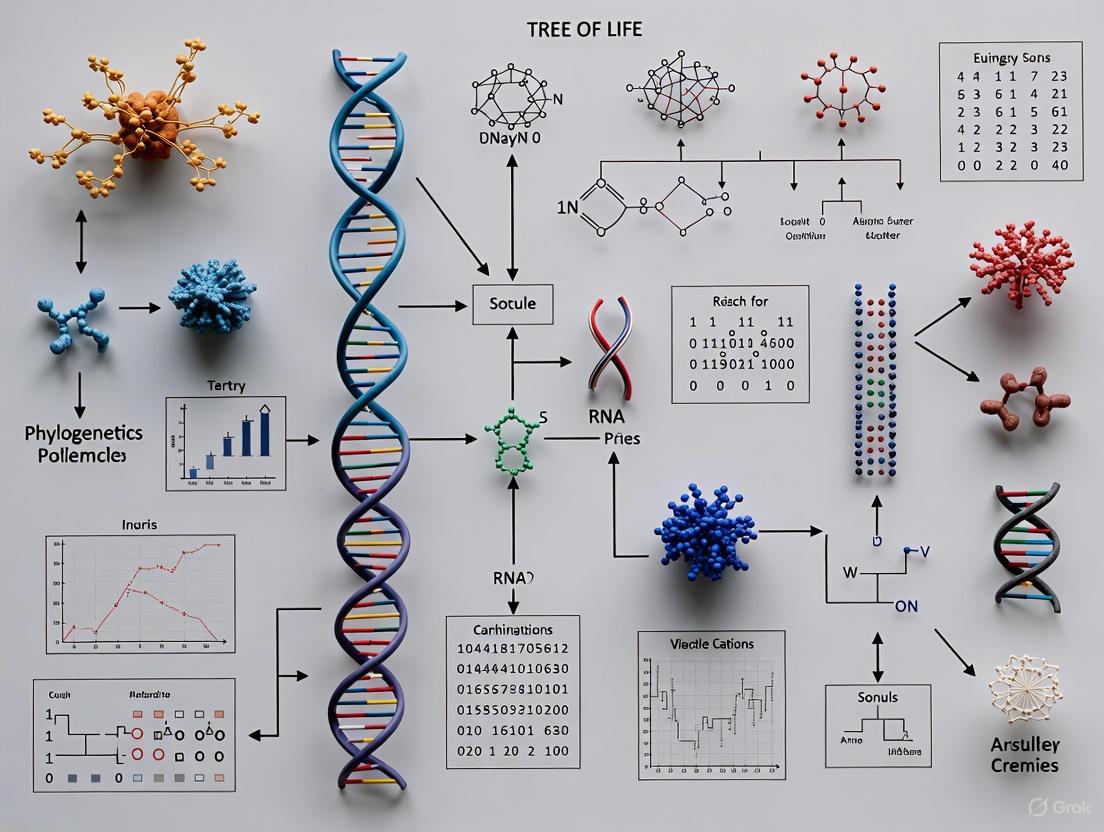

Molecular Phylogenetics and the Tree of Life: From Genomic Data to Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of molecular phylogenetics, a foundational discipline for reconstructing the evolutionary history of life.

Molecular Phylogenetics and the Tree of Life: From Genomic Data to Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of molecular phylogenetics, a foundational discipline for reconstructing the evolutionary history of life. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the core principles and computational tools used to build the Tree of Life. The scope spans from methodological advances in genomic analysis and model selection to practical applications in tracking pathogen evolution, guiding conservation efforts, and accelerating drug discovery. The article also addresses critical challenges in the field, including computational optimization strategies and protocols for validating phylogenetic estimates to ensure accuracy and reliability in biomedical research.

The Foundations of Molecular Phylogenetics: Building the Tree of Life

Phylogenetic trees, often referred to simply as phylogenies, are tree-shaped diagrams that illustrate the evolutionary relationships between species or populations [1]. These trees serve as fundamental knowledge in biology and are crucial for addressing various biological questions, from understanding biodiversity to guiding conservation efforts and even designing vaccines [2]. The tree of life represents the evolutionary history of all living organisms, depicting patterns of divergence from common ancestors over billions of years. Phylogenetic analysis has evolved significantly with advancements in sequencing technologies, reaching a new level of "phylogenomics" that involves numerous genes and sophisticated mathematical models [1]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding phylogenetic trees is essential for comparing biological species, understanding evolutionary pathways of pathogens, and identifying genetic relationships that inform therapeutic target selection.

Fundamental Terminology and Tree Interpretation

Basic Components of Phylogenetic Trees

Understanding phylogenetic trees requires familiarity with their core components and terminology [2]:

- Tips/Leaves: The terminal nodes of the tree representing extant (living) or sampled taxonomic entities such as species, genera, or strains. These are the operational taxonomic units (OTUs) under study.

- Internal Nodes: Points within the tree where branches diverge, representing hypothetical common ancestors of the descendant taxa.

- Branches/Edges: The lines connecting nodes, representing evolutionary lineages and their relationships.

- Root: The most recent common ancestor of all taxa represented in the tree, providing directionality from past to present.

- Clade: A group of taxa consisting of all the descendants of a common ancestor, forming a monophyletic group.

Tree Types and Properties

Phylogenetic trees can be categorized based on their properties and construction [2]:

- Rooted vs. Unrooted: Rooted trees have a defined root node indicating the common ancestor and direction of evolution, while unrooted trees only show relational patterns without evolutionary direction.

- Binary Trees: The most common assumption in phylogenetics, where each internal node branches into exactly two descendants, representing bifurcating speciation events.

- Phylogram vs. Cladogram: Phylograms scale branch lengths to represent the amount of evolutionary change (e.g., genetic distance or time), while cladograms only represent topological relationships without scaled branches.

Figure 1: Phylogenetic tree types and their key characteristics

Methodological Framework for Phylogenetic Inference

Core Workflow for Phylogenetic Analysis

Constructing accurate phylogenetic trees is computationally intensive and involves multiple methodological steps from data collection to tree evaluation [1] [2]. The standard workflow ensures systematic processing of molecular data to generate reliable evolutionary hypotheses.

Figure 2: Phylogenetic analysis workflow with key methodological steps

Key Methodological Approaches

Phylogenetic inference employs several computational approaches with different underlying assumptions and statistical foundations [2]:

Distance-Based Methods: Algorithms such as Neighbor-Joining (NJ) or FastME build trees based on pairwise genetic distances between sequences. These methods are computationally efficient but may lose information by reducing sequence data to distance matrices.

Character-Based Methods:

- Maximum Parsimony: Seeks the tree that requires the fewest evolutionary changes to explain the observed sequences. This method works well for closely related sequences but can be misled by homoplasy.

- Maximum Likelihood (ML): Finds the tree topology and branch lengths that maximize the probability of observing the sequence data under a specific evolutionary model. ML methods are statistically rigorous and widely used in phylogenomics.

- Bayesian Inference: Estimates posterior probabilities of tree hypotheses using Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithms, incorporating prior knowledge and providing natural measures of uncertainty.

Evolutionary Assumptions in Phylogenetic Analysis

Most phylogenetic methods operate under a set of common evolutionary assumptions [2]:

- Markovian Evolution: The evolutionary process is "memoryless," meaning future changes are not affected by past evolutionary history, allowing application of Markov process mathematics.

- Tree-Like Evolution: Phylogenetic relationships can be accurately represented by a tree structure, though this assumption is challenged by processes like hybridization and lateral gene transfer.

- Molecular Clock: Sequences in a clade evolve at approximately the same rate, enabling the dating of evolutionary events, though rate variation among lineages is common.

- Independence of Lineages: Once species have diverged, they evolve independently, though biological lineages do interact in reality.

Phylogenetic Data Repositories

The field of phylogenetics has seen significant advancements in data availability and computational resources. Recent initiatives have addressed previous limitations in phylogenetic data access and coverage.

