Resurrecting the Past for Future Cures: A Modern Guide to Validating Ancestral Protein Functions In Vivo

Ancestral protein reconstruction (APR) has emerged as a powerful tool for understanding molecular evolution and engineering novel biologics.

Resurrecting the Past for Future Cures: A Modern Guide to Validating Ancestral Protein Functions In Vivo

Abstract

Ancestral protein reconstruction (APR) has emerged as a powerful tool for understanding molecular evolution and engineering novel biologics. This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to design, execute, and troubleshoot in vivo validation studies for resurrected ancestral proteins. We explore foundational concepts, detail modern methodologies integrating phylogenetic analysis with structural data from tools like AlphaFold 2, address common pitfalls in experimental design, and establish robust validation strategies comparing ancestral proxies to modern counterparts. By synthesizing recent advances, this guide aims to bridge the gap between computational predictions of ancient protein functions and their rigorous confirmation in living systems, thereby unlocking their potential for therapeutic discovery and fundamental biological insight.

The Why and How of Ancestral Protein Resurrection: Principles and Phylogenetics

Ancestral Protein Reconstruction (APR) is a computational and experimental technique for inferring the sequences of ancient proteins from contemporary sequences and "resurrecting" them in the laboratory for functional study. Also known as Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction (ASR), this method allows scientists to travel back in time to answer fundamental questions about molecular evolution, protein function, and ancient environments. This guide defines APR, outlines its core objectives with supporting experimental data, and details the protocols and reagents essential for validating ancestral protein function, particularly within the context of in vivo research. By comparing data across multiple studies, we provide a framework for researchers to critically evaluate APR methodologies and their applications in basic science and drug development.

Ancestral Protein Reconstruction (APR) is a technique in molecular evolution that uses the genetic sequences of modern organisms to computationally infer the sequences of ancient proteins that existed in extinct life forms, followed by their synthesis and experimental characterization [1] [2]. The foundational principle of APR is that closely related species have similar DNA and protein sequences. By comparing these sequences across a phylogeny, scientists can deduce the sequences of their common ancestors [1]. The method was first suggested in 1963 by Linus Pauling and Emile Zuckerkandl, who proposed that ancient biomolecules could be reconstructed to study evolutionary history, a field they termed "Paleobiochemistry" [1]. Early pioneering work in the 1990s on ribonucleases demonstrated the feasibility of this approach, and with advances in sequencing, computing, and gene synthesis, it has since become a powerful tool for exploring deep evolutionary history [3].

APR operates on the understanding that modern proteins are the descendants of ancient precursors that have diversified through gene duplication and sequence changes over billions of years [3]. The technique does not claim to recreate the one true ancestral sequence with absolute certainty. Instead, it generates a sequence that is statistically likely to be very similar to the ancient protein and, crucially, is expected to share its functional properties [1]. This is consistent with the "neutral network" model of protein evolution, which posits that at any evolutionary node, a population of genotypically different but phenotypically similar protein sequences likely existed [1].

Key Objectives of APR and Experimental Validation

The application of APR spans a wide range of scientific objectives, from understanding evolutionary mechanisms to engineering modern therapeutics. The table below summarizes the primary objectives, key experimental findings, and the in vivo validation context.

Table 1: Key Objectives and Experimental Evidence in Ancestral Protein Reconstruction

| Objective | Key Experimental Findings | Supporting Data & In Vivo Context |

|---|---|---|

| Trace Functional Evolution | Reconstruction of animal Dicer helicase ancestors revealed a gradual loss of ATPase function in the vertebrate lineage, linked to the emergence of RIG-I-like receptors [4]. | Biochemical assays showed ancestral Dicer possessed dsRNA-stimulated ATPase activity, which was lost in vertebrates. This suggests a shift in antiviral defense mechanisms during evolution [4]. |

| Identify Key Functional Residues | Study of ancestral hormone receptors and steroid receptors identified specific residues determining binding specificity, which were obscured in horizontal comparisons of extant proteins [3] [2]. | The "vertical" historical approach of APR isolates the chronology of mutations, allowing researchers to pinpoint residues responsible for functional shifts that are difficult to identify by other methods [3]. |

| Deduce Ancient Environmental Conditions | Reconstruction of thioredoxin enzymes dating back ~4 billion years found ancestral versions had significantly elevated thermal and acidic stability compared to modern counterparts [1]. | Increased thermostability of resurrected proteins is often correlated with hypothesized higher ancient environmental temperatures, providing indirect evidence of historical habitats [1]. |

| Engineer Proteins with Enhanced Properties | Ancestral Factor VIII (FVIII) variants were reconstructed, showing improved biosynthesis, specific activity, and reduced immunogenicity compared to modern human FVIII [5] [6]. | In vivo studies in hemophilia A mice showed ancestral FVIII transgenes (e.g., An-53) yielded higher plasma FVIII activity levels than modern FVIII, demonstrating superior therapeutic potential for gene therapy [5]. |

| Study the Evolution of Protein Complexes | APR was used to infer the ancestral state of protein-interaction networks, predicting an ancient core of the Commander complex with more recent additions in tetrapods [7]. | Analysis of over 16,000 mass spectrometry experiments allowed for the estimation of ancestral protein interactions, providing insights into the assembly and evolution of complex cellular machinery [7]. |

Methodological Approaches: From Sequence to Resurrection

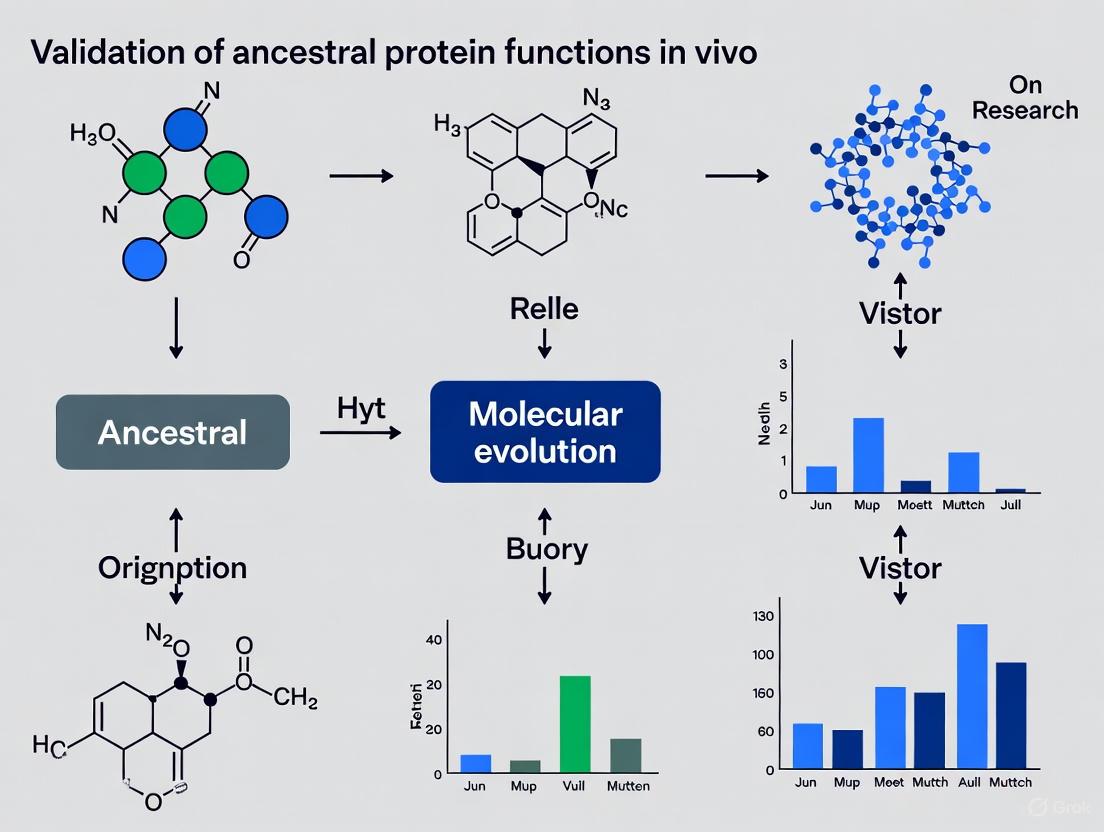

The workflow of APR is methodical, involving sequential steps from data collection to experimental testing. The diagram below illustrates this comprehensive process.

