Tree-Based Model Performance Under Imbalance: A 2025 Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive framework for evaluating the predictive performance of tree-based models under varying class balance conditions, a critical challenge in biomedical and clinical research where datasets often exhibit severe imbalance. We explore the foundational principles of tree balance, methodological adaptations like hybrid sampling and ensemble techniques, and advanced optimization strategies to mitigate overfitting and bias. Through a comparative analysis of state-of-the-art models, including Elastic Net regression, Balanced Hoeffding Tree Forests, and optimized ensembles, this guide offers actionable insights for researchers and drug development professionals to build more accurate, robust, and interpretable predictive models for healthcare applications.

Tree-Based Model Performance Under Imbalance: A 2025 Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for evaluating the predictive performance of tree-based models under varying class balance conditions, a critical challenge in biomedical and clinical research where datasets often exhibit severe imbalance. We explore the foundational principles of tree balance, methodological adaptations like hybrid sampling and ensemble techniques, and advanced optimization strategies to mitigate overfitting and bias. Through a comparative analysis of state-of-the-art models, including Elastic Net regression, Balanced Hoeffding Tree Forests, and optimized ensembles, this guide offers actionable insights for researchers and drug development professionals to build more accurate, robust, and interpretable predictive models for healthcare applications.

Understanding Tree Balance: Core Concepts and Challenges in Clinical Datasets

Defining Tree Balance and Data Imbalance in Predictive Modeling

In predictive modeling, the term "imbalance" can refer to two distinct but crucial concepts: the balance of a tree structure used in algorithms like Decision Trees, and the class distribution within a dataset. Understanding both is essential for developing robust models, especially in high-stakes fields like drug development where interpretability and performance are paramount.

Tree Balance pertains to the symmetry and branching structure of tree-based models or phylogenetic trees, influencing algorithmic efficiency and interpretability [1] [2]. Data Imbalance, conversely, describes a skewed distribution of classes in a dataset, which can severely bias a model's predictions if not properly addressed [3] [4] [5]. This guide objectively compares predictive performance across these balance conditions, providing a framework for researchers to optimize model selection and evaluation.

Defining the Domains of Imbalance

Tree Balance: A Structural Property

Tree balance quantifies the symmetry of a rooted tree's branching pattern. In a perfectly balanced tree, leaf nodes are distributed as evenly as possible across the structure, leading to minimal depth and efficient search operations. This concept is vital in phylogenetics for testing evolutionary hypotheses and in computer science for ensuring the efficiency of tree-based algorithms [1] [6] [2].

- Key Indices and Measures: More than 25 distinct tree balance indices exist, each ranking trees from the most balanced to the least balanced (caterpillar tree) [6] [2].

- Impact on Performance: The balance of a tree directly affects the performance of algorithms operating on it. For instance, a search operation in a balanced binary search tree with

nleaves has a time complexity ofO(log n), whereas the same operation on a completely imbalanced caterpillar tree degrades toO(n)[1] [2].

The table below summarizes three key tree balance indices.

Table 1: Key Indices for Measuring Tree Balance

| Index Name | Brief Description | Minimized By | Maximized By |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sackin Index | Sums the depths of all leaves in the tree [1]. | Fully balanced / GFB trees [1] [2]. | Caterpillar tree [1] [2]. |

| Colless Index | Measures the imbalance for each internal node based on the difference in the number of leaves in its two descendant subtrees [1] [6]. | Fully balanced / GFB trees [1] [2]. | Caterpillar tree [1] [2]. |

| Symmetry Nodes Index (SNI) | Counts the number of internal nodes that are not symmetry nodes (where a symmetry node has isomorphic pendant subtrees) [7]. | Trees with maximal symmetry nodes [7]. | Caterpillar tree [7]. |

Data Imbalance: A Dataset Property

Data imbalance occurs when the number of observations in one class (the majority class) significantly outweighs those in another (the minority class). This is a common scenario in real-world applications like fraud detection (where most transactions are legitimate) and medical diagnostics (where a disease may be rare) [3] [5] [8]. Conventional classifiers are often biased toward the majority class, treating the minority class as noise and leading to high false negative rates for the class of interest [5].

- Evaluation Metrics: In imbalanced domains, standard metrics like accuracy are misleading. A model that simply classifies all instances as the majority class can achieve high accuracy while failing entirely to identify the minority class [4] [5]. Instead, metrics such as precision, recall, F1-score, and ROC AUC should be prioritized to accurately assess performance on the minority class [3] [4] [8].

Experimental Comparison: Performance Across Balance Conditions

This section compares the performance of predictive models under varying conditions of data and tree imbalance, drawing on established experimental protocols.

Experimental Protocol 1: Handling Data Imbalance with Decision Trees

- Objective: To evaluate the efficacy of different strategies for improving Decision Tree performance on an imbalanced dataset.

- Dataset Generation: A highly imbalanced synthetic dataset is created using

make_classificationfrom libraries like scikit-learn, with a class distribution controlled by theweightsparameter (e.g., [0.7, 0.2, 0.1]) [3]. - Model Training & Evaluation:

- A baseline Decision Tree is trained without any imbalance adjustments.

- Comparative models are trained using techniques like cost-sensitive learning (setting

class_weight='balanced'), oversampling (SMOTE), and undersampling [3] [5]. - Models are evaluated using a hold-out test set and metrics such as the classification report (precision, recall, F1-score) and ROC AUC score [3].

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Data Imbalance Mitigation Techniques on a Synthetic Dataset

| Model Strategy | Precision (Minority Class) | Recall (Minority Class) | F1-Score (Minority Class) | ROC AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Decision Tree | Low (e.g., < 0.5) | Very Low (e.g., ~0.0) | Very Low (e.g., ~0.0) | ~0.5 |

| Class Weight Balancing | High [3] | High [3] | High [3] | High [3] |

| SMOTE Oversampling | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Random Undersampling | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

Experimental Protocol 2: Analyzing Tree Shape in Phylogenetics

- Objective: To understand the power of different tree balance indices to detect deviations from a null evolutionary model (e.g., the Yule model) [6].

- Methodology:

- Tree Simulation: Generate a large number of phylogenetic trees under both the null model (e.g., Yule) and various alternative models (e.g., models incorporating selection or fertility inheritance) [6].

- Index Calculation: For each generated tree, calculate a wide array of balance indices (Sackin, Colless, SNI, etc.) [6] [7].

- Power Analysis: Use statistical tests to determine which indices are most effective (powerful) at distinguishing between trees generated under the null model and those from alternative models. The

poweRbalR package facilitates this analysis [6].

Table 3: Power of Different Balance Indices to Detect Model Deviations (Illustrative)

| Tree Balance Index | Power vs. Yule Model (Alternative A) | Power vs. Yule Model (Alternative B) |

|---|---|---|

| Sackin Index | High | Moderate |

| Colless Index | High | Low |

| Symmetry Nodes Index (SNI) | Moderate | High |

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Methods

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item / Solution | Function in Research | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Imbalanced-learn Library | Provides a suite of resampling techniques (SMOTE, Tomek links) to handle imbalanced datasets in Python [8]. | imblearn.over_sampling.SMOTE |

| scikit-learn | Offers machine learning algorithms, including Decision Trees with class_weight parameter for cost-sensitive learning, and metrics for evaluation [3]. |

sklearn.tree.DecisionTreeClassifier |

| R poweRbal Package | Enables comprehensive power analysis of tree balance indices against various phylogenetic models [6]. | R software package |

| symmeTree R Package | Implements the calculation of the Symmetry Nodes Index (SNI) and other related balance indices for phylogenetic trees [7]. | R software package |

| Synthetic Data Generators | Creates customizable imbalanced datasets for controlled experiments [3]. | sklearn.datasets.make_classification |

| Transcriptional Intermediary Factor 2 (TIF2) (740-753) | Transcriptional Intermediary Factor 2 (TIF2) (740-753), MF:C75H124N20O25, MW:1705.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Kdm2B-IN-3 | Kdm2B-IN-3|KDM2B Inhibitor|Research Compound | Kdm2B-IN-3 is a potent, cell-active KDM2B inhibitor for cancer research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or diagnostic use. |

