Reductionism vs Holism in Molecular Biology: Bridging Approaches for Advanced Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of reductionist and holistic methodologies in molecular biology, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Reductionism vs Holism in Molecular Biology: Bridging Approaches for Advanced Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of reductionist and holistic methodologies in molecular biology, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the philosophical foundations and historical context of both approaches, examines their practical applications in research and therapeutic development, addresses methodological limitations and optimization strategies, and presents a comparative framework for validation. By synthesizing evidence from current literature, we demonstrate how these seemingly opposed paradigms are actually complementary, with integrated applications in systems biology offering promising pathways for overcoming complex challenges in biomedical research and drug discovery.

Philosophical Roots and Historical Evolution of Biological Approaches

Reductionism is a fundamental concept in the philosophy of science, particularly relevant to molecular biology research. It encompasses a set of claims about the relations between different scientific domains, primarily addressing whether properties, concepts, explanations, or methods from one scientific domain (typically at higher levels of organization) can be deduced from or explained by those of another domain (typically concerning lower levels of organization) [1] [2]. This framework is essential for understanding the ongoing debate between reductionist and holistic approaches in biological research, especially as systems biology gains prominence as a complementary paradigm. The discussion of reductionism is typically divided into three distinct but interrelated dimensions: ontological, methodological, and epistemic, each contributing differently to scientific practice and philosophical understanding [1] [2] [3].

The Three Dimensions of Reductionism

Ontological Reductionism

Ontological reductionism makes claims about the fundamental nature of reality, asserting that each particular biological system (e.g., an organism) is constituted by nothing but molecules and their interactions [1] [2]. In metaphysical terms, this position is often called physicalism or materialism, assuming that: (a) biological properties supervene on physical properties (meaning no difference in biological properties without a difference in underlying physical properties), and (b) each particular biological process is metaphysically identical to some particular physico-chemical process [1] [2].

This form of reductionism exists in weaker and stronger versions. The weaker version, called token-token reduction, claims that each particular biological process is identical to some particular physico-chemical process, while the stronger type-type reduction maintains that each type of biological process is identical to a type of physico-chemical process [1] [2]. Ontological reductionism in its weaker form represents a default stance among most contemporary philosophers and biologists, with vitalism (the denial of physicalism) being largely of historical interest today [1].

Methodological Reductionism

Methodological reductionism represents a procedural approach to scientific investigation, advocating that biological systems are most fruitfully studied at the lowest possible level and that experimental research should focus on uncovering molecular and biochemical causes [1] [4] [2]. This approach often involves what has been termed "decomposition and localization" - breaking down complex systems into their constituent parts to understand their functions and interactions [1] [2].

Unlike ontological reductionism, methodological reductionism does not follow directly from ontological claims and remains more controversial in practice [1]. Critics argue that exclusively reductionist research strategies can be systematically biased and may overlook salient biological features that emerge only at higher levels of organization [1] [2]. Nevertheless, methodological reductionism has driven tremendous successes in molecular biology, allowing researchers to explain phenomena such as bacterial resistance to therapy through acquired genes or patient susceptibility to infection through specific receptor mutations [4].

Epistemic Reductionism

Epistemic reductionism concerns the relationship between bodies of scientific knowledge, specifically whether knowledge about one scientific domain (typically higher-level processes) can be reduced to knowledge about another domain (typically lower-level processes) [1] [2] [3]. This has proven to be the most controversial aspect of reductionism in the philosophy of biology [1].

Epistemic reduction can be further divided into two categories:

- Theory reduction: The claim that one theory can be logically deduced from another theory [1] [2] [3]

- Explanatory reduction: The position that representations of higher-level features can be explained by representations of lower-level features [1] [2]

The debate about reduction in biology has centered not only on whether epistemic reduction is possible but also which notion of epistemic reduction is most adequate for actual scientific practice [1] [2].

Comparative Analysis: Reductionist vs. Holistic Approaches

The following table summarizes the core differences between reductionist and holistic approaches across the three dimensions, with particular emphasis on their application in molecular biology research:

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Reductionist vs. Holistic Approaches in Biology

| Dimension | Reductionist Approach | Holistic/Systems Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Ontological Commitment | Biological systems are constituted solely by molecules and their interactions [1] [2] | Wholes or systems may possess properties not reducible to their parts (emergent properties) [4] [5] [6] |

| Methodological Strategy | Analyze systems by decomposing into constituent parts; focus on molecular and biochemical causes [1] [4] [2] | Study systems intact; focus on networks, interactions, and emergent properties [4] [6] |

| Epistemic Goal | Explain higher-level phenomena by reducing to lower-level processes and principles [1] [2] [3] | Explain phenomena through system-level principles that may not be derivable from lower levels [4] [6] |

| Primary Research Focus | Isolated components, linear pathways, specific molecular mechanisms [4] [7] | Networks, complex interactions, system-level behaviors [4] [6] |

| Representative Techniques | Gene cloning, protein purification, single-gene knockout, in vitro assays [4] | Genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, mathematical modeling, network analysis [4] [6] |

| Strengths | High precision for specific mechanisms; enables targeted interventions; historically productive [4] [5] | Captures complexity and emergent properties; identifies network-level regulation; handles multi-scale integration [4] [6] |

| Limitations | May overlook system-level properties and interactions; limited ability to predict emergent behaviors [4] [6] | Can be computationally intensive; may lack mechanistic detail; challenging to validate experimentally [4] [5] |

Experimental Evidence: A Case Study Comparison

To illustrate the practical differences between reductionist and holistic approaches, we examine a case study from microbiology research on cholera toxin expression:

Table 2: Experimental Comparison of Reductionist vs. Holistic Methodologies

| Aspect | Reductionist Approach | Holistic/Systems Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Research Question | How do specific environmental conditions regulate cholera toxin gene (ctxA) transcription? [4] | How is cholera toxin expression regulated within the host infection context and genetic network? [4] |

| Experimental System | Simplified in vitro reporter system with controlled variables [4] | Intact host infection model monitoring multiple genetic loci over time [4] |

| Key Methodology | Reporter gene fusions to ctxA promoter under defined conditions [4] | Genomic, microarray, and proteomic analyses of bacterial behavior during infection [4] |

| Variables Controlled | Limited, well-defined environmental factors | Complex, interacting host-pathogen factors in physiological context |

| Data Type | Quantitative measurements of reporter expression | Multivariate data on coregulated genetic networks and temporal dynamics |

| Interpretation Framework | Linear causal relationships between stimuli and gene expression | Network interactions, feedback loops, and emergent system properties |

| Key Findings | Identification of specific environmental signals regulating ctxA transcription [4] | Discovery of complex regulatory networks coordinating virulence expression [4] |

| Technical Advantages | Reduced complexity; clear causal inference; high reproducibility | Physiological relevance; identification of unexpected connections; comprehensive perspective |

| Notable Limitations | May miss relevant contextual factors; limited predictive power in vivo | Difficult to establish specific causality; complex data interpretation; lower reproducibility |

Experimental Protocols

Reductionist Protocol: Reporter Gene Fusion for Analyzing Gene Regulation

- Clone promoter region of the gene of interest (e.g., ctxA cholera toxin gene) upstream of a reporter gene (e.g., GFP, luciferase) [4]

- Introduce reporter construct into model organism using appropriate transformation method

- Establish baseline measurement of reporter expression under controlled reference conditions

- Apply experimental treatments with specific environmental variables (e.g., pH, temperature, chemical inducers)

- Quantify reporter expression using appropriate methods (fluorescence, luminescence, etc.)

