Solving Molecular Dynamics Bond Stretching Errors: From Force Field Pitfalls to Advanced Solutions

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on identifying, troubleshooting, and resolving bond stretching errors in Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations.

Solving Molecular Dynamics Bond Stretching Errors: From Force Field Pitfalls to Advanced Solutions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on identifying, troubleshooting, and resolving bond stretching errors in Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations. We cover the foundational principles of bonded interactions and common pitfalls, explore advanced methodological solutions including reactive force fields and machine learning potentials, outline practical troubleshooting and system optimization strategies, and present rigorous validation and comparative analysis frameworks. By synthesizing the latest methodological advances and practical insights, this guide aims to enhance the reliability and predictive power of MD simulations in biomedical research.

Understanding Bond Stretching: From Harmonic Potentials to Simulation Artifacts

The Fundamentals of Bonded Interactions in MD

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and frequently asked questions (FAQs) for researchers investigating bond stretching errors and their solutions in Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations. This content supports thesis research focused on identifying and resolving inaccuracies in the representation of bonded interactions.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving Instabilities in Stretched Bond Potentials

Problem: Simulation crashes or exhibits unphysical energy increases when bonds are significantly stretched, for instance, during steered MD or in thermal fluctuations at high temperatures.

Background: The harmonic bond potential, ( Vb(r{ij}) = \frac{1}{2}k^b{ij}(r{ij}-b{ij})^2 ), commonly used in Class I force fields like AMBER and CHARMM, is a poor approximation for large deviations from the equilibrium bond length ( b{ij} ) [1] [2] [3]. Its energy increases quadratically and does not describe bond dissociation, which can lead to instabilities when a bond is stretched too far.

Solution: Consider switching to a potential that more accurately describes the energy landscape of a chemical bond.

- Recommended Action: Implement an anharmonic potential.

- Morse Potential: This potential provides a more realistic shape, including a dissociation plateau: ( V{morse} (r{ij}) = D{ij} [1 - \exp(-\beta{ij}(r{ij}-b{ij}))]^2 ) where ( D{ij} ) is the dissociation energy and ( \beta{ij} ) controls the well width [1]. It approximates the harmonic potential for small displacements but allows for bond breaking at large ( r{ij} ).

- Cubic Potential: For a less computationally expensive option that improves upon the harmonic potential, a cubic term can be added: ( Vb(r{ij}) = k^b{ij}(r{ij}-b{ij})^2 + k^b{ij}k^{cub}{ij}(r{ij}-b{ij})^3 ) [1]. Be aware that this potential is asymmetric and can lead to unphysical energies with extreme overstretching.

Validation: After implementing a new potential, rerun your simulation and monitor the total energy and the specific bond distance for stability. Compare the distribution of the bond length in a equilibrium simulation against experimental data or quantum mechanical calculations to validate the new parameterization.

Guide 2: Addressing Systematic Error from Self-Interaction in Stretched Bonds

Problem: Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations used for parametrizing force fields or running ab initio MD (AIMD) systematically underestimate reaction barrier heights. This error is traced to the overstabilization of delocalized electron densities in transition states with stretched bonds [4].

Background: Standard Density Functional Approximations (DFAs) suffer from self-interaction error (SIE), which becomes pronounced when bonds are stretched and electron densities delocalize over multiple atoms. This artificially lowers the energy of the transition state, reducing the calculated reaction barrier [4].

Solution: Apply a self-interaction correction (SIC) method to your DFT calculations.

- Recommended Action: Utilize the Perdew-Zunger SIC (PZSIC) or the locally scaled SIC (LSIC) method [4].

- Workflow:

- Perform a standard DFT calculation to identify the transition state geometry of your reaction.

- Recalculate the single-point energy of the reactants, transition state, and products using the PZSIC or LSIC method.

- These methods remove the one-electron self-interaction error on an orbital-by-orbital basis, which significantly increases the energy of the delocalized transition state relative to the reactants and products.

- Analysis: The SIC contribution to the reaction barrier (( \Delta E^{SIC}_{Total} )) comes mainly from the "participant orbitals" directly involved in the bond-breaking and bond-making process [4].

- Workflow:

Validation: The calculated reaction barrier heights should be closer to high-level quantum chemistry benchmarks or experimental values after applying SIC. The BH76 benchmark set is a standard for validating barrier height predictions [4].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Can I simulate bond breaking and formation in classical MD? No, standard classical MD with harmonic bond potentials cannot simulate bond breaking. The harmonic potential ( kb(r{ij}-r_0)^2 ) increases to infinity as the bond is stretched, preventing dissociation [3]. To model chemical reactions where bonds break and form, you must use either:

- Reactive Force Fields: Such as ReaxFF, which uses a bond-order formalism to allow for dynamic bond formation and breaking [3].

- Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics (AIMD): Which uses quantum mechanics to compute electronic structure and forces on-the-fly, naturally describing bond rearrangements [3].

FAQ 2: Why does my simulation terminate with a "Too many warnings" error when using a GROMOS force field? This is a common warning in GROMACS. The GROMOS force fields were originally parameterized with a "twin-range cut-off" scheme that is now considered physically incorrect. When used with modern, correct integrators, physical properties like density might be inaccurate [5].

- Solution: If you are aware of this issue and have determined the GROMOS force field is still appropriate for your system, you can override the error by adding the command-line flag

-maxwarn 1to yourgmx gromppcommand. It is strongly recommended to check the literature to see if your molecules of interest are affected by this known issue [5].

FAQ 3: What is the difference between a dihedral and an improper dihedral? Both are four-body potentials, but they serve different purposes.

- Proper Dihedral: Describes the rotation around a central bond (e.g., atoms i-j-k-l). Its potential is typically periodic: ( V{Dihed}=k\phi(1+\cos(n\phi-\delta)) ) and is used to control conformational flexibility [1] [2].

- Improper Dihedral: Used to enforce planarity (e.g., in aromatic rings or peptide bonds) or to prevent chirality inversion. It is usually modeled with a harmonic potential: ( V{Improper}=k\phi(\phi-\phi_0)^2 ) [1] [2].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparison of Bond Stretching Potentials in MD

| Potential Form | Mathematical Expression | Key Features | Best Use Cases | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harmonic [1] [2] | ( V = \frac{1}{2}k(r - b)^2 ) | Computationally efficient; good near equilibrium. | Standard MD with Class I force fields (AMBER, CHARMM). | Cannot break bonds; poor for large deviations. |

| Morse [1] | ( V = D_e [1 - \exp(-\beta(r-b))]^2 ) | Includes dissociation energy; anharmonic. | Simulating bond dissociation; spectroscopic studies. | More computationally expensive. |

| Fourth Power (GROMOS) [1] | ( V = \frac{1}{4}k(r^2 - b^2)^2 ) | Computationally efficient (no square root). | GROMOS force field simulations. | Conceptually complex; average bond energy ≠ ( \frac{1}{2}kT ). |

| Cubic [1] | ( V = k(r-b)^2 + k k^{cub}(r-b)^3 ) | Adds anharmonicity; improves IR spectra. | Flexible water models (e.g., Ferguson). | Potential is asymmetric; can be unphysical at large ( r ). |

| FENE [1] | ( V = -\frac{1}{2}kb^2 \log\left(1 - \frac{r^2}{b^2}\right) ) | Finite extensibility; diverges at a set distance. | Coarse-grained polymer simulations. | Not for all-atom biomolecular simulations. |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Bonded Interaction Studies

| Reagent / Method | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Perdew-Zunger (PZSIC) [4] | Removes one-electron self-interaction error in DFT on an orbital-by-orbital basis. | Correcting barrier height underestimation in chemical reactions. |

| Locally Scaled SIC (LSIC) [4] | A SIC method that preserves the accurate description of the uniform electron gas. | Improving predictions of reaction energies and barrier heights over PZSIC. |

| Fermi-Löwdin Orbitals (FLOs) [4] | Localized orbitals used to evaluate SIC energies and identify participant orbitals. | Analyzing which specific orbitals contribute most to SIE in a transition state. |

| NBFIX Corrections [6] | Pair-specific corrections to non-bonded interactions to prevent artificial aggregation. | Improving the balance of interactions in multi-component protein, DNA, and lipid systems. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Correcting DFT Reaction Barriers with Self-Interaction Correction

Purpose: To accurately calculate the energy barrier of a chemical reaction by correcting the self-interaction error in stretched bonds at the transition state.

Methodology:

- System Preparation:

- Optimize the geometries of the reactants (R), products (P), and transition state (TS) using your chosen DFA.

- Confirm the transition state with a frequency calculation (one imaginary frequency).

- Single-Point Energy Calculations:

- Perform a standard DFA single-point energy calculation for R, P, and TS.

