Molecular Evolutionary Ecology: From Genomic Mechanisms to Biomedical Innovation

This article synthesizes the molecular foundations of evolutionary ecology and their critical applications in drug discovery and biomedical research.

Molecular Evolutionary Ecology: From Genomic Mechanisms to Biomedical Innovation

Abstract

This article synthesizes the molecular foundations of evolutionary ecology and their critical applications in drug discovery and biomedical research. It explores the genetic mechanisms driving speciation and adaptation, examines methodologies for translating evolutionary principles into therapeutic strategies, addresses key research challenges, and establishes validation frameworks. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, the content highlights how evolutionary concepts can inform target identification, combat antibiotic resistance, and leverage natural products, ultimately providing a roadmap for harnessing evolutionary principles to solve complex biomedical problems.

Genetic Mechanisms of Speciation and Ecological Adaptation

Hybrid incompatibility, the phenomenon where offspring from interspecific crosses are inviable or sterile, constitutes a fundamental reproductive barrier in evolutionary biology [1]. Charles Darwin himself recognized the paradox that natural selection tolerates the development of these highly disadvantageous traits, a puzzle that continues to drive research today [2]. The genetic basis of these incompatibilities provides critical insight into the mechanisms of speciation and the evolutionary forces that drive reproductive isolation [3] [4].

The Dobzhansky-Muller model represents the cornerstone of our modern understanding of how these incompatibilities evolve without passing through unfit intermediate stages [5] [3]. This model explains how alleles that are functionally fine within their respective species genomes can cause catastrophic failures when brought together in hybrid organisms [5] [6]. Recent advances in genomics, molecular biology, and biochemistry have revolutionized our understanding of these processes, revealing complex interactions from the molecular to the organismal level [7] [4] [2].

This review synthesizes nearly a century of research on hybrid incompatibilities, from the foundational Dobzhansky-Muller model to contemporary genomic investigations. We examine the genetic architecture of reproductive isolation, explore molecular mechanisms underlying hybrid breakdown, and detail experimental approaches for identifying and characterizing speciation genes. The integration of evolutionary genetics with modern molecular techniques continues to unveil the intricate processes through which genetic incompatibilities arise and drive species formation.

Historical Foundations and Theoretical Framework

The Dobzhansky-Muller Model

The Dobzhansky-Muller model, independently formulated by Theodosius Dobzhansky and Hermann Joseph Muller in the 1930s and early 1940s, provided an elegant solution to a fundamental evolutionary puzzle: how could hybrid inviability or sterility evolve without passing through unfit intermediate stages [3]? The model emerged from their genetic studies on Drosophila species, where they recognized that hybrid incompatibility was unlikely to arise from a single genetic change [3].

The core insight of the Dobzhansky-Muller model is that hybrid incompatibility results from interactions between multiple genetic changes that accumulate in diverging populations [5] [3]. In the simplest scenario, consider an ancestral population with genotype AABB at two loci. If this population splits into two isolated populations, one might fix the derived allele A* while the other fixes B* through independent evolutionary paths. While the evolutionary trajectories AAbb and aaBB remain viable within their respective populations, hybrids with the AaBb genotype (or Aa if we consider diploid organisms) experience the first-ever combination of A* and B* alleles, which may prove incompatible [5] [3].

This model elegantly resolves the evolutionary paradox because neither population passes through an unfit heterozygous stage during their divergence [3]. The incompatible combination only appears when previously isolated genotypes are brought together through hybridization, explaining how reproductive barriers can emerge as a by-product of divergence rather than through direct selection for incompatibility itself [3] [1].

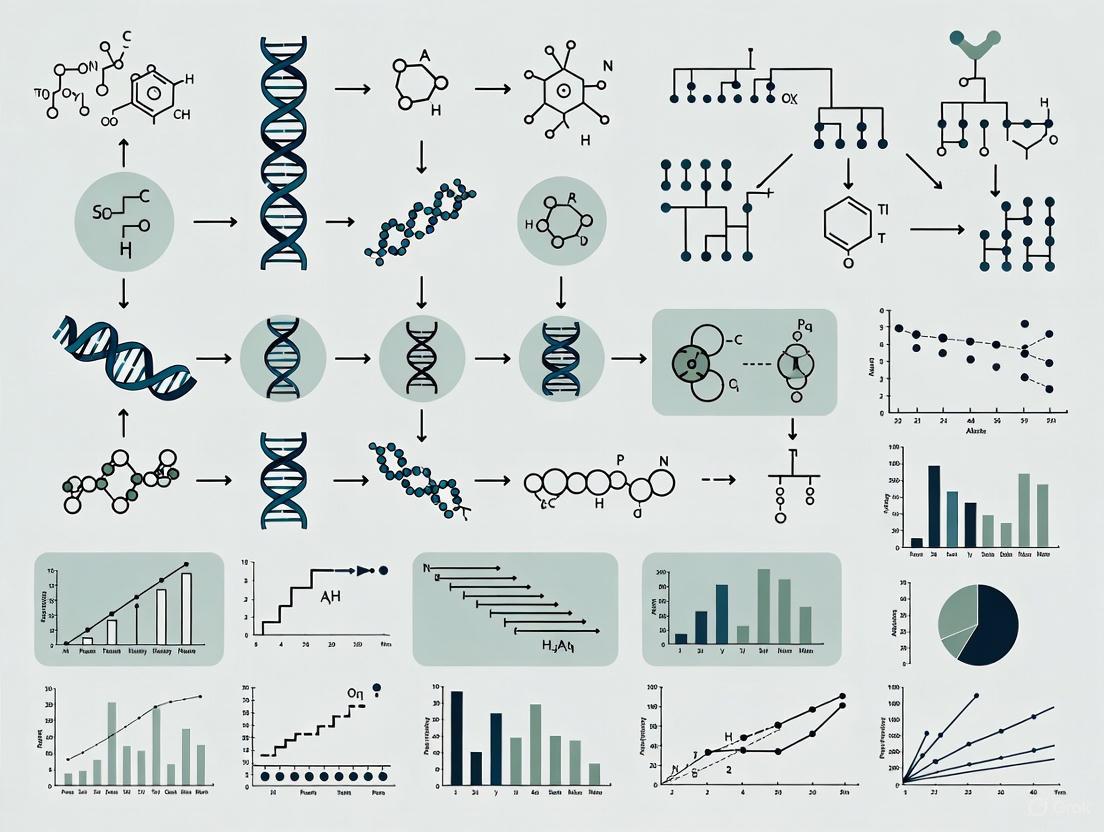

Figure 1: The Dobzhansky-Muller Model of Hybrid Incompatibility. Two populations diverge from a common ancestor through independent evolutionary paths. While each derived genotype remains viable within its population, their hybrid expresses a novel, incompatible combination of alleles.

Theoretical Extensions and the "Snowball Effect"

The original two-locus Dobzhansky-Muller model has been expanded through theoretical work that explores more complex genetic scenarios. A pivotal extension is the "snowball effect," which predicts that the number of genetic incompatibilities between diverging taxa increases faster than linearly with time [7] [8]. Specifically, the probability of speciation increases at least as fast as the square of the time since separation [8].

This non-linear accumulation occurs because as genomes diverge, each new incompatible substitution has the potential to interact negatively not only with its specific partner locus but with multiple loci across the genome [7]. The snowball model has received empirical support from genetic mapping data in Drosophila and Solanum species, demonstrating that weak Dobzhansky-Muller incompatibilities can indeed accumulate and strengthen genetic barriers between species [7].

Another significant theoretical extension addresses the role of natural selection in driving the evolution of incompatibilities. When populations adapt to identical environments, the probability of evolving Dobzhansky-Muller incompatibilities depends on the selection coefficients among beneficial alleles [6]. If one locus is under much stronger selection than another, both populations are likely to substitute the same allele first, precluding the development of an incompatibility [6]. This mathematical insight helps explain why adaptation to identical environments may less frequently yield hybrid incompatibilities compared to adaptation to different environments.

Molecular Mechanisms of Hybrid Incompatibility

Protein Complexes and Multi-Locus Incompatibilities

Multi-protein complexes represent a fundamental organizational principle of cellular function, and their disruption provides a powerful mechanism for hybrid incompatibility [7]. Proteins typically execute their functions through interactions with other proteins, forming complexes whose composition can change in response to environmental cues or evolutionary pressures [7]. When species diverge, compensatory mutations may accumulate in different components of these complexes, maintaining function within species but causing failure in hybrids where novel combinations occur [7].