- Analyze data to determine fold-change in expression relative to baseline for each condition

- Repeat experiments with controlled modification of putative regulatory elements to confirm mechanisms

Holistic/Systems Biology Protocol: Network Analysis of Genetic Regulation

- Design time-course experiment capturing multiple stages of host-pathogen interaction [4]

- Collect multi-omics data simultaneously tracking transcriptome, proteome, and metabolome changes [4]

- Incorporate perturbation analysis by modifying key network components and measuring system response [4]

- Construct mathematical network models representing interactions between system components [4]

- Validate model predictions through targeted experimental interventions [4]

- Iterate between modeling and experimentation to refine understanding of network dynamics [4]

- Analyze emergent system properties that arise from network interactions rather than individual components [4]

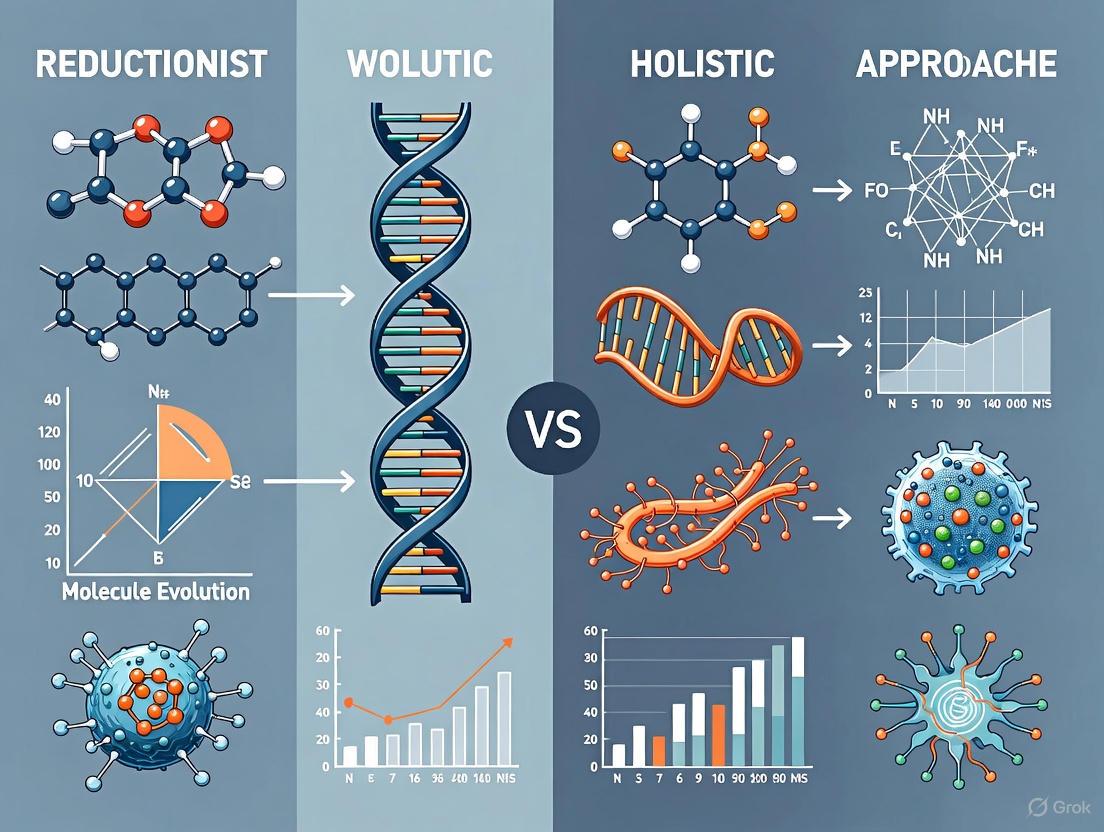

Visualization of Conceptual Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental differences in how reductionist and holistic approaches conceptualize biological systems:

Research Reagent Solutions for Experimental Approaches

The following table details essential research reagents and their functions for implementing both reductionist and holistic research strategies:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Reductionist and Holistic Approaches

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Applicable Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reporter Systems | GFP, luciferase, β-galactosidase | Visualize and quantify gene expression in real-time | Primarily Reductionist [4] |

| Gene Editing Tools | CRISPR-Cas9, RNAi, traditional knockout vectors | Precisely modify specific genes to study function | Both [4] |

| Omics Technologies | Microarrays, RNA-seq, mass spectrometry | Comprehensive profiling of molecular species | Primarily Holistic [4] [6] |

| Protein Interaction Tools | Yeast two-hybrid, co-IP kits, FRET probes | Identify and characterize molecular interactions | Both |

| Pathway Modulators | Chemical inhibitors, activators, receptor agonists/antagonists | Specifically target signaling pathways | Primarily Reductionist |

| Computational Tools | Network analysis software, mathematical modeling platforms | Analyze complex datasets and build predictive models | Primarily Holistic [4] [6] |

| Cell Culture Systems | Immortalized cell lines, primary cells, 3D culture systems | Provide controlled environments for experimentation | Both |

| Animal Models | Mice, zebrafish, Drosophila with genetic modifications | Study biological processes in physiological context | Both |

The debate between reductionism and holism in molecular biology represents a fundamental tension in how we approach biological complexity. Reductionism, particularly in its methodological form, has driven tremendous advances in our understanding of specific molecular mechanisms [4] [5]. However, the emergence of systems biology reflects a growing recognition that exclusively reductionist approaches may be insufficient to explain the complex, emergent behaviors of biological systems [4] [7] [6].

Rather than representing mutually exclusive paradigms, contemporary biological research increasingly recognizes the complementary value of both approaches [4] [5]. Reductionist methods provide the precise mechanistic understanding necessary for targeted interventions, while holistic approaches offer the broader contextual framework needed to understand system-level behaviors [4]. The most productive path forward likely lies in strategically integrating both perspectives - using reductionist methods to unravel specific mechanisms within the contextual framework provided by holistic approaches [4] [6].

This integrated approach is particularly valuable in drug development, where understanding specific molecular targets (reductionist) must be balanced with anticipating system-level responses and network perturbations (holistic) [4]. As biological research continues to evolve, the creative tension between these perspectives will likely continue to drive scientific progress, with each approach providing unique insights into different aspects of biological complexity.

The fundamental debate between reductionism and holism represents a philosophical schism that continues to shape modern biological research and drug development strategies. Reductionism, which breaks down complex systems into their constituent parts to understand fundamental mechanisms, has served as the cornerstone of scientific inquiry for centuries [8]. In molecular biology, this approach has enabled significant advancements, including the development of targeted therapies that address disease mechanisms at the molecular level [8]. Conversely, holism emphasizes that complex systems exhibit properties and behaviors that cannot be fully explained by studying their individual components in isolation—a concept famously articulated by Aristotle's view that "the whole is greater than the sum of its parts" [9].

The emergence of systems biology in recent decades represents a concerted effort to bridge these seemingly opposed philosophies. This interdisciplinary field recognizes that biological systems—from individual cells to entire organisms—are characterized by inherent complexity, featuring heterogeneous elements, polyfunctional processes, and interactions across multiple spatiotemporal scales [10]. This complexity gives rise to emergent properties, which are system-level behaviors that cannot be predicted solely by analyzing individual components [11]. Understanding these emergent properties has become increasingly crucial in drug development, where therapeutic interventions may have unanticipated effects due to the complex, interconnected nature of biological systems.

Theoretical Foundations: From Aristotle to Modern Systems Thinking

Historical Development of Holistic Philosophy

The philosophical underpinnings of holism trace back to Aristotle, whose metaphysical framework posited that understanding any entity requires consideration of its relationships, context, and broader implications [9]. This perspective fundamentally challenged reductionist thinking by emphasizing interconnectedness and the unity of all things. Aristotle's concept of holism has found renewed relevance in modern approaches to biological complexity, where the relationships between components often prove as important as the components themselves.

The term "holism" was formally coined by Jan Smuts in the 1920s, who described a universal tendency for stable wholes to form from parts across all levels of organization, from atomic to biological to psychological systems [7]. This classical holism emerged alongside, but distinct from, vitalism—the belief that a special life-force differentiates living from inanimate matter [7]. While vitalism was largely abandoned by the 1920s due to its inability to provide a basis for experimental research, holistic thinking evolved to focus on observable emergent properties rather than metaphysical life forces.

