Optimizing Directed Evolution: Machine Learning, High-Throughput Strategies, and Protocol Automation for Accelerated Protein Engineering

Directed evolution is a cornerstone of modern protein engineering, yet its efficiency is often hampered by epistasis and vast sequence spaces.

Optimizing Directed Evolution: Machine Learning, High-Throughput Strategies, and Protocol Automation for Accelerated Protein Engineering

Abstract

Directed evolution is a cornerstone of modern protein engineering, yet its efficiency is often hampered by epistasis and vast sequence spaces. This article synthesizes the latest advancements in optimizing directed evolution protocols, with a focus on the integration of machine learning and automated systems. We explore foundational principles, detailing the challenges of non-additive mutation effects. We then examine cutting-edge methodological frameworks, including Active Learning-assisted Directed Evolution (ALDE) and deep learning-guided algorithms like DeepDE, which dramatically accelerate the engineering of enzymes and therapeutic proteins. The article provides a troubleshooting guide for common experimental bottlenecks and presents a comparative validation of emerging strategies against traditional methods. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review serves as a strategic guide for implementing next-generation directed evolution to develop novel biologics and biocatalysts.

The Foundations of Directed Evolution and Modern Challenges

Directed evolution is a powerful protein engineering methodology that mimics the process of natural selection in a laboratory setting to optimize proteins for human-defined applications. This iterative process systematically explores vast protein sequence spaces to discover variants with improved properties, such as enhanced stability, novel catalytic activity, or altered substrate specificity, without requiring detailed a priori knowledge of the protein's structure [1]. The profound impact of this approach was recognized with the 2018 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, awarded to Frances H. Arnold for establishing directed evolution as a cornerstone of modern biotechnology [1].

The Core Iterative Cycle

The directed evolution workflow functions as a two-part iterative engine, compressing geological timescales of natural evolution into weeks or months by intentionally accelerating mutation rates and applying user-defined selection pressures [1]. A single round of laboratory evolution comprises three essential steps [2]:

- Generation of Diversity: Creating a library of gene variants through random mutagenesis and/or DNA recombination of parental genes.

- Library Expression: Cloning and functional expression of the mutant library in a suitable host system.

- Screening or Selection: Identifying variants exhibiting the desired improved feature from the library.

The best-performing variants identified in one round become the templates for the next round of diversification and selection, allowing beneficial mutations to accumulate over successive generations until the desired performance level is achieved [3] [1]. A critical distinction from natural evolution is that the selection pressure is decoupled from organismal fitness; the sole objective is the optimization of a single, specific protein property defined by the experimenter [1].

Key Methodologies for Library Generation

The creation of a diverse gene variant library defines the boundaries of explorable sequence space. The choice of diversification strategy is a critical decision that shapes the entire evolutionary search [1].

Table 1: Common Methods for Generating Genetic Diversity in Directed Evolution

| Method | Principle | Advantages | Disadvantages | Typical Mutation Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Error-Prone PCR (epPCR) | Modified PCR using low-fidelity polymerases and biased nucleotide concentrations to introduce random point mutations [3] [1]. | Easy to perform; does not require prior structural knowledge [4]. | Biased mutation spectrum (favors transitions); limited amino acid substitution range (5-6 of 19 possible) [1]. | 1-5 base mutations/kb [1]. |

| DNA Shuffling | Homologous genes are fragmented with DNase I and reassembled in a primerless PCR, causing crossovers [3] [1]. | Recombines beneficial mutations; mimics natural recombination [3]. | Requires high sequence homology (>70-75%); crossovers biased to regions of high identity [1]. | N/A |

| Site-Saturation Mutagenesis | Targeted mutagenesis where a specific codon is replaced to encode all 20 amino acids [1]. | Comprehensive exploration of specific "hotspot" residues; creates smaller, higher-quality libraries [4] [1]. | Requires prior knowledge (e.g., from structure or initial epPCR rounds) [4]. | N/A |

| In Vivo Mutagenesis (e.g., EvolvR, MutaT7) | Uses specialized systems within host cells to continuously introduce targeted mutations into a gene of interest [5]. | Enables continuous evolution; reduces hands-on labor [5]. | May require specialized strains or plasmids; mutation spectrum can be system-dependent [5]. | Varies by system |

Troubleshooting Common Directed Evolution Challenges

FAQ: Overcoming Experimental Hurdles

Q1: My library yields are consistently low. What are the primary causes and solutions?

Low library yield is a common issue often traced to problems with sample input, fragmentation, or amplification [6].

- Cause: Poor input quality or contaminants (e.g., residual phenol, salts) inhibiting enzymatic reactions [6].

- Solution: Re-purify the input DNA/RNA, ensure wash buffers are fresh, and verify purity via spectrophotometry (260/230 > 1.8, 260/280 ~1.8) [6]. Use fluorometric quantification (Qubit) over UV absorbance for accurate concentration measurement [6].

- Cause: Inefficient adapter ligation during library prep due to suboptimal molar ratios or poor ligase performance [6].

- Solution: Titrate the adapter-to-insert molar ratio, ensure fresh ligase and buffer, and maintain optimal reaction temperature [6].

Q2: My directed evolution campaign has stalled at a local optimum. How can I escape?

Getting trapped by a variant that is good but not the best is a classic problem on "rugged" fitness landscapes [7] [5].

- Solution: Incorporate recombination-based methods like DNA shuffling to combine mutations from several moderately improved variants, which can lead to synergistic effects and open new evolutionary paths [3] [1].

- Solution: Adjust your selection strategy. Instead of only taking the top-performing variants, consider maintaining more diverse sub-populations or using probabilistic selection functions to better explore the sequence space and avoid local traps [5].

- Solution: Integrate machine learning. Active Learning-assisted Directed Evolution (ALDE) uses model predictions to prioritize variants that are not just high-performing but also informative, guiding the search more efficiently through epistatic regions [7].

Q3: How do I choose between random and targeted mutagenesis strategies?

A combined, sequential approach is often most robust [1].

- Initial Rounds: Start with random mutagenesis (epPCR) to broadly explore the fitness landscape and identify potential "hotspot" regions without structural bias [1].

- Intermediate Rounds: Use DNA shuffling to recombine beneficial mutations identified in the initial rounds, potentially revealing additive or synergistic effects [3] [1].

- Later Rounds: Employ site-saturation mutagenesis to exhaustively explore the key hotspots, fine-tuning the most promising regions of the protein [1]. This semi-rational approach increases efficiency by focusing resources on smaller, higher-quality libraries.

Advanced Techniques: Machine Learning Integration

Machine learning (ML) is rapidly advancing directed evolution by helping to navigate complex fitness landscapes where mutations have non-additive (epistatic) effects [7].

Active Learning-assisted Directed Evolution (ALDE) is an iterative ML-assisted workflow that leverages uncertainty quantification to explore protein sequence space more efficiently [7]. In a recent application, ALDE was used to optimize five epistatic active-site residues in a protoglobin for a non-native cyclopropanation reaction. In just three rounds, it improved the product yield from 12% to 93%, successfully identifying a optimal variant that standard single-mutation screening followed by recombination failed to find [7].

DeepDE is another deep learning-guided algorithm that uses triple mutants as building blocks, allowing exploration of a much larger sequence space per iteration. When applied to GFP, DeepDE achieved a 74.3-fold increase in activity over four rounds, surpassing the benchmark "superfolder" GFP [8]. A key to its success was training the model on a manageable library of ~1,000 mutants, mitigating data sparsity issues common in protein engineering [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Directed Evolution

| Item | Function in Directed Evolution | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Low-Fidelity DNA Polymerases | Catalyzes error-prone PCR to introduce random mutations across the gene [1]. | Taq polymerase (lacks proofreading), Mutazyme II series [1]. |

| DNase I | Randomly fragments genes for DNA shuffling protocols [3] [1]. | Used to create small fragments (100-300 bp) for recombination [3]. |

| NNK Degenerate Codon Primers | For site-saturation mutagenesis; NNK codes for all 20 amino acids and one stop codon [7]. | Allows comprehensive exploration of a single residue; superior to NNN which encodes multiple stop codons [7]. |

| Specialized Host Strains | For in vivo cloning, expression, and in some cases, mutagenesis. | E. coli BL21(DE3) for expression; S. cerevisiae for secretory expression and high recombination; specialized strains for EvolvR or MutaT7 systems [9] [5]. |

| Fluorometric Assay Kits | For high-throughput screening of enzyme activity using fluorescent substrates in microtiter plates [1]. | Enables screening of thousands of variants; requires a substrate that yields a fluorescent product. |

| Microfluidic Sorting Devices | For ultra-high-throughput screening and selection based on fluorescent or dynamic phenotypic signals [5]. | FACS (Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting) and newer devices allowing temporal monitoring of cells [5]. |

FAQs: Understanding Epistasis and Rugged Fitness Landscapes

Q1: What is a rugged fitness landscape, and why does it pose a problem for directed evolution?

