LUCA Genome Reconstruction: Decoding the Complex Blueprint of Life's Common Ancestor

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the methodologies, challenges, and recent breakthroughs in reconstructing the genome of the Last Universal Common Ancestor (LUCA).

LUCA Genome Reconstruction: Decoding the Complex Blueprint of Life's Common Ancestor

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the methodologies, challenges, and recent breakthroughs in reconstructing the genome of the Last Universal Common Ancestor (LUCA). Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational biology of LUCA, details advanced phylogenetic and computational techniques for genomic inference, addresses key controversies and limitations in the field, and validates findings through comparative genomics. Synthesizing evidence from recent high-impact studies, we present LUCA as a complex prokaryote-grade organism with a genome of ~2.5 Mb, offering implications for understanding early evolutionary processes and informing modern biomedical research.

LUCA Revealed: Establishing the Biology of Life's Common Ancestor

The Last Universal Common Ancestor (LUCA) represents the primordial organism or population from which all extant cellular life descends. Research into its nature has evolved from Darwin's theoretical "primordial form" to sophisticated, data-driven genomic reconstructions. Modern studies infer that LUCA was a complex, prokaryote-grade organism with a genome encoding approximately 2,600 proteins, existed around 4.2 billion years ago, and inhabited an anaerobic, hydrothermal vent environment [1] [2] [3]. This whitepaper details the methodologies driving these inferences, presents quantitative reconstructions of LUCA's genomic and metabolic capabilities, and discusses the implications for understanding early evolution and the origin of life.

The hypothesis of a universal common ancestor is a foundational corollary of evolutionary theory. Charles Darwin first articulated this concept in On the Origin of Species (1859), inferring from analogy "that probably all the organic beings which have ever lived on this earth have descended from some one primordial form" [1]. The modern term "LUCA" emerged in the 1990s, reframing this concept not as the first life form, but as the last common ancestor of Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukarya whose characteristics can be inferred from modern descendants [1].

A critical shift in understanding has been the move from a three-domain tree of life (Bacteria, Archaea, Eukarya) to a two-domain tree, where Eukarya are an evolutionary offshoot resulting from an endosymbiotic merger between an archaeal host and a bacterial symbiont [3]. In this model, LUCA sits at the basal split between the Archaea and Bacteria, making its accurate reconstruction pivotal to understanding life's earliest divergence [3].

Modern Genomic Inference Methodologies

Inferring LUCA's characteristics relies on comparative genomics and phylogenetic analyses applied to extant organisms. The core challenge is distinguishing genes inherited from LUCA via vertical descent from those acquired through horizontal gene transfer (HGT), which can obscure deep evolutionary signals [3] [4].

Phylogenetic Profiling and Reconciliation

Early approaches identified LUCA's genes by seeking universal genes present across all domains of life. This method yielded a very small set of core genes (e.g., ~30), insufficient to sustain a living organism [3]. A more productive strategy identifies genes present in at least two major groups of bacteria and two major groups of archaea, suggesting vertical inheritance from a common ancestor rather than HGT [1] [3].

Advanced probabilistic reconciliation algorithms, such as the Amalgamated Likelihood Estimation (ALE), now model the evolution of gene families by comparing distributions of bootstrapped gene trees against a known species tree. This method explicitly accounts for gene duplications, transfers, and losses, allowing researchers to estimate the probability that any given gene family was present in LUCA [2].

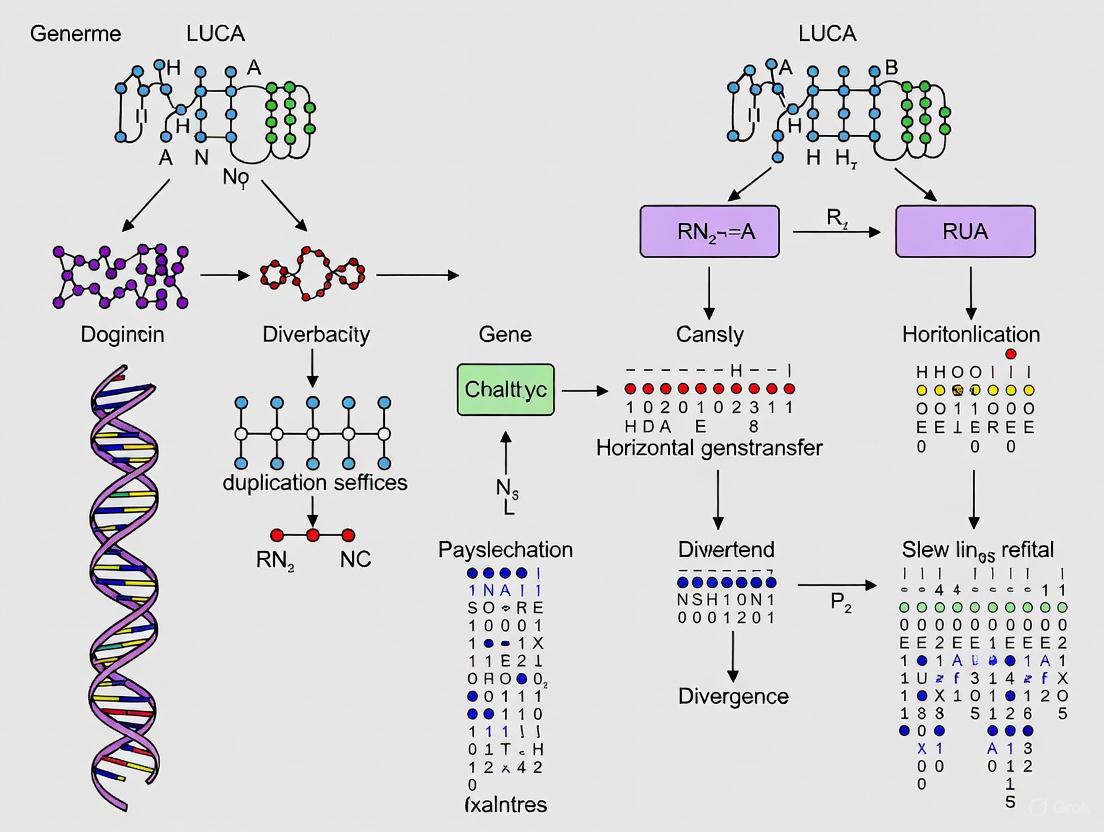

Figure 1: Workflow for Genomic Inference of LUCA. ALE reconciles gene and species trees to model Duplication (D), Transfer (T), and Loss (L) events [2].

Molecular Clock Dating

Dating LUCA's existence uses molecular clock analyses calibrated with the fossil and geochemical record. A robust approach involves analyzing pre-LUCA paralogues—genes that duplicated before LUCA and whose copies were both present in its genome [2]. The root of these gene trees represents the pre-LUCA duplication event, while LUCA is represented by two descendant nodes. This "cross-bracing" with fossil calibrations reduces uncertainty in estimating divergence times [2]. Recent analyses using this method place LUCA at ~4.2 Ga (4.09–4.33 Ga), soon after the end of the late heavy bombardment [2].

Consensus Approaches

Given methodological variations across studies, consensus predictions provide a more accurate portrayal of LUCA's core proteome. One analysis of eight independent LUCA reconstruction studies found that while individual studies showed low pairwise similarity, their consensus revealed a LUCA with a sophisticated functional repertoire related to protein synthesis, amino acid and nucleotide metabolism, and organic cofactor use [4].

Reconstructed Attributes of LUCA

Synthesizing evidence from multiple genomic studies allows a detailed, though incomplete, picture of LUCA to be drawn.

Genomic and Cellular Complexity

| Genomic Attribute | Inferred Characteristic | Key Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Genome Size | ~2.5 Mb (2.49-2.99 Mb) [2] | Phylogenetic reconciliation & predictive modeling |

| Protein-Coding Genes | ~2,600 proteins [2] | Analysis of 355 high-probability gene families [2] |

| Genetic Code | DNA-based, with universal genetic code [1] [4] | Universality of code & DNA replication proteins |

| Cellular Structure | Lipid bilayer membrane, water-based cytoplasm [1] | Universal cellular features & membrane protein homology |

| Information Processing | DNA replication, transcription, and translation machinery [1] [4] | Universal conservation of core machinery (e.g., ribosomes, RNA polymerase) |

Table 1: Inferred Genomic and Cellular Characteristics of LUCA.

LUCA was not a simple, primitive entity but a prokaryote-grade organism with genomic complexity comparable to many modern bacteria and archaea [2]. Its cellular machinery included DNA replication and repair enzymes, a full transcription and translation system (including ribosomes, tRNAs, and aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases), and a lipid bilayer membrane [1] [4].

