Molecular Dynamics Explained: From Basic Principles to Advanced Applications in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Molecular Dynamics Explained: From Basic Principles to Advanced Applications in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of MD, including integration algorithms, force fields, and thermodynamic ensembles. The guide then explores advanced methodological approaches and their concrete applications in pharmaceutical development, such as binding free energy calculations and the Relaxed Complex Method. It offers practical troubleshooting advice for common simulation errors and optimization techniques. Finally, it discusses validation protocols and comparative analyses of MD with other structural modeling techniques, highlighting its critical role in modern, dynamics-based drug discovery.

The Core Engine: Understanding the Foundational Principles of Molecular Dynamics

Molecular Dynamics (MD) is a computational technique that simulates the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time. By solving Newton's equations of motion for a system of interacting particles, MD provides a dynamic view of molecular processes, bridging the gap between static structural information and dynamic functional behavior. This technical guide examines the core algorithms that form the foundation of MD simulations, with particular emphasis on numerical integration techniques and their practical implementation. Within the broader context of molecular dynamics research, understanding these basic principles is crucial for researchers aiming to apply MD simulations to challenging domains such as drug development, where atomic-level insights can accelerate the design of novel therapeutics [1].

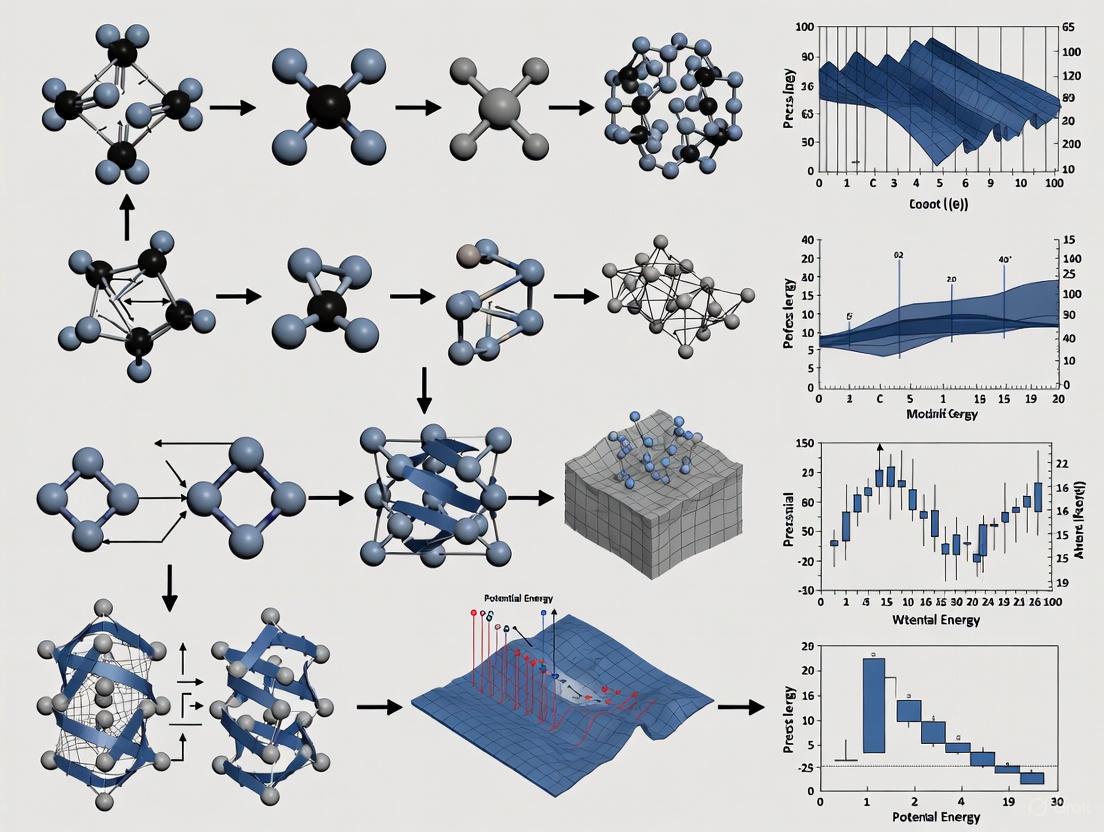

The Fundamental MD Algorithm

At its core, the Molecular Dynamics algorithm is an iterative process that calculates the trajectories of particles by numerically integrating Newton's equations of motion. The global MD algorithm follows a well-defined sequence of operations that repeats for the required number of time steps [2].

Algorithmic Workflow

The standard MD procedure can be decomposed into four primary stages:

- Input initial conditions: The simulation requires initial particle positions ((\mathbf{r})), velocities ((\mathbf{v})), and the potential interaction function ((V)) that describes how atoms interact [2].

- Compute forces: For each atom, the force (\mathbf{F}i) is computed as the negative gradient of the potential energy function: (\mathbf{F}i = - \frac{\partial V}{\partial \mathbf{r}_i}). This involves calculating non-bonded interactions between atom pairs plus bonded interactions (which may depend on 1, 2, 3, or 4 atoms), along with any restraining or external forces [2].

- Update configuration: The positions and velocities of all atoms are updated by numerically solving Newton's equations of motion: (\frac{d^2\mathbf{r}i}{dt^2} = \frac{\mathbf{F}i}{mi}) or equivalently (\frac{d\mathbf{r}i}{dt} = \mathbf{v}i; \frac{d\mathbf{v}i}{dt} = \frac{\mathbf{F}i}{mi}) [2].

- Output step: If required, positions, velocities, energies, temperature, pressure, and other observables are written to output files for subsequent analysis [2].

This sequence repeats for thousands to millions of time steps to simulate meaningful biological time scales. The following diagram illustrates this iterative workflow:

Initialization Phase

Before the main simulation loop begins, proper initialization is crucial for physical realism and numerical stability.

Initial Conditions

The initialization phase requires:

- System topology and force field: The molecular topology and force field description define the potential energy function (V) and remain static throughout the simulation [2].

- Coordinates and velocities: Initial particle positions and velocities must be specified. For velocities, if not available, they can be generated from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution at a given temperature (T): (p(vi) = \sqrt{\frac{mi}{2 \pi kT}}\exp\left(-\frac{mi vi^2}{2kT}\right)), where (k) is Boltzmann's constant [2].

- Periodic boundary conditions: The simulation box is defined by three basis vectors ((\mathbf{b}1, \mathbf{b}2, \mathbf{b}_3)) that determine its size and shape [2].

Center-of-Mass Motion

The center-of-mass velocity is typically set to zero at every step to prevent spurious overall motion of the system. In practice, numerical integration algorithms introduce slow drift in the center-of-mass velocity, particularly when temperature coupling is used, which can lead to misinterpretation of temperature in long simulations if not properly controlled [2].

Numerical Integration Methods

Numerical integration of Newton's equations of motion represents the mathematical core of MD simulations. Since analytical solutions are impossible for complex many-body systems, finite difference methods are employed to propagate the system forward in time.

The Leap-Frog Integrator

The leap-frog algorithm is the default integrator in many MD packages, including GROMACS. It offers numerical stability and computational efficiency for a wide range of systems [2].

The algorithm derives its name from the half-step offset between velocity and position updates:

- Calculate velocities at (t + \frac{1}{2}\Delta t): (\mathbf{v}i\left(t + \frac{1}{2}\Delta t\right) = \mathbf{v}i\left(t - \frac{1}{2}\Delta t\right) + \frac{\mathbf{F}i(t)}{mi}\Delta t)

- Calculate positions at (t + \Delta t): (\mathbf{r}i(t + \Delta t) = \mathbf{r}i(t) + \mathbf{v}_i\left(t + \frac{1}{2}\Delta t\right)\Delta t)

This formulation provides better numerical stability than simpler Euler methods while requiring only one force evaluation per step. The leap-frog scheme is distinguished among the Störmer-Verlet-leapfrog group of integrators both in terms of truncation error order and conservation of total energy [3].

Time Step Selection

The choice of integration time step ((\Delta t)) represents a critical balance between numerical stability and computational efficiency. Too large a step size causes instability, while too small a step wastes computational resources.