A rugged fitness landscape is characterized by multiple peaks (high fitness variants) and valleys (low fitness variants), unlike a smooth landscape with a single, easily accessible peak. This ruggedness arises primarily from epistasis, where the effect of one mutation depends on the presence or absence of other mutations in the genetic background [10] [11]. This poses a significant challenge for directed evolution because it can trap evolutionary pathways in local fitness peaks, preventing the discovery of globally optimal variants. Furthermore, sign epistasis—where a mutation that is beneficial in one background becomes deleterious in another—drastically reduces the number of accessible mutational pathways to a high-fitness variant [11].

Q2: How can I experimentally detect if my protein's fitness landscape is rugged?

Detecting epistasis requires systematically measuring the fitness of not just individual mutants, but also their combinations. A robust method involves constructing and analyzing a combinatorial complete fitness landscape. This means generating all possible combinations (2^n) of a selected set of 'n' mutations and quantitatively assessing the fitness (e.g., enzymatic activity under selective pressure) of each variant [11]. The table below, based on a study of the BcII metallo-β-lactamase, shows how the effect of a mutation (e.g., G262S) can change depending on the genetic background, a clear indicator of epistasis [11].

Table 1: Example of Epistatic Interactions in a Metallo-β-lactamase (BcII)

| Variant | Relative Fitness (Cephalexin MIC) | Key Observation |

|---|---|---|

| Wild-Type | 1x | Baseline activity. |

| G262S (G) | ~5x | Mutation is beneficial in the wild-type background. |

| L250S (L) | ~3x | Mutation is beneficial in the wild-type background. |

| G262S + L250S (GL) | ~15x | Combined effect is greater than the sum of individual effects (positive epistasis). |

| G262S + N70S (GN) | ~2x | Combined effect is less than the sum of individual effects (negative epistasis). |

Q3: My directed evolution experiment is stalling, with no improvement in fitness over several rounds. Could epistasis be the cause?

Yes, this is a classic symptom of being trapped on a local fitness peak due to a rugged landscape. When all single-step mutations from your current best variant lead to a decrease in fitness (a phenomenon caused by sign epistasis), the adaptive walk cannot proceed further via random mutation and screening [11] [12]. To escape this local peak, you may need to employ strategies that allow for the exploration of "neutral" or even slightly deleterious mutations that can open paths to higher fitness peaks, such as recombination-based methods or leveraging ancestral sequence reconstructions to explore alternative historical paths [10].

Q4: How does machine learning help navigate rugged fitness landscapes?

Machine learning (ML) models can predict the fitness of unsampled protein sequences by learning from experimental data, effectively smoothing the perceived ruggedness of the landscape. By identifying complex, higher-order epistatic interactions within the data, ML can guide library design towards sequences with a high probability of being beneficial, reducing the experimental burden of screening vast mutant libraries [9] [12]. However, its effectiveness is currently limited by the need for large, high-quality training datasets and the poor predictability for mutations distant from the training set [9].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Failures

Table 2: Troubleshooting Directed Evolution Experiments

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions & Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Low or No Library Diversity | - Inefficient mutagenesis method (e.g., low mutation rate).- Host system with high recombination or low transformation efficiency. | - Use a combination of mutagenesis methods (e.g., SEP and DDS) for even mutation distribution [9].- Optimize host: S. cerevisiae for high recombination and complex proteins, E. coli for prokaryotic proteins [9]. |

| High Background or False Positives in Screening | - Selection pressure is too low.- "Parasite" variants that survive without the desired function. | - Use Design of Experiments (DoE) to optimize selection conditions (e.g., cofactor conc., time) [12].- Include stringent counterscreening and negative controls to identify and eliminate parasites [12]. |

| Stalled Fitness Improvement (Local Optima) | - Rugged fitness landscape with sign epistasis.- Limited exploration of sequence space. | - Use "landscape-aware" methods like DNA shuffling or SCHEMA recombination to explore new combinations [9].- Incorporate ML guidance to identify beneficial but non-obvious mutations [9] [12]. |

| Poor Protein Expression in Host | - Toxicity of the protein or DNA to the host.- Improper folding or lack of post-translational modifications. | - Switch to a more compatible host (e.g., P. pastoris for glycosylation, S. cerevisiae for secretion) [9].- Use lower growth temperatures or tighter promoter control to mitigate toxicity [13]. |

| Inefficient Transformation | - Low cell viability.- Toxic DNA construct.- Incorrect antibiotic or concentration. | - Transform an uncut plasmid to check competence [14].- Use a low-copy number plasmid or a strain with tighter transcriptional control for toxic genes [14] [13]. |

Experimental Protocols for Landscape Analysis

Protocol 1: Constructing a Combinatorial Fitness Landscape

This protocol is adapted from the study on metallo-β-lactamase BcII to map epistatic interactions between a small set of mutations [11].

1. Gene Library Construction:

- Site-Directed Mutagenesis: Start with your gene of interest containing the predefined set of 'n' point mutations (e.g., N70S, V112A, L250S, G262S). Use sequential rounds of site-directed mutagenesis to generate all 2^4 = 16 possible combinations of these mutations.

- Cloning: Clone each variant into an appropriate expression vector. Ensure the vector is compatible with your downstream host and selection system (e.g., antibiotic resistance).

2. High-Throughput Fitness Assay:

- Selection System: Establish a quantitative fitness metric. For the lactamase study, fitness was defined as the Minimal Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) of cephalexin, which directly correlates with enzyme activity in a cellular context [11].

- Activity Measurement: For each variant, measure the selected fitness parameter (e.g., MIC, growth rate, fluorescence output) in a high-throughput format. It is critical to perform assays in conditions that mimic the native environment (e.g., in periplasmic extracts, not just with purified enzyme) to capture pleiotropic effects [11].

3. Data Analysis and Epistasis Calculation:

- Calculate Epistasis: Quantify epistasis (ε) for a pair of mutations (i and j) using the formula: ε = Fij - Fi - Fj + Fwt where F is the measured fitness of the double mutant (ij), single mutants (i, j), and the wild-type (wt). A value of ε = 0 indicates no epistasis; ε > 0 indicates positive epistasis; ε < 0 indicates negative epistasis.

- Identify Sign Epistasis: Sign epistasis occurs if a mutation is beneficial in one background (Fi > Fwt) but deleterious in another (Fij < Fj).

Protocol 2: Optimizing Selection Parameters using Design of Experiments (DoE)

This protocol, based on polymerase engineering, uses DoE to efficiently optimize selection conditions for a directed evolution campaign, maximizing the signal-to-noise ratio [12].

1. Library and Factor Selection:

- Prepare a Focused Library: Construct a small, defined mutant library targeting a key functional residue (e.g., a catalytic site) [12].

- Define Factors and Ranges: Select key selection parameters ("factors") to optimize (e.g., Mg²⁺ concentration, Mn²⁺ concentration, substrate concentration, incubation time). Define a realistic range for each factor.

2. Experimental Setup and Screening:

- Run DoE Matrix: Subject the focused library to selection under all the conditions defined by your experimental design (e.g., a full factorial design).

- Analyze Outputs: For each selection output, measure key "responses" such as recovery yield (total DNA output), variant enrichment (diversity of surviving variants), and variant fidelity (accuracy of the selected function) [12].

3. Analysis and Parameter Validation:

- Identify Optimal Conditions: Use statistical analysis to determine which factor settings produce the most desirable responses (e.g., high recovery of diverse, high-fidelity variants).

- Validate: Apply the optimized selection parameters to a larger, more complex mutant library for your full-scale directed evolution experiment.

