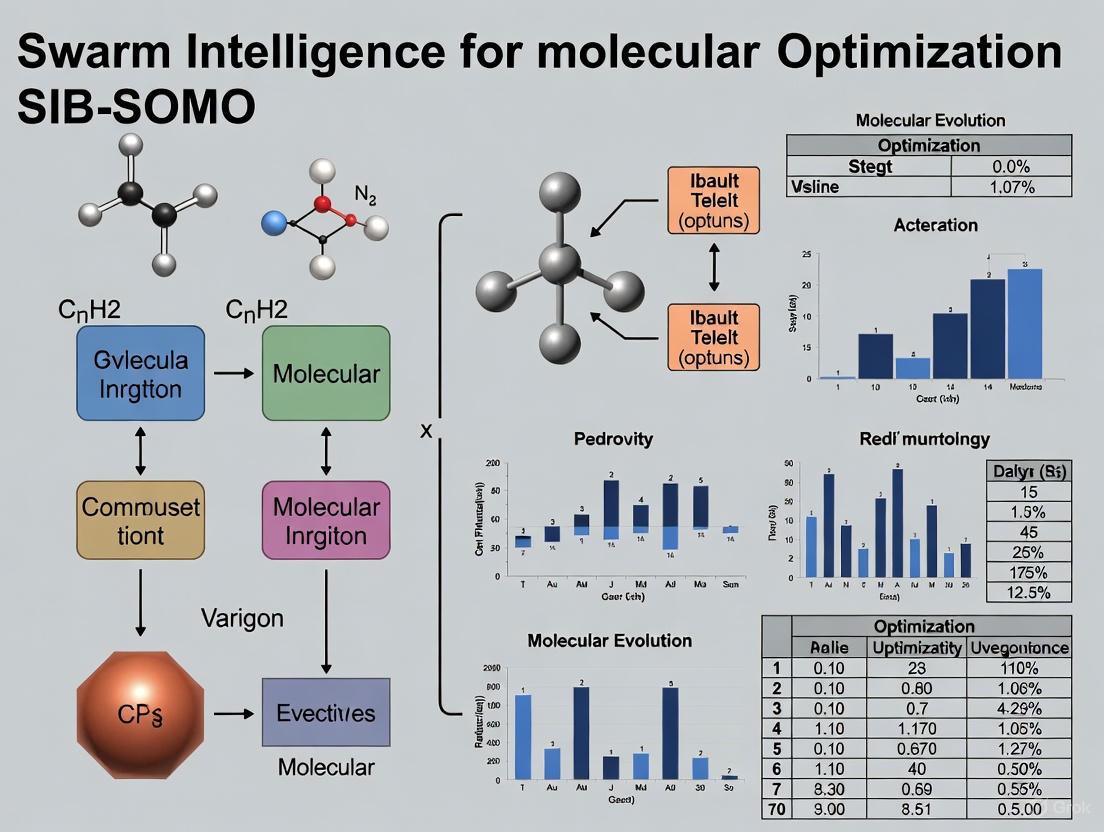

Swarm Intelligence for Molecular Optimization (SIB-SOMO): A Revolutionary Framework for Accelerating Drug Discovery

This article explores the Swarm Intelligence-Based Method for Single-Objective Molecular Optimization (SIB-SOMO), a novel evolutionary algorithm transforming computational drug design.

Swarm Intelligence for Molecular Optimization (SIB-SOMO): A Revolutionary Framework for Accelerating Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the Swarm Intelligence-Based Method for Single-Objective Molecular Optimization (SIB-SOMO), a novel evolutionary algorithm transforming computational drug design. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it details SIB-SOMO's foundational principles, which merge the exploratory power of Genetic Algorithms with the convergence efficiency of Particle Swarm Optimization to navigate the vast molecular space. The content covers its core methodology, including MIX and MOVE operations, and practical applications in optimizing key properties like drug-likeness (QED). It further addresses critical troubleshooting strategies to avoid local optima, provides a comparative analysis against state-of-the-art deep learning and evolutionary methods, and validates its performance in identifying near-optimal molecular solutions with remarkable speed. This comprehensive review synthesizes how SIB-SOMO offers a fast, efficient, and knowledge-free framework for de novo drug design and molecular optimization, poised to significantly reduce the time and cost associated with traditional pharmaceutical R&D.

The Foundation of SIB-SOMO: Principles and the Challenge of Molecular Space

Molecular optimization (MO) is a critical objective in chemical research and drug discovery, aiming to identify or design novel molecular structures with specific, desired properties. The goal is to navigate the nearly infinite molecular space to find compounds that optimize a target property, such as drug-likeness, binding affinity, or synthetic accessibility [1]. The molecular optimization problem is fundamentally the challenge of finding a molecule that maximizes or minimizes a given objective function within this vast chemical space [1].

A significant hurdle in this field is the curse of dimensionality. The molecular space is highly complex and expansive; with just 17 heavy atoms (C, N, O, S, and Halogens), there are estimated to be over 165 billion possible chemical combinations [1]. This exponential growth of possible configurations as molecular complexity increases makes exhaustive searches computationally intractable. Similar dimensionality challenges are observed in genetic research, where evaluating all possible interactions among millions of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) becomes prohibitive [2]. This curse diminishes the usefulness of traditional statistical and optimization methods, necessitating more sophisticated computational approaches [2].

The Molecular Optimization Landscape

Defining the Problem and Key Challenges

The molecular optimization problem can be formally defined as searching for a molecule ( M^* ) that satisfies:

( M^* = \arg \max_{M \in \mathcal{M}} f(M) )

where ( \mathcal{M} ) represents the chemical space and ( f ) is the objective function quantifying the desired molecular property [1]. In drug discovery, this function often incorporates the Quantitative Estimate of Druglikeness (QED), which integrates eight molecular properties into a single score ranging from 0 (undesirable) to 1 (desirable) [1].

Table 1: Molecular Properties Comprising the QED Score

| Property | Description | Role in Druglikeness |

|---|---|---|

| MW | Molecular Weight | Affects bioavailability and permeability |

| ALOGP | Octanol-water partition coefficient | Measures lipophilicity |

| HBD | Number of Hydrogen Bond Donors | Influences solubility and permeability |

| HBA | Number of Hydrogen Bond Acceptors | Affects solubility and drug-receptor interactions |

| PSA | Molecular Polar Surface Area | Predicts membrane permeability |

| ROTB | Number of Rotatable Bonds | Indicator of molecular flexibility |

| AROM | Number of Aromatic Rings | Related to planar structure and stacking interactions |

| ALERTS | Presence of undesirable substructures | Identifies potential toxicity or reactivity |

The primary challenges in molecular optimization include:

- Vast Search Space: The chemical space is practically infinite for all but the simplest molecules [1].

- Discrete Nature: Molecular representations are often discrete (e.g., graphs, SMILES strings), complicating gradient-based optimization [1].

- Expensive Evaluation: Calculating molecular properties through computational methods or experiments is often time-consuming and resource-intensive [1].

- Multi-objective Trade-offs: Optimizing for one property may compromise others, requiring balanced solutions.

The Curse of Dimensionality in Chemistry

The curse of dimensionality manifests in molecular optimization through several phenomena:

- Exponential Growth of Search Space: Each additional atom increases the number of possible configurations exponentially [1].

- Sparsity of Solutions: High-quality molecules become increasingly rare as dimensionality grows, akin to finding a needle in a haystack [2].

- Data Scarcity: In high dimensions, available data becomes sparse, making it difficult to build accurate predictive models [3].

In genetic research, a parallel challenge exists where the number of potential gene-gene interactions grows exponentially with the number of SNPs, creating similar computational bottlenecks [2].

Computational Approaches to Molecular Optimization

Traditional Methods and Limitations

Traditional optimization methods often struggle with the discrete nature of molecular space. Early approaches included systematic searches and heuristic methods, but these typically fail to scale to realistic problem sizes encountered in drug discovery [1].

Geometry optimization methods, such as those implemented in computational chemistry packages like PSI4, focus on finding minimal energy configurations of a given molecular structure but do not address the broader challenge of exploring different molecular architectures [4].

