Mastering Time: A Comprehensive Guide to Optimizing RNA-seq Sampling Timepoints for Robust Transcriptomic Insights

This article provides a strategic framework for researchers and drug development professionals to design and optimize RNA-seq sampling timepoints.

Mastering Time: A Comprehensive Guide to Optimizing RNA-seq Sampling Timepoints for Robust Transcriptomic Insights

Abstract

This article provides a strategic framework for researchers and drug development professionals to design and optimize RNA-seq sampling timepoints. We cover the foundational principles of temporal gene expression dynamics, explore methodological approaches for time-course experimental design, address common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and compare validation strategies. The goal is to empower scientists to capture biologically relevant transcriptional changes efficiently, maximizing statistical power and research ROI while minimizing cost and technical variability.

Why Time Matters: The Critical Role of Sampling Timepoints in Unlocking Dynamic Transcriptomes

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My RNA-seq data shows high variability between biological replicates sampled at the same "circadian" time. What could be the cause?

- A: This is a common issue in temporal studies. The primary culprit is often inadequate entrainment or synchronization of the biological clocks in your experimental model (e.g., cells, animals) prior to sampling. Ensure a strict and consistent light/dark, feeding, or serum-shock protocol for at least 3-5 cycles before the experiment. Also, verify that environmental conditions (temperature, humidity) are controlled. Technical variability from sample collection speed and RNA stabilization is critical; ensure all samples are processed within an identical and minimal window.

Q2: How do I determine if an observed expression pattern is a true oscillation versus random noise or a transient response?

- A: True biological oscillations (e.g., circadian) should persist for at least two complete cycles under constant conditions. We recommend:

- Extended Time Series: Sample at 2-4 hour intervals for a minimum of 48-72 hours.

- Statistical Testing: Use algorithms like JTK_Cycle, RAIN, or MetaCycle which are designed to detect periodic signals in time-series data.

- Replication: Include at least 3-4 biological replicates per timepoint to robustly estimate variance.

- Compare Models: Statistically compare fit to a cyclic model vs. a transient (e.g., impulse) model.

- A: True biological oscillations (e.g., circadian) should persist for at least two complete cycles under constant conditions. We recommend:

Q3: How many timepoints are sufficient for capturing a transient transcriptional wave, such as in a drug response experiment?

- A: The optimal design depends on the expected response kinetics. For a typical pharmacodynamic response, a pilot experiment is essential. Use dense early sampling (e.g., 15, 30, 60, 90, 120 minutes) to capture the rapid induction phase, followed by less frequent sampling (4, 8, 12, 24 hours) to capture decay and secondary responses. The table below summarizes recommended strategies based on response type.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Failed Detection of Known Circadian Transcripts.

- Step 1: Verify Entrainment. Check expression of core clock genes (e.g., Bmal1, Per2) in your samples via qPCR as a positive control.

- Step 2: Check Sampling Resolution. If sampling intervals are too wide (e.g., >6 hours), you may miss peak and trough phases. Refer to the protocol for pilot study resolution.

- Step 3: Re-assess Bioinformatics. Ensure your RNA-seq analysis pipeline uses appropriate normalization (e.g., TMM) for time-series data and applies the correct statistical tests for periodicity.

Issue: Inconclusive Results from a Drug Time-Course Experiment.

- Step 1: Incorporate a Vehicle Time-Course. You must control for any temporal effects of the administration method itself (e.g., saline injection, DMSO).

- Step 2: Include a "Time Zero" Baseline. Collect samples immediately before treatment (T0) to distinguish baseline expression from early responses.

- Step 3: Optimize Dose. The observed kinetic profile may be dose-dependent. A suboptimal dose may yield a weak, noisy signal.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Recommended Sampling Strategies for Different Temporal Biological Processes

| Process Type | Example | Recommended Minimum Time Coverage | Suggested Sampling Interval (Pilot) | Key Statistical Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Circadian Oscillation | Core Clock Genes | 48 hours under constant conditions | 4 hours | JTK_Cycle, RAIN |

| Ultradian Rhythm | Hormone Pulses, p53 Signaling | 12-24 hours | 1-2 hours | Spectral Analysis, Wavelet |

| Transient Wave | LPS-induced Inflammation, Drug Response | Capture onset, peak, decline | Dense early (15-30 min), then 1-4 hours | Impulse Model Fitting (e.g., ImpulseDE2) |

| Developmental Transition | Cell Differentiation | Full transition period (days) | 6-12 hours | Clustering (k-means), Pseudotime Analysis |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Optimizing Sampling Timepoints for Circadian RNA-seq in Mouse Liver.

- Entrainment: House mice in a controlled light chamber for at least two weeks on a 12h:12h Light:Dark (LD) cycle.

- Synchronization: On the experimental day, switch animals to constant darkness (DD) to "free-run."

- Sampling: Beginning at the subjective time of usual lights-on (Circadian Time 0, CT0), euthanize animals and collect liver tissue every 4 hours for 48 hours (12 timepoints). Perform sampling under dim red light for DD timepoints.

- Replication: Use a minimum of 4 animals per timepoint. Randomize the order of sacrifice across timepoints to avoid batch effects.

- Processing: Snap-freeze tissue immediately in liquid nitrogen. Homogenize and stabilize RNA using a chaotropic buffer (e.g., TRIzol) within 5 minutes of dissection.

Protocol: Dense Time-Course for Acute Drug Response in Cell Culture.

- Synchronization: Serum-starve cells for 24 hours to synchronize them in G0/G1 phase.

- Treatment & Sampling: Add drug or vehicle control to media. Harvest cell pellets in triplicate at the following timepoints post-treatment: 0 (pre-dose), 15, 30, 60, 90, 120 minutes, and 4, 8, 12, 24 hours.

- Rapid Stabilization: Use a cell lysis buffer that immediately inactivates RNases (e.g., Buffer RLT from Qiagen). Plates can be processed directly or stored at -80°C.

- RNA Extraction: Use a high-throughput, spin-column-based method to ensure consistency across many samples.

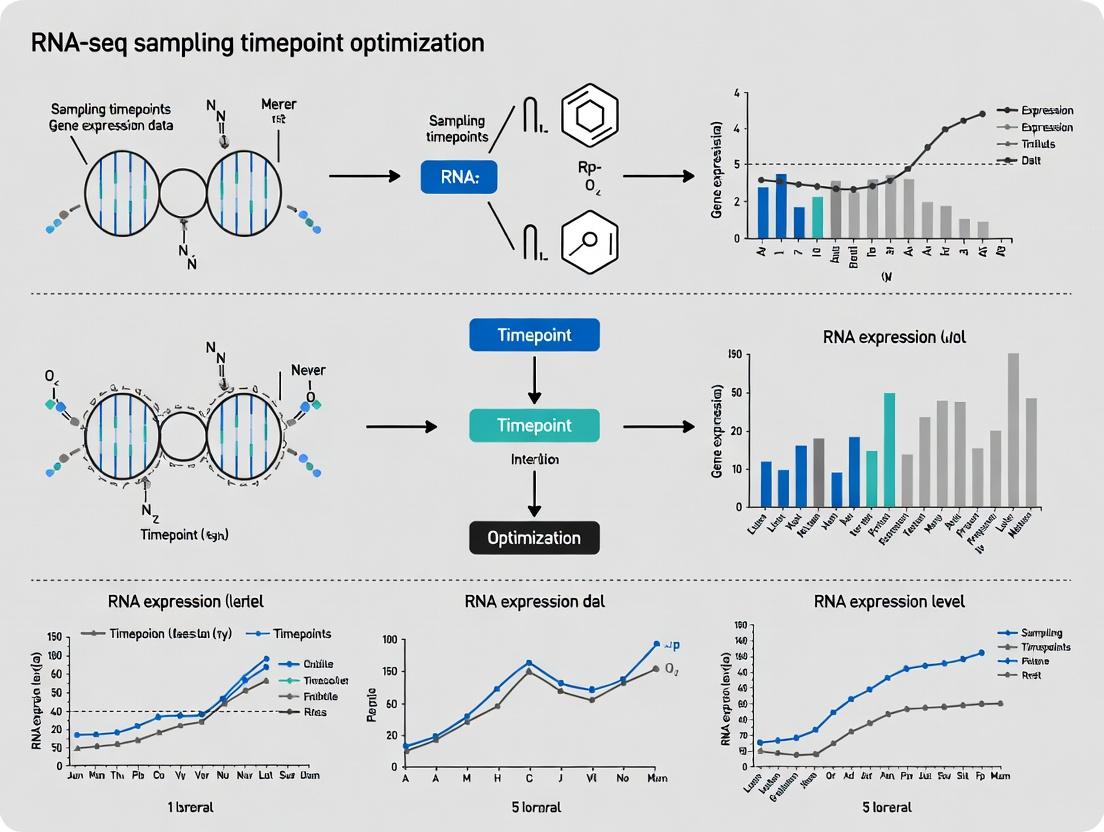

Mandatory Visualizations

Title: Workflow for Timepoint Optimization in RNA-seq Studies

Title: Core Mammalian Circadian Clock Feedback Loop

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Temporal Studies |

|---|---|

| RNase Inhibitors (e.g., Recombinant RNasin) | Critical for preserving RNA integrity during rapid sample collection, especially for dense time-courses. |

| Rapid Lysis Buffers (e.g., TRIzol, Qiazol) | Provide immediate stabilization of the transcriptome at the moment of harvest, "freezing" the expression state. |

| Automated Nucleic Acid Purification Systems | Ensure high-throughput, consistent RNA extraction across dozens of timepoint samples, minimizing batch effects. |

| ERCC RNA Spike-In Mixes | Exogenous controls added at lysis to monitor technical variability and normalize for sample-to-sample differences in RNA recovery. |

| Reverse Transcriptase with High Efficiency | Essential for capturing low-abundance or rapidly turning over transcripts in qPCR validation of RNA-seq results. |

| Serum for Synchronization | High-concentration serum is used for serum-shock synchronization of circadian clocks in cultured cells. |

| Luciferase Reporters (for clock genes) | Allows real-time, longitudinal monitoring of promoter activity in live cells, guiding optimal sampling windows for endpoint assays. |