The Reductionist Dominance in Molecular Biology

Throughout the 20th century, reductionism became the dominant paradigm in molecular biology, influenced by Cartesian dualism (viewing the body as a machine with parts that can be studied independently) and logical positivism (emphasizing empirical observation and experimentation) [12]. The biomedical model that emerged in the mid-20th century viewed the body as a collection of discrete systems that could be understood and manipulated independently [12].

This approach yielded tremendous successes, exemplified by the Hodgkin-Huxley (HH) model from the 1950s, which used ordinary differential equations to describe the propagation of electrical signals through neuronal axons by reducing neuronal activity to an electrical circuit model [10]. Such reductionist breakthroughs demonstrated the power of isolating and studying individual components of complex biological systems, establishing a methodological foundation that would dominate molecular biology for decades.

The Limits of Reductionism and Systems Biology Emergence

By the late 20th century, the limitations of strict reductionism became increasingly apparent, particularly in addressing fundamental questions in biological systems [10]. While reductionism proved effective for studying systems with regular, symmetric organization or random systems with enormous numbers of identical components, it struggled with biological complexity characterized by topologically irregular interactions, heterogeneous elements, and multi-scale dynamics [10].

The ensuing shift toward holistic approaches in modern biological research recognizes that biological systems operate through complex networks of interactions that span multiple organizational levels. This integrated perspective has given rise to systems biology, which seeks to understand biological systems as integrated wholes rather than collections of isolated parts [7]. The core insight driving this field is that emergent properties arise from the interactions between system components, making these properties irreducible to the characteristics of individual parts [11].

Emergent Properties in Biological Systems: Theory and Examples

Defining Emergent Properties

Emergent properties represent system-level characteristics that arise through the interactions of multiple system components but cannot be found in or predicted from the individual components themselves [11] [13]. These properties manifest across all biological scales, from molecular networks to ecosystems, and represent a fundamental challenge to purely reductionist explanations in biology.

The concept of emergence was first explained by philosopher John Stuart Mill in 1843, with the term "emergent" later coined by G. H. Lewes [11]. In biological contexts, emergent properties demonstrate non-linear dynamics, where system outputs are not proportional to inputs, and often feature feedback loops that create self-regulating behaviors.

Examples Across Biological Scales

Table: Examples of Emergent Properties in Biological Systems

| Biological Scale | System Components | Emergent Property | Research/Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular | Sodium (toxic, reacts violently with water) and Chlorine (toxic gas) | Table salt (non-toxic, crystalline, edible) | Demonstrates fundamental principle that compound properties cannot be predicted from elements |

| Cellular | Individual metabolic enzymes (e.g., phosphofructokinase) | Glucose metabolism pathway (glycolysis) | Understanding metabolic regulation, metabolic disease mechanisms, drug targeting |

| Organ | Individual cardiac cells | Heart pumping blood | Cardiovascular function, heart disease pathophysiology, cardiotoxicity screening |

| Neural | Individual neurons | Consciousness, cognition, information processing | Neurological disease mechanisms, psychotropic drug development, neurotoxicity assessment |

| Ecological | Individual bees (queen, workers, drones) | Colony organization with division of labor | Environmental toxicology, ecosystem impact assessment |

Molecular Level: A classic example of emergence can be found in simple chemical compounds. The elements sodium and chlorine individually exhibit toxic properties and reactivity, but when combined, they form table salt (sodium chloride), which displays entirely different characteristics—crystal structure, solubility, and non-toxicity—that are essential for biological function [11].

Cellular Level: At the cellular level, individual enzymes such as phosphofructokinase perform specific biochemical reactions, but the coordinated operation of multiple enzymes in the glycolytic pathway enables the emergent property of glucose metabolism—a complex, regulated process that provides cellular energy [11]. This emergence enables metabolic regulation that would be impossible for individual enzymes.

Organ Level: The heart's pumping function represents an emergent property of coordinated cardiac cell activity. While individual cardiac muscle cells contract, only their organized assembly into cardiac tissue and the heart organ produces the coordinated pumping action that circulates blood throughout the body [11]. This emergent function is central to cardiovascular physiology and drug development.

Neural Systems: Consciousness and cognition represent sophisticated emergent properties of neural networks. Individual neurons transmit electrical signals, but their organized interconnection in neural circuits gives rise to complex cognitive functions, thought processes, and adaptive responses to stimuli [11]. This multi-scale emergence presents both challenges and opportunities for neurological drug development.

Social Insects: In honeybee colonies, the division of labor among queen bees, drones, and worker bees produces emergent colony-level behaviors including hive maintenance, foraging efficiency, and temperature regulation that cannot be attributed to any individual bee [11]. Such ecological emergence models complex system behaviors relevant to population-level biological responses.

Comparative Analysis: Reductionist vs. Holistic Approaches

Methodological Comparison

Table: Methodological Comparison of Reductionist vs. Holistic Approaches

| Aspect | Reductionist Approach | Holistic Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Individual components in isolation | Systems as integrated wholes |

| Analytical Strategy | Breaks systems into constituent parts | Studies interactions and networks |

| Key Assumption | System behavior equals sum of parts | Emergent properties arise from interactions |

| Typical Methods | Controlled experiments, molecular profiling, targeted interventions | Network analysis, computational modeling, multi-omics integration |

| Data Requirements | High-precision, focused datasets | Large-scale, multi-dimensional data |

| Strengths | High precision, clear causality, target identification | Contextual understanding, prediction of system behavior, identification of emergent properties |

| Limitations | May miss system-level behaviors, limited context | Complexity, computational demands, challenging validation |

| Representative Models | Hodgkin-Huxley equations (neural firing) [10] | Multilayer networks, agent-based models [10] |

Quantitative Comparison of Research Outcomes

Table: Experimental Outcomes from Reductionist vs. Holistic Research

| Research Context | Reductionist Findings | Holistic/Systems Findings | Complementary Insights |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neural Function | Hodgkin-Huxley model: action potential mechanism via voltage-gated ion channels [10] | Neural circuits exhibit emergent computational properties; multilayer networks model neuro-vascular coupling [10] | Molecular mechanisms enable but don't explain higher neural functions |

| Transcription Networks | Identification of individual transcription factors and their binding sites [13] | Network motifs (e.g., feedback loops) give rise to emergent properties (bistability, oscillations) [13] | Component identification necessary but insufficient for system behavior prediction |

| Medical Research | Targeted therapies based on molecular pathways; personalized medicine based on genetic markers [12] | Quantitative holism integrating physiological, environmental, and lifestyle factors; network medicine [12] | Molecular targeting benefits from systems-level context for efficacy and safety |

| Plant Biology | Characterization of individual stress-response transcription factors [13] | TFN (Transcription Factor Network) models reveal emergent adaptive responses to environmental stresses [13] | Crop engineering requires both component characterization and system-level understanding |

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Research Reagent Solutions for Studying Emergent Properties

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Holistic Biology

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic Profiling Tools | RNA sequencing, ChIP-seq, ATAC-seq | Elucidate transcription factor networks and gene expression dynamics [13] | Identifying network components and interactions |

| Mathematical Modeling Frameworks | Ordinary differential equations, Boolean networks, Agent-based models | Simulate system dynamics and emergent behaviors [10] [13] | Predicting system behavior from component interactions |

| Network Analysis Tools | Annotated networks, Multilayer networks, Hypergraphs | Represent complex biological interactions across scales [10] | Mapping and analyzing complex biological systems |

| Computational Infrastructure | High-performance computing (HPC), Machine learning algorithms | Handle large-scale data analysis and complex simulations [10] | Managing computational demands of systems biology |

| Visualization Techniques | Y1H assays, Protein-binding microarrays, Live-cell imaging | Experimental validation of network interactions and dynamics [13] | Confirming predicted interactions and emergent behaviors |

Protocols for Studying Emergent Properties in Transcription Networks

Protocol 1: Elucidating Transcription Factor Networks and Emergent Properties in Arabidopsis

This protocol outlines an interdisciplinary approach for identifying transcription factor networks (TFNs) and their associated emergent properties, as demonstrated in Arabidopsis research [13].

