Molecular Dynamics Simulation: A Comprehensive Guide from Fundamentals to Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation, detailing its foundational principles in statistical mechanics, step-by-step methodological workflow, and practical optimization strategies.

Molecular Dynamics Simulation: A Comprehensive Guide from Fundamentals to Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation, detailing its foundational principles in statistical mechanics, step-by-step methodological workflow, and practical optimization strategies. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores key applications in drug discovery and biomolecular analysis, compares MD with other computational techniques, and outlines rigorous validation protocols. By synthesizing theory with practical application, this guide serves as an essential resource for leveraging MD to study structural dynamics, free energy landscapes, and interaction mechanisms at the atomic scale.

The Statistical Mechanics Engine: Core Principles Powering MD

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation is a powerful computational technique that predicts the time-dependent behavior of a molecular system, serving as a critical bridge between quantum mechanical theory and observable macroscopic properties. The core idea behind any molecular simulation method is straightforward: a particle-based description of the system under investigation is constructed and then propagated by either deterministic or probabilistic rules to generate a trajectory describing its evolution over time [1]. These simulations capture the behavior of proteins and other biomolecules in full atomic detail and at very fine temporal resolution, providing a dynamic window into atomic-scale processes that are often difficult to observe experimentally [2]. The impact of MD simulations in molecular biology and drug discovery has expanded dramatically in recent years, enabling researchers to decipher functional mechanisms of proteins, uncover structural bases for disease, and design therapeutic molecules [2]. This document outlines the theoretical foundations connecting quantum mechanics to classical particle models that make such simulations possible.

Theoretical Foundations: Connecting Quantum and Classical Descriptions

The Multi-Scale Modeling Paradigm

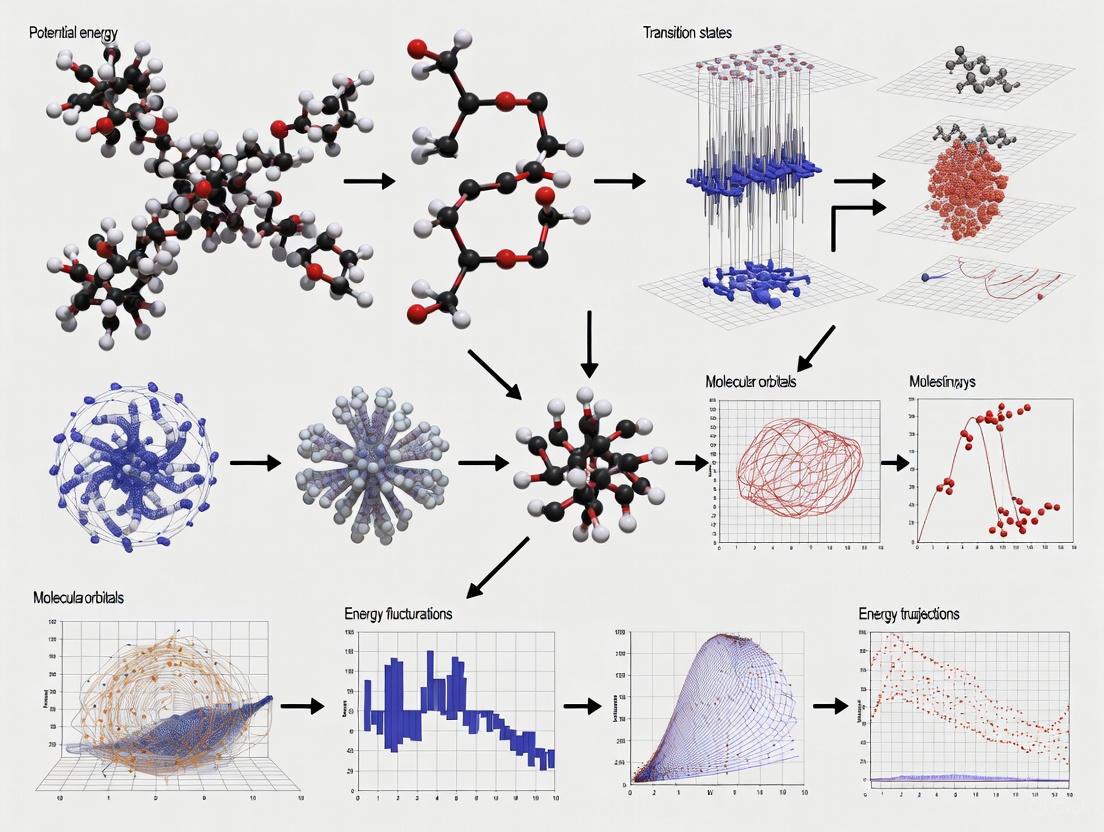

Molecular dynamics operates within a multi-scale modeling framework, selecting the appropriate physical description based on the system size and phenomena of interest. Figure 1 illustrates this modeling continuum and the position of classical MD within it.

Figure 1. The multi-scale modeling paradigm in molecular simulations.

At the most fundamental level, quantum mechanical (QM) descriptions explicitly represent electrons and calculate interaction energy by solving the electronic structure of molecules [1]. While highly accurate, QM simulations are computationally demanding, typically limiting system sizes to hundreds of atoms [1] [3]. For larger systems, including most biomolecules in their physiological environments, classical molecular mechanics (MM) provides a practical alternative. In MM descriptions, molecules are represented by particles representing atoms or groups of atoms, with each atom assigned an electric charge and a potential energy function parameterized against experimental or QM data [1]. Classical MD simulations routinely handle systems with tens to hundreds of thousands of atoms [1], making them the method of choice for studying biomolecular systems in the condensed phase.

From Quantum to Classical Mechanics

The transition from quantum to classical descriptions represents a fundamental approximation that enables practical simulation of biological systems. Classical molecular models typically consist of point particles carrying mass and electric charge with bonded interactions and non-bonded interactions [1]. The mathematical formulations of classical mechanics provide the framework for MD simulations, with the Hamiltonian formulation being particularly important for many simulation methods [1].

The key approximation in classical MD is the use of pre-parameterized potential energy functions (force fields) rather than computing electronic structure on-the-fly. This approximation sacrifices the ability to simulate bond breaking and forming (except with specialized reactive force fields) but gains several orders of magnitude in computational efficiency [1] [2]. The force field incorporates terms that capture electrostatic interactions between atoms, spring-like terms that model the preferred length of each covalent bond, and terms capturing several other types of interatomic interactions [2].

Table 1: Comparison of Simulation Approaches Across Scales

| Characteristic | Quantum Mechanics | Classical MD | Coarse-Grained |

|---|---|---|---|

| System Representation | Electrons and nuclei explicitly represented | Atoms as point particles with charges | Groups of atoms as single beads |

| Energy Calculation | Electronic structure theory | Pre-parameterized force fields | Simplified interaction potentials |

| Maximum System Size | Hundreds of atoms | Millions of atoms | Beyond atomistic scales |

| Timescales Accessible | Picoseconds to nanoseconds | Nanoseconds to milliseconds | Microseconds to seconds |

| Chemical Reactions | Yes | Generally no (except reactive FF) | No |

| Computational Cost | Very high | Moderate to high | Low to moderate |

Mathematical Foundations of Classical Molecular Dynamics

Newton's Equations of Motion

Classical Molecular Dynamics is a computational method that uses the principles of classical mechanics to simulate the motion of particles in a molecular system [3]. The foundation of MD simulations is Newton's second law of motion, which relates the force acting on a particle to its mass and acceleration:

Fᵢ = mᵢaᵢ = mᵢ(d²rᵢ/dt²) [3] [4]

where:

- Fᵢ is the force acting on particle i

- mᵢ is the particle's mass

- aᵢ is the particle's acceleration

- rᵢ is the particle's position

The force is also equal to the negative gradient of the potential energy function:

Fᵢ = -∇Vᵢ

where V represents the potential energy of the system [3]. By numerically integrating these equations of motion, MD simulations update the velocities and positions of particles iteratively to generate their trajectories over time [3].