Table 1: Major Phylogenetic Data Resources and Their Features

| Resource | Data Content | Update Status | Access Method | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TreeHub | 135,502 phylogenetic trees from 7,879 research articles across 609 journals [1] | Current (up to January 2025) [1] | API access, web interface [1] | Automated extraction from papers, taxonomic assignment, integration with public databases [1] |

| TreeBASE | Phylogenetic trees and associated data | Updated to 2019 [1] | Web interface, database queries | Traditional repository relying on researcher submissions [1] |

| Dryad | Scientific research data including phylogenetic trees | Continuous updates [1] | API with access token [1] | CC0 license, links to publication DOIs [1] |

| FigShare | Diverse research outputs including phylogenetic data | Continuous updates [1] | Search and Download API [1] | CC0 or CC-BY licenses [1] |

Tree Visualization and Annotation Platforms

Effective visualization is crucial for interpreting and communicating phylogenetic relationships. Several specialized tools have been developed for this purpose.

Table 2: Phylogenetic Tree Visualization Software and Capabilities

| Software | Primary Function | Annotation Capabilities | Programmability | Output Formats |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ggtree | R package for tree visualization and annotation [3] [4] | Multiple annotation layers, complex data integration [3] [4] | High (R programming language) [3] [4] | Publication-quality vector and raster graphics |

| FigTree | Desktop tree visualization | Basic annotation | Limited GUI-based | Multiple image formats |

| iTOL | Web-based tree display | Interactive annotation | Web interface, API support | PNG, SVG, PDF |

| Dendroscope | Desktop program for large trees | Network visualization, basic annotation | Limited GUI-based | Various image formats |

| EvolView | Web-based tree visualization | Customizable annotation | Web interface | Publication-ready figures |

The ggtree R package deserves special attention for its comprehensive approach to tree visualization. As an extension of the ggplot2 graphing system, ggtree supports multiple tree layouts including rectangular, slanted, circular, fan, and unrooted (using equal-angle or daylight algorithms) [3] [4]. It enables researchers to construct complex tree figures by combining multiple annotation layers using the + operator, similar to standard ggplot2 syntax [3].

Advanced Analytical Techniques in Molecular Phylogenetics

Phylogenomic Approaches

Phylogenomics represents the integration of genomic-scale data into phylogenetic analysis, significantly enhancing resolution and statistical support for evolutionary relationships [1]. This approach leverages entire genomes or large sets of genes to reconstruct evolutionary history, addressing limitations of single-gene analyses. Phylogenomic methods are particularly valuable for resolving rapid radiations and deep evolutionary relationships where individual genes provide conflicting signals due to incomplete lineage sorting or other evolutionary processes.

Tree Evaluation and Uncertainty Assessment

Assessing the reliability of phylogenetic trees is essential for drawing valid biological conclusions. Several statistical approaches are employed:

- Bootstrapping: A resampling technique that evaluates the support for tree nodes by repeatedly sampling sites from the alignment with replacement and building trees from each resampled dataset. Bootstrap values above 70-80% are generally considered indicative of robust support.

- Posterior Probabilities: In Bayesian inference, these values represent the proportion of MCMC samples that contain a particular clade, providing a direct measure of clade credibility.

- Likelihood-Based Tests: Statistical tests such as the Shimodaira-Hasegawa test or the Approximately Unbiased test that compare alternative tree topologies.

Gene Tree-Species Tree Reconciliation

A critical challenge in molecular phylogenetics is the gene tree-species tree reconciliation problem, where gene trees may differ from the true species phylogeny due to biological processes such as lateral gene transfer, gene duplication, gene loss, and incomplete lineage sorting [2]. Sophisticated algorithms have been developed to reconcile these conflicts and infer the underlying species tree from multiple gene trees.

Research Reagents and Computational Toolkit

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Phylogenetic Analysis

| Item | Function/Application | Examples/Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence Data | Raw molecular data for phylogenetic inference | NCBI GenBank, BOLD, ENA, primary sequencing data |

| Multiple Sequence Alignment Tools | Align homologous sequences for comparison | MAFFT, Clustal Omega, MUSCLE, T-Coffee |

| Evolutionary Models | Mathematical models of sequence evolution | Jukes-Cantor, Kimura 2-parameter, GTR, codon models |

| Tree Inference Software | Implement algorithms for tree building | RAxML, IQ-TREE, MrBayes, BEAST2, PhyML |

| Tree Visualization Tools | Display and annotate phylogenetic trees | ggtree, FigTree, iTOL, Dendroscope [3] [4] |

| High-Performance Computing | Computational resources for large analyses | Computer clusters, cloud computing, parallel processing |

| Data Repositories | Access to published trees and associated data | TreeHub, TreeBASE, Dryad, FigShare [1] |

Applications in Research and Drug Development

Phylogenetic trees serve critical functions across biological research and pharmaceutical development:

- Vaccine Design: Phylogenetic analyses of rapidly evolving pathogens like SARS-CoV-2 and influenza inform vaccine strain selection by identifying circulating variants and predicting evolutionary trajectories [2].

- Conservation Biology: Measuring phylogenetic diversity guides conservation prioritization by identifying evolutionarily distinct lineages that represent unique branches of the tree of life [2].

- Infectious Disease Dynamics: Understanding the evolutionary origins and spread of emergent human diseases, approximately 70% of which originate from other species [2].

- Drug Target Identification: Identifying evolutionarily conserved regions in pathogen genomes that may represent ideal targets for therapeutic intervention.

- Antimicrobial Resistance: Tracking the evolution and spread of resistance genes through bacterial populations.

Future Directions and Challenges

The field of phylogenetic analysis continues to evolve with several emerging frontiers:

- Integration of Massive Datasets: Handling the computational challenges of phylogenomic analyses with thousands of genomes while incorporating diverse data types.

- Model Development: Creating more realistic evolutionary models that account for heterogeneity in substitution rates, selection pressures, and complex evolutionary processes.

- Visualization Innovation: Developing new methods for visualizing and exploring extremely large phylogenetic trees with rich annotation data [3] [4].

- Cross-Disciplinary Applications: Expanding the use of phylogenetic methods in non-traditional fields including epidemiology, ecology, and comparative genomics.

Phylogenetic trees remain indispensable tools for understanding evolutionary relationships and addressing fundamental biological questions. As Theodosius Dobzhansky famously stated, "Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution" [2]. The continued development of comprehensive datasets like TreeHub, which includes over 135,000 phylogenetic trees from nearly 8,000 research articles, coupled with advanced analytical and visualization tools like ggtree, ensures that phylogenetic analysis will remain a cornerstone of biological research and its applications in drug development and biomedical science [1] [3].

The Molecular Clock Hypothesis stands as a cornerstone of modern molecular phylogenetics, providing a framework for estimating evolutionary timescales. This hypothesis proposes that evolutionary changes at the molecular level accumulate at a relatively constant rate over time, functioning similarly to a ticki-tock clock [5]. For researchers reconstructing the Tree of Life, this concept provides a powerful tool to translate genetic differences between species into estimates of their divergence times, moving beyond mere relationship reconstruction to create a temporal timeline of life's history.

The fundamental principle is that if the mutation rate is known, the genetic divergence between species can be used as a measure of time since their last common ancestor. This methodology has revolutionized our understanding of evolutionary timescales, allowing scientists to date divergence events that leave no fossil evidence and to calibrate phylogenetic trees across the entire spectrum of life.

Theoretical Foundation and Core Principles

The Neutral Theory and the Molecular Clock

The theoretical foundation of the molecular clock is deeply rooted in the Neutral Theory of molecular evolution, introduced by Motoo Kimura [5]. This theory posits that the vast majority of evolutionary changes at the molecular level are neither advantageous nor deleterious, but effectively neutral. These neutral mutations accumulate in populations through genetic drift rather than natural selection.

- Constant Rate Proposition: Under the neutral theory, the rate of molecular evolution is predicted to be relatively constant over time and across lineages because it equals the mutation rate for neutral alleles [5].

- Rate Variation: Despite the "clock-like" name, the molecular clock does not imply a perfectly metronomic rate. Significant variations occur among lineages due to factors like generation time, metabolic rates, and the efficiency of DNA repair mechanisms [6].

Calibration with the Fossil Record

To transform molecular differences into absolute time estimates, the molecular clock must be calibrated using independent geological or paleontological data [5].

Calibration Process:

- Identify a node on a phylogenetic tree with a reliably dated fossil.

- Calculate the genetic distance between descendant species.

- Establish a mutation rate (e.g., if two species diverged 10 million years ago and show 20 mutations, the rate is 2 mutations per million years) [5].