This perspective helps explain why many hybrid incompatibilities involve multiple genes rather than simple pairwise interactions [7]. The admixture of protein subunits from different parental origins in hybrids can disrupt the precise stoichiometries and interaction interfaces required for proper complex assembly and function [7]. Understanding the dynamics of protein-protein interactions leading to multi-protein complexes thus provides a framework for characterizing multi-locus incompatibilities that are difficult to study with traditional genetic approaches [7].

Cyto-Nuclear Incompatibilities

Cyto-nuclear incompatibilities, particularly those involving mitochondrial-nuclear interactions, represent a major category of hybrid dysfunction [7]. In yeast, almost all known cases of Dobzhansky-Muller incompatibilities involve mitochondrial-nuclear interactions [7]. These incompatibilities often become evident only under specific environmental conditions, such as when hybrids of obligate fermentative yeast are forced to respire in non-fermentative carbon sources [7].

The prevalence of cyto-nuclear incompatibilities stems from the intimate functional integration between nuclear-encoded genes and their mitochondrial targets [7]. As mitochondrial genomes and nuclear genomes co-evolve, they accumulate compensatory changes that maintain respiratory function. When hybridization disrupts these co-adapted complexes, oxidative phosphorylation may fail, leading to hybrid inviability or sterility [7]. Similar cyto-nuclear incompatibilities have been documented across diverse taxa including plants and animals, highlighting their general importance in reproductive isolation [7].

Genomic Conflicts and Epigenetic Regulation

Genomic conflicts, particularly those involving selfish genetic elements, represent another potent source of hybrid incompatibility [7] [4] [2]. These conflicts can drive rapid coevolution between suppressors and driving elements within populations, resulting in divergent evolutionary trajectories between species [4]. When hybrids form, the finely balanced systems of suppression may break down, leading to hybrid dysfunction [4].

Epigenetic mechanisms have also emerged as important contributors to hybrid incompatibility [1] [4]. The Lynch-Force model proposes that gene duplication followed by divergent resolution can lead to hybrid problems [1]. When redundant genes become non-functional through mutations in different lineages, hybrids may lack functional copies of essential genes [1]. Epigenetic regulation, particularly through small RNA pathways, can further contribute to hybrid incompatibility when the precise regulatory balance is disrupted in hybrids [1] [4]. Studies in Capsella have demonstrated that dosage of maternal small-interfering RNAs can cause hybrid incompatibility between closely related plant species [1].

Table 1: Molecular Mechanisms of Hybrid Incompatibility

| Mechanism | Molecular Basis | Example Systems | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Complex Disruption | Altered stoichiometry or interaction interfaces in multi-protein complexes | Yeast, Drosophila | [7] |

| Cyto-Nuclear Incompatibility | Disrupted co-adaptation between mitochondrial and nuclear genomes | Yeast, plants, animals | [7] |

| Genomic Conflict | Breakdown of suppression systems for selfish genetic elements | Drosophila, mice | [7] [4] |

| Epigenetic Dysregulation | Disruption of imprinting or small RNA pathways | Arabidopsis, Capsella | [1] [4] |

| Gene Duplication & Divergence | Loss of essential function through complementary gene loss | Plants, animals | [1] |

Genetic Architecture and Experimental Approaches

Genetic Architecture of Speciation

The genetic architecture of hybrid incompatibility—the number, effect sizes, and interactions of genes involved—has profound implications for speciation dynamics [3] [9]. Early genetic mapping studies in Drosophila revealed that even between closely related species, dozens or even hundreds of genes can contribute to hybrid sterility [3]. For instance, in the Drosophila simulans clade, an estimated 100 genes contribute to male hybrid sterility [3].

The relationship between genetic architecture and reproductive isolation is complex. Research using polygenic models has shown that populations evolving independently under stabilizing selection experience suites of compensatory allelic changes that maintain high fitness within populations but cause incompatibilities in hybrids [9]. Interestingly, reduced fitness in F1 hybrids evolves primarily at intermediate strengths of epistatic interactions, while F2 and backcross hybrids show reduced fitness across weak and moderate strengths of epistasis due to segregation variance [9].

Another important architectural feature is that hybrid incompatibilities are often asymmetric—they affect hybrid fitness differently depending on the direction of the cross [4]. This asymmetry reflects the complex epistatic interactions underlying reproductive isolation and has important implications for gene flow between species [4].

The Introgression Approach

The introgression approach, pioneered by Jerry Coyne, H. Allen Orr, and Chung-I Wu, enables fine-scale genetic mapping of factors contributing to hybrid incompatibility [3]. This method involves creating a series of introgression lines where small chromosomal segments from one species are placed into the genetic background of another through repeated backcrosses [3].

The process begins with the creation of F1 hybrids between two species, which are then repeatedly backcrossed to one parental species while using genetic markers to track introgressed segments [3]. The fertility or viability of males from these introgression lines is then quantitatively assessed [3]. Because males from a given introgression line are relatively genetically homogeneous, this approach allows researchers to associate specific chromosomal regions with hybrid incompatibility phenotypes [3].

This technique has been refined over time with increasingly precise molecular markers, from visible markers to restriction fragment length polymorphisms (RFLPs) and microsatellites, and more recently to whole-genome sequencing [3]. The introgression approach ultimately enables researchers to map hybrid incompatibility factors to increasingly smaller genomic regions, facilitating the identification of specific genes involved [3].

Figure 2: Introgression Mapping Workflow. This experimental approach enables fine-scale genetic mapping of hybrid incompatibility factors through repeated backcrossing and marker-assisted selection.

Deficiency Mapping and Positional Cloning

Deficiency mapping provides a complementary approach to identify hybrid incompatibility genes [3]. This method utilizes strains with known chromosomal deletions to map the location of incompatibility factors [3]. When a deletion fails to complement a hybrid incompatibility phenotype, the responsible gene must reside within the deleted region [3].

The process involves crossing hybrids with various overlapping chromosomal deficiencies and assessing the resulting phenotypes [3]. Viable and inviable hybrids with different chromosome deletions are typed for molecular markers that are polymorphic between the species [3]. The pattern of marker distribution among different hybrids allows researchers to map the location of hybrid incompatibility genes with resolution dependent on the concentration of informative markers in the region [3].

With the advent of next-generation sequencing, positional cloning has become increasingly powerful for pinpointing specific genes responsible for hybrid incompatibilities [3] [4]. After mapping a region to a small interval using introgression or deficiency mapping, researchers can sequence the candidate region, identify genes, and validate candidates through transgenic approaches [4].

Table 2: Experimental Methods for Identifying Hybrid Incompatibility Genes

| Method | Principle | Resolution | Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Introgression Mapping | Repeated backcrossing with marker selection | ~1 cM | Drosophila species, plants | Time-consuming, limited to viable backcrosses |

| Deficiency Mapping | Complementation testing with deletions | Gene-level | Drosophila, other model systems | Requires deficiency stocks |

| Positional Cloning | Fine mapping followed by sequencing | Nucleotide-level | Systems with genomic resources | Requires high-quality genomes |

| GWAS Approaches | Genome-wide association in hybrid zones | Varies | Natural hybrid zones | Requires large sample sizes |

| Transcriptomics | Gene expression profiling in hybrids | System-level | Any system | Correlation vs. causation |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Hybrid Incompatibility Studies

| Reagent/Category | Function/Application | Examples/Specifics |

|---|---|---|

| Introgression Lines | Fine-scale mapping of incompatibility factors | Drosophila simulans/mauritiana lines [3] |

| Deficiency Stocks | Deletion mapping to localize incompatibility genes | Drosophila deletion kits [3] |

| Molecular Markers | Tracking genomic segments in mapping studies | RFLPs, microsatellites, SNPs [3] |

| Genomic Resources | Reference sequences for positional cloning | Genome assemblies for model systems [4] |

| Transgenic Systems | Functional validation of candidate genes | P-element transformations (Drosophila), CRISPR-Cas9 [4] |

| Protein Interaction Assays | Testing molecular mechanisms of incompatibility | Yeast two-hybrid, co-immunoprecipitation [7] |

| Transcriptomic Tools | Assessing gene expression in hybrids | RNA-seq, microarrays [4] |

| Mitochondrial Mutants | Studying cyto-nuclear incompatibilities | ρ⁰ strains in yeast [7] |

Evolutionary Forces and Future Directions

Evolutionary Drivers of Incompatibility

The evolutionary forces driving the accumulation of hybrid incompatibilities have been extensively debated [6] [4]. Both neutral and selective processes can contribute, with molecular evolutionary analyses of identified speciation genes increasingly revealing signatures of positive selection [6] [4].

