tRNA Duplication: An Evolutionary Blueprint for Genetic Code Expansion and Therapeutic Development

This article explores the cutting-edge field of genetic code expansion (GCE) through the lens of tRNA gene duplication, an evolutionary mechanism now being harnessed for synthetic biology.

tRNA Duplication: An Evolutionary Blueprint for Genetic Code Expansion and Therapeutic Development

Abstract

This article explores the cutting-edge field of genetic code expansion (GCE) through the lens of tRNA gene duplication, an evolutionary mechanism now being harnessed for synthetic biology. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive analysis spanning from the foundational principles of tRNA biology and conservation to advanced methodologies for engineering orthogonal translation systems. We delve into critical troubleshooting strategies for optimizing incorporation efficiency and orthogonality, and present rigorous validation frameworks for assessing therapeutic potential. By synthesizing insights from evolutionary biology and modern engineering approaches, this review serves as a strategic guide for leveraging tRNA duplication to overcome the constraints of the canonical genetic code and develop novel biomedical tools and therapeutics.

The Evolutionary Foundation: How Natural tRNA Duplication Informs Synthetic Biology

Transfer RNA (tRNA) represents one of the most ancient biological molecules, often described as a "living fossil" that preserves primordial genetic coding mechanisms across all domains of life [1]. As an evolutionary ancient molecule, tRNA exhibits remarkable conservation in sequence and structure while maintaining its fundamental role in protein synthesis. The concept of tRNA as a living fossil reflects its persistence since the RNA world hypothesis, with contemporary tRNA-like structures providing clues to early evolutionary processes [2]. This conservation makes tRNA an invaluable subject for studying deep evolutionary relationships and developing tools for genetic code expansion.

The structural conservation of tRNA is particularly striking. All canonical tRNAs fold into a relatively rigid three-dimensional L-shaped structure through the formation of two orthogonal helices, consisting of the acceptor and anticodon domains [3]. This conserved tertiary organization arises through intramolecular interactions between the D- and T-arms, maintaining functional integrity across billions of years of evolution. Regardless of sequence variability, this architectural blueprint remains consistent, supporting tRNA's canonical function in translation while enabling its recruitment for non-canonical biological functions.

Quantitative Analysis of tRNA Conservation

Genome-Wide Conservation Patterns

Recent comparative genomics studies reveal profound conservation of tRNA genes across diverse species. A comprehensive analysis of 50 plant species identified 28,262 high-confidence tRNA genes encompassing eight divisions within the plant kingdom, demonstrating consistent patterns in gene length, intron distribution, and GC content [1]. The structural parameters of these tRNA genes show remarkable stability despite vast evolutionary distances between species.

Table 1: Conservation of tRNA Genes Across 50 Plant Species

| Genomic Feature | Conservation Range | Representative Examples | Evolutionary Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| tRNA Gene Length | 62-98 bp (peaking at 72 bp and 82 bp) | All angiosperms, bryophytes, chlorophytes | Highly constrained length distribution suggests structural optimization |

| GC Content | Variable but patterned | Consistent GC distribution patterns across species | Maintains structural stability and transcriptional efficiency |

| Intron Distribution | Ubiquitous in all species | tRNAMetCAT and tRNATyrGTC most abundant | Splicing mechanisms conserved across plant kingdom |

| Tandem Duplications | 578 identical tandemly duplicated pairs | Proline tRNA pairs in 33 species | Important evolutionary mechanism for tRNA gene expansion |

The abundance of tRNA genes shows surprising variation, ranging from just 56 in red algae (Pum) to 1,451 in Camelina sativa, with analysis revealing no significant correlation between tRNA gene number and genome size (r = 0.18, p = 0.21) [1]. This lack of correlation suggests that tRNA gene copy number is regulated by functional constraints rather than genome size dynamics, highlighting the specialized evolutionary pressures on this essential gene family.