Metabolic Network and Physiology

LUCA's reconstructed metabolism depicts an organism adapted to a primordial, anaerobic world.

| Metabolic Pathway/Function | Inferred Capability | Environmental Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Wood-Ljungdahl Pathway | Present (Acetogenesis) [1] [2] | H2-dependent, CO2-fixing metabolism |

| Nitrogen Fixation | Present [1] | Use of atmospheric N2 |

| Energy Production | Chemiosmosis & ATP synthesis [1] | Proton gradients across membrane |

| Carbon Metabolism | Reverse Krebs cycle, Gluconeogenesis [1] | Anaerobic, autotrophic carbon fixation |

| Ion Dependence | FeS clusters, transition metals [1] | Dependence on geochemically available metals |

Table 2: Key Inferred Metabolic Capabilities of LUCA.

Metabolic reconstructions consistently show LUCA as an anaerobic, thermophilic acetogen that used molecular hydrogen (H2) as an energy source and carbon dioxide (CO2) as a carbon source, via the Wood-Ljungdahl (reductive acetyl-CoA) pathway [1] [2] [3]. Its biochemistry was replete with iron-sulfur (FeS) clusters and radical reaction mechanisms, consistent with an origin in an iron-rich environment [1].

Ecological Context and Viral Interactions

LUCA was not an isolated entity but part of an established ecological community. Its metabolic products would have created niches for other contemporary microbes, potentially forming a recycling ecosystem where other organisms consumed its waste products, such as methane [2] [5]. Furthermore, the inferred presence of a CRISPR-Cas-like immune system suggests LUCA faced pressure from viral predators, indicating a complex early biosphere where viral-mediated horizontal gene transfer may have been common [2] [5].

Figure 2: LUCA's Proposed Ecological Niche. LUCA's metabolism supported a simple ecosystem with potential nutrient recycling [2] [5].

Key Experimental Protocols in LUCA Research

Protocol: Phylogenetic Reconciliation for Gene Content Inference

This protocol details the use of ALE to infer gene content of LUCA [2].

- Input Data Preparation: Curate a set of ~700 high-quality genomes (350 Archaea, 350 Bacteria) and a reference species tree based on a concatenated set of 57 universal marker genes.

- Gene Family Definition: Cluster all protein sequences into gene families using databases like KEGG Orthology (KO) or Clusters of Orthologous Genes (COG).

- Gene Tree Estimation: For each gene family, infer a distribution of likely gene trees using bootstrapping and maximum likelihood methods.

- Reconciliation Analysis: Use the ALE algorithm to reconcile the distribution of gene trees with the reference species tree, modeling events of gene duplication, transfer, and loss.

- Probability Assignment: Calculate the posterior probability of each gene family being present at the LUCA node based on the reconciliation model.

- Genome Size Estimation: Use a predictive model trained on modern prokaryotes to estimate LUCA's total genome size and protein count from the number of inferred gene families.

Protocol: Molecular Clock Dating with Pre-LUCA Paralogues

This protocol estimates the age of LUCA using universal paralogous genes [2].

- Gene Selection: Identify universal gene families that resulted from a duplication event predating LUCA (e.g., catalytic and non-catalytic subunits of ATP synthases, aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases).

- Sequence Alignment: Compile and align protein sequences for each paralogue from a broad taxonomic sample.

- Gene Tree Construction: Build phylogenetic trees for each paralogous family.

- Fossil Calibration: Define minimum and maximum age constraints using the fossil and geochemical record. A key minimum bound is the evidence for oxygenic photosynthesis at ~2.95 Ga. The maximum bound is set by the Moon-forming impact at ~4.51 Ga.

- Divergence Time Analysis: Perform Bayesian relaxed molecular clock dating analysis (e.g., using models like GBM or ILN) on both individual and concatenated gene alignments, incorporating the fossil calibrations.

- Age Inference: The estimated age of the duplicated LUCA nodes across analyses provides a composite age estimate for LUCA itself.

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The following table lists key computational and data resources essential for LUCA genome reconstruction research.

| Resource/Solution | Function in LUCA Research |

|---|---|

| KEGG Orthology (KO) Database | Provides curated functional annotations for genes, enabling mapping of inferred gene families to metabolic pathways and cellular functions [2]. |

| Clusters of Orthologous Genes (COG) | Offers a coarse-grained system for clustering orthologous gene groups, useful for identifying universally conserved genes [2] [4]. |

| eggNOG Database | A database of orthologous groups and functional annotation, used for mapping and comparing predictions from multiple LUCA studies [4]. |

| ALE (Amalgamated Likelihood Estimation) | A probabilistic software tool for reconciling gene and species trees, which explicitly models horizontal gene transfer, a critical factor in deep evolutionary time [2]. |

| Bayesian Molecular Clock Software (e.g., MCMCTree, BEAST2) | Software packages used to integrate sequence data with fossil calibrations to estimate divergence times in deep evolutionary history [2]. |

Table 3: Key Research Resources for Genomic Inference of LUCA.

Genomic inference has transformed LUCA from a theoretical abstraction into a tangibly complex organism with a defined physiology and habitat. The consensus view emerging from modern data places LUCA as a sophisticated, cellular, anaerobic acetogen living in a hydrothermal setting over 4 billion years ago [1] [2] [3]. Its early existence suggests life arose and achieved complexity relatively quickly after Earth's formation, with profound implications for the potential abundance of life in the universe [5].

Future research will be bolstered by the ever-expanding database of genomic diversity, particularly from under-sampled branches of the archaeal and bacterial domains. Improved phylogenetic models that better account for the complexities of deep evolution, such as varying evolutionary rates and pervasive HGT, will further refine our picture of LUCA. Integrating these genomic insights with geochemical models of the early Earth and experimental work on primordial metabolisms will continue to close the gap between life's origin and its last universal common ancestor.

The Last Universal Common Ancestor (LUCA) represents the primordial organism or population of organisms from which all extant cellular life—Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukarya—descends. It is a fundamental concept in evolutionary biology, situating it as the root of the tree of life. Research into LUCA's nature, specifically when it lived and its biological characteristics, provides critical insights into life's early evolution on Earth and the environmental conditions of the primordial Earth. A pivotal 2024 study published in Nature Ecology & Evolution has generated a refined estimate, using sophisticated molecular clock analyses, that places LUCA at approximately 4.2 billion years ago (Ga) [2] [6]. This timeline suggests that life established itself and achieved a significant level of complexity remarkably quickly after the Earth's formation. This whitepaper delves into the molecular clock methodologies, genomic inferences, and physiological reconstructions that underpin this timeline, framing it within the broader context of LUCA genome reconstruction research.

Molecular Clock Dating of LUCA

Establishing a timescale for life's early evolution is challenging due to the sparse and contested nature of the Archaean fossil record. Molecular clock analyses, which translate genetic sequence divergence into geological time, have become the primary tool for estimating the age of ancient evolutionary events like the divergence of Bacteria and Archaea from LUCA.

Key Methodological Innovations

Recent analyses have overcome several historical limitations by employing specific methodological advances.

Pre-LUCA Paralogue Analysis: Instead of dating LUCA directly from the root of a species tree, which is highly uncertain, the 2024 study analyzed genes that had duplicated prior to LUCA's existence [2] [7]. This means LUCA possessed two copies of these genes, and the root in these gene trees represents this older duplication event. Using universal paralogues, such as subunits of ATP synthase and specific aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases, allows for "cross-bracing" [2]. The same species divergence events are represented on both sides of the gene tree, and the same fossil calibrations can be applied at least twice, significantly reducing uncertainty in converting genetic distance into absolute time [2].

Fossil Calibrations and Constraints: Molecular clocks require calibration points from the geological record. The study used 13 fossil calibrations, including microbial fossils and isotopic evidence [2]. A critical decision was the rejection of the Late Heavy Bombardment (LHB) as a maximum constraint for LUCA's age, as its intensity and even its veracity as a planet-sterilizing event are debated [2]. Instead, the maximum bound was set at the Moon-forming impact (~4.51 Ga), which would have sterilized Earth. The minimum bound was based on low δ98Mo isotope values indicative of oxygenic photosynthesis, dated to 2,954 million years ago (Ma) [2].

Relaxed Clock Models and Data Partitioning: The analysis accounted for the fact that the rate of molecular evolution can vary across lineages and time. It employed both autocorrelated (GBM) and independent-rates (ILN) relaxed-clock models to provide robust confidence intervals [2]. Furthermore, using gene-specific substitution models for the analyzed paralogues, rather than a single model for all genes, provided a significantly better fit to the data and more precise age estimates [8].

Age Estimate and Confidence Intervals

Using a partitioned dataset of five pre-LUCA paralogues, the study arrived at a composite age estimate for LUCA. The results under different clock models were highly consistent [2] [6]:

- GBM model: 4.18 - 4.33 Ga

- ILN model: 4.09 - 4.32 Ga

This consolidated the estimate of LUCA living approximately ~4.2 Ga, with a 95% confidence interval spanning from about 4.09 to 4.33 Ga [2]. This timeline places LUCA firmly within the Hadean Eon, a period previously thought to be too geologically violent for sustained life [5].

