Somatic Cell Molecular Evolution: From Foundational Mechanisms to Clinical Applications in Disease and Aging

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the molecular mechanisms driving somatic cell evolution, a fundamental process with profound implications for cancer, aging, and regenerative medicine.

Somatic Cell Molecular Evolution: From Foundational Mechanisms to Clinical Applications in Disease and Aging

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the molecular mechanisms driving somatic cell evolution, a fundamental process with profound implications for cancer, aging, and regenerative medicine. We explore the foundational principles of somatic mutation and selection in normal tissues, detailing how clonal expansions shape organismal health. The scope extends to cutting-edge methodologies like single-molecule sequencing and cellular reprogramming that are revolutionizing our ability to study and manipulate somatic evolution. We further examine the translational applications of this knowledge, from interpreting complex genomic data in cancer to developing novel anti-aging and drug discovery strategies. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes recent breakthroughs to illuminate both the pathological consequences and therapeutic potential of somatic cell evolution.

The Somatic Mosaic: Unraveling Core Mechanisms of Mutation and Selection in Normal Tissues

Somatic evolution represents the fundamental process by which accumulated genetic alterations and subsequent cellular selection drive clonal expansion within non-germline tissues. This whitepaper examines the molecular mechanisms of somatic evolution, with particular focus on clonal hematopoiesis (CH) as a paradigmatic model system. We explore how somatic mutations acquired throughout an organism's lifespan shape tissue architecture, contribute to aging phenotypes, and create precursors to malignancy. Through integrated analysis of high-throughput sequencing data, evolutionary modeling, and clinical validation, we delineate the progression from neutral mutation accumulation to positive selection of driver mutations. The findings presented herein offer a framework for understanding somatic evolution's role in human disease and identify potential therapeutic targets for interrupting malignant transformation.

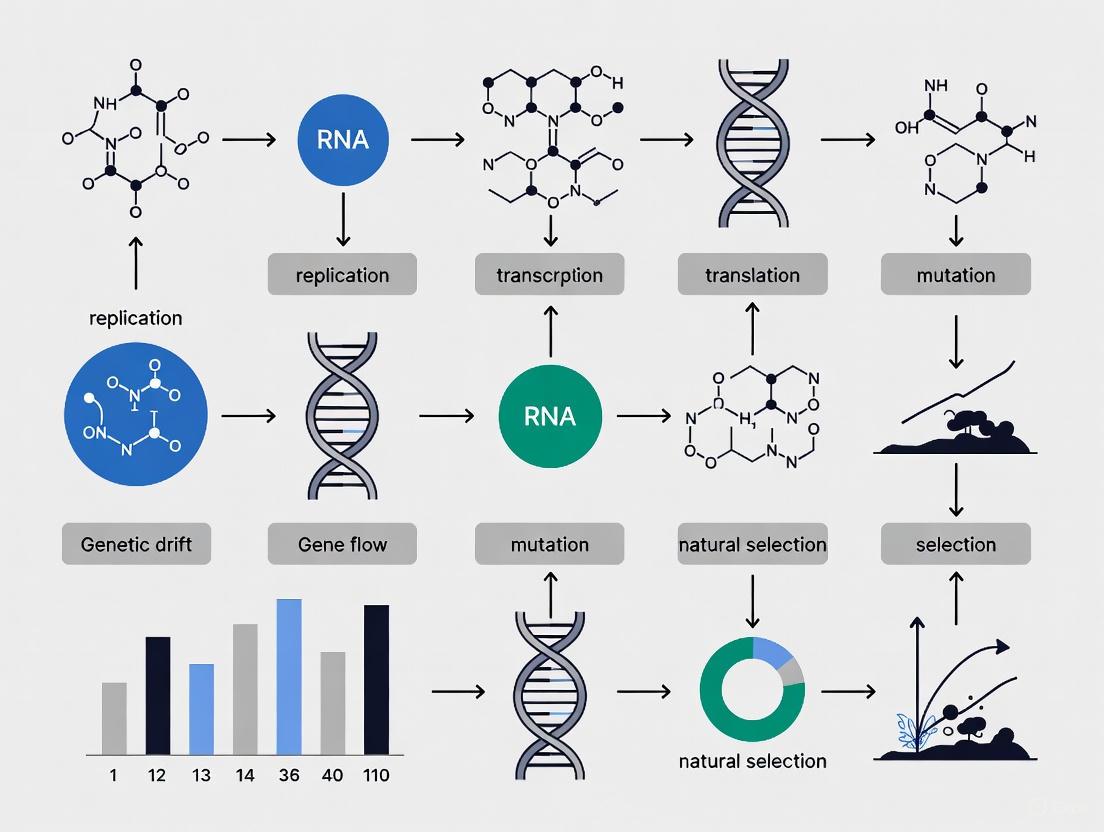

Somatic evolution describes the process by which proliferating cells accumulate genetic mutations over time, leading to clonal expansions that shape tissue architecture and function. This process occurs across all dividing tissues, with particularly profound implications in aging and cancer biology [1]. The conceptual foundation rests on evolutionary principles applied at the cellular level: mutations provide the substrate for selection, while cellular proliferation and differential fitness determine which clones expand [2].

The molecular basis of somatic evolution involves both intrinsic and extrinsic determinants. Intrinsic factors include germline cancer risk loci and acquired somatic mutations that alter cellular fitness, while extrinsic factors encompass environmental mutagens, therapeutic interventions, and immune-mediated selection pressures [1]. These forces collectively drive the clonal dynamics observed in various tissues, with recent technological advances enabling unprecedented resolution in tracking these changes temporally and spatially [2].

Within this broader context, clonal hematopoiesis represents an ideal model system for studying somatic evolution due to its well-characterized hierarchy, accessibility for sampling, and clinical significance across both malignant and non-malignant conditions.

Clonal Hematopoiesis: A Paradigm for Somatic Evolution

Definitions and Clinical Significance

Clonal hematopoiesis (CH) occurs when hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) acquire driver mutations that promote clonal proliferation, resulting in certain cell lineages constituting a disproportionate fraction of circulating blood cells without causing abnormal blood cell counts or other hematologic disease symptoms [3]. The condition known as clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP) is specifically diagnosed when individuals carry somatic mutations in hematological malignancy-associated driver genes at a variant allele frequency (VAF) of ≥2%, yet lack clinical evidence of hematological disease [3].

CHIP is associated with a moderately increased risk of hematological cancer (approximately 0.5-1% per year, representing a 10-fold increase over the general population) and greater likelihood of cardiovascular disease and pulmonary pathology [3]. The prevalence of CH increases dramatically with age, affecting >10% of individuals over 70 years old, with recent high-sensitivity sequencing suggesting it may be nearly ubiquitous in elderly populations [3] [4].

Genetic Landscape and Driver Genes

The mutational landscape of CH is dominated by a growing set of driver genes under positive selection in the hematopoietic system. These can be categorized as follows:

Table 1: Gene Categories in Clonal Hematopoiesis

| Category | Description | Representative Genes |

|---|---|---|

| Classical Fitness-Inferred Drivers | Genes in canonical CH sets showing significant positive selection in population studies | DNMT3A, TET2, ASXL1, PPM1D, JAK2, TP53, SRSF2, SF3B1, BRCC3, PHIP, CBL, KDM6A, GNB2, GNAS [4] |

| Classical Non-Fitness-Inferred Drivers | Genes in canonical CH sets not under significant positive selection in UK Biobank data | RUNX1, PTEN, CUX1 [4] |

| New Fitness-Inferred Drivers | Novel genes identified through population-level selection analysis | ZBTB33, ZNF318, ZNF234, SPRED2, SH2B3, SRCAP, SIK3, SRSF1, CHEK2, CCDC115, CCL22, BAX, YLPM1, MYD88, MTA2, MAGEC3, IGLL5 [4] |

Analysis of 200,618 UK Biobank exomes revealed that approximately 23% of individuals (47,026 people) carried a detectable mutation in either a classical or new CH driver gene, with non-"DTA" (DNMT3A, TET2, ASXL1) CH increased by >50% when including these novel drivers [4]. The dN/dS ratios (nonsynonymous to synonymous mutation ratios) for these genes ranged from 5 to 660, indicating strong positive selection with 5-660 times more nonsynonymous mutations than expected by chance [4].

Quantitative Models and Evolutionary Dynamics

Mathematical Framework for Somatic Evolution

The dynamics of somatic evolution can be modeled using population genetics theory and stochastic processes. A fundamental approach models stem cell dynamics as a collection of individual cells that divide, differentiate, and die stochastically at predefined rates [5]. In this framework, novel mutations occur with each cell division, with each daughter cell acquiring a random number of mutations drawn from a Poisson distribution with rate μ [5].

