Optimizing Sequence Alignment Blocks for Accurate Gene Tree Inference: A Practical Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Accurate gene tree inference is foundational for evolutionary studies, drug target discovery, and understanding disease mechanisms, yet it is highly dependent on the quality of input sequence alignments.

Optimizing Sequence Alignment Blocks for Accurate Gene Tree Inference: A Practical Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

Accurate gene tree inference is foundational for evolutionary studies, drug target discovery, and understanding disease mechanisms, yet it is highly dependent on the quality of input sequence alignments. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing sequence alignment blocks to overcome common pitfalls and enhance phylogenetic accuracy. Covering foundational principles to advanced validation techniques, we explore the critical impact of gap placement and alignment algorithms on tree topology, introduce innovative methods like attention-based region selection and alignment-free pipelines, and offer practical troubleshooting strategies for handling missing data and recombination. Furthermore, we benchmark modern tools and methodologies, providing a clear framework for selecting and validating approaches that deliver the highest phylogenetic resolution and reliability for biomedical applications.

The Building Blocks of Accuracy: How Alignment Quality Directly Governs Gene Tree Inference

In molecular phylogenetics, an alignment block (or sequence block) is a curated segment of a multiple sequence alignment (MSA) used for phylogenetic inference. These blocks are extracted from larger genomic alignments and are selected for their high information content, minimal missing data, and low signals of recombination [1]. The quality and selection of these blocks are foundational to constructing reliable gene trees and, by extension, accurate species phylogenies [2] [3]. Properly optimized alignment blocks help mitigate errors arising from evolutionary complexities like incomplete lineage sorting, horizontal gene transfer, and hybridization [3].

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ: What are the most common issues that lead to unreliable phylogenies from alignment blocks? Common issues include:

- Alignment Errors: Incorrectly aligned homologous positions, which can be introduced during the multiple sequence alignment step [3].

- Within-Alignment Recombination: Recombination events within an alignment block can create conflicting phylogenetic signals [1].

- High Proportion of Missing Data: Alignment blocks with excessive gaps or missing sequences for certain taxa can lead to unstable and inaccurate trees [1].

- Model Inadequacy: Using an overly simplistic evolutionary model that does not reflect the actual processes, such as ignoring variations in substitution rates among sites [3].

FAQ: How can I select the best alignment blocks from a whole-genome alignment for phylogenetic analysis? Ideal alignment blocks for phylogenetic analysis should meet these criteria [1]:

- Completeness: Contain a sequence for every species in your analysis.

- Minimum Length: Be long enough to be informative (e.g., 1,000 bp is often a practical starting point).

- Low Missing Data: Have as few gaps and missing sequences as possible.

- High Information Content: Contain a sufficient number of polymorphic sites.

- No Recombination: Show minimal signals of within-block recombination breakpoints.

FAQ: My gene trees show conflicts with the expected species tree. What could be the cause? Conflicts between gene trees and the species tree are common and can be due to real biological phenomena or analytical issues.

- Biological Causes: Incomplete Lineage Sorting (ILS), horizontal gene transfer, hybridization, and introgression can cause gene histories to differ from the species history [3].

- Analytical Causes: Long-branch attraction, alignment errors, or model misspecification can produce misleading topological patterns [3]. Using methods like ASTRAL, which estimates a species tree from a set of gene trees, can be more robust to such conflicts [1].

FAQ: How can I assess the reliability of my phylogenetic tree?

- Statistical Support: Use bootstrapping to assign support values to the branches of your tree. A high bootstrap value (e.g., >95%) indicates that the branch is found in a high percentage of trees generated from resampled versions of your alignment [4].

- Taxonomic Congruence: Check if the inferred tree agrees with established taxonomic classifications [3].

- Concordance with Alternative Methods: Compare trees built using different methods (e.g., Maximum Likelihood vs. coalescent-based methods) to see if the major topological features are consistent [3].

Experimental Protocols and Data Presentation

Protocol 1: Extracting and Filtering Alignment Blocks from a Whole-Genome Alignment

This protocol is adapted from materials for tree-based introgression detection [1].

1. Obtain Whole-Genome Alignment:

- Start with a whole-genome alignment file, often in MAF (Multiple Alignment Format) converted from a reference-free HAL format using tools like

hal2maf[1].

2. Extract Initial Blocks:

- Use a custom Python script to scan the MAF file and extract alignment blocks of a fixed length (e.g., 1,000 bp) that contain sequences for all taxa in your study [1].

3. Filter Alignment Blocks:

- Filter for Completeness: Remove blocks with a high percentage of missing data (gaps or missing sequences).

- Filter for Recombination: Quantify signals of recombination per alignment (e.g., using phylogenetic methods) and remove blocks with the strongest signals.

- Filter for Information Content: Select blocks with a sufficient number of parsimony-informative or polymorphic sites.

4. Output Suitable Alignments:

- The final output is a set of high-quality, filtered alignment blocks in a standard phylogenetic format (e.g., FASTA, PHYLIP) ready for tree inference.

Protocol 2: Constructing a Phylogeny from a Set of Alignment Blocks

This protocol outlines a standard workflow for phylogenomics [1] [4].

1. Multiple Sequence Alignment:

- If not already done, perform a multiple sequence alignment for each gene or locus. For pre-extracted blocks, this step may involve refining the existing alignment.

2. Gene Tree Inference:

- For each filtered alignment block, infer a gene tree using a method such as Maximum Likelihood (e.g., with IQ-TREE) or Bayesian Inference.

- Model Selection: Use model testing tools integrated within programs like IQ-TREE to find the best-fit evolutionary model (e.g., LG or JTT for proteins) for each alignment [3].

3. Species Tree Inference:

- Coalescent-based Method: Use the set of gene trees as input to a coalescent-based species tree estimator (e.g., ASTRAL) to account for incomplete lineage sorting [1].

- Concatenation Method: Alternatively, concatenate all alignment blocks into a "supermatrix" and infer a species tree directly using Maximum Likelihood. Note that concatenation can be statistically inconsistent under some conditions [3].

4. Assess Tree Reliability:

- Perform bootstrapping (e.g., 100-1000 replicates) on each gene tree and the species tree to assign statistical support to branches [4].

- For the coalescent species tree, ASTRAL computes a local posterior probability for each branch.

Quantitative Data on Phylogenetic Congruence

The following table summarizes findings from a large-scale study on using universal single-copy orthologs (BUSCOs) for phylogenomics, highlighting how alignment block processing impacts tree quality [3].

Table 1: Impact of Evolutionary Rate and Alignment Construction on Phylogenetic Congruence

| Factor | Condition or Method | Outcome/Effect on Phylogeny | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Site Evolutionary Rate | Use of faster-evolving sites | Higher Taxonomic Congruence | Produced up to 23.84% more taxonomically concordant phylogenies [3]. |

| Site Evolutionary Rate | Use of slower-evolving sites | Higher Terminal Variation | Produced at least 46.15% more variable terminal branches [3]. |

| Tree Inference Method | Concatenation (with fast sites) | High Congruence & Low Variation | Most congruent and least variable phylogenies [3]. |

| Tree Inference Method | Coalescent (ASTRAL) | Comparable Accuracy | Accuracy was comparable to the best concatenation results [3]. |

| Alignment Algorithm | Parameter settings | Significant Impact | Alignments for divergent taxa varied significantly based on parameters used [3]. |