Visualizing Workflows and Relationships

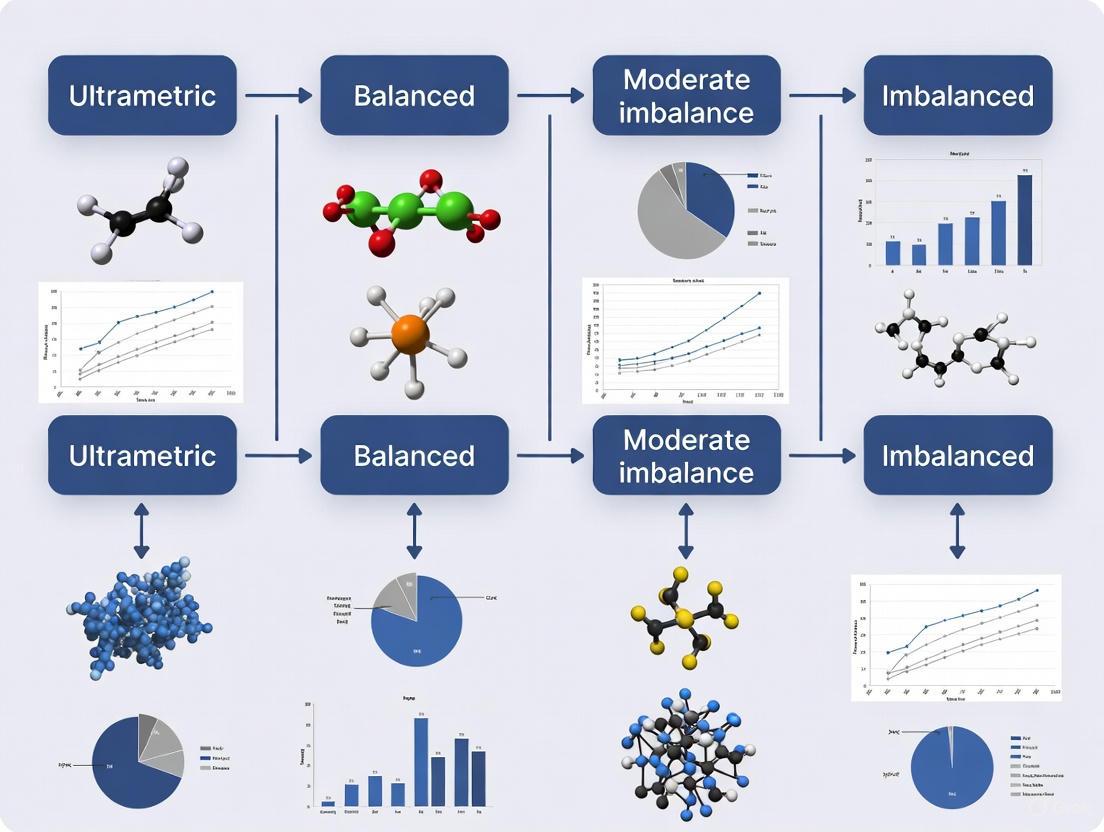

The following diagrams illustrate the core concepts and experimental pathways discussed in this guide.

Diagram 1: Conceptual relationship between tree balance and data imbalance in predictive modeling.

Diagram 2: A unified experimental workflow for evaluating predictive performance, integrating checks for both data and tree imbalance.

In clinical research, the challenge of class imbalance is not an exception but a pervasive rule. This phenomenon, where one class of data significantly outnumbers another, fundamentally shapes the development and performance of predictive models, from identifying rare genetic disorders to predicting adverse drug outcomes. The core of the issue lies in the inherent nature of health and disease: most medical conditions are, by definition, rare events within populations, and even common diseases manifest severe complications infrequently. This imbalance creates substantial methodological challenges that can distort performance metrics, lead to misleading conclusions, and ultimately hamper the translation of research into effective clinical tools.

The implications extend across the entire research continuum. In rare disease research, where individual conditions may affect fewer than 1 in 2,000 people, the fundamental challenge is insufficient data for model training [9]. Conversely, in adverse outcome prediction, such as forecasting opioid overdose risk, the problem manifests as extreme ratio imbalances where non-events may outnumber events by factors of 100:1 to 1000:1 [10]. In both scenarios, standard analytical approaches and evaluation metrics can produce dangerously optimistic results that fail to translate to real-world clinical utility. Understanding these challenges—and the methodologies developed to address them—constitutes a critical foundation for advancing predictive performance across the spectrum of clinical research.

The Dual Frontiers of Imbalance: Rare Diseases and Adverse Outcomes

Class imbalance in clinical research primarily manifests in two distinct yet interconnected domains: rare diseases and adverse outcome prediction. The table below systematizes the characteristics and challenges across these domains.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Imbalance in Clinical Research Domains

| Aspect | Rare Diseases Research | Adverse Outcome Prediction |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Diseases with prevalence <1 in 2,000 individuals [9] | Scenarios where non-events outnumber events by moderate to extreme degrees [10] |

| Primary Challenge | Diagnostic delays due to low awareness and insufficient data [9] | Predictive models achieve spuriously high accuracy by classifying all observations as non-events [10] |

| Typical Prevalence/Imbalance Ratio | Individual diseases are rare (collectively affect 300M+ globally) [9] | Ratios from 10:1 to 1000:1 (non-events:events) documented in opioid-related outcomes [10] |

| Key Methodological Concern | Lack of multidisciplinary approach and specialist scarcity [9] | Inappropriate performance metrics (e.g., overall accuracy) provide misleading optimism [10] |

| Impact on Clinical Practice | Increased morbidity and mortality due to diagnostic delays [9] | Reduced clinical utility of risk prediction tools despite apparently high statistical performance [10] |

The Rare Disease Diagnostic Paradigm

The challenge in rare diseases extends beyond simple data scarcity to encompass systemic diagnostic barriers. A survey of specialists revealed that 86% reported significant diagnostic challenges that negatively affected their clinical practice [9]. The primary obstacles include low physician awareness, fragmented multidisciplinary approaches, inadequate infrastructure, and limited newborn screening programs. These factors collectively create a "diagnostic odyssey" for patients, where the journey to accurate diagnosis can span years, during which time disease progression continues unabated [9]. The solution landscape emphasizes enhanced specialist training, formalized multidisciplinary teams, standardized diagnostic algorithms, and robust disease registries to consolidate scarce information across disparate cases [9].

The Adverse Outcome Prediction Challenge

In adverse outcome prediction, the imbalance problem distorts the very metrics used to evaluate model success. A simulation study examining opioid overdose prediction demonstrated that as imbalance increased from balanced (1:1) to extreme (1000:1), overall accuracy appeared to improve from 0.45 to 0.99—seemingly exceptional performance [10]. However, this apparent improvement was entirely misleading. The corresponding Positive Predictive Value (PPV) simultaneously decreased from 0.99 to 0.14, revealing that the model was simply classifying most observations as non-events [10]. This metric distortion creates a critical gap between statistical performance and clinical utility, potentially leading to deployment of ineffective risk prediction tools in consequential healthcare decisions.

Methodological Approaches and Experimental Evaluation

Addressing class imbalance requires both algorithmic innovation and rigorous evaluation methodologies. Research has explored multiple pathways, from data-level interventions to specialized modeling techniques.

Synthetic Data Generation and Augmentation

Synthetic data generation represents a promising approach to addressing data scarcity in imbalanced clinical datasets. Advanced techniques include:

- Synthetic Minority Oversampling (SMOTE) & Adaptive Synthetic Sampling (ADASYN): These techniques generate synthetic minority class samples through interpolation, helping to balance class distributions [11].

- Deep Conditional Tabular Generative Adversarial Networks (Deep-CTGANs) with ResNet: This hybrid approach integrates residual connections to improve feature learning and capture complex, non-linear patterns in clinical data [11].

- Evaluation via Training on Synthetic, Testing on Real (TSTR): This validation framework assesses whether synthetic data preserves the statistical properties of real data by testing model performance on real clinical datasets after training on synthetic data [11].

Experimental results demonstrate that this approach can achieve high testing accuracies (99.2-99.5% across COVID-19, Kidney, and Dengue datasets) while maintaining similarity scores of 84-87% between real and synthetic data distributions [11].