The time-dynamical expected value of the distribution of variant allele frequencies (VAF spectrum) follows the partial differential equation:

∂v/∂t + ∂/∂κ [v · (λ(κ - 1) - γ(κ + 1) - ρκ)] = μN(t) · δ(κ - 1)

where κ = fN(t) denotes the number of cells sharing a variant, δ(x) is the Dirac delta function, and λ, γ, and ρ represent birth, death, and differentiation/replacement rates respectively [5].

This model incorporates three developmental phases: (1) early developmental exponential growth through symmetric divisions; (2) growth and maintenance with population turnover through asymmetric divisions; and (3) mature phase with constant population size and continued turnover [5].

Age-Associated Changes in Clonal Dynamics

Analysis of healthy tissues reveals distinctive signatures of somatic evolution across the lifespan. In young tissues, the VAF spectrum typically follows a f⁻² power law characteristic of exponentially growing populations [5]. With aging, tissues transition toward a f⁻¹ power law distribution, reflecting homeostatic maintenance of a constant cell population size [5].

Table 2: Age-Related Changes in VAF Spectrum in Healthy Oesophagus Epithelium

| Age Group | VAF Spectrum Characteristics | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Young | Closest to f⁻² distribution | Dominant signature of ontogenic growth |

| Middle | Sigmoidal shape transitioning toward f⁻¹ | Establishment of tissue homeostasis |

| Older | Closer to f⁻¹ homeostatic scaling | Mature homeostatic equilibrium |

This transition occurs as a wavelike front moving from low to high frequency variants, with convergence toward homeostatic equilibrium slowing over time [5]. Similar dynamics are observed in hematopoietic systems, where mutation burden and clone number increase with age [4].

Methodologies for Investigating Somatic Evolution

Sequencing Approaches and Experimental Workflows

Multiple sequencing methodologies provide complementary insights into somatic evolution:

Bulk sequencing approaches enable detection of clonal variants through analysis of variant allele frequency (VAF) spectra, typically identifying one to two small clones per individual at conventional sequencing depths [4]. In contrast, single-cell sequencing reveals dozens of parallel clonal expansions in most individuals by late adulthood, with the majority lacking known driver mutations [4].

For CH studies, sample processing typically involves:

- Blood collection and buffy coat separation for DNA extraction

- Whole exome or whole genome sequencing at appropriate depth (typically >100x for bulk, >30x for single-cell)

- Somatic variant calling using specialized algorithms (e.g., Mutect2, Shearwater)

- Variant filtering to remove germline polymorphisms and artifacts

- Clonal reconstruction and evolutionary analysis [4]

Detection of Positive Selection

The dN/dS methodology quantifies positive selection by comparing the ratio of nonsynonymous to synonymous mutations observed in a gene versus the expected ratio under neutral evolution [4]. A dN/dS ratio significantly greater than 1 indicates positive selection, with the magnitude reflecting selection strength.

Application of this approach to 200,618 UK Biobank exomes revealed a global dN/dS ratio of 1.13 (95% CI 1.11-1.16), suggesting approximately one in every eight nonsynonymous mutations was under positive selection [4]. Selection strength varied by mutation type:

- Missense mutations: 1 in every 8-11 mutations under selection

- Truncating mutations: 1 in every 4-5 mutations under selection

- Splicing mutations: 1 in approximately 3 mutations under selection [4]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Somatic Evolution Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Whole Blood Samples | Source DNA for clonal hematopoiesis studies | Collected in EDTA tubes; buffy coat separation for leukocyte isolation [4] |

| Next-Generation Sequencers | High-throughput DNA sequencing | Platforms enabling whole-exome or whole-genome sequencing at minimum 100x depth for bulk samples [3] |

| Single-Cell DNA Sequencing Kits | Library preparation for single-cell genomics | Protocols enabling whole-genome amplification and sequencing of individual cells [5] |

| Somatic Variant Callers | Identification of somatic mutations from sequencing data | Algorithms optimized for different contexts (e.g., Mutect2, Shearwater) [4] |

| dNdScv R Package | Statistical detection of positive selection | Quantifies gene-level selection using dN/dS ratios [4] |

Clinical Implications and Therapeutic Perspectives

The characterization of somatic evolution, particularly through CH, has profound clinical implications. CH represents a premalignant state that can progress to hematological malignancies, most commonly acute myeloid leukemia (AML) [3]. AML development involves progressive accumulation of cooperating mutations in HSCs, leading to blocked differentiation and accumulation of immature myeloblasts in bone marrow [3].

Beyond hematological malignancies, CH associates with all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, and increased infection risk [4]. These associations likely reflect both direct effects of mutated hematopoietic cells and indirect effects on inflammatory processes.

Emerging therapeutic approaches aim to:

- Eliminate fit clones through selective targeting of mutant cells

- Alter selective environments to disadvantage mutant clones

- Interrupt clonal expansion through anti-inflammatory interventions

- Monitor high-risk individuals for early malignant transformation

Risk stratification remains challenging, with current approaches considering clone size (VAF), specific gene mutations (e.g., TP53, IDH1, IDH2, JAK2 confer higher risk), mutation multiplicity, and patient age [3].

Somatic evolution represents a fundamental biological process with far-reaching implications for human health and disease. Clonal hematopoiesis serves as an accessible model for understanding broader principles of somatic evolution across tissues. Through integrated molecular profiling, evolutionary analysis, and clinical correlation, researchers are developing increasingly sophisticated models of how somatic mutations accumulate, spread, and ultimately contribute to age-associated diseases.

Future directions include comprehensive mapping of all CH drivers, understanding functional consequences of mutations in novel driver genes, developing interception strategies for high-risk clones, and extending these principles to epithelial and other somatic tissues. As our understanding of somatic evolution deepens, it promises to transform approaches to cancer prevention, aging biology, and personalized risk assessment.

Endogenous and Exogenous Drivers of Somatic Mutation Accumulation

Somatic mutations, defined as alterations in the DNA sequence that occur in any cell of the body after conception, represent a fundamental driver of cellular evolution. These changes arise from a complex interplay between endogenous processes originating within the cell itself and exogenous insults from external environmental factors [6]. The systematic accumulation of these genetic alterations throughout an organism's lifespan contributes significantly to aging, functional decline in tissues, and the development of various diseases, most notably cancer [6] [7]. Understanding the precise mechanisms and relative contributions of these mutagenic drivers provides crucial insights into the molecular evolution of somatic cells and opens avenues for therapeutic intervention.

Within the context of somatic cell molecular evolution, somatic mutations create genetic heterogeneity among cells, serving as the substrate upon which selection acts. While the majority of these mutations have minimal functional consequences, certain variants can confer selective advantages, leading to clonal expansions that may eventually dominate tissue landscapes [8] [9]. This process mirrors evolutionary principles at the cellular level, where mutation rates, selective pressures, and population dynamics jointly shape tissue homeostasis and disease progression. The framing of somatic mutation accumulation through this evolutionary lens provides researchers with a powerful conceptual framework for investigating tissue aging, carcinogenesis, and the development of targeted therapeutic strategies.

Quantitative Landscape of Somatic Mutation Accumulation

Patterns Across Tissues and Time

The development of advanced sequencing technologies has revealed that somatic mutations accumulate in a remarkably linear fashion with age across numerous human tissues [6]. This linear relationship suggests a relatively constant rate of mutation accumulation during adult life, providing a quantitative foundation for studying somatic evolution. However, significant differences exist in both the burden and patterns of mutations across different tissue types, reflecting tissue-specific variations in cell turnover, exposure to mutagens, and efficiency of DNA repair mechanisms.

Table 1: Somatic Mutation Accumulation Rates Across Human Tissues

| Tissue/Cell Type | Mutation Rate (SNVs/year) | Key Mutational Processes | Notable Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bile Duct | 9 | SBS1, SBS5 | Lowest rate among studied tissues |

| Liver | 11.7 | SBS1, SBS5 | Rate increases to 56.6/year with SBS40 contribution |

| Blood/Hematopoietic Stem Cells | 16 | SBS1, SBS5 | Basis for clonal hematopoiesis |

| Brain Neurons | 14.7-17.1 | SBS1, SBS5 | Post-mitotic cells accumulating mutations without replication |

| Colon/Appendix | 56 | SBS1, SBS5, SBS88 | Higher rate linked to microbiome and rapid turnover |

| Oral Epithelium | 18-23 | SBS1, SBS5, tobacco/exposure signatures | Rich clonal selection landscape |

The mutation rates presented in Table 1 demonstrate that while all tissues accumulate mutations within the same order of magnitude, specific tissues can exhibit up to a six-fold difference in their annual mutation accumulation rates [6] [8]. This variation highlights how tissue-specific biology and microenvironmental exposures shape mutational landscapes. Notably, even post-mitotic cells such as neurons accumulate mutations at rates comparable to proliferative tissues, indicating that cell division is not the sole determinant of mutagenesis [6] [7].

