limitations and validation techniques. By synthesizing foundational concepts with cutting-edge methodological advances, this review serves as a guide for leveraging MD simulations to accelerate pharmaceutical research.

The Physics Behind the Simulation: From Newton's Laws to Atomic Motion

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation is a powerful computational technique that predicts the time-dependent behavior of molecular systems. The method is grounded squarely in classical mechanics, providing an atomic-resolution "movie" of molecular processes by applying Newton's second law of motion to each atom in the system. The core principle is elegantly simple: given the initial positions and velocities of all atoms, and a model for the forces acting upon them, one can numerically integrate Newton's equations to simulate atomic motion over time. This approach has become indispensable across numerous fields, from drug discovery and neuroscience to nanomaterial design and energy research, enabling researchers to investigate processes that are often beyond the reach of experimental techniques [1] [2] [3].

The impact of MD simulations in molecular biology and drug discovery has expanded dramatically in recent years [3]. These simulations capture protein behavior and other biomolecular processes in full atomic detail and at femtosecond temporal resolution, revealing mechanisms of conformational change, ligand binding, and molecular recognition. The technique has moved from specialized supercomputing centers to broader accessibility due to improvements in hardware and software, making it an increasingly valuable tool for interpreting experimental results and guiding further experimental work [3].

The Mathematical Core: From Force to Motion

The Fundamental Equations

At the heart of every MD simulation lies Newton's second law, F = ma, applied to each atom i in the system. For a molecular geometry composed of N atoms, this relationship can be expressed for each atom as [4]:

$$ Fi = mi \frac{\partial^2r_i}{\partial t^2} $$

where:

- $F_i$ represents the force acting on the i-th atom

- $m_i$ is the mass of the atom

- $r_i$ is the atomic position vector

- $t$ is time

The force is also equal to the negative gradient of the potential energy function V that describes the interatomic interactions [4]:

$$ Fi = -\frac{\partial V}{\partial ri} $$

Combining these equations yields the fundamental MD equation of motion:

$$ mi \frac{\partial^2ri}{\partial t^2} = -\frac{\partial V}{\partial r_i} $$

The analytical solution to these equations is not obtainable for systems composed of more than two atoms. Therefore, MD employs numerical integration methods to solve these equations step-by-step, advancing the system through small, finite time increments [4].

The Force Field: Calculating Atomic Forces

The potential energy V is described by a molecular mechanics force field, which is fit to quantum mechanical calculations and experimental measurements [2] [3]. Several force fields are commonly used, including AMBER, CHARMM, and GROMOS [2]. These mathematical models approximate the potential energy of a molecular system as a function of its atomic coordinates, typically consisting of the following components [2]:

- Bonded terms describing interactions between connected atoms, modeled with simple virtual springs

- Angle terms capturing the energy associated with bending between three connected atoms

- Dihedral terms describing rotations about chemical bonds using sinusoidal functions

- Non-bonded terms accounting for van der Waals interactions and electrostatic interactions

Table 1: Components of a Classical Molecular Mechanics Force Field

| Energy Component | Physical Basis | Mathematical Form | Parameters Required |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Stretching | Vibration of covalent bonds | Harmonic oscillator: $E{bond} = \frac{1}{2}kb(r - r_0)^2$ | Equilibrium bond length ($r0$), force constant ($kb$) |

| Angle Bending | Bending between three connected atoms | Harmonic function: $E{angle} = \frac{1}{2}kθ(θ - θ_0)^2$ | Equilibrium angle ($θ0$), force constant ($kθ$) |

| Dihedral/Torsional | Rotation around chemical bonds | Periodic function: $E{dihedral} = kφ[1 + cos(nφ - δ)]$ | Barrier height ($k_φ$), periodicity ($n$), phase ($δ$) |

| van der Waals | Short-range electron cloud repulsion and dispersion | Lennard-Jones 6-12 potential: $E_{vdW} = 4ε[(σ/r)^{12} - (σ/r)^6]$ | Well depth ($ε$), collision diameter ($σ$) |

| Electrostatic | Interaction between partial atomic charges | Coulomb's law: $E{elec} = (qiqj)/(4πε0r_{ij})$ | Partial atomic charges ($qi$, $qj$) |

Numerical Integration: The MD Algorithm in Practice

The Finite Difference Approach

MD simulations use a class of numerical methods named finite difference methods to integrate the equations of motion [4]. The integration is divided into many small finite time steps δt, typically on the order of femtoseconds (10⁻¹⁵ seconds), to properly capture the fastest molecular motions while maintaining numerical stability [4]. The general MD algorithm proceeds as follows [4]:

- Initial conditions: Provide an initial configuration of the system consisting of the positions $ri$ and velocities $vi$ of the atoms at time t

- Compute forces: Calculate the forces acting on each atom from the potential energy function: $Fi = -\frac{\partial V}{\partial ri}$

- Integrate equations of motion: Update atomic positions and velocities by solving Newton's equations: $ai = \frac{Fi}{m_i}$

- Iteration: Repeat steps 2 and 3 for the desired number of time steps

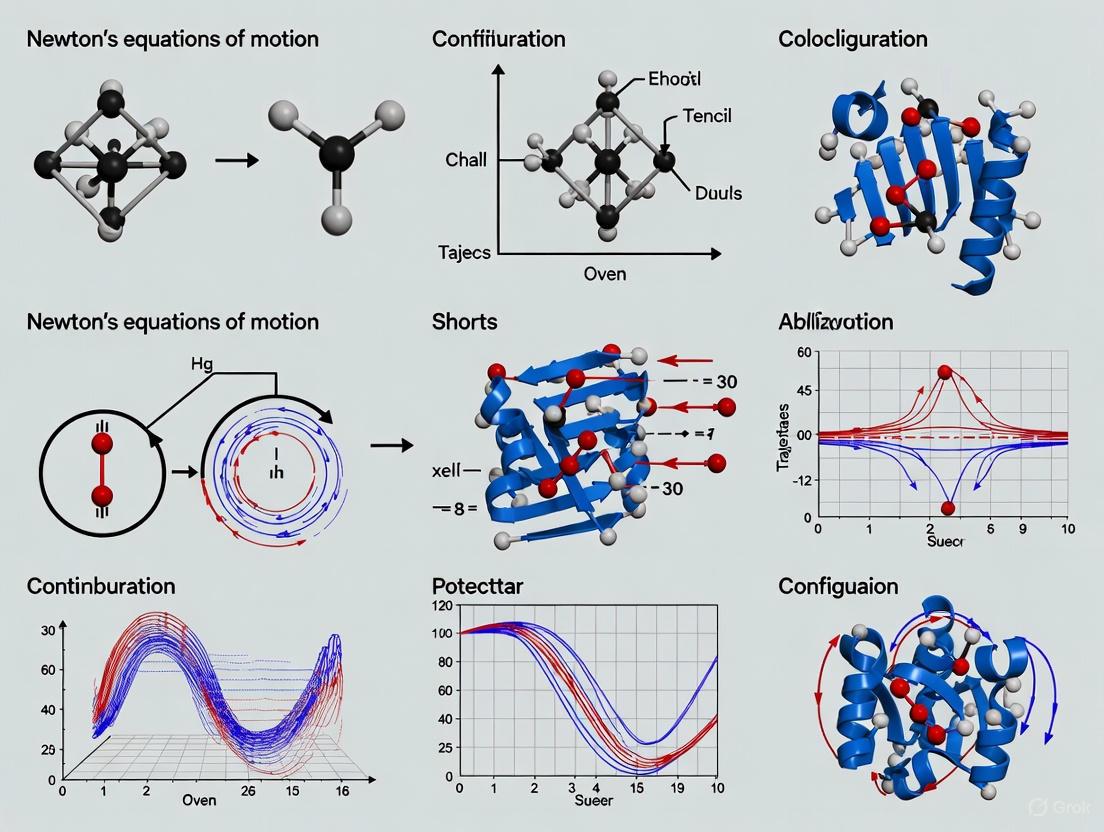

The following diagram illustrates this core workflow and the key algorithms involved:

Common Integration Algorithms

The majority of integration techniques approximate future atomic positions using Taylor expansions. The most widely used is the Verlet algorithm, which calculates new positions using[current and past atomic positions plus acceleration [4]:

$$ r(t + \delta t) = 2r(t) - r(t- \delta t) + \delta t^2 a(t) $$

While computationally stable, the basic Verlet algorithm does not incorporate velocities explicitly. To address this limitation, several variations have been developed, with the Velocity Verlet method being one of the most widely used [4]:

$$ r(t + \delta t) = r(t) + \delta t v(t) + \frac{1}{2} \delta t^2 a(t) $$ $$ v(t+ \delta t) = v(t) + \frac{1}{2}\delta t[a(t) + a(t + \delta t)] $$