Technical Support Center: RNA-seq Timepoint Optimization

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: Our RNA-seq data shows high variability between replicates at a single timepoint. Could this be due to circadian rhythm effects, and how can we troubleshoot this? A: Yes, unsynchronized circadian rhythms in cell cultures or animal models are a common source of high inter-replicate variability. To troubleshoot:

- Synchronize Cultures: Treat cells with dexamethasone (100 nM for 1-2 hours) or perform serum shock (50% serum for 2 hours) to synchronize circadian clocks before your experiment.

- Control Lighting: For in vivo studies, ensure a strict 12-hour light/12-hour dark cycle in animal facilities for at least one week prior to sampling.

- Pilot Time-Course: Run a pilot 24-48 hour time-course experiment with sampling every 4-6 hours. Use core clock genes (e.g., PER1/2, BMAL1, REV-ERBα) as biomarkers. High-amplitude oscillation confirms circadian influence.

- Statistical Analysis: Apply circular or harmonic regression models to your pilot data to identify peak and trough times for your pathway of interest, then sample at those defined phases.

Q2: We missed a key transient expression peak of a target gene. What is the best method to determine optimal sampling intervals for capturing transient dynamics? A: Missing transient peaks is a direct result of sampling intervals longer than the event's half-life. Follow this protocol:

- Literature & Database Mining: Consult databases like GEO (GSE34018, GSE54652) for similar systems to estimate response kinetics. Inflammatory responses can have peaks within 30-60 minutes; some transcription factors peak within 2-4 hours.

- Dense Preliminary Sampling: After perturbation, perform an ultra-dense time-course (e.g., every 15-30 min for 4 hours, then every hour for 12 hours). Use cheaper, targeted assays (qPCR, NanoString) for this phase.

- Mathematical Modeling: Fit the dense qPCR data to kinetic models (e.g., impulse model, spline fitting) to estimate the true peak time (tmax) and duration.

- Validate with RNA-seq: Design your final RNA-seq experiment with timepoints centered on the predicted tmax from the model, plus flanking timepoints.

Q3: How do we balance the number of timepoints with budget constraints without sacrificing critical information? A: Use an optimal experimental design approach. The table below compares strategies:

Table 1: Sampling Strategy Trade-offs

| Strategy | Description | Pros | Cons | Recommended Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uniform Dense | Many equally spaced points (e.g., 12 timepoints). | Captures unknown dynamics. | Very expensive; redundant data. | Early exploratory phases with no prior knowledge. |

| Optimal Timepoint | Fewer, strategically chosen points. | Cost-effective; high information yield. | Requires pilot data & modeling. | Most confirmatory studies. |

| Hybrid | Dense sampling early/post-perturbation, sparse later. | Captures fast transients efficiently. | More complex analysis. | Studying acute responses (e.g., drug pulse, injury). |

Protocol for Optimal Timepoint Selection:

- From your dense pilot data, select candidate timepoints (e.g., 6-8).

- Use the

D-optimality orA-optimality criterion from statistical design theory to rank combinations of 3-4 timepoints. - Choose the set that maximizes the expected information gain for your model parameters (e.g., peak time, amplitude, decay rate).

- Validate the chosen design with a computational leave-one-out simulation before proceeding.

Q4: In a drug treatment study, when is the best time to sample for mechanism of action (MoA) vs. efficacy endpoints? A: These require fundamentally different timing, as shown in the table below.

Table 2: Sampling Windows for Drug Study Objectives

| Study Objective | Key Biological Processes | Typical Optimal Sampling Window | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanism of Action | Direct target engagement, primary transcriptional response, pathway modulation. | Early (1-8 hours). | Avoid secondary/adaptive responses. Use acute dosing. |

| Efficacy & Phenotype | Downstream phenotypic changes, cell fate decisions, therapeutic effect. | Late (24 hours - 7 days+). | Align with morphological/functional readouts. |

| Toxicity & Off-Target | Stress response, apoptosis, unexpected pathway activation. | Multiple (e.g., 6h, 24h, 72h). | Capture both immediate stress and chronic dysfunction. |

Protocol for MoA-Focused Time-Course:

- Administer drug at a concentration near IC50/EC50.

- Sample at T=0 (pre-dose), 30min, 1h, 2h, 4h, 8h, 12h, and 24h.

- Analyze early timepoints (1-4h) for primary response genes (often have simple regulatory regions). Use tools like DESeq2 with

likelihood ratio testacross the full time-course. - Cluster expression profiles to distinguish primary (monotonic) from secondary (oscillatory/delayed) responses.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Time-Course RNA-seq Studies

| Item | Function in Timepoint Optimization | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Stabilization Reagent | Instantaneously halts gene expression at exact moment of sampling, critical for short time intervals. | RNAlater, TRIzol, QIAzol. For tissues, direct immersion is key. |

| Circadian Synchronizers | Synchronizes cellular clocks in culture to reduce replicate variability. | Dexamethasone (100 nM), Forskolin (10 µM), Serum Shock (50% FBS). |

| Inhibitors of Transcription/Translation | Used in pulse-chase experiments to measure RNA decay rates (t1/2). | Actinomycin D (5 µg/mL), Triptolide (1 µM). |

| Metabolic Labeling Nucleotides | Enables measurement of nascent RNA synthesis for ultra-fine kinetic resolution. | 4-Thiouridine (4sU, 100-500 µM), EU (5-ethynyl uridine). |

| Ribo-depletion Kits | Essential for capturing non-coding and nascent RNA species often missed by poly-A selection. | Illumina Ribo-Zero Plus, QIAseq FastSelect. |

| Spike-in RNA Controls | Allows absolute quantification and corrects for technical variation between samples, crucial for comparing across timepoints. | ERCC ExFold RNA Spike-In Mix, SIRV Spike-in Kit. |

Visualization: Experimental Workflow & Pathway Impact

Diagram 1: Optimal RNA-seq Time-Course Design Workflow

Diagram 2: Consequences of Poor Timing on Pathway Interpretation

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Q1: My RNA-seq time course shows high biological variability between replicates at certain timepoints, obscuring the detection of differentially expressed genes. What are the primary causes and solutions? A: High variability often stems from imperfect synchronization of biological processes or inconsistent sample handling. Implement rigorous synchronization protocols (e.g., serum starvation followed by precise stimulation for cell lines) and increase biological replicates (n=5-6) for noisy timepoints. Utilize spike-in controls (e.g., ERCC RNA Spike-In Mix) to distinguish technical from biological variation. Consider a pilot study to identify and exclude inherently high-variance timepoints from the main experiment.

Q2: How do I determine the optimal number and spacing of timepoints for my RNA-seq experiment on a novel process? A: The optimal design depends on the kinetic properties of your system. Begin with a broad, low-resolution pilot study (e.g., 0, 2, 6, 12, 24, 48 hours) to identify periods of dynamic change. Follow with a high-resolution series around those periods. Use autocorrelation analysis on pilot data to estimate the minimum time interval needed to capture independent samples.

Q3: I am seeing batch effects correlated with the day of sample collection in my multi-day time course experiment. How can I mitigate this? A: Batch effects are a major confounder in temporal studies. Key strategies include:

- Blocking Design: Process all samples for a single biological replicate across all timepoints in one batch.

- Randomization: If full blocking is impossible, randomize the order of timepoint processing across batches.

- Statistical Correction: Use methods like ComBat-seq or RUVseq in your differential expression pipeline, using control genes or spike-ins.

Q4: How long can I store RNA samples at -80°C before library prep without significant degradation impacting timepoint comparisons? A: While RNA is stable at -80°C for years, for consistent time course data, minimize storage time variance. Prepare libraries for all samples in a randomized order within a short, defined period. Use RNA Integrity Number (RIN) > 8.5 as a strict quality criterion for all samples before proceeding.