Force Fields: The Bridge from Quantum to Classical

Force fields are mathematical models that describe the potential energy of a system as a function of the nuclear coordinates [3]. They serve as the crucial bridge connecting quantum mechanical accuracy to classical simulation efficiency. The total energy in a typical force field is a sum of bonded and non-bonded interactions [3]:

Vtotal = Vbonded + V_non-bonded

The bonded interactions include:

- Bond stretching (harmonic potential): Vbond = ½kb(r - r₀)²

- Angle bending (harmonic angle potential): Vangle = ½kθ(θ - θ₀)²

- Torsional rotations: Vdihedral = kφ[1 + cos(nφ - δ)]

The non-bonded interactions include:

- Van der Waals interactions (Lennard-Jones potential): V_LJ = 4ε[(σ/r)¹² - (σ/r)⁶]

- Electrostatic interactions (Coulomb potential): VCoulomb = (qiqj)/(4πε0r)

Table 2: Major Force Fields and Their Applications in Biomolecular Simulations

| Force Field | Developer/Institution | Key Applications | Special Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHARMM | Harvard University | Proteins, lipids, nucleic acids | Accurate for biological macromolecules [3] |

| AMBER | University of California | Proteins, DNA, RNA | Specialized for biomolecules and drug design [3] |

| OPLS-AA | Yale University | Organic molecules, proteins | Optimized for liquid-state properties [4] |

| GROMOS | University of Groningen | Biomolecules, polymers | Unified atom approach [3] |

| COMPASS | Accelrys | Polymers, inorganic materials | Parameterized for condensed phases [4] |

Practical Implementation of MD Simulations

The MD Simulation Workflow

Implementing a molecular dynamics simulation involves a series of methodical steps that transform an initial molecular structure into a dynamic trajectory. Figure 2 illustrates this comprehensive workflow.

Figure 2. The complete molecular dynamics simulation workflow.

The process begins with initial system setup, which includes defining the simulation box, adding solvent molecules, and introducing counterions to neutralize the system charge [4]. The simulation box serves as the boundary that separates the built system from its surroundings, and it can take different shapes such as a cube, rectangular cube, or cylinder depending on the system and software capabilities [4].

Ensembles and Temperature/Pressure Control

During simulation, the temperature and pressure of the system need to be controlled by specific algorithms to mimic experimental conditions [3]. An ensemble illustrates specific circumstances utilized in simulation systems, essentially isolating the simulation system from altering particle numbers or thermodynamic variables [4]. The most commonly used ensembles in MD simulations include:

- NVE Ensemble: Maintains a constant Number of particles, Volume, and Energy, representing a microcanonical ensemble with no heat transfer with external surroundings [4].

- NVT Ensemble: Maintains a constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature, representing a canonical ensemble where temperature is maintained using thermostats [3] [4].

- NPT Ensemble: Maintains a constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature, representing an isothermal-isobaric ensemble where both temperature and pressure are controlled [5] [4].

Temperature control methods include the Berendsen thermostat, Nose-Hoover thermostat, Anderson thermostat, and velocity scaling [3] [4]. Pressure control methods, such as the Berendsen barostat and Parrinello-Rahman method, maintain pressure by changing the volume of the system [3] [4].

Advanced Sampling and Equilibration Protocols

Achieving proper equilibration is a critical step in MD simulations, and various methods have been developed to enhance computational efficiency. Recent research has demonstrated that novel equilibration approaches can be significantly more efficient than conventional methods. For instance, a recently proposed ultrafast approach to achieve equilibration was reported to be ~200% more efficient than conventional annealing and ~600% more efficient than the lean method for studying ion exchange polymers [5].

The conventional annealing method involves sequential implementation of processes corresponding to NVT and NPT ensembles within an elevated temperature range (e.g., 300 K to 1000 K) [5]. This process is repeated iteratively until the desired density is achieved [5]. In contrast, the "lean method" encompasses only two steps of NVT and NPT ensembles, with the NPT ensemble running for an extended duration [5]. The development of more efficient equilibration protocols remains an active area of research, particularly for complex systems such as polymers and membrane proteins.

The practical application of molecular dynamics relies on sophisticated software packages that implement the theoretical foundations discussed previously. These tools have evolved significantly over decades, with modern packages leveraging both CPU and GPU computing resources to achieve unprecedented performance.

Table 3: Key Software Packages for Classical Molecular Dynamics Simulations

| Software | License | Key Features | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | Open Source | High performance, excellent parallelization | Biomolecules, polymers [3] |

| AMBER | Commercial | Specialized force fields, advanced sampling | Proteins, nucleic acids, drug design [3] |

| CHARMM | Commercial | Comprehensive force fields, flexibility | Biological macromolecules [3] |

| LAMMPS | Open Source | Extremely versatile, many force fields | Materials science, nanosystems [3] |

| NAMD | Open Source | Strong scalability, visualization tools | Large biomolecular systems [2] |

| OpenMM | Open Source | GPU acceleration, Python API | Custom simulation methods [6] |

Recent developments have focused on making MD simulations more accessible to non-specialists. Tools like drMD provide automated pipelines for running MD simulations using the OpenMM molecular mechanics toolkit, reducing the expertise required to run publication-quality simulations [6]. Such platforms feature user-friendly automation, comprehensive quality-of-life features, and advanced simulation options including enhanced sampling through metadynamics [6].

Applications in Drug Discovery and Biomolecular Research

Molecular dynamics simulations have become indispensable tools in modern drug discovery and biomolecular research. In structure-based drug design, MD addresses the challenge of receptor flexibility that conventional molecular docking methods often cannot capture [3]. While early docking methods assumed a simple "lock and key" scheme where both ligand and receptor were treated as rigid entities, MD simulations explicitly model the mutual adaptation of both molecules in complex states [3].

MD simulations provide critical insights into various biomolecular processes:

- Protein-ligand binding: Simulating the dynamic process of ligand recognition and binding to protein targets [2] [3]

- Membrane permeability: Studying lipid-drug interactions and transport across biological membranes [3]

- Ion channel mechanisms: Revealing gating mechanisms and ion selectivity in neuronal signaling proteins [2]

- Protein folding: Exploring energy landscapes and identifying physiological conformations [3]

- Allosteric regulation: Understanding long-range communication within biomolecules [2]

A key application of MD in pharmaceutical research is the study of specific drug targets such as G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), ion channels, and neurotransmitter transporters [2]. For example, simulations have been used to study proteins critical to neuronal signaling, assist in developing drugs targeting the nervous system, reveal mechanisms of protein aggregation associated with neurodegenerative disorders, and provide foundations for improved optogenetics tools [2].

Successful implementation of molecular dynamics simulations requires both computational tools and theoretical knowledge. The following toolkit summarizes essential resources for researchers entering the field.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources for MD Simulations

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Simulation Software | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD, LAMMPS, OpenMM | Core simulation engines implementing integration algorithms and force calculations [3] |

| Force Fields | CHARMM36, AMBER/ff14SB, OPLS-AA, GROMOS | Parameter sets defining potential energy functions for different molecule types [3] [4] |

| Visualization Tools | VMD, PyMol, Chimera | Trajectory analysis, structure visualization, and figure generation [2] |

| System Preparation | CHARMM-GUI, PACKMOL, tleap | Building simulation systems with proper solvation and ionization [4] |

| Analysis Packages | MDTraj, MDAnalysis, GROMACS tools | Calculating properties from trajectories (RMSD, RMSF, distances, etc.) [2] |

| Enhanced Sampling | PLUMED, MetaDynamics, Umbrella Sampling | Accelerating rare events and improving conformational sampling [6] |

| Reference Texts | "Computer Simulation of Liquids" (Allen & Tildesley), "Understanding Molecular Simulation" (Frenkel & Smit) | Foundational knowledge of theory and methods [1] |

Molecular Dynamics simulations provide a powerful theoretical and computational framework that connects quantum mechanical principles with classical particle models to study complex molecular systems. The foundation of MD rests on solving Newton's equations of motion numerically while using force fields parameterized from quantum mechanical calculations and experimental data to describe interatomic interactions. This approach enables the simulation of systems at biologically relevant scales—thousands to millions of atoms—while maintaining computational tractability. As MD simulations continue to evolve with improvements in force field accuracy, enhanced sampling algorithms, and computational hardware, they offer increasingly valuable insights into molecular mechanisms underlying biological function and drug action. For researchers in drug development and molecular sciences, understanding these theoretical foundations is essential for properly applying MD simulations to address challenging research questions.

In the realm of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, force fields serve as the fundamental computational model that defines the potential energy of a system of atoms based on their positions and interactions. [7] Understanding complex biological phenomena requires simulations of large systems over long time windows, and the forces acting between atoms and molecules are too complex to calculate from first principles each time. Therefore, interactions are approximated with a simple empirical potential energy function. [8] This potential energy function allows researchers to calculate forces ( ( \vec{F} = -\nabla{U}(\vec{r}) ) ), and with knowledge of these forces, they can determine how atomic positions evolve over time through numerical integration. [8] The selection of an appropriate force field is essential, as it greatly influences the reliability of MD simulation outcomes in applications ranging from basic protein studies to sophisticated drug development projects. [9]

Fundamental Components of Force Fields

A force field refers to the functional form and parameter sets used to calculate the potential energy of a system of atoms. [7] The basic functional form for potential energy in molecular modeling can be decomposed into bonded and non-bonded interaction terms, following the general expression: ( E{\text{total}} = E{\text{bonded}} + E_{\text{nonbonded}} ). [7] [8] This additive approach allows for computationally efficient evaluation of complex molecular systems.