Another common alternative is the Leapfrog algorithm, which is based on the current position and velocity at half-time steps [4]:

$$ v\left(t+ \frac{1}{2}\delta t\right) = v\left(t- \frac{1}{2}\delta t\right) +\delta t a(t) $$ $$ r(t + \delta t) = r(t) + \delta t v \left(t + \frac{1}{2}\delta t \right) $$

Table 2: Comparison of Major MD Integration Algorithms

| Algorithm | Key Equations | Advantages | Disadvantages | Stored Variables per Step |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Verlet | $r(t+δt) = 2r(t) - r(t-δt) + δt^2a(t)$ | Numerically stable, time-reversible | Velocities not explicit, not self-starting | $r(t)$, $r(t-δt)$, $a(t)$ |

| Velocity Verlet | $r(t+δt) = r(t) + δt v(t) + \frac{1}{2}δt^2a(t)$ $v(t+δt) = v(t) + \frac{1}{2}δt[a(t) + a(t+δt)]$ | Positions, velocities and accelerations synchronized | Slightly more complex implementation | $r(t)$, $v(t)$, $a(t)$ |

| Leapfrog | $v(t+\frac{1}{2}δt) = v(t-\frac{1}{2}δt) + δt a(t)$ $r(t+δt) = r(t) + δt v(t+\frac{1}{2}δt)$ | Computationally efficient, natural for Coulomb systems | Positions and velocities not synchronized at same time | $r(t)$, $v(t+0.5δt)$, $a(t)$ |

Advanced Integration: Multi-Time-Step Methods and Machine Learning Acceleration

Multi-Time-Step Integration

Traditional MD simulations use a single, small time step (typically 1-2 fs) to resolve the fastest motions (bond vibrations). Multi-Time-Step methods such as the Reference System Propagator Algorithm (RESPA) exploit the separation of timescales between different force components to improve computational efficiency [5]. These methods integrate fast-changing forces with a small time step and slow-changing ones with a larger time step, reducing the number of expensive force evaluations [5].

Recent advances combine MTS with neural network potentials (NNPs). A dual-level neural network MTS strategy uses a cheaper, faster model (e.g., with a 3.5 Å cutoff) to capture fast-varying bonded interactions, while a more accurate but computationally expensive foundation model (e.g., FeNNix-Bio1 with an 11 Å cutoff) is evaluated less frequently to correct the dynamics [5]. This approach can yield 2.7- to 4-fold speedups in large solvated proteins while preserving accuracy [5].

Machine Learning-Enhanced Potentials

Machine learning has revolutionized MD through the development of NNPs that offer near-quantum mechanical accuracy at a fraction of the computational cost of ab initio methods [5]. Foundation models now cover complete application areas of MD, from materials science to drug design [5]. Knowledge distillation procedures can create smaller, faster models that are trained on data labeled by a larger reference model, enabling efficient deployment in multi-time-step schemes [5].

The following diagram illustrates this advanced neural network MTS approach:

Experimental Protocol for Standard MD Simulation

For researchers implementing MD simulations, the following protocol outlines the key steps:

System Preparation

- Obtain initial atomic coordinates from experimental (X-ray, NMR, cryo-EM) or homology modeling data [2] [3]

- Place the system in a simulation box with appropriate periodic boundary conditions

- Solvate the system with water molecules and add ions to achieve physiological concentration and neutralize charge

Energy Minimization

- Perform steepest descent or conjugate gradient minimization to remove bad atomic contacts and high-energy configurations

- Use tolerance criteria of 100-1000 kJ/mol/nm for maximum force

System Equilibration

- Conduct equilibration in NVT (constant Number, Volume, Temperature) ensemble for 50-500 ps

- Follow with NPT (constant Number, Pressure, Temperature) ensemble for 50-500 ps

- Use Berendsen or Nosé-Hoover thermostats and barostats to maintain conditions

Production Simulation

- Run extended simulation (nanoseconds to microseconds) with a 1-2 fs time step

- Use Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) for long-range electrostatics

- Apply constraints to bonds involving hydrogen atoms (LINCS or SHAKE algorithms)

- Save trajectory frames every 1-100 ps for analysis

Trajectory Analysis

- Calculate root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) for structural stability

- Compute root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) for residue flexibility

- Analyze hydrogen bonding, solvent accessibility, and other interaction patterns

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Molecular Dynamics Simulations

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simulation Software | AMBER [2], CHARMM [2], GROMACS [6], NAMD [2], Tinker-HP [5] | Core MD engines with various force fields | Biomolecular simulations, nanomaterials, drug discovery |

| Force Fields | AMBER [2], CHARMM [2], GROMOS [2], Machine Learning Potentials (FeNNix) [5] | Define interatomic interactions and potential energy | System-dependent; determines simulation accuracy |

| Hardware Platforms | GPU Workstations (NVIDIA RTX 4090/6000 Ada) [6], Specialized Hardware (Anton) [2], High-Performance Computing Clusters [1] | Provide computational power for force calculations | Large systems, long timescales, high-throughput screening |

| Analysis Tools | MDTraj, VMD, PyMOL, GROMACS analysis suite | Process trajectories, calculate properties, visualize results | Essential for all simulation types to extract meaningful insights |

| Parameterization Tools | GAUSSIAN, ANTECHAMBER, MATCH, CGenFF | Generate missing force field parameters | Novel molecules, drug-like compounds, non-standard residues |

Hardware Considerations for Optimal Performance

Selecting appropriate hardware is crucial for efficient MD simulations. Key considerations include [6]:

- CPUs: Mid-tier workstation CPUs with balanced base and boost clock speeds (AMD Threadripper PRO 5995WX) often provide better performance than extreme core-count processors for many MD workloads

- GPUs: NVIDIA GPUs (RTX 4090, RTX 6000 Ada, RTX 5000 Ada) dramatically accelerate simulations, with performance scaling with CUDA core count and memory bandwidth

- Memory: Systems should be equipped with sufficient RAM (typically 128GB-512GB) to handle large molecular systems and multiple simultaneous jobs

- Multi-GPU setups: Configurations with multiple GPUs can dramatically enhance computational efficiency for software like AMBER, GROMACS, and NAMD

Table 4: Hardware Recommendations for Molecular Dynamics Simulations (2025)

| Hardware Component | Recommended Options | Key Specifications | Target Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Workstation CPU | AMD Threadripper PRO 5995WX | 64 cores, 2.7-4.35 GHz clock speed | Balanced performance for MD workloads [6] |

| Data Center CPU | AMD EPYC, Intel Xeon Scalable | High core count, robust multi-threading | Large systems, multiple parallel simulations [6] |

| High-End GPU | NVIDIA RTX 6000 Ada | 18,176 CUDA cores, 48 GB GDDR6 VRAM | Memory-intensive simulations, large complexes [6] |

| Cost-Effective GPU | NVIDIA RTX 4090 | 16,384 CUDA cores, 24 GB GDDR6X VRAM | General molecular dynamics, smaller systems [6] |

| Balanced GPU | NVIDIA RTX 5000 Ada | 10,752 CUDA cores, 24 GB GDDR6 VRAM | Standard simulations with budget constraints [6] |

| System RAM | 256-512 GB DDR4/DDR5 | High-speed, error-correcting code | Handling large systems and multiple jobs [6] |

Applications and Future Directions

The application of F=ma at the atomic scale has enabled groundbreaking research across diverse fields. In drug discovery, MD simulations help identify cryptic and allosteric binding sites, enhance virtual screening methodologies, and directly predict small-molecule binding energies [2]. In neuroscience, simulations study proteins critical to neuronal signaling and assist in developing drugs targeting the nervous system [3]. In nanomaterials design, MD enables the prediction of fundamental material properties including thermal conductivity, mechanical strength, and surface behavior [1]. In energy research, MD simulations help design and optimize polymers for oil displacement, observing polymer-oil interactions at the atomic scale [7].

Despite its power, MD faces challenges including high computational costs, force field approximations, and limited time scales [1] [2]. Current simulations are typically limited to millionths of a second, though specialized hardware can extend this to milliseconds for some systems [2] [3]. Force fields continue to improve but still generally ignore electronic polarization and quantum effects [2]. Future advances will likely focus on multiscale modeling, integration with artificial intelligence, improved polarizable force fields, and continued hardware acceleration [1] [7] [5].

The core principle of applying F=ma to every atom remains the foundation upon which these advances are built, connecting theoretical and experimental efforts to foster innovation across scientific disciplines. As MD simulations continue to evolve, they will undoubtedly play an increasingly critical role in scientific discovery and technological innovation.

