Molecular Dynamics Simulation: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation, a computational technique that analyzes the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time.

Molecular Dynamics Simulation: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation, a computational technique that analyzes the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we cover the foundational principles of MD, its core methodologies, and its diverse applications in areas like drug discovery and materials science. The content also addresses common challenges and optimization strategies, compares MD with other modeling techniques, and discusses validation against experimental data. By synthesizing insights from current literature, this guide aims to be an essential resource for leveraging MD simulations to accelerate biomedical innovation.

The Foundations of Molecular Dynamics: From Basic Principles to Historical Evolution

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation is a powerful computational technique that functions as a virtual microscope, allowing researchers to observe the motion and interactions of atoms and molecules over time. By solving Newton's equations of motion for a system of interacting particles, MD provides insights into dynamic processes that are often difficult to capture through experimental methods alone. This capability makes it an indispensable tool in computational biology, materials science, and drug development, where understanding system behavior at the atomic level is crucial [1].

Core Principles and Computational Framework

At its core, molecular dynamics relies on classical mechanics to simulate the temporal evolution of a molecular system. The potential energy of all interactions within the system is calculated using a force field, which is a mathematical representation of the forces between atoms. The selection of an appropriate force field is critical, as it significantly influences the reliability of simulation outcomes [1].

The simulation process involves iterating through a cycle of calculating forces and integrating equations of motion, which progressively advances the system through time. Widely adopted MD software packages such as GROMACS, AMBER, and DESMOND leverage rigorously tested force fields and have shown consistent performance across diverse biological applications [1] [2]. These simulations are typically conducted within defined thermodynamic ensembles, such as the isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensemble, which maintains constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature [2].

Key Research Applications

Drug Discovery and Development

MD simulations have emerged as a pivotal tool in biomedical research, offering insights into intricate biomolecular processes such as structural flexibility and molecular interactions. They play a critical role in structure-based drug design by elucidating protein behavior and their interactions with inhibitors across different disease contexts. Simulations help identify binding sites, assess binding stability, and estimate free energies of interaction—all crucial for optimizing therapeutic compounds [1].

Solubility Prediction

In pharmaceutical development, solubility significantly influences a medication's bioavailability and therapeutic efficacy. MD simulations model various physicochemical properties, particularly solubility, by providing a detailed perspective on molecular interactions and dynamics. Research has demonstrated that MD-derived properties such as Solvent Accessible Surface Area, Coulombic and Lennard-Jones interaction energies, and Estimated Solvation Free energies can be effectively integrated with machine learning to predict aqueous solubility with high accuracy [2].

Materials Science and Energy Applications

MD simulations facilitate the design and optimization of advanced materials, including polymers for enhanced oil recovery and components for polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cells (PEMFCs). In oil-displacement polymers, MD helps observe polymer-oil interactions at the atomic scale and predict how changes in polymer properties affect performance [3]. For PEMFCs, MD simulations explore critical structural and transport phenomena at the molecular level within membranes and catalyst layers, addressing challenges related to performance degradation and material costs [4].

Quantitative Insights from MD Simulations

Table 1: Key MD-Derived Properties for Predicting Drug Solubility [2]

| Property | Description | Role in Solubility |

|---|---|---|

| logP | Octanol-water partition coefficient | Measures compound hydrophobicity |

| SASA | Solvent Accessible Surface Area | Indicates water-accessible molecular surface |

| Coulombic_t | Coulombic interaction energy with solvent | Quantifies polar interactions with water |

| LJ | Lennard-Jones interaction energy | Represents van der Waals interactions |

| DGSolv | Estimated Solvation Free Energy | Measures energy of transfer from gas to solution |

| RMSD | Root Mean Square Deviation | Indicates structural stability in solution |

Table 2: Performance of Machine Learning Models Using MD Properties for Solubility Prediction [2]

| Machine Learning Algorithm | Predictive R² | RMSE |

|---|---|---|

| Gradient Boosting | 0.87 | 0.537 |

| XGBoost | 0.85 | 0.562 |

| Extra Trees | 0.84 | 0.571 |

| Random Forest | 0.83 | 0.589 |

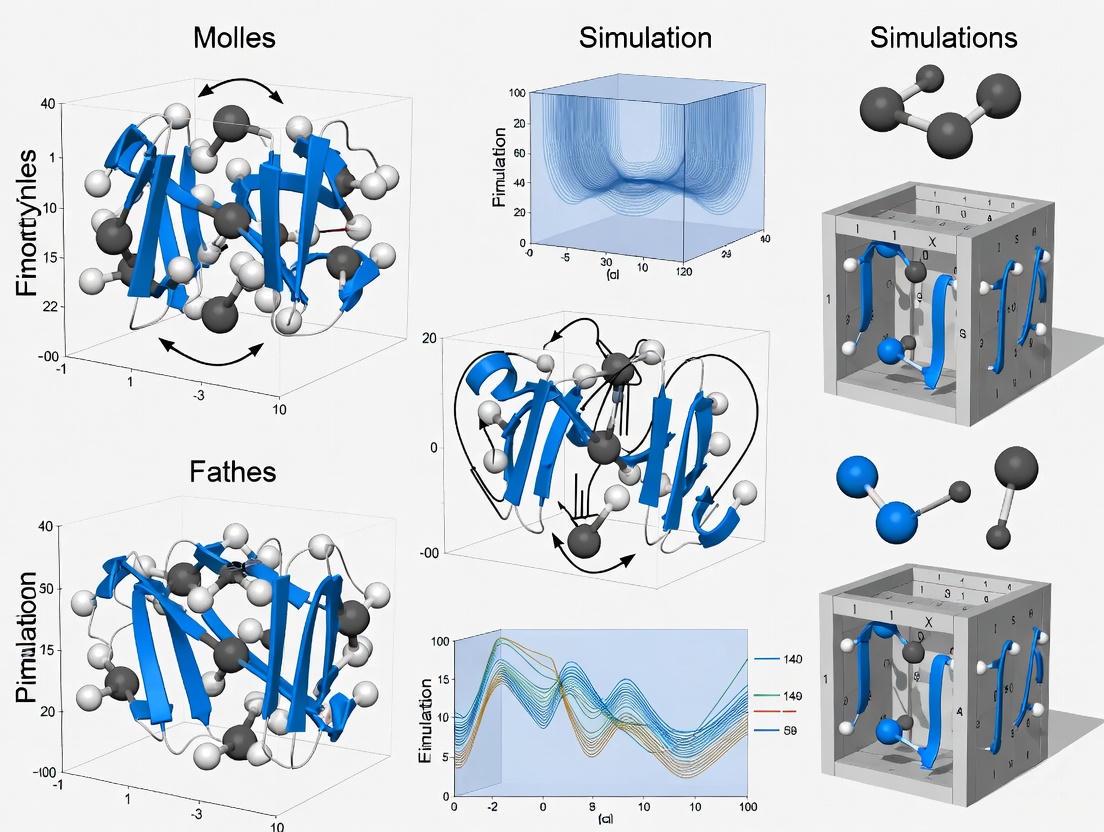

Advanced Visualization of Massive Systems

The growing scale of MD simulations, with systems now reaching hundreds of millions of atoms, presents significant visualization challenges. Next-generation tools like VTX employ meshless molecular graphics engines using impostor-based techniques and adaptive level-of-detail rendering to enable real-time visualization of massive molecular systems. This approach significantly reduces memory usage while maintaining rendering quality, allowing researchers to interactively explore complex molecular architectures that were previously difficult to visualize, such as the 114-million-bead Martini minimal whole-cell model [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 3: Essential Tools for Molecular Dynamics Simulations

| Tool/Software | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | High-performance MD simulation package | General biomolecular simulations; used for solubility property calculation [2] |

| AMBER | Suite of biomolecular simulation programs | Protein and nucleic acid simulations with specialized force fields [1] |

| DESMOND | MD software with graphical interface | Drug discovery and molecular interactions [1] |

| OpenMM | Toolkit for MD simulation using GPUs | Core engine for drMD automation pipeline [6] |

| drMD | Automated pipeline for non-experts | Simplifies setup and running of publication-quality simulations [6] |

| VTX | Meshless visualization software | Handling massive molecular systems (100M+ atoms) [5] |

| GROMOS 54a7 | Force field parameter set | Modeling molecules' neutral conformations [2] |

Future Directions and Integration with Machine Learning

The field of molecular dynamics continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging trends shaping its future. The integration of machine learning and deep learning technologies is expected to accelerate progress in this evolving field [1]. ML techniques are being combined with MD-derived properties to improve the accuracy of physicochemical predictions, such as aqueous solubility in drug development [2].