- Perform a PZSIC or LSIC single-point energy calculation for R, P, and TS using the same geometries. The FLOSIC code or other SIC-enabled software is required [4].

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the uncorrected forward reaction barrier: ( \Delta Ef = E{TS} - ER ).

- Calculate the SIC-corrected forward barrier: ( \Delta Ef^{SIC} = (E{TS} + E{SIC, TS}) - (ER + E{SIC, R}) ).

- Analyze the SIC energy ( E_{SIC} ) by decomposing it into contributions from "participant orbitals" (involved in bond changes) and "spectator orbitals" [4].

Protocol 2: Parametrizing a Morse Potential from Quantum Calculations

Purpose: To derive parameters for a Morse potential to be used in a classical MD simulation for systems where bond anharmonicity is critical.

Methodology:

- Quantum Mechanical Calculation:

- Select a model molecule containing the bond of interest.

- Perform a series of single-point energy calculations, varying the bond length around its equilibrium value to generate a potential energy curve.

- Curve Fitting:

- Fit the calculated energy points to the Morse potential function: ( V{morse} (r{ij}) = D{ij} [1 - \exp(-\beta{ij}(r{ij}-b{ij}))]^2 ).

- The fitted parameters are:

- ( D{ij} ): The dissociation energy (depth of the potential well).

- ( b{ij} ): The equilibrium bond length.

- ( \beta_{ij} ): The parameter controlling the width of the potential well.

- Force Field Implementation:

- Replace the standard harmonic bond potential in your force field with the newly parameterized Morse potential for the specific bond type.

- Validate the new parameter set by running a short MD simulation and comparing the simulated bond length distribution and vibrational frequency to the QM data or experimental spectroscopy data [1].

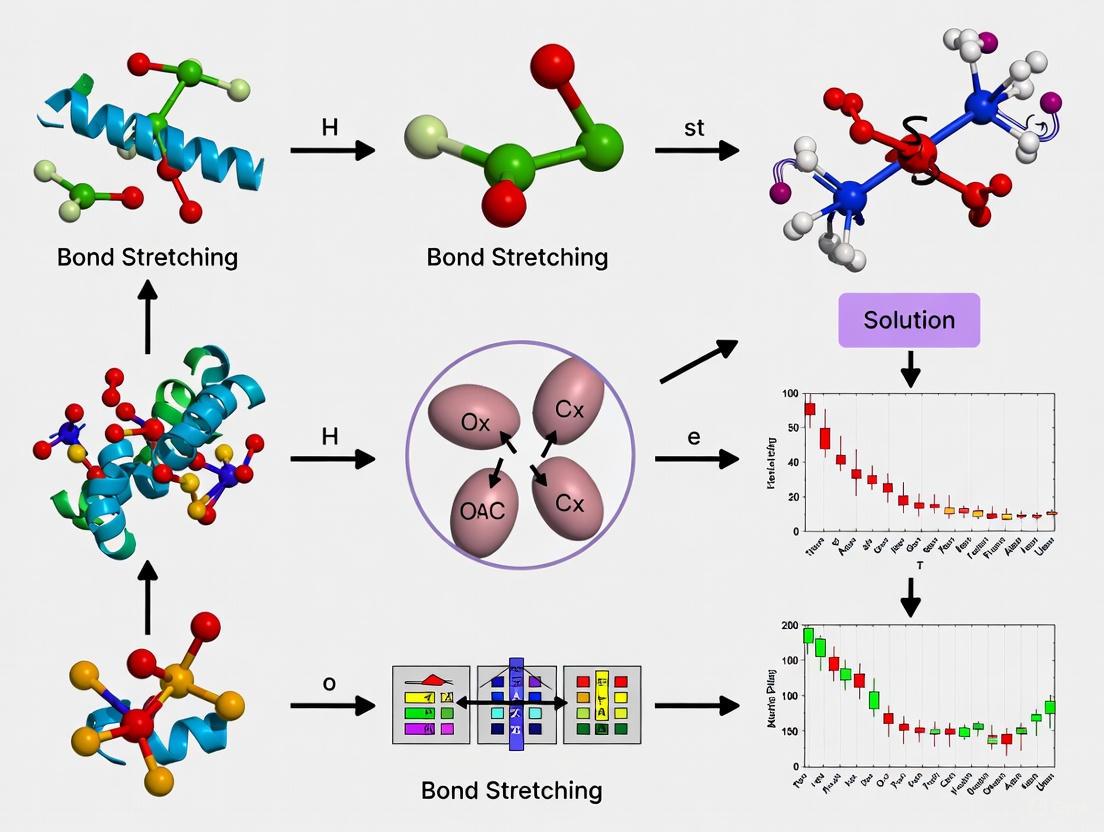

Mandatory Visualization

Bond Potential Energy Diagram

Workflow for Diagnosing Bond Stretching Errors

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What are the fundamental types of bond stretching potentials used in molecular dynamics simulations? The most common bond stretching potentials are the Harmonic potential, the Fourth-power potential (as used in the GROMOS-96 force field), and the Morse potential. Harmonic potentials are simplest and most computationally efficient, but Fourth-power and Morse potentials offer more complex behavior for specific applications. [1] [7]

2. When should I use a Morse potential instead of a standard harmonic potential? Use a Morse potential when your simulation involves bond breaking, requires a more accurate anharmonic representation of bond vibrations, or needs to model the correct dissociation energy. The Morse potential is superior for simulating chemical reactivity and material failure. Harmonic potentials are unsuitable for these cases as they cannot describe bond dissociation. [1] [8] [9]

3. My simulation is unstable when bonds are highly stretched. What could be wrong? This could arise from using a simple harmonic potential for large bond displacements where it is no longer a valid approximation. Consider switching to a Morse potential or a cubic bond stretching potential for anharmonicity. Additionally, ensure your integration timestep is sufficiently small (e.g., 1 fs for the cubic potential) to handle the increased potential sharpness. [1] [8]

4. How do I convert parameters between a harmonic and a Morse potential? The equilibrium bond length ((re)) is typically the same for both. The Morse parameter (\alpha) (or (\beta{ij})) is related to the harmonic force constant ((k^{b,\mathrm{harm}})) and the dissociation energy ((D{ij})) by: [ \alpha{ij} = \sqrt{\frac{k^{b,\mathrm{harm}}{ij}}{2 D{ij}}} ] This ensures the potentials have the same curvature near the equilibrium distance. [1] [10] [8]

5. What does a "Fourth Power Potential" describe, and what are its advantages? The Fourth Power Potential is a computational approximation for bond stretching where the potential energy is given by (Vb(r{ij}) = \frac{1}{4}k^b{ij}(r{ij}^2-b_{ij}^2)^2). Its primary advantage is computational efficiency as it avoids the calculation of a square root. A key disadvantage is that it is not a true harmonic potential, so the average energy of a bond is not exactly (\frac{1}{2}kT). [1]

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inability to Simulate Bond Breaking

- Symptoms: Simulations fail or produce unphysical results when bonds are stretched beyond their equilibrium length; bonded structures cannot dissociate.

- Root Cause: Use of a simple harmonic potential, which is not designed to model bond dissociation and unrealistically increases energy as the bond is stretched. [8] [9]

- Solution:

- Replace with a Morse Potential: Substitute the harmonic bond term for relevant bonds with a Morse potential. [8]

- Parameter Assignment: Obtain the dissociation energy ((De)) from experimental or quantum mechanical data. Derive the width parameter ((\alpha)) from the original harmonic force constant ((k)) using (\alpha = \sqrt{k/(2De)}). The equilibrium distance ((r_e)) remains unchanged. [1] [8]

- Validation: Perform a single-bond stretch simulation and verify that the potential energy plateaus at the correct dissociation energy. [8]

Problem: Unphysical Energy or Vibrational Frequency in GROMOS Simulations

- Symptoms: Calculated vibrational frequencies deviate from expected values; average bond energy does not conform to the equipartition theorem.

- Root Cause: Use of the Fourth-power bond potential ((Vb(r{ij}) = \frac{1}{4}k^b{ij}(r{ij}^2-b_{ij}^2)^2)), which is anharmonic and does not yield an average energy of (\frac{1}{2}kT) per bond. [1]

- Solution:

- Understanding: Recognize that this is a known property of the GROMOS-96 force field, traded for computational speed.

- Parameter Awareness: Be aware that the force constants ((k^b)) in this form are related to harmonic force constants ((k^{b,\mathrm{harm}})) by (2 k^b b_{ij}^2 = k^{b,\mathrm{harm}}). Use parameters consistently within the force field's framework. [1]

- Alternative: If accurate harmonic behavior is critical, consider using a force field that implements a true harmonic bond potential.