This technical guide examines the fundamental relationship between potential energy and atomic acceleration within the framework of Newton's equations of motion, a cornerstone of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. MD serves as a powerful computational technique for analyzing the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time, providing critical insights for drug development and materials science. By numerically solving Newton's equations for systems of interacting particles, researchers can simulate dynamic evolution of molecular systems that would be impossible to observe directly. This whitepaper details the theoretical foundation, numerical methodologies, and practical implementation of these principles, with particular emphasis on their application in pharmaceutical research and development.

Molecular Dynamics (MD) is a computer simulation method for analyzing the physical movements of atoms and molecules, allowing them to interact for a fixed period to provide a view of the dynamic "evolution" of the system [8]. In its most common form, trajectories of atoms and molecules are determined by numerically solving Newton's equations of motion for a system of interacting particles, where forces between particles and their potential energies are calculated using interatomic potentials or molecular mechanical force fields [8]. This approach has become indispensable in chemical physics, materials science, and biophysics because molecular systems typically consist of vast numbers of particles, making it impossible to determine properties of such complex systems analytically [8].

The significance of MD simulations in modern drug development cannot be overstated. Since the 1970s, MD has been commonly used in biochemistry and biophysics for refining 3-dimensional structures of proteins and other macromolecules based on experimental constraints from X-ray crystallography or NMR spectroscopy [8]. More recently, MD simulation has been reported for pharmacophore development and drug design, helping identify compounds that complement biological receptors while causing minimal disruption to the conformation and flexibility of active sites [8].

Theoretical Foundation: From Potential Energy to Atomic Acceleration

The Potential Energy Surface

Potential energy is the energy stored in a system due to the position, composition, or arrangement of its components, often associated with forces of attraction and repulsion between objects [9] [10]. On a molecular level, potential energy is stored in various interactions: covalent bonds, electrostatic forces, and nuclear forces [9]. The potential energy of a molecular system arises from the complex interplay of these interactions, creating a multidimensional potential energy surface that dictates how the system will evolve over time.

The mathematical representation of potential energy varies depending on the system and the interactions being modeled. For instance, the potential energy between two charged particles follows Coulomb's Law:

[ E = \frac{q1 q2}{4\pi \epsilon_o r} ]

where (q1) and (q2) are the charges, (r) is the distance between them, and (\epsilon_0) is the permittivity of free space [9]. This electrostatic potential energy plays a crucial role in molecular interactions, particularly in biological systems where charged groups mediate protein-ligand binding and structural stability.

Newton's Equations in Molecular Dynamics

The connection between potential energy and atomic motion is established through Newton's second law of motion. For a molecular system composed of N atoms, the position of each atom (i) at time (t) can be represented as:

[ Fi = mi \frac{\partial^2r_i}{\partial t^2} ]

where (Fi) represents the force acting on the (i)-th atom, (mi) is its mass, and (r_i) is its position [4]. The force is also equal to the negative derivative of the potential energy (V) with respect to position:

[ Fi = -\frac{\partial V}{\partial ri} ]

This fundamental relationship provides the bridge between the static potential energy landscape and the dynamic motion of atoms. The acceleration of each atom can then be determined by combining these equations:

[ ai = \frac{Fi}{mi} = -\frac{1}{mi} \frac{\partial V}{\partial r_i} ]

This formulation makes explicit the direct relationship between the spatial gradient of the potential energy and the resulting acceleration of each atom in the system [4].

Table 1: Fundamental Equations Governing Molecular Dynamics

| Concept | Mathematical Expression | Description | Application in MD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Newton's Second Law | (Fi = mi a_i) | Relates force, mass, and acceleration | Foundation for atomic motion |

| Force from Potential | (Fi = -\frac{\partial V}{\partial ri}) | Defines force as potential energy gradient | Connects energy surface to atomic forces |

| Atomic Acceleration | (ai = -\frac{1}{mi} \frac{\partial V}{\partial r_i}) | Determines acceleration from potential | Directly computes motion from energy |

| Coulomb Potential | (E = \frac{q1 q2}{4\pi \epsilon_o r}) | Electrostatic interaction energy | Models charged atomic interactions |

Numerical Integration Methods in Molecular Dynamics

The Finite Difference Approach

The analytical solution to Newton's equations of motion is not obtainable for systems composed of more than two atoms [4]. Therefore, MD simulations employ numerical integration approaches, primarily the finite difference method. The core idea behind this class of methods is dividing the integration into many small finite time steps (\delta t) [4]. Since molecular motions occur on the scale of (10^{-14}) seconds, a typical (\delta t) is on the order of femtoseconds ((10^{-15}s)) to properly resolve the fastest atomic vibrations [4] [8].

At each time step, the equations of motion are solved simultaneously for all N atoms in the system. The forces acting on each atom ((F1,\dots,FN)) at time (t) are determined from the potential energy function, and from these forces, the acceleration is derived [4]. Given the molecular position, velocity, and acceleration at time (t), the integration algorithm predicts the position and velocity at the following time step ((t+\delta t)). This procedure is applied iteratively for many steps, generating a trajectory that specifies how atomic positions and velocities vary with time [4].

Common Integration Algorithms

Several integration algorithms have been developed for MD simulations, each with distinct advantages and limitations. The most widely used is the Verlet algorithm, which uses current positions (r(t)), accelerations (a(t)), and positions from the previous step (r(t-\delta t)) to calculate new positions (r(t+\delta t)) [4]. The basic Verlet algorithm equation is:

[ r(t + \delta t) = 2r(t) - r(t-\delta t) + \delta t^2 a(t) ]

While computationally efficient, the basic Verlet algorithm has two main disadvantages: it does not incorporate velocities explicitly (requiring additional calculations), and it is not self-starting (requiring special handling at (t=0)) [4].

To overcome these limitations, several variants have been developed:

Velocity Verlet Algorithm: This method explicitly incorporates velocities and is one of the most widely used in MD simulation [4]. It uses the following equations: [ r(t + \delta t) = r(t) + \delta t v(t) + \frac{1}{2} \delta t^2 a(t) ] [ v(t+ \delta t) = v(t) + \frac{1}{2}\delta t[a(t) + a(t + \delta t)] ]

Leapfrog Algorithm: This method uses a half-step offset for velocities [4]: [ v\left(t+ \frac{1}{2}\delta t\right) = v\left(t- \frac{1}{2}\delta t\right) +\delta ta(t) ] [ r(t + \delta t) = r(t) + \delta t v\left(t + \frac{1}{2}\delta t \right) ]

Molecular Dynamics Simulation Workflow

Table 2: Comparison of Molecular Dynamics Integration Algorithms

| Algorithm | Key Equations | Advantages | Limitations | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Verlet | (r(t+\delta t) = 2r(t) - r(t-\delta t) + \delta t^2 a(t)) | Time-reversible, good energy conservation | No explicit velocities, not self-starting | General purpose MD |

| Velocity Verlet | (r(t+\delta t) = r(t) + \delta t v(t) + \frac{1}{2} \delta t^2 a(t)) (v(t+\delta t) = v(t) + \frac{1}{2}\delta t[a(t) + a(t+\delta t)]) | Numerically stable, explicit velocities | Slightly more computationally expensive | Most modern MD simulations |

| Leapfrog | (v(t+\frac{1}{2}\delta t) = v(t-\frac{1}{2}\delta t) + \delta t a(t)) (r(t+\delta t) = r(t) + \delta t v(t+\frac{1}{2}\delta t)) | Computationally efficient | Non-synchronous position/velocity updates | Specialized applications |

Practical Implementation in Drug Development

Force Fields and Parameterization

The accuracy of MD simulations in pharmaceutical applications critically depends on the quality of the force field parameters used to describe interatomic interactions [8]. Force fields mathematically represent the potential energy surface as a sum of various contributions:

[ V{\text{total}} = V{\text{bond}} + V{\text{angle}} + V{\text{torsion}} + V{\text{electrostatic}} + V{\text{van der Waals}} ]

Each term captures a specific type of molecular interaction, with parameters derived from both quantum mechanical calculations and experimental data. Modern force fields for biomolecular simulations include CHARMM, AMBER, and OPLS, each with specific parameterization for proteins, nucleic acids, lipids, and small molecules relevant to drug design.

Recent advances in MD simulations have enabled their application in structure-based drug discovery. For example, Pinto et al. implemented MD simulations of Bcl-xL complexes to calculate average positions of critical amino acids involved in ligand binding [8]. Similarly, Carlson et al. used MD simulations to identify compounds that complement a receptor while causing minimal disruption to the conformation and flexibility of the active site [8].

Simulation Protocols and System Setup

Proper setup of MD simulations requires careful attention to multiple technical considerations. The design must account for available computational power while ensuring the simulation spans relevant time scales for the biological process being studied [8]. Most scientific publications about protein and DNA dynamics use simulations spanning nanoseconds ((10^{-9}) s) to microseconds ((10^{-6}) s), requiring several CPU-days to CPU-years of computation time [8].