Future research will concentrate on developing multiscale simulation methodologies, exploring high-performance computing technologies, and integrating experimental data with simulation data [3]. Tools like drMD are making MD more accessible to non-experts by automating routine procedures and providing interactive explanations, thereby democratizing access to this powerful technology [6].

As MD simulations continue to bridge the gap between computational models and actual cellular conditions, they solidify their position as an indispensable computational microscope for researchers across scientific disciplines—from drug discovery to materials science and beyond.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation is an indispensable computational technique for predicting the time-evolution of particle systems based on Newton's equations of motion. This technical guide examines the core principles of solving Newton's equations within MD frameworks, detailing numerical integration methods, force field approximations, and practical implementation protocols. Framed within contemporary molecular dynamics research, this review highlights applications in drug delivery system optimization and biomolecular analysis, providing researchers and drug development professionals with foundational knowledge and methodological references for employing MD in therapeutic development.

Molecular dynamics is a computational method that uses Newton's equations of motion to simulate the time evolution of a set of interacting atoms [7]. These simulations capture the behavior of proteins and other biomolecules in full atomic detail and at very fine temporal resolution, providing insights inaccessible to experimental observation alone [8]. The foundation of MD relies on calculating the force exerted on each atom by all other atoms, then using Newton's laws of motion to predict atomic trajectories through time [8]. This results in a trajectory that essentially constitutes a three-dimensional movie describing the atomic-level configuration of the system throughout the simulated time interval [8].

The impact of MD simulations in molecular biology and drug discovery has expanded dramatically in recent years, driven by major improvements in simulation speed, accuracy, and accessibility [8]. These simulations have proven particularly valuable in deciphering functional mechanisms of proteins, uncovering structural bases for disease, and optimizing therapeutic compounds [8]. In pharmaceutical applications, MD has emerged as a vital tool for optimizing drug delivery for cancer therapy, offering detailed atomic-level insights into interactions between drugs and their carriers [9].

Newton's Equations of Motion: Theoretical Foundation

Fundamental Laws

Newton's laws of motion form the cornerstone of classical molecular dynamics simulations:

First Law: A body remains at rest, or in motion at a constant speed in a straight line, unless acted upon by a force [10]. This principle of inertia establishes that motion preserves the status quo unless perturbed by external forces.

Second Law: The net force on a body equals its mass multiplied by its acceleration (F = ma), equivalently expressed as the rate of change of momentum [10]. In modern notation, this is:

F = dp/dtwherep = mvrepresents momentum [10].Third Law: When two bodies interact, they apply forces to one another that are equal in magnitude and opposite in direction [10]. This principle of action-reaction ensures conservation of momentum in closed systems.

Mathematical Formulation

In molecular dynamics, Newton's second law provides the operational foundation for simulating particle systems. For a system of N particles, the equation of motion for the i-th particle is:

[ mi \frac{d^2\mathbf{r}i}{dt^2} = \mathbf{F}i = -\nablai U(\mathbf{r}1, \mathbf{r}2, \ldots, \mathbf{r}_N) ]

where ( mi ) is the mass of particle i, ( \mathbf{r}i ) is its position vector, ( \mathbf{F}_i ) is the total force acting on it, and ( U ) is the potential energy function of the system [11]. The force on each atom can be calculated from the derivative of the potential energy with respect to atomic positions [8].

Numerical Integration Methods for Newton's Equations

Since analytical solutions to Newton's equations are impossible for complex molecular systems, MD relies on numerical integration techniques. These methods discretize time into small steps (typically 1-2 femtoseconds) and approximate particle trajectories.

Table 1: Numerical Integration Algorithms in Molecular Dynamics

| Algorithm | Mathematical Formulation | Order of Accuracy | Computational Stability | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Verlet | ( r(t+\Delta t) = 2r(t) - r(t-\Delta t) + \frac{F(t)}{m}\Delta t^2 ) | O(Δt²) | Good (time-reversible) | General biomolecular systems |

| Leap-Frog | ( v(t+\Delta t/2) = v(t-\Delta t/2) + \frac{F(t)}{m}\Delta t ) ( r(t+\Delta t) = r(t) + v(t+\Delta t/2)\Delta t ) | O(Δt²) | Moderate | Large-scale systems |

| Velocity Verlet | ( r(t+\Delta t) = r(t) + v(t)\Delta t + \frac{F(t)}{2m}\Delta t^2 ) ( v(t+\Delta t) = v(t) + \frac{F(t)+F(t+\Delta t)}{2m}\Delta t ) | O(Δt²) | Excellent (time-reversible, stable) | Production simulations |

The Velocity Verlet algorithm is widely employed in modern MD software due to its numerical stability and conservation properties [12]. It provides both positions and velocities at the same time point, making it particularly useful for simulations requiring thermodynamic monitoring.

Force Fields: Calculating Interactions in Particle Systems

Molecular mechanics force fields mathematically describe the potential energy surface of a molecular system. These force fields are fit to quantum mechanical calculations and experimental measurements [8].

Table 2: Components of Molecular Mechanics Force Fields

| Energy Component | Mathematical Formulation | Physical Description | Parameter Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Stretching | ( E{bond} = \sum{bonds} \frac{1}{2}kb(l - l0)^2 ) | Harmonic oscillator approximation for covalent bonds | Spectroscopy, QM calculations |

| Angle Bending | ( E{angle} = \sum{angles} \frac{1}{2}k\theta(\theta - \theta0)^2 ) | Resistance to bond angle deformation | QM calculations |

| Dihedral Torsion | ( E{dihedral} = \sum{dihedrals} k_\phi[1 + \cos(n\phi - \delta)] ) | Energy barrier for bond rotation | QM calculations, conformational energies |

| van der Waals | ( E{vdW} = \sum{i |

Lennard-Jones potential for non-bonded interactions | Gas-phase data, liquid properties |

| Electrostatic | ( E{elec} = \sum{i |

Coulomb's law for charged interactions | QM calculations, experimental dipole moments |

Recent advances include machine learning interatomic potentials that can accurately capture electrostatics and predict atomic charges while maintaining computational efficiency [7]. These next-generation force fields show promise for modeling complex interactions in drug delivery systems with improved accuracy.

MD Simulation Workflow: From Newton's Equations to Biological Insights

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for molecular dynamics simulations, from initial structure preparation to final analysis:

MD Simulation Workflow from Structure to Analysis

Initial System Setup

The basic ingredient for MD simulations is a protein structure coordinate file in PDB format [12]. The pdb2gmx command in GROMACS converts PDB files to MD-readable format while adding missing hydrogen atoms and generating molecular topology [12]. Periodic boundary conditions are applied to minimize edge effects on surface atoms by replicating the simulation box infinitely in all directions [12]. The system is then solvated with water molecules using the solvate command, and counter ions are added to neutralize the overall system charge [12].

Energy Minimization and Equilibration

Before production simulation, the system undergoes energy minimization to remove steric clashes and unfavorable contacts [12]. This is followed by equilibration phases where the system is gradually heated to the target temperature (typically 310 K for biological systems) and allowed to establish proper density and solvent orientation around solutes.

Production Simulation and Analysis

During production simulation, Newton's equations of motion are integrated at each time step to generate trajectory data containing atomic positions and velocities over time [12]. Specialized analysis tools then process these trajectories to compute thermodynamic, structural, and dynamic properties relevant to biological function or drug behavior.

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

The following table details essential materials and software solutions used in molecular dynamics simulations:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for MD Simulations

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Force Fields | AMBER, CHARMM, GROMOS, OPLS-AA | Define potential energy functions and parameters for different molecule types | Selection depends on system composition; AMBER often used for proteins, CHARMM for lipids |

| Simulation Software | GROMACS, NAMD, AMBER, OpenMM | Perform numerical integration of equations of motion and force calculations | GROMACS offers excellent performance on CPUs and GPUs; NAMD excels for large parallel systems |

| Visualization Tools | VMD, PyMOL, SAMSON, UCSF Chimera | Render molecular structures and trajectories; analyze structural features | VMD particularly strong for trajectory analysis; SAMSON provides advanced color palette tools [13] |

| Analysis Packages | MDTraj, MDAnalysis, GROMACS tools | Calculate properties from trajectories (RMSD, RMSF, hydrogen bonds, etc.) | Python-based tools (MDTraj) enable custom analysis pipelines |

| Enhanced Sampling Methods | Metadynamics, Umbrella Sampling, Replica Exchange | Accelerate rare events and improve conformational sampling | Essential for studying processes with high energy barriers (e.g., drug unbinding) |

Advanced visualization techniques play a vital role in facilitating the analysis and interpretation of molecular dynamics simulations [14]. Effective color palettes in molecular visualization are not merely decorative but encode meaning and guide perception, with HCL (Hue-Chroma-Luminance) models often providing more perceptually intuitive mappings than traditional HSV schemes [13].