Problem: Energy Drift or Simulation Crash During Extreme Stretching

- Symptoms: Simulation becomes unstable, or energy conservation fails when bonds are stretched far from equilibrium, particularly with anharmonic potentials.

- Root Cause: Potentials like the cubic or Morse potential can become infinitely attractive or repulsive in certain limits, and the numerical integrator may fail to handle these sharp energy changes. [1]

- Solution:

- Reduce Timestep: Decrease the integration timestep (e.g., to 1 fs) to improve stability for anharmonic bonds. [1]

- Check Potential Validity: For the cubic potential, be aware it is asymmetric and can lead to infinitely low energies upon overstretching. Monitor bond lengths to ensure they stay within a physically reasonable range. [1]

- Use a Restrained Potential: For specific applications like coarse-grained polymer simulations, a FENE (Finitely Extensible Nonlinear Elastic) potential can be used, which has a defined maximum extension. [1]

Comparison of Bond Stretching Potentials

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the three common bond stretching potentials.

| Feature | Harmonic Potential | Fourth-Power Potential | Morse Potential |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mathematical Form [1] | (\frac{1}{2}k{ij}^b(r{ij}-b_{ij})^2) | (\frac{1}{4}k{ij}^b(r{ij}^2-b_{ij}^2)^2) | (D{ij} [1 - e^{-\beta{ij}(r{ij}-b{ij})}]^2) |

| Dissociation Behavior | Does not dissociate (energy goes to ∞) | Does not dissociate (energy goes to ∞) | Correctly dissociates to (D_{ij}) [1] [8] |

| Anharmonicity | No | Yes | Yes [1] [9] |

| Computational Cost | Low | Low (avoids square root) [1] | Higher |

| Primary Application | Standard MD near equilibrium | GROMOS family force fields [1] | Reactive MD, bond breaking [8] |

| Key Parameters | (k{ij}^b) (force constant), (b{ij}) (equilibrium length) | (k{ij}^b) (force constant), (b{ij}) (equilibrium length) | (D{ij}) (dissociation energy), (\beta{ij}) (width), (b_{ij}) (equilibrium length) [1] |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a Reactive Bond Potential

This protocol details the methodology for converting a non-reactive force field to a reactive one by replacing harmonic bonds with Morse potentials, as described in the IFF-R approach. [8]

Objective: To enable bond dissociation in molecular dynamics simulations while maintaining the accuracy of the original force field for equilibrium properties.

Workflow: The following diagram illustrates the conversion and parameterization process.

Materials and Reagents:

- Software: A molecular dynamics package with support for Morse potentials (e.g., GROMACS, LAMMPS). [1]

- Initial System: A topology and coordinate files for the system of interest parameterized with a standard non-reactive force field (e.g., IFF, CHARMM, AMBER). [8]

- Reference Data: High-level quantum mechanical (e.g., CCSD(T), MP2) or experimental data for bond dissociation energies. [8]

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Bond Selection: Identify the covalent bonds in your system that are to be made reactive. This can be applied to all bonds or a subset, such as those with the lowest dissociation energies. [8]

- Parameterization:

- The equilibrium bond length ((re) or (b{ij})) is taken directly from the original harmonic force field. [8]

- The dissociation energy ((De) or (D{ij})) is obtained from experimental data or high-level quantum mechanical calculations for the specific bond type. [8]

- The width parameter ((\alpha) or (\beta{ij})) is calculated to match the harmonic potential near the minimum: (\alpha{ij} = \sqrt{k^{b,\mathrm{harm}}{ij} / (2 D{ij})). This parameter can be further refined to match experimental vibrational frequencies from IR or Raman spectroscopy. [1] [8]

- Validation: Before running production simulations, validate the parameterized Morse potential by comparing its energy curve for a diatomic molecule to the reference quantum mechanical data. Ensure that bulk properties (density, elastic moduli) of the unreacted system are maintained. [8]

- Production Simulation: Run the molecular dynamics simulation. The Morse potential will now allow bonds to break when the strain energy exceeds the dissociation energy. For bond formation, a complementary method like the REACTER protocol may be required. [8]

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Morse Potential | An anharmonic potential that realistically describes bond dissociation; the key function for enabling reactivity in classical MD. [1] [8] |

| Quantum Mechanical (QM) Data | Provides high-accuracy reference data, such as bond dissociation energies and reaction paths, for parametrizing and validating reactive force fields. [8] |

| Reactive Force Field (ReaxFF) | A complex bond-order potential used as a state-of-the-art benchmark for comparing the accuracy and performance of simpler reactive methods. [8] [11] |

| Harmonic Potential | The standard, computationally efficient potential for simulating molecular systems where bond breaking is not required. [1] [7] |

| GROMACS MD Engine | A widely used molecular dynamics simulation package that includes built-in support for harmonic, fourth-power, and Morse bond potentials. [1] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is meant by "self-interaction error" in the context of a molecular mechanics force field? In Molecular Mechanics (MM) force fields, the treatment of electrostatic interactions can lead to inaccuracies. The standard "additive" model uses fixed point charges on atoms and calculates electrostatics simply by summing Coulomb interactions between these charges [12]. This method does not account for the fact that an atom's own electron distribution can polarize in response to its environment. More advanced, polarizable force fields aim to address this limitation, but they introduce greater complexity in parametrization [12]. In the context of a classical force field, this simplification is a primary source of self-interaction error.

Q2: How can improper parameterization of a force field impact my simulation results? The accuracy of a molecular dynamics simulation is fundamentally limited by the reliability of its potential functions [13]. If the parameters for bonds, angles, or non-bonded interactions are fitted against an insufficient or incorrect set of target data (e.g., quantum mechanical calculations or experimental properties), the simulation will produce unreliable results [12]. A critical example is that potential functions fitted solely to solid-state properties may fail entirely to predict correct solid-liquid phase behavior or melting points [13]. This improper parameterization can lead to incorrect predictions of material densities, mechanical properties, and dynamic behavior.

Q3: Why does my simulation crash with unphysically large atomic movements? This is a classic symptom of numerical instability. It can be caused by several factors related to the force field and integration scheme. One common cause is the use of an overly large timestep when numerically integrating Newton's equations of motion [14]. The timestep must be small enough to accurately capture the system's fastest motions (e.g., bond vibrations). Furthermore, when modifying force fields to allow for bond dissociation (e.g., replacing harmonic bonds with Morse potentials), unconstrained cross-term interactions can generate catastrophically large forces if not properly reformulated, causing the simulation to crash [15].

Q4: My simulation is stable but the predicted density of my material is wrong. What is the most likely cause? Incorrect mass density is often a direct result of improper force field parameterization [15] [8]. The nonbonded interactions—specifically the Lennard-Jones parameters that define van der Waals forces and the partial atomic charges that define electrostatic interactions—are critical for achieving correct condensed-phase properties like density. Highly accurate force fields like INTERFACE (IFF) are parameterized to reproduce experimental densities with deviations typically less than 0.5%, whereas a poorly parameterized force field can show errors of 3% or more [8].

Q5: Can I simulate bond breaking and formation with a standard harmonic force field? No. Conventional harmonic force fields used in biomolecular simulation have a fixed bonding topology, meaning bonds cannot break or form during the simulation [14] [8]. The harmonic potential used for bond stretching would generate unphysically large restorative forces as atoms are pulled apart. To simulate reactivity, specialized reactive force fields are required, such as those using Morse bond potentials (like IFF-R) or bond-order concepts (like ReaxFF) [15] [8].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide: Diagnosing and Resolving Numerical Instability

Symptoms: Simulation crashes with errors related to "constraint failure" or atoms experiencing "unphysically large forces."

Diagnosis and Resolution Workflow:

Detailed Steps:

- Reduce Integration Timestep: The timestep must be short enough to resolve the fastest molecular vibrations. For systems with explicit bonds to hydrogen, a timestep of 1-2 femtoseconds (fs) is often necessary. To enable a larger timestep (e.g., 2 fs), high-frequency bonds can be constrained using algorithms like LINCS or SHAKE [14].

- Inspect Force Field Formulation: When using reactive simulations with Morse bond potentials, standard harmonic cross-terms (e.g., bond-bond or bond-angle couplings) can generate unphysically large forces upon bond stretching. Reformulating these cross-terms to an exponential form (as in ClassII-xe force fields) is necessary for stability [15].

- Verify System Topology: Incorrectly assigned protonation states, missing atoms, or steric clashes in the initial structure can cause instability. Use automated preparation tools to ensure proper protonation and topology generation [16].

Guide: Validating Force Field Parameterization

Symptoms: Simulation is stable but outputs are physically unrealistic (e.g., incorrect density, mechanical properties, or phase behavior).