Table 1: Core Components of a Classical Force Field

| Energy Component | Mathematical Formulation | Physical Description | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Stretching [7] [8] | ( E{\text{bond}} = \frac{k{ij}}{2}(l{ij} - l{0,ij})^2 ) | Energy cost to stretch or compress a covalent bond from its equilibrium length. | Bond force constant (( k{ij} )), equilibrium bond length (( l{0,ij} )) |

| Angle Bending [8] | ( E{\text{angle}} = k\theta(\theta{ijk} - \theta0)^2 ) | Energy cost to bend the angle between three bonded atoms from its equilibrium value. | Angle force constant (( k\theta )), equilibrium angle (( \theta0 )) |

| Torsional Dihedral [7] [8] | ( E{\text{dihed}} = k\phi(1 + \cos(n\phi - \delta)) ) | Energy barrier for rotation around a central bond, defined for four sequentially bonded atoms. | Barrier height (( k_\phi )), periodicity (( n )), phase shift (( \delta )) |

| van der Waals (Non-bonded) [7] [8] | ( V_{LJ}(r) = 4\epsilon \left[ \left(\frac{\sigma}{r}\right)^{12} - \left(\frac{\sigma}{r}\right)^{6} \right] ) | Pairwise potential describing short-range Pauli repulsion (( r^{-12} )) and London dispersion attraction (( r^{-6} )). | Well depth (( \epsilon )), van der Waals radius (( \sigma )) |

| Electrostatic (Non-bonded) [7] [8] | ( E{\text{Coulomb}} = \frac{1}{4\pi\varepsilon0} \frac{qi qj}{r_{ij}} ) | Long-range interaction between permanently charged or partially charged atoms. | Atomic partial charges (( qi, qj )), dielectric constant (( \varepsilon )) |

Bonded Interactions

Bonded interactions describe the energy associated with the covalent bond structure of a molecule and are typically modeled using harmonic (quadratic) approximations for bonds and angles. [8] The bond potential describes the energy of vibrating covalent bonds, approximated well by a harmonic oscillator near the equilibrium bond length. [8] Similarly, the angle potential describes the energy of bending between three covalently bonded atoms. The force constants for angle bending are typically about five times smaller than those for bond stretching, making angles easier to deform. [8]

Torsional dihedral potentials describe the energy barrier for rotation around a central bond, defined for every set of four sequentially bonded atoms. [8] This term is crucial for capturing conformational preferences, such as the energy differences between trans and gauche states. The functional form is periodic, often written as a sum of cosine terms. [8] Improper dihedrals are used primarily to enforce planarity in certain molecular arrangements, such as aromatic rings or sp2-hybridized centers, and are typically modeled with a harmonic potential. [8]

Non-Bonded Interactions

Non-bonded interactions occur between all atoms in the system, regardless of connectivity, and are computationally the most intensive part of force field evaluation. [7] [8] These include van der Waals forces and electrostatic interactions.

The Lennard-Jones (LJ) potential is the most common function for describing van der Waals interactions, which comprise both short-range Pauli repulsion and weaker attractive dispersion forces. [8] The repulsive ( r^{-12} ) term approximates the strong repulsion from overlapping electron orbitals, while the attractive ( r^{-6} ) term describes the induced dipole-dipole interactions. [7] [8] The LJ potential is characterized by two parameters: ( \sigma ), the finite distance where the potential is zero, and ( \epsilon ), the well depth. [8]

Electrostatic interactions between atomic partial charges are described by Coulomb's law. [7] [8] These are long-range interactions that decrease with ( r^{-1} ), requiring special treatment in periodic simulations. The assignment of atomic partial charges is a critical aspect of force field parameterization, often derived from quantum mechanical calculations with heuristic adjustments. [7]

To manage the vast number of possible pairwise interactions between different atom types, force fields use combining rules. Common approaches include the Lorentz-Berthelot rule (( \sigma{ij} = \frac{\sigma{ii} + \sigma{jj}}{2} ), ( \epsilon{ij} = \sqrt{\epsilon{ii} \times \epsilon{jj}} )) used by CHARMM and AMBER, and the geometric mean rule (( \sigma{ij} = \sqrt{\sigma{ii} \times \sigma{jj}} ), ( \epsilon{ij} = \sqrt{\epsilon{ii} \times \epsilon{jj}} )) used by GROMOS and OPLS. [8]

Diagram 1: Force field energy components hierarchy.

Force Field Types and Parameterization

Force Field Classification

Force fields are empirically derived and can be classified based on their complexity and treatment of electronic effects:

- Class 1 force fields describe bond stretching and angle bending with simple harmonic potentials and omit correlations between these internal coordinates. Examples include AMBER, CHARMM, GROMOS, and OPLS, which are widely used for biomolecular simulations. [8]

- Class 2 force fields introduce greater complexity by adding anharmonic cubic and/or quartic terms to bonds and angles, and include cross-terms describing coupling between adjacent internal coordinates. Examples include MMFF94 and UFF. [8]

- Class 3 force fields explicitly incorporate electronic polarization effects and other quantum mechanical phenomena such as stereoelectronic effects. Examples include AMOEBA, DRUDE, and other polarizable force fields. [8]

Another important distinction is between all-atom force fields, which provide parameters for every atom including hydrogen, and united-atom potentials, which treat hydrogen atoms bound to carbon as part of the interaction center. [7] Coarse-grained potentials represent even larger groups of atoms as single interaction sites, sacrificing chemical details for computational efficiency in long-time simulations of macromolecules. [7]

Table 2: Classification of Force Fields by Complexity and Application

| Force Field Class | Key Features | Representative Examples | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Class 1 (Biomolecular) [8] | Harmonic bonds/angles; No cross-terms; Non-polarizable. | AMBER, CHARMM, GROMOS, OPLS | Proteins, Nucleic Acids, Lipids |

| Class 2 (Anharmonic) [8] | Cubic/quartic bond/angle terms; Cross-terms between internal coordinates. | MMFF94, UFF | Small Organic Molecules, Drug-like Compounds |

| Class 3 (Polarizable) [8] | Explicit electronic polarization; More quantum effects. | AMOEBA, DRUDE | Systems where charge distribution changes significantly |

| Reactive [7] | Bond breaking/formation; Bond order consideration. | ReaxFF | Chemical reactions, Combustion |

| Coarse-Grained [7] | Multiple atoms per site; Reduced complexity; Faster sampling. | MARTINI | Large Assemblies, Long Timescales |

Parameterization Strategies

Force field parameters are derived through a meticulous process that balances computational efficiency with physical accuracy. Parameterization utilizes data from both classical laboratory experiments and quantum mechanical calculations. [7] The parameters for a chosen energy function may be derived from classical laboratory experiment data, calculations in quantum mechanics, or both. [7]

Heuristic parametrization procedures have been very successful for many years, though they have recently been criticized for subjectivity and reproducibility concerns. [7] More systematic approaches are emerging that use extensive databases of experimental and quantum mechanical data with automated fitting procedures.

Atomic charges, which make dominant contributions to potential energy especially for polar molecules and ionic compounds, are typically assigned using quantum mechanical protocols with heuristic adjustments. [7] These charges are critical for simulating geometry, interaction energy, and reactivity. [7] The Lennard-Jones parameters and bonded terms are often optimized to reproduce experimental properties such as liquid densities, enthalpies of vaporization, and various spectroscopic properties. [7]

Practical Implementation in Molecular Dynamics

Force Fields in MD Software Packages

Widely adopted MD software packages such as GROMACS, DESMOND, and AMBER leverage rigorously tested force fields and have shown consistent performance across diverse biological applications. [9] These packages implement the mathematical formulations of force fields to calculate forces on each atom, which are then used to integrate the equations of motion.

In GROMACS, for example, the combining rule for non-bonded interactions is specified in the forcefield.itp file, allowing compatibility with different force field requirements: GROMOS requires rule 1, OPLS requires rule 3, while CHARMM and AMBER require rule 2 (Lorentz-Berthelot). [8] The type of potential function (Lennard-Jones vs. Buckingham) is also specified in this file. [8]

Workflow for MD Simulations

A typical MD simulation follows a structured workflow that ensures proper system setup and reliable results. The general process begins with system preparation, followed by energy minimization, equilibration, and finally production simulation. [10] [8]

Diagram 2: Molecular dynamics simulation workflow.