Table 1: Advantages and Limitations of the Molecular Clock Hypothesis

| Aspect | Advantage | Challenge/Limitation |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Basis | Grounded in Neutral Theory; provides testable predictions [5]. | Not all mutations are neutral; selection pressures vary [5]. |

| Application Scope | Applicable across all life forms with genetic material [5]. | Rate heterogeneity among lineages can lead to inaccuracies [6]. |

| Calibration | Allows integration of genetic and fossil evidence [5]. | Fossil record is incomplete; dating uncertainties affect calibration [5]. |

| Data Requirements | Genome-scale data increases statistical power and resolution [7]. | Computational complexity; requires handling massive datasets [7]. |

Methodological Approaches and Workflows

Constructing Cladograms with Molecular Data

Cladograms are branching diagrams that illustrate evolutionary relationships, and molecular data provides an objective basis for their construction [5].

Step-by-Step Construction:

- Sequence Gathering: Obtain homologous DNA, RNA, or protein sequences from the organisms of interest.

- Sequence Alignment: Use bioinformatics tools (e.g., MUSCLE, MAFFT) to align sequences and identify comparable sites [5].

- Distance Calculation: Compute a distance matrix by tabulating the number of genetic differences (mutations) between each pair of sequences. The genetic distance (D) is calculated as D = n / N, where 'n' is the number of observed differences and 'N' is the total number of sites compared [5].

- Tree Building: Use the distance matrix to construct the cladogram, typically via algorithms like Neighbor-Joining or Maximum Likelihood. Organisms with fewer genetic differences are placed as closer neighbors on the tree [5].

Whole-Genome Analysis with the PhaME Workflow

For robust, high-resolution phylogenies, whole-genome Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) analysis has become a gold standard. The Phylogenetic and Molecular Evolutionary (PhaME) analysis workflow is a comprehensive tool for this purpose [7].

PhaME Analysis Workflow for Genomic Data

Key Steps in the PhaME Workflow:

- Input Flexibility: PhaME accepts diverse data types, including raw sequencing reads (FASTQ), draft assemblies (contigs), finished genomes, and even metagenomic reads, provided the target organism is sufficiently represented [7].

- Core Genome Identification: The tool identifies the conserved core genome present in all input samples.

- SNP Discovery: It extracts SNPs from the aligned core genome, providing the raw data for phylogenetic analysis.

- Phylogeny and Molecular Evolution: PhaME reconstructs a maximum likelihood phylogeny and can parse SNPs into coding/non-coding regions and synonymous/non-synonymous substitutions to identify genes under selection [7].

This workflow was validated by reconstructing the established phylogeny of Escherichia coli and related genera, correctly grouping 676 genomes into their expected phylotypes and resolving contested evolutionary relationships among environmental cryptic lineages [7].

Calibration and Divergence Time Estimation

Molecular Clock Calibration Process

Critical Analysis and Challenges

While powerful, the molecular clock hypothesis faces several significant challenges that researchers must address to ensure accuracy.

- Rate Heterogeneity: Different genes and lineages evolve at different rates. Genes under strong selective pressure evolve slower, while non-coding regions may evolve faster [5].

- Generation-Time Effect: Species with shorter generation times (e.g., rodents) may accumulate mutations faster per year than those with longer generation times (e.g., primates), potentially leading to overestimates of divergence times [6].

- Homoplasy: The independent appearance of similar traits or genetic sequences in different lineages (due to convergent evolution or reversions) can obscure true evolutionary relationships and lead to incorrect branch length estimates [5].

- Genetic Reversions: A mutation at a specific site may revert to its original state, effectively erasing evidence of a previous mutation. This can lead to an underestimation of the true divergence time [5].

- Horizontal Gene Transfer (HGT): Particularly common in bacteria, HGT involves the direct transfer of genetic material between unrelated organisms. This can confound molecular clock analyses by introducing genes with different evolutionary histories [5].

Statistical Framework and Best Practices

To address these challenges, modern molecular clock analyses employ sophisticated statistical models:

- Relaxed Molecular Clocks: These models allow evolutionary rates to vary among branches according to a specified probability distribution, accommodating real biological variation while maintaining temporal structure.

- Multiple Calibration Points: Using several reliably dated fossils throughout the tree, rather than a single point, increases accuracy and allows for cross-validation.

- Genome-Wide SNPs: Analyzing SNPs across entire genomes minimizes the impact of random sequencing errors and biases from individual genes under strong selection [7].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Clock Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| PhaME Software | Open-source workflow for phylogenetic and molecular evolutionary analysis from various genomic inputs [7]. | Constructing genus and species phylogenies from raw reads, assemblies, or completed genomes. |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Tools for sequence alignment, genetic distance calculation, and phylogenetic tree construction (e.g., MUSCLE, RAxML). | Handling vast genetic datasets; generating distance matrices and branching patterns [5]. |

| Reference Genomes | High-quality, annotated genomes from databases like NCBI RefSeq. | Serving as a reference for SNP calling and assembly in comparative genomics [7]. |

| Fossil Calibration Databases | Curated databases of reliably dated fossils (e.g., Fossil Calibration Database). | Providing independent time constraints for calibrating molecular clocks. |

Applications in Tree of Life Research

Molecular clock analyses have been instrumental in resolving key questions about the evolutionary history of life. The PhaME workflow, for example, has demonstrated robust performance across the microbial tree of life, including bacteria (Escherichia, Burkholderia), microbial eukaryotes (Saccharomyces), and viruses (Zaire ebolavirus) [7].

In one notable application, analysis of 676 Escherichia and related genomes not only recapitulated the established E. coli phylogeny but also provided supporting evidence for the reclassification of certain species and helped resolve evolutionary relationships among contested cryptic clades [7]. This demonstrates how molecular clock methodology, when applied to genome-scale data, can both validate and refine our understanding of the Tree of Life.

By providing estimates for divergence events that are not recorded in the fossil record, the molecular clock hypothesis allows scientists to construct a more comprehensive timeline of life's history, from recent species radiations to deep evolutionary splits that shaped the major domains of life.

The field of molecular phylogenetics, dedicated to reconstructing the evolutionary history of life, has undergone a profound transformation with the advent of genomics. This shift has given rise to phylogenomics, which the scientific literature defines as "the intersection of the fields of evolution and genomics" [8]. This discipline represents a fundamental methodological evolution, moving beyond the analysis of individual gene sequences to leveraging entire genomes or large portions thereof to infer evolutionary relationships [8] [9]. For researchers and scientists engaged in tree of life research, this transition marks a pivotal advancement. Where traditional phylogenetic methods often struggled to resolve deep, ancient evolutionary branches—sometimes presenting a picture of rapid, "big-bang" diversification—phylogenomics provides a powerful new lens [10]. By utilizing hundreds to thousands of genes simultaneously, phylogenomics has brought unprecedented resolution to the eukaryotic tree of life, enabling scientists to test long-standing hypotheses about the relationships between major supergroups and place enigmatic protist lineages with greater confidence [10] [9]. This technical guide explores the journey of phylogenetic data sources, from their single-gene origins to the whole-genome approaches that are now redefining our understanding of life's history.

The Era of Single Genes and Markers

The initial molecular revolution in phylogenetics was propelled by the comparison of sequences from single, conserved genes. The small subunit ribosomal RNA (SSU rRNA) gene emerged as the quintessential molecular marker for this purpose [10]. Its properties made it an ideal tool for early phylogenetic studies: it is ubiquitous across life, relatively easy to amplify and sequence, and contains a mix of rapidly evolving regions suitable for resolving recent divergences and highly conserved regions useful for probing deep evolutionary splits [10]. For years, SSU rRNA phylogenies formed the backbone of our understanding of the eukaryotic tree of life.

These early molecular phylogenies consistently suggested a tree in which a handful of seemingly "primitive," amitochondriate protist lineages (e.g., diplomonads and parabasalids) diverged early, followed by a densely branched "crown" group containing animals, plants, fungi, and other complex eukaryotes [10]. This structure supported the archezoa hypothesis, which postulated that these amitochondriate lineages diverged before the endosymbiotic origin of mitochondria [10]. However, this appealingly simple narrative began to unravel as more data accumulated. It became apparent that the early-diverging position of the archezoan taxa was likely a long-branch attraction (LBA) artefact, caused by the mutational saturation of their fast-evolving sequences, which were erroneously attracted to the distant outgroup [10]. Crucially, mitochondrial-derived genes and reduced mitochondrial organelles were eventually discovered in these lineages, demonstrating that they are not primitively amitochondriate but have instead undergone reductive evolution [10]. This discovery marked the end of the archezoa hypothesis and exposed the limitations of single-gene phylogenies, which are highly susceptible to systematic errors like LBA, particularly when evolutionary rates vary significantly across lineages [10].

