Navigating the Fitness Landscape: Optimizing Genetic Algorithms for Biomedical Code and Drug Discovery

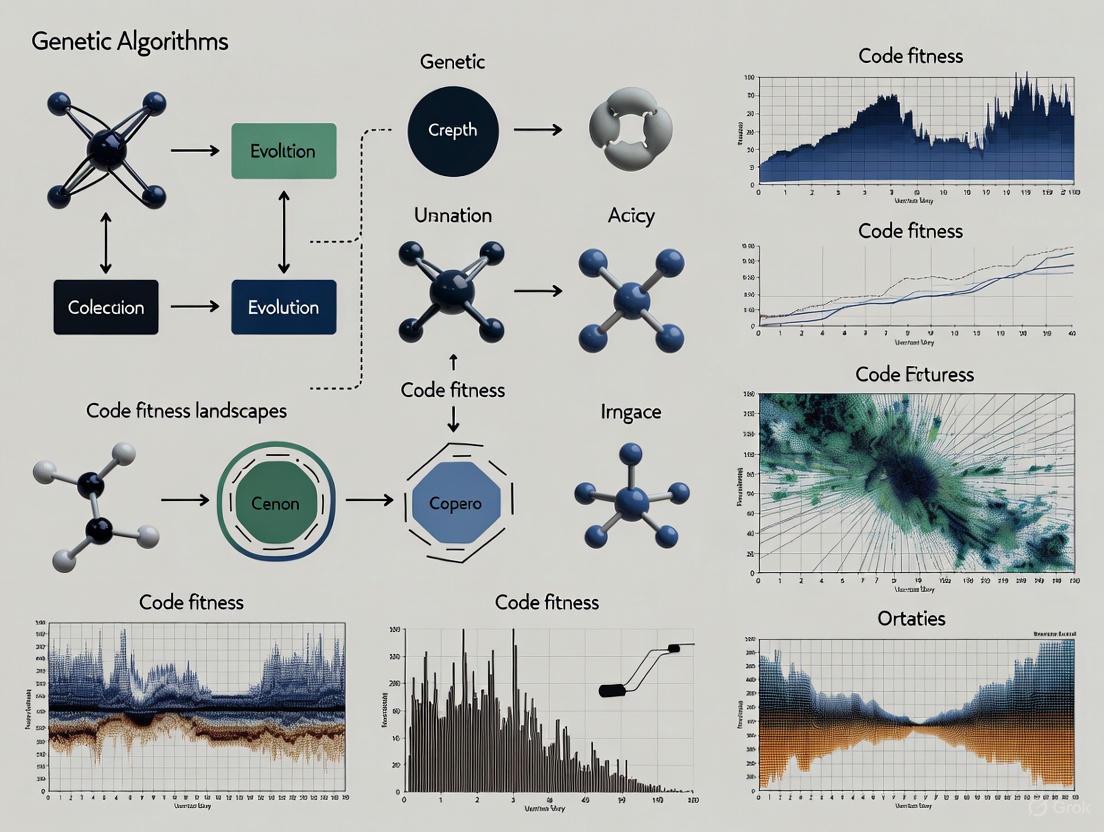

This article explores the critical role of Genetic Algorithms (GAs) in optimizing solutions for complex, non-differentiable fitness landscapes, with a special focus on applications in drug development and biomedical research.

Navigating the Fitness Landscape: Optimizing Genetic Algorithms for Biomedical Code and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the critical role of Genetic Algorithms (GAs) in optimizing solutions for complex, non-differentiable fitness landscapes, with a special focus on applications in drug development and biomedical research. As population-based, stochastic optimizers, GAs excel where traditional gradient-based methods fail, particularly in rugged search spaces common in real-world problems like de novo drug design and network controllability analysis. We delve into foundational concepts, advanced methodological adaptations such as novel crossover operators, and strategies for overcoming challenges like premature convergence. Through a comparative lens, we validate GA performance against other optimization techniques and highlight its proven utility in generating synthetic data for imbalanced learning and identifying drug repurposing candidates, providing researchers and scientists with a comprehensive guide for leveraging GAs in their computational pipelines.

The Foundation of Genetic Algorithms and the Challenge of Fitness Landscapes

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between Genetic Algorithms and traditional optimization methods?

Genetic Algorithms (GAs) are a class of evolutionary algorithms inspired by natural selection, belonging to the larger field of Evolutionary Computation (EC) [1] [2]. Unlike traditional gradient-based methods that require continuously differentiable objective functions, GAs can handle non-continuous functions and domains with ease [3]. They are population-based metaheuristics that perform a parallel, stochastic search, making them less likely to get trapped in local optima compared to traditional methods that often start from a single point and follow a deterministic path [3] [4].

Q2: When should I consider using a Genetic Algorithm for my optimization problem?

GAs are particularly suitable for problems with the following characteristics [3] [5] [6]:

- The search space is large, complex, or poorly understood

- The problem has multiple local optima where traditional methods get stuck

- The objective function is not differentiable, noisy, or has discontinuous domains

- No analytical solution method exists, but potential solutions can be evaluated

- Good solutions are sufficient; finding the global optimum is not strictly necessary

- Problem knowledge can be incorporated through an appropriate representation and fitness function

Q3: What are the most critical parameters to tune in a Genetic Algorithm implementation?

The performance of GAs is sensitive to several key parameters that often require careful tuning [1] [6]:

- Population size: Affects genetic diversity and computational resources

- Crossover rate: Controls how frequently genetic material is recombined

- Mutation rate: Determines how often random changes are introduced

- Selection pressure: Influences how strongly fitter individuals are favored

- Elitism: Whether and how many best individuals are preserved unchanged

Table 1: Key Genetic Algorithm Parameters and Their Effects

| Parameter | Typical Range | Effect if Too Low | Effect if Too High |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population Size | 50-1000 | Premature convergence | Slow convergence, computationally expensive |

| Crossover Rate | 0.6-0.9 | Limited exploration | Disruption of good solutions |

| Mutation Rate | 0.001-0.01 | Loss of diversity, stagnation | Loss of good solutions, random search |

| Tournament Size | 2-5 (for tournament selection) | Weak selection pressure | Too strong selection pressure, premature convergence |

Q4: How can I handle constraints in Genetic Algorithm implementations?

Constraint handling in GAs can be implemented through several approaches [6]:

- Penalty functions: Incorporate constraint violations into the fitness function

- Repair operators: Transform infeasible solutions into feasible ones

- Specialized representations/operators: Design encoding and genetic operators that maintain feasibility

- Decoders: Use mapping from genotype to phenotype that ensures constraints are satisfied The choice depends on problem characteristics, with penalty functions being the most commonly used approach for their simplicity.

Q5: What computational resources are typically required for Genetic Algorithm experiments?

The computational requirements for GAs vary significantly based on problem complexity [1] [6]:

- Fitness function evaluation is often the most computationally expensive component

- Population-based nature allows for parallelization across multiple cores or distributed systems

- Memory requirements scale with population size and chromosome complexity

- For complex real-world problems (e.g., structural optimization), a single fitness evaluation may require hours or days of simulation

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Premature Convergence - The algorithm converges quickly to a suboptimal solution

Symptoms: Population diversity drops rapidly; fitness improves quickly then stagnates at mediocre level; all individuals in population become very similar.

- Increase mutation rate (within 0.01-0.1 range)

- Increase population size (try doubling current size)

- Use diversity-preserving mechanisms (fitness sharing, crowding)

- Implement niching or speciation techniques

- Adjust selection pressure (reduce tournament size or fitness scaling)

- Introduce random immigrants (replace portion of population with new random individuals)

Table 2: Troubleshooting Premature Convergence

| Cause | Diagnostic Signs | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Excessive selection pressure | Fitness improves very rapidly in early generations | Reduce tournament size; Use rank-based instead of fitness-proportional selection |

| Insufficient mutation | Low population diversity measurements | Increase mutation rate; Implement adaptive mutation |

| Small population size | Quick drop in number of unique genotypes | Increase population size; Introduce migration in distributed models |

| Genetic drift | Random loss of valuable genetic material | Implement elitism; Use larger populations |

Problem: Slow Convergence - The algorithm takes too long to find good solutions

Symptoms: Fitness improves very gradually over many generations; algorithm fails to find satisfactory solutions within reasonable time.