Early Life versus Adult Mutagenesis

Recent lineage-tracing studies have revealed that the rate of mutation accumulation is not constant throughout the entire lifespan. A particularly accelerated phase of mutagenesis occurs during early development before birth, contrasting with the more constant rates observed during adult life [6]. This developmental period of heightened mutagenesis may have disproportionate impacts on long-term health outcomes, as mutations acquired during early development can be shared by many cells throughout the body, potentially affecting large tissue territories. Furthermore, cancer driver mutations have been documented to arise decades before clinical detection of malignancy, emphasizing the long latency and early origins of some somatic evolutionary processes [6].

Endogenous Drivers of Somatic Mutations

Endogenous mutagenesis originates from internal cellular processes, including DNA replication errors, spontaneous molecular decay, and metabolic byproducts. These processes create characteristic mutational signatures that have been systematically cataloged and can be identified in sequencing data from various tissues.

Universal Clock-like Mutational Processes

Two mutational signatures—Single Base Substitution (SBS) 1 and SBS5—have been identified as nearly universal "clock-like" signatures across human tissues [6]. SBS1 is characterized by C>T transitions and is primarily caused by the spontaneous deamination of methylated cytosine residues to thymine. In contrast, the etiology of SBS5 remains less well-defined but likely represents a composite of multiple endogenous background mutational processes. The constant activity of these processes throughout life results in the linear accumulation of mutations with age, providing a molecular clock that tracks cellular aging [6].

Tissue-Specific Endogenous Processes

Beyond the universal clock-like processes, certain endogenous mutational mechanisms exhibit tissue-specific patterns. The APOBEC family of cytidine deaminases, which normally function in antiviral defense, can become misregulated and cause clustered mutagenesis in specific tissues [6] [10]. This activity generates SBS2 and SBS13 signatures and often occurs in sporadic bursts, affecting subsets of cells within a tissue [6]. APOBEC-mediated mutagenesis has been associated with various cancer types and represents an important example of how physiological processes can be co-opted to drive somatic evolution.

Table 2: Characterized Endogenous and Exogenous Mutational Drivers

| Driver Category | Specific Process/Exposure | Mutational Signature(s) | Associated Tissues/Cancers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Endogenous | Spontaneous cytosine deamination | SBS1 | All tissues |

| Endogenous | Background processes | SBS5 | All tissues |

| Endogenous | APOBEC cytidine deaminase activity | SBS2, SBS13 | Lung, colorectal, breast, gynecological |

| Endogenous | Defective homologous recombination repair | SBS3 | Ovarian, other gynecological cancers |

| Endogenous | Mismatch repair deficiency | MSI, SBS6, SBS14, SBS15, SBS21, SBS26, SBS44 | Colorectal, endometrial |

| Exogenous | Ultraviolet (UV) radiation | SBS7 | Skin, melanocytes |

| Exogenous | Alcohol consumption | SBS16 | Esophagus |

| Exogenous | Tobacco smoking | SBS4 | Lung, oral epithelium |

| Exogenous | Colibactin (E. coli strain) | SBS88 | Colon |

Reactive oxygen species (ROS), generated as byproducts of cellular metabolism, represent another significant endogenous mutagen. ROS can cause oxidative damage to DNA, leading to point mutations and structural variants. The brain, with its high metabolic activity, is particularly susceptible to oxidative damage, contributing to the mutation burden observed in neurons during aging and neurodegeneration [7].

DNA Repair Deficiencies

Deficiencies in DNA repair pathways represent a different class of endogenous mutagenesis, where the failure to correct DNA damage leads to accelerated mutation accumulation. Two particularly important repair deficiencies in the context of cancer include homologous recombination deficiency (HRd) and mismatch repair deficiency (MMRd) [11]. These deficiencies create characteristic mutational signatures and have significant implications for both cancer evolution and therapy. Interestingly, these two deficiency states often show an inverse relationship across cancer types, suggesting possible functional interactions or mutually exclusive evolutionary paths [11].

Exogenous Drivers of Somatic Mutations

Exogenous mutagens originate from external environmental sources and contribute to somatic mutation accumulation through direct DNA damage or interference with DNA repair processes. The relative contribution of exogenous factors varies significantly across tissues, primarily depending on their exposure to the external environment.

Environmental Carcinogens

Ultraviolet (UV) radiation represents one of the most well-characterized exogenous mutagens, primarily affecting skin cells. UV exposure causes characteristic DNA lesions that result in the SBS7 mutational signature, dominated by C>T transitions at dipyrimidine sites [6] [12]. The impact of UV radiation is clearly demonstrated by comparative studies of sun-exposed versus protected skin sites, which show significantly higher mutation loads in exposed areas [12].

Tobacco smoke contains numerous carcinogenic compounds that create a distinct mutational signature (SBS4) in exposed tissues such as lung and oral epithelium [8]. Similarly, alcohol consumption has been associated with SBS16 mutations in esophageal tissues [6]. The effect of these exogenous exposures is not uniform across all individuals, as genetic differences in metabolic pathways can modulate their ultimate mutagenic impact.

Microbiome-Associated Mutagens

The human microbiome represents an underappreciated source of exogenous mutagenesis. Specific bacterial strains, such as colibactin-producing E. coli, have been directly linked to mutational signature SBS88 in colon crypts [6]. This finding highlights how commensal microorganisms can directly influence somatic evolution in their host tissues, creating a complex interplay between microbiome composition and cancer risk.

Methodological Approaches for Studying Somatic Mutations

Advanced Sequencing Technologies

The detection of somatic mutations in normal tissues presents significant technical challenges due to their low variant allele frequency in bulk tissue samples. Several sophisticated approaches have been developed to address this limitation:

Single-cell Derived Clonal Lineages: This method involves expanding single cells into clonal populations in culture, followed by whole-genome sequencing. This approach allows for accurate mutation detection without amplification artifacts and enables independent validation of identified mutations [12]. The minimal propagation in culture preserves the native mutation burden accumulated in vivo.

Duplex Sequencing (NanoSeq): NanoSeq represents a major technological advancement that achieves error rates below 5 × 10^{-9} errors per base pair by sequencing both strands of DNA molecules independently [8]. This ultra-low error rate enables the detection of mutations present in single DNA molecules, allowing comprehensive profiling of driver mutations and mutational signatures in highly polyclonal samples without the need for single-cell isolation or clonal expansion.

Single-cell Whole Genome Sequencing: Direct sequencing of single cells after whole-genome amplification provides another approach for studying somatic mutations, particularly in non-dividing cells. While historically limited by high error rates, recent technical and bioinformatic innovations have significantly improved accuracy [6].

Analytical Frameworks

Mutational Signature Analysis: This analytical approach decomposes the patterns of mutations observed in sequencing data into characteristic signatures associated with specific mutational processes [6] [11]. The method relies on non-negative matrix factorization and compares extracted signatures to reference sets in databases such as COSMIC.

Selection Analysis (dNdScv): The dNdScv algorithm detects genes under positive selection by comparing the ratio of non-synonymous to synonymous mutations (dN/dS) while accounting for mutational heterogeneity across genes [8] [9]. This approach has been instrumental in identifying cancer driver genes from normal tissue sequencing data.

Regional Enrichment Methods (iSiMPRe): Methods like iSiMPRe identify significantly mutated protein regions by detecting clusters of missense mutations and in-frame indels beyond random expectation [13]. This approach provides higher resolution than gene-level analyses and can pinpoint specific functional domains targeted by selection.