Key considerations in simulation setup include:

- Solvation: Choice between explicit solvent molecules (more accurate but computationally expensive) and implicit solvent models (faster but less accurate) [8]

- Periodic Boundary Conditions: Simulating a small system within a repeating unit cell to minimize edge effects

- Temperature and Pressure Control: Using thermostats and barostats to maintain physiological conditions

- Constraint Algorithms: Methods like SHAKE to fix the fastest vibrational modes (e.g., hydrogen bonds), enabling larger time steps [8]

Integration Algorithm Comparison

Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Dynamics

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Molecular Dynamics Simulations

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application in Drug Development |

|---|---|---|---|

| Force Fields | CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS, GROMOS | Define potential energy functions | Parameterize drug molecules and targets |

| Simulation Software | GROMACS, NAMD, AMBER, OpenMM | Perform numerical integration of equations of motion | Run production MD simulations |

| System Preparation | CHARMM-GUI, PACKMOL, tleap | Set up simulation boxes with solvent and ions | Prepare protein-ligand systems |

| Analysis Tools | MDAnalysis, VMD, CPPTRAJ | Process trajectory data and calculate properties | Analyze binding interactions and dynamics |

| Enhanced Sampling | PLUMED, COLVARS | Accelerate rare events in simulations | Study drug binding/unbinding kinetics |

| Visualization | PyMOL, VMD, Chimera | Visualize molecular structures and trajectories | Interpret simulation results |

Analysis of Trajectory Data and Physical Properties

Extracting Physically Meaningful Information

The primary output of MD simulations is a trajectory - a series of molecular configurations at discrete time steps specifying atomic positions and velocities over time [4]. While this raw trajectory contains all simulated information, extracting physically meaningful properties requires sophisticated analysis techniques. For systems obeying the ergodic hypothesis, time averages from MD trajectories correspond to microcanonical ensemble averages, allowing determination of macroscopic thermodynamic properties [8].

Common analyses of MD trajectories include:

- Structural Stability: Root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of atomic positions to assess conformational stability

- Flexibility: Root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) of atomic positions to identify flexible regions

- Interaction Analysis: Hydrogen bonding, salt bridges, and hydrophobic contacts to characterize binding

- Dynamic Cross-Correlation: Identify correlated motions between different parts of a molecule

- Free Energy Calculations: Potential of Mean Force (PMF) to quantify binding affinities

Validation and Correlation with Experimental Data

MD-derived predictions must be validated through comparison with experimental data. A popular validation method is comparison with NMR spectroscopy, which can provide information about molecular dynamics on similar timescales [8]. MD-derived structure predictions can also be tested through community-wide experiments such as the Critical Assessment of Protein Structure Prediction (CASP) [8].

Recent improvements in computational resources permitting more and longer MD trajectories, combined with modern improvements in force field parameters, have yielded significant improvements in both structure prediction and homology model refinement [8]. However, many researchers still identify force field parameters as a key area for further development, particularly for simulating complex biological processes relevant to drug action [8].

Table 4: Quantitative Parameters in Typical MD Simulations of Protein-Ligand Systems

| Parameter | Typical Range/Value | Impact on Simulation | Considerations for Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time Step (δt) | 1-2 femtoseconds | Determines maximum bond vibrations | Constrained by hydrogen vibration periods |

| Simulation Duration | Nanoseconds to microseconds | Determines observable processes | Must match biological process kinetics |

| System Size | 10,000 to 1,000,000 atoms | Impacts computational cost | Must include complete binding site |

| Temperature | 300-310 K (physiological) | Affects conformational sampling | Critical for realistic biomolecular behavior |

| Pressure | 1 atm (physiological) | Affects system density | Important for binding volume calculations |

| Non-bonded Cutoff | 8-12 Å | Balances accuracy and speed | Affects long-range electrostatic forces |

The relationship between potential energy and atomic acceleration, as formalized through Newton's equations of motion, provides the fundamental theoretical framework for molecular dynamics simulations. The numerical integration of these equations enables researchers to bridge the gap between the static potential energy surface and the dynamic evolution of molecular systems over time. For drug development professionals, MD simulations offer powerful tools for studying protein-ligand interactions, predicting binding affinities, and understanding the structural dynamics of therapeutic targets at atomic resolution.

While current MD simulations face limitations in accuracy and timescale, ongoing advances in computational power, force field development, and enhanced sampling algorithms continue to expand their applicability in pharmaceutical research. The integration of MD with experimental structural biology and biophysical techniques provides a robust platform for structure-based drug design, potentially reducing the time and cost associated with empirical screening approaches. As these methods continue to mature, molecular dynamics simulations are poised to play an increasingly central role in rational drug development.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation has become an indispensable tool in fields ranging from structural biology to drug design and materials science. This computational technique describes the time evolution of molecular systems by solving Newton's equations of motion for each atom. However, for any system of practical scientific interest, these equations cannot be solved through analytical methods and instead require sophisticated numerical integration approaches. This technical guide examines the fundamental mathematical and physical constraints that necessitate numerical solutions, details the primary algorithms that enable these simulations, and explores current computational frontiers where machine learning promises to overcome persistent limitations in the field.

Molecular Dynamics operates on the fundamental principle that a molecular system comprising N atoms evolves over time according to classical mechanics. At any given time t, the molecular geometry is defined by the positions of all atoms: R = (r₁, r₂, ..., r_N) [4]. The core of MD simulation involves calculating how this atomic configuration changes over time by numerically integrating Newton's second law of motion for each atom in the system:

Fᵢ = mᵢaᵢ = -∇V(rᵢ)

where Fᵢ is the force acting on atom i, mᵢ is its mass, aᵢ is its acceleration, and V(rᵢ) is the potential energy function [4] [11]. The acceleration represents the second derivative of the position with respect to time, making this a second-order differential equation that must be solved for all atoms simultaneously.

Table 1: Key Components in Newton's Equations of Motion for Molecular Systems

| Component | Symbol | Physical Meaning | Role in MD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atomic position | rᵢ | Spatial coordinates of atom i | Defines molecular geometry |

| Mass | mᵢ | Atomic mass | Determines inertial response to forces |

| Force | Fᵢ | Net force acting on atom i | Derived from potential energy gradient |

| Acceleration | aᵢ | Second derivative of position | Links forces to motion |

| Potential energy | V(rᵢ) | Energy landscape from interatomic interactions | Determines forces between atoms |

The Mathematical Intractability of Analytical Solutions

The Many-Body Problem in Molecular Systems

The fundamental challenge in solving Newton's equations for molecular systems lies in the analytical intractability of the many-body problem. For systems with simple potential energy functions and minimal degrees of freedom, closed-form analytical solutions exist. However, as noted in MD literature, "the analytical solution to the equations of motion is not obtainable for a system composed of more than two atoms" [4]. This mathematical limitation arises from several interconnected factors:

First, the potential energy function V(r) that describes interatomic interactions incorporates numerous complex components including covalent bond stretching, angle bending, torsional rotations, van der Waals forces, and electrostatic interactions. The coupled nature of these terms creates a highly nonlinear system of differential equations that cannot be decoupled for analytical treatment [12] [11].

Second, the number of equations that must be solved simultaneously scales with the system size. A modest protein-ligand complex with 10,000 atoms requires solving 30,000 coupled differential equations (three for each atom), a mathematical problem that quickly becomes insurmountable for analytical approaches [13].

Environmental Complexity and Boundary Conditions

Realistic biological systems introduce additional layers of complexity that further preclude analytical solutions. As highlighted in recent research, "cellular-scale modeling still poses numerous challenges for computational researchers" due to the crowded intracellular environment containing proteins, nucleic acids, lipids, glycans, and metabolites [14]. These systems exhibit:

- Disordered molecular structures with continuous conformational transitions

- Environment-dependent protonation states that alter electrostatic interactions

- Complex boundary conditions with multiple interfaces

- Coupling between molecular and solvent dynamics

As one researcher succinctly stated regarding analytical approaches: "Analytic integration is only possible for the simplest potentials" such as uncoupled harmonic oscillators, rigid rotors, or central potentials, which "is not at all a typical situation" for realistic molecular systems [13].

Numerical Integration Methods in Molecular Dynamics

The Finite Difference Approach

Given the mathematical intractability of analytical solutions, MD simulations rely on numerical integration methods, particularly the class of finite difference approaches [4]. The core concept involves approximating the continuous time evolution of the system as a series of discrete steps:

- Time discretization: The simulation is divided into small finite time steps (δt), typically on the order of femtoseconds (10⁻¹⁵ seconds) to properly resolve molecular vibrations [4]

- Force calculation: At each time step, forces on all atoms are computed from the potential energy gradient

- Integration: New positions and velocities are calculated using numerical approximations

- Iteration: The process repeats for thousands to millions of steps to generate trajectories

The finite difference method leverages Taylor expansions to approximate future positions based on current and previous states:

r(t+δt) = r(t) + δtv(t) + ½δt²a(t) + ⅙δt³b(t) + ⋯

where v is velocity, a is acceleration, and b is the third derivative of position [4]. This expansion forms the mathematical foundation for all MD integration algorithms.

