Maximum Likelihood vs. Bayesian Frameworks for Introgression Detection: A Guide for Genomic Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of Maximum Likelihood (ML) and Bayesian methods for detecting introgressed genomic regions, a critical task in evolutionary genomics and biomedical research.

Maximum Likelihood vs. Bayesian Frameworks for Introgression Detection: A Guide for Genomic Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of Maximum Likelihood (ML) and Bayesian methods for detecting introgressed genomic regions, a critical task in evolutionary genomics and biomedical research. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational principles of both approaches, from core statistical philosophies to specific algorithmic implementations like Aphid (ML) and BPP (Bayesian). The content delves into practical application guidelines, troubleshooting for common pitfalls like model misspecification, and a rigorous validation of methodological performance under various evolutionary scenarios. By synthesizing key strengths and limitations, this review serves as a strategic guide for selecting and applying the most appropriate introgression detection framework to uncover evolutionarily significant gene flow with potential clinical relevance.

Core Principles of Introgression Detection: From Phylogenetic Conflict to Statistical Frameworks

Defining Introgression and Its Impact on Genomic Evolution

Introgression, also known as introgressive hybridization, is the transfer of genetic material from one species into the gene pool of another through the repeated backcrossing of an interspecific hybrid with one of its parent species [1]. This process differs from simple hybridization, which results in a relatively even mixture in the first generation, as introgression produces a complex, highly variable mixture of genes and may involve only a minimal percentage of the donor genome [1]. The process requires both initial hybridization and subsequent backcrossing events for foreign genetic variants to become permanently incorporated into the recipient gene pool [2].

Introgression has been identified across diverse taxa, from plants and animals to bacteria and humans [1] [3] [4]. Well-documented examples include Neanderthal and Denisovan gene flow into modern humans, wing pattern mimicry in Heliconius butterflies, herbicide resistance in sunflowers, and rodenticide resistance in house mice [1] [3]. Recent genomic analyses suggest introgression is far more common than previously recognized, with Mallet estimating that at least 25% of plant species and 10% of animal species experience hybridization and potential introgression [5].

Evolutionary Impact of Introgression

Adaptive Introgression and Genetic Variation

Introgression serves as an important source of genetic variation in natural populations and can contribute significantly to adaptation and adaptive radiation [1]. This "adaptive introgression" occurs when transferred genetic material results in an overall increase in the fitness of the recipient taxon [1]. Instead of waiting for beneficial mutations to arise de novo, gene flow can introduce variation that has been "pre-tested" by selection in another species, enabling rapid evolutionary responses [3].

Documented cases of adaptive introgression include alleles causing brown winter coat color in snowshoe hares, early flowering time in sunflowers, serpentine soil tolerance in Arabidopsis, and industrial pollution tolerance in Gulf killifish [3]. In some notable cases, populations developed resistance to strong selective pressures (e.g., pesticides and industrial pollutants) in fewer than 20 generations after initial introgression [3]. Supergenes—linked groups of loci in chromosomal inversions—can also introgress adaptively between species, as documented for colony social organization in fire ants and wing color patterns in Heliconius butterflies [3].

Genomic Landscapes of Introgression

Introgression does not occur evenly across the genome. Certain genomic regions introgress more or less readily than others, creating distinct "genomic landscapes of introgression" [3]. Genome-wide analyses reveal that introgressed ancestry is rapidly purged in early generations after hybridization, with specific genomic features correlating with retention or loss of introgressed DNA [3].

Table 1: Genomic Features Affecting Introgression Patterns

| Genomic Feature | Effect on Introgression | Proposed Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| High gene density | Reduced introgression | Interference with gene function in foreign genetic background |

| Low recombination rates | Reduced introgression | Inability to uncouple beneficial from harmful linked genes |

| Hybrid incompatibility loci | Strong resistance to introgression | Strong selection against incompatible gene combinations |

| Adaptive loci | Increased introgression | Positive selection for beneficial alleles |

Genes involved in hybrid incompatibilities—those that evolved within one genetic background and are harmful in another—act as local roadblocks to introgression [3]. These incompatible genotype combinations are unlikely to introgress due to strong selective pressure for their removal after initial hybridization [3]. To date, only a handful of genetic incompatibilities have been characterized at the gene level, including the interaction between xmrk and cd97 causing melanoma in swordtail fish hybrids, and mitochondrial-nuclear interactions causing hybrid lethality [3].

Detection Methods: Bayesian vs. Maximum Likelihood Approaches

Methodological Frameworks

The precise identification of introgressed loci represents a rapidly evolving area of research, with current methods falling into three major categories: summary statistics, probabilistic modeling, and supervised learning [6]. For the comparison of Bayesian and maximum likelihood frameworks, both fall under probabilistic modeling approaches that provide powerful frameworks for explicitly incorporating evolutionary processes [6].

Maximum Likelihood methods aim to find the parameter values that maximize the likelihood function, representing the probability of observing the data given specific parameters. These methods typically provide point estimates without directly quantifying uncertainty.

Bayesian methods incorporate prior knowledge and update beliefs based on observed data, providing posterior distributions that quantify uncertainty in parameter estimates. These approaches naturally accommodate complex models and provide intuitive probabilistic outputs.

Key Method Implementations

Table 2: Representative Bayesian and Maximum Likelihood Methods for Introgression Detection

| Method | Framework | Key Features | Applications | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPP | Bayesian (MCMC) | Implements multispecies coalescent with introgression (MSci); accounts for ILS | Chipmunk phylogenomics; detected ancient nuclear introgression missed by heuristic methods | [7] |

| PhyloNet-HMM | Maximum Likelihood/HMM | Combines phylogenetic networks with hidden Markov models; accounts for ILS and dependencies | Mouse chromosome 7 analysis; detected adaptive introgression of Vkorc1 gene | [5] |

| df-BF | Bayesian (conjugate priors) | Distance-based Bayes Factors; fast computation without MCMC | Mosquito whole-genome data; accurate quantification of introgression | [8] |

| ASTRAL | Maximum Likelihood | Species tree estimation from gene trees; accounts for ILS | Cichlid phylogenomics; gene tree-species tree reconciliation | [9] |

Performance Comparison

Recent benchmarking studies have evaluated the performance of various introgression detection methods. A 2025 study evaluated adaptive introgression classification methods (VolcanoFinder, Genomatnn, and MaLAdapt) and the standalone statistic Q95(w, y) across evolutionary scenarios inspired by human, wall lizard, and bear lineages [10]. The results highlighted the importance of including adjacent genomic windows in training data to correctly identify windows containing adaptively introgressed mutations, with Q95-based methods proving most efficient for exploratory studies [10].

A 2022 analysis of Tamias chipmunks provided direct comparison between heuristic (HYDE) and Bayesian (BPP) approaches [7]. The Bayesian method detected robust evidence for multiple ancient introgression events with probabilities reaching 63%, while the heuristic method lacked power when gene flow occurred between sister lineages or when the mode of gene flow didn't match assumptions of symmetrical population sizes [7]. This demonstrates how likelihood-based methods can detect introgression that summary statistics miss.