Table 2: Comparison of Molecular Optimization Approaches

| Method Category | Representative Algorithms | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Evolutionary Computation | SIB-SOMO [1], EvoMol [1], Genetic Algorithms [1] | Handles discrete spaces, requires no gradients, good for complex objectives | May require many function evaluations, can converge slowly |

| Deep Learning | MolGAN [1], JT-VAE [1], ORGAN [1] | Fast prediction once trained, can learn complex patterns | Requires large training datasets, limited extrapolation capability |

| Reinforcement Learning | MolDQN [1] | Can learn from interaction, suitable for sequential decision making | Complex implementation, sensitive to reward design |

| Bayesian Optimization | Latent-Space BO [5] | Sample-efficient, handles uncertainty | Struggles with high dimensions, Gaussian process scalability |

Swarm Intelligence for Molecular Optimization

Swarm intelligence algorithms, inspired by collective behavior in nature, have shown promise in addressing molecular optimization problems. The Swarm Intelligence-Based Method for Single-Objective Molecular Optimization (SIB-SOMO) adapts the general framework of swarm intelligence to molecular design [1].

The SIB algorithm combines the discrete domain capabilities of Genetic Algorithms with the convergence efficiency of Particle Swarm Optimization [1]. It maintains a swarm of particles (molecules) and iteratively improves them through:

- MIX Operations: Combining particles with local and global best solutions [1]

- MUTATION Operations: Modifying molecular structure through atom or bond changes [1]

- MOVE Operations: Selecting the best candidate for the next iteration [1]

- Random Jump: Preventing premature convergence to local optima [1]

SIB-SOMO Algorithm Workflow

SIB-SOMO: Protocol and Application

Experimental Protocol for Molecular Optimization

Protocol Title: Implementation of SIB-SOMO for Druglikeness Optimization Objective: To optimize the Quantitative Estimate of Druglikeness (QED) of molecular structures using swarm intelligence.

Materials and Computational Environment:

- Software Requirements: Python environment with RDKit and necessary cheminformatics libraries

- Hardware: Standard computational workstation (multi-core processor recommended)

- Initialization: Carbon chain with maximum length of 12 atoms [1]

Procedure:

Swarm Initialization

- Generate initial population of molecules (swarm particles)

- Set parameters: swarm size, maximum iterations, convergence threshold

- Define objective function (e.g., QED score)

Iterative Optimization Loop (repeat until convergence) a. MIX Operation

- For each particle, combine with its Local Best (LB) and Global Best (GB)

- Generate two modified particles: mixwLB and mixwGB

- Use different modification proportions for LB (larger) and GB (smaller) to prevent premature convergence [1]

b. MUTATION Operation

- Apply structural modifications to explore chemical space:

c. MOVE Operation

- Evaluate objective function for original particle, mixwLB, and mixwGB

- Select the best-performing candidate as new position

- Update Local Best and Global Best records

d. Random Jump Operation (conditional)

- If original particle remains best after MOVE, apply Random Jump

- Randomly alter portion of particle's entries to escape local optima [1]

Convergence Check

- Evaluate if stopping criteria are met:

- Maximum iterations reached

- Global Best improvement below threshold

- Computational time limit exceeded

- Evaluate if stopping criteria are met:

Result Extraction

- Return Global Best molecule and its property values

- Analyze molecular features contributing to optimal score

Expected Outcomes:

- Identification of molecules with improved QED scores

- Demonstration of efficient exploration of chemical space

- Comparison with baseline methods (e.g., EvoMol, MolGAN) showing competitive performance [1]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Molecular Optimization

| Tool/Category | Function | Application in SIB-SOMO |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Cheminformatics library | Molecular representation, manipulation, and property calculation |

| PSI4 | Quantum chemistry package | High-fidelity property evaluation (when needed) [4] |

| Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) | Dimensionality reduction | Latent space representation for high-dimensional optimization [5] |

| PySpark | Distributed computing framework | Handling large-scale genetic or molecular data [2] |

| DIIS Algorithm | Convergence acceleration | Speeding up self-consistent field calculations in quantum methods [6] |

The molecular optimization problem, compounded by the curse of dimensionality, represents a significant challenge in computational chemistry and drug discovery. The SIB-SOMO approach demonstrates how swarm intelligence algorithms can effectively navigate high-dimensional chemical spaces to identify promising molecular structures with desired properties. By combining the exploration capabilities of evolutionary methods with efficient convergence patterns of swarm intelligence, SIB-SOMO offers a powerful framework for molecular optimization that complements existing deep learning and traditional approaches. As computational resources grow and algorithms become more sophisticated, swarm intelligence methods are poised to play an increasingly important role in accelerating molecular discovery and design.

The Limitations of Traditional Drug Discovery and High-Throughput Screening

The journey of drug discovery is a cornerstone of pharmaceutical science, traditionally relying on iterative molecular design and extensive high-throughput screening (HTS) campaigns. These methods have historically been responsible for the development of therapeutic agents. However, this traditional paradigm faces significant challenges in the modern research landscape, including inefficiency, high costs, and difficulties in navigating complex chemical spaces. The process of molecular optimization—making structural modifications to improve desired properties of drug candidates—is particularly crucial, yet most conventional algorithms pay insufficient attention to the synthesizability of proposed molecules, resulting in optimized compounds that are difficult or impractical to synthesize in the laboratory [7]. Within this context, the Swarm Intelligence for Biomolecular SOMO (SIB-SOMO) research framework emerges as a transformative approach. By leveraging nature-inspired swarm intelligence algorithms, SIB-SOMO aims to overcome the inherent limitations of traditional methods, enabling more efficient, cost-effective, and synthetically feasible exploration of chemical space for drug development.

Quantitative Limitations of Traditional Workflows

Traditional drug discovery approaches, particularly High-Throughput Screening (HTS), are often characterized by their resource-intensive nature. The following table summarizes key limitations as evidenced by contemporary research, providing a quantitative perspective on these challenges.

Table 1: Documented Limitations of Traditional Drug Discovery and HTS Approaches

| Limitation Category | Reported Impact/Performance | Context from Research |

|---|---|---|

| Synthesizability Consideration | Insufficient in most DL-based algorithms [7] | Leads to optimized compounds that are challenging to synthesize physically. |

| Optimization Workflow | Separation of optimization from synthesis planning [7] | Post-filtering for synthesizability is less ideal for molecular optimization workflows. |

| Template Coverage in Template-Based Methods | Limited template coverage challenges [7] | Reaction templates may not include functional templates tailored for specific properties. |

| Multi-Objective Optimization | Limited ability to explore trade-offs [7] | Amalgamating goals into a composite function limits trade-off exploration. |

The challenges extend beyond the wet-lab experiments of HTS to in silico methods. Conventional data analysis techniques in drug discovery often begin with creating mathematical models, an approach that can prove inadequate as the diversity of real-time data expands. The current paradigm needs to transition from being model-driven to being data-driven [8]. Furthermore, the effectiveness of problem-solving is largely dependent on the quality and quantity of available data. As more data are acquired, the underlying problem structure becomes clearer, enabling more precise analysis. However, traditional decision-making procedures based on small datasets can introduce biases or lead to improbable coincidences, producing inaccurate or biased analytical findings [8].

The SIB-SOMO Protocol: A Swarm Intelligence-Enhanced Framework

The SIB-SOMO framework integrates Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and its advanced variants to address the documented shortcomings of traditional methods. The core protocol involves a cyclic process of swarm-guided candidate generation, in silico evaluation, and iterative model refinement.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Step 1: Problem Definition and Search Space Configuration

- Objective Function Formulation: Define the multi-objective optimization function incorporating target properties (e.g., bioactivity, CYP inhibition, mutagenicity) and a synthesizability score.

- Chemical Space Parameterization: Represent the molecular search space as a high-dimensional landscape where parameters can include structural fragments, physicochemical descriptors, and potential reaction pathways.

- SIB-SOMO Initialization: Initialize a swarm of particles, where each particle represents a potential candidate molecule or a set of reaction conditions. The initial swarm is generated using quasi-random Sobol sampling to ensure a well-distributed starting point across the chemical space [9].