Table 1: Key Pre-LUCA Paralogues Used in Molecular Clock Analysis

| Gene Duplicate Pairs | Primary Cellular Function |

|---|---|

| Catalytic & Non-catalytic subunits of ATP synthase [2] | Energy production via ATP synthesis |

| Elongation Factor Tu & G [2] | Protein synthesis |

| Signal Recognition Protein & Signal Recognition Particle Receptor [2] | Protein membrane translocation |

| Tyrosyl-tRNA & Tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetases [2] | Aminoacylation of tRNA |

| Leucyl- & Valyl-tRNA synthetases [2] | Aminoacylation of tRNA |

Reconstructing LUCA's Genome and Physiology

Beyond its age, the nature of LUCA's biology is inferred through phylogenomic reconciliation. This involves comparing modern genomes to reconstruct the genetic repertoire of their common ancestor.

Genomic Reconstruction Methodology

The 2024 study employed a probabilistic gene-tree-species-tree reconciliation algorithm (ALE) to analyze the evolutionary history of nearly 10,000 gene families from the KEGG Orthology (KO) database [2] [7] [9].

- Accounting for Evolutionary Processes: Unlike simpler methods that focus only on universally conserved genes, this approach explicitly models horizontal gene transfer (HGT), gene duplication, and loss [2] [7]. This allows for the inclusion of many more gene families that may have been present in LUCA but were later lost in some descendant lineages or horizontally transferred.

- Probability-Based Gene Assignment: For each gene family, the algorithm calculates a probability of presence (PP) at each node in the species tree, including LUCA [2]. This provides a nuanced and conservative estimate of LUCA's gene content, accounting for uncertainty in deep evolutionary history.

Inferred Genomic and Cellular Complexity

The reconciliation analysis suggests LUCA was far from a primitive, simple entity.

- Genome Size and Proteome: Based on the relationship between KEGG gene families and genome size in modern prokaryotes, LUCA was predicted to have a genome of at least 2.5 Mb, encoding approximately 2,600 proteins [2] [7] [6]. This is comparable in complexity to many modern free-living bacteria and archaea.

- Core Cellular Machinery: The inferred gene set describes a fully-fledged cellular organism with:

- An Early Immune System: The reconstruction found significant support for the presence of CRISPR-Cas genes in LUCA [2] [5] [7]. This indicates LUCA was already engaged in an evolutionary arms race with viruses, confirming that viruses are a primordial feature of life on Earth.

Table 2: Inferred Metabolic Capabilities of LUCA

| Metabolic Pathway/Feature | Inferred Function | Key Enzymes/Components |

|---|---|---|

| Wood-Ljungdahl Pathway | Anaerobic CO2 fixation and energy production [2] [1] | Acetyl-CoA pathway enzymes |

| Energy Source | Chemiosmotic coupling via proton gradients [1] | ATP synthase |

| Electron Donor | Hydrogen (H2) [2] [9] | Hydrogenases |

| Metabolic Flexibility | Organoheterotrophic and/or Chemoautotrophic growth [9] | Glycolysis & Gluconeogenesis enzymes |

| Environmental Preference | Anaerobic [2] | Lack of oxygen-utilizing enzymes |

LUCA's Habitat and Early Earth Environment

The physiological reconstruction of LUCA provides a window into the environment of the early Earth ~4.2 Ga. LUCA is inferred to have been an anaerobic, thermophilic, and acetogenic organism [2] [1] [9].

Its metabolism was dependent on H2 and CO2, with two primary habitats being considered plausible:

- Hydrothermal Vents: Alkaline hydrothermal vents on the seafloor provide a sustained source of H2, CO2, and mineral catalysts, along with natural proton gradients that could have been harnessed for early energy production [5] [7].

- Ocean Surface: Atmospheric photochemistry could have provided a source of hydrogen at the ocean surface, supporting a terrestrial or near-surface ecosystem [2] [9].

Crucially, the complexity of LUCA's metabolism and the presence of a viral immune system suggest it was not living in isolation. It was likely part of an established ecological system [2] [5] [7]. As an acetogen, its waste products would have created niches for other microbial metabolisms, such as methanogens, forming a simple recycling ecosystem. This implies that by 4.2 Ga, life had already diversified into a community of organisms, of which LUCA is the only lineage whose descendants survived to the present day [7].

Research Reagents and Computational Tools for LUCA Studies

The reconstruction of LUCA relies on a suite of bioinformatic tools and genomic resources.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for LUCA Genome Reconstruction

| Resource/Tool | Type | Primary Function in LUCA Research |

|---|---|---|

| KEGG Orthology (KO) [2] | Database | Curated functional annotation of genes and pathways; used for mapping inferred ancestral genes to metabolic functions. |

| Clusters of Orthologous Genes (COG) [2] | Database | An alternative, coarse-grained functional annotation system for gene families. |

| ALE (Amalgamated Likelihood Estimation) [2] | Software Algorithm | Probabilistic gene-tree-species-tree reconciliation; infers gene duplications, transfers, and losses. |

| Relaxed Molecular Clock Models (e.g., MCMCTree) | Software Algorithm | Estimates divergence times by modeling rate variation across lineages, calibrated with fossil data. |

| Universal Paralogous Genes [2] | Genetic Dataset | Pre-LUCA gene duplicates (e.g., ATP synthase subunits) used for cross-braced molecular clock dating. |

Discussion and Future Directions

The estimation of LUCA's age at ~4.2 Ga has profound implications. It suggests that life transitioned from its origin to a complex, prokaryote-grade organism in less than 300 million years after the end of the Hadean bombardment, a geologically short timeframe [5] [7]. This supports the hypothesis that the emergence of microbial life may be a relatively rapid process given the right conditions, thereby increasing the perceived probability of life arising on other planets [5].

However, this field remains dynamic and subject to debate. Some researchers urge caution, noting that molecular clock estimates are sensitive to multiple sources of bias, including the choice of genes, calibrations, and evolutionary models [11] [10]. For instance, analyses of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase genes have suggested a slightly younger, though overlapping, age range of 3.9 - 4.2 Ga [11]. Furthermore, the striking difference in DNA replication machinery between Bacteria and Archaea leads some to propose a simpler, perhaps non-cellular or RNA-genome-based LUCA, complicating the picture of a fully modern prokaryote [1] [10].

Future research will focus on:

- Incorporating More Gene Families: Expanding analyses to include additional ancient gene duplicates to improve the precision of molecular clocks [11].

- Refining Geological Calibrations: Developing more accurate and direct geochemical proxies for the timing of early microbial processes [5].

- Paleo-experimental Validation: Using synthetic biology to resurrect inferred ancestral proteins and test their functions and stability under modeled early Earth conditions [7].

In conclusion, the integration of advanced molecular clock dating with probabilistic genomic reconstruction has provided a detailed, if still inferential, portrait of LUCA. It depicts an ancient, complex, and ecologically integrated ancestor that lived ~4.2 billion years ago, setting the stage for all subsequent evolution on Earth.

The reconstruction of the Last Universal Common Ancestor (LUCA) represents a central endeavor in evolutionary biology, aiming to characterize the primordial organism from which all extant cellular life descends. For decades, the genomic complexity of LUCA has been a subject of vigorous debate, with estimates of its gene content varying widely. A pivotal 2024 study published in Nature Ecology & Evolution has dramatically refined this blueprint, employing advanced phylogenetic reconciliation and molecular dating to infer that LUCA possessed a genome of at least 2.5 megabases (Mb), encoding approximately 2,600 proteins [2] [12]. This finding suggests a level of complexity comparable to modern prokaryotes, challenging earlier perceptions of LUCA as a simple, rudimentary entity and providing a new foundation for understanding the early evolution of life on Earth.

The concept of a last universal common ancestor is endemic to the evolutionary paradigm, representing the node on the tree of life from which the fundamental domains of Archaea and Bacteria diverge [2] [1]. The inference of LUCA's characteristics is not based on fossilized remains but on the comparative analysis of modern genomes, leveraging the principle that universally conserved or widely distributed features among extant life were likely present in their common ancestor [13].

Historically, estimates of LUCA's genomic content have been contentious, ranging from a minimal set of 80-100 orthologous proteins to over 1,500 different gene families [2] [14]. These disparate estimates often stemmed from differing methodological approaches, conceptual frameworks, and the challenge of distinguishing vertical inheritance from horizontal gene transfer [13]. The prevailing view has been skewed by assumptions of gradual complexity increase, leading to hypotheses of a simple, perhaps RNA-based, progenote [14]. However, the application of sophisticated evolutionary models and expansive genomic datasets is now painting a strikingly different picture, revealing a complex, DNA-based organism that had rapidly achieved a sophisticated level of cellular organization [2] [15].

Methodological Framework: Piecing Together an Ancient Genome

Reconstructing a genome that existed billions of years ago requires a multi-faceted approach, combining genomic comparison, phylogenetic modeling, and geochemical calibration. The 2024 study by Moody et al. implemented a comprehensive workflow to overcome previous limitations [2] [15].

Genomic and Phylogenetic Data Acquisition

The research was grounded in a curated genomic dataset representing the breadth of microbial diversity:

- Taxonomic Sampling: The analysis incorporated 700 prokaryotic genomes—comprising 350 Archaea and 350 Bacteria—to ensure a representative sample of modern life descended from LUCA [2] [15].