A specific example protocol for protein-ligand MD simulations includes:

- System Preparation: Generate topology files for protein and ligand using tools like AMBER's

antechamber. Add missing hydrogen atoms using programs likeLeap. [10] - Solvation: Place the complex in a periodic boundary solvation box with explicit water molecules (e.g., TIP3P model) extending 10 Å from the complex. [10]

- Neutralization: Add counter ions (e.g., Na+ and Cl−) to neutralize the system charge. [10]

- Minimization: Perform energy minimization (e.g., for 20 fs) to remove steric clashes and unfavorable contacts. [10]

- Equilibration: Gradually heat the system to the target temperature (e.g., 310 K) through multiple equilibration stages (e.g., 200 K, 250 K, 300 K) to stabilize the system. [10]

- Production Simulation: Run the production MD simulation (e.g., 50 ns), saving trajectories at regular intervals (e.g., every 2 ps) for subsequent analysis. [10]

Advanced Applications and Recent Developments

Force fields and MD simulations continue to evolve, enabling increasingly sophisticated applications in materials science and drug discovery. Recent studies demonstrate the expanding capabilities of these methods:

- Drug Solubility Prediction: Machine learning analysis of MD-derived properties has identified key descriptors for predicting aqueous solubility of drugs, including Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA), Coulombic and Lennard-Jones interaction energies, and solvation shell properties. [11] These MD properties demonstrate predictive power comparable to traditional structural descriptors. [11]

- Thermal Stability of Energetic Materials: Neural network potentials are being integrated with MD simulations to create optimized protocols for predicting thermal stability of energetic materials, achieving strong correlation (R² = 0.969) with experimental results. [12] Key improvements include nanoparticle models and reduced heating rates to minimize overestimation of decomposition temperatures. [12]

- Complete Virion Simulation: Recent advances have enabled simulations of enormous systems, such as the entire SARS-CoV-2 virion (304,780,149 atoms), revealing how spike glycans modulate viral infectivity and characterizing interactions with human receptors. [8]

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Dynamics

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Simulation Software [11] [10] [9] | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD, DESMOND | Core MD engines for numerical integration of equations of motion |

| Force Field Databases [7] | MolMod, OpenKIM, TraPPE | Repositories of validated force field parameters |

| System Preparation [10] | AMBER antechamber, VMD, LeaP | Generate topology files, add hydrogens, assign parameters |

| Analysis Tools [11] [10] | CPPTRAJ, Bio3D, GROMACS utilities | Process trajectories, calculate properties and observables |

| Specialized Analysis [10] | MM/GBSA (AMBER) | Calculate binding free energies from MD trajectories |

| Visualization [10] | VMD, PyMOL | Visual inspection of structures and trajectories |

Force fields and their underlying potential energy functions provide the essential theoretical framework that enables molecular dynamics simulations to bridge the gap between atomic-level interactions and macroscopic observables. The continued refinement of force field accuracy through better parameterization strategies, including the incorporation of machine learning and neural network potentials, promises to further enhance the predictive power of MD simulations. [12] As these computational methods become increasingly integrated with experimental structural biology and medicinal chemistry, they offer unprecedented insights into molecular behavior and accelerate the discovery and development of new therapeutic agents. [11] [9]

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation has emerged as an indispensable tool in biomedical research and drug development, providing atomic-resolution insights into biomolecular processes such as structural flexibility and molecular interactions [9]. The predictive power of MD stems from its foundation in statistical mechanics, which connects the deterministic motion of individual atoms described by Newtonian physics to the thermodynamic properties observable in experiments [13]. Understanding this connection is crucial for researchers interpreting simulation data for applications like inhibitor development and protein engineering [9]. This technical guide explores how different statistical ensembles—the microcanonical (NVE), canonical (NVT), and isothermal-isobaric (NPT)—form the theoretical framework that bridges microscopic behavior captured by MD simulations with macroscopic thermodynamic properties relevant to biological systems and drug design.

Fundamental Concepts: Microstates, Macrostates, and Ensembles

Microstates Versus Macrostates

In statistical mechanics, a microstate is a specific, detailed configuration of a system that describes the precise positions and momenta of all individual particles or components [14]. For a protein in solution, each unique arrangement of all atomic coordinates and velocities constitutes a distinct microstate. In contrast, the macrostate of a system refers to its macroscopic properties, such as temperature, pressure, volume, and density [14]. A single macrostate corresponds to an enormous number of possible microstates that share the same macroscopic properties.

The fundamental relationship connecting microstates and macrostates is expressed through the Boltzmann entropy formula: [ S = kB \ln \Omega ] where (S) is entropy, (kB) is Boltzmann's constant, and (\Omega) is the number of microstates accessible to the system [14]. For systems where microstates have unequal probabilities, a more general definition applies: [ S = -kB \sum{i=1}^{\Omega} pi \ln(pi) ] where (p_i) is the probability of microstate (i$ [14].

The Ensemble Concept in Statistical Mechanics

An ensemble is a theoretical collection of all possible microstates of a system subject to certain macroscopic constraints [13]. While a single MD simulation generates one trajectory through microstates, statistical mechanics considers the ensemble average over all possible microstates to predict macroscopic observables. The internal energy (U$ of a macrostate, for instance, represents the mean over all microstates of the system's energy: [ U = \langle E \rangle = \sum{i=1}^{\Omega} pi Ei ] where (Ei$ is the energy of microstate $i$ [14].

Table 1: Fundamental Statistical Mechanics Relationships Connecting Microstates to Macroscopic Properties

| Macroscopic Property | Mathematical Definition | Physical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Internal Energy (U) | ( U = \sum{i=1}^{\Omega} pi E_i ) | Mean energy of the system; relates to first law of thermodynamics [14] |

| Entropy (S) | ( S = -kB \sum{i=1}^{\Omega} pi \ln(pi) ) | Measure of uncertainty/disorder; maximum for equal (p_i$ [14] |

| Heat (δQ) | ( \delta Q = \sum{i=1}^{N} Ei dp_i ) | Energy transfer associated with changes in occupation numbers [14] |

| Work (δW) | ( \delta W = \sum{i=1}^{N} pi dE_i ) | Energy transfer associated with changes in energy levels [14] |

Statistical Ensembles in Molecular Dynamics

The Microcanonical Ensemble (NVE)

The microcanonical ensemble describes isolated systems with constant number of particles (N), constant volume (V), and constant energy (E) [13]. In this ensemble, all microstates with energy E are equally probable, with probability: [ p_i = 1/\Omega ] where (\Omega$ is the number of microstates accessible to the system [13].

In MD simulations, NVE conditions are implemented by numerically integrating Newton's equations of motion without adding or removing energy from the system. This approach conserves total energy exactly (within numerical precision) and generates dynamics that sample the microcanonical ensemble. The temperature in NVE simulations fluctuates as the system exchanges energy between kinetic and potential forms.

The Canonical Ensemble (NVT)

The canonical ensemble describes systems with constant particle number (N), constant volume (V), and constant temperature (T) [13]. This corresponds to a system in thermal equilibrium with a much larger heat bath, allowing energy exchange but not particle exchange. The probability of each microstate in the canonical ensemble follows the Boltzmann distribution: [ pi = \frac{e^{-\beta Ei}}{Z} ] where (\beta = 1/kB T$ and $Z$ is the canonical partition function: [ Z = \sumi e^{-\beta Ei} ] The partition function connects to the Helmholtz free energy through ( A = -kB T \ln Z ).

In MD, NVT conditions are typically implemented using thermostats such as Nosé-Hoover, Berendsen, or Langevin thermostats, which adjust particle velocities to maintain the desired temperature.

The Isothermal-Isobaric Ensemble (NPT)

The isothermal-isobaric ensemble describes systems with constant particle number (N), constant pressure (P), and constant temperature (T), matching typical laboratory conditions. This ensemble is essential for simulating biomolecular systems where volume changes must be permitted. The probability distribution includes a volume dependence: [ pi = \frac{e^{-\beta (Ei + PV)}}{\Delta} ] where (\Delta$ is the isothermal-isobaric partition function.

In MD simulations, NPT conditions are implemented using barostats (such as Parrinello-Rahman or Berendsen barostats) in combination with thermostats, allowing the simulation box size and shape to fluctuate to maintain constant pressure.