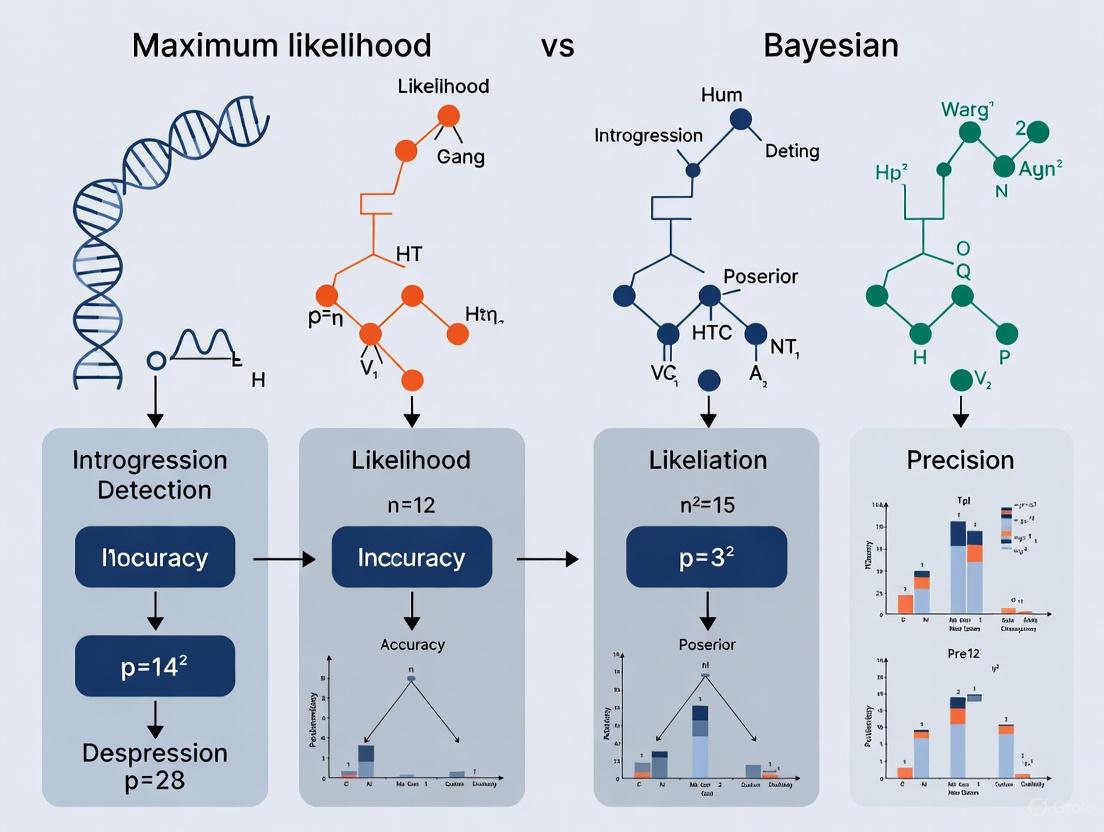

Figure 1: Comparative workflow for Bayesian and Maximum Likelihood introgression detection methods

Experimental Protocols and Case Studies

Protocol 1: Bayesian Analysis with BPP

The Bayesian re-analysis of Tamias chipmunks exemplifies a robust protocol for detecting introgression using BPP [7]:

Data Preparation: Obtain targeted sequence-capture data from thousands of nuclear loci (mostly genes or exons) across multiple species.

Model Selection: Begin with a well-supported binary species tree and add introgression events sequentially using a stepwise approach to construct a joint multispecies coalescent with introgression (MSci) model.

Bayesian Test of Introgression: Calculate Bayes factors via the Savage-Dickey density ratio using Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) samples under the introgression model.

Parameter Estimation: Estimate population parameters, including divergence times, population sizes, and introgression probabilities.

Model Comparison: Compare models with and without introgression events, giving preference to models that account for ancient cross-species gene flow to avoid serious underestimation of species divergence times.

This approach successfully detected multiple ancient introgression events in chipmunk nuclear genomes that were missed by the heuristic method HYDE, with introgression probabilities reaching 63% [7].

Protocol 2: PhyloNet-HMM Analysis

The PhyloNet-HMM framework provides a maximum likelihood approach for scanning genomes for signatures of introgression [5]:

Input Data Preparation: Compile a set of aligned genomes of length L and a set of parental species trees representing possible evolutionary histories.

Model Training: Train the model on genomic data using dynamic programming algorithms paired with a multivariate optimization heuristic.

Site-specific Probability Calculation: For each site i, calculate the probability P(Ψi = S | X) for every parental species tree S, where Ψi represents the evolutionary history at site i.

Genomic Region Annotation: Identify regions of introgressive descent based on sites where the parental species tree differs from the expected species tree.

Ancestry Tracing: Deduce the evolutionary history of every site, enabling identification of introgressed regions, detection of recombination within introgressed regions, and characterization of introgressed segment length distributions.

Application to mouse chromosome 7 data detected the adaptive introgression of the rodent poison resistance gene Vkorc1 and estimated that approximately 9% of sites within chromosome 7 (covering about 13 Mbp and over 300 genes) were of introgressive origin [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Introgression Studies

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Example Applications | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whole-genome alignment data | Provides homologous sequences across species for phylogenetic analysis | Extracting alignment blocks for gene tree estimation; cichlid chromosome 5 analysis | [9] |

| Targeted sequence-capture loci | Enriches for thousands of nuclear loci (genes/exons) across multiple species | Chipmunk phylogenomics; nuclear introgression detection | [7] |

| BPP software | Bayesian implementation of multispecies coalescent with introgression (MSci) | Detecting ancient introgression events; parameter estimation | [7] |

| PhyloNet/PhyloNet-HMM | Infers species networks incorporating hybridization and introgression | Mouse introgression scanning; phylogenetic network modeling | [5] [9] |

| ASTRAL | Estimates species trees from gene trees while accounting for incomplete lineage sorting | Gene tree-species tree reconciliation; cichlid phylogenomics | [9] |

| IQ-TREE | Performs maximum likelihood phylogenetic inference rapidly and accurately | Generating gene trees from alignment blocks | [9] |

Figure 2: Method selection guide for introgression detection based on research requirements

Discussion and Future Directions

The comparison between Bayesian and maximum likelihood approaches for introgression detection reveals complementary strengths. Bayesian methods provide natural uncertainty quantification and flexibility for complex models but often require substantial computational resources [7] [8]. Maximum likelihood approaches typically offer faster computation and scalability to genome-wide data but may lack comprehensive uncertainty measures [5] [9].

Future methodological development will likely focus on improving scalability while maintaining statistical rigor, better distinguishing introgression from incomplete lineage sorting, and detecting increasingly ancient introgression events [6] [3]. Supervised learning represents an emerging approach with particular promise when detecting introgressed loci is framed as a semantic segmentation task [6].

As these methods continue to evolve, they will help answer fundamental questions about evolutionary history: How common is adaptive introgression? How frequent was introgression from now-extinct lineages? How effective is introgression as a mechanism of evolutionary rescue in threatened species? [3]. The integration of multiple approaches—Bayesian, maximum likelihood, and emerging machine learning methods—will provide the most powerful framework for decoding genomic landscapes of introgression across diverse taxa [6].

In evolutionary biology, the detection and quantification of introgression—the flow of genes between species—is crucial for understanding biodiversity, adaptation, and speciation. This process, which can transfer adaptive traits across species boundaries, presents significant statistical challenges for quantification. The field is primarily divided between two competing statistical philosophies: the frequentist approach, epitomized by Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE), and Bayesian inference. These frameworks offer fundamentally different approaches to parameter estimation, uncertainty quantification, and hypothesis testing in introgression research. While MLE seeks to find the single best-fitting parameter values from observed data alone, Bayesian methods incorporate prior knowledge to generate probability distributions over possible parameter values, offering a different perspective on statistical evidence [11] [12]. The choice between these paradigms profoundly influences how researchers model evolutionary processes, interpret genomic evidence, and draw conclusions about evolutionary history. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of these competing methodologies within the specific context of introgression detection research, examining their theoretical foundations, experimental applications, performance characteristics, and practical implementations.

Theoretical Foundations and Philosophical Differences

Core Principles of Maximum Likelihood Estimation

Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) operates on frequentist principles, treating parameters as fixed, unknown quantities to be estimated solely from observed data. The core methodology involves identifying the parameter values that maximize the likelihood function, which represents the probability of observing the collected data given specific parameter values [11] [12]. In mathematical terms, for a parameter vector θ and observed data D, MLE seeks to find θ̂ that maximizes L(θ|D) = P(D|θ) [11]. For introgression detection, this typically involves computing probabilities of observed genomic patterns (such as ABBA/BABA site counts) under different evolutionary scenarios [13]. The MLE framework depends entirely on the observed data, with no formal mechanism for incorporating previous knowledge or expert opinion. Interval estimation in MLE produces confidence intervals, which represent the range that would contain the true parameter value in a specified percentage of repeated experiments, though this is often misinterpreted as a probabilistic statement about the parameter [14]. For genomic applications, MLE methods are computationally efficient and benefit from well-established asymptotic properties, but they can produce biased estimates with limited data and offer limited uncertainty quantification compared to Bayesian alternatives [11] [14].