Natural selection can drive the evolution of Dobzhansky-Muller incompatibilities in two primary ways [6]. First, allopatric populations may adapt to different environments, with hybrid problems arising as a pleiotropic side effect [6]. Second, populations adapting to identical environments may arrive at different genetic solutions to the same selective challenge, resulting in incompatible gene combinations in hybrids [6]. However, mathematical models show that when selection coefficients among beneficial alleles differ substantially, both populations are likely to substitute the same allele first, reducing the probability of incompatibility [6].

Recent genomic analyses have highlighted the importance of intragenomic conflicts, particularly meiotic drive systems, as drivers of rapid evolution that can result in hybrid incompatibilities [4] [2]. These conflicts create perpetual evolutionary arms races that lead to divergent changes between populations, which may become incompatible upon hybridization [4].

Emerging Research Frontiers

Several exciting frontiers are emerging in hybrid incompatibility research. The role of biomolecular condensates—membrane-less organelles that organize cellular processes—represents a promising new direction [2]. These molecular structures may be responsible for incompatibilities between species, as their proper assembly often depends on precise interaction networks that can be disrupted in hybrids [2].

The integration of modern genomic tools with traditional genetic approaches is accelerating the pace of discovery [4]. As genomic resources become available for more non-model organisms, researchers can leverage natural variation to identify incompatibility genes across diverse taxonomic groups [7] [4]. This expansion beyond traditional model systems will provide a more comprehensive understanding of the general principles governing hybrid incompatibility.

Finally, the development of more sophisticated theoretical models that incorporate complex genomic architectures, selection regimes, and demographic histories will enhance our ability to interpret empirical findings [10] [9]. These models, informed by growing datasets of identified incompatibility genes, will help reconcile theoretical predictions with molecular observations, ultimately providing a unified framework for understanding how reproductive isolation evolves [4] [9].

The study of hybrid incompatibilities has progressed dramatically from the foundational insights of Dobzhansky and Muller to contemporary molecular investigations. The Dobzhansky-Muller model remains the central paradigm for understanding how reproductive isolation evolves without passing through unfit intermediates, while modern genomics has revealed the astonishing complexity of genetic architectures underlying speciation.

Key advances include the recognition that protein complexes, cyto-nuclear interactions, genomic conflicts, and epigenetic regulation all contribute to hybrid breakdown. Experimental approaches such as introgression mapping and deficiency analysis have enabled the identification of specific genes involved, revealing signatures of positive selection and diverse molecular mechanisms. The "snowball effect" theory has been validated empirically, showing that incompatibilities accumulate non-linearly with divergence time.

Future research will likely focus on emerging areas such as biomolecular condensates, expand to non-model organisms using genomic tools, and develop more sophisticated theoretical models. As these efforts proceed, our understanding of hybrid incompatibility will continue to refine, providing deeper insights into one of nature's most fundamental processes: the origin of species.

Intragenomic Conflict and Arms Races as Drivers of Molecular Evolution

Intragenomic conflict arises when selfish genetic elements evolve mechanisms to bias their transmission at a cost to organismal fitness, triggering evolutionary arms races that shape fundamental aspects of genome architecture and function. This whitepaper examines the molecular mechanisms and evolutionary consequences of these conflicts, focusing on meiotic drive systems as primary models. We synthesize findings from recent studies in Drosophila that reveal how genetic conflicts drive rapid evolution of heterochromatin regulation, centromere function, and DNA repair pathways. The documented molecular diversity stems from repeated cycles of adaptation and counter-adaptation between selfish elements and host suppressor systems, representing a significant engine of evolutionary innovation with implications for understanding genome stability and developmental processes.

Intragenomic conflict represents a fundamental departure from standard Mendelian inheritance, where certain genetic elements "cheat" by manipulating cellular processes to enhance their transmission. These selfish genetic elements, including transposable elements, meiotic drivers, and selfish chromosomes, gain transmission advantages often at the expense of organismal fitness [11]. The resulting conflicts create persistent evolutionary tensions that fuel rapid molecular evolution through several mechanisms:

- Evolutionary Arms Races: Selfish elements and host genomes engage in reciprocal adaptation, driving accelerated evolution of proteins involved in genome defense [11] [12].

- Genome Restructuring: Conflicts often lead to chromosomal rearrangements, gene duplications, and expansion of repetitive elements as byproducts of the struggle between drive and suppression [11].

- Molecular Innovation: The need to control selfish elements can lead to the evolution of novel regulatory mechanisms, including RNAi pathways and epigenetic silencing systems [13].

Within evolutionary ecology, understanding these conflicts provides a mechanistic explanation for the surprising molecular diversity underlying conserved cellular functions across taxa, challenging the notion of optimized, singular solutions to biological problems [13].

Molecular Mechanisms of Meiotic Drive

The Paris Sex-Ratio System inDrosophila simulans

The Paris sex-ratio (SR) system represents a well-characterized example of meiotic drive where X-linked elements manipulate gametogenesis to achieve transmission advantage. This system demonstrates the complex molecular interplay characteristic of intragenomic conflicts [11] [12].

Table 1: Key Genetic Elements in the Paris SR System

| Genetic Element | Location | Molecular Identity | Proposed Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| HP1D2SR | X chromosome | Dysfunctional allele of heterochromatin protein HP1D2 | Originates from duplication of autosomal HP1D/Rhino; binds Y chromosome in spermatogonia |

| DPSR | X chromosome | Tandem duplication (~6 genes + junction region) | Contains Trf2 gene and Hosim1 transposable element repeats; potential regulator of Y heterochromatin |

| rIST | Within DPSR | Rearranged segment of second intron of Trf2 | Unknown regulatory function |

The molecular mechanism involves epistatic interactions between HP1D2SR and elements within the DPSR duplication. Current evidence suggests these components collectively mis-regulate Y chromosome heterochromatin during spermatogenesis, leading to non-disjunction of Y sister chromatids during meiosis II and consequent failure of Y-bearing sperm to develop into functional gametes [11]. The result is a strongly female-biased progeny (>90%), providing the transmission advantage to the driving X chromosome.

Figure 1: Molecular pathway of the Paris sex-ratio meiotic drive system. The driving X chromosome (XSR) carries two key elements (HP1D2SR and DPSR) that interact to disrupt Y chromosome heterochromatin, ultimately leading to elimination of Y-bearing sperm.

Emerging Themes in Drive Mechanisms

Research across multiple Drosophila drive systems reveals consistent molecular themes despite diverse genetic origins:

- Heterochromatin Targeting: Multiple drive systems, including Paris SR and Segregation Distorter, interface with heterochromatin regulation, suggesting this represents an evolutionary vulnerability in gametogenesis [12].

- Gene Duplication Origins: Most known meiotic drivers originate from gene duplication events, allowing one copy to maintain original function while the other evolves selfish properties [12].

- Small RNA Pathways: Several drive systems implicate small RNA pathways in their mechanisms, connecting selfish elements to conserved genomic defense systems [12].

- Developmental Timing: Drivers often act during specific developmental windows, with some expressed in spermatogonia but effects manifesting later during meiosis or spermiogenesis [12].

Experimental Approaches for Studying Genetic Conflict

Evolutionary Repair Experiments

Evolutionary repair experiments represent a powerful methodology for studying how molecular diversity emerges in response to genetic perturbation. This approach uses laboratory evolution to compensate for deleted or altered genes, revealing alternative molecular pathways that can perform essential cellular functions [13].

Table 2: Experimental Design Parameters for Evolutionary Repair Studies

| Parameter | Options | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Perturbation | Gene deletion, Gene swap (paralog/ortholog), Hypomorphic mutation | Determines severity of initial fitness defect and evolutionary constraints |

| Replication | 4-12 populations (standard), Hundreds (high-throughput) | Higher replication enables detection of parallel evolution |

| Duration | 100-1000 generations | Balance between adaptation to perturbation versus general lab conditions |

| Phenotypic Analysis | Growth rate, Competitive fitness, Metabolic flux, Gene expression | Multiple assays provide comprehensive view of adaptation |

| Genetic Analysis | Whole-genome sequencing, Bulk segregant analysis, Genetic reconstruction | Identifies causal mutations and epistatic interactions |

The general workflow involves: (1) introducing a defined genetic perturbation that reduces fitness by 10-90%, (2) evolving multiple replicate populations for hundreds of generations under controlled conditions, (3) sequencing evolved lineages to identify compensatory mutations, and (4) functionally validating causal mutations and their phenotypic effects [13].

Figure 2: Workflow for evolutionary repair experiments. This approach uses laboratory evolution to identify compensatory mutations that restore fitness after genetic perturbation, revealing alternative molecular implementations of conserved functions.