Diagnosis and Resolution Workflow:

Detailed Steps:

- Select an Appropriate Force Field: The choice of force field is critical. For example, the Embedded Atom Method (EAM) is suitable for metals, while the Tersoff potential is designed for covalent materials like silicon [13]. Using a protein force field for a polymer system, or vice versa, will yield poor results.

- Validate Against Known Properties: Before trusting a simulation for unknown properties, always calibrate it against known experimental or high-level quantum mechanical data. Key benchmarks include mass density, vaporization energy, and elastic moduli [8].

- Scrutinize the Parameterization Source: A force field's accuracy is determined by the target data used to fit its parameters [12]. For instance, a potential function fitted only to solid-state data may fail to predict correct melting points or solid-liquid interface properties. Ensure that the force field was parameterized using data relevant to your simulation conditions (e.g., liquid thermodynamic data for solvation studies) [13].

Key Experimental Protocols and Data

Protocol: Converting a Harmonic Force Field to a Reactive One

This protocol outlines the methodology for introducing bond-breaking capability into a standard harmonic force field, as demonstrated by the creation of IFF-R [8].

- Identify Target Bonds: Determine which covalent bonds in the system will be made reactive.

- Replace Harmonic Bond Potential: Substitute the harmonic bond potential term for the identified bonds with a Morse potential. The Morse potential energy is given by ( E{Morse} = D{ij} [1 - e^{-α{ij}(r-r{0,ij})}]^2 ), where ( D{ij} ) is the bond dissociation energy, ( α{ij} ) defines the width of the potential well, and ( r_{0,ij} ) is the equilibrium bond length.

- Parameter Acquisition:

- Set ( r{0,ij} ) to the equilibrium bond length from the original harmonic potential.

- Obtain the dissociation energy ( D{ij} ) from experimental data or high-level quantum mechanical calculations (e.g., CCSD(T) or MP2).

- Fit ( α_{ij} ) to match the harmonic potential near the equilibrium distance or to reproduce experimental vibrational frequencies.

- Handle Cross-Terms (Critical for Class II Force Fields): If the original force field contains cross-terms (e.g., bond-bond or bond-angle couplings), they must be reformulated into an exponential functional form (ClassII-xe) to prevent unphysical energy contributions when bonds are stretched [15].

- Validation: Verify that the new reactive force field (e.g., IFF-R) reproduces the structural and energetic properties of the non-reactive parent force field under equilibrium conditions.

Quantitative Data on Force Field Performance

Table 1: Density Predictions of PCFF-xe Force Field vs. Experiment [15]

| Material System | Predicted Density (g/cm³) | Experimental Density (g/cm³) | Deviation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polybenzoxazine | 1.20 | 1.19 | < 1% |

| Epoxy Resin | 1.25 | 1.22 | ~2.5% |

| PEEK | 1.30 | 1.32 | ~1.5% |

| Cellulose Iβ | 1.69 | 1.63 - 1.64 | ~3% |

| Glassy Carbon | 1.45 | 1.55 | ~7% |

Table 2: Comparison of Reactive Simulation Methods [8]

| Method | Functional Form | Computational Speed (Relative) | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| IFF-R | Morse potential | ~30x | High accuracy of parent force field maintained; enables bond breaking. |

| ReaxFF | Bond-order concept | 1x (Baseline) | Models complex reaction paths; high parametrization complexity. |

| Standard Harmonic FF (e.g., CHARMM, AMBER) | Harmonic potential | ~30x | Fixed bonding topology; no bond breaking; high efficiency. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software and Force Fields for Molecular Dynamics

| Item | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| LAMMPS | A highly versatile and scalable MD simulator with robust parallel computing capabilities. | The software of choice for simulating large-scale metallic, alloy, and complex material systems [13]. |

| GROMACS | A high-performance MD package optimized for biomolecular systems like proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids. | Ideal for simulating biomolecules in solution; also handles simpler material systems [13]. |

| CHARMM/AMBER/OPLS-AA | Class I biomolecular force fields using harmonic bonds for bonds/angles and fixed partial charges. | The standard for simulating proteins, DNA, and ligands in drug discovery (CSBDD) [12] [8]. |

| PCFF/COMPASS | Class II force fields that include anharmonic terms and cross-terms for more accurate energy surfaces. | Provide improved accuracy for condensed-phase polymers and organic materials [15]. |

| IFF & IFF-R | A highly accurate, interpretable force field for diverse chemistry; IFF-R adds reactivity via Morse bonds. | Simulating interfaces and hybrid materials; IFF-R enables bond-breaking studies with high speed and accuracy [8]. |

| StreaMD | A Python-based automation toolkit for high-throughput MD simulations. | Streamlines preparation, execution, and analysis of MD simulations for multiple protein-ligand complexes [16]. |

Identifying Stretched-Bond Artifacts in Biomolecular Simulations

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What does it mean if my visualization tool (like VMD) shows a missing bond in my DNA/Protein during a simulation? In most cases, this is a visualization artifact, not an actual error in your simulation dynamics. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations using standard molecular mechanics force fields cannot break or form chemical bonds as the topology remains fixed [14]. Visualization software often guesses bond connectivity based on inter-atomic distances. If an atom pair moves slightly beyond the tool's built-in distance threshold, the bond may not be drawn, even though it is perfectly defined in your topology file [17].

My initial structure has some overlapping atoms or high-energy strains. Will this cause artifacts? Yes. Bad contacts and high-energy initial configurations can lead to extreme forces in the first steps of a simulation. This can cause atoms to move rapidly apart, creating large, unrealistic bond stretches that may be misinterpreted as broken bonds. A proper energy minimization protocol is essential to relax these strains before beginning production dynamics [18].

How can I be sure if a bond is truly broken or if it's just a visualization glitch?

The definitive source of truth is your system's topology file. The [ bonds ] section of this file contains the explicit list of all bonds that the simulation engine (e.g., GROMACS, NAMD) will calculate forces for. If a bond is defined there, it exists in the simulation, regardless of what the visualization shows [17].

Troubleshooting Guide: Apparent "Broken Bonds"

Follow this logical workflow to diagnose and resolve issues with stretched or missing bonds.

Diagnostic Workflow

The following diagram outlines the step-by-step diagnostic process:

Resolution Protocols

Protocol 1: Correcting Visualization Artifacts

- Identify the Problem: Note which specific bond is not being drawn in your visualization tool (e.g., VMD).

- Consult the Topology: Open your system's topology file (e.g.,

.topin GROMACS) and locate the[ bonds ]section. Verify that the two atoms in question are listed as a bonded pair [17]. - Visualize a Corrected Structure: To ensure the visualization tool correctly identifies the bond, load a stable frame from your trajectory—such as the output from your energy minimization step—alongside the trajectory. The minimized structure will have bond lengths closer to their ideal values, allowing the visualization tool to correctly draw the bond [17].

Protocol 2: Rectifying Topology Errors

- Identify the Missing Bond: Confirm that the expected chemical bond is not present in the

[ bonds ]section of your topology. - Re-generate the Topology: Use your preferred molecular dynamics setup tool (e.g., CHARMM-GUI [18]) to re-generate the system topology, ensuring all required molecules and their chemical structures are correctly specified during the setup process.

- Manual Topology Editing (Advanced): If necessary, manually add the missing bond entry to the topology file in the correct format for your simulation software. This should only be done with a thorough understanding of the file format and force field parameters.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

The table below lists software and files critical for preparing, running, and analyzing simulations to prevent and diagnose bond artifacts.

| Item Name | Function & Relevance to Bond Integrity |

|---|---|

| CHARMM-GUI [18] | A web-based platform that generates simulation inputs, including topologies with correct bonded terms. Using it ensures proper initial setup. |

| GROMACS [17] | A widely used molecular dynamics simulation package. It uses the topology to calculate bonded forces and will not break bonds. |

| Visual Molecular Dynamics (VMD) [17] | A visualization program. It guesses bonds based on distance, which can lead to artifacts if a structure is not properly minimized. |

| Topology File [17] | The definitive record of all bonds, angles, and dihedrals in the system. It is the ultimate authority for checking if a bond exists in the simulation. |

| Energy-Minimized Structure [17] | The output of an energy minimization run. Loading this structure in VMD helps eliminate visualization artifacts caused by high-energy initial configurations. |

Quantitative Data on Bonded Interactions in Force Fields

The following table summarizes the key energy terms governing bond stretching in biomolecular force fields, which prevent bonds from breaking unrealistically [19].

| Force Field Class | Bond Potential Energy Function | Key Characteristics & Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Class I (AMBER, CHARMM, GROMOS) | ( V{Bond} = kb(r{ij} - r0)^2 ) | Simple harmonic potential. ( kb ) is the bond force constant, and ( r0 ) is the equilibrium bond length. |

| Class II (MMFF94, UFF) | ( V{Bond} = kb(r{ij} - r0)^2 + \text{anharmonic terms} ) | Adds cubic/quartic terms for a more accurate potential energy surface at the cost of more parameters. |

| Class III (AMOEBA, DRUDE) | Complex functions incorporating polarization | Explicitly includes effects like polarization, making them more accurate but computationally expensive. |

Advanced Solutions: Reactive Force Fields and Machine Learning Potentials

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving Stability Issues During Bond Dissociation

Problem: Simulation crashes or produces unphysical results when bonds break during molecular dynamics runs using Morse potentials.