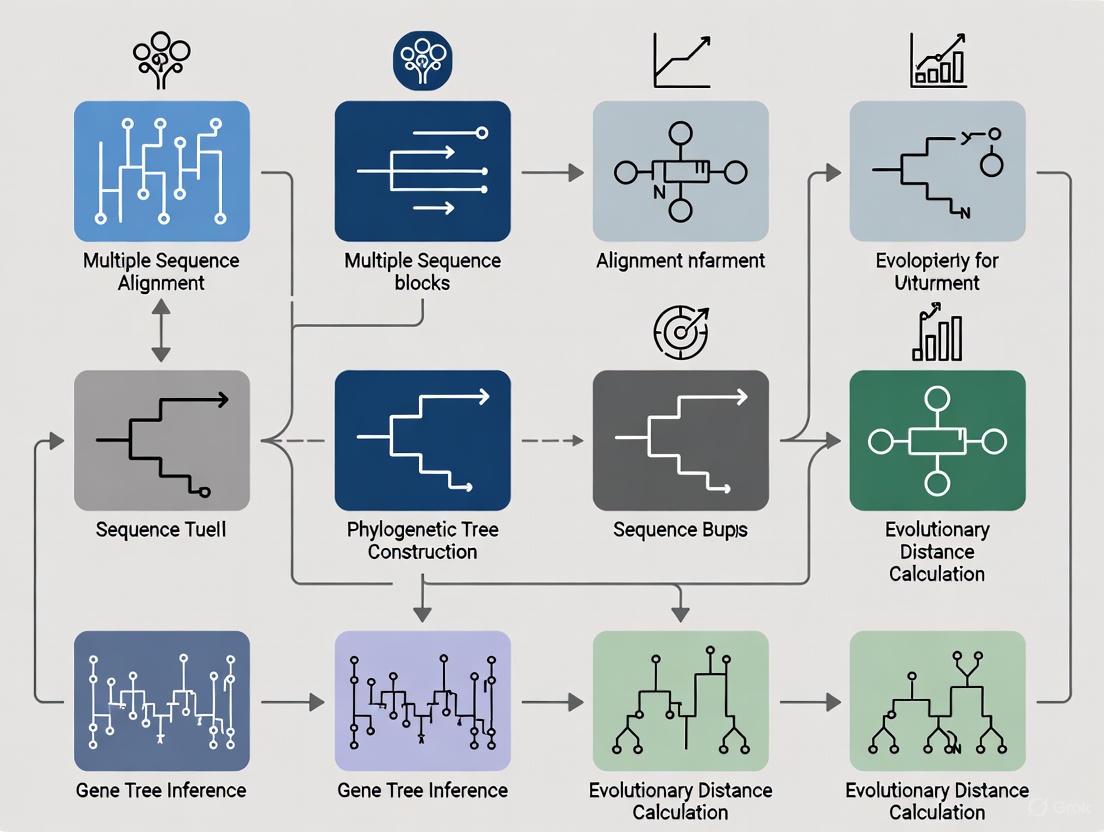

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

From Genomes to a Reliable Species Phylogeny

The diagram below outlines the core workflow for generating a species phylogeny from raw genomic data using alignment blocks.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Software and Data Types for Alignment Block Phylogenetics

| Item Name | Type | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Progressive Cactus | Software | A reference-free whole-genome aligner used to create genome-wide alignments from multiple input assemblies [1]. |

| BUSCO Sets | Data/Software | Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs; used to assess assembly completeness and provide a conserved set of genes for phylogenomics [3]. |

| IQ-TREE | Software | A modern software for maximum likelihood phylogenetic inference. It includes built-in model testing and is efficient for large datasets [1]. |

| ASTRAL | Software | A tool for accurate species tree estimation from a set of gene trees using the multi-species coalescent model, robust to incomplete lineage sorting [1]. |

| PAUP* | Software | A general-utility program for phylogenetic inference, supporting parsimony, likelihood, and distance methods [1]. |

| PhyloNet | Software | Infers species networks (rather than trees) to account for evolutionary processes like hybridization and introgression [1]. |

| MAF File | Data Format | Multiple Alignment Format; a human-readable, reference-based format for storing genome-wide multiple alignments [1]. |

Sequence alignment is a foundational step in most evolutionary and comparative genomics studies. While traditionally focused on matching homologous characters, emerging research demonstrates that the placement of gaps within these alignments carries substantial, and often neglected, phylogenetic signal. This technical guide addresses how to optimize sequence alignment blocks for gene tree inference by leveraging the information embedded in indels (insertions and deletions).

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is gap placement important for phylogenetic inference? Gaps in a sequence alignment are not merely absence of data; they are evolutionary events. Their patterns of insertion and deletion across different lineages carry historical information. Research shows that gaps carry substantial phylogenetic signal, but this signal is poorly exploited by most alignment and tree-building programs [5]. Excluding gaps and variable regions from your analysis is, therefore, detrimental to accuracy [5].

Should I exclude gappy regions from my alignment before tree inference? No. Even though it is a common practice, excluding gappy or variable regions is detrimental to phylogenetic inference because it discards valuable phylogenetic signal contained within these indels [5]. The key is to use alignment and tree-building methods that can properly model and utilize this signal.

How does the choice of alignment program affect gap placement and subsequent tree accuracy? Different alignment programs use distinct algorithms and cost functions to place gaps. However, a key finding is that disagreement among alignment programs says little about the accuracy of the resulting trees [5]. A visually different alignment does not necessarily lead to a different phylogenetic tree. The critical factor is choosing a method whose gap placement leads to more accurate trees, which can be evaluated using phylogeny-based tests [5].

What is the most accurate data type for alignment: nucleotides or amino acids? In general, trees from nucleotide alignments fared significantly worse than those from back-translated amino-acid alignments [5]. The alignment process for amino acids is more accurate. Therefore, for nucleotide sequences, the best results are often obtained by aligning the amino acid sequences and then back-translating them to nucleotides for tree inference [5].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Tree Resolution Despite High-Quality Sequences

Symptoms: Unstable tree topologies, low bootstrap support values, or trees that conflict with established species relationships.

Diagnosis and Solution:

- Investigate Gap Signal: The phylogenetic signal from your gaps may be contradicting or overwhelming the signal from the character substitutions. Use a tree-building method that models indel events.

- Check Alignment Method: Verify that you are not using an alignment program that places gaps in a phylogenetically misleading way. Consider testing multiple aligners.

- Validate with Phylogeny-Based Tests: Evaluate your alignment method using tree-based tests of alignment accuracy. These tests use large, representative samples of real biological data to assess the impact of gap placement on phylogenetic inference [5]. The principle is simple: the more accurate the resulting trees, the more accurate the alignments are assumed to be [5].

Problem: Handling Low-Coverage or Raw Sequencing Data

Symptoms: Difficulty generating reliable alignments and trees directly from raw sequencing reads, especially with low-coverage datasets.

Diagnosis and Solution:

- Bypass Assembly with Read2Tree: For a faster and often more accurate workflow, use tools like Read2Tree, which directly processes raw sequencing reads into groups of corresponding genes [6]. This method bypasses traditional, computationally intensive steps of genome assembly and annotation [6].

- Assess Coverage Impact: Be aware that Read2Tree can maintain high precision in sequence and tree reconstruction even with coverages as low as 0.2x, though recall (completeness) may be lower [6]. It performs well across DNA, RNA, and various sequencing technologies (Illumina, PacBio, ONT) [6].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol: Phylogeny-Based Test for Alignment Accuracy (Species-Tree Discordance Test)

This protocol evaluates alignment accuracy by comparing gene trees inferred from alignments to a known species tree [5].

- Sequence Selection: Sample sets of orthologous genes from species whose phylogeny is well-resolved and undisputed [5].

- Alignment: Generate multiple sequence alignments (MSA) for each gene set using the alignment methods you wish to evaluate.

- Tree Inference: Reconstruct gene trees from each MSA using a consistent method (e.g., Maximum Likelihood with IQ-TREE).

- Comparison: For each resulting gene tree, check for congruence with the known species tree topology.

- Evaluation: The alignment method that produces gene trees most frequently congruent with the species phylogeny is likely the most accurate in terms of homology matching, including gap placement [5].

Protocol: Direct Phylogeny Inference from Raw Reads Using Read2Tree

This protocol outlines a streamlined workflow for inferring phylogenetic trees without genome assembly [6].

- Input: Provide raw sequencing reads (short or long reads) and a set of reference orthologous groups (OGs). Read2Tree uses OGs from the OMA resource by default [6].

- Read Mapping: Align raw reads to the nucleotide sequences of the reference OGs (using Mafft by default) [6].

- Sequence Reconstruction: Within each OG, reconstruct protein sequences from the aligned reads [6].

- Consensus Selection: Retain the best reference-guided reconstructed sequence, using the number of reconstructed nucleotide bases as the primary criterion [6].

- Multiple Sequence Alignment and Tree Inference: Add the selected consensus to the OG's MSA and proceed with conventional tree inference methods (IQ-TREE by default) [6].

Quantitative Comparison of Alignment Methods

The table below summarizes the performance of different alignment strategies based on tree-based tests of accuracy. "Tree-aware" methods like Prank explicitly consider evolutionary history during gap placement.