Figure 1: Molecular Dynamics Numerical Integration Workflow. The process iterates through force calculation and numerical integration for each time step δt.

Primary Integration Algorithms

The Verlet Algorithm

The Verlet algorithm is one of the most widely used numerical integrators in MD due to its time-reversibility and stability properties [4] [15]. It derives from combining forward and backward Taylor expansions:

r(t+δt) = 2r(t) - r(t-δt) + δt²a(t) + O(δt⁴)

This formulation provides excellent numerical stability with minimal computational overhead [15]. However, it has notable limitations:

- Velocities are not explicitly incorporated and must be calculated separately

- The algorithm is not self-starting, requiring special handling at initialization

Velocity estimation in the basic Verlet algorithm uses the mean value theorem:

v(t) = [r(t+δt) - r(t-δt)] / 2δt

though this approach "generally leads to large errors" according to MD practitioners [4].

Velocity Verlet Algorithm

The Velocity Verlet algorithm addresses the limitations of the basic Verlet method by explicitly incorporating velocities at each time step [4]. The algorithm proceeds in three distinct phases:

- Position update: r(t+δt) = r(t) + δtv(t) + ½δt²a(t)

- Force calculation: Compute new acceleration a(t+δt) from updated positions

- Velocity update: v(t+δt) = v(t) + ½δt[a(t) + a(t+δt)]

This method "is one of the most widely used in MD simulation" due to its self-starting nature, explicit velocity handling, and good energy conservation properties [4].

Leapfrog Algorithm

The Leapfrog method employs a different approach by staggering the updates of positions and velocities [4]:

v(t+½δt) = v(t-½δt) + δta(t) r(t+δt) = r(t) + δtv(t+½δt)

In this scheme, "velocities and positions are mimicking two frogs jumping over each other, thus the name 'leapfrog'" [4]. While computationally efficient, this method results in non-synchronous position and velocity information, complicating the calculation of certain physical properties.

Table 2: Comparison of Primary Numerical Integrators in Molecular Dynamics

| Algorithm | Mathematical Formulation | Advantages | Limitations | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Verlet | r(t+δt) = 2r(t) - r(t-δt) + δt²a(t) | Time-reversible, Good stability | No explicit velocities, Not self-starting | General biomolecular simulations |

| Velocity Verlet | r(t+δt) = r(t) + δtv(t) + ½δt²a(t)v(t+δt) = v(t) + ½δt[a(t) + a(t+δt)] | Self-starting, Explicit velocities, Good energy conservation | Slightly more computationally intensive | Production MD, Constant temperature simulations |

| Leapfrog | v(t+½δt) = v(t-½δt) + δta(t)r(t+δt) = r(t) + δtv(t+½δt) | Computationally efficient, Good stability | Non-synchronous positions and velocities | Large-scale systems, Coarse-grained MD |

Practical Implementation and Time Step Constraints

Time Step Selection and Numerical Stability

The choice of time step (δt) represents a critical compromise between numerical stability and computational efficiency in MD simulations. Molecular motions occur across a wide range of timescales, with the fastest being bond vibrations involving hydrogen atoms (approximately 10 femtoseconds) [4] [11]. To ensure numerical stability, the time step must be small enough to resolve these fastest motions:

- Bond vibrations: ~10-15 fs period (requires δt ≈ 1 fs)

- Angle vibrations: ~20-30 fs period

- Torsional rotations: ~100 fs to picoseconds

- Protein domain motions: nanoseconds to milliseconds

As noted in MD literature, "Since molecular motions are in the range of 10⁻¹⁴ seconds, a good δt to describe them is typically in the order of femtoseconds (10⁻¹⁵ s)" [4]. Larger time steps risk numerical instability and inaccurate trajectory integration, while smaller steps increase computational cost without significant accuracy improvements.

Enhanced Sampling Techniques

To overcome the timescale limitations imposed by small time steps, researchers have developed enhanced sampling methods that effectively accelerate rare events [16]. These techniques include:

- Umbrella sampling: Applies bias potentials along reaction coordinates to improve sampling of high-energy regions [16]

- Metadynamics: Systematically fills energy basins with repulsive potentials to encourage exploration [16]

- Replica exchange MD: Runs parallel simulations at different temperatures, allowing exchanges that escape local minima [16]

- Steered MD: Applies external forces to drive systems along specific pathways [16]

These methods "are specifically designed to improve the sampling of rare events during MD simulations, which would otherwise be extremely difficult to observe within the limited timeframes that can be simulated with classical MD" [16].

Current Challenges and Computational Frontiers

Multiscale Modeling and Coarse-Graining

While all-atom MD provides atomic-level resolution, its computational cost limits applications to relatively small systems and short timescales. Coarse-grained (CG) MD addresses this limitation by "representing groups of atoms by simplified interaction sites, allowing for the modeling of larger systems and longer timescales compared to all-atom MD simulations" [16]. Popular CG approaches like the Martini model reduce computational burden by representing multiple atoms with single interaction sites, enabling simulations of cellular-scale systems [16].

Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence Integration

The integration of machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) represents the most promising frontier for overcoming current computational challenges in MD [16] [17]. ML approaches are being applied in two primary domains:

ML force fields (MLFFs): "MLFFs are enabling quantum level accuracy at classical level cost for large scale simulations of complex aqueous and interfacial systems" [17]. These methods can capture complex quantum mechanical effects without the prohibitive computational cost of ab initio MD.

ML-enhanced sampling: Machine learning techniques can identify relevant reaction coordinates and accelerate configuration space exploration, "facilitating the crossing of large reaction barriers and enabling the exploration of extensive configuration spaces" [17].

As noted in recent research, "Machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) will be crucial in these efforts, facilitating effective feature representation and linking various models for coarse-graining and back-mapping tasks" [16].

Table 3: Computational Methods for Extending MD Capabilities

| Method | Fundamental Approach | Timescale Extension | System Size Extension | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All-Atom MD | Explicit treatment of all atoms | Limited to nanoseconds-microseconds | ~10⁴-10⁶ atoms | Protein-ligand binding, Conformational changes |

| Coarse-Grained MD | Groups of atoms represented as single sites | Microseconds-milliseconds | ~10⁵-10⁸ atoms | Membrane remodeling, Large complexes |

| Enhanced Sampling | Biased potentials to accelerate rare events | Effectively milliseconds-seconds | Similar to all-atom MD | Protein folding, Drug binding/unbinding |

| Machine Learning MD | Learned force fields from quantum data | Nanoseconds-microseconds (with quantum accuracy) | ~10³-10⁵ atoms | Reactive processes, Chemical reactions |

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Computational Tools

Table 4: Essential Software and Force Fields for Molecular Dynamics Research

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| MD Simulation Software | GROMACS, AMBER, DESMOND, NAMD, LAMMPS | Numerical integration of equations of motion | Production MD simulations of biomolecular systems [18] [16] [11] |

| Force Fields | CHARMM, AMBER, GROMOS, Martini (CG) | Mathematical representation of interatomic potentials | Determining forces between atoms in specific biological contexts [18] [16] |

| Enhanced Sampling Packages | PLUMED, Colvars | Implementation of advanced sampling algorithms | Accelerating rare events and improving statistical sampling [16] |

| Quantum Chemistry Software | Gaussian, ORCA, Q-Chem | Generating reference data for force field parametrization | Developing accurate potential energy surfaces [17] |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | TensorFlow, PyTorch, SchNet | Developing neural network potentials | Creating ML force fields with quantum accuracy [17] |

Numerical methods form the essential foundation for solving Newton's equations of motion in molecular dynamics simulations of biologically relevant systems. The mathematical intractability of analytical solutions for many-body systems with complex potential energy functions necessitates the use of finite difference approaches such as the Verlet algorithm and its variants. While these numerical integrators enable the simulation of molecular behavior across femtosecond to microsecond timescales, they impose inherent limitations in terms of time step constraints and sampling efficiency. Current research frontiers focus on multiscale modeling and machine learning approaches to overcome these limitations, promising to extend MD capabilities to biologically relevant timescales and system sizes while maintaining atomic-level accuracy. As these computational methods continue to evolve, they will further enhance our ability to understand and engineer molecular systems for applications in drug discovery, materials science, and fundamental biological research.