Experimental Workflows in Somatic Mutation Research

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Methodological Solutions

| Category/Reagent | Specific Application | Function/Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| NanoSeq Protocols | Genome-wide mutation detection in polyclonal samples | Ultra-low error rate sequencing enables single-molecule sensitivity for comprehensive variant profiling |

| Single-cell RNA-seq | Cellular heterogeneity assessment | Characterizes transcriptional diversity and cell states in mutated clones |

| APOBEC3B Inhibitors (e.g., 3,5-diiodotyrosine) | Experimental intervention studies | Specifically inhibits APOBEC3B deaminase activity to assess its role in mutagenesis |

| FoldX Algorithm | Protein stability prediction | Computes ΔΔG values to evaluate structural impact of missense mutations |

| dNdScv Algorithm | Selection analysis in coding sequences | Identifies genes under positive selection using dN/dS ratios with mutational context modeling |

| iSiMPRe | Regional mutation enrichment analysis | Detects significantly mutated protein regions beyond gene-level signals |

| COSMIC Mutational Signatures | Reference database | Curated catalog of mutational signatures for comparative analysis |

| Organoid Culture Systems | Functional validation | Enables experimental study of mutation impact in near-physiological tissue contexts |

The accumulation of somatic mutations throughout life represents a complex interplay between endogenous biological processes and exogenous environmental exposures. The linear increase of mutations with age across diverse tissues, coupled with tissue-specific variations in mutation rates and patterns, reveals a dynamic landscape of somatic evolution. Endogenous processes, including clock-like mutagenesis and DNA repair deficiencies, create a baseline mutation rate that is further modulated by exogenous factors such as UV radiation, tobacco smoke, and microbiome-derived genotoxins.

Technological advances in sequencing methodologies, particularly single-molecule approaches like NanoSeq, have revolutionized our ability to study somatic mutations at unprecedented resolution. These tools, combined with sophisticated analytical frameworks for detecting selection and mutational signatures, provide researchers with powerful means to investigate the fundamental mechanisms of somatic evolution. The continuing refinement of these approaches promises to deepen our understanding of how somatic mutations contribute not only to cancer but also to aging and other diseases, potentially opening new avenues for prevention and therapeutic intervention.

Mutational Drivers and Their Biological Consequences

Landscape of Positive and Negative Selection in Non-Cancerous Tissues

Somatic evolution, the accumulation of mutations in body cells throughout a lifetime, represents a fundamental process in human biology and disease. While extensively studied in cancer, the landscape of positive and negative selection operating in non-cancerous tissues remains a critical area of investigation for understanding tissue homeostasis, aging, and carcinogenesis. This technical guide examines the mechanisms, measurement approaches, and functional significance of selection pressures acting on somatic cells in normal tissues, framed within the broader context of somatic cell molecular evolution research.

The evolutionary dynamics in somatic tissues differ substantially from canonical species evolution. In non-cancerous tissues, negative selection plays a predominant role in eliminating deleterious mutations that compromise cellular function, while positive selection occasionally promotes advantageous mutations that enhance cellular fitness within specific contexts. Understanding the balance between these opposing forces provides crucial insights into tissue maintenance mechanisms and the earliest stages of malignant transformation [14] [15].

Theoretical Framework of Somatic Selection

Fundamental Principles

Somatic evolution in non-cancerous tissues operates under three necessary and sufficient conditions for natural selection: (1) variation exists through genetic and epigenetic alterations accumulating in somatic cells; (2) these alterations are heritable through cellular replication; and (3) the variations affect cellular fitness, influencing proliferation or survival capabilities [15]. Unlike germline evolution, somatic selection occurs within individual organisms, creating complex mosaics of genetically distinct cell populations.

The selection landscape varies significantly across tissue types and developmental stages. Tissues with high cellular turnover experience stronger selective pressures due to increased replication-associated mutations, while post-mitotic tissues may accumulate mutations through alternative mechanisms. The selection intensity correlates with both the mutation rate and the functional consequences of genetic alterations in specific cellular contexts [14] [16].

Distinguishing Selection Types

Positive selection enhances the frequency of somatic mutations that confer fitness advantages, such as increased proliferation, resistance to apoptosis, or improved stress adaptation. In contrast, negative selection (purifying selection) eliminates deleterious mutations that compromise essential cellular functions or reduce competitive fitness [16].

In non-cancerous tissues, negative selection predominates to maintain tissue function and architecture, though its efficacy varies across tissue types and genetic loci. Quantitative analyses reveal that negative selection operates with varying strength across the genome, with essential genes and tumor suppressor genes experiencing particularly strong purifying selection to prevent functional compromise [17] [16].

Quantitative Landscape of Somatic Selection

Selection Metrics and Patterns

Advanced sequencing technologies have enabled quantitative assessment of selection pressures in non-cancerous tissues. The metrics for evaluating selection strength include mutation frequency comparisons, dN/dS ratios adapted for somatic evolution, and functional consequence analyses.

Table 1: Quantitative Measures of Selection in Somatic Tissues

| Measure | Application | Interpretation | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| dN/dS ratio | Comparing non-synonymous to synonymous mutation rates | dN/dS >1 indicates positive selection; dN/dS <1 indicates negative selection | Requires sufficient mutation burden for statistical power |

| Mutation recurrence | Identifying genomic regions with unexpectedly high/low mutation frequencies | Recurrent mutations suggest positive selection; mutation deserts indicate negative selection | Confounded by regional mutation rate variation |

| Functional impact bias | Assessing enrichment of mutations with predicted functional consequences | Excess of high-impact mutations suggests positive selection; depletion indicates negative selection | Depends on accurate functional prediction algorithms |

| Clonal expansion | Tracking size and persistence of mutant cell populations | Large clones indicate fitness advantage; restricted clones suggest negative selection | Influenced by tissue organization and stem cell dynamics |

Analyses across multiple tissue types demonstrate that negative selection predominates in most non-cancerous somatic contexts, with dN/dS ratios typically below 1.0. However, the strength of purifying selection varies substantially across gene categories, with essential genes showing the strongest signals of negative selection [16].

Tissue-Specific Selection Patterns

Selection pressures operate differently across tissues due to variations in cellular turnover, environmental exposures, and functional constraints. Tissues with high regenerative capacity (e.g., intestinal epithelium, skin) demonstrate more pronounced positive selection for mutations enhancing proliferation and survival. In contrast, tissues with limited cellular turnover (e.g., nervous tissue) exhibit different selective landscapes focused on maintaining functional integrity.

Table 2: Tissue-Specific Selection Patterns in Non-Cancerous Human Tissues

| Tissue Type | Dominant Selection Pressure | Characteristic Features | Implications for Disease |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood/Immune | Balanced positive and negative selection | Age-related clonal hematopoiesis driven by positive selection | Predisposition to hematologic malignancies |

| Intestinal Epithelium | Moderate positive selection | Crypt competition and clonal expansions | Field cancerization in inflammatory bowel disease |

| Skin | Environment-dependent selection | UV-induced mutations with context-dependent fitness | Selection of p53 mutants in sun-exposed skin |

| Liver | Regeneration-associated selection | Clonal expansions during chronic injury | Cirrhosis as precursor to hepatocellular carcinoma |

| Nervous Tissue | Predominantly negative selection | Limited clonal expansion due to post-mitotic state | Neurodegeneration associated with mutation accumulation |

Recent studies utilizing machine learning approaches have revealed that tissue-specific gene expression patterns significantly influence aneuploidy tolerance and selection pressures. Chromosome arms enriched for genes essential in specific tissues experience stronger negative selection when disrupted, demonstrating how functional context shapes somatic evolution [17].

Experimental Methodologies

Flow Cytometry-Based Analysis of Thymic Selection

The thymus provides a well-characterized model for studying negative selection in non-cancerous tissue. The following protocol enables quantitative assessment of positive and negative selection during T cell development [18]:

Tissue Dissection and Cell Preparation

- Euthanize mice using CO₂ according to approved ethical guidelines

- Secure mouse ventral side up and sterilize with 70% ethanol

- Make ventral incision from genitalia to chin, then extend incisions along limbs

- Harvest thymus by carefully removing rib cage to expose mediastinal contents

- Identify bilobed thymus above heart, gently remove using flat-edged forceps

- Place thymus on sterile steel mesh screen in Petri dish with 5ml Hank's Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) on ice

- Mechanically dissociate tissue using 3ml syringe plunger until only connective tissue remains

- Rinse mesh screen with HBSS and collect cell suspension

- Pellet cells by centrifugation at 335 × g for 5 minutes at 4°C

- Resuspend thymocytes at 20 × 10⁶ cells/ml in FACS buffer (PBS, 1% FCS, 0.02% sodium azide)

Cell Staining and Flow Cytometry

- Aliquot 4 × 10⁶ thymocytes per sample into 96-well plate

- Block Fc receptors with anti-CD16/32 (clone 2.4G2) for 10 minutes on ice

- Wash cells twice with FACS buffer

- Prepare antibody cocktails in FACS buffer:

- For polyclonal repertoire: anti-TCRβ, anti-CD4, anti-CD8, anti-CD69 or anti-CD5, anti-CD24

- For TCR transgenic models: anti-clonotypic TCR, anti-CD4, anti-CD8, anti-CD69 or anti-CD5, anti-CD24

- Incubate cells with antibody cocktails for 30 minutes on ice in dark

- Wash cells twice with FACS buffer

- Resuspend in FACS buffer for acquisition on flow cytometer

- Include FSC-A and FSC-W parameters for doublet discrimination

Data Analysis Strategy

- Gate lymphocytes using FSC-A versus SSC

- Exclude doublets using FSC-A versus FSC-W (select FSC-Wlo population)

- For polyclonal T cells: analyze CD4/CD8 expression to identify DN, DP, CD4SP, and CD8SP populations

- Assess positive selection using TCRβ versus CD24 or TCRβ versus CD69 staining

- For TCR transgenic models: first gate on TCR-transgenic cells before CD4/CD8 analysis

- Quantify cellular subsets by multiplying organ cellularity by sequential gating frequencies

Figure 1: Thymic T Cell Selection Pathways. Diagram illustrates the developmental progression and selection checkpoints during T cell maturation in the thymus.