Network Component Identification:

- Utilize genomic techniques (ChIP-seq, ATAC-seq) to identify transcription factors and their target genes (network nodes)

- Determine activation or inhibition relationships between nodes (edges) through protein-binding microarrays and yeast one-hybrid (Y1H) assays [13]

- Validate interactions through chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing

Network Motif Recognition:

- Analyze network architecture to identify recurring motifs (feedback loops, feed-forward loops)

- Correlate specific motifs with dynamic behaviors (bistability, oscillations, homeostasis)

Mathematical Modeling:

- Develop dynamical models using ordinary differential equations or Boolean networks

- Parameterize models using experimental data on transcript concentrations and dynamics

- Simulate network behavior under various conditions and perturbations

Experimental Validation:

- Perturb network components genetically or chemically

- Measure system responses using high-throughput transcriptomics and proteomics

- Compare experimental results with model predictions to refine understanding

Protocol 2: Multi-Scale Modeling for Emergent Properties in Neural Systems

This protocol describes a holistic approach to modeling emergent properties in neural systems using multilayer networks and high-performance computing [10].

Multi-Scale Data Integration:

- Collect structural data (neuronal connectivity, vasculature)

- Acquire functional data (neural activity, hemodynamics)

- Incorporate temporal data (developmental changes, aging effects)

Multilayer Network Construction:

- Represent different biological systems as individual network layers (e.g., neural connectivity, cerebral vasculature)

- Establish inter-layer connections that represent cross-system interactions

- Annotate nodes and edges with biological metadata

Simulation and Analysis:

- Implement agent-based models or differential equation systems on high-performance computing infrastructure

- Run simulations under baseline and perturbed conditions

- Identify emergent patterns through topological and dynamical analysis

Model Validation and Refinement:

- Compare simulation outputs with experimental observations

- Iteratively refine model parameters and structure

- Generate testable predictions for experimental validation

Visualization of Concepts and Relationships

Network Motifs and Emergent Properties in Transcription Factor Networks

Diagram Title: Network Motifs and Emergent Properties in Transcription Factor Networks

Multi-scale Integration in Holistic Biological Modeling

Diagram Title: Multi-scale Integration in Holistic Biological Modeling

The historical tension between reductionism and holism in biological research is progressively giving way to integrated approaches that leverage the strengths of both philosophical frameworks. Reductionist methods continue to provide essential mechanistic insights at the molecular level, while holistic approaches reveal how these components interact to produce system-level behaviors and emergent properties [8] [10].

The future of drug development and molecular biology research lies in quantitative holism—an approach that combines precise, reductionist-derived molecular data with holistic, systems-level modeling [12]. This integration enables researchers to bridge the gap between molecular mechanisms and organism-level outcomes, potentially leading to more effective therapeutic strategies with fewer unanticipated side effects.

As high-performance computing, artificial intelligence, and multi-omics technologies continue to advance, the practical barriers to implementing truly holistic approaches in biological research are rapidly diminishing [10]. By embracing both reductionist precision and holistic context, researchers can address the profound complexity of biological systems while maintaining the empirical rigor that has driven scientific progress for centuries. This integrated path forward promises to unlock new dimensions of understanding in biology and transform our approach to therapeutic intervention in human disease.

The molecular biology revolution, which gained tremendous momentum in the mid-20th century, was fundamentally underpinned by a reductionist approach that has since transformed our understanding of life processes. This methodological paradigm, which involves breaking down complex biological systems into their constituent parts to understand their structure and function, has been the cornerstone of biological research for decades [4]. Reductionism operates on the principle that complex phenomena are best understood by examining their simpler, more fundamental components [14]. In practical terms, this has meant that biologists seek to explain cellular and organismal behaviors through the properties of molecules, particularly DNA, RNA, and proteins, with the ultimate goal of explaining biology through the laws of physics and chemistry [15].

The triumphs of this reductionist approach are undeniable and have formed the foundation of modern molecular biology. The discovery of DNA's structure by Watson and Crick in 1953 epitomizes the power of reductionism, as it reduced the mystery of genetic inheritance to a chemical structure [14]. This breakthrough, along with numerous others summarized in Table 1, demonstrated that reductionism could yield profound insights into biological organization. The approach has been particularly successful in identifying discrete molecular components responsible for specific biological functions, such as identifying genes encoding beta-lactamases to explain bacterial antibiotic resistance or mutant receptors to explain susceptibility to infection [4]. This review will objectively compare the reductionist approach with emerging holistic perspectives, examining their respective strengths, limitations, and experimental support within molecular biology research.

Foundational Principles of Biological Reductionism

Reductionism in biology encompasses several distinct but interrelated concepts. Methodological reductionism, the most practically significant form for researchers, proposes that complex systems are best studied by analyzing their simpler components [4]. This approach traces back to Descartes' suggestion to "divide each difficulty into as many parts as is feasible and necessary to resolve it" [4]. In contemporary molecular biology, this manifests as studying isolated molecules, pathways, or genetic elements rather than intact systems.

Epistemological reductionism addresses relationships between scientific disciplines, specifically whether knowledge in one domain (like biology) can be reduced to another (like physics and chemistry) [4]. The often-cited declaration by Francis Crick that "the ultimate aim of the modern movement in biology is to explain all biology in terms of physics and chemistry" exemplifies this perspective [15]. While this viewpoint has been productive, many biologists recognize that different scientific disciplines remain because phenomena are often best understood at specific organizational levels rather than through fundamental physics alone [4].

Ontological reductionism represents a more philosophical position that biological systems are constituted by nothing but molecules and their interactions [4]. This perspective rejects the notion of any "vital force" or non-physical elements in living organisms, positioning biology as a continuation of physical sciences rather than a fundamentally separate enterprise [7].

The standard model of scientific reduction, proposed by Ernest Nagel, formalizes this approach through two key conditions: the "condition of connectability" (assumptions must connect terms between different scientific domains) and the "condition of derivability" (laws of the primary science should allow logical derivation of the secondary science's laws) [14]. Although this model has faced practical challenges in implementation, it has nonetheless guided much of molecular biological research throughout its development.

Key Historical triumphs of Reductionist Approaches

The reductionist approach has generated numerous landmark discoveries that form the foundation of modern molecular biology. These triumphs demonstrate the power of isolating and studying biological components in simplified systems.

Table 1: Historic Triumphs of Reductionism in Molecular Biology

| Discovery/Advancement | Key Researchers (Year) | Reductionist Approach | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA as Transforming Principle | Avery, MacLeod, McCarty (1944) | Isolated DNA from other cellular constituents | Conclusively demonstrated DNA alone responsible for genetic transformation [4] |

| Structure of DNA | Watson, Crick (1953) | X-ray crystallography of purified DNA | Revealed chemical basis of genetic inheritance [14] |

| Tobacco Mosaic Virus Reassembly | Fraenkel-Conrat, Williams (1955) | Separated viral RNA and coat protein components | Demonstrated self-assembly of biological structures [4] |

| Operon Theory of Gene Regulation | Jacob, Monod (1961) | Used bacterial mutants to study isolated metabolic pathways | Revealed fundamental mechanisms of genetic control [4] |

| Restriction Enzymes | Arber, Smith, Nathans (1970s) | Isolation of bacterial enzymes that cut specific DNA sequences | Enabled recombinant DNA technology and genetic engineering [4] |

These breakthroughs share a common methodological thread: the isolation of individual components from their complex cellular environments to establish causal relationships. The success of these approaches cemented reductionism as the dominant paradigm in molecular biology throughout the latter half of the 20th century.

