qPCR vs ddPCR: A Strategic Guide for Antibiotic Resistance Gene Quantification in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qPCR) and Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) for the detection and quantification of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs), a critical task in...

qPCR vs ddPCR: A Strategic Guide for Antibiotic Resistance Gene Quantification in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qPCR) and Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) for the detection and quantification of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs), a critical task in public health and pharmaceutical research. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of both technologies, their practical application in complex sample matrices like wastewater and biosolids, and strategies for troubleshooting and optimization. By synthesizing recent comparative studies, the content offers validated insights to guide method selection, enhance data accuracy in ARG surveillance, and support the development of effective antimicrobial strategies.

Understanding the Core Technologies: From qPCR Quantification to ddPCR's Digital Partitioning

{#topic#}

The Evolution of PCR: From Conventional to Quantitative (qPCR) and Digital (dPCR)

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) has revolutionized molecular biology since its inception, evolving from a conventional tool for nucleic acid amplification into sophisticated quantitative technologies. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) and digital PCR (dPCR) represent significant milestones in this evolution, each offering distinct advantages for specific applications. In the critical field of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) research, the choice between qPCR and dPCR for antibiotic resistance gene (ARG) quantification profoundly impacts the sensitivity, accuracy, and interpretation of surveillance data. This application note delineates the operational characteristics of both platforms, provides a structured comparative analysis, and details optimized protocols for their application in ARG quantification, particularly within complex environmental matrices such as wastewater.

Technology Comparison: qPCR vs. dPCR

Fundamental Principles and Workflows

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) monitors the amplification of DNA in real-time using fluorescence, with the cycle at which fluorescence crosses a threshold (Cq) being proportional to the starting quantity of the target nucleic acid. This method relies on standard curves for relative or absolute quantification [1] [2]. In contrast, digital PCR (dPCR) employs a limiting dilution approach, partitioning a single PCR reaction into thousands of nanoreactions. Each partition is individually analyzed post-amplification as positive or negative for the target, enabling absolute quantification without the need for standard curves by applying Poisson statistics [1] [2] [3].

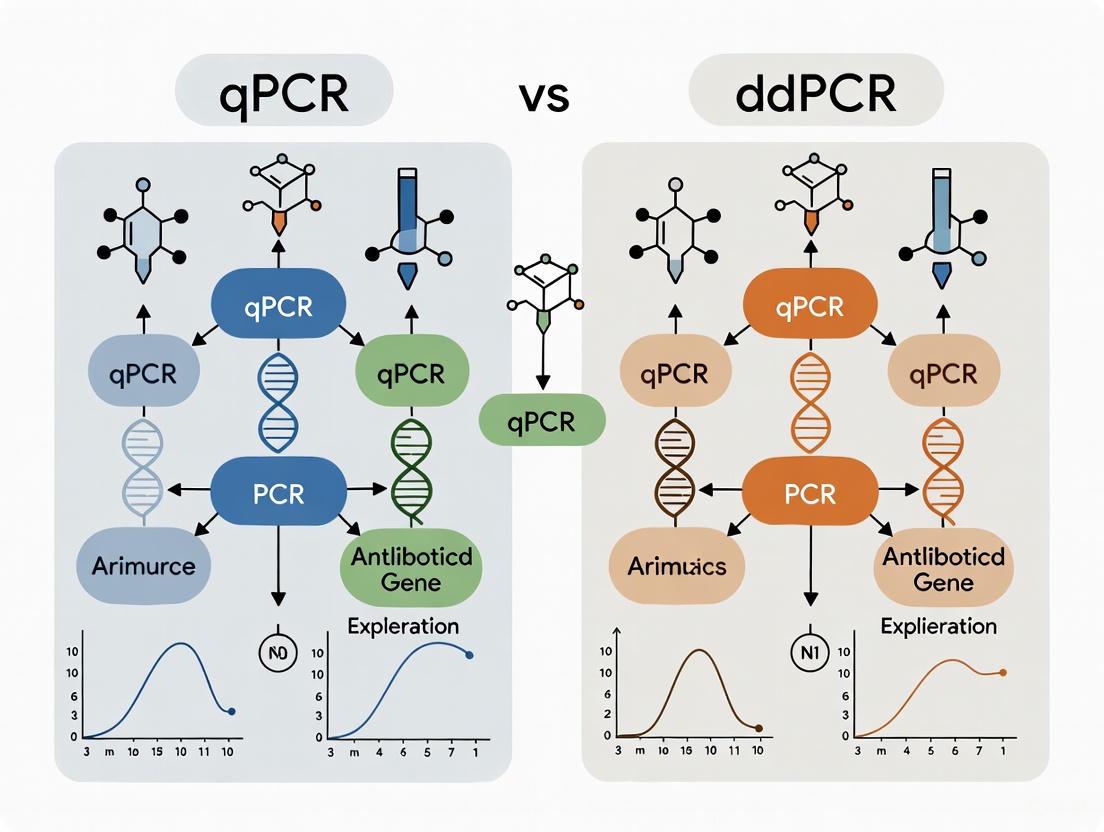

The following workflow diagrams illustrate the key procedural differences between these two technologies for ARG detection.

Diagram 1: qPCR workflow for ARG detection. The process relies on real-time fluorescence monitoring and requires a standard curve for quantification [1] [2].

Diagram 2: dPCR workflow for ARG detection. The method uses partitioning and endpoint detection to achieve absolute quantification without a standard curve [1] [3].

Performance Characteristics for ARG Quantification

The selection between qPCR and dPCR is application-dependent. The following table summarizes their comparative performance characteristics, particularly relevant for ARG quantification in environmental samples.

Table 1: Comparative analysis of qPCR and dPCR for ARG quantification.

| Parameter | Quantitative PCR (qPCR) | Digital PCR (dPCR) |

|---|---|---|

| Quantification Type | Relative (requires standard curve) or absolute [1] | Absolute, without standard curves [1] [4] |

| Precision (Coefficient of Variation) | ~5.0% CV [4] | ~2.3% CV (higher precision) [4] |

| Detection of Low Abundance Targets | Mutation rate detection ≥1% [1] | Mutation rate detection ≥0.1% [1]; More precise for low-fold changes [1] [5] |

| Tolerance to PCR Inhibitors | Susceptible to inhibitors in complex samples [1] [6] | High tolerance; robust in complex matrices like wastewater [1] [6] |

| Dynamic Range | Broad dynamic range [1] | Broad dynamic range, but can be saturated at very high concentrations [3] |

| Throughput and Speed | High-throughput, well-established fast protocols [1] | Traditionally lower throughput, but newer nanoplate systems are faster [1] |

| Cost Per Sample | Lower cost [2] | Higher cost, especially for consumables [2] |

For ARG surveillance, dPCR demonstrates superior performance in scenarios requiring high sensitivity and precision, such as detecting low-abundance resistance genes in environmental samples [7] [5]. Its robustness to inhibitors common in wastewater [6] and ability to absolutely quantify targets like sul2 and tetW without standards make it ideal for cross-laboratory comparisons [7]. Conversely, qPCR remains a powerful and cost-effective tool for high-throughput screening where extreme sensitivity is not the primary requirement [1] [8].

Application in Antibiotic Resistance Gene Quantification

Side-by-Side Protocol for ARG Detection in Wastewater

The following protocols are optimized for the detection and quantification of ARGs (e.g., sul2, tetW) in wastewater samples, a key reservoir for antimicrobial resistance dissemination [8] [7].

Sample Collection and Nucleic Acid Extraction

- Sample Collection: Collect wastewater samples (e.g., 50 mL influent) in sterile containers. Transport on ice and process within 24 hours [6] [9].

- Concentration: Centrifuge samples at 3,000–4,000 × g for 15-30 minutes to pellet solids. Alternatively, use vacuum filtration through 0.22 µm polyethersulfone (PES) membranes [6] [7].

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Extract DNA from the pellet or filter using a kit designed for complex environmental samples (e.g., DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit, QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit). Include a bead-beating step for efficient cell lysis [9] [7].

- Optional Step (for dPCR): While dPCR is more tolerant, further purification can be performed using spin-column based clean-up kits to remove potent inhibitors [6].

- DNA Quantification and Quality Control: Measure DNA concentration using a fluorometer. Verify DNA integrity by electrophoresis or by amplifying a ubiquitous control gene (e.g., 16S rRNA).

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) Protocol

Reaction Setup:

- Prepare a master mix for each reaction as follows [8] [6]:

- 10 µL of 2X TaqMan Environmental Master Mix

- 1.8 µL each of forward and reverse primer (10 µM)

- 0.5 µL of probe (10 µM)

- Nuclease-free water to a final volume of 18 µL

- Add 2 µL of template DNA (or standard) to each well for a total reaction volume of 20 µL.

- Run all samples and standards in triplicate.