Table 2: Comparison of Statistical Ensembles in Molecular Dynamics Simulations

| Ensemble Type | Constant Parameters | Probability Distribution | Common MD Algorithms | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microcanonical (NVE) | N, V, E | ( p_i = 1/\Omega ) | Verlet, Leapfrog | Studying natural dynamics, fundamental properties [13] |

| Canonical (NVT) | N, V, T | ( pi = \frac{e^{-\beta Ei}}{Z} ) | Nosé-Hoover, Berendsen, Langevin thermostats | Most biomolecular simulations [13] |

| Isothermal-Isobaric (NPT) | N, P, T | ( pi = \frac{e^{-\beta (Ei + PV)}}{\Delta} ) | Parrinello-Rahman, Berendsen barostats | Simulating physiological conditions |

Computational Methodologies and Protocols

Free Energy Calculation Methods

Understanding the thermodynamics of biomolecular recognition is crucial for drug development, and MD simulations enable several approaches for free energy calculations [13]:

Thermodynamic Pathway Methods use alchemical transformations to compute free energy differences between related systems. These include:

- Free Energy Perturbation (FEP): Calculates free energy differences between states by gradually transforming one system into another.

- Thermodynamic Integration (TI): Integrates the derivative of the Hamiltonian with respect to a coupling parameter.

- Bennett Acceptance Ratio (BAR): An optimized method for estimating free energy differences between two states.

Potential of Mean Force (PMF) calculations determine the free energy along a specific reaction coordinate, providing insights into binding pathways and energy barriers [13].

End-Point Methods such as MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA estimate binding free energies using only simulation snapshots from the bound and unbound states, offering a computationally efficient alternative [13].

Entropic Calculations from MD Trajectories

Entropy plays a crucial role in biomolecular recognition, and MD simulations enable its calculation through:

- Quasi-Harmonic Analysis: Approximates the potential energy surface as harmonic and calculates entropy from the covariance matrix of atomic fluctuations [13].

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Identifies essential dynamics and major modes of fluctuation, which can be used for entropy estimation [13].

These methods help decompose free energy changes into enthalpic and entropic contributions, providing deeper insights into the driving forces of molecular recognition [13].

Diagram 1: Relationship between microstates, ensembles, and MD implementation, showing how statistical averaging connects microscopic behavior to macroscopic observables.

Advanced Analysis Techniques for MD Simulations

Trajectory Analysis Methods

MD simulations generate trajectories representing a system's evolution over time, requiring sophisticated analysis methods to extract meaningful information [15]:

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Measures structural similarity between configurations, often used to assess simulation stability.

- Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF): Quantifies residue flexibility, identifying mobile regions of proteins.

- Radius of Gyration (Rgyr): Measures compactness of molecular structures.

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Identifies collective motions in biomolecules.

- Trajectory Maps: A novel visualization method representing protein backbone movements as heatmaps, showing location, time, and magnitude of conformational changes [15].

Binding Free Energy Calculations

For drug discovery applications, accurately predicting binding affinities is essential. MD-based approaches include:

- Alchemical Free Energy Calculations: Use non-physical pathways to transform one molecule into another, providing high accuracy for relative binding free energies.

- Umbrella Sampling: Enhances sampling along a predetermined reaction coordinate for PMF calculations.

- Metadynamics: Accelerates rare events by adding bias potential to explored regions of phase space.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Dynamics Simulations

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| MD Simulation Software | GROMACS, AMBER, DESMOND [9] | Primary engines for running MD simulations with optimized algorithms |

| Force Fields | CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS [9] | Mathematical representations of interatomic potentials governing molecular interactions |

| Analysis Tools | MDTraj, TRAVIS, VMD [15] | Software for processing MD trajectories and calculating physicochemical properties |

| Visualization Tools | PyMol, VMD, TrajMap.py [15] | Programs for visualizing molecular structures and dynamics |

| Thermostats | Nosé-Hoover, Berendsen, Langevin [13] | Algorithms maintaining constant temperature in NVT and NPT ensembles |

| Barostats | Parrinello-Rahman, Berendsen [13] | Algorithms maintaining constant pressure in NPT ensemble |

Case Studies and Research Applications

Protein-Ligand Binding Studies

MD simulations have provided fundamental insights into biomolecular recognition, particularly regarding the role of conformational entropy and solvent effects [13]. Studies of T4 lysozyme have served as a model system, revealing how mutations affect protein flexibility and ligand binding thermodynamics [13]. These investigations demonstrate how ensemble-based simulations can decompose binding free energies into enthalpic and entropic contributions, guiding rational drug design.

Protein-DNA Interactions

Advanced analysis techniques like trajectory maps have been applied to study transcription activator-like effector (TAL) complexes with DNA [15]. These methods enable direct comparison of simulation stability and identification of specific regions of instability and their timing, providing insights beyond traditional RMSD and RMSF analyses [15].

Diagram 2: MD simulation workflow showing the role of different statistical ensembles at various stages, from system setup to production simulation and analysis.

Emerging Trends in MD Simulations

The field of molecular dynamics continues to evolve with several promising directions:

- Integration with Machine Learning: ML approaches are accelerating force field development, analysis, and sampling [9] [16].

- Multiscale Simulation Methods: Combining quantum, classical, and coarse-grained models to address broader spatial and temporal scales [16].

- High-Performance Computing: Leveraging advances in computer architecture to simulate larger systems for longer timescales [13].

- Experimental Data Integration: Combining simulation results with experimental data from cryo-EM, NMR, and other techniques for validation and insight [16].

Statistical ensembles provide the essential theoretical framework connecting the microscopic configurations sampled in MD simulations to macroscopic thermodynamic properties relevant to drug discovery and biomolecular engineering. The NVE, NVT, and NPT ensembles each serve distinct purposes in modeling different experimental conditions, enabling researchers to probe the thermodynamic driving forces of molecular recognition. As MD methodologies continue to advance, particularly with integration of machine learning and enhanced sampling techniques, the role of statistical mechanics in guiding and interpreting simulations remains fundamental to extracting meaningful biological insights from atomic-level dynamics.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation has become an indispensable tool in modern computational science, providing a unique window into the atomic-scale processes that underlie physical, chemical, and biological phenomena. By numerically solving Newton's equations of motion for systems comprising thousands to millions of atoms, MD enables researchers to track the temporal evolution of molecular systems with femtosecond resolution, functioning as a "computational microscope" with exceptional spatiotemporal resolution [17]. The validity of this approach rests upon the powerful assumption that "all things are made of atoms, and that everything that living things do can be understood in terms of the jigglings and wigglings of atoms" [18]. In the context of drug discovery and pharmaceutical development, MD simulations provide critical insights into ligand-receptor interactions, membrane permeability, and formulation stability, significantly accelerating the research and development process [19].

The mathematical foundation of MD rests upon the numerical integration of classical equations of motion, requiring robust algorithms that can preserve the fundamental conservation laws of energy and momentum over simulation timescales that may extend to microseconds or beyond. Among the various integration schemes available, the Verlet algorithm and its variants have emerged as the dominant method for MD simulations due to their favorable numerical stability and conservation properties [20] [21]. This technical guide explores the mathematical foundations, implementation details, and practical applications of numerical integration and the Verlet algorithm within the broader context of molecular dynamics simulation research, with particular emphasis on applications relevant to drug development professionals.

Mathematical Foundations of Molecular Dynamics

Newton's Equations of Motion in Molecular Systems

At its core, molecular dynamics simulation is based on Newton's second law of motion, which for a molecular system can be expressed as:

[ mi \frac{d^2\mathbf{r}i}{dt^2} = \mathbf{F}i = -\nablai V({\mathbf{r}_j}) ]

where (mi) is the mass of atom i, (\mathbf{r}i) is its position, (\mathbf{F}i) is the force acting upon it, and (V({\mathbf{r}j})) is the potential energy function describing the interatomic interactions within the system [22]. The analytical solution of this system of coupled differential equations is intractable for systems containing more than a few atoms, necessitating numerical approaches for practical simulation [21].

The potential energy function (V({\mathbf{r}_j})) is typically described by a molecular mechanics force field that includes terms for bonded interactions (bonds, angles, dihedrals) and non-bonded interactions (van der Waals, electrostatics) [18]. Popular force fields include AMBER, CHARMM, and GROMOS, which differ primarily in their parameterization strategies but share similar functional forms [18]. The accurate representation of these energy terms is crucial for generating physically meaningful dynamics, and ongoing refinements to force fields continue to expand the applicability and reliability of MD simulations [19].

The Finite Difference Approach

Molecular dynamics simulations employ the finite difference method to integrate the equations of motion, where the total simulation time is divided into many small discrete time steps ((\Delta t)), typically on the order of 0.5-2 femtoseconds (10⁻¹⁵ seconds) [21]. This time step must be sufficiently small to accurately capture the fastest motions in the system, which are typically bond vibrations involving hydrogen atoms [17].