Table 1: Comparison of Common Numerical Integrators in MD

| Integrator | Order of Error | Stability | Computational Cost | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leap-Frog | (\mathcal{O}(\Delta t^2)) | High | Low | Default in GROMACS; time-reversible [2] [3] |

| Verlet | (\mathcal{O}(\Delta t^2)) | High | Low | Direct position update; no explicit velocities [3] |

| Velocity Verlet | (\mathcal{O}(\Delta t^2)) | High | Medium | Explicit position and velocity updates [3] |

| Beeman | (\mathcal{O}(\Delta t^2)) | High | Medium | Better energy conservation [3] |

For biomolecular systems with fast bond vibrations, time steps are typically limited to 1-2 fs. However, techniques such as hydrogen mass repartitioning can enable longer time steps (up to 4 fs) by allowing the redistribution of mass within molecules, effectively slowing down the highest frequency vibrations [3].

Force Calculation and Neighbor Searching

The computation of forces represents the most computationally intensive part of an MD simulation, typically consuming 80-90% of the total calculation time.

Force Field Components

The force on each atom is derived from the potential energy function, which is composed of multiple terms:

(\mathbf{F}i = -\nablai V = -\nablai \left(V{\text{bonded}} + V_{\text{non-bonded}}\right))

Where the potential energy is typically divided into:

- Bonded interactions: Depends on fixed connectivity and includes bond stretching, angle bending, and dihedral torsions

- Non-bonded interactions: Computed between all atom pairs (except those excluded by connectivity) and includes van der Waals and electrostatic terms [4]

Force fields provide the specific functional forms and parameters for these interactions, with different force fields (CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS) optimized for specific classes of molecules and simulation conditions [4].

Neighbor Search Algorithms

Since computing all pairwise interactions in a system of N atoms would require (\mathcal{O}(N^2)) operations, efficient algorithms are essential for large systems. MD packages employ neighbor lists to track potentially interacting atom pairs, significantly reducing computational burden.

Verlet List Method

The Verlet list approach constructs a list of all atom pairs within a cut-off radius ((Rc)) plus a buffer region ((rb)). This list is updated periodically (everynstlist steps) rather than at every time step [2].

The pair list cut-off is set to: (r\ell = rc + r_b)

Where (rc) is the interaction cut-off and (rb) is the buffer size. This buffering ensures that as particles move between list updates, forces between nearly all particles within the cut-off distance are still calculated [2].

Cluster-Based Optimization

Modern MD implementations use spatial clustering of particles (typically 4 or 8 particles per cluster) to optimize neighbor searching. The cluster-pair search is significantly faster than particle-pair searching because multiple particle pairs are processed simultaneously. This approach maps efficiently to SIMD (Single Instruction, Multiple Data) units on modern hardware [2].

Energy Drift and Buffer Optimization

The finite update frequency of neighbor lists introduces a small energy drift due to particles moving from outside the pair-list cut-off to inside the interaction cut-off during the list's lifetime. The energy error can be estimated from atomic displacements and the potential shape at cut-off [2].

For canonical (NVT) ensembles, the displacement distribution along one dimension for a freely moving particle with mass (m) over time (t) at temperature (T) is a Gaussian (G(x)) of zero mean and variance (\sigma^2 = t^2 kB T/m). For the distance between two particles, the variance becomes (\sigma^2 = \sigma{12}^2 = t^2 kB T(1/m1+1/m_2)) [2].

Table 2: Neighbor Search Parameters and Their Impact on Performance

| Parameter | Typical Value | Effect on Performance | Effect on Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pair-list cut-off ((r_\ell)) | (rc + rb) | Larger values increase computation | Insufficient buffer causes energy drift |

Update frequency (nstlist) |

10-20 steps | Higher values reduce overhead | Too high misses interactions |

| Buffer size ((r_b)) | 0.1-0.2 nm | Larger values require larger lists | Smaller values increase energy drift |

| Cluster size | 4 or 8 atoms | Larger clusters reduce search time | No direct effect on accuracy |

Advanced implementations use automatic buffer tuning based on target energy drift tolerance (default in GROMACS is 0.005 kJ/mol/ps per particle) and dynamic pair-list pruning to remove non-interacting pairs between full updates [2].

Practical Implementation and Research Applications

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential MD Components

Successful MD simulations require careful preparation and the right computational tools. The following table outlines key components in the MD researcher's toolkit:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Molecular Dynamics

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simulation Software | GROMACS, NAMD, AMBER, CHARMM | Performs MD calculations with optimized algorithms | Biomolecular simulations, materials science [2] [5] |

| Force Fields | CHARMM36, AMBER, GROMOS, OPLS-AA | Defines potential energy functions and parameters | System-specific parameterization [5] [4] |

| System Building | CHARMM-GUI, BIOVIA Discovery Studio | Prepares initial structures and simulation boxes | Membrane proteins, complex assemblies [6] [5] |

| Enhanced Sampling | GaMD, Steered MD, FEP | Accelerates rare events and free energy calculations | Drug binding, conformational changes [5] |

Applications in Drug Development

MD simulations have become indispensable in modern drug development, particularly in optimizing drug delivery systems for cancer therapy. They provide atomic-level insights into drug-carrier interactions, encapsulation stability, and release mechanisms that are difficult to obtain experimentally [1].

Case studies involving anticancer drugs like Doxorubicin (DOX), Gemcitabine (GEM), and Paclitaxel (PTX) demonstrate how MD simulations can improve drug solubility and optimize controlled release mechanisms. Simulations help researchers understand molecular interactions in delivery systems including functionalized carbon nanotubes (FCNTs), chitosan-based nanoparticles, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), and human serum albumin (HSA) [1].

Workflow Integration

A typical MD-based research project follows an integrated workflow that combines simulation with experimental validation. The diagram below illustrates this iterative process in the context of drug delivery system optimization:

The basic MD algorithm, grounded in Newton's equations of motion and numerically integrated through schemes like the leap-frog method, provides a powerful framework for investigating molecular systems at atomic resolution. The careful balance between numerical accuracy and computational efficiency remains central to MD methodology, with ongoing developments in neighbor searching, integration algorithms, and force calculation techniques continually expanding the frontiers of accessible time and length scales.

As MD simulations continue to evolve through integration with machine learning, enhanced sampling methods, and high-performance computing, the fundamental algorithm described here remains the foundation upon which these advances are built. For researchers in drug development and related fields, understanding these core principles is essential for both effectively applying simulation methods and critically interpreting their results in the context of experimental data.

In the realm of molecular dynamics (MD) research, the empirical potential energy function, commonly known as a force field, serves as the fundamental engine that drives all simulations. A force field is a computational model composed of parametric equations and corresponding parameter sets used to calculate the potential energy of a system of atoms and molecules based on their coordinates [7] [8]. This potential energy surface then allows for the calculation of forces acting upon each atom, enabling the simulation of molecular motion over time according to Newton's mechanics [9].

Force fields provide a powerful approximation of 'true' molecular interactions, offering a balance between computational efficiency and physical accuracy that enables researchers to tackle biological questions inaccessible to purely quantum mechanical methods [7]. The development and refinement of these mathematical representations has become indispensable across computational physics, physical chemistry, molecular biology, and engineering, with particular significance in drug development where understanding molecular interactions at atomic resolution can accelerate discovery pipelines [7].

Mathematical Deconstruction of the Potential Energy Function

The total potential energy in an additive force field follows a consistent functional form that partitions interactions into bonded and non-bonded components [8]:

E_total = E_bonded + E_non-bonded

Where the bonded terms further decompose into:

E_bonded = E_bond + E_angle + E_dihedral + E_improper

And non-bonded terms consist of:

E_non-bonded = E_electrostatic + E_van der Waals

This partitioning reflects different physical interactions that contribute to the overall molecular energy landscape, each with distinct mathematical representations and parameterizations optimized through decades of research.

Bonded Interaction Potentials

Bonded interactions describe the energy associated with deviations from ideal molecular geometry, encompassing connections between directly covalently-bonded atoms.

Table 1: Bonded Interaction Energy Terms

| Interaction Type | Mathematical Form | Parameters | Physical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Stretching | V_bond = k_b(r_ij - r_0)² |

k_b = bond force constant, r_0 = equilibrium bond length |

Energetic cost of stretching/compressing chemical bonds from equilibrium length [9] [8] |

| Angle Bending | V_angle = k_θ(θ_ijk - θ_0)² |

k_θ = angle force constant, θ_0 = equilibrium angle |

Energy required to bend bond angles from preferred geometry [9] |

| Dihedral/Torsion | V_dihedral = k_φ[1 + cos(nφ - δ)] |

k_φ = torsional barrier height, n = periodicity, δ = phase angle |

Energy associated with rotation around central bonds, describing conformational preferences [9] |

| Improper Torsion | V_improper = k_ω(ω - ω_0)² |

k_ω = force constant, ω_0 = equilibrium angle |

Enforcement of planarity in aromatic rings and other conjugated systems [9] |

Non-Bonded Interaction Potentials

Non-bonded interactions operate between all atoms in the system, regardless of connectivity, and represent the computationally most intensive component of force field evaluation.