The Transition to Genome-Scale Data

The limitations and inconsistencies of single-gene studies, compounded by the incongruence often observed between phylogenies derived from different genes, created a pressing need for a more robust approach. This need, coupled with the technological breakthroughs of next-generation sequencing (NGS), facilitated the transition to phylogenomics [10]. The core premise of phylogenomics is that by analyzing large alignments of tens to hundreds of genes, the phylogenetic signal—the evolutionary history shared across genes—will overwhelm stochastic noise and systematic errors that plague single-gene analyses [10] [9].

This shift to genome-scale data has transformed the strategies for resolving evolutionary relationships. Where traditional methods were effective for closely related organisms, phylogenomics provides the power to tackle deeper, more contentious relationships among distantly related taxa and microorganisms [8]. By using entire genomes, the anomalies created by factors such as lateral gene transfer, convergent evolution, and varying evolutionary rates for different genes are overwhelmed by the dominant pattern of evolution indicated by the majority of the data [8]. This approach has led to significant revisions of the tree of life, including the resolution of ancient relationships between eukaryotic supergroups and a new understanding of the evolutionary trajectory of major clades [10]. The following workflow illustrates the typical transition from a single-gene to a phylogenomic analysis, highlighting the key steps of data acquisition, matrix construction, and phylogenetic inference that are detailed in the subsequent sections.

Modern Phylogenomic Data Types and Methodologies

Modern phylogenomics leverages a diverse array of genomic data sources, each with specific strengths and applications. The two primary analytical frameworks for handling these data are the supermatrix (or concatenation) approach and the supertree approach [9].

Data Types in Phylogenomics

Table: Comparison of Major Phylogenomic Data Types

| Data Type | Description | Key Applications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Sequences (Nucleotide/Amino Acid) | Concatenated alignments of orthologous genes from multiple protein-coding genes. | The most common phylogenomic data type; used in supermatrix analyses to resolve deep and shallow evolutionary relationships [10] [9]. | Requires careful identification of orthologs; model misspecification can lead to inconsistency. |

| Rare Genomic Changes (RGCs) | Includes indels, retrotransposon insertions, gene order changes, and gene duplications/losses. | Provides complementary, discrete phylogenetic characters that are less prone to homoplasy [9]. | Often limited in number; can be difficult to identify and characterize unambiguously. |

| Whole-Genome Features | Properties derived from entire genomes, such as genomic composition or codon usage. | Used for deep phylogenetic splits and in cases where sequence alignment is difficult [9]. | Requires sophisticated modeling; the phylogenetic signal can be complex to interpret. |

Core Methodologies: Supermatrix vs. Supertree

The supermatrix approach is the best-characterized phylogenomic method [9]. It involves concatenating multiple aligned gene sequences into a single, large alignment, which is then used to infer a phylogenetic tree [8] [9]. Its power relies on the increased resolving power provided by a vast number of sequence positions, which reduces sampling error (the error that occurs due to limited data) [9]. For example, a study resolving photosynthetic eukaryotes used a supermatrix of 135 genes from 65 species [8]. A significant finding is that the supermatrix approach can be surprisingly robust to large amounts of missing data, allowing for the inclusion of taxa with incomplete genomic data [9].

The supertree approach, in contrast, involves inferring individual trees from separate genes or data partitions and then combining these source trees into a single comprehensive phylogeny [8] [9]. This method is useful for integrating datasets from diverse studies and can be more computationally tractable for extremely large datasets. A study to determine the root of the bacterial tree of life, for instance, used a supertree approach to analyze 11,272 gene families [8].

A critical challenge in phylogenomics is model misspecification, which can lead to statistical inconsistency—where analyses converge on an incorrect tree as more data are added [9]. This often arises from simplistic models of sequence evolution that fail to account for the true complexity of molecular evolution, such as site-heterogeneous selection and variation in evolutionary rates across sites and lineages. Mitigating this requires the development of more sophisticated models, critical evaluation of data properties, and the use of only the most reliable characters [9].

Experimental Protocols in Phylogenomics

Executing a robust phylogenomic study requires a meticulous, multi-stage workflow. The following protocol outlines the key steps for a standard supermatrix-based analysis, which represents a foundational methodology in the field.

Step-by-Step Workflow: Supermatrix Construction and Analysis

- Taxon and Gene Sampling: Select the target species (taxa) based on the evolutionary question. In parallel, identify a set of orthologous genes for analysis. The selection of genes is critical and often focuses on single-copy orthologs present across the taxa of interest. Genome-scale data allows for the use of hundreds to thousands of genes, which overwhelms the stochastic noise and minor incongruences present in individual gene histories [8] [9].

- Sequence Alignment and Curation: For each selected gene, obtain the corresponding protein or nucleotide sequences and perform a multiple sequence alignment. Alignments must be carefully curated to remove poorly aligned regions or sequences, as alignment errors are a major source of systematic bias. This step is often automated but may require manual refinement.

- Data Concatenation (Supermatrix Construction): Concatenate the individual gene alignments into a single, large supermatrix. The structure of this matrix—where each taxon has data for some genes but may have missing data for others—is a key feature. Studies have shown that the supermatrix approach can be robust to a surprisingly high amount of missing data [9].

- Phylogenetic Inference: Analyze the supermatrix using standard tree-building methods, now applied to a genomic scale.

- Maximum Likelihood (ML): This method involves finding the phylogenetic tree and model parameters that maximize the probability of observing the given sequence data [11]. It is a widely used and powerful approach for phylogenomic inference.

- Bayesian Inference (BI): This method uses Bayesian statistics to approximate the posterior probability distribution of trees [11]. It incorporates prior knowledge and is particularly useful for incorporating uncertainty in model parameters and for providing measures of support (posterior probabilities) for the inferred clades.

- Robustness Assessment: Evaluate the confidence in the inferred tree. This involves:

- Statistical Support: Calculating branch support values using bootstrapping (for ML) or posterior probabilities (for BI).

- Data Interrogation: Testing the robustness of the results to different taxon samples, gene selections, and models of evolution. This helps to identify potential sources of bias and inconsistency [9].

Table: Key Tools and Resources for Phylogenomic Research

| Tool/Resource Category | Examples & Functions |

|---|---|

| Sequencing Technologies | Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) platforms (e.g., Illumina, PacBio, Oxford Nanopore) for generating whole-genome or transcriptome data from diverse taxa [10]. |

| Bioinformatics Software | Alignment Tools: (e.g., MAFFT, MUSCLE) for creating multiple sequence alignments. Phylogenetic Inference: (e.g., RAxML/ExaML, IQ-TREE for ML; MrBayes, PhyloBayes for BI) for building trees from large datasets [11]. Orthology Prediction: (e.g., OrthoFinder, BUSCO) to identify single-copy orthologous genes. |

| Computational Infrastructure | High-Performance Computing (HPC) clusters are often essential for handling the massive computational load of phylogenomic analyses, particularly for Bayesian inference and large ML bootstraps. |

| Public Data Repositories | NCBI GenBank, ENSEMBL, JGI: Sources for genomic and transcriptomic data. Specialized Databases: (e.g., Genome Taxonomy Database) for curated taxonomic information [8]. |

Impact on the Tree of Life and Future Directions

The application of phylogenomics has led to substantial revisions in the tree of life, particularly for eukaryotes. Early morphological classifications that grouped eukaryotes into a few "kingdoms" (e.g., Plants, Animals, Fungi) have been superseded by a supergroup model based largely on molecular data [10]. This framework, which includes major groups like Opisthokonta (animals, fungi), Archaeplastida (plants, red and green algae), SAR (Stramenopiles, Alveolates, Rhizaria), Excavata, and Amoebozoa, recognizes that the bulk of eukaryotic diversity is microbial, with multicellular lineages representing just a few branches [10]. Phylogenomics has been instrumental in testing, refining, and establishing the relationships between these supergroups.

Despite its power, phylogenomics faces ongoing challenges. A significant issue is inconsistency, where highly supported but incorrect trees are inferred due to model violations that are not overcome by simply adding more data [9]. Future progress hinges on developing more realistic models of sequence evolution that better account for the heterogeneity of the evolutionary process [9]. Furthermore, the field is moving towards integrating phylogenomics with other data types and fields. Key future directions include:

- Incorporating Phylogenetic Uncertainty: Using Bayesian or bootstrap methods to account for uncertainty in the tree topology itself when using the tree in downstream comparative analyses [11].