Deep Evolutionary Conservation

The conservation of tRNA extends beyond plants to encompass all eukaryotic kingdoms. Evidence from mitochondrial genomes reveals that animal mtDNAs typically contain 22 tRNA genes as part of the conserved set of 37 mitochondrial genes [4]. This consistent gene complement in mitochondrial genomes, which are much diminished from their bacterial ancestors, underscores the essential nature of tRNA for organellar function.

The promoter architecture of tRNA genes reveals intriguing evolutionary patterns. Plant tRNA genes exhibit a highly conserved TATA motif followed by a CAA motif in their upstream regions, while animal tRNA upstream regions are highly heterogeneous and lack a common conserved sequence signature [5]. This fundamental difference in transcriptional regulation suggests divergent evolutionary paths in how tRNA gene expression is controlled across kingdoms, despite conservation of the genes themselves.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of tRNA Features Across Kingdoms

| Molecular Feature | Plant-Specific Patterns | Animal-Specific Patterns | Universal Conservation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upstream Promoter | Conserved TATA + CAA motif | Heterogeneous, anticodon-dependent motifs | Internal A and B box promoters |

| Tandem Duplications | Widespread (e.g., 27 tRNAPro in Arabidopsis) | Less common, more dispersed | Duplication as evolutionary mechanism |

| Isoacceptor Diversity | 49 distinct types for 22 amino acids | Similar diversity with tissue-specific expression | Consistent recognition of genetic code |

| tRNA-derived Fragments | Stress-responsive tsRNAs | Tissue-specific regulatory roles | Conservation of cleavage pathways |

Experimental Protocols for Studying tRNA Conservation and Duplication

Genome-Wide tRNA Gene Identification and Analysis

Protocol 1: Identification and Characterization of tRNA Genes

This protocol enables comprehensive annotation of tRNA genes across any genome, facilitating comparative analysis of conservation patterns.

Materials and Reagents:

- Nuclear genome sequence data in FASTA format

- tRNAscan-SE software (version 2.0.12 or higher)

- RNAFold for Minimum Free Energy (MFE) calculations

- VARNA GUI for secondary structure visualization

- R scripting environment with ggplot2 package

Methodology:

- Data Acquisition: Download nuclear genome sequences, coding sequences, and protein sequences from appropriate databases (e.g., Phytozome for plants)

- tRNA Gene Annotation: Execute tRNAscan-SE with eukaryotic parameters (

-Hand-yflags) followed by filtration for high-confidence sets using EukHighConfidenceFilter [1] - Structural Analysis: Calculate Minimum Fold Energy (MFE) for each identified tRNA gene using RNAFold to assess structural stability

- Sequence Alignment: Perform multiple sequence alignment of identical-sequence, intron-containing tRNA genes using multialin or similar tools

- GC Content Analysis: Calculate GC content using a sliding window approach (5 bp window, 1 bp step) with custom R scripts, normalizing against total tRNA gene length

- Phylogenetic Analysis: Cluster tRNA sequences using MMseqs2 with minimum sequence identity of 0.9 and coverage of 0.8, followed by phylogenetic tree construction with IQ-TREE 2 using best-fit models

Applications: This protocol successfully identified 28,262 tRNA genes across 50 plant species, revealing conservation in gene length (62-98 bp) and the presence of intron-containing genes in all species studied [1].

Identification of Tandem Duplication Events

Protocol 2: Analysis of Tandem tRNA Gene Duplications

Tandem duplication represents a fundamental evolutionary mechanism for tRNA gene expansion. This protocol details computational identification and characterization of these events.

Materials and Reagents:

- Genomic coordinates of annotated tRNA genes

- Custom scripts for genomic interval analysis (Python/R)

- Sequence alignment software (ClustalO)

- KaKs_Calculator 3.0 for evolutionary analysis

Methodology:

- Initial Identification: Scan genomic coordinates to identify tRNA gene pairs and clusters located on the same chromosome with physical distance less than 1 kb [1]

- Sequence Similarity Assessment: For clusters with sequence similarity below 100%, use unique tRNA gene sequences for further screening

- Cluster Definition: Define tandem repeats as clusters where different combinations of tRNA genes recur, and where tRNA genes sharing the same anticodon exhibit identical sequences

- Evolutionary Analysis: Calculate Kn/Ks ratios using KaKs_Calculator 3.0 to assess selective pressure on duplicated genes

- Classification: Categorize duplication types (double-, triple-, or quintuple-tRNA genes) and determine repetition frequency

Applications: Application of this protocol revealed 578 identical tandemly duplicated tRNA gene pairs grouped into 410 clusters across plant species, with proline tRNA pairs widely distributed in 33 species including both lower and higher plants [1].