Table 2: Non-Bonded Interaction Energy Terms

| Interaction Type | Mathematical Form | Parameters | Physical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| van der Waals (Lennard-Jones) | V_LJ = 4ε[(σ/r)¹² - (σ/r)⁶] |

ε = potential well depth, σ = van der Waals radius |

Pauli repulsion (r⁻¹²) and London dispersion attraction (r⁻⁶) between electron clouds [9] |

| Electrostatics | V_Coulomb = (q_iq_j)/(4πε_0ε_rr_ij) |

q_i, q_j = atomic partial charges, ε_r = dielectric constant |

Coulombic interaction between fixed partial atomic charges [9] |

| van der Waals (Buckingham) | V_Buckingham = A·exp(-Br) - C/r⁶ |

A, B = repulsion parameters, C = dispersion parameter |

Alternative potential with exponential repulsion; risk of "Buckingham catastrophe" at short distances [9] |

Force Field Classification and Methodological Approaches

Force fields can be systematically categorized according to multiple attributes, including their modeling approach, level of detail, and parametrization philosophy [7].

The classification reveals important methodological distinctions:

Transferable vs. Component-Specific: Transferable force fields (e.g., AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS-AA) employ building blocks applicable across chemical space, while component-specific ones target individual molecules [7] [8].

All-Atom vs. United-Atom: All-atom force fields explicitly represent every hydrogen, while united-atom potentials combine hydrogens with heavy atoms, reducing computational cost [8].

Class 1, 2, and 3 Force Fields: Class 1 (AMBER, CHARMM) uses simple harmonic potentials; Class 2 (MMFF94) introduces anharmonicity and cross-terms; Class 3 (AMOEBA, DRUDE) explicitly incorporates polarization and other electronic effects [9].

Experimental Protocols: Parameterization and Validation

Traditional Parameterization Methodology

The development of classical force fields follows rigorous protocols combining theoretical and experimental data:

Quantum Mechanical Calculations: High-level quantum calculations (DFT, MP2, or CCSD(T)) provide target data for intramolecular parameters (bond, angle, dihedral) and partial atomic charges [8] [10].

Liquid-State Property Fitting: Intermolecular parameters (Lennard-Jones) are optimized to reproduce experimental liquid densities and enthalpies of vaporization [8].

Crystallographic Data: Bond and angle equilibrium values are often derived from high-resolution crystal structures of small molecule analogs [8].

Spectroscopic Validation: Vibrational frequencies from IR and Raman spectroscopy validate bond and angle force constants [8].

Advanced Data Fusion Approaches

Recent methodologies combine diverse data sources for enhanced accuracy:

Bottom-Up Learning: Training on energies, forces, and virial stress from quantum calculations (typically DFT) to reproduce the underlying electronic structure model [10].

Top-Down Learning: Direct optimization against experimental observables (elastic constants, lattice parameters) using differentiable simulation techniques [10].

Fused Data Strategy: Concurrent training on both DFT data and experimental measurements to overcome limitations of either approach alone, as demonstrated for titanium force fields [10].

Table 3: Data Fusion Training Protocol

| Training Phase | Data Source | Target Properties | Optimization Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| DFT Pre-training | Density Functional Theory Calculations | Energy, atomic forces, virial stress | Batch gradient descent using direct regression [10] |

| Experimental Fine-tuning | Experimental Measurements | Elastic constants, lattice parameters, thermodynamic properties | Differentiable Trajectory Reweighting (DiffTRe) or similar methods [10] |

| Validation | Independent DFT & Experimental Data | Unseen configurations and material properties | Early stopping based on hold-out set performance [10] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Force Field Resources and Applications

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Biomolecular Force Fields | AMBER, CHARMM, GROMOS, OPLS-AA | Simulation of proteins, nucleic acids, lipids; drug binding studies [9] [7] |

| General Organic Force Fields | CGenFF, GAFF, OPLS-AA | Small molecule parametrization for drug-like compounds [7] |

| Polarizable Force Fields | AMOEBA, CHARMM-Drude, OPLS5 | Enhanced accuracy for electrostatic interactions; polarized environments [9] [11] |

| Force Field Databases | TraPPE, MolMod, OpenKIM | Repository of validated parameters; transferable building blocks [7] [8] |

| Machine Learning Potentials | MPNICE, UMA, NequIP | Near-DFT accuracy with MD scalability; reactive systems [11] [10] |

| Parametrization Tools | MATCH, Antechamber, LigParGen | Automated parameter assignment for novel molecules [7] |

Emerging Frontiers: Machine Learning Force Fields

The field is undergoing a transformation through machine learning interatomic potentials (MLFFs) that bridge the accuracy-efficiency gap:

MLFFs represent an intermediate approach between classical force fields and quantum mechanics, maintaining linear scaling while approaching quantum accuracy [11]. Key advancements include:

Architectural Innovation: Message Passing Networks with Iterative Charge Equilibration (MPNICE) explicitly incorporate atomic charges and long-range electrostatics across 89 elements [11].

Data Efficiency: Active learning strategies selectively generate training configurations in underrepresented regions of chemical space [10].

Transferability: Universal Models for Atoms (UMA) provide coverage across most of the periodic table with high accuracy [11].

Specialized Applications: MLFFs enable battery electrolyte simulation, catalyst design, polymer characterization, and crystal structure prediction with unprecedented fidelity [11].

Critical Implementation Considerations

Combining Rules for Non-Bonded Interactions

The treatment of interactions between different atom types requires combining rules to avoid parameter proliferation:

Table 5: Common Lennard-Jones Combining Rules

| Rule Name | Mathematical Form | Application |

|---|---|---|

| Geometric Mean | σ_ij = √(σ_ii × σ_jj), ε_ij = √(ε_ii × ε_jj) |

GROMOS force field [9] |

| Lorentz-Berthelot | σ_ij = (σ_ii + σ_jj)/2, ε_ij = √(ε_ii × ε_jj) |

CHARMM, AMBER force fields [9] |

| Waldman-Hagler | σ_ij = ((σ_ii⁶ + σ_jj⁶)/2)^(1/6), ε_ij = √(ε_iiε_jj) × (2σ_ii³σ_jj³)/(σ_ii⁶ + σ_jj⁶) |

Noble gases; specialized applications [9] |

Treatment of Long-Range Interactions

Electrostatic interactions require specialized techniques due to their slow r⁻¹ decay:

Particle Mesh Ewald (PME): Efficient summation technique for periodic systems that divides interactions into short-range real-space and long-range reciprocal-space components.

Reaction Field Methods: Continuum dielectric treatment beyond a cutoff distance appropriate for non-periodic systems.

Multipole Expansions: Higher-order electrostatic moments for systems requiring beyond point-charge accuracy.

Empirical potential energy functions have evolved from simple harmonic approximations to sophisticated models incorporating quantum mechanical effects through machine learning approaches. The continued refinement of force fields remains crucial for advancing molecular dynamics research, particularly in drug development where accurate prediction of binding affinities, conformational dynamics, and solvation effects directly impact discovery pipelines. As MLFF methodologies mature and integrate more diverse experimental data sources, the traditional accuracy-efficiency compromise that has long constrained molecular simulation continues to diminish, opening new frontiers for computational investigation of biological systems at unprecedented resolution and scale.

Within the framework of molecular dynamics (MD) research, the concept of thermodynamic ensembles is foundational. An ensemble is a collection of points that can independently describe the states of a system, representing all possible scenarios to help compute accurate observable properties [12]. By constraining specific thermodynamic variables (like energy, temperature, or pressure) and allowing others to fluctuate, ensembles act as artificial constructs that allow MD simulations to mimic specific experimental conditions [12]. The choice of ensemble directly influences which thermodynamic free energy is sampled and must be aligned with the physical context of the system and the properties of interest [13]. This guide provides an in-depth examination of the three primary ensembles—NVE, NVT, and NPT—detailing their theoretical basis, practical implementation, and application within modern computational research.