Detection of Negative Selection in Human Autoreactive T Cells

Novel humanized mouse models enable the study of negative selection mechanisms relevant to human autoimmunity. The following approach demonstrates negative selection of insulin-reactive T cells [19]:

Humanized Mouse Model Development

- Generate HLA-DQ8⁺ human immune systems from hematopoietic stem cells

- Introduce Clone 5 TCR transgene specific for insulin B:9-23/HLA-DQ8

- Track thymocyte development at double positive and single positive stages

- Compare selection efficiency with and without hematopoietic HLA expression

Assessment of Selection Efficiency

- Analyze thymic cellularity and subset distribution by flow cytometry

- Quantify autoreactive T cell frequencies in thymus and periphery

- Evaluate requirement for intrathymic antigen presenting cell types

- Assess medullary thymic epithelial cell contribution to negative selection

This experimental system demonstrates that efficient negative selection of human autoreactive T cells requires antigen presentation by both hematopoietic cells and medullary thymic epithelial cells, with defects leading to autoimmune potential.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Somatic Selection

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Selection Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immunomagnetic Separation Kits | EasySep Human/Mouse Negative Selection Kits | Isolation of unlabeled target cells by depleting unwanted populations | Negative selection without antibody binding to cells of interest |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies | Anti-CD4, CD8, TCRβ, CD24, CD69, CD5 | Immunophenotyping of developmental stages and activation states | Assessment of positive and negative selection in thymocyte development |

| TCR Transgenic Models | HYcd4 model, Clone 5 TCR model | Study of antigen-specific selection with physiological timing | Analysis of negative selection mechanisms in autoreactive T cells |

| Cell Culture Media | HBSS, FACS buffer, sterile RPMI + 10% FCS | Maintenance of cell viability during processing | Preservation of native cell states for selection analysis |

| Magnetic Particles | EasySep Magnetic Particles | Positive or negative selection via antibody conjugation | Flexible separation approaches for different downstream applications |

Technical and Analytical Considerations

Method Selection Guidelines

The choice between positive and negative selection approaches depends critically on downstream applications. Negative selection is preferable when unlabeled, unaffected cells are required, particularly for functional assays or transcriptional analyses where antibody binding might alter cellular physiology. This approach provides minimal sample manipulation and avoids potential activation artifacts [20].

Positive selection offers higher purity when targeting specific populations and enables isolation of rare cell subsets. However, researchers must consider potential impacts of antibody binding on cell function, including unintended intracellular signaling or interference with subsequent assays. For complex isolation strategies, sequential positive and negative selection can achieve purification of populations defined by multiple markers [20].

Quantitative Constraints on Negative Selection

The efficacy of negative selection in somatic tissues faces fundamental biological constraints. The limited duration of selective phases restricts the number of self-antigens that can be effectively screened. Computational models indicate that negative selection operates most efficiently on antigens presented by dendritic cells, which may define the practical scope of central tolerance [21].

In non-cancerous tissues, the balance between negative selection efficiency and the number of potential target antigens creates quantitative trade-offs. Tissues with exceptionally diverse antigen repertoires may experience incomplete negative selection, permitting some autoreactive cells to escape central tolerance mechanisms. This constraint has important implications for understanding autoimmune disease pathogenesis [21] [19].

Computational Approaches and Data Integration

Machine Learning Applications

Recent advances in interpretable machine learning enable comprehensive analysis of selection patterns across tissues. These approaches integrate multiple genomic features to model aneuploidy landscapes and selection pressures [17]:

Feature Categories for Selection Models

- Chromosome-arm features: OG density, TSG density, essential gene density

- Cancer tissue features: gene expression in primary tumors, gene essentiality scores

- Normal tissue features: gene expression in matched normal tissues, tissue-specific protein interactions, paralog compensation

Model Interpretation Strategies

- SHAP (Shapley Additive exPlanations) analysis for feature importance quantification

- Relative contribution estimation for positive versus negative selection drivers

- Tissue-specific feature weighting to identify context-dependent selection pressures

These analyses demonstrate that negative selection plays a more significant role in shaping somatic evolution landscapes than previously appreciated, with tumor suppressor gene density emerging as a better predictor of aneuploidy patterns than oncogene density [17].

Integration of Multi-Omics Data

Comprehensive understanding of somatic selection requires integration of genomic, epigenomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data. The heterogeneous nature of somatic mutations necessitates specialized analytical approaches that account for tissue architecture, cellular lineage relationships, and spatial organization.

Advanced algorithms that reconstruct clonal phylogenies from sequencing data enable retrospective inference of selection pressures operating during tissue development and maintenance. These approaches reveal that negative selection efficiently removes most deleterious mutations, while positive selection acts sporadically on driver mutations in specific tissue contexts [14] [16].

The landscape of positive and negative selection in non-cancerous tissues represents a dynamic equilibrium that maintains tissue function while permitting adaptive responses to environmental challenges. Quantitative assessment of these selection pressures provides crucial insights into tissue homeostasis, aging, and the earliest stages of malignant transformation. Continued development of sophisticated experimental models and computational approaches will further elucidate the complex evolutionary dynamics operating within somatic tissues, with important implications for understanding human health and disease.

The Role of Somatic Evolution in Aging and Age-Related Functional Decline

Somatic evolution refers to the process by which accumulating mutations and clonal expansions alter the cellular composition of tissues throughout an organism's lifetime. Recent advances in high-resolution sequencing technologies have revealed that normal tissues become extensively colonized by somatic clones carrying cancer-associated mutations in an aging-dependent fashion [22]. This phenomenon represents a fundamental biological process that contributes significantly to both age-related functional decline and increased disease susceptibility. The understanding that older individuals possess over 100 billion cells with cancer-associated mutations underscores the magnitude of this process and its potential impact on tissue homeostasis [22]. This whitepaper examines the mechanisms, measurement approaches, and implications of somatic evolution in aging, providing researchers with technical frameworks for investigating this emerging field.

Molecular Mechanisms Linking Somatic Evolution to Aging

Fundamental Evolutionary Forces in Aging Tissues

Somatic evolution in aging tissues operates through principles of natural selection at the cellular level, where mutations conferring proliferative advantages lead to clonal expansions. The evolutionary theory of antagonistic pleiotropy posits that genetic variants beneficial during early life stages may become detrimental in post-reproductive ages [22]. In somatic evolution, this manifests as mutations that enhance cellular fitness or survival in aged microenvironments but ultimately compromise tissue function. The life-history theory framework explains how natural selection favors somatic maintenance strategies that maximize reproductive success, with protective mechanisms waning as reproduction becomes less likely [22]. This evolutionary perspective provides a foundation for understanding why somatic evolution becomes increasingly prevalent in later life.

The dynamics of somatic evolution are further shaped by cellular fitness landscapes that change with age. Young, healthy tissues actively suppress the outgrowth of malignant clones through cell competition mechanisms, while aged tissue microenvironments often promote the initiation and progression of malignancies [22]. Key factors influencing these dynamics include:

- Declining immune surveillance reduces elimination of aberrant cells

- Altered niche signaling creates permissive environments for clonal expansion

- Accumulated senescent cells secrete inflammatory factors that promote somatic evolution

- Tissue architecture breakdown removes physical barriers to clonal spread

Key Mutational Processes and Driver Genes

Somatic evolution is fueled by both continuous mutational processes and specific driver events. Studies measuring the distribution of fitness effects (DFE) have quantified the selective advantages conferred by specific mutations in normal tissues [23] [24]. The ratio of non-synonymous to synonymous mutations (dN/dS) has emerged as a powerful method to detect selection in somatic cells, with values >1 indicating positive selection, =1 indicating neutral evolution, and <1 indicating negative selection [23].