- Increase selection pressure (higher tournament size or fitness scaling)

- Adjust crossover and mutation rates (increase crossover, decrease mutation)

- Use problem-specific knowledge in operators or representation

- Implement local search (memetic algorithms)

- Hybridize with other optimization methods

- Check fitness function implementation for errors or miscalculations

Problem: Maintaining Diversity in Code Fitness Landscapes

Symptoms: In code synthesis and algorithm design tasks, population converges to similar structures despite multimodal fitness landscape.

- Implement novelty search alongside fitness-based selection

- Use multi-objective optimization balancing fitness and behavioral diversity

- Employ quality-diversity algorithms

- Define appropriate distance metrics for code structures

- Implement island models with periodic migration

Diagram 1: Diversity Maintenance Workflow

Experimental Protocols for Code Fitness Landscape Research

Protocol 1: Baseline Genetic Algorithm for Code Synthesis

Objective: Establish performance baseline for code generation tasks.

- Representation: Use linear genome representation (binary or integer) for simple code structures or tree-based representation for complex programs

- Initialization: Generate random population using appropriate building blocks for target domain

- Fitness Evaluation: Execute generated code on test cases; fitness proportional to correctness and efficiency

- Genetic Operators:

- Crossover: Single-point or subtree exchange (for tree representation)

- Mutation: Point mutation or subtree replacement

- Parameters: Population size=100, Generations=50, Crossover rate=0.8, Mutation rate=0.05

- Termination: Maximum generations reached or satisfactory solution found

Protocol 2: Fitness Landscape Analysis for Algorithm Design Tasks

Objective: Characterize the structure of fitness landscapes in algorithm search spaces.

- Graph-Based Representation: Model landscape as graph where nodes represent candidate algorithms and edges represent transitions

- Neighborhood Sampling: Generate neighbors through multiple mutation operators

- Ruggedness Measurement: Calculate autocorrelation and fitness-distance correlation

- Modality Assessment: Identify number and distribution of local optima

- Neutrality Analysis: Measure size and structure of neutral networks

Diagram 2: Fitness Landscape Analysis Protocol

Protocol 3: LLM-Assisted Algorithm Search (LAS) Integration

Objective: Leverage Large Language Models for enhanced algorithm design.

Methodology [8]:

- Representation: Combine code implementation with linguistic description of algorithm idea

- Initialization: Generate initial population using LLM prompts for diverse starting points

- Generation: Use LLMs to create offspring by mutating and recombining parent algorithms

- Evaluation: Test generated algorithms on benchmark problem instances

- Selection: Maintain population diversity while preserving high-performing individuals

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Genetic Algorithm Experiments

| Tool/Resource | Function/Purpose | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Fitness Function | Evaluates solution quality | Should be computationally efficient; often the bottleneck |

| Chromosome Representation | Encodes potential solutions | Choice affects operator design; binary, real-valued, tree-based |

| Selection Operator | Determines reproduction opportunities | Tournament, roulette wheel, rank-based selection |

| Crossover Operator | Combines parental genetic material | Single-point, multi-point, uniform, or problem-specific |

| Mutation Operator | Introduces random variations | Maintains diversity; prevents premature convergence |

| Population Manager | Handles generational transition | With/without elitism; steady-state or generational |

| Diversity Metric | Measures population variety | Genotypic, phenotypic, or behavioral diversity |

| Landscape Analyzer | Characterizes problem difficulty | Ruggedness, modality, neutrality measurements |

Advanced Tools for Code Fitness Landscapes:

- Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) Analyzers: Measure structural similarity between code individuals [8]

- Behavioral Diversity Metrics: Assess functional differences beyond syntactic variations [7]

- Neutral Network Trackers: Monitor movements through fitness-equivalent regions [7]

- Multi-objective Optimization Frameworks: Balance competing objectives like correctness, efficiency, and simplicity [6]

Advanced Techniques for Complex Landscapes

Handling Rugged and Multimodal Landscapes

Code fitness landscapes often exhibit high ruggedness and multimodality, particularly in algorithm design tasks [7] [8]. Implement these specialized techniques:

- Adaptive Operator Rates: Dynamically adjust mutation and crossover rates based on population diversity measurements

- Niching and Speciation: Maintain subpopulations in different regions of the search space using fitness sharing or clearing methods

- Island Models: Implement multiple demes with occasional migration to preserve diversity

- Restart Strategies: Trigger partial or complete restarts when convergence is detected

LLM-Assisted Evolutionary Search for Algorithm Design

Recent approaches combine evolutionary algorithms with Large Language Models [8]:

- Hybrid Representation: Combine code with textual descriptions of algorithm logic

- Semantic Operators: Use LLMs to perform meaningful mutations and recombination

- Guided Initialization: Seed initial population with LLM-generated promising candidates

- Explanation-Augmented Fitness: Use LLMs to explain why algorithms succeed or fail

Diagram 3: LLM-Assisted Genetic Algorithm Workflow

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key characteristics of a fitness landscape that most impact genetic algorithm performance? Several key characteristics significantly influence how a genetic algorithm navigates a fitness landscape. Ruggedness refers to landscapes with steep ascents, descents, and many local optima, which can cause algorithms to get stuck [10]. Modality describes the number of these optima (both global and local); highly multimodal problems have many basins of attraction (BoA), which are sets of solutions that lead to a particular optimum via a local search [10]. Neutrality appears as flat regions where moving to a neighboring solution doesn't change fitness, causing the algorithm to stagnate [10]. Finally, ill conditioning means the problem is extremely sensitive to tiny changes, leading to significant fitness shifts from small perturbations and making convergence difficult [10].

Q2: My genetic algorithm converges prematurely. Am I likely dealing with a rugged or deceptive landscape? Premature convergence often indicates a rugged or multi-modal landscape. Your algorithm is likely getting trapped in a local optimum that is not the global best solution [10]. In such landscapes, the diversity maintenance mechanism in your algorithm can sometimes even negatively impact performance due to the high number of attractive but suboptimal basins of attraction [10]. To diagnose this, you can use fitness landscape analysis (FLA) tools like the Nearest-Better Network (NBN) to visualize the number and distribution of these local optima [10].

Q3: How can I analyze the structure of an unknown fitness landscape from my specific problem? For black-box problems common in real-world applications, the Nearest-Better Network (NBN) is an effective visualization tool for analyzing landscapes of any dimensionality [10]. The NBN is a directed graph where nodes are sampled solutions and edges represent the "nearest-better" relationship—the closest solution with a better fitness value [10]. Visualizing this network can reveal characteristics like ruggedness, neutrality, ill-conditioning, and the size and number of attraction basins, helping you understand the specific challenges your algorithm must overcome [10].

Q4: What is an epistatic hotspot, and how does it organize a biological fitness landscape? In biological contexts like antibody evolution, an epistatic hotspot is a specific site in a sequence (e.g., an amino acid position) where a mutation has a non-additive effect, significantly altering the fitness effect of subsequent mutations at many other sites [11]. Counterintuitively, while these hotspots create ruggedness, they can also organize the landscape by "funneling" evolutionary paths toward the global optimum, making the landscape more navigable despite its apparent complexity [11]. This heterogeneous ruggedness can enhance, rather than reduce, the accessibility of the fittest genotype.

Q5: Are there specific algorithm modifications for navigating vast neutral regions on a fitness landscape? Yes, vast neutral regions—flat areas where fitness doesn't change—are a common challenge in real-world problems, sometimes even surrounding the global optimum [10]. Standard algorithms can become trapped in these regions. Effective strategies include incorporating adaptive chaotic perturbation, as used in hybrid genetic algorithms, to help escape flat areas [12]. Furthermore, algorithms with mechanisms to encourage directional movement even in neutral space can be beneficial, as pure fitness-driven selection provides no guidance in these regions.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Population Diversity Collapse on Rugged Landscapes

Symptoms: The algorithm's population converges rapidly to a single solution, which is a suboptimal local peak. Fitness stagnation occurs early in the run. Diagnosis: You are likely dealing with a highly rugged and multi-modal landscape. The algorithm's selection pressure is too high, and the crossover operator is not effectively exploring new regions. Solutions:

- Integrate Local Search: Combine your GA with a local search heuristic (like hill-climbing) in a memetic algorithm framework to refine solutions within basins of attraction.

- Implement Nicheing or Crowding: Use fitness sharing or deterministic crowding to maintain subpopulations in different peaks, preventing a single peak from dominating.