Molecular Phylogenetics in Conflict Studies

Molecular phylogenetic analyses provide essential tools for reconstructing the evolutionary history of conflict systems:

- Sequence Alignment and Model Testing: Multi-sequence alignment of conflict-associated genes followed by statistical testing to identify best-fitting substitution models [14].

- Tree Building Methods: Utilization of both distance-based (Neighbor-Joining) and character-based (Maximum Likelihood, Bayesian Inference) approaches to reconstruct phylogenetic relationships [14].

- Horizontal Gene Transfer Detection: Implementation of algorithms to identify and exclude sequences potentially affected by horizontal transfer, which can confound phylogenetic analysis of conflict systems [14].

These methods have been instrumental in tracing the evolutionary origins of meiotic drive components and understanding how conflict shapes gene family evolution across related species.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Studying Intragenomic Conflict

| Reagent / Method | Function/Application | Example Use in Conflict Research |

|---|---|---|

| CUT&Tag | Chromatin profiling using targeted tagmentation | Mapping protein-DNA interactions in drive systems [11] |

| RNA-seq | Transcriptome analysis | Identifying differentially expressed genes in drive-associated tissues [11] |

| Transgenesis | Introduction of modified genetic elements | Testing driver and suppressor function in native genomic context [11] |

| NanoCUT&RUN | High-resolution chromatin profiling | Visualizing telomeric and heterochromatic chromatin states [11] |

| Population Genomics | Analysis of genetic variation in natural populations | Tracking spread of drive elements and suppressor alleles [11] |

| Comparative Genomics | Cross-species sequence comparison | Identifying rapidly evolving regions under conflict-driven selection [11] |

| Cytological Analysis | Microscopy-based examination of cellular structures | Visualizing meiotic defects in drive systems [11] [12] |

Evolutionary and Ecological Implications

Centromere Evolution and Genetic Conflict

Centromeres represent a prime example of how intragenomic conflict shapes essential cellular structures. Despite their conserved function in chromosome segregation, both centromeric histone (CENP-A/CID) and the underlying DNA sequences evolve rapidly [11]. The centromere drive hypothesis proposes that stronger centromeres can bias their transmission during female meiosis, leading to evolutionary arms races between:

- Selfish Centromeres: Expanding centromeric repeats that enhance microtubule attachment [11].

- Suppressor Systems: Kinetochore proteins that evolve to neutralize transmission bias [11].

- Epigenetic Regulation: Changes in chromatin modification systems that stabilize centromere function [11].

This conflict explains the paradoxical combination of conserved function and rapid molecular evolution observed at centromeres across eukaryotes.

Impact on Genome Architecture

Intragenomic conflicts leave distinctive signatures on genome organization and structure:

- Heterochromatin Expansion: Repeats associated with drive targets (e.g., Responder locus in SD system) often expand due to their role in conflict [12].

- Chromosomal Inversions: Suppressed recombination through inversions maintains linkage between driver and resistant alleles [12].

- Gene Family Evolution: Duplication and diversification of conflict-related genes (e.g., HP1 family) creates genetic raw material for arms races [11] [12].

These genomic signatures provide paleontological records of past conflicts, even in systems where the active conflict has been resolved through fixation or suppression.

Research Applications and Future Directions

The study of intragenomic conflict provides not only fundamental insights into evolutionary processes but also practical applications:

- Gene Drive Development: Understanding natural drive mechanisms informs engineered gene drives for pest control and public health applications [12].

- Genome Stability Research: Conflict systems reveal vulnerabilities in chromosome segregation and DNA repair pathways relevant to disease states [11].

- Molecular Tool Development: Proteins evolved in conflict contexts (e.g., DNA-binding domains) provide novel reagents for biotechnology [13].

Future research directions should focus on integrating evolutionary repair experiments with natural variation studies, developing high-resolution methods for analyzing heterochromatic regions, and applying single-cell approaches to understand how conflicts play out within developing tissues.

The Role of Gene Duplication and Divergent Evolution in Creating New Functions

Gene duplication is a fundamental evolutionary mechanism supplying the raw genetic material for functional innovation. By creating genetic redundancy, where one gene copy can maintain the original function, duplication allows the other copy to accumulate mutations that may lead to the emergence of novel functions or the subdivision of ancestral functions [15]. This process of duplication and divergence has fueled biological complexity since the dawn of life, expanding the genome of the last universal common ancestor (LUCA), which contained approximately 500 genes, to the thousands of genes found in extant free-living organisms [16]. Within evolutionary ecology, understanding these molecular mechanisms is crucial for explaining how organisms adapt to changing environments, develop new ecological interactions, and evolve phenotypic diversity. This whitepaper provides a technical examination of the models, patterns, and experimental approaches for studying functional divergence after gene duplication, with particular relevance to ecological adaptation.

Theoretical Models of Gene Duplication and Divergence

Several mechanistic models explain how duplicated genes escape silencing or loss and instead acquire distinct functions over evolutionary time. These models differ primarily in the sequence of mutation events and the nature of selective pressures involved.

Classical and Contemporary Models

- Ohno's Neofunctionalization Model (MDN): The classical model proposes that after duplication, one copy remains under purifying selection to maintain the ancestral function, while the other accumulates mutations neutrally. Rarely, a beneficial mutation confers a novel, advantageous function, leading to its preservation [15]. A significant criticism is that non-functionalization through accumulation of deleterious mutations is far more likely than acquiring a beneficial new function [16] [17].

- Innovation-Amplification-Divergence (IAD) Model: This model addresses the limitations of Ohno's model. It posits that a promiscuous, low-level side activity of an enzyme first becomes physiologically relevant due to an environmental change or mutation elsewhere in the genome. Selection for this "innovation" favors gene amplification (increased copy number) to boost the beneficial activity. Subsequently, divergence occurs as mutations improve the efficiency of the new function in some copies, while others maintain the original activity [16] [15]. Amplification thus provides a temporary buffer, allowing divergence without loss of the original function.

- Subfunctionalization Models: These models involve the partitioning of the ancestral gene's functions between duplicates.

- Duplication-Degeneration-Complementation (DDC): In this neutral model, the ancestral gene is multifunctional. After duplication, both copies accumulate degenerative, loss-of-function mutations in different functional domains (e.g., regulatory elements or protein domains). Eventually, both copies become necessary to complement the full set of ancestral functions, preserving the duplication [15].

- Escape from Adaptive Conflict (EAC): This adaptive model applies when the ancestral gene is under simultaneous selection to optimize two distinct, incompatible functions—a state of "adaptive conflict." Gene duplication releases this conflict by allowing each copy to specialize and improve one of the two functions independently [15].

Table 1: Comparison of Major Evolutionary Models for Gene Duplication Fate

| Model | Key Mechanism | Selective Pressure | Key Distinguishing Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neofunctionalization (Ohno) | One copy acquires a new function | Positive selection on new function | Novel function arises post-duplication |

| Innovation-Amplification-Divergence (IAD) | Preexisting promiscuous activity is amplified and refined | Positive selection on preexisting minor function | Requires gene amplification before divergence |

| Subfunctionalization (DDC) | Complementary degeneration of subfunctions | Neutral mutations, then purifying selection | No novel functions; ancestral functions are partitioned |

| Escape from Adaptive Conflict (EAC) | Specialization resolves functional conflict | Positive selection for specialization | Ancestral gene was under conflicting selective pressures |

The following diagram illustrates the key steps and outcomes of the primary evolutionary models.

Genomic Patterns and Quantifying Divergence

Empirical genomic studies reveal the extensive role of duplication in evolution. In plants, over 50% of genes arose from segmental or whole-genome duplication [16]. In E. coli, 68% of enzymes, 82% of transporters, and 79% of regulatory proteins belong to paralogous groups, illustrating the pervasive nature of this process across life [16].

Detecting and Measuring Evolutionary Forces

The fate of duplicated genes is governed by the interplay of different types of mutations, which can be quantified using molecular evolutionary techniques.

- Synonymous (dS) and Non-synonymous (dN) Substitutions: The ratio ω = dN/dS is a key metric for detecting selection. ω ≈ 1 indicates neutral evolution; ω < 1 suggests purifying selection; and ω > 1 is evidence of positive selection [18] [19].

- Asymmetric Evolution: A common signature of divergence is asymmetric evolution, where one duplicate copy accumulates amino acid changes at a significantly faster rate than the other. A study on teleost fish duplicates found that 50-65% of gene pairs evolved asymmetrically when analyzed with a sensitive Fisher's Exact Test (FET), often with the asymmetry localized to specific protein domains [19]. This is consistent with one copy undergoing neofunctionalization or specializing one subfunction.