Research on normal esophagus and skin tissues has revealed a broad distribution of fitness effects, with the largest fitness increases found for TP53 and NOTCH1 mutants, conferring proliferative advantages of approximately 1-5% [23] [24]. The table below summarizes key driver genes and their fitness effects across tissues:

Table 1: Key Driver Genes in Somatic Evolution and Their Fitness Effects

| Gene | Tissue | Fitness Effect | Biological Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| TP53 | Esophagus, Skin | 1-5% proliferative advantage | Disrupted apoptosis, genomic instability |

| NOTCH1 | Esophagus, Skin | 1-5% proliferative advantage | Altered differentiation signaling |

| DNMT3A | Blood | ~2% VAF associated with CHIP | Epigenetic dysregulation, clonal hematopoiesis |

| TET2 | Blood | ~2% VAF associated with CHIP | DNA hypomethylation, inflammatory signaling |

| PPM1D | Blood, Oral epithelium | Clonal expansion | Altered stress response signaling |

Recent large-scale studies applying ultra-sensitive sequencing methods like NanoSeq have expanded our understanding of the somatic evolution landscape. A 2025 study analyzing 1,042 non-invasive samples of oral epithelium identified 46 genes under positive selection, with more than 62,000 driver mutations detected across the cohort [25]. This rich selection landscape demonstrates the extensive molecular heterogeneity that emerges in aging tissues.

Quantitative Assessment of Somatic Evolution

Mutation Rates and Clonal Dynamics Across Tissues

Somatic mutations accumulate linearly with age in a tissue-specific manner, largely due to endogenous mutational processes but also influenced by mutagen exposures, germline variation, and disease states [25]. Quantitative measurements across tissues reveal distinct patterns of mutational accumulation:

Table 2: Age-Associated Mutation Rates Across Human Tissues

| Tissue | Mutation Rate (per cell per year) | Key Influencing Factors | Technical Measurement Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral epithelium | ~23 SNVs (whole genome) [25] | Tobacco, alcohol, age | Targeted NanoSeq, whole-genome NanoSeq |

| Blood | ~15 SNVs (whole genome) [25] | Age, clonal hematopoiesis | Duplex sequencing, single-cell sequencing |

| Esophagus | Comparable to oral epithelium [22] | Age, gastroesophageal reflux | Deep sequencing, dN/dS analysis |

| Skin | Tissue-specific rates [23] | UV exposure, age | Targeted sequencing, lineage tracing |

The development of error-corrected sequencing methods has been crucial for accurately quantifying these mutation rates. The recent introduction of enhanced nanorate sequencing (NanoSeq) achieves error rates lower than five errors per billion base pairs, enabling detection of mutations present in single cells [25]. This technological advancement has revealed that previous methods significantly underestimated the prevalence of somatic mutations due to detection limits.

Clonal Expansion Metrics and Tissue Colonization

The extent of clonal expansions can be quantified through several metrics, including variant allele frequency (VAF) distributions, clone size distributions, and clone number diversity. Studies of clonal hematopoiesis demonstrate that the fraction of leukocytes occupied by mutant clones increases exponentially starting at approximately 40 years of age [22]. In epithelial tissues such as esophagus, endometrium, and skin, mutant clones come to dominate the tissue architecture in older individuals [22].

Application of mathematical models to clone size distributions enables estimation of selective coefficients for driver mutations. The relationship between clone size and selective advantage follows principles of population genetics, adapted for somatic cell populations [23]. For stem cell-maintained tissues, the long-term population dynamics are controlled by an approximately fixed-size set of equipotent stem cells undergoing a process of neutral competition, which can be modeled using branching processes [23].

Figure 1: Logical Framework of Somatic Evolution in Aging. This diagram illustrates the causal relationships between age-associated mutation accumulation, selection forces, clonal expansion, and functional decline.

Methodological Approaches for Studying Somatic Evolution

Advanced Sequencing Technologies

The study of somatic evolution in aging requires specialized methodologies capable of detecting low-frequency mutations in complex tissue samples. Key technological advances include:

Duplex Sequencing Methods: Techniques such as NanoSeq achieve ultra-low error rates (below 5 × 10^-9 errors per base pair) by tracking both strands of DNA molecules, effectively eliminating sequencing artifacts [25]. Recent improvements have enabled whole-exome and targeted capture applications while maintaining single-molecule sensitivity. The protocol uses restriction enzyme fragmentation without end repair and dideoxynucleotides during A-tailing to prevent error transfer between strands [25].

Single-Cell Sequencing Approaches: Methods for detecting somatic variants using single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) enable reconstruction of cell lineage trees whose structure correlates with chronological age [26]. The "Cell Tree Rings" approach uses de novo single-nucleotide variants detected in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells to construct phylogenetic trees that serve as biological aging timers [26].

Targeted Sequencing Panels: Application of targeted NanoSeq to specific gene panels (e.g., 239 genes covering 0.9 Mb) enables cost-effective profiling of large cohorts [25]. This approach has been successfully applied to 1,042 individuals in buccal swab samples, demonstrating scalability for population-level studies of somatic evolution.

Computational and Mathematical Frameworks

Quantitative interpretation of somatic evolution data requires specialized computational approaches:

dN/dS Analysis Adapted for Somatic Evolution: The ratio of non-synonymous to synonymous mutations, originally developed for species evolution, has been adapted for somatic evolution with modifications to account for rapid evolution, lack of recombination, and complex clonal dynamics [23]. Mathematical frameworks now link dN/dS values to selective coefficients in somatic tissues, enabling quantification of fitness effects.

Interval dN/dS (i-dN/dS): To address limitations of sparse data and measurement uncertainties, interval dN/dS aggregates mutation counts over frequency ranges, providing robust inference of selection coefficients [23]. The formula is defined as:

[ i\frac{dN}{dS} = \frac{\mup}{\mud} \frac{\int{f{min}}^{f{max}} g(\theta, \mud, s, f) df}{\int{f{min}}^{f{max}} g(\theta, \mup, s=0, f) df} ]

Where (\mup) and (\mud) represent passenger and driver mutation rates, (g) is the expected number of mutations, and (s) is the selection coefficient [23].

Clone Size Distribution Modeling: Mathematical descriptions of population dynamics predict the shape of clone size distributions under different evolutionary models, enabling inference of stem cell dynamics and selection strengths from sequencing data [23].

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Studying Somatic Evolution. This diagram outlines the key steps from sample collection through computational analysis in somatic evolution research.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Methods

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Somatic Evolution Studies

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Technologies | NanoSeq [25], Duplex Sequencing [25], scRNA-seq [26] | Ultra-low error variant detection, single-cell analysis | Error rates <5×10^-9, compatibility with damaged DNA |

| Computational Tools | dNdScv [25], Interval dN/dS [23] | Detection of selection, fitness effect quantification | Adaptation to somatic evolution assumptions |

| Targeted Panels | Custom gene panels (239 genes, 0.9 Mb) [25] | Cost-effective driver screening | Optimized for clonal hematopoiesis, epithelial drivers |

| Biological Samples | Buccal swabs [25], Peripheral blood mononuclear cells [26] | Non-invasive longitudinal sampling | Protocols to minimize contamination (saliva, blood) |

| Model Systems | Mouse models [22], in vitro culture systems [22] | Experimental perturbation studies | Lineage tracing, barcoding approaches |

Implications for Age-Related Functional Decline and Disease

Non-Malignant Consequences of Somatic Evolution

While somatic evolution represents a first step toward cancer development, its impact extends beyond malignancy to contribute directly to age-related functional decline. Clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminant potential (CHIP) is associated with substantial increases in the risk of not only leukemia but also cardiovascular disease, lung diseases, frailty, and overall mortality [22]. These non-malignant consequences arise through several mechanisms:

Inflammatory Priming: Expanded clones frequently promote and are promoted by inflammation, creating feed-forward loops that accelerate tissue dysfunction [22]. For example, TET2 mutations in hematopoietic cells enhance production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-1β, contributing to atherosclerosis and cardiac dysfunction.