- Use Chaotic Maps for Initialization: Enhance the quality and diversity of the initial population using chaos theory, such as an improved Tent map, to ensure a better starting spread across the search space [12].

Problem: Stagnation in Vast Neutral Regions

Symptoms: The population's average and best fitness show no improvement over many generations, yet the genetic diversity of the population remains. Diagnosis: The algorithm is trapped in a large neutral network. Moves to neighboring solutions yield no fitness improvement, providing no gradient for selection to act upon. Solutions:

- Utilize Neutrality Metrics: Employ metrics from fitness landscape analysis, like those derived from a neutral walk, to detect neutrality [10].

- Modify Search Operators: Implement a "Neutral Mutation" strategy that preferentially accepts moves to solutions of equal fitness, allowing a drift across the neutral network.

- Apply Adaptive Chaotic Perturbation: After crossover and mutation, apply a small, adaptive chaotic perturbation to the best solutions to push them out of the neutral region [12].

Problem: Inefficient Search on Ill-Conditioned Landscapes

Symptoms: The algorithm makes very slow progress, with fitness improving in tiny increments. It is highly sensitive to parameter tuning and step sizes. Diagnosis: The fitness landscape is ill-conditioned, meaning it is extremely sensitive to small changes. Small perturbations lead to significant, often disruptive, changes in fitness [10]. Solutions:

- Adopt Covariance Matrix Adaptation (CMA): Use algorithms like CMA-ES, which dynamically learn and adapt a model of the landscape's topology to take appropriately scaled steps. Be cautious, as in some real-world problems with unclear global structure, CMA-ES may easily exceed problem boundaries [10].

- Leverage Dominant Blocks: Use association rule theory to mine dominant blocks (high-quality building blocks) from the population to reduce problem complexity and guide the search more effectively [12].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Fitness Landscape Analysis using Nearest-Better Network (NBN)

Purpose: To visualize and characterize the key topological features of an unknown fitness landscape. Background: The NBN is a powerful tool for analyzing problems of any dimensionality, capable of revealing characteristics like ruggedness, neutrality, and ill-conditioning [10]. Steps:

- Sampling: Collect a representative set of solutions, ( X ), from the search space. This can be done via random sampling or by running a preliminary, short algorithm and recording all visited points.

- Fitness Evaluation: Calculate the fitness, ( f(x) ), for every sampled solution ( x ) in ( X ).

- Construct NBN Graph: For each solution ( x ) in ( X ), find its "nearest-better" solution, ( b(x) ). This is the closest solution (by Euclidean or Hamming distance) that has a superior fitness ( f(y) > f(x) ) [10].

- Define Graph Elements: Create a directed graph where each node is a sampled solution. A directed edge is drawn from each solution ( x ) to its nearest-better ( b(x) ) [10].

- Visualization & Analysis: Visualize the resulting network. A highly interconnected graph with many edges crossing suggests ruggedness. Large, flat areas with few edges indicate neutrality. The overall "funnel-like" structure or lack thereof can indicate navigability.

Workflow Diagram:

Protocol 2: Mapping an Antibody Stability Fitness Landscape

Purpose: To empirically measure a high-dimensional, epistatic fitness landscape relevant to biological drug discovery. Background: This protocol is adapted from combinatorial mutagenesis studies that map the sequence-stability relationship of antibodies, revealing epistatic hotspots [11]. Steps:

- Library Design: Select key sequence sites (e.g., frequent somatic hypermutations). Create a combinatorially complete plasmid library containing all possible combinations of wild-type and mutant states at these sites (e.g., ( 2^{10} = 1024 ) variants) [11].

- Yeast Display Library Construction: Transform the plasmid library into a yeast strain so that each cell expresses a single antibody variant on its surface [11].

- Fitness Selection (Stability): Use Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) to sort cells based on fluorescence, which serves as a proxy for antibody stability and surface expression. Antibody variants that fold stably are enriched [11].

- Fitness Quantification: Sequence both the unsorted (input) and sorted (output) yeast display libraries. Quantify the fitness of each variant by its logarithmic enrichment of sequence reads after selection [11].

- Epistasis Modeling: Fit the resulting genotype-fitness data to a specific epistasis model (e.g., including pairwise ( J{ij} ) and third-order ( K{ijk} ) interaction terms) or a global epistasis model to identify the strength and location of epistatic interactions [11].

Workflow Diagram:

Table 1: Fitness Landscape Characteristics and Algorithm Performance

This table summarizes how different landscape features affect genetic algorithms and suggests mitigating algorithmic strategies.

| Landscape Characteristic | Impact on Genetic Algorithm | Mitigation Strategy | Example/Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ruggedness (Many local optima) | High risk of premature convergence at suboptimal peaks [10] | Nicheing/Crowding; Hybrid GA with local search | Real-world problems often contain many attraction basins [10] |

| Neutrality (Flat regions) | Search stagnates, no fitness gradient for selection [10] | Neutral drift; Adaptive chaotic perturbation [12] | Vast neutral regions can exist around the global optimum [10] |

| Ill-Conditioning (High sensitivity) | Slow convergence, sensitive to step size and parameters [10] | CMA-ES; Dominant block mining [12] | Causes even the best algorithms to fail or converge slowly [10] |

| High Epistasis (Non-linear interactions) | Reduces predictability, disrupts building blocks | Association rules for dominant blocks; Higher-order epistasis models [12] [11] | Sparse epistatic hotspots can funnel the landscape toward the global optimum [11] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key computational and experimental "reagents" for analyzing and navigating complex fitness landscapes.

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Nearest-Better Network (NBN) | A visualization tool that constructs a graph from sampled solutions to reveal landscape characteristics like ruggedness and neutrality [10]. | General-purpose Fitness Landscape Analysis (FLA) for any black-box problem. |

| Improved Tent Map | A chaotic map used to generate a high-quality, diverse initial population for a genetic algorithm, improving global search capability [12]. | Initialization step in hybrid genetic algorithms for complex optimization. |

| Association Rule Theory | A data mining technique used to identify "dominant blocks" (superior gene combinations) in a population, reducing problem complexity [12]. | Feature selection and problem decomposition within genetic algorithms. |

| Specific Epistasis Model | A statistical model (including terms for pairwise ( J{ij} ) and third-order ( K{ijk} ) interactions) that quantifies genetic interactions in a complete fitness landscape [11]. | Analyzing empirical biological landscape data (e.g., from antibody libraries) to find interaction networks. |

| Yeast Surface Display | A high-throughput experimental system that links a protein phenotype (surface expression/stability) to its genotype (plasmid inside cell) for fitness sorting [11]. | Empirically measuring biological fitness landscapes, such as for antibody stability or binding. |

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting Guides

This technical support center provides targeted guidance for researchers optimizing Genetic Algorithms (GAs) in complex domains like code fitness landscapes. The FAQs below address common pitfalls and present methodologies to enhance experimental rigor.

FAQ 1: How do I choose a selection operator to control selection pressure and avoid premature convergence?

Thesis Context: In code fitness landscape research, maintaining genetic diversity is crucial for exploring disparate regions of the search space and avoiding convergence on suboptimal local minima.

Answer: The choice of selection operator directly regulates selection pressure—the emphasis on selecting the fittest individuals. High pressure can lead to premature convergence, while low pressure can stagnate the search [13] [14]. The table below summarizes key selection methods and their properties.

Table 1: Comparison of Common Parent Selection Schemes

| Selection Scheme | Mechanism | Advantages | Disadvantages | Best for Research Scenarios Involving... |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fitness Proportional (Roulette Wheel) [13] [14] | Selection probability is directly proportional to an individual's fitness. | Simple, provides a selection pressure towards fitter individuals. | High risk of premature convergence; performance degrades when fitness values are very close [13] [15]. | ...initial exploration phases where diverse, high-fitness building blocks need to be identified. |

| Rank Selection [13] [14] | Selection probability is based on an individual's rank within the population, not its raw fitness. | Maintains steady selection pressure even when fitness values converge; works with negative fitness. | Slower convergence as the difference between best and others is not significant [15]. | ...complex, noisy fitness landscapes where maintaining exploration pressure is critical. |

| Tournament Selection [13] [14] | Selects k individuals at random and chooses the best among them. |

Simple, efficient, tunable pressure via tournament size k, works with negative fitness. |

Can lead to loss of diversity if tournament size is too large. | ...large-scale populations and parallelized computations, as it's easily distributable [15]. |

| Stochastic Universal Sampling (SUS) [13] [14] | A single spin of a wheel with multiple, equally spaced pointers to select all parents. | Minimal spread and no bias; guarantees highly fit individuals are selected at least once. | Similar premature convergence risks as fitness proportionate selection. | ...ensuring a low-variance, representative selection of the current population's distribution. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Diagnosing Selection Pressure Issues

Symptom: Population diversity drops rapidly, and the algorithm converges to a suboptimal solution within a few generations.