Table 2: Molecular Evolutionary Analysis of Duplicated CDPK Genes CPK7 and CPK12 in Grasses

| Analysis Feature | TaCPK7 (Wheat) | TaCPK12 (Wheat) | Evolutionary Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| dN/dS (ω) Ratio | Lower | Higher | Relaxed selective constraints on CPK12 |

| Selection Test (PAML) | Purifying selection | Purifying selection | No positive selection detected |

| Rapidly Evolving Regions | - | N-terminal, EF-hand domains | Structural/functional divergence in calcium-binding domains |

| Expression Response | Drought, salt, cold, H₂O₂ | Abscisic acid (ABA) only | Divergence in stress signaling pathways |

| Proposed Mechanism | Subfunctionalization, not neofunctionalization |

Lineage-Specific Gene Loss and Its Consequences

Not all duplicates are retained. Lineage-specific gene loss is a major evolutionary force that shapes the functional repertoire of genomes. The loss of one paralog can drive functional evolution in the surviving copy, which may compensate by acquiring or maintaining the expression domains of the lost gene [20]. For example, the loss of the aldh1a1 ohnolog in teleost fish is associated with functional changes in the remaining Aldh1a paralogs, allowing the preservation of ancestral developmental programs like retinoic acid signaling in eye development despite the simplification of the gene family [20].

Experimental Methodologies and Research Toolkit

Studying the evolution of new functions requires a combination of computational analyses, directed evolution experiments, and detailed functional characterization.

Computational and Comparative Genomics Protocols

Protocol 1: Phylogenetic and Selection Analysis

- Sequence Acquisition and Alignment: Identify paralogous gene pairs of interest and a suitable outgroup ortholog (e.g., from a closely related non-duplicated species). Perform multiple sequence alignment using tools like MUSCLE or MAFFT.

- Phylogenetic Tree Reconstruction: Construct a gene tree using maximum likelihood (e.g., with RAxML or IQ-TREE) or Bayesian methods (e.g., MrBayes) [21].

- Test for Selection: Use the CodeML module in the PAML package to fit different evolutionary models [18] [19].

- Fit a model where both duplicates evolve under the same ω ratio (null model).

- Fit a model where each duplicate lineage is allowed its own ω ratio (alternative model).

- Use a Likelihood Ratio Test (LRT) to determine if the alternative model fits significantly better, indicating asymmetric evolution.

- Domain-Centric Analysis: Repeat the selection analysis on annotated protein domains separately to identify if asymmetry is localized, which can provide functional insights [19].

Protocol 2: Synteny Analysis to Identify Gene Loss

- Genomic Context Mapping: For the gene family of interest, identify the genomic locations and surrounding genes in multiple species.

- Identify Conserved Syntenic Blocks: Use genomic browsers and tools like MCScanX to find regions in different genomes that originated from a common ancestral chromosomal segment.

- Infer Ohnologs and Losses: In lineages known to have undergone whole-genome duplication (e.g., teleost fishes), identify the expected co-orthologous genomic regions. The absence of an expected paralog in one region, while present in its counterpart, provides evidence for lineage-specific gene loss [20].

Laboratory-Based Directed Evolution Protocol

This protocol tests the IAD model by mimicking evolution in a controlled laboratory setting [16] [15].

- Innovation (Starting Point): Begin with a bacterial strain expressing a single enzyme that has a weak, promiscuous activity alongside its native function.

- Selection: Grow the bacteria under conditions where both the native and the promiscuous activities are required for fitness (e.g., in a medium where the substrate of the promiscuous activity is essential).

- Amplification and Divergence:

- Amplification Phase: Screen for mutants with improved growth. This often first selects for gene amplification events (e.g., via plasmids) that increase enzyme dosage and thereby the level of the poor promiscuous activity.

- Divergence Phase: Continue serial passaging under selection over many generations. Sequence the amplified gene arrays periodically. Mutations that specifically enhance the efficiency of the new activity will be enriched.

- Stabilization: Eventually, mutations that improve the new function may make some amplified copies redundant. The genome may stabilize with one specialized copy for the original function and another for the new function, with loss of the extra amplified copies [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Resources for Studying Gene Duplication and Divergence

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| PAML (Phylogenetic Analysis by Maximum Likelihood) | Software package for molecular evolution analysis, including CodeML for detecting selection. | Calculating dN/dS ratios and testing for positive selection in paralogous lineages [18] [19]. |

| Model Organism Genomes (Zebrafish, Medaka, Yeast) | Provides comparative genomic data from species with known duplication histories (e.g., teleost-specific WGD). | Synteny analysis to identify ohnologs and infer gene loss events [20] [19]. |

| ZFIN / Expression Atlases | Databases of spatio-temporal gene expression patterns (e.g., ZFIN for zebrafish). | Correlating sequence divergence with expression divergence in duplicates [19]. |

| Directed Evolution Setup (Chemostats, Selective Media) | Laboratory apparatus for applying controlled selective pressure to microbial populations. | Experimentally testing the IAD model by selecting for improved promiscuous enzyme activities [16]. |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kits | Introducing specific mutations into gene sequences. | Functionally validating the effect of candidate residues identified in fast-evolving domains of a duplicate gene. |

Gene duplication, followed by divergent evolution through mechanisms like neofunctionalization, subfunctionalization, and the IAD pathway, is a primary engine for generating genetic novelty. The interplay of mutation, selection, and genetic drift on duplicated genes leads to the functional diversification of enzymes, regulators, and entire metabolic pathways. This molecular innovation provides the substrate for ecological adaptation, allowing organisms to explore new niches, develop new traits, and respond to environmental challenges. For researchers in drug development, understanding these principles is critical. Gene families expanded by duplication, such as cytochrome P450 enzymes or various transporter families, are often central to drug metabolism and resistance. Analyzing their evolutionary history can inform predictions of drug cross-reactivity, patient-specific metabolism, and the potential for the evolution of resistance mechanisms. Continued research integrating comparative genomics, molecular evolution, and experimental genetics will further illuminate how new genes are forged from old, deepening our understanding of life's diversity and our ability to intervene in biological processes.

Mitochondrial-Nuclear Co-evolution and Its Impact on Hybrid Fitness

Mitochondrial-nuclear (mitonuclear) co-evolution represents a fundamental evolutionary process driven by the obligate functional interactions between nuclear-encoded proteins and their mitochondrial-encoded counterparts within the oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) system. This co-evolution maintains cellular bioenergetic efficiency but creates potential for hybrid incompatibility when previously co-adapted genomes are separated through hybridization. This review synthesizes current understanding of the molecular mechanisms, evolutionary consequences, and experimental evidence for mitonuclear co-evolution, highlighting its significance as a speciation mechanism and its implications for evolutionary ecology research. We present comprehensive quantitative data from diverse taxonomic groups, detailed experimental methodologies for studying mitonuclear interactions, and essential research tools that enable this growing field of investigation.

The eukaryotic cell is a chimeric entity whose energy metabolism depends on the functional integration of two distinct genomes: the nuclear genome and the mitochondrial genome. This interdependence necessitates precise coordination, as the mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation system requires the direct interaction of protein subunits encoded by both genomes. In most animals, 13 mitochondrial-encoded proteins must properly assemble with approximately 80 nuclear-encoded subunits to form functional OXPHOS complexes [22]. This intimate biochemical relationship creates selective pressure for co-adapted allelic combinations that optimize energy production while minimizing cellular stress.

Mitonuclear co-evolution occurs through two primary, non-mutually exclusive mechanisms: compensatory coevolution, where deleterious mutations in one genome are offset by changes in the other, and adaptive coevolution, where both genomes accumulate changes that enhance fitness under specific environmental conditions [23] [24]. The mitochondrial genome's higher mutation rate (10-100 times greater than nuclear DNA) creates constant selective pressure on nuclear genes to maintain compatibility with evolving mitochondrial sequences [25]. This dynamic interaction has profound implications for hybrid fitness, as crosses between divergent populations can disrupt co-adapted mitonuclear complexes, leading to reduced respiratory function, decreased ATP production, and increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation.

Molecular Mechanisms of Mitonuclear Co-evolution

OXPHOS Complex Assembly and Function

The structural basis of mitonuclear co-evolution lies in the physical interactions between nuclear and mitochondrial-encoded subunits within the OXPHOS complexes. Complex I (NADH dehydrogenase) provides a particularly illustrative example, as it contains seven mitochondrial-encoded subunits (ND1-6, ND4L) that form the core proton-pumping module, which must precisely interface with numerous nuclear-encoded subunits in the electron transfer arm [26] [22]. The assembly of these complexes requires coordinated expression, import, and assembly of subunits from both genetic compartments, with incompatibilities potentially disrupting proton gradient formation and reducing ATP synthesis efficiency.