- Prepare a master mix for each reaction as follows [8] [6]:

Standard Curve Preparation:

- Prepare a serial dilution (e.g., 10-fold) of a known quantity of the target gene (e.g., gBlock fragment or linearized plasmid). A minimum of 5 dilution points is recommended [6].

Thermocycling Conditions (Run on a real-time PCR instrument) [8]:

- Enzyme Activation: 95°C for 10 min

- 40–45 Cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 15 sec

- Annealing/Extension: 60°C for 1 min (acquire fluorescence)

Data Analysis:

- Determine Cq values for each sample.

- Generate a standard curve from the dilution series (Cq vs. log10 starting quantity).

- Calculate the target concentration in unknown samples by interpolating from the standard curve. Express results as gene copies per µL of DNA extract or normalized to 16S rRNA gene copies [8].

Digital PCR (dPCR) Protocol

Reaction Setup:

- Prepare a master mix for each reaction as follows [7] [3]:

- 11 µL of 2X ddPCR Supermix for Probes (or QIAcuity PCR Master Mix)

- 1.8 µL each of forward and reverse primer (10 µM)

- 0.5 µL of probe (10 µM)

- Nuclease-free water and template DNA to a final volume of 22 µL.

- The optimal amount of template DNA should be determined empirically but is typically 1-10 ng/µL.

- Prepare a master mix for each reaction as follows [7] [3]:

Partitioning and Thermocycling:

- Droplet-based Systems (e.g., Bio-Rad QX200): Generate droplets using a droplet generator. Transfer the emulsified sample to a 96-well PCR plate. Seal the plate [10] [3].

- Nanoplate-based Systems (e.g., QIAGEN QIAcuity): Pipette the reaction mix directly into the designated wells of a nanoplate. The instrument performs partitioning automatically [1] [3].

- Run the PCR with the following recommended conditions [10]:

- Enzyme Activation: 95°C for 10 min

- 40 Cycles of:

- Denaturation: 94°C for 30 sec

- Annealing/Extension: 58–60°C for 1 min

- Enzyme Deactivation: 98°C for 10 min

- Note: Ramp rates should be specified as slow (2°C/sec) for droplet stability in droplet-based systems.

Data Analysis:

- Read the plate or droplets on the respective instrument.

- Use the manufacturer's software to analyze the fluorescence amplitude of each partition and apply a threshold to distinguish positive from negative events.

- The software will apply Poisson correction to calculate the absolute concentration in copies/µL of the reaction mix [1] [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key reagents and materials for ARG quantification using qPCR and dPCR.

| Item | Function/Description | Example Products |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | For isolating high-quality DNA from complex wastewater matrices; kits with inhibitor removal steps are critical. | DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit (Qiagen), AllPrep PowerViral DNA/RNA Kit (Qiagen) [9] [7] |

| PCR Master Mix | Contains DNA polymerase, dNTPs, buffer, and salts. Probe-based mixes are standard for qPCR and dPCR. | TaqMan Environmental Master Mix (qPCR), ddPCR Supermix for Probes (Bio-Rad), QIAcuity PCR Master Mix (Qiagen) [6] [3] |

| Primers & Probes | Sequence-specific oligonucleotides for amplifying and detecting target ARGs (e.g., sul2, tetW). Must be validated for efficiency and specificity. | Custom-designed assays; validated primers from literature [8] [7] |

| Standard Curves (for qPCR) | Known quantities of the target gene for generating the calibration curve essential for qPCR quantification. | gBlock Gene Fragments (IDT), plasmid DNA [6] |

| Digital PCR Plates/Consumables | Disposable items for sample partitioning. | DG8 Cartridges and Droplet Generation Oil (Bio-Rad ddPCR), QIAcuity Nanoplate (Qiagen) [1] [3] |

| Nuclease-free Water | A critical reagent to prevent degradation of reaction components. | Various molecular biology grade suppliers |

The evolution from qPCR to dPCR provides researchers with powerful, complementary tools for tackling the global challenge of antimicrobial resistance. The choice between them for ARG quantification hinges on the specific requirements of the study. qPCR remains the workhorse for high-throughput, cost-effective screening where extreme sensitivity is not paramount. In contrast, dPCR excels in applications demanding absolute quantification, superior precision, and enhanced sensitivity for low-abundance targets, and is notably more robust when analyzing inhibitor-rich complex samples like wastewater. As both technologies continue to advance, their synergistic use will undoubtedly deepen our understanding of the abundance and flux of antibiotic resistance genes within One Health frameworks.

Relative quantification using standard curves is a foundational method in quantitative PCR (qPCR) that enables researchers to measure gene expression levels relative to a control sample. This technique provides a robust framework for comparing transcript abundance across different experimental conditions without requiring absolute molecular counts. Within antibiotic resistance gene (ARG) research, this approach facilitates the assessment of how environmental factors influence resistance gene expression in bacterial populations. This application note details the experimental workflow, calculation methods, and implementation considerations for relative quantification using standard curves, with specific application to ARG quantification in complex matrices.

Relative quantification in qPCR determines the change in gene expression in a test sample relative to a reference sample, often an untreated control or calibrator [11]. This method does not yield absolute copy numbers but provides a fold-change value representing how much more or less a target gene is expressed in experimental conditions compared to control conditions [12].

The standard curve method for relative quantification involves creating dilution series of a reference DNA or cDNA sample to establish a relationship between cycle threshold (Ct) values and relative template quantities [11]. For all experimental samples, the target quantity is determined from the standard curve and divided by the target quantity of the calibrator, making the calibrator the 1× sample and all other quantities expressed as an n-fold difference relative to the calibrator [11].

This approach is particularly valuable in ARG research where investigators frequently examine how antibiotic exposure in various environments (wastewater, soil, clinical settings) upregulates or downregulates resistance gene expression without requiring knowledge of the absolute number of ARG copies present.

Experimental Design and Workflow

Key Terminology and Concepts

Table 1: Essential Nomenclature for Relative Quantification

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Calibrator Sample | Reference sample (e.g., untreated control) against which all test samples are compared |

| Target Gene | Gene of interest (e.g., an antibiotic resistance gene) |

| Reference Gene | Stable endogenous control gene (e.g., housekeeping gene) used for normalization |

| Amplification Efficiency (E) | Efficiency of PCR amplification for a specific primer set, calculated from the standard curve slope |

| Cycle Threshold (Ct) | PCR cycle at which fluorescence exceeds a defined threshold |

| Normalized Target Value | Target quantity divided by endogenous reference quantity |

Complete Experimental Protocol

RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis

- Extract total RNA from bacterial samples using appropriate isolation methods. For environmental samples like wastewater or biosolids, incorporate additional purification steps to remove PCR inhibitors [13].

- Treat with DNase to remove genomic DNA contamination [14].

- Synthesize cDNA using reverse transcriptase with random hexamers or gene-specific primers.

- Include a "no RT control" for each reverse transcription reaction to identify signal from genomic DNA contamination [14].

Standard Curve Preparation

- Create a stock solution of cDNA from a reference sample (e.g., pool of all samples).

- Prepare serial dilutions (typically 5-10 points) in a 10-fold or 2-fold dilution series [12].

- Use the same dilution scheme for both target and reference genes to maintain consistent relative quantities.

qPCR Reaction Setup

- Prepare master mix containing buffer, dNTPs, polymerase, and appropriate fluorescence detection chemistry (SYBR Green or TaqMan probes) [14].

- Add primers at optimized concentrations. For ARG targets, ensure specificity through careful primer design and validation [15].

- Distribute reactions into appropriate plate or tube format.

- Load standard curve dilutions in duplicate or triplicate.

- Load experimental samples in at least three technical replicates to minimize pipetting errors [14].

- Include no-template controls (NTC) for each primer pair to monitor contamination [14].

Thermal Cycling Conditions

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 2-5 minutes

- Amplification cycles (40-45 cycles):

- Denaturation: 95°C for 10-30 seconds

- Annealing: Primer-specific temperature (55-65°C) for 20-30 seconds

- Extension: 72°C for 20-30 seconds

- Fluorescence acquisition at the end of each annealing or extension step

Data Analysis and Calculation Methods

Standard Curve Analysis

- Plot Ct values of the standard dilutions against the logarithm of their relative concentration or dilution factor.

- Calculate slope of the regression line through the standard points.

- Determine amplification efficiency for each primer set using the formula: Ideal amplification efficiency (100%) corresponds to a slope of -3.32 [12].

- Check correlation coefficient (R²) of the standard curve; values >0.98 indicate good linearity.

Relative Quantification Calculations

The relative quantification using the standard curve method applies the following steps:

- Determine target quantity for each experimental sample from the target gene standard curve.

- Determine reference quantity for each experimental sample from the reference gene standard curve.