Fundamental Tenets of Bayesian Estimation

Bayesian estimation represents a fundamentally different approach, treating all parameters as random variables with probability distributions that represent uncertainty about their true values [15]. Rather than seeking single point estimates, Bayesian methods combine prior knowledge with observed data to produce complete posterior distributions for parameters. This framework is built upon Bayes' Theorem, which in this context takes the form: P(θ|D) = [P(D|θ) × P(θ)] / P(D), where P(θ|D) is the posterior distribution of parameters given the data, P(D|θ) is the likelihood function, P(θ) is the prior distribution representing previous knowledge, and P(D) is the marginal probability of the data [11] [12] [14]. For introgression studies, the prior P(θ) might incorporate information from previous phylogenetic studies or known evolutionary constraints [13]. The posterior distribution P(θ|D) provides a complete probabilistic summary of parameter uncertainty after considering both prior knowledge and observed data. Bayesian interval estimates (credible intervals) have a more intuitive interpretation than frequentist confidence intervals, directly representing the probability that a parameter lies within a specified range [14]. This approach particularly benefits complex models where parameters have natural constraints, as priors can restrict the parameter space to biologically plausible values [13].

Philosophical and Computational Comparisons

The philosophical distinctions between these approaches lead to practical differences in implementation and interpretation. The table below summarizes key contrasting features:

Table 1: Philosophical and Methodological Comparisons

| Aspect | Maximum Likelihood Estimation | Bayesian Estimation |

|---|---|---|

| Parameter Treatment | Fixed, unknown quantities | Random variables with distributions |

| Uncertainty Quantification | Confidence intervals based on repeated sampling | Credible intervals from posterior distribution |

| Prior Knowledge | No formal incorporation | Explicitly incorporated via prior distributions |

| Output | Point estimates | Complete probability distributions |

| Computational Demand | Generally lower | Generally higher |

| Interpretation | Frequency-based (long-run behavior) | Probability-based (degree of belief) |

Computationally, MLE typically involves optimization problems to find parameter values that maximize the likelihood function, often using gradient-based methods or expectation-maximization algorithms [11]. Bayesian estimation, conversely, requires integration over parameter spaces, which frequently necessitates Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods or variational inference to approximate posterior distributions [15] [14]. The computational burden of Bayesian methods has historically limited their application, though advances in computing power and algorithms have made them increasingly accessible [14].

Experimental Protocols for Introgression Detection

Maximum Likelihood Protocols

ABBA-BABA statistical frameworks form the foundation of many MLE-based introgression detection methods. The core protocol involves first identifying genomic regions with specific allele sharing patterns among four taxa: two sister species (P1 and P2), a potential donor species (P3), and an outgroup [13]. Researchers then tabulate sites exhibiting "ABBA" patterns (where P2 and P3 share a derived allele not found in P1) and "BABA" patterns (where P1 and P3 share a derived allele not found in P2). The standard D-statistic (Patterson's D) is computed as D = (ABBA - BABA) / (ABBA + BABA), which measures the imbalance between these two patterns [13]. To estimate introgression parameters, the df statistic implements an MLE approach using the formula: df = ∑(ABBAk - BABAk) / ∑(ABBAk + BABAk + 2·BBAA_k) across k genomic regions, where BBAA represents sites where P1 and P2 share derived alleles not found in P3 [13]. This approach assumes that in the absence of introgression, ABBA and BABA patterns occur at equal frequencies due to incomplete lineage sorting. Significant deviations from this expectation provide evidence of introgression. The method produces point estimates of introgression proportions but does not naturally provide uncertainty measures without additional bootstrapping or asymptotic approximations [13].

Bayesian Estimation Protocols

Bayesian model selection approaches offer an alternative framework for introgression detection. The df-BF method builds upon the df statistic but reformulates the problem as a Bayesian model comparison [13]. The experimental protocol begins with defining two competing models: MABBA, representing introgression between P2 and P3, and MBABA, representing introgression between P1 and P3. For each model, researchers compute marginal likelihoods using conjugate Beta distributions with parameters derived from the observed ABBA, BABA, and BBAA site counts [13]. Specifically, the likelihoods take the forms: P(D|MABBA) ∝ θ₁^(αABBA) · θ₂^(βBBAA) and P(D|MBABA) ∝ θ₁^(αBABA) · θ₂^(βBBAA), where α and β represent transformed counts of the different site patterns [13]. The key innovation in this Bayesian approach is the calculation of Bayes Factors, which compare the evidence for the two models by taking the ratio of their marginal likelihoods [13]. This provides a direct measure of statistical evidence for one introgression scenario over another, with the additional benefit of producing a posterior distribution for the introgression parameter θ that naturally quantifies estimation uncertainty. The method uses conjugate priors, which eliminate the need for computationally demanding MCMC iterations while still providing full posterior distributions [13].

Machine Learning Approaches

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) represent a more recent methodology for detecting adaptive introgression that transcends the traditional MLE-Bayesian dichotomy [16]. The experimental protocol involves simulating genomic data under various evolutionary scenarios (neutral evolution, selective sweeps, and adaptive introgression) to create training datasets. For each genomic window, researchers construct a genotype matrix from multiple populations (donor, recipient, and unadmixed outgroup) [16]. The CNN architecture is then trained to distinguish regions evolving under adaptive introgression from those evolving neutrally or experiencing selective sweeps. This approach leverages the pattern-recognition capabilities of deep learning to identify complex genomic signatures of introgression without requiring an explicit analytical model of the allele frequency dynamics [16]. The trained CNN outputs probabilities for different evolutionary scenarios, providing a classification that can complement traditional parameter estimation methods. This method has demonstrated approximately 95% accuracy on simulated data, even with unphased genomes [16].

Diagram 1: Introgression Detection Workflows

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Accuracy and Convergence Properties

Simulation studies provide critical insights into the relative performance of MLE and Bayesian methods for introgression detection and related statistical applications. In comparative studies of Latent Growth Models (LGMs), MLE demonstrated generally good performance for most standard applications but exhibited frequent convergence failures in complex models with limited data, particularly those with categorical outcomes or numerous latent variables [15] [17]. Bayesian estimation with non-informative priors typically produced parameter estimates similar to MLE when models successfully converged, but offered superior convergence rates for challenging model configurations [15]. The table below summarizes performance comparisons from multiple simulation studies:

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Estimation Methods

| Performance Metric | Maximum Likelihood | Bayesian Estimation |

|---|---|---|

| Convergence Rate | Lower for complex models with limited data | Higher, especially with informative priors |

| Bias | Can be substantial with small samples | Reduced with appropriate priors |

| Computational Speed | Generally faster | Slower due to MCMC/sampling requirements |

| Uncertainty Quantification | Limited (asymptotic approximations) | Comprehensive (full posterior distributions) |

| Small Sample Performance | Often problematic | More robust with carefully chosen priors |

| Model Comparison | Likelihood ratio tests with p-values | Bayes factors with more direct evidence measures |

In specific applications to response time modeling, hierarchical Bayesian methods demonstrated superior parameter recovery compared to classical MLE approaches, particularly reducing variability in parameter estimates across individuals [18]. This "shrinkage" effect occurs because hierarchical Bayesian models borrow information across units, constraining extreme estimates that might occur when analyzing each unit independently [18].

Quantitative Comparisons in Genomic Applications

Genomic introgression studies present particular challenges for statistical estimation, often involving complex demographic histories and selection regimes. The D-statistic, a widely used MLE-based method, is known to be biased as it does not vary linearly with the fraction of introgression and tends to overestimate the number of introgressed regions, particularly in areas with reduced heterozygosity [13]. Simulation studies comparing the Bayesian df-BF method with traditional approaches demonstrated improved performance in quantifying introgression levels, particularly for smaller genomic regions [13]. The Bayesian framework naturally accounts for the number of variant sites within genomic regions, reducing false positives that can occur with traditional ABBA-BABA methods in low-diversity regions [13].