Computational Reconstruction Protocols

The core computational challenge of APR is to infer the most probable sequence at the internal nodes of a phylogenetic tree.

Multiple Sequence Alignment and Phylogeny: The process begins with gathering modern protein sequences from databases, which are then aligned into a Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) to identify homologous positions [1] [8]. A phylogenetic tree is inferred from this alignment, often using methods like maximum likelihood or Bayesian inference [8]. The quality of this tree is critical for the accuracy of the entire reconstruction [8].

Reconstruction Algorithms: Several statistical methods can be used to infer ancestral states:

- Maximum Parsimony (MP): This early method finds the tree that requires the smallest number of evolutionary changes to explain the modern sequences [3]. While simple, it often oversimplifies evolution and is generally considered less reliable, especially over deep time scales [1].

- Maximum Likelihood (ML): Currently a popular approach, ML uses an explicit model of sequence evolution to find the ancestral sequence that has the highest probability (likelihood) of giving rise to the observed modern sequences [9] [1] [8]. A potential drawback is that by always choosing the single most probable residue, ML can overestimate ancestral protein stability [9].

- Bayesian Inference (BI): This method samples ancestral sequences from a posterior probability distribution, which accounts for uncertainty in the reconstruction [10] [9]. Instead of one "best guess" sequence, BI produces a set of plausible sequences. This approach has been shown to reduce bias in estimating ancestral protein properties like thermostability [9].

A key consideration is rate variation across sites. Evolutionary rates are not uniform across all positions in a protein; residues critical for structure or function evolve more slowly. Modern protocols account for this, often by modeling rate variation with a gamma distribution, which significantly improves the accuracy of distance estimation and ancestral reconstruction [8].

Experimental Validation and In Vivo Challenges

Once ancestral sequences are reconstructed and synthesized, they are expressed and purified for characterization.

In Vitro Characterization: The initial biochemical and biophysical analysis is typically performed in a controlled test tube environment (in vitro). This includes measuring enzyme activity, substrate specificity, thermal stability, and structural properties [1]. A common observation is "ancestral superiority," where resurrected ancestral proteins display higher stability and catalytic promiscuity than their modern counterparts [1]. However, this trend could sometimes be an artifact of reconstruction biases and requires careful controls [9] [1].

The In Vivo Context: Validating ancestral protein function within a living organism (in vivo) is the gold standard for understanding its true biological role but presents significant challenges [1]. The cellular environment of a modern organism is different from the ancient one, and it is difficult to mimic ancient cellular conditions. A 2015 study highlighted that the "ancestral superiority" observed in vitro was not recapitulated in vivo, underscoring the importance of this level of validation [1]. Successful in vivo studies, such as those demonstrating the efficacy of ancestral FVIII in mouse models of hemophilia A, show the translational potential of APR [5].

The following diagram outlines the key decision points for designing a robust APR study, leading to conclusive in vivo validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successfully conducting an APR study requires a suite of specialized computational and laboratory reagents. The following table details key resources and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for APR Studies

| Category | Reagent / Solution | Function in APR Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Tools | ANCESCON, PAML, PHYLIP, PAUP* | Software packages for phylogenetic inference and ancestral sequence reconstruction; they implement algorithms like ML and BI to calculate ancestral states [9] [8]. |

| Gene Synthesis | Codon-optimized synthetic genes | De novo synthesis of the inferred ancestral DNA sequences, optimized for expression in the chosen host organism (e.g., human cell lines) [5]. |

| Expression Systems | Cell lines (e.g., HEK293), AAV/lentiviral vectors, Hydrodynamic plasmid DNA infusion | Production of the ancestral protein in a laboratory setting. Different systems are used for in vitro protein production and for in vivo gene therapy/delivery models [5]. |

| Purification Materials | SP-Sepharose, Source-Q chromatography resins, Tricorn columns | Purification of recombinantly expressed ancestral proteins for in vitro biochemical and biophysical assays [5]. |

| Analytical Assays | Thermal shift assays, enzyme activity kits, Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Characterization of ancestral protein properties, including thermostability, specific activity, and ligand-binding affinity [4] [1]. |

| In Vivo Models | Murine hemophilia A model | Testing the therapeutic efficacy and functional performance of resurrected ancestral proteins in a live animal model, providing the most physiologically relevant data [5]. |

Ancestral Protein Reconstruction has established itself as a uniquely powerful method for exploring protein evolution and engineering. By moving beyond a purely horizontal comparison of modern sequences, APR's vertical, historical approach allows researchers to trace the evolutionary trajectory of protein functions, identify key genetic determinants, and deduce historical environmental conditions. While computational methods continue to advance—with Bayesian approaches helping to mitigate historical biases—the ultimate validation of ancestral protein function requires robust in vivo testing. As the case studies of Dicer helicase and Factor VIII illustrate, the insights gained from APR not only illuminate deep evolutionary history but also provide a novel strategy for optimizing modern protein therapeutics, offering direct value to drug development professionals.

In the quest to understand the intricate relationship between protein sequence, structure, and function, two distinct explanatory frameworks have emerged: the functionalist paradigm and historical biochemistry. The functionalist paradigm has long dominated biochemistry, operating on the core premise that a protein's existing structure is best explained by its modern biological function [11]. This approach effectively rationalizes protein features by how they enable current physiological roles, creating a useful abstraction that distills complex structures down to functional essentials [11]. However, this paradigm struggles to explain why proteins with identical functions can have vastly different structures, or why many protein features exist that appear to have no direct functional purpose [11].

Historical biochemistry, particularly through ancestral protein reconstruction (APR), has emerged as a powerful complementary approach. By statistically inferring ancestral protein sequences from evolutionary models, synthesizing them, and experimentally characterizing their properties, researchers can trace how functions evolved through deep time [11] [4]. This vertical analysis through evolutionary history reveals how historical contingency, structural constraints, and functional optimization have collectively shaped modern proteins—addressing fundamental questions that the functionalist paradigm alone cannot answer.

Theoretical Foundations and Key Limitations

The Functionalist Paradigm: Strengths and Blind Spots

The functionalist approach in biochemistry is characterized by its emphasis on explaining biological phenomena through the physical properties of their underlying molecular structures [11]. As Francis Crick famously asserted, "If you want to understand function, study structure" [11]. This framework has advanced the reductionist program in biochemistry, successfully explaining how specific structural features enable biological functions, such as how the atomic structure of potassium channels explains their ion selectivity [11].

However, this paradigm suffers from three significant limitations:

- It cannot explain structural differences among proteins with identical functions. Functionally defined groups like carbonic anhydrases, alcohol dehydrogenases, and serine proteases contain members with the same biochemical activity but vastly different overall structures, as they evolved independently from different ancestral proteins [11].

- It implicitly assumes optimal functional adaptation. Functionalist biochemistry often presumes that all aspects of proteins have been optimized for their functions, ignoring how historical constraints and non-adaptive processes shape protein architecture [11].

- It struggles to explain how sequence encodes structure and function. The functionalist approach cannot easily address why specific sequences produce particular structures and functions, as the sequence-structure-function relationship emerges from historical evolutionary processes [11].

Philosophical Context: Functionalism as an Explanatory Strategy

The functionalist-structuralist debate has deep roots in biological thought, arguably dating back to Aristotle [12]. Functionalism in biology represents the view that "with respect to organic form, structure is explained in terms of function" [12]. This perspective can be understood as an explanatory strategy where the explanandum (thing to be explained) is organic form, and the explanans (explaining thing) is functional needs [12]. In this framework, structure exists because of its functional consequences—a perspective that has persisted through radical changes in biological theory from creationism to modern evolutionary biology [12].