Tissue Architecture Disruption: In epithelial tissues, clonal expansions can disrupt normal tissue organization and function. Studies of esophageal and endometrial tissues show that older individuals become dominated by mutant clones that alter tissue homeostasis without necessarily progressing to cancer [22].

Stem Cell Exhaustion: Clonal expansions can deplete the functional stem cell pool or alter stem cell differentiation capacity, leading to impaired tissue regeneration and functional decline [27].

Somatic Evolution as a Biomarker of Aging

The quantitative relationship between somatic mutation accumulation and chronological age suggests potential applications as aging biomarkers. The "Cell Tree Rings" concept demonstrates that cell lineage tree structure constructed from somatic mutations correlates with chronological age (Pearson correlation = 0.81) and predicts certain clinical biomarkers better than chronological age alone [26]. Specific metrics derived from phylogenetic trees, including tree balance, depth, and branching patterns, capture information about the history of clonal dynamics and selective pressures throughout the lifespan.

Somatic evolution represents a fundamental mechanism driving aging and age-related functional decline. The integration of ultra-sensitive sequencing technologies, sophisticated computational models, and large-scale population studies has revealed the astonishing scale and complexity of this process. Future research directions should focus on:

- Longitudinal Studies: Tracking clonal dynamics over time within individuals to understand the tempo and mode of somatic evolution

- Spatial Mapping: Characterizing the geographic distribution of clones within tissues to understand microenvironmental influences

- Intervention Strategies: Developing approaches to modulate somatic evolutionary processes, potentially through altering selective landscapes or enhancing immune surveillance

- Multi-Omic Integration: Combining mutational data with epigenetic, transcriptomic, and proteomic profiles to understand functional consequences of clonal expansions

The field of somatic evolution in aging represents a convergence of evolutionary biology, cancer research, and geroscience, offering novel insights into the fundamental mechanisms of aging and potential strategies for extending healthspan.

Chromatin Remodeling and Epigenetic Alterations as Key Regulators of Cell Fate

Chromatin remodeling and epigenetic modifications constitute the primary regulatory layer governing cell fate decisions, from somatic cell reprogramming to oncogenic transformation. This whitepaper synthesizes current research demonstrating how ATP-dependent chromatin remodelers and chemical modifications to DNA and histones dynamically control chromatin accessibility, thereby directing transcriptional programs that determine cellular identity. Within somatic cell molecular evolution, these epigenetic mechanisms facilitate phenotypic plasticity without altering underlying DNA sequences, enabling both adaptive responses and pathological transitions in cancer and aging. Emerging therapeutic strategies now target these systems, with inhibitors of chromatin remodeling complexes showing promising preclinical efficacy against transcription factor-dependent cancers. The integration of advanced sequencing technologies and imaging approaches provides unprecedented resolution of epigenetic dynamics, offering novel diagnostic and therapeutic avenues for manipulating cell fate in regenerative medicine and oncology.

The eukaryotic genome is packaged into chromatin, a complex of DNA and histone proteins whose fundamental unit is the nucleosome—approximately 147 base pairs of DNA wrapped around an octamer of core histones (H2A, H2B, H3, and H4) [28]. Chromatin exists in dynamic states that regulate DNA accessibility to transcriptional machinery, with this plasticity governed by two interconnected mechanisms: epigenetic modifications and ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling. Epigenetic modifications encompass chemical alterations to DNA (e.g., cytosine methylation) and histones (e.g., acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation) that influence chromatin structure and function without changing the DNA sequence itself [29]. Chromatin remodeling complexes are multi-protein machines that utilize ATP hydrolysis to physically reposition, eject, or restructure nucleosomes, thereby controlling DNA accessibility [28] [30]. Together, these systems establish heritable epigenetic states that guide cell fate decisions during development, tissue homeostasis, and disease progression, particularly in the context of somatic cell evolution where environmental influences can trigger molecular reprogramming events.

Major Chromatin Remodeling Complexes and Their Mechanisms

ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes are categorized into four evolutionarily conserved families based on their catalytic subunits and functional characteristics. These complexes perform distinct but complementary roles in regulating nucleosome positioning and composition.

Table 1: Major Chromatin Remodeling Complex Families and Their Functions

| Complex Family | Key ATPase Subunits | Primary Functions | Biological Roles |

|---|---|---|---|

| SWI/SNF | BRG1, BRM | Nucleosome sliding, ejection; creates irregular nucleosome spacing | Transcriptional activation, differentiation, tumor suppression [28] [31] |

| ISWI | SMARCAD1, SNFL2 | Nucleosome assembly, sliding; establishes regular nucleosome spacing | Chromatin compaction, transcription repression, DNA repair [28] [30] |

| CHD | CHD1-CHD9 | Nucleosome positioning, histone variant exchange | Transcriptional regulation, embryonic development [28] [30] |

| INO80 | INO80, EP400/p400 | Histone variant exchange (H2A.Z), nucleosome spacing | DNA repair, transcriptional regulation, stem cell maintenance [28] [32] |

These complexes employ three fundamental mechanisms to modify chromatin structure: (1) editing assembled nucleosomes through replacement, movement, or removal; (2) assembling and organizing nucleosomes from random deposition into regularly spaced arrays; and (3) altering chromatin architecture to enhance DNA accessibility for transcription factors and other regulatory proteins [30]. The TIP60 complex exemplifies this integrated functionality, combining histone acetyltransferase activity (through its TIP60/KAT5 subunit) with chromatin remodeling capability (via its EP400 ATPase subunit) to facilitate histone acetylation and incorporation of the H2A.Z variant in a coordinated manner [32].

Key Epigenetic Modifications and Detection Methodologies

Beyond nucleosome positioning, chemical modifications to DNA and histones constitute a critical layer of epigenetic regulation. Over 100 distinct histone modifications have been identified, including acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitylation, which collectively influence chromatin accessibility and transcription factor binding [29]. DNA methylation primarily occurs at cytosine bases in CpG dinucleotides, forming 5-methylcytosine (5mC), which typically represses transcription when located in promoter regions [33] [29]. Recent technological advances have enabled precise mapping of these modifications across the genome.

Table 2: Advanced Sequencing Methods for Epigenetic Modifications

| Modification Type | Sequencing Method | Resolution | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Histone Modifications | ChIP-Seq [29] | ~200 bp | Genome-wide mapping of histone marks |

| CUT&RUN [29] | ~20 bp | High-resolution protein-DNA interactions | |

| CUT&Tag [29] | Single-cell | Single-cell epigenomic profiling | |

| DNA Methylation (5mC/5hmC) | Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) [29] | Base-level | Gold standard for 5mC/5hmC mapping |

| EM-Seq [29] | Base-level | Bisulfite-free methylation detection | |

| TAPS [29] | Base-level | Quantitative, bisulfite-free mapping | |

| Chromatin Accessibility | ATAC-Seq [34] [33] | Single-nucleosome | Genome-wide accessibility profiling |

| DNase-Seq | ~100 bp | Sensitive nuclease accessibility mapping |

The development of CUT&RUN and CUT&Tag technologies represents a significant advancement over traditional ChIP-Seq, offering higher resolution with lower background signal and requiring substantially less input material [29]. For DNA methylation, emerging bisulfite-free methods like EM-Seq and TAPS overcome the substantial DNA degradation associated with traditional bisulfite treatment, enabling more accurate quantification of methylation patterns [29]. These technological improvements provide researchers with increasingly powerful tools to decipher the epigenetic code governing cell fate decisions.

Experimental Approaches for Investigating Chromatin Dynamics

Chromatin Accessibility Dynamics During Somatic Cell Reprogramming

Plant somatic embryogenesis provides an excellent model for investigating chromatin dynamics during cell fate transitions. Research demonstrates that the phytohormone auxin rapidly rewires the totipotency network by altering chromatin accessibility [34]. The experimental workflow involves:

- Induction: Treat somatic explants with auxin to initiate reprogramming

- Time-series sampling: Collect cells at critical transition points (0, 12, 24, 48 hours post-induction)

- ATAC-Seq: Perform assay for transposase-accessible chromatin using sequencing to map accessibility dynamics

- RNA-Seq: Conduct transcriptome analysis in parallel to correlate accessibility with gene expression

- Network analysis: Construct hierarchical transcriptional regulatory networks from integrated data

This approach revealed that embryonic explant competence is prerequisite for reprogramming, with the B3-type transcription factor LEC2 directly activating early embryonic patterning genes WOX2 and WOX3 to promote somatic embryo formation [34]. The methodology can be adapted to mammalian systems by replacing auxin with appropriate reprogramming factors (e.g., OSKM factors).