- Investigation: Check if you are using Fitness Proportional Selection. Calculate the population's average fitness and the best fitness over time. A rapid plateau indicates high selection pressure.

- Solution: Switch to Rank Selection or reduce the tournament size in Tournament Selection to lower selection pressure [13] [15]. Introduce elitism to preserve the best solution without excessively increasing pressure [14] [16].

Symptom: The algorithm fails to converge, showing little improvement over many generations.

- Investigation: This suggests excessively low selection pressure.

- Solution: Increase the tournament size (

k) in Tournament Selection or adjust the scaling in Linear Rank Selection to increase the probability of selecting fitter individuals [14].

Experimental Protocol: Comparing Selection Operators To empirically determine the best selection operator for your code fitness landscape:

- Initialization: Define a fixed initial population for all experimental runs.

- Variable: Apply different selection operators (e.g., RWS, Rank, Tournament with k=2,5) while keeping all other parameters (crossover, mutation, population size) constant.

- Metrics: Track over multiple runs: (a) Mean best fitness per generation, (b) Generation at which convergence occurs, (c) Final population diversity (e.g., using entropy measures).

- Analysis: Use statistical tests (e.g., t-test) on the final results to determine if performance differences are significant [15].

FAQ 2: My crossover operations are producing invalid offspring, especially for permutation-based problems like scheduling. How can I fix this?

Thesis Context: In problems like test case scheduling or path planning, solutions are often represented as permutations (e.g., a sequence of test executions). Standard crossover can break permutation constraints, creating invalid offspring with duplicates or missing elements.

Answer: Standard one-point or two-point crossover is unsuitable for permutation representations. You require specially designed crossover operators that preserve the permutation property [17].

Table 2: Crossover Operators for Permutation Representations

| Crossover Operator | Mechanism | Research Reagent Solution Analogy | Ideal Problem Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Partially Mapped Crossover (PMX) [17] | Swaps a segment between two parents and uses mapping relationships to resolve conflicts and fill remaining genes. | A protocol for recombining two ordered lists of reagents without duplication. | Traveling Salesperson Problem (TSP), single-path optimizations. |

| Order Crossover (OX1) [17] | Copies a segment from one parent and fills the remaining positions with genes from the second parent in the order they appear, skipping duplicates. | A method for inheriting a core sequence from one protocol and filling preparatory steps from another. | Order-based scheduling where relative ordering is critical. |

| Cycle Crossover (CX) | Identifies cycles between parents and alternates them to form offspring. Preserves the absolute position of elements. | A technique for creating a new reagent setup by strictly alternating source racks from two parent setups. | Problems where the absolute position of a gene is highly correlated with fitness. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Crossover for Permutations

- Symptom: Offspring have duplicate genes or are missing required genes.

- Solution: Immediately switch from a binary or simple crossover to a permutation-aware operator like PMX or OX1 [17].

- Symptom: Crossover is breaking high-quality "building blocks" in the sequence.

- Solution: Experiment with different operators. OX1 is particularly noted for better preserving relative order, which can be crucial for scheduling workflows in drug development [17].

Visualization: Order Crossover (OX1) Workflow The following diagram illustrates the steps of the OX1 operator, designed to preserve relative order.

FAQ 3: What is the role of mutation, and how do I set an effective mutation rate to balance diversity and convergence?

Thesis Context: Mutation is a diversity-introducing operator that helps the population escape local optima in a rugged code fitness landscape and can restore lost genetic material.

Answer: Mutation acts as a background operator, making small, random changes to an individual's genes [18]. Its primary role is to ensure that every point in the search space is reachable and to preserve population diversity, thereby supporting the exploration of the fitness landscape [18]. The optimal mutation rate is a trade-off: too high and the search becomes a random walk; too low and the population loses genetic diversity, risking premature convergence.

Table 3: Common Mutation Operators by Representation

| Representation | Mutation Operator | Mechanism | Typical Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Binary [18] | Bit Flip | Each bit is flipped (0→1, 1→0) with a probability ( p_m ). | Low, often ( \frac{1}{l} ) where ( l ) is chromosome length [18]. |

| Real-Valued [18] | Gaussian Perturbation | A random number from a Gaussian distribution ( N(0, \sigma) ) is added to a gene value. | The step size ( \sigma ) is critical; often set as ( \frac{x{max} - x{min}}{6} ) [18]. |

| Permutation [18] | Swap / Inversion | Two genes are swapped, or a segment is inverted. | Can be higher than for binary, e.g., 1-5%. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Tuning Mutation

- Symptom: The population converges prematurely to a suboptimal solution.

- Investigation: Check if your mutation rate is too low. Monitor population diversity metrics.

- Solution: Gradually increase the mutation rate or implement adaptive mutation rates that increase when population diversity falls below a threshold.

- Symptom: The algorithm fails to converge and behaves erratically.

- Investigation: The mutation rate is likely too high, destroying good building blocks faster than selection can exploit them.

- Solution: Decrease the mutation rate. For real-valued genes, reduce the Gaussian step size ( \sigma ) [18].

FAQ 4: How should I design a fitness function for a multi-objective problem, such as optimizing both code coverage and execution time?

Thesis Context: Real-world problems in code optimization and drug development involve multiple, often conflicting, objectives. The fitness function must guide the search towards a set of optimal trade-off solutions.

Answer: There are two principal methodologies for handling multiple objectives:

Weighted Sum Approach: This method combines all objectives (oi) into a single scalar value using a weighted sum: ( f{raw} = \sum{i=1}^{O} oi \cdot w_i ). Constraints can be added as penalty functions that reduce the final fitness [19].

- Pros: Simple, computationally efficient.

- Cons: Requires a priori knowledge to set weights, and cannot find solutions in non-convex regions of the Pareto front [19].

Pareto Optimization: This approach selects individuals based on non-domination. A solution is Pareto-optimal if no objective can be improved without worsening another. The result is a set of solutions representing optimal trade-offs (the Pareto front) [19].

- Pros: Does not require weighting; provides a range of alternatives for a posteriori decision-making.

- Cons: Computationally more expensive; visualization becomes difficult with more than three objectives.

Visualization: Pareto Front for a Two-Objective Problem This diagram illustrates the concept of Pareto optimality in a minimization problem with two objectives (e.g., minimizing execution time and maximizing code coverage).

Experimental Protocol: Weighted Sum vs. Pareto Optimization

- Problem: Define your multi-objective problem (e.g., Minimize Execution Time, Maximize Code Coverage).

- Setup A (Weighted Sum): Run the GA multiple times with different weight vectors ( (w{time}, w{coverage}) ). Normalize objectives if necessary.

- Setup B (Pareto): Use a multi-objective GA (e.g., NSGA-II [19]) to find an approximation of the Pareto front in a single run.

- Evaluation: Compare the diversity and coverage of the solution sets obtained by both methods. The Pareto-based method should provide a more complete view of the available trade-offs, especially if the true Pareto front is non-convex [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents for GA Experiments

Table 4: Key Components for a GA Experimental Setup

| Research Reagent | Function & Explanation | Considerations for Code Fitness Landscapes |

|---|---|---|

| Population Initializer | Generates the initial set of candidate solutions. | Use heuristic initialization to seed the population with known good code snippets to bootstrap search. |

| Fitness Function | The objective function quantifying solution quality. | Ensure it is computationally efficient; consider fitness approximation for complex code simulations [19]. |

| Selection Operator | Algorithm for choosing parents based on fitness. | Tournament selection is often recommended for its tunable pressure and efficiency [13] [15]. |

| Crossover Operator | Recombines genetic material from two parents. | The choice is highly dependent on solution encoding (binary, real-valued, permutation) [17] [20]. |

| Mutation Operator | Introduces small random changes to maintain diversity. | Serves as a safeguard against premature convergence and a tool for exploring new regions [18]. |

| Elitism Mechanism | Directly copies the best individual(s) to the next generation. | Guarantees monotonic improvement in the best fitness, which is often desirable in research reporting [14] [16]. |

| Termination Criterion | Defines when the algorithm stops (e.g., generations, fitness threshold, stall time). | Use a combination of maximum generations and a stall criterion (e.g., no improvement for N generations) [16]. |

Why GAs? Contrasting Their Population-Based, Derivative-Free Approach with Traditional Optimization Methods

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the fundamental difference between a Genetic Algorithm and a Traditional Algorithm? The core difference lies in their problem-solving approach. Traditional algorithms are typically deterministic and follow a fixed set of logical steps to arrive at a single, definitive solution. In contrast, Genetic Algorithms (GAs) are stochastic and population-based, mimicking natural evolution by maintaining a pool of candidate solutions that evolve over generations through selection, crossover, and mutation to find an optimal or near-optimal solution [21] [22].