Methodological Comparison: Horizontal vs. Vertical Analysis

Comparative Biochemistry: Horizontal Analysis of Extant Proteins

Traditional comparative biochemistry employs horizontal analysis, comparing related modern proteins to identify sequence differences responsible for functional variations [11]. While theoretically straightforward, this approach faces significant practical challenges:

Table 1: Limitations of Horizontal Comparative Analysis

| Limitation | Description | Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Epistatic Interactions | Effects of mutations depend on genetic background [11]. | Horizontal swaps often produce nonfunctional proteins [11]. |

| Experimental Inefficiency | Must address all sequence differences between homologs [11]. | Astronomical increase in required experiments with moderate sequence divergence [11]. |

| Historical Obscuration | Modern sequences contain all changes since common ancestor [11]. | Difficult to distinguish functionally relevant changes from neutral drift [11]. |

Historical Biochemistry: Vertical Analysis Through Ancestral Reconstruction

Ancestral protein reconstruction enables vertical analysis by isolating evolutionary changes to specific branches on a phylogenetic tree [11]. The APR workflow typically involves:

Figure 1: Ancestral Protein Reconstruction Workflow. The process begins with extant sequences and progresses through phylogenetic analysis, ancestral inference, and experimental characterization to test evolutionary hypotheses.

This approach offers distinct advantages over horizontal comparisons. By focusing on the specific changes that occurred during defined evolutionary intervals, APR dramatically reduces the number of candidate mutations that need to be tested [11]. It also minimizes epistatic effects by introducing historical substitutions into sequence backgrounds similar to those in which they originally occurred [11].

Case Studies in Historical Biochemistry

Resurrecting Mamba Aminergic Toxins

A groundbreaking study demonstrated how APR could illuminate the evolution of mamba venom toxins, which target aminergic receptors with exceptional specificity [13]. Researchers resurrected six ancestral toxins (AncTx1-AncTx6) and discovered:

Table 2: Key Findings from Mamba Toxin Reconstruction

| Ancestral Toxin | Functional Characterization | Evolutionary Insight |

|---|---|---|

| AncTx1 | Most α1A-adrenoceptor selective peptide known [13]. | Revealed evolutionary pathway to extreme specificity. |

| AncTx5 | Most potent inhibitor of three α2 adrenoceptor subtypes [13]. | Demonstrated ancestral potency exceeding modern variants. |

| AncTx Variants | Identified positions 28, 38, 43 as key affinity modulators [13]. | Revealed epistasis in toxin evolution. |

The study successfully associated pharmacological profiles with specific functional substitutions, demonstrating how APR can guide protein engineering by identifying key functional residues [13]. This approach generated a small but functionally rich library of variants, avoiding the need to screen overwhelming numbers of random mutants [13].

Tracing the Loss of Dicer Helicase Function

APR revealed how human Dicer lost ATP hydrolysis capability essential for antiviral defense in invertebrate Dicers [4]. By reconstructing ancestral Dicer helicase domains, researchers determined:

- Ancient animal Dicer possessed robust ATPase function stimulated by dsRNA [4]

- This capability declined through deuterostome evolution and was lost entirely in vertebrates [4]

- Loss correlated with diminished dsRNA binding affinity [4]

- Restoration of ATPase function required substitutions distant from the catalytic pocket [4]

This study provided mechanistic insight into how functional specialization occurred during animal evolution, with RIG-I-like receptors potentially replacing Dicer's antiviral role in vertebrates [4].

Evolution of Enzyme Specificity in Lactate Dehydrogenase

Contrary to the hypothesis that ancestral proteins were generalists, APR revealed that pyruvate specificity in apicomplexan lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) evolved de novo from a malate dehydrogenase (MDH)-specific ancestor [14]. The common ancestor (AncM/L) showed strong preference for oxaloacetate over pyruvate (>10⁷-fold), not the expected generalist profile [14]. The shift to pyruvate specificity occurred through:

- A six-amino acid insertion that dramatically increased pyruvate efficiency (>12,000-fold)

- An Arg102Lys substitution that further reduced ancestral oxaloacetate activity

Crystal structures of ancestral proteins showed how the insertion introduced a Trp residue that improved hydrophobic packing with pyruvate's methyl group [14]. This case demonstrates that new specific functions can evolve through simple genetic changes altering key electrostatic and steric complementarity determinants [14].

Practical Implementation: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methods for Ancestral Protein Reconstruction

| Reagent/Method | Function in APR | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple Sequence Alignment Algorithms | Identifies homologous positions across extant proteins [11]. | Critical for accurate phylogenetic inference and ancestral reconstruction. |

| Probabilistic Models of Evolution | Estimates substitution patterns and evolutionary rates [11]. | Model selection significantly impacts reconstruction accuracy [9]. |

| Maximum Likelihood/Bayesian Inference | Statistically infers ancestral states at each sequence position [11] [9]. | Bayesian methods may reduce stability overestimation bias [9]. |

| Gene Synthesis Services | Produces DNA encoding reconstructed ancestral sequences [13]. | Enables experimental characterization of inferred sequences. |

| Protein Expression & Purification Systems | Produces ancestral proteins for functional testing [13] [4]. | Mammalian, bacterial, or cell-free systems selected based on protein requirements. |

| Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy | Verifies proper folding of reconstructed proteins [13]. | Confirms ancestral proteins adopt expected secondary structures. |

Addressing Methodological Challenges in APR

Managing Reconstruction Uncertainty

A significant concern in APR is the statistical uncertainty inherent in reconstructing ancient sequences. The maximum likelihood (ML) approach yields a single "best guess" sequence, but sites are often reconstructed ambiguously, with multiple plausible amino acid states [15]. Research has demonstrated several strategies to address this uncertainty:

- Single-variant analysis: Creating and testing proteins containing plausible alternate states at individual ambiguous sites [15]

- "Worst plausible case" (AltAll) protein: Incorporating all plausible alternate states into a single protein to test robustness to extreme uncertainty [15]

- Bayesian sampling: Generating multiple sequences by sampling from the posterior probability distribution at each site [9] [15]

Notably, studies have found that qualitative functional inferences are generally robust to sequence uncertainty, even when scores of alternative amino acids are incorporated [15]. However, quantitative parameters show more variation, suggesting that robustness testing is particularly important when precise biochemical characterization is desired [15].

Avoiding Reconstruction Biases

Computational studies have revealed that reconstruction methods can introduce systematic biases. For example, maximum parsimony and maximum likelihood methods tend to overestimate protein thermostability because they eliminate slightly detrimental variants that are less frequent [9]. Bayesian methods that sample from the posterior distribution appear to reduce this bias [9]. This highlights the importance of method selection and validation in APR studies.

The functionalist paradigm and historical biochemistry represent complementary rather than competing approaches to understanding protein function. Where functionalism excels at explaining how modern structures enable current functions, historical biochemistry reveals why proteins have their specific architectures and how new functions emerged through evolutionary history. The integration of these approaches provides a more complete framework for understanding protein sequence-structure-function relationships.

For drug development professionals, historical biochemistry offers valuable insights for protein engineering. By revealing the evolutionary trajectories and structural constraints that shaped modern protein families, APR provides guidance for designing novel therapeutics with enhanced specificity and potency [13] [16]. The resurrection of ancestral toxins with exceptional receptor selectivity demonstrates the potential of evolution-guided protein engineering for developing targeted therapeutics [13].

As the field advances, the integration of ancestral reconstruction with emerging protein design technologies—including AI-based structure prediction and de novo design—promises to further accelerate our ability to understand and engineer protein function [16]. This synthesis of historical and synthetic approaches will continue to transform both basic research and therapeutic development in the years ahead.

Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction (ASR) is a powerful phylogenetic technique that allows scientists to infer the genetic sequences of ancient proteins, creating a tangible bridge to the past for experimental exploration. By analyzing the molecular evolution of protein families, ASR generates explicit, testable hypotheses about how historical changes in protein sequence have shaped their structural and functional characteristics over evolutionary timescales [17]. This methodology has transitioned from a theoretical exercise to an indispensable experimental approach, particularly in the field of drug development where it offers novel avenues for protein therapeutic optimization [5].

The core workflow from multiple sequence alignment to statistical inference represents a critical pipeline for validating ancestral protein functions in vivo. When properly executed, this process enables researchers to move beyond correlation-based observations to direct experimental testing of evolutionary hypotheses. The resurrection and characterization of ancestral proteins provides concrete, experimentally validated insights into ancient evolutionary processes and helps illuminate the complex relationship between protein sequence, structure, and function [17]. This is especially valuable for pharmaceutical applications, where ancestral proteins with enhanced stability, expression, or reduced immunogenicity can offer significant advantages over their modern counterparts [5].