- Gene Family Analysis: Genes were sorted into families using the KEGG Orthology (KO) database, a resource that provides standardized functional annotations and metabolic pathways [2].

- Species Tree Construction: A robust species tree, essential for accurate reconciliation, was inferred from a set of 57 universal marker genes that are common to all sampled organisms and have resisted horizontal transfer [2].

Phylogenetic Reconciliation and Gene Content Inference

A key innovation was the use of probabilistic gene-tree-species-tree reconciliation, which accounts for the complex evolutionary histories of genes.

- ALE Algorithm: The researchers employed the ALE (Amalgamated Likelihood Estimation) algorithm to compare distributions of bootstrapped gene trees with the reference species tree [2].

- Modeling Evolutionary Events: This method explicitly models the probabilities of gene duplication, horizontal gene transfer (HGT), and loss over time [2].

- Estimating Presence: For each gene family, the algorithm calculated a presence probability (PP) at the LUCA node, providing a statistically rigorous estimate of its likelihood of having been part of LUCA's genomic repertoire [2].

Molecular Dating and Age Estimation

Determining the age of LUCA is critical for contextualizing its evolution. The study employed a "cross-bracing" method to address the inherent challenges of dating the root of the tree of life.

- Pre-LUCA Paralogues: Instead of using universal single-copy genes, the analysis focused on ancient gene duplicates that occurred before LUCA, such as those encoding different subunits of the ATP synthase [2].

- Cross-Bracing Advantage: In these gene trees, the root represents the duplication event, and LUCA is represented by two descendant nodes. This allows the same species divergence calibrations to be applied at least twice, reducing uncertainty in converting genetic distance to absolute time [2].

- Fossil and Geochemical Calibrations: The molecular clock was calibrated using 13 fossil and isotopic records. A minimum bound was set by evidence of oxygenic photosynthesis at ~2.95 Ga, while the maximum bound was set by the Moon-forming impact at ~4.51 Ga, rejecting the idea that the Late Heavy Bombardment was a definitive maximum constraint [2].

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow that led from raw genomic data to the final inference of LUCA's characteristics:

The Genomic Blueprint: Quantitative Findings

The application of this rigorous methodological framework yielded a precise and surprisingly complex genomic blueprint for LUCA.

Genome Size and Protein-Coding Capacity

By applying a predictive model trained on modern prokaryotes, which relates the number of KEGG gene families to total genome size, the study produced concrete estimates [2]:

- Genome Size: The analysis inferred LUCA's genome to be at least 2.5 Mb, with a confidence interval ranging from 2.49 to 2.99 Mb [2] [6].

- Protein-Coding Genes: This genome size corresponds to approximately 2,600 proteins [2] [16].

Table 1: Estimated Genomic Characteristics of LUCA

| Genomic Feature | Inferred Value | Confidence Interval | Comparative Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome Size | 2.5 Megabases (Mb) | 2.49 - 2.99 Mb | Comparable to many free-living modern bacteria and archaea [2] [16]. |

| Number of Proteins | ~2,600 | Not specified | Far exceeds minimal cell estimates (often 300-500 genes) and many prior LUCA reconstructions [2] [14]. |

Key Functional Systems and Metabolic Profile

The probabilistic reconstruction allowed researchers to map LUCA's genomic capabilities to specific cellular functions, revealing a sophisticated physiology [2]:

- Information Processing: LUCA possessed the core machinery for DNA replication, transcription, and translation, indicating a stable DNA-based genetic system [2] [1].

- Metabolism: LUCA was inferred to be an anaerobic acetogen, using the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway to fix carbon and generate energy from hydrogen (H₂) and carbon dioxide (CO₂) [2] [12]. It was capable of nucleotide and amino acid biosynthesis and used ATP as a universal energy currency [2] [17].

- Cellular Structure and Defense: LUCA had a cellular envelope and, remarkably, possessed a primitive, RNA-based immune system (similar to a CRISPR-Cas system) for defense against viruses, indicating an early arms race with mobile genetic elements [2] [17].

Table 2: Key Functional Categories Inferred in LUCA's Genome

| Functional Category | Inferred Capability | Specific Examples / Pathways |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Code & Processing | DNA as genetic material; full transcription & translation | DNA polymerase, ribosomes, tRNA synthetases, elongation factors [2] [1]. |

| Central Metabolism | Anaerobic, H₂-dependent, CO₂-fixing | Wood-Ljungdahl (reductive acetyl-CoA) pathway [2] [12]. |

| Biosynthesis | Nucleotide and protein synthesis | Capability to synthesize amino acids and nucleotides [2]. |

| Energy Currency | Chemiosmotic coupling | ATP synthase, use of ATP [2] [1]. |

| Cellular Defense | Early immune system | CAS-based antiviral defense system [2] [17]. |

The reconstruction of ancient genomes relies on a suite of specialized bioinformatic tools, databases, and evolutionary models.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Resources for LUCA Genomics

| Resource / Tool | Type | Primary Function in LUCA Research |

|---|---|---|

| KEGG Orthology (KO) | Database | Provides standardized gene family annotations and curated metabolic pathways, allowing functional inference of reconstructed genes [2]. |

| ALE (Amalgamated Likelihood Estimation) | Software Algorithm | Performs probabilistic reconciliation of gene trees with a species tree, modeling gene duplication, transfer, and loss to infer ancestral gene content [2]. |

| Molecular Clock Models (e.g., GBM, ILN) | Evolutionary Model | Used in divergence time analysis to estimate the age of evolutionary events by translating genetic mutations into geological time, calibrated with fossils [2]. |

| Pre-LUCA Paralogs | Genetic Data | Gene duplicates (e.g., in ATP synthase) that predate LUCA; used in "cross-bracing" molecular dating to overcome challenges of rooting the universal tree [2]. |

| Prokaryotic Genomes (Archaea & Bacteria) | Genomic Data | The raw comparative data; a broad and diverse sampling is crucial for accurate reconstruction of deep evolutionary history [2] [15]. |

Implications and Future Directions

The finding of a 2.5 Mb, 2,600-protein genome in LUCA has profound implications for our understanding of early evolution. It indicates that the transition from the origin of life to a complex, prokaryote-grade organism occurred with remarkable speed, within a few hundred million years of Earth's formation [2] [15]. This "rapid complexity" scenario challenges gradualistic evolutionary models and suggests that the foundational cellular systems were established very early [16].

Furthermore, the reconstruction of LUCA as an organism integrated into an ecosystem—its waste products serving as substrates for other microbes—transforms the view of early Earth from a barren world with isolated cells to one hosting a modestly productive recycling ecosystem [2] [17]. Future work will focus on incorporating newly discovered microbial diversity, improving evolutionary models to better account for HGT, and integrating genomic inferences with geochemical constraints to further refine the portrait of our most ancient ancestor.

The Last Universal Common Ancestor (LUCA) represents the primordial organismal population from which all extant bacterial, archaeal, and eukaryotic life descends [1]. Reconstructing the physiological profile of LUCA is a fundamental pursuit in evolutionary biology, providing critical insights into the conditions of early Earth and the nature of the earliest cellular life. Contemporary research, leveraging advanced genomic and phylogenetic methodologies, increasingly converges on a model of LUCA as an anaerobic, acetogenic organism with a complex metabolism that inhabited a geochemically active environment [2] [18]. This whitepaper synthesizes recent findings on LUCA's physiological characteristics, emphasizing the genomic and experimental evidence supporting an acetogenic metabolism, and details the methodological frameworks enabling these inferences for a research-oriented audience.

Metabolic Profile and Core Physiology

Central Energy and Carbon Metabolism

Inferences from phylogenomic analyses suggest LUCA possessed a core set of metabolic pathways that allowed it to thrive in an anaerobic, hydrogen-rich environment. The central energy metabolism likely revolved around the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway (reductive acetyl-CoA pathway), a foundational mechanism for carbon fixation and energy conservation in anaerobic microbes [18] [19].

- Wood-Ljungdahl Pathway: This pathway enables both CO2 fixation and the generation of acetyl-CoA for energy production. LUCA likely used H2 as an electron donor to reduce CO2, a process coupled to energy conservation via acetogenesis [2] [19]. The presence of key enzymes like bifunctional acetyl-CoA-synthase/CO-dehydrogenase is strongly supported by phylogenetic studies [19].

- Additional Metabolic Modules: Genomic reconstructions indicate LUCA's metabolic repertoire included glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, a nearly complete citric acid cycle, and the pentose phosphate pathway [18]. These pathways provided essential precursors for biosynthesis and flexibility in carbon and energy management.

- Nutrient Assimilation: Evidence suggests LUCA was capable of nitrogen fixation, a critical function in the anoxic, likely nitrogen-limited early Earth environments [1].