Tree Boosting Methods for Imbalanced Classification

Tree boosting methods, particularly XGBoost, have demonstrated notable performance for imbalanced tabular data. A comprehensive evaluation examined these methods across datasets of varying sizes (1K, 10K, and 100K samples) and class distributions (50%, 45%, 25%, and 5% positive samples) [12]. Key findings include:

Table 2: Performance of Tree Boosting Methods Across Imbalance Conditions

| Data Volume | Class Distribution (% Positive) | F1-Score Performance | Effect of Sampling to Balance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1K samples | 50% to 5% | Decreases with increasing imbalance | Deteriorates detection performance [12] |

| 10K samples | 50% to 5% | Superior to baseline but imbalance-sensitive | No consistent improvement [12] |

| 100K samples | 50% to 5% | Remains significantly above baseline | Worsens recognition despite imbalance [12] |

The research revealed two critical insights: first, that F1-scores improve with data volume but decrease as imbalance increases; and second, that simple sampling to balance training sets does not consistently improve performance and often deteriorates detection of the minority class [12]. This challenges conventional approaches to handling imbalance and underscores the need for more sophisticated methodologies.

Experimental Protocol for Imbalance Research

To ensure reproducible evaluation of methods addressing class imbalance, researchers should adhere to standardized experimental protocols:

- Data Simulation Design: Employ Monte Carlo simulations with sufficient repetitions (e.g., 250 repetitions) to ensure statistical reliability [10].

- Controlled Imbalance Generation: Create datasets with progressively increasing imbalance ratios (e.g., 1:1, 10:1, 100:1, 1000:1) while holding other variables constant to isolate the effect of imbalance [10].

- Comprehensive Metric Selection: Move beyond overall accuracy to include imbalance-sensitive metrics including F1-score, Positive Predictive Value, and area under the precision-recall curve [10] [12].

- Model Comparison Framework: Evaluate both conventional (logistic regression) and advanced methods (random forest, XGBoost, Imbalance-XGBoost) across the same imbalance conditions [10] [12].

- Robustness Over Time Assessment: Test model performance on temporal validation sets to evaluate robustness to data drift, with retraining protocols when performance deteriorates beyond established thresholds [12].

Experimental Protocol for Imbalance Research

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Solutions for Imbalanced Data

Navigating the challenges of imbalanced clinical data requires a sophisticated toolkit of methodological approaches, evaluation metrics, and technical solutions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Imbalanced Clinical Data

| Solution Category | Specific Technique/Tool | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Data Generation | SMOTE/ADASYN [11] | Generates synthetic minority class samples through interpolation to balance datasets |

| Deep Generative Models | Deep-CTGAN + ResNet [11] | Captures complex, non-linear feature relationships in clinical data through deep learning |

| Specialized Classifiers | TabNet [11] | Sequential attention mechanism for dynamic feature processing in tabular clinical data |

| Gradient Boosting Frameworks | XGBoost, Imbalance-XGBoost [12] | Tree-based ensemble methods robust to imbalance and effective for tabular clinical data |

| Model Interpretation | SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) [11] | Explains model predictions and feature importance for transparency and clinical trust |

| Evaluation Metrics | F1-Score, PPV, AUC-PR [10] [12] | Provides realistic assessment of minority class performance beyond overall accuracy |

| Validation Frameworks | TSTR (Train on Synthetic, Test on Real) [11] | Validates synthetic data quality by testing generalizability to real clinical datasets |

| SSAO inhibitor-1 | SSAO inhibitor-1, MF:C17H24FN5O2, MW:349.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 3-Epi-Deoxynegamycin | 3-Epi-Deoxynegamycin|Readthrough Compound|RUO | Research-grade 3-Epi-Deoxynegamycin, a potent eukaryotic readthrough agent for nonsense mutation studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

Solution Framework for Imbalanced Clinical Data

The pervasiveness of imbalance in clinical research necessitates a fundamental shift in methodological approach. From rare diseases to adverse outcome prediction, the challenges are substantial but not insurmountable. The path forward requires abandoning misleading metrics like overall accuracy in favor of imbalance-sensitive evaluation, strategic integration of synthetic data generation where appropriate, and leveraging specialized algorithms that maintain performance across imbalance conditions. Most importantly, researchers must recognize that addressing imbalance is not merely a technical statistical exercise but a prerequisite for developing clinically useful tools that can genuinely improve patient outcomes across the spectrum of healthcare challenges. As the field advances, the methodologies refined on these challenging problems may well become the standard approach for all clinical prediction research, ultimately strengthening the bridge between statistical innovation and clinical impact.

The Impact of Skewed Data on Model Accuracy, Bias, and Clinical Utility

Skewed or imbalanced data, where one class is significantly over-represented compared to others, presents a substantial challenge for predictive modeling in healthcare and biomedical research. This imbalance can severely degrade model performance, introduce algorithmic biases, and diminish clinical utility, particularly for tree-based ensemble methods and other machine learning approaches critical to drug development and clinical decision support [13]. In healthcare applications, this problem is pervasive, as conditions of interest such as rare diseases, adverse drug events, or specific cancer subtypes often constitute the minority class [14] [15].

The impact extends beyond mere statistical performance metrics to affect real-world clinical applications. When models trained on skewed data demonstrate poor generalizability across diverse patient populations, they can exacerbate existing healthcare disparities and reduce the practical value of AI-assisted clinical tools [16] [17]. Understanding and mitigating these effects is therefore essential for developing reliable, equitable, and clinically useful predictive models in biomedical research and development.

Experimental Protocols for Evaluating Skewed Data Impact

Three-Phase Evaluation Framework for Clinical Prediction Models

A comprehensive 3-phase evaluation framework has been developed to assess how data biases affect model generalizability and clinical utility, with particular relevance to healthcare applications [14]. This methodology systematically evaluates model performance across internal, external, and retraining scenarios:

Phase 1: Internal Validation - The model is trained and validated on the original development dataset using bootstrapping with 2000 iterations to generate optimism-corrected performance estimates [14]. This establishes the baseline performance under ideal conditions.

Phase 2: External Validation - The pre-trained model is applied to an entirely external database to evaluate transportability and generalizability across different populations and healthcare settings [14]. This phase is critical for identifying performance degradation in real-world scenarios.

Phase 3: Model Retraining - The model architecture is retrained using data from the external cohort to determine whether performance improvements can be achieved through population-specific training [14]. This phase helps distinguish between immutable algorithmic limitations and addressable data representation issues.

Throughout all phases, subgroup analyses are conducted across four key categories: (1) demographic groups (e.g., gender, race), (2) clinically vulnerable populations (e.g., patients with diabetes, depression), (3) risk groups (e.g., prior opioid-exposed vs. opioid-naive patients), and (4) comorbidity severity levels based on Charlson Comorbidity Index scores [14].

Enhanced Tree Ensemble (ETE) Methodology for Imbalanced Data

The Enhanced Tree Ensemble (ETE) method addresses extreme class imbalance through a combination of synthetic data generation and selective tree ensemble construction [13]. The protocol consists of two main variants:

ETEOOB - Utilizes out-of-bag (OOB) observations to estimate individual tree performance during the training process [13]. Trees demonstrating superior performance on these unseen OOB samples are preferentially selected for the final ensemble.

ETESS - Employs sub-sampling without replacement to create diverse training subsets for each tree, then applies similar performance-based selection criteria [13].

The data balancing process generates Kb synthetic minority class observations, where Kb = n1 - n0 (the difference between majority and minority class sizes) [13]. For each synthetic instance, bootstrap samples of size n0 are drawn from the minority class, and feature values are computed as the mean (for numerical features) or mode (for categorical features) across the bootstrap sample [13].

TreeEM Framework for Cancer Subtype Classification

The TreeEM model addresses high-dimensional, imbalanced omics data through an integrated approach combining feature selection with ensemble methods [15]. The experimental protocol includes:

Feature Selection - Application of Max-Relevance and Min-Redundancy (MRMR) feature selection to reduce dimensionality and eliminate redundant genetic markers [15].

Imbalanced Learning - Implementation of improved fusion undersampling random forest combined with extreme tree forest architectures [15].

Validation - Performance evaluation across multiple cancer datasets, particularly multi-omics BRCA and ARCENE datasets, with comparison against baseline methods [15].