Multiple Sequence Alignment: The Critical Foundation

Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) establishes the foundational framework for all subsequent phylogenetic analysis and ancestral reconstruction. The reliability of MSA results directly determines the credibility of downstream biological conclusions, making this initial step paramount to the entire workflow [18]. Alignment algorithms systematically identify homologous positions across sequences, creating a matrix where evolutionarily related sites are arranged in columns, thus enabling meaningful comparative analysis.

Alignment Tool Comparison

Different alignment tools employ distinct algorithms and heuristic strategies to balance the competing demands of accuracy, speed, and scalability, particularly when handling large datasets common in modern genomic studies.

Table 1: Comparison of Multiple Sequence Alignment Tools

| Tool | Primary Algorithm | Key Strengths | Optimal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| MUSCLE [19] | Progressive alignment with iterative refinement | High accuracy for evolutionarily related sequences; consistency in aligned regions | Phylogenetic analyses requiring high-quality alignments of moderately large datasets |

| Clustal Omega [19] | Progressive alignment with HMM refinement | Scalability for large datasets; parallel processing capabilities; memory efficiency | Large-scale genomic/proteomic datasets where computational efficiency is crucial |

| T-Coffee [19] | Hybrid progressive alignment with consistency | Combines accuracy with speed; emphasis on alignment consistency | Critical alignments where accuracy outweighs computational time concerns |

| MAFFT [20] | Fast Fourier Transform approaches | Speed with high accuracy; various options for different accuracy/speed tradeoffs | Large-scale alignments, including those with long sequences or many taxa |

Post-Alignment Processing and Quality Considerations

MSA is inherently an NP-hard problem, making it theoretically impossible to guarantee a globally optimal solution [18]. Consequently, post-processing methods have emerged as an important strategy for improving initial alignment quality. These methods refine preliminary alignments to correct errors and optimize the arrangement of sequences. Advancements in this area focus on developing more efficient algorithms and enhancing alignment quality through post-processing optimization, both crucial for improving the overall accuracy of phylogenetic inferences [18].

Phylogenetic Tree Construction: Mapping Evolutionary Relationships

Once a reliable MSA is obtained, the next critical step involves inferring phylogenetic relationships among the sequences. Phylogenetic trees serve as fundamental pillars in biological research, elucidating evolutionary relationships among organisms and offering profound insights into their shared history [20]. These trees provide the graphical and mathematical structure upon which ancestral sequences are statistically inferred.

Tree-Building Methodologies

Phylogenetic inference methods fall into two primary categories, each with distinct advantages and limitations:

- Distance-based methods calculate genetic distances between sequence pairs and use the resulting matrices to build trees [20]. These approaches are computationally efficient but may lose information by reducing sequence data to pairwise distances.

- Character-based methods—including maximum parsimony, maximum likelihood, and Bayesian inference—compare all sequences in an alignment simultaneously, considering one site at a time to calculate scores for each possible tree [20]. These methods typically provide more accurate trees but are computationally intensive, as identifying the tree with the highest score requires comparing a vast number of possible topologies.

Computational Advances in Phylogenetics

The exponential growth of genetic data has intensified computational burdens in phylogenetic analysis, creating substantial time constraints and increasing demands for computational resources [20]. Recent innovations address these challenges through various strategies. Tools like FastTree, PhyloBayes MPI, ExaBayes, and RAxML-NG implement heuristic tree search methods that accelerate and parallelize calculations [20]. Meanwhile, machine learning approaches such as PhyloTune leverage pretrained DNA language models to rapidly integrate new taxa into existing phylogenetic frameworks by identifying taxonomic units and extracting high-attention genomic regions for targeted subtree updates [20].

Statistical Inference of Ancestral Sequences: Computational Resurrection

With a robust phylogenetic tree in place, researchers can statistically infer the sequences of ancestral proteins at various nodes within the tree. This computational "resurrection" represents the core of ASR, transforming phylogenetic hypotheses into testable protein sequences.

Reconstruction Methods and Evolutionary Models

The accuracy of ancestral reconstruction depends critically on both the inference method and the evolutionary model employed:

- Parsimony methods identify ancestral states that minimize the total number of evolutionary changes across the tree [21]. While computationally efficient, these methods are known to produce systematic biases, particularly for deeper nodes where multiple changes at single sites become more probable [21].

- Likelihood-based methods employ explicit models of sequence evolution to compute the probability of ancestral states given the observed data and phylogenetic tree. These methods have been demonstrated superior to parsimony, with one study showing probability values of correctly reconstructed amino acids ranging from 91.3% to 98.7% for likelihood analysis compared to significantly lower accuracy for parsimony [22].

- Averaging weighted by posterior probabilities (AWP) addresses reconstruction bias by averaging over multiple possible reconstructions at each site, using their posterior probabilities as weights [21]. This approach substantially reduces systematic biases inherent in methods relying on single best reconstructions.

- Expected Markov Counting (EMC) is a newer method that produces maximum-likelihood estimates of substitution counts for any branch under a nonstationary Markov model [21]. This approach has shown particular promise for accurately recovering substitution counts even under complex scenarios of parameter fluctuation.

Table 2: Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction Methods

| Method | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parsimony [21] | Minimizes number of evolutionary changes | Computational simplicity; intuitive logic | Systematic biases; poor performance with divergent sequences |

| Maximum Likelihood [22] | Maximizes probability of observed data under evolutionary model | Statistical robustness; higher accuracy than parsimony | Computationally intensive; dependent on model specification |

| AWP [21] | Averages over reconstructions weighted by posterior probabilities | Reduces bias compared to single reconstruction | Model misspecification can still affect weights |

| EMC [21] | Maximum-likelihood estimates under nonstationary model | Handles complex nonstationary evolution | Increased computational complexity |

Addressing Model Selection and Uncertainty

The choice of evolutionary model significantly impacts reconstruction accuracy. Stationary models like HKY assume consistent substitution patterns across lineages, while nonstationary models (e.g., HKY-NH, HKY-NHb, nonstationary GTR) allow parameters such as base composition and substitution rates to vary across branches [21]. Research demonstrates that the nonstationary GTR model, used with AWP or EMC, accurately recovers substitution counts even in cases of complex parameter fluctuations, whereas stationary models can produce substantial biases when evolutionary processes are nonstationary [21].

Statistical uncertainty in reconstructed sequences is inevitable, particularly at sites with ambiguous support for multiple amino acid states. However, experimental studies have demonstrated that qualitative conclusions about ancestral proteins' functions and the effects of key historical mutations are generally robust to this uncertainty, with similar functions observed even when scores of alternative amino acids are incorporated [23]. The "worst plausible case" method, which incorporates the alternative amino acid state at every ambiguous site into a single protein, provides an efficient strategy for characterizing functional robustness to large amounts of sequence uncertainty [23].

Experimental Validation: From In Silico to In Vivo Analysis

Computational predictions of ancestral sequences must ultimately be validated through experimental characterization, creating a critical bridge between bioinformatics and wet-lab biology. This transition from in silico inference to in vivo validation represents the definitive test of ASR hypotheses.

Functional Characterization of Ancestral Proteins

Comprehensive experimental characterization typically assesses multiple biochemical and biophysical properties relevant to protein function:

- Biosynthetic efficiency measures protein expression and folding capabilities, with some ancestral FVIII variants showing 9-14-fold higher expression than human FVIII [5].

- Biochemical stability assesses structural integrity under various conditions, with ancestral FVIII proteins in the rodent lineage displaying progressively extended decay half-lives (up to 15.6 minutes for An-68 compared to more rapid decay in primate/hominid variants) [5].

- Functional activity quantifies catalytic or binding capabilities using appropriate activity assays.

- Immunological profiling evaluates immune recognition, with certain ancestral FVIII variants showing markedly reduced cross-reactivity to monoclonal antibodies targeting clinically relevant epitopes [5].

In Vivo Therapeutic Applications

The ultimate validation of ancestral protein function often occurs in vivo, particularly for therapeutic applications. For coagulation Factor VIII, ancestral variants have demonstrated superior performance in hemophilia A mouse models, with ED50 estimates of 89 and 47 units/kg for ancestral variants An-53 and An-68 respectively [5]. In gene therapy contexts, ancestral FVIII transgenes produced higher plasma FVIII activity levels compared to human FVIII or human/porcine hybrids following hydrodynamic plasmid DNA infusion and intravenous AAV vector delivery [5].