- Calculate normalized target value for each sample:

- Calculate relative expression for each test sample relative to the calibrator:

This calculation generates a fold-change value where:

- RQ = 1 indicates no change in expression

- RQ > 1 indicates upregulation in the test sample

- RQ < 1 indicates downregulation in the test sample [11]

Application in Antibiotic Resistance Gene Research

Experimental Considerations for ARG Quantification

When applying relative quantification to ARG research, several matrix-specific factors must be addressed:

- Inhibition Management: Environmental samples like wastewater, biosolids, and soil contain PCR inhibitors that affect amplification efficiency. Include dilution series of representative samples to assess inhibition effects [13].

- Reference Gene Selection: Validate reference genes for stability in specific experimental conditions. Common bacterial reference genes include 16S rRNA, though stability should be verified under experimental conditions [12].

- Sample Collection and Preservation: Stabilize RNA immediately after collection to preserve accurate expression profiles, especially for time-course studies of ARG induction.

Comparison of qPCR and ddPCR for ARG Research

Table 2: Technology Comparison for ARG Quantification

| Parameter | qPCR with Standard Curves | ddPCR |

|---|---|---|

| Quantification Basis | Relative to standard curve and calibrator | Absolute counting of molecules |

| Inhibition Tolerance | Moderate; requires efficiency correction [16] | High; partitioning reduces inhibitor effects [13] [16] |

| Detection Limit | Moderate; depends on standard curve quality and efficiency | Higher sensitivity for low-abundance targets [13] [15] |

| Precision at High CN | Decreases due to efficiency assumptions [17] | Maintains precision across copy number range [17] |

| Throughput | High | Moderate |

| Data Interpretation | Requires multiple controls and normalization | Direct absolute quantification without standards |

| Best Applications | High-throughput screening, expression fold-changes | Low-abundance targets, complex matrices, absolute copy number [13] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Relative Quantification

| Reagent/Category | Function and Importance |

|---|---|

| Reverse Transcriptase | Converts RNA to cDNA for expression analysis; critical for RNA viruses and gene expression studies |

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Reduces non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation; improves assay specificity and efficiency |

| Fluorescent Detection Chemistry | SYBR Green (intercalating dye) or TaqMan probes (sequence-specific); enables real-time monitoring of amplification |

| Primer/Probe Sets | Target-specific oligonucleotides; must be validated for specificity and efficiency [14] |

| Reference Gene Assays | Pre-validated assays for stable reference genes; essential for accurate normalization |

| Inhibition Resistance Additives | Enhances polymerase resistance to inhibitors in complex matrices (e.g., wastewater, soil) |

| Nuclease-Free Water | Prevents enzymatic degradation of nucleic acids and reaction components |

Quality Control and Troubleshooting

Implementing MIQE Guidelines

Adherence to the Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments (MIQE) guidelines ensures experimental rigor and reproducibility [18]. Key requirements include:

- Complete documentation of sample handling, storage, and nucleic acid extraction methods

- Validation of amplification efficiency for each primer set, not assumed

- Assessment of RNA integrity and DNA contamination controls

- Clear reporting of statistical methods and biological/technical replicates

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Poor Standard Curve Linear Range:

- Check dilution accuracy and pipetting technique

- Verify template quality and absence of inhibitors

- Ensure appropriate dynamic range coverage

Variable Amplification Efficiencies:

- Redesign primers if efficiency falls outside 90-110%

- Optimize annealing temperature and reagent concentrations

- Check for primer-dimer formation and non-specific amplification

High Variation Between Replicates:

- Improve pipetting technique and use calibrated equipment

- Ensure thorough mixing of reaction components

- Check for well-to-well temperature variation in thermal cycler

Relative quantification using standard curves remains a widely accessible and robust method for assessing gene expression changes in ARG research. While emerging technologies like ddPCR offer advantages for absolute quantification in complex matrices, the standard curve method provides sufficient sensitivity and precision for many research applications, particularly when implemented with appropriate controls and validation. The continued utility of this approach depends on rigorous experimental design, adherence to quality control standards, and appropriate interpretation of results within the technical limitations of the method.

Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) is a third-generation polymerase chain reaction technology that enables the absolute quantification of nucleic acid target sequences without the need for a standard curve. This represents a significant advancement over quantitative PCR (qPCR), which relies on relative quantification based on external calibrators [15] [19]. The core innovation of ddPCR lies in its partitioning technology, where a single PCR reaction is divided into thousands to millions of nanoliter-sized droplets, creating individual reaction chambers that collectively function as a digital array [20]. Each droplet acts as an independent PCR microreactor containing zero, one, or a few target DNA molecules. Following end-point amplification, droplets are analyzed individually using a flow-cytometry based system that counts the positive (fluorescent) and negative (non-fluorescent) droplets [19]. The fundamental digital readout—simply whether amplification occurred or not in each partition—enables precise calculation of the target concentration in the original sample using Poisson distribution statistics [15] [21].

This partitioning approach provides ddPCR with exceptional capabilities for detecting rare targets and making precise measurements even in the presence of PCR inhibitors, addressing key limitations of qPCR technology [22] [5]. In the context of antibiotic resistance gene (ARG) research, these attributes make ddPCR particularly valuable for environmental samples where target concentrations may be low and inhibitors are frequently present [15]. The absolute quantification capability of ddPCR eliminates inter-laboratory variability associated with standard curve preparation in qPCR, potentially leading to more reproducible results across different research settings—a critical consideration for surveillance studies tracking the dissemination of antibiotic resistance determinants across human, animal, and environmental compartments [15] [21].

Fundamental Principles of ddPCR

Sample Partitioning and End-Point Detection

The ddPCR workflow begins with the partitioning of a conventional PCR mixture—containing template DNA, primers, probes, and master mix—into approximately 20,000 nanoliter-sized water-in-oil droplets [20]. This partitioning is typically achieved through microfluidic technology that generates uniform droplets at a consistent volume. The enormous number of discrete partitions effectively dilutes the sample components, with most droplets containing either zero or a single target molecule based on Poisson distribution principles [15]. Following droplet generation, the entire emulsion undergoes standard PCR amplification to end-point, unlike qPCR which monitors amplification in real-time. This end-point detection is a critical differentiator, as it eliminates dependence on amplification efficiency and cycle threshold (Cq) values that can vary between samples in qPCR [5] [23].

After thermal cycling, each droplet is analyzed individually in a droplet reader that measures fluorescence intensity. The reader flows the droplets in a single file past a optical detection system that classifies each droplet as positive or negative for the target sequence based on fluorescence thresholds [19]. The binary readout (positive/negative) from thousands of individual reactions provides the digital data that enables absolute quantification. This partitioning and digital counting approach makes ddPCR particularly robust against factors that typically affect PCR efficiency, as minor variations in amplification efficiency between samples do not affect the fundamental yes/no determination for each droplet [5].

Poisson Statistics and Absolute Quantification

The mathematical foundation of ddPCR quantification relies on Poisson distribution statistics, which model the random distribution of target DNA molecules across thousands of discrete partitions. The proportion of negative droplets (those without target DNA) follows Poisson statistics, allowing calculation of the original target concentration using the formula:

[ \lambda = -\ln(1 - p) ]

Where λ represents the average number of target molecules per droplet and p is the proportion of positive droplets [19]. The absolute concentration in the original sample (in copies/μL) is then calculated as:

[ \text{Concentration} = \frac{\lambda \times \text{total number of droplets}}{\text{droplet volume} \times \text{sample volume used}} ]

This direct mathematical approach eliminates the need for standard curves and external calibrators that are essential for qPCR quantification [19] [21]. The reliance on Poisson statistics rather than comparative quantification makes ddPCR particularly valuable for absolute measurements of antibiotic resistance genes, especially when reference materials are not standardized or available [15]. The precision of ddPCR measurements increases with the number of partitions analyzed, with commercial systems typically generating sufficient droplets for highly accurate quantification across a wide dynamic range [20].

Comparative Performance: ddPCR vs. qPCR

Sensitivity and Detection Limits

Multiple studies have demonstrated that ddPCR provides superior sensitivity compared to qPCR, particularly for low-abundance targets. In the context of antibiotic resistance gene research, this enhanced sensitivity is crucial for detecting rare resistance determinants in complex environmental samples. A comparative study of ddPCR and qPCR for detecting lactic acid bacteria reported that ddPCR showed a 10-fold lower limit of detection than qPCR, making it more sensitive for quantifying bacterial targets at low concentrations [24]. Similarly, research on 'Candidatus Phytoplasma solani' detection found ddPCR sensitivity to be approximately 10-fold higher than standard qPCR methodologies [22]. This pattern was confirmed in a comprehensive comparison of qPCR, dPCR and ddPCR for mitochondrial DNA quantification, where both digital methods showed lower limits of detection and quantification than qPCR, with ddPCR consistently demonstrating lower variation among replicates [25].