Table 1: Recommended Replicates and Sequencing Depth for Time Course RNA-seq

| Experimental Goal | Minimum Biological Replicates per Timepoint | Recommended Sequencing Depth (per sample) | Key Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pilot / Exploratory Study | 3 | 20-30 million reads | Identify major expression trends and highly dynamic periods. |

| Definitive Differential Expression | 5-6 | 30-40 million reads | Achieve statistical power to detect subtle, transient expression changes. |

| Splice Isoform Analysis | 4-5 | 40-60 million reads | Deeper sequencing required for resolving isoform-level dynamics. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Cell Synchronization for a Serum-Stimulation Time Course

- Culture: Grow adherent cells to 60-70% confluence in complete growth medium.

- Starvation: Rinse cells twice with PBS and replace medium with serum-free medium for 48 hours to induce quiescence (G0 phase).

- Stimulation: Pre-warm complete growth medium (containing serum/growth factors). Precisely at time T=0, replace the serum-free medium with the complete medium. Record the exact time for each flask/plate.

- Harvesting: At each predetermined timepoint, rapidly aspirate medium, rinse with cold PBS, and lyse cells directly in the plate using a guanidinium-thiocyanate-based lysis buffer (e.g., QIAzol). Store lysates at -80°C.

- RNA Extraction: Isolate total RNA using a silica-membrane column method (e.g., RNeasy) with on-column DNase I digestion. Assess purity (A260/280) and integrity (RIN) before library preparation.

Protocol 2: RNA-seq Library Preparation with External RNA Controls (ERCC Spike-Ins)

- RNA Quantification: Accurately quantify total RNA using a fluorometric method (e.g., Qubit RNA HS Assay).

- Spike-in Addition: Dilute the ERCC Spike-In Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat. 4456740) 1:100 in nuclease-free water. Add 2 µL of the diluted spike-in to 500 ng of each total RNA sample. This step is critical for normalization across timepoints with vastly different transcriptional activity.

- Library Construction: Use a stranded, poly-A selection library prep kit (e.g., Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep). Follow manufacturer instructions for cDNA synthesis, adapter ligation, and PCR amplification.

- QC and Pooling: Assess final library size distribution (e.g., TapeStation) and quantify (e.g., qPCR). Pool libraries equimolarly for multiplexed sequencing.

Visualizations

Time Course RNA-seq Experimental Design Workflow

Batch Effect Mitigation via Experimental Design

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Time Course RNA-seq | Example Product/Catalog |

|---|---|---|

| ERCC RNA Spike-In Mix | A set of synthetic RNA standards at known concentrations added to each sample pre-library prep. Enables technical normalization and detection of batch effects across samples and timepoints. | Thermo Fisher, 4456740 |

| RiboZero/RiboMinus Kits | For ribosomal RNA depletion. Essential for non-polyA targets (e.g., bacterial RNA, degraded FFPE samples) or when studying non-coding RNA dynamics across time. | Illumina, 20040526 |

| Dual-Index UDIs (Unique Dual Indexes) | Unique nucleotide combinations for each sample library. Critical for multiplexing many timepoint samples, preventing index hopping cross-talk, and ensuring data integrity. | Illumina, 20040527 |

| RNase Inhibitor | Protects RNA integrity during cell lysis and RNA handling. Vital for early timepoints where rapid transcriptional changes may be masked by degradation. | Takara, 2313A |

| Cell Cycle Synchronization Agents | Chemical tools (e.g., Thymidine, Nocodazole) to arrest populations at specific cell cycle phases, reducing heterogeneity at the T0 timepoint for cell division studies. | Sigma, T9250 (Thymidine) |

| Time-Series Analysis Software | Computational tools designed for longitudinal data to model expression trends, clusters, and identify significant temporal patterns. | maSigPro (R/Bioconductor), HMMSeq |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: Our pilot RNA-seq time-course shows no differential expression. Did we choose the wrong timepoints? A: This is common. A null result is informative. First, consult literature to verify your initial timepoints cover the known response window. Use your pilot data to calculate statistical power. If power is low (<0.8), you likely need more biological replicates or to adjust timepoints to regions of higher expected variability. Re-analyze pilot data focusing on variance stabilization to identify temporal regions of high biological noise, which may indicate active regulation.

Q2: How do we use published RNA-seq data to justify our selected timepoints in a grant proposal? A: Create a synthesis table from literature. Extract key timepoints where pathways of interest show activation. Use this to define your sampling "envelope." Your pilot study should then test the extremes and midpoint of this envelope. In the proposal, present the literature-derived table alongside your pilot study design diagram to show an iterative, knowledge-driven approach.

Q3: In a drug treatment experiment, how many preliminary timepoints are needed before the main study? A: The minimum is three: a baseline (T0), an early timepoint (e.g., 1-2 hrs post-treatment for acute signaling), and a later timepoint (e.g., 24 hrs for transcriptional outputs). This helps capture the response trajectory. The table below summarizes a typical framework:

Table 1: Minimum Pilot Timepoint Framework for Drug Treatment RNA-seq

| Timepoint ID | Post-Treatment | Biological Rationale | Key Parameter Tested |

|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | 0 hours | Baseline expression & cohort uniformity | Inter-animal variance at baseline |

| T1 | 1-2 hours | Early transcriptional shock & immediate early genes | Signal-to-noise ratio of response |

| T2 | 24 hours | Stabilized transcriptional reprogramming | Effect size for pathway analysis |

Q4: How can we optimize cost when pilot studies are expensive? A: Use bulk RNA-seq with a lower sequencing depth (10-15 million reads per sample) for the pilot. Focus on a subset of key marker genes identified from literature to validate response via qPCR across many timepoints. Then, select only the most informative 3-4 timepoints for deeper, full-transcriptome pilot sequencing.

Q5: Our pilot data contradicts established literature on the timing of a pathway. How should we proceed? A: Do not discard the pilot. Investigate discordance. Check batch effects, drug activity, or model differences. Design your main experiment to explicitly test both the literature-derived and your pilot-derived timepoints. This turns a problem into a novel research question.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Power Analysis for Timepoint Selection Using Pilot Data

- Input: Pilot RNA-seq count data for 2-3 timepoints with n=2-3 replicates.

- Software: Use

PROPER(R/Bioconductor) orScottyweb tool. - Method: a. From pilot data, estimate the mean and dispersion for each gene. b. Define a minimum fold-change of interest (e.g., 1.5 or 2.0). c. Simulate power for varying replicate numbers (n=3, 6, 10) at your pilot timepoints. d. The timepoint showing the highest achievable power with feasible replicates is prioritized.

- Output: A power simulation table to guide replicate number for the main study.

Protocol 2: Literature Mining for Temporal Pathway Activation

- Resource: PubMed, GEO DataSets, and pathway databases (KEGG, Reactome).

- Search String:

"[Your Pathway] AND RNA-seq AND (time-course OR kinetics) AND [Your Model System]". - Method: a. Extract all reported significant timepoints for key genes in your pathway of interest. b. Note the study model, stimulus, and sequencing platform. c. Plot these timepoints on a unified timeline to identify consensus peaks of activity.

- Output: A consensus timeline diagram and a summarized table of literature-derived critical timepoints.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for RNA-seq Time-Course Experiments

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| RNAlater Stabilization Solution | Preserves RNA integrity at the moment of sampling, critical for accurate temporal snapshots. |

| Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System | Validates promoter activity of key genes from literature before committing to full RNA-seq. |

| ERCC RNA Spike-In Mix | Added to lysates to monitor technical variation and normalize across timepoints. |

| Poly-A RNA Selection Beads | Ensures consistent mRNA enrichment across samples, reducing 3' bias in time-series data. |

| Sensitive Stranded cDNA Library Prep Kit | Captures low-abundance transient transcripts that are hallmarks of early timepoints. |

| Cell Cycle Synchronization Agents | (e.g., Aphidicolin, Nocodazole) Reduces confounding variance in cycling cell models. |

Visualizations

Title: Workflow for Informed Timepoint Selection

Title: Generic Drug Response Transcriptional Cascade

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting RNA-seq Time-Course Experiments

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: We have a limited budget. How do I choose between more biological replicates, more timepoints, or deeper sequencing depth? A: This is the core trade-off. The optimal choice depends on your biological question. Use pilot data and power analysis to inform your decision.

- For detecting transient expression peaks: Prioritize more timepoints with moderate replicates (n=2-3) over deep sequencing. Temporal resolution is key.

- For robust differential expression at specific times: Prioritize biological replicates (n=4-6) at fewer, critically chosen timepoints.

- For isoform-level or low-abundance transcript analysis: Sequencing depth is more critical. Compromise on the number of timepoints or replicates.

Table 1: Resource Allocation Trade-off Scenarios

| Primary Goal | Recommended Priority Order | Key Compromise | Suggested Minimum (Pilot) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Define expression dynamics/trajectories | 1. Timepoints, 2. Replicates, 3. Depth | Reduce replicates to n=2-3 per timepoint | 8-12 timepoints, n=2, 20M reads/sample |

| Compare specific treatment vs control timepoints | 1. Replicates, 2. Depth, 3. Timepoints | Focus on fewer, biologically justified timepoints | 3-4 key timepoints, n=4-6, 30M reads/sample |

| Discover novel isoforms/allele-specific expression | 1. Depth, 2. Replicates, 3. Timepoints | Use wider intervals between fewer timepoints | 4-6 timepoints, n=3, 50M+ reads/sample |

Q2: Our pilot time-course revealed unexpected activity at an un-sampled time. How can we iteratively optimize our design? A: Implement an adaptive two-phase design.