Applications in Drug Delivery and Therapeutics

MD simulations have demonstrated particular utility in optimizing drug delivery systems for cancer therapy. Studies have investigated various nanocarriers including functionalized carbon nanotubes, chitosan-based nanoparticles, metal-organic frameworks, and human serum albumin complexes [9]. For example, simulations of anticancer drugs like Doxorubicin, Gemcitabine, and Paclitaxel encapsulated in nanocarriers have revealed molecular mechanisms that influence drug loading capacity, stability, and release profiles [9].

The integration of machine learning algorithms with molecular dynamics has enabled rapid emulation of photorealistic visualization styles and enhanced analysis of high-dimensional simulation data [14]. Deep learning techniques can embed complex molecular simulation data into lower-dimensional latent spaces that retain inherent molecular characteristics, facilitating pattern recognition and prediction of drug behavior [14].

Protocol for MD Simulations of Proteins

This section provides a detailed methodology for implementing molecular dynamics simulations based on established protocols [12]:

System Preparation

- Obtain protein coordinates from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (www.rcsb.org) and visually inspect using molecular visualization software (e.g., RasMol)

- Preprocess the structure by removing extraneous water molecules and explicitly defining ligand chemistry if present

- Generate molecular topology using the

pdb2gmxcommand:pdb2gmx -f protein.pdb -p protein.top -o protein.gro - Define simulation box using

editconfwith a minimum 1.0 Å distance from protein periphery:editconf -f protein.gro -o protein_editconf.gro -bt cubic -d 1.4 -c - Solvate the system using the

solvatecommand:grompp -f em.mdp -c protein_water -p protein.top -o protein_b4em.tprgenion -s protein_b4em.tpr -o protein_genion.gro -nn 3 -nq -1 -n index.ndx

Energy Minimization and Equilibration

- Perform energy minimization using the steepest descent or conjugate gradient algorithm until the maximum force falls below a specified threshold (typically 1000 kJ/mol/nm)

- Equilibrate the system in two phases:

- NVT ensemble (constant particle Number, Volume, and Temperature) for 100-500 ps

- NPT ensemble (constant particle Number, Pressure, and Temperature) for 100-500 ps

- Verify equilibration by monitoring stability of temperature, pressure, density, and potential energy

Production Simulation and Analysis

- Run production MD for timescales appropriate to the biological process of interest (typically nanoseconds to microseconds)

- Save trajectory frames at intervals sufficient to resolve relevant motions (typically every 10-100 ps)

- Analyze trajectories for properties such as:

- Root mean square deviation (RMSD) to assess structural stability

- Root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) to identify flexible regions

- Radius of gyration to measure compactness

- Hydrogen bonding patterns to determine interaction networks

- Validate simulations by comparing with experimental data when available (NMR, X-ray crystallography, cryo-EM)

Molecular dynamics simulations provide a powerful framework for solving Newton's equations of motion in complex particle systems, enabling atomic-level insights into biomolecular behavior and drug interactions. The core principles outlined in this guide—from numerical integration of Newton's equations to force field implementation and trajectory analysis—form the foundation for applying MD simulations in drug development and structural biology. As force fields continue to improve and computational resources expand, MD simulations will play an increasingly vital role in accelerating therapeutic development and understanding molecular mechanisms of disease. Future directions include more accurate machine learning potentials, enhanced sampling for longer timescales, and tight integration with experimental structural biology techniques.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation is a computer simulation method for analyzing the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time. By numerically solving Newton's equations of motion for a system of interacting particles, MD provides a dynamic view of system evolution, allowing researchers to study processes at an atomic scale that are often inaccessible to experimental observation. While MD has become a cornerstone technique in chemical physics, materials science, and biophysics, its origins trace back to a seemingly simple physics problem that challenged fundamental assumptions about statistical mechanics [15]. This article traces the historical pathway from the seminal Fermi-Pasta-Ulam (FPU) problem to the sophisticated biomolecular simulations that now drive advances in drug design and materials science, framing this evolution within the broader context of MD simulation research.

The Fermi-Pasta-Ulam Problem: A Paradoxical Beginning

The Original Experiment and Its Unexpected Results

In 1953, Enrico Fermi, John Pasta, Stanislaw Ulam, and Mary Tsingou conducted one of the earliest digital computer simulations on the MANIAC computer at Los Alamos National Laboratory. Their intent was to study how energy distriblates in a vibrating string that included a non-linear term [16]. They simulated a discrete system of nearest-neighbor coupled oscillators represented by the equations:

[ m\ddot{x}j = k(x{j+1} + x{j-1} - 2xj)[1 + \alpha(x{j+1} - x{j-1})] ]

where (x_j(t)) represents the displacement of the j-th particle from its equilibrium position, (m) is the mass, (k) is the linear force constant, and (\alpha) determines the strength of the nonlinear term [16].

Fermi and colleagues expected that the nonlinear interactions would lead to thermalization and ergodic behavior, where the initial vibrational mode would distribute its energy equally among all possible modes, consistent with the equipartition theorem of statistical mechanics. Surprisingly, their simulations revealed something entirely different: the system exhibited complicated quasi-periodic behavior, with energy recurring almost exactly to the initial state rather than equilibrating across modes [16]. This counterintuitive result became known as the Fermi-Pasta-Ulam-Tsingou (FPUT) recurrence paradox.

Methodological Framework of the FPUT Experiment

The original FPUT simulation employed specific computational parameters and methodologies that established patterns for future MD work:

Table 1: Computational Parameters of the Original FPUT Experiment

| Parameter | Specification | Role in Simulation |

|---|---|---|

| Computer | MANIAC I | Early digital computer at Los Alamos National Laboratory |

| System Type | Discrete nonlinear oscillators | Model of a vibrating string with nonlinear couplings |

| Nonlinear Terms | Quadratic, cubic, piecewise linear | Introduced anharmonicity to perturb the harmonic system |

| Initial Condition | Single mode excitation | Sinusoidal displacement of lowest frequency mode |

| Measurement | Energy distribution among modes | Tracked evolution toward expected thermalization |

Source: Adapted from FPUT original report [16]

The FPUT experiment was significant not only for its surprising results but also as one of the earliest uses of digital computers for mathematical research, establishing simulation as a valid methodology for investigating physical systems that resisted analytical solutions [16].

Scientific Implications and Historical Significance

The FPUT results challenged the foundational assumptions of statistical mechanics regarding thermalization in nonlinear systems. Instead of confirming ergodic behavior, the simulations demonstrated that nonlinear systems could exhibit remarkably structured and recurrent dynamics over substantial time periods [16]. This paradox launched entire fields of research, including nonlinear dynamics and chaos theory, while simultaneously demonstrating the power of computational simulation as a third pillar of scientific inquiry alongside theory and experiment.

The Evolution of Molecular Dynamics Methodology

Early Developments Following FPUT

In the years following the FPUT experiment, MD simulations expanded beyond the original simple oscillator chains to model more complex systems:

- 1957: Berni Alder and Thomas Wainwright simulated perfectly elastic collisions between hard spheres using an IBM 704 computer [15]

- 1964: Aneesur Rahman published landmark simulations of liquid argon using a Lennard-Jones potential, with calculated properties like self-diffusion coefficients comparing favorably with experimental data [15]

- 1970s: MD began to be applied to biochemical systems, particularly proteins and nucleic acids [15]

These developments established MD as a powerful tool for studying condensed matter systems, with the Lennard-Jones potential becoming one of the most frequently used intermolecular potentials [15].