For convergence behavior, studies of latent growth models found that ML estimation failed to converge in 0.6% of models with continuous outcomes, but this rate increased substantially to 18.1% for models with binary outcomes, particularly with smaller sample sizes (N=100) and fewer time points (T=4) [15]. Bayesian estimation with diffuse priors dramatically improved convergence rates to nearly 100% across all conditions, though with some increase in computation time [15]. This demonstrates the practical advantage of Bayesian methods for complex models where MLE struggles with convergence.

Research Implementation Toolkit

Essential Software and Computational Tools

Implementing MLE and Bayesian methods for introgression research requires specialized software tools. The table below summarizes key resources:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Introgression Analysis

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Methodology |

|---|---|---|

| PopGenome R Package | Implements df-BF and related statistics | Bayesian estimation with conjugate priors |

| stdpopsim | Simulation framework for population genomics | Forward-time simulations with selection |

| SLiM | Forward-time population genetics simulator | Generate training data for machine learning approaches |

| genomatnn | Convolutional Neural Network for AI detection | Deep learning classification |

| Stan | Probabilistic programming language | Flexible Bayesian modeling with MCMC sampling |

| PyMC3 | Probabilistic programming framework | Bayesian model specification and estimation |

The PopGenome R package provides specific implementation of the Bayesian df-BF method, enabling researchers to quantify introgression parameters while accounting for uncertainty through Bayes Factors [13]. For simulation-based approaches, stdpopsim offers a standardized framework for generating genomic data under various evolutionary scenarios, while SLiM implements more complex forward-time simulations with selection [16]. The genomatnn package implements the CNN approach for detecting adaptive introgression, offering an alternative to traditional statistical methods [16].

Practical Implementation Considerations

Computational efficiency remains a significant practical consideration when choosing between statistical paradigms. MLE approaches are generally faster and less resource-intensive, making them suitable for initial exploratory analyses or applications to very large genomic datasets [14]. Bayesian methods, particularly those relying on MCMC sampling, demand greater computational resources but provide more comprehensive uncertainty quantification [15] [14]. The development of conjugate prior formulations for introgression statistics represents an important advancement, as it enables Bayesian inference without computationally intensive MCMC iterations [13].

Prior specification presents both a challenge and opportunity in Bayesian applications. For introgression studies, priors might incorporate information from previous phylogenetic analyses, known evolutionary constraints, or demographic history estimates [13]. With weakly informative or diffuse priors, Bayesian estimates typically resemble MLE results, but as priors become more informative, they exert greater influence on posterior estimates, particularly in data-limited situations [15]. This is especially relevant for studies of rare evolutionary events or non-model organisms where genomic data may be limited.

Diagram 2: Method Selection Decision Framework

The comparison between Maximum Likelihood and Bayesian estimation methods for introgression detection reveals a complex trade-off between computational efficiency, statistical properties, and practical implementation. MLE approaches offer computational advantages and well-established theoretical foundations, making them suitable for initial screening analyses and applications where computational resources are limited [14]. However, they struggle with complex models, small sample sizes, and provide limited uncertainty quantification [15]. Bayesian methods provide more comprehensive uncertainty characterization, naturally incorporate prior knowledge, and demonstrate superior convergence behavior for complex models, but at the cost of increased computational demands [15] [14].

For research practice, the choice between paradigms should be guided by specific research contexts. MLE remains appropriate for standard introgression screening in well-characterized systems with ample data [13]. Bayesian approaches are particularly valuable for complex evolutionary scenarios, small datasets, and when incorporating prior information from related studies [13] [15]. Emerging hybrid approaches, such as Bayesian methods with conjugate priors that eliminate MCMC requirements, offer promising directions for future methodology development [13]. Similarly, machine learning techniques like CNNs provide complementary approaches that can identify complex genomic patterns without explicit analytical models [16].

As genomic datasets continue growing in size and complexity, the integration of both philosophical perspectives—leveraging the computational efficiency of MLE where appropriate while employing Bayesian methods for robust uncertainty quantification—will likely provide the most productive path forward for introgression research. The development of more efficient computational algorithms and specialized software tools will further blur the practical distinctions between these paradigms, allowing researchers to select methods based on statistical rather than computational considerations.

In the field of evolutionary biology, a persistent challenge involves accurately reconstructing species histories from genomic data. Two processes—introgression and incomplete lineage sorting (ILS)—create strikingly similar patterns in genetic sequences, often leading to conflicting gene trees that obscure true phylogenetic relationships. Introgression refers to the transfer of genetic material between species through hybridization and repeated backcrossing, while ILS represents the failure of ancestral genetic polymorphisms to coalesce into a single lineage during speciation events. The distinction between these processes is not merely academic; it has profound implications for understanding speciation mechanisms, adaptive evolution, and accurately interpreting genomic landscapes across diverse taxa.

This guide examines the fundamental differences between introgression and ILS, with a specific focus on comparing two powerful statistical frameworks for their detection: maximum likelihood and Bayesian methodologies. As genomic datasets expand across diverse taxa, understanding the strengths and limitations of these approaches becomes increasingly critical for researchers investigating evolutionary histories.

Defining the Processes and Their Evolutionary Significance

Introgression, or hybrid introgression, occurs when genetic material moves from one species into the gene pool of another through repeated backcrossing of hybrids with parental species [10]. This process can introduce beneficial alleles that facilitate rapid adaptation to changing environments [19]. For example, studies in Populus trees have demonstrated that introgression of genetic markers from low-elevation Populus fremontii into high-elevation Populus angustifolia is associated with significantly increased survival in warmer, drier conditions [19].

Incomplete lineage sorting (ILS) arises when ancestral genetic polymorphisms persist through multiple speciation events, causing closely related species to share alleles not due to recent gene flow, but because of the stochastic nature of gene coalescence in ancestral populations [20]. This phenomenon is particularly common in species with large effective population sizes and short divergence times, where the number of generations since divergence is insufficient for lineages to become reciprocally monophyletic [20].

The table below summarizes the key characteristics that distinguish these two processes:

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Introgression vs. Incomplete Lineage Sorting

| Characteristic | Introgression | Incomplete Lineage Sorting (ILS) |

|---|---|---|

| Underlying Mechanism | Horizontal transfer of genetic material between species via hybridization and backcrossing [10] [19] | Vertical descent with random sorting of ancestral polymorphisms [20] |

| Primary Driver | Secondary contact between previously isolated species; natural selection favoring adaptive alleles [20] [19] | Deep coalescence; insufficient time for ancestral polymorphisms to fix in daughter lineages [20] |

| Expected Genomic Distribution | Localized, heterogeneous patterns; often clustered in genomic regions with reduced barriers to gene flow [6] | Random, homogeneous distribution across the genome [20] |

| Impact on Local Adaptation | Can facilitate rapid adaptation through transfer of beneficial alleles [19] | Generally neutral with respect to adaptation |

| Dependence on Geography | Higher signal in parapatric versus allopatric populations [20] | Uniform signal regardless of geographic distribution [20] |

Methodological Frameworks for Detection

Distinguishing between introgression and ILS requires sophisticated statistical approaches that model evolutionary histories from genomic data. The two primary frameworks—maximum likelihood and Bayesian methods—each offer distinct advantages and limitations.

Maximum Likelihood Approaches

Maximum likelihood (ML) methods estimate parameters by finding the values that maximize the probability of observing the given data. In phylogenetics, ML typically involves evaluating tree topologies and evolutionary models to identify the most likely genealogical history. The D-statistic (ABBA-BABA test) represents a widely used ML-derived approach that detects introgression by testing for excess allele sharing between species [13]. The related ƒ-statistic quantifies the proportion of introgressed ancestry [13].

ML methods are computationally efficient and provide point estimates of parameters. However, they may struggle with complex models and do not naturally incorporate prior knowledge or provide direct measures of uncertainty around parameter estimates.

Bayesian Approaches

Bayesian methods frame parameter estimation as a probability distribution, combining prior knowledge with observed data to generate posterior probabilities. These approaches naturally quantify uncertainty through credible intervals and are particularly effective for comparing complex evolutionary models [13].

Recent advancements include df-BF, a Bayesian model selection approach that builds upon the distance-based df statistic. This method uses conjugate priors to avoid computationally demanding MCMC iterations while providing Bayes Factors to weigh evidence for introgression [13]. Approximate Bayesian Computation (ABC) provides another powerful framework for comparing different speciation scenarios when traditional likelihood calculations are intractable [20].