Solutions:

- Symptom:

lost_atomsERROR ormissing _bondsERROR.- Cause: High local velocities and forces generated instantly when a bond breaks, creating "hot spots."

- Fix: Implement a local velocity rescaling protocol. Create a dynamic group of atoms near the newly broken bond and apply a thermostat (e.g.,

fix temp/rescalein LAMMPS) exclusively to this group to dissipate excess kinetic energy [20].

- Symptom:

fix bond/break needs ghost atoms from further awayERROR.- Cause: The communication cutoff in the MD engine is too short to handle the increased interatomic distances post-breakage.

- Fix: Manually increase the communication cutoff distance. For instance, if the default was 12 Å, increasing it to 16 Å may resolve the issue [20].

- Symptom: Instability immediately following bond breakage.

- Cause: Strong forces from angle or dihedral interactions connected to the broken bond vanish instantly, causing a shock.

- Fix: Before production runs, conduct a geometry test. Immobilize part of a molecule and use a

fix movecommand to deliberately break a bond while monitoring forces for each interaction style (bonds, angles, dihedrals) to identify problematic terms [20].

Guide 2: Addressing Failure in Bond Formation Simulations

Problem: The simulation fails to correctly form new bonds during a reactive simulation.

Solutions:

- Symptom: Desired bond formation does not occur.

- Cause: Incorrect or missing parameters for the new bond type in the force field file.

- Fix: Verify that all Morse parameters (

D_e,α,r_e) for the new bond type are correctly defined in the simulation input. Cross-reference with quantum mechanical (QM) calculations or experimental data [8].

- Symptom: Simulation becomes unstable during bond formation attempts.

- Cause: The use of incompatible simulation fixes for reactive processes.

- Fix: For complex bond-forming reactions in LAMMPS, consider switching from

fix bond/breakto the more sophisticatedfix bond/react, which is designed to handle the creation of new topological elements [20].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental advantage of replacing a harmonic bond potential with a Morse potential?

The primary advantage is the physically correct description of bond dissociation. A harmonic potential approximates the bond as a spring that requires ever-increasing energy to stretch, which is unphysical. In contrast, the Morse potential accounts for bond breaking by featuring a finite dissociation energy ((D_e)), where the potential energy plateaus as the bond is stretched, approaching a constant value. This allows atoms to separate completely, enabling the simulation of material failure and chemical reactions [10] [8] [9].

Q2: How do I obtain the three parameters ((De), (\alpha), (re)) for a Morse potential?

The parameters are derived as follows [8]:

- Equilibrium bond length ((r_e)): This is the same as the equilibrium distance in the original harmonic potential.

- Dissociation energy ((D_e)): This is the bond energy, obtained from experimental data or high-level quantum mechanical (QM) calculations (e.g., CCSD(T) or MP2).

- Width parameter ((\alpha)): This parameter controls the width of the potential well. It is typically fitted so that the curvature of the Morse potential near the minimum matches the force constant ((ke)) of the original harmonic potential, ensuring similar vibrational frequencies at equilibrium. The approximate relation is (a = \sqrt{ke / 2D_e}) [10]. The parameter can be further refined to match experimental vibrational wavenumbers from spectroscopy [8].

Q3: My simulation uses angle and dihedral terms. Will they cause issues when a bond breaks?

Yes, this is a critical consideration. The Morse potential only describes the bond stretching. When a bond breaks, the angle and dihedral interactions associated with that bond can instantly vanish, potentially generating large, unphysical forces and causing instability [20]. Most modern reactive force field implementations, like IFF-R, automatically handle the removal of these associated interactions when a bond is broken to maintain energy conservation and stability [8].

Q4: How does the performance of a Morse potential-based reactive force field compare to other reactive methods?

Methods like IFF-R, which use Morse potentials, are reported to be about 30 times faster than bond-order potentials like ReaxFF [8]. This is because Morse potentials retain a simple pairwise functional form with only three interpretable parameters per bond type, unlike the complex, multi-term bond-order calculations in ReaxFF that depend on the local chemical environment [8].

Q5: Can I mix harmonic and Morse potentials in the same simulation?

Yes. The Reactive INTERFACE Force Field (IFF-R) methodology allows for the selective replacement of harmonic bond potentials with Morse potentials. You can choose to replace all bonds or only a specific subset, such as those with the lowest dissociation energies that are known to break first under stress [8].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparison of Bond Potentials in Molecular Dynamics

| Feature | Harmonic Potential | Morse Potential | Reactive Bond-Order (ReaxFF) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Functional Form | (V(r) = \frac{1}{2}k(r-r_e)^2) [9] | (V(r) = De (1 - e^{-a(r-re)})^2) [10] | Complex, based on environment-dependent bond order [8] |

| Bond Breaking | No (infinite energy required) | Yes (finite dissociation energy (D_e)) [10] | Yes |

| Anharmonicity | No | Yes [9] | Yes |

| Speed | Fastest | ~30x faster than ReaxFF [8] | Slowest |

| Parameters per Bond | (ke), (re) | (De), (a), (re) [10] | Many, including global element parameters |

| Primary Use Case | Equilibrium dynamics, structural biology | Bond dissociation, material failure [8] | Complex, concerted chemical reactions [8] |

Table 2: Typical Morse Parameter Ranges and Determination Methods

| Parameter | Symbol | Typical Range | Determination Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dissociation Energy | (D_e) | Varies by bond (e.g., ~100-500 kcal/mol for C-C) | Experiment (thermochemistry) or QM calculation (CCSD(T), MP2) [8] |

| Width/Steepness | (a) | ~2.1 ± 0.3 Å⁻¹ [8] | Fit to harmonic force constant: (a = \sqrt{ke / 2De}) [10] or IR/Raman frequencies [8] |

| Equilibrium Bond Length | (r_e) | ~1.0-1.5 Å for C-C | From crystallography or the original harmonic potential [8] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Parameterization of a Morse Potential from Quantum Mechanics

Objective: To derive accurate Morse parameters ((De), (a), (re)) for a specific bond type (e.g., C-C single bond) using high-level quantum mechanical calculations.

- System Selection: Choose a small, representative molecule containing the bond of interest (e.g., ethane for a C-C bond).

- Energy Scan Calculation:

- Perform a series of single-point energy calculations using a high-level QM method (e.g., CCSD(T) or MP2) with a large basis set.

- In each calculation, systematically vary the internuclear distance ((r)) of the target bond while relaxing all other degrees of freedom.

- Potential Energy Curve: Plot the calculated electronic energy against the bond distance (r) to generate a potential energy curve.

- Parameter Extraction:

- (re): Identify the bond distance at the energy minimum of the curve.

- (De): Calculate the difference between the energy at the minimum and the energy at a very large separation (the asymptotic limit).

- (a): Fit the calculated data points to the Morse function (V(r) = De (1 - e^{-a(r-re)})^2) to obtain the value of (a) that best reproduces the QM curve [8].

Protocol 2: Simulating Tensile Failure of a Polymer Fiber

Objective: To simulate the stress-strain behavior and ultimate failure of a polymer fiber using a Morse potential-based force field.

- System Preparation: Construct an atomistic model of an amorphous or semi-crystalline polymer fiber (e.g., polyethylene or a polyacrylonitrile chain) in a periodic simulation box.

- Equilibration: Energy-minimize the system and run an NPT simulation to equilibrate the density at the target temperature and pressure.

- Uniaxial Deformation:

- Switch the ensemble to NVT.

- Apply a constant strain rate by progressively scaling the box length in one dimension (e.g., the z-axis) while allowing the lateral dimensions to adjust.

- For all covalent bonds in the polymer backbone, use the Morse potential with parameters derived from Protocol 1 or a validated database.

- Data Collection:

- Monitor the stress tensor (specifically the stress in the deformation direction) throughout the simulation.

- Record the strain, defined as ((Lt - L0)/L0), where (L0) is the initial box length and (L_t) is the length at time (t).

- Track the number of bonds that break during the deformation process.