Key Technical Advancements in MD Simulations

The evolution of MD methodology involved critical advancements that expanded its applicability to biomolecular systems:

Table 2: Key Technical Advancements in Molecular Dynamics

| Advancement | Time Period | Impact on Biomolecular Simulation |

|---|---|---|

| Force Fields | 1970s-present | Empirical potentials (AMBER, CHARMM, GROMOS) enabled realistic modeling of biomolecules |

| Integration Algorithms | 1960s-present | Verlet algorithm (1967) and variants enabled stable long-term integration |

| Periodic Boundary Conditions | 1960s-present | Efficient modeling of bulk systems with limited particles |

| Constraint Algorithms | 1970s-present | SHAKE (1977) allowed longer timesteps by constraining fast vibrations |

| Parallel Computing | 1990s-present | Enabled simulation of larger systems for longer timescales |

| Enhanced Sampling | 1990s-present | Techniques like replica exchange improved conformational sampling |

Source: Adapted from MD historical review [15]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Components of Modern MD

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Biomolecular MD Simulations

| Component | Function | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Force Fields | Define potential energy functions describing atomic interactions | AMBER, CHARMM, GROMOS [1] |

| Software Packages | Implement integration algorithms and force calculations | GROMACS, DESMOND, AMBER, NAMD [1] [17] |

| Solvent Models | Represent water and solvent environments | TIP3P, SPC/E, implicit solvent [15] |

| Enhanced Sampling Methods | Accelerate rare events and improve conformational sampling | Replica exchange, metadynamics, umbrella sampling [18] |

Modern Biomolecular Simulation: Applications and Protocols

MD in Drug Design and Medicinal Chemistry

Molecular dynamics has become an indispensable tool in modern drug design, providing insights that complement experimental approaches. MD simulations help refine three-dimensional structures of protein targets, study recognition patterns of ligand-protein complexes, and identify structural cavities for designing novel therapeutic compounds with higher affinity [17]. Unlike static docking procedures, MD incorporates biological conditions that include structural motions, leading to more reliable predictions of binding affinities and mechanisms [17].

Specific applications in drug design include:

- Pharmacophore development: MD simulations of protein-ligand complexes can identify critical binding interactions and conserved binding regions for pharmacophore modeling [15]

- Binding free energy calculations: Advanced sampling and free energy methods provide quantitative predictions of drug-receptor affinity [15]

- Drug solubility and solvation: MD computes thermodynamic properties relevant to pharmaceutical development [15]

Protocol for Protein-Ligand Binding Analysis

A typical MD protocol for studying drug-receptor interactions involves:

System Preparation

- Obtain 3D structures from PDB or homology modeling

- Parameterize ligand using appropriate force fields

- Solvate the protein-ligand complex in explicit water molecules

- Add ions to neutralize system charge

Simulation Parameters

- Integration timestep: 1-2 femtoseconds

- Temperature: 300K using thermostats (e.g., Nosé-Hoover)

- Pressure: 1 bar using barostats (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman)

- Non-bonded interactions: Particle Mesh Ewald for electrostatics

- Constraints: SHAKE or LINCS for bonds involving hydrogen

Simulation Stages

- Energy minimization: Remove bad contacts

- Equilibration: Gradual heating and density equilibration

- Production run: Generate trajectory for analysis (typically nanoseconds to microseconds)

Analysis Methods

- Root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) to assess stability

- Root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) to identify flexible regions

- Hydrogen bonding analysis

- MM/PBSA or MM/GBSA for binding free energies

- Principal component analysis to identify essential dynamics

MD in Energy Materials and Polymer Design

Beyond biomedical applications, MD simulations have become crucial for designing advanced materials. In polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cells (PEMFCs), MD helps investigate critical structural and transport phenomena at the molecular level, addressing challenges related to performance degradation and material costs [4]. Research themes include catalyst and carbon support architecture, structural analysis of ionomer and water clusters, mass transfer, thermal conductivity, and mechanical properties [4].

Similarly, MD guides the design of oil-displacement polymers for enhanced oil recovery (EOR), where simulations help elucidate polymer-oil interactions at the atomic scale and predict how polymer wettability changes affect recovery efficiency [3]. These applications demonstrate how MD bridges fundamental molecular interactions with macroscopic material properties.

Evolution of MD Research Focus

Current Frontiers and Future Directions

Integration of Machine Learning with MD

The integration of machine learning (ML) with molecular dynamics represents one of the most promising frontiers in computational molecular science. ML approaches are addressing two fundamental challenges in MD simulations: the accuracy of force fields and limitations in simulation timescales [18].

Machine Learning Force Fields (MLFFs) leverage neural networks trained on quantum mechanical calculations to achieve quantum-level accuracy at classical MD computational costs, enabling large-scale simulations of complex aqueous and interfacial systems with thousands of atoms for nanosecond timescales [18]. Simultaneously, ML-enhanced sampling methods facilitate the crossing of large energy barriers and exploration of extensive configuration spaces, making the calculation of high-dimensional free energy surfaces feasible for understanding complex chemical reactions [18].

Multiscale Simulation and High-Performance Computing

Future research directions focus on developing multiscale simulation methodologies that bridge quantum, classical, and continuum descriptions of matter [3]. The exploration of high-performance computing technologies, including exascale computing and specialized hardware, aims to push MD simulations toward larger systems and longer timescales, potentially reaching the millisecond range for complex biomolecules [3] [18]. Integration of experimental data with simulation through approaches like cryo-EM guided MD and NMR refinement enhances the experimental relevance of computational predictions [4].

Emerging Applications in Complex Systems

MD simulations are expanding into increasingly complex and biologically relevant systems:

- Whole virus simulations model complete viral particles with atomic detail [17]

- Cellular component simulations approach subcellular scale complexity

- Polymer composite materials guide the development of environmentally friendly technologies [3]

- Aroma compound encapsulation optimize cyclodextrin inclusion complexes for controlled release [19]

Modern Biomolecular MD Workflow

The journey from the Fermi-Pasta-Ulam problem to modern biomolecular simulation exemplifies how a fundamental investigation into nonlinear systems unexpectedly launched an entire computational methodology that now permeates molecular science. What began as a specialized inquiry into energy distribution in simple oscillator chains has evolved into a sophisticated toolkit that provides atomic-level insights into protein folding, drug-receptor interactions, material design, and complex chemical processes. As MD simulations continue to advance through integration with machine learning, enhanced sampling algorithms, and exascale computing, they promise to tackle even more challenging problems in molecular science and engineering, maintaining their crucial role at the intersection of computational and experimental science.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation has emerged as an indispensable tool in computational chemistry, biophysics, and materials science, enabling researchers to investigate the time-dependent behavior of atomic and molecular systems at an unprecedented level of detail. This computational methodology solves Newton's equations of motion for a system of interacting particles, allowing scientists to observe thermodynamic processes, conformational changes, and interaction pathways that are often inaccessible to experimental techniques. The foundation of any MD simulation rests upon three interconnected pillars: force fields that mathematically describe interatomic interactions, potential energy functions that quantify system energetics, and numerical integration algorithms that propagate the system through time. The accurate integration of these components enables the faithful reproduction of physical behavior, making MD a powerful predictive tool in fields ranging from drug discovery to nanomaterials design. This technical guide examines the core theoretical concepts underlying molecular dynamics simulations, with particular emphasis on their practical implementation and recent applications in biomedical research, especially in the development of novel cancer therapeutics.

Force Fields in Molecular Dynamics

In the context of chemistry and molecular modeling, a force field refers to a computational model that describes the forces between atoms within molecules or between molecules [20]. More precisely, a force field comprises the functional forms and parameter sets used to calculate the potential energy of a system of interacting atoms or molecules. Force fields essentially define the "rules of interaction" for a molecular system, serving as the fundamental framework that determines how atoms attract and repel each other throughout a simulation [20].

Force fields utilize the same conceptual foundation as force fields in classical physics, with the distinction that their parameters describe the energy landscape at the atomistic level. From this potential energy function, the forces acting on every particle are derived as the negative gradient of the potential energy with respect to particle coordinates: (\vec{F} = -\nabla U(\vec{r})) [20] [21]. These forces are then used to compute atomic accelerations via Newton's second law, enabling the simulation of molecular motion over time.

Classification of Force Fields

Force fields can be categorized according to several criteria, including their parametrization strategy, physical structure, and mathematical complexity:

Component-specific vs. Transferable: Component-specific force fields are developed solely for describing a single substance, while transferable force fields design parameters as building blocks applicable to different substances [20].