- Integration with Other Data Types: Combining phylogenomic trees with phenotypic, ecological, and genomic data to study trait evolution and adaptation [11].

- Machine Learning Applications: Leveraging new computational techniques to improve the accuracy and efficiency of phylogenomic inference [11].

As these methodologies mature, phylogenomics will continue to be an indispensable tool for resolving life's deepest branches and understanding the processes that have shaped biological diversity.

Modern phylogenetics represents a fundamental discipline within biology, dedicated to reconstructing the evolutionary relationships among species. Its primary aims are the inference of accurate genealogical trees and the establishment of a unified classification system that reflects evolutionary history [12]. The field has evolved from narrative scenarios and morphological comparisons to a computational and data-intensive science, driven by advances in molecular biology and genomics [12] [13]. Phylogenetics now underpins diverse biological research, from understanding the origin of new body plans to tracking pathogen outbreaks and discovering new drugs [12] [14]. The Genomic Era has transformed the scale and precision of phylogenetic inference, enabling scientists to reconstruct the Tree of Life with unprecedented accuracy, thereby bringing Darwin's dream of "fairly true genealogical trees of each great kingdom of Nature" within grasp [15]. This whitepaper details the core aims, methodologies, challenges, and applications of modern phylogenetics, framed within the context of molecular phylogenetics and Tree of Life research.

The Foundational Aims of Phylogenetics

Inferring Accurate Genealogical Relationships

The principal aim of phylogenetic inference is to determine the evolutionary history of species, genes, or genomes through the construction of phylogenetic trees. A phylogenetic tree is a branching diagram where tips represent observed entities (e.g., species or genes), branches represent the passage of genetic information, and nodes represent common ancestors [12] [14]. The accuracy of these trees is paramount, as they form the foundational hypothesis for testing evolutionary questions, including the emergence of new metabolic pathways, morphological character evolution, and demographic changes in recently diverged species [13].

Key Tree Components:

- Branches: Represent evolutionary lineages and the amount of genetic change.

- Nodes: Branching points indicating lineage divergence from a common ancestor.

- Root: The most recent common ancestor of all entities in the tree.

- Clades (Monophyletic Groups): Groups consisting of a single common ancestor and all of its descendants [16].

Establishing a Unified and Monophyletic Classification

A second, equally critical aim is to reform biological classification to align with evolutionary history. Modern systematics seeks to ensure that taxonomic groups are monophyletic, meaning they include an ancestor and all of its descendants [16]. This move towards phylogenetic classification addresses limitations of the traditional Linnaean system, which often created paraphyletic groups (an ancestor but not all descendants, e.g., "Reptilia" excluding birds) or polyphyletic groups (unrelated organisms grouped by convergent traits, e.g., "Algae") [16] [17]. Phylogenetic classification names only clades, conveying evolutionary history without misleading "ranking," as identically ranked Linnaean groups (e.g., cat family vs. orchid family) are not equivalent in age, diversity, or biological differentiation [17].

Quantitative Landscape of Published Phylogenies

The scale of phylogenetic research has expanded dramatically, with large-scale databases now curating hundreds of thousands of published trees. The characteristics of these trees, however, present unique challenges for assembling a comprehensive Tree of Life.

Table 1: Characteristics of Published Phylogenies from Major Databases

| Database | Number of Trees | Source Publications | Median Species per Tree | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TimeTree Database [18] | > 4,000 | Papers from last five decades | 25 | A typical species is found in a median of just one timetree (0.02% of the sample). |

| TreeHub [19] | 135,502 | 7,879 articles across 609 journals | Not Specified | Provides a comprehensive, automatically curated dataset of phylogenetic trees and associated metadata. |

The data in Table 1 reveals a critical challenge: the taxonomic overlap between any two published phylogenies is extremely limited, with the average number of species common between any two trees being less than 1.0 [18]. This fragmentation, a result of taxon specialists focusing on specific groups and the use of different genetic loci or models for different clades, complicates the integration of individual trees into a cohesive Tree of Life [18].

Methodological Framework: From Data to Tree

Constructing a reliable phylogenetic tree involves a multi-step process where choices at each stage significantly impact the accuracy of the final result [13]. The following workflow outlines the key stages and considerations in modern phylogenetic analysis.

Orthology Prediction and Multiple Sequence Alignment

The first critical step is identifying orthologs—genes in different species that originated from a common ancestral gene via speciation [13]. Distinguishing orthologs from paralogs (genes related by duplication) is essential, as only orthologs reflect species divergence. This is typically achieved using computational tools like OrthoFinder, OMA, and OrthoMCL [13]. Subsequently, orthologous sequences are aligned into a Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA), which positions homologous nucleotides or amino acids into columns, providing the data matrix for inferring evolutionary relationships [13].

Phylogenetic Inference Methods and Models

Several optimality criteria and computational methods are used to infer trees from aligned sequence data [12].

- Maximum Likelihood (ML): This method evaluates phylogenetic trees based on the probability of observing the sequence data given a specific tree topology and an explicit model of sequence evolution. It seeks the tree that maximizes this likelihood [12] [13].

- Bayesian Inference: This approach uses probabilistic models to estimate the posterior probability of a tree, incorporating prior knowledge (e.g., a molecular clock) and the likelihood of the data. It is often implemented with Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithms [12].

- Parsimony: This principle seeks the tree that requires the smallest number of evolutionary changes to explain the observed data [12]. While conceptually simple, it can be misled by high levels of homoplasy (convergent evolution).

The choice of a substitution model is crucial, as it mathematically describes the process of sequence evolution. Poor model choice can lead to systematic errors, such as Long Branch Attraction (LBA), where non-related branches with high evolutionary rates are incorrectly grouped together [13].

Advanced Genomic-Era Protocols

The Chronological Supertree Algorithm (Chrono-STA)

A major recent innovation for Tree of Life assembly is the Chronological Supertree Algorithm (Chrono-STA), designed to integrate numerous molecular timetrees (trees scaled to time) with extremely limited species overlap [18]. Unlike methods that impute missing distances or use a backbone taxonomy, Chrono-STA uses node ages to merge species by iteratively connecting the most closely related species across all input trees. A key innovation is the back-propagation of formed clusters to all input trees, which progressively enhances information content and inference power [18]. As shown in Figure 2, this approach can correctly assemble a supertree from fragmented data where other methods fail.

Phylogenomic Data Requirements

In the genomic era, the standards for phylogenetic data have increased substantially. Journals like Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution now prioritize studies based on genome-wide datasets obtained via next-generation sequencing. Analyses based on few taxa and single molecular markers (e.g., single mitochondrial genes) are generally no longer considered for publication. Multi-locus datasets providing signal from across the genome are a minimum requirement, reflecting a shift towards phylogenomics [15].

Table 2: Essential Resources for Modern Phylogenetic Research

| Resource Category | Example(s) | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Orthology Databases | OrthoDB, OMA, PANTHER, PhylomeDB [13] | Provide pre-computed clusters of orthologous genes across a wide range of species, essential for dataset construction. |

| Phylogenetic Software | ASTRAL, OrthoFinder, RAxML, MrBayes [18] [13] | Perform core computational tasks: orthology inference, multiple sequence alignment, and tree inference under ML or Bayesian criteria. |

| Tree Repositories | TreeBASE, Open Tree of Life, TreeHub [19] | Curate and provide access to published phylogenetic trees for comparative analysis, meta-study, and supertree construction. |

| Taxonomic Databases | NCBI Taxonomy [19] | Provide a standardized taxonomic nomenclature for assigning species identities to genetic data. |

| Supertree Tools | Chrono-STA, ASTRAL-III, Asteroid [18] | Integrate multiple, overlapping source trees into a larger supertree to reconstruct broader evolutionary relationships. |

Applications in Research and Industry

The accurate reconstruction of evolutionary history has profound practical implications across multiple fields.

- Drug Discovery & Design: Phylogenetics allows scientists to screen closely related species for medically useful traits. For example, by identifying venomous fish species and their relatives, researchers can pinpoint candidates for discovering new venom-derived compounds, which have led to drugs like ACE inhibitors and Prialt (Ziconotide) [12].