- Analysis: Plot the stress versus strain curve. The point where the stress drops catastrophically corresponds to material failure, and the maximum stress is the ultimate tensile strength [8].

Mandatory Visualization

Workflow for Morse Potential Implementation

Relationship Between Morse Parameters and Potential Energy Surface

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools and Parameters for Reactive Simulations

| Item Name | Function / Role in Simulation | Technical Specifications / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Morse Potential Function | Describes bond energy as a function of distance, enabling bond dissociation. | (V(r) = De (1 - e^{-a(r-re)})^2) [10]. The key reactive energy term. |

| Reactive Force Field (IFF-R) | A specific implementation that replaces harmonic bonds with Morse potentials. | Compatible with CHARMM, AMBER, PCFF forms. ~30x faster than ReaxFF [8]. |

| Quantum Mechanics Software | Used to calculate accurate bond dissociation energies ((D_e)) and scan potential energy surfaces for parameterization. | Examples: Gaussian, ORCA, Q-Chem. Methods: CCSD(T), MP2 for high accuracy [8]. |

| MD Simulation Engine | Software to perform the molecular dynamics calculations. | Examples: LAMMPS, GROMACS, NAMD. Must support user-defined potentials like Morse. |

| Fix Bond/Break (LAMMPS) | A command in LAMMPS to permanently break a bond once the interatomic distance exceeds a defined cutoff. | Used to formally break the bond after the Morse potential has plateaued, preventing spurious reformation [20]. |

| Local Thermostat | A method to rescale velocities of atoms locally after a bond breakage event to remove excess kinetic energy and prevent "hot spots." | Can be implemented via dynamic atom grouping. Critical for maintaining simulation stability [20]. |

Machine Learning Potentials for Accurate Bond Stretching Dynamics

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Errors and Solutions

| Error Category | Specific Error/Symptom | Probable Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geometry Optimization | Discontinuities in energy derivatives/forces during optimization; convergence failure. [21] | Bond order cutoff value causing sudden inclusion/exclusion of valence/torsion angles in energy calculation. [21] | 1. Decrease Engine ReaxFF%BondOrderCutoff. [21]2. Use 2013 torsion angles via Engine ReaxFF%Torsions. [21]3. Enable bond order tapering: Engine ReaxFF%TaperBO. [21] |

| Training & Data | Poor model performance on transition states or stretched bond configurations. | 1. Insufficient quantum chemistry data for stretched bonds in training set. [22]2. Self-interaction error (SIE) in underlying DFT training data causing delocalization error. [23] | 1. Actively sample configurations near transition states and along reaction paths. [22]2. Use higher-fidelity quantum methods (e.g., CCSD(T)) or SIE-corrected DFT for training data in critical regions. [24] [23] |

| Model Performance | Model is accurate but too slow for large-scale Molecular Dynamics (MD). | Use of computationally expensive equivariant models based on high-order tensor operations. [25] | Switch to efficient equivariant models (e.g., E2GNN, PaiNN) that use scalar-vector dual representations instead of higher-order tensors. [25] |

| Software & Parameters | "Invalid order for directive" error in topology file (e.g., GROMACS). [26] | Incorrect order of directives (e.g., [ defaults ], [ atomtypes ]) within molecular topology files. [26] |

Ensure force field is fully defined before [ moleculetype ] directives. The [ defaults ] section must be the first directive. [26] |

| Software & Parameters | "Atom index in position_restraints out of bounds" (e.g., GROMACS). [26] | Position restraint files included for multiple molecules are placed out of order in the master topology file. [26] | Place the #include statement for each molecule's position restraint file immediately after the #include for that molecule's topology file. [26] |

FAQ: Fundamental Questions

Q1: What is the key advantage of MLIPs over classical force fields for simulating bond stretching and reactions?

Classical force fields use fixed mathematical forms that cannot describe bond breaking or formation, making them unsuitable for chemical reactions. Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) learn the potential energy surface directly from quantum mechanical data, allowing them to accurately model the entire bond stretching process, including transition states where bonds are partially broken. [24] [27] They achieve a unique balance, offering near-quantum accuracy at a fraction of the computational cost, bridging the gap between small-scale quantum models and realistic device-scale simulations. [27]

Q2: I've heard MLIPs are slow. Is this still true, and how do they compare to other methods?

The field is evolving rapidly. While early MLIPs were slower than highly optimized classical force fields, their primary comparison is with expensive ab initio Molecular Dynamics (AIMD). MLIPs are significantly faster than AIMD, enabling simulations that are otherwise impossible. [24] Newer, more efficient architectures like E2GNN are closing the speed gap while maintaining high accuracy, making large-scale, long-time simulations feasible. [25] The trade-off between accuracy and computational cost is a key area of development.

Q3: My MLIP model works well for equilibrium structures but fails on my reaction barrier. What could be wrong?

This is a common issue often traced to the training data. If the training set lacks sufficient configurations with stretched bonds or transition-state geometries, the model cannot learn the correct physics for those regions. [22] Furthermore, if the underlying quantum data used for training suffers from self-interaction error (a common problem in standard Density Functional Theory), it can artificially lower the energy of stretched-bond configurations, leading to underestimated reaction barriers. [23] The solution is to improve the training set with targeted sampling of these regions and use higher-quality quantum data.

Q4: What does "equivariance" mean in the context of MLIPs, and why is it important for bond dynamics?

Equivariance is a mathematical property ensuring that the model's predictions for energy and forces rotate correctly with the molecule itself. If you rotate the entire molecular system, the predicted forces should rotate accordingly. This geometric integrity is crucial for correctly modeling bond stretching dynamics and energy conservation during MD simulations, leading to more robust and physically realistic simulations. [25] Models that are not equivariant can introduce artifacts and errors.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing the Weighted Active Space Protocol (WASP) for Multireference Systems

Objective: Accurately simulate bond stretching dynamics in transition metal catalysts, where electronic complexity (multireference character) challenges standard MLIPs. [22]

Methodology:

- Initial Data Generation: Use a multireference quantum chemistry method (e.g., MC-PDFT) to calculate energies and forces for a diverse set of molecular geometries, including those with stretched bonds relevant to the catalysis. [22]

- Wavefunction Consistency with WASP: For new geometries encountered during MD, generate a consistent wavefunction as a weighted combination of wavefunctions from the pre-sampled structures. The weighting is based on geometric similarity, ensuring a smooth and unique potential energy surface. [22]

- MLIP Training: Train a machine-learned interatomic potential (MLIP) on this consistently labeled dataset of geometries and their corresponding MC-PDFT energies/forces. [22]

- Molecular Dynamics Simulation: Run the final, accurate MD simulation using the trained MLIP to explore catalytic dynamics at realistic conditions. [22]

The following diagram illustrates the WASP workflow for generating consistent training data and performing dynamics simulations.

Key Materials:

- Software: WASP codebase (publicly available on GitHub/GagliardiGroup) [22], quantum chemistry package capable of MC-PDFT.

- Computing Resources: High-performance computing cluster.

Protocol 2: Employing an Efficient Equivariant Graph Neural Network (E2GNN)

Objective: Perform accurate and efficient MD simulations across phases (solid, liquid, gas) with correct geometric symmetries and bond dynamics. [25]

Methodology:

- Data Preparation: Assemble a dataset of diverse atomic structures (molecules, crystals) with corresponding ab initio energies and forces. [25]

- Model Setup: Initialize the E2GNN model. Each atom (node) is represented by a dual representation: a scalar feature (invariant, e.g., atomic number embedding) and a vector feature (equivariant, initialized to zero). [25]

- Model Training: Train the network through a series of interaction layers that perform local message passing and global message aggregation, updating both scalar and vector features in a symmetry-preserving (E(3)-equivariant) manner. [25]

- Simulation and Validation: Use the trained E2GNN force field to run MD simulations. Validate the results by comparing properties (e.g., radial distribution functions, diffusion coefficients) to those from ab initio MD benchmarks. [25]

The following diagram illustrates the E2GNN model's internal workflow for processing a molecular structure.

Key Materials:

- Software: E2GNN implementation (code often published with the research), deep learning framework (e.g., PyTorch).