- Phase 1 (Exploratory): Use a wide-interval, low-replicate design (e.g., 0, 6, 24, 48h, n=2).

- Phase 2 (Targeted): Analyze Phase 1 data to identify regions of high dynamic change. Design a denser sampling scheme around these intervals (e.g., 12, 18, 21, 27h, n=4).

Q3: How do we handle batch effects when samples are collected and processed over multiple days? A: Time-course experiments are highly susceptible to batch effects. Strict randomization and blocking are essential.

- Protocol: For a 10-timepoint experiment, do not process all samples from one day together. Instead, process samples from all timepoints in each batch, balanced across experimental groups. Include inter-batch control samples (e.g., a reference RNA sample) in every library prep batch for normalization.

Q4: What statistical methods are best for identifying differentially expressed genes (DEGs) across time? A: Use specialized time-series aware tools. Do not perform independent pairwise comparisons at each timepoint.

- Recommended Workflow:

- Filtering: Keep genes with counts > 10 in at least n samples (n = number of replicates).

- Normalization: Use TMM (edgeR) or median-of-ratios (DESeq2) method.

- Analysis: Apply a likelihood ratio test (LRT) in DESeq2 to test for any expression change over time, or use maSigPro (for complex designs) or splineTC to fit regression models and identify significant temporal profiles.

Experimental Protocol: Key Time-Course Sampling & RNA Stabilization Objective: To preserve accurate transcriptional snapshots at precise times. Materials: See "Scientist's Toolkit" below. Steps:

- Synchronization: Apply treatment to all cultures/cells/animals within a minimal window (<1 hr). Record this as T=0.

- Sampling: At each predetermined timepoint, rapidly harvest material. For in vivo studies, perfuse animals if necessary to remove blood RNA background.

- Immediate Stabilization: Immediately submerge tissue/cells in ≥10 volumes of RNA stabilization reagent (e.g., RNAlater) or flash-freeze in liquid nitrogen. Do not delay.

- Storage: Store stabilized samples at -80°C until all timepoints are collected.

- Batch Processing: Isolate RNA from all timepoint samples in a single, randomized batch using a column-based kit with DNase I treatment.

- Quality Control: Assess RNA Integrity Number (RIN) for all samples using a Bioanalyzer/TapeStation. Proceed only if RIN > 8.0 (cultured cells) or > 7.0 (complex tissues).

Visualizations

Title: Adaptive Two-Phase Time-Course Design Workflow

Title: The Fundamental Trade-off in Time-Course Experimental Design

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in RNA-seq Time-Course |

|---|---|

| RNAlater Stabilization Reagent | Rapidly penetrates tissues to stabilize and protect cellular RNA at the moment of sampling, preventing degradation. Critical for field or lab collection. |

| DNase I (RNase-free) | Removes genomic DNA contamination during RNA purification, essential for accurate RNA-seq library quantification and sequencing. |

| RNA Integrity Number (RIN) Standard Chips | For use with Bioanalyzer/TapeStation to quantitatively assess RNA degradation. A QC gatekeeper; low RIN samples introduce major bias. |

| UMI (Unique Molecular Identifier) Adapter Kits | Labels each original mRNA molecule with a unique barcode during library prep to correct for PCR amplification bias and duplicate reads. |

| ERCC (External RNA Controls Consortium) Spike-in Mix | A set of synthetic RNA controls at known concentrations added to samples to monitor technical variance, normalization accuracy, and sensitivity. |

| Poly(A) Magnetic Beads | For mRNA enrichment from total RNA by selecting polyadenylated tails. Standard for most eukaryotic mRNA-seq protocols. |

| Ribo-depletion Kits | Selectively removes ribosomal RNA (rRNA) from total RNA, enabling sequencing of non-polyadenylated transcripts (e.g., lncRNAs, bacterial RNA). |

| Dual-Index UMI Adapter Kits | Enables multiplexing of many samples across multiple sequencing lanes while incorporating UMIs. Maximizes throughput and data quality. |

Designing the Perfect Time-Course: A Step-by-Step Methodological Blueprint for RNA-seq Sampling

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs for RNA-seq Timepoint Optimization Experiments

Q1: Our pilot RNA-seq time course shows high variability between biological replicates at certain timepoints, obscuring the expression dynamics. How can we troubleshoot this? A: High variability often indicates either inadequate replication or sampling at transition points between biological phases. First, ensure a minimum of n=4 biological replicates per timepoint for dynamic processes. If variability is clustered at specific times, this may signal a "critical phase" transition. Consider performing a high-resolution "dense sampling" pilot (e.g., every 30 minutes over a suspected 6-hour window) to pinpoint the exact transition timing before committing to a full-scale, sparse-sampled experiment. Check sample collection synchronization; even minor delays in processing can cause large expression differences during rapid transitions.

Q2: How do we decide between a dense (many timepoints, low replication) or sparse (fewer timepoints, high replication) sampling strategy with a limited budget? A: The choice hinges on prior knowledge of the system's dynamics. Use the following decision table, synthesized from recent studies:

| Strategy | Best For | Typical Replication (n) | Key Risk | Recommended Pilot Experiment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dense Sampling (e.g., 12+ timepoints) | Discovering unknown critical phases, systems with oscillatory behavior, or very rapid transitions. | Lower (n=2-3) due to cost per sample. | May miss biological variability and yield statistically weak results at any single point. | RNA-seq on a single, pooled biological sample across many times to map trends. |

| Sparse Sampling (e.g., 4-6 timepoints) | Validating hypothesized critical phases, slower biological processes, or when high statistical power is needed per timepoint. | Higher (n=4-6) to ensure robustness. | May completely miss a brief but crucial transcriptional event between sampled points. | Literature meta-analysis & qPCR validation on 3-5 candidate genes across a dense temporal grid. |

Q3: What defines a "Critical Phase" in a transcriptional time course, and how can we identify it computationally from our data? A: A Critical Phase is a limited time window during which a system undergoes a fundamental shift in regulatory state, characterized by a high rate of change in gene expression. To identify it, perform the following analytical protocol post-RNA-seq:

- Alignment & Quantification: Use STAR aligner and featureCounts on GRCh38/hg38 or latest genome build.

- Differential Expression Trajectory: Use a tool like

DESeq2orlimma-voomto model expression over time. - Identify Inflection Points: Apply the

ImpulseDE2orGPfatesR package. These model expression trajectories and assign genes to specific temporal response patterns (e.g., transient peak, sustained shift). - Critical Phase Definition: The time window where the highest number of genes show their peak rate of change (derivative of fitted curve) or where distinct gene clusters transition between patterns is your candidate Critical Phase.

Q4: Our experiment failed to capture the expected expression peak of a known marker gene. What went wrong? A: This is a classic symptom of temporal aliasing—sampling too infrequently to capture a rapid event. Implement this protocol to rectify:

- Step 1: Perform a literature and database search (e.g., GEO) for your biological model and marker to hypothesize the peak's likely timing.

- Step 2: Design a targeted qPCR validation experiment with dense sampling around the hypothesized peak.

- Protocol: Collect samples every 2-4 hours over a 48-hour window centered on your best guess. Use TRIzol reagent for RNA isolation, followed by DNase treatment. Perform reverse transcription with a High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit. Run qPCR in triplicate technical replicates using SYBR Green assays for your target and 2-3 validated housekeeping genes.

- Step 3: Use the qPCR results to pinpoint the exact peak timing with high confidence, then reschedule your broader RNA-seq experiment with a key timepoint directly on this peak.

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

| Item | Function in Timepoint Experiments |

|---|---|

| RNAlater Stabilization Solution | Preserves RNA integrity instantly upon sample collection, critical for ensuring timepoints reflect in vivo state and not artifact of processing delay. |

| TRIzol/Chloroform | Reliable, broad-spectrum reagent for simultaneous RNA isolation from various sample types (cells, tissues) during high-throughput time course collections. |

| DNase I (RNase-free) | Essential for removing genomic DNA contamination from RNA preparations prior to library construction, preventing spurious sequencing reads. |

| Poly(A) Magnetic Beads | For mRNA enrichment in standard library prep. For dense time courses, consider ribodepletion kits to capture non-coding and degraded transcripts. |

| UMI (Unique Molecular Identifier) Adapter Kits | Allows accurate correction for PCR duplication bias, which is crucial for quantifying expression changes accurately across timepoints. |

| Spike-in RNA Controls (e.g., ERCC) | Added at RNA extraction to normalize for technical variation (e.g., yield, efficiency) across samples, improving comparison between timepoints. |

| High-Fidelity Reverse Transcriptase | Critical for accurate and full-length cDNA synthesis, especially for long transcripts that may show isoform switching over time. |

Experimental Workflow & Pathway Diagrams

Title: RNA-seq Timepoint Optimization Workflow

Title: Critical Phase Properties & Sampling Impact

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: When using powsimR for RNA-seq power analysis in my timecourse experiment, I encounter the error: "Error in checkBPPARAM(BPPARAM) : object 'BPPARAM' not found." What does this mean and how do I resolve it?