Step 2: Swarm Intelligence-Guided Exploration

- Particle Movement and Update: Each particle in the swarm navigates the chemical landscape based on its own experience (

pbest), the swarm's collective knowledge (gbest), and a machine learning-guided acquisition function. The position update rules are governed by weighting parameters (c_local,c_social,c_ml), which provide intuitive control over the search dynamics [9]. - Candidate Suggestion: The collective movement of the particle swarm generates a new batch of candidate molecules or reaction conditions for evaluation.

Step 3: Parallel Evaluation and Data Acquisition

- In Silico Profiling: Utilize high-performance computing clusters to parallelly evaluate the suggested candidate batch. Employ predictive QSAR/QSPR models for properties like logP, solubility, and toxicity.

- Synthesizability Assessment: Integrate with a Computer-Assisted Synthesis Planning (CASP) tool to score the feasibility of synthesizing each candidate and propose potential synthetic routes [7].

- High-Throughput Experimental Validation (Optional but Recommended): Where resources permit, synthesize and test the top-performing candidates using robotic HTE platforms. This generates high-quality experimental data for model refinement [9].

Step 4: Model and Swarm Memory Update

- Update Particle Memory: For each particle, update its personal best (

pbest) and the swarm's global best (gbest) based on the evaluation results from Step 3. - Reinforcement Learning Update: If applicable, update the neural networks governing the reaction action, reactant selection, and reaction template based on the success or failure of the proposed candidates and their synthetic pathways [7].

- Strategic Reinitialization: Use ML predictions to guide the reinitialization of particles trapped in local optima, redirecting the swarm to more promising regions of the chemical space [9].

Step 5: Iteration and Convergence Repeat Steps 2-4 for a predefined number of iterations or until performance convergence is achieved. The final output is a set of optimized, synthetically feasible lead compounds.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated SIB-SOMO protocol, highlighting the closed-loop feedback between AI-guided search and experimental validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Successful implementation of the SIB-SOMO framework relies on a suite of computational and experimental tools. The table below details the key resources required.

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Solutions for SIB-SOMO Research

| Item Name | Function/Application | Specification Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) Platform | Enables highly parallel synthesis and testing of reaction conditions suggested by the swarm algorithm at miniaturized scales [9]. | Robotic platforms capable of handling nanomole to micromole scales for rapid, data-rich experimentation. |

| Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) Core | The primary metaheuristic engine that coordinates the search for optimal molecules or conditions through swarm dynamics [9]. | Augmented with ML guidance (α-PSO). Key parameters: cognitive (c_local), social (c_social), and ML (c_ml) weights [9]. |

| Functional Reaction Template Library | A collection of data-derived chemical transformation rules that guide molecular modifications toward improved properties and synthesizability [7]. | Constructed using explanation methods (e.g., SME) on molecular datasets to identify property-relevant substructures and transformations [7]. |

| Synthesis Planning (CASP) Software | Evaluates the synthetic feasibility of AI-proposed molecules and suggests retrosynthetic pathways, integrating synthesizability directly into the optimization loop [7]. | Uses reaction templates derived from databases like USPTO. Tools include RDChiral for template application [7]. |

| Multi-Objective Property Predictor | In silico models that predict key drug properties (e.g., activity, toxicity, metabolism) for rapid candidate triage before experimental validation [7]. | Built using machine learning (e.g., RGCN) on high-quality molecular datasets. Essential for defining the optimization landscape [7]. |

The limitations of traditional drug discovery and High-Throughput Screening are profound, spanning inefficiencies in resource allocation, a frequent disconnect between molecular design and synthetic practicality, and challenges in navigating multi-objective optimization landscapes. The SIB-SOMO research framework directly confronts these issues by harnessing the power of swarm intelligence. It creates an iterative, closed-loop system that intelligently explores the vast chemical space, balances multiple critical properties, and prioritizes synthesizability from the outset. This paradigm shift, moving from disjointed sequential processes to an integrated, intelligent, and adaptive workflow, holds the significant potential to accelerate the discovery of viable drug candidates and enhance the overall efficiency of pharmaceutical research and development.

In the field of artificial intelligence and computational optimization, two distinct paradigms have demonstrated significant promise: Evolutionary Computation (EC) and Deep Learning (DL). While deep learning has gained substantial popularity in data-rich domains, evolutionary computation offers unique advantages in problem domains with unknown optimal solutions or complex, non-differentiable search spaces [10]. Understanding the complementary strengths and limitations of these approaches is crucial for researchers, particularly in scientific domains such as drug discovery and molecular optimization.

Evolutionary computation encompasses a family of population-based optimization algorithms inspired by biological evolution, including Genetic Algorithms (GA), Genetic Programming (GP), and swarm intelligence methods like Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and the Swarm Intelligence-Based (SIB) algorithm [11]. These methods operate through iterative processes of selection, variation, and reproduction, maintaining a population of candidate solutions that evolve toward improved fitness over generations [12]. Unlike gradient-based methods, EC does not require differentiable objective functions and can effectively explore complex, multi-modal search spaces.

Deep learning, a subset of machine learning, utilizes multi-layer neural networks to learn hierarchical representations from data [13]. DL has demonstrated remarkable success in domains with large amounts of labeled data, such as image recognition, natural language processing, and speech recognition [10]. Through backpropagation and gradient descent, DL models adjust their parameters to minimize prediction error, enabling them to capture complex patterns and relationships within data.

Theoretical Framework and Comparative Analysis

Core Methodological Differences

The fundamental distinction between evolutionary computation and deep learning lies in their underlying principles and search mechanisms. EC employs a population-based stochastic search inspired by natural selection, where solutions evolve through operations such as mutation, crossover, and selection [12]. This approach enables global exploration of complex solution spaces without relying on gradient information. In contrast, DL utilizes a gradient-based optimization process that adjusts model parameters through backpropagation, requiring differentiable loss functions and network architectures [13].

This methodological divergence leads to different strengths and limitations for each approach. EC excels in problems where the optimal solution is unknown or difficult to define, such as game playing, robotics tasks, decision-making, and practical applications in healthcare treatment or stock market investment [10]. DL achieves superior performance in data-driven domains with well-defined input-output mappings and abundant labeled examples, leveraging its capacity to learn hierarchical features directly from data [10].

Comparative Analysis of Key Characteristics

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Evolutionary Computation and Deep Learning

| Feature | Evolutionary Computation | Deep Learning |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Population-based evolution through selection, mutation, and recombination | Gradient-based optimization through backpropagation in multi-layer neural networks |

| Search Mechanism | Stochastic global search | Deterministic local search guided by gradients |

| Data Dependencies | Does not require labeled data; operates on fitness evaluations | Requires large amounts of labeled training data |

| Solution Representation | Flexible representations (vectors, trees, graphs) | Typically fixed neural network architectures |

| Optimal Solution Nature | Effective for problems with unknown or ambiguous optimal solutions | Effective for problems with clear input-output mappings |

| Strengths | Global exploration, handles non-differentiable problems, interpretable evolution paths | Pattern recognition, hierarchical feature learning, state-of-the-art performance on perceptual tasks |

| Limitations | May have convergence issues, requires careful fitness function design | High computational cost, potential for overfitting, limited interpretability |

Application to Molecular Optimization

The Molecular Optimization Challenge

Molecular optimization represents a significant challenge in chemical research and drug discovery, aiming to identify molecules with specific features for targeted applications [1]. The molecular space is highly complex and nearly infinite, with an estimated 165 billion chemical combinations possible with just 17 heavy atoms (C, N, O, S, and Halogens) [1]. Traditional drug discovery involves searching through natural and synthetic chemicals, a process that is both costly and time-consuming, often taking decades and exceeding one billion dollars [1].

Computer-Aided Drug Design (CADD) has emerged as a crucial approach to accelerate this process, with de novo drug design creating molecular compounds from scratch for more thorough exploration of chemical space [14]. Within this context, both evolutionary computation and deep learning have demonstrated significant potential for molecular optimization tasks, albeit through different methodological approaches.

Evolutionary Computation in Molecular Optimization

Evolutionary computation approaches to molecular optimization typically represent molecules as graphs or fingerprint vectors that evolve through iterative application of evolutionary operators [15]. The Swarm Intelligence-Based Method for Single-Objective Molecular Optimization (SIB-SOMO) exemplifies this approach, combining the discrete domain capabilities of Genetic Algorithms with the convergence efficiency of Particle Swarm Optimization [14].