Comparative Performance Analysis of Methods for Skewed Data

Resampling Techniques and Strong Classifiers

Table 1: Performance comparison of approaches for handling class imbalance

| Method Category | Representative Techniques | Performance Findings | Optimal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oversampling | SMOTE, Random Oversampling | Minimal improvement for strong classifiers (XGBoost, CatBoost); potential benefits for weak learners (decision trees, SVM) [18] | Weak classifiers; models without probabilistic output [18] |

| Undersampling | Random Undersampling, Instance Hardness Threshold | Mixed results; improves performance for some datasets with random forests, but inconsistent benefits [18] | Specific dataset characteristics; computational efficiency requirements [18] |

| Strong Classifiers | XGBoost, CatBoost | Effective at learning from imbalanced data without resampling when probability thresholds are properly tuned [18] | General recommendation; requires threshold optimization [18] |

| Specialized Ensembles | EasyEnsemble, Balanced Random Forest | Outperformed AdaBoost in 8-10 datasets; promising for imbalanced learning [18] | When standard ensembles underperform; balanced performance requirements [18] |

| Enhanced Tree Ensembles | ETEOOB, ETESS | Superior to SMOTE-RF, Oversampling RF, Undersampling RF, and traditional classifiers in extreme imbalance scenarios [13] | Extreme class imbalance; need for synthetic data generation [13] |

Clinical Impact and Fairness Metrics

Table 2: Clinical utility and bias assessment across patient subgroups

| Evaluation Dimension | Metrics | Findings from Healthcare Case Studies | Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Predictive Performance | AUROC, AUPRC, Brier Score | AUROC decreased from 0.74 (internal) to 0.70 (external validation); retraining on external data improved AUROC to 0.82 [14] | Significant performance shifts across populations affect reliability |

| Clinical Utility | Standardized Net Benefit (SNB), Decision Curve Analysis | Systematic shifts in net benefit across threshold probabilities; differential utility across subgroups [14] | Impacts clinical decision-making and resource allocation |

| Fairness Assessment | Performance parity across subgroups | Minimal AUROC deviation across subgroups (mean = 0.69, SD = 0.01) but varying clinical utility [14] | Performance parity insufficient to ensure equitable benefits |

| Bias Detection | Subgroup analysis, Error rate disparities | Underperformance in minority patient groups and atypical presentations [17] | Potentially exacerbates healthcare disparities if unaddressed |

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

Three-Phase Bias Evaluation Framework

Enhanced Tree Ensemble (ETE) Methodology

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key computational tools for skewed data research in biomedical applications

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Imbalanced-learn | Python library providing resampling techniques (SMOTE, random under/oversampling) and specialized ensembles [18] | Data preprocessing for classical machine learning models |

| TreeEM Framework | Integrated extreme random forest with MRMR feature selection for high-dimensional omics data [15] | Cancer subtype classification from imbalanced genomic datasets |

| Enhanced Tree Ensemble (ETE) | Synthetic data generation combined with performance-based tree selection for extreme imbalance [13] | Binary classification with severe class imbalance |

| OHDSI PLP Package | Observational Health Data Sciences and Informatics patient-level prediction framework [14] | Clinical prediction model development and validation |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | Model interpretation and feature importance quantification [19] | Explainable AI for clinical decision support systems |

| Standardized Net Benefit (SNB) | Clinical utility assessment across probability thresholds [14] | Evaluating real-world impact of predictive models |

| Vimirogant hydrochloride | Vimirogant hydrochloride, MF:C27H36ClF3N4O3S, MW:589.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Ctap tfa | Ctap tfa, MF:C53H70F3N13O13S2, MW:1218.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Discussion and Future Directions

The comprehensive analysis of methods addressing skewed data reveals several critical insights for biomedical researchers and drug development professionals. First, the choice between resampling techniques and algorithmic approaches should be guided by both the characteristics of the data and the intended clinical application. While strong classifiers like XGBoost often demonstrate robustness to class imbalance without resampling [18], specialized approaches like Enhanced Tree Ensembles [13] and TreeEM [15] show particular promise for extreme imbalance scenarios and high-dimensional omics data.

Second, technical performance metrics alone are insufficient for evaluating models destined for clinical implementation. The three-phase evaluation framework demonstrates that models maintaining apparent performance parity across subgroups can still exhibit significant differences in clinical utility [14]. This highlights the necessity of incorporating decision-analytic measures like Standardized Net Benefit into validation frameworks, particularly for applications affecting resource allocation or clinical decision-making.

Future research should focus on developing more sophisticated fairness-aware learning algorithms that explicitly optimize for equitable clinical utility across diverse patient populations. Additionally, greater attention is needed to temporal validation and monitoring frameworks that can detect performance degradation as clinical populations and practices evolve over time [16]. As AI becomes increasingly integrated into healthcare and drug development, addressing these challenges will be essential for realizing the promise of equitable, clinically beneficial predictive analytics.

Advanced Techniques for Imbalanced Data: Sampling, Ensembles, and Multi-Label Learning

Ensemble methods represent a cornerstone of modern predictive modeling, where multiple machine learning models are combined to achieve superior performance over any single constituent model. Among these, Random Forest (RF) and Gradient Boosting (GB) stand as two of the most powerful and widely-adopted algorithms for structured data analysis. Their performance is critically evaluated within a broader research thesis focused on predictive performance across tree balance conditions, which examines how the structural properties of decision trees—such as depth, node purity, and symmetry—impact model robustness, accuracy, and generalization. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these nuances is essential for building reliable predictive models in high-stakes environments like clinical trial analysis or molecular property prediction.

This guide provides an objective comparison of these algorithms and their variants, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies, to inform model selection under various tree balance conditions and data complexities.

Theoretical Foundations of Ensemble Methods

Core Mechanisms: Bagging vs. Boosting

The fundamental difference between these ensemble techniques lies in their training methodology and how they combine weak learners (typically decision trees).

Bagging (Bootstrap Aggregating): This approach, exemplified by Random Forest, operates through parallel learning. It creates multiple bootstrap samples from the original dataset and trains a separate decision tree on each sample. The final prediction is formed by aggregating the predictions of all trees, typically through a majority vote for classification or averaging for regression. This process reduces variance and mitigates overfitting without increasing bias, making it particularly effective for high-variance base learners [20]. The "Random" in Random Forest adds further de-correlation by training each tree on a random subset of features at every split.

Boosting: In contrast, boosting is a sequential learning process where each new tree is trained to correct the errors made by the previous trees in the sequence. Algorithms like Gradient Boosting Machines (GBM) work by iteratively fitting new models to the residual errors of the current ensemble, gradually reducing overall bias [20]. This sequential error-correction often results in stronger predictive performance but requires careful tuning to prevent overfitting and manage computational costs [21].

The Role of Tree Balance in Ensemble Performance

Tree balance refers to the structural properties of the individual decision trees within an ensemble, including their depth, symmetry, and node purity. Under balanced tree conditions, where trees are fully grown with pure leaf nodes, models can capture complex interactions but risk overfitting. Imbalanced tree conditions, often resulting from pruning, depth constraints, or minimum sample requirements, create simpler models that may underfit but generalize better. The interplay between ensemble strategy (bagging vs. boosting) and tree balance critically determines overall model robustness, particularly in high-dimensional research domains like genomics and drug discovery.

Experimental Comparison of Algorithmic Performance

Performance Metrics Across Diverse Domains

Experimental data from multiple studies reveals how these algorithms perform under different conditions. The following table summarizes key performance metrics across various applications.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Ensemble Algorithms Across Different Domains

| Application Domain | Algorithm | Performance Metrics | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Dimensional Longitudinal Data [22] | Mixed-Effect Gradient Boosting (MEGB) | 35-76% lower MSE vs. alternatives | Superior for within-subject correlations & high-dimensional predictors (p=2000) |

| REEMForest | Reference for comparison | Outperformed by MEGB in complex dependency structures | |

| Airfoil Self-Noise Prediction [23] | Extremely Randomized Trees (Extra Trees) | Highest R² (Coefficient of Determination) | Best performance with reduced variance |

| Gradient Boost Regressor | Competitive R², lowest training time | Favored when computational efficiency is prioritized | |

| Carbonation Depth Prediction [24] | XGBoost | RMSE: 1.389 mm, MAE: 1.005 mm, R: 0.984 | Highest accuracy and reliability |

| CatBoost | RMSE: 1.772 mm, MAE: 1.344 mm, R: 0.976 | Strong performance, excels with categorical features | |

| LightGBM | RMSE: 1.797 mm, MAE: 1.296 mm, R: 0.975 | Fast training and high accuracy | |

| General Tabular Data Benchmark [25] | Gradient Boosting Machines (GBM) | N/A | Often matches or outperforms Deep Learning on structured data |

| Deep Learning Models | N/A | Does not consistently outperform GBMs on tabular data |

Computational Efficiency and Scalability

Beyond pure predictive accuracy, computational performance is a critical practical consideration. A comparative analysis of bagging and boosting revealed significant differences in their resource consumption profiles [21].