- Data: Diverse dataset of structures and ab initio labels.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item Name | Type | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| WASP (Weighted Active Space Protocol) [22] | Software/Method | Enables consistent MLIP training for complex, multireference systems (e.g., transition metal catalysts) by solving wavefunction labeling problems. |

| E2GNN (Efficient Equivariant GNN) [25] | ML Model Architecture | Provides accurate and efficient force fields by using a scalar-vector dual representation to maintain geometric equivariance without high computational cost. |

| ReaxFF [11] [21] | Reactive Force Field | A classical reactive potential; serves as a baseline and is useful for systems where MLIP data is scarce, though requires careful parameterization. |

| Perdew-Zunger SIC (PZSIC) & LSIC [23] | Quantum Chemistry Method | Methods to reduce self-interaction error in DFT, generating higher-quality training data for MLIPs, especially for stretched bonds and barrier heights. |

| MC-PDFT [22] | Quantum Chemistry Method | A multiconfiguration pair-density functional theory that provides accurate data for training MLIPs on systems where single-reference DFT fails. |

Hybrid MD-ML Frameworks for Complex Systems

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What are the primary advantages of combining Molecular Dynamics (MD) with Machine Learning (ML) for complex systems? Hybrid MD-ML frameworks offer several key benefits. They improve computational efficiency by using ML surrogates to replace costly force field calculations, achieving speedups of several orders of magnitude [28]. They enhance accuracy and generalization by incorporating physical laws as constraints into ML models, which guides them toward physically plausible predictions, even for chemistries outside their immediate training domain [29]. Finally, they enable access to longer timescales; for instance, accelerated MD methods can overcome energy barriers to observe rare events or slow conformational changes that are challenging for standard MD [30].

2. My ML-predicted partial charges lead to unphysical electrostatic energies and system instability. How can I fix this? This is a common issue when the ML model violates global physical constraints. The solution is to implement a physics-informed loss function during model training. This function should enforce critical constraints such as charge neutrality and electronegativity equivalence across the entire simulation domain [28]. Furthermore, employing a probabilistic deep learning model can help. The model predicts a probability distribution for partial charges, and the final candidates are screened against these hard physical constraints, minimizing the chance of polarization catastrophes [28].

3. How can I ensure my coarse-grained (CG) model is thermodynamically consistent and transferable? Relying solely on a bottom-up approach that matches atomistic structural distributions can lead to poor transferability of thermodynamic properties like density. The recommended best practice is to adopt a hybrid optimization framework [31]. This involves using a bottom-up MLCG method (e.g., training a Deep Neural Network) to establish bonded interactions that match atomistic distributions. Concurrently, a top-down MLCG method (e.g., using a Genetic Algorithm) should be used to optimize nonbonded interaction parameters by matching temperature-dependent experimental data, such as density [31].

4. What is the best way to represent a local atomic environment (LAE) for an ML model predicting molecular properties? The Smooth Overlap of Atomic Positions (SOAP) descriptor is a powerful and widely used method for representing LAEs [28]. However, SOAP descriptors can be very high-dimensional. To manage this, apply dimensionality reduction techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA). A few principal components can often capture over 99% of the variance in the dataset, creating a tractable, lower-dimensional input for your ML model that still preserves the distinct clustering of different atomic species [28].

5. How can I model associative bond swapping (e.g., in vitrimers) in a continuous MD framework?

The RevCross three-body potential is a validated method for this purpose. It introduces a repulsive three-body interaction that creates an energy barrier for bond swapping [32]. A key parameter (λ) controls the height of this swap barrier, allowing you to directly tune the bond exchange kinetics to match your material system. This method is implemented in open-source packages like HOOMD-Blue [32].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Issue 1: Poor Convergence and Non-Physical Clustering in Simulations with Dynamic Bonding

- Problem: Your simulation of a dynamically bonding soft material exhibits instability and unphysical clustering of particles.

- Diagnosis: This is often caused by an incorrectly parameterized bonding potential that cannot enforce a one-to-one bonding scheme. For example, when using the RevCross potential, if the parameter

λ < 1, the three-body repulsive term is too weak to prevent multiple simultaneous attractions [32]. - Solution:

- Verify that your bonding potential parameters are within physically realistic bounds.

- For the RevCross potential, ensure

λ ≥ 1. A value ofλ = 1allows spontaneous swapping, whileλ >> 1creates a higher barrier, slowing down exchange kinetics [32]. - Monitor the number of bonds per particle during an initial equilibration phase to confirm the correct bonding behavior.

Issue 2: ML-Accelerated MD Simulation Fails to Conserve Energy

- Problem: An MD simulation using an ML-predicted force field shows significant energy drift, making the results non-physical.

- Diagnosis: The machine-learned force field likely lacks fundamental physical invariances and constraints, such as energy conservation, correct asymptotic behavior, and symmetry invariance [29].

- Solution:

- Architecture Choice: Use ML model architectures that inherently build in physical symmetries, such as SchNet or other graph neural networks that are invariant to translation, rotation, and permutation of atoms [33] [29].

- Training Data: Ensure your training data from QM or high-fidelity MD simulations is diverse and representative of all relevant configurations.

- Physical Constraints: Incorporate physical laws directly into the model's loss function during training to enforce desired properties [29] [28].

Issue 3: Coarse-Grained Model Performs Poorly at Temperatures Not Included in Training

- Problem: Your CG model accurately predicts properties at the parametrization temperature but fails when applied to a different temperature.

- Diagnosis: This is a classic issue of poor transferability, often stemming from a purely bottom-up parametrization that does not capture the correct temperature-dependent thermodynamics [31].

- Solution: Implement the hybrid bottom-up/top-down optimization framework.

- Use a bottom-up approach (e.g., with a DNN) to learn bonded interactions from atomistic distributions.

- Optimize nonbonded interactions with a top-down approach by matching experimental temperature-dependent density.

- Using a DNN as a surrogate model to rapidly predict density during the optimization loop can significantly accelerate this process [31].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Detailed Methodology: Hybrid CG Model Development

The following protocol, adapted from a study on polyether coarse-graining, outlines the steps for creating an efficient and transferable CG model [31].

Data Generation (All-Atom Reference):

- Perform all-atom (AA) MD simulations of the system of interest across a range of temperatures and molecular weights.

- Extract structural distributions (e.g., bonds, angles) and thermodynamic properties (e.g., density) from these trajectories to serve as the reference "ground truth."

Bottom-Up MLCG (Bonded Interactions):

- Representation: Map atomistic configurations to the CG representation.

- Training: Train a Deep Neural Network (DNN) to learn the bonded interactions (bond and angle potentials). The objective is to minimize the difference between the structural distributions of the CG model and the AA reference data.

Top-Down MLCG (Nonbonded Interactions):

- Optimization Setup: Use an optimization algorithm (e.g., Genetic Algorithm) to find the optimal nonbonded interaction parameters.

- Surrogate Model: Train a separate DNN as a surrogate that predicts a system's density based on nonbonded parameters and temperature. This replaces the need for a full MD simulation at every optimization step.

- Objective Function: The optimizer minimizes the difference between the surrogate-predicted density and the experimental temperature-dependent density data.

Validation and Transferability Testing:

- Validate the final CG model by predicting key properties not included in the training, such as the radius of gyration (Rg), diffusion coefficients, or stress relaxation. Assess its performance on different molecular weights and temperatures outside the training set [31].

Quantitative Performance Data

Table 1: Accuracy of ML Surrogate Models in MD

| ML Task | Reference Method | ML Method | Speed-up | Error vs. Reference | Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Partial Charge Prediction [28] | ReaxFF MD charge equilibration | Physics-Informed LSTM | > 100x | < 3% | Corrosion in salt brine |

| Boiling Point Estimation [34] | Experimental data | MD-ML Hybrid (Nearest Neighbours Regression) | Not Specified | ~0.1% (1-2 K) | Aromatic fluids |

| Coarse-Grained Structural Property [31] | United-Atom MD | Hybrid MLCG (DNN + GA) | Not Specified | ({\langle {R}_{{\rm {g}}}^{2}\rangle }^{1/2}): 24.56 Å (CG) vs 25.86 Å (AA) | Poly(tetramethylene oxide) polymer melts |

Table 2: Key Software and Force Fields for Hybrid MD-ML

| Resource | Type | Primary Function in Hybrid MD-ML | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| LAMMPS [30] [32] | MD Software | General-purpose MD simulations; compatible with accelerated methods and the REACTER framework. | High flexibility; supports many particle and continuum styles. |

| HOOMD-Blue [32] | MD Software | GPU-accelerated MD; includes built-in methods for dynamic bonding. | Implements the RevCross three-body potential for associative bond swaps. |

| ANI [33] [29] | ML Potential | Extensible neural network potential with DFT accuracy. | Uses atomic environment vectors (AEVs) as input. |

| SchNet [33] [29] | ML Architecture | Deep learning architecture for predicting molecular properties and potential energy surfaces. | A variant of DTNN that learns molecular representations. |

| RevCross Potential [32] | Interaction Potential | Models associative bond swapping in a continuous MD framework. | Tunable swap kinetics via the λ parameter. |

| REACTER Framework [32] | Simulation Method | Incorporates detailed dynamic bonding mechanisms in MD. | Allows for modeling of complex bond formation/breakage. |

Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 1: Hybrid MD-ML Charge Prediction

Diagram 2: Hybrid CG Model Optimization

Diagram 3: Accelerated MD with Bond-Boost Method

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are a powerful tool for providing mechanistic understanding in drug discovery and development, modeling a system as a set of particles that interact through classical mechanics [35]. However, simulating extreme events like bond fission (breaking) pushes the boundaries of standard simulation protocols and force fields. Inaccuracies can arise from insufficient sampling, force field limitations, and inadequate treatment of high-energy states. This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers overcome the specific challenges associated with simulating bond fission in drug-like molecules, framed within the broader context of molecular dynamics bond stretching errors solutions research.