At each time step, the forces acting on each atom are computed from the current molecular configuration, and these forces are used to propagate the positions and velocities forward in time according to the integration algorithm. The process is repeated millions of times to generate a trajectory - a time-series of atomic positions that describes the evolution of the system [21]. The fundamental challenge in designing integration algorithms lies in balancing computational efficiency with numerical accuracy and stability, particularly for the long simulations required to observe biologically relevant processes.

The Verlet Integration Algorithm

Basic Formulation

The Verlet algorithm is one of the most widely used integration methods in molecular dynamics due to its numerical stability and conservation properties [20]. The algorithm can be derived from the Taylor series expansions for the position forward and backward in time:

[ \mathbf{r}(t + \Delta t) = \mathbf{r}(t) + \Delta t \mathbf{v}(t) + \frac{\Delta t^2}{2} \mathbf{a}(t) + \frac{\Delta t^3}{6} \mathbf{b}(t) + \mathcal{O}(\Delta t^4) ]

[ \mathbf{r}(t - \Delta t) = \mathbf{r}(t) - \Delta t \mathbf{v}(t) + \frac{\Delta t^2}{2} \mathbf{a}(t) - \frac{\Delta t^3}{6} \mathbf{b}(t) + \mathcal{O}(\Delta t^4) ]

Adding these two equations and solving for (\mathbf{r}(t + \Delta t)) yields the fundamental Verlet update formula:

[ \mathbf{r}(t + \Delta t) = 2\mathbf{r}(t) - \mathbf{r}(t - \Delta t) + \Delta t^2 \mathbf{a}(t) + \mathcal{O}(\Delta t^4) ]

Remarkably, the third-order terms cancel, resulting in a local truncation error of (\mathcal{O}(\Delta t^4)) despite using only second-derivative information [20] [23]. The velocity does not appear explicitly in the basic Verlet algorithm but can be estimated from the positions as:

[ \mathbf{v}(t) = \frac{\mathbf{r}(t + \Delta t) - \mathbf{r}(t - \Delta t)}{2\Delta t} + \mathcal{O}(\Delta t^2) ]

This estimation has a global error of (\mathcal{O}(\Delta t^2)), which is less accurate than the position calculation [21] [23].

Variants of the Verlet Algorithm

Velocity Verlet Algorithm

The Velocity Verlet algorithm addresses the limitation of the basic Verlet method by explicitly maintaining and updating velocities at the same time points as the positions. This variant is currently one of the most widely used integration algorithms in molecular dynamics simulations [21] [24]. The update equations are:

[ \mathbf{r}(t + \Delta t) = \mathbf{r}(t) + \Delta t \mathbf{v}(t) + \frac{\Delta t^2}{2} \mathbf{a}(t) ]

[ \mathbf{v}(t + \Delta t) = \mathbf{v}(t) + \frac{\Delta t}{2} [\mathbf{a}(t) + \mathbf{a}(t + \Delta t)] ]

Table 1: Comparison of Verlet Algorithm Variants

| Algorithm | Velocity Handling | Accuracy | Stability | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Verlet | Implicit, estimated from positions | (\mathcal{O}(\Delta t^4)) for positions, (\mathcal{O}(\Delta t^2)) for velocities | High | Systems where velocity is not critical |

| Velocity Verlet | Explicit, maintained at same time points as positions | (\mathcal{O}(\Delta t^2)) for both positions and velocities | Very High | Molecular dynamics, damping systems |

| Leapfrog Verlet | Explicit, maintained at half-time steps | (\mathcal{O}(\Delta t^2)) | Very High | Game physics, particle systems |

| Position Verlet | No explicit velocity storage | Medium | High | Springs, ropes, cloth simulations |

Leapfrog Algorithm

The Leapfrog algorithm is another popular variant that stores velocities at half-time steps while positions remain at integer time steps [21]. The update equations are:

[ \mathbf{v}\left(t + \frac{\Delta t}{2}\right) = \mathbf{v}\left(t - \frac{\Delta t}{2}\right) + \Delta t \mathbf{a}(t) ]

[ \mathbf{r}(t + \Delta t) = \mathbf{r}(t) + \Delta t \mathbf{v}\left(t + \frac{\Delta t}{2}\right) ]

This "leaping" of positions and velocities over each other gives the method its name and creates a highly stable integration scheme [24]. However, the half-step offset between positions and velocities complicates the calculation of system properties that depend on synchronous position and velocity information.

Implementation and Workflow

Molecular Dynamics Simulation Protocol

The standard workflow for molecular dynamics simulation follows a systematic protocol that ensures proper initialization and physically meaningful dynamics. The diagram below illustrates this workflow:

Diagram Title: Molecular Dynamics Simulation Workflow

Initial Structure Preparation

Every MD simulation begins with preparing the initial atomic coordinates of the system under study [17]. For biomolecular systems, structures are typically obtained from experimental databases such as the Protein Data Bank (PDB), while small molecules may be sourced from PubChem or ChEMBL [17]. In many cases, the initial structure requires preprocessing to add missing atoms, correct structural ambiguities, or incorporate novel molecular designs not present in existing databases.

System Initialization

Once the initial structure is prepared, the system must be initialized with appropriate initial velocities sampled from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution corresponding to the desired simulation temperature [17]. The system may also be solvated in explicit water molecules, ions may be added to achieve physiological concentration or charge neutrality, and the entire system is typically placed within a simulation box with periodic boundary conditions to minimize edge effects [19].

Force Calculation

The force calculation is typically the most computationally intensive step in MD simulations, as it involves evaluating all bonded and non-bonded interactions between atoms [21] [17]. The forces are derived from the potential energy function as:

[ \mathbf{F}i = -\nablai V({\mathbf{r}_j}) ]

where (V) includes terms for bond stretching, angle bending, torsional rotations, van der Waals interactions, and electrostatic forces [18]. Various optimization techniques, including cutoff methods, Ewald summation for electrostatics, and parallelization strategies are employed to make these calculations computationally tractable for large systems [17].

Time Integration

The time integration step applies the Verlet algorithm (or one of its variants) to propagate the positions and velocities forward by one time step using the computed forces [21]. This represents the core of the MD algorithm and is repeated millions of times to generate the simulation trajectory. The choice of time step represents a critical balance between numerical stability and computational efficiency, with typical values of 1-2 fs providing a reasonable compromise [17].

Trajectory Analysis

The final stage involves analyzing the simulation trajectory - the time-series of atomic coordinates and velocities - to extract physically meaningful insights [17]. Common analyses include calculating radial distribution functions to characterize local structure, mean square displacement to determine diffusion coefficients, principal component analysis to identify essential collective motions, and various energy calculations to determine thermodynamic properties [17].

Comparison of Integration Methods

Table 2: Numerical Integration Methods in Molecular Dynamics

| Method | Formulation | Advantages | Disadvantages | Error Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Euler | (\mathbf{r}(t+\Delta t) = \mathbf{r}(t) + \Delta t \mathbf{v}(t)) (\mathbf{v}(t+\Delta t) = \mathbf{v}(t) + \Delta t \mathbf{a}(t)) | Simple implementation | Energy drift, poor stability | (\mathcal{O}(\Delta t)) |

| Semi-implicit Euler | (\mathbf{v}(t+\Delta t) = \mathbf{v}(t) + \Delta t \mathbf{a}(t)) (\mathbf{r}(t+\Delta t) = \mathbf{r}(t) + \Delta t \mathbf{v}(t+\Delta t)) | Better stability than explicit Euler | Still exhibits energy drift | (\mathcal{O}(\Delta t)) |

| Verlet | (\mathbf{r}(t+\Delta t) = 2\mathbf{r}(t) - \mathbf{r}(t-\Delta t) + \Delta t^2 \mathbf{a}(t)) | No explicit velocity, high stability | Not self-starting, velocity estimation needed | (\mathcal{O}(\Delta t^4)) position, (\mathcal{O}(\Delta t^2)) velocity |

| Velocity Verlet | (\mathbf{r}(t+\Delta t) = \mathbf{r}(t) + \Delta t \mathbf{v}(t) + \frac{\Delta t^2}{2} \mathbf{a}(t)) (\mathbf{v}(t+\Delta t) = \mathbf{v}(t) + \frac{\Delta t}{2}[\mathbf{a}(t) + \mathbf{a}(t+\Delta t)]) | Explicit velocity, high accuracy | Slightly more complex implementation | (\mathcal{O}(\Delta t^2)) |

| Leapfrog | (\mathbf{v}(t+\frac{\Delta t}{2}) = \mathbf{v}(t-\frac{\Delta t}{2}) + \Delta t \mathbf{a}(t)) (\mathbf{r}(t+\Delta t) = \mathbf{r}(t) + \Delta t \mathbf{v}(t+\frac{\Delta t}{2})) | Excellent stability, simple form | Velocities and positions at different times | (\mathcal{O}(\Delta t^2)) |

The relationship between the various integration algorithms and their evolution from basic Newtonian mechanics can be visualized as follows:

Diagram Title: Evolution of Integration Algorithms

Applications in Drug Discovery and Pharmaceutical Development

Target Validation and Characterization

Molecular dynamics simulations play a crucial role in the early stages of drug discovery by providing atomic-level insights into the dynamics and function of potential drug targets [19]. For example, MD studies of sirtuins, RAS proteins, and intrinsically disordered proteins have revealed conformational dynamics and allosteric mechanisms that would be difficult to characterize experimentally [19]. The Verlet algorithm provides the numerical foundation for these simulations, enabling the observation of rare events and conformational transitions that occur on timescales ranging from picoseconds to microseconds.