Table 2: Computational Cost Analysis: Bagging vs. Boosting

| Computational Factor | Bagging (e.g., Random Forest) | Boosting (e.g., GBM, XGBoost) |

|---|---|---|

| Training Time | Nearly constant with ensemble complexity | Increases sharply with ensemble complexity |

| Resource Consumption | Grows linearly with number of base learners | Grows quadratically with number of base learners |

| Parallelization | High - models are trained independently | Low - sequential training of base learners |

| Performance Trajectory | Diminishing returns, plateaus rapidly | Rapid early gains, risk of overfitting at high complexity |

| Best-Suited Context | Complex datasets, high-performance hardware | Simpler datasets, average-performing hardware |

The analysis found that with an ensemble complexity of 200 base learners, Boosting required approximately 14 times more computational time than Bagging, indicating substantially higher computational costs [21]. This makes Bagging generally more suitable when computational efficiency is critical, while Boosting may be preferred when maximizing predictive performance is the primary goal and sufficient resources are available.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide methodological context for the comparative data, this section outlines the key experimental protocols employed in the cited studies.

Protocol for High-Dimensional Longitudinal Data Analysis

The superior performance of Mixed-Effect Gradient Boosting (MEGB) was established through the following rigorous methodology [22]:

- Data Generation: Comprehensive simulations spanning both linear and nonlinear data-generating processes were conducted to evaluate algorithm performance under controlled conditions.

- Model Formulation: The MEGB model was specified as ( Y{ij} = f(X{ij}) + Z{ij} \varvec{b}i + \epsilon{ij} ), where ( f(X{ij}) ) represents the nonlinear fixed-effects function modeled via gradient boosting, ( Z{ij} \varvec{b}i ) captures subject-specific random effects, and ( \epsilon_{ij} ) represents residual error.

- Implementation: The iterative procedure in MEGB alternated between estimating the fixed effects function ( f(X_{ij}) ) using gradient boosting and updating random effects and variance components through the Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm.

- Evaluation Metrics: Performance was quantified using Mean Squared Error (MSE) for prediction accuracy and True Positive Rates for variable selection capability in ultra-high-dimensional regimes (p=2000).

- Competitor Benchmarks: MEGB was compared against state-of-the-art alternatives including Mixed-Effect Random Forests (MERF) and REEMForest.

Protocol for Airfoil Self-Noise Prediction

The comparison of Random Forest and Gradient Boosting variants for airfoil self-noise prediction followed this experimental design [23]:

- Dataset: The NASA airfoil self-noise dataset (NACA 0012) containing 1,503 entries with five input features (frequency, angle of attack, chord length, free-stream velocity, suction side displacement thickness) and one output variable (scaled sound pressure level).

- Preprocessing: Data randomization was performed to eliminate biases in the original data order, with no normalization applied due to the algorithms' robustness to feature scaling.

- Model Training: Multiple RF and GB models were evaluated using five-fold cross-validation to ensure reliable performance estimation.

- Evaluation Criteria: Models were assessed based on mean-squared error, coefficient of determination (R²), training time, and standard deviation across folds.

- Algorithms Compared: Included GB Regressor, XGBoost, LightGBM, and Extremely Randomized Trees (Extra Trees).

General Benchmarking Protocol for Tabular Data

The comprehensive benchmark evaluating machine and deep learning models on structured data employed the following methodology [25]:

- Dataset Selection: 111 diverse datasets with varying scales, including both regression and classification tasks, and both datasets with and without categorical variables.

- Model Variety: 20 different models were evaluated, including multiple Gradient Boosting variants and Deep Learning architectures.

- Statistical Testing: Performance differences were subjected to statistical significance testing to identify meaningful distinctions.

- Meta-Modeling: A predictive model was trained to characterize scenarios where Deep Learning models significantly outperform traditional methods, considering only datasets where performance differences were statistically significant.

Visualization of Ensemble Method Workflows

To enhance understanding of the logical relationships and experimental workflows in ensemble method research, the following diagrams provide visual representations of key concepts.

Ensemble Methods Decision Framework

Mixed-Effect Gradient Boosting (MEGB) Architecture

Successful implementation of ensemble methods in research environments requires both computational tools and methodological considerations. The following table details key solutions and their functions for researchers working with Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, and their variants.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Ensemble Methods

| Tool Category | Specific Solution | Function in Research Context |

|---|---|---|

| Software Libraries | Scikit-learn (Python) | Provides standardized implementations of Bagging, Random Forest, and Gradient Boosting with consistent APIs [20] |

| XGBoost, LightGBM, CatBoost | Optimized Gradient Boosting implementations with enhanced regularization, categorical feature handling, and training efficiency [24] | |

| Model Interpretation | SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | Quantifies feature importance and provides interpretable explanations for complex ensemble predictions [24] |

| Computational Resources | Multi-core CPU/Parallel Processing | Accelerates training of Bagging ensembles and certain Boosting variants through parallelization [23] |

| Methodological Frameworks | Mixed-Effect Gradient Boosting (MEGB) | Extends Gradient Boosting to hierarchical data structures with within-subject correlations [22] |

| Cross-Validation Protocols | (e.g., 5-fold) Provides robust performance estimation and guards against overfitting in high-dimensional settings [23] | |

| Data Preprocessing | SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Oversampling) | Addresses class imbalance in classification tasks before ensemble model training [26] |

| TF-IDF Feature Extraction | Transforms textual data for ensemble methods in natural language processing applications [26] |

This comparative analysis demonstrates that both Random Forest and Gradient Boosting offer distinct advantages for research applications, with their performance strongly mediated by tree balance conditions and data characteristics. Gradient Boosting variants generally achieve higher predictive accuracy on many tabular data problems, particularly when subtle signal detection is critical, as evidenced by their dominance in recent benchmarks [25] [24]. However, Random Forest provides superior computational efficiency and more robust performance under resource constraints or with highly complex datasets [21] [23].

The emerging class of specialized ensemble methods like Mixed-Effect Gradient Boosting (MEGB) addresses specific research challenges such as longitudinal data analysis, achieving 35-76% lower MSE compared to alternatives while maintaining robust variable selection capabilities [22]. For drug development professionals and researchers, selection between these algorithms should be guided by the specific data structure, computational resources, and analytical priorities of each investigation. Future research on tree balance conditions will continue to refine our understanding of how ensemble internal architectures influence their predictive robustness across different scientific domains.

In clinical practice, patients often present with multiple simultaneous conditions, complications, or diagnostic findings that cannot be adequately captured by single-label classification systems. Multi-label classification (MLC) has emerged as a critical machine learning framework for addressing this complexity, where each patient instance can be assigned multiple relevant labels simultaneously [27] [28]. This approach stands in stark contrast to traditional single-label classification, which forces an artificial choice between mutually exclusive diagnostic categories and fails to capture the rich correlations between co-occurring medical conditions [29].

The clinical relevance of MLC is particularly evident in complex diseases like diabetes, where patients frequently develop multiple complications that share underlying pathophysiological mechanisms [29]. Similarly, in tuberculosis treatment, resistance co-occurrence to first-line antibiotics is common due to standard combination regimens, creating natural label correlations that can be exploited for more accurate prediction [30]. These clinical realities have driven increased adoption of MLC approaches across diverse medical domains, from obstetric electronic medical records to surgical note classification and complication prediction in myocardial infarction [27] [28] [31].

Within the broader context of predictive performance evaluation across tree balance conditions research, MLC presents unique challenges and opportunities. The presence of severe class imbalance at multiple levels—within labels, between labels, and within label sets—requires specialized methodological approaches that differ significantly from single-label classification [27] [32]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of MLC methodologies, their performance characteristics, and implementation protocols to assist researchers in selecting appropriate approaches for clinical prediction tasks involving co-occurring conditions.