Experimental Protocols in Reductionist Research

Reductionist approaches typically follow a consistent methodological pattern that has proven enormously successful:

System Simplification: Complex biological systems are reduced to more manageable components. For example, using reporter fusions to specific genes (such as ctxA cholera toxin gene) to identify environmental conditions regulating toxin production, thereby reducing complicating experimental variables [4].

Component Isolation: Biological molecules are purified from their native environments. The critical experiment by Avery, MacLeod, and McCarty demonstrating DNA as the transforming principle required isolation of DNA free from other cellular constituents [4].

In Vitro Reconstitution: Biological function is demonstrated using purified components alone. The reassembly of tobacco mosaic virus from separated RNA and protein components showed that complex biological assembly could occur without cellular machinery [4].

Genetic Dissection: Specific genes are manipulated (through mutation, deletion, or overexpression) to determine their function. Screening Salmonella mutants for survival in cultured macrophages provides predictive information about mammalian infection capability [4].

The following diagram illustrates the typical workflow of reductionist experimental design in molecular biology:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Reductionist molecular biology research relies on a specific set of research reagents and methodologies that enable the dissection of complex systems. These tools form the essential toolkit for conducting the experiments that drove the molecular biology revolution.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents in Reductionist Molecular Biology

| Research Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Reporter Gene Fusions | Isolate and study regulation of specific genetic elements | ctxA cholera toxin gene fusions to study environmental regulation [4] |

| Bacterial Mutants | Identify gene function by studying loss-of-function variants | Salmonella mutants screened for survival in cultured macrophages [4] |

| Cell-Free Systems | Study molecular processes without complex cellular environment | Cell-free fermentation systems demonstrating non-vitalistic nature of biochemistry [7] |

| Knockout Organisms | Determine gene function by targeted deletion | Gene knockout experiments in mice to infer role of individual genes [15] |

| Purified Molecular Components | Study molecules in isolation from native environment | Isolated DNA demonstrating transformation principle; TMV RNA and coat protein self-assembly [4] |

These core reagents and methodologies enabled researchers to implement the reductionist program by isolating individual components from complex biological systems. The reporter gene systems, for instance, allowed scientists to study gene regulation while reducing confounding variables present in intact organisms [4]. Similarly, knockout organisms (despite some limitations due to redundancy and pleiotropy) enabled the assignment of function to specific genes by observing the consequences of their absence [15].

Emergence of Holistic Challenges to Reductionism

Despite its celebrated successes, the reductionist approach has demonstrated significant limitations when confronting the inherent complexity of biological systems. These limitations have prompted the development of more holistic approaches, particularly systems biology, which seeks to understand biological systems as integrated wholes rather than collections of isolated parts [4].

The concept of emergent properties represents a fundamental challenge to strict reductionism. Emergent properties are system characteristics that cannot be predicted or explained solely by studying individual components in isolation [15]. A classic example is water: detailed knowledge of molecular structure of H₂O does not predict the emergent property of surface tension [4]. In biological systems, consciousness and mental states represent complex emergent phenomena that cannot be fully explained by reducing them to chemical reactions in neurons, despite the claims of some neuroscientists [15].

Practical limitations of reductionism have become increasingly apparent in biomedical research. In drug discovery, the number of new drugs approved annually has declined significantly despite massive investments in reductionist-based high-throughput screening, combinatorial chemistry, and genomics approaches [15]. This disappointing performance has been attributed, at least in part, to reductionism's underestimation of biological complexity [15]. Similarly, knockout experiments in mice frequently yield unexpected results—sometimes showing no effect when eliminating genes considered essential, or producing completely unanticipated phenotypes—highlighting the limitations of studying individual genes in isolation from complex genetic networks [15].

The following diagram illustrates key limitations of the reductionist approach that holistic methods seek to address:

Specific experimental evidence demonstrates these limitations. Studies of Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) signaling show that mice deficient in TLR4 are highly resistant to purified lipopolysaccharide but extremely susceptible to challenge with live bacteria [4]. This illustrates the critical difference between studying isolated microbial constituents versus intact microbes—a distinction recognized by journals like Infection and Immunity, which now prefer studies of whole organisms [4]. Similarly, the experience of pain altering human behavior cannot be adequately explained by reducing it to lower-level chemical reactions in neurons, as the pain itself has causal efficacy that is not reducible to its constituent processes [15].

Comparative Analysis: Reductionist vs. Holistic Approaches

The comparison between reductionist and holistic approaches reveals distinct strengths and limitations for each methodology. Rather than representing mutually exclusive paradigms, they often function best as complementary approaches to biological investigation.

Table 3: Reductionist vs. Holistic Approaches in Molecular Biology

| Aspect | Reductionist Approach | Holistic/Systems Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Individual components in isolation | Systems as integrated wholes |

| Methodology | Studies parts separately | Studies interactions between parts |

| Explanatory Power | Strong for linear causality | Addresses emergent properties and network behavior |

| Technological Requirements | Standard molecular biology techniques | High-throughput omics technologies, computational modeling |

| Typical Data Output | Detailed mechanistic understanding of specific elements | Comprehensive datasets capturing system dynamics |

| Strengths | Precise, mechanistic insights; establishes causal relationships | Captures complexity, network properties, and context dependence |

| Limitations | May miss system-level interactions and emergent properties | Can be overwhelmed by complexity; may lack mechanistic detail |

The reductionist approach excels at establishing precise mechanistic relationships and causal connections—it can definitively show that a specific gene or molecule is necessary for a particular function [4]. However, it struggles to explain how these components interact within complex networks or how emergent properties arise from these interactions [15]. The holistic approach, exemplified by systems biology, addresses these limitations by studying systems-level behaviors but may lack the precise mechanistic detail that reductionism provides [4].

This dichotomy represents what some have called a "false dichotomy" [4], as both approaches provide valuable but limited information. Molecular biology and systems biology are "actually interdependent and complementary ways in which to study and make sense of complex phenomena" [4]. This complementary relationship is increasingly recognized in modern research, where reductionist methods identify key components whose interactions are then studied using holistic approaches.

Contemporary Synthesis: Integrating Approaches in Modern Biology

Contemporary molecular biology increasingly recognizes that reductionism and holism are not opposed methodologies but rather complementary approaches that together provide a more complete understanding of biological systems [4]. This synthesis leverages the strengths of both perspectives while mitigating their respective limitations.

Systems biology has emerged as a primary framework for this integration, combining detailed molecular insights from reductionism with holistic perspectives on dynamic interactions within biological systems [16]. Systems biology employs both "bottom-up" approaches (starting with molecular properties and deriving models that can be tested) and "top-down" approaches (starting from omics data and seeking underlying explanatory principles) [4] [16]. The bottom-up approach begins with foundational elements, developing interactive behaviors of each component process and then combining these formulations to understand system behavior [16]. The top-down approach begins with genome-wide experimental data and seeks to uncover biological mechanisms at more granular levels [16].

Advanced technologies now enable this integrative approach. Single-cell sequencing technologies reveal heterogeneity within cell populations that was previously obscured, bridging molecular detail with cellular context [17] [18]. Network science analyzes interactions between biomolecules using graph theory, identifying complex patterns that generate scientific hypotheses about health and disease [18]. Integrative biology utilizes holistic approaches to integrate multilayer biological data, from genomics and transcriptomics to proteomics and metabolomics, providing a more comprehensive understanding of human diseases [18].