Table 1: Evaluation of Alignment Program Performance on Phylogenetic Inference [5]

| Alignment Strategy | Representative Programs | Relative Tree Accuracy | Computational Speed | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scoring Matrix-Based | Mafft FFT-NS-2, Muscle, ClustalW2 | Variable | Fast | As a class, did not underperform consistency-based methods; faster. |

| Consistency-Based | Mafft L-INS-i, T-Coffee, ProbCons | Variable | Up to 300x slower | Did not outperform scoring matrix-based methods as a class; performance uneven across datasets. |

| Tree-Aware Gap Placement | Prank | High | Intermediate | Consistently among the best-performing programs for amino-acid data [5]. |

| Nucleotide vs. Amino Acid | Various | Amino acids superior | N/A | Best nucleotide alignments are obtained by back-translating amino-acid alignments. |

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Phylogenetic Analysis with Gaps

| Item | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Read2Tree | Infers phylogenetic trees directly from raw sequencing reads, bypassing assembly. | Ideal for large datasets and low-coverage sequencing; highly versatile for DNA/RNA data [6]. |

| Prank | A multiple sequence alignment program that uses phylogenetic information to guide gap placement. | Classified as "tree-aware"; designed to place gaps in a more evolutionarily realistic manner [5]. |

| OMA (Orthologous Matrix) | Resource for identifying orthologous groups (OGs) of genes across species. | Provides the reference OGs used by the Read2Tree tool [6]. |

| IQ-TREE | Software for maximum likelihood phylogenetic inference. | Commonly used for the final tree-building step from alignments [6]. |

| Phylogeny-based Tests | Methods to assess alignment accuracy by using tree correctness as a surrogate. | Includes species-tree discordance and minimum duplication tests; use real biological data [5]. |

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Integrating gap signal analysis into the standard phylogenetic workflow. The process involves optimizing alignment blocks based on the phylogenetic signal carried by gaps, creating a feedback loop that improves final tree accuracy.

Diagram 2: The Read2Tree workflow for direct phylogeny inference from raw reads, bypassing genome assembly and annotation [6].

Troubleshooting Common Alignment Issues

FAQ: My multiple sequence alignment fails with a "wrong type" or "too long" error. What should I do?

This commonly occurs when using algorithms like MUSCLE or Clustal Omega with sequences that exceed their length capacity or when multi-segment sequence groups are incorrectly ordered [7].

- Solution 1: Use an alternative algorithm. Switch to the Mauve aligner, which is better suited for long sequences [7].

- Solution 2: Use Brenner's Alignment method. This option uses less memory and enables alignment of long, divergent sequences, though with a potential loss of accuracy. It can be activated via alignment options in tools like MegAlign Pro [7].

- Solution 3: Segment your sequences. Break long sequences into shorter, more manageable lengths using tools like DNASTAR SeqNinja [7].

FAQ: How do I choose between a scoring matrix and a consistency-based method for my gene tree inference project?

The choice depends on your data characteristics and research goals. Scoring matrix methods are often faster and well-established, while consistency-based methods generally provide higher accuracy, especially for distantly related sequences [8] [9] [10].

Use Scoring Matrix-Based Methods (e.g., ClustalW) when:

- Working with closely related sequences (e.g., >30% identity).

- Computational speed and resources are a primary concern.

- Aligning nucleotide sequences where simple models (like Levenshtein distance) are sufficient [11].

Use Consistency-Based Methods (e.g., ProbCons, T-Coffee) when:

- Accuracy is the highest priority, particularly with distantly related sequences (<25-30% identity, the "twilight zone") [8] [10].

- Your downstream analysis (like phylogenetic tree construction) is highly sensitive to alignment errors [9].

- You are aligning protein sequences and can leverage information from intermediate sequences to improve pairwise alignments [8].

FAQ: My initial alignment is poor. Can I improve it without starting over?

Yes, post-processing methods can refine alignments without re-running the entire process [12].

- Meta-alignment: Tools like M-Coffee integrate multiple independent MSA results from different programs into a single, more accurate consensus alignment [12].

- Realignment: Tools like RASCAL directly optimize existing alignments by locally adjusting regions with potential errors, such as misplaced gaps [12].

Comparison of Alignment Methods and Scoring Parameters

Table 1: Characteristics of Alignment Approaches

| Feature | Scoring Matrix-Based Methods | Consistency-Based Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Quantifies similarity using a fixed substitution matrix (e.g., BLOSUM62) and gap penalties [11] [13]. | Uses a library of pairwise alignments to create a position-specific scoring scheme that is consistent across all sequences [8] [10]. |

| Typical Use Case | Standard global/local alignment of nucleotides or proteins; faster runs [11]. | Difficult alignments of distantly related sequences; high-accuracy requirements [8] [10]. |

| Key Advantage | Computationally efficient; intuitive parameters [11]. | Generally higher accuracy, especially in the "twilight zone" [8]. |

| Common Algorithms | Needleman-Wunsch (global), Smith-Waterman (local), ClustalW [14]. | ProbCons, T-Coffee, M-Coffee [8] [12]. |

Table 2: Selecting a Protein Scoring Matrix

Different substitution matrices are tuned for different evolutionary distances. This table guides the selection of common matrices based on the target percent identity [13].

| Scoring Matrix | Target % Identity | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|

| BLOSUM80 | ~32% | Closely related sequences [13]. |

| BLOSUM62 | ~28-30% | Standard database searching (BLAST default); a balance of sensitivity and accuracy [11] [13]. |

| BLOSUM50 | ~25% | Sensitive searches for distant relationships; requires longer alignments [13]. |

| PAM70 | ~34% | Alternative for closely related sequences [13]. |

| PAM30 | ~46% | Very closely related sequences [13]. |

Experimental Protocols for Method Comparison

Protocol 1: Evaluating Alignment Accuracy Using a Reference Dataset

This protocol allows researchers to benchmark the performance of different alignment algorithms on their specific data type.

- Obtain a Benchmark Dataset: Use a curated reference dataset with known alignments, such as BAliBASE for proteins [8] [9].

- Generate Alignments: Run your set of unaligned sequences through multiple algorithms (e.g., ClustalW for scoring matrix-based; ProbCons or T-Coffee for consistency-based).

- Compare to Reference: Calculate the accuracy of each generated alignment by comparing it to the reference alignment from the benchmark dataset. Common metrics include the number of correctly aligned columns or the sum-of-pairs score (SPS) [8] [12].

- Analyze Results: Determine which algorithm produces the most biologically accurate alignment for your data. Consistency-based methods often show statistically significant improvement on standard benchmarks [8].

Protocol 2: Integrating Multiple Alignments with M-Coffee

This protocol uses meta-alignment to create a consensus alignment that can be more accurate than any single method [12].

- Generate Input Alignments: Produce multiple independent MSAs of your sequence dataset using different tools and/or parameters (e.g., MUSCLE, MAFFT, ClustalOmega).

- Build Consistency Library: Input all initial alignments into M-Coffee. The tool constructs a library where each aligned residue pair is weighted by its consistency across the different input alignments [12].

- Compute Consensus Alignment: M-Coffee uses the T-Coffee algorithm to generate a final MSA that maximizes the global support from the consensus library [12].

- Validate: Assess the final alignment quality using a scoring function like NorMD, or use it for your downstream phylogenetic analysis [12].

Workflow Visualization

Algorithm Selection Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Software Tools for Sequence Alignment

This table lists essential software tools and libraries used in alignment experiments.

| Tool / Resource | Type | Function |

|---|---|---|

| SeqAn C++ Library [11] | Programming Library | Provides implementations of scoring schemes (simple, substitution matrices) and alignment algorithms (global, local) for custom application development [11]. |

| BLOSUM Matrices [13] | Scoring Matrix | A series of substitution matrices derived from blocks of conserved sequences. BLOSUM62 is the standard for protein BLAST searches [11] [13]. |

| ProbCons [8] | Alignment Algorithm | A progressive alignment tool that uses probabilistic consistency and maximum expected accuracy to achieve high alignment accuracy [8]. |

| T-Coffee / M-Coffee [12] | Alignment & Meta-Alignment Tool | Constructs multiple sequence alignments using consistency-based objective functions (T-Coffee) or by combining results from other aligners (M-Coffee) [12]. |

| MAFFT [12] | Alignment Algorithm | A multiple sequence alignment program known for its speed and accuracy, often used as a component in meta-aligners like AQUA [12]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is reference bias in sequence alignment, and how does it affect my variant calling results? Reference bias occurs when a linear reference genome used in standard analyses does not capture the full genomic diversity of a population. During read alignment, sample reads that differ significantly from the reference may map incorrectly or not at all. This leads to false negative or false positive variant calls, as the process is biased towards the reference allele. This is particularly problematic in highly diverse regions, such as HLA genes, and can impact the accuracy of genotyping and the discovery of structural variants in cancer genomes [15].

Q2: I am constructing gene trees. Should I filter my multiple sequence alignment (MSA) to remove unreliable regions? The decision to filter an MSA for phylogenetic inference requires careful consideration. Empirical studies on large datasets show that while light filtering (removing up to 20% of alignment positions) may have little impact on tree accuracy, aggressive filtering often decreases tree quality. Furthermore, automated filtering can increase the proportion of well-supported but incorrect branches. It is not generally recommended to rely on current automated filtering methods for phylogenetic inference, as the trees from filtered MSAs are on average worse than those from unfiltered ones [16].