All-atom vs. United-atom vs. Coarse-grained: All-atom force fields provide parameters for every atom, including hydrogen. United-atom potentials treat hydrogen and carbon atoms in methyl groups and methylene bridges as single interaction centers. Coarse-grained potentials sacrifice chemical details for computational efficiency and are often used in long-time simulations of macromolecules [20].

Class-based hierarchy: Class I force fields use simple harmonic approximations for bonds and angles; Class II incorporate anharmonic terms and cross-terms; Class III explicitly include special effects like polarization and stereoelectronic effects [21].

Table 1: Force Field Classification and Characteristics

| Classification Basis | Force Field Type | Key Characteristics | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parametrization Strategy | Component-specific | Developed for a single substance | Water models |

| Transferable | Parameters designed as reusable building blocks | Alkane force fields | |

| Physical Resolution | All-atom | Explicit parameters for all atoms, including hydrogen | CHARMM, AMBER |

| United-atom | Hydrogen and carbon atoms grouped in methyl/methylene groups | Early versions of GROMOS | |

| Coarse-grained | Multiple atoms represented as single interaction sites | MARTINI | |

| Mathematical Complexity | Class I | Harmonic bonds/angles, no cross-terms | AMBER, CHARMM, GROMOS |

| Class II | Anharmonic terms, cross-terms | MMFF94, UFF | |

| Class III | Explicit polarization, special effects | AMOEBA, DRUDE |

Functional Form of Molecular Force Fields

The basic functional form for the potential energy in molecular force fields typically includes intramolecular terms for atoms linked by covalent bonds and intermolecular terms for non-bonded interactions [20]. The total potential energy in an additive force field can be expressed as:

[ E{\text{total}} = E{\text{bonded}} + E_{\text{nonbonded}} ]

where:

[ E{\text{bonded}} = E{\text{bond}} + E{\text{angle}} + E{\text{dihedral}} ]

[ E{\text{nonbonded}} = E{\text{electrostatic}} + E_{\text{van der Waals}} ]

This decomposition reflects the physical understanding that covalent bonds, bond angles, and torsional angles primarily govern molecular structure, while electrostatic and van der Waals interactions determine how molecules pack and recognize each other [20].

Potential Energy Functions

The potential energy function represents the mathematical heart of a force field, quantifying how the system's energy changes with atomic positions. These functions consist of multiple terms that capture different aspects of molecular interactions.

Bonded Interactions

Bonded interactions describe the energy associated with covalent connectivity between atoms and include bond stretching, angle bending, and torsional potentials.

Bond Stretching

The energy associated with stretching or compressing chemical bonds from their equilibrium length is most commonly represented by a harmonic potential:

[ E{\text{bond}} = \frac{k{ij}}{2}(l{ij} - l{0,ij})^2 ]

where (k{ij}) is the force constant, (l{ij}) is the actual bond length, and (l_{0,ij}) is the equilibrium bond length between atoms (i) and (j) [20]. Although this simple harmonic approximation works well near equilibrium bond lengths, more sophisticated approaches like the Morse potential provide better description at higher stretching and enable bond breaking, which is essential for reactive force fields [20].

Angle Bending

The energy required to bend bond angles from their equilibrium values is similarly described by a harmonic potential:

[ E{\text{angle}} = \frac{k{\theta}}{2}(\theta{ijk} - \theta0)^2 ]

where (k{\theta}) is the angle force constant, (\theta{ijk}) is the actual angle between atoms (i-j-k), and (\theta_0) is the equilibrium angle [21]. The force constants for angle deformation are typically about five times smaller than those for bond stretching, reflecting the relative ease of bending compared to bond stretching [21].

Torsional Potentials

Torsional potentials describe the energy associated with rotation around chemical bonds, which plays a crucial role in determining molecular conformation. This term is typically represented by a periodic function:

[ E{\text{dihedral}} = k{\phi}(1 + \cos(n\phi - \delta)) ]

where (k_{\phi}) is the torsional force constant, (n) is the periodicity (number of minima/maxima in 360°), (\phi) is the torsional angle, and (\delta) is the phase shift [21]. Multiple such terms with different periodicities are often summed to create complex torsional profiles.

Improper Dihedrals

Improper dihedral potentials are used to maintain structural features such as planarity in aromatic rings or defined chiral centers:

[ E{\text{improper}} = k{\phi}(\phi - \phi_0)^2 ]

where (\phi) is the improper dihedral angle and (\phi_0) is its equilibrium value [21]. Unlike proper dihedrals, improper dihedrals typically employ a harmonic functional form.

Non-Bonded Interactions

Non-bonded interactions occur between atoms that are not directly connected by covalent bonds and typically represent the most computationally intensive component of force field calculations.

Van der Waals Interactions

Van der Waals interactions capture short-range repulsion due to overlapping electron clouds and longer-range dispersion attractions. The most common representation is the Lennard-Jones 12-6 potential:

[ E_{\text{vdW}} = 4\epsilon \left[ \left(\frac{\sigma}{r}\right)^{12} - \left(\frac{\sigma}{r}\right)^{6} \right] ]

where (\epsilon) is the potential well depth, (\sigma) is the finite distance at which the interparticle potential is zero, and (r) is the interatomic distance [20] [21]. The (r^{-12}) term describes repulsive forces, while the (r^{-6}) term describes attractive dispersion forces.

An alternative to the Lennard-Jones potential is the Buckingham potential, which replaces the (r^{-12}) repulsive term with an exponential function:

[ E_{\text{Buckingham}} = A\exp(-Br) - \frac{C}{r^6} ]

where (A), (B), and (C) are parameters specific to the atom pair [21]. While this provides a more realistic description of electron density, it carries a risk of "Buckingham catastrophe" at very short distances where the exponential repulsion fails to grow fast enough [21].

Electrostatic Interactions

Electrostatic interactions between charged atoms are described by Coulomb's law:

[ E{\text{electrostatic}} = \frac{1}{4\pi\varepsilon0} \frac{qi qj}{r_{ij}} ]

where (qi) and (qj) are the partial charges on atoms (i) and (j), (r{ij}) is the distance between them, and (\varepsilon0) is the vacuum permittivity [20]. The assignment of atomic charges remains one of the most challenging aspects of force field development, often employing heuristic approaches that can lead to significant variations in how specific properties are represented [20].

Combining Rules

For van der Waals interactions between different atom types, combining rules avoid the need for explicit parameters for every possible pair:

Table 2: Common Combining Rules for Non-Bonded Interactions

| Combining Rule | Formulation | Used In |

|---|---|---|

| Geometric Mean | (\sigma{ij} = \sqrt{\sigma{ii}\sigma{jj}}), (\epsilon{ij} = \sqrt{\epsilon{ii}\epsilon{jj}}) | GROMOS |

| Lorentz-Berthelot | (\sigma{ij} = \frac{\sigma{ii} + \sigma{jj}}{2}), (\epsilon{ij} = \sqrt{\epsilon{ii}\epsilon{jj}}) | CHARMM, AMBER |

| Waldman-Hagler | (\sigma{ij} = \left(\frac{\sigma{ii}^6 + \sigma{jj}^6}{2}\right)^{1/6}), (\epsilon{ij} = \sqrt{\epsilon{ii}\epsilon{jj}} \frac{2\sigma{ii}^3\sigma{jj}^3}{\sigma{ii}^6 + \sigma{jj}^6}) | Noble gases |

Specialized Force Fields

For specific materials, standard molecular force fields may be insufficient. Covalent crystals often require bond order potentials like Tersoff potentials, while metal systems typically use embedded atom models [20]. Polarizable force fields represent a significant advancement beyond standard fixed-charge models, explicitly accounting for electronic polarization effects through various approaches:

- Drude Oscillators: Massless charged particles attached to atoms via harmonic springs (used in CHARMM-Drude, OPLS5) [21]

- Inducible Point Dipoles: Used in the AMOEBA force field [21]

- Fluctuating Charges: Models polarization as charge transfer between atoms [21]

- Gaussian Electrostatic Models: Uses Gaussian charge densities with AMOEBA polarization [21]

Numerical Integration Algorithms

At its core, molecular dynamics simulation involves solving Newton's second law of motion for each atom in the system:

[ \vec{F}i = mi \frac{d^2\vec{r}_i}{dt^2} ]

where (\vec{F}i) is the force acting on atom (i), (mi) is its mass, and (\vec{r}_i) is its position [22]. The force can be computed from the derivative of the potential energy with respect to atomic coordinates:

[ \vec{F}i = -\frac{\partial V}{\partial \vec{r}i} ]

Since analytical solutions are impossible for complex many-body systems, finite difference methods are employed to numerically integrate these equations of motion [22].