Table 1: Core Metabolic Pathways Inferred in LUCA

| Metabolic Pathway | Key Enzymes/Components | Physiological Role | Inference Strength |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wood-Ljungdahl (Acetogenesis) | CO dehydrogenase/acetyl-CoA synthase, Corrins, FeS clusters | Energy conservation, CO2 fixation, acetyl-CoA production | Strong [2] [18] [19] |

| Gluconeogenesis | PEP carboxykinase, Fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase | Sugar biosynthesis from non-carbohydrate precursors | Strong [18] [1] |

| Nitrogen Fixation | Nitrogenase complex | Assimilation of atmospheric N2 | Moderate [1] |

| Reverse Krebs Cycle | ATP-citrate lyase, Ferredoxin-dependent enzymes | Anabolic carbon fixation | Proposed [1] |

Physiological State and Environmental Niche

LUCA's physiological profile points to a specific ecological niche. The consistent inference of anaerobicity and a biochemistry replete with iron-sulfur (FeS) clusters and radical reaction mechanisms suggests an origin in an environment devoid of oxygen but rich in geochemically supplied H2, CO2, and transition metals [2] [1].

- Anaerobic and Thermophilic: LUCA is reconstructed as a strict anaerobe, consistent with an atmosphere lacking free oxygen. Its hypothesized thermophily is supported by its inferred proximity to modern thermophilic lineages like methanogens and clostridia in phylogenetic trees [1] [19].

- Ion Gradient Utilization: LUCA likely possessed a rotor-stator ATP synthase for generating ATP using chemiosmotic principles [19]. While it may have lacked complex redox-driven ion pumps like cytochromes and quinones, it appears to have had an Mrp-type H+/Na+ antiporter [19]. This complex could transduce natural proton gradients (e.g., from alkaline hydrothermal vents) into biologically more stable sodium ion gradients, powering cellular processes.

- Cellular Defense Systems: A striking finding from recent genomic reconstructions is the probable presence of a CRISPR-Cas system in LUCA, indicating an early evolutionary arms race with viruses and the existence of a sophisticated immune system from life's earliest stages [2] [18].

Table 2: Inferred Physiological and Genomic Traits of LUCA

| Trait Category | Inferred Characteristic | Modern Analogues | Key Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Habitat | Anaerobic, hydrothermal, H2/CO2-rich | Methanogens, Acetogenic Clostridia | Phylogenetic profiling of ancient gene families [2] [19] |

| Genome Size | ~2.5 Mb (encoding ~2,600 proteins) | Modern free-living prokaryotes | Predictive modeling from gene family counts [2] |

| Energy Conservation | Chemiosmosis, Acetogenesis, Mrp antiporter | Clostridium, Moorella | Presence of ATP synthase and Mrp complex subunits [2] [19] |

| Genetic Machinery | DNA genome, ribosomes, tRNA, CRISPR-Cas | Universal cellular life | Universal gene distribution and phylogenetic analysis [2] [1] |

Genome Reconstruction Methodologies

Phylogenetic Reconciliation and Gene Content Inference

Determining LUCA's gene content requires sophisticated computational methods to distinguish genes inherited via vertical descent from those acquired through horizontal gene transfer (HGT).

- Probabilistic Gene-Species Tree Reconciliation: Advanced algorithms, such as the Amalgamated Likelihood Estimation (ALE) method, are employed [2] [18]. This approach compares distributions of bootstrapped gene trees for thousands of gene families against a reference species tree to probabilistically infer events of gene duplication, transfer, and loss throughout history.

- Determining LUCA Presence Probability: For each gene family, the reconciliation model calculates a probability of presence (PP) at the LUCA node. A conservative set of genes can be identified by applying a high PP threshold (e.g., PP > 0.95), while the total number of proteins in LUCA's genome can be estimated using predictive models that relate gene family counts to total proteome size in modern prokaryotes [2].

Molecular Dating of LUCA

Establishing a timeline for LUCA's existence is methodologically challenging. A robust approach utilizes pre-LUCA universal paralogues – genes that duplicated prior to LUCA, with both copies present in its genome [2] [18].

- Universal Paralog Analysis: Genes like the catalytic and non-catalytic subunits of ATP synthases and specific aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases are used. In their phylogenetic trees, the root represents the pre-LUCA duplication event, and LUCA is represented by two descendant nodes [2].

- Cross-bracing Molecular Clock Calibration: This method involves applying fossil calibrations to the same species divergence events represented on both sides (paralogs) of the gene tree. This "cross-bracing" doubles the calibration points and reduces uncertainty when converting genetic distances into absolute time [2].

- Fossil Calibrations: Analyses are calibrated using microbial fossils and isotopic records. A minimum bound is often set by oxygenic photosynthesis evidence (~2.95 Ga), while a maximum bound is set by the Moon-forming impact (~4.51 Ga), rejecting the idea that a late heavy bombardment would have sterilized Earth and precluded an earlier LUCA [2]. This approach yields an age estimate for LUCA of approximately 4.2 Ga (4.09 - 4.33 Ga) [2] [18].

Experimental Protocols and Validation

Phylogenomic Protocol for Gene Content Inference

This protocol outlines the key steps for inferring LUCA's gene content from genomic data.

Step 1: Genomic Data Acquisition and Curation

- Objective: Assemble a high-quality, phylogenetically diverse set of prokaryotic genomes.

- Procedure: Sample at least 700 genomes (350 Archaea, 350 Bacteria) from public databases, ensuring representation of major lineages including TACK/Asgard archaea and Gracilicutes bacteria [2]. Annotate genomes using standardized databases like KEGG Orthology (KO) or Clusters of Orthologous Genes (COGs) [2].

Step 2: Species Tree Reconstruction

- Objective: Build a robust reference species tree.

- Procedure: Concatenate a core set of ~57 universal, single-copy marker genes (e.g., ribosomal proteins). Perform maximum likelihood phylogenetic analysis using software like IQ-TREE or RAxML. Account for phylogenetic uncertainty, particularly in the placement of small-genome lineages like DPANN and CPR [2].

Step 3: Gene Tree Reconciliation

- Objective: Reconstruct the evolutionary history of each gene family.

- Procedure: For each KO or COG family, generate a distribution of gene trees using bootstrapping. Reconcile these gene trees with the reference species tree using the ALE algorithm or similar to infer the most probable history of duplications, transfers, and losses [2].

Step 4: LUCA Genome Estimation

- Objective: Determine the set of genes present in LUCA and estimate total genome size.

- Procedure: Extract the probability of presence at the LUCA node for all gene families. Apply a conservative threshold to define a high-confidence gene set. Use a regression model trained on modern prokaryotes (relating gene family count to total proteome size) to estimate LUCA's total number of proteins from its count of conserved gene families [2].

Protocol for Ancestral rRNA Sequence Reconstruction

Reconstructing ancestral biomolecules like rRNA provides functional insights beyond gene content.

Step 1: Taxon Sampling and Alignment

- Objective: Collect a comprehensive set of rRNA sequences.

- Procedure: Sample 16S, 5S, and 23S rRNA sequences from over 500 species spanning archaeal and bacterial phyla. Align sequences using tools like MAFFT, with manual optimization based on secondary structure information [20].

Step 2: Phylogenetic Analysis

- Objective: Construct a highly resolved tree for ancestral sequence reconstruction.

- Procedure: Generate a concatenated alignment of rRNA genes and/or universal proteins. Perform phylogenetic analysis with high bootstrap replicates to ensure node support, especially at deep branches [20].

Step 3: Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction

- Objective: Infer the most probable nucleotide sequence for LUCA's rRNAs.

- Procedure: Use maximum likelihood or Bayesian methods on the resolved phylogenetic tree to reconstruct the full-length ancestral sequences of 16S, 5S, and 23S rRNAs at the LUCA node [20].

Step 4: Bioinformatic Analysis of Ancestral Sequences

- Objective: Identify structural and functional motifs in the ancestral rRNAs.

- Procedure: Search for repeated short sequence motifs within and between the reconstructed ancestral rRNAs. Analyze their conservation across modern lineages and map their positions to known functional sites of the ribosome (e.g., peptidyl transferase center) to infer evolutionary origins [20].

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Resources for LUCA Research

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic & Protein Databases | KEGG Orthology (KO), Clusters of Orthologous Genes (COGs), NCBI GenBank, GTDB | Standardized functional annotation of genes; taxonomic classification; source of sequence data for phylogenetic analysis [2] [21]. |

| Phylogenetic Software | IQ-TREE, RAxML, ALE, Orthograph | Performing maximum likelihood tree inference; reconciling gene and species trees; identifying orthologous genes across species [2] [20]. |

| Molecular Clock Software | MCMCTree (PAML), BEAST2 | Estimating divergence times using probabilistic models with fossil and geochemical calibrations [2]. |

| Sequence Alignment Tools | MAFFT, GBlocks | Creating and refining multiple sequence alignments, including removal of ambiguously aligned regions [20]. |

| Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction | Code in PAML, IQ-TREE | Inferring the nucleotide or amino acid sequences of ancestral nodes (e.g., LUCA) on a given phylogenetic tree [20]. |

| Metagenomic Assembled Genomes (MAGs) | Rhodobacterales MAGs, other environmental MAGs | Providing genomic data from diverse, often uncultured microbial lineages to improve the representation of the tree of life [21]. |

The prevailing narrative of the last universal common ancestor (LUCA) as a solitary, primitive entity has been fundamentally overturned by contemporary genomic reconstructions. Current research depicts LUCA as a sophisticated member of an established ecological system. Advanced phylogenetic analyses infer that LUCA possessed a genome of considerable complexity and was part of a microbial community characterized by metabolic interdependence, viral predation, and horizontal gene transfer. This ecological context is no longer a peripheral detail but a central tenet for accurate interpretation of LUCA's biology and the early evolution of life on Earth.