Research Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of the ASR workflow requires specialized reagents and computational resources carefully selected for each stage of the process.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Category | Specific Items | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Tools | Phylogenetic software (RAxML, PhyloBayes), Alignment tools (MUSCLE, MAFFT), ASR algorithms | Sequence analysis, tree building, ancestral inference |

| Laboratory Materials | SP-Sepharose, Source-Q chromatography resins, Tricorn columns [5] | Protein purification and separation |

| Molecular Biology Reagents | Lipofectamine 2000, Power SYBR PCR Master Mix, RNAlater [5], custom synthetic genes | Nucleic acid manipulation, transfection, gene synthesis |

| Experimental Models | Hemophilia A mouse models, cell lines for recombinant protein expression [5] | In vivo and in vitro functional validation |

Visualizing the Workflow

The entire process from sequence collection to functional validation follows a logical, sequential pathway with multiple feedback loops for refinement.

The integrated workflow from multiple sequence alignment through phylogenetic analysis to statistical inference of ancestral sequences represents a powerful framework for probing protein evolution and function. When coupled with robust experimental validation, this approach provides unprecedented insights into molecular evolution while generating novel protein variants with enhanced pharmaceutical properties. The continuing development of more accurate alignment algorithms, sophisticated evolutionary models, and high-throughput characterization methods will further expand the utility of ASR in both basic research and therapeutic applications.

The resurrection of ancestral proteins to study their function in vivo provides a powerful window into molecular evolution. However, the fidelity of these biological insights rests upon a critical, foundational step: the selection of an appropriate evolutionary model to reconstruct the ancestral sequences. An incorrectly chosen model can lead to inaccurate ancestral sequences, potentially causing researchers to draw false conclusions about functional divergence. This guide compares the performance of different evolutionary models and software tools in ancestral sequence reconstruction (ASR), providing experimental data and protocols to inform the selection process for in vivo functional validation studies.

Why Model Selection Matters: Evidence from Experimental Benchmarking

The choice of evolutionary model is not merely a theoretical concern; it has demonstrable, quantitative effects on the accuracy of reconstructed sequences and, more importantly, their biological properties. A key experimental study created a known phylogeny of 19 fluorescent protein (FP) variants to benchmark ASR algorithms against known ancestral genotypes and phenotypes [24]. This benchmark revealed that while all algorithms showed high sequence-level accuracy (97.88-98.17%), they differed significantly in their ability to recover correct protein phenotypes when sequences were incorrectly inferred [24].

Table 1: Performance of ASR Algorithms on Experimental Fluorescent Protein Phylogeny

| Algorithm | Method Category | Rate Variation | Sequence Accuracy | Phenotypic Error (Brightness) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAML_Γ | Bayesian | Gamma distributed | 98.17% | Lowest (p < 0.01 vs. MP) |

| FastML_Γ | Bayesian | Gamma distributed | 98.17% | Lowest (p < 0.01 vs. MP) |

| PAML | Bayesian | Homogeneous | 98.10% | Moderate |

| PHYLO_Γ | Bayesian (aware) | Gamma distributed | 97.88% | Moderate |

| MP | Maximum Parsimony | N/A | 98.03% | Highest |

Bayesian methods incorporating rate variation across sites (discrete gamma distribution Γ) significantly outperformed maximum parsimony (MP) in phenotypic accuracy, particularly for properties like extinction coefficients and brightness (p < 0.01) [24]. This demonstrates that model selection directly impacts the functional characteristics of resurrected proteins—a crucial consideration for in vivo studies where protein abundance and stability influence biological activity.

Comparative Analysis of Evolutionary Modeling Approaches

Model Types and Methodologies

Evolutionary models for ASR differ in their underlying assumptions and computational approaches:

Maximum Parsimony (MP) favors the evolutionary pathway requiring the fewest amino acid changes. While computationally efficient, it often oversimplifies evolution by ignoring multiple substitutions at sites and variation in evolutionary rates across sequences [1] [24].

Maximum Likelihood (ML) methods identify the tree and ancestral sequences with the highest probability of producing the observed data under a specific evolutionary model. ML can incorporate complex evolutionary parameters, including site-specific rate variation and different substitution matrices [25].

Bayesian methods incorporate prior knowledge about evolutionary parameters and use Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling to estimate posterior probabilities of ancestral states. These methods naturally accommodate parameter uncertainty and model complexity, including rate variation across sites [24].

The Critical Role of Rate Variation

A key differentiator in model performance is the handling of evolutionary rate variation across sequence sites. Models that incorporate a discrete gamma distribution (Γ) to account for this variation consistently outperform those assuming rate homogeneity [24]. This is biologically intuitive: in real proteins, active sites and structural residues typically evolve more slowly than surface loops, creating a distribution of evolutionary rates across the sequence.

Specialized Models for Different Protein Types

Evolutionary constraints differ significantly between ordered and disordered proteins. Research comparing models of evolution for these protein classes found that disordered proteins accept more evolutionary changes with nonconservative substitutions, necessitating different substitution matrices than those used for ordered proteins [26]. This suggests that model selection should consider the structural properties of the protein family under investigation.

Experimental Protocols for Model Selection and Validation

Benchmarking Workflow for Model Assessment

For researchers embarking on ASR projects, particularly those aimed at in vivo functional validation, we recommend the following experimental protocol for model selection:

Data Collection and Alignment: Assemble a comprehensive set of homologous sequences and create multiple sequence alignments using different methods (e.g., Muscle, MSAProbs) [25]. Evaluate alignment consistency as disagreements can significantly impact downstream analyses.

Model Testing: Use software such as MEGA or PhyloBot to compare different evolutionary models [27] [25]. These tools provide built-in functions for statistical model selection based on Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) or Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC).

Ancestral Reconstruction: Reconstruct ancestral sequences using at least two different methods (e.g., Bayesian with gamma-distributed rates and maximum likelihood) to assess consistency [24].

Sensitivity Analysis: Perform subsampling analyses to test the robustness of your reconstructions. The ASPEN methodology demonstrates that features robust across subsamples are more likely to be accurate [28].

Experimental Validation: Whenever possible, resurrect multiple variants of contested ancestral residues and test their functional properties in vivo to confirm phylogenetic predictions [24].

ASPEN: A Framework for Quantifying Uncertainty

The ASPEN (Accuracy through Subsampling of Protein Evolution) methodology addresses reconstruction uncertainty by generating ensemble models through sequence subsampling [28]. This approach:

- Quantifies reconstruction uncertainty by subsampling from available ortholog sequences

- Measures the distribution of relationships across hundreds of models

- Identifies topological features most consistent with robust phylogenetic signal

- Provides a meta-algorithm that selects topologies most consistent with features extracted from the ensemble

ASPEN demonstrates that reproducibility across subsamples correlates with accuracy, providing a measurable value for something previously unknowable—the confidence in a single-alignment reconstruction [28].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for ASR

| Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application in ASR |

|---|---|---|---|

| PAML | Software package | Bayesian phylogenetic analysis | Ancestral sequence reconstruction with rate variation models [24] |

| PhyloBot | Web portal | Automated phylogenetics and ASR | User-friendly pipeline integrating alignment, model selection, and reconstruction [25] |

| MEGA | Software package | Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis | Model testing, tree building, and evolutionary distance calculation [27] |

| Experimental Phylogeny | Benchmarking system | Validation of ASR algorithms | Ground-truth testing of reconstructed sequences against known ancestors [24] |

| Fluorescent Proteins | Model system | Phenotypic readout of protein function | Direct visualization of ancestral protein function in vivo [24] |

Emerging Methods and Future Directions

Integrating Language Models and Evolutionary Information

Recent advances in protein language models (pLMs) like ESM-2 offer new approaches for fitness prediction that complement traditional phylogenetic methods [29] [30]. The EvoIF framework integrates within-family evolutionary information from homologous sequences with cross-family structural–evolutionary constraints distilled from inverse folding logits [30]. This fusion of sequence and structural evolutionary information represents a promising direction for improving the accuracy of ancestral sequence inference.