- Epidemiology and Pathogen Tracking: Molecular phylogenetic analysis is used to investigate pathogen outbreaks (e.g., HIV, COVID-19) by analyzing the epidemiological linkage between genetic sequences, helping to identify transmission sources and patterns [14].

- Conservation Biology: Phylogenetics helps identify species that are evolutionarily distinct and have no close relatives. Protecting these species maximizes the preservation of phylogenetic diversity, which represents the total amount of evolutionary history in a ecosystem [20] [14].

- Comparative Genomics and Gene Function Prediction: Phylogenetic trees are key to inferring the origins of new genes, detecting molecular adaptation, and predicting the functions of unknown genes in one species based on their characterized orthologs in other species [14] [13].

The dual aims of modern phylogenetics—to infer accurate genealogies and establish a unified classification—are increasingly within reach due to genomic technologies and sophisticated computational methods. The field has moved from narrative scenarios to data-intensive, hypothesis-driven science, leveraging genome-wide datasets and innovative algorithms like Chrono-STA to assemble the Tree of Life from thousands of fragmented source trees. As phylogenetic resources like TreeHub continue to grow and methods continue to improve, the resulting "fairly true genealogical trees" will continue to revolutionize our understanding of life's history and provide critical insights for medicine, conservation, and fundamental biology.

Methods and Cutting-Edge Applications in Disease Research and Drug Discovery

The field of molecular phylogenetics has been transformed by the advent of high-throughput sequencing technologies, which generate genomic-scale datasets with thousands of loci for phylogenetic analysis. This data explosion presents unprecedented computational challenges, particularly in handling site heterogeneity—where different genomic regions evolve at distinct rates—and in scaling analyses to accommodate massive taxonomic sampling across the tree of life. Site heterogeneity arises as a major challenge because a single homogeneous model cannot accurately describe the evolution of all sites, potentially leading to incorrect tree reconstructions. Partitioned models address this by grouping sites with similar evolutionary patterns and applying distinct models to each group, but determining the optimal partitioning scheme is computationally demanding.

Simultaneously, initiatives aimed at reconstructing the entire Tree of Life must integrate thousands of published phylogenies with extremely limited taxonomic overlap. A survey of published literature reveals that individual phylogenies are frequently restricted to specific taxonomic groups, with any given species present in only a minuscule fraction of available trees. This necessitates the development of novel supertree methods that can combine these fragmented insights into a comprehensive evolutionary framework. This technical guide examines cutting-edge computational tools and algorithms designed to address these challenges, from single-locus partitioning to genome-scale analyses, providing researchers with methodologies to enhance the accuracy and efficiency of phylogenetic inference.

Core Algorithmic Advances in Phylogenetics

PsiPartition: Optimized Site Partitioning via Bayesian Optimization

PsiPartition represents a significant advance in partitioning genomic data for phylogenetic analysis. Traditional partitioning methods rely on heuristic or greedy search algorithms to determine the best partitioning scheme, approaches that are often time-consuming and offer no guarantee of optimality. In contrast, PsiPartition utilizes parameterized sorting indices of sites combined with Bayesian optimization to efficiently determine the optimal number of partitions and their composition [21] [22].

The core innovation of PsiPartition lies in its reformulation of the partitioning problem. Rather than treating partitioning as a discrete clustering problem, it uses continuous parameterized sorting indices that encode site characteristics relevant to evolutionary rate heterogeneity. Bayesian optimization then efficiently searches this continuous space to maximize phylogenetic model fit as measured by standard criteria like the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) and the corrected Akaike Information Criterion (AICc) [21].

Table 1: Performance Metrics of PsiPartition Versus Traditional Methods

| Metric | Traditional Methods | PsiPartition | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| BIC/AICc Score | Baseline | Significantly better [21] | Statistically significant improvement |

| Robinson-Foulds Distance | Baseline | Evidently and stably lower [21] | Especially pronounced with high site heterogeneity |

| Processing Speed | Variable, often slow for large datasets | Significantly improved for large datasets [22] | 2.57-5.38x acceleration possible with sparsification [23] |

| Optimal Partition Identification | Heuristic, no optimality guarantee | First general framework for efficient determination [21] | Bayesian optimization provides theoretical guarantees |

Experimental validation on both empirical and simulated datasets demonstrates that PsiPartition outperforms existing methods in terms of BIC, AICc, and the Robinson-Foulds (RF) distance between true simulated trees and reconstructed trees. The performance advantage is particularly evident on data with substantial site heterogeneity, where inappropriate modeling can most severely impact topological accuracy [21]. The method's robustness across different alignment lengths and numbers of loci makes it particularly valuable for phylogenomic studies where data characteristics may vary substantially across loci.

Chrono-STA: Supertree Construction with Chronological Data

For assembling the Tree of Life from published phylogenies with minimal taxonomic overlap, Chrono-STA (Chronological Supertree Algorithm) introduces a novel approach that leverages node ages from published molecular timetrees. Unlike existing supertree methods that impute missing nodal distances or decompose input trees into quartets, Chrono-STA builds supertrees by integrating chronological data, iteratively connecting the most closely related species across all input trees based on their divergence times [18].

The algorithm's key innovation is its back-propagation step: once species clusters are formed, this information is propagated back to all input trees, effectively increasing their information content and enhancing the power of subsequent clustering steps. This approach enables Chrono-STA to handle the extreme lack of taxonomic overlap characteristic of published phylogenies, where the median number of species common between any two trees is less than 1.0 [18].

Table 2: Comparison of Supertree Methods for Tree of Life Construction

| Method | Core Approach | Handles Limited Overlap | Uses Divergence Times | Requires Backbone |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chrono-STA | Chronological clustering with back-propagation | Excellent [18] | Yes | No |

| ASTRAL-III | Quartet reconciliation from gene trees | Poor [18] | No | No |

| ASTRID | Imputation of missing nodal distances | Poor [18] | No | No |

| HAL | Hierarchical average linkage with NCBI taxonomy | Moderate [18] | Yes | Yes |

| Asteroid | Distance matrix imputation | Poor [18] | No | No |

In tests comparing supertree methods on datasets with minimal taxonomic overlap, Chrono-STA successfully reconstructed the correct topology where other methods failed. This capability makes it particularly valuable for constructing comprehensive phylogenetic frameworks from the fragmented phylogenies that dominate the literature, moving beyond the limitations of extraction-based approaches like DateLife and the Open Tree of Life, which can only return subsets of pre-existing synthetic trees [18].

Managing Genome-Scale Data: Sparsification and Databases

Sparsified Genomics for Large-Scale Analyses

The concept of sparsified genomics addresses the computational bottlenecks associated with analyzing massive genomic datasets. This approach systematically excludes redundant bases from genomic sequences, creating shorter, sparsified sequences that can be processed more quickly while maintaining analytical accuracy comparable to processing non-sparsified sequences [23].

The Genome-on-Diet framework implements sparsified genomics using a repeating pattern sequence to determine which bases to include or exclude. This method reduces redundant information in genomic sequences where each base typically appears in multiple overlapping seeds, causing computational overhead. When applied to read mapping with minimap2, sparsification accelerates processing by 2.57-5.38x for Illumina reads, 1.13-2.78x for HiFi reads, and 3.52-6.28x for ONT reads, while maintaining comparable memory footprint and providing a 2x smaller index size [23].

For containment searches through large genomes and databases, sparsification offers even more dramatic improvements: 72.7-75.88x faster processing (1.62-1.9x with preprocessed indexing) and 723.3x greater storage efficiency compared to non-sparsified genomic sequences. In taxonomic profiling of metagenomic samples, sparsification enables 54.15-61.88x faster (1.58-1.71x with preprocessed indexing) and 720x more storage-efficient analysis compared to state-of-the-art tools like Metalign [23].

TreeHub: A Comprehensive Phylogenetic Tree Database

The TreeHub dataset addresses the critical need for comprehensive, up-to-date phylogenetic resources by automatically extracting phylogenetic data and integrating relevant species information from scientific papers and public databases. This resource includes 135,502 phylogenetic trees from 7,879 research articles across 609 academic journals, spanning a wide range of taxa including archaea, bacteria, fungi, viruses, animals, and plants [19].