2. When should I use a Genetic Algorithm over a gradient-based method? GAs are particularly advantageous when [22] [3] [21]:

- The problem space is complex, rugged, and has multiple local optima.

- The objective function is discontinuous, non-differentiable, or "noisy."

- You need to explore a vast and poorly understood search space.

- Gradient information is unavailable or difficult to compute.

3. What are the common pitfalls when a Genetic Algorithm fails to converge? Common issues include premature convergence (where the population loses diversity too early and gets stuck in a local optimum), poor parameter tuning (e.g., inappropriate mutation or crossover rates), and an inadequately defined fitness function that does not effectively guide the search [9].

4. How are GAs applied in real-world scientific research, such as drug discovery? In drug discovery, GAs and other AI-driven optimization techniques are used for tasks like generative molecule design, where they help explore the vast chemical space to propose novel drug candidates optimized for specific properties (e.g., potency, selectivity). They are part of a broader toolkit that accelerates early-stage research and development [23] [24].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Issue | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Premature Convergence | Population diversity has been lost; the algorithm is trapped in a local optimum. | Increase the mutation rate [9], use fitness sharing techniques, or implement elitism to preserve the best individuals without dominating the gene pool [9]. |

| Slow Convergence | The search is not efficiently exploiting promising regions of the solution space. | Adjust the selection pressure to favor fitter individuals more strongly and fine-tune the crossover probability [9]. |

| Poor Final Solution Quality | The fitness function may not accurately represent the problem's true objectives. The algorithm may have stopped too early. | Re-evaluate and refine the fitness function. Run the algorithm for more generations and ensure the termination condition is appropriate [9]. |

Operational Comparison: Genetic Algorithms vs. Traditional Methods

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of different optimization algorithms, highlighting the unique position of GAs.

| Feature | Genetic Algorithms | Gradient Descent | Simulated Annealing | Particle Swarm Optimization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nature | Population-based, Stochastic [22] | Single-solution, Deterministic [22] | Single-solution, Probabilistic [22] | Population-based, Stochastic [22] |

| Uses Derivatives | No [22] | Yes [22] | No [22] | No [22] |

| Handles Local Minima | Yes [22] | No [22] | Yes [22] | Yes [22] |

| Best Suited For | Complex, rugged, non-differentiable search spaces [22] | Smooth, convex, differentiable functions [22] | Problems with many local optima [22] | Continuous optimization problems [22] |

The Genetic Algorithm Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the iterative process of a standard Genetic Algorithm, from population initialization to termination.

Genetic Algorithm Iterative Process

The Researcher's Toolkit: Key Components of a GA Experiment

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Chromosome/Individual | Represents a single candidate solution to the optimization problem, often encoded as a string (e.g., binary, integer, real-valued) [9]. |

| Population | The set of all chromosomes (candidate solutions) evaluated in a single generation [9]. |

| Fitness Function | A problem-specific function that assigns a score to each chromosome, quantifying its quality as a solution. This drives the selection process [9]. |

| Selection Operator | The process of choosing fitter individuals from the current population to become parents for the next generation (e.g., tournament selection, roulette wheel) [9]. |

| Crossover Operator | A genetic operator that combines the genetic information of two parents to generate new offspring, promoting the exploitation of good genetic traits [9]. |

| Mutation Operator | A genetic operator that introduces small random changes in an individual's chromosome, helping to maintain population diversity and explore new areas of the search space [9]. |

Methodological Advances and Cutting-Edge Applications in Biomedicine

Frequently Asked Questions

What are MGGX and MRRX, and how do they differ from traditional crossover operators? MGGX (Mixture-based Gumbel Crossover) and MRRX (Mixture-based Rayleigh Crossover) are novel parent-centric real-coded crossover operators designed for genetic algorithms (GAs). They leverage mixture probability distributions to dynamically balance exploration and exploitation during the search process. Unlike conventional operators like Simulated Binary Crossover (SBX), Laplace Crossover (LX), or double Pareto Crossover (DPX), which often struggle with premature convergence and population diversity, MGGX and MRRX are specifically engineered to adapt to complex, multimodal optimization landscapes [25] [26].

In which scenarios do MGGX and MRRX perform particularly well? These operators demonstrate superior performance in tackling high-dimensional, complex global optimization problems, including both constrained and unconstrained benchmark functions. Empirical studies confirm that MGGX excels in scenarios with multiple local optima, often achieving the lowest mean and standard deviation values in solution quality compared to traditional methods [25] [27] [26].

My GA is converging prematurely. How can MGGX/MRRX help? Premature convergence is often a result of poor balance between exploration and exploitation. The MGGX and MRRX operators are theoretically designed to adapt dynamically, reducing the risk of premature convergence by ensuring efficient exploration of complex search spaces. By leveraging the properties of mixture distributions, they enable the generation of diverse, high-quality offspring, thereby maintaining population diversity for longer durations [25] [26].

What are the key parameters I need to configure for MGGX? The MGGX operator is based on a two-component mixture model of the Gumbel distribution. Key parameters include the mixture coefficients (γ₁, γ₂), where γ₁ > 0, γ₂ < 1, and γ₁ + γ₂ = 1, as well as the location (μ) and scale (η) parameters for each component distribution. Proper configuration of these parameters is crucial for controlling the shape of the distribution and, consequently, the offspring generation behavior [25].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Algorithm Performance on Multimodal Problems

Problem Description The Genetic Algorithm is getting trapped in local optima when solving complex, multimodal optimization problems, leading to suboptimal solutions.

Diagnosis and Solution This is a classic symptom of an operator failing to maintain adequate exploration. The recently proposed MGGX operator has been empirically validated to address this exact issue.

- Recommended Action: Implement the Mixture-based Gumbel Crossover (MGGX).

- Implementation Protocol:

- Offspring Generation: For two parent vectors, ( w^{(1)} ) and ( w^{(2)} ), generate two offspring, ( \delta ) and ( \zeta ), for each variable ( i ) using the following equations [25]: [ \deltai = \frac{(wi^{(1)} + wi^{(2)}) + \betai |wi^{(1)} - wi^{(2)}|}{2} ] [ \zetai = \frac{(wi^{(1)} + wi^{(2)}) - \betai |wi^{(1)} - wi^{(2)}|}{2} ]

- Beta (β) Calculation: The key innovation lies in how ( \betai ) is derived. For MGGX, it is generated by inverting the cumulative distribution function (CDF) of a two-component mixture of Gumbel distributions [25]. The CDF for this mixture is: [ F(p) = \gamma1 F(p1) + \gamma2 F(p2) ] where ( F(pk) = e^{-e^{-(p-\muk)/\etak}} ) is the CDF of the Gumbel distribution for component ( k ).

- Parameter Settings: Initial studies have used this operator within a GA framework tested on standard benchmarks like CEC 2017 and CEC 2014. Start with similar population sizes and generation counts as used in those studies for a comparative baseline [26].

Performance Validation The table below summarizes the superior performance of MGGX compared to established operators across 36 test cases [25] [26]:

| Performance Metric | Simulated Binary Crossover (SBX) | Laplace Crossover (LX) | Mixture-based Gumbel Xover (MGGX) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Best Mean Value (Count) | Not Specified | Not Specified | 20 / 36 cases |

| Best Std Deviation (Count) | Not Specified | Not Specified | 21 / 36 cases |

| Multi-criteria TOPSIS Rank | Lower | Lower | 1st |

Issue 2: Maintaining Population Diversity

Problem Description Loss of population diversity leads to stagnation and prevents the discovery of better regions in the fitness landscape.