The following diagram illustrates how integrated approaches combine reductionist and holistic perspectives:

This integrated approach is particularly valuable for understanding complex diseases. For example, type 2 diabetes involves multiple behavioral, lifestyle, and genetic risk factors with impaired insulin secretion, insulin resistance, kidney malfunction, inflammation, and neurotransmitter dysfunction all contributing to the disease state [18]. A purely reductionist approach focusing on individual molecular components cannot adequately address this complexity, while a purely holistic approach might lack the mechanistic detail needed for targeted interventions. The integration of both perspectives provides a more powerful framework for understanding and treating such complex conditions.

The historical triumphs of reductionism in molecular biology are undeniable, having provided fundamental insights into life's molecular machinery and established causal relationships between specific genes, molecules, and biological functions. The approach remains essential for establishing mechanistic understanding at the molecular level. However, the limitations of reductionism when confronting biological complexity have become increasingly apparent, prompting the development and integration of more holistic approaches.

Contemporary molecular biology research benefits from integrating both perspectives, leveraging reductionism's precision with holism's contextual understanding. This synthesis enables researchers to both establish causal mechanisms and understand how these mechanisms operate within complex biological systems. As molecular biology continues to evolve, the productive tension between these approaches will likely continue to drive scientific progress, with each methodology compensating for the limitations of the other in the ongoing effort to understand the complexity of life.

The landscape of molecular biology research is defined by a fundamental philosophical and methodological tension: reductionism versus holism. For decades, reductionism—the approach of breaking down complex biological systems into their individual components to understand fundamental mechanisms—has been the cornerstone of scientific discovery, yielding extraordinary insights into the molecular basis of life [8] [4]. This paradigm is epitomized by molecular biology's focus on isolating specific genes, proteins, and pathways. However, an increasing backlash has emerged against the limitations of pure reductionism, driven by the recognition that complex biological phenomena often possess emergent properties that cannot be predicted or explained by studying isolated parts alone [4] [19]. This has catalyzed a resurgence of holistic thinking, exemplified by fields like systems biology, which aims to understand biological systems as integrated and indivisible wholes by examining the dynamic interactions within complex networks [4] [7].

This guide provides an objective comparison of these competing approaches, framing them not as mutually exclusive adversaries but as complementary perspectives. We will evaluate their performance through key experimental data, detailed methodologies, and practical applications in drug discovery, providing researchers with a structured analysis to inform their scientific strategies.

Comparative Analysis: Reductionism vs. Holism at a Glance

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, strengths, and limitations of reductionist and holistic approaches in biological research.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of Reductionist and Holistic Approaches

| Aspect | Reductionist Approach | Holistic Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Core Philosophy | Breaking down systems to constituent parts; whole is sum of parts [8] [20]. | Studying systems as integrated wholes; whole is greater than sum of parts [8] [21]. |

| Primary Focus | Isolated components (e.g., single genes, proteins, pathways) [4]. | Interactions, networks, and emergent properties [4] [7]. |

| Methodology | Controlled experiments isolating single variables [20] [21]. | High-throughput data collection (e.g., genomics, proteomics) and computational modeling [4]. |

| Key Strength | Enables precise, causal mechanistic insights and targeted interventions [4] [20]. | Captures system-wide complexity and context-dependent behaviors [8] [21]. |

| Key Limitation | Risks oversimplification; may miss critical higher-level interactions [4] [19]. | Can be technologically challenging and complex to interpret; may lack mechanistic clarity [4] [21]. |

| Representative Field | Molecular Biology | Systems Biology [4] [7] |

Experimental Evidence: Case Studies in Drug Discovery and Disease Research

The Reductionist Success: Targeted Drug Design

The development of drugs through rational design is a quintessential achievement of the reductionist paradigm.

Table 2: Reductionist Approach in Rational Drug Design

| Experimental Aspect | Reductionist Protocol & Findings |

|---|---|

| Core Premise | A disease can be understood by the action of a few key enzymes; a drug can be designed to mimic a specific enzymatic substrate [22]. |

| Methodology | 1. Target Identification: Select a specific biological target (e.g., a single enzyme or receptor) implicated in a disease [22].2. Structural Analysis: Elucidate the 3D structure of the target's active site via X-ray crystallography or NMR.3. Molecular Docking: Use computational modeling (e.g., QM/MM calculations) to study interactions between the target and potential drug candidates [22].4. Synthesis & Testing: Synthesize the lead compound and assay its activity in vitro on the isolated enzyme [22]. |

| Key Strength | Provides a clear, mechanistic understanding of drug-target interaction and enables the development of highly specific inhibitors [22]. |

| Key Limitation | The simplified model may not predict a drug's effect in a whole organism, where off-target effects and complex network physiology come into play [22]. |

The Holistic Resurgence: Systems Biology in Cancer Research

Holistic approaches challenge the single-target dogma, particularly in complex diseases like cancer.

Table 3: Holistic Approach in Cancer Research

| Experimental Aspect | Holistic Protocol & Findings |

|---|---|

| Core Premise | Cancer is a disease of multifactorial origin; treatment must consider the entire cellular network and tissue microenvironment [22]. |

| Methodology | 1. High-Throughput Data Collection: Use genomics, proteomics, and transcriptomics to profile tumors [4].2. Network Modeling: Build computational models of protein interaction networks or metabolic pathways to identify critical nodes [4].3. Contextual Validation: Study drug effects not just on isolated cancer cells but within tissue architectures and microenvironments that can restrict or promote tumor growth [22]. |

| Key Finding | Research by Pierce et al. demonstrated that malignant neoplastic cells can differentiate into benign cell types when placed in a normal microenvironment, refuting the purely genetic "once a cancer cell, always a cancer cell" dogma [22]. |

| Key Strength | Reveals emergent properties of the system, such as how network robustness or the tissue context can dictate disease progression and treatment response [4] [22]. |

Visualizing the Complementary Workflow

The following diagram illustrates how reductionist and holistic methodologies can be integrated in a modern research pipeline, such as in drug discovery.

Diagram 1: Integrated Research Workflow in Modern Biology

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The choice between reductionist and holistic methodologies dictates the required research materials. The table below details key reagents and their functions.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function | Primary Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Specific Enzyme Inhibitors | Blocks the activity of a single, purified target protein to study its specific function and validate it as a drug target. | Reductionism [22] |

| Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) Kits | Amplifies and quantifies specific DNA sequences, enabling the study of individual genes. | Reductionism |

| Reporter Gene Assays (e.g., ctxA fusion) | Measures the regulation of a single gene of interest under different environmental conditions by linking it to a detectable signal. | Reductionism [4] |

| Microarray & RNA-Seq Kits | Allows for the simultaneous measurement of expression levels of thousands of genes, providing a global transcriptomic profile. | Holism [4] |

| Proteomic Profiling Kits | Enables high-throughput identification and quantification of proteins from a complex biological sample. | Holism [4] |

| Cell Culture Models of Tumor Microenvironment | Advanced in vitro systems that co-culture cancer cells with stromal cells to study the impact of the tissue context on drug response. | Holism [22] |

The historical debate between reductionism and holism is not a battle to be won but a dialectic to be synthesized [8] [4] [19]. The backlash against pure reductionism is not a rejection of its power but a recognition of its limitations when applied to the inherent complexity of biological systems. The most productive path forward for molecular biology and drug development lies in a complementary approach that leverages the precision of reductionist methods to ground-truth the insights gleaned from holistic, system-level analyses [8] [4] [22]. This integrated strategy, harnessing the strengths of both paradigms, promises to accelerate the discovery of robust scientific truths and the development of more effective, network-aware therapeutic interventions.

Molecular biology is fundamentally shaped by two competing philosophical approaches: reductionism and holism. Reductionism, which has driven the field for decades, posits that complex systems are best understood by dissecting them into their constituent parts and studying their individual properties [4] [14]. In contrast, holism—often embodied by modern systems biology—argues that phenomena arise from the interconnectedness of all components within a system, and that these emergent properties cannot be predicted from the parts alone [4] [23]. This guide objectively compares the performance of these frameworks, providing experimental data and methodologies that illustrate their respective strengths and limitations in a research context.