Core Ensemble Theory

The Microcanonical (NVE) Ensemble

The NVE ensemble, also known as the microcanonical ensemble, characterizes an isolated system where the Number of particles (N), the Volume (V), and the total Energy (E) are conserved [12] [14]. In this ensemble, the system evolves according to Hamilton's equations of motion, which inherently conserve the Hamiltonian, H(P, r) = E [12]. The total energy E is the sum of kinetic (KE) and potential energy (PE). As atoms move on the Potential Energy Surface (PES), their potential energy changes when they enter valleys (low PE) or cross peaks (high PE); to keep the total energy constant, the kinetic energy—and consequently the atomic velocities and instantaneous temperature—must fluctuate accordingly [12].

NVE is the most straightforward ensemble from a theoretical perspective because it directly mirrors the numerical integration of Newton's equations of motion without external perturbations [15]. It is particularly crucial for studying dynamical properties where energy conservation is paramount, or for investigating a system's native PES using formalisms like the Green-Kubo relation [12]. A sample INCAR file for a VASP NVE simulation using the Andersen thermostat is shown below [14]:

The Canonical (NVT) Ensemble

The canonical, or NVT, ensemble maintains a constant Number of particles (N), Volume (V), and Temperature (T) [16]. Here, the system is connected to a virtual heat bath or thermostat, allowing it to exchange energy with its surroundings to maintain a constant temperature [12]. Unlike NVE, the total energy E is not constant; when the system moves through valleys and peaks on the PES, the kinetic energy does not have to change, as the thermostat provides or consumes energy to stabilize the temperature [12].

This ensemble is ideal for simulating systems at a fixed temperature, such as biological molecules under physiological conditions [16]. The thermostat's role is not to keep the instantaneous temperature perfectly constant but to ensure the average temperature is correct and that the fluctuations around this average are of the proper size [17]. In NVT, a system can theoretically access different PESs; at higher temperatures, it can overcome energy barriers more easily, escaping saddle points to explore wider regions of the phase space [12].

The Isothermal-Isobaric (NPT) Ensemble

The isothermal-isobaric, or NPT, ensemble keeps the Number of particles (N), Pressure (P), and Temperature (T) constant [16]. It employs both a thermostat to maintain temperature and a barostat to maintain pressure, the latter by dynamically adjusting the simulation box volume [12]. This introduces volume fluctuations and makes the PES more complex, as the system experiences changes due to variations in both energy and volume [12].

The NPT ensemble is exceptionally well-suited for mimicking standard experimental conditions, which are often conducted at constant temperature and pressure [13] [12]. It is the ensemble of choice for determining the equilibrium density of a system, studying phase transitions, and traversing phase diagrams [12]. It is crucial to remember that pressure exhibits significant inherent fluctuations in MD, with variations of hundreds of bar being typical, even for systems of hundreds of particles [17].

Table 1: Comparison of Key Thermodynamic Ensembles in Molecular Dynamics

| Ensemble | Constant Variables | Fluctuating Quantities | Physical Analogue | Primary Usage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NVE (Microcanonical) | N, V, E [12] [14] | Temperature, Pressure [12] | Isolated system [12] | Fundamental dynamics, PES exploration [12] |

| NVT (Canonical) | N, V, T [16] | Total Energy, Pressure [12] | System in a heat bath [12] | Biological systems, fixed-volume studies [16] |

| NPT (Isothermal-Isobaric) | N, P, T [16] | Total Energy, Volume [12] | System in a heat & pressure bath [12] | Mimicking experiment, density, phase changes [13] [12] |

Practical Implementation and Protocols

Thermostats and Barostats

Algorithms that control temperature and pressure are vital for NVT and NPT simulations. Thermostats can be broadly categorized, each with distinct strengths and weaknesses [12].

The Nosé-Hoover thermostat is an extended system method that treats the heat bath as an integral part of the system by introducing additional degrees of freedom [15] [12]. It is generally considered reliable and correctly reproduces a canonical ensemble [15]. A key parameter is the thermostat timescale (τₜ), which determines the period of characteristic oscillations; relaxation usually takes longer with Nosé-Hoover than with Berendsen for the same τ [18] [15]. For enhanced stability, a chain of thermostats (Nosé-Hoover Chains) is often used, with a default chain length of 3 being sufficient for most cases [15].

The Berendsen thermostat uses a weak-coupling algorithm that scales velocities periodically to push the temperature toward the desired value at a controlled rate [12]. It is known for effectively suppressing temperature oscillations and can be more stable in some situations [15]. However, a key drawback is that it does not exactly reproduce a canonical ensemble, meaning measured observables may not have the perfectly correct distribution [15]. Therefore, it is often recommended primarily for equilibration stages rather than production runs [15].

The Langevin thermostat individually couples each particle to the heat bath by introducing friction and stochastic collision forces [15]. This creates a very tight coupling, as if the system were in a viscous medium, but it also suppresses the natural dynamics more pronouncedly [15]. It should, therefore, be used for generating structures or sampling rather than for calculating dynamical properties like diffusion [15].

For NPT simulations, barostats control the pressure. The Berendsen barostat shares the same weaknesses as its thermostat counterpart and is not recommended for production simulations [15]. Modern stochastic methods, like the Bernetti Bussi barostat, are usually a better choice as they properly sample the NPT ensemble even for small unit cells [15].

Table 2: Common Thermostats and Their Characteristics

| Thermostat | Coupling Type | Ensemble Fidelity | Impact on Dynamics | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nosé-Hoover | Extended System [12] | High (Correct ensemble) [15] | Moderate | Production simulations [15] |

| Berendsen | Weak-Coupling [12] | Low (Suppresses fluctuations) [15] | Low | Equilibration & stabilization [15] |

| Langevin | Stochastic [15] | High (Correct ensemble) | High (Suppressive) [15] | Enhanced sampling, structure generation [15] |

| Bussi-Donadio-Parrinello | Stochastic [15] | High (Correct ensemble) [15] | Low | Robust canonical sampling [15] |

A Workflow for Robust Equilibration

A critical principle in MD is that measurements should only be performed after the system has reached equilibrium, unless specifically studying non-equilibrium phenomena [15]. Equilibration times can vary widely, up to hundreds of nanoseconds for complex systems like polymers [15].

A standard equilibration protocol involves a multi-stage process to gently bring the system to the desired state. A typical workflow, which helps avoid issues like the "hot solvent/cold solute" problem, is to couple the entire system to a single thermostat, rather than using separate thermostats for different components [17].

Parameter Selection and Best Practices

Selecting appropriate simulation parameters is crucial for achieving accurate and stable results.

- Time Step: This is a critical parameter determining the accuracy of numerical integration. It must be small enough to resolve the highest vibrational frequencies in the system, typically 0.5 to 2 femtoseconds (fs). If light atoms like hydrogen are present, a smaller time step (~1 fs) is generally required [15]. A safe starting point is 1 fs [15].

- Thermostat Coupling: The thermostat timescale parameter (τ or tau) controls how tightly the system is coupled to the heat bath. A small tau causes tight coupling and close temperature tracking but can cause more significant interference with the natural dynamics. For precise measurement of dynamical properties, use a larger tau or consider an NVE production run after equilibration [15].

- System Preparation: Using an orthogonal simulation cell is often more convenient, especially if the cell size will change [15]. The cell should be large enough so that its length is more than twice the interaction range of the potential to minimize finite-size effects [15].

- Pressure Coupling: As with thermostats, the barostat time scale parameter controls the response speed to pressure deviations. Isotropic pressure coupling is suitable for liquids or cubic crystals, while anisotropic coupling is needed for more complex materials [15]. Remember that pressure fluctuations are intrinsic to MD; instantaneous pressure is meaningless, and it must be treated as a time-averaged property [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential Software and Algorithms

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Velocity Verlet | Integrator [15] | Numerically solves equations of motion [16] | More stable than simple Verlet; requires careful time step selection [15]. |

| Nosé-Hoover Chains | Thermostat [18] | Controls temperature, sampling correct NVT ensemble [15] | Use a chain length of 3 as default; longer chains for persistent oscillations [15]. |

| MTTK Barostat | Barostat [18] | Controls pressure in NPT simulations [18] | Often combined with NHC thermostat. Anisotropic version is Parrinello-Rahman [18]. |

| Berendsen Thermostat | Thermostat [18] | Quickly relaxes system to target temperature [15] | Use for equilibration, not production, as it suppresses fluctuations [15]. |

| Langevin Thermostat | Thermostat [15] | Controls temperature via stochastic forces [15] | Good for sampling; high friction damps dynamics. Useful for small groups [15] [17]. |

| Periodic Boundary Conditions | Boundary Condition [17] | Mimics an infinite system to avoid surface effects [17] | Molecules will diffuse freely; trajectory processing needed for visualization [17]. |

Decision Framework for Ensemble Selection

The choice of ensemble is not arbitrary but should be dictated by the specific scientific question and the experimental conditions one aims to replicate. The following diagram outlines a logical decision process for selecting the appropriate ensemble.