Implementing the Dynamics: Integration Algorithms and Real-World Applications in Biomedicine

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the fundamental task is to solve Newton's equations of motion for a system of N interacting particles to trace their trajectories over time. For a conservative physical system, Newton's equation is given by ( m\ddot{\mathbf{x}}(t) = -\nabla V(\mathbf{x}(t)) ), where ( m ) is mass, ( \mathbf{x} ) is position, and ( V ) is the potential energy [15]. Since analytical solutions are infeasible for many-body systems, numerical integration methods are indispensable. Among these, the Störmer-Verlet group of algorithms—including the Verlet, Velocity Verlet, and Leap-Frog methods—has become the cornerstone of modern MD simulations due to its numerical stability, time-reversibility, and excellent energy conservation properties [15] [19]. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of these core integrators, framed within the context of their application in molecular dynamics research for computational chemists, physicists, and drug development professionals.

Mathematical Foundation

The evolution of a molecular system is governed by Newton's second law, where the acceleration ( \mathbf{a}(t) ) of each atom is computed from the force ( \mathbf{F} ) acting upon it, which is the negative gradient of the potential energy ( V ) [4]:

[ \mathbf{a}(t) = \frac{\mathbf{F}(t)}{m} = -\frac{1}{m} \nabla V(\mathbf{x}(t)) ]

The objective of MD is to numerically integrate this second-order differential equation by discretizing time into small steps ( \Delta t ), typically on the order of femtoseconds (( 10^{-15} ) s) to properly resolve atomic vibrations [4]. Most finite-difference integration algorithms approximate future positions using Taylor expansions:

[ \mathbf{x}(t + \Delta t) = \mathbf{x}(t) + \mathbf{v}(t)\Delta t + \frac{1}{2}\mathbf{a}(t)\Delta t^2 + \frac{1}{6}\mathbf{b}(t)\Delta t^3 + \mathcal{O}(\Delta t^4) ] [ \mathbf{v}(t + \Delta t) = \mathbf{v}(t) + \mathbf{a}(t)\Delta t + \frac{1}{2}\mathbf{b}(t)\Delta t^2 + \mathcal{O}(\Delta t^3) ]

where ( \mathbf{b}(t) ) represents the third derivative of position with respect to time [15] [4]. The various Verlet-type algorithms emerge from different manipulations of these expansions, particularly regarding how velocity is incorporated and approximated.

Core Integration Algorithms

The Verlet Algorithm

The original Verlet algorithm [15] uses the positions at time ( t ) and ( t - \Delta t ), along with the current acceleration, to compute the new position at ( t + \Delta t ):

[ \mathbf{x}(t + \Delta t) = 2\mathbf{x}(t) - \mathbf{x}(t - \Delta t) + \mathbf{a}(t)\Delta t^2 ]

This formulation is derived by adding the forward and backward Taylor expansions around ( \mathbf{x}(t) ), which cancels out the odd-order terms, including the explicit velocity term [15] [20]. The velocity can be approximated retrospectively as:

[ \mathbf{v}(t) = \frac{\mathbf{x}(t + \Delta t) - \mathbf{x}(t - \Delta t)}{2\Delta t} ]

Table 1: Characteristics of the Basic Verlet Algorithm

| Property | Description |

|---|---|

| Global Error | ( \mathcal{O}(\Delta t^2) ) for positions [20] |

| Velocity Accuracy | ( \mathcal{O}(\Delta t^2) ), but subject to roundoff errors [20] |

| Time-Reversibility | Yes [21] |

| Self-Starting | No, requires position at ( t - \Delta t ) [4] |

| Computational Storage | Positions and accelerations only (velocities not stored) |

The Verlet algorithm's main advantage is its numerical stability and time-reversibility, which contributes to excellent long-term energy conservation in molecular systems [15]. However, its disadvantages include not being self-starting and potential numerical precision issues from calculating velocity as a small difference between two large numbers (position vectors) [20] [4].

The Velocity Verlet Algorithm

The Velocity Verlet algorithm addresses the limitations of the basic Verlet method by explicitly incorporating and tracking velocities [4]. This is achieved through the following update sequence:

[ \mathbf{x}(t + \Delta t) = \mathbf{x}(t) + \mathbf{v}(t)\Delta t + \frac{1}{2}\mathbf{a}(t)\Delta t^2 ] [ \mathbf{a}(t + \Delta t) = -\frac{1}{m} \nabla V(\mathbf{x}(t + \Delta t)) ] [ \mathbf{v}(t + \Delta t) = \mathbf{v}(t) + \frac{1}{2}[\mathbf{a}(t) + \mathbf{a}(t + \Delta t)]\Delta t ]

Table 2: Characteristics of the Velocity Verlet Algorithm

| Property | Description |

|---|---|

| Global Error | ( \mathcal{O}(\Delta t^2) ) for both positions and velocities [4] |

| Time-Reversibility | Yes [22] |

| Self-Starting | Yes [20] |

| Velocity Handling | Explicit, direct access without approximation [22] |

| Computational Cost | Two force calculations per time step (implied) |

| Numerical Stability | High, excellent energy conservation [22] |

This algorithm is particularly valued in molecular dynamics for its numerical stability and direct access to velocities, which are essential for calculating kinetic energy and temperature [4] [22]. The mathematical equivalence between the Velocity Verlet and the original Verlet algorithm can be demonstrated through algebraic manipulation of the update equations [20].

The Leap-Frog Algorithm

The Leap-Frog method improves velocity handling by staging positions and velocities at slightly offset times [23]. Specifically, it calculates velocities at half-integer time steps:

[ \mathbf{v}\left(t + \frac{\Delta t}{2}\right) = \mathbf{v}\left(t - \frac{\Delta t}{2}\right) + \mathbf{a}(t)\Delta t ] [ \mathbf{x}(t + \Delta t) = \mathbf{x}(t) + \mathbf{v}\left(t + \frac{\Delta t}{2}\right)\Delta t ]

The current velocity, when needed for energy calculations, can be approximated as:

[ \mathbf{v}(t) \approx \frac{1}{2}\left[\mathbf{v}\left(t - \frac{\Delta t}{2}\right) + \mathbf{v}\left(t + \frac{\Delta t}{2}\right)\right] ]

Table 3: Characteristics of the Leap-Frog Algorithm

| Property | Description |

|---|---|

| Global Error | ( \mathcal{O}(\Delta t^2) ) [24] |

| Time-Reversibility | Yes [23] |

| Self-Starting | Yes, but requires initial half-step velocity [23] |

| Velocity Handling | At half-time steps, requires interpolation for full-step values [4] |

| Numerical Stability | Very high, often superior for oscillatory motion [23] [22] |

| Energy Conservation | Excellent, symplectic [23] |

An alternative "kick-drift-kick" formulation of the Leap-Frog method is also commonly used [23]:

[ \mathbf{v}\left(t + \frac{\Delta t}{2}\right) = \mathbf{v}(t) + \frac{1}{2}\mathbf{a}(t)\Delta t ] [ \mathbf{x}(t + \Delta t) = \mathbf{x}(t) + \mathbf{v}\left(t + \frac{\Delta t}{2}\right)\Delta t ] [ \mathbf{v}(t + \Delta t) = \mathbf{v}\left(t + \frac{\Delta t}{2}\right) + \frac{1}{2}\mathbf{a}(t + \Delta t)\Delta t ]

The Leap-Frog algorithm is particularly effective for gravitational N-body simulations and molecular dynamics where energy conservation is critical [23].

Comparative Analysis

Algorithmic Properties

Table 4: Comprehensive Comparison of Verlet-Type Integrators

| Feature | Verlet | Velocity Verlet | Leap-Frog |

|---|---|---|---|

| Position Update | ( 2\mathbf{x}(t) - \mathbf{x}(t-\Delta t) + \mathbf{a}(t)\Delta t^2 ) | ( \mathbf{x}(t) + \mathbf{v}(t)\Delta t + \frac{1}{2}\mathbf{a}(t)\Delta t^2 ) | ( \mathbf{x}(t) + \mathbf{v}(t+\frac{\Delta t}{2})\Delta t ) |

| Velocity Update | Approximated retrospectively: ( \frac{\mathbf{x}(t+\Delta t) - \mathbf{x}(t-\Delta t)}{2\Delta t} ) | ( \mathbf{v}(t) + \frac{1}{2}[\mathbf{a}(t) + \mathbf{a}(t+\Delta t)]\Delta t ) | ( \mathbf{v}(t+\frac{\Delta t}{2}) = \mathbf{v}(t-\frac{\Delta t}{2}) + \mathbf{a}(t)\Delta t ) |

| Explicit Velocities | No | Yes | Half-step only |

| Self-Starting | No | Yes | Requires initial half-step velocity |

| Computational Cost | Low | Medium | Low |

| Numerical Stability | High | High | Very High |

| Best Applications | Basic MD, constrained systems | General MD, velocity-dependent forces | N-body simulations, oscillatory systems [22] |

Accuracy and Error Analysis

All three algorithms exhibit second-order global error ( \mathcal{O}(\Delta t^2) ) for positions, meaning that halving the time step reduces the error by approximately a factor of four [15] [24]. The local truncation error (per-step error) is ( \mathcal{O}(\Delta t^3) ) for a single update of positions and velocities [24].