Q3: What are some practical solutions to minimize reference bias in my genotyping workflow? Moving beyond a single linear reference genome is the most effective strategy. Two key solutions are:

- Using a graph genome: Representing known population variation as a sequence graph allows reads to map to paths that more closely match their actual sequence, significantly reducing bias [15].

- Using founder sequences: This approach represents known genetic variation with a small set of founder sequences. Reads are aligned to these founders, and the alignments are then projected back to a standard reference. Tools like PanVC 3 implement this method and have been shown to reduce reference bias and improve the precision of calling insertions and deletions (indels) [17].

Q4: How can I assess the accuracy of my multiple sequence alignment? Traditional MSA evaluation methods optimize heuristic scores. However, research indicates that machine-learned scores can correlate more strongly with true alignment accuracy than traditional metrics. These data-driven approaches, trained on simulations where the true alignment is known, offer a more reliable method for selecting among alternative MSAs [18].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Suspected Reference Bias in Variant Calls

Symptoms: Underestimation of alternative alleles at heterozygous sites; consistent missing of variants in highly diverse genomic regions; discrepancies between sequencing and orthogonal validation methods (e.g., Sanger sequencing).

Step-by-Step Diagnostic Protocol:

- Simulate Reads: Use a read simulator like Mason to generate reads from a diploid genome with known heterozygous variants [17].

- Align Reads: Map the simulated reads to your standard linear reference genome using your standard aligner (e.g., Bowtie 2, BWA).

- Generate Pileup: At each known heterozygous variant site, generate a pileup from the alignments. Ensure the site is fully covered by reads.

- Calculate Allelic Ratio: For each site, count the reads supporting the reference allele (R) and the correct alternative allele (A).

- Quantify Bias: Calculate the ratio R/(R+A). In an ideal, unbiased scenario, this ratio should be close to 0.5. A consistent deviation towards 1 indicates significant reference bias [17].

Solution Implementation: Integrate a pangenome approach into your workflow. The following protocol uses the PanVC 3 toolset.

- Workflow Objective: Reduce reference bias by aligning reads to founder sequences.

- Essential Materials:

- A set of known variants (e.g., from a population database).

- The standard linear reference genome (e.g., GRCh37).

- Short-read sequencing data for your sample.

- Procedure:

- Founder Sequence Construction: Generate a small set of founder sequences from the known variants. These sequences minimize recombinations and represent the population diversity [17].

- Read Alignment to Founders: Align your sample's short reads to the set of founder sequences using a standard aligner like Bowtie 2 [17].

- Alignment Projection: Project the resulting alignments from the founder coordinate space back to the coordinate space of your standard reference genome. This step uses a multiple sequence alignment of the founders to the reference [17].

- Recalculate Mapping Qualities: After projection, recalculate mapping quality scores to account for the fact that a read may have aligned equally well to multiple, identical segments of different founder sequences [17].

- Variant Calling: Use the projected alignments and recalculated qualities as input to your standard variant calling pipeline [17].

Problem: Poor Gene Tree Accuracy from MSA

Symptoms: Unstable tree topologies upon resampling; low support values for key branches; trees that conflict with established species phylogenies.

Step-by-Step Diagnostic Protocol:

- Test for Alignment Uncertainty: Use a method like Guidance to assess the sensitivity of your MSA to the alignment guide tree. Identify columns with low confidence scores [16].

- Evaluate Impact of Filtering: If using alignment filtering, repeat your phylogenetic inference on both the unfiltered and filtered MSA. Compare the resulting tree topologies and support values. A significant decrease in support or a biologically implausible result after filtering suggests the filtering may be harmful [16].

- Assess Model Fit: Test whether your phylogenetic model (e.g., site independence) is adequate for your data, as model misspecification can lead to inaccurate trees [18].

Solution Implementation:

- Avoid Aggressive Filtering: If you must filter, do so lightly (e.g., <20% of sites). Prefer methods that account for phylogenetic information, such as Zorro or Guidance, over those based solely on gap content or entropy [16].

- Explore Machine Learning Support: For branch support, consider replacing traditional bootstrapping with machine learning models trained on simulated data. These can provide accurate support values with a clearer probabilistic interpretation and greater computational efficiency [18].

- Use a Disjoint Tree Merger (DTM): For very large datasets, improve accuracy and runtime by using a DTM approach. This involves:

- Dividing your sequence dataset into disjoint subsets.

- Constructing trees on each subset.

- Merging the subset trees into a full tree using a method like ASTRAL. This pipeline can be statistically consistent and improve results [18].

Experimental Data & Protocols

Quantitative Impact of Alignment Filtering on Phylogeny

The table below summarizes findings from a large-scale, systematic comparison of automated filtering methods, demonstrating their impact on single-gene phylogeny reconstruction [16].

| Filtering Method | Average Impact on Tree Topology Accuracy | Effect on Incorrect, Well-Supported Branches | Key Parameter Influencing Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gblocks (default) | Negative | Increases | Minimum block length; treatment of gap positions |

| Gblocks (relaxed) | Negative | Increases | Maximum contiguous nonconserved positions |

| TrimAl | Negative | Increases | Chosen heuristic (gappyout, strict, etc.) |

| Noisy | Negative | Increases | Requires ≥15 sequences for performance |

| Aliscore | Negative | Increases | Sliding window size and randomization test |

| No Filtering | Benchmark (Best) | Lowest | N/A |

Reference Bias Measurement Protocol

This protocol quantifies reference bias in a genotyping workflow, as implemented in a 2024 study [17].

- Objective: Measure the degree of bias towards the reference allele in a genotyping experiment.

- Experimental Input: Simulated reads from a diploid genome (e.g., NA12878 chromosome 1) where the true heterozygous variants are known.

- Procedure:

- Align the simulated reads using the workflow to be tested.

- For each known heterozygous variant site, generate a pileup if the site has a coverage of at least 20x and is fully enclosed by aligned reads.

- Count the number of reads supporting the reference allele (R) and the correct alternative allele (A).

- For each site, calculate the allelic ratio: R/(R+A).

- Data Analysis:

- The ideal allelic ratio for a heterozygous site is 0.5.

- Calculate the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for all sites: MAE = (1/n) * Σ\|xi - 0.5|, where xi is the ratio for each site.

- A lower MAE indicates less reference bias. The study found that the PanVC 3 workflow achieved a lower MAE than alignment to a linear reference with Bowtie 2 or using other graph-based mappers like VG-MAP and Giraffe [17].

Workflow Diagrams

Diagram: Founder Sequence Alignment Workflow for Bias Reduction

Diagram: Gene Tree Inference with MSA Evaluation

Research Reagent Solutions

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Context |

|---|---|---|

| PanVC 3 | Software Toolset | Reduces reference bias by aligning reads to founder sequences and projecting alignments to a linear reference for compatible downstream analysis [17]. |

| Graph Genome (VG/Giraffe) | Software & Data Structure | Captures population diversity in a graph for more accurate read alignment and variant calling, directly addressing reference bias [15]. |

| BWA / Bowtie 2 | Read Alignment Software | Standard tools for mapping short sequencing reads to a linear reference genome; can be used as part of the PanVC 3 workflow for the initial alignment to founders [17]. |

| Founder Sequences | Data Representation | A compact set of sequences that reconstruct known haplotypes with minimal recombinations, enabling scalable pangenome alignment [17]. |

| Machine Learning Models (for MSA/Branch Support) | Computational Method | Provides data-driven scores for evaluating multiple sequence alignments and estimating branch support in phylogenetic trees, potentially outperforming traditional metrics [18]. |

| Disjoint Tree Merger (DTM) | Phylogenetic Pipeline | A divide-and-conquer strategy for estimating large phylogenetic trees with strong statistical guarantees, improving accuracy and runtime [18]. |

From Theory to Practice: Modern Methods for Generating and Refining Alignment Blocks

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the core principle behind using DNA language models for phylogenetics? DNA language models, such as DNABERT, are pretrained using self-supervised learning on massive datasets of biological sequences [19] [20]. They treat DNA sequences as a language, treating nucleotides or k-mers as "words" [20]. The built-in self-attention mechanisms in these Transformer-based models learn to weigh the importance of different nucleotide positions across a sequence [19] [20]. In phylogenetics, these attention scores are used to identify regions that are most informative for distinguishing taxonomic units and inferring evolutionary relationships, eliminating the need for manual marker selection [19].