Diagnosis and Solution While crossover operators like MGGX and MRRX aid diversity, a holistic approach using multiple mutation operators is recommended to effectively search new spaces.

- Recommended Action: Augment your GA with specialized mutation operators.

- Implementation Protocol: The following mutation operators can be used in conjunction with MGGX/MRRX [25] [26]:

- Non-Uniform Mutation (NUM): Progressively decreases the magnitude of mutation as generations increase, favoring finer tuning later in the search.

- Power Mutation (PM): Based on the power distribution, it helps in creating offspring in the vicinity of the parent.

- MPTM Mutation: Effective for solving multidisciplinary optimization problems.

Issue 3: Selecting an Operator for a New Problem

Problem Description Uncertainty in choosing the most appropriate real-coded crossover operator for a previously untested optimization problem.

Diagnosis and Solution When no prior knowledge exists, empirical evidence suggests starting with the most robust and high-performing operator.

- Recommended Action: Adopt MGGX as the primary crossover operator.

- Implementation Protocol:

- Begin your experimental setup with the MGGX operator, as it has demonstrated top-tier robustness and scalability in independent tests [25] [26].

- Use the Performance Index (PI) and multi-criteria TOPSIS methodology, as employed in the foundational studies, to quantitatively evaluate and compare its performance against alternatives on your specific problem [25] [27].

- Analyze the fitness landscape of your problem if possible. Understanding features like modality can provide insight into why a particular operator performs well [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below lists key components for replicating and advancing research in real-coded genetic algorithms.

| Research Reagent / Component | Function in the Experimental Setup |

|---|---|

| MGGX / MRRX Operator | Core innovation for offspring generation; enhances exploration/exploitation balance in complex search spaces [25] [26]. |

| Benchmark Suites (CEC 2013, 2014, 2017) | Standardized set of constrained and unconstrained functions for empirical validation and fair comparison of algorithm performance [26]. |

| Mutation Operators (NUM, PM, MPTM) | Used in conjunction with crossover to introduce randomness and maintain population diversity, preventing premature convergence [25] [26]. |

| Statistical Tests (Quade Test) | Non-parametric statistical test used to detect significant differences in performance across multiple operators and benchmarks [25] [26]. |

| Multi-criteria Decision Making (TOPSIS) | Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution; ranks algorithms based on multiple performance criteria [25] [27] [26]. |

| Performance Index (PI) | A quantitative metric to evaluate and rank the overall efficiency and robustness of optimization algorithms [25]. |

Experimental Protocol and Workflow

The following diagram visualizes a standard experimental workflow for evaluating a new crossover operator like MGGX within a genetic algorithm, from problem selection to final ranking.

Operator Selection Logic

For researchers designing an adaptive algorithm, the decision process for selecting a crossover operator based on past performance can be conceptualized as follows.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between a de novo design run and a lead optimization run in AutoGrow4?

The core difference lies in the starting compounds. For de novo drug design, you begin with a set of small, chemically diverse molecular fragments to generate entirely novel compounds [29] [30]. For lead optimization, you start with known ligands or preexisting inhibitors and use AutoGrow4 to evolve them into better binders [29] [30]. In practice, this is controlled by the source_compound_file parameter; for a true de novo run, this file should not contain any known inhibitors or their fragments [31].

Q2: What are the recommended parameters for a de novo design run?

Based on the parameters used for the published PARP-1 de novo run, a robust starting point is as follows [31]:

| Parameter | Recommended Value for De Novo Run |

|---|---|

source_compound_file |

A file with small molecular fragments (e.g., Fragment_MW_100_to_150.smi) |

use_docked_source_compounds |

true |

number_of_mutants_first_generation |

500 |

number_of_crossovers_first_generation |

500 |

number_of_mutants |

2500 |

number_of_crossovers |

2500 |

number_elitism_advance_from_previous_gen |

500 |

num_generations |

30 |

rxn_library |

all_rxns |

LipinskiStrictFilter |

true |

GhoseFilter |

true |

Q3: The run fails with an error: "There were no available ligands in previous generation ranked ligand file." What should I check?

This error often indicates a problem in the initial stages of the run. Focus your troubleshooting on these areas:

- Receptor PDB File: Ensure your receptor PDB file is properly formatted and complete [32].

- Ligand PDB Conversion: Check the log files for errors during the conversion of ligand SMILES to 3D PDB format. The error log may contain messages like "Failed to convert..." which point to issues in generating 3D coordinates for your source compounds [32].

- Source Compounds: Verify that the file specified in

source_compound_fileexists and is correctly formatted.

Troubleshooting Guide

Issue: Failure in Ligand File Conversion (PDB to PDBQT)

Symptoms:

- Run terminates with the error: "There were no available ligands in previous generation ranked ligand file" [32].

- Log files show repeated "Failed to convert" messages for ligand PDB files during the PDB to PDBQT conversion step [32].

Diagnosis and Resolution:

- Inspect the Receptor: The first step is to validate the structure of your target protein file. Use a molecular visualization tool to check that the provided receptor PDB file is not corrupted and is structurally sound [32].

- Check the Output Directories: Look in the

Run_1/generation_0/PDBs/directory (or your corresponding output path) for any generated ligand PDB files. If they are missing or have a file size of 0 bytes, the failure occurred in an earlier step when Gypsum-DL converted SMILES to 3D PDBs [32]. - Verify Source Compounds: Confirm that the small molecules or fragments in your

source_compound_fileare valid and can be parsed by RDKit, which is used internally by AutoGrow4 for chemical operations [29] [30].

Experimental Protocol: De Novo Design for a Novel Target

This protocol outlines the steps to perform a de novo drug design campaign using AutoGrow4, using the PARP-1 case study as a template.

Materials and Setup

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Target Protein Structure | A prepared PDB file of the target's binding pocket (e.g., 4r6eA_PARP1_prepared.pdb for PARP-1). Must be pre-processed (e.g., adding hydrogens, assigning charges). |

| Source Compound File | An SMI file containing small molecular fragments (e.g., Fragment_MW_100_to_150.smi). This is the building block library for the de novo run. |

| Complementary Fragment Libraries | Pre-built libraries of small molecules (MW < 250 Da) that serve as reactants during the mutation operation. These are included with AutoGrow4. |

Reaction Library (rxn_library) |

A set of SMARTS-based reaction rules (e.g., all_rxns, robust_rxns) that define chemically feasible ways to mutate and grow molecules. |

| Docking Program | Software like QuickVina 2 or Vina used to predict the binding affinity (fitness) of generated ligands. |

| Molecular Filter Set | A series of filters (e.g., LipinskiStrictFilter, PAINSFilter) applied to remove undesirable compounds before docking, saving computational resources. |

Methodology

Step 1: Define the Binding Site

The binding site is defined by a 3D search space box within the target protein. Use the center_x, center_y, center_z and size_x, size_y, size_z parameters. For the PARP-1 example, the center was at (-70.76, 21.82, 28.33) with sizes of (25.0, 16.0, 25.0) Å [31].

Step 2: Configure the Genetic Algorithm Parameters Create a parameter file or command-line call based on the values in the table in FAQ #2. Key parameters control the population size per generation, the number of elitism, mutation, and crossover operations, and the total number of evolutionary generations [31].

Step 3: Execute AutoGrow4 Run AutoGrow4 with your configured parameters. The algorithm follows the workflow below to evolve compounds [29] [30]:

Step 4: Analysis of Results After the run completes, analyze the output files. The top-ranked compounds from the final generation are the primary candidates. Inspect their:

- Predicted Binding Affinity: Docking score (e.g., from Vina).

- Binding Poses: Superimpose generated ligands with known inhibitors to see if they mimic key interactions.

- Drug-likeness: Properties calculated by the applied filters.

- Lineage: Trace the evolutionary history of promising candidates through their file names to understand which fragments and reactions led to high fitness.

Experimental Protocol: Lead Optimization

This protocol describes how to use AutoGrow4 to optimize an existing lead compound.

Key Modifications from De Novo Protocol:

- Source Compounds: The

source_compound_fileshould now contain the SMILES of one or more known lead compounds or inhibitors, rather than small fragments [29]. - Parameters: You may use a smaller population size for mutations and crossovers, as the algorithm is refining a starting point rather than exploring a vast chemical space from scratch.