Advanced Considerations and Future Directions

Ensemble Equivalence and Limitations

In the thermodynamic limit (for an infinite system size), and away from phase transitions, ensembles are generally believed to be equivalent [13]. This means basic thermodynamic properties can be calculated as averages in any convenient ensemble [13]. However, practical MD simulations operate with a finite number of particles, making the choice of ensemble critical as results will differ [13]. For instance, in a system with an energy barrier just below the total NVE energy, the rate of crossing that barrier would be zero, whereas in an NVT simulation with the same average energy, thermal fluctuations would allow barrier crossing to occur [13].

Furthermore, thermostats and barostats are not physically neutral. They can introduce artifacts, particularly in small systems or those with few degrees of freedom. For example, the Nosé-Hoover thermostat can exhibit a lack of ergodicity for a simple harmonic oscillator [13]. It is therefore not recommended to use separate thermostats for every component of a system, as each group must be of sufficient size to justify its own thermostat [17].

Emerging Trends

The field of MD is continuously evolving. Key areas of advancement that are pushing the boundaries of ensemble application and accuracy include:

- Machine Learning and AI Integration: Machine learning algorithms are being developed to speed up MD simulations by providing more accurate predictions of molecular interactions, potentially bypassing traditional force field limitations [16].

- Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics (QM/MM): Hybrid QM/MM methods combine the accuracy of quantum mechanics for a reactive core with the efficiency of classical mechanics for the environment, allowing for more accurate simulation of processes like enzyme catalysis where electronic effects are critical [16].

- Enhanced Sampling Methods: Techniques such as metadynamics and replica exchange are increasingly used to overcome the timescale limitation of MD, allowing researchers to sample rare events (e.g., protein folding, ligand unbinding) that would be inaccessible through standard simulations [16].

The strategic selection and proper implementation of thermodynamic ensembles—NVE, NVT, and NPT—are foundational to the integrity and relevance of molecular dynamics research. NVE provides a fundamental view of an isolated system's dynamics, NVT is essential for studying systems at a fixed temperature, and NPT is critical for replicating common experimental conditions. The choice hinges on the specific scientific question, with the understanding that finite system sizes in MD make this choice non-trivial. As the field advances with machine learning, quantum-mechanical hybrids, and enhanced sampling, the principles governing these ensembles will continue to underpin the meaningful simulation of complex molecular phenomena, from drug design to materials discovery.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation is a cornerstone computational technique in molecular biology, chemistry, and materials science, enabling researchers to study the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time. For researchers and drug development professionals, the reliability of these simulations is paramount and is fundamentally determined by the initial setup of the system. A proper setup, encompassing system preparation, solvation, and the implementation of periodic boundary conditions (PBCs), minimizes artifacts and ensures that the simulation accurately models the behavior of a real-world system. This guide details the core principles and practical methodologies for preparing a system for MD simulation, framed within the broader thesis that rigorous initial configuration is a prerequisite for obtaining scientifically valid results.

System Preparation: The Foundation

The preparation of the molecular system is the first and most critical step, as it defines the physical interactions that will govern the simulation.

Structure Cleanup and Parameterization

The initial model, often derived from crystallography or other experimental sources, must be processed to be suitable for simulation. Key tasks include adding missing hydrogen atoms, which are often not resolved in experimental structures, and assigning partial atomic charges and other force field parameters [19]. For standard residues, tools like those in the AMBER suite are commonly used, while non-standard residues require parameterization via modules like Antechamber [19]. A crucial step in this phase is running a structural minimization to relieve any steric clashes or unrealistic geometries introduced during the preparation process. This typically involves an initial round of steepest descent minimization followed by a more refined conjugate gradient algorithm to reach a stable energy minimum [19] [20].

Force Field Selection and Topology Generation

The force field defines the potential energy functions and associated parameters that describe interatomic interactions. The topology file, generated during system preparation, encapsulates this information for the specific system, defining atom types, bonds, angles, dihedrals, and non-bonded interaction parameters. The define option in parameter files can be used to control specific aspects, such as using flexible water models (-DFLEXIBLE) or including position restraints (-DPOSRES) [20]. Proper topology generation ensures that the potential energy surface on which the simulation operates is a faithful representation of molecular reality.

Solvation: Modeling the Environment

Most biological processes occur in an aqueous environment, making solvation a vital step for simulating realistic conditions.

Explicit vs. Implicit Solvent

Simulations can use either explicit or implicit solvent models. Explicit solvent models, which place individual water molecules around the solute, provide a more detailed and accurate representation of solute-solvent interactions but are computationally expensive. Implicit solvent models, which treat the solvent as a continuous dielectric medium, are less computationally demanding and can be efficient for certain types of calculations, such as those employing Poisson-Boltzmann methods [21]. For the highest accuracy in modeling biomolecular dynamics, explicit solvent is generally preferred.

Practical Solvation Protocol

The solvation process involves placing the prepared solute molecule into a pre-equilibrated box of water molecules and removing any water molecules that overlap with the solute's van der Waals radius. Tools like the Solvate tool in Chimera automate this process [19]. The size of the resulting solvent box is critical. An orthorhombic (rectangular) box is most common, and its dimensions can be set automatically based on the bounding box of the solute plus a padding distance (e.g., 2 Å on all sides) [19]. The choice of water model (e.g., SPC, TIP3P, TIP4P) should be consistent with the chosen force field.

System Neutralization

For systems with a net charge, such as proteins in solution, adding counterions (e.g., Na⁺ or Cl⁻) is necessary to achieve electro-neutrality. This is critical when using periodic boundary conditions with long-range electrostatic methods like Ewald summation, as a non-neutral system can lead to unphysical infinite energies [22]. Tools like Add Ions can be used to replace solvent molecules with ions to achieve a net zero charge [19].

Periodic Boundary Conditions (PBC)

PBCs are employed to simulate a bulk system by approximating an infinite solution, thereby eliminating the artificial surfaces that would exist in a isolated cluster of molecules [23] [22].

The Minimum Image Convention

PBCs are implemented by treating the central simulation box as a unit cell that is surrounded by translated copies of itself in all directions. The minimum image convention is a key principle, which states that a particle in the central box interacts only with the closest image of any other particle in the system [23] [22]. This convention is vital for calculating energies and forces correctly in a periodic system.

Box Geometries

While a cubic box is the most intuitive, other space-filling shapes can be more computationally efficient for simulating spherical solutes like proteins.

Table 1: Comparison of Common Periodic Box Types

| Box Type | Image Distance | Box Volume | Relative Volume vs. Cube | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cubic | (d) | (d^{3}) | 100% | Simple but least efficient for spherical solutes [23] |

| Rhombic Dodecahedron (xy-square) | (d) | (\frac{1}{2}\sqrt{2}~d^{3}) | ~71% | Most regular shape; minimal volume for given image distance [23] |

| Truncated Octahedron | (d) | (\frac{4}{9}\sqrt{3}~d^{3}) | ~77% | Closer to a sphere than a cube; requires fewer solvent molecules [23] |

For a given distance to the nearest image, a rhombic dodecahedron requires approximately 29% fewer solvent molecules than a cubic box, leading to significant computational savings [23]. In practice, GROMACS and other MD software support general triclinic boxes, which encompass all these shapes [23].

Critical Cut-off Restrictions

The use of PBCs imposes strict limitations on the cut-off radii used for calculating short-range non-bonded interactions. To comply with the minimum image convention, the cut-off radius (R_c) must be less than half the length of the shortest box vector [23] [19]:

[R_c < {\frac{1}{2}}\min(\|{\bf a}\|,\|{\bf b}\|,\|{\bf c}\|)]

Furthermore, for efficiency in grid-based searching algorithms, an even stricter restriction often applies [23]: [Rc < \min(ax, by, cz)] Violating these conditions can result in unphysical interactions where a particle interacts with multiple images of the same particle.