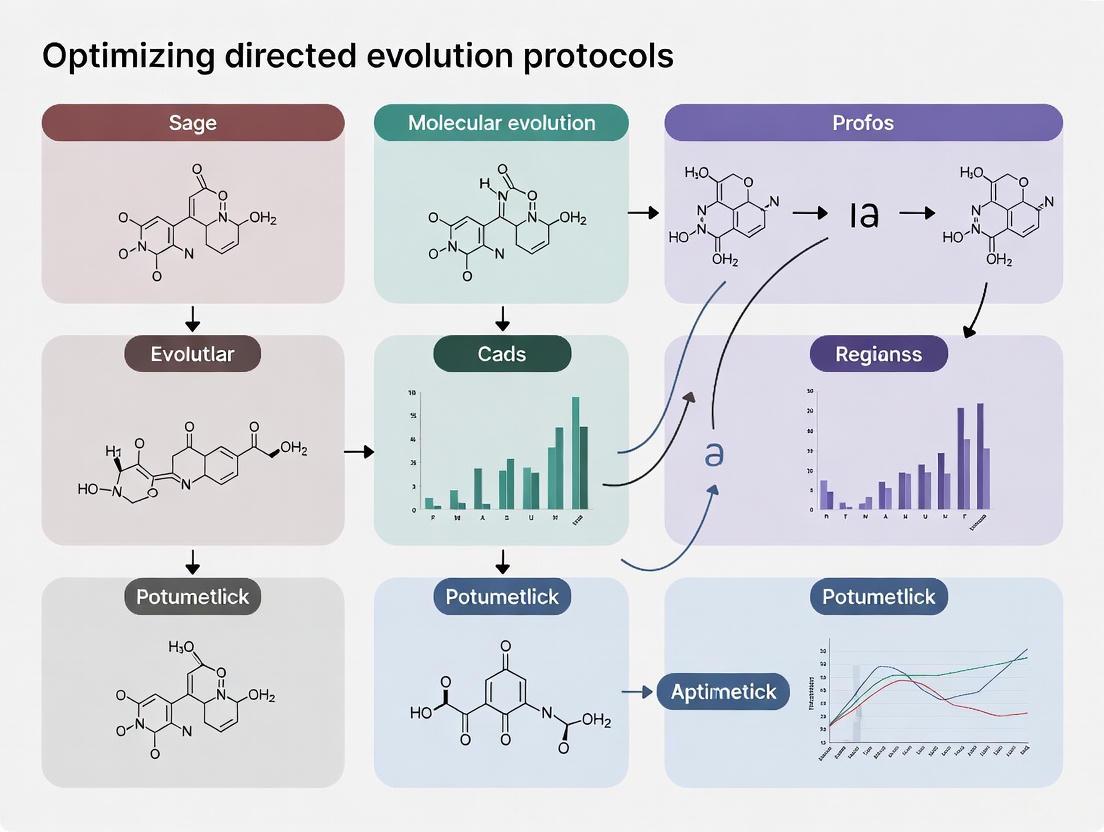

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

Fitness Landscape Diagram

Directed Evolution Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Systems for Directed Evolution

| Reagent / System | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Error-Prone PCR Kits | Introduces random mutations throughout the gene. | Can generate a high proportion of deleterious mutations; better suited for small genes [9]. |

| SEP & DDS (Segmental Error-prone PCR & Directed DNA Shuffling) | Advanced mutagenesis that minimizes negative and revertant mutations, ensuring even distribution. | Superior to traditional methods for large genes and for evolving multiple functionalities simultaneously [9]. |

| S. cerevisiae Expression System | A eukaryotic host for constitutive secretory expression. | Ideal for complex proteins requiring post-translational modifications; high recombination rate facilitates library construction [9]. |

| PACE (Phage-Assisted Continuous Evolution) | A continuous evolution system that rapidly links protein function to phage propagation. | Requires specialized setup but enables very rapid evolution without intermediary plating [15]. |

| EcORep (E. coli Orthogonal Replicon) | A synthetic system in E. coli enabling continuous mutagenesis and enrichment. | Useful for evolving proteins where function can be linked to plasmid replication in E. coli [15]. |

| High-Efficiency Competent Cells | Essential for achieving large library sizes after library construction. | Strains like NEB 10-beta are recommended for large constructs and methylated DNA. Avoid freeze-thaw cycles [14] [13]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why does my directed evolution experiment get stuck, failing to improve protein performance further? This is often a sign of a local optimum, a key limitation of traditional directed evolution. When using a simple "greedy" approach of selecting the best variant from one round to mutagenize for the next, the evolutionary path can become trapped on a small, local fitness peak, unable to reach higher peaks that require temporarily accepting less-fit variants. This is especially common in rugged fitness landscapes where mutations have strong epistatic (non-additive) interactions [7].

Q2: Why do beneficial single mutations sometimes combine to create a poorly performing variant? This is due to epistasis, where the effect of one mutation depends on the presence of other mutations in the sequence [7]. Traditional stepwise directed evolution, which assumes mutation effects are additive, often fails in such scenarios. For example, beneficial single mutations at five active-site residues in a protoglobin (ParPgb) were recombined, but none of the combinatorial variants showed the desired high yield and selectivity, demonstrating the challenge epistasis poses for traditional methods [7].

Q3: What are "selection parasites" or "false positives," and how do they hinder my screen? False positives are variants enriched during a selection round that do not possess the desired function. They may survive due to random, non-specific processes or by exploiting an alternative, undesired activity to survive the selection pressure [12]. For instance, in a compartmentalized screen, a polymerase variant might be recovered because it uses low levels of natural nucleotides present in the emulsion instead of the target unnatural substrates, thereby cheating the selection [12].

Q4: How do library size and selection parameters limit the efficiency of my campaign? The vastness of protein sequence space makes comprehensive coverage impossible. An average 300-amino-acid protein has more possible sequences than can be practically synthesized or screened [16]. Furthermore, suboptimal selection parameters (e.g., cofactor concentration, reaction time) can inadvertently favor the enrichment of these false positives or parasites over the truly desired variants, leading the experiment astray [12].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Stuck at a Local Optimum

- Symptoms: Performance plateaus after a few rounds of evolution. All new variants show no improvement or a decrease in fitness.

- Solution Checklist:

- Increase Library Diversity: Use DNA shuffling or other recombination methods to introduce greater sequence variation, potentially allowing escapes from the local optimum [4].

- Adjust Mutagenesis Rate: In error-prone PCR, optimize the error rate to balance exploration of new sequences with the stability of existing function [4].

- Implement Machine Learning (ML): Use Active Learning-assisted Directed Evolution (ALDE). An ML model trained on your screening data can predict which unexplored sequences, even lower-fitness ones, might lead to higher peaks, guiding your next library design [7].

Problem: Prevalence of False Positives

- Symptoms: High library recovery in a selection round, but subsequent analysis shows little to no desired activity among the enriched variants.

- Solution Checklist:

- Optimize Selection Stringency: Systematically adjust key parameters to disfavor false positives.

- Employ a Dual-Selection Strategy: Use negative selection to remove variants with the undesired "parasite" activity, followed by positive selection for the target function. This has been successfully implemented in continuous evolution systems like OrthoRep [17].

- Utilize a Robust Pre-Optimization Pipeline: Before running a large library, use a small, focused library and Design of Experiments (DoE) to screen various selection conditions (e.g., substrate concentration, metal cofactors, time). This identifies parameter ranges that maximize the recovery of true positives [12].

Data Presentation: Key Limitations and Comparisons

Table 1: Common Limitations in Traditional Directed Evolution and Their Impact

| Limitation | Description | Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Epistatic Interactions | Non-additive effects of combined mutations [7]. | Inability to predict optimal combinations; simple recombination of beneficial single mutations fails [7]. |

| Local Optima | Evolutionary trajectory gets stuck on a suboptimal fitness peak [7]. | Performance plateaus, preventing access to globally optimal variants. |

| Selection Parasites | False positives that survive selection via an undesired activity [12]. | Wasted resources on characterizing useless variants; campaign failure. |

| Library Size Constraint | Practical library sizes (~10^6-10^9 variants) are a tiny fraction of possible sequence space [16]. | High probability of missing the best variants. |

Table 2: Quantitative Analysis of a Site-Saturation Mutagenesis Project for a 300 AA Protein

| Delivery Format | Approximate Cost (USD) | Turnaround Time | Key Advantage | Key Disadvantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pooled (all variants in one tube) | ~$30,000 [16] | 4-6 weeks [16] | Cost-effective for accessing all single mutants. | No individual variant tracking. |

| Plated (single constructs) | ~$240,000 - $300,000 [16] | Up to 8 weeks [16] | Enables direct screening of individual variants. | Prohibitively expensive for large-scale saturation. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Optimizing Selection Parameters Using Design of Experiments (DoE)

Purpose: To efficiently identify selection conditions that maximize the enrichment of true positives and minimize false positives before committing to a large-scale evolution campaign [12].