Recent atomic-resolution structures of OXPHOS complexes have revealed that positively selected amino acid changes often cluster at protein-protein interfaces between mitochondrial and nuclear subunits, suggesting these interfaces are hotspots for co-evolutionary adaptation [22]. For example, in the cytochrome c oxidase complex (Complex IV), adaptive variation frequently occurs at interfaces between mitochondrial and nuclear-encoded subunits, reflecting selective pressure to maintain proper assembly and function despite sequence divergence [26].

Molecular Pathways to Hybrid Incompatibility

Table 1: Molecular Mechanisms of Mitonuclear Hybrid Incompatibility

| Mechanism | Molecular Basis | Consequence | Example Organism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Mismatch | Improper folding/assembly of OXPHOS complexes | Reduced respiratory capacity, decreased ATP production | Marine copepods (Tigriopus) [22] |

| Regulatory Disruption | Impaired mitochondrial protein import or translation | Disrupted mitochondrial biogenesis, proteostatic stress | Yeast (Saccharomyces) [27] [28] |

| Pentatricopeptide Repeat (PPR) Protein Mismatch | Reduced binding affinity to mitochondrial RNAs | Defective mitochondrial translation, respiratory defects | Yeast (Saccharomyces) [27] |

| ROS Signaling Disruption | Altered reactive oxygen species signaling | Impaired cellular signaling, oxidative damage | Fruit flies (Drosophila) [22] |

Signatures of Selection on Mitochondrial and Nuclear Genomes

Genomic analyses across diverse taxa reveal consistent patterns of positive selection on both mitochondrial and nuclear genes involved in OXPHOS. In mammals, mitochondrial proteins involved in proton pumping (particularly ND2, ND4, and ND5) show elevated signals of adaptive evolution, especially in species with specialized metabolic requirements such as diving marine mammals, high-altitude inhabitants, and species with extreme body sizes [26]. These adaptive changes frequently occur in loop regions of transmembrane proteins that likely function as proton pumps, directly affecting the efficiency of energy conversion.

The nuclear compensatory hypothesis suggests that deleterious mitochondrial mutations drive selection for restorative nuclear mutations. Recent evidence from human populations supports this model, showing that nuclear genes with signatures of mitonuclear disequilibrium are enriched for functions related to neurological processes and mitochondrial import signals [24]. This suggests that mitonuclear co-evolution may be particularly relevant for energy-intensive tissues and specialized physiological adaptations.

Quantitative Evidence for Mitonuclear Co-evolution

Phylogenetic Discordance Between Mitochondrial and Nuclear Genomes

Comparative analyses across vertebrate clades reveal widespread discordance between mitochondrial and nuclear phylogenetic trees, with 30-70% of nodes showing conflicting relationships depending on the taxonomic group [29]. This discordance is not uniformly distributed across the tree; conflicts resolved in favor of nuclear DNA tend to occur at deeper nodes, while mitochondrial-inferred relationships often dominate at shallower nodes. Surprisingly, mitochondrial data does not necessarily dominate combined phylogenetic analyses despite often having larger numbers of variable characters, suggesting that nuclear data can provide stronger phylogenetic signal when substantial mitonuclear discordance exists [29].

Table 2: Patterns of Mitonuclear Discordance Across Vertebrate Clades

| Taxonomic Group | Percentage of Discordant Nodes | Conflict Resolution in Combined Analysis | Strongly Supported Conflicts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plethodon salamanders | 30-70% | Typically resolved in favor of mtDNA | Unusually high number |

| Other vertebrate clades | 30-70% | Often resolved in favor of nucDNA | Generally weakly supported |

| Deep phylogenetic nodes | Variable | Preferentially resolved with nucDNA | Less frequent |

| Shallow phylogenetic nodes | Variable | Preferentially resolved with mtDNA | More frequent |

Fitness Consequences of Mitonuclear Mismatches

Experimental studies systematically exchanging mitochondrial DNAs between divergent strains provide direct evidence for the fitness consequences of mitonuclear mismatches. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, creation of 225 unique mitonuclear genotypes through mitochondrial replacement revealed that mitonuclear interactions explain 10.8-31.5% of total phenotypic variance in growth phenotypes, with the strongest effects observed in conditions requiring mitochondrial respiration [28]. Environmental stress, particularly temperature extremes, amplified these effects, demonstrating the context-dependent nature of mitonuclear compatibility.

Strikingly, strains with their original, co-evolved mitonuclear combinations generally outperformed synthetic combinations when grown in media resembling their original isolation habitats, providing direct evidence for local adaptation of mitonuclear genotypes [28]. This pattern held true regardless of whether the mitochondrial exchanges occurred between closely or distantly related strains, suggesting that mitonuclear co-adaptation can occur relatively rapidly during population divergence.

Diagram: Molecular pathways from mitonuclear mismatch to hybrid fitness consequences. Disruption of co-adapted mitochondrial and nuclear gene combinations in hybrids leads to functional defects in oxidative phosphorylation system, ultimately reducing fitness and promoting reproductive isolation.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Model Systems for Mitonuclear Research

Several model systems have been developed to experimentally investigate mitonuclear interactions, each offering distinct advantages for different research questions. Yeast systems, particularly Saccharomyces cerevisiae, provide powerful platforms due to their ease of genetic manipulation, ability to survive without mitochondrial DNA, and capacity for high-throughput phenotypic screening [28]. The development of conplastic mouse strains (animals with identical nuclear genomes but different mitochondrial haplotypes) enables researchers to isolate the specific contributions of mitochondrial variation to complex phenotypes [25]. Similar approaches have been developed in other model organisms, including Drosophila, nematodes, and cell culture systems.

Mitochondrial Replacement Protocols

The core experimental approach for studying mitonuclear interactions involves replacing mitochondrial genomes between divergent strains or populations while controlling for nuclear genetic background. The following protocol, adapted from systematic studies in yeast [28], provides a robust methodology for creating defined mitonuclear combinations:

Protocol: Systematic Mitochondrial DNA Replacement in Yeast

Strain Selection and Validation: Select parental strains representing divergent populations or species. Verify mitochondrial and nuclear genomic sequences to identify polymorphic sites. For Saccharomyces cerevisiae, 15 isolates from diverse ecological niches provided substantial mitochondrial sequence diversity (nucleotide diversity = 0.01) [28].

mtDNA Transfer: Cross haploid strains using standard mating techniques. For yeast, take advantage of biparental mitochondrial inheritance followed by rapid fixation of a single mitotype in progeny. Select for recombinant clones containing the desired nuclear background but alternative mitochondrial genomes.

Genotype Verification: Confirm mitochondrial genome sequences through whole mitochondrial genome sequencing. Verify nuclear background using nuclear genetic markers. Exclude strains with unexpected recombination events.

Phenotypic Screening: Assess fitness of both original and synthetic mitonuclear genotypes across multiple environmental conditions. Key parameters include:

- Growth in media requiring mitochondrial respiration (e.g., ethanol/glycerol as carbon source)

- Temperature stress conditions (e.g., 20°C, 30°C, 37°C)

- Media resembling natural isolation habitats

- Quantitative growth measurements (colony size, growth rate)

Statistical Analysis: Employ ANOVA models with mitochondrial genotype, nuclear genotype, and their interaction as factors: yij = μ ~ mti + nj + (mt × n)ij + εij. Calculate proportion of phenotypic variance explained by mitonuclear interaction terms.