In SIB-SOMO, each particle represents a molecule within the swarm, initially configured as a carbon chain with a maximum length of 12 atoms [14]. During each iteration, every particle undergoes MUTATION and MIX operations, generating modified particles. The MOVE operation then selects the best particle based on the objective function, with Random Jump or Vary operations enhancing exploration under specific conditions [14]. This approach identifies near-optimal solutions in remarkably short timeframes without requiring chemical knowledge, though incorporating domain knowledge could potentially reduce the search space [14].

EvoMol represents another evolutionary approach for de novo molecular generation, implementing a hill-climbing algorithm combined with chemically meaningful mutations [15]. The algorithm sequentially builds molecular graphs using an original set of 7 generic mutations close to the atomic level, achieving excellent performances on standard molecular properties including QED (Quantitative Estimate of Druglikeness), penalised logP, SAscore, and CLscore [15].

Deep Learning in Molecular Optimization

Deep learning approaches to molecular optimization typically employ generative models that learn from existing chemical databases to propose novel molecular structures [16]. These include Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), and recurrent neural networks (RNNs) that generate molecular representations such as SMILES strings or molecular graphs [14].

MolGAN combines Generative Adversarial Networks with a reinforcement learning objective to produce small molecular graphs with desired properties [14]. Compared to SMILES-based sequential GAN models, MolGAN achieves higher chemical property scores and faster training times, though it is susceptible to mode collapse, which can limit output variability [14].

The Junction Tree Variational Autoencoder (JT-VAE) is a deep generative model that maps molecules to a high-dimensional latent space, using sampling or optimization techniques to generate new molecules [14]. This approach enables continuous representation of molecular structures, facilitating optimization through interpolation in the latent space.

Objective-Reinforced Generative Adversarial Networks (ORGAN) leverage reinforcement learning to generate molecules from SMILES strings [14]. While this adversarial approach helps in producing diverse samples, it does not guarantee the validity of the generated molecules, and GAN models tend to generate sequences with an average length similar to that of the training set, which can limit diversity [14].

Hybrid Approaches

Recent research has explored hybrid approaches that combine evolutionary computation with deep learning for molecular optimization [16]. One method employs deep learning models to extract inherent knowledge from material databases, guiding evolutionary design through a genetic algorithm that evolves the Morgan fingerprint vectors of seed molecules [16]. A recurrent neural network then reconstructs the final fingerprints into actual molecular structures while maintaining chemical validity [16].

This hybrid approach addresses key challenges in evolutionary design, particularly maintaining chemical validity during evolution and enabling efficient evaluation of evolved molecules through deep neural network models that predict molecular properties [16]. The method has demonstrated effectiveness in design tasks modifying light-absorbing wavelengths of organic molecules from the PubChem library [16].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

SIB-SOMO Protocol for Molecular Optimization

The Swarm Intelligence-Based Method for Single-Objective Molecular Optimization (SIB-SOMO) provides a robust protocol for molecular optimization problems. The following detailed methodology outlines the implementation process:

Initialization Phase:

- Swarm Initialization: Initialize a swarm of particles, where each particle represents a molecule. Begin with carbon chains of maximum length 12 atoms [14].

- Parameter Configuration: Set algorithm parameters including population size (typically 50-100 particles), maximum iterations (100-500), and mutation rates.

- Objective Function Definition: Define the molecular optimization objective, such as maximizing QED (Quantitative Estimate of Druglikeness) or minimizing synthetic accessibility score.

Iterative Optimization Phase:

- Fitness Evaluation: Calculate fitness scores for all particles using the objective function. For QED optimization, compute scores based on eight molecular properties: molecular weight (MW), octanol-water partition coefficient (ALOGP), number of hydrogen bond donors (HBD), number of hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA), molecular polar surface area (PSA), number of rotatable bonds (ROTB), and number of aromatic rings (AROM) [14].

- MIX Operation: For each particle, perform MIX operations with its Local Best (LB) and Global Best (GB) particles. Modify a proportion of entries (typically 10-30% for LB, 5-15% for GB) based on corresponding values from best particles [14].

- MUTATION Operation: Apply two distinct mutation operations:

- Mutateatom: Randomly alter atom types within the molecular structure.

- Mutatebond: Modify bond types between atoms [1].

- MOVE Operation: Select the best particle from the original, mixwLB, and mixwGB particles based on fitness. If the original particle remains best, apply Random Jump operation to 5-15% of its entries [14].

- Termination Check: Evaluate stopping criteria (maximum iterations, convergence threshold, or computation time). If not met, return to step 4.

Post-processing Phase:

- Solution Extraction: Select the GB particle as the optimized molecular solution.

- Validation: Validate chemical validity and properties of optimized molecules using chemical informatics tools such as RDKit.

Deep Learning Protocol for Molecular Generation

This protocol outlines the implementation of a deep learning approach for molecular generation using recurrent neural networks and evolutionary guidance, as described in scientific literature [16]:

Data Preparation Phase:

- Dataset Curation: Collect and curate molecular dataset from sources such as PubChem or ChEMBL. Ensure diversity and relevance to target application.

- Molecular Representation: Convert molecular structures to SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) strings or extended-connectivity fingerprint (ECFP) vectors with a length of 5000 and neighborhood size of 6 [16].

- Data Partitioning: Split dataset into training (70-80%), validation (10-15%), and test (10-15%) sets using stratified sampling to maintain property distributions.

Model Training Phase:

- Network Architecture: Implement a recurrent neural network with three hidden layers containing 500 long short-term memory units for sequence generation [16].

- Training Configuration: Use Adam optimizer with mini-batch size of 100 and 500 training epochs. Apply dropout layers with rate of 0.5 after each input and hidden layer to prevent overfitting [16].

- Language Modeling: Train the RNN as a language model that generates single-step moving window sequences of three-character substrings for each SMILES string, conditioning on current substring and given ECFP vector [16].

Evolutionary Optimization Phase:

- Population Initialization: Transform seed molecule SMILES to ECFP vector using encoding function. Generate initial population through mutation of initial vector [16].

- Fitness Evaluation: Decode each vector to SMILES string using RNN decoder. Inspect grammatical validity using RDKit library. Predict molecular properties using deep neural network with five layers and 250 hidden units per layer [16].

- Evolutionary Operations: Select top three ECFP vectors based on fitness as parents for further evolution through crossover and mutation.

- Iterative Refinement: Repeat evaluation and evolution for multiple generations (typically 50-200) until target properties are achieved.

Validation Phase:

- Chemical Validation: Verify chemical validity, synthetic accessibility, and novelty of generated molecules.

- Experimental Prioritization: Rank optimized molecules based on multiple criteria including target properties, drug-likeness, and structural constraints.

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Essential Research Reagents and Software Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Molecular Optimization

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | Chemical validity inspection, molecular manipulation | Open-source toolkit for cheminformatics; used for sanity testing and molecular operations in both EC and DL approaches [15] |

| ECFP Vector | Molecular Descriptor | Fixed-length molecular representation | 5000-dimensional circular fingerprint encoding structural features; used as input for DL models and evolutionary representations [16] |

| QED | Objective Function | Quantitative Estimate of Druglikeness | Composite metric integrating 8 molecular properties; commonly used as fitness function in molecular optimization [14] |

| SMILES | Molecular Representation | String-based molecular encoding | Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System; text representation for DL-based molecular generation [16] |

| PyGAD | Evolutionary Framework | Genetic algorithm implementation | Python library for evolutionary computation; enables rapid prototyping of EC approaches [17] |

| EvoMol | Evolutionary Algorithm | De novo molecular generation | Interpretable EA for molecular graphs using atomic-level mutations; benchmark for molecular optimization tasks [15] |

| JT-VAE | Deep Learning Model | Molecular generation and optimization | Junction Tree Variational Autoencoder; maps molecules to continuous latent space for optimization [14] |

| MolGAN | Deep Learning Model | Graph-based molecular generation | Generative Adversarial Network for molecular graphs with reinforcement learning objective [14] |

Evolutionary computation and deep learning offer complementary approaches to molecular optimization, with distinct strengths and limitations. EC methods like SIB-SOMO provide robust global optimization capabilities without requiring gradient information or large training datasets, making them particularly valuable for exploring novel chemical spaces and optimizing complex objective functions [14]. DL approaches leverage pattern recognition and hierarchical feature learning to generate molecules informed by existing chemical knowledge, achieving strong performance when sufficient training data is available [16].