The partitioning technology of ddPCR enhances sensitivity by effectively concentrating rare targets into individual droplets, thereby increasing the effective template concentration in positive partitions while reducing background noise. This makes ddPCR particularly valuable for environmental surveillance of emerging antibiotic resistance genes where early detection of low-abundance targets can provide critical insights into resistance dissemination pathways [15]. Furthermore, the ability to detect rare targets makes ddPCR suitable for monitoring the effectiveness of interventions aimed at reducing antibiotic resistance prevalence in various environments.

Precision, Reproducibility, and Tolerance to Inhibitors

ddPCR demonstrates significantly improved precision and reproducibility compared to qPCR, especially for targets present at low concentrations. A study comparing the reliability and accuracy of qPCR, dPCR and ddPCR found that ddPCR consistently showed lower variation among replicates when analyzing samples with low abundance targets [25]. This enhanced precision stems from the digital nature of the readout and the large number of replicate reactions (thousands of droplets) analyzed per sample. The Poisson-based statistical analysis also provides built-in quality control, as the ratio of positive to negative droplets must fall within an acceptable range for precise quantification [19].

Another significant advantage of ddPCR is its superior tolerance to PCR inhibitors commonly found in environmental samples. Research on water quality assessment demonstrated that ddPCR was less affected by PCR inhibitors present in various sample matrices compared to qPCR [21]. This robustness was further confirmed in plant pathogen detection studies, where ddPCR was not affected by inhibitors that significantly impacted qPCR performance [22]. The enhanced tolerance to inhibitors arises from the partitioning process, which effectively dilutes inhibitory substances across thousands of droplets, thereby reducing their local concentration and minimizing interference with amplification in individual partitions [19] [21]. This characteristic is particularly beneficial for antibiotic resistance gene research involving complex sample matrices such as wastewater, sediment, and fecal samples that typically contain multiple PCR inhibitors.

Table 1: Comparative Performance Characteristics of qPCR and ddPCR

| Parameter | qPCR | ddPCR |

|---|---|---|

| Quantification Method | Relative (requires standard curve) | Absolute (Poisson statistics) |

| Detection Limit | ~10 copies/reaction [24] | ~1-3 copies/reaction [24] [22] |

| Precision with Low Targets | Higher variability (CV > 20%) [25] | Lower variability (CV < 10%) [25] |

| Tolerance to Inhibitors | Moderate [22] [21] | High [22] [21] |

| Dynamic Range | 5-6 logs [19] | 4-5 logs [19] |

| Multiplexing Capability | Well-established | Emerging with newer systems [20] |

ddPCR Protocol for Antibiotic Resistance Gene Quantification

Sample Preparation and DNA Extraction

For antibiotic resistance gene quantification in environmental samples, proper sample collection and DNA extraction are critical steps that significantly impact ddPCR results. Sample types relevant to ARG research include wastewater, surface water, sediment, soil, and biological specimens from human or animal sources. Consistent collection and preservation methods should be employed throughout a study to minimize technical variability. DNA extraction should be performed using kits optimized for the specific sample matrix, with special attention to removing PCR inhibitors common in environmental samples [15]. While ddPCR is more tolerant of inhibitors than qPCR, their complete removal is still desirable for optimal performance. For limited samples or low bacterial loads, a crude lysate protocol can be employed as an alternative to traditional DNA extraction. This approach has been successfully used for rare target quantification from as few as 200 cells, eliminating DNA extraction steps that can lead to target loss [26].

The quality and quantity of extracted DNA should be assessed using spectrophotometric or fluorometric methods. However, it is important to note that these measurements provide information about total DNA concentration but not the specific presence of target ARG sequences. For ddPCR, precise quantification of DNA input is less critical than for qPCR because of the absolute quantification nature of ddPCR, but consistent input across samples is recommended for comparative studies. When working with limited sample material, dilution series may be necessary to determine the optimal template concentration for ddPCR analysis [23].

Droplet Generation and PCR Amplification

The ddPCR reaction mixture is similar to conventional qPCR assays but requires optimization of probe and primer concentrations for optimal droplet separation. A typical 20-μL reaction volume for ARG detection might contain:

- 10 μL of 2× ddPCR Supermix (commercial formulation)

- 1.8 μL of forward and reverse primers (final concentration 900 nM each)

- 0.5 μL of probe (final concentration 250 nM)

- 2-5 μL of template DNA

- Nuclease-free water to 20 μL

After thorough mixing and brief centrifugation, the reaction mixture is loaded into a droplet generator cartridge along with droplet generation oil. The droplet generator partitions each sample into approximately 20,000 nanoliter-sized droplets through a water-in-oil emulsion process [20]. The resulting emulsion is carefully transferred to a 96-well PCR plate, sealed, and placed in a thermal cycler. The thermal cycling conditions are similar to qPCR protocols but with a ramp rate typically limited to 2°C/second to maintain droplet integrity. A standard thermal profile includes:

- Enzyme activation: 95°C for 10 minutes

- 40 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 94°C for 30 seconds

- Annealing/Extension: 55-60°C for 60 seconds (gene-specific)

- Enzyme deactivation: 98°C for 10 minutes

- Hold: 4°C indefinitely

Following amplification, the plate containing the stabilized droplets is transferred to a droplet reader for analysis [19].

Droplet Reading and Data Analysis

The droplet reader processes each sample well individually, aspirating the droplet emulsion and flowing it in a single stream past a two-color optical detection system. The reader measures fluorescence intensity in each droplet and classifies it as positive or negative based on user-defined thresholds. Data analysis software then applies Poisson statistics to calculate the absolute concentration of the target ARG in the original sample, expressed as copies/μL [19].

Threshold setting is a critical step in ddPCR data analysis. The software typically provides automated threshold determination, but manual adjustment may be necessary for optimal separation between positive and negative droplet populations. Samples with very low target concentrations (<3 copies/μL) may require replicate measurements or increased sample volume to improve quantification accuracy. For absolute quantification of ARGs, results can be normalized to sample volume or mass, or expressed as gene copies per cell if simultaneous quantification of a reference gene is performed [15] [23].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for ddPCR-based ARG Quantification

| Reagent Type | Specific Examples | Function in ddPCR |

|---|---|---|

| ddPCR Supermix | Bio-Rad ddPCR Supermix for Probes | Provides optimized reaction buffer, dNTPs, and polymerase for droplet-based amplification |

| Hydrolysis Probes | FAM, HEX/VIC-labeled TaqMan probes | Sequence-specific detection with fluorescent signal release upon amplification |

| Primer Sets | Custom-designed ARG-specific primers | Amplify target antibiotic resistance gene sequences |

| Droplet Generation Oil | Bio-Rad Droplet Generation Oil | Creates stable water-in-oil emulsion for sample partitioning |

| Positive Controls | Synthetic gBlocks for ARG targets | Validate assay performance and efficiency |

| Sample Lysis Buffers | Ambion Cell-to-Ct buffer, SuperScript IV buffer | Prepare crude lysates from limited samples without DNA extraction [26] |

Applications in Antibiotic Resistance Gene Research

Absolute Quantification of ARG Burden

ddPCR provides distinct advantages for absolute quantification of antibiotic resistance genes across various environments. Unlike qPCR, which offers relative quantification dependent on standard curves, ddPCR directly measures ARG copy numbers in environmental samples, enabling more accurate comparisons across different studies and locations [15]. This absolute quantification capability is particularly valuable for establishing baseline ARG levels in different environments and tracking temporal changes in resistance gene abundance in response to interventional strategies or environmental perturbations.

The precision of ddPCR at low target concentrations makes it suitable for monitoring rare or emerging resistance determinants that may be present at minimal levels but have significant clinical implications if they proliferate. Additionally, the ability to perform absolute quantification without reference standards simplifies multi-laboratory surveillance studies, as it eliminates variability associated with standard curve preparation and implementation across different research settings [15] [21]. This standardization potential is crucial for large-scale monitoring programs aimed at understanding the dissemination dynamics of antibiotic resistance across human, animal, and environmental compartments.

Detection of Rare Targets and Genetic Variants

The partitioning technology of ddPCR enhances detection sensitivity for rare antibiotic resistance genes present in complex microbial communities. By effectively concentrating scarce targets into individual droplets, ddPCR can identify resistance determinants that would be undetectable against background DNA using conventional qPCR [5]. This capability is particularly relevant for early detection of emerging resistance mechanisms and for understanding the initial stages of resistance gene transfer and dissemination in environmental settings.

ddPCR also facilitates the detection and quantification of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with antibiotic resistance. The digital nature of the assay enables precise measurement of variant frequencies within mixed populations, providing insights into the dynamics of resistance development during antibiotic exposure [15]. This application has significant potential for monitoring the evolution of resistance in clinical and agricultural settings, where minor variant populations may represent the early emergence of resistant strains that eventually dominate the microbial community.