Criteria for Effective Integrators

Effective integration algorithms for molecular dynamics must satisfy several criteria [22]:

- Computational Efficiency: Ideally requiring only one energy evaluation per timestep

- Minimal Memory Requirements: Important for large systems

- Permit Reasonably Long Timesteps: To reach biologically relevant timescales

- Good Energy Conservation: Essential for generating correct statistical ensembles

Common Integration Schemes

Verlet Algorithms

The Verlet algorithm and its variants are perhaps the most widely used integration methods in molecular dynamics due to their favorable balance of accuracy, stability, and computational efficiency [22].

The Verlet leapfrog algorithm calculates positions and velocities as follows:

[ \vec{v}(t + \Delta t/2) = \vec{v}(t - \Delta t/2) + \Delta t \cdot \vec{a}(t) ] [ \vec{r}(t + \Delta t) = \vec{r}(t) + \Delta t \cdot \vec{v}(t + \Delta t/2) ]

where positions and velocities are half a timestep out of synchrony [22]. This method requires only one energy evaluation per step but suffers from the disadvantage that positions and velocities are not known at the same time.

The Verlet velocity algorithm overcomes this limitation:

[ \vec{r}(t + \Delta t) = \vec{r}(t) + \Delta t \cdot \vec{v}(t) + \frac{\Delta t^2}{2} \cdot \vec{a}(t) ] [ \vec{v}(t + \Delta t/2) = \vec{v}(t) + \frac{\Delta t}{2} \cdot \vec{a}(t) ]

Compute forces and accelerations at (t + \Delta t) using the new positions, then:

[ \vec{v}(t + \Delta t) = \vec{v}(t + \Delta t/2) + \frac{\Delta t}{2} \cdot \vec{a}(t + \Delta t) ]

This approach provides positions and velocities at the same instant while maintaining the excellent stability and energy conservation properties of the leapfrog method [22].

Other Integration Methods

Adams-Bashforth-Moulton fourth order (ABM4) is a predictor-corrector method that offers higher accuracy at the cost of requiring two energy evaluations per step and storage of information from previous steps [22]. As a fourth-order method, its truncation error is proportional to the fifth power of the timestep, but it is not self-starting, requiring another method (typically Runge-Kutta) to generate the first three steps.

The Runge-Kutta fourth-order method is a robust, self-starting algorithm that can handle stiff equations but requires four energy evaluations per step, making it computationally prohibitive for most molecular dynamics applications [22].

Table 3: Comparison of Molecular Dynamics Integration Algorithms

| Algorithm | Order | Energy Evaluations per Step | Memory Requirements | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Verlet Leapfrog | 2nd | 1 | Low | Simple, efficient, good energy conservation | Positions/velocities out of sync |

| Verlet Velocity | 2nd | 1 | Low | Positions/velocities synchronized, stable | Slightly more complex than leapfrog |

| ABM4 | 4th | 2 | Moderate | Higher accuracy | Not self-starting, requires previous steps |

| Runge-Kutta-4 | 4th | 4 | Low | Robust, self-starting | Computationally expensive |

Timestep Considerations

The choice of timestep represents a critical compromise between numerical stability and computational efficiency. Typical timesteps for biomolecular simulations range from 1-2 femtoseconds when bonds involving hydrogen atoms are constrained [23]. Research has shown that standard step size values used at present may be lower than necessary for accurate sampling, suggesting potential for efficiency improvements [23].

Force Field Parameterization

The development of accurate force field parameters is crucial for the reliability of molecular dynamics simulations. Parameterization strategies can be broadly categorized into two approaches: using data from the atomistic level (quantum mechanical calculations or spectroscopic data) or using macroscopic property data [20]. Often, a combination of these routes is employed.

Typical parameter sets include values for atomic mass, atomic charge, Lennard-Jones parameters for every atom type, and equilibrium values of bond lengths, bond angles, and dihedral angles, along with their associated force constants [20]. The parameterization of biological macromolecules often derives parameters from observations of small organic molecules, which are more accessible to experimental studies and quantum calculations [20].

Recent efforts have focused on automating parameterization procedures to reduce subjectivity and improve reproducibility, though fully automated approaches risk introducing inconsistencies, particularly in atomic charge assignment [20]. Several databases have emerged to collect and categorize force fields, including:

- openKIM: Focuses on interatomic functions describing individual interactions between specific elements [20]

- TraPPE: Contains transferable force fields for organic molecules [20]

- MolMod: Includes molecular and ionic force fields, both component-specific and transferable [20]

Visualization of Molecular Dynamics Framework

The following diagram illustrates the integrated relationship between force fields, potential energy functions, and numerical integration in molecular dynamics simulations:

MD Simulation Framework

Research Applications and Protocols

Molecular dynamics simulations have found particularly valuable applications in drug delivery research for cancer treatment, where they provide atomic-level insights into drug-carrier interactions that are difficult to obtain experimentally [9]. MD simulations have emerged as a vital tool in optimizing drug delivery systems, offering detailed understanding of drug encapsulation, stability, and release processes [9].

Protocol for Drug Delivery System Analysis

A typical MD-based investigation of drug delivery systems involves the following methodological steps:

System Preparation: Construction of the drug carrier (e.g., functionalized carbon nanotubes, chitosan nanoparticles, metal-organic frameworks) and drug molecules using molecular modeling tools [9] [24].

Solvation and Neutralization: Placement of the drug-carrier system in an explicit solvent environment, typically water, with addition of ions to achieve physiological concentration and system neutrality [24].

Energy Minimization: Removal of steric clashes and bad contacts through steepest descent or conjugate gradient minimization algorithms [22].

System Equilibration: Gradual heating to target temperature (typically 310 K for biological systems) with position restraints on the drug-carrier complex, followed by equilibrium MD without restraints [22].

Production Simulation: Extended MD simulation (typically tens to hundreds of nanoseconds) with appropriate thermodynamic ensemble (NPT or NVT) to study drug-carrier interactions [9].

Trajectory Analysis: Calculation of interaction energies, hydrogen bonding, root-mean-square deviation, and other observables to quantify drug-carrier interactions and stability [21].

Case Studies in Cancer Therapeutics

Recent research has demonstrated the power of MD simulations in optimizing delivery systems for various anticancer drugs:

Doxorubicin (DOX): Simulations have revealed interaction mechanisms with functionalized carbon nanotubes (FCNTs), which exhibit high drug-loading capacity and stability [9].

Gemcitabine (GEM): MD studies have investigated encapsulation in biocompatible carriers like human serum albumin (HSA) and chitosan, favored for their biodegradability and reduced toxicity [9].

Paclitaxel (PTX): Simulations have helped optimize controlled release mechanisms from various nanocarriers, improving drug solubility and bioavailability [9].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools in Molecular Dynamics

| Reagent/Tool | Type | Function/Purpose | Examples/Alternatives |

|---|---|---|---|

| Force Fields | Software Parameters | Define interaction potentials between atoms | CHARMM, AMBER, GROMOS, OPLS [20] [21] |

| Simulation Packages | Software | Perform numerical integration of equations of motion | CHARMM, NAMD, GROMACS, AMBER, OpenMM [24] |

| System Building Tools | Software | Prepare molecular systems for simulation | CHARMM-GUI, MDWeb [24] [25] |

| Analysis Tools | Software | Process trajectory data to extract observables | GROMACS analysis tools, VMD, MDWeb analysis modules [21] [25] |

| Drug Compounds | Molecular Entities | Active pharmaceutical ingredients studied | Doxorubicin, Gemcitabine, Paclitaxel [9] |

| Nanocarriers | Molecular Entities | Drug delivery vehicles | Functionalized carbon nanotubes, chitosan nanoparticles, metal-organic frameworks [9] |

Force fields, potential energy functions, and numerical integration algorithms constitute the essential foundation of molecular dynamics simulations. The continued refinement of force field parameters, particularly through the incorporation of polarization effects and improved parametrization methodologies, has significantly enhanced the predictive power of MD simulations. Concurrent advances in integration algorithms and computational efficiency have enabled the investigation of increasingly complex biological processes at relevant timescales. In the context of drug delivery research, MD simulations have proven particularly valuable in elucidating molecular-level interactions between therapeutic compounds and their carrier systems, guiding the rational design of more effective nanomedicines. As force field development continues to evolve alongside advances in high-performance computing and machine learning techniques, molecular dynamics simulations are poised to play an increasingly central role in accelerating the development of next-generation therapeutics and materials.