The overall workflow remains the same as the diagram above, but Generation 0 starts with your known lead molecules instead of random fragments.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Components in the Fitness Landscape

In the context of optimizing genetic algorithms, each component of AutoGrow4 contributes to defining and navigating the fitness landscape.

| Component | Role in the Genetic Algorithm Fitness Landscape |

|---|---|

| Docking Score (Vina) | Serves as the primary fitness function. It defines the "height" in the landscape, guiding the selection towards regions of higher predicted binding affinity [29] [33]. |

| Mutation Operator | Introduces local search and diversity. By applying chemical reactions, it explores nearby points in the chemical space, helping to escape local optima [29] [30]. |

| Crossover Operator | Enables recombination. It combines traits from two fit parents, potentially discovering new, high-fitness regions of the chemical space that are a blend of existing solutions [29] [30]. |

| Molecular Filters (e.g., PAINS) | Act as constraints on the search space. They prune away regions of the chemical space that correspond to undesirable compounds, making the search more efficient and biologically relevant [29] [30]. |

| Elitism Operator | Implements steady-state selection. It guarantees that the best solutions found are not lost between generations, ensuring monotonic improvement in the top fitness value [29] [30]. |

Technical Support Center: FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core principle behind using network controllability for cancer therapy? The core principle is that a cancer cell's signaling network can be modeled as a dynamic system. By identifying a minimal set of proteins (driver nodes) that need to be targeted to steer the entire network from a diseased state to a healthy state, therapies can be designed to be more effective and less toxic. This approach moves beyond targeting individual genes and instead focuses on controlling the system's overall behavior [34] [35].

Q2: Why are Genetic Algorithms (GAs) well-suited for optimizing drug combinations in this context? GAs are ideal for this multi-objective optimization problem because they can efficiently search a vast and complex solution space. They do not require derivative information and are effective at avoiding local optima, which is common when dealing with the nonlinear and high-dimensional fitness landscapes of biological networks. A GA can be used to find a combination of drugs that maximizes cancer cell death while minimizing damage to healthy tissue and control energy [36] [37].

Q3: What does "control energy" mean, and why is it a critical parameter? Control energy refers to the theoretical effort required to steer a network from one state to another. In a practical sense, it can relate to the dosage or potency of a drug required to achieve a therapeutic effect. Networks that require lower control energy are generally more controllable. The placement of input nodes (drug targets) directly impacts this energy, and a key goal is to find target sets that minimize it [35] [38].

Q4: Our GA is converging too quickly to a suboptimal solution. What could be the issue? Premature convergence is often a result of a lack of diversity in the population. This can be addressed by:

- Adjusting GA parameters: Increase the mutation rate or use tournament selection to maintain genetic diversity.

- Re-evaluating the fitness function: The fitness landscape might be deceptive. Incorporating multiple, conflicting objectives (e.g., control energy, number of targets, therapeutic effect) can create a more complex and informative landscape for the GA to navigate [37].

- Using Niching Techniques: Implement methods like fitness sharing to promote solutions in different regions of the search space.

Q5: How can we validate the predictions from our computational model? Computational predictions must be validated through in vitro and in vivo experiments. Key steps include:

- Selecting Cell Lines: Use non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell lines for experimental validation based on the computational study [34].

- Measuring Viability: Treat cells with the proposed drug combination (e.g., Fostamatinib, Aducanumab, Aspirin) and measure cell kill rates using assays like MTT or colony formation.

- Assessing Network Perturbation: Use techniques like Western blotting or RNA sequencing to confirm that the drug combination alters the expression and activity of the predicted key nodes (e.g., ITGA2B, FLNA, SYK) [34].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: The proposed drug combination shows high efficacy but also high toxicity in initial simulations.

- Potential Cause: The fitness function is overly weighted towards cell kill rate, ignoring off-target effects.

- Solution: Reformulate the multi-objective fitness function to more heavily penalize predicted toxicity. The GA can then be re-run to find a Pareto-optimal solution that balances efficacy and safety [36].

Problem: The controllability analysis of the reconstructed TEP signaling network fails to identify a small set of driver nodes.

- Potential Cause: The network model may be missing critical interactions or contain false positives.

- Solution:

- Curate the Network: Integrate data from multiple, high-confidence protein-protein interaction databases.

- Check Network Connectivity: Ensure the network is structurally controllable. The minimum number of driver nodes can be determined using the maximum matching algorithm [35].

- Refine the Model: Incorporate edge weights based on gene expression or interaction confidence scores to create a more realistic model.

Problem: The computational model does not generalize to other cancer types.

- Potential Cause: The network model and gene expression data are too specific to NSCLC.

- Solution: Reconstruct cancer-type-specific signaling networks using transcriptomic data from other cancers (e.g., pancreatic, breast). The GA-based optimization framework can then be reapplied to these new networks to identify context-specific drug targets [34].

Detailed Methodologies for Key Experiments

Experiment 1: Reconstructing and Analyzing the Tumor-Educated Platelet (TEP) Signaling Network

- Data Acquisition: Obtain the gene expression dataset GSE89843 from the GEO database [34].

- Differential Expression Analysis: Identify Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) between NSCLC patient platelets and non-cancer controls using a statistical threshold (e.g., |log2FC| > 1, adjusted p-value < 0.05).

- Network Reconstruction: Integrate the DEGs with a directed protein-protein interaction network from the OmniPath database to build a TEP-specific signaling network [34].

- Topological & Controllability Analysis:

- Calculate standard network metrics (degree, betweenness centrality).

- Perform a structural controllability analysis to identify a set of driver nodes (proteins) that can steer the network. This involves finding a maximum matching of the network graph [35].

- Identification of High-Confidence Targets: Use multiple complementary strategies to pinpoint central, indispensable nodes. The study identified five high-confidence genes: ITGA2B, FLNA, GRB2, FCGR2A, and APP [34].

Experiment 2: Multi-Objective GA for Drug Combination Optimization

- Define Variables: The variables (genes) for the GA are the potential drug targets in the TEP network. A binary encoding is used, where 1 indicates the target is selected and 0 indicates it is not.

- Formulate Fitness Function: The fitness function is multi-objective. A sample function to be maximized could be:

Fitness = α * (Cell Kill Rate) - β * (Number of Targets) - γ * (Predicted Control Energy)where α, β, and γ are weights determined by the researcher to balance the objectives [36]. - GA Optimization Process:

- Initialization: Generate a random population of candidate drug combinations.

- Evaluation: Calculate the fitness for each candidate.

- Selection: Select parents for reproduction using a method like roulette wheel or tournament selection.

- Crossover & Mutation: Create offspring by combining parts of parent solutions and introducing random changes.

- Termination: Repeat for a set number of generations or until convergence. The output is a set of non-dominated solutions (Pareto front) representing optimal trade-offs [36] [39].

Visualization of Workflows and Pathways

GA for Drug Repurposing Workflow

Key TEP Signaling Pathway

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Materials for Computational and Experimental Validation

| Item Name | Function / Description | Application in the Case Study |

|---|---|---|

| GEO Dataset GSE89843 | A gene expression dataset for Tumor-Educated Platelets. | Used to identify differentially expressed genes and reconstruct the TEP-specific signaling network [34]. |

| OmniPath Database | A comprehensive database of literature-curated protein-protein interactions. | Provides the directed network structure for integrating with DEGs to build the signaling network [34]. |

| Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) Cell Lines | In vitro models of lung cancer (e.g., A549, H460). | Used for experimental validation of predicted drug efficacy and network perturbation [34]. |

| Fostamatinib | An FDA-approved SYK inhibitor. | Top candidate drug identified to disrupt ITAM-mediated platelet activation in the TEP network [34]. |

| Acetylsalicylic Acid (Aspirin) | A common COX-1 inhibitor. | Part of the proposed low-dose combination therapy to control TEP effects and reduce metastasis [34]. |

| Aducanumab | An FDA-approved antibody targeting APP (Amyloid Beta Precursor Protein). | Identified as a candidate drug to target the central node APP in the TEP network [34]. |