For the basic Verlet algorithm, the velocity error is also ( \mathcal{O}(\Delta t^2) ), but the calculation suffers from numerical precision issues due to the subtraction of two similar-sized position vectors [20]. In contrast, Velocity Verlet provides second-order accuracy for both positions and velocities without this numerical instability [4]. The Leap-Frog method similarly achieves second-order accuracy with excellent long-term stability [23].

The time symmetry inherent in these methods eliminates the leading-order error term, resulting in improved energy conservation compared to non-symmetric methods like Euler integration [15]. This property makes them particularly suitable for long-time molecular dynamics simulations where energy drift would otherwise corrupt the results.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the sequential computational workflow for the Velocity Verlet integrator, highlighting the force calculation as the most computationally intensive step:

Advanced Implementations

Higher-Order Integration Schemes

For applications requiring higher accuracy, the standard Leap-Frog algorithm can be extended using Yoshida's method to create higher-order integrators [23]. The 4th-order Yoshida integrator applies the Leap-Frog method with multiple intermediary steps and specific coefficients:

[ \begin{aligned} xi^1 &= xi + c1 vi \Delta t, & vi^1 &= vi + d1 a(xi^1) \Delta t, \ xi^2 &= xi^1 + c2 vi^1 \Delta t, & vi^2 &= vi^1 + d2 a(xi^2) \Delta t, \ xi^3 &= xi^2 + c3 vi^2 \Delta t, & vi^3 &= vi^2 + d3 a(xi^3) \Delta t, \ x{i+1} &= xi^3 + c4 vi^3 \Delta t, & v{i+1} &= vi^3 \end{aligned} ]

The coefficients are defined as [23]:

[ \begin{aligned} w0 &= -\frac{\sqrt[3]{2}}{2 - \sqrt[3]{2}}, & w1 &= \frac{1}{2 - \sqrt[3]{2}}, \ c1 = c4 &= \frac{w1}{2}, & c2 = c3 &= \frac{w0 + w1}{2}, \ d1 = d3 &= w1, & d2 &= w0 \end{aligned} ]

Numerically, these coefficients are approximately ( c1 = c4 = 0.6756 ), ( c2 = c3 = -0.1756 ), ( d1 = d3 = 1.3512 ), and ( d_2 = -1.7024 ) [23]. This approach achieves fourth-order accuracy while maintaining the symplectic property, though it requires three force evaluations per time step instead of one.

The Researcher's Toolkit for Molecular Dynamics

Table 5: Essential Components for Molecular Dynamics Simulations

| Component | Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Potential Energy Function | Defines interatomic interactions; force derivation: ( F_i = -\nabla V ) | Typically the most computationally expensive part [4] |

| Initial Conditions | Starting positions and velocities for all atoms | Velocities often initialized from Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution |

| Time Step (Δt) | Discrete interval for numerical integration | Typically 0.5-2 fs; must be small enough to resolve fastest vibrations [4] |

| Thermostat/Berendsen | Regulates temperature | Often coupled with integration steps |

| Periodic Boundary Conditions | Mimics bulk system | Applied during force calculations |

| Neighbor Lists | Accelerates force calculations | Critical for efficiency in large systems |

Application in Modern Molecular Dynamics

In contemporary molecular dynamics research, these integration algorithms form the computational engine for studying diverse biological and materials systems. Recent advances include their application in simulating complex systems such as oil-displacement polymers for enhanced oil recovery, where MD simulations help optimize polymer properties and understand polymer-oil interactions at the atomic scale [7].

The selection of appropriate integration algorithms remains an active area of research, with recent investigations into automated algorithm selection for short-range molecular dynamics simulations demonstrating that adaptive choice of integrators can achieve speedups of up to 4.05 compared to naive approaches [25]. This is particularly relevant for drug development professionals who require both accuracy and computational efficiency when simulating protein-ligand interactions over biologically relevant timescales.

Recent studies have also challenged conventional wisdom regarding optimal time steps in molecular dynamics, suggesting that standard step size values used currently may be lower than necessary for accurate sampling, potentially enabling more efficient simulations without sacrificing physical accuracy [19].

The Verlet, Velocity Verlet, and Leap-Frog algorithms represent a family of numerically stable, second-order accurate integration methods that have become the standard for molecular dynamics simulations. Their key advantages—including time-reversibility, symplectic properties, and excellent energy conservation—make them uniquely suited for simulating Newton's equations of motion in complex molecular systems. While mathematically equivalent in their core physics, each variant offers distinct practical advantages: the Velocity Verlet algorithm provides explicit, synchronous velocity integration; the Leap-Frog method offers computational efficiency and stability; and the original Verlet algorithm maintains simplicity where velocities are not required. For researchers in computational drug development and materials science, understanding the nuances of these integrators is essential for designing accurate and efficient molecular dynamics simulations that can reliably predict system behavior over relevant timescales.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation serves as a powerful "computational microscope," enabling researchers to observe and quantify the time-dependent behavior of biomolecular systems at atomic resolution. This technical guide details the complete MD simulation workflow, from initial system construction through trajectory analysis, framing each step within the core context of numerically integrating Newton's equations of motion. The methodology presented provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a standardized protocol for conducting rigorous simulations of proteins, protein-ligand complexes, and other biomolecular systems, facilitating investigations into structural stability, binding interactions, and dynamic molecular processes.

At its core, molecular dynamics simulation applies Newton's equations of motion to molecular systems, iteratively calculating atomic positions and velocities over time [26]. The fundamental principle involves numerically integrating Newton's second law, F = ma, where the force F is derived from the negative gradient of the potential energy function of the system [26]. This deterministic approach generates trajectories describing system evolution, allowing computation of structural, dynamic, and thermodynamic properties through statistical mechanics [26].

MD simulations employ classical mechanics formulations, predominantly using the Hamiltonian framework, where the system is described by the positions and momenta of all particles [26]. For computational tractability, most biomolecular simulations utilize molecular mechanics force fields rather than quantum mechanical descriptions, representing molecules as atoms with assigned charges, connected by springs with empirically parameterized potential energy functions describing bonded and non-bonded interactions [26]. This classical approximation enables simulation of systems comprising tens to hundreds of thousands of atoms over biologically relevant timescales from nanoseconds to microseconds [26].

The Molecular Dynamics Simulation Workflow

The complete MD simulation process follows a systematic workflow to ensure proper system preparation and physical relevance of results. The diagram below illustrates the key stages:

Initial Structure Preparation

The simulation begins with obtaining or generating an appropriate initial atomic structure, typically from experimental sources like X-ray crystallography or NMR spectroscopy [27]. The Protein Data Bank (PDB) format provides a standard representation for macromolecular structure data [27]. This structure must be "cleaned" by removing non-protein atoms such as solvent molecules and crystallographic additives, as these will be systematically reintroduced later [27]. For protein-ligand complexes, the ligand must be properly parameterized separately and integrated into the system topology [28].

System Setup and Topology Generation

The initial structure processing involves several automated steps to create the necessary simulation files:

Topology Generation: The topology file contains all information required to describe the molecule for simulation purposes, including atom masses, bond lengths and angles, and partial charges [27]. This is constructed using a selected force field (e.g., OPLS/AA, CHARMM36) that provides parameterized building blocks for molecular components [29] [27].

Structure Conversion: The PDB structure is converted to a GRO file format, with the structure centered in a simulation box (unit cell) [27].

Position Restraint File: A position restraint file is created for use during equilibration phases, allowing controlled relaxation of the system [27].

Solvation and Ion Addition

The biomolecule is placed in a solvent environment, typically a water box with margins ensuring sufficient separation from periodic images [28] [27]. Common water models include SPC, SPC/E, and TIP3P [27]. The system is then neutralized by adding counterions (e.g., Na+ or Cl-), and additional ions may be included to achieve physiological concentrations (typically 0.15 M) [28] [27]. The simulation box type can be cubic, rectangular, or rhombic dodecahedron, with the latter being most efficient due to reduced solvent requirements [27].

Energy Minimization

Energy minimization removes steric clashes and unusual geometry that would artificially raise the system energy [27]. This step employs algorithms like steepest descent or conjugate gradient to find a local energy minimum by adjusting atomic coordinates [30]. The process is crucial for relaxing strained bonds, angles, and van der Waals contacts introduced during system construction before beginning dynamics.