The ergodicity hypothesis is a foundational concept in statistical mechanics, asserting that the time average of a system's property over a sufficiently long period equals its ensemble average—the average over all possible microscopic states at a given energy [26]. This principle provides the crucial link between the microscopic dynamics of atoms and molecules and the macroscopic thermodynamic properties we observe.

Within molecular dynamics (MD) research, this hypothesis underpins the entire simulation methodology. MD simulations predict how every atom in a biomolecular system will move over time based on physics governing interatomic interactions [8]. By tracking atomic trajectories, MD allows computation of time-averaged properties that, according to ergodicity, should represent measurable ensemble-averaged quantities—enabling researchers to connect simulated dynamics with experimental observables [26] [8].

Theoretical Foundations of Ergodicity

Historical Development and Statistical Framework

The theoretical framework of statistical mechanics was established in the 19th century by Boltzmann and Gibbs. Boltzmann postulated that macroscopic phenomena result from time averages of microscopic events along particle trajectories. Gibbs further developed this concept, demonstrating that time averages could be replaced by ensemble averages—averages over a collection of systems in different microscopic states but with identical macroscopic constraints [26].

This framework initially considered two characteristic times: the fast time scale of individual atomic motions (e.g., vibrations) and the slow time scale of macroscopic observations. However, many biological processes—such as chemical reactions and protein conformational changes—require introduction of a third, intermediate time scale: long enough for the reaction or conformational transition to occur, yet short compared to the system's final equilibration time [26].

The Mathematical Formalism

In formal terms, for a system property (A), the ergodic hypothesis states:

[ \langle A \rangle{\text{time}} = \lim{T \to \infty} \frac{1}{T} \int0^T A(t) \, dt = \langle A \rangle{\text{ensemble}} = \int A(\Gamma) \rho(\Gamma) \, d\Gamma ]

where (\langle A \rangle{\text{time}}) is the time average, (\langle A \rangle{\text{ensemble}}) is the ensemble average, (\Gamma) represents a point in phase space, and (\rho(\Gamma)) is the probability density of the ensemble.

In MD simulations, this equivalence enables researchers to compute thermodynamic properties from atomic trajectories. For instance, the average potential energy from a simulation should correspond to the ensemble-average potential energy for that thermodynamic state [26].

Ergodicity in Molecular Dynamics Methodology

Foundations of Molecular Dynamics Simulations

MD simulations apply Newton's laws of motion to molecular systems. Given initial atomic positions, forces are calculated based on interatomic interactions, allowing prediction of atomic trajectories through numerical integration. The resulting data captures structural and dynamic evolution of the system at femtosecond resolution [8].

The connection to ergodicity emerges through the sampling strategy: as the simulation progresses through consecutive states, it (ideally) explores the relevant regions of phase space, with time averages converging to ensemble averages. This makes MD a powerful tool for studying biomolecular processes, including conformational changes, ligand binding, and protein folding [8].

Figure 1: The Molecular Dynamics Workflow and Ergodicity. MD simulations iteratively calculate forces and integrate equations of motion to generate trajectories. According to the ergodic hypothesis, time averages from these trajectories equal ensemble averages of thermodynamic properties [26] [8].

Practical Considerations and Sampling Challenges

While ergodicity assumes adequate phase space sampling, practical MD simulations face significant challenges. Biomolecular systems often exhibit rough energy landscapes with high barriers separating metastable states. On accessible simulation timescales (nanoseconds to microseconds), systems may remain trapped in local minima, violating ergodic assumptions [8].

Recent specialized hardware has enabled millisecond-scale simulations for some systems, but timescales for many biologically important processes (e.g., protein folding) remain challenging. This has motivated development of enhanced sampling techniques that accelerate exploration of phase space while preserving thermodynamic accuracy [8].

Testing Ergodicity in Protein Systems

Current Research and Debates

The validity of ergodicity in biomolecular systems remains an active research area. A January 2025 pre-print investigates non-ergodicity in protein dynamics using all-atom MD simulations across picosecond to nanosecond timescales [27]. This study employed widely used statistical tools to examine whether previously reported non-ergodic behavior resulted from genuine physical phenomena or incomplete convergence.

Contrary to some earlier suggestions, these findings indicate that apparent deviations from ergodic behavior likely stem from inadequate sampling rather than fundamental breakdown of the ergodic hypothesis—at least on the timescales studied. The authors note, however, that ergodicity breaking might still occur over longer timescales not directly investigated in their work [27].

Methodologies for Assessing Ergodicity

Researchers employ various statistical measures to test ergodic behavior in MD simulations:

- Mean-squared displacement analysis tracks particle diffusion over time

- Autocorrelation functions quantify how quickly properties decorrelate

- Edwards-Anderson order parameters distinguish conformational substates

- Potential of Mean Force (PMF) calculations identify free energy barriers

Convergence is typically assessed by running multiple independent simulations and comparing time-averaged properties across replicates. Persistent discrepancies suggest inadequate sampling or genuine ergodicity breaking [27].

Implications for Drug Discovery and Biomolecular Engineering

The ergodicity hypothesis has profound practical implications for pharmaceutical research and protein engineering. When valid, it enables:

Binding Affinity Calculations

Drug binding represents a classic rare event where ligands and receptors must sample numerous configurations before adopting bound conformations. Ergodicity allows estimation of binding free energies from sufficiently long simulations that sample both bound and unbound states [8].

Allosteric Mechanism Elucidation

Allosteric regulation involves correlated motions across protein domains. MD simulations can reveal these dynamics, with ergodic averaging connecting simulated fluctuations to experimental observables such as NMR order parameters [8].

Protein Design and Optimization

Engineering proteins with novel functions requires understanding sequence-structure-dynamics relationships. Ergodic sampling in MD enables computational screening of conformational landscapes for designed variants, guiding experimental implementations [8].

Quantitative Requirements for Ergodicity in MD

Table 1: Key Quantitative Parameters for Assessing Ergodicity in Biomolecular Simulations

| Parameter | Target Value/Range | Application Context | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simulation Length | >10× system relaxation time | General requirement | Must exceed longest relevant timescale |

| Replica Count | ≥3 independent trajectories | Convergence testing | Ensverages are reproducible |

| Potential of Mean Force Barrier | <6 (k_BT) for crossing in μs | Rare event sampling | Lower barriers improve ergodicity |

| RMSD Plateau | Stable within 1-2 Å | Conformational sampling | Suggests adequate basin exploration |

| Property Fluctuation | <5% variation across replicas | Convergence metric | Indicates sufficient sampling |

Experimental Protocols for Ergodicity Assessment

Standard MD Protocol for Protein Systems

A peer-reviewed protocol for MD simulations of proteins provides a reproducible methodology [12]:

System Preparation

- Obtain protein coordinates from PDB (http://www.rcsb.org/)

- Generate molecular topology using

pdb2gmx -f protein.pdb -p protein.top -o protein.gro - Select appropriate force field (e.g.,

ffG53A7for proteins with explicit solvent)

Simulation Box Setup

- Define periodic boundary conditions:

editconf -f protein.gro -o protein_editconf.gro -bt cubic -d 1.4 -c - Solvate system:

gmx solvate -cp protein_editconf.gro -p protein.top -o protein_water.gro - Add counterions to neutralize charge:

genion -s protein_b4em.tpr -o protein_genion.gro -nn 3 -nq -1

- Define periodic boundary conditions:

Energy Minimization and Equilibration

- Perform energy minimization using steepest descent

- Equilibrate with position restraints on protein heavy atoms

- Conduct unrestrained equilibration in NVT and NPT ensembles

Production Simulation

- Run extended MD simulation with 2-fs time steps

- Maintain temperature and pressure using appropriate thermostats and barostats

- Save coordinates every 10-100 ps for analysis

Enhanced Sampling Techniques

When standard MD fails to achieve ergodic sampling, specialized methods can help:

- Replica Exchange MD: Parallel simulations at different temperatures enhance barrier crossing

- Metadynamics: History-dependent biases discourage revisiting sampled states

- Accelerated MD: Lower energy barriers to increase transition rates

- Variational Enhanced Sampling: Optimize biases using neural networks

These approaches make ergodic sampling feasible for systems with high free energy barriers [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Dynamics Simulations

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Purpose | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Force Fields | Define interatomic interaction potentials | GROMACS ffG53A7 for protein simulations [12] |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | Numerical integration of equations of motion | GROMACS suite v5.1+ [12] |

| Visualization Tools | Structural analysis and rendering | RasMol for molecular visualization [12] |

| Specialized Hardware | Accelerate computationally intensive calculations | GPU clusters for enhanced simulation speed [8] |

| Analysis Packages | Process trajectory data and calculate properties | Grace for 2D plotting and visualization [12] |

Figure 2: Ergodicity Assessment Workflow in MD Research. This diagram outlines the process for validating ergodic sampling in molecular dynamics simulations, including the potential application of enhanced sampling techniques when standard MD fails to achieve adequate phase space exploration [12].