FAQ 2: My high-attention regions lead to trees with slightly lower accuracy. Is this normal? Yes, this is an expected and documented trade-off. Research with PhyloTune has demonstrated that using automatically extracted high-attention regions can significantly accelerate phylogenetic updates, with only a modest reduction in topological accuracy compared to using full-length sequences [19]. The efficiency gains, which can reduce computational time by 14.3% to 30.3%, often justify this minor compromise, especially for large-scale or rapid analyses [19].

FAQ 3: How do I validate that the attention scores are highlighting biologically meaningful regions? While attention scores identify regions computationally important for taxonomic classification, biological validation is crucial. You should cross-reference the genomic coordinates of your high-attention regions with existing functional annotations. Additionally, you can compare the phylogenetic signal of these regions against traditional, trusted molecular markers or conserved single-copy orthologs (e.g., BUSCO genes) to assess their reliability [3].

FAQ 4: Can this method be applied to large, multi-genome datasets? The method is designed for scalability. For very large datasets, a recommended strategy is to first identify the smallest taxonomic unit (e.g., genus or family) for your new sequence using the fine-tuned language model [19]. Subsequently, you only need to reconstruct the phylogenetic subtree for that specific unit using the high-attention regions, bypassing the need to analyze the entire dataset from scratch and saving substantial computational resources [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Taxonomic Classification of Input Sequences

Problem: The DNA language model fails to correctly identify the smallest taxonomic unit (e.g., genus or family) for a newly sequenced organism, leading to incorrect subtree selection for the phylogenetic update.

Solution:

- Step 1: Verify Data Preprocessing. Ensure your input DNA sequence is clean, free of sequencing artifacts, and is of sufficient length and quality. The model's performance is highly dependent on the quality of the input data.

- Step 2: Check Model Fine-Tuning. The pretrained DNA model must be fine-tuned on a dataset that reflects the taxonomic hierarchy of your target phylogenetic tree [19]. Confirm that your fine-tuning dataset adequately represents the taxa you are working with.

- Step 3: Evaluate Classification Confidence. Implement a confidence threshold for the model's predictions. If the classification probability for all taxa is below a set threshold (e.g., 90%), flag the sequence for manual inspection rather than proceeding with an automatic update.

- Step 4: Manual Curation. For critical or ambiguous cases, use traditional methods like BLAST against a reference database to verify the taxonomic assignment before proceeding [19].

Issue 2: Suboptimal or Noisy Attention Scores

Problem: The attention scores are uniformly distributed across the sequence or highlight regions that are not phylogenetically informative, resulting in poor tree construction.

Solution:

- Step 1: Inspect Attention Weights. Visualize the attention weights from the last layer of the Transformer model across the sequence to check for unusual patterns [19].

- Step 2: Adjust Region Selection Parameters. The process involves dividing sequences into

Kregions and selecting the topMregions with the highest aggregate attention scores [19]. Experiment with different values forKandMto find the optimal balance between data reduction and signal retention for your specific dataset. - Step 3: Consensus Filtering. Use a voting method (e.g., a minority-majority approach) across multiple sequences in the subtree to identify high-attention regions that are consistently important, which helps filter out sequence-specific noise [19].

- Step 4: Cross-Reference with Evolutionary Rates. If possible, compare your high-attention regions with sites in your alignment known to evolve at higher rates, as these have been shown to produce more taxonomically congruent phylogenies in some empirical studies [3].

Issue 3: Integration with Downstream Phylogenetic Tools

Problem: After extracting high-attention sequence regions, the resulting multiple sequence alignment or subsequent tree inference with tools like RAxML or MAFFT produces errors or poor-quality trees.

Solution:

- Step 1: Validate Extracted Sequences. Ensure that the extraction of high-attention regions from the original genome or contig files has been performed correctly and that the resulting sub-sequences are in-frame if coding regions are involved.

- Step 2: Check Alignment Quality. Manually inspect the multiple sequence alignment generated from the high-attention regions. Poor alignments will lead to poor trees, regardless of the signal in the data. Adjust alignment parameters or use alternative algorithms if necessary.

- Step 3: Verify Tree Inference Parameters. Confirm that the evolutionary model and parameters used in maximum likelihood tools (e.g., RAxML-NG) are appropriate for your extracted data. Using an overly complex or simplistic model can affect results.

- Step 4: Assess Tree Support. Always perform bootstrapping or another support value analysis on your final tree. Low support values for key clades may indicate that the selected high-attention regions lack sufficient phylogenetic signal for your specific taxonomic question [4].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fine-Tuning a DNA Language Model for Taxonomic Classification

This protocol adapts a pretrained DNA language model (e.g., DNABERT) to classify sequences within a specific phylogenetic framework [19].

Methodology:

- Data Curation: Compile a curated set of DNA sequences with known taxonomic labels that reflect the hierarchy of your target phylogenetic tree.

- Sequence Tokenization: Input sequences are tokenized into the model's expected format, typically as overlapping k-mers (e.g., 3-mer to 6-mer) [20].

- Model Setup: Start with a pretrained DNA model. Add a hierarchical linear probe (HLP) head for each taxonomic rank (e.g., phylum, class, order, family, genus) you wish to predict [19].

- Fine-Tuning: Train the model on your curated dataset. The self-supervised objective (like Masked Language Modeling) can be combined with supervised loss from the HLP to simultaneously learn general sequence representations and specific classification boundaries [19].

- Validation: Evaluate the model's classification accuracy on a held-out test set of sequences.

Protocol 2: Extracting High-Attention Regions for Subtree Construction

This protocol details the process of identifying and utilizing the most informative parts of sequences for phylogenetic inference [19].

Methodology:

- Sequence Division: For each sequence assigned to a target subtree, divide it into

Kconsecutive, non-overlapping regions of equal length. - Attention Scoring: Pass each sequence through the fine-tuned model. Extract the attention weights from the last Transformer layer. Calculate an aggregate attention score (e.g., mean or max) for each of the

Kregions. - Region Selection: Rank all regions by their aggregate attention score. Select the top

Mregions (whereM<K) from each sequence. To create a consistent alignment block, use a consensus approach (e.g., select regions where the majority of sequences show high attention) [19]. - Data Extraction: Extract the nucleotide sequences corresponding to the selected top

Mregions from all sequences in the subtree. - Phylogenetic Inference: Concatenate the extracted regions to form a new, shorter multiple sequence alignment. Use this alignment as input for standard phylogenetic pipelines (MAFFT for alignment, RAxML-NG for tree inference) to reconstruct the subtree [19].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Phylogenetic Update Strategies

This table summarizes a quantitative comparison of different tree-updating strategies, as demonstrated in PhyloTune experiments [19].

| Number of Sequences (n) | Update Strategy | Normalized RF Distance to Ground Truth | Computational Time (Arbitrary Units) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 40 | Full Tree (Full-Length) | 0.000 | ~100 |

| 40 | Subtree (High-Attention Regions) | 0.000 | ~12 |

| 100 | Full Tree (Full-Length) | 0.027 | ~10,000 |

| 100 | Subtree (Full-Length) | 0.031 | ~85 |

| 100 | Subtree (High-Attention Regions) | 0.031 | ~70 |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Tools

This table lists key software and data resources essential for implementing the described methodology.

| Item Name | Type | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| DNABERT [19] [20] | Software / Pretrained Model | A foundational genomic language model based on the BERT architecture, pretrained on large-scale DNA sequences. It serves as the starting point for fine-tuning. |

| Hierarchical Linear Probe (HLP) [19] | Algorithm | A classification module added to the pretrained model to simultaneously perform novelty detection and taxonomic classification at multiple ranks. |

| MAFFT [19] | Software | A widely used tool for creating multiple sequence alignments from the extracted nucleotide sequences. |

| RAxML-NG [19] | Software | A tool for performing maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic inference on the created alignments. |

| BUSCO Datasets [3] | Data | Benchmarks of Universal Single-Copy Orthologs used for evaluating assembly completeness and as a source of conserved genes for phylogenetic validation. |

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: High-attention phylogenetic update workflow.

Diagram 2: High-attention region extraction process.

This guide provides technical support for researchers extracting sequence alignment blocks from whole-genome alignments (WGAs) for gene tree inference. Sourcing high-quality, recombination-free blocks is crucial for robust phylogenomic analyses and accurately inferring species relationships [1] [21].

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: What defines a "suitable" alignment block for gene tree inference?

A suitable alignment block should meet specific criteria to minimize phylogenetic error:

- High Completeness: Contain sequences for all taxa in your analysis. Blocks with excessive missing data can lead to inaccurate tree topologies [1].