Unlike previous databases like TreeBASE that relied on voluntary researcher uploads and have update limitations, TreeHub employs automated extraction from platforms like Dryad and FigShare, using digital object identifiers (DOIs) to link trees to publications. The database incorporates sophisticated taxonomic assignment through natural language processing of publication titles and abstracts combined with analysis of terminal node labels in tree files [19].

TreeHub's structure includes several interconnected data tables:

- Tree and TreeFile: Store the phylogenetic trees and raw tree files

- Study: Contains related article metadata

- Taxonomy: Provides taxon information

- Matrix: Stores sequence alignments

- Submit: Tracks submission and crawling information

This comprehensive resource supports evolutionary biology research by providing reliable, accessible phylogenetic data that can be queried through a dedicated website or downloaded in bulk for large-scale analyses.

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Detailed Protocol: Implementing PsiPartition for Phylogenomic Analysis

Objective: To implement PsiPartition for partitioning genomic data and reconstructing phylogenetic trees with improved accuracy.

Materials and Input Data:

- Genomic sequences: Multi-sequence alignment in FASTA, NEXUS, or PHYLIP format

- Computational resources: Standard workstation or high-performance computing cluster

- Software dependencies: Python 3.7+, DendroPy, NumPy, SciPy, scikit-learn

Procedure:

- Data Preparation:

- Format input alignment in standard phylogenetic format (FASTA recommended)

- Validate alignment using DendroPy to ensure proper formatting [19]

Parameter Initialization:

- Define parameter ranges for Bayesian optimization (number of partitions, sorting index parameters)

- Set optimization criteria (BIC or AICc) based on dataset size and research goals

Bayesian Optimization Execution:

- Execute the PsiPartition algorithm with command-line or Python API

- Monitor convergence of Bayesian optimization (typically 50-100 iterations)

Partition Scheme Application:

- Apply optimal partitioning scheme to genomic alignment

- Generate partition file compatible with common phylogenetic software (RAxML, IQ-TREE, MrBayes)

Phylogenetic Analysis:

- Conduct tree reconstruction under the optimized partitioning scheme

- Compare results with non-partitioned or alternatively partitioned analyses using Robinson-Foulds distance [21]

Validation:

- Bootstrap analysis: Assess branch support under the optimized partitioning

- Comparison to simulated trees: Calculate Robinson-Foulds distance when ground truth is known [21]

- Model fit evaluation: Compare BIC/AICc scores against alternative partitioning approaches

Workflow: Constructing Supertrees with Chrono-STA

Objective: To integrate multiple published timetrees into a comprehensive supertree using Chrono-STA.

Input Requirements:

- Time-calibrated phylogenies: Two or more timetrees with divergence estimates

- Taxonomic overlap: Minimal overlap sufficient (can handle cases with <1 shared species on average) [18]

Methodology:

- Data Collection and Curation:

- Gather published timetrees from literature or databases like TreeHub [19]

- Extract node ages and topological constraints from each source tree

- Standardize taxonomic names across trees to resolve synonymies

Chrono-STA Implementation:

- Input all timetrees with their node age estimates

- Run chronological clustering algorithm to identify most closely related species pairs across trees

- Execute iterative back-propagation to enhance topological information across all inputs

Supertree Validation:

- Compare resulting supertree to taxonomic backbones (e.g., NCBI Taxonomy)

- Assess conflict resolution across input trees

- Evaluate temporal consistency of divergence time estimates

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Modern Phylogenomics

| Tool/Resource | Primary Function | Application Context | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| PsiPartition | Site partitioning for heterogeneous genomic data | Phylogenomic analysis under site heterogeneity [21] [22] | Bayesian optimization; Automated optimal partition detection; Improved BIC/AICc scores |

| Chrono-STA | Supertree construction from timetrees | Tree of Life assembly from published phylogenies [18] | Uses divergence times; Handles minimal taxonomic overlap; No backbone requirement |

| TreeHub | Phylogenetic tree database | Access to comprehensive tree collections [19] | 135,502 trees from 7,879 articles; Automated extraction; Taxonomic name resolution |

| Genome-on-Diet | Genomic sequence sparsification | Accelerating large-scale genomic comparisons [23] | 2.57-5.38x read mapping acceleration; 72.7-75.88x faster containment search |

| OrthoMCL DB | Orthologous group identification | Gene selection for phylogenomic studies [24] | 124,740 orthologous groups; 98 eukaryotes + 44 bacteria + 16 archaea |

The computational landscape of molecular phylogenetics is evolving rapidly to meet the challenges posed by genomic-scale data and ambitious projects like the complete Tree of Life. Tools like PsiPartition address fundamental modeling challenges such as site heterogeneity through sophisticated optimization approaches, while Chrono-STA provides novel solutions for integrating phylogenetic knowledge from thousands of specialized studies. Simultaneously, frameworks for sparsified genomics enable efficient processing of massive datasets, and comprehensive resources like TreeHub ensure that the growing body of phylogenetic knowledge remains accessible and usable.

These advances collectively empower researchers to tackle increasingly complex evolutionary questions with greater accuracy and efficiency. As phylogenetic data continues to grow in both volume and complexity, the continued development and refinement of computational tools will remain essential for reconstructing the evolutionary history of life on Earth and applying this knowledge to challenges in fields ranging from conservation biology to drug development.

Phylodynamics is a synthetic analytical framework that interprets the interaction of evolutionary and ecological processes to understand the transmission dynamics of rapidly evolving pathogens [25]. It represents a specialized application within the broader field of molecular phylogenetics, which uses DNA, RNA, or protein sequences to build evolutionary trees and reveal relationships between species and populations [26]. The term was introduced by Grenfell et al. (2004) to describe the "melding of immunodynamics, epidemiology, and evolutionary biology" required to analyze pathogens for which both evolutionary and ecological processes operate on the same time scale [25].

This approach is fundamentally rooted in the concept of the "Tree of Life," using phylogenetic trees as central tools to represent inferred evolutionary relationships among various biological species or other entities based upon similarities and differences in their physical or genetic characteristics [27]. Within this context, phylodynamics leverages the fact that epidemiological spread leaves traces in the form of substitutions in pathogen genomes that can be used to reconstruct transmission histories [28]. Pathogen populations meeting this assumption are termed 'measurably evolving populations' [28].

Core Principles and Theoretical Framework

Foundational Concepts

Phylodynamics operates on several key principles that bridge evolutionary biology and epidemiology:

- Measurably Evolving Populations: Pathogen populations accumulate genetic changes rapidly enough that evolution can be observed in real-time, enabling the reconstruction of transmission dynamics from genetic sequences [28]

- Molecular Clock Hypothesis: Genetic changes accumulate at a roughly constant rate over time, allowing researchers to estimate divergence times between species or strains [26]

- Epidemiological-Evolutionary Feedback: Ecological (transmission dynamics) and evolutionary (genetic change) processes interact continuously, each influencing the other [25]

Distinguishing Phylogenetic Epidemiology from Phylodynamics

Two distinct pursuits are often labeled phylodynamics [25]:

- Phylogenetic Epidemiology: Uses neutral genetic variation to track ecological processes and population dynamics, reconstructing past ecological and population events from genetic variation

- Phylodynamics Sensu Stricto: Analyzes the interaction of evolutionary and ecological processes through joint modeling of both, accounting for how mutations actively influence population and ecological processes through Darwinian selection

Phylodynamic Applications in Public Health

Tracking Pathogen Evolution and Transmission

Molecular phylogenetics tracks pathogen evolution and transmission patterns by analyzing genetic sequences from different isolates [26]. Key applications include:

- Reconstructing Transmission Routes: Pathogen phylogenetic trees reveal geographic origins of disease outbreaks and transmission routes between populations or regions [26]

- Estimating Evolutionary Timelines: Molecular clock analyses of pathogen sequences estimate disease emergence timing and major evolutionary events in pathogen history [26]

- Real-time Epidemic Monitoring: Phylodynamic approaches combine phylogenetics with epidemiological data to model infectious disease spread in real-time [26]

Analyzing Host-Pathogen Interactions

Phylodynamic methods provide critical insights into host-pathogen co-evolution:

- Co-evolutionary Analysis: Comparing host and pathogen phylogenies elucidates co-evolutionary relationships and host-switching events [26]

- Trait Evolution Tracking: Identifying genetic changes associated with increased virulence, drug resistance, or host adaptation in pathogens [26]

- Zoonotic Disease Prediction: Phylogenetic methods applied to zoonotic diseases help predict potential future pandemics and inform public health strategies [26]