Ligand Binding Energetics and Kinetics

During lead discovery and optimization phases, MD simulations facilitate the evaluation of binding energetics and kinetics of ligand-receptor interactions [19]. Advanced sampling techniques based on MD trajectories enable the calculation of binding free energies ((\Delta G_{bind})), guiding the selection of candidate molecules with optimal affinity and specificity [18]. The numerical stability of the Verlet algorithm is particularly important for these applications, as artifacts in the integration can propagate into errors in the calculated thermodynamic properties.

Membrane Protein Simulations

Many pharmaceutically relevant targets are membrane proteins, including G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) and ion channels [19] [22]. MD simulations incorporating explicit lipid bilayers provide crucial insights into the mechanism of action of drugs targeting these proteins and their interactions with the complex membrane environment [22]. The Verlet integrator's conservation properties are essential for these heterogeneous systems, where different time scales and force characteristics coexist.

Pharmaceutical Formulation Development

Beyond target engagement, MD simulations play an emerging role in pharmaceutical formulation development, including the study of crystalline and amorphous solids, drug-polymer formulations, and nanoparticle drug delivery systems [19]. The ability to simulate the dynamic behavior of these complex materials at the atomic level enables rational design of formulations with optimized stability, solubility, and release characteristics.

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Molecular Dynamics Simulations

| Tool Category | Examples | Function | Relevance to Integration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Force Fields | AMBER, CHARMM, GROMOS | Parameterize interatomic interactions | Determine forces for Verlet integration |

| Simulation Software | GROMACS, NAMD, AMBER, CHARMM | Implement integration algorithms and force calculations | Provide optimized Verlet implementation |

| Analysis Tools | VMD, MDAnalysis, CPPTRAJ | Process trajectories and calculate properties | Extract meaningful data from integrated trajectories |

| Specialized Hardware | GPUs, Anton Supercomputer | Accelerate force calculations and integration | Enable longer time steps and simulation times |

| Structure Databases | Protein Data Bank, PubChem | Provide initial atomic coordinates | Supply starting structures for integration |

Current Challenges and Future Directions

Despite significant advances, molecular dynamics simulations face several persistent challenges that influence the implementation and application of numerical integration methods. The high computational cost of simulations remains a limiting factor, restricting routine simulations to timescales on the order of microseconds for most biologically relevant systems [18]. While specialized hardware such as Anton supercomputers and GPU acceleration have extended accessible timescales, the exponential growth of conformational space with system size continues to present sampling challenges [18].

Approximations inherent in classical force fields represent another significant limitation, particularly the neglect of electronic polarization effects and quantum mechanical phenomena such as bond breaking and formation [18]. While polarizable force fields are under active development, their computational cost and complexity have limited widespread adoption [18]. Hybrid quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) approaches provide a compromise for simulating chemical reactions in biomolecular contexts but introduce additional complexity into the integration scheme [18].

Recent trends in molecular dynamics methodology include the development of machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) that can accelerate simulations while maintaining quantum-level accuracy [17]. These approaches train on quantum mechanical data and can predict atomic energies and forces with remarkable efficiency, potentially revolutionizing the field of molecular simulation [17]. The integration of these potentials with traditional Verlet integration schemes represents an active area of research.

Enhanced sampling methods such as accelerated molecular dynamics (aMD) manipulate the potential energy surface to reduce energy barriers and accelerate conformational transitions [18]. These techniques introduce additional considerations for numerical integration but substantially improve the efficiency of phase space sampling for complex biomolecular systems.

As computational power continues to grow and algorithms become more sophisticated, the role of molecular dynamics simulations and the Verlet integration method in drug discovery and pharmaceutical development is likely to expand, providing increasingly accurate insights into the atomic-scale mechanisms underlying biological function and therapeutic intervention.

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the conservation of energy and the long-term stability of the numerical integration are paramount for generating physically meaningful trajectories. The core of this challenge lies in the choice of integration algorithm—the mathematical method that calculates how atomic positions and velocities evolve over time. While simple algorithms may be computationally inexpensive, they can introduce numerical errors that cause the total energy of the system to drift, rendering the simulation non-physical and invalidating its results. This technical guide explores the fundamental role of symplectic integrators in mitigating this problem. Designed to preserve the geometric structure of Hamiltonian mechanics, these algorithms ensure excellent long-term energy conservation, even over very long simulation timescales. Their application is a critical component of reliable MD workflows, which are increasingly used for actionable predictions in fields like drug discovery and advanced materials design [25].

Fundamentals of Energy Conservation and Numerical Integration

The Hamiltonian Framework and Phase Space

Classical molecular dynamics simulations are built upon Hamiltonian mechanics. For a system of N particles, the Hamiltonian ( H ) represents the total energy, which is the sum of the kinetic energy ( K ) and potential energy ( U ):

[ H(\vec{p}, \vec{r}) = K(\vec{p}) + U(\vec{r}) ]

where ( \vec{r} ) and ( \vec{p} ) are the positions and momenta of all particles, respectively. The equations of motion derived from the Hamiltonian are:

[ \frac{d\vec{r}i}{dt} = \frac{\partial H}{\partial \vec{p}i}, \quad \frac{d\vec{p}i}{dt} = -\frac{\partial H}{\partial \vec{r}i} ]

The set of all possible ( (\vec{r}, \vec{p}) ) defines the phase space of the system. A fundamental property of Hamiltonian dynamics is that the flow in phase space is symplectic, meaning it preserves the area (or volume) in phase space. A key consequence of this symplectic property is the conservation of energy in closed systems; the value of the Hamiltonian ( H ) remains constant over time [26].

The Challenge of Numerical Integration and Energy Drift

In practice, the equations of motion cannot be solved analytically for complex many-body systems. Instead, MD relies on numerical integration using finite time steps ( \Delta t ). Any numerical algorithm introduces errors, and a common pathology in non-symplectic methods is energy drift—a systematic increase or decrease in the total energy of the system over time. This drift is a sign that the simulation is no longer sampling from the correct thermodynamic ensemble (e.g., the microcanonical or NVE ensemble), which calls into question the validity of any computed properties [26] [27].

Furthermore, MD is a chaotic dynamical system, meaning it exhibits extreme sensitivity to initial conditions. This makes accurate predictions of individual trajectories impossible over long times. However, accurate and reproducible statistical averages of observables can still be obtained, provided the numerical integration is stable and the energy is well-conserved [25].

Symplectic Integrators: Principles and Algorithms

The Concept of Symplecticity

A symplectic integrator is a numerical scheme that preserves the symplectic two-form of the Hamiltonian system. In simpler terms, it produces a discrete mapping of the system from one time step to the next that, like the true Hamiltonian flow, conserves the area in phase space. While a symplectic integrator does not exactly conserve the true Hamiltonian ( H ) at every step, it does conserve a nearby shadow Hamiltonian ( \tilde{H} ) over exponentially long times. This results in bounded energy oscillations and no long-term energy drift, making these algorithms the gold standard for MD simulations [26].

The Velocity Verlet Algorithm

The most widely used symplectic integrator in MD is the Velocity Verlet algorithm. It updates positions and velocities as follows:

- ( \vec{v}(t + \frac{1}{2}\Delta t) = \vec{v}(t) + \frac{1}{2} \frac{\vec{F}(t)}{m} \Delta t )

- ( \vec{r}(t + \Delta t) = \vec{r}(t) + \vec{v}(t + \frac{1}{2}\Delta t) \Delta t )

- Calculate forces ( \vec{F}(t + \Delta t) ) from the new positions ( \vec{r}(t + \Delta t) )

- ( \vec{v}(t + \Delta t) = \vec{v}(t + \frac{1}{2}\Delta t) + \frac{1}{2} \frac{\vec{F}(t + \Delta t)}{m} \Delta t )

This algorithm is time-reversible and symplectic, providing excellent energy conservation properties [26].