Table 2: Comparison of Maximum Likelihood and Bayesian Frameworks for Detecting Introgression

| Feature | Maximum Likelihood | Bayesian Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Philosophical Basis | Finds parameter values that maximize probability of observed data | Updates prior beliefs with observed data to produce posterior distributions |

| Uncertainty Quantification | Confidence intervals through resampling methods (e.g., bootstrapping) | Direct probability statements through credible intervals |

| Computational Demand | Generally faster | More computationally intensive, though innovations like conjugate priors reduce this [13] |

| Model Complexity | Limited by tractability of likelihood calculations | Better suited for complex models with multiple parameters |

| Prior Information | Does not incorporate prior knowledge | Explicitly incorporates prior distributions |

| Example Methods | D-statistic, ƒ-statistic, Patterson's D [13] | df-BF [13], Approximate Bayesian Computation (ABC) [20] |

Experimental Protocols and Case Studies

Genomic Analysis in Pine Species

A seminal study on two closely related pine species (Pinus massoniana and Pinus hwangshanensis) demonstrated a protocol for distinguishing introgression from ILS [20]:

Sampling Design: Collected samples from both parapatric (partially overlapping) and allopatric (geographically separated) populations to test for heterogeneous patterns of allele sharing [20].

Molecular Markers: Sequenced 33 independent intron loci across the genome, selecting neutral regions to minimize confounding effects of selection [20].

Population Structure Analysis: Used structure analysis to reveal slightly more admiture in parapatric than allopatric populations, suggesting gene flow [20].

Approximate Bayesian Computation: Compared multiple speciation scenarios (pure isolation, isolation-with-migration, secondary contact) to identify the best-fitting model [20].

Ecological Niche Modeling: Reconstructed historical species distributions to identify potential periods of secondary contact during Pleistocene climate oscillations [20].

This integrated approach determined that secondary contact and introgression, rather than ILS, explained most shared nuclear genomic variation between these pines [20].

Model Selection Using Machine Learning

Recent advances apply supervised machine learning to distinguish speciation histories from introgression. These approaches use features extracted from phylogenomic datasets—such as gene tree topologies and node heights—to classify evolutionary histories with high accuracy [21]. This represents a promising complement to traditional phylogenetic methods for analyzing introgression from genomic data [21].

Visualizing Methodological Approaches

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for distinguishing introgression from incomplete lineage sorting using genomic data:

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Methods and Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Studying Introgression and ILS

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Frameworks | Approximate Bayesian Computation (ABC) [20], df-BF [13], D-statistic [13] | Comparing demographic models; quantifying introgression; detecting excess allele sharing |

| Population Genomic Software | STRUCTURE, ADMIXTURE, IMa3, PhyloNet [21] | Inferring population structure; estimating migration rates; analyzing phylogenetic networks |

| Molecular Markers | Nuclear introns [20], Mitochondrial DNA [22], Chloroplast DNA [20] | Providing biparentally, maternally, and paternally inherited genomic signals |

| Sequencing Technologies | Whole-genome sequencing, Targeted sequence capture | Generating genome-wide data for comprehensive analysis |

| Experimental Validation | Common garden experiments [19], Ecological niche modeling [20] | Testing adaptive consequences; reconstructing historical species distributions |

Distinguishing between introgression and incomplete lineage sorting remains a fundamental challenge in evolutionary biology, with each process leaving complex signatures in genomic data. The choice between maximum likelihood and Bayesian approaches depends on multiple factors, including research questions, dataset characteristics, and computational resources. Maximum likelihood methods offer computational efficiency for initial screening, while Bayesian approaches provide robust uncertainty quantification for model comparison.

As genomic datasets continue to expand across diverse taxa, integrative approaches that combine population genetics, phylogenetics, and ecological modeling will provide the most powerful framework for reconstructing evolutionary histories. Future methodological developments, particularly in machine learning and model integration, promise to further enhance our ability to decipher these complex evolutionary processes.

Fundamental Data Requirements and Inputs for ML and Bayesian Models

Detecting introgression, the transfer of genetic information between species through hybridization, is crucial for understanding evolution and adaptation. Methodologies have evolved from summary statistics to sophisticated model-based approaches, primarily divided into Bayesian frameworks and Machine Learning (ML) techniques. This guide objectively compares these paradigms based on their foundational data requirements, experimental protocols, and performance.

Core Data Requirements for Introgression Models

At their core, both Bayesian and ML methods use genomic sequence data, but they differ significantly in how this data is processed and what additional inputs are required.

Table 1: Fundamental Data Inputs and Model Specifications

| Feature | Bayesian Models (e.g., MSci, df-BF) | Machine Learning Models (e.g., CNNs, IntroUNET) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Input | Multilocus sequence alignments from multiple individuals/populations [23] [13]. | Genotype matrices (often treated as images) from donor, recipient, and outgroup populations [16] [24]. |

| Data Structure | Loosely linked, independent genomic loci to satisfy the coalescent model's assumption of free recombination between loci and no recombination within them [23]. | Fixed-size genomic windows (e.g., 100 kbp), with data from multiple individuals sorted and concatenated [16]. |

| Key Parameters | Speciation/introgression times (τ), population sizes (θ), introgression probabilities (φ or γ) [23]. | Often non-parametric; selection coefficients and timing can be unknown a priori [16]. |

| Prior Knowledge | Requires a predefined model (species tree with introgression events) [23]. | Requires simulated data for training, which itself relies on a defined demographic model [16] [24]. |

| Handling of Uncertainty | Quantified directly through posterior probability distributions [25] [23]. | Addressed via prediction accuracy and confidence scores on test data [24]. |

A key divergence lies in their use of data. Bayesian models like the Multispecies Coalescent with Introgression (MSci) rely on a pre-specified phylogenetic model and use raw sequence alignments to compute likelihoods [23]. Conversely, ML methods such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) often use a derived representation of the data—a genotype matrix—which discards explicit phylogenetic information but captures patterns across many individuals and sites simultaneously [16].

The following workflow outlines the typical data processing and analysis pipelines for these two approaches.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The experimental setup for benchmarking these models typically involves rigorous simulations where the true evolutionary history is known, allowing for accurate performance evaluation.

Protocol for Benchmarking Bayesian Methods

A study evaluating the MSci model in the Bpp program provides a standard protocol for assessing Bayesian performance [23]:

- Data Simulation: Coalescent simulations are run using a known species tree model with one or more predefined introgression events. Parameters like introgression probability (

φ), divergence times (τ), and population sizes (θ) are set. - Inference: The simulated sequence alignments are analyzed using the Bayesian MCMC method. The analysis assumes the correct model topology but estimates the parameters from the data.

- Evaluation: The posterior estimates of parameters (e.g., the mean of the posterior distribution for

φ) are compared to their known true values from the simulation. Statistical properties like bias and accuracy are calculated across hundreds of replicate datasets.

Protocol for Benchmarking Machine Learning Methods

The development of genomatnn, a CNN for detecting adaptive introgression (AI), follows a protocol common to supervised ML approaches [16]:

- Training Data Simulation: A forward-in-time simulator (e.g., SLiM within the stdpopsim framework) is used to generate thousands of genomic regions under two evolutionary scenarios:

- Positive Selection with Introgression (AI): A beneficial allele is introduced into the recipient population via admixture and increases in frequency due to selection.

- Neutral Evolution or Selective Sweeps without Introgression: Data is generated under neutral models or classic selective sweeps.

- Input Preparation: For each simulated region, a genotype matrix is created, incorporating data from the donor, recipient, and an outgroup population. The matrix is formatted as an image-like input.

- Network Training: The CNN is trained on these labeled examples to distinguish between the AI and non-AI scenarios.

- Testing and Validation: The trained model's accuracy, precision, and recall are evaluated on a held-out test set of simulations. It can then be applied to empirical data to identify candidate AI regions.

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Empirical benchmarks using the protocols above reveal distinct performance characteristics and computational trade-offs between the two approaches.