Methodology:

- Library Design: Create a small, focused mutant library targeting a known functional region (e.g., a catalytic residue and its neighbors) [12].

- Factor Selection: Choose key selection parameters (factors) to test, such as:

- Substrate concentration and chemistry

- Divalent metal ion concentration (Mg²⁺, Mn²⁺)

- Selection reaction time

- Presence of PCR additives

- Experimental Setup: Use a DoE approach (e.g., a factorial design) to run the selection with your small library under a matrix of different factor combinations.

- Output Analysis: For each condition, analyze:

- Recovery Yield: Total number of variants recovered.

- Variant Enrichment: Identity and function of enriched sequences via Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS).

- Variant Fidelity: Accuracy of the enriched polymerases, if applicable.

- Condition Selection: Choose the selection parameters that best balance high recovery of the desired function with low background and parasite enrichment [12].

Protocol 2: Active Learning-Assisted Directed Evolution (ALDE)

Purpose: To efficiently navigate complex, epistatic fitness landscapes and escape local optima by integrating machine learning with iterative screening [7].

Methodology:

- Define Design Space: Select

kresidues to optimize simultaneously, defining a combinatorial space of 20^k possible variants [7]. - Initial Library Screening: Synthesize and screen an initial library of mutants (e.g., using NNK codons) at all

kpositions to collect an initial set of sequence-fitness data [7]. - Machine Learning Model Training: Use the collected data to train a supervised ML model that predicts fitness from sequence. The model should provide uncertainty estimates [7].

- Variant Proposal: Use an acquisition function (e.g., from Bayesian optimization) on the trained model to rank all sequences in the design space. This function balances "exploitation" (choosing predicted high-fitness variants) and "exploration" (choosing variants with high uncertainty) [7].

- Iterative Rounds: Synthesize and screen the top

Nproposed variants. Add the new sequence-fitness data to the training set and repeat steps 3-5 for multiple rounds until fitness is optimized [7].

Workflow Visualization

Traditional DE vs. ALDE Workflow

Selection Parameter Optimization

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Directed Evolution

| Reagent / Material | Function in Directed Evolution |

|---|---|

| NNK Degenerate Codon Primers | Allows for site-saturation mutagenesis by encoding all 20 amino acids and a stop codon at a specific site [7]. |

| Error-Prone PCR Kit | Introduces random point mutations throughout the entire gene to create diverse libraries [4]. |

| High-Efficiency Competent E. coli | Essential for achieving large library sizes (e.g., 10^9 transformants) to ensure adequate coverage of sequence space [16]. |

| Orthogonal Replication System (e.g., OrthoRep) | Enables continuous, targeted in vivo evolution by using a specialized DNA polymerase with a high mutation rate on a specific plasmid [17]. |

| NGS Library Prep Kit | Allows for deep sequencing of selection outputs to identify enriched variants and analyze library diversity [12]. |

Next-Generation Methodologies: AI-Guided and Automated Evolution

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guides

Workflow Optimization and Strategy

Q: My MLDE campaigns often get stuck at local optima, especially when optimizing epistatic regions like enzyme active sites. What strategies can help?

A: This is a common challenge in rugged fitness landscapes. Implement an Active Learning-assisted Directed Evolution (ALDE) workflow. Unlike one-shot MLDE, ALDE uses iterative batch Bayesian optimization. After each round of wet-lab experimentation, sequence-fitness data is used to retrain a supervised ML model. This model then uses an acquisition function to suggest the next batch of sequences to test, balancing the exploration of new regions with the exploitation of known high-fitness areas. This iterative loop more effectively navigates around local optima caused by epistasis [7].

Q: How can I design a high-quality starting library when I have no experimental fitness data for my target function?

A: You can use zero-shot predictors to infer fitness and design your initial library. The MODIFY algorithm is designed for this exact scenario. It uses an ensemble of unsupervised models, including protein language models (ESM-1v, ESM-2) and sequence density models (EVmutation, EVE), to predict fitness without prior experimental data. Crucially, MODIFY co-optimizes for both predicted fitness and sequence diversity, ensuring your starting library has a high likelihood of containing functional variants while also covering a broad area of sequence space to facilitate future learning [18].

Library Design and Implementation

Q: What are the practical steps for implementing an ALDE cycle in the lab?

A: A practical ALDE implementation involves a defined cycle [7]:

- Define a Combinatorial Space: Select

ktarget residues for mutagenesis (e.g., 5 residues in an active site). - Initial Library Synthesis: Create an initial library, for instance, by mutating all

kresidues simultaneously using NNK degenerate codons. - Wet-Lab Screening: Screen tens to hundreds of variants using your functional assay.

- Computational Model Training: Use the collected sequence-fitness data to train a supervised ML model. The model learns to map sequences to fitness.

- Variant Proposal: Use the trained model with an acquisition function to rank all possible sequences in your design space and select the top

Ncandidates for the next round. - Iterate: Return to step 3 for the next round of screening. This cycle repeats until a fitness goal is met.

Q: How do I choose a protein sequence encoding and model for fitness prediction?

A: Model performance depends on the context. The following table summarizes key findings from large-scale evaluations:

Table 1: Guidance on ML Model Components for MLDE

| Component | Recommendation | Key Insight / Finding |

|---|---|---|

| Uncertainty Quantification | Frequentist methods can be more consistent than Bayesian approaches in some ALDE contexts [7]. | Helps avoid overconfidence and guides exploration. |

| Deep Learning | Does not always boost performance; evaluate on your specific landscape [7]. | Simpler models can be sufficient and more robust with limited data. |

| Zero-Shot Predictors | Use ensemble models (like MODIFY) that combine PLMs and MSA-based models [18]. | Outperforms any single unsupervised model across diverse protein families. |

| Library Design Goal | Co-optimize fitness and diversity using Pareto optimization [18]. | Prevents library designs that are either too narrow (risking local optima) or too scattered (containing mostly low-fitness variants). |

Model Performance and Data Handling

Q: My model's predictions seem accurate on training data but fail to generalize to new variants. What could be wrong?

A: This is often a sign of data leakage or an uninformative training set. To avoid this [19]:

- Split Data Correctly: Always split your sequence-fitness data into training, validation, and test sets before any preprocessing or feature selection. The test set must remain completely untouched until the final model evaluation.

- Ensure Training Set Quality: A training set composed of mostly low-fitness, non-functional variants provides a poor signal for the model. Use zero-shot predictors or focused training (ftMLDE) to enrich your initial training library with more potentially functional variants [20].

Q: For a standard MLDE run on a combinatorial landscape of 3-4 residues, what level of performance improvement should I expect over traditional directed evolution?

A: Computational studies across 16 diverse combinatorial landscapes show that MLDE strategies consistently meet or exceed the performance of traditional directed evolution. The advantage of MLDE becomes most pronounced on landscapes that are difficult for DE, specifically those with fewer active variants and more local optima, which are hallmarks of strong epistasis [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for MLDE Experiments

| Item | Function in MLDE | Example Application / Note |

|---|---|---|

| NNK Degenerate Codons | Library generation for site-saturation mutagenesis. Allows for all 20 amino acids and one stop codon. | Used to create the initial combinatorial library at five active-site residues in ParPgb [7]. |

| Parent Enzyme Scaffold | A stable, expressible protein to engineer. | Thermostable protoglobin from Pyrobaculum arsenaticum (ParPgb) was used for cyclopropanation engineering [7]. |

| Gas Chromatography (GC) / HPLC | High-resolution analytical method for screening enzyme function. | Used to measure yield and diastereoselectivity in the ParPgb cyclopropanation reaction [7]. |

| Cell-Free Protein Synthesis (CFPS) System | Rapid, in vitro expression of protein variants for high-throughput screening. | Used in an AI antibody pipeline to express single-domain antibody constructs for binding assays [21]. |

| AlphaLISA Assay | A solution-phase, bead-based proximity assay for high-throughput binding affinity measurement. | Used to measure binding of expressed antibodies to the SARS-CoV-2 RBD antigen [21]. |

| pET Vector & E. coli BL21(DE3) | Standard prokaryotic system for recombinant protein expression and library maintenance. | Common host for enzyme and polymerase engineering campaigns [12]. |

Experimental Workflow Visualization

ALDE Workflow

MODIFY Library Design

Active Learning-Assisted Directed Evolution (ALDE) represents a significant advancement in protein engineering, integrating machine learning (ML) with traditional directed evolution to navigate complex protein fitness landscapes more efficiently. Directed evolution (DE), a Nobel Prize-winning method, is a powerful tool for optimizing protein fitness for specific applications, such as therapeutic development, industrial biocatalysis, and bioremediation. However, traditional DE can be inefficient when mutations exhibit non-additive, or epistatic, behavior, where the effect of one mutation depends on the presence of others. This epistasis creates rugged fitness landscapes that are difficult to traverse using simple hill-climbing approaches [7] [20].