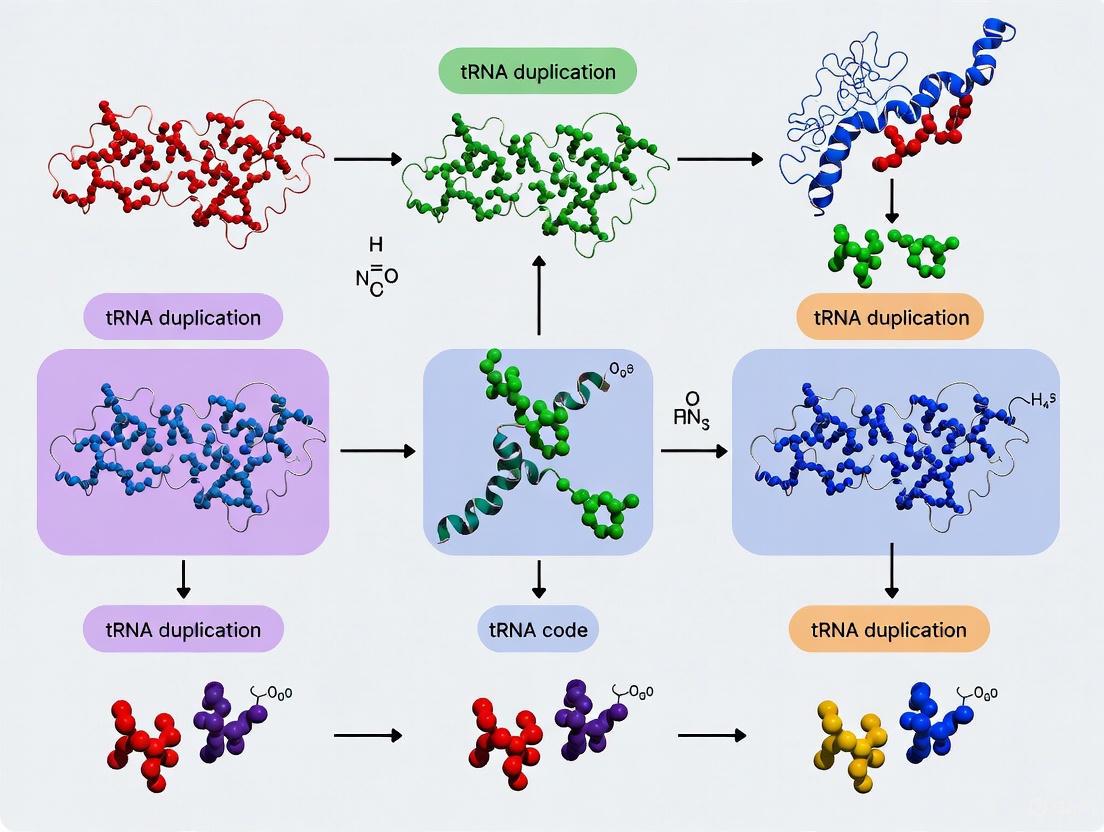

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for analyzing tRNA conservation and tandem duplications across genomes.

tRNA Engineering for Genetic Code Expansion

Structural Principles for tRNA Engineering

The highly conserved structure of tRNA provides both opportunities and challenges for genetic code expansion (GCE). Engineering tRNAs for GCE requires balancing orthogonality to host cell systems with cooperativity with translational machinery [6]. Successful engineering strategies focus on specific structural domains:

Acceptor Stem Engineering: Modifications to the acceptor stem (particularly positions 1-7 and 66-72) can enhance orthogonality by preventing recognition by endogenous aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (AARS). The discriminator base (position 73) serves as a key identity element for many AARS [6].