Table 2: Performance Comparison Based on Experimental Benchmarks

| Aspect | Bayesian Models | Machine Learning Models |

|---|---|---|

| Parameter Estimation Accuracy | Accurate estimation of φ, τ, and θ with reliable credible intervals, but requires hundreds to thousands of loci [23]. |

Not designed for direct parameter estimation; excels at classification and pattern recognition [16] [24]. |

| Detection Power | High power to detect introgression when the model is correctly specified [23]. | CNNs can achieve >95% accuracy in distinguishing adaptive introgression from other scenarios, even with unphased data [16]. |

| Spatial Resolution | Infers introgression for pre-defined genomic regions or loci [13] [23]. | Base-pair resolution: IntroUNET can identify which specific alleles in which individuals are introgressed [24]. |

| Computational Demand | Computationally intensive due to MCMC sampling; can be prohibitive for genome-scale data [23] [25]. | High demand is front-loaded to the training phase; application to new data is often very fast [16] [24]. |

| Robustness to Model Misspecification | Performance can degrade with an incorrect model; newer methods like SINGER show improved robustness for genealogical inference [25]. | Performance depends on the diversity of training simulations; can struggle with scenarios not encountered during training. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful application of these models relies on a suite of software tools and genomic resources.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Resources

| Tool/Resource | Function | Relevance to Model Type |

|---|---|---|

| Bpp | Implements the MSci model for Bayesian inference of introgression from sequence alignments [23]. | Bayesian |

| PopGenome (R package) | Contains implementation of the df-BF method, a Bayesian approach for introgression detection and quantification [13]. |

Bayesian |

| SINGER | Infers genome-wide genealogies (ARGs) from hundreds of genomes with quantified uncertainty, useful for detecting archaic introgression [25]. | Bayesian / ARG-based |

| SLiM + stdpopsim | Forward-in-time simulation framework with a selection module; used for generating training data for ML models [16]. | Machine Learning |

| genomatnn | A CNN-based method trained to detect genomic regions evolving under adaptive introgression [16]. | Machine Learning |

| IntroUNET | A deep learning model for semantic segmentation that identifies introgressed alleles in individual genomes at base-pair resolution [24]. | Machine Learning |

| Phased WGS Data | High-quality, phased whole-genome sequencing data from multiple individuals across relevant populations. | Both |

| Reference Genomes | High-quality genome assemblies for the studied species and, if possible, for closely related outgroups. | Both |

A Practical Guide to ML and Bayesian Introgression Methods and Their Implementation

In evolutionary genomics, a frequent challenge arises when gene trees constructed from different genomic regions conflict with each other and with the presumed species tree. This phylogenetic conflict stems primarily from two distinct biological processes: incomplete lineage sorting (ILS), where ancestral genetic polymorphisms persist through successive speciation events, and gene flow (introgression), which occurs when genetic material is transferred between diverging lineages through hybridization [26]. Disentangling these confounding sources of discordance is crucial for reconstructing accurate evolutionary histories and understanding speciation processes.

The statistical frontier for addressing this challenge is dominated by two philosophical approaches: frequentist methods anchored in maximum likelihood estimation and Bayesian methods that incorporate prior knowledge into posterior probability calculations. While Bayesian approaches have gained popularity through their ability to quantify uncertainty and incorporate prior biological knowledge, maximum likelihood methods offer computational advantages and avoid potential biases introduced by prior specification. This comparison guide examines a novel maximum likelihood approach called Aphid that uses approximate likelihoods to achieve an optimal balance of accuracy, speed, and robustness in detecting ancient gene flow [26] [27].

Understanding the Methodological Divide: Maximum Likelihood vs. Bayesian Frameworks

Philosophical Foundations and Computational Approaches

The fundamental distinction between maximum likelihood and Bayesian estimation lies in their treatment of parameters and incorporation of prior knowledge:

Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) seeks to find the parameter values that maximize the likelihood function, which represents the probability of observing the collected data given specific parameter values. MLE produces point estimates of parameters without incorporating prior beliefs, treating parameters as fixed but unknown quantities [11] [28]. In practice, working with the log-likelihood is often more convenient, as it converts products into sums while preserving the location of the maximum [28].

Bayesian Estimation treats parameters as random variables with associated probability distributions. It combines prior knowledge about parameters (the prior distribution) with the observed data (through the likelihood function) to form a posterior distribution that represents updated beliefs about the parameters after considering the evidence [11]. The Bayesian framework utilizes Bayes' Theorem, where the posterior is proportional to the likelihood multiplied by the prior [12].

Practical Implications for Phylogenetic Analysis

In the specific context of phylogenetic conflict analysis, these philosophical differences translate to distinct methodological implementations:

MLE-based approaches like Aphid focus on finding the parameter values (speciation times, ancestral population sizes, and introgression probabilities) that make the observed gene trees most probable. The Aphid algorithm implements an approximate likelihood method that dramatically reduces computational complexity by modeling the distribution of gene genealogies as a mixture of several canonical genealogies where coalescence times are set equal to their expectations [26].

Bayesian approaches for introgression detection, such as those implemented in BPP, compute a posterior distribution over parameter space, allowing researchers to quantify uncertainty in parameter estimates [7]. These methods can incorporate prior biological knowledge but typically require more intensive computation through Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling.

Table 1: Core Differences Between Maximum Likelihood and Bayesian Estimation Frameworks

| Feature | Maximum Likelihood Estimation | Bayesian Estimation |

|---|---|---|

| Parameter Treatment | Fixed, unknown quantities | Random variables with distributions |

| Prior Information | Not incorporated | Explicitly incorporated via prior distributions |

| Output | Point estimates (e.g., $\hat{\theta}$) | Posterior probability distributions |

| Computational Demand | Generally lower (optimization) | Generally higher (MCMC sampling) |

| Uncertainty Quantification | Confidence intervals via asymptotic theory | Credible intervals directly from posterior |

| Key Strength | Computational efficiency, objectivity | Uncertainty quantification, prior incorporation |

The Aphid Algorithm: An Approximate Maximum Likelihood Solution

Core Theoretical Innovation

The Aphid algorithm introduces a computationally efficient approximate likelihood method to quantify the relative contributions of gene flow and incomplete lineage sorting to phylogenetic conflict in three-species systems [26] [27]. Its key theoretical insight leverages the observation that gene trees affected by gene flow tend to have shorter branches, while those affected by incomplete lineage sorting tend to have longer branches than the average gene tree [27]. This branch length signal provides a statistical fingerprint for distinguishing between the two processes.

Rather than computing the full likelihood across all possible gene trees—a computationally prohibitive task—Aphid implements a mixture model approach that considers a limited set of characteristic gene tree "scenarios" with fixed branch lengths set to their expected values [26]. This simplification dramatically reduces computational complexity while maintaining reasonable statistical robustness. The method further accounts for among-loci variation in mutation rate and gene flow timing, returning estimates of speciation times, ancestral effective population sizes, and a posterior assessment of the contributions of gene flow and ILS to observed phylogenetic conflict [27].

Implementation Workflow

The Aphid methodology follows a structured analytical pipeline that transforms raw genomic data into interpretable parameter estimates:

Aphid Algorithm Workflow

The workflow begins with standard phylogenetic data preparation, including identification of orthologous loci across the studied species and outgroup. For each locus, Aphid estimates gene trees, then models their distribution as a mixture of canonical scenarios with expected branch lengths. The approximate likelihood function is maximized to obtain parameter estimates, finally yielding quantitative assessments of the relative roles of ILS and gene flow in generating phylogenetic discordance.

Performance Comparison: Aphid vs. Bayesian Methods

Detection Capabilities and Limitations

Empirical evaluations and simulation studies reveal distinctive performance characteristics for Aphid compared to Bayesian alternatives:

Gene Flow Detection Power: Aphid demonstrates particular strength in detecting symmetric gene flow patterns that may be missed by popular heuristic methods like HYDE or the D-statistic (ABBA-BABA tests). In analyses of African ape genomes, Aphid detected evidence that both ancestral humans and chimpanzees interbred with ancestral gorillas at approximately equal rates—a finding that challenged previous interpretations [26]. Bayesian methods like BPP also detect such symmetric gene flow but typically require substantially more computational resources [7].