LUCA's Genomic and Metabolic Profile

Phylogenetic reconciliation of modern genomes provides a quantitative glimpse into LUCA's biological capacity, revealing an organism with genomic complexity comparable to many modern prokaryotes.

Table 1: Inferred Genomic and Metabolic Characteristics of LUCA

| Feature | Inferred Characteristic | Method of Inference / Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Genome Size | ~2.5 Mb (2.49 - 2.99 Mb) [2] | Phylogenetic reconciliation & probabilistic mapping of gene families [2] |

| Protein-Coding Capacity | ~2,600 proteins [2] | Predictive model based on relationship between gene families & proteins in modern prokaryotes [2] |

| Metabolic Type | Anaerobic, H(_2)-dependent acetogen [2] [1] | Presence of Wood-Ljungdahl (reductive acetyl-CoA) pathway for carbon fixation & energy production [2] [1] |

| Estimated Age | ~4.2 Ga (4.09 - 4.33 Ga) [2] | Divergence time analysis of pre-LUCA gene duplicates, cross-braced with microbial fossils & isotope records [2] |

| Cellular Defense | Early CRISPR-Cas-like immune system [2] [5] | Inference of viral defense machinery, indicating pressure from viral predators in the environment [2] [5] |

Methodologies for Reconstructing LUCA's Ecology

Inferring the ecology of an organism that left no physical fossils relies on sophisticated computational and comparative techniques applied to the genomes of its modern descendants.

Table 2: Key Experimental and Bioinformatic Protocols in LUCA Research

| Methodology | Protocol Description | Application in LUCA Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Phylogenetic Reconciliation | Uses algorithms (e.g., ALE) to compare distributions of bootstrapped gene trees with a reference species tree, inferring gene duplications, transfers, and losses (DTL) [2]. | Probabilistically maps gene families to ancestral nodes, estimating the probability a gene was present in LUCA, accounting for horizontal gene transfer [2]. |

| Molecular Clock Dating | Estimates divergence times by calculating genetic distance calibrated with fossil or geochemical records. "Cross-bracing" uses gene duplicates to reduce uncertainty [2]. | Dated LUCA to ~4.2 Ga using universal paralogues, with calibrations from the Moon-forming impact and early oxygenic photosynthesis fossils [2]. |

| Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction | Infers the most likely nucleotide or amino acid sequences of ancestral genes based on phylogenetic trees and modern sequences [20]. | Used to reconstruct full-length 16S, 5S, and 23S rRNA sequences of LUCA to explore evolutionary origins [20]. |

Workflow for Genomic Reconstruction of LUCA's Ecology

The following diagram outlines the integrated logical workflow researchers use to move from raw genomic data to an ecological model of LUCA.

The Early Ecosystem: An Interdependent Biosphere

The reconstruction of LUCA's genes points directly to its existence within a complex ecological network, not in isolation.

Metabolic Interdependence: As an acetogen, LUCA's metabolism would have produced complex organic compounds. These outputs created niches for other community members, such as methanogens that consume waste products like H₂ [2] [5]. This interplay established early resource recycling loops, increasing the overall productivity of the ecosystem [5].

Viral Predation and Genetic Exchange: The inferred presence of a CRISPR-Cas-like system provides direct evidence that LUCA faced pressure from viral predators [2] [5]. This virosphere was likely a key driver of ecological dynamics. Beyond being predators, viruses acted as vectors for horizontal gene transfer (HGT), creating a genetic "web" and accelerating diversity within the community [5].

Environmental Setting: LUCA's anaerobic, H₂-dependent metabolism is consistent with life in environments like hydrothermal vents, which provide abundant geochemical energy [1] [5]. The existence of a community suggests that early ecosystems could have exploited multiple niches within these environments.

Table 3: Essential Resources for LUCA Genomics Research

| Research Reagent / Resource | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| KEGG Orthology (KO) Database [2] | Curated database of orthologous gene groups; used to assign functional annotations to inferred ancestral genes and reconstruct metabolic pathways. |

| Clusters of Orthologous Genes (COGs) [2] | A more coarse-grained set of orthologous groups; used as a complementary resource to KO for inferring gene content in deep ancestors. |

| ALE (Amalgamated Likelihood Estimation) [2] | Probabilistic algorithm for reconciling gene trees with species trees; models gene Duplication, Transfer, and Loss (DTL) to infer gene presence in ancestors. |

| Molecular Clock Calibrations [2] | Fossil and geochemical evidence (e.g., isotope records, stromatolites) used to calibrate the rate of genetic evolution and estimate divergence times. |

| SSU rRNA Gene Sequences [20] | Highly conserved genes (e.g., 16S rRNA); fundamental for constructing the backbone phylogeny of cellular life and for ancestral sequence reconstruction. |

Implications and Future Directions

The ecological view of LUCA has profound implications. It suggests that the transition from the origin of life to a functional biosphere was geologically rapid, occurring within the first few hundred million years of Earth's history [2] [5]. This rapid emergence implies that given the right conditions, life may be an almost inevitable planetary process [5].

Future research will focus on:

- Refining Community Structure: Using more sophisticated models to infer the specific metabolic roles of other members of LUCA's community.

- Testing Environmental Hypotheses: Integrating genomic inferences with geochemical models to better constrain LUCA's physical habitat.

- Exploring the Virosphere: Understanding the precise role of ancient viruses in shaping LUCA's genome and ecosystem through HGT.

Recent phylogenomic studies have fundamentally reshaped our understanding of antiviral defense in primordial life. Groundbreaking research into the last universal common ancestor (LUCA) has revealed the presence of a sophisticated, RNA-based immune system, marking the deep evolutionary origins of CRISPR-Cas machinery. This whitepaper synthesizes findings from cutting-edge genomic reconstructions and molecular dating analyses, which establish that LUCA possessed a functional, albeit primordial, CRISPR system approximately 4.2 billion years ago. We detail the quantitative evidence for this system's protein composition, its proposed functional mechanisms, and the advanced phylogenetic methodologies that enabled this discovery. Furthermore, we present a structured repository of research reagents to facilitate experimental inquiry into this ancient immune machinery, providing a critical resource for researchers and drug development professionals exploring the foundational principles of cellular immunity.

The last universal common ancestor (LUCA) represents the most recent population of organisms from which all extant bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes descend. Long conceptualized as a simple, primitive entity, LUCA has been progressively reconstructed as a complex organism with a genome encoding thousands of proteins and a sophisticated metabolic network [2] [18]. A pivotal discovery in this reconstruction is evidence of an early adaptive immune system, a finding that fundamentally alters our perception of life's earliest evolutionary struggles.

The CRISPR-Cas system (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats and CRISPR-associated proteins) is recognized as an adaptive immune mechanism in prokaryotes. It provides sequence-specific protection against mobile genetic elements (MGEs) such as viruses and plasmids by integrating fragments of foreign DNA into host genomes, which are then used to target and cleave subsequent invasions [22] [23]. The recent tracing of core CRISPR components to LUCA indicates that the evolutionary arms race between cells and viruses is as old as cellular life itself, dating back nearly to the formation of Earth itself [24] [2].

LUCA Genome Reconstruction and the Identification of Immune Genes

Methodological Framework for Ancestral State Reconstruction

Inferring the genetic repertoire of an organism that existed billions of years ago requires sophisticated computational approaches that account for extensive evolutionary forces. The landmark study by Moody et al. (2024) employed a rigorous phylogenetic reconciliation workflow to achieve this [2].

- Genomic Dataset Curation: The analysis began with the construction of a robust species phylogeny using 57 universal marker genes from a broad taxonomic sample of 700 modern microbes (350 bacteria and 350 archaea) [2].

- Phylogenetic Reconciliation with ALE: Researchers employed the Probabilistic Gene-Species Tree Reconciliation Algorithm (ALE) to analyze the evolutionary history of 9,365 protein families from the KEGG Orthology database [2] [18]. This method compares distributions of bootstrapped gene trees to the established species tree, explicitly modeling key evolutionary events:

- Gene Duplication

- Horizontal Gene Transfer (HGT)

- Gene Loss

- Presence Probability Calculation: For each protein family, the algorithm calculated a posterior probability (PP) of its presence in LUCA. This probabilistic framework allows for a more nuanced reconstruction than binary presence/absence calls, accounting for uncertainty in deep evolutionary histories [2].