Detection of Mitonuclear Epistasis in Natural Populations

For non-model organisms and natural populations, alternative approaches detect signatures of mitonuclear co-evolution:

Genome-Wide Association of Mitochondrial and Nuclear Variation

- Sequence mitochondrial and nuclear genomes from multiple individuals across populations

- Identify mitochondrial and nuclear SNPs with adequate frequency

- Test for non-random associations (mitonuclear disequilibrium) using statistics such as Goodman-Kruskal's tau

- Control for population structure through simulations and null model comparisons

- Identify nuclear genes with significant mitonuclear associations and test for functional enrichment [24]

Analysis of Somatic Mutation Patterns

- Use ultrasensitive sequencing (e.g., duplex sequencing) to detect low-frequency somatic mutations

- Compare mutation spectra and frequencies across tissues and ages

- Identify signatures of selection in protein-coding regions (e.g., excess of non-synonymous mutations)

- Test for enrichment of mutations that restore mitonuclear ancestral alignment [25]

Diagram: Experimental workflow for systematic analysis of mitonuclear interactions. The approach involves creating defined mitochondrial-nuclear combinations followed by comprehensive phenotyping to identify epistatic interactions.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Methods for Mitonuclear Studies

| Resource/Method | Function/Application | Key Features | Example Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conplastic Strains | Isolate mitochondrial genetic effects | Identical nuclear genome with divergent mtDNA | Mouse strains with different mt-haplotypes on C57BL/6J background [25] |

| Cytoplasmic Hybrid (Cybrid) Cells | Study mitonuclear interactions in cellular context | Fused cells containing nuclear and mitochondrial components from different sources | Human cell lines with matched/discordant mitonuclear backgrounds [30] |

| Duplex Sequencing | Detect ultra-rare somatic mutations | Error-corrected sequencing with very low false-positive rates | Identification of mitochondrial somatic mutations during ageing [25] |

| Mitochondrial Replacement Protocols | Create defined mitonuclear combinations | Systematic exchange of mtDNA between strains | 225 unique yeast mitonuclear genotypes [28] |

| OXPHOS Activity Assays | Measure mitochondrial function | Direct assessment of respiratory complex performance | Functional validation of mitonuclear incompatibilities [22] |

| Goodman-Kruskal's Tau | Quantify mitonuclear disequilibrium | Measures predictive power between mitochondrial and nuclear genotypes | Genome-wide detection of MTD in human populations [24] |

Mitonuclear co-evolution represents a fundamental evolutionary process with far-reaching implications for speciation, hybrid fitness, and adaptive evolution. The accumulating evidence from diverse taxonomic groups demonstrates that incompatibilities between co-adapted mitochondrial and nuclear genomes can contribute significantly to reproductive isolation and reduced hybrid fitness. The molecular dissection of these interactions has revealed specific protein complexes, particularly within the oxidative phosphorylation system, as hotspots for co-evolutionary dynamics.

Future research in this field will likely focus on several key areas: (1) understanding how mitonuclear interactions influence complex diseases and aging processes in humans, (2) elucidating the role of mitonuclear co-evolution in climate adaptation and conservation biology, and (3) developing more sophisticated experimental models that capture the complexity of mitonuclear interactions across different tissues and environmental contexts. The continued development of genomic technologies, particularly those enabling precise manipulation of mitochondrial genomes and high-resolution analysis of mitochondrial function, will further accelerate discovery in this integrative field of evolutionary ecology.

Epigenetic Regulation in Ecological Adaptation and Phenotypic Plasticity

Epigenetics, the study of heritable changes in gene function that do not involve alterations to the underlying DNA sequence, represents a crucial mechanistic link between environmental cues and phenotypic expression [31] [32]. In evolutionary ecology, epigenetic regulation provides a molecular basis for understanding how organisms rapidly adapt to changing environments and display phenotypic plasticity—the ability of a single genotype to produce multiple phenotypes in response to environmental conditions [33] [31]. The three primary epigenetic mechanisms include DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNA (ncRNA) activity, which collectively regulate gene expression by modulating chromatin accessibility and structure [34].

The integration of epigenetics into ecological and evolutionary theory forms part of the "Extended Synthesis," expanding upon the Modern Synthesis framework by incorporating mechanisms of heredity and variation beyond DNA sequence changes [32]. This paradigm acknowledges that environmentally induced epigenetic variation can provide an important source of phenotypic diversity upon which natural selection may act, particularly over ecological timescales [33] [32]. This technical guide examines the core epigenetic mechanisms driving ecological adaptation, details methodologies for their investigation, and explores implications for evolutionary ecology research.

Core Epigenetic Mechanisms in Ecological Adaptation

DNA Methylation

DNA methylation involves the addition of a methyl group to cytosine bases, primarily at cytosine-phosphate-guanine (CpG) dinucleotides [33] [34]. This modification typically suppresses gene expression when it occurs in promoter regions, while intragenic methylation may have more variable effects [33]. In ecological contexts, DNA methylation patterns dynamically respond to environmental stressors, enabling phenotypic adjustments without genetic changes [31].

Table 1: Ecological Stressors and Associated DNA Methylation Responses in Plants

| Stress Type | Species Example | Methylation Response | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drought | Maize (Zea mays) | Changes in promoter regions of water-conservation genes [31] | Optimized water use efficiency [31] |

| Salinity | Mangroves (Bruguiera gymnorhiza) | Genome-wide hypermethylation targeting transposable elements [31] | Genomic stability maintenance & ionic balance [31] |

| Cold Stress | Cassava (Manihot esculenta) | Tissue-specific decrease in petiole methylation [31] | Altered expression of cold-responsive genes [31] |

| Long-term Drought | Oak (Quercus ilex) | Distinct methylation patterns after prolonged exposure [31] | Enhanced drought tolerance [31] |

Methylated cytosines are prone to spontaneous deamination into thymine, potentially leading to permanent genetic mutations over evolutionary time [33]. This positions DNA methylation not only as a regulator of phenotypic plasticity but also as a potential mutagenic force in evolutionary adaptation [33].

Histone Modifications

Histone modifications constitute another critical epigenetic mechanism involving post-translational chemical alterations to histone proteins, including acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination [34]. These modifications influence chromatin structure by changing how tightly DNA is packaged, thereby regulating gene accessibility to transcriptional machinery [34].

- Histone acetylation: Typically associated with transcriptional activation by neutralizing positive charges on histones, reducing DNA-histone affinity [34]

- Histone methylation: Exhibits context-dependent effects; H3K4me3 often marks active genes, while H3K9me3 typically denotes repressed chromatin [34]

- Environmental integration: Histone modification patterns serve as molecular interfaces translating environmental signals into gene expression changes [31]

Non-Coding RNAs

Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), including microRNAs (miRNAs), small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), regulate gene expression at transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels [34]. These molecules can guide epigenetic complexes to specific genomic loci, participate in RNA interference pathways, and modulate chromatin architecture [34]. In tropical and subtropical plants, ncRNAs fine-tune stress response efficiency, balancing growth and defense investments under challenging conditions [31].

Epigenetic Regulation Pathway: This diagram illustrates how environmental stimuli are transduced into phenotypic changes through epigenetic mechanisms.

Methodological Approaches in Ecological Epigenetics

DNA Methylation Analysis

Contemporary DNA methylation analysis techniques range from bisulfite conversion-based methods to enzyme-sensitive approaches and emerging third-generation sequencing technologies [34].

Bisulfite Sequencing Methods rely on the principle that bisulfite treatment converts cytosine to uracil, while 5-methylcytosine (5mC) remains unaffected [34]. This chemical modification enables the mapping of methylated positions across the genome:

- Whole Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS): Provides single-base resolution methylation maps of the entire genome [35] [34]

- Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS): Offers a cost-effective alternative by targeting CpG-rich regions [35] [34]

- Enzymatic Methyl-seq (EM-seq): A newer enzymatic approach that avoids DNA degradation associated with bisulfite treatment [35]

Microarray-Based Platforms like the Illumina Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip array Interrogate over 850,000 CpG sites, providing a balanced approach between coverage and throughput for population-level studies in ecological epigenetics [35] [36].

Third-Generation Sequencing technologies from PacBio and Oxford Nanopore enable direct detection of base modifications without bisulfite conversion, offering long-read capabilities that can haplotype methylation patterns [34].

Table 2: DNA Methylation Analysis Techniques and Applications

| Method | Resolution | Throughput | Key Applications in Ecology |

|---|---|---|---|

| WGBS | Single-base | High | Reference methylomes, species with unknown genomes [34] |

| RRBS/EM-seq | CpG-rich regions | Medium | Population epigenomics, screening multiple individuals [35] |

| MethylationEPIC Array | Pre-defined sites | Very High | Large population studies, ecological gradients [35] [36] |

| Oxidative Bisulfite Sequencing | 5mC vs 5hmC | Medium | Distinguishing methylation states, developmental studies [34] |

| Nanopore Sequencing | Single-base with long reads | Variable | Methylation haplotype, structural variation correlation [34] |

Histone Modification Analysis

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) represents the cornerstone technique for investigating histone modifications and protein-DNA interactions [34]. The method utilizes specific antibodies to enrich chromatin fragments bearing particular histone marks:

Traditional ChIP-seq involves cross-linking proteins to DNA, chromatin fragmentation, antibody-based immunoprecipitation, and high-throughput sequencing of bound DNA fragments [34]. Quality control metrics are critical, including metrics like FRiP (Fraction of Reads in Peaks) scores, which should ideally be ≥0.1 for high-quality data [36].