Long-Range Electrostatics under PBC

For long-range electrostatic interactions, simple cut-offs are inadequate as they can introduce severe artifacts. Instead, lattice summation methods like Ewald Sum, Particle Mesh Ewald (PME), and PPPM are used [23] [19]. These methods split the electrostatic calculation into a short-range part handled in real space and a long-range part computed in reciprocal (Fourier) space, providing an accurate and efficient treatment of Coulomb interactions in a periodic system.

Integrated Workflow for System Setup

The following diagram and table summarize the end-to-end process of preparing a system for molecular dynamics simulation.

Figure 1: A sequential workflow for preparing and running a molecular dynamics simulation.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for MD Setup

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Force Field | Defines potential energy functions and parameters for atoms. | AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS [19] [20] |

| Water Model | Represents solvent water molecules explicitly. | TIP3P, SPC, TIP4P [19] |

| Ions | Neutralizes system charge and mimics physiological ionic strength. | Na⁺, Cl⁻, K⁺ [19] [22] |

| Simulation Box | Defines the periodic unit cell for the simulation. | Cubic, Rhombic Dodecahedron, Truncated Octahedron [23] |

| Electrostatic Method | Handles long-range Coulomb interactions under PBC. | Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) [23] [20] |

Equilibration and Production

Once the system is prepared, solvated, and placed under PBC, it must be equilibrated before production dynamics can begin. Equilibration allows the solvent and ions to relax around the solute and for the system to reach the desired temperature and density. This is typically done in stages:

- Minimization: Further energy minimization of the entire solvated system is performed to remove any residual steric clashes introduced during solvation [19] [20].

- Thermalization: The system is gently heated to the target temperature (e.g., 298 K) over a short simulation using a thermostat, which controls the temperature by rescaling velocities or using stochastic terms [19] [20].

- Density Equilibration: For constant-pressure (NPT) simulations, a barostat is applied to adjust the box size to achieve the correct density [19].

Following successful equilibration, the production phase begins, during which the trajectory data used for analysis is collected. The parameters for this phase, such as the integrator (e.g., md or md-vv for velocity Verlet), time step (dt), and number of steps (nsteps), are set in the simulation parameter file [20].

The meticulous preparation of a molecular dynamics simulation system is not merely a preliminary step but a foundational component of the research process. The choices made during structure preparation, solvation, and the implementation of periodic boundary conditions directly dictate the physical fidelity and computational efficiency of the simulation. By adhering to the detailed protocols outlined herein—including the selection of an appropriate box geometry, strict adherence to cut-off restrictions, and proper treatment of long-range electrostatics—researchers can establish a robust platform for generating reliable and meaningful dynamics data. This rigorous approach to system setup underpins the entire thesis of molecular dynamics research, ensuring that subsequent analyses of structural stability, binding events, and mechanistic pathways are built upon a solid and trustworthy computational foundation.

The Role of Integrators, Thermostats, and Barostats

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the core objective is to predict the time evolution of a system of atoms by numerically solving their equations of motion. This process enables researchers to observe atomic-scale phenomena that are often inaccessible experimentally. The fidelity of these simulations hinges on three fundamental classes of algorithms: integrators, which propagate the system forward in time; thermostats, which maintain a constant temperature; and barostats, which control pressure. Together, these algorithms allow for the simulation of realistic thermodynamic ensembles, making MD a powerful tool for investigating biomolecular interactions, material properties, and chemical reactions in fields such as drug development and energy systems research. This guide details the principles, selection criteria, and implementation protocols for these essential components, providing a scientific foundation for robust molecular dynamics research.

Molecular Dynamics Integrators

Principles and Equations of Motion

Integrators are numerical algorithms that solve Newton's classical equations of motion for a system of N particles. The foundational equation is:

F~i~ = m~i~a~i~ = -∂V/∂r~i~ [24]

where F~i~ is the force acting on atom i, m~i~ is its mass, a~i~ is its acceleration, and V is the potential energy function of the system. The integrator's role is to use the computed forces to update atomic positions (r) and velocities (v) over discrete time steps (∆t) [24] [25]. The choice of integrator directly impacts the simulation's stability, energy conservation, and ability to capture correct dynamical properties.

Classification and Comparison of Common Integrators

The following table summarizes key integrators used in MD packages like GROMACS, along with their characteristics and typical applications [26].

Table 1: Comparison of Common Molecular Dynamics Integrators

| Integrator Name | Algorithm Type | Key Features | Computational Cost | Primary Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Leap-Frog (md) |

Verlet-derived | Time-reversible, efficient, good energy conservation | Low | Standard production NVE, NVT, and NPT simulations |

Velocity Verlet (md-vv) |

Verlet-derived | More accurate velocities than leap-frog, symplectic | Moderate | Accurate NVE; required for advanced Trotter-based coupling |

Velocity Verlet (avek) (md-vv-avek) |

Verlet-derived | Identical to md-vv but with more accurate kinetic energy averaging |

Moderate | Accurate thermodynamics with Nose-Hoover/Parrinello-Rahman |

Stochastic Dynamics (sd) |

Langevin Dynamics | Implicit solvent model, temperature control via friction and noise | Low to Moderate | Simulating biomolecules in solution without explicit solvent |

Brownian Dynamics (bd) |

Position Langevin | Overdamped dynamics, ignores inertia | Low | Very large molecules or high friction environments |

Implementation Protocol: Setting up a Basic MD Simulation

Objective: Perform a 100 ps molecular dynamics simulation of a protein in explicit solvent using the leap-frog integrator.

Software: GROMACS [26].

Input Files: System topology (topol.top), molecular structure (conf.gro), parameters (mdp file).

- Parameter File Configuration (

mdp): - Execution Command:

- Validation: Monitor the total energy, temperature, and pressure of the system from the resulting

simulation.edrenergy file to ensure stability.

Temperature Control: Thermostats

The Role of Thermostats in MD

In a closed system (NVE ensemble), the total energy is conserved, but temperature can fluctuate. To mimic the real-world behavior of a system coupled to an external heat bath (e.g., a solvent), a thermostat is applied. Thermostats stochastically or deterministically modify particle velocities to maintain the system's average temperature at a specified value (T~0~), enabling simulations in the canonical (NVT) ensemble [25]. This is critical for comparing simulation results with laboratory experiments conducted at constant temperature.

Thermostat Algorithms and Their Parameters

Different thermostats vary in their method of controlling temperature and their impact on the system's dynamics.

Table 2: Comparison of Common Thermostat Algorithms

| Thermostat | Coupling Type | Mechanism | Produces Canonical Ensemble? | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berendsen | Weak coupling | Scales velocities to exponentially relax to T~0~ | No (produces incorrect fluctuations) | tau-t (coupling time constant) |

| Nosé-Hoover | Deterministic | Extended Lagrangian with a thermal reservoir variable | Yes | tau-t (oscillation period of the thermostat) |

| Velocity Rescale | Stochastic | Rescales velocities based on a stochastic differential equation | Yes (improved over Berendsen) | tau-t, ref-t (reference temperature) |

| Langevin | Stochastic | Adds friction and random noise to the forces | Yes | bd-fric (friction coefficient) or tau-t |

Implementation Protocol: Applying a Nosé-Hoover Thermostat

Objective: Maintain a protein-ligand system at 310 K using a Nosé-Hoover thermostat. Software: GROMACS [26].

- Parameter File Configuration (

mdp): - Analysis: After the simulation, plot the temperature over time from the energy file to verify that the average is 310 K and observe the quality of the fluctuations.

Pressure Control: Barostats

The Role of Barostats in MD

While thermostats control temperature, barostats control the pressure of the system by adjusting the simulation box size and shape. This is essential for simulating condensed-phase systems (liquids, solids) at realistic densities, corresponding to the isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensemble. Without a barostat, a system might adopt an unrealistic density, especially when temperature is coupled [25].

Barostat Algorithms and Their Parameters

Barostats work in conjunction with thermostats to maintain constant pressure and temperature.

Table 3: Comparison of Common Barostat Algorithms

| Barostat | Coupling Type | Mechanism | Key Features | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berendsen | Weak coupling | Scales box size to exponentially relax to P~0~ | Fast and stable, but produces incorrect fluctuations | tau-p, ref-p, compressibility |

| Parrinello-Rahman | Deterministic | Extended Lagrangian with a barostatic variable | Correct for NPT ensemble, allows for flexible box deformation | tau-p, ref-p, compressibility |

| Martyna-Tuckerman- Klein (MTK) | Deterministic | Extended Lagrangian formalism | Theoretically correct barostat for use with Nosé-Hoover thermostat | tau-p, ref-p, compressibility |

Implementation Protocol: Isotropic Pressure Coupling with Parrinello-Rahman

Objective: Maintain a solvated system at 1 bar pressure using the Parrinello-Rahman barostat. Software: GROMACS [26].