Addressing In Vivo Validation Challenges

A persistent challenge in ASR is the limited number of studies that validate ancestral protein functions in vivo. While in vitro analyses often show ancestral proteins with increased thermostability and catalytic promiscuity, these "ancestral superiority" traits are not always recapitulated in vivo [1]. Future work should focus on:

- Developing models that better predict in vivo functionality

- Incorporating cellular context into evolutionary models

- Increasing the number of in vivo validation studies across diverse protein families

Selecting the best-fitting evolutionary model is not a mere computational formality but a critical determinant of success in ancestral protein resurrection studies. Experimental evidence demonstrates that Bayesian methods incorporating rate variation across sites consistently outperform maximum parsimony and homogeneous models in both sequence accuracy and functional prediction. For researchers planning in vivo functional validation of ancestral proteins, we recommend a rigorous approach that includes model comparison using statistical criteria, sensitivity analysis through subsampling, and experimental validation of contested residues. As the field advances, integrating traditional phylogenetic methods with emerging approaches from protein language modeling and structural bioinformatics promises to further enhance the accuracy and biological relevance of ancestral reconstructions.

Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction (ASR) has emerged as a powerful technique that enables scientists to resurrect ancient proteins, providing a unique window into molecular evolution. This methodology combines phylogenetic analysis with experimental biochemistry to create plausible approximations of proteins that existed deep in the evolutionary past. While ASR generates valuable hypotheses about ancestral gene function, interpreting what these resurrected sequences truly represent requires careful validation, particularly within living systems. This guide examines the core principles of ASR, compares various methodological approaches, and evaluates techniques for validating the functional significance of resurrected ancestral proteins in vivo, offering researchers a framework for critically assessing ASR-based claims in evolutionary and biomedical research.

Principles and Methodologies of Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction

Theoretical Foundations

ASR operates on the principle that closely related species share similar DNA sequences, and by comparing extant sequences across a phylogeny, we can infer probable ancestral states [1]. The technique was first suggested in 1963 by Linus Pauling and Emile Zuckerkandl, who envisioned it as the foundation for a field they termed "Paleobiochemistry" [1]. Modern ASR does not claim to recreate the exact historical sequence but rather generates a sequence that likely represents the functional characteristics of the ancestral protein, operating under the "neutral network" model of protein evolution where genotypically different but phenotypically similar sequences can occupy the same functional space [1].

The accuracy of ASR depends heavily on multiple factors: the quality and diversity of the input sequences, the alignment methodology, the phylogenetic tree construction, and the reconstruction algorithm itself [1] [31]. Importantly, ASR-generated sequences are considered hypothetical approximations of ancient proteins, whose true biological significance must be validated through experimental testing, especially in vivo where full cellular contexts are present [1].

Reconstruction Algorithms and Their Applications

ASR primarily employs three computational approaches, each with distinct strengths and limitations:

Maximum Likelihood (ML) methods predict residues at each position that are most likely to explain the observed extant sequences, using scoring matrices calculated from modern sequences [1]. ML is currently the most widely used approach in ASR studies.

Bayesian methods complement ML approaches but typically produce more ambiguous sequences with probability distributions over possible ancestral states [1]. These are valuable for assessing uncertainty in reconstructions.

Maximum Parsimony (MP) constructs sequences based on a model of sequence evolution that minimizes the number of required changes [1]. MP is often considered less reliable for deep reconstructions as it may oversimplify evolutionary processes.

Recent methodological advances like GRASP (Graphical Representation of Ancestral Sequence Predictions) enable ASR from datasets exceeding 10,000 sequences and better handle insertion and deletion (indel) events using partial order graphs (POGs) [32]. This scalability allows researchers to leverage the rapidly expanding databases of protein sequences for more accurate ancestral inferences.

Table 1: Comparison of Major ASR Computational Approaches

| Method | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum Likelihood | Identifies most probable residues given evolutionary model | High accuracy; models evolutionary rates | Computationally intensive; dependent on model selection |

| Bayesian | Generates probability distributions over possible ancestors | Quantifies uncertainty; incorporates prior knowledge | Produces ambiguous sequences; computationally demanding |

| Maximum Parsimony | Minimizes number of evolutionary changes | Computationally efficient; simple assumptions | Less accurate for deep time; oversimplifies evolution |

| GRASP | Uses partial order graphs for indels | Handles large datasets (>10,000 sequences); models indels effectively | Complex implementation; newer with less established track record |

Experimental Validation of Resurrected Proteins

In Vitro versus In Vivo Assessment

Most ASR studies are conducted in vitro, where resurrected proteins are expressed, purified, and characterized biochemically [1]. This approach has revealed that many ancestral proteins exhibit what has been termed "ancestral superiority" - properties such as increased thermostability, catalytic activity, and promiscuity compared to modern counterparts [1] [33]. For instance, ancestral resurrected thioredoxins demonstrated significantly elevated thermal and acidic stability while maintaining catalytic efficiency similar to modern enzymes [1].

However, the nascent field of evolutionary biochemistry has recognized that in vitro properties do not always translate to cellular environments. Very few ASR studies have been conducted in vivo due to challenges including the lack of suitably ancient genomes, limited model systems, and inability to mimic ancient cellular environments [1]. A 2015 study noted that "ancestral superiority" observed in vitro was not recapitulated in vivo for a specific protein, highlighting the critical importance of cellular validation [1].

Key Methodologies for Functional Validation

Several experimental approaches have been developed to validate the function of resurrected ancestral proteins:

Thermal stability assays using techniques like circular dichroism (CD) to monitor temperature-induced unfolding. This method was used to demonstrate that ancestral 3-isopropylmalate dehydrogenase (IPMDH) enzymes had higher thermal stability (Tm = 88-90°C) compared to extant thermophilic homologs (Tm = 86°C) [33].

Direct in vivo stability measurement through incorporation of structurally non-perturbing binding motifs for bis-arsenical fluorescein derivatives that report unfolding transitions within cells [34]. This approach enables quantitative stability determination in living systems like E. coli.

Enzyme kinetics characterization to determine catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM) across temperatures. Ancestral IPMDHs showed considerably higher low-temperature catalytic activity compared to thermophilic homologs while maintaining thermal stability [33].

Continuous evolution systems like Phage-Assisted Continuous Evolution (PACE) enable laboratory evolution of ancestral proteins to test historical evolutionary trajectories [35]. This approach was used with BCL-2 family proteins to quantify the roles of chance, contingency, and necessity in molecular evolution.

Table 2: Key Biochemical Properties of Resurrected Ancestral Proteins

| Protein | Ancestral Age | Key Biochemical Properties | Validation Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dicer helicase | Ancient animal ancestor | ATP hydrolysis function; dsRNA-stimulated ATPase activity | Biochemical assays; Michaelis constants analysis [4] |

| IPMDH | Bacterial common ancestor | Thermal stability (Tm = 88-90°C); high low-temperature activity | Circular dichroism; enzyme kinetics [33] |

| Thioredoxin | ~4 billion years | Elevated thermal/acidic stability; maintained catalytic efficiency | Thermal denaturation; activity assays [1] |

| BCL-2 family proteins | ~800 million years | Divergent protein-protein interaction specificities | PACE; binding specificity assays [35] |

Case Studies in ASR Validation

Dicer Helicase Domain Evolution

A 2023 study used ASR to resurrect the helicase domain of Dicer proteins across animal evolution, tracing the evolutionary trajectory of ATP hydrolysis function [4]. The research revealed that ancient Dicer possessed ATPase activity that was stimulated by double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), while vertebrate ancestors lost this capability due to reduced affinity for both dsRNA and ATP [4].

Experimental validation showed that reverting residues in the ATP hydrolysis pocket was insufficient to rescue hydrolysis function in vertebrate Dicer, but additional substitutions distant from the active site partially restored ATPase function [4]. This suggests that loss of function resulted from compromised coupling between dsRNA binding and active site conformation, potentially allowed by the emergence of RIG-I-like receptors that took over viral RNA sensing functions in vertebrates [4].

Contingency in BCL-2 Family Protein Evolution

A landmark study combining ASR with continuous evolution technology examined the roles of chance, contingency, and necessity in the evolution of BCL-2 family proteins [35]. Researchers synthesized ancestral BCL-2 proteins from various evolutionary periods and evolved them repeatedly under selection to acquire specific protein-protein interaction functions that emerged historically.

The results demonstrated that "contingency generated over long historical timescales steadily erased necessity and overwhelmed chance" [35]. Evolutionary trajectories launched from phylogenetically distant ancestral proteins yielded virtually no common mutations, even under identical selection pressures. This suggests that patterns of variation in these protein sequences are "idiosyncratic products of a particular and unpredictable course of historical events" [35], highlighting the importance of historical contingency in molecular evolution.