Critical Technical Considerations

Optimization Strategies and Quality Control

Successful implementation of ddPCR for antibiotic resistance gene quantification requires careful optimization of several technical parameters. Primer and probe concentrations must be optimized to ensure efficient amplification while maintaining clear separation between positive and negative droplet populations. This typically involves testing a range of primer (100-900 nM) and probe (50-250 nM) concentrations to identify conditions that maximize fluorescence amplitude in positive droplets while minimizing background in negative droplets [5]. Template DNA concentration should be adjusted to maintain the number of target molecules per droplet within the optimal range (approximately 0.5-4 copies/droplet) to avoid saturation effects that can impair accurate quantification [23].

Quality control measures are essential for generating reliable ddPCR data. Each run should include no-template controls to monitor contamination and positive controls to verify assay performance. For multiplex assays, compensation between fluorescence channels must be optimized to account for spectral overlap [20]. Droplet generation should be visually inspected to ensure uniform droplet formation, and data analysis should include assessment of droplet count per sample to identify any technical issues with partitioning. Samples generating fewer than 10,000 droplets should be repeated to ensure statistical robustness of the quantification [19].

Limitations and Complementary Technologies

Despite its advantages, ddPCR has limitations that researchers must consider when designing antibiotic resistance gene studies. The dynamic range of ddPCR (typically 4-5 orders of magnitude) is narrower than that of qPCR (5-6 orders of magnitude), which may require sample dilution for targets present at high concentrations [19]. The throughput of ddPCR systems, while improving, generally remains lower than qPCR platforms, particularly for high-throughput screening applications. Additionally, the requirement for specialized equipment and reagents makes ddPCR more costly per sample than conventional qPCR, which may be a consideration for large-scale surveillance studies [15].

For comprehensive ARG profiling, ddPCR is often used in conjunction with other molecular methods. While ddPCR provides highly accurate quantification of specific target genes, high-throughput qPCR or next-generation sequencing approaches may be better suited for initial screening of diverse resistance determinants in environmental samples [15]. The combination of these technologies—using broad-spectrum screening methods to identify targets of interest followed by precise ddPCR quantification of priority ARGs—represents a powerful approach for antibiotic resistance surveillance that leverages the complementary strengths of different platforms.

Droplet Digital PCR represents a significant advancement in nucleic acid quantification technology, with particular relevance for antibiotic resistance gene research. Its partitioning approach combined with Poisson statistics enables absolute quantification of target genes without standard curves, providing higher precision for low-abundance targets and greater tolerance to PCR inhibitors compared to qPCR. These characteristics make ddPCR particularly valuable for environmental ARG monitoring, where target concentrations may be low and sample matrices complex. While ddPCR has limitations in dynamic range and throughput, its unique capabilities make it an important tool in the molecular methods arsenal for combating the global spread of antibiotic resistance. As the technology continues to evolve with improved multiplexing capabilities and workflow efficiency, ddPCR is poised to play an increasingly important role in surveillance studies tracking the dissemination of resistance determinants across diverse environments.

In the field of molecular biology, the accurate quantification of nucleic acids is fundamental for advanced research, including the surveillance of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs). Quantitative PCR (qPCR) and droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) represent two pivotal technologies in this domain, each with distinct technical profiles. This application note provides a detailed comparison of qPCR and ddPCR, focusing on the core differentiators of sensitivity, dynamic range, and precision. The information is framed within the context of ARG quantification research, offering structured experimental data, detailed protocols, and visual workflows to guide researchers and drug development professionals in selecting the optimal methodological approach for their specific applications.

Technical Comparison: qPCR vs. ddPCR

Table 1: Comparative Performance of qPCR and ddPCR across Key Technical Parameters

| Parameter | qPCR / Real-Time RT-PCR | ddPCR / dPCR |

|---|---|---|

| Quantification Method | Relative (ΔΔCq); requires a standard curve [1] [27] | Absolute (copies/μL); no standard curve needed [1] [27] |

| Sensitivity (Limit of Detection) | Best for moderate-to-high abundance targets (Cq < 30-35) [28] | Superior for low-abundance targets; can detect down to 0.17-0.5 copies/μL input [3] [28] |

| Dynamic Range | Broad dynamic range [1] [28] | Broad, but may oversaturate at very high concentrations (>3000 copies/μL) [3] |

| Precision | Good for mid/high expression levels and >twofold changes [28] | Higher precision; reliable detection of |

| Tolerance to PCR Inhibitors | Susceptible; inhibitors affect Cq values and efficiency, requiring dilution [1] [5] | High tolerance; robust performance in the presence of inhibitors due to endpoint detection [1] [27] [21] |

| Multiplexing Capability | Requires extensive validation for matched amplification efficiency [28] | Simplified multiplexing with minimal optimization [29] [28] |

| Best Use Cases | Gene expression analysis (moderate/high targets), pathogen detection with broad dynamic range [1] [28] | Absolute quantification, rare target detection, copy number variation, detecting subtle fold changes (<2-fold) [1] [5] [28] |

Table 2: Experimental Results from Cross-Platform Performance Studies

| Application / Study | Key Finding (qPCR) | Key Finding (ddPCR/dPCR) | Reference / Model System |

|---|---|---|---|

| ARG & Microbe Quantification | - | Linear trend with cell numbers; higher precision with optimized restriction enzymes (e.g., HaeIII) [3] | Paramecium tetraurelia; QX200 & QIAcuity [3] |

| Plant Pathogen Detection | Broader dynamic range [27] | Significantly higher sensitivity; lower coefficient of variation (CV), especially at low target concentration [27] | Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri [27] |

| Respiratory Virus Detection | - | Superior accuracy for high viral loads (Influenza A/B, SARS-CoV-2) and medium loads (RSV); greater consistency [30] | Clinical samples; QIAcuity [30] |

| Limit of Quantification (LOQ) | - | LOQ determined at 4.26 copies/μL input (85.2 copies/reaction) [3] | Synthetic oligonucleotides; QX200 ddPCR [3] |

| Limit of Quantification (LOQ) | - | LOQ determined at 1.35 copies/μL input (54 copies/reaction) [3] | Synthetic oligonucleotides; QIAcuity ndPCR [3] |

Experimental Protocols for ARG Quantification

Protocol: Quantifying ARG Abundance using ddPCR

This protocol is adapted from studies on city-scale monitoring of antibiotic resistance genes [31].

1. Sample Collection and DNA Extraction

- Sample Collection: Collect water samples from relevant hot-spots (e.g., hospital wastewater, wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) input and output). For example, filter 10 mL of wastewater through a 0.2 μm filter to capture the prokaryotic fraction [31].

- DNA Extraction: Perform nucleic acid extraction using a commercial kit (e.g., MasterPure Complete DNA and RNA Purification Kit or DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit) according to the manufacturer's instructions [31]. Elute DNA in a suitable buffer and quantify.

2. ddPCR Reaction Setup

- Primers/Probes: Use validated primer-probe sets for the target ARGs (e.g., sul2 for sulfonamide resistance and tetW for tetracycline resistance) [31].

- Reaction Mix: Prepare a 25 μL reaction mixture containing:

- 10 μL of ddPCR supermix (e.g., Bio-Rad ddPCR Supermix for Probes).

- Forward and reverse primers at optimized concentrations (e.g., 900 nM each).

- Fluorescently labeled probe (e.g., FAM) at an optimized concentration (e.g., 250 nM).

- 5 μL of template DNA (adjust volume based on DNA concentration).

- Nuclease-free water to 25 μL [27] [31].

3. Droplet Generation and PCR Amplification

- Droplet Generation: Load the reaction mixture into a DG8 cartridge along with droplet generation oil. Generate droplets using a droplet generator (e.g., Bio-Rad QX200 Droplet Generator) [27].

- PCR Amplification: Transfer the generated droplets to a 96-well PCR plate. Seal the plate and perform PCR amplification on a thermal cycler using the following example conditions:

- Enzyme activation: 95°C for 10 minutes.

- 40 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 94°C for 30 seconds.

- Annealing/Extension: 60°C for 60 seconds.

- Enzyme deactivation: 98°C for 10 minutes.

- Note: Use a ramp rate of 2°C/second for all steps [27].

4. Droplet Reading and Data Analysis

- Droplet Reading: Place the PCR plate in a droplet reader (e.g., Bio-Rad QX200 Droplet Reader) which measures the fluorescence in each droplet [27].

- Data Analysis: Use the manufacturer's software (e.g., QuantaSoft) to analyze the data. The software will apply Poisson statistics to the count of positive and negative droplets to provide an absolute concentration of the target ARG in copies/μL of the original reaction [27] [31].

Protocol: Assessing ARG Mobility Potential via Multiplexed ddPCR

This protocol is based on a novel method for quantifying the physical linkage between an ARG and a mobile genetic element [29].

1. DNA Shearing and Sample Preparation

- DNA Shearing: Mechanically shear the environmental DNA to a defined fragment size of approximately 20,000 base pairs. This step is critical to reduce false-positive detection of linkage and control for the statistical probability of two unlinked genes residing on the same DNA fragment by chance [29].