Comparison of Common MD Integration Algorithms

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of several integration methods used in MD, highlighting the advantages of symplectic schemes.

Table 1: Comparison of Molecular Dynamics Integration Algorithms

| Algorithm | Symplectic? | Time-Reversible? | Global Error Order | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Velocity Verlet | Yes | Yes | ( O(\Delta t^2) ) | Excellent long-term energy conservation; simple to implement. | Moderate accuracy per step. |

| Leapfrog | Yes | Yes | ( O(\Delta t^2) ) | Computationally efficient; good energy conservation. | Positions and velocities are not synchronized. |

| Euler | No | No | ( O(\Delta t) ) | Simplicity. | Severe energy drift; unstable for MD. |

| Runge-Kutta 4 | No | No | ( O(\Delta t^4) ) | High accuracy per step. | Not symplectic; can exhibit energy drift; computationally expensive. |

Quantifying Stability and Uncertainty in MD Simulations

The stability of an MD simulation is affected by two primary sources of error [25]:

- Systematic Errors: These arise from approximations in the model, such as the force field parameters, the treatment of long-range electrostatics, and the choice of boundary conditions. For example, different protein force fields can inherently favor different secondary structures [25].

- Random (Stochastic) Errors: These are intrinsic to the chaotic nature of MD. Round-off errors from floating-point arithmetic, while seemingly negligible, can cause numerical irreversibility. Research using a "bit-reversible algorithm" has shown that even small numerical noise can lead to irreversibility in N-body systems, and the extent of this irreversibility is related to the "quantity" of the controlled noise [27].

Uncertainty Quantification through Ensemble Simulation

To achieve reproducible and actionable results, it is essential to quantify the uncertainty in MD predictions. A standard approach in uncertainty quantification is the use of ensemble methods [25]. This involves running a sufficiently large number of independent replica simulations (e.g., with slightly perturbed initial conditions) concurrently. Statistics derived from the ensemble provide reliable error estimates for computed observables.

Table 2: Experimental Protocol for Ensemble Uncertainty Quantification

| Step | Protocol Description | Purpose & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| 1. System Preparation | Prepare the initial molecular system (e.g., protein-ligand complex) in a simulation box with solvent and ions. | To create a physiologically relevant starting model for the simulation. |

| 2. Ensemble Initialization | Generate N independent initial configurations (replicas) by assigning different random seeds for initial velocities. | To sample a representative set of initial conditions from the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution. |

| 3. Equilibration | Run a short equilibration simulation (e.g., NVT followed by NPT) for each replica using a symplectic integrator (e.g., Velocity Verlet). | To relax the system to the desired thermodynamic state (temperature and pressure) before production runs. |

| 4. Production Simulation | Run a long production simulation for each replica, saving trajectories for analysis. The use of a symplectic integrator is critical here. | To generate statistically independent trajectories for computing ensemble averages. |

| 5. Analysis | Calculate the quantity of interest (QoI), such as binding free energy or root-mean-square deviation, from each replica. Compute the mean and standard deviation across the ensemble. | To obtain a reliable estimate of the QoI and its associated uncertainty, enabling probabilistic decision-making. |

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Dynamics Simulations

| Item | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Biomolecular Force Fields (e.g., AMBER, CHARMM) | A set of mathematical functions (potential energy functions) and parameters that describe the potential energy of a system of particles. They define the interactions between atoms and are fundamental to the model's accuracy [26]. |

| Explicit Solvent Model (e.g., TIP3P, SPC/E water) | A collection of water molecules explicitly included in the simulation box to solvate the solute (e.g., protein). This provides a more realistic representation of the biological environment compared to implicit solvents [25]. |

| Thermostat (e.g., Nosé-Hoover, Langevin) | An algorithmic "bath" that couples the system to a desired temperature. It stochastically or deterministically adjusts particle velocities to maintain the correct thermodynamic ensemble [26]. |

| Barostat (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman) | An algorithmic "piston" that adjusts the simulation box size to maintain a constant pressure, mimicking experimental conditions [26]. |

| Long-Range Electrostatics Method (e.g., PME, PPPM) | A numerical technique to efficiently compute the long-range Coulomb interactions, which are crucial for the structural stability of biomolecules. Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) is a standard choice [26]. |

Workflow for Stable and Reproducible MD Simulations

The following diagram illustrates a robust workflow for setting up and running MD simulations, emphasizing steps that ensure stability and allow for proper uncertainty quantification.

MD Stability and UQ Workflow

The use of symplectic integrators, most notably the Velocity Verlet algorithm, is a foundational practice for ensuring the energy conservation and long-term stability of molecular dynamics simulations. By preserving the geometric properties of Hamiltonian dynamics, these algorithms prevent the non-physical energy drift that can invalidate simulation results. However, stability is not solely determined by the integrator. A comprehensive approach must also account for force field accuracy, appropriate thermodynamic control, and the intrinsic chaos of molecular systems. The implementation of ensemble-based uncertainty quantification is therefore critical for transforming MD from a tool for post-hoc rationalization into a method capable of producing reproducible, actionable predictions. This rigorous framework for stability and error analysis is what underpins the growing use of MD in high-stakes industrial applications, such as rational drug design and materials discovery [25].

From Atoms to Insights: The MD Workflow and Its Biomedical Applications

Within the broader thesis of how molecular dynamics (MD) simulation works, system preparation is the critical first step that determines the success or failure of all subsequent computational analysis. MD simulation functions as a "computational microscope," studying the dynamic evolution of molecules by moving atoms according to classical laws of motion [28] [29]. The accuracy of this dynamic representation hinges entirely on the quality of the initial structural model and its compatibility with the chosen force field [30] [28]. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, rigorous system preparation enables the investigation of biological functions, protein-ligand interactions, and conformational changes with atomic-level precision [31] [29]. This guide provides comprehensive methodologies for constructing and validating molecular systems to ensure physically accurate and scientifically meaningful simulations.

Initial Structure Selection and Preparation

Source Selection and Critical Assessment

The process begins with selecting an appropriate initial structure, which must be carefully chosen considering the simulation's purpose and the system's biological and chemical characteristics [28].

- Experimental Structures: Structures from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) provide excellent starting points but require thorough inspection. Check for missing atoms, residues, and the presence of non-standard amino acids or small ligands [28]. For crystal structures, consult the PDB_REDO database for refined versions that address common problems like side-chain orientation uncertainties [28].

- Idealized Construction: For peptides or where experimental structures are unavailable, generating ideal conformations (e.g., helical, sheet, polyproline-2) using tools like PyMOL's

build_seqscript orfabcommand is a valid approach [28]. - Structure Completion: Use tools like MODELLER to rebuild any missing residues or atoms (except hydrogens) [28]. Remove crystallographic water molecules unless they are directly relevant to the study, as they can typically be removed with simple command-line tools [28].

Structure Optimization and Protonation

- Quality Checks: Run additional quality checks to correct common issues. This includes optimizing the orientation of glutamine and asparagine side chains and assigning proper protonation states based on the physiological pH, which crucially influences the hydrogen-bonding network [28].

- Manual Building: In some cases, manual manipulation with software like Coot may be necessary to correct structural anomalies, such as removing strand swaps that prevent proper protein dynamics [32].

Table 1: Common Initial Structure Issues and Resolution Strategies

| Issue Type | Detection Method | Resolution Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Missing atoms/residues | Visual inspection, PDB header | MODELLER, WHATIF server [28] |

| Incorrect side-chain rotamers | PDB_REDO, WHATIF server | PDB_REDO database, manual refinement [28] |

| Non-standard molecules | PDB HETATM records | Removal with sed/text editing, manual parameterization [28] |

| Missing flexible linkers | Comparison with sequence data | MODELLER, manual building [32] |

| Improper protonation | Calculation of pKa values | Tools like WHATIF to set states for physiological pH [28] |

Force Field Selection and Topology Generation

Choosing an Appropriate Force Field

The force field describes how particles within the system interact and is a non-trivial choice that must be appropriate for both the system being studied and the property or phenomena of interest [30]. Major force fields include CHARMM, AMBER, GROMOS, and OPLS, each with different parameterizations and propensities [28]. For instance, the AMBER99SB-ILDN force field is widely used in sampling and folding simulations as it has been shown to reproduce experimental data fairly well [28]. The choice may also be influenced by the simulation software [30].

Topology and Parameter Generation

A molecule is defined not only by its 3D coordinates but also by a description of its atom types, charges, bonds, and interaction parameters contained in the topology file [28].

- Standard Biomolecules: Tools like