Engineering Ancestral Enzymes for Biotechnology

ASR has proven valuable for creating enzymes with desirable properties for biotechnology. A 2020 study designed two ancestral sequences of 3-isopropylmalate dehydrogenase (IPMDH) using ASR [33]. The resurrected enzymes exhibited higher thermal stability than extant thermophilic homologs while maintaining significantly higher catalytic activity at lower temperatures [33].

Detailed biochemical characterization showed that the ancestral enzymes had catalytic properties similar to mesophilic enzymes despite their thermophilic-level stability, demonstrating that ASR can produce enzymes combining thermophilic stability with mesophilic catalytic efficiency [33]. This suggests ancestral enzymes may provide superior starting points for protein engineering compared to modern extremophilic enzymes, which often exhibit trade-offs between stability and activity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ASR Studies

| Reagent/Technique | Function in ASR | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| GRASP software | Infers ancestral sequences from large datasets (>10,000 sequences); models indel events | Reconstruction of glucose-methanol-choline oxidoreductases, cytochromes P450 [32] |

| Bis-arsenical fluorescein dyes | Report protein unfolding in vivo for direct stability measurement in cellular environments | In vivo stability measurement of cellular retinoic acid-binding protein in E. coli [34] |

| Phage-Assisted Continuous Evolution | Enables continuous directed evolution of ancestral proteins under controlled selection pressures | Evolution of BCL-2 family proteins to acquire historical protein-protein interaction specificities [35] |

| Partial Order Graphs | Represent and infer insertion/deletion events across ancestors | Handling indel events in ancestral sequence reconstruction [32] |

| Heterologous expression systems | Produce resurrected ancestral proteins in model organisms | Expression of ancestral IPMDH in E. coli for biochemical characterization [33] |

Experimental Workflows and Signaling Pathways

The following diagrams illustrate key experimental workflows and conceptual frameworks in ASR validation studies:

ASR Experimental Workflow

Factors Influencing Protein Functional Evolution

Resurrected ancestral sequences represent statistically inferred hypotheses about historical molecular forms that must be rigorously validated through both in vitro and in vivo approaches. While ASR provides powerful insights into evolutionary processes, the true biological meaning of these reconstructed nodes emerges only through experimental testing in appropriate contexts. The growing integration of ASR with directed evolution and continuous evolution platforms offers promising avenues for exploring historical protein sequence space and engineering novel biocatalysts [36]. For researchers in drug development and molecular evolution, critically evaluating ASR studies requires careful attention to both methodological details of reconstruction and the strength of functional validation evidence. As the field advances, increased emphasis on in vivo validation will be essential for fully interpreting what resurrected ancestral sequences truly represent in the context of living systems.

From Sequence to Living System: Methodologies for In Vivo Characterization

The reconstruction of ancestral proteins provides a powerful window into evolutionary history, enabling researchers to test hypotheses about the functions, stability, and mechanisms of ancient biomolecules. This approach has illuminated evolutionary trajectories across diverse protein families, such as the Dicer helicase domain, where ancestral reconstruction revealed key events in the loss of ATPase function during vertebrate evolution [4]. However, a significant challenge in this field lies in the effective synthesis and expression of these inferred ancestral sequences in modern host systems. Since these ancient proteins never existed in contemporary organisms, their codon usage and sequence properties are often incompatible with modern expression hosts, frequently resulting in poor protein yields, improper folding, or complete expression failure.

Successfully bridging this gap requires a sophisticated integration of gene synthesis and multi-parameter expression optimization. This guide objectively compares the tools and methodologies that enable researchers to move from ancestral sequence reconstruction to functional protein characterization, with a specific focus on validating inferred functions in vivo. The process is foundational for making robust conclusions about molecular evolution and for harnessing ancient protein variants for therapeutic development [4].

Comparative Analysis of Codon Optimization Tools

Codon optimization is a critical first step, moving beyond simple codon usage matching to a holistic consideration of multiple sequence parameters. Different tools employ distinct algorithms and weight these parameters differently, leading to variability in the performance of the resulting synthetic genes [37].

Performance Metrics and Tool Comparison

A comprehensive 2025 analysis compared widely used codon optimization tools using industrially relevant proteins expressed in E. coli, S. cerevisiae, and CHO cells [37]. The study evaluated tools based on their ability to align with host-specific codon biases and key parameters like Codon Adaptation Index (CAI), GC content, and mRNA secondary structure.

Table 1: Comparison of Codon Optimization Tool Strategies and Performance

| Tool Name | Optimization Strategy | Key Strengths | Reported Host Organisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| JCat | Codon adaptation based on genome-wide codon usage | Simple, fast; strong alignment with highly expressed genes [37]. | E. coli, S. cerevisiae, CHO [37] |

| OPTIMIZER | User-defined reference set for codon usage | Flexible; allows custom codon usage tables [37]. | E. coli, S. cerevisiae, CHO [37] |

| ATGme | Integrated primer design and optimization | All-in-one solution for synthesis and cloning [37]. | E. coli, S. cerevisiae, CHO [37] |

| GeneOptimizer | Multi-parameter, iterative algorithm | Simultaneously balances >100 parameters; proven high expression [37] [38]. | E. coli, S. cerevisiae, CHO, HEK293 [37] [38] |

| TISIGNER | Structure-aware optimization | Considers mRNA stability and tRNA kinetics; unique approach [37]. | E. coli, S. cerevisiae, CHO [37] |

Table 2: Quantitative Output of Optimization Tools for a Model Protein (Human Insulin in E. coli)

| Tool | Codon Adaptation Index (CAI) | GC Content (%) | mRNA Folding Energy (ΔG) |

|---|---|---|---|

| JCat | 0.89 | 52.1 | -245.3 |

| OPTIMIZER | 0.91 | 50.8 | -251.7 |

| GeneOptimizer | 0.94 | 53.5 | -238.9 |

| TISIGNER | 0.85 | 48.2 | -225.1 |

The data reveals that tools like GeneOptimizer, JCat, and OPTIMIZER tend to produce sequences with high CAI values, indicating strong adaptation to the host's preferred codons [37]. In contrast, tools like TISIGNER may employ different strategies that prioritize other factors, such as mRNA structural stability, sometimes at the expense of a perfect CAI score [37]. This highlights a crucial point: there is no single "best" tool, as the optimal choice depends on the target protein and host system. For ancestral protein studies, where sequences can be particularly challenging, a multi-parameter tool like GeneOptimizer has demonstrated success, with one study showing 86% of optimized genes exhibited significantly increased expression, and protein yields increased by up to 15-fold compared to wild-type sequences [38].

Key Parameters for Effective Optimization

The following parameters are critical for designing genes that express well in modern host systems [37] [39] [38]:

- Codon Adaptation Index (CAI): Measures the similarity between a gene's codon usage and the preferred codon usage of highly expressed genes in the target host. A CAI >0.8 is generally considered optimal for high expression [37] [40].

- GC Content: The percentage of guanine and cytosine bases in the sequence. Optimal ranges are host-specific (e.g., moderate GC is often best for CHO cells), impacting mRNA stability and secondary structure [37].

- mRNA Secondary Structure: Stable secondary structures, especially in the 5' end, can impede translation initiation. Gibbs free energy (ΔG) is a key indicator, where less stable folding (higher ΔG) can facilitate ribosome binding [37] [39].

- Codon Pair Bias (CPB): The non-random usage of pairs of adjacent codons, which can influence translational efficiency and fidelity in the host [37].

Gene Synthesis and Assembly Methodologies

Once a sequence is optimized, it must be synthesized de novo. For ancestral proteins, no natural DNA template exists, making robust and accurate gene synthesis protocols essential [40] [41].

From Oligonucleotides to Full-Length Genes

The foundation of gene synthesis is the assembly of overlapping oligonucleotides into a full-length double-stranded DNA molecule. Key advancements have focused on improving throughput, accuracy, and cost-effectiveness.