Performance Benchmarking: Comparative Analysis of Multi-Label Classification Methods

Quantitative Performance Metrics Across Methodologies

Evaluating MLC algorithms requires specialized metrics that account for their unique characteristics. The most comprehensive comparison to date analyzed 197 model configurations across 65 datasets using six different performance metrics [33]. The results demonstrated that optimal method selection is highly metric-dependent, with no single approach dominating across all evaluation criteria.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Multi-Label Classification Algorithms in Medical Applications

| Method | Application Context | Key Performance Metrics | Comparative Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ensemble Classifier Chains (ECC) | Diabetic complications prediction [29] | Hamming Loss: 0.1760, Accuracy: 0.7020, F1-Score: 0.7855 | Outperformed BR in most metrics; best overall performance |

| Multi-Label Random Forest (MLRF) | Tuberculosis drug resistance [30] | 18.10% improvement over clinical methods; 0.91% improvement over SLRF | Effectively leverages resistance co-occurrence patterns |

| Binary Relevance (BR) | Diabetic complications prediction [29] | Baseline performance | Simplicity but ignores label correlations |

| LLM (Llama 3.3) | Surgical note classification [31] | Micro F1-Score: 0.88, Hamming Loss: 0.11 | Superior to traditional NLP methods; handles context well |

| BP-MLL | Obstetric EMR diagnosis [28] | Average Precision: 0.7413 ± 0.0100 | Effective with topic model features in text classification |

The performance advantages of MLC are particularly pronounced in clinical contexts with strong label correlations. In diabetic complication prediction, Ensemble Classifier Chains significantly outperformed traditional Binary Relevance approaches across multiple metrics, demonstrating the value of leveraging inter-complication relationships [29]. Similarly, for tuberculosis drug resistance classification, Multi-Label Random Forest models achieved an 18.10% improvement over conventional clinical methods and a 0.91% improvement over single-label random forests by exploiting resistance co-occurrence patterns [30].

The Imbalance Challenge in Medical Multi-Label Classification

Medical datasets frequently exhibit severe class imbalance at three distinct levels, creating significant challenges for MLC implementation [27] [32]:

- Imbalance within labels: Disproportionate ratio of positive to negative samples for individual conditions

- Imbalance between labels: Significant frequency variation between different conditions

- Imbalance within label sets: Uneven distribution of label combinations

Advanced approaches like Non-Negative Least Squares (NNLS) resampling have demonstrated significant improvements in handling these imbalances, with one study reporting performance gains up to 94.84% recall, 94.60% F1-Score, and 0.0519 Hamming loss after balancing [32].

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Medical Multi-Label Classification

Data Preprocessing and Feature Engineering

Robust data preprocessing is essential for effective MLC in medical applications. The standard protocol begins with comprehensive data cleaning to address missing values, redundancy, and disorganization commonly found in real-world clinical datasets [28]. For biomedical datasets with missing values exceeding 85% in certain features, threshold-based exclusion is recommended followed by appropriate imputation strategies for remaining missing values [27].

Feature engineering approaches vary by data type. For structured clinical data, techniques include dummy coding of categorical variables, binary encoding for presence/absence indicators, and normalization of continuous laboratory values [27] [29]. For unstructured clinical text, such as obstetric electronic medical records, methods include latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA) topic modeling and word vector representations using the Skip-gram model [28].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Label Medical Classification

| Reagent Category | Specific Tools & Algorithms | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Problem Transformation Methods | Binary Relevance (BR), Classifier Chains (CC), Label Power Set (LP) | Transform MLC to binary classification or multi-class | General medical applications [29] |

| Algorithm Adaptation Methods | ML-kNN, ML-DT, Rank-SVM | Adapt standard algorithms to MLC | Medical text classification [29] |

| Ensemble Methods | Ensemble Classifier Chains (ECC), RAkEL, MLRF | Combine multiple models to improve performance | Diabetic complications, TB resistance [29] [30] |

| Feature Selection | Chi-square test, neighborhood rough sets | Dimensionality reduction, feature importance | Software defect prediction adapted for medical use [32] |

| Imbalance Handling | Non-Negative Least Squares (NNLS) | Address class imbalance in multi-label data | Medical datasets with rare conditions [32] |

| Language Models | Clinical-Longformer, Llama 3 | Text classification with contextual understanding | Surgical note classification [31] |

Model Selection and Training Protocols

The experimental workflow for medical MLC involves method selection based on label correlation structure, data characteristics, and performance requirements. The following diagram illustrates a standardized protocol for implementing multi-label classification in clinical contexts:

For clinical text classification, recent advances leverage large language models (LLMs) like Llama 3, which have demonstrated superior performance (micro F1-score: 0.88) compared to traditional NLP approaches such as bag-of-words (micro F1-score: 0.68) and encoder-only transformers like Clinical-Longformer (micro F1-score: 0.73) [31]. The implementation protocol includes 5-fold cross-validation with iterative stratification to maintain label distribution across splits, particularly important for addressing class imbalance [31].

Evaluation Metrics and Validation Approaches

Comprehensive evaluation of medical MLC requires multiple metrics capturing different aspects of performance [34] [33]:

- Example-based metrics: Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-Measure

- Label-based metrics: Macro/micro-averaged Precision, Recall, F1-Score

- Ranking metrics: Coverage, Ranking Loss, Average Precision

- Statistical metrics: Hamming Loss, Exact Match, Jaccard Index

Macro-averaging gives equal weight to each class, making it suitable for scenarios with important rare conditions, while micro-averaging gives equal weight to each instance, potentially dominated by frequent conditions [34]. For clinical applications, the F1-score provides a balanced metric that combines precision and recall, particularly valuable for imbalanced medical datasets [35].

Methodological Framework: Conceptual Structure of Multi-Label Medical Classification

The conceptual foundation of medical MLC rests on exploiting label correlations to improve prediction accuracy. This framework can be visualized through the following diagram illustrating the key methodological relationships:

The fundamental insight driving MLC performance improvements is the exploitation of clinical correlations between conditions. In diabetes, complications including retinopathy, nephropathy, and cardiovascular disease share common pathophysiological pathways, creating statistical dependencies that can be leveraged for more accurate prediction [29]. Similarly, in tuberculosis, specific mutations like katG_315 are associated with multi-drug resistance patterns, enabling more comprehensive resistance profiling when analyzed through an MLC framework [30].

Multi-label classification represents a paradigm shift in clinical predictive modeling, moving beyond artificial single-label constraints to embrace the complexity of co-occurring medical conditions. The experimental evidence demonstrates consistent performance advantages for MLC approaches across diverse medical domains, particularly when strong label correlations exist and are properly exploited through appropriate methodological choices.

The implementation of successful medical MLC requires careful attention to data preprocessing, imbalance handling, method selection based on label correlation structure, and comprehensive evaluation using multiple metrics. As clinical datasets continue to grow in size and complexity, MLC approaches will play an increasingly important role in enabling accurate, comprehensive clinical predictions that reflect the true complexity of patient presentations and disease interactions.

Solving Common Pitfalls: Overfitting, Interpretability, and Computational Efficiency

Diagnosing and Mitigating Overfitting in Complex Tree Ensembles

In the field of machine learning, tree ensemble models, such as Random Forests and Gradient Boosting Machines, have become a cornerstone for achieving state-of-the-art predictive performance on tabular data. Their effectiveness stems from a powerful ensemble mechanism that combines multiple individual decision trees to enhance model diversity and generalization capability [36]. However, this very complexity introduces a significant challenge: the propensity for overfitting. Overfitting occurs when a model learns the training data too well, capturing not only the underlying patterns but also the noise and random fluctuations specific to that dataset [37]. This results in a model that performs exceptionally well on its training data but fails to generalize effectively to new, unseen data [38].

For researchers and professionals in fields like drug development, where predictive models can inform critical decisions, understanding and controlling overfitting is not merely a technical exercise but a fundamental requirement for building reliable and trustworthy AI systems. An overfitted model in a clinical trial prediction task, for instance, could lead to costly missteps and inaccurate forecasts. This guide provides a comprehensive, objective comparison of diagnostic techniques and mitigation strategies for overfitting in complex tree ensembles, framed within the broader research context of evaluating predictive performance.