- Adequate Length: Be long enough to be phylogenetically informative (e.g., 1,000 bp as used in one protocol), but not so long that it likely contains multiple recombination breakpoints [1].

- High Information Content: Possess a sufficient number of polymorphic sites to provide resolving power [1].

- Low Recombination Signal: Show minimal evidence of within-alignment recombination, which can create conflicting phylogenetic signals [1] [21].

FAQ 2: My whole-genome alignment contains blocks with variable taxon representation. How should I filter them?

Filtering is a critical step to avoid bias. A practical workflow is:

- Initial Scan: Use command-line tools like

lessor scripts to survey your WGA file (e.g., in MAF format) and understand its structure [1]. - Extraction and Filtering: Employ a custom script to extract blocks of a fixed length while filtering based on:

FAQ 3: Why does my gene tree analysis show conflicting topologies, and how can recombination be the cause?

Conflicting gene trees are a hallmark of phylogenomics and often arise from two biological processes:

- Incomplete Lineage Sorting (ILS): The failure of ancestral gene lineages to coalesce in a population deeper than the most recent speciation event.

- Post-Speciation Introgression (Gene Flow): The transfer of genetic material between two partially isolated species or populations [21].

Recombination interacts with these processes by shuffling genomic regions with different histories. Regions of high recombination are more likely to contain introgressed ancestry, as foreign alleles can be unlinked from negatively selected genes. Conversely, regions of low recombination better preserve the signal of the species tree [21]. Therefore, failing to filter out high-recombination alignment blocks can result in a dataset dominated by conflicting introgression signals.

FAQ 4: How can I practically screen for and remove alignment blocks with high recombination?

After extracting alignment blocks based on completeness, perform a recombination screen:

- Quantify Recombination: Use a recombination detection tool to analyze each extracted alignment block and quantify the strength of recombination signals within it [1].

- Filter Out High-Recombination Blocks: Remove the alignments for which recombination signals are strongest from your dataset. This leaves you with a filtered set of blocks most suitable for inferring the underlying species tree [1].

Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol

Protocol: Extracting and Filtering Alignment Blocks from a Whole-Genome Alignment

This protocol outlines the process of generating a high-quality set of non-recombining alignment blocks from a chromosome-scale WGA for gene tree inference [1].

Objective

To extract multiple sequence alignment blocks of a fixed length from a WGA, then filter them for high completeness and low recombination to produce a final set of alignments for phylogenetic analysis.

Materials and Reagents

- Whole-Genome Alignment File: A reference-based Multiple Alignment Format (MAF) file, generated from a HAL file using a tool like

hal2maf[1]. - Computational Environment: A Unix-based command-line environment (e.g., Amazon AWS instance, Linux server, or local machine).

- Custom Extraction Script: A Python script designed to parse the MAF file, extract blocks, and perform initial filtering.

Workflow Procedure

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow from the initial WGA to a curated set of gene trees:

Step 1: Familiarize with the WGA File

- Navigate to your directory:

cd ~/workshop_materials/27_tree_based_introgression_detection/data[1]. - Examine the MAF file structure using:

less -S cichlids_chr5.maf[1]. - Identify alignment blocks that contain sequences for all your target species. The initial blocks in the file may contain only one or two sequences and are not suitable [1].

Step 2: Extract Alignment Blocks of Fixed Length

- Run the custom Python script to parse the MAF file and extract alignment blocks of a specified length (e.g., 1,000 bp). This script will output each block as a separate sequence alignment file [1].

Step 3: Filter Alignment Blocks for Completeness and Information

- The extraction script should be configured to filter out alignment blocks that do not contain one sequence for every species in your analysis [1].

- Additionally, blocks should be filtered based on their proportion of missing data and the number of polymorphic sites to ensure they are informative [1].

Step 4: Screen for and Filter by Recombination Signal

- Using a recombination detection tool, analyze each extracted alignment block to quantify the frequency of recombination breakpoints or the strength of recombination signals [1].

- Remove the alignment blocks with the strongest recombination signals from your dataset. This step is crucial for retaining genomic regions that best represent the species tree history [1].

Step 5: Generate Gene Trees from Filtered Blocks

- Use the final, filtered set of alignment blocks as input for a phylogenetic inference tool like IQ-TREE to generate a set of gene trees [1].

- This set can then be used in species tree estimation tools like ASTRAL or for detecting introgression via topology frequency analysis [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

The following table details key software solutions required for executing the alignment block extraction and phylogenomic pipeline.

| Software / Tool | Primary Function | Key Application in the Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Progressive Cactus | Reference-free whole-genome alignment | Generating the initial genome-wide comparative dataset [1]. |

| Custom Python Script | Parsing MAF format & block extraction | Automating the extraction of fixed-length alignment blocks from the WGA while applying initial filters [1]. |

| Recombination Detection Tool | Quantifying recombination signals | Identifying and allowing for the removal of alignment blocks with high rates of within-alignment recombination [1] [21]. |

| IQ-TREE | Maximum likelihood phylogenetic inference | Generating individual gene trees from each of the filtered, high-quality alignment blocks [1]. |

| ASTRAL | Species tree estimation from gene trees | Inferring the primary species phylogeny from the set of gene trees generated in the previous step [1]. |

The rapid expansion of genomic data has created an urgent need for automated, accurate, and scalable methods for phylogenetic inference. Traditional phylogenomic pipelines require multiple computationally intensive and error-prone steps, including genome assembly, gene annotation, and orthology detection. Tools like ROADIES and Read2Tree represent a paradigm shift by bypassing these traditional requirements, enabling researchers to infer evolutionary relationships directly from raw genomic data [6] [22] [23]. This technical support center addresses the practical implementation of these tools within research focused on optimizing sequence alignment blocks for gene tree inference.

ROADIES Pipeline Architecture

ROADIES (Reference-free Orthology-free Annotation-free DIscordance-aware Estimation of Species tree) is designed to work from raw genome assemblies to species tree estimation through several automated stages [24]:

- Random Sampling: Configurable numbers of subsequences (genes) are randomly sampled from input genomic assemblies.

- Pairwise Alignment: LASTZ aligns sampled subsequences to all input assemblies to find homologous regions.

- Alignment Filtering: Low-quality alignments are filtered to reduce redundant computation.

- Multiple Sequence Alignment: PASTA performs multiple sequence alignments for homologous regions across species.

- Gene Tree Estimation: RAxML-NG estimates gene trees from multiple sequence alignments.

- Species Tree Estimation: ASTRAL-Pro combines gene trees into a final species tree, accounting for discordance [24] [23].

ROADIES operates in three distinct modes, allowing users to balance accuracy and runtime [24]:

| Mode | Multiple Sequence Alignment | Gene Tree Estimation | Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accurate (Default) | PASTA | RAxML-NG | Accuracy-critical applications |

| Balanced | PASTA | FastTree | Optimal runtime vs. accuracy tradeoff |

| Fast | MashTree (skips MSA) | MashTree | Runtime-critical applications |

Read2Tree Operational Framework

Read2Tree processes raw sequencing reads directly into phylogenetic trees by leveraging reference orthologous groups (OGs) from databases like the Orthologous Matrix (OMA) [6] [25]. Its workflow involves:

- Read Mapping: Raw reads are aligned to nucleotide sequences of reference OGs using Minimap2 [25].

- Sequence Reconstruction: Protein sequences are reconstructed from aligned reads for each OG.

- Consensus Selection: The best reference-guided reconstructed sequence is selected based on the number of reconstructed nucleotide bases.

- Alignment and Tree Inference: Selected consensus sequences are added to OG multiple sequence alignments, and species trees are inferred using IQ-TREE by default [6] [25].