Anticodon Loop Modifications: Engineered alterations to the anticodon enable reassignment of stop codons or quadruplet codons to unnatural amino acids. Except for SerRS, AlaRS, LeuRS, and PylRS, most AARS utilize anticodon recognition [6].

Variable Loop Optimization: The variable loop exhibits significant length and composition variation across species, providing an engineering target for creating orthogonal tRNA/AARS pairs, particularly for seryl, phenylalanyl, and tyrosyl tRNAs [6].

Practical tRNA Engineering Protocol

Protocol 3: Engineering Orthogonal tRNA Systems for Genetic Code Expansion

This protocol details the development of orthogonal tRNA systems for incorporating unnatural amino acids into proteins.

Materials and Reagents:

- Host organism cell lines (E. coli, yeast, or mammalian)

- Orthogonal AARS/tRNA pairs from divergent organisms

- Plasmid vectors for tRNA expression

- Unnatural amino acids for incorporation

- Antibiotics for selection

- Western blot reagents for detection

Methodology:

- Orthogonal Pair Selection: Select AARS/tRNA pairs from organisms of different phyla than the host to maximize orthogonality (e.g., archaeal pairs in eukaryotic hosts) [6]

- tRNA Library Construction: Create mutant tRNA libraries focusing on acceptor stem, anticodon loop, and variable loop regions

- Screening for Orthogonality: Transform host cells with tRNA library and screen for absence of mis-incorporation of natural amino acids

- Efficiency Optimization: Select variants that maintain high charging efficiency by the cognate AARS while rejecting recognition by endogenous AARS

- Functional Validation: Assess incorporation efficiency of unnatural amino acids at amber stop codons or other reassigned codons

- Specificity Testing: Verify specific incorporation at target sites without global proteomic disruption

Applications: Engineered tRNA systems have enabled incorporation of over 150 unnatural amino acids with diverse chemical properties, expanding the functional repertoire of recombinant proteins for therapeutic and research applications [6].

Figure 2: tRNA engineering workflow for genetic code expansion applications, highlighting iterative optimization of orthogonality and efficiency.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for tRNA Conservation and Engineering Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioinformatics Tools | tRNAscan-SE, RNAFold, MMseqs2 | tRNA gene identification, structural prediction, sequence clustering | Specialized algorithms for non-coding RNA features |

| Evolutionary Analysis | KaKs_Calculator, IQ-TREE 2 | Selection pressure analysis, phylogenetic reconstruction | Handles specific evolutionary patterns of structural RNAs |

| Structural Analysis | VARNA GUI, PyMOL | Visualization of secondary and tertiary structures | Molecular graphics optimized for nucleic acids |

| Orthogonal Systems | Archaeal tRNA/AARS pairs, Pyrrolysyl system | Genetic code expansion foundation | Cross-kingdom incompatibility enables orthogonality |

| Expression Vectors | Amber suppressor tRNA plasmids, Inducible promoters | Controlled tRNA expression in host systems | Regulated expression critical for toxic variants |

| Detection Reagents | Northern blot probes, Antibodies against epitope tags | Validation of tRNA expression and aminoacylation | Specific detection challenging for mature tRNAs |

Evolutionary Perspectives and Emerging Applications

Deep Evolutionary Origins

The origin of tRNA predates the advent of templated protein synthesis, with evidence suggesting tRNA-like structures first functioned as "genomic tags" in RNA world replication [2]. These primordial tRNA ancestors marked the 3' ends of ancient RNA genomes for replication by RNA enzymes, solving both specificity and telomere maintenance problems. This evolutionary history explains the conserved involvement of contemporary tRNA-like structures in viral replication, such as in bacteriophage Qβ and brome mosaic virus [2].