ALDE addresses this fundamental limitation through an iterative machine learning-assisted workflow that leverages uncertainty quantification to explore the vast search space of protein sequences more efficiently than current DE methods. By alternating between wet-lab experimentation and computational prediction, ALDE can identify optimal protein variants with significantly reduced experimental effort, making it particularly valuable for optimizing complex protein functions where high-throughput screening is not feasible [7] [20].

Core Concepts and Workflow

Key Terminology

- Directed Evolution (DE): A protein engineering method that mimics natural evolution through iterative rounds of mutagenesis and screening to accumulate beneficial mutations [7] [20].

- Epistasis: Non-additive interactions between mutations where the effect of one mutation depends on the genetic background in which it occurs [7] [20].

- Fitness Landscape: A mapping of protein sequences to fitness values, representing their functionality for a desired application [7].

- Active Learning: A machine learning paradigm that iteratively selects the most informative data points to be experimentally tested, optimizing the learning process [7].

- Uncertainty Quantification: Computational methods that estimate the model's confidence in its predictions, crucial for balancing exploration and exploitation [7].

The ALDE Workflow

The ALDE workflow follows an iterative cycle that combines computational prediction with experimental validation. The process begins with defining a combinatorial design space focusing on key residues, typically in enzyme active sites or binding interfaces where epistatic effects are common [7].

Diagram 1: ALDE iterative workflow

The workflow proceeds through the following detailed steps:

Design Space Definition: Researchers select k target residues (typically 3-5) known to influence the desired function, creating a search space of 20^k possible variants. The choice of k balances consideration of epistatic effects against experimental feasibility [7].

Initial Data Collection: An initial library of variants is synthesized and screened to establish baseline sequence-fitness relationships. This can involve random selection or strategic sampling based on prior knowledge [7].

Model Training: A supervised ML model is trained on the collected sequence-fitness data to learn the mapping between sequence and fitness. Different sequence encodings and model architectures can be employed [7].

Variant Prioritization: The trained model, equipped with uncertainty quantification, ranks all possible variants in the design space using an acquisition function that balances exploration (testing uncertain regions) and exploitation (testing predicted high-fitness regions) [7].

Batch Selection: The top N variants from the ranking are selected for experimental testing in the next round. Batch selection strategies may incorporate diversity considerations to avoid over-sampling similar sequences [22].

Iterative Refinement: Steps 3-5 are repeated, with each round of new experimental data improving the model's understanding of the fitness landscape until the desired fitness level is achieved [7].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Establishing the Baseline: ParPgb Case Study

The development and validation of ALDE utilized a challenging model system: optimizing five epistatic residues (W56, Y57, L59, Q60, and F89 - designated WYLQF) in the active site of a Pyrobaculum arsenaticum protoglobin (ParPgb) for enhanced cyclopropanation activity [7].

Experimental Objective: Optimize the enzyme to improve yield and diastereoselectivity for a non-native cyclopropanation reaction between 4-vinylanisole and ethyl diazoacetate [7].

Initial Challenges:

- Single-site saturation mutagenesis (SSM) at each of the five positions failed to identify variants with significantly improved objective metrics

- Traditional recombination of the best single mutants did not yield improved variants, indicating strong epistatic interactions

- The design space contained 20^5 (3.2 million) possible variants, making comprehensive screening impractical [7]

Detailed ALDE Experimental Procedure

Library Construction:

- Mutants were generated using PCR-based mutagenesis with NNK degenerate codons

- Sequential rounds of mutagenesis enabled coverage of the combinatorial space

- DNA synthesis was supported by next-generation synthesis technologies [7] [23]

Screening Protocol:

- Enzyme variants were expressed and assayed for cyclopropanation activity

- Reaction products were analyzed by gas chromatography to quantify yield and diastereoselectivity

- Fitness was defined as the difference between cis-2a and trans-2a product yields [7]

Machine Learning Implementation:

- The computational component utilized the ALDE codebase (https://github.com/jsunn-y/ALDE)

- Models incorporated frequentist uncertainty quantification rather than Bayesian approaches

- Various sequence encodings and acquisition functions were evaluated [7]

Advanced Methodological Considerations

Recent advancements in ALDE methodologies have addressed several key challenges:

FolDE Enhancement: The FolDE method introduces naturalness-based warm-starting using protein language model (PLM) outputs to improve activity prediction. This approach addresses the limitation of conventional activity prediction models that struggle with limited training data [22].

Batch Selection Optimization: FolDE employs a constant-liar batch selection strategy with α=6 to improve batch diversity, preventing over-sampling of similar sequences in subsequent rounds [22].

Neural Network Architecture:

- Uses PLM (ESM-family) to embed protein sequences

- Implements neural network with ranking loss rather than regression loss

- Employs ensemble predictions for improved uncertainty quantification [22]

Performance Data and Comparative Analysis

Experimental Results from ParPgb Optimization

Table 1: ALDE performance in optimizing ParPgb cyclopropanation activity

| Metric | Starting Variant (ParLQ) | After 3 ALDE Rounds | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Yield | ~40% | 99% | 2.5x increase |

| Desired Product Yield | 12% | 93% | 7.75x increase |

| Diastereoselectivity | 3:1 (trans:cis) | 14:1 (cis:trans) | Significant reversal |

| Sequence Space Explored | - | ~0.01% of design space | Highly efficient |

The ALDE campaign achieved remarkable success after only three rounds of experimentation, exploring just approximately 0.01% of the total design space while dramatically improving both yield and selectivity. The optimal variant contained mutations that were not predictable from initial single-mutation scans, highlighting the importance of ML-based modeling for capturing epistatic effects [7].

Comparative Performance Across Methods

Table 2: Method comparison across protein engineering landscapes

| Method | Key Features | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional DE | Greedy hill-climbing; iterative mutagenesis/screening | Simple implementation; proven track record | Inefficient on epistatic landscapes; prone to local optima |

| MLDE | Single-round model training and prediction | Broader sequence space exploration | Limited by initial training data quality |

| ALDE | Iterative active learning with uncertainty quantification | Efficient navigation of epistatic landscapes; requires fewer experiments | Computational complexity; requires careful parameter tuning |

| FolDE | Naturalness warm-starting; diversity-aware batch selection | Addresses batch homogeneity; improved performance in low-N regime | Recent method requiring further validation |

Computational Benchmarking Results

Large-scale computational studies evaluating ML-assisted directed evolution across 16 diverse combinatorial protein fitness landscapes have demonstrated:

- MLDE strategies consistently match or exceed DE performance across all landscapes tested

- The advantage of MLDE increases with landscape difficulty (fewer active variants, more local optima)

- Focused training using zero-shot predictors further enhances performance

- Active learning approaches (ALDE) provide particular benefits on challenging epistatic landscapes [20]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential research reagents for ALDE implementation

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application in ALDE |

|---|---|---|

| NNK Degenerate Codons | Allows coding for all 20 amino acids | Library construction for initial variant screening |

| PCR-based Mutagenesis | Site-directed mutagenesis | Generating focused variant libraries |

| Gas Chromatography | Reaction product quantification | High-precision fitness assessment for enzyme variants |

| ESM Protein Language Models | Sequence embedding and naturalness prediction | Zero-shot variant prioritization; feature generation |

| ALDE Software | Machine learning workflow management | Model training, uncertainty quantification, variant ranking |

| Next-Gen DNA Synthesis | Rapid gene fragment production | Accelerated library construction for testing predicted variants |

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: How do I determine the optimal number of residues (k) to include in my ALDE design space? The choice of k involves balancing competing considerations. Larger k values (typically 3-5) allow consideration of more extensive epistatic networks and potentially better outcomes, but require collecting more experimental data. Smaller k values (2-3) are more manageable but may miss important epistatic interactions. Consider starting with 4-5 residues known from structural or previous studies to be in close proximity in the active site or functional regions [7].