- Control DNA: Prepare control DNA fragments with known linkage status (100% linked, e.g., from a linearized plasmid; and 0% linked, e.g., a mixture of individual PCR amplicons of the two targets) [29].

2. Duplex ddPCR Reaction Setup

- Primers/Probes: Design two probe-based assays, each with a different fluorophore (e.g., FAM for the ARG, HEX for the mobile genetic element marker, such as the intI1 integrase gene) [29].

- Multiplex Reaction: Prepare the ddPCR reaction mix as in Protocol 3.1, but include both primer-probe sets in a single well [29].

3. Droplet Generation, Amplification, and Reading

- Follow the same steps for droplet generation, PCR amplification, and droplet reading as described in Protocol 3.1 [29].

4. Linkage Analysis

- The droplet reader will classify droplets into four populations: double-negative, FAM-positive (ARG only), HEX-positive (mobility marker only), and double-positive (linked ARG and marker).

- The frequency of double-positive droplets is used to calculate the percentage of ARG copies that are physically linked to the mobility marker in the original sample, using statistical analysis and Poisson correction [29].

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Experimental Workflow for ARG Analysis

Technology Selection Logic

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for dPCR-based ARG Research

| Item | Function / Application | Example Kits / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kit | Isolation of high-quality DNA from complex environmental samples (e.g., wastewater). | MasterPure Complete DNA and RNA Purification Kit [31]; DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit [31]. |

| dPCR Supermix | Chemical milieu for PCR amplification, optimized for droplet formation and stability. | Bio-Rad ddPCR Supermix for Probes [27]. |

| Primer-Probe Assays | Target-specific amplification and detection. | Validated assays for ARGs (e.g., sul2, tetW) and mobility markers (e.g., intI1) [29] [31]. |

| Droplet Generation Oil | Creates the water-in-oil emulsion necessary for partitioning the sample. | Bio-Rad Droplet Generation Oil for Probes [27]. |

| Restriction Enzymes | Digests DNA to improve accessibility to target sites, which can enhance precision [3]. | E.g., HaeIII, EcoRI. Choice of enzyme can impact results [3]. |

| Positive Control Plasmids | Assay validation and as a process control. | Linearized plasmids containing the target ARG sequence [29] [27]. |

The Growing Imperative for Accurate ARG Surveillance in a One Health Framework

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) poses a critical global health threat, with antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) disseminating freely across human, animal, and environmental compartments. This silent pandemic necessitates robust surveillance strategies that can accurately quantify ARG abundance and mobility potential. Effective monitoring within a One Health framework requires molecular tools that are not only sensitive and quantitative but also applicable to complex environmental matrices such as wastewater and biosolids, which are recognized as significant ARG reservoirs and hotspots for horizontal gene transfer [13] [32].

The selection of appropriate methodological approaches is paramount for generating reliable and comparable data. This application note provides a comparative analysis of two key quantification technologies—quantitative PCR (qPCR) and droplet digital PCR (ddPCR)—and presents detailed protocols for their application in ARG surveillance. We focus on practical implementation, from sample concentration to data analysis, to support researchers in selecting the optimal methodology for their specific One Health surveillance objectives.

Comparative Technology Analysis: qPCR vs. ddPCR

The core of effective surveillance lies in selecting the appropriate detection technology. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) and Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) are both cornerstone techniques for ARG quantification, but they possess distinct principles, strengths, and limitations as shown in the table below.

Table 1: Comparison of qPCR and ddPCR Technologies for ARG Surveillance

| Feature | Quantitative PCR (qPCR) | Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Measures fluorescence at the exponential amplification phase (Cycle threshold, Ct) [15]. | Partitions sample into nanoliter droplets for endpoint PCR; uses Poisson statistics for absolute quantification [13] [15]. |

| Quantification | Relative, requires a standard curve [15]. | Absolute, does not require a standard curve [33] [15]. |

| Sensitivity | Lower, detection limits ~1 copy/10⁵-10⁷ genomes [34]. | Higher, capable of detecting rare targets and copy number variations; limits as low as 1.6 copies per reaction reported [35] [33]. |

| Tolerance to Inhibitors | Susceptible to PCR inhibitors from complex matrices, leading to underestimated concentrations [13] [15]. | Highly tolerant due to sample partitioning, which dilutes inhibitors [13] [35]. |

| Optimal Use Cases | High-throughput screening where absolute quantification is not critical; samples with minimal inhibitors. | Quantifying low-abundance ARGs; analyzing complex, inhibitor-rich environmental samples; applications requiring high precision [13] [35]. |

Performance varies significantly by sample matrix. A 2025 study demonstrated that in wastewater, ddPCR showed greater sensitivity than qPCR, whereas in biosolid samples, both methods performed similarly, though ddPCR detection was slightly weaker [13] [36]. This underscores the importance of considering matrix characteristics when choosing a detection method.

Application Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for key procedures in ARG surveillance, from sample concentration to assessing ARG mobility.

Protocol A: Sample Concentration from Treated Wastewater

Efficient concentration is critical for detecting low-abundance ARGs in aqueous environmental samples. Two common methods are Filtration-Centrifugation and Aluminum-based Precipitation [13].

Table 2: Comparison of ARG Concentration Methods for Wastewater

| Step | Filtration-Centrifugation (FC) Method | Aluminum-Based Precipitation (AP) Method |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Volume | 200 mL | 200 mL |

| Procedure | 1. Filter through 0.45 µm membrane.2. Place filter in buffered peptone water, agitate, and sonicate.3. Centrifuge sequentially at 3,000 × g and 9,000 × g.4. Resuspend final pellet in 1 mL PBS. | 1. Adjust sample pH to 6.0.2. Add AlCl₃ (1:100 v/v) and shake at 150 rpm for 15 min.3. Centrifuge at 1,700 × g for 20 min.4. Reconstitute pellet in 3% beef extract, shake, and centrifuge again.5. Resuspend final pellet in 1 mL PBS. |

| Key Advantage | - | Provides higher ARG concentration yields, especially in wastewater [13] [36]. |

| Storage | Concentrated samples should be frozen at -80°C until DNA extraction. |

Protocol B: DNA Extraction from Complex Matrices

This protocol is suitable for concentrated wastewater samples and biosolids [13].

- Lysis: Use 300 µL of concentrated sample or PBS-resuspended biosolids. Add 400 µL of CTAB (Cetyltrimethyl ammonium bromide) solution and 40 µL of proteinase K. Incubate at 60°C for 10 minutes.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge the lysate at 16,000 × g for 10 minutes.

- Automated Extraction: Transfer the supernatant to a loading cartridge of a Maxwell RSC Instrument. Use the Maxwell RSC Pure Food GMO and Authentication Kit and execute the "PureFood GMO" program.

- Elution: Elute the purified DNA in 100 µL of nuclease-free water. Include a negative control (nuclease-free water) in each extraction batch.

Protocol C: Assessing ARG Mobility via Multiplexed ddPCR

The mobility potential of an ARG, defined by its physical linkage to a mobile genetic element (MGE), is a critical risk indicator. This protocol uses multiplexed ddPCR to quantify the linkage between the sulfonamide resistance gene sul1 and the class 1 integron integrase gene intI1 [29].

- DNA Shearing: Shear the environmental DNA to an average fragment size of ~20 kbp. This reduces the rate of false-positive linkage detection from two unlinked genes residing on the same large chromosome [29].

- Droplet Generation and PCR: Prepare a duplex ddPCR reaction mixture containing primers and probes for both sul1 (e.g., FAM-labeled) and intI1 (e.g., HEX-labeled). Generate thousands of droplets from the reaction mix.

- Thermal Cycling: Run the PCR with optimized cycling conditions.

- Droplet Reading and Analysis: Read the droplets on a droplet reader. Analyze the results based on four droplet populations:

- Double-negative (no target)

- FAM-positive (sul1 only)

- HEX-positive (intI1 only)

- Double-positive (both sul1 and intI1, indicating physical linkage)

- Calculate Linkage Percentage: The proportion of linked ARG-MGE is calculated as the concentration of double-positive droplets divided by the total concentration of ARG-positive droplets. The method has been validated with model DNA mixtures, showing high accuracy (R² > 0.999) between observed and expected linkage [29].