- Parameter File Configuration (

mdp): - Analysis: Monitor the box volume and density over time to ensure they converge to a stable average value.

Integrated Workflow and Visualization

The successful execution of an MD simulation requires the coordinated action of the integrator, thermostat, and barostat. The following diagram illustrates the logical flow and algorithmic relationships in a typical NPT simulation.

Diagram 1: NPT Simulation Algorithm Flow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key components and their functions required to set up and run a molecular dynamics simulation, analogous to a laboratory reagent list.

Table 4: Essential "Research Reagents" for a Molecular Dynamics Simulation

| Item | Function / Purpose | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Force Field | Defines the potential energy function (V); provides parameters for bonded and non-bonded interactions. | CHARMM36, AMBER, OPLS-AA. Choice depends on the system (proteins, lipids, nucleic acids). |

| Molecular System Topology | Describes the molecular composition, connectivity, and force field parameters for all atoms. | Generated from PDB file using tools like pdb2gmx or tleap. |

| Initial Coordinates | The starting 3D atomic positions for the simulation. | Often from experimental structures (Protein Data Bank, PDB) or homology modeling. |

| Initial Velocities | The starting atomic velocities, required by integrators like leap-frog. | Usually generated randomly from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution at the target temperature [24]. |

| Solvent Model | Represents the water and ion environment around the solute. | SPC/E, TIP3P, TIP4P water models. |

| Simulation Software | The engine that performs the numerical integration and force calculation. | GROMACS (used here), NAMD, AMBER, OpenMM. |

| Computing Hardware | Provides the processing power for computationally intensive force calculations. | High-Performance Computing (HPC) clusters, GPUs. |

From Theory to Therapy: Methodological Advances and Drug Discovery Applications

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide atomic-level insight into biological processes and molecular interactions, serving as a computational microscope for researchers. However, the timescales of critical phenomena, such as protein-ligand binding or conformational changes, often extend far beyond the reach of conventional MD simulations. This sampling limitation, known as the "rare event problem," has driven the development of enhanced sampling methods. Among the most rigorous and widely used are Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) and Umbrella Sampling (US). These techniques allow for the efficient calculation of free energy differences—the fundamental thermodynamic quantity determining binding affinities, conformational equilibria, and solubility. Within the broader thesis of molecular dynamics research, FEP and US represent sophisticated solutions to the central challenge of obtaining statistically meaningful thermodynamic and kinetic data from simulations of complex biological systems. This guide details their core principles, methodologies, and applications for researchers and drug development professionals.

Theoretical Foundations of Free Energy Calculations

The Central Role of Free Energy

In computational biophysics, the free energy landscape dictates the behavior of biomolecular systems. The Gibbs free energy (ΔG), in particular, quantifies the spontaneity of processes like binding and folding. A negative ΔG indicates a favorable process. For protein-ligand interactions, the binding free energy (ΔGbind) is the key computational metric for predicting affinity and can be directly compared with experimental measurements like those from isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) [27].

Overcoming the Sampling Challenge

Thermodynamic states of interest are often separated by high energy barriers. Crossing these barriers by spontaneous thermal motion in a standard MD simulation may require microseconds or more, making direct simulation impractical [28]. Enhanced sampling methods like FEP and US address this by altering the sampling algorithm to focus computational resources on these critical, but rarely visited, regions.

Free Energy Perturbation (FEP)

Core Principles and Workflow

Free Energy Perturbation is an alchemical method, meaning it calculates free energy differences by simulating a non-physical pathway that morphs one molecule into another. This is particularly powerful in drug discovery for estimating the relative binding free energies of a series of similar ligands to a target protein [27] [29].

The theoretical foundation of FEP lies in the following equation, which calculates the free energy difference between two states (0 and 1) by exponentially averaging the energy difference over configurations sampled from state 0:

ΔG = -kBT ln ⟨exp(-(E1 - E0)/kBT)⟩0

In practice, a direct transformation from one ligand to another is too disruptive, leading to poor convergence. Therefore, the change is broken down into a series of smaller, more gradual steps along a coupling parameter λ, which scales the Hamiltonian of the system from H0 to H1. The total free energy change is the sum of the changes across these λ windows [29].

Detailed FEP Experimental Protocol

A typical FEP workflow, as implemented in modern automated platforms like QUELO, involves several key stages [29]:

System Preparation: The process begins with a prepared protein receptor structure (in PDB format). This structure must be structurally complete, with all atoms present (including hydrogens), correct element entries, and consistent residue/atom naming. Unnecessary cofactors and non-essential waters are typically removed, though structurally important waters can be retained.

Ligand Parametrization: The reference ligand and all additional ligands are provided in 3D formats (SDF or MOL2). The platform automatically parametrizes the ligands. For classical MM FEP, this uses a molecular mechanics force field; advanced platforms may use AI-based parametrization trained on quantum mechanics data.

Ligand Alignment and Perturbation Mapping: Each additional ligand is automatically aligned to the reference ligand within the binding pocket, typically using a 3D maximum common substructure (MCS) algorithm. This alignment defines the "single" and "dual" topology regions for the alchemical transformation.

Solvation and System Setup: A periodic solvent box (e.g., water) is automatically generated around the protein-ligand complex. For membrane-bound systems, a pre-equilibrated membrane-solvent box can be supplied by the user.

Running the FEP Calculation: The calculation is distributed across multiple parallel simulations, each representing a different λ window. The system evolves through a series of MD simulations where the Hamiltonian is perturbed incrementally.

Analysis and Result Compilation: The relative free energy changes for each ligand mutation are computed from the ensemble of simulations, and the results are compiled and presented to the user.

Research Reagent Solutions for FEP

Table 1: Essential materials and software for conducting FEP calculations.

| Item | Function and Description |

|---|---|

| Protein Receptor (PDB File) | The common target structure; must be carefully prepared (protonated, loops added, naming consistent) [29]. |

| Reference Ligand (SDF/MOL2) | A ligand with a high-confidence binding pose, used to align all other ligands in the series [29]. |

| Ligand Series (SDF/MOL2) | The set of additional, structurally similar ligands for which relative binding free energies will be calculated [29]. |

| Solvent Box | The explicit solvent environment (e.g., TIP3P water) surrounding the solute, often generated automatically by the software [29]. |

| Force Field | The set of mathematical functions and parameters defining potential energy; can be classical MM or a hybrid QM/MM force field [29]. |

| FEP Software (e.g., QUELO) | Automated platforms that handle parametrization, setup, parallel execution, and analysis of complex FEP calculations [29]. |

Umbrella Sampling (US)

Core Principles and Workflow

Umbrella Sampling is a collective-variable (CV) based method designed to calculate the Potential of Mean Force (PMF) along a predefined reaction coordinate. The PMF is the effective free energy profile as a function of the CV, providing insight into the thermodynamics and kinetics of processes like ligand unbinding, ion transport, or conformational transitions [27] [30].

The method employs a stratification strategy. The reaction coordinate (e.g., the distance between a protein and ligand) is divided into multiple "windows." In each window, a harmonic restraining potential (the "umbrella") is applied to the CV, forcing the system to sample a specific region. The key is that these windows must overlap slightly. After running independent simulations for all windows, the data are combined using an algorithm like the Weighted Histogram Analysis Method (WHAM) to reconstruct the unbiased, continuous PMF [31] [32].

Advanced US Strategies: Employing Restraints

A major challenge in US, particularly for ligand unbinding, is the need to sample not just the distance but also the orientation and conformation of the molecules. Without restraints, the ligand may rotate or the protein may deform in ways that are not sufficiently sampled in a finite simulation, leading to poor convergence [27].

Advanced strategies introduce additional harmonic restraints on variables beyond the pull distance:

- Ligand Orientation (Ω): Defined using quaternion formalism, this restrains the relative rotation of the ligand with respect to the protein [27].

- Ligand and Protein Root-Mean-Square Deviation (rL and rP): These restraints keep the ligand and/or protein close to a reference bound conformation, reducing the conformational entropy that must be sampled [27].

The final binding free energy is calculated by integrating the PMF and applying analytical corrections for the effect of these restraints [27].