A: This error typically indicates a missing BiocParallel parameter object required for parallel computation. First, ensure the BiocParallel package is installed and loaded (library(BiocParallel)). Then, explicitly define the BPPARAM argument in your powsimR function call. For a local machine, use BPPARAM = MulticoreParam(workers = [number_of_cores]) or SnowParam(). If parallel processing is not desired, you can set BPPARAM = SerialParam().

Q2: My splatter simulation of a multi-timepoint RNA-seq experiment produces gene expression distributions that are unrealistic. The simulated counts are too uniform across conditions. What parameters should I adjust?

A: This often results from inadequate differential expression (DE) parameter settings. Focus on the de.facLoc and de.facScale parameters in the splatSimulate() function, which control the location and scale of the DE factor log-normal distribution. Increase de.facScale to introduce more variability in the strength of DE between genes. Also, review the group.prob (proportion of cells/samples in each timepoint) and de.prob (probability of a gene being differentially expressed) parameters to ensure they match your experimental design.

Q3: How do I accurately model dropout (zero-inflation) in my simulations for a sparse single-cell RNA-seq timecourse study using these tools?

A: Both tools offer dropout simulation. In splatter, use the dropout.type = "experiment" or "batch" parameter and set dropout.shape = -1 and dropout.mid to define the logistic function for the dropout probability. In powsimR, zero-inflation can be incorporated by specifying the sim.seq method (e.g., ZINB) and providing estimated zero-inflation parameters (estZINB) from your pilot or reference data. Always validate simulated dropout rates against a real dataset from a similar system.

Q4: For power analysis of a longitudinal RNA-seq study with powsimR, how should I structure the experimental design matrix to compare specific timepoints?

A: You must define the Design matrix carefully. Create a model matrix where rows are samples and columns represent timepoints or conditions. For example, for three timepoints (T0, T1, T2), you might have columns for T1 and T2, with T0 as the baseline. Specify this design in the powsim function's design argument and define the precise comparisons in the contrast argument (e.g., contrast = c(0,1,0) to extract the coefficient for T1 vs baseline). Ensure the number of simulated samples per group (nsim) matches your design.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Simulation Tools for RNA-seq Pre-Design

| Feature | splatter (Bioconductor) |

powsimR (CRAN/Bioconductor) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Purpose | Flexible simulation of scRNA-seq & bulk RNA-seq data. | Explicit power analysis & sample size estimation for RNA-seq. |

| Key Strength | Models complex biological networks (e.g., paths, groups). Direct integration with SingleCellExperiment. | Extensive power calculations across multiple DE tools (DESeq2, edgeR, limma). |

| DE Modeling | Log-normal distribution for DE factors. | Based on empirical estimates or negative binomial. |

| Dropout/Zero-inflation | Explicit logistic model for dropout. | Models via negative binomial or zero-inflated negative binomial. |

| Best For in Timepoint Optimization | Exploring the impact of trajectory shapes and cellular heterogeneity on discovery. | Determining the required sample size per timepoint to detect a fold-change of interest. |

Table 2: Recommended Pilot Study Parameters for Power Analysis

| Parameter | Recommended Input Source | Notes for Timepoint Experiments |

|---|---|---|

Mean Expression (mu) & Dispersion (fit) |

Pilot data, public datasets (e.g., GEO). | Use data from the same tissue/system. Pool across conditions to get robust estimates. |

| Effect Size (Fold Change) | Literature or minimal biologically relevant effect. | For timecourses, consider the expected fold change between critical timepoints (e.g., peak response vs baseline). |

Sample Size per Group (n) |

Varied during simulation (e.g., 3, 5, 10). | Include potential for paired/sample-matched designs in longitudinal studies. |

| Dropout Rate | Estimated from pilot or similar published scRNA-seq data. | May vary across timepoints if cell states change significantly. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Power Analysis for RNA-seq Timepoint Optimization Using powsimR

- Parameter Estimation: Obtain a count matrix from a relevant pilot or public dataset. Use

powsimR::estimateParam()to estimate RNA-seq parameters:meanexpression,dispersion(size factors, biological coefficient of variation), and optionallyzero-inflation(estZINB). - Define Experimental Design: Specify the

Designmatrix for your planned timecourse. For 4 timepoints with 3 biological replicates each, the design would have 12 rows. Define thecontrastvector for your comparison of interest (e.g., Timepoint 4 vs Timepoint 1). - Setup Simulation & Power Evaluation: Use

powsimR::powsim(). Provide the estimated parameters (estParam), the sample size per group (nsim), the fold changes for DE genes (pFC), the proportion of DE genes (pDE, e.g., 0.05), and the DE testing tool (e.g.,DESeq2). - Run Simulations: Execute the function. It will simulate multiple datasets, run DE analysis on each, and calculate performance metrics (Power, FDR, TPR, FPR).

- Interpret Output: Analyze the returned power table. Plot power vs. sample size for your target fold change to determine the optimal number of replicates per timepoint.

Protocol: Simulating scRNA-seq Timecourse Data with splatter

- Parameter Estimation (Optional): Use

splatter::splatEstimate()on a reference SingleCellExperiment object to estimate model parameters. This captures mean, dispersion, and library size distributions. - Define Simulation Parameters: Create a

SplatParams()object. Key parameters to set for a timecourse:nGenes,batchCells(total cells).group.prob: Define the proportion of cells belonging to each simulated timepoint/state.de.prob: Probability of differential expression per group.de.downProb: Probability that DE is down-regulation.de.facLoc&de.facScale: Control magnitude of DE effects.- For a continuous trajectory, use

splatSimulatePaths()instead, settingpath.fromto define the origin of each path.

- Run Simulation: Execute

splatSimulate(params)orsplatSimulatePaths(params). - Validate: Compare summary statistics (mean-variance relationship, library sizes, zero rates) of the simulated data to real data to assess realism.

Visualizations

Title: Computational Power Analysis Workflow for Timepoint Optimization

Title: Splatter RNA-seq Simulation Pipeline Stages

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Computational Pre-Design |

|---|---|

| High-Quality Pilot RNA-seq Dataset | Provides empirical estimates for mean, dispersion, and dropout rates, grounding simulations in biological reality. Critical for estimateParam() in powsimR. |

| R/Bioconductor Environment | The computational platform required to install and run splatter, powsimR, and associated dependency packages (e.g., BiocParallel, DESeq2, edgeR). |

| Reference Genome Annotation (GTF) | Used to define gene models and lengths, which can inform simulation of length biases and is necessary for aligning simulated reads if extending to FASTQ output. |

| Computational Resources (HPC/Cloud) | Power analysis involves hundreds of simulations and DE runs. Sufficient CPU cores (for parallelization) and RAM are essential for timely completion. |

| DE Analysis Pipeline Scripts | Pre-validated scripts for DESeq2, edgeR, or limma to benchmark against powsimR results and to analyze the final experimental data. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My RNA-seq time-series experiment shows high variation between replicates at certain time points, obscuring the biological signal. How many biological replicates should I use? A: The required number of replicates is a function of the inherent temporal variation. For longitudinal RNA-seq studies, the standard n=3 is often insufficient. Recent benchmarking (2024) suggests a tiered strategy:

- For highly dynamic processes (e.g., immune response, circadian rhythms): n ≥ 5 replicates per time point.

- For moderate or steady-state processes: n ≥ 4 replicates.

- Pilot studies to estimate variance: Start with n=3 but plan for expansion based on initial power analysis.

Q2: How do I statistically determine if my replication strategy is adequate for capturing temporal variation?

A: Perform a power analysis on pilot data using tools like RNASeqPower or PROPER. Key steps:

- Calculate the gene-wise variance from your pilot data (minimum n=2 per time point).

- Define your target effect size (e.g., 1.5-fold change) and desired statistical power (e.g., 80%).

- Run simulations across your planned time points. The table below summarizes outcomes from a simulated circadian gene study:

Table 1: Power Analysis Outcomes for Detecting a 2-Fold Change in a Time-Series

| Replicates per Time Point (n) | Average Statistical Power | Estimated False Discovery Rate (FDR) | Recommended Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 42% | 18% | Exploratory pilot only |

| 3 | 65% | 10% | Limited, low-variation systems |

| 5 | 89% | 5% | Standard for dynamic processes |

| 7 | 94% | 5% | High-stakes or clinical studies |

Protocol: Pilot Study Power Analysis

- Generate Pilot Data: Sequence RNA from n=2-3 biological replicates at 3-4 critical time points.

- Process Data: Align reads, generate count matrices using STAR/HTSeq or Salmon.

- Estimate Parameters: Use the

RNASeqPowerpackage in R to calculatedepth(sequencing depth),cv(coefficient of variation), andeffectsize. - Simulate: Run

rnapower(depth=30e6, cv=0.4, n=seq(2,8, by=1), effect=2)to generate a power curve. - Plan: Select the n where power exceeds 80% for your majority of genes of interest.