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow and analysis principle of this mobility assessment protocol.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of the aforementioned protocols relies on key reagents and kits. The following table details essential solutions for ARG surveillance workflows.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for ARG Surveillance

| Item/Category | Function/Application | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kit | Purifies DNA from complex, inhibitor-rich matrices like biosolids and concentrated wastewater. | Maxwell RSC Pure Food GMO and Authentication Kit (Promega). Includes CTAB and proteinase K for effective lysis [13]. |

| ddPCR Supermix | Forms the base reaction mixture for droplet generation and digital PCR. | Commercial ddPCR supermix (e.g., from Bio-Rad). Formulated for efficient amplification within droplets [29] [33]. |

| Fluorogenic Probes | Enable multiplexed detection of specific ARG and MGE targets. | FAM-labeled sul1 probe and HEX-labeled intI1 probe. Probes must be designed for specific ARG targets (e.g., blaCTX-M, tet(A)) [29]. |

| Positive Control Plasmid | Validates PCR assay efficiency and specificity. | Linearized pNORM plasmid, containing linked sul1 and intI1 genes, can be used as a control for mobility assays [29]. |

| Beef Extract & AlCl₃ | Key reagents for the aluminum-based precipitation method for concentrating ARGs from water. | Used in the AP concentration method to facilitate viral and bacterial precipitation and subsequent elution [13]. |

The escalating challenge of antimicrobial resistance demands surveillance strategies that are as dynamic and interconnected as the One Health compartments it threatens. The methodologies detailed herein—from evaluating the superior sensitivity and inhibitor tolerance of ddPCR for challenging matrices to implementing advanced protocols for assessing ARG mobility—provide a critical foundation for robust environmental AMR monitoring. By carefully selecting concentration methods, leveraging the appropriate PCR technology based on the sample matrix and surveillance question, and integrating mobility potential into risk assessments, researchers can generate the high-quality, actionable data necessary to track and mitigate the spread of resistance across the globe.

From Theory to Practice: Deploying qPCR and ddPCR in Complex ARG Samples

Sample Preparation and Concentration Methods for Environmental Matrices

Within the broader research on qPCR versus ddPCR for antibiotic resistance gene (ARG) quantification, appropriate sample preparation is the most critical foundational step. The quality and concentration of nucleic acids extracted from complex environmental matrices directly determine the accuracy, sensitivity, and reproducibility of downstream molecular analyses [35] [37]. Environmental samples—including soils, wastewater, and organic residues—present unique challenges for molecular analysis due to the presence of PCR inhibitors such as humic acids, heavy metals, and complex organic matter [35] [15]. These compounds can co-extract with nucleic acids and significantly impact PCR efficiency, potentially leading to underestimation or false-negative results [5] [15]. This application note provides detailed protocols and data-driven comparisons to optimize sample preparation for ARG quantification in environmental matrices, with specific consideration of the different requirements and advantages of qPCR and ddPCR platforms.

Comparative Performance of qPCR and ddPCR with Environmental Samples

The choice between qPCR and ddPCR technologies influences sample preparation requirements. ddPCR's partitioning technology and endpoint measurement make it more tolerant to inhibitors that significantly affect qPCR's exponential amplification phase [1] [5]. The table below summarizes key comparative studies highlighting these differential performance characteristics.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of qPCR and ddPCR with Environmental and Complex Samples

| Sample Matrix | Target | qPCR Performance | ddPCR Performance | Key Findings | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soils and Organic Residues | sul1, qnrB ARGs | High loss of sensitivity with inhibitors; overestimation of targets | Accurate quantification with 70 ng DNA without facilitator; 10x higher sensitivity for CNV | ddPCR allowed accurate quantification where qPCR showed inhibited signal [35] | |

| Spiked Food Samples | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum | Good linearity (R² ≥ 0.996); higher LoD | Good linearity (R² ≥ 0.996); 10-fold lower LoD | ddPCR more sensitive but limited at high concentrations (>10⁶ CFU/mL) [24] | |

| Bloodstream Infections | 12 Pathogens, 3 AMR genes | Suboptimal sensitivity (≤10-50%); long turnaround | Aggregate sensitivity: 72.5% (vs. BC); specificity: 63.1%; 2.5h turnaround | ddPCR served as rapid add-on to blood culture [38] | |

| Synthetic DNA with Contaminants | Gene Expression Targets | Highly variable with inconsistent inhibition; artifactual Cq values | Precise, reproducible data despite inhibitors | ddPCR superior for low-abundance targets with variable contaminants [5] | |

| FCGR3B Copy Number | Human FCGR3B Gene | Full concordance with dPCR for copy number | Full concordance with qPCR for copy number | No advantage for dPCR in this clean, controlled application [39] | |

| Bloodstream Infections | A. baumannii (gltA, OXA-23) | LOD: 3 × 10⁻³ ng/μL | LOD: 3 × 10⁻⁴ ng/μL; Higher precision (CV < 25%) | ddPCR demonstrated 10-fold higher sensitivity [40] |

Experimental Workflow for Sample Processing

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for processing environmental samples, from collection through nucleic acid extraction and quality assessment, for subsequent qPCR or ddPCR analysis.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Soil and Sediment Sample Processing

This protocol is optimized for complex matrices high in humic substances and organic matter, based on methodologies validated for ARG quantification [35] [37].

Materials:

- Soil or sediment sample (0.5 g fresh weight)

- Lysis buffer: 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 100 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), 100 mM Sodium Phosphate, 1.5 M NaCl, 1% CTAB

- Proteinase K (20 mg/mL)

- Lysozyme (50 mg/mL)

- SDS (20%)

- Phenol:Chloroform:Isoamyl Alcohol (25:24:1)

- Isopropanol and 70% Ethanol

- Commercial silica-column based purification kit

- TE Buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0)

Procedure:

- Homogenization: Weigh 0.5 g of soil/sediment into a 2-mL microcentrifuge tube. Add 1 mL of lysis buffer and vortex vigorously for 1 minute.

- Enzymatic Lysis: Add 20 μL of Proteinase K (20 mg/mL) and 50 μL of Lysozyme (50 mg/mL). Mix by inversion and incubate at 37°C for 30 minutes with gentle agitation.

- Chemical Lysis: Add 100 μL of 20% SDS, mix thoroughly, and incubate at 65°C for 2 hours with occasional mixing by inversion.

- Crude Lysate Clarification: Centrifuge at 13,000 × g for 5 minutes at room temperature. Transfer the supernatant to a new 2-mL tube.

- Inhibitor Removal (Organic Extraction): Add an equal volume of Phenol:Chloroform:Isoamyl Alcohol. Vortex for 30 seconds and centrifuge at 13,000 × g for 5 minutes. Carefully transfer the upper aqueous phase to a new tube.

- DNA Precipitation: Add 0.7 volumes of isopropanol, mix by inversion, and incubate at -20°C for 1 hour. Centrifuge at 13,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C to pellet DNA.

- Wash: Discard the supernatant. Wash the pellet with 1 mL of ice-cold 70% ethanol. Centrifuge at 13,000 × g for 5 minutes. Carefully discard the ethanol and air-dry the pellet for 10-15 minutes.

- Column Purification: Resuspend the DNA pellet in 100 μL of TE Buffer. Complete the purification using a commercial silica-column kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. This step is critical for removing residual inhibitors.

- Elution: Elute DNA in 50-100 μL of Elution Buffer or nuclease-free water.

Protocol 2: Wastewater and Aqueous Sample Concentration

This protocol is designed for quantifying ARGs in wastewater, a critical reservoir for antibiotic resistance dissemination [37] [15].

Materials:

- Wastewater sample (100 mL to 1 L)

- Sterile 0.22 μm or 0.45 μm pore-size mixed cellulose ester filters

- Filtration apparatus and vacuum pump

- TE Buffer (pH 8.0)

- Commercial DNA extraction kit suitable for water filters

Procedure:

- Filtration: Assemble the filtration apparatus with a sterile membrane filter. Filter a known volume of wastewater (100 mL to 1 L, depending on turbidity) under vacuum.

- Biomass Recovery: Aseptically remove the filter membrane from the apparatus using sterile forceps. Fold or roll the filter and place it into a 2-mL bead-beating tube.

- Direct Lysis: Add 1 mL of lysis buffer from the commercial kit to the tube. Proceed with the manufacturer's lysis protocol, which may include bead-beating for mechanical disruption.

- DNA Purification: Complete the DNA extraction following the manufacturer's instructions for complex samples. Ensure all wash steps are performed to remove contaminants.

- Elution: Elute the final DNA in a small volume (50-100 μL) to maximize concentration.

Protocol 3: Nucleic Acid Quality Assessment and Normalization

Accurate normalization is essential for reliable inter-sample comparison in both qPCR and ddPCR [5] [37].

Procedure:

- Spectrophotometry: Measure DNA concentration and purity using a NanoDrop or similar spectrophotometer. Record A260/A280 and A260/A230 ratios.

- Acceptable Quality: A260/A280 ≈ 1.8-2.0; A260/A230 > 2.0.

- Low A260/A230 (<1.8) indicates residual humic acids or chaotropic salts, requiring further cleanup.

- Fluorometry: Quantify DNA concentration using a Qubit or similar fluorometer. This method is more specific for double-stranded DNA and provides a more accurate concentration for PCR normalization than spectrophotometry.