The modular structure of modern tRNA supports this evolutionary model. The simplest early tRNA tags may have been predecessors of the "top half" of modern tRNA, consisting of a coaxial stack of the TΨC arm on the acceptor stem [2]. This evolutionary perspective informs engineering strategies that treat tRNA as a modular scaffold with evolutionarily distinct domains that can be independently optimized.

tRNA-Derived Fragments in Stress Response

Beyond their canonical role in translation, tRNAs serve as precursors for regulatory small RNAs known as tRNA-derived fragments (tRFs) or tRNA-derived small RNAs (tsRNAs) [7]. These molecules represent a novel category of gene expression regulators that function at both transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels.

In plants, specific tsRNAs show altered expression under diverse stress conditions including salt, drought, temperature extremes, and pathogen infection [7]. The biogenesis of these fragments involves cleavage by specific ribonucleases, with RNase T2 family proteins playing crucial roles in generating tRNA halves in Arabidopsis [7]. This emerging field reveals another dimension of tRNA evolutionary conservation, with the same ancient molecular scaffold being repurposed for regulatory functions across diverse lineages.

The deep conservation of tRNA as a living fossil provides both constraints and opportunities for genetic code expansion research. The highly conserved structural core enables predictive engineering based on evolutionary principles, while lineage-specific variations offer templates for developing orthogonal systems. The documented patterns of tRNA gene duplication and conservation across plants and animals [1] [4] inform strategies for optimizing tRNA copy number and expression in engineered systems.

Future directions include mining the expanding genomic resources from diverse species, particularly "living fossil" organisms like gymnosperms [8], to identify novel tRNA variants with unique properties. The evolutionary perspective on tRNA origins [2] suggests that engineering minimal tRNA scaffolds may yield efficient systems unburdened by evolutionary constraints of modern translational apparatus. Similarly, insights into how essential tRNA synthetases can evolve new functions [9] provide paradigms for directed evolution of orthogonal pairs.

The study of tRNA as a living fossil continues to yield fundamental insights into molecular evolution while providing practical tools for synthetic biology. By leveraging deep conservation patterns and understanding the exceptions to these patterns, researchers can develop increasingly sophisticated genetic code expansion systems with applications in therapeutic protein production, basic biological research, and understanding the fundamental constraints on the evolution of biological information processing.

Application Notes

Tandem duplication serves as a fundamental evolutionary mechanism driving genome plasticity and adaptation across plant species. This process, which generates tandem arrays of identical or similar sequences in close genomic proximity, occurs through unequal chromosomal recombination and represents a widespread phenomenon in plant genomes [10] [11]. Unlike whole-genome duplication events that affect all genes simultaneously, tandem duplication operates at a finer scale, producing significant gene copy number and allelic variation within populations [12]. Recent research has revealed that tandem duplication contributes substantially to the expansion of gene families, with approximately 4.74% to 14% of genes in various plant species classified as tandem duplicated genes (TDGs) [10] [12].

The evolutionary significance of TDGs is particularly evident in their functional bias toward environmental adaptation. Genes involved in stress responses show an elevated probability of retention following tandem duplication, suggesting these duplicates play crucial roles in adaptive evolution to rapidly changing environments [12]. This adaptive mechanism enables plants to develop enhanced resistance to both biotic and abiotic stressors, including pathogen attacks, salinity, and other environmental challenges [10] [13]. The lineage-specific nature of tandem duplication events further contributes to the diversification of plant species by creating genetic innovations that may be selectively advantageous in particular ecological niches.

Key Quantitative Findings from Cross-Species Analysis

Comprehensive analysis across multiple plant species has revealed striking patterns in TDG distribution and abundance. Table 1 summarizes the quantitative findings from genome-wide studies of tandem duplication events, highlighting species-specific variations that underscore the dynamic nature of plant genome evolution.