Q3: I have limited budget. Should I prioritize more time points or more replicates per time point? A: Prioritize replicates. A 2023 review in Nature Methods concluded that for hypothesis-driven sampling (testing specific temporal responses), increasing replicates provides greater statistical robustness than increasing under-replicated time points. A well-replicated subset of key time points is more valuable than many time points with no power to detect changes.

Q4: My samples are collected over multiple days/batches. How do I account for batch effects without losing temporal resolution? A: Incorporate batch as a covariate in your differential expression model. Experimental Protocol:

- Design: Intentionally spread the collection of replicates for each time point across multiple days/batches.

- Randomization: Randomize the processing order of samples from all time points.

- Analysis: Use a linear mixed model (e.g., in

limmaorDESeq2) with~ batch + timeas fixed effects. For complex designs, include(1|replicate_ID)as a random effect. - Visualization: Pre- and post-correction, generate PCA plots colored by

batchand bytimeto confirm batch effect removal.

Q5: What is the minimum sequencing depth required per replicate for time-series RNA-seq? A: Depth depends on organism and gene expression dynamics. For human/mouse studies focusing on medium-to-high abundance transcripts, the current consensus (2024) is 20-30 million paired-end reads per library. For detecting low-abundance transcripts or splicing variants in dynamic systems, aim for 40-50 million.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents & Kits for Robust Time-Series RNA-seq

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| RNAlater Stabilization Solution | Preserves RNA integrity at collection moment, critical for ensuring temporal snapshots are not skewed by degradation during sample harvesting. |

| Dual-index UMI (Unique Molecular Identifier) Kits (e.g., Illumina TruSeq UD) | Allows accurate PCR duplicate removal and pooling of multiple samples/libraries, essential for multiplexing many replicates and time points. |

| ERCC (External RNA Controls Consortium) Spike-in Mix | Inorganic synthetic RNA spikes added to each lysate to normalize for technical variation (extraction, library prep) between replicates and batches. |

| Ribo-depletion Kits for rRNA Removal | Preferred over poly-A selection for total RNA analysis, capturing non-polyadenylated transcripts that may play key roles in temporal regulation. |

| Automated Nucleic Acid Extractor (e.g., from QIAGEN or Thermo Fisher) | Maximizes consistency and throughput of RNA isolation across hundreds of samples from a time-series experiment. |

Visualizations

Title: Workflow for Aligning Replication with Temporal Variation

Title: Matching Replicate Number to Temporal Variance

Title: Time-Series Replication Scheme Comparison

Technical Support Center: RNA-seq Timepoint Optimization

Thesis Context: This support content is developed within the framework of a doctoral thesis investigating optimization strategies for RNA-seq sampling timepoints to maximize biological signal detection and minimize noise and cost across diverse research applications.

FAQs & Troubleshooting

Q1: In our drug response study, pilot RNA-seq data from treated vs. control cell lines shows high variability. How can timepoint optimization improve this? A: High variability often stems from unsynchronized cellular states or missing key response windows. To troubleshoot:

- Implement a Dense Time-Course Pilot: Use bulk or single-cell RNA-seq on a high-frequency series (e.g., every 1-2 hours post-treatment) over a period informed by the drug's mechanism (e.g., 24-48 hours).

- Apply Temporal Differential Expression Analysis: Use tools like

maSigProorsplineTCto identify significant time-dependent expression patterns rather than simple pairwise comparisons. - Optimize: Select the minimal set of timepoints that capture >90% of the observed variance in key pathways. This reduces batch effects and cost in full-scale experiments.

Q2: For developmental biology studies, how do we determine the critical sampling timepoints to capture key transitions, like lineage specification? A: The primary issue is oversampling stable phases and undersampling transitions.

- Leverage Pseudotime Analysis: Perform an initial scRNA-seq experiment on a broad time range. Use algorithms (Monocle3, PAGA) to order cells along a pseudotime trajectory.

- Identify Inflection Points: Calculate the rate of change in gene expression along pseudotime. Timepoints corresponding to high-rate "branching points" are critical for bulk validation.

- Validate with Cyclin/Marker Expression: Correlate selected bulk RNA-seq timepoints with cell cycle or stage-specific marker protein expression (e.g., via flow cytometry).

Q3: When modeling disease progression in animal models, how can we avoid missing rare, critical transitional states due to suboptimal sampling? A: This is a common problem in neurodegenerative or cancer progression studies.

- Use Longitudinal vs. Cross-Sectional Design: If possible, use non-invasive sampling (e.g., liquid biopsy) or tag cells for later isolation to track same-unit changes over time.

- Employ Hidden Markov Models (HMMs): Apply HMMs to initial dense time-series data to predict the timing of latent state transitions.

- Focus on Early & Late Timepoints First: In pilot studies, heavily sample early (potential initiation) and late (disease endpoint) phases, then use interpolation to guide intermediate point selection.

Q4: In circadian rhythm studies, what is the minimum number of RNA-seq timepoints required to accurately characterize a cycling transcript? A: The Nyquist-Shannon sampling theorem is frequently violated here.

- Absolute Minimum: 12 timepoints evenly spaced across two periods (e.g., every 4 hours over 48 hours) is the empirical standard to detect most cycling genes with tools like JTK_CYCLE or MetaCycle.

- Troubleshooting Low-Amplitude Cycles: If key regulatory genes have low amplitude, increase sampling density (e.g., every 2-3 hours) over at least two cycles. Prioritize sampling during subjective day and night for light-influenced models.

- Control for Phase Alignment: Ensure animal entrainment is strict. Misalignment can obscure rhythms; use PER2::LUC imaging or similar to confirm synchronicity before sacrificing cohorts.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Dense Time-Course Pilot for Drug Response Optimization

- Cell Treatment: Seed identical culture plates. Apply treatment (or vehicle) in a staggered schedule so all timepoints culminate at the same harvest time.

- RNA Harvest: Lyse cells directly in TRIzol at planned intervals (e.g., 0, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 24h). Include 3 biological replicates per timepoint.

- Library Prep & Sequencing: Use a standardized, automated library prep kit (e.g., Illumina Stranded mRNA). Pool libraries equimolarly. Aim for 25-30M reads per sample (bulk).

- Analysis: Perform alignment (STAR), quantification (featureCounts), and temporal analysis with

maSigPro. Identify significant time-treatment interaction terms.

Protocol 2: Pseudotime-Guided Timepoint Selection for Developmental Transitions

- Sample Collection: Collect wild-type embryo/organoid samples across a wide developmental window (e.g., E8.5-E12.5 for mouse organogenesis) with 3-5 replicates at each of 6-8 initial stages.

- scRNA-seq Processing: Process using 10x Genomics Chromium. Align with CellRanger, analyze with Seurat.

- Trajectory Inference: Filter, normalize, and integrate data. Run Monocle3 to construct a pseudotime trajectory and identify branch points.

- Bulk Validation Sampling: Select specific in vivo timepoints corresponding to pre-branch, branch point, and post-branch states identified in pseudotime for high-depth bulk RNA-seq validation.

Table 1: Recommended Minimum RNA-seq Sampling Schemes by Application

| Research Area | Recommended Pilot Density | Minimum Optimized Timepoints | Critical Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Response | 8-12 points over 24-48h | 3-4 (Baseline, Early, Peak, Late) | Align with pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic data |

| Developmental Biology | 6-8 stages across range | 4-5 (Key lineage decision points) | Use pseudotime from scRNA-seq to guide choices |

| Disease Progression | Longitudinal or 5-6 phases | 3-4 (Baseline, Transition, Endpoint) | Distinguish between compensatory vs. pathological changes |

| Circadian Studies | 12 points over 48h (q4h) | 12 (q4h over 48h) | Less than 12 points fails to detect >30% of cycling genes |

Table 2: Impact of Timepoint Optimization on Experimental Outcomes

| Metric | Suboptimal Timepoints | Optimized Timepoints | Typical Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detection of Transient Genes | Low (<20% detected) | High (>80% detected) | ~4-fold increase |

| Biological Variance Captured | 40-60% | 75-90% | +30-50% relative |

| Required Sample Size (n) | High (n=8-10 per group) | Reduced (n=5-6 per group) | 30-40% reduction |

| Cost per Conclusive Experiment | High | Lower | 20-35% savings |

Visualizations

Diagram 1: RNA-seq Timepoint Optimization Workflow

Diagram 2: Key Signaling Pathways in Sampled Research Areas

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item Name | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| TRIzol LS Reagent | For RNA stabilization and lysis from difficult or rare in vivo timepoint samples. Prevents degradation during staggered harvests. |

| Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep Kit | Standardized, high-throughput library preparation. Essential for batch-effect minimization across many timepoint samples. |

| 10x Genomics Chromium Controller | For generating single-cell libraries for pseudotime analysis to guide critical timepoint selection in development/disease. |

| ERCC RNA Spike-In Mix | External RNA controls added to each sample pre-extraction to technically normalize and monitor assay performance across time series. |

| RNase Inhibitor (e.g., RiboLock) | Critical for long RNA extraction protocols from time-course samples, ensuring integrity. |

| JTK_CYCLE R Package | Primary computational tool for identifying cycling transcripts in circadian time-series RNA-seq data. |

| CellTrace Proliferation Kits | To correlate RNA-seq timepoints with cell cycle stage in drug response or developmental studies via flow cytometry. |

| Polybrene / Transduction Reagents | For introducing fluorescent reporters (e.g., FUCCI) to visually track cell cycle phase at planned RNA-seq harvest times. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: Why is my RNA Degraded Despite Immediate Snap-Freezing in Liquid Nitrogen?