This workflow is summarized in the diagram below:

Key Genomic Findings

This robust methodological framework yielded a high-resolution portrait of LUCA's genomic capacity:

- Genome Size and Proteome: LUCA's genome was estimated at 2.5 Mb (2.49-2.99 Mb), encoding approximately 2,600 proteins (2,451-2,855). This scale is comparable to many modern free-living prokaryotes, indicating a complex cellular organism [2] [25].

- Temporal Context: Molecular clock analysis, calibrated using pre-LUCA gene duplicates and microbial fossils, dated LUCA to ~4.2 billion years ago (4.09-4.33 Ga). This places its existence merely a few hundred million years after Earth's formation and the Moon-forming impact, suggesting a rapid transition from prebiotic chemistry to complex biology [2].

- Identification of Immune Components: Among the high-probability gene families were those encoding core components of a Class 1 CRISPR-Cas system. The analysis identified 19 Class 1 CRISPR–Cas effector protein families in LUCA's genome, including signatures of Type I (e.g., Cas3, Cas10) and Type III (e.g., Cas7) systems. Notably, the central adaptation proteins Cas1 and Cas2 were absent, suggesting LUCA's system was an incomplete, yet functional, effector module [24].

Table 1: Key Genomic and Temporal Characteristics of LUCA

| Feature | Reconstructed Characteristic | Method of Inference | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 4.2 Ga (4.09 - 4.33 Ga) | Molecular clock analysis of pre-LUCA paralogues | [2] |

| Genome Size | ~2.5 Mb (2.49 - 2.99 Mb) | Predictive modeling based on gene family counts | [2] [25] |

| Proteome Size | ~2,600 proteins (2,451 - 2,855) | Phylogenetic reconciliation (ALE) of KEGG families | [2] [18] |

| CRISPR System Class | Class 1 (multisubunit effector) | Presence of 19 effector protein families (e.g., Cas3, Cas7, Cas10) | [24] |

| CRISPR System Type | Type I and Type III | Signature gene content and organization | [24] |

| Adaptation Module | Absent (No Cas1, Cas2) | Gene tree reconciliation and absence inference | [24] |

The Nature of the Primordial CRISPR-Cas System

System Classification and Genomic Architecture

The CRISPR-Cas systems are broadly classified into two classes. Class 1 systems utilize multisubunit effector complexes, while Class 2 systems employ a single, large effector protein (e.g., Cas9) [22] [26]. The immune machinery identified in LUCA is unequivocally a Class 1 system, specifically featuring components of Type I and Type III effector modules [24].

The defining characteristic of LUCA's system is the presence of the effector complex proteins alongside the absence of the adaptation machinery (Cas1-Cas2). This suggests a system that could utilize existing spacers for defense but may have lacked the ability to acquire new ones autonomously, potentially relying on horizontal gene transfer for spacer repertoire renewal [24] [22].

Proposed Functional Mechanism

Based on the conserved functions of its component proteins in modern organisms, LUCA's CRISPR system likely operated through a simplified, RNA-guided defense mechanism, as illustrated below:

- Pre-existing Immunity: LUCA's genome contained CRISPR arrays with spacers acquired from prior encounters with mobile genetic elements [22] [27].

- Effector Complex Assembly & crRNA Processing: The CRISPR array was transcribed into a long pre-crRNA. The multisubunit effector complex (containing proteins like Cas7, Cas10, etc.) then processed this transcript into mature crRNA (CRISPR RNA) guides [22] [28].

- Interference & Viral Defense: The crRNA, bound to the effector complex, guided it to complementary nucleic acid sequences from invading viruses. The complex then mediated the cleavage and inactivation of the foreign genetic material, protecting the cell from infection. Given the presence of Type III components, this system may have targeted RNA, DNA, or both, and potentially possessed a secondary signaling function [22] [26].

The functional characteristics of this ancestral system are summarized in the table below.

Table 2: Characteristics of the Primordial CRISPR-Cas System in LUCA

| Feature | Inference in LUCA | Functional Implication | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| System Class | Class 1 | Multisubunit effector complex; more ancient than Class 2 | [24] [22] |

| System Types | Type I & III | RNA-guided DNA/RNA targeting and cleavage; potential signal transduction | [24] |

| Key Present Genes | cas3, cas7, cas10 | Core components for target recognition, cleavage, and complex scaffolding | [24] |

| Key Absent Genes | cas1, cas2 | Inability for de novo spacer acquisition; reliance on pre-existing immunity | [24] |

| Primary Function | RNA-based adaptive immunity | Defense against viruses and other mobile genetic elements | [24] [2] |

| Target Molecule | Likely DNA and/or RNA | Versatile defense strategy against different genetic parasites | [22] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Experimental Approaches

Investigating the functional properties of LUCA's CRISPR system requires a specialized set of computational and molecular biology tools. The following table details essential reagents and their applications in this field.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Investigating Ancient CRISPR Systems

| Reagent / Resource | Category | Key Function in Research | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Universal Marker Genes | Genomic Dataset | Species phylogeny construction for reconciliation analysis | 57 genes used in Moody et al. [2] |

| KEGG/COG Databases | Protein Family Database | Curated orthologous groups for gene family definition | KEGG Orthology (KO) used in primary reconstruction [2] |

| ALE Software | Computational Algorithm | Probabilistic gene tree-species tree reconciliation | Infers gene duplications, transfers, and losses [2] [18] |

| Cas Protein Effectors | Molecular Biology Reagent | Functional characterization of ancestral enzyme activity | Recombinant Cas7, Cas10 for in vitro assays [26] |

| Synthetic crRNA/tracrRNA | Nucleic Acid Reagent | Guide RNA for directing Cas protein activity in functional studies | Chemically synthesized; used to test targeting specificity [23] [28] |

| Metagenomic Libraries | Genomic Resource | Discovery of novel, low-abundance CRISPR variants from diverse environments | Source for identifying "long-tail" of CRISPR diversity [26] |

The reconstruction of a functional CRISPR-Cas system within LUCA represents a paradigm shift in our understanding of early evolution. It provides compelling evidence that the conflict between cells and viral parasites was a major selective pressure that shaped the biology of the earliest life forms over 4.2 billion years ago. The presence of this sophisticated defense mechanism confirms that LUCA was not a simple, nascent entity but a complex organism embedded in a dynamic ecosystem where adaptive immunity provided a critical survival advantage.

Future research will focus on several key areas:

- Functional Resurrection: Expressing and assaying the biochemical activities of reconstructed ancestral Cas proteins in vitro to validate their proposed mechanisms.

- Ecosystem Context: Further exploring the nature of the viral and microbial ecosystem that LUCA inhabited, potentially through the analysis of conserved viral genomic signatures in ancient prokaryotic lineages.

- Evolutionary Trajectory: Elucidating the precise evolutionary pathway from LUCA's Class 1 system to the diverse array of CRISPR types, including the evolution of the Cas1-Cas2 adaptation module from casposons and the later emergence of Class 2 systems [22] [26].

This deep-time perspective on cellular immunity not only enriches our knowledge of life's origins but also provides an evolutionary framework for understanding the principles of modern immune systems and their applications in biotechnology and medicine.

Reconstructing LUCA: Advanced Phylogenetic and Computational Genomic Techniques

Dating the divergence of the last universal common ancestor (LUCA) is fundamental to understanding the early evolution of life on Earth. Molecular clock analyses provide the primary method for estimating these deep evolutionary timescales. However, dating the root of the tree of life presents unique challenges, as errors can propagate from the tips to the root, and the rate of evolution for the branch incident to the root node is difficult to estimate [2]. The analysis of pre-LUCA gene duplicates offers a powerful solution to these problems, enabling more precise and reliable estimation of LUCA's age [2] [29]. This guide details the core concepts and methodologies for using these paralogous genes in molecular clock dating, framed within the context of LUCA genome reconstruction research.

Theoretical Foundation

The Pre-LUCA Paralog Approach

The pre-LUCA paralog method leverages genes that underwent duplication before the existence of LUCA, resulting in two or more copies being present in LUCA's genome [2] [29]. In phylogenetic trees of these genes, the root represents the duplication event predating LUCA, while LUCA itself is represented by two descendant nodes [2]. This structure provides two key advantages:

- Cross-Bracing: The same species divergence events are represented on both sides of the gene tree. When a shared node is assigned a fossil calibration, this cross-bracing effectively doubles the number of calibrations on the phylogeny, significantly improving the precision of divergence time estimates [2].

- Reduced Root Uncertainty: By shifting the root of the analysis to an older duplication event, this method circumvents the difficulties associated with directly dating the LUCA node itself [2].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship and workflow for utilizing pre-LUCA paralogues in divergence time estimation.