Q2: What type of machine learning model performs best for ALDE? Current research indicates that models with frequentist uncertainty quantification often work more consistently than Bayesian approaches. While deep learning can be powerful, it doesn't always outperform simpler models. The optimal choice depends on your specific landscape and available data. Ensemble methods generally provide more robust uncertainty estimates [7] [22].

Q3: How many variants should I screen in each round of ALDE? ALDE is compatible with low-throughput settings where tens to hundreds of variants are screened per round. Typical batch sizes range from 16-96 variants per round, depending on experimental constraints. The key is consistency across rounds rather than absolute numbers [7] [22].

Q4: Can ALDE be applied to multi-property optimization? While the published case studies focus on single objectives, the framework can be extended to multi-property optimization by defining appropriate multi-objective fitness functions and using corresponding acquisition strategies, though this remains an active research area.

Troubleshooting Guide

Problem: Poor model performance after the first round

- Potential Cause: Insufficient diversity in initial training data

- Solution: Incorporate naturalness-based warm-starting using protein language models (as in FolDE) to augment limited experimental data [22]

- Alternative Solution: Ensure initial library includes structurally diverse variants, not just high-predicted-fitness variants

Problem: Batch homogeneity in selected variants

- Potential Cause: Over-exploitation in acquisition function

- Solution: Implement diversity-aware batch selection strategies such as constant-liar algorithm with appropriate α values [22]

- Alternative Solution: Adjust acquisition function parameters to increase exploration weight

Problem: Failure to improve fitness across rounds

- Potential Cause: High experimental noise obscuring true fitness signals

- Solution: Implement replicate measurements for critical variants to reduce noise

- Alternative Solution: Review fitness metric definition to ensure it properly captures the engineering objective

Problem: Computational bottlenecks in model training

- Potential Cause: Large design spaces or complex model architectures

- Solution: Use efficient sequence encodings and feature representations

- Alternative Solution: Leverage pre-computed protein language model embeddings

Diagram 2: ALDE troubleshooting guide

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My DeepDE model is training slowly. What could be the cause and how can I speed it up? Training deep learning models is computationally intensive [24]. Ensure you are using hardware with a high-performance Graphics Processing Unit (GPU), which enables the parallel processing required for efficient deep learning [24]. Also, verify that your software framework (e.g., PyTorch or TensorFlow) is configured to leverage GPU acceleration [24].

Q2: The model's predictions for triple-mutant fitness are inaccurate despite good training data. How can I improve performance? This can be caused by epistasis, where the effect of one mutation depends on the presence of others [7]. To navigate this complex, "rugged" fitness landscape, incorporate active learning workflows. Use an acquisition function that balances exploration of new sequence regions with exploitation of currently predicted high-fitness variants [7]. This allows the model to intelligently request new data points that resolve uncertainties.

Q3: How do I determine the optimal batch size for the next round of screening? The choice involves a trade-off. Larger batches enable more parallel screening but may be less efficient in terms of mutations found per experiment. For a design space of five residues (20^5 = 3.2 million variants), an initial batch of tens to hundreds of sequences is a practical starting point [7]. Monitor the model's uncertainty estimates; high uncertainty across the space may warrant a larger, more exploratory batch.

Q4: What is the recommended way to encode protein sequences for the DeepDE model? Protein sequences must be converted into a numerical format. While one-hot encoding is a common baseline, consider using embeddings from protein language models, which can capture complex evolutionary and structural information, often leading to better performance on epistatic landscapes [7].

Q5: How do I know if my model has converged and no further rounds of evolution are needed? Convergence can be determined by monitoring the fitness of the top proposed variants over successive active learning rounds. The process can be stopped when the fitness gains between rounds fall below a pre-defined threshold or when the top variants consistently achieve your target performance metric in wet-lab validation [7].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Generalization from Training Data to New Mutants

- Symptoms: The model performs well on its training data but makes poor fitness predictions for new triple mutants, leading to unsuccessful screening rounds.

Possible Causes & Solutions:

Cause Diagnostic Steps Solution Overfitting Check for a large gap between training and validation error. Increase the amount of training data. Apply regularization techniques like dropout, which was popularized from the probabilistic interpretation of neural networks [25]. Inadequate Model Capacity The model is unable to capture the complexity of the fitness landscape. Gradually increase the number of layers or neurons in the hidden layers [24]. Poor Sequence Encoding The numerical representation fails to capture residue similarities. Switch from one-hot encoding to more sophisticated embeddings derived from protein language models [7].

Problem: Wet-Lab Validation Results Do Not Match Model Predictions

- Symptoms: Variants selected by the model as high-fitness fail to show improvement when experimentally tested.

Possible Causes & Solutions:

Cause Diagnostic Steps Solution Inaccurate Uncertainty Quantification The model is overconfident in its incorrect predictions. Implement frequentist uncertainty quantification methods, which have been shown to work more consistently than some Bayesian approaches in protein engineering [7]. Assay Noise High variability in the wet-lab fitness measurements. Re-test top candidate variants with experimental replicates to confirm their fitness. Review and standardize the wet-lab assay protocol to reduce noise. Epistatic Interactions The model has not sufficiently explored higher-order interactions. Use an acquisition function (e.g., in Bayesian optimization) that prioritizes exploration to sample regions of sequence space with high predictive uncertainty [7].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing an Active Learning Cycle for Directed Evolution

This protocol outlines the computational and experimental cycle for DeepDE, adapted from the ALDE workflow [7].

- Define Sequence Space: Select

kresidues to mutate, defining a search space of 20^k possible variants [7]. - Collect Initial Data: Synthesize and screen an initial library of variants mutated at all

kpositions. This provides the first set of sequence-fitness data for model training. Use NNK degenerate codons for randomization [7]. - Train Model: Use the collected data to train a supervised deep learning model to predict fitness from sequence. Use appropriate sequence encodings and ensure the model can provide uncertainty estimates [7].

- Rank Variants: Apply an acquisition function to the trained model to rank all sequences in the design space from most to least promising [7].

- Screen Next Batch: Select the top N variants from the ranking and assay them in the wet-lab to obtain new fitness data [7].

- Iterate: Add the new data to the training set and repeat steps 3-5 until a variant with satisfactory fitness is obtained [7].

Protocol 2: Training a Deep Neural Network for Fitness Prediction

This protocol details the model training process, which is central to the DeepDE algorithm [24].

- Input Data: Convert amino acid sequences into numerical vector embeddings [7] [24].

- Forward Pass: Data is passed through the network's layers. Each layer's neurons perform a nonlinear activation function (e.g., ReLU) on the weighted sum of inputs from the previous layer [24].

- Loss Calculation: At the output layer, a loss function calculates the error between the predicted fitness and the experimentally measured ground-truth fitness [24].

- Backpropagation: The error is propagated backward through the network. Using the chain rule, the gradient of the loss function with respect to every model parameter (weight and bias) is calculated [24].

- Gradient Descent: An optimization algorithm (e.g., stochastic gradient descent) uses the computed gradients to update the model's weights and biases, reducing the prediction error [24].

- Iteration: Steps 2-5 are repeated for multiple epochs over the training data until the model's performance converges [24].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in DeepDE |

|---|---|

| NNK Degenerate Codon | Used in library synthesis to randomize target residues. NNK codes for all 20 amino acids and one stop codon, providing full coverage of the sequence space [7]. |

| Deep Learning Framework (e.g., PyTorch/TensorFlow) | An open-source software library that provides preconfigured modules and workflows for building, training, and evaluating deep neural networks [24]. |

| Protein Language Model | A pre-trained deep learning model that generates numerical embeddings (vector representations) from amino acid sequences. These embeddings capture evolutionary information and are used as input for the fitness prediction model [7]. |

Workflow Visualization

DeepDE Active Learning Cycle

Neural Network Training Process

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the key differences between random and semi-rational diversification strategies?

Random mutagenesis methods, such as error-prone PCR (epPCR) and DNA shuffling, introduce mutations throughout the entire gene without requiring prior structural or functional knowledge. This allows for the exploration of a vast sequence space but often requires screening large libraries. In contrast, semi-rational approaches like saturation mutagenesis target specific residues or regions, resulting in smaller, smarter libraries that require less screening effort but depend on existing information about critical positions [26] [4].

FAQ 2: How can I overcome the limitations of traditional error-prone PCR?

Traditional epPCR can have a biased mutation spectrum and rarely generates contiguous mutations or indels. To address this, you can:

- Use specialized methods: Techniques like error-prone Artificial DNA Synthesis (epADS) incorporate base errors from oligonucleotide chemical synthesis under specific conditions, providing a more balanced spectrum of mutation types, including indels [26].