Core Conceptual Comparison

The reductionist and holistic approaches differ in their fundamental assumptions, goals, and explanations of biological phenomena. The table below outlines their key conceptual distinctions.

Table 1: Foundational Principles of Reductionist and Holistic Frameworks

| Feature | Reductionist Approach | Holistic (Systems) Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Breaks down systems into isolated components for detailed study [4] [14]. | Studies systems as integrated wholes, focusing on interactions and networks [4] [23]. |

| Primary Goal | Identify linear, causal mechanisms and isolate fundamental building blocks [4]. | Understand emergent properties and system-level behaviors that arise from interconnectedness [23] [7]. |

| View on Emergence | Considers emergent properties as explainable by the underlying parts, given sufficient data [4]. | Views emergence as a fundamental, often non-predictable, outcome of complex interactions [23] [24]. |

| Explanation of Causality | Largely linear cause and effect (e.g., Gene A → Protein B) [4]. | Circular causality through feedback loops; cause and effect are diffuse and dynamic [23]. |

| Typical Methodology | Isolated, controlled experiments (e.g., in vitro assays) [4]. | Integrative, high-throughput omics and computational modeling [25] [26]. |

Experimental Evidence and Performance Data

The practical performance of these frameworks is evaluated through their success in explaining biological phenomena and driving drug discovery. The following experiments highlight the types of data and insights each approach generates.

Experiment 1: Investigating Immune Response to Pathogens

This experiment compares how each framework studies the host immune response to a bacterial pathogen like Salmonella.

Table 2: Experimental Comparison: Immune Response to Pathogens

| Experimental Aspect | Reductionist Protocol & Findings | Holistic/Systems Biology Protocol & Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Aim | Identify the specific function of a single Toll-like receptor (TLR4) in detecting lipopolysaccharide (LPS) [4]. | Understand the network of host-pathogen interactions during live infection and identify emergent dynamics [4] [26]. |

| Key Protocol | 1. Use purified LPS to stimulate cultured immune cells or recombinant TLR4 receptors.2. Measure downstream cytokine production in isolation.3. Utilize knockout mice lacking TLR4 to confirm its specific role [4]. | 1. Infect a live mouse model with Salmonella.2. Perform simultaneous multi-omic analysis (transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) on host cells and bacteria over time.3. Integrate data to reconstruct a dynamic interaction network [4] [26]. |

| Key Findings | TLR4 is critical for sensing purified LPS. TLR4-deficient mice are highly resistant to LPS shock [4]. | TLR4-deficient mice are extremely susceptible to live bacterial infection, a counter-intuitive result showing the system's compensatory mechanisms cannot be predicted from isolated components [4]. |

| Performance Insight | Excellent for establishing precise, causal molecular mechanisms. | Essential for understanding clinically relevant, complex phenotypes that emerge in vivo. |

The workflow for the holistic approach in this context can be visualized as an iterative cycle of experimentation and modeling:

Experiment 2: Target Discovery in Cancer Research

This case examines the historical and modern approaches to understanding tumorigenesis, showcasing the predictive power of integrative thinking.

Table 3: Experimental Comparison: Cancer Research Insights

| Experimental Aspect | Reductionist Protocol & Findings | Holistic/Integrative Protocol & Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Aim | Identify and characterize the function of individual oncogenes and tumor-suppressor genes (e.g., via gene sequencing and in vitro functional assays) [27]. | Predict the fundamental principles of malignant transformation through observation of biological systems [27]. |

| Key Protocol | 1. Sequence tumor genomes to find mutated genes.2. Transfer candidate genes into cell lines and monitor proliferation.3. Study protein function in isolated signaling pathways [27]. | 1. Observe chromosome behavior and instability in sea urchin eggs and parasitic worms (Ascaris).2. Correlate abnormal chromosomal complement with uncontrolled growth.3. Formulate a predictive theory based on cytological and embryological principles [27]. |

| Key Findings | Detailed mechanistic understanding of specific proteins like p53 and Ras in cell cycle control [27]. | Boveri's 1914 hypothesis accurately predicted the roles of chromosome instability, oncogenes, tumor-suppressor genes, and tumor predisposition long before their molecular identification [27]. |

| Performance Insight | Powerful for detailing mechanisms after a target is known. | Powerful for generating novel, foundational hypotheses by observing emergent system-level properties. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The choice of experimental approach dictates the required reagents and tools. Below is a comparison of essential materials for each methodology.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions by Approach

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Reductionist Approach | Function in Holistic Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Molecular Components(e.g., LPS, recombinant proteins) | Isolates a single variable to establish direct, causal molecular interactions in controlled in vitro settings [4]. | Used as a precise perturbation tool to observe system-wide ripple effects in integrated models [4]. |

| Reporter Fusions(e.g., ctxA-gfp) | Studies the regulation of a single gene of interest under specific, simplified environmental conditions [4]. | Tracks the dynamic activity of multiple genes simultaneously within a genetic network in a live host or complex environment [4]. |

| Gene-Specific Knockout Models | Determines the non-redundant function of a single gene by observing the resulting phenotypic defect [4]. | Reveals network robustness, redundancy, and compensatory pathways when the system adapts to the missing component [4]. |

| High-Throughput Omics Kits(e.g., for RNA-Seq, Metabolomics) | Limited use; may profile a specific pathway in response to a targeted intervention. | Core technology for simultaneously quantifying thousands of molecules (genes, proteins, metabolites) to build system-level network maps [26]. |

Analysis of Strengths and Limitations

A balanced view requires acknowledging the inherent trade-offs of each framework, as summarized below.

Table 5: Framework Performance: Strengths and Limitations

| Aspect | Reductionism | Holism |

|---|---|---|

| Strengths | - Proven track record of mechanistic discoveries (e.g., DNA as genetic material) [4].- Enables high-precision, controlled experiments.- Foundation for targeted drug design. | - Captures emergent properties and system-level dynamics (e.g., ecosystem stability, disease resilience) [23] [26].- Identifies network-based drug targets and complex biomarkers.- Provides a more realistic context for in vivo translation. |

| Limitations | - Can overlook system-wide feedback and compensatory mechanisms, leading to failed translations [4] [25].- May promote a narrow view that underestimates biological complexity [25] [27]. | - Can generate overwhelming data with low signal-to-noise ratio [4].- Risk of descriptive rather than mechanistic insight [4].- Computationally intensive and requires sophisticated modeling expertise. |

The fundamental logical relationship between the two approaches, and how they lead to different types of understanding, can be summarized as follows:

The experimental data and comparisons presented demonstrate that reductionism and holism are not mutually exclusive but are, in fact, interdependent and complementary [4]. The reductionist approach provides the essential, high-resolution parts list, while the holistic framework reveals the emergent principles that govern how these parts function together as a system. The future of molecular biology research, particularly in complex areas like drug development for multifactorial diseases, lies in a deliberate integration of both paradigms. Research strategies should leverage the precision of reductionist tools to probe mechanisms within the contextual richness provided by holistic, system-level models.

Practical Implementation in Research and Therapeutic Development

Reductionism is a foundational approach in molecular biology that involves breaking down complex biological systems into their constituent parts to understand the whole [15]. This methodology is epitomized by the belief, as stated by Francis Crick, that the ultimate aim of modern biology is "to explain all biology in terms of physics and chemistry" [15]. Reductionists analyze larger systems by dissecting them into individual pieces and determining the connections between these parts, operating under the assumption that isolated molecules and their structures possess sufficient explanatory power to provide understanding of the entire system [15]. This approach has been particularly valuable in molecular biology, allowing researchers to unravel chemical bases of numerous living processes through careful isolation and study of linear pathways and individual components.