High-Content Nanoscopy of Epigenetic Marks

The EDICTS (Epi-mark Descriptor Imaging of Cell Transitional States) methodology enables quantitative analysis of histone modification organization at the single-cell level using super-resolution microscopy [35]. The protocol comprises:

Cell preparation and labeling:

- Fix cells and perform immunolabeling for bivalent histone marks (H3K4me3/H3K27me3)

- Use validated primary antibodies and fluorescent secondary antibodies

Super-resolution imaging:

- Acquire images using gated STED (G-STED) nanoscopy

- Achieve resolution below the diffraction limit (~30-50 nm)

Image analysis and feature extraction:

- Apply Haralick texture feature algorithms to quantify organizational patterns

- Calculate 104 unique quantitative descriptors from grey-level co-occurrence matrices (GLCMs)

- Generate organizational signatures predictive of lineage commitment

This approach successfully discriminates stem cell phenotypes based on spatial organization of bivalent domains, even when global modification levels remain constant [35]. The technique is particularly valuable for predicting lineage progression in response to biophysical cues such as substrate nanotopography and stiffness.

Pharmacological Modulation of Chromatin States

Small molecule inhibitors enable experimental manipulation of epigenetic states to establish causal relationships between chromatin modifications and cell fate outcomes:

KMT inhibition:

- Apply 3-Deazaneplanocin A (DZNep) to inhibit H3K27 methylation

- Use Deoxy-methylthioadenosine (MTA) to target H3K4 methylation

- Treat human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) with concentration gradients (0.1-10 μM) for 24-72 hours

Chromatin remodeling complex inhibition:

- Employ FHD286 or FHT2344 to inhibit BAF complex ATPase activity [31]

- Treat uveal melanoma cells with inhibitors (1-100 nM) for 48 hours

- Assess chromatin accessibility changes via ATAC-Seq and transcriptional outcomes by RNA-Seq

Validation assays:

- Perform immunocytochemistry for modified histones

- Conduct qRT-PCR for lineage-specific markers

- Assess functional differentiation potential

Pharmacological inhibition studies demonstrate that BAF complex targeting specifically reduces chromatin accessibility at promoter-distal enhancers co-occupied by SOX10, MITF, and TFAP2A transcription factors, leading to subsequent transcriptional shutdown and apoptosis in cancer models [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Chromatin and Epigenetics Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chromatin Remodeling Inhibitors | FHD286, FHT1015, FHT2344 [31] | Dual inhibition of BAF complex ATPase subunits (BRG1/BRM) | Preclinical models of uveal melanoma; induces tumor regression |

| Histone Methyltransferase Inhibitors | 3-Deazaneplanocin A (DZNep) [35] | Inhibition of H3K27 methylation | Promotes "open" chromatin state; 0.1-10 μM concentration range |

| DNA Methyltransferase Inhibitors | 5-azacytidine, decitabine [29] | Inhibition of DNMT enzymes; DNA hypomethylation | FDA-approved for MDS/AML; reprograms cell identity |

| Histone Modification Antibodies | Anti-H3K4me3, Anti-H3K27me3 [35] [29] | Immunodetection of specific histone marks | Validation via immunoelectron microscopy; essential for ChIP-Seq |

| ATP-Dependent Chromatin Assays | BRG1/BRM ATPase activity assays | Quantify remodeling complex activity | Monitor kinetic parameters (Km, Vmax) of nucleosome remodeling |

Clinical Implications and Therapeutic Applications

Dysregulation of chromatin remodeling and epigenetic mechanisms contributes significantly to human diseases, particularly cancer and developmental disorders. Somatic mutations in chromatin remodeling complex subunits occur frequently in cancers, with BAP1 loss strongly associated with metastatic uveal melanoma [31]. The TIP60 complex functions as a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor, with cancer-associated mutations identified in its EP400 ATPase domain that impair complex assembly and function [32]. Epigenetic alterations also drive cellular senescence and aging, where senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) creates a pro-inflammatory microenvironment that promotes tissue dysfunction and oncogenesis [36].

Therapeutic targeting of epigenetic regulators shows promising clinical potential. BAF complex inhibitors (FHD286, FHT2344) demonstrate efficacy in preclinical uveal melanoma models, causing dose-dependent tumor regression by selectively reducing chromatin accessibility at key transcription factor binding sites [31]. DNA methyltransferase inhibitors (5-azacytidine, decitabine) have received FDA approval for myelodysplastic syndromes and acute myeloid leukemia, validating epigenetic targeting as a viable treatment strategy [29]. Emerging approaches focus on combination therapies that simultaneously target multiple epigenetic mechanisms or pair epigenetic drugs with conventional chemotherapy, immunotherapy, or targeted agents.

In the context of aging, partial reprogramming approaches using transient expression of Yamanaka factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC) demonstrate potential to reverse age-associated epigenetic alterations without inducing tumorigenesis, effectively rejuvenating aged cells while maintaining cellular identity [36]. The interplay between cellular senescence and reprogramming represents a promising therapeutic axis, where selective elimination of senescent cells with senolytic drugs or modulation of the SASP with senomorphics may ameliorate age-related functional decline and reduce cancer incidence.

Chromatin remodeling and epigenetic modifications constitute a master regulatory system governing cell fate decisions in development, homeostasis, and disease. The integrated activities of ATP-dependent remodeling complexes and chemical modifications to DNA and histones establish accessible chromatin landscapes that determine transcriptional programs and cellular identity. In somatic cell molecular evolution, these epigenetic mechanisms enable phenotypic plasticity and adaptive responses to environmental cues without altering genomic sequences.

Future research directions will focus on deciphering the combinatorial logic of epigenetic modifications, understanding context-specific functions of chromatin remodeling complex subunits, and developing increasingly precise epigenetic editing technologies. The application of single-cell multi-omics approaches will reveal heterogeneity in epigenetic states within cell populations, while advanced imaging techniques like EDICTS will enable spatial analysis of chromatin organization in intact tissues. Artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches are being leveraged to design novel chemical modulators of epigenetic regulators, potentially yielding more specific therapeutics with reduced off-target effects [30].

As our understanding of epigenetic regulation deepens, so too does our ability to manipulate these systems for therapeutic benefit. Targeting the chromatin remodeling and epigenetic machinery holds exceptional promise for treating diverse conditions, from cancer to age-related degenerative diseases, potentially enabling precise control of cell fate decisions to achieve regenerative outcomes or suppress pathological states.

Advanced Tools and Translational Applications: From NanoSeq to Cellular Rejuvenation

The study of somatic cellular evolution is fundamentally constrained by a central technical challenge: the accurate detection of extremely rare mutations present in microscopic clones against a background of sequencing errors. As we age, our tissues become colonized by microscopic clones carrying somatic driver mutations, some of which represent initial steps toward cancer while others may contribute to ageing and various diseases [37]. However, until recently, our understanding of this phenomenon has remained severely limited because conventional next-generation sequencing (NGS) platforms exhibit systematic error rates of approximately 0.005-0.02 (0.5%-2%), making them incapable of reliably distinguishing true low-frequency somatic variants from technical artifacts, particularly for variants present at frequencies below 1% [38] [39]. This technological limitation has obstructed detailed investigation of the earliest stages of carcinogenesis and the role of somatic mutations in ageing and disease.

The emergence of ultra-accurate error-corrected sequencing methodologies represents a transformative advancement for studying somatic evolution at the molecular level. Among these techniques, nanorate sequencing (NanoSeq) has established new standards for detection sensitivity through its unique molecular approach that dramatically reduces error rates [40]. Originally introduced in 2021 by researchers at the Wellcome Sanger Institute, NanoSeq implements a duplex sequencing method with exceptional precision, enabling the detection of somatic mutations present in single DNA molecules within complex polyclonal tissue samples [41]. The subsequent refinement of this technology, particularly through the development of versions compatible with whole-exome and targeted capture, has opened unprecedented opportunities for population-scale studies of somatic mutation accumulation and clonal selection [37].

Core Technological Advancements in NanoSeq

Fundamental Principles of Error Correction

The exceptional accuracy of NanoSeq stems from its implementation of duplex sequencing principles combined with specific biochemical modifications that minimize error introduction during library preparation. In standard duplex sequencing, each original DNA molecule is tagged with a unique molecular identifier (UMI) before amplification, allowing bioinformatic consensus building to eliminate sequencing errors [38]. However, conventional duplex methods still suffer from error transfer between strands during library preparation, typically achieving error rates of around 10⁻⁷ errors per base pair [37].