Table: Comparative Overview of ROADIES and Read2Tree

| Feature | ROADIES | Read2Tree |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Input | Raw genome assemblies | Raw sequencing reads (FASTQ) |

| Key Innovation | Random sampling of genomic segments; no reference or orthology needed | Direct mapping of reads to reference orthologous groups |

| Reference Dependency | Reference-free [24] [22] [23] | Requires reference orthologous groups [6] [25] |

| Handles Multi-copy Genes | Yes, via ASTRAL-Pro [24] [23] | Yes, includes paralogs in OGs [6] |

| Typical Applications | Species tree from assembled genomes | Species tree from sequencing reads; works with low-coverage data [6] |

Workflow Diagrams

ROADIES Iterative Species Tree Inference

Read2Tree Reference-Based Assembly-Free Pipeline

Performance and Benchmarking Data

Quantitative Performance Comparisons

Table: ROADIES Performance on Diverse Datasets Data from Guptaa et al. PNAS 2025 and pre-print [22] [23]

| Dataset | Number of Species | Accuracy (vs. Reference) | Speedup vs. Traditional |

|---|---|---|---|

| Placental Mammals | 240 | High agreement with established trees [23] | >176x faster [22] |

| Pomace Flies | 100 | High support for estimated relationships [22] | Significant speedup reported |

| Birds | 363 | High support for estimated relationships [22] | Significant speedup reported |

Table: Read2Tree Performance Under varying Conditions Data from Dylus et al. Nature Biotechnology 2024 [6]

| Condition | Precision (Sequence) | Recall (Sequence) | Tree Reconstruction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Coverage (0.2x) | 90-95% | Lower than high coverage | Maintained high precision |

| RNA-seq Data | Up to 98.5% at 0.2x | Good even at low coverage | Marginal impact from coverage variance |

| Distant Reference | High | Lower than close reference | Maintained high accuracy |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Running ROADIES in Accurate Mode

This protocol details using ROADIES for high-accuracy species tree inference from genome assemblies, suitable for benchmarking studies [24] [26].

Prerequisites and Input

Execution Command

Parameters:

Output Interpretation

Protocol 2: Constructing Trees with Read2Tree

This protocol describes using Read2Tree for phylogeny inference directly from sequencing reads, ideal when genome assembly is impractical [6] [25].

Prerequisites and Input

- Input Data: Raw sequencing reads in FASTQ format.

- Reference OGs: Obtain reference orthologous groups from the OMA browser. A suggested starting point is 200-400 marker genes [25].

- Software Setup: Install Read2Tree from source or via Conda, ensuring dependencies (Minimap2, MAFFT, IQTREE) are available [25].

Execution Command For a single sample:

For multiple samples, run the above command for each sample, then merge:

Parameters:

--standalone_path: Path to directory containing reference OGs.--output_path: Directory for output files.--read_type: Sequencing technology (e.g.,longfor long reads, or Minimap2 preset strings like-ax sr,-ax map-ont).--threads: Number of threads for parallel steps [25].

Output Interpretation

- Primary Output: Concatenated alignment (FASTA) and inferred species tree (with

--treeflag). - Troubleshooting: If runs fail, use the

--debugoption for more detailed logging [25].

- Primary Output: Concatenated alignment (FASTA) and inferred species tree (with

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

ROADIES Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What does the ROADIES convergence mechanism do, and when should I disable it?

A: The convergence mechanism performs multiple iterations, doubling the gene count each time, until branch support stabilizes (minimal percentage change in highly supported nodes). This ensures accuracy but increases runtime. Use --noconverge for faster results on well-established datasets or for initial exploratory analysis [24].

Q: Which operational mode should I choose for my project? A:

- Accurate Mode: For publication-grade results or when analyzing difficult deep phylogenies.

- Balanced Mode: For large-scale analyses where the optimal balance of speed and accuracy is needed.

- Fast Mode: For extremely large datasets or rapid prototyping where approximate trees are sufficient [24].

Read2Tree Frequently Asked Questions

Q: I get an error "[E::main] unknown preset 'sr'" when running with short reads. How do I fix this?

A: This error indicates an outdated version of Minimap2. Update Minimap2 to version 2.30 or newer to ensure support for the short-read preset (-ax sr) [25].

Q: The pipeline fails during tree inference with "[Errno 2] No such file or directory: '...tmp_output.treefile'". What is wrong?

A: This indicates that IQ-TREE did not produce a tree output file, causing a downstream script failure [27]. This can be due to issues with the multiple sequence alignment. Check that:

- The previous alignment steps completed successfully.

- There are no issues with the reference OG sequences.

- Your input reads are of sufficient quality and coverage. Rerunning with

--debugmay provide more specific error information [27] [25].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Software Tools for Alignment-Free Phylogenomics

| Tool / Resource | Function in Pipeline | Key Configuration Notes |

|---|---|---|

| ROADIES | End-to-end species tree inference from assemblies | Select mode based on accuracy/runtime needs; configure gene length and count [24] |

| Read2Tree | End-to-end species tree inference from reads | Ensure reference OGs are appropriate for taxonomic scope; select correct --read_type [25] |

| ASTRAL-Pro | Discordance-aware species tree estimation from gene trees | Handles multi-copy genes; provides local posterior probability branch supports [24] [23] |

| OMA Database | Provides reference orthologous groups for Read2Tree | Curated database of orthologous genes; select number of markers (e.g., 200-400) during download [25] |

| LASTZ | Pairwise alignment for homologous region identification | Used within ROADIES; parameters can be tuned for divergent sequences [24] |

| PASTA | Multiple sequence alignment tool | Used in ROADIES Accurate and Balanced modes for scalable, accurate MSAs [24] |

| Minimap2 | Read mapping for Read2Tree | Must be v2.30+ for short-read presets; --read_type accepts any Minimap2 option string [25] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My BUSCO analysis shows high duplication rates in plants. Is this expected, and how should I handle it? Yes, this is an expected biological phenomenon. Recent research analyzing 11,098 eukaryotic genomes found that plant lineages naturally have a much higher mean BUSCO duplication rate (16.57%) compared to fungi (2.79%) and animals (2.21%). This is often due to ancestral whole genome duplication events [3] [28]. For phylogenetic inference, consider using tools like ASTRAL that are robust to paralogs, or employ tree-based decomposition approaches to extract orthologs from larger gene families [29].

Q2: What are the advantages of using curated BUSCO sets (CUSCOs) over standard BUSCO? Curated BUSCO sets (CUSCOs) provide up to 6.99% fewer false positives compared to standard BUSCO searches by accounting for pervasive ancestral gene loss events that lead to misrepresentations of assembly quality [3] [28]. CUSCOs attain higher specificity for 10 major eukaryotic lineages by filtering out genes with lineage-specific loss patterns.

Q3: How does missing data affect phylogenomic inferences with BUSCO genes? Systematic analysis reveals that representation of orthologs can vary significantly across taxa. Tools like TOAST enable visualization of missing data patterns and allow users to reassemble alignments based on user-defined acceptable missing data levels [30]. For reliable inference, establish thresholds that balance data inclusion with taxonomic representation.

Q4: Which substitution models perform best with BUSCO-derived phylogenies? For BUSCO concatenated alignments, variations of the LG (Le-Gascuel) and JTT (Jones-Taylor-Thornton) substitution models with different rate categories consistently show the highest likelihood scores across diverse lineages [3] [28]. Model selection should be validated using Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) for your specific dataset.

Troubleshooting Guides

Unexpectedly Low BUSCO Completeness

Problem: BUSCO assessment reports unusually low completeness scores for otherwise high-quality assemblies.

Solution:

- Check lineage-specific patterns: Consult databases of BUSCO statistics across taxonomic groups; 215 groups significantly vary from their respective lineages in BUSCO completeness [3].

- Investigate gene loss: Use the phyca software toolkit to identify pervasive ancestral gene loss events that may cause false positives [3] [28].

- Consider CUSCOs: Switch to Curated BUSCO sets (CUSCOs) for your specific lineage to reduce false positives from lineage-specific gene loss [3].

Verification: Compare your results with the public database of BUSCO statistics for 11,098 eukaryotic genomes to determine if your scores align with taxonomic expectations [3].

Excessive Gene Duplication in BUSCO Output

Problem: BUSCO reports high duplication percentages, complicating ortholog identification.

Solution:

- Validate biological reality: 169 taxonomic groups display significantly elevated duplicated BUSCO complements, often from ancestral whole genome duplication events [3] [28].

- Use decomposition methods: Implement tree-based decomposition approaches (e.g., DISCO, LOFT) to extract orthologs from larger gene families rather than restricting to single-copy clusters [29].

- Consider all gene families: Recent research shows using all gene families vastly expands data available for phylogenetics while maintaining accuracy [29].

Verification: Check if duplication rates correlate with assembly ploidy or known whole genome duplication events in your study system.

Poor Phylogenetic Resolution or Incongruence

Problem: BUSCO-derived trees show poor resolution or conflict with established taxonomy.

Solution:

- Select optimal sites: Sites evolving at higher rates produce up to 23.84% more taxonomically concordant phylogenies with at least 46.15% less terminal variability [3] [28].

- Compare methods: Both concatenated and coalescent trees from BUSCO data have comparable accuracy, but higher-rate sites from concatenated alignments typically produce the most congruent phylogenies [3].

- Assemble appropriate datasets: For closely-related species, use syntenic BUSCO metrics that offer higher contrast and better resolution than standard BUSCO searches [3].