Table 2: High-Confidence Target Genes Identified in the TEP Network [34]

| Gene Symbol | Function / Pathway Association | Rationale as a Target |

|---|---|---|

| ITGA2B | Platelet activation, integrin signaling, cell adhesion. | Central to pro-adhesive and ECM-remodeling activities of TEPs. |

| FLNA | Cytoskeleton organization, signal transduction. | Influences cell shape and migration; a key metastasis-promoting target. |

| GRB2 | Immune signaling, growth factor receptor binding. | A critical adaptor protein in multiple signaling cascades. |

| FCGR2A | Immune receptor, ITAM-mediated signaling. | Part of the FCGR2A/ITAM/SYK axis identified as a key control point. |

| APP | Amyloid Beta Precursor Protein, cell adhesion. | A central node in the network; can be targeted by Aducanumab. |

Table 3: Example Multi-Objective GA Parameters for Optimization

| Parameter | Suggested Setting | Notes / Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Population Size | 100 - 500 | Larger sizes help explore complex search spaces but increase computation time. |

| Number of Generations | 50 - 200 | Run until the Pareto front stabilizes. |

| Selection Method | Tournament Selection | Helps maintain selection pressure and population diversity. |

| Crossover Rate | 0.7 - 0.9 | Standard for binary-encoded problems. |

| Mutation Rate | 0.01 - 0.05 | Prevents premature convergence; can be adaptive. |

| Fitness Objectives | 1. Cell Kill Rate2. Number of Targets3. Control Energy | Weights (α, β, γ) must be tuned for the specific research goal [36]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why is accuracy a misleading metric for imbalanced biomedical datasets, and what should I use instead? Accuracy can be highly deceptive for imbalanced datasets because a model can achieve a high score by simply always predicting the majority class. For instance, on a dataset where only 6% of transactions are fraudulent, a model that always predicts "no fraud" would still be 94% accurate, but useless for detecting the critical minority class [40]. Instead, you should use a suite of metrics for a complete picture [41]:

- Confusion Matrix: Provides a summary of correct and incorrect predictions.

- Precision: Measures the exactness of positive predictions.

- Recall: Measures the ability to find all positive samples.

- F1-Score: The harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a single balanced metric.

FAQ 2: What are the fundamental data-level approaches to handling class imbalance? The two primary data-level approaches are oversampling and undersampling [40].

- Oversampling: This involves adding more copies of the minority class. It is a good choice when you don't have a large amount of data. A potential drawback is that it can cause overfitting if the copies are exact.

- Undersampling: This involves removing samples from the majority class. It is suitable when you have a vast amount of data (millions of rows). The main risk is that valuable information could be lost by discarding data.

FAQ 3: How do advanced synthetic data generation techniques like SMOTE and GANs improve upon basic resampling? While basic oversampling creates exact copies of minority samples, advanced techniques generate new, synthetic samples to improve diversity and model generalization [42].

- SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique): This algorithm creates synthetic data by interpolating between existing minority class instances. It works by randomly selecting a minority point, finding its k-nearest neighbors, and creating new points along the line segments joining them [40].

- GANs (Generative Adversarial Networks): Deep learning models like Deep-CTGAN can learn the complex, underlying distribution of the real data and generate entirely new, high-fidelity synthetic records. They are particularly powerful for capturing non-linear relationships in complex tabular data, such as electronic health records [42] [43].

FAQ 4: How can I validate that my synthetically generated data is high-quality and useful? Rigorous validation is essential and should be multi-layered [44]:

- Statistical Similarity: Compare distributions, correlations, and other key properties between real and synthetic datasets.

- Expert Clinical Review: Have domain experts perform blinded assessments to evaluate the realism of synthetic records or images.

- Quantitative Performance (TSTR): Use the "Train on Synthetic, Test on Real" method. A model trained on your synthetic data should perform well when tested on a held-out set of real data, confirming the synthetic data's utility [42].

- Privacy Checks: Ensure the synthetic data cannot be reverse-engineered to reveal real patient information, using metrics like resistance to membership inference attacks [44].

FAQ 5: My model trained with synthetic data is performing poorly on real-world test sets. What could be wrong? This is often a sign of a synthetic data fidelity issue or data leakage. Key troubleshooting steps include:

- Check for Data Leakage: Ensure you strictly split your real data into training and testing sets before generating any synthetic data. The synthetic data should only be generated based on the training set, and the test set must remain completely untouched and original to provide a unbiased evaluation [41].

- Assess Synthetic Data Fidelity: Use the validation methods above to ensure your synthetic data accurately captures the feature relationships and variance of the real training data. The model may be learning artificial patterns not present in the real world.

- Review the Generative Model: If using a complex model like a GAN, it may have suffered from mode collapse, where it fails to capture the full diversity of the real data. Techniques like adding an external memory mechanism or using a variational autoencoder (VAE) have been proposed to overcome this [43].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Model Bias Towards Majority Class After Training

Description The model shows high overall accuracy but fails to identify cases from the minority class, which is often the class of greatest interest (e.g., a rare disease).

Diagnostic Steps

- Generate a Classification Report: Check the precision, recall, and F1-score for the minority class. These will likely be very low despite high accuracy [41].

- Plot a Confusion Matrix: Visually confirm that the minority class (e.g., "Fraudulent" or "Diseased") has a high number of False Negatives [40].

- Verify Dataset Balance: Check the class distribution in your training data. A severe imbalance is the root cause.

Solution Apply a synthetic data generation technique to balance the training set.

- Step 1: Isolate the minority and majority classes in your training data.

Step 2: Use SMOTE to generate synthetic minority samples.

Step 3: Retrain your model on the resampled dataset and re-evaluate using the F1-score.

Problem: Loss of Information or Overfitting from Resampling

Description After resampling, the model's performance on the independent test set degrades. This can be due to:

- Undersampling: Removing too many critical samples from the majority class.

- Oversampling: Creating too many identical or very similar synthetic samples, causing the model to memorize noise.

Diagnostic Steps

- Compare Performance: Check if the model's training accuracy is significantly higher than its test accuracy, a classic sign of overfitting.

- Use Cross-Validation: Use stratified k-fold cross-validation on the resampled data to get a more robust performance estimate [41].

- Evaluate Data Quality: For undersampling, check if the remaining majority class is still representative. For oversampling, check the diversity of the synthetic samples.

Solution Use more sophisticated resampling techniques that promote diversity and preserve information.

- For Undersampling: Use Tomek Links to remove only ambiguous majority class samples, which are borderline cases close to minority samples, thereby improving class separation [40].

- For Oversampling: Use a Generative Model like Deep-CTGAN. This deep learning approach generates more diverse and realistic synthetic data by learning the complex probability distribution of the original data, reducing the risk of overfitting compared to simple interpolation methods [42].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Quantitative Performance of Synthetic Data Methods

The table below summarizes the testing accuracy achieved by a TabNet classifier when trained on synthetic data generated via a Deep-CTGAN + ResNet framework and tested on real data (TSTR) [42].

| Biomedical Dataset | Testing Accuracy (TSTR) | Similarity Score (Real vs. Synthetic) |

|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 | 99.2% | 84.25% |

| Kidney Disease | 99.4% | 87.35% |

| Dengue | 99.5% | 86.73% |

Comparison of Resampling Techniques

This table provides a high-level comparison of common techniques for handling class imbalance [42] [40].

| Technique | Category | Brief Description | Pros & Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Undersampling | Data Resampling | Randomly removes samples from the majority class. | Pro: Fast, reduces computational cost.Con: May discard useful information, potentially leading to worse model performance. |

| Random Oversampling | Data Resampling | Randomly duplicates samples from the minority class. | Pro: Simple to implement, no data loss.Con: Can cause overfitting by creating exact copies. |

| SMOTE | Synthetic Data | Generates synthetic minority samples by interpolating between existing ones. | Pro: Increases diversity of minority class.Con: Can generate noisy samples by ignoring the majority class. |

| Deep-CTGAN | Synthetic Data | A deep learning model that generates synthetic tabular data mimicking real distributions. | Pro: Captures complex, non-linear relationships; high fidelity.Con: Computationally intensive; requires expertise to implement. |

Detailed Methodology: Deep-CTGAN with ResNet for Tabular Data

This protocol is based on the framework that achieved the high performance results shown in the first table [42].

Objective: To generate high-fidelity synthetic tabular data for imbalanced biomedical datasets that can be used to train high-performance classifiers.

Workflow:

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing: Normalize numerical variables and encode categorical variables. It is critical to perform a stratified train-test split at this stage to preserve the original class imbalance in both sets. The test set is set aside and not used in the synthetic data generation process [41].