Diagnosing Overfitting in Tree Ensembles

Accurate diagnosis is the first critical step in addressing overfitting. The hallmark sign is a significant performance discrepancy between the training set and a validation or test set [37] [39]. A model that has memorized the training data will exhibit near-perfect training metrics but substantially worse performance on unseen data.

Key Diagnostic Indicators and Methodologies

The following experimental protocols are essential for a robust diagnosis:

Performance Gap Analysis: The primary diagnostic method involves partitioning the dataset into distinct training and validation/test sets. The model is trained exclusively on the training portion. Researchers then calculate key performance metrics—such as accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score—on both the training and held-out sets [40]. A large gap, where training performance is markedly higher than validation performance, is a clear indicator of overfitting [38]. For example, a decision tree might show a training accuracy of 96% but a test accuracy of only 75%, while a Random Forest ensemble on the same data might maintain a test accuracy of 85%, demonstrating better generalization [39].

Learning Curves: A more nuanced diagnostic involves plotting learning curves. This technique involves training the model on progressively larger subsets of the training data while evaluating performance on both the training and a fixed validation set at each step [37]. A model that is overfitting will typically show a validation error that decreases initially but then plateaus or even begins to increase, while the training error continues to decrease toward zero. This creates a persistent and growing gap between the two curves.

Analysis of Ensemble Complexity: The relationship between ensemble size (number of base trees) and performance is another key diagnostic. Research has shown that as the number of base learners (

m) increases, different ensemble methods behave differently. Bagging methods like Random Forest show a logarithmic performance improvement,P_G = ln(m+1), leading to stable, diminishing returns. In contrast, Boosting methods often follow a pattern likeP_T = ln(am+1) - bm^2, where performance can peak and then decline due to overfitting as the ensemble becomes too complex [21]. Monitoring performance on a validation set asmincreases is crucial for identifying this peak.

Comparative Analysis of Mitigation Strategies

A variety of strategies exist to mitigate overfitting in tree ensembles. The choice of strategy involves trade-offs between predictive performance, computational cost, and model interpretability. The experimental data summarized below is derived from benchmark studies on public datasets.

Performance and Resource Comparison

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Tree Ensemble Methods and a Single Decision Tree

| Model / Metric | Training Accuracy | Test Accuracy | Generalization Gap (Train - Test) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Decision Tree (Baseline) | 96% [39] | 75% [39] | 21% |

| Random Forest (Bagging) | 96% [39] | 85% [39] | 11% |

| Gradient Boosting | 100% [39] | 83% [39] | 17% |

| XGBoost (Boosting) | ~100% [41] | ~100% [41] (on Iris) | Minimal (on Iris) |

Table 2: Computational Cost and Complexity Trade-offs (Based on MNIST Dataset Experiments)

| Ensemble Method | Performance at m=200 | Comp. Time vs. Bagging | Performance Profile |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bagging (e.g., Random Forest) | 0.933 (plateaus) [21] | 1x (Baseline) | Stable, diminishing returns |

| Boosting (e.g., GBM, XGBoost) | 0.961 (can overfit) [21] | ~14x higher [21] | Higher peak performance, risk of overfitting |

Protocol for Mitigation Strategy Experiments

The comparative data in Tables 1 and 2 are typically derived from the following standardized experimental protocol:

- Dataset Selection: Use well-known public benchmarks (e.g., MNIST, CIFAR-10, Iris) or domain-specific datasets [21] [41].

- Data Preprocessing: Split data into training, validation, and test sets. Apply standard feature scaling or encoding as required.

- Baseline Establishment: Train a single decision tree with minimal constraints to establish an overfitting baseline [39].

- Ensemble Training: Train ensemble models (Bagging, Boosting) with controlled complexity. For complexity experiments, the number of base estimators (

m) is varied systematically while other hyperparameters are held constant [21]. - Evaluation: Models are evaluated on the held-out test set using accuracy, F1-score, or other relevant metrics. Computational time is also recorded.

- Analysis: Performance versus complexity curves are plotted, and generalization gaps are calculated to compare the effectiveness of different methods.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Methods and Reagents

Implementing effective tree ensemble models requires a suite of algorithmic strategies and software tools. The table below details the key "research reagents" for this domain.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Tree Ensemble Research

| Reagent / Technique | Type | Primary Function in Mitigating Overfitting |

|---|---|---|

| Bagging (Bootstrap Aggregating) | Algorithmic Strategy | Reduces variance by training diverse models on data subsets and averaging predictions [41] [21]. |

| Boosting (e.g., AdaBoost, XGBoost) | Algorithmic Strategy | Reduces bias by iteratively combining weak learners, focusing on misclassified instances [41] [21]. |

| Random Forest | Specific Algorithm | A Bagging variant that also randomizes features for each split, increasing model diversity and robustness [39]. |

| Regularization (L1/L2) | Parameter Tuning | Penalizes overly complex models by adding a cost for large weights, encouraging simpler solutions [37] [38]. |

| Early Stopping | Training Protocol | Halts the training process (e.g., in Boosting) once performance on a validation set stops improving [37] [38]. |

| Pruning | Model Simplification | Trims branches of decision trees that have little power in predicting the target, simplifying the model [37]. |

| Scikit-learn | Software Library | Offers a wide range of ensemble methods with built-in hyperparameters for regularization [41] [38]. |

| XGBoost | Software Library | Provides advanced boosting with hyperparameters like learning rate and max depth to control overfitting [41] [38]. |

| G3-C12 Tfa | G3-C12 Tfa, MF:C76H116F3N23O25S2, MW:1873.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Workflow for Diagnosis and Mitigation

The following diagram maps the logical workflow for systematically diagnosing and mitigating overfitting in a tree ensemble project. This process integrates the concepts and strategies discussed in the previous sections.

The management of overfitting is a fundamental aspect of developing robust tree ensemble models for scientific and industrial applications. As the comparative data shows, there is no single "best" algorithm; the choice is contextual. Bagging-based methods like Random Forest offer a compelling balance of strong performance, lower computational cost, and inherent resistance to overfitting, making them an excellent default starting point [21] [39]. In contrast, Boosting methods can achieve higher peak accuracy but demand careful regularization, hyperparameter tuning (e.g., learning rate, number of estimators), and validation to avoid overfitting, often at a significantly higher computational expense [21] [38].

The key to success lies in a rigorous, empirical approach. Researchers must employ systematic diagnostic protocols—such as performance gap analysis and learning curves—and be prepared to iterate through mitigation strategies. By leveraging the appropriate tools and strategies from the research toolkit and following a structured workflow, professionals can build tree ensemble models that not only perform well on historical data but also maintain their predictive power in real-world, dynamic environments like drug development.

Pruning and Regularization Techniques for Simpler, More Generalizable Models

In the field of machine learning, the pursuit of models that are both high-performing and efficient is a central challenge. As models grow in complexity to capture intricate patterns in data, they often become prone to overfitting, memorizing training data noise rather than learning generalizable patterns. This is particularly critical in research domains like drug development, where model interpretability and robustness are as important as predictive accuracy. Pruning and regularization emerge as essential techniques to address this, systematically reducing model complexity to enhance generalization. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these techniques, framing them within the critical research objective of evaluating predictive performance, especially under varied tree balance conditions. It offers researchers a detailed overview of methodological protocols, performance data, and essential tools for implementing these strategies effectively.

Understanding Pruning and Regularization

Core Concepts and Definitions

Pruning is a model compression technique that involves removing non-essential parameters from a neural network or simplifying the structure of a decision tree to reduce its size and computational demands [42]. The underlying principle is that neural networks are typically over-parameterized; they contain more connections than are strictly necessary for good performance [42]. Akin to the brain strengthening frequently used neural pathways while weakening others, pruning identifies and eliminates redundant parameters, leaving a leaner, more efficient architecture.

Regularization, in a broader sense, refers to any technique that prevents overfitting by discouraging a model from becoming overly complex. While pruning is a form of structural regularization, other common types include L1 regularization (Lasso), which encourages sparsity by driving some weights to zero, and L2 regularization (Ridge), which penalizes large weight magnitudes without necessarily making them zero.

The primary goal of both approaches is to improve a model's generalization—its ability to perform well on unseen data. For resource-constrained environments, such as edge devices in clinical settings or portable diagnostic tools, pruning is indispensable as it directly reduces model size, inference time, and energy consumption [43] [42].