The emerging trend of hybrid approaches, combining evolutionary search with deep learning guidance, represents a promising direction for molecular optimization research [16]. These methods leverage EC for global exploration while using DL models to maintain chemical validity and predict molecular properties, potentially overcoming limitations of either approach in isolation. As computational resources advance and algorithms mature, such integrated frameworks are likely to play an increasingly important role in accelerating drug discovery and materials design.

For researchers implementing these approaches, careful consideration of problem constraints, data availability, and objective function complexity should guide selection between evolutionary, deep learning, or hybrid methodologies. The protocols and resources outlined in this document provide a foundation for developing and applying these computational approaches to molecular optimization challenges.

Swarm Intelligence (SI) is a class of nature-inspired metaheuristic optimization algorithms derived from the collective, intelligent behavior of decentralized and self-organized biological systems. Examples of such systems include bird flocking, ant colonies, and fish schooling. A major class of metaheuristics, SI is characterized by its use of a population of simple agents interacting locally with one another and their environment to produce robust, complex global patterns and problem-solving capabilities [18]. In computational optimization, SI algorithms are powerful tools for solving complex problems that are challenging to address within a reasonable time using traditional methods.

The Swarm Intelligence-Based (SIB) framework is a specific algorithmic approach that falls under the broader SI umbrella. Originally developed for optimizing experimental designs with discrete domains, it synergistically combines the discrete domain capabilities of Genetic Algorithms (GA) with the convergence efficiency of Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) [1] [19]. Unlike standard PSO, which uses velocity-based updates and is often limited to continuous domains, the SIB framework introduces novel operations—MIX and MOVE—for combining particles and selecting the best candidate solutions [19]. This makes it particularly well-suited for high-dimensional optimization problems in both discrete and continuous domains, ranging from the search for optimal statistical designs to the discovery of new molecular structures in drug development [18] [1].

Core Operations of the SIB Algorithm

The SIB algorithm operates through a sequence of structured steps and operations that govern how candidate solutions, known as particles, explore and exploit the search space. The canonical framework is initialized with a set of particles, each evaluated by an objective function. Each particle has its Local Best (LB), and the best particle among all is designated the Global Best (GB) [1] [20]. The algorithm then iteratively refines these solutions.

The core operations that define the SIB methodology are as follows:

MIX Operation: This is an exchange procedure between the current particle and the best particles (its LB and the GB). A predefined number of components (

q_LBfrom the LB andq_GBfrom the GB, whereq_GB < q_LBto prevent premature convergence) are selected from the best particles and added to the current particle. An equal number of components are then deleted from the current particle, resulting in two new candidate particles:mixwLBandmixwGB[18] [19]. This operation facilitates knowledge transfer from high-quality solutions.MOVE Operation: Following the MIX operation, the objective function values of the original particle,

mixwLB, andmixwGBare compared. The particle with the best objective function value becomes the new current particle. This operation ensures that the swarm monotonically moves towards better solutions [19].VARY Operation (in SIB 2.0): To handle problems where the optimal size of a solution is unknown, an enhanced framework, SIB 2.0, introduces the VARY operation. If the MOVE operation does not yield an update, VARY is performed. It generates two new particles from the current one: one via unit shortening (reducing the number of components) and another via unit expansion (adding components). Another MOVE operation then decides whether to update the current particle to one of these new size-variant particles [18].

Random Jump: If neither the MIX nor VARY operations lead to an improvement, a Random Jump is performed. This operation randomly alters a portion of the particle's entries, serving as a mechanism to escape local optima and enhance the exploration of the search space [1] [20].

A key evolution of the framework is the distinction between SIB 1.0 and SIB 2.0. SIB 1.0, the standard framework, uses a fixed, pre-defined particle size. In contrast, SIB 2.0 allows the particle size to change dynamically during the search via the VARY operation, which is crucial for problems like molecular optimization where the ideal complexity of a solution is not known a priori [18]. A powerful hybrid approach is the two-step SIB method, which first uses SIB 2.0 to determine the optimal particle size and then applies SIB 1.0 at that specific size to efficiently find the optimal solution, combining the strengths of both versions [18].

Table: Core Operations in the SIB Framework

| Operation | Function | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| MIX | Exchanges components between the current particle and the LB/GB to create new candidates. | q_LB, q_GB (number of components exchanged) |

| MOVE | Selects the next position of a particle by comparing the performance of its current and newly generated forms. | Objective function value |

| VARY | Alters the size of a particle by generating shortened and expanded variants. | Unit change size |

| Random Jump | Randomly mutates a particle to escape local optima and foster exploration. | Proportion of entries to alter |

Application in Molecular Optimization: SIB-SOMO

The principles of the SIB framework have been successfully adapted to address the formidable challenges of molecular optimization (MO) in drug discovery. The chemical space is vast and complex, making an exhaustive search for molecules with specific properties impractical. The Swarm Intelligence-Based Method for Single-Objective Molecular Optimization (SIB-SOMO) is a novel evolutionary algorithm designed for this domain [1] [20].

SIB-SOMO reframes the MO problem by having each particle in the swarm represent a potential molecule. The goal is to optimize a specific objective function, such as the Quantitative Estimate of Druglikeness (QED), which is a composite measure integrating eight key molecular properties into a single score between 0 (undesirable) and 1 (desirable) [1] [20]. The properties considered in QED are detailed in the table below.

Table: Molecular Properties in the QED Objective Function

| Property | Description | Role in Druglikeness |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight (MW) | Total mass of the molecule. | Impacts bioavailability and membrane permeability. |

| ALOGP | Octanol-water partition coefficient. | Measures lipophilicity, critical for absorption. |

| HBD | Number of Hydrogen Bond Donors. | Influences solubility and binding interactions. |

| HBA | Number of Hydrogen Bond Acceptors. | Affects solubility and pharmacokinetics. |

| PSA | Polar Surface Area. | Predicts cell permeability and absorption. |

| ROTB | Number of Rotatable Bonds. | Indicator of molecular flexibility. |

| AROM | Number of Aromatic Rings. | Affects stability and binding affinity. |

| ALERTS | Presence of problematic substructures. | Flags potential toxicity or reactivity. |

The SIB-SOMO Experimental Protocol

The following protocol details the methodology for applying SIB-SOMO to a single-objective molecular optimization problem, such as maximizing a molecule's QED score.

1. Problem Formulation and Parameter Initialization

- Define the Objective Function: Clearly specify the goal of the optimization. For a standard druglikeness task, the objective function is the QED score, calculated using established parameters [1] [20]. The objective is to maximize this value.

- Set SIB-SOMO Parameters: Define the key algorithmic parameters before execution:

- Swarm Size (N): The number of particles (molecules) in the swarm.

- Maximum Iterations (L): The stopping criterion for the algorithm.

- Exchange Parameters (

q_LB,q_GB): The number of components to exchange with the Local Best and Global Best particles during the MIX operation. - Mutation Rates: The probability of performing atom or bond mutations.

2. Swarm Initialization

- Initialize the swarm by generating N particles. Each particle is a molecular graph. A simple and effective initialization strategy is to start with linear carbon chains of a defined maximum length (e.g., 12 atoms) to provide a uniform starting point [1] [20].

3. Iterative Optimization Loop For each iteration until the maximum number of iterations (L) is reached, perform the following steps for every particle in the swarm:

- Step 3.1: Mutation Operations. Generate new candidate molecules by applying two distinct chemical mutation operations to the current particle:

- Step 3.2: MIX Operations. Perform the canonical SIB MIX operation with the particle's LB and GB. In the molecular context, this involves exchanging molecular substructures or components with the best-performing particles to create two new candidate molecules:

mixwLBandmixwGB. - Step 3.3: MOVE Operation. Evaluate the objective function (e.g., QED score) for the four new candidates generated (two from Mutation and two from MIX) along with the current particle. Select the candidate with the best score to become the particle's new position for the next iteration.