Table 1: Common Energy Minimization Parameters

| Parameter | Typical Value | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Integrator | Steepest descent | Robustly handles poor initial geometries |

| Maximum force tolerance (emtol) | 1000 kJ/mol/nm | Convergence criterion |

| Maximum steps | 50,000 | Prevents infinite loops |

| Coulomb cutoff | 1.0 nm | Short-range electrostatics treatment |

| van der Waals cutoff | 1.0 nm | Short-range van der Waals treatment |

System Equilibration

Equilibration brings the system to the desired temperature and pressure while stabilizing these conditions. This is typically performed in two sequential phases:

NVT Equilibration (Constant Number, Volume, and Temperature)

The first equilibration phase maintains constant particle number, volume, and temperature using the NVT ensemble (canonical ensemble) [31] [27]. During this phase, the protein is typically held in place using position restraints while the solvent is allowed to move freely [27]. The system is coupled to a thermostat (e.g., Berendsen, v-rescale) to maintain the target temperature [31]. The duration typically ranges from 50-100 ps, with the temperature progression monitored to ensure stabilization at the desired value [31].

NPT Equilibration (Constant Number, Pressure, and Temperature)

The second equilibration phase uses the NPT ensemble (isothermal-isobaric ensemble) to maintain constant particle number, pressure, and temperature [32]. This phase allows the system density to adjust to the target pressure (typically 1 bar) using a barostat (e.g., C-rescale) [32]. Position restraints on the protein are typically maintained but may be gradually relaxed. This phase generally requires longer duration than NVT as pressure relaxation occurs more slowly than temperature stabilization [32].

Table 2: Equilibration Parameters and Typical Values

| Parameter | NVT Equilibration | NPT Equilibration |

|---|---|---|

| Ensemble | Constant particles, volume, temperature | Constant particles, pressure, temperature |

| Duration | 50-100 ps | 100-500 ps |

| Temperature coupling | Thermostat (e.g., v-rescale) | Thermostat (e.g., v-rescale) |

| Pressure coupling | None | Barostat (e.g., C-rescale) |

| Position restraints | Applied to protein heavy atoms | Often applied but potentially weaker |

| Target temperature | Desired simulation temperature | Same as NVT |

| Target pressure | N/A | 1 bar |

Production Simulation

The production phase follows successful equilibration, with all restraints typically removed to allow natural system dynamics [33]. This phase generates the trajectory used for analysis, with duration dependent on the biological processes of interest—typically ranging from nanoseconds to microseconds [26]. Configuration snapshots are saved at regular intervals (e.g., every 10-100 ps) to create the trajectory file [33]. Multiple independent replicates may be run to improve sampling and statistical significance [28].

Trajectory Analysis

The final trajectory is analyzed to extract biologically relevant information. Common analyses include [28] [33]:

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Measures structural stability by quantifying deviation from a reference structure.

- Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF): Identifies regions of flexibility within the protein.

- Radius of Gyration: Assesses protein compactness and folding stability.

- Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA): Quantifies solvent exposure.

- Hydrogen Bond Analysis: Identifies persistent molecular interactions.

- Principal Component Analysis: Identifies collective motions in the system.

Table 3: Essential Tools and Resources for MD Simulations

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Simulation Software | GROMACS, NAMD, AMS | MD engines for running simulations [34] [27] |

| Force Fields | CHARMM36, OPLS/AA, AMBER | Parameter sets defining molecular interactions [29] [28] [27] |

| Water Models | SPC/E, TIP3P, TIP4P | Solvent representation with different properties [27] |

| Analysis Tools | GROMACS analysis suite, VMD, MDAnalysis | Trajectory processing and property calculation [28] [33] |

| Visualization Software | PyMol, VMD, Chimera | 3D structure and trajectory visualization |

| System Preparation | pdb2gmx, CHARMM-GUI | Initial structure processing and topology building [28] [27] |

Methodology: Detailed Experimental Protocol

System Setup Protocol

- Structure Preparation: Download a PDB file and remove non-protein atoms using text processing tools (e.g.,

grep -v HETATM) [27]. - Topology Generation: Use

pdb2gmxor equivalent tool with selected force field and water model: - Define Simulation Box: Use

editconfto define unit cell with appropriate margins (≥1.0 nm recommended): - Solvation: Add water using

solvate: - Ion Addition: Neutralize and achieve desired ion concentration using

genion:

Energy Minimization Protocol

- Parameter Preparation: Create minim.mdp parameter file with steepest descent integrator and appropriate cutoffs [27].

- Run Minimization: Execute energy minimization:

- Convergence Check: Verify the maximum force is below the tolerance threshold (typically 1000 kJ/mol/nm).

Equilibration Protocol

The following diagram illustrates the equilibration workflow with key parameters:

NVT Equilibration:

- Prepare nvt.mdp file with position restraints and temperature coupling

- Generate NVT run input:

- Monitor temperature stability through log files and energy output

NPT Equilibration:

- Prepare npt.mdp with added pressure coupling

- Generate NPT run input using final NVT coordinates and checkpoint:

- Verify pressure and density stabilization around reference values

Production Simulation Protocol

- Parameter Preparation: Create md.mdp with all restraints removed and desired production duration.

- Execute Production Run:

- Trajectory Saving: Save frames at regular intervals (e.g., every 10 ps) for analysis.

Analysis Protocol

- RMSD Calculation:

- RMSF Calculation:

- Radius of Gyration:

The molecular dynamics simulation workflow provides a systematic approach to studying biomolecular systems through numerical integration of Newton's equations of motion. Each stage—from initial system preparation through trajectory analysis—plays a critical role in ensuring physically meaningful results. As computational resources advance and force fields improve, MD simulations continue to grow as indispensable tools in structural biology and drug discovery, offering unprecedented atomic-level insights into molecular mechanisms and interactions that complement experimental approaches.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation has emerged as an indispensable tool in biomedical research, providing atomic-level insight into the function of proteins, the mechanism of drug binding, and the complex dynamics of biological membranes. At its core, MD is a simulation method based on the principles of classical mechanics, specifically Newton's second law of motion, which describes how the physical forces between atoms result in molecular motion [35]. In MD, this fundamental relationship is expressed as a gradient of potential energy: ( \vec{F}i = -\nablai V({\vec{r}j}) ), where ( F ) represents the conservative forces between atoms, ( V ) is the potential energy, and ( \vec{r}j ) denotes atomic positions [35]. This equation can be rewritten using ( F = ma ) to express acceleration as the second time derivative of position: ( m\partialt^2 \vec{r}i = -\nablai V({\vec{r}j}) ) [35]. The numerical integration of these equations of motion across femtosecond time steps enables the simulation of biomolecular systems over biologically relevant timescales, revealing processes inaccessible to experimental observation.

The power of MD lies in its ability to bridge static structural information with dynamic functional data. While experimental techniques like X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy provide crucial structural snapshots, MD simulations reveal the continuous trajectories and transition pathways that define biological function. This capability is particularly valuable for understanding allosteric regulation, conformational changes in membrane proteins, and the residence times of drug molecules bound to their targets [18] [36]. As MD methodologies have advanced, they have become increasingly integrated with machine learning approaches and enhanced sampling techniques, enabling the investigation of longer timescales and more complex biological systems than ever before [18] [37].

Computational Frameworks and Methodological Advances

Essential Components of MD Simulations

The reliability of MD simulations depends critically on several computational components that together determine the accuracy and biological relevance of the results. Force fields—empirical mathematical functions that describe the potential energy of a system of particles—are particularly important, as they define the physical interactions between atoms [18] [38]. Widely used force fields include AMBER, CHARMM, and GROMOS, which have been rigorously tested across diverse biological applications [18]. The selection of an appropriate force field significantly influences simulation outcomes and must be matched to the specific biological system under investigation [18].

Specialized MD software packages leverage these force fields to simulate biomolecular systems. Key packages include GROMACS, DESMOND, and AMBER, which provide optimized algorithms for efficient computation [18]. These packages implement numerical integrators such as the Verlet algorithm to solve Newton's equations of motion, enabling the precise calculation of atomic trajectories [35]. Additionally, periodic boundary conditions are commonly employed to simulate a small unit of the system while effectively representing a larger biological environment, and Ewald summation techniques handle the long-range electrostatic interactions that are crucial for modeling biological systems accurately [38].

Emerging Methodological Innovations

Recent advances in MD methodologies have dramatically expanded the scope of biological problems that can be addressed computationally. Enhanced sampling techniques such as metadynamics, Markov State Models, and Gaussian accelerated MD have enabled researchers to overcome the traditional timescale limitations of MD, allowing the simulation of rare events like protein folding and drug unbinding [39] [36]. These methods apply bias potentials or adaptive sampling strategies to efficiently explore conformational space and quantify thermodynamic and kinetic properties.