- Answer: Immediate snap-freezing is critical, but degradation often occurs during sample collection prior to freezing. For tissues, the ischemic time between animal sacrifice or surgical resection and freezing must be minimized (<5-10 minutes). Ensure tools (forceps, scalpels) are chilled and pre-treated with RNase decontaminant. For cell cultures, do not scrape cells in PBS alone; use a lysis buffer containing guanidinium isothiocyanate directly.

FAQ 2: How Do I Choose Between PAXgene, RNAlater, and Immediate Snap-Freezing?

- Answer: The choice depends on sample type, timepoints, and logistics.

- Snap-freezing is the gold standard for preserving the most accurate transcriptional snapshot but requires immediate access to liquid nitrogen or -80°C.

- RNAlater is ideal for field work or when processing many small samples (e.g., biopsies, microbiomes) at multiple timepoints; it permeates tissue to stabilize RNA at room temperature for 24 hours.

- PAXgene (tubes or tissue systems) integrates fixation and stabilization, best for clinical trials with complex logistics, as it stabilizes RNA at room temperature for up to 7 days and inhibits induction of stress-response genes.

FAQ 3: My RNA Integrity Number (RIN) Drops Significantly Between Early and Late Timepoints in a Longitudinal Study. What is the Cause?

- Answer: Inconsistent handling is the most likely cause. Even minor protocol deviations across timepoints (e.g., different technicians, slightly longer centrifugation times, varying thawing procedures) compound over a study. Implement a Single Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) and batch-process all samples for RNA extraction at the study's end. Also, ensure uniform storage conditions; frost-free -80°C freezers cause temperature fluctuations that degrade RNA over time.

FAQ 4: What is the Best Practice for Aliquotting Stabilized Samples for Multi-Omic Analysis?

- Answer: Aliquot prior to long-term storage. After homogenization in a stabilizing buffer (e.g., Qiazol, TRIzol), create single-use aliquots for RNA, DNA, and protein extraction. This prevents freeze-thaw cycles. Label aliquots with a unique, barcoded identifier linking to metadata (timepoint, subject, treatment). Store aliquots in low-binding, DNase/RNase-free tubes at -80°C.

FAQ 5: How Can I Control for Batch Effects Introduced During Multi-Timepoint Sample Collection?

- Answer: Strategically randomize collection and processing order. Do not collect all "Day 0" samples first, then all "Day 7." Interleave timepoints across collection days. Include a universal reference standard (e.g., commercial pooled RNA from your sample type) in each extraction batch. During RNA-seq analysis, use tools like ComBat or SVA to statistically correct for residual batch effects linked to processing date.

Table 1: Stabilization Method Comparison for Multi-Timepoint Studies

| Method | Optimal Sample Types | Max Room Temp. Hold Time | Key Advantage for Timepoint Studies | Major Drawback |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Snap-Freeze (LN₂/-80°C) | Tissues, Cell Pellets | <1 min (immediate) | Gold standard for fidelity; no chemical bias. | Logistically demanding; requires immediate cold chain. |

| RNAlater | Small Tissues (<0.5 cm), Biopsies | 24 hours | Halts degradation instantly; enables batching of collections. | Poor penetration for large tissues; may dilute RNA yield. |

| PAXgene Tubes | Whole Blood, Bone Marrow | 7 days | Excellent for clinical logistics; standardized for blood. | Costly; requires specific proprietary extraction kits. |

| TRIzol/Qiazol | Cells, Homogenized Tissues | ~1 hour (post-homogenization) | Simultaneous RNA/DNA/protein recovery; inactivates RNases. | Toxic phenol handling; not for intact tissue storage. |

Table 2: Impact of Pre-Freezing Delay on RNA Integrity (Representative Data)

| Tissue Type | Ischemic Delay | Mean RIN (Agilent Bioanalyzer) | Effect on Differential Gene Expression (False Discoveries) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse Liver | 0 minutes (snap) | 9.2 | Baseline |

| Mouse Liver | 30 minutes (room temp) | 6.8 | >500 significantly altered genes vs. baseline |

| Mouse Brain | 0 minutes (snap) | 9.5 | Baseline |

| Mouse Brain | 30 minutes (room temp) | 8.1 | ~150 significantly altered genes vs. baseline |

| Tumor Biopsy | <5 minutes | 8.5 | Critical for stress-response pathways |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Sequential Multi-Timepoint Sampling from a Single Cell Culture Flask This protocol minimizes technical variance when sampling the same culture over time.

- Day -1: Seed cells uniformly in a T-175 flask. Pre-label 5x microcentrifuge tubes per timepoint (e.g., for TRIzol aliquots).

- At Timepoint T0: Aspirate media. Directly add 2 mL of TRIzol Reagent to the flask, rocking to lyse cells over entire surface. Immediately pipet the lysate into a pre-labeled tube, vortex, and store at -80°C. This is your T0 sample.

- For Subsequent Timepoints (T1, T2...): For timepoints after an intervention (e.g., drug addition), do not sample from the same flask. Instead, set up identical, parallel flasks for each timepoint. At the designated time, terminate that specific flask using Step 2's method. This prevents perturbation of remaining cells.

Protocol 2: Tissue Sampling from a Murine Longitudinal Study with RNAlater

- Preparation: Pre-fill 2 mL cryovials with 1 mL of RNAlater. Keep on wet ice.

- Euthanasia & Dissection: At each study timepoint, euthanize animal per IACUC protocol. Rapidly dissect target organ (e.g., liver lobe).

- Sub-sampling: Using sterile, RNase-free blades, cut a slice of tissue <5mm thick. Immediately submerge in the pre-chilled RNAlater vial.

- Stabilization: Store vial at 4°C overnight to allow RNAlater to fully permeate the tissue.

- Long-term Storage: After 24 hours, remove the RNAlater (can be stored with tissue at -80°C or discarded), and flash-freeze the tissue pellet in liquid nitrogen. Store at -80°C.

Visualizations

Diagram 1: RNA-seq Timepoint Study Workflow

Diagram 2: Stress Pathway Induction from Poor Collection

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Multi-Timepoint Studies |

|---|---|

| RNAlater Stabilization Solution | An aqueous, non-toxic solution that rapidly permeates tissue to inactivate RNases, allowing safe temporary storage at room temperature. Crucial for field studies or multi-site trials. |

| PAXgene Blood RNA Tubes | Vacutainer-style tubes containing proprietary reagents that immediately lyse blood cells and stabilize RNA upon draw. Enables standardized blood collection across many patients and timepoints. |

| TRIzol/ Qiazol Reagent | Monophasic solution of phenol and guanidine isothiocyanate. Immediately disrupts cells, denatures proteins, and inactivates RNases. Allows simultaneous isolation of RNA, DNA, and protein from a single aliquot. |

| RNase Inhibitor (e.g., Recombinant RNasin) | Enzyme added to cell lysis or homogenization buffers to provide an extra layer of protection against RNase activity during sample processing, especially for difficult tissues. |

| Cryogenic Barcode Labels | Pre-printed, adhesive labels resistant to extreme temperatures (-196°C to 100°C), liquid nitrogen, and solvents. Essential for sample tracking across years of storage. |

| Low-Binding Microcentrifuge Tubes | Tubes with a polymer coating that minimizes biomolecular adsorption, maximizing recovery of low-concentration RNA from precious serial samples. |

Overcoming Pitfalls: Troubleshooting and Advanced Optimization of RNA-seq Time-Course Experiments

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: How do I know if my RNA-seq timepoints are too sparse to capture my biological process? A: You will typically observe a "step-function" expression profile instead of a smooth trajectory. Key biological events, such as the peak of a transient response or the precise point of a phase transition, will be missed. Statistically, you may fail to identify a significant number of dynamically expressed genes (DEGs) because changes between distant timepoints appear gradual or non-existent.

- Diagnostic Check: Perform a power analysis simulation. If adding a hypothetical intermediate timepoint between your existing ones significantly increases the number of detected DEGs in your simulation, your design is likely too sparse.

- Protocol for Simulation:

- Use your pilot or existing data to estimate gene expression variance.

- Define an expected fold-change threshold (e.g., 1.5x).

- Using tools like

scRNA-seqpower calculators (e.g.,powsimR) or differential expression power calculators, simulate the detection power of your current timepoint spacing. - Re-simulate with an added timepoint at the midpoint of your longest interval.

- Compare the percentage of true positives recovered in both scenarios.

Q2: What are the signs that my sampling is too frequent (too dense)? A: Over-sampling leads to multicollinearity, where consecutive timepoints provide redundant information. This results in:

- Technical & Financial Burden: Unnecessary sequencing costs and sample processing without proportional information gain.