- Step 3.4: Exploration Enhancement. If the current particle was not improved upon in the MOVE operation (i.e., it remains the best), trigger either a Random Jump (extensive random modification) or a VARY operation (to change molecular size) to help escape local optima.

- Step 3.5: Update LB and GB. After processing all particles, update each particle's Local Best (LB) and the swarm's Global Best (GB) if better solutions have been found.

4. Result Output

- Once the stopping criterion is met, the algorithm terminates. The Global Best (GB) particle—the molecule with the highest encountered QED score—is reported as the optimal solution [1] [20].

Comparative Performance and Key Reagents

SIB-SOMO has demonstrated significant efficacy in molecular optimization tasks. Its performance is characterized by a fast convergence to near-optimal solutions, a trait inherited from the general SIB framework's efficient use of the Global Best to guide the swarm [1]. When compared to other state-of-the-art methods, SIB-SOMO shows strong competitiveness.

For instance, against deep learning models like MolGAN (a generative adversarial network) and JT-VAE (a variational autoencoder), SIB-SOMO's evolutionary approach offers advantages. It is free from pre-training data requirements, reducing bias from existing chemical databases, and is less susceptible to issues like mode collapse, which can plague GAN models [1] [20]. Compared to other evolutionary algorithms like EvoMol, which relies on a hill-climbing strategy, SIB-SOMO's swarm-based mechanism typically achieves higher optimization efficiency, especially in expansive chemical domains [1].

The following table outlines key computational and conceptual "reagents" essential for conducting SIB-SOMO experiments.

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for SIB-SOMO Experiments

| Item | Function/Description | Role in the SIB-SOMO Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Objective Function (e.g., QED) | A mathematical function that quantifies the "goodness" of a molecule. | The primary guide for the optimization process; particles are evolved to maximize this function. |

| Molecular Graph Representation | A data structure where atoms are nodes and bonds are edges. | The internal encoding of a "particle" within the algorithm, enabling graph operations. |

| Mutation Operators (Mutateatom, Mutatebond) | Predefined rules for altering atom types and bond orders in a molecular graph. | Introduce stochastic changes to particles, fostering exploration of the chemical space. |

| MIX Operation Subroutine | The algorithm that exchanges components between molecular graphs. | Facilitates the exploitation of promising substructures found in the LB and GB molecules. |

| Chemical Validation Tool | Software or rules to check molecular validity (e.g., correct valences). | Ensures that newly generated candidate molecules are chemically plausible after operations. |

The Swarm Intelligence-Based Method for Single-Objective Molecular Optimization (SIB-SOMO) represents a significant advancement in de novo drug design, offering distinct advantages in computational efficiency, implementation simplicity, and domain-agnostic optimization. This protocol details the methodology and application of SIB-SOMO, which adapts the general Swarm Intelligence-Based (SIB) framework to efficiently navigate the vast molecular space without requiring pre-existing chemical knowledge or databases. By combining the convergence efficiency of Particle Swarm Optimization with the discrete domain capabilities of Genetic Algorithms, SIB-SOMO identifies near-optimal molecular structures in remarkably short timeframes compared to state-of-the-art alternatives. These application notes provide researchers with comprehensive experimental protocols, performance benchmarks, and practical implementation guidelines to leverage SIB-SOMO for molecular optimization problems in drug discovery and development.

Molecular optimization (MO) presents a formidable challenge in computational drug design due to the nearly infinite nature of molecular space. With an estimated 165 billion possible chemical combinations involving just 17 heavy atoms, traditional drug discovery methods prove both costly and time-consuming, often requiring decades and exceeding one billion dollars [1] [14]. Computer-Aided Drug Design (CADD) has emerged as a transformative approach, leading to commercialized drugs like Captopril and Oseltamivir while reducing the number of compounds needing synthesis and evaluation [14].

De novo drug design, a CADD technique that creates molecular compounds from scratch, enables thorough exploration of chemical space without reliance on existing chemical databases [1]. Within this domain, SIB-SOMO introduces a novel evolutionary algorithm that addresses key limitations of both traditional Evolutionary Computation (EC) methods and modern Deep Learning (DL) approaches. While machine learning techniques often depend on analyzing large chemical databases—limiting their discoveries to existing chemical space—SIB-SOMO operates without such constraints, enabling genuine exploration of novel molecular structures [1] [14].

Table 1: Comparison of Molecular Optimization Approaches

| Method Category | Representative Algorithms | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Evolutionary Computation | EvoMol, Genetic Algorithms | Effective across various optimization problems; handles discrete spaces | Optimization efficiency limited in expansive domains |

| Deep Learning | MolGAN, JT-VAE, ORGAN, MolDQN | Powerful pattern recognition; rapid sampling after training | Dependent on training database quality and scope; mode collapse issues |

| Swarm Intelligence | SIB-SOMO | Rapid exploration; no chemical knowledge required; easy implementation | Does not guarantee global optimum |

Theoretical Framework and Algorithm Design

Foundation in Swarm Intelligence

SIB-SOMO builds upon the canonical Swarm Intelligence-Based (SIB) method, which originally optimized experimental designs [11]. The SIB framework combines the discrete domain capabilities of Genetic Algorithms with the convergence efficiency of Particle Swarm Optimization, replacing PSO's velocity-based update procedure with a MIX operation similar to crossover and mutation in GA [1] [14]. This hybrid approach enables effective navigation of complex, discrete solution spaces characteristic of molecular optimization problems.

The SIB-SOMO algorithm operates through an iterative process of mutation, mixing, and movement operations, maintaining a swarm of particles where each particle represents a potential molecular solution [1]. The algorithm begins by initializing a swarm of particles as carbon chains with a maximum length of 12 atoms, then enters its core optimization loop.

Figure 1: SIB-SOMO Algorithm Workflow

Key Algorithmic Operations

- Mutation Operations: SIB-SOMO employs two distinct mutation strategies—Mutateatom and Mutatebond—that systematically modify atomic properties and bonding patterns to explore new molecular configurations [1].

- MIX Operations: Each particle combines with its Local Best (LB) and Global Best (GB) positions to generate modified particles (mixwLB and mixwGB), with a smaller proportion of entries modified by GB than LB to prevent premature convergence [1] [14].

- MOVE Operation: The algorithm selects the next position from the original particle, mixwLB, and mixwGB based on objective function performance. If no improvement occurs, Random Jump or Vary operations introduce random modifications to escape local optima [1].

Key Advantages of SIB-SOMO

Computational Speed and Efficiency

SIB-SOMO demonstrates remarkable computational efficiency, identifying near-optimal molecular solutions in significantly shorter timeframes compared to alternative methods. This advantage stems from its effective balance between exploration and exploitation through the coordinated use of MIX and mutation operations [1] [14]. The algorithm's design minimizes computational overhead while maximizing search effectiveness in the vast molecular space.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Molecular Optimization Methods

| Method | Optimization Approach | Computational Efficiency | Success Rate | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIB-SOMO | Swarm Intelligence | High - identifies near-optimal solutions rapidly | Not specified in results | No chemical knowledge incorporation |

| EvoMol | Hill-climbing with mutations | Limited by hill-climbing inefficiency | Effective across various objectives | Inefficient in expansive domains |

| MolGAN | GANs with RL objective | Fast training times | Higher chemical property scores | Mode collapse; limited output variability |

| JT-VAE | Latent space sampling | Moderate | Good sample quality | Dependent on training data quality |

| ORGAN | RL on SMILES strings | Moderate | Generates diverse samples | Does not guarantee molecular validity |

| MolDQN | Deep Q-Networks | Training independent of datasets | Effective for targeted properties | Requires careful reward shaping |

Implementation Simplicity

Unlike many deep learning approaches that require extensive training data and complex model architectures, SIB-SOMO features a straightforward implementation based on clearly defined operations. The algorithm is "relatively fast, easy to implement, and computationally efficient for most molecule discovery problems" [1]. This accessibility enables researchers without specialized machine learning expertise to apply advanced optimization techniques to their molecular design challenges.