A Taxonomy of Pruning Techniques

Pruning strategies can be categorized along several axes, each with distinct implications for the final model. The following diagram illustrates the key decision points and relationships in selecting a pruning strategy.

Train-Time vs. Post-Training Pruning: The most fundamental distinction lies in when pruning occurs. Train-time pruning integrates the pruning process directly into the model's training phase, encouraging sparsity as part of the optimization process [42]. This includes methods like L1 regularization and more advanced techniques like the Sparse Evolutionary Training (SET) method, which dynamically prunes and grows connections during training [43]. In contrast, post-training pruning is applied as a separate step after a model has been fully trained to convergence [42]. This approach allows for the immediate compression of existing models without altering the training pipeline.

Unstructured vs. Structured Pruning: This distinction defines the granularity of the pruning process. Unstructured pruning takes a fine-grained approach, removing individual weights within the model's layers based on a criterion like magnitude [42]. While this can lead to high levels of sparsity, it requires specialized software or hardware to realize inference speedups. Structured pruning, a more coarse-grained method, removes entire structural components like neurons, channels, or layers [42]. This leads to direct and hardware-agnostic improvements in inference speed and model size.

Local vs. Global Pruning: This defines the scope of the pruning decision. Local pruning applies a pruning criterion (e.g., removing the smallest 20% of weights) independently to each layer or module of the network [42]. Global pruning, by contrast, ranks all eligible weights across the entire model and removes the smallest ones globally [42]. Global pruning often produces better results because it has a more holistic view of the model's parameters.

Comparative Analysis of Pruning Techniques

Performance Across Model Architectures

The effectiveness of pruning varies significantly based on the model architecture, the chosen pruning method, and the target sparsity level. The following table summarizes experimental results from a comparative study on industrial applications, highlighting the trade-offs between accuracy, inference time, and energy consumption.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Pruning Methods on VGG16 and ResNet18 (BloodMNIST Dataset)

| Model | Pruning Method | Sparsity Level | Reported Accuracy (%) | Key Non-Functional Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VGG16 (Dense Baseline) | N/A | 0% (Dense) | ~84% [43] | Baseline for inference time and energy |

| VGG16 | SET (Train-Time) | 50% Conv, 80% Linear | ~86% [43] | Significant energy savings, maintained accuracy [43] |

| ResNet18 (Dense Baseline) | N/A | 0% (Dense) | ~85% [43] | Baseline for inference time and energy |

| ResNet18 | SET (Train-Time) | 50% Conv, 80% Linear | ~87% [43] | High efficiency, suitable for edge deployment [43] |

| ResNet18 | Post-Training Pruning | 50% Conv, 80% Linear | ~85% [43] | Reduced training complexity, potential for accuracy loss |

Table 2: Generic Effects of Increasing Post-Training Pruning Ratios

| Pruning Ratio | Model Size | Inference Speed | Typical Accuracy Impact | Ideal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (20-40%) | Slight Reduction | Slight Improvement | Minimal to no loss [42] | General purpose compression |

| Medium (40-60%) | Significant Reduction | Noticeable Improvement | Minor loss, often recoverable via fine-tuning [42] | Edge device deployment |

| High (60%+) | Drastic Reduction | Major Improvement | High risk of significant degradation [42] | Extreme resource constraints |

Key Insights from Data:

- The Sparse Evolutionary Training (SET) method demonstrates that it is possible to achieve energy savings without compromising accuracy, making it a highly attractive technique for industrial and edge applications [43].

- Post-training pruning offers a more accessible starting point but may involve a trade-off between the degree of compression and potential accuracy loss, which can sometimes be mitigated by fine-tuning the pruned model [42].

- The impact of pruning is model-dependent. For instance, some semantic segmentation models like UNet ResNet50 can maintain high performance even at high pruning ratios, while object detection models like YOLOv8 can be more sensitive [42].

Decision Tree Pruning: Pre-Pruning vs. Post-Pruning

For decision tree models, the pruning paradigm is often divided into pre-pruning and post-pruning.

Pre-Pruning (Early Stopping): This technique halts the growth of the tree during the building phase by setting constraints. Common parameters include

max_depth(limiting tree depth),min_samples_split(minimum samples required to split a node), andmin_impurity_decrease(setting a threshold for the minimum impurity reduction a split must achieve) [44]. Pre-pruning is generally considered more efficient for larger datasets [44].Post-Pruning: This method allows the tree to grow fully and then removes branches that do not provide significant predictive power. A common algorithm is Cost-Complexity Pruning (CCP), which assigns a cost to subtrees based on their accuracy and complexity, then selects the subtree with the lowest cost [44]. Post-pruning is often more effective for smaller datasets as it considers the full tree structure before simplifying [44].

Experimental comparisons show that while an unpruned tree might achieve an accuracy of ~88% on a sample dataset, post-pruning with CCP can increase accuracy to ~92% by reducing overfitting [44].

Specialized Pruning: The Case of Adversarial Robustness

A specialized category of pruning, known as Adversarial Pruning (AP), has emerged with the goal of compressing models while preserving or even enhancing their robustness against adversarial attacks—maliciously crafted inputs designed to cause misclassification [45]. These methods involve complex, robustness-oriented designs that integrate adversarial training into the pruning pipeline. A recent benchmark study re-evaluating various AP methods found that the top-performing techniques share common traits, such as iterative pruning schedules and robustness-aware scoring functions for weight importance [45]. This highlights that for security-sensitive applications in drug development (e.g., molecular property prediction), a specialized pruning approach is necessary.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Pruning Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)

This protocol outlines the steps for post-training and train-time pruning of CNNs like VGG16 and ResNet18, based on the methodology from the comparative study [43].

- Baseline Model Training: Train a standard, dense (unpruned) model on the target dataset (e.g., MedMNIST, BloodMNIST) to establish a baseline accuracy, inference time, and energy consumption profile.

- Pruning Strategy Selection: Choose a pruning method (e.g., SET for train-time, magnitude-based for post-training), define the granularity (unstructured/structured), and scope (local/global).

- Pruning Execution:

- For Post-Training Pruning: Apply the selected pruning algorithm to the pre-trained baseline model. A common approach is iterative magnitude pruning, where a small percentage of the smallest-magnitude weights are pruned, followed by fine-tuning, repeated over multiple cycles [42].

- For Train-Time Pruning (SET): Integrate pruning into the training loop. The SET method, for instance, initializes a sparse network and periodically removes the smallest weights and regenerates new connections in a data-dependent manner throughout training [43].

- Fine-Tuning (Post-Training Pruning): After pruning, the model's accuracy often drops. Fine-tune the pruned model on the training data for a few epochs to recover lost performance [42].

- Evaluation: Evaluate the final pruned model on a held-out test set. Metrics must include accuracy/F1-score, model size, inference latency, and, where possible, energy consumption during inference [43].

Protocol 2: Cost-Complexity Pruning for Decision Trees

This protocol details the process for post-pruning a decision tree using Cost-Complexity Pruning in Python with scikit-learn [44].

- Grow a Full Tree: Train a

DecisionTreeClassifierwithout restrictions to allow it to potentially overfit. - Compute CCP Path: Use the

cost_complexity_pruning_path(X_train, y_train)method on the fully grown tree. This returns a series of effective alphas (ccp_alphas), which are parameters that penalize tree complexity. - Train Trees for each Alpha: For each

ccp_alphain the path, train a new decision tree with theccp_alphaparameter set. This creates a sequence of progressively pruned trees. - Select the Best Tree: Evaluate the performance (e.g., accuracy or F1-score) of each tree in the sequence on a validation set or via cross-validation. The tree with the highest validation score is the optimally pruned model.

- Final Evaluation: Assess the performance of the selected pruned tree on the test set.

Implementing and experimenting with pruning requires a suite of software tools and benchmark datasets. The following table catalogs the essential "research reagents" for this field.

Table 3: Essential Tools and Datasets for Pruning Research

| Tool / Dataset Name | Type | Primary Function in Research | Relevance to Pruning Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| PyTorch / TensorFlow | Deep Learning Framework | Provides foundational APIs for model building, training, and inference. | Includes libraries (torch.nn.utils.prune) and patterns for implementing custom pruning logic. |

| scikit-learn | Machine Learning Library | Offers implementations of classic ML algorithms and utilities. | Provides decision tree pruning (CostComplexityPruner) and data preprocessing tools. |