Future Perspectives and Challenges

While the ergodic hypothesis remains central to molecular simulation interpretation, several frontiers demand attention:

Timescale Limitations: Many biologically important processes (e.g., protein folding, large conformational changes) occur on timescales still challenging for MD, potentially leading to ergodicity breaking [27].

Force Field Accuracy: Imperfections in molecular mechanics force fields may create artificial energy barriers or incorrect basin depths, distorting sampling and thermodynamic averages [8].

Advanced Sampling Algorithms: Continued development of methods like variational free energy perturbation and AI-assisted sampling promises to extend the reach of ergodic sampling for complex biomolecular systems [26].

Validation Methodologies: Standardized metrics and protocols for assessing ergodicity across different biomolecular systems would strengthen confidence in simulation-derived thermodynamic properties [28].

As MD simulations continue evolving through hardware advances and algorithmic innovations, the practical realization of ergodic sampling will expand, further solidifying the role of molecular dynamics as an indispensable tool for connecting molecular-level interactions with macroscopic observables in drug discovery and biomolecular engineering [26] [8].

MD in Action: Methodologies, Software, and Cutting-Edge Applications in Biomedicine

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have emerged as an indispensable computational microscope in biomedical research, providing atomic-level insight into the behavior of proteins and other biomolecules over time [1] [8]. By numerically solving Newton's equations of motion, MD simulations capture the dynamic processes that are critical to understanding biological function and guiding drug discovery, phenomena that are often difficult or impossible to observe experimentally [29] [8]. This technical guide outlines the comprehensive workflow for conducting MD simulations, from initial system preparation through production simulation and trajectory analysis, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a structured methodology for implementing this powerful technique.

At its core, an MD simulation predicts the movement of every atom in a molecular system over time based on a physical model of interatomic interactions [8]. The simulation calculates forces between atoms using a molecular mechanics force field and uses these forces to update atomic positions and velocities, typically in femtosecond (10⁻¹⁵ s) time steps [29]. This process generates a trajectory that essentially constitutes a "movie" of the atomic-level configuration throughout the simulated time interval [8]. The value of MD simulations in drug discovery has expanded dramatically, as they can reveal functional mechanisms of proteins, uncover structural bases for disease, and assist in the design and optimization of small molecules, peptides, and proteins [30] [8].

Molecular Dynamics Simulation Workflow

The complete MD simulation process involves multiple stages, each with specific objectives and methodologies. The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow from initial setup through analysis:

Initial System Setup

Initial Structure Preparation

Every MD simulation begins with preparing the initial atomic coordinates of the target system [31]. For proteins, experimental structures are commonly obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB), while small organic molecules can be sourced from databases such as PubChem or ChEMBL [31]. The initial structure often requires careful preprocessing before simulation. This typically involves removing non-protein atoms such as water molecules, ions, and co-factors, as automatic topology construction generally only succeeds if all components of the structure are recognized by the force field [32]. For novel molecular systems not available in databases, initial structures may need to be built from scratch based on experimental data or theoretical predictions, with emerging generative AI tools like AlphaFold2 offering powerful structure prediction capabilities [31].

Force Field Selection

The force field represents the mathematical model that describes the potential energy of the molecular system as a function of atomic coordinates [29]. It includes terms for bonded interactions (bonds, angles, dihedrals) and non-bonded interactions (electrostatics, van der Waals) [29]. The selection of an appropriate force field is crucial, as it significantly influences the reliability of simulation outcomes [1]. Widely adopted force fields used in popular MD software packages include:

Table 1: Common Force Fields in Molecular Dynamics Simulations

| Force Field | Common Applications | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| OPLS/AA | Proteins, small molecules | Optimized for liquids, accurate for organic compounds |

| AMBER | Proteins, nucleic acids | Accurate for biomolecular simulations |

| CHARMM | Proteins, lipids, carbohydrates | Comprehensive biomolecular coverage |

| GROMOS | Proteins, carbohydrates | Unified atom approach, computational efficiency |

Simulation Box Definition and Solvation

The initial structure must be placed in a defined simulation box (unit cell), with choices of box shape including cubic, rectangular, or rhombic dodecahedron [32]. A rhombic dodecahedron is often the most efficient option as it contains the protein using the smallest volume, reducing computational resources devoted to solvent [32]. The system is then solvated with water molecules filling the unit cell, with common water models including SPC, SPC/E, TIP3P, and TIP4P [32]. Finally, ions (typically sodium or chloride) are added to neutralize the system's net charge and to achieve physiological ion concentrations if desired [32].

System Equilibration

Before production simulation, the system must be equilibrated to remove unfavorable atomic contacts and establish stable temperature and pressure conditions. The equilibration phase consists of multiple steps:

Energy Minimization

Energy minimization relaxes the structure by removing steric clashes or unusual geometry that would artificially raise the system's energy [32]. This step typically employs algorithms such as steepest descent or conjugate gradient to find a local energy minimum [32]. During minimization, the potential energy of the system should converge to a stable value, indicating that the structure has reached a stable configuration before dynamics begin.

NVT Equilibration (Constant Number, Volume, and Temperature)

The first stage of dynamics equilibration is performed under an NVT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature), also known as the isothermal-isochoric ensemble [32]. During this phase, the protein is typically held in place using position restraints while the solvent is allowed to move freely around it [32]. This allows the solvent to equilibrate around the protein structure without the protein itself undergoing large conformational changes. The temperature is maintained at the target value (e.g., 310 K for physiological conditions) using thermostats such as Berendsen or Nosé-Hoover.

NPT Equilibration (Constant Number, Pressure, and Temperature)

The second equilibration stage uses an NPT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature), also known as the isothermal-isobaric ensemble [32]. During NPT equilibration, the system density is allowed to adjust to achieve the target pressure (typically 1 bar for physiological conditions) using barostats such as Parrinello-Rahman or Berendsen [32]. Position restraints on the protein are often maintained but may be gradually released during this phase.

Production Simulation

After equilibration, the production simulation phase begins, during which the atomic trajectories are saved for subsequent analysis. In this phase, all restraints are removed, and the system evolves according to the natural dynamics governed by the force field [32]. The production simulation typically employs an integration time step of 1-2 femtoseconds, which is necessary to accurately capture the fastest atomic motions, such as bond vibrations involving hydrogen atoms [31]. The simulation is run for as long as computationally feasible to sample the biologically relevant conformational space, with modern simulations often reaching microsecond to millisecond timescales for smaller systems [8].

Trajectory Analysis Methods

The analysis of MD trajectories transforms raw atomic coordinates into meaningful biological insights. The specific analysis methods depend on the research questions, but several approaches are widely used:

Structural Analysis Methods

Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD)

RMSD measures the deviation of atom positions compared to a reference structure (often the initial frame), providing insight into the overall conformational stability of the system [33]. It is calculated as:

[RMSD(v,w) = \sqrt{ \frac{1}{n} \sum{i=1}^n \|vi - w_i\|² }]

where (v) and (w) represent the two sets of atomic coordinates being compared, and (n) is the number of atoms [33]. RMSD is particularly useful for assessing when a system has reached equilibrium and for identifying major conformational transitions.

Root-Mean-Square Fluctuation (RMSF)

RMSF measures the fluctuation of individual residues from their average positions throughout the simulation [33]. This analysis helps identify flexible and rigid regions of a protein, often correlating with functional domains or binding sites.

Radial Distribution Function (RDF)

The RDF describes how atoms are spatially distributed around a reference atom as a function of radial distance [31]. It is particularly useful for analyzing both ordered systems (crystalline solids) and disordered systems (liquids, amorphous materials), quantifying characteristic interatomic distances and coordination numbers [31].

Interaction Analysis

Hydrogen Bond Analysis