Verification: Test for taxonomic congruence by comparing with NCBI taxonomic classifications for 275 suitable families [3].

BUSCO Performance Metrics Across Major Lineages

Table 1: BUSCO Characteristics Across Major Eukaryotic Groups

| Lineage | Mean BUSCO Completeness | Mean Duplication Rate | Taxonomic Groups with Significant Variation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plants | Near-complete in majority assemblies | 16.57% | 215 groups across all lineages show significant variation in completeness |

| Fungi | Near-complete in majority assemblies | 2.79% | Includes microsporidia with <25% BUSCO genes |

| Animals | Near-complete in majority assemblies | 2.21% | Elevated duplications in specific families (e.g., Backusellaceae: 12.18%) |

Table 2: Phylogenetic Performance of BUSCO Sites by Evolutionary Rate

| Site Category | Taxonomic Concordance | Terminal Variability | Recommended Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Higher-rate sites | Up to 23.84% more congruent | At least 46.15% less variable | Divergent taxa, deep phylogenies |

| Lower-rate sites | Less congruent | Higher terminal variability | Recently diverged lineages |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assembling BUSCO Phylogenies with Optimal Site Selection

Purpose: Reconstruct taxonomically congruent phylogenies using BUSCO genes.

Materials: phyca software toolkit [3], genomic assemblies, appropriate BUSCO lineage dataset.

Procedure:

- Compile dataset: Obtain genomic assemblies for your target taxa.

- Run BUSCO analysis: Use BUSCO with lineage-specific datasets.

- Identify optimal sites: Select sites evolving at higher rates using phyca.

- Generate alignments: Create concatenated alignments focusing on higher-rate sites.

- Phylogenetic inference: Implement both concatenated (LG/JTT models) and coalescent approaches.

- Assess congruence: Test trees against taxonomic classifications.

Validation: Verify taxonomic congruence with established NCBI taxonomy [3].

Protocol 2: Implementing CUSCOs for Improved Assembly Assessment

Purpose: Reduce false positives in assembly quality assessment.

Materials: CUSCO gene sets for your lineage [3], phyca software.

Procedure:

- Download CUSCOs: Obtain curated BUSCO sets for your specific lineage.

- Replace standard BUSCO: Use CUSCOs in place of standard BUSCO analysis.

- Run assessment: Perform standard BUSCO workflow with CUSCO gene sets.

- Compare results: Note reduction in false positives (up to 6.99%).

- Implement syntenic metrics: For closely-related assemblies, use syntenic BUSCO metrics for higher resolution.

Validation: Compare results with standard BUSCO output to quantify improvement [3].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for BUSCO-Based Phylogenomics

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| phyca software toolkit [3] | Reconstructs consistent phylogenies, precise assembly assessments | General BUSCO analysis, CUSCO implementation |

| TOAST R package [30] | Automates ortholog alignment assembly from transcriptomes | Transcriptomic data, missing data visualization |

| ASTRAL [29] | Species tree inference robust to paralogs | Analyzing datasets with gene duplication |

| Tree-based decomposition methods (DISCO, LOFT) [29] | Extract orthologs from larger gene families | Expanding beyond single-copy orthologs |

| BUSCO public database [3] | Reference BUSCO statistics across 11,098 genomes | Comparative assessment of results |

Workflow Visualization

BUSCO Phylogenomics Workflow

BUSCO Data Processing Pathway

Solving Common Pitfalls: Strategies for Optimizing Alignment Blocks Amidst Real-World Data Challenges

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: How does low-coverage sequencing truly impact my ability to find genuine genetic variants?

Low-coverage whole-genome sequencing (lcWGS), when combined with a robust imputation strategy, can recall true genetic variants (high precision and recall) almost as effectively as high-density SNP arrays, and in some cases, even surpass them. One study found that haplotype reconstructions from lcWGS were highly concordant with those from the GigaMUGA array, with over 90% of local expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs) being recalled even at coverages as low as 0.1× [31]. The key is a high-quality reference panel for imputation, which can lead to imputation accuracies exceeding 0.98 [32].

FAQ 2: My sequencing coverage is uneven. Will this create biases in my phylogenomic analyses?

Yes, uneven coverage and the resulting missing data can significantly bias phylogenomic analyses. Variations in universal single-copy ortholog (BUSCO) completeness across taxonomic groups are a known issue. These variations, influenced by evolutionary history such as ancestral gene loss or whole-genome duplication events, can lead to misrepresentations of assembly quality and, consequently, confound phylogenetic inferences [3]. It is crucial to account for these biases in your analysis.

FAQ 3: What is a more cost-effective method for genotyping a large population: SNP arrays or low-coverage WGS?

For large-scale studies, low-coverage WGS is increasingly recognized as a cost-effective alternative to SNP arrays. While arrays are expensive and subject to ascertainment bias, lcWGS provides a less biased view of genetic variation and can capture novel variants. A study in pigs concluded that lcWGS is a cost-effective alternative, providing improved accuracy for genomic prediction and genome-wide association studies compared to chip data [32].

FAQ 4: When analyzing classification results from genomic data, should I use a ROC curve or a Precision-Recall curve?

The choice depends on the balance of your classes. ROC curves are appropriate when the observations are balanced between each class. They plot the True Positive Rate (Sensitivity) against the False Positive Rate. Precision-Recall curves are more appropriate for imbalanced datasets. They summarize the trade-off between the true positive rate and the positive predictive value for a model using different probability thresholds [33].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Poor Recall of True Variants in Low-Coverage Sequencing Data

- Symptoms: An unusually high number of false negatives; known variants from validation datasets are not being called; low statistical power in association studies.

- Causes:

- Inadequate sequencing depth leading to a high rate of missing genotypes.

- Suboptimal imputation strategy or a poor-quality reference panel.

- Failure to filter or pre-process raw sequencing data effectively.

- Solutions:

- Optimize Imputation Strategy: Do not rely on self-imputation alone. Use a reference panel composed of key progenitors or founders from your population. One study found that using a reference panel of 30 key progenitors (

Ref_LGstrategy) yielded the highest imputation accuracy (0.9899) for pig lcWGS data, outperforming other strategies [32]. - Implement Rigorous QC: Before alignment and variant calling, always perform quality control on your raw FASTQ files. Use tools like FastQC to check for base quality, adapter contamination, and overrepresented sequences. Poor-quality reads should be trimmed using tools like Trimmomatic [34].

- Validate with a Subset: If resources allow, sequence a subset of your samples to high coverage (e.g., >15x) to create a population-specific reference panel, which can then be used to impute the remaining low-coverage samples [32].

- Optimize Imputation Strategy: Do not rely on self-imputation alone. Use a reference panel composed of key progenitors or founders from your population. One study found that using a reference panel of 30 key progenitors (

Problem 2: Low Precision and False Positive Variant Calls

- Symptoms: An excess of rare or novel variants that are difficult to validate; high rate of heterozygosity; variants clustering in specific genomic regions without biological rationale.

- Causes:

- Alignment errors, particularly in complex or repetitive regions of the genome.

- Inadequate base-calling accuracy or model.

- Contamination in the sample or library preparation.

- Solutions:

- Leverage Advanced Basecallers: If using nanopore sequencing, select the most accurate basecalling model available. The "super accuracy" (SUP) model is recommended for de novo assembly and low-frequency variant analysis, as raw read accuracy can now exceed 99.75% (Q26) with the latest chemistry and models [35].

- Use the Correct Reference Genome: Ensure you are using the correct version of the reference genome (e.g., GRCh38/hg38 for human) and that it has been properly indexed for your aligner. A mismatch can cause widespread misalignments [34].

- Check for Contamination: Use tools to check for cross-species or environmental contamination in your sequence data, which can manifest as an abnormal number of novel variants.

Problem 3: Inconsistent or Incorrect Phylogenetic Tree Topologies

- Symptoms: Poorly supported nodes; trees that conflict with established taxonomic classifications; high terminal variability.

- Causes:

- Missing data and uneven gene representation across taxa.

- Use of alignment sites with inappropriate evolutionary rates.

- Inadequate phylogenetic model selection.

- Solutions:

- Curate Your Ortholog Set: To mitigate false positives from undetected gene loss, use a curated set of universal orthologs (CUSCOs). One study showed this can provide up to 6.99% fewer false positives compared to a standard BUSCO search [3].

- Select Informative Sites: For broad phylogenies, sites evolving at higher rates have been shown to produce more taxonomically congruent phylogenies (up to 23.84% more) and significantly less terminal variability (at least 46.15% less) compared to slower-evolving sites [3].