ChIPmentation integrates tagmentation (simultaneous fragmentation and adapter tagging) using Tn5 transposase into the ChIP workflow, streamlining library preparation [36]. This method requires ≥60% uniquely mapped reads for passable quality [36].

Mint-ChIP-seq enables multiplexed indexing T7-based ChIP sequencing, particularly valuable when working with limited biological material, such as samples from rare or endangered species [36]. This method requires a minimum of 2M uniquely mapped reads for adequate data quality [36].

Chromatin Accessibility Assessment

Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin using sequencing (ATAC-seq) identifies genomically regions with nucleosome-free or loosely packaged chromatin, indicating regulatory activity [36]. The technique utilizes a hyperactive Tn5 transposase to insert adapters into accessible chromatin regions:

- Library Preparation: Transposition reaction simultaneously fragments and tags accessible DNA

- Sequencing: High-throughput sequencing reveals open chromatin regions

- Quality Metrics: TSS (Transcription Start Site) enrichment scores ≥6 indicate high-quality data, while scores <4 suggest poor sample preparation or quality [36]

Single-cell ATAC-seq (scATAC-seq) extends this approach to resolve chromatin accessibility heterogeneity within cell populations from ecological samples [36].

Non-Coding RNA Analysis

RNA sequencing technologies facilitate comprehensive profiling of ncRNA populations:

- Small RNA-seq: Specifically captures miRNAs, siRNAs, and piRNAs through size selection protocols [35]

- Long RNA-seq: Enriches for lncRNAs through ribosomal RNA depletion and polyA selection strategies [35]

- Single-cell RNA-seq: Resolves cell-type-specific ncRNA expression patterns in heterogeneous tissues [36]

Experimental Workflow: This diagram outlines the comprehensive workflow from sample collection to ecological interpretation in epigenetic studies.

Bioinformatic Analysis and Quality Control

Data Processing Pipelines

Robust bioinformatic pipelines are essential for transforming raw sequencing data into biologically meaningful epigenetic information:

DNA Methylation Analysis:

- DMRichR: An R package for statistical analysis and visualization of differentially methylated regions (DMRs) from CpG count matrices [35]

- methylKit: A Bioconductor package focused on single CpG statistics from high-throughput bisulfite sequencing data [35]

- RnBeads: Comprehensive analysis suite for DNA methylation data from both bisulfite sequencing and array platforms [35]

Histone Modification & Chromatin Analysis:

- MACS2: Model-based Analysis of ChIP-Seq for peak calling [35]

- nf-core/chipseq: A robust, community-maintained pipeline for ChIP-seq data analysis [35]

- deepTools: Suite for exploratory analysis and visualization of chromatin data [35]

ncRNA Analysis:

- STAR: Spliced-aware aligner for RNA-seq data [35]

- DESeq2 and edgeR: Bioconductor packages for differential expression analysis [35]

- DIANA Tools and miRWalk: miRNA target prediction algorithms [35]

Critical Quality Control Metrics

Rigorous quality control is paramount for ensuring reliable epigenetic data, particularly with challenging ecological samples [36]:

Table 3: Quality Control Thresholds for Epigenetic Assays

| Assay | Key QC Metric | Threshold (Pass) | Threshold (High Quality) | Mitigation for Failed QC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATAC-seq | Sequencing Depth | ≥25M reads | ≥40M non-duplicate reads | Increase cell input; repeat library prep [36] |

| ATAC-seq | TSS Enrichment | ≥4 | ≥6 | Pre-treat with DNase; sort viable cells [36] |

| ChIPmentation | Uniquely Mapped | ≥60% | ≥80% | Increase cell numbers [36] |

| MethylationEPIC | Failed Probes | ≤10% | ≤1% | Ensure optimal DNA input [36] |

| MeDIP-seq | CpG Coverage | ≥40% | ≥60% | Optimize antibody incubation [36] |

| RNA-seq | Library Complexity | Varies by protocol | >80% of expected genes | Check RNA integrity; avoid degradation [36] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Ecological Epigenetics

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Methylation Kits | Bisulfite conversion kits (Zymo, Qiagen) | Convert unmethylated cytosines to uracil for methylation detection [34] |

| Methylation Arrays | Illumina Infinium MethylationEPIC | Genome-wide methylation profiling at pre-defined CpG sites [36] |

| Histone Antibodies | H3K4me3, H3K27ac, H3K9me3 | Target-specific histone modifications for ChIP assays [34] |

| Chromatin Assay Kits | ATAC-seq kits (Illumina) | Profile accessible chromatin regions [36] |

| RNA Library Preps | smRNA-seq, lncRNA-seq kits | Profile different classes of non-coding RNAs [35] |

| Cross-linkers | Formaldehyde, DSG | Fix protein-DNA interactions for ChIP assays [34] |

| Tn5 Transposase | Custom-loaded or commercial | Simultaneous fragmentation and tagging for ATAC-seq [36] |

| Methylation Enzymes | M.SssI (CpG methyltransferase) | Positive controls for methylation assays [34] |

| DNA Demethylases | TET enzymes | Tool compounds for functional validation [34] |

Transgenerational Inheritance and Evolutionary Implications

Epigenetic variation provides an evolutionarily and ecologically important source of phenotypic variation among individuals, with potential implications for adaptation [32]. The field distinguishes between:

- Intergenerational inheritance: Epigenetic marks consistent between parent and offspring who were directly exposed to environmental conditions as embryos or germ cells [33]

- Transgenerational inheritance: Epigenetic marks transmitted to offspring never exposed to the inducing environment—the F3 generation in females and F2 in males [33]

Plants generally demonstrate more permissive transgenerational epigenetic inheritance compared to vertebrates, particularly placental mammals [33]. Examples from ecological studies include:

- Drought-induced DNA methylation patterns in tropical plants associated with enhanced drought tolerance in offspring [31]

- Genetically identical dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) plants developing heritable DNA methylation variation in response to stressors [32]

- Invasive Japanese knotweed populations showing significant DNA methylation differences correlated with different habitats [32]

The potential for epigenetic mechanisms to contribute to evolutionary processes includes both direct effects through stable inheritance of epigenetic marks and indirect effects through enhanced phenotypic plasticity that shapes selective environments [32].

Epigenetic regulation provides mechanistic explanations for previously enigmatic ecological phenomena, including rapid adaptation to novel environments, transgenerational plasticity, and fine-tuned phenotypic responses to environmental heterogeneity [33] [31] [32]. The integration of epigenetic mechanisms into evolutionary ecology enriches our understanding of adaptation, moving beyond purely sequence-based genetic models to incorporate additional dimensions of heritable variation [32].

Future research directions in ecological epigenetics include:

- Moving from summarized epigenome analyses to nucleotide-level resolution of epigenetic variation [33]

- Integrating multiple epigenetic modalities (methylation, chromatin, ncRNAs) with genetic and transcriptomic data [33] [34]

- Developing more sophisticated bioinformatic tools specifically designed for non-model organisms [35]

- Exploring the causal relationships between specific epigenetic modifications and fitness outcomes in natural populations [33] [31]

As methodological advances make epigenetic profiling increasingly accessible for non-model organisms, ecological epigenetics promises to fundamentally advance understanding of the molecular basis of adaptation and phenotypic plasticity in natural systems [33] [34].

Translating Evolutionary Principles into Drug Discovery Pipelines

Harnessing Co-evolutionary Principles for Antibiotic and Antifungal Development

The ongoing struggle between hosts and pathogens represents a profound co-evolutionary arms race that has shaped the molecular arsenals of both sides over millennia. This dynamic interplay is particularly evident in the context of antimicrobial compounds, where host defense mechanisms and microbial resistance strategies have evolved in tandem [37]. Understanding these co-evolutionary dynamics provides a crucial framework for addressing the current antimicrobial resistance crisis, which claims an estimated 0.9-1.7 million lives annually—a figure projected to rise to 10 million by 2050 without intervention [38] [39]. The molecular basis of these evolutionary interactions offers untapped potential for drug discovery, particularly as conventional approaches have yielded diminishing returns, with only 8 new antibiotic classes approved since 1970 [40]. By decoding the evolutionary principles that govern host-pathogen interactions and resistance development, researchers can develop more sustainable antimicrobial strategies that anticipate and circumvent resistance mechanisms before they emerge in clinical settings.

Theoretical Foundation: Co-evolutionary Dynamics at the Molecular Level

Host-Pathogen Molecular Arms Races