- Improve cloning efficiency: Employ restriction- and ligation-independent cloning methods, such as Circular Polymerase Extension Cloning (CPEC), to minimize the loss of library diversity during the cloning step and obtain a greater number of gene variants [27].

FAQ 3: When should I use DNA shuffling versus other recombination-based methods?

DNA shuffling is ideal when you have several parent genes with high sequence homology and aim to recombine their beneficial mutations. For genes with low sequence similarity, consider alternative methods:

- RACHITT: Results in decreased mismatching and allows recombination of genes with low similarity, but requires preparation of single-stranded DNA fragments [28].

- Non-homologous methods: Techniques like ITCHY and SHIPREC do not require sequence homology, enabling the recombination of any two sequences, but they often result in a single crossover per variant and do not preserve the reading frame [4].

FAQ 4: What strategies can improve the efficiency of multi-site saturation mutagenesis?

Simultaneously mutagenizing multiple sites can be challenging. The Golden Mutagenesis protocol leverages Golden Gate cloning with type IIS restriction enzymes (e.g., BsaI, BbsI) to efficiently assemble multiple mutagenized gene fragments in a one-pot reaction. This method is seamless, avoids unwanted mutations in the plasmid backbone, and allows for the rapid construction of high-quality libraries targeting one to five amino acid positions within a single day [29].

FAQ 5: How is machine learning being integrated into directed evolution?

Machine learning (ML) assists in navigating complex fitness landscapes, especially when mutations exhibit epistasis (non-additive effects). Active Learning-assisted Directed Evolution (ALDE) is an iterative workflow that uses ML models to predict sequence-fitness relationships. It leverages uncertainty quantification to propose the most informative batches of variants to synthesize and test in the next round, enabling a more efficient exploration of the sequence space than traditional directed evolution [7].

Troubleshooting Guides

Table 1: Troubleshooting Error-Prone PCR and Related Methods

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low mutation frequency | Overly high-fidelity reaction conditions; incorrect buffer composition. | Increase MgCl₂ concentration; add MnCl₂; use unequal dNTP concentrations; use a dedicated low-fidelity polymerase [30] [31]. |

| Biased mutation spectrum | Intrinsic bias of the polymerase or mutagenesis method. | Use an epPCR kit designed for balanced mutation rates; consider alternative methods like epADS, which can generate a wider variety of mutations including indels [26] [4]. |

| Low library diversity after cloning | Inefficient ligation and transformation in traditional cut-and-paste cloning. | Switch to a ligation-independent cloning method like Circular Polymerase Extension Cloning (CPEC) to improve the number of correct clones obtained [27]. |

| Low proportion of functional variants | High mutational load leading to deleterious mutations and frameshifts. | Optimize the mutation rate (e.g., by adjusting the number of PCR cycles or the concentration of mutagenic agents) to achieve 1-3 amino acid changes per variant on average [4] [30]. |

Table 2: Troubleshooting DNA Shuffling and Saturation Mutagenesis

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor recombination efficiency in DNA shuffling | Low sequence homology between parent genes; suboptimal fragment size. | Ensure parent genes have sufficient homology for reassembly. If homology is low, use non-homologous methods like ITCHY or SHIPREC. Fragment DNA to an optimal size of 10-50 bp to 1 kbp [4] [28]. |

| Unwanted background (parental sequences) | Incomplete digestion of parental template or incomplete fragmentation. | Use a ssDNA template in RACHITT to reduce parental background; optimize the DNase I concentration and digestion time for fragmentation [4] [28]. |

| Inefficient assembly in multi-site saturation mutagenesis | Increasing complexity with multiple fragments leads to low ligation efficiency. | Use a hierarchical cloning strategy (e.g., Golden Mutagenesis), where fragments are first subcloned into an intermediate vector before final assembly into the expression vector [29]. |

| Bias in codon representation | Degenerate primers (e.g., NNK) have inherent codon bias. | Use primers with reduced-degeneracy codons (e.g., NDT); analyze the resulting library by sequencing a pool of colonies to check randomization success [29]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Generating a Variant Library using Error-Prone PCR and CPEC

This protocol describes how to create a diverse library using error-prone PCR and efficiently clone it using Circular Polymerase Extension Cloning (CPEC) [27].

- Gene Amplification by epPCR: Amplify your target gene (e.g., DsRed2) using a commercial random mutagenesis kit or a custom epPCR mix. Typical conditions may involve 30 cycles of amplification.

- Purification: Verify the PCR product on a 1% agarose gel and purify it using a commercial PCR purification kit.

- CPEC Reaction:

- Use a high-fidelity DNA polymerase (e.g., TAKARA LA Taq).

- Mix the purified mutant insert and your linearized vector in a 1:1 molar ratio. The vector and insert must have complementary overlapping ends (15-20 bp).

- Run the CPEC reaction: 94°C for 2 min (initial denaturation), followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 15 s, 63-66°C for 30 s, 68°C for 4 min, and a final elongation at 72°C for 5-10 min.

- Transformation: Transform the entire CPEC reaction product into a competent E. coli expression strain (e.g., BL21(DE3)).

- Screening: Plate the transformation on selective media and screen colonies for the desired phenotype.

Protocol 2: DNA Shuffling by Molecular Breeding

This protocol outlines the classic DNA shuffling method to recombine beneficial mutations from homologous parent genes [32] [28].

- Fragmentation: Combine several parent genes (or a pool of related sequences). Digest the DNA pool with DNase I in the presence of Mn²⁺ to generate random fragments of 10-50 bp to 1 kbp.

- Size Selection: Purify the fragments of the desired size range (e.g., 50-200 bp) from an agarose gel.

- Reassembly PCR:

- Perform a primerless PCR. In the first cycles, the homologous fragments will randomly anneal to each other based on sequence similarity and be extended by a DNA polymerase.

- Typical conditions: 40-60 cycles of 94°C for 30-60 s, 50-60°C for 30-90 s, and 72°C for 30-60 s.

- Amplification: Add primers complementary to the ends of the full-length gene to the reassembly mixture and run a standard PCR to amplify the shuffled, full-length products.

- Cloning and Screening: Clone the resulting PCR products into an expression vector and screen the library for improved or novel functions.

Protocol 3: Multi-Site Saturation Mutagenesis via Golden Mutagenesis

This protocol uses Golden Gate cloning to simultaneously mutate multiple codons efficiently [29].

- Primer Design: Use the dedicated online tool to design primers. Each primer must contain, from 5' to 3':

- A type IIS restriction enzyme site (e.g., for BsaI or BbsI).

- A specified 4 bp overhang for assembly.

- The randomization site (e.g., an NNK or NDT codon).

- A template-binding sequence.

- PCR Amplification of Fragments: Amplify the gene fragments containing the desired mutations using high-fidelity polymerase.

- Golden Gate Reaction:

- Set up a one-pot reaction containing the purified PCR fragments, the recipient vector, the type IIS enzyme (e.g., BsaI-HFv2), and a DNA ligase (e.g., T7 DNA ligase).

- Incubate the reaction in a thermocycler with cycles of digestion and ligation (e.g., 30 cycles of 37°C for 5 min and 16°C for 5 min), followed by a final digestion step at 60°C to inactivate the enzyme.

- Transformation and Analysis: Transform the reaction directly into an E. coli BL21(DE3) pLysS expression strain. The use of a color-based selection marker (like CRed) allows for easy visual identification of successful clones. Sequence a pool of colonies to analyze the randomization success.