Sister Lineage Sensitivity: Unlike heuristic methods such as HYDE that struggle to detect gene flow between sister lineages, Aphid can identify such introgression events. However, Bayesian methods maintain an advantage in this domain, having been specifically designed to detect gene flow across diverse phylogenetic relationships [7].

Model Assumption Robustness: Aphid maintains reasonable robustness when its simplifying assumptions are violated, though performance degrades when the fraction of discordant phylogenetic trees exceeds 50-55% [26]. Bayesian methods similarly depend on model assumptions but typically provide better uncertainty quantification when models are misspecified.

Table 2: Performance Comparison in Detecting Ancient Gene Flow

| Performance Metric | Aphid (MLE) | Bayesian BPP | Heuristic HYDE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetric Gene Flow Detection | Excellent | Excellent | Poor |

| Sister Lineage Introgression | Good | Excellent | Poor |

| Computational Speed | Fast | Slow | Fast |

| Model Robustness | Moderate | Moderate-High | Low |

| Uncertainty Quantification | Limited | Comprehensive | Limited |

| Bidirectional Gene Flow | Excellent | Good | Poor |

Parameter Estimation Accuracy

Comparative analyses reveal how methodological choices impact substantive conclusions in evolutionary genomics:

Speciation Time Estimates: In the human-chimpanzee-gorilla clade, Aphid analysis suggests older speciation times and smaller ancestral effective population sizes compared to methods that assume no gene flow [27]. This correction aligns with paleontological evidence and addresses previous discrepancies between genomic and fossil-based divergence estimates.

Ancral Effective Population Size: By properly accounting for gene flow, Aphid produces reduced estimates of ancestral effective population sizes in African apes, potentially resolving conflicts between genetic and anthropological evidence [26].

Introgression Probability Quantification: Bayesian methods like BPP can detect introgression probabilities reaching 63% in chipmunk genomes, highlighting their sensitivity to ancient gene flow events [7]. Aphid provides similar quantification but with substantially reduced computational overhead.

Experimental Protocols and Data Requirements

Standard Implementation Framework

Implementing Aphid for phylogenetic conflict analysis requires careful attention to data preparation and analytical steps:

Data Collection: Genome-scale data from three focal species and at least one outgroup. The method can utilize both coding and non-coding regions, with loci chosen to represent independent genealogical histories (typically requiring sufficient physical separation to ensure independence) [26].

Gene Tree Estimation: For each locus, infer gene trees using standard phylogenetic methods. Aphid is relatively robust to gene tree estimation error but benefits from high-quality alignments and appropriate evolutionary models [27].

Algorithm Configuration: Set initial parameter bounds based on biological priors (e.g., divergence time constraints from fossil evidence). The implementation uses numerical optimization to maximize the approximate likelihood function [26].

Convergence Assessment: Although less computationally intensive than Bayesian methods, Aphid still requires verification of convergence through multiple random starting points in parameter space [27].

Model Validation: Compare results under different constraint scenarios and validate findings with complementary methods (e.g., D-statistics or phylogenetic network approaches) [7].

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Phylogenetic Conflict Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aphid | Maximum likelihood estimation | Quantifying ILS vs. gene flow contributions | Standalone implementation |

| BPP | Bayesian MCMC sampler | Species tree estimation with introgression | Standalone package |

| HYDE | Heuristic summary method | Detecting gene flow via site patterns | Part of Dsuite package |

| D-statistics | Heuristic test | Detecting gene flow in species quartets | Implemented in multiple packages |

| Gene tree estimation software (e.g., RAxML, IQ-TREE) | Phylogenetic inference | Estimating individual gene trees | Standalone packages |

The choice between maximum likelihood (as implemented in Aphid) and Bayesian approaches for detecting phylogenetic conflict depends on multiple research-specific factors:

For rapid screening of genome-scale datasets where computational efficiency is paramount, Aphid provides an excellent balance of speed and accuracy, particularly for detecting symmetric gene flow patterns [26].

When comprehensive uncertainty quantification is required or prior biological knowledge should be formally incorporated, Bayesian methods remain preferable despite their computational demands [7].

In scenarios with suspected complex introgression histories involving multiple sister lineages, Bayesian approaches currently outperform approximate likelihood methods, though Aphid represents a significant advance over simpler heuristic methods [7].

For non-specialists seeking an accessible entry point to phylogenetic conflict analysis, Aphid's simpler implementation and faster runtime lower barriers to adoption while maintaining biological accuracy [27].

The development of Aphid exemplifies a growing trend in evolutionary genomics toward methods that balance statistical rigor with computational practicality. As genomic datasets continue expanding in both size and taxonomic scope, such approximate likelihood approaches will play an increasingly vital role in elucidating the complex evolutionary histories that shape biodiversity.

In the field of evolutionary biology, genomic data has revealed that cross-species gene flow, or introgression, is a widespread phenomenon. Accurately detecting and quantifying this introgression is crucial for understanding species relationships and evolutionary history. The methodological landscape for this task is broadly divided into two philosophical approaches: maximum likelihood (MLE) and Bayesian inference. This guide focuses on the Bayesian software BPP and its implementation of the Multispecies Coalescent with Introgression (MSci) model, objectively comparing its performance and capabilities with other leading alternatives [29].

The core difference between the two approaches lies in how they handle parameters. Maximum likelihood estimation seeks a single set of parameter values that are most likely to have produced the observed data, treating the parameters as fixed unknown constants [11] [12]. In contrast, Bayesian estimation treats parameters as random variables with probability distributions. It combines prior knowledge with the observed data to produce a posterior distribution, which fully characterizes the uncertainty in the parameter estimates [11] [30] [12]. For complex models like the MSci, which are prone to identifiability issues, the Bayesian framework within BPP offers a principled way to quantify this uncertainty [29].

Theoretical Framework: The MSci Model and Bayesian Foundations

The Multispecies Coalescent with Introgression (MSci)

The MSci model extends the standard multispecies coalescent to incorporate historical introgression events [29]. It is designed to analyze multilocus sequence data from multiple closely related species. Key parameters it estimates include [29]:

- Species divergence times (τ): The times at which species split from a common ancestor.

- Population sizes (θ): The effective population sizes for modern and ancestral species.

- Introgression probabilities (φ): The probability that a lineage from one species introgresses into another at a given hybridization event.

In the MSci model, a species network includes both speciation nodes (vertical descent) and hybridization nodes (lateral gene flow). When tracing a genealogy backward in time and reaching a hybridization node, a lineage can take one of two parental paths with probabilities defined by the introgression probability parameter, φ [29].

Bayesian Implementation in BPP

BPP implements a full-likelihood Bayesian approach for the MSci model. Its workflow can be summarized as follows:

The core computational engine of BPP is Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC), which generates samples from the posterior distribution of parameters and genealogies [30]. A significant advantage of this full-likelihood method is its ability to naturally quantify uncertainty for all estimated parameters, which is critical for assessing the support for inferred introgression events [25] [29].

Performance and Accuracy Comparison

The following tables summarize benchmark results for BPP and other genomic analysis tools, based on simulations and real-data analyses.

Table 1: Benchmarking performance of BPP and other genomic analysis tools on simulated data (50 haplotypes). Adapted from SINGER (2025) and Flouri et al. (2022). [31] [25]

| Method | Inference Paradigm | Coalescence Time Accuracy (Rank) | Tree Topology Accuracy (Triplet Distance) | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPP (with relaxed clock) | Bayesian (Full-likelihood) | High (1st) | Lowest triplet distance | Full parameter estimation (τ, θ, φ); uncertainty quantification [31] [29] | Computationally intensive; mixing issues with relaxed clock [31] |

| SINGER | Bayesian (Full-likelihood) | Highest (1st) | Lowest triplet distance | Accurate, robust to model misspecification, good uncertainty quantification [25] | --- |

| ARGweaver | Bayesian (Full-likelihood) | Medium (3rd) | Higher than SINGER/BPP | Posterior sampling of ARGs [25] | Tends to underestimate coalescence times; less scalable [25] |

| Relate | Two-step (Summary) | Medium (2nd) | Medium | Scalable to large sample sizes [25] | Does not provide full posterior; relies on heuristic approximations [31] [25] |

| tsinfer + tsdate | Two-step (Summary) | Low (4th) | Highest triplet distance | Computationally efficient [25] | Overestimates coalescence times; less accurate for ancient times [25] |