Detailed US Experimental Protocol

A standard Umbrella Sampling protocol, as outlined in GROMACS tutorials and GitHub workflows, involves the following steps [32] [30]:

System Setup and Equilibration: The protein-ligand complex is solvated in a solvent box, and the system is minimized, heated, and equilibrated under standard conditions (e.g., NPT ensemble at 300 K).

Steered MD (SMD) or Pulling Simulation: An nonequilibrium simulation is performed where an external force is applied to the ligand to pull it away from the binding site along the chosen reaction coordinate. This generates a trajectory covering the entire path of interest.

Window Configuration Selection: Multiple snapshots (e.g., 30-40) are extracted from the pulling trajectory at regular intervals along the reaction coordinate. Each snapshot serves as the initial structure for an umbrella sampling window.

Umbrella Sampling Simulations: An independent MD simulation is run for each window, with a harmonic restraint (e.g., with a force constant of 500-1000 kJ/mol/nm²) centered on the specific CV value for that window. Each simulation must be long enough for local convergence (typically several nanoseconds per window).

PMF Construction with WHAM: The trajectory data from all windows—specifically, the distribution of the CV in each window—are analyzed using the WHAM algorithm [31] [32]. WHAM optimally combines these biased distributions to remove the effect of the umbrella potentials and produce the final PMF. The binding free energy (ΔGbind) is derived from the difference in PMF values between the bound and unbound states [30].

Comparative Analysis and Practical Considerations

Quantitative Comparison of FEP and Umbrella Sampling

Table 2: A structured comparison of Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) and Umbrella Sampling (US).

| Feature | Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) | Umbrella Sampling (US) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Application | Relative binding free energies of similar ligands [29]. | Absolute binding free energy; PMF along a physical path (e.g., unbinding) [27] [30]. |

| Type of Pathway | Alchemical (non-physical transformation). | Physical (along a spatial reaction coordinate). |

| Key Output | Relative ΔΔG between ligands. | Potential of Mean Force (PMF) and absolute ΔG. |

| Sampling Challenge | Adequately sampling the changing van der Waals and electrostatic interactions at intermediate λ states. | Choosing a low-dimensional CV that accurately describes the process; avoiding orthogonal hidden barriers [28]. |

| Strengths | High throughput for ligand series; automated workflows; excellent for lead optimization [29]. | Provides a physical picture of the process; can reveal intermediate states and energy barriers. |

| Weaknesses | Limited to "small" structural changes between ligands; requires a common binding mode. | Can be computationally expensive; convergence is highly sensitive to CV choice and simulation length [27] [28]. |

Guidance for Method Selection

Choosing between FEP and US depends on the scientific question and available resources.

- Use FEP when the goal is to rapidly rank the binding affinity of a series of congeneric ligands in a drug discovery project. Its automated nature and efficiency make it ideal for this purpose [29].

- Use Umbrella Sampling when investigating the mechanism of a process (e.g., unbinding pathway, ion permeation), when calculating absolute binding free energies, or when the ligands of interest are not structurally similar. Be prepared to invest effort in validating the reaction coordinate and potentially using advanced restraints to ensure convergence [27] [28].

Free Energy Perturbation and Umbrella Sampling are two cornerstone techniques in the molecular dynamics toolkit, enabling the calculation of free energies that are directly relevant to biological function and therapeutic intervention. FEP excels in the high-throughput, relative free energy calculations that are essential for computer-aided drug discovery. In contrast, Umbrella Sampling provides a physically intuitive path to absolute binding free energies and mechanistic insights but demands careful setup and validation. As methods continue to evolve—with better force fields, more robust sampling algorithms, and increased automation—their integration into the standard workflow of researchers and drug developers will undoubtedly deepen, solidifying their role in bridging the gap between atomic-level simulation and experimental observables.

The Relaxed Complex Method (RCM) represents a pivotal advancement in computational drug design by explicitly incorporating target flexibility, a critical factor in molecular recognition. Traditional docking methods often treat the receptor as a rigid structure, which can fail to predict accurate binding modes for ligands that induce conformational changes upon binding. The RCM addresses this limitation by acknowledging that ligands may bind to conformations that occur only rarely in the dynamics of the receptor [33] [34]. This approach is particularly valuable for highly flexible targets like protein kinases and HIV-1 Integrase, where induced-fit effects are significant [34].

Framed within the broader principles of molecular dynamics (MD) research, the RCM leverages the fact that biomolecules are dynamic entities existing as an ensemble of conformations. The method synergistically combines MD simulations to generate a diverse set of receptor structures with docking and scoring algorithms to identify optimal ligand-binding configurations [34]. This paradigm aligns with the ongoing shift in the field towards treating MD data with FAIR principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) to enhance reproducibility and facilitate the reuse of simulation data as a rich source of information on biomolecular flexibility [35] [36].

Core Principles and Methodological Framework

The foundational principle of the Relaxed Complex Method is that molecular recognition is a dynamic process. The "lock and key" model is insufficient for many biological systems where both the ligand and the receptor adjust their conformations to achieve optimal binding—a phenomenon known as induced fit [34]. The RCM was inspired by experimental techniques like "SAR by NMR" and the "tether method," which also capitalize on the existence of multiple receptor conformations for ligand binding [34].

The method operates on the key insight that a ligand's affinity for a receptor is an average over its interactions with all the accessible conformational states of the receptor, weighted by the probability of each state. A ligand might exhibit high affinity not by binding strongly to the most common receptor conformation, but by selectively stabilizing a low-populated (rare) conformation from the ensemble. This makes MD simulations an ideal tool for sampling these various conformational states [34].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the core iterative process of the Relaxed Complex Method:

Diagram 1: The iterative workflow of the Relaxed Complex Method, from structure preparation through simulation, docking, and refined scoring.

The Three-Phase Protocol of the Relaxed Complex Method

The implementation of the RCM can be broken down into three distinct phases, each with specific methodologies and goals.

Phase 1: Conformational Sampling via Molecular Dynamics

The first and most critical step is generating a diverse and representative ensemble of receptor conformations.

- Objective: To capture the intrinsic flexibility and dynamics of the target protein under physiological conditions, including rare but druggable conformational states.

- Protocol:

- System Preparation: Obtain an initial protein structure, typically from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). Prepare the structure by adding hydrogen atoms, assigning protonation states, and embedding it in a solvation box with explicit water molecules (e.g., TIP3P water model). Add counterions to neutralize the system's charge.

- Energy Minimization: Perform energy minimization using steepest descent or conjugate gradient algorithms to remove any steric clashes and bad contacts in the initial structure.

- Equilibration: Conduct a series of short MD simulations with positional restraints on the protein heavy atoms to equilibrate the solvent and ions around the protein. This is followed by unrestrained equilibration of the entire system to achieve stable temperature and pressure.

- Production MD: Run a long, unbiased MD simulation (typically on the nanosecond to microsecond timescale) without restraints. The simulation should be performed in an isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensemble to maintain constant temperature (e.g., 300 K) and pressure (1 atm) using thermostats (e.g., Nosé-Hoover) and barostats (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman).

- Trajectory Analysis and Clustering: Save the atomic coordinates of the protein at regular intervals (e.g., every 100 ps). Analyze the resulting trajectory using root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of atomic positions and cluster the snapshots based on structural similarity (e.g., using k-means or hierarchical clustering) to select a non-redundant set of representative conformations for docking.

Phase 2: Docking to the Conformational Ensemble

In this phase, ligands are docked into the entire ensemble of receptor snapshots generated from the MD simulation.

- Objective: To rapidly screen a myriad of possible ligand-binding modes and poses across different receptor conformations.

- Protocol:

- Receptor Preparation: Prepare each protein snapshot from the ensemble for docking. This involves adding polar hydrogen atoms, assigning Gasteiger charges, and defining the binding site using a grid box that encompasses the region of interest.

- Ligand Preparation: Prepare the ligand(s) of interest by generating 3D structures, optimizing their geometry, and assigning appropriate rotatable bonds and torsions.

- High-Throughput Docking: Use rapid docking software like AutoDock [34] or similar tools (e.g., Vina, FRED) to perform the docking calculations. For each ligand, thousands of independent docking runs are performed against each protein conformation in the ensemble.

- Pose Selection: The output is a ranked list of ligand-protein complexes based on the docking scoring function. The best-ranked poses from across the entire ensemble are carried forward to the next phase for more refined scoring.

Phase 3: Re-scoring with Advanced Free Energy Calculations

The final phase involves applying more computationally intensive and theoretically rigorous methods to accurately rank the binding affinities of the best complexes identified in Phase 2.