- Dilution and Normalization: Based on fluorometric quantification, dilute all samples to a uniform working concentration (e.g., 5-10 ng/μL) in nuclease-free water. For qPCR, this minimizes variation in reaction efficiency. For ddPCR, this helps ensure partitions are not overloaded.

- Inhibition Testing (qPCR-specific): Perform a standard curve with a control template spiked into a dilution series of the sample extract. A significant shift (higher Cq) in the sample compared to the control indicates PCR inhibition. Alternatively, use an internal positive control (IPC).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Sample Preparation and ARG Quantification

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Technical Notes | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| CTAB Lysis Buffer | Effective lysis of environmental microbes; co-precipitates humic acids. | Critical for soil/sludge samples high in polyphenols and polysaccharides. | [37] |

| Silica-column Purification Kits | Selective binding and washing of DNA; removes PCR inhibitors. | Essential final clean-up step post crude extraction. Ensure wash buffers contain ethanol. | [40] |

| Proteinase K & Lysozyme | Enzymatic digestion of cell walls and proteins for enhanced lysis. | Combined use improves yield from Gram-positive bacteria common in environments. | [37] |

| T4 Gene 32 Protein | PCR facilitator; binds single-stranded DNA, improves efficiency in qPCR. | Can be added to qPCR reactions to mitigate residual inhibitor effects. | [35] |

| TaqMan Probes (FAM/HEX) | Sequence-specific fluorescent detection for qPCR and ddPCR. | Required for multiplex ddPCR (e.g., pathogen + resistance gene). | [38] [40] |

| ddPCR Supermix (No dUTP) | Optimized reaction mix for droplet generation and digital PCR. | Formulated for stable water-in-oil emulsion; different from standard qPCR master mixes. | [40] |

Technology Selection Workflow

The following decision diagram guides the selection of the appropriate quantification platform based on sample characteristics and research objectives, as informed by the comparative studies.

Robust sample preparation is the cornerstone of reliable ARG quantification in complex environmental matrices. The protocols outlined here are designed to maximize nucleic acid yield and purity while minimizing co-extraction of PCR inhibitors. The choice between qPCR and ddPCR platforms should be guided by sample quality, target abundance, and required precision. ddPCR demonstrates clear advantages for challenging samples with residual inhibitors or for quantifying low-abundance targets, while qPCR remains a powerful and efficient tool for high-throughput analysis of well-characterized sample types. By integrating these optimized preparation methods with the appropriate detection technology, researchers can generate publication-quality data on the prevalence and abundance of ARGs in the environment.

Designing Effective Primers and Probes for High-Priority ARG Targets

The global health crisis of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) necessitates robust environmental surveillance strategies, with wastewater treatment plants recognized as critical hotspots for the dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) [36] [13]. Reliable monitoring depends heavily on the sensitivity and reproducibility of analytical methods like quantitative PCR (qPCR) and droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) for detecting and quantifying clinically relevant ARGs in complex matrices [13] [15]. The performance of these PCR-based technologies is fundamentally determined by the quality of primer and probe design, which controls the exquisite specificity and sensitivity that make these methods uniquely powerful [41]. This application note provides detailed protocols and design considerations for creating effective primers and probes targeting high-priority ARGs, framed within the comparative context of qPCR and ddPCR quantification for environmental AMR research.

Foundational Principles of Primer and Probe Design

Core Design Parameters

Primers should be designed with a length of 18-24 nucleotides for ideal amplification, while probes typically range between 15-30 nucleotides, with the exact length being highly target-specific [42]. The melting temperature (Tm) for primers should be maintained at 54°C or higher (optimal range 54°C-65°C), with the annealing temperature (Ta) often 2-5°C above the Tm [42]. The GC content should be kept between 40-60%, with a 20-nucleotide primer containing 8-12 G or C bases [42].

Table 1: Optimal Design Characteristics for Primers and Probes

| Parameter | Primers | Probes |

|---|---|---|

| Length | 18-24 nucleotides | 15-30 nucleotides |

| Tm | 54°C or higher (54°C-65°C) | Usually 5-10°C higher than primers |

| GC Content | 40-60% | 35-60% |

| GC Clamp | Maximum of 3 G/Cs at 3' end | Avoid G at 5' end |

| Specificity | Check against non-target sequences | Highly specific to target |

Avoiding Secondary Structures

Primer-dimmers and hairpin loops are two types of secondary structures that can form during PCR reactions [42]. Self-dimers occur through hybridisation of two forward primers due to intra-primer homology, while cross-dimers form through hybridisation of forward and reverse primers due to inter-primer homology [42]. These structures prevent primers from annealing to the target sequence and can be avoided by adjusting annealing temperature, avoiding cross homology, and changing primer or DNA concentration [42]. The parameters "self-complementarity" and "self 3′-complementarity" should be kept as low as possible [42].

High-Priority ARG Targets and Experimentally Validated Primers

Clinically Relevant ARG Targets

Based on the latest EFSA scientific opinion, the highest-priority ARGs for monitoring include those conferring resistance to carbapenems (e.g., blaVIM, blaNDM, blaOXA variants), extended-spectrum cephalosporins (blaCTX-M, AmpC), colistin (mcr), methicillin (mecA), glycopeptides (vanA), and oxazolidinones (cfr, optrA) [13]. Additionally, resistance genes conferring reduced susceptibility to tetracyclines, β-lactams, quinolones, and phenicols remain highly relevant for environmental AMR monitoring [13].

Table 2: Experimentally Validated Primer Sequences for High-Priority ARG Targets

| Target ARG | Primer Name | Sequence (5'→3') | Amplicon Size | Annealing Temp | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| blaCTX-M group 1 | RTCTX-M-F | CTATGGCACCACCAACGATA | 103 bp | 58°C | [43] |

| RTCTX-M-R | ACGGCTTTCTGCCTTAGGTT | ||||

| blaCMY-2 | FW3CMY-2Lahey | AGACGTTTAACGGCGTGTTG | 128 bp | 58°C | [43] |

| RV4CMY-2Lahey | TAAGTGCAGCAGGCGGATAC | ||||

| qnrA | qnrAm-F | AGAGGATTTCTCACGCCAGG | 580 bp | 56°C | [43] |

| qnrAm-R | TGCCAGGCACAGATCTTGAC | ||||

| qnrS | qnrSm-F | GCAAGTTCATTGAACAGGGT | 428 bp | 60°C | [43] |

| qnrSm-R | TCTAAACCGTCGAGTTCGGCG | ||||

| ermB | ermB1 | CCGAACACTAGGGTTGCTC | 139 bp | 56°C | [43] |

| ermB2 | ATCTGGAACATCTGTGGTATG |

Sample Processing and Nucleic Acid Extraction Protocols

Concentration Methods for Complex Matrices

For wastewater samples, two concentration methods have been systematically compared: filtration-centrifugation (FC) and aluminum-based precipitation (AP) [36] [13]. The FC protocol involves filtering 200 mL of treated wastewater through 0.45 µm sterile cellulose nitrate filters, which are then deposited in Falcon tubes containing buffered peptone water with Tween, agitated vigorously, and subjected to sonication for 7 minutes [13]. After removing filters, samples are centrifuged at 3000× g for 10 minutes, with the pellet resuspended in PBS and concentrated again at 9000× g for 10 minutes [13].

The AP method involves lowering the pH of 200 mL wastewater to 6.0, followed by precipitation with 1 part of 0.9 N AlCl3 per 100 parts sample [13]. The solution is shaken at 150 rpm for 15 minutes, centrifuged at 1700× g for 20 minutes, and the pellet reconstituted in 10 mL of 3% beef extract (pH 7.4) with shaking at 150 rpm for 10 minutes at room temperature [13]. The resultant suspension is centrifuged for 30 minutes at 1900× g, with the final pellet resuspended in 1 mL of PBS [13]. Comparative studies show the AP method provides higher ARG concentrations than FC, particularly in wastewater samples [36].

DNA Extraction and Purification

For both wastewater concentrates and biosolids, DNA extraction can be performed using the Maxwell RSC Pure Food GMO and Authentication Kit with the Maxwell RSC Instrument [13]. The protocol involves adding 300 μL of concentrated water samples or resuspended biosolids to 400 μL of cetyltrimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB) and 40 μL of proteinase K solution, followed by incubation at 60°C for 10 minutes and centrifugation at 16,000× g for 10 minutes [13]. The supernatant is transferred with 300 μL of lysis buffer to the loading cartridge for automated extraction, with DNA eluted in 100 μL nuclease-free water [13].

qPCR and ddPCR Workflows: Comparative Experimental Protocols

qPCR Assay Protocol

For SYBR Green-based qPCR assays, prepare 10 μL reaction mixtures containing:

- 5 μL of 2X PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix

- 0.6 μL of each primer (10 μM concentration, 600 nM final concentration)