Table 2: General comparison of software for introgression detection and species tree estimation. [30] [32] [29]

| Software | Primary Function | Method | Key Features | Model Robustness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPP | Species tree estimation, delimitation, & introgression | Bayesian (MCMC) | Implements MSC, MSci, MSC-M; relaxed clocks; GTR+Γ model [31] [32] [29] | Improved with re-scaling, but assumes panmictic populations [25] |

| SINGER | Ancestral Recombination Graph (ARG) inference | Bayesian (MCMC) | Samples from ARG posterior; robust to model misspecification [25] | High robustness due to ARG re-scaling [25] |

| MrBayes | Phylogenetic inference | Bayesian (MCMC) | Large number of nucleotide, amino acid, and morphological models [30] | Dependent on model specification [30] |

| BEAST | Divergence time estimation, phylogeography | Bayesian (MCMC) | Vast number of models for molecular dating and species tree estimation [30] | Dependent on model and prior specification [30] |

| Summary Methods (e.g., ASTRAL) | Species tree estimation | Maximum Likelihood / Heuristic | Computationally efficient; uses gene tree topologies [31] | Can be misled by gene tree estimation error [31] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Full-Likelihood vs. Two-Step Analysis

A critical distinction in methodology is between full-likelihood and two-step (summary) approaches.

The full-likelihood approach used by BPP and SINGER is considered statistically more rigorous as it propagates uncertainty from the sequence data all the way to the species-level parameters [31] [29]. In contrast, two-step methods treat inferred gene trees as observed data, which can introduce biases because the uncertainty in gene tree estimation is not fully accounted for in the subsequent species tree analysis [31].

Handling Model Unidentifiability

A key challenge in MSci model inference is unidentifiability, where different parameter combinations can produce the same likelihood score [29]. For example, in a Bidirectional Introgression (BDI) model, a set of parameters Θ and its "mirror" set Θ' can have identical likelihoods, making them indistinguishable by the data alone [29].

BPP's Bayesian framework addresses this by using prior distributions to help break the symmetry between unidentifiable modes [29]. Furthermore, novel MCMC sampling algorithms have been developed to identify and process these mirror modes in the posterior distribution, allowing for correct interpretation of introgression parameters [29]. Heuristic methods based on gene tree topologies are often more susceptible to such identifiability issues compared to full-likelihood methods [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key software and data resources for Bayesian introgression analysis. [30] [25] [32]

| Tool / Resource | Function | Role in the Analysis Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| BPP Software Suite | Bayesian phylogenetic analysis | Primary engine for MCMC sampling under the MSC, MSci, and MSC-M models [32]. |

| Sequence Alignments | Input Data | Phased, aligned genomic sequences (e.g., from multiple individuals/species). Must represent orthologs [30]. |

| jModelTest / PartitionFinder | Substitution Model Selection | Determines the best-fitting nucleotide substitution model for the data (e.g., GTR+Γ), which can be specified in BPP [30]. |

| Tracer | MCMC Diagnostics | Analyzes MCMC output from BPP/BEAST to assess convergence, effective sample sizes (ESS), and summarize posterior distributions [30]. |

| msprime | Data Simulation | Simulates genomic sequences under coalescent models to generate benchmark data for testing methods and validating results [25]. |

| AWTY | MCMC Diagnostics (Phylogenetics) | A package specifically for diagnosing MCMC convergence in Bayesian phylogenetic analyses [30]. |

BPP stands as a powerful, full-likelihood Bayesian tool for researchers requiring detailed inference of species divergence times, population sizes, and introgression probabilities. Its main advantage over many alternatives is its comprehensive uncertainty quantification for all parameters, which is paramount when dealing with the inherent complexities of genomic data and the identifiability challenges of MSci models [33] [29].

The choice between BPP and other tools ultimately depends on the research question and constraints. For large-scale analyses where computational efficiency is paramount, summary methods like Relate may be necessary. However, for robust parameter estimation and hypothesis testing concerning specific introgression events, the Bayesian framework and full-likelihood approach implemented in BPP and newer tools like SINGER provide a more statistically sound and reliable solution [25] [33]. As the field moves forward, the development of more scalable and robust Bayesian methods will continue to bridge the gap between statistical rigor and computational feasibility.

PhyloNet-HMM represents a significant methodological advancement for detecting introgression in genomic studies. By integrating phylogenetic networks with hidden Markov models (HMMs), it provides a powerful Bayesian framework to distinguish true introgression signals from confounding factors like incomplete lineage sorting (ILS). This guide objectively compares its performance against other leading methods and details the experimental evidence supporting these comparisons.

PhyloNet-HMM was specifically designed to address a critical challenge in evolutionary genomics: teasing apart genuine introgression (the transfer of genetic material between species) from spurious signals caused by ILS [34] [5]. ILS occurs when ancestral polymorphisms persist through multiple speciation events, creating genealogical discordance that can mimic the patterns left by hybridization [35].

The core innovation of PhyloNet-HMM is its combined statistical architecture:

- Phylogenetic Networks: Model the complex, non-tree-like evolutionary history of species, explicitly accounting for hybridization and introgression events [34] [5].

- Hidden Markov Models (HMMs): Capture the dependencies within genomes, modeling how the local genealogical history changes along the chromosome due to recombination [34]. This allows the method to "walk" along the genome and infer the evolutionary history of each segment.

This integration allows for systematic, genome-wide analysis of aligned sequence data from multiple individuals or species to pinpoint regions of introgressive descent [5] [36]. Alternative methods fall into several categories, which are compared in the table below.

Table 1: Comparison of Introgression Detection Methodologies

| Method Category | Representative Tools | Core Methodology | Key Assumptions/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bayesian Network-HMM | PhyloNet-HMM | Integrates phylogenetic networks with HMMs for genome scanning [34] [5]. | Accounts for ILS and within-genome dependencies. |

| Bayesian MSci Sampling | BPP | Bayesian implementation of the multispecies coalescent with introgression (MSci) model [7]. | Uses multilocus sequence alignments directly; powerful for testing specific species trees with introgression. |

| Pseudo-likelihood Network Inference | SNaQ, MPL | Uses quartet concordance or other approximations to infer networks from gene trees [35]. | Less computationally intensive than full-likelihood methods, but an approximative approach. |

| Heuristic/Site-Pattern | HYDE, D-statistic | Analyzes site-pattern counts (e.g., ABBA-BABA) summarized across the genome [7]. | Low power for detecting gene flow between sister lineages; HYDE assumes a specific hybrid-speciation model [7]. |

| Concatenation-Based | Neighbor-Net, SplitsNet | Infers a single phylogenetic network from a concatenated sequence alignment [35]. | Does not account for locus-specific genealogical incongruence due to ILS or introgression [35]. |

The following diagram illustrates the core logical workflow of the PhyloNet-HMM framework for detecting introgressed genomic regions.

Performance Benchmarking and Experimental Data

Empirical and simulation studies have consistently demonstrated the high accuracy and robustness of PhyloNet-HMM and other probabilistic frameworks compared to heuristic approaches.

Empirical Validation with Mouse Genomes

In a key study, PhyloNet-HMM was applied to genomic variation data from chromosome 7 of house mice (Mus musculus domesticus) [34] [5].

- Experimental Protocol: The method was run on aligned genome sequences using a predefined set of potential parental species trees. The HMM was used to compute the posterior probability for each genomic site belonging to each possible parental tree [5].

- Results: The analysis successfully recovered a known adaptive introgression event involving the Vkorc1 gene, which confers resistance to rodent poison [34] [5]. Furthermore, it revealed that approximately 9% of sites on chromosome 7 (covering about 13 Mbp and over 300 genes) were of introgressive origin, a finding that extended beyond the previously known region [34]. When applied to a negative control dataset where no introgression was expected, the model correctly detected no introgression, confirming its specificity [34] [5].

Power Comparison: Bayesian vs. Heuristic Methods

A re-analysis of nuclear genomic data from chipmunks highlighted the superior power of Bayesian methods over heuristic ones. A prior study using the heuristic method HYDE had found no significant evidence for nuclear introgression, despite known mitochondrial introgression [7].