Table 3: Comparison of Gene Synthesis and Assembly Techniques

| Method | Principle | Throughput | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polymerase Chain Assembly (PCA) | Single-reaction PCR assembly of a pool of overlapping oligonucleotides [40]. | Medium | Simple and fast; no oligonucleotide phosphorylation required [40]. | Error-prone; requires post-assembly error correction [40]. |

| Two-Step DA-PCR/OE-PCR | Dual Asymmetrical PCR followed by Overlap-Extension PCR [40]. | Medium | Higher accuracy than single-step PCA [40]. | More complex workflow [40]. |

| Microarray-Derived Synthesis | Oligonucleotides synthesized in parallel on a silicon chip via photolithography or ink-jet printing [41]. | Very High | Extremely high throughput; low cost per sequence [41]. | Oligonucleotides are shorter and require amplification; higher initial error rates [41]. |

| Automated Column Synthesizers | Traditional phosphoramidite chemistry on controlled pore glass (CPG) columns [41]. | Low to Medium | High-quality, long oligonucleotides (up to 200 nt); well-established [41]. | Higher cost per sequence; lower throughput [41]. |

Automation is revolutionizing this field. Integrated liquid handling workstations can now perform repetitive synthesis and assembly tasks, reducing manual labor and increasing reproducibility for building large libraries of synthetic genes, a key requirement for screening multiple ancestral variants [41].

Error Correction and Cloning

A major bottleneck in gene synthesis is the accumulation of errors from imperfect oligonucleotides or polymerase mistakes during assembly. Techniques to address this include:

- Oligonucleotide Purification: Using HPLC or PAGE to remove truncated oligonucleotides [41].

- Enzymatic Error Correction: Employing mismatch-cleaving enzymes or selective digestion of non-full-length products [40].

- High-Fidelity Sequencing Verification: Sanger or NGS confirmation of cloned synthetic genes is essential before expression testing.

For cloning, modern Ligation-Independent Cloning (LIC) methods are highly efficient, allowing the direct integration of the synthetic PCR product into an expression vector without the need for restriction enzymes or ligases [40].

Experimental Protocols for Expression Validation

After synthesizing and cloning the optimized ancestral gene, rigorous experimental validation is required to confirm successful expression and function.

Workflow for Ancestral Protein Expression

The following diagram outlines a generalized workflow for expressing and validating a resurrected ancestral protein.

Detailed Methodologies for Key Steps

Protocol 1: Small-Scale Test Expression in E. coli This protocol is adapted for evaluating expression of ancestral protein variants in a high-throughput format [42].

Transformation: Transform the synthesized gene in an expression vector (e.g., pET series) into an appropriate E. coli strain such as:

- BL21(DE3): For standard, non-toxic proteins.

- Rosetta(DE3): Provides tRNAs for rare codons, crucial for non-bacterial ancient sequences [42].

- SHuffle or Origami: For proteins requiring disulfide bond formation [42].

- Lemo21(DE3): Allows tunable expression, ideal for optimizing yields of difficult or toxic proteins [42].

Culture and Induction: Inoculate 2-5 mL of auto-induction media or LB with the appropriate antibiotic. Grow cultures at 37°C until OD600 reaches ~0.6-0.8. Induce protein expression by adding IPTG (typically 0.1-1.0 mM). Lower temperatures (e.g., 16-25°C) and reduced inducer concentrations can be tested to enhance soluble expression [42].

Harvesting: Pellet cells by centrifugation 4-16 hours post-induction. Resuspend in lysis buffer for analysis.

Protocol 2: Functional Assay for a Resurrected Dicer Helicase This specific protocol is based on research that reconstructed ancestral Dicer proteins to trace the evolution of ATP hydrolysis [4].

Protein Purification: Express and purify the ancestral helicase domain (e.g., fused to a His-tag) using immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC).

ATPase Activity Assay:

- Reaction Setup: Incubate the purified protein (e.g., 100 nM) in a buffer containing ATP (e.g., 1 mM) and Mg²⁺. To test for dsRNA stimulation, include a long dsRNA substrate (e.g., 500 ng/μL).

- Detection Method: Use a colorimetric assay (e.g., malachite green) to quantify inorganic phosphate (Pi) released over time. Alternatively, a coupled enzymatic assay using NADH oxidation can monitor ATP consumption.

- Kinetic Analysis: Determine Michaelis constants (KM for ATP) by varying ATP concentration in the presence and absence of dsRNA. As demonstrated in the Dicer study, ancestral forms showed increased ATP affinity (lower KM) in the presence of dsRNA, a property lost in vertebrate ancestors [4].

Protocol 3: Enhancing Solubility via Fusion Tags and Chaperone Co-expression For ancestral proteins that express insolubly in inclusion bodies [43] [42]:

Fusion Partners: Subclone the ancestral gene into vectors encoding solubility-enhancing fusion partners such as Maltose-Binding Protein (MBP), Glutathione-S-Transferase (GST), or Small Ubiquitin-like Modifier (SUMO). Test different tags empirically.

Co-expression with Chaperones: Co-transform the expression vector with a plasmid expressing chaperone systems like GroEL/GroES or DnaK/DnaJ/GrpE. Alternatively, use commercial E. coli strains engineered to overexpress these chaperones.

Solubility Analysis: Lyse the cells and separate the soluble (supernatant) and insoluble (pellet) fractions by centrifugation. Analyze both fractions by SDS-PAGE to determine the distribution of the expressed protein.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Success in ancestral protein expression relies on a carefully selected set of biological reagents and tools.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Ancestral Protein Expression

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Application | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Specialized E. coli Strains | Provides specific cellular environments to aid expression and folding. | Rosetta: Supplies rare tRNAs. SHuffle: Promotes disulfide bond formation. Lemo21(DE3): Allows tunable expression to mitigate toxicity [42]. |

| Tunable Expression Vectors | Plasmid systems with regulated promoters for controlling protein yield. | pET Series (T7 promoter): Strong, IPTG-inducible. pBAD Series (araBAD promoter): Tightly regulated by arabinose. Rhamex Vectors (rhaBAD promoter): Enable fine-tuning of expression levels [42]. |

| Solubility Enhancement Tags | Fusion partners that improve the solubility of recalcitrant proteins. | MBP, GST, SUMO, NusA, Trx. Must often be cleaved off after purification using specific proteases (e.g., TEV, Thrombin) [42]. |

| Chaperone Plasmid Kits | Co-expression plasmids for molecular chaperones that assist in proper protein folding. | Kits for GroEL/GroES and DnaK/DnaJ/GrpE systems. Can be co-transformed or used in engineered strains [43]. |

| Auto-induction Media | Growth media that automatically induces protein expression at high cell density. | Simplifies culture handling; often improves yields for T7/lac-based systems by inducing with lactose after glucose depletion [42]. |

The functional validation of ancestral proteins hinges on overcoming the translational barrier between historical sequence inference and modern laboratory expression. As this guide demonstrates, this requires a strategic and often iterative process. Researchers must select codon optimization tools that balance multiple parameters, employ high-fidelity gene synthesis and assembly methods, and systematically test expression conditions using a toolkit of specialized reagents. The quantitative data and protocols provided here offer a roadmap for comparing and implementing these technologies. By rigorously applying these principles, scientists can robustly build a bridge to the past, uncovering deep evolutionary insights and opening new avenues for protein engineering and therapeutic design.

The determination of protein three-dimensional structure is fundamental to understanding biological function, a principle that becomes critically important when investigating ancestral proteins. In the context of validating ancestral protein functions in vivo, researchers are increasingly leveraging computational structure prediction tools to generate testable hypotheses about ancient biological mechanisms. While experimental methods like X-ray crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) provide high-resolution structural data, they are complex, time-consuming, and expensive [44]. This has created a significant gap between the number of known protein sequences and those with experimentally resolved structures, with Uniprot containing over 229 million protein sequences compared to only approximately 200,000 structures in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) [44].

AlphaFold 2 (AF2), developed by DeepMind, has emerged as a transformative tool that addresses this disparity by predicting protein structures with accuracy competitive with experimental methods [45]. For researchers studying ancestral proteins, where obtaining experimental structures is particularly challenging, AF2 provides a powerful means to generate structural models that can inform hypothesis generation about ancient biological functions. However, understanding the capabilities and limitations of AF2, especially in comparison with its successor AlphaFold 3 (AF3) and other emerging alternatives, is essential for properly interpreting these predictions and designing appropriate validation experiments. This guide objectively compares the performance of these tools and provides methodologies for their application in ancestral protein research.

AlphaFold 2 and 3: Core Architectures and Performance

AlphaFold 2's Technical Foundation and Accuracy