Chemical Knowledge-Free Design

A distinctive advantage of SIB-SOMO is its independence from pre-existing chemical knowledge or databases. While the authors note that "incorporating such knowledge could potentially reduce the search space," they deliberately designed SIB-SOMO as "free of any chemical knowledge" to create "a general framework for various objective functions in MO" [1]. This domain-agnostic approach allows exploration beyond known chemical spaces and avoids biases inherent in existing chemical databases.

Experimental Protocols and Validation

Benchmarking Methodology

To evaluate SIB-SOMO performance, researchers should employ the Quantitative Estimate of Druglikeness (QED) as a primary objective function. QED integrates eight molecular properties into a single value ranging from 0 (unfavorable) to 1 (favorable), providing a comprehensive measure of druglikeness [1] [14]. The QED is defined by:

[ \text{QED} = \exp\left(\frac{1}{8} \sum{i=1}^8 \ln di(x)\right) ]

where (d_i(x)) represents desirability functions for molecular descriptors including molecular weight (MW), octanol-water partition coefficient (ALOGP), hydrogen bond donors (HBD), hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA), molecular polar surface area (PSA), rotatable bonds (ROTB), and aromatic rings (AROM) [1] [14].

Experimental Workflow

Figure 2: Experimental Validation Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Reagent/Resource | Type | Function in SIB-SOMO | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| QED Framework | Objective Function | Quantifies drug-likeness through 8 molecular properties | Primary optimization target; requires calculated molecular descriptors |

| Molecular Descriptors | Computational Parameters | MW, ALOGP, HBD, HBA, PSA, ROTB, AROM | Calculated for each generated molecule during evaluation |

| Swarm Population | Algorithm Parameter | Set of candidate molecules | Initialized as carbon chains (max 12 atoms); typical size 20-100 particles |

| Mutation Operators | Algorithm Components | Mutateatom and Mutatebond operations | Explore chemical space through structured modifications |

| MIX Operations | Algorithm Components | Combine particles with LB and GB | Balance between exploration and exploitation |

| Benchmark Datasets | Validation Resources | CrossDocked2020, standard molecular sets | Enable performance comparison with alternative methods |

Application Notes for Researchers

Implementation Guidelines

For optimal SIB-SOMO implementation, researchers should:

Initialize the swarm with diverse molecular structures, typically beginning with carbon chains of maximum 12 atoms to ensure chemical plausibility while maintaining computational efficiency [1].

Balance exploration and exploitation by adjusting the proportion of entries modified during MIX operations—typically allowing a smaller proportion to be modified by the Global Best compared to the Local Best to prevent premature convergence [1] [14].

Implement appropriate stopping criteria based on either maximum iterations, computation time, or convergence thresholds when improvement plateaus.

Leverage the Random Jump operation when particles show no improvement to effectively escape local optima and explore new regions of the molecular space [1].

Customization for Specific Objectives

While SIB-SOMO was validated using QED as the objective function, researchers can adapt the algorithm for specific optimization goals by:

- Alternative Objective Functions: Incorporating target-specific properties such as binding affinity, solubility, or synthetic accessibility.

- Multi-Objective Optimization: Extending the framework to handle multiple competing objectives through weighted sum approaches or Pareto optimization.

- Constraint Integration: Incorporating chemical constraints or synthetic feasibility criteria during the mutation and evaluation steps.

Interpretation of Results

When analyzing SIB-SOMO outputs, researchers should consider:

- Chemical Validity: Despite operating without chemical knowledge, SIB-SOMO typically generates chemically valid structures through its mutation operations.

- Novelty Assessment: Comparing optimized molecules against known databases to evaluate the exploration of novel chemical space.

- Diversity Analysis: Ensuring the algorithm produces structurally diverse solutions rather than converging on similar molecular scaffolds.

SIB-SOMO represents a significant advancement in molecular optimization by combining computational efficiency, implementation simplicity, and domain-agnostic exploration. Its unique combination of swarm intelligence principles with molecular design enables rapid discovery of novel chemical entities without constraints imposed by existing chemical knowledge. For drug discovery researchers, SIB-SOMO offers a powerful tool for de novo molecular design that complements existing approaches while overcoming key limitations of both traditional evolutionary algorithms and modern deep learning methods. As the field advances, future work may focus on incorporating specialized chemical knowledge for specific optimization domains while maintaining the algorithm's general applicability and efficiency.

Inside SIB-SOMO: Algorithmic Mechanics and Practical Implementation

The Swarm Intelligence-Based method for Single-Objective Molecular Optimization (SIB-SOMO) represents a significant advancement in the field of de novo drug design. This algorithm addresses the critical challenge of navigating the virtually infinite molecular space to identify compounds with desired pharmaceutical properties. By integrating principles from swarm intelligence and self-organizing map (SOM) optimization, SIB-SOMO provides a robust framework for molecular optimization without relying on pre-existing chemical databases, enabling the discovery of novel chemical structures from scratch [1].

The algorithm's importance stems from its ability to overcome limitations of traditional optimization methods that struggle with the discrete nature of molecular space. As a metaheuristic approach, SIB-SOMO demonstrates versatility across various optimization problems regardless of the nature of the objective functions. Several experiments have showcased the efficiency of the proposed method, which identifies near-optimal solutions in remarkably short timeframes compared to other state-of-the-art methods in the field [1].

Theoretical Foundation and Algorithmic Principles

Core Components of the SIB-SOMO Framework

The SIB-SOMO algorithm builds upon the canonical Swarm Intelligence-Based (SIB) method, which combines the discrete domain capabilities of Genetic Algorithms (GA) with the convergence efficiency of Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) [1]. This hybrid approach leverages the general framework of PSO, including Local Best (LB) and Global Best (GB) solutions and information exchange among particles, while replacing the velocity-based update procedure with a MIX operation similar to crossover and mutation in GA [1].

The theoretical foundation of SIB-SOMO also draws from Self-Organizing Map (SOM) optimization algorithms. SOM-based optimization (SOMO) is an optimization algorithm based on the self-organizing map that finds a winner in the network through a competitive learning process [21]. Generally, the SOMO algorithm searches for the minimum of an objective function through this process. The MaxMin-SOMO algorithm represents a generalization of SOMO with two winners for simultaneously finding two winning neurons, where the first winner stands for the minimum and the second one for the maximum of the objective function [21].

Molecular Optimization Problem Formulation

In the context of molecular optimization, SIB-SOMO addresses the fundamental challenge of exploring a highly complex and nearly infinite molecular space. For perspective, with just 17 heavy atoms (C, N, O, S, and Halogens), there are estimated to be over 165 billion chemical combinations [1]. The Molecular Optimization (MO) problem involves optimizing desired molecular properties, which is essential for drug discovery applications.

The algorithm employs the Quantitative Estimate of Druglikeness (QED) as a key objective function, which integrates eight commonly used molecular properties into a single value, allowing for the ranking of compounds based on their relative significance [1]. The QED is defined by the equation:

$$QED=exp\Bigg(\frac{1}{8}\sum{i=1}^8lndi(x)\Bigg)$$

Where $d_i(x)$ represents the desirability function for the molecular descriptor $x$, implemented using a symmetric double sigmoid function with parameters $a$, $b$, $c$, $d$, $e$, and $f$ for each desirability function [1].

SIB-SOMO Workflow: Component Deconstruction

Algorithm Initialization and Particle Representation

The SIB-SOMO algorithm begins by initializing a swarm of particles, where each particle represents a molecule within the swarm. The initial configuration typically starts as a carbon chain with a maximum length of 12 atoms [1]. This initialization strategy provides a foundational structure that the algorithm will subsequently optimize through iterative processes.

The representation of molecules as particles enables the application of swarm intelligence principles to molecular optimization. Each particle's position corresponds to a specific molecular configuration, and the collective behavior of the swarm facilitates efficient exploration of the chemical space. The initialization phase is critical as it establishes the starting point for the optimization process and can influence the algorithm's convergence properties.

Core Operational Components

The SIB-SOMO algorithm employs several specialized operations to navigate the molecular search space effectively. These operations work in concert to balance exploration and exploitation throughout the optimization process.

MUTATION Operations:

- Mutate_atom: This operation modifies atomic properties within the molecular structure, enabling the exploration of different elemental compositions.

- Mutate_bond: This operation alters bonding patterns between atoms, facilitating structural diversity in the generated molecules [1].