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

1. FAQ: Why do my simulations show unrealistic bond lengths or premature bond breaking when simulating high-energy states?

- A: This is a common issue often traced to the force field's harmonic bond potential. Standard biomolecular force fields (like AMBER and CHARMM) are parameterized for stable, near-equilibrium structures, not for bond dissociation. The harmonic potential does not accurately represent the energy profile as a bond is stretched to the point of fission.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Validate with Quantum Mechanics (QM): Perform single-point energy calculations on your stretched molecular configurations using a QM method (e.g., DFT). Compare the QM energy profile to the one generated by your force field to quantify the error [35].

- Investigate Enhanced Sampling: If bond fission is a rare event in your system, consider using enhanced sampling techniques to achieve adequate sampling of the transition state without forcing the bond into an unphysical conformation [36].

- Explore Custom Parameters: For specific, critical bonds, develop custom anharmonic bond parameters derived from QM calculations to more accurately model the energy required for fission.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

2. FAQ: My simulations of bond fission are not converging. How can I ensure my results are reproducible?

- A: Convergence is a critical challenge in MD. A single simulation, even a long one, may not fully capture the conformational space and dynamics leading to bond fission.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Run Ensembles of Simulations: As demonstrated in DNA dynamics studies, initiate multiple independent simulations with different initial random velocity seeds [36]. Aggregating results from these ensembles provides a more robust and reproducible conformational sampling.

- Check Collective Variables: Monitor key collective variables, such as the bond length in question and the radius of gyration if the system's overall compactness changes. The decay of the average RMSD over longer time intervals can be used to assess convergence [36].

- Ensure Sufficient Sampling Time: Confirm that your simulation time exceeds the required timescale for the bond fission event. For some systems, convergence of internal dynamics occurs on the microsecond timescale [36].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

3. FAQ: How can I integrate experimental data to improve the reliability of my simulations involving large-scale conformational changes like those after bond fission?

- A: Combining MD simulations with biophysical experimental data is a powerful strategy to refine and validate conformational ensembles, especially for flexible systems.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Utilize Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering (SAXS): SAXS data provides information on the overall shape and size of a molecule in solution. You can calculate SAXS profiles from your simulation trajectories and use a Bayesian/Maximum Entropy (BME) approach to reweight the ensemble to achieve consistency with the experimental data [37].

- Incorporate Small-Angle Neutron Scattering (SANS): With contrast variation, SANS can highlight individual domains within a multi-domain protein. Refining your simulation ensembles against SAXS data often also improves agreement with SANS, providing additional validation [37].

- Refine the Force Field: If initial simulations lead to poor agreement with experiments (e.g., overly compact structures), systematic adjustment of force field parameters, such as the strength of protein-water interactions, can substantially improve the fit [37].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

Quantitative Data and Error Analysis

The following tables summarize key quantitative aspects of managing simulation integrity, a crucial consideration when modeling unstable states like bond fission.

Table 1: Key Considerations for Simulation Convergence

| Metric | Description | Target for Convergence |

|---|---|---|

| RMSD Decay | The decay of the average Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) over increasing time intervals. | Values should plateau as simulation time increases, indicating sampling of a stable conformational ensemble [36]. |

| Kullback-Leibler Divergence | A measure of the difference between the probability distributions of dynamics from different simulation segments. | Low divergence values between halves of a simulation or between ensemble members suggest convergent dynamics [36]. |

| Block Analysis | A method for estimating the statistical error of a calculated property by analyzing its variance over consecutive blocks of simulation time. | Error estimates should stabilize with increasing block size, indicating the data is statistically well-behaved [37]. |

Table 2: Common Force Field Types and Their Suitability for Bond Fission Studies

| Force Field Type | Resolution | Common Examples | Suitability for Bond Fission | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All-Atom | Individual atoms | AMBER (ff99SB, parmbsc0), CHARMM | Low. Uses harmonic potentials not designed for bond dissociation. | May require custom anharmonic parameters derived from QM calculations for accurate fission modeling. |

| Coarse-Grained | Groups of atoms | Martini | Very Low. Not applicable as individual bonds are not represented. | Useful for large-scale conformational changes that might follow fission in larger systems, but not the event itself [37] [35]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Combining Coarse-Grained MD with Experimental Scattering Data

This protocol is adapted from methodologies used to study flexible multi-domain proteins and is useful for studying large-scale conformational changes that could be triggered by bond fission in a larger system [37].

System Setup:

- Obtain or generate an initial all-atom structure. If high-resolution structures of domains are available, connect them with modeled flexible linkers using software like Modeller [37].

- Convert the all-atom structure to a coarse-grained representation using a tool like Martinize2 (for the Martini force field) [37].

- Apply an elastic network within folded protein domains using a harmonic potential (e.g., force constant of 500 kJ mol⁻¹ nm⁻² on backbone beads within 0.9 nm) to maintain their structural integrity while allowing inter-domain motion [37].

Simulation Execution:

- Energy minimization and equilibration are performed (e.g., 1 ns in NPT ensemble using a velocity-rescale thermostat and Parrinello-Rahman barostat) [37].

- Run production simulation for sufficient time to sample conformational space (e.g., 10 μs). Frames are saved regularly for analysis (e.g., every ns) [37].

Backmapping and Analysis:

Integration with Experimental Data:

- Use a Bayesian/Maximum Entropy (BME) approach to reweight the simulation ensemble to achieve optimal agreement with experimental SAXS or SANS data [37].

- Validate the refined ensemble against additional experimental data not used in the reweighting.

Protocol 2: Assessing Convergence via Ensemble Simulation

This protocol is critical for establishing the reproducibility and reliability of any MD result, including studies of bond rupture [36].

- Initialization: Prepare the simulation system as usual (solvation, ionization, energy minimization).

- Ensemble Generation: Instead of one long simulation, initiate a set of independent simulations (e.g., 5-10 replicates) from the same initial coordinates but with different randomly assigned initial velocities.

- Execution: Run all simulations for the same, significant duration. The required time is system-dependent, but studies on DNA have shown convergence on the 1–5 μs timescale for internal helix dynamics [36].

- Convergence Analysis:

- Aggregate Data: Combine the data from all ensemble members for analysis.

- Compare to Long Trajectory: If available, compare the aggregated ensemble data to a single, very long simulation (e.g., ~44 μs). The properties of interest (e.g., average bond length distribution in a pre-fission state) should be similar [36].

- Statistical Checks: Use the Kullback-Leibler divergence of principal components or block analysis of key observables to quantitatively assess convergence across the ensemble [36].

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Bond Fission Simulation Troubleshooting Guide

Experimental Validation of Simulation Ensembles

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software and Computational Tools

| Item | Function | Application Context in Bond Fission Studies |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | A versatile software package for performing MD simulations. | Can be used for both all-atom (with custom parameters) and coarse-grained production simulations [37]. |

| AMBER | A suite of biomolecular simulation programs. | Often used with force fields like ff99SB/parmbsc0; its GPU-accelerated version enables long timescale simulations for convergence studies [36]. |

| PLUMED | An open-source library for enhanced sampling and free-energy calculations. | Used to calculate collective variables (e.g., bond length) and implement advanced sampling algorithms to study rare events [37]. |

| Martini Coarse-Grained Force Field | A force field where particles represent groups of atoms, speeding up simulations. | Not for bond fission itself, but for studying the large-scale conformational consequences in bigger systems (e.g., domain separation) [37] [35]. |

| Bayesian/Maximum Entropy (BME) | A computational framework for integrating experimental data with simulation ensembles. | Reweights simulation trajectories to match experimental data like SAXS, ensuring the final model is both physically plausible and experimentally consistent [37]. |

Practical Troubleshooting: Preventing and Fixing Common Bond Stretching Errors

## Frequently Asked Questions

1. What are the most common causes of force field incompatibility? Force field incompatibility often arises from inconsistent parameterization across different force fields for specific chemical groups, leading to divergent geometric outcomes. Key causes include [38]:

- Inconsistent Torsion Parameters: Small differences in dihedral terms can cause molecules to optimize into different conformational minima.