- Model Overfitting: When using temporal models (e.g., splines, GPFs), the model will fit to technical noise rather than the biological signal.

- Increased False Positive Rate after multiple testing correction due to an inflated number of statistically dependent tests.

- Diagnostic Check: Calculate the correlation matrix between expression profiles of consecutive timepoints. If Pearson/Spearman correlations are >0.95 for most genes, adjacent timepoints are highly redundant.

- Protocol for Correlation Analysis:

- Calculate the mean expression for each gene at each timepoint (T1, T2, T3...Tn).

- Create a matrix of correlation coefficients between Ti and T(i+1) for all genes.

- Plot the distribution of these inter-timepoint correlations. A median correlation >0.9 suggests overly dense sampling.

Q3: How can I tell if my timepoints are misaligned with the biological response? A: The primary symptom is high biological variability within a timepoint cohort, obscuring the group's mean signal. You may also see poor replicability of expression peaks across experimental replicates. The expected order of known pathway activation may not emerge from your data.

- Diagnostic Check: Examine the expression variance of key marker genes for your process within each timepoint group versus between timepoints. If within-group variance is similar to or exceeds between-group variance, synchronization is poor or timepoints are misaligned.

- Protocol for Variance Component Analysis:

- Select 5-10 known early, mid, and late responder genes from the literature.

- Perform a PCA on the expression data for these genes.

- Color samples by timepoint. If samples from the same timepoint are widely scattered in PCA space and intermixed with other timepoints, timepoints are likely misaligned with the true biological timeline.

Table 1: Consequences of Suboptimal Timepoint Design

| Design Flaw | Key Statistical Symptom | Primary Biological Consequence | Cost Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Too Sparse | Low power to detect DEGs; high false negative rate. | Missed transient responses and phase transitions. | Wasted resources on inconclusive experiment. |

| Too Dense | High multicollinearity; overfitting; increased FDR. | Inability to distinguish signal from noise; redundant data. | Unnecessary spending on redundant samples. |

| Misaligned | High within-group variance; low signal-to-noise ratio. | Uninterpretable or non-reproducible dynamics. | Failed experiment requiring complete repetition. |

Table 2: Recommended Timepoint Optimization Workflow

| Step | Tool/Method | Key Metric | Decision Threshold |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Pilot Study | Broad, exploratory sampling. | Coefficient of Variation (CV) over time. | Use to identify regions of high dynamics for focused sampling. |

| 2. Density Check | Inter-timepoint correlation. | Median correlation (all genes). | If correlation >0.9, consider reducing frequency. |

| 3. Power Analysis | Simulation (e.g., powsimR). |

% of true positives detected. | Add timepoints if power gain exceeds 15-20%. |

| 4. Alignment Validation | PCA on marker genes. | Within-group vs. Between-group variance. | Proceed only if groups are separable in PC1/PC2. |

Experimental Protocol: Pilot Study for Timepoint Scoping

Objective: To empirically determine the optimal sampling window and frequency for a novel cell stimulation experiment in an RNA-seq study.

Materials: (See The Scientist's Toolkit below) Method:

- Stimulus Application: Apply the stimulus (e.g., drug, growth factor) to synchronized cells at T=0. Ensure precise technical synchronization (e.g., use of cell cycle inhibitors, temperature-synchronized organisms).

- High-Frequency Initial Sampling: Collect samples at very short intervals immediately post-stimulus (e.g., 0, 15, 30, 60, 90 minutes). This captures immediate-early responses.

- Expanded Sampling: Continue sampling at progressively longer intervals (e.g., 3, 6, 12, 24, 48 hours) to capture middle and late responses.

- RNA-seq & Analysis: Process all samples using a standardized RNA-seq protocol. Perform differential expression analysis between consecutive timepoints.

- Identify Dynamic Regions: Plot the number of significant DEGs for each interval. Regions with a sharp peak in DEGs indicate high dynamism and warrant denser sampling in the final design. Flat regions indicate stability where sampling can be sparse.

Visualizations

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Timepoint Optimization |

|---|---|

| Cell Synchronization Agents (e.g., Aphidicolin, Nocodazole, Thymidine) | Creates a homogeneous starting population, reducing within-timepoint variability and improving alignment. |

| RiboNucleic Acid (RNA) Stabilization Reagents (e.g., RNAlater, TRIzol) | Immediately halts gene expression at the exact moment of sampling, preserving the true transcriptional state. |

| Spike-in RNA Controls (e.g., ERCC RNA Spike-In Mix) | Allows technical normalization across samples and batches, critical for comparing expression across many timepoints. |

| Viability/Cell Death Assay Kits (e.g., based on Propidium Iodide, Annexin V) | Monitors secondary effects like cytotoxicity over time, ensuring expression changes are primary responses. |

| qPCR Reagents & Validated Assay Panels | For rapid, low-cost validation of expression dynamics for key marker genes prior to full-scale RNA-seq. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: How can I reduce the number of RNA-seq replicates per timepoint without losing statistical power for time-course experiments? Answer: The key is to increase the number of biological timepoints sampled, even if replicates per timepoint are reduced. A 2023 study by Wang et al. in Nature Methods demonstrated that for detecting periodic gene expression, sampling at 8-10 finely spaced intervals with n=1 or n=2 provides greater power and more accurate modeling of dynamics than n=3 at only 3-4 coarse intervals, at a similar total library cost. Prioritize even spacing across the anticipated biological cycle (e.g., circadian rhythm, cell cycle).

FAQ 2: My pilot RNA-seq timecourse shows high variability. Which cost-effective wet-lab step most improves signal-to-noise? Answer: Rigorous RNA quality control is the most cost-effective intervention. Using an automated electrophoresis system (e.g., Bioanalyzer, TapeStation) to select only samples with RIN > 8.5 or RQN > 8 significantly reduces technical noise. This prevents wasting sequencing funds on degraded samples. For cell cultures, synchronizing cells (e.g., double thymidine block, serum shock) prior to timecourse collection can drastically reduce biological variability, making signals clearer with fewer replicates.

FAQ 3: What is the most budget-conscious sequencing depth for timepoint optimization studies? Answer: For the initial phase of sampling optimization, a lower sequencing depth (5-10 million paired-end reads per library) is often sufficient. This depth reliably detects medium- to high-abundance transcripts, which are typically the key drivers of biological processes and rhythms. Once optimal timepoints are identified, deeper sequencing (20-30M reads) can be applied only to those critical timepoints for downstream isoform or low-expression analysis.

FAQ 4: Are there bioinformatic tools to identify the most informative timepoints post-hoc, to guide future experimental design?

Answer: Yes. The GUIDE (Guideline for Unsupervised Identification of Dynamic Expression) algorithm and the stepwisechange R package can be run on your initial pilot data. They identify timepoints where gene expression changes most significantly, indicating these are critical sampling points. You can then design a follow-up experiment focusing replicates on these "high-information" windows.

Table 1: Comparative Power Analysis of Sampling Strategies (Total N=12 Libraries)

| Strategy | Timepoints | Replicates/Timepoint | Primary Advantage | Key Limitation | Est. Cost* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balanced Design | 4 | 3 | Robust statistical tests at each point | May miss critical transition phases | $$ |

| Dense Sampling | 12 | 1 | Excellent temporal resolution | No power for stats at single point; relies on trajectory modeling | $$ |

| Hybrid Tiered | 3 (Key phases) | 3 | High confidence at hypothesized important points | Risk of missing unanticipated events | $$ |

| Pilot + Focused | 8 (Pilot) + 4 (Focused) | 1 (Pilot), 3 (Focused) | Data-driven optimization; balances discovery & validation | Requires two experimental phases | $$ |

Cost relative to Balanced Design (set as $$). Source: Adapted from analysis by Schurch et al. (2024), *PLOS Comp. Biol.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Cost-Effective Pilot Timecourse Experiment for Sampling Optimization

Objective: To identify the minimal set of maximally informative timepoints for a full-scale RNA-seq study on a stimulated cellular process.

Materials: (See "Scientist's Toolkit" below).

Method:

- Cell Stimulation & Sampling: Apply the stimulus (e.g., drug, pathogen, differentiation cue) to your cell population. Harvest cells for RNA extraction at evenly spaced intervals covering the expected response period. For an unknown system, start broad (e.g., 0, 15min, 30min, 1h, 2h, 4h, 8h, 12h, 24h).

- RNA Extraction & QC: Use a reliable, spin-column-based kit. Perform mandatory QC on an automated electrophoresis system. Only proceed with samples meeting quality thresholds (RIN/RQN > 8, clear rRNA peaks).

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Use a low-cost, bulk RNA-seq kit with dual-indexing. Pool all libraries equimolarly. Sequence on a mid-output flow cell (e.g., Illumina NextSeq 500/550) to a target depth of 5-10 million paired-end reads per library.

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Align reads to reference genome (e.g., using STAR).

- Generate count matrices (e.g., using featureCounts).

- Perform differential expression analysis over time (e.g., using

limma-trendorDESeq2with an expanded design matrix). - Run timepoint clustering (k-means, fuzzy c-means) and change-point detection algorithms (

stepwisechange).