The reductionist agenda has dominated molecular biology for approximately half a century, with scientists employing this method to make significant advances in understanding cellular processes [15]. By focusing on simplified experimental systems and isolating specific variables, reductionism has enabled researchers to establish causal relationships with mathematical precision, often achieving confidence levels exceeding 95% in well-designed studies [28]. This methodological reductionism represents one of three primary forms of reductionism in scientific inquiry, alongside ontological reductionism (the belief that biological systems consist of nothing but molecules and their interactions) and epistemological reductionism (the idea that knowledge in biology can be reduced to knowledge in physics and chemistry) [4] [29].

Core Principles and Applications

Fundamental Concepts of Reductionist Methodology

Reductionist methodology in molecular biology is characterized by several key principles. First, it employs decompositional analysis, breaking down complex systems into their simplest components to study them in isolation [15] [8]. This approach allows researchers to analyze a larger system by examining its pieces and determining the connections between parts, with the fundamental assumption that the properties of isolated molecules provide sufficient explanatory power to understand the entire system [15]. Second, reductionism relies on linear causality, investigating straightforward cause-and-effect relationships within biological systems, such as how Gene A activates Protein B, which then inhibits Process C [15]. This perspective stands in contrast to holistic approaches that recognize complex, non-linear interactions within biological networks.

A third key principle is controlled experimentation, which involves isolating specific variables in simplified systems to establish clear causal relationships [28]. This methodology enables researchers to systematically vary independent variables while controlling confounding factors, often using random assignment of participants or samples to treatment and control groups to minimize bias [28]. The emphasis on molecular-level explanation represents a fourth principle, with reductionism striving to explain biological phenomena primarily through the physicochemical properties of molecules, down to the atomic level [15]. This perspective reflects the belief that because biological systems are composed solely of atoms and molecules without 'spiritual' forces, they should be explicable using the properties of their individual components [15].

Applications in Molecular Biology and Drug Discovery

Reductionist techniques have found widespread application across various domains of molecular biology and biomedical research. In gene function analysis, researchers employ methods like single-gene knockouts to determine the role of individual genes, systematically inactivating or removing genes considered essential to infer their function through observed phenotypic changes [15]. This approach has been instrumental in establishing gene-function relationships, though it has limitations when genes show redundancy or pleiotropy [15]. In drug discovery, reductionism has guided target-based approaches focused on single proteins or pathways, with the pharmaceutical industry investing approximately $30 billion annually in research and development strategies based on high-throughput screening, combinatorial chemistry, genomics, proteomics, and bioinformatics [15]. These approaches aim to identify specific molecular targets for therapeutic intervention.

Pathway mapping represents another significant application, where reductionist methods are used to delineate linear signaling cascades and metabolic pathways [15]. By studying these pathways in isolation, researchers have identified key regulatory nodes that could be targeted for therapeutic benefit. Additionally, in vitro model systems, including cell-free assays and purified component systems, allow researchers to study biological processes without the complexity of whole organisms [15]. While these simplified systems provide valuable insights, their limitations become apparent when findings cannot be replicated in intact organisms or human subjects [15].

Table: Key Applications of Reductionist Techniques in Molecular Biology

| Application Domain | Specific Techniques | Primary Contributions |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Function Analysis | Gene knockouts, RNAi, CRISPR-Cas9 | Establishment of gene-function relationships, identification of essential genes |

| Drug Discovery | High-throughput screening, target-based drug design | Identification of potential drug targets, development of targeted therapies |

| Pathway Analysis | Biochemical reconstitution, inhibitor studies | Delineation of linear signaling pathways, identification of key regulatory nodes |

| Structural Biology | X-ray crystallography, Cryo-EM | Atomic-level understanding of molecular structures and interactions |

| Diagnostic Development | Biomarker identification, assay development | Creation of specific molecular diagnostics for disease detection |

Comparative Analysis: Reductionist vs. Holistic Approaches

The debate between reductionism and holism represents a fundamental dialectic in modern biological research [8] [14]. While reductionism strives to understand biological phenomena by reducing them to a series of levels of complexity with each lower level forming the foundation for the subsequent level, holism claims that there independently exist phenomena arising from ordered levels of complexity that have intrinsic causal power and cannot be reduced in this way [14]. This tension between approaches has become increasingly prominent since the landmark discovery of the double-helix structure of DNA in 1953, which gave rise to the field of molecular biology that studies life at the molecular level [14].

Holistic approaches, often embodied by systems biology, emphasize the fundamental interconnectedness of biological components and recognize that biological specificity results from the way components assemble and function together rather than from the specificity of individual molecules [15]. This perspective has gained traction as limitations of strict reductionism have become apparent, particularly when dealing with emergent properties that resist prediction or deduction through analysis of isolated components [15]. Emergent properties represent a key distinction from resultant properties, which can be predicted from lower-level information—for example, while the mass of a protein assembly equals the sum of masses of its components, the taste of saltiness from sodium chloride is not reducible to the properties of sodium and chlorine gas [15].

Table: Comparison of Reductionist and Holistic Approaches in Biological Research

| Aspect | Reductionist Approach | Holistic Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Individual components and linear pathways | Systems-level interactions and networks |

| Methodology | Isolation, controlled experimentation, decomposition | Integration, modeling, emergent property analysis |

| Causal Perspective | Upward causation (molecular states determine higher-level phenomena) | Accepts downward causation (higher-level systems influence lower-level configurations) |

| Explanatory Power | Strong for linear, causal relationships within simple systems | Superior for complex, non-linear interactions in biological networks |

| Key Limitations | Underestimates biological complexity, misses emergent properties | Can lack precision, more challenging to implement experimentally |

| Representative Techniques | Gene knockouts, in vitro assays, pathway inhibition | Omics technologies, network modeling, computational simulation |

The comparison reveals that reductionism and holism are not truly opposed but rather represent complementary ways of studying biological systems [4]. Each approach has distinct limitations: reductionism may prevent scientists from recognizing important relationships between components in their natural settings and appreciating emergent properties of complex systems, while holism can lack the precision of reductionist methods and face challenges in discerning fundamental principles within complex systems due to confounding factors like redundancy and pleiotropy [4]. Modern research increasingly recognizes that methodological reductionism and holism represent alternative approaches to understanding complex systems, with each providing useful but limited information [4].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Experimental Workflows

Reductionist research employs carefully controlled experimental workflows designed to isolate specific components and linear pathways from complex biological systems. A fundamental protocol involves pathway component isolation, which begins with cell lysis under controlled conditions to preserve molecular interactions, followed by fractionation techniques including differential centrifugation, column chromatography, and affinity purification [15]. These methods allow researchers to separate cellular components based on size, charge, or binding specificity, effectively isolating individual elements from complex mixtures. Quality control measures, such as SDS-PAGE and Western blotting, verify the purity and identity of isolated components throughout the process.

For linear pathway reconstruction, researchers utilize a systematic approach combining biochemical reconstitution and targeted inhibition. This protocol involves purifying individual pathway components, then systematically recombining them in vitro to reconstitute specific signaling events [15]. Researchers employ selective inhibitors, activators, or neutralizing antibodies to establish causal relationships between pathway components, monitoring outputs through phospho-specific antibodies for signaling pathways or substrate conversion assays for metabolic pathways. Dose-response relationships and kinetic analyses further strengthen causal inferences, providing quantitative assessment of component interactions within the reconstructed pathway.

Validation and Analysis Methods

Single-gene perturbation studies represent a cornerstone reductionist technique for establishing gene function. This methodology utilizes CRISPR-Cas9, RNA interference, or traditional homologous recombination to systematically disrupt specific genes of interest [15]. Researchers then conduct phenotypic characterization across multiple cellular assays, comparing experimental groups to appropriate controls. Genetic rescue experiments, which reintroduce functional gene versions, provide crucial validation of observed effects. The integration of data from complementary perturbation methods strengthens conclusions about gene function, helping address potential off-target effects.