MIX Operations: The MIX operation combines each particle with its Local Best (LB) and Global Best (GB) to generate two modified particles, termed mixwLB and mixwGB respectively. A proportion of entries in each particle is modified based on the values from the best particles. This proportion is typically smaller for entries modified by the GB compared to those modified by the LB to prevent premature convergence [1].

MOVE Operation: The MOVE operation selects the particle's next position based on the objective function evaluation of the original particle and the two modified particles (mixwLB and mixwGB). If either modified particle performs better than the original, it becomes the new position. If the original particle remains the best, a Random Jump operation is applied to it [1].

Random Jump Operation: This operation randomly alters a portion of the particle's entries to avoid getting trapped in a local optimum. It serves as a diversification mechanism that promotes exploration of uncharted regions in the molecular search space [1].

Vary Operation: An additional operation that may be executed under specific conditions to further enhance exploration capabilities [1].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the complete SIB-SOMO workflow, integrating all operational components into a cohesive process:

SIB-SOMO Complete Algorithm Workflow

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Key Experimental Parameters

Successful implementation of SIB-SOMO requires careful configuration of algorithm parameters. The table below summarizes the key parameters used in molecular optimization experiments:

Table 1: SIB-SOMO Algorithm Parameters for Molecular Optimization

| Parameter Category | Specific Parameter | Typical Value/Range | Function in Algorithm |

|---|---|---|---|

| Swarm Configuration | Swarm Size | Varies by problem complexity | Determines number of parallel exploration trajectories |

| Initial Molecule | Carbon chain (max 12 atoms) | Starting point for molecular optimization [1] | |

| Mutation Parameters | Mutate_atom Rate | Problem-dependent | Controls frequency of atomic modifications [1] |

| Mutate_bond Rate | Problem-dependent | Controls frequency of bond alterations [1] | |

| MIX Operation Parameters | LB Modification Proportion | Higher value | Greater influence from local best solution [1] |

| GB Modification Proportion | Lower value | Controlled influence from global best to prevent premature convergence [1] | |

| Convergence Control | Maximum Iterations | Problem-dependent | Prevents infinite loops |

| Convergence Threshold | Defined by objective function | Determines when optimization satisfactory | |

| Random Jump Magnitude | Problem-dependent | Controls exploration when no improvement [1] |

Molecular Property Assessment Protocol

The evaluation of molecular candidates generated by SIB-SOMO follows a structured protocol centered on the Quantitative Estimate of Druglikeness (QED). The implementation details for this assessment are crucial for reproducible results:

Step 1: Molecular Descriptor Calculation

- Calculate the eight molecular properties comprising the QED: molecular weight (MW), octanol-water partition coefficient (ALOGP), number of hydrogen bond donors (HBD), number of hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA), molecular polar surface area (PSA), number of rotatable bonds (ROTB), and number of aromatic rings (AROM) [1].

- Employ standardized computational chemistry tools for descriptor calculation to ensure consistency.

Step 2: Desirability Function Application

- For each descriptor, apply the corresponding desirability function $d_i(x)$ using the predefined parameters $a$, $b$, $c$, $d$, $e$, and $f$ for each molecular property [1].

- The desirability functions transform each molecular property into a dimensionless value between 0 and 1, where 1 represents an ideal value for druglikeness.

Step 3: QED Computation

- Compute the final QED value using the geometric mean of the eight desirability scores as defined in the QED equation [1].

- The geometric mean ensures that no single poor property can be compensated for by multiple good properties.

Step 4: Objective Function Optimization

- Utilize the computed QED as the objective function guiding the SIB-SOMO optimization process.

- The algorithm seeks to maximize the QED value, driving the molecular generation toward more drug-like compounds.

Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

The experimental implementation of SIB-SOMO requires specific computational tools and resources. The table below details the essential components of the research toolkit for molecular optimization:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for SIB-SOMO Implementation

| Tool Category | Specific Tool/Resource | Function in Workflow | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Informatics Libraries | RDKit or OpenBabel | Molecular representation and manipulation | Handles molecular structure operations and descriptor calculations |

| Numerical Computing | NumPy/SciPy (Python) or equivalent | Mathematical computations and optimization | Implements core algorithm logic and numerical operations |

| Swarm Intelligence Framework | Custom SIB-SOMO implementation | Core optimization algorithm | Executes the particle swarm optimization with molecular-specific operations |

| Visualization Tools | Molecular visualization software (e.g., PyMol) | Result analysis and interpretation | Enables visual inspection of optimized molecular structures |

| Validation Tools | Chemical database screening tools | Result validation against known compounds | Assesses novelty of generated molecules |

| High-Performance Computing | Parallel processing infrastructure | Accelerates computational intensive evaluations | Enables practical application to complex molecular optimization problems |

Comparative Analysis with Alternative Methods

Performance Evaluation Framework

The effectiveness of SIB-SOMO can be contextualized through comparison with other molecular optimization approaches. Two primary categories of methods exist: Evolutionary Computation (EC) methods and Deep Learning (DL) methods [1].

Evolutionary Computation Competitors:

- EvoMol: A representative EC approach that builds molecular graphs sequentially using a hill-climbing algorithm combined with seven chemically meaningful mutations. While EvoMol has demonstrated effective performance across various MO objectives, its optimization efficiency is limited by the inherent inefficiency of hill-climbing algorithms, especially in expansive domains [1].

Deep Learning Competitors:

- MolGAN: Combines Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) with a reinforcement learning objective to produce small molecular graphs with desired properties. Compared to SMILES-based sequential GAN models, MolGAN achieves higher chemical property scores and faster training times but is susceptible to mode collapse, which can limit output variability [1].

- Junction Tree Variational Autoencoder (JT-VAE): A deep generative model that maps molecules to a high-dimensional latent space and uses sampling or optimization techniques to generate new molecules [1].

- Objective-Reinforced Generative Adversarial Networks (ORGAN): Leverages reinforcement learning to generate molecules from SMILES strings. This adversarial approach helps in producing diverse samples but does not guarantee the validity of the generated molecules [1].

- MolDQN: Integrates domain knowledge with reinforcement learning by framing molecule modification as a Markov Decision Process (MDP) and solving it using Deep Q-Networks (DQN). MolDQN is trained from scratch, making its training independent of any pre-existing dataset [1].

SIB-SOMO Advantages and Limitations

The SIB-SOMO algorithm demonstrates several distinct advantages in molecular optimization:

- Computational Efficiency: The method identifies near-optimal solutions in remarkably short timeframes compared to state-of-the-art alternatives [1].

- Implementation Simplicity: Compared to existing metaheuristic optimization approaches, SIB-SOMO is relatively fast, easy to implement, and computationally efficient for most molecule discovery problems [1].

- Knowledge-Free Operation: SIB-SOMO is free of any chemical knowledge, though incorporating such knowledge could potentially reduce the search space. This design aligns with the goal of proposing a general framework for various objective functions in MO [1].

- Exploration-Exploitation Balance: The combination of MIX operations with Random Jump effectively balances local refinement with global exploration.

The algorithm's limitations include:

- Parameter Sensitivity: Like many metaheuristic approaches, performance may be sensitive to parameter settings.

- Domain Knowledge Exclusion: The conscious decision to avoid incorporating complex chemical rules may limit efficiency for domain-specific applications where such knowledge is available.

- Theoretical Guarantees: As with most metaheuristic optimization methods, SIB-SOMO does not guarantee finding the global optimum unless the optimal value of the objective function is theoretically derived and achieved by the algorithm [1].

Advanced Implementation Considerations

Molecular Representation and Operations

The internal representation of molecules within SIB-SOMO requires careful design to enable efficient optimization. The algorithm operates on molecular structures directly, employing specialized operations for molecular modification:

Molecular Operations and QED Assessment Workflow

Convergence Optimization Strategies

Enhancing the convergence properties of SIB-SOMO involves several advanced strategies:

Adaptive Parameter Adjustment: Implement dynamic adjustment of algorithm parameters based on search progress. For example, gradually reducing the scope of Random Jump operations as convergence approaches can refine the final optimization stage.

Hybrid Initialization: Combine random initialization with heuristic-based initialization to start the search from promising regions of the molecular space. This approach can significantly reduce the time to convergence.