Criteria for Selecting Pre-LUCA Paralogs

Selecting appropriate gene families is critical. The pairs of universal paralogues used in recent analyses include [2] [29]:

- Catalytic and non-catalytic subunits from ATP synthase (ATP)

- Elongation Factor Tu and G (EF)

- Signal Recognition Protein and Signal Recognition Particle Receptor (SRP)

- Tyrosyl-tRNA and Tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetases (Tyr)

- Leucyl- and Valyl-tRNA synthetases (Leu)

These gene families were selected based on previous work indicating a likely duplication event before LUCA. The selection process involves rigorous filtering to remove non-homologous sequences, horizontal gene transfers, and sequences with exceptionally long branches [29].

Experimental and Computational Protocols

Gene Family Identification and Curation

Objective: To identify and curate pairs of paralogous gene families that duplicated before LUCA.

Methodology:

- Gene Family Identification: Use BLAST to identify potential homologs of the target paralog pairs (e.g., ATP synthase subunits) from genomic databases like NCBI [29].

- Sequence Alignment: Perform multiple sequence alignment for each gene family using tools like MUSCLE [29].

- Alignment Trimming: Refine the alignments with TrimAl (using the

-strictoption) to remove poorly aligned regions [29]. - Gene Tree Inference: Infer individual gene trees using maximum likelihood software such as IQ-TREE2 under a suitable substitution model (e.g., LG+C20+F+G4) [29].

- Tree Curation: Manually inspect and curate trees to remove:

- Non-homologous sequences

- Horizontal gene transfers

- Exceptionally short or long sequences

- Extremely long branches

- Recent paralogues or taxa of inconsistent placement identified with RogueNaRok [29].

- Independent Verification: Verify the deep archaeal or bacterial split using methods like minimal ancestor deviation [29].

Output: A curated set of gene alignments and corresponding trees for each paralogous family.

Molecular Clock Analysis with MCMCtree

Objective: To estimate divergence times using the curated paralogous genes under a Bayesian framework.

Methodology:

- Fixed Topology: Use a fixed, best-scoring maximum likelihood tree inferred from the concatenated or partitioned alignment as the base topology for dating [29].

- Fossil Calibrations: Incorporate fossil calibration information using carefully justified probability densities to constrain node ages. Critical calibrations for LUCA analyses include:

- Cross-Bracing Strategies: Implement one of three calibration strategies in the MCMCtree control file [29]:

- Cross-bracing A: Cross-brace all nodes that correspond to the same speciation event.

- Cross-bracing B: Cross-brace only nodes for which there is a direct fossil constraint.

- No cross-bracing: Use conventional calibration without mirroring node ages.

- Rate Prior Specification: Infer a mean evolutionary rate using

BASEMLorCODEMLto specify a sensible rate prior in MCMCtree [29]. - Relaxed Clock Models: Perform dating analyses under both the geometric Brownian motion (GBM) and the independent-rates log-normal (ILN) relaxed-clock models to test the robustness of the results [29].

- MCMC Execution: Run MCMCtree with the approximate likelihood calculation enabled to improve computational efficiency [29].

- Diagnostics: Assess MCMC convergence using tools like Tracer to ensure effective sample sizes (ESS) for all parameters are sufficient (>200).

Output: Posterior distributions of node ages, including the age of the pre-LUCA duplication and the subsequent LUCA divergence.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Key Quantitative Findings from Recent Studies

Recent application of these methods has yielded precise age estimates for LUCA, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: LUCA Age Estimates from Bayesian Molecular Clock Analyses using Pre-LUCA Paralogs

| Relaxed Clock Model | Data Type | Calibration Strategy | LUCA Age Estimate (Ga) | Credible Interval (Ga) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geometric Brownian Motion (GBM) | Partitioned Alignment | Cross-bracing A | ~4.2 | 4.18 - 4.33 | [2] [29] |

| Independent-rates Log-normal (ILN) | Partitioned Alignment | Cross-bracing A | ~4.2 | 4.09 - 4.32 | [2] [29] |

| GBM | Concatenated Alignment | Cross-bracing A | ~4.2 | 4.17 - 4.32 | [29] |

| ILN | Concatenated Alignment | Cross-bracing A | ~4.2 | 4.08 - 4.31 | [29] |

Table 2: Impact of Analysis Settings on Divergence Time Estimates

| Setting | Impact on Precision and Accuracy |

|---|---|

| Partitioned vs. Concatenated Data | Partitioned analysis accounts for locus-specific evolutionary rates, generally improving accuracy [29]. |

| Cross-bracing (A vs. B vs. None) | Cross-bracing A (full) most effectively reduces uncertainty by doubling calibrations for mirrored nodes [2] [29]. |

| Clock Model (GBM vs. ILN) | GBM and ILN models can produce slightly different credible intervals; running both tests robustness [29]. |

| Number of Loci | Increasing the number of loci reduces variance in time estimates, approaching an infinite-data limit [30]. |

Reconciliation with Genomic and Paleontological Data

Beyond dating, phylogenetic reconciliation of these gene families can infer LUCA's genomic complexity. A recent study using the probabilistic algorithm ALE suggests LUCA possessed a genome of at least 2.5 Mb, encoding approximately 2,600 proteins [2]. This indicates a complex organism, already equipped with core cellular machinery and even an early immune system, living within an established ecosystem [2] [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Pre-LUCA Molecular Clock Analysis

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| NCBI Database | Genomic data repository | Source for raw sequence data of target gene families [29]. |

| BLAST | Sequence homology search | Identifying homologs of pre-LUCA paralogs across species [29]. |

| MUSCLE | Multiple sequence alignment | Aligning homologous sequences for phylogenetic analysis [29]. |

| TrimAl | Alignment trimming | Refining alignments by removing poorly aligned positions [29]. |

| IQ-TREE 2 | Maximum likelihood phylogeny inference | Inferring best-scoring tree topology for fixed-tree dating [29]. |

| PAML (MCMCtree) | Bayesian divergence time estimation | Core software for molecular clock analysis under relaxed clocks [29]. |

| PAML (CODEML) | Codon substitution model analysis | Calculating branch lengths, gradient, and Hessian for approximate likelihood [29]. |

| Tracer | MCMC diagnostics | Assessing convergence and effective sample size of MCMC chains [31]. |

| ALE | Phylogenetic reconciliation | Inferring gene family origins and LUCA's gene content [2]. |

The use of pre-LUCA paralogues represents a significant methodological advance in molecular clock dating, providing a more stable and calibrated framework for estimating the age of LUCA. The consistent results pointing to a LUCA age of approximately 4.2 billion years [2] [5] challenge previous assumptions about the timeline of early evolution. They suggest that life achieved a sophisticated, prokaryote-grade level of complexity remarkably quickly after Earth's formation, with implications for the probability of life arising on other planets [5]. This technical approach, integrating cross-bracing, careful fossil calibration, and sophisticated clock models, is now the standard for resolving deep evolutionary timelines.

Phylogenetic reconciliation is a computational approach that connects the evolutionary histories of different biological entities, most commonly a gene tree and a species tree. Its primary goal is to explain the discrepancies between these trees by inferring a series of evolutionary events, thereby providing a detailed scenario of how gene families have evolved within the context of species divergence [32] [33]. The core idea is to draw the gene tree within the species tree, revealing their interdependence and the events that have marked their shared history [32]. This method was originally developed in the 1980s to model the coevolution of genes and genomes, as well as hosts and symbionts [32]. The development of the Duplication-Transfer-Loss (DTL) model, which accounts for gene duplication, horizontal gene transfer, and gene loss, provided a powerful mechanistic framework for this reconciliation process [34] [33].

The Amalgamated Likelihood Estimation (ALE) algorithm is a sophisticated probabilistic method for phylogenetic reconciliation [35] [36]. Unlike parsimony-based methods that seek a scenario with the minimum number of events, ALE uses a probabilistic model to account for uncertainty in gene tree topologies. Its main innovation is that it does not reconcile a single gene tree to the species tree. Instead, it uses a distribution of gene trees (e.g., from bootstrap replicates or a Bayesian posterior sample) to reconcile the different splits found in these trees, weighting them by their frequency [37]. This allows ALE to account for the uncertainty inherent in gene tree reconstruction, leading to more robust inferences of evolutionary events [37]. ALE has become an indispensable tool in evolutionary genomics, with key applications including rooting species and gene trees, inferring ancestral genomes, detecting ancient lateral gene transfers, and understanding the dynamics of genome evolution [37]. Its utility is particularly pronounced in the field of LUCA (Last Universal Common Ancestor) genome reconstruction, where it helps pinpoint the origin of gene families amidst the confounding effects of billions of years of horizontal gene transfer, duplication, and loss [34] [35] [7].

Core Methodology of the ALE Algorithm

Input Data Requirements and Preparation

The execution of the ALE algorithm requires careful preparation of specific input data, which forms the foundation for all subsequent analyses.

Table: Input Data Requirements for ALE

| Input Component | Description | Data Source & Format | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Species Tree | A bifurcating tree representing the evolutionary relationships of the species under study. | Newick format (.nwk). Can be dated (branch lengths proportional to time) or undated [37]. | A dated tree ensures time-consistent transfers in ALE dated, but is difficult to obtain. ALE undated relaxes this requirement [37]. |