Informing Public Health Interventions

The practical public health applications of phylodynamics are substantial:

- Outbreak Containment: Determining transmission networks to target containment efforts effectively [25]

- Vaccine Strategy Development: Tracking antigenic evolution to inform vaccine composition decisions [25]

- Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring: Predicting and monitoring pathogen drug resistance evolution to combat antimicrobial resistance [26]

Key Epidemiological Parameters Inferred from Phylodynamics

Table 1: Key Epidemiological Parameters Inferred through Phylodynamic Analysis

| Parameter | Description | Public Health Significance | Inference Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reproductive Number (R₀ or Rₑ) | Average number of secondary infections from an individual case | Determines outbreak control requirements; values >1 indicate sustained transmission | Coalescent theory, birth-death models [28] [25] |

| Time to Most Recent Common Ancestor (tMRCA) | Time when all current sequences share a common ancestor | Estimates outbreak origin timing and duration | Molecular clock dating [28] |

| Substitution Rate | Rate of genetic change (substitutions/site/year) | Determines evolutionary rate and molecular clock calibration | Bayesian evolutionary analysis [28] |

| Effective Population Size | Genetic diversity and its changes over time | Reflects transmission dynamics and population bottlenecks | Bayesian skyline plots [25] |

Methodological Workflow and Experimental Protocols

Standard Phylodynamic Analysis Pipeline

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for conducting phylodynamic analysis:

Data Collection and Preprocessing Protocols

Pathogen Genome Sequencing

- Objective: Obtain high-quality genome sequences from pathogen isolates

- Protocol:

- Extract nucleic acids from clinical specimens using standardized kits

- Prepare sequencing libraries ensuring appropriate coverage depth

- Sequence using next-generation platforms (Illumina, Nanopore)

- Conduct quality control: minimum coverage (typically 20x), completeness thresholds

- Critical Considerations: Sample selection should represent temporal and spatial diversity of outbreak

Metadata Collection

- Essential Elements: Precise sampling dates, geographic location, clinical context, host information

- Data Standardization: Use controlled vocabularies and standardized formats for data sharing

- Privacy Protection: Implement protocols for de-identification while maintaining data utility [28]

Phylogenetic Tree Construction Methodology

Multiple Sequence Alignment

- Objective: Generate accurate alignment of homologous sequences

- Protocol:

- Use alignment algorithms (MAFFT, ClustalW/X) with parameters optimized for pathogen type [27]

- Visually inspect and manually refine alignments as necessary

- Trim poorly aligned regions using automated tools (Gblocks, TrimAl)

- Quality Metrics: Assess alignment consistency, presence of conserved regions

Evolutionary Model Selection

- Objective: Identify best-fitting substitution model for the dataset

- Protocol:

- Test multiple substitution models (HKY, GTR, codon models)

- Compare model fit using statistical criteria (AIC, BIC)

- Incorporate rate variation among sites (Gamma distribution, invariant sites)

- Software Tools: ModelTest, PartitionFinder

Phylodynamic Inference Methods

Coalescent-Based Approaches

- Objective: Infer population dynamics from genetic sequences

- Protocol:

- Implement coalescent models (Bayesian Skyline, Gaussian Markov Random Field)

- Run Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) analyses with adequate chain length

- Assess convergence using effective sample size (ESS > 200) and trace plots

- Software Implementation: BEAST2, MrBayes

Birth-Death Models

- Objective: Estimate transmission rates and reproductive numbers

- Protocol:

- Specify birth-death model parameters (transmission rate, removal rate)

- Incorporate incomplete sampling through sampling proportions

- Calibrate clock models (strict, relaxed) based on data characteristics

- Epidemiological Parameterization: Relate birth rate to transmission rate, death rate to recovery rate

Technical Implementation and Data Considerations

Sampling Date Precision and Its Impact on Inference

The precision of sampling dates significantly affects phylodynamic inference accuracy [28]. Date-rounding to protect patient confidentiality can introduce substantial bias:

Table 2: Impact of Date-Rounding on Phylodynamic Inference Across Pathogens

| Pathogen | Evolutionary Rate (subs/site/year) | Genome Size (bp) | Average Time per Substitution | Biases Observed at Month Resolution | Biases Observed at Year Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 | ~1×10⁻³ | ~30,000 | ~1 per 1-2 weeks | Significant bias in Rₑ, tMRCA, substitution rate [28] | Severe bias in all parameters [28] |

| H1N1 Influenza | ~4×10⁻³ | ~13,158 | ~1 per week | Significant bias [28] | Severe bias [28] |

| Staphylococcus aureus | ~1×10⁻⁶ | ~2,800,000 | ~1 per 3-4 months | Minimal bias [28] | Significant bias [28] |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | ~5×10⁻⁹ | ~4,400,000 | ~1 per 45 years | No significant bias [28] | Minimal bias [28] |

Computational Requirements and Implementation

Software Tools for Phylodynamic Analysis

- BEAST2: Bayesian evolutionary analysis with extensive model selection

- MrBayes: Bayesian phylogenetic inference using MCMC methods

- IQ-TREE: Maximum likelihood phylogeny inference with model finding

- TreeTime: Molecular clock inference and phylodynamics

Data Quality Assessment Protocols

- Sequence Quality Metrics: Coverage depth, completeness, absence of contamination

- Temporal Signal Assessment: Root-to-tip regression to clock-likeness

- Convergence Diagnostics: MCMC convergence statistics, effective sample sizes

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Phylodynamics

| Category | Specific Items/Tools | Function/Application | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wet Lab Reagents | Nucleic acid extraction kits, reverse transcription reagents, PCR amplification kits, sequencing library preparation kits | Pathogen genome sequence generation | Quality control critical for downstream analysis |

| Bioinformatics Tools | ClustalW/X [27], MAFFT, BEAST2 [28], Bayesian skyline plots [25] | Sequence alignment, phylogenetic reconstruction, phylodynamic inference | Computational resources scale with dataset size |

| Evolutionary Models | HKY, GTR, codon models, coalescent models, birth-death models | Statistical framework for evolutionary inference | Model selection critical for accurate parameter estimation |

| Data Resources | GISAID, NCBI databases, outbreak epidemiology data | Source sequences and contextual metadata | Data standardization essential for integration |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Integration with Epidemiological Data

Advanced phylodynamic approaches integrate multiple data sources:

- Structured Models: Incorporate host contact networks, spatial information, and population structure [25]

- Multi-scale Analysis: Bridge within-host evolution and between-host transmission dynamics

- Real-time Surveillance: Develop platforms for ongoing outbreak monitoring and response

Methodological Innovations

Future methodological developments address current limitations:

- Privacy-Preserving Methods: Developing approaches for safer sharing of sampling dates, such as uniform translation by a random number [28]

- Integrated Modeling: Coupling dynamical epidemiological models with population genetic processes [25]

- Machine Learning Enhancement: Incorporating machine learning approaches to handle complex, high-dimensional data

Public Health Implementation Challenges

Translating phylodynamic insights into public health action requires addressing several challenges:

- Timeliness: Reducing analytical turnaround time for outbreak response

- Interpretability: Communicating complex phylogenetic results to public health decision-makers

- Data Integration: Combining genomic data with traditional surveillance data streams

- Ethical Considerations: Balancing privacy concerns with data utility for public health protection [28]

Phylodynamics represents a powerful synthesis of molecular phylogenetics and epidemiological dynamics, providing unprecedented insights into pathogen evolution and transmission. Its integration into public health practice has transformed our ability to respond to infectious disease threats, from pandemic viruses to endemic pathogens. As methodological innovations continue to address current challenges around data quality, computational efficiency, and privacy protection, phylodynamics is poised to become an increasingly central component of public health infrastructure for outbreak prevention, detection, and response within the broader context of molecular phylogenetics and Tree of Life research.

Resolving Taxonomic Disputes and Assessing Biodiversity for Conservation

Molecular phylogenetics, which uses DNA, RNA, or protein sequences to build evolutionary trees, has revolutionized evolutionary biology and conservation science [26]. This powerful toolset allows scientists to elucidate the relationships between species and populations, understand speciation patterns, estimate divergence times, and integrate genetic data with other evidence such as fossil records [26]. The field is particularly crucial for taxonomic classification and biodiversity assessment, providing a principled framework for quantifying biological variation and guiding conservation priorities.