Workflow Diagrams

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Advanced Diversification

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Low-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Catalyzes error-prone PCR by incorporating incorrect nucleotides during amplification. | Choose polymerases with known error rates; commercial kits (e.g., GeneMorph II) are optimized for a balanced mutation spectrum [27] [30]. |

| Type IIS Restriction Enzymes (BsaI, BbsI) | Enable Golden Gate cloning by cutting outside their recognition site, creating unique overhangs for seamless fragment assembly. | Allows for one-pot digestion and ligation; crucial for efficient multi-site saturation mutagenesis protocols like Golden Mutagenesis [29]. |

| DNase I | Randomly fragments DNA for recombination-based methods like DNA shuffling. | Requires optimization of concentration and digestion time to generate fragments of optimal size (e.g., 50-200 bp) [28]. |

| Degenerate Primers (NNK, NDT) | Used in saturation mutagenesis to randomize specific codons. NNK codes for all 20 amino acids and one stop codon, while NDT reduces codon bias and covers 12 amino acids. | Critical for designing smart libraries; NDT codons can help reduce library size and bias [29]. |

| Mutator Strains (e.g., XL1-Red) | E. coli strains with defective DNA repair pathways that introduce random mutations during plasmid replication. | Useful for in vivo mutagenesis; however, strains can become sick over time, requiring multiple transformation steps [4] [31]. |

| CRed/LacZ Selection System | Visual screening markers in Golden Gate-compatible vectors. Successful assembly disrupts the marker gene, allowing easy identification of correct clones (white/orange vs. blue colonies). | Greatly increases screening efficiency by eliminating negative clones from the screening process [29]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Poor Assay Quality and High Variability

Problem: The screening assay shows a small difference between positive and negative controls (low signal window) or high well-to-well variability, making it difficult to reliably distinguish true hits from background noise.

| Observed Symptom | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Low Z' factor (<0.5) or Signal-to-Noise ratio [33] [34] | Reagent instability or improper storage | Aliquot and freeze-thaw reagents a limited number of times; validate new reagent lots against old lots [33]. |

| High background signal | Assay interference from compound solvent (DMSO) | Perform a DMSO tolerance test; ensure final DMSO concentration is ≤1% for cell-based assays [33]. |

| Edge effects (systematic variation across the plate) | Evaporation in edge wells or temperature gradients | Use plate seals during incubations; validate assay with interleaved signal format to identify positional effects [33]. |

| Inconsistent results between runs | Unstable reaction kinetics or extended reagent incubation times | Conduct time-course experiments to define optimal and maximum incubation times for each step [33]. |

Guide 2: Troubleshooting High False Positive or Negative Rates in Selections

Problem: Many hits from a selection round fail upon re-testing (false positives), or known active variants are not enriched (false negatives).

| Observed Symptom | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| High false positive rate in directed evolution | Selection "parasites" (e.g., variants that thrive under conditions but not for the desired function) [12] | Systematically optimize selection parameters (e.g., cofactor concentration, time) using Design of Experiments (DoE) [12]. |

| False positives in small-molecule HTS | Compound-mediated assay interference (e.g., aggregation, fluorescence) [35] | Implement counter-screens and use cheminformatic filters (e.g., pan-assay interference substructure filters) to triage hits [35]. |

| Low recovery of desired phenotypes | Overly stringent selection conditions | Use a small, focused library to benchmark and adjust selection pressure before running a full library [12]. |

| Inconsistent genotype-phenotype linkage | Inefficient compartmentalization in emulsion-based screens [12] | Validate emulsion stability and ensure single genotype per compartment. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key statistical metrics for validating my HTS assay's robustness, and what are their acceptable values?

The key metrics are the Z'-factor and the Signal Window.

- Z'-factor: A measure of the assay's suitability for HTS that incorporates both the dynamic range and the data variation of the positive and negative controls. A Z'-factor ≥ 0.5 is excellent, and ≥ 0 is acceptable for a screenable assay [34].

- Signal Window (SW): The separation between the positive and negative control signals. An SW ≥ 2 is generally desirable [33]. These are calculated from control data on validation plates: Z' = 1 - [3*(σpositive + σnegative) / |μpositive - μnegative|].

Q2: How can I optimize selection conditions for a directed evolution campaign when I have limited knowledge of the target protein?

Employ a systematic pipeline using Design of Experiments (DoE) [12].

- Design a Small Library: Create a focused mutant library targeting a few key residues.

- Select Factors: Choose critical selection parameters (e.g., Mg²⁺ concentration, substrate concentration, time).

- Run DoE: Screen the small library against a matrix of these factor combinations.

- Analyze Outputs: Measure responses like recovery yield, variant enrichment, and fidelity.

- Scale Up: Apply the optimized conditions to your large, diverse library. This method efficiently identifies conditions that maximize the selection of desired variants [12].

Q3: Our HTS campaign generated a large number of hits. How should we prioritize them for follow-up?

A triage process is essential [35]:

- Remove Obvious False Positives: Filter out compounds with known pan-assay interference substructures or undesirable properties.

- Confirm Activity: Re-test the raw hits in a dose-response format to confirm the activity and quantify potency (e.g., EC50, IC50).

- Counter-Screens: Test confirmed hits in orthogonal assays (e.g., a different technology) and against related targets to assess selectivity.

- Analyze Structure-Activity Relationships (SAR): Cluster hits by chemical structure to identify promising scaffolds for further optimization [36].

Q4: What computational tools can help identify genotype-phenotype linkages from high-throughput sequencing data of enriched variants?

Machine learning (ML) tools are highly effective for this. For example, deepBreaks is a generic ML approach that:

- Takes a multiple sequence alignment of enriched variants and their associated phenotypic data (e.g., activity, stability).

- Fits multiple ML models to the data and selects the best-performing one.

- Uses the top model to identify and prioritize the sequence positions (genotypes) that are most predictive of the phenotype [37]. This helps pinpoint key mutations driving the improved function.

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Plate Uniformity and Variability Assessment for HTS Assay Validation

Purpose: To establish the robustness and reproducibility of an HTS assay before screening a full compound or variant library [33].

Methodology:

- Plate Design: Use an interleaved-signal format on at least 3 separate days.

- Use the plate layout below, which distributes Max (H), Mid (M), and Min (L) signals across the plate [33].

- Max Signal (H): Represents the maximum assay response (e.g., uninhibited enzyme activity, full agonist response).

- Min Signal (L): Represents the minimum assay response (e.g., fully inhibited enzyme, negative control).

- Mid Signal (M): Represents an intermediate response (e.g., IC50 concentration of an inhibitor, EC50 concentration of an agonist) [33].

- Use the plate layout below, which distributes Max (H), Mid (M), and Min (L) signals across the plate [33].

- Data Analysis: Calculate the Z'-factor and Signal Window for each plate. The assay is considered validated if these metrics are consistently within acceptable ranges across all days [33] [34].

Protocol 2: Optimizing Selection Conditions using a Focused Library

Purpose: To efficiently determine the optimal selection parameters (e.g., cofactor, substrate concentration) for a directed evolution experiment without the cost of screening a full library [12].

Methodology:

- Library Construction: Generate a small, focused mutant library (e.g., via saturation mutagenesis at 2-5 key active site residues) [12].

- Experimental Design: Use a Design of Experiments (DoE) approach to define a set of selection conditions that vary multiple parameters (Factors) simultaneously.

- Run Selections: Subject the focused library to each set of conditions in the experimental matrix.

- Output Analysis: For each selection output, measure key Responses:

- Recovery Yield: The amount of DNA/vector recovered.

- Variant Enrichment: The diversity and identity of variants after selection, determined by next-generation sequencing (NGS).

- Fidelity: The functional accuracy of the enriched variants (e.g., synthesis error rate for polymerases) [12].

- Identify Optimum: Use statistical analysis to find the selection conditions that maximize the desired responses (e.g., highest yield of the most active variants).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in HTS/Selection | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Microtiter Plates [34] | The standard vessel for HTS reactions, available in 96, 384, 1536, and 3456-well formats. | Choose well density based on assay volume and throughput needs. Ensure compatibility with readers and liquid handlers. |

| Scintillation Proximity Assay (SPA) Beads [36] | Enables homogeneous radioligand binding assays without separation steps by capturing the target on scintillant-containing beads. | Ideal for binding assays (e.g., GPCRs). Minimizes radioactive waste but may be difficult to miniaturize beyond 384-well [36]. |

| Fluorescent Dyes (FRET, FP, TRF) [36] | Provide a sensitive, homogeneous readout for a wide range of assays, including binding, enzymatic activity, and cell signaling. | Time-resolved fluorescence (TRF) reduces background. Fluorescence Polarization (FP) is ideal for monitoring molecular binding [36]. |

| Engineered Cell Lines [36] [35] | Used in cell-based assays to report on receptor activation, gene expression, or cytotoxicity (e.g., using FLIPR, luciferase reporters). | Ensure consistent cell passage number and health. Use "promiscuous" G-proteins to link receptors to calcium mobilization for universal signaling readouts [36]. |

| Compartmentalization Matrix (e.g., for Emulsion PCR) [12] | Creates water-in-oil emulsions to provide a physical linkage between a genotype (DNA) and its phenotype (e.g., enzyme activity) in directed evolution. | Critical for minimizing cross-talk and selecting for catalysts. Emulsion stability is paramount for selection efficiency [12]. |