Table 1: Genome-Wide Tandem Duplication Patterns Across Plant Species

| Species | Genome Size | Total Genes | TDG Number | TDG Percentage | Key Enriched Functions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seashore Paspalum (Paspalum vaginatum) | 517.98 Mb | 28,712 | 2,542 | 8.85% | Ion transmembrane transport, ABC transport [10] |

| Pigeonpea (Cajanus cajan) | 833 Mb | 48,680 | 3,837 | 7.88% | Stress resistance pathways, retrotransposons [13] |

| Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) | 125 Mb | 35,386 | 3,503 | 9.90% | Environmental stress response, membrane functions [11] [12] |

| Rice (Oryza sativa) | ~400 Mb | Not specified | ~7.78% | ~7.78% | Stress tolerance, membrane functions [10] [11] |

| Maize (Zea mays) | ~2,400 Mb | Not specified | ~4.74% | ~4.74% | Stress tolerance, membrane functions [10] [11] |

| Foxtail Millet (Setaria italica) | ~490 Mb | Not specified | ~11.55% | ~11.55% | Stress tolerance, membrane functions [10] |

| Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) | ~730 Mb | Not specified | ~10.82% | ~10.82% | Stress tolerance, membrane functions [10] |

Analysis of 50 plant species spanning eight divisions within the plant kingdom (Angiospermae, Bryophyta, Chlorophyta, Lycopodiophyta, Marchantiophyta, Pinophyta, Pteridophyta, and Rhodophyta) has identified 28,262 high-confidence tRNA-coding genes, with abundance ranging from 56 in red algae (Pum) to 1,451 in Camelina sativa [1]. This substantial variation in tRNA gene number shows no significant correlation with genome size (r = 0.18, p = 0.21), suggesting specific evolutionary pressures rather than random expansion mechanisms [1].

A critical finding across studies is the functional enrichment of TDGs in stress response pathways. In seashore paspalum, TDGs show significant enrichment in Gene Ontology terms including "ion transmembrane transporter activity," "anion transmembrane transporter activity," and "cation transmembrane transport," along with KEGG pathways such as "ABC transport" [10]. Similarly, pigeonpea TDGs are significantly enriched in resistance-related pathways, indicating that stress resistance in this species may be ascribed to these pathways originating from tandem duplications [13].

tRNA Gene Duplication and Genetic Code Expansion

The conservation and tandem duplication of tRNA genes represents a particularly insightful model for understanding evolutionary mechanisms in plant genomes. Plant tRNA genes demonstrate remarkable conservation in terms of gene length (ranging from 62 to 98 bp), intron length, GC content, and sequence identity [1]. This conservation highlights the structural and functional constraints on these essential components of the translation machinery while allowing for evolutionary innovation through duplication events.

A comprehensive study identified 578 identical tandemly duplicated tRNA gene pairs grouped into 410 clusters, with some clusters containing up to 26 identical tRNA genes [1]. Different duplication patterns were observed, including double-, triple-, and quintuple-tRNA genes repeated for varying numbers of times. Notably, tandemly located tRNA gene pairs with anticodons to proline were widely distributed across 33 plant species, including both lower and higher plants, suggesting an evolutionarily conserved duplication mechanism with potential adaptive significance [1].

Table 2: tRNA Gene Duplication Patterns Across Plant Species

| Duplication Feature | Findings | Evolutionary Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Total tRNA Genes | 28,262 across 50 plant species | Essential translation components with high conservation [1] |

| Gene Length Range | 62-98 bp (peaking at 72 bp and 82 bp) | Structural constraints in secondary structure formation [1] |

| Tandem Duplication Events | 578 identical tandemly duplicated tRNA gene pairs grouped into 410 clusters | Mechanism for increasing dosage of specific tRNAs [1] |

| Maximum Cluster Size | Up to 26 identical tRNA genes | Potential for substantial changes in translation efficiency [1] |

| Conserved Anticodon Duplication | Proline anticodon tandems widespread in 33 species | Lineage-specific adaptation in translation machinery [1] |

| Duplication Types | Double-, triple-, and quintuple-tRNA gene repeats | Diverse evolutionary trajectories in different lineages [1] |

The expansion of tRNA genes through tandem duplication provides a mechanism for genetic code flexibility and potential expansion. According to the evolutionary trajectory hypothesis, the genetic code sectorized from a glycine code to 4 amino acid codes, then to 8 amino acid codes, then to 16 amino acid codes, and finally to the standard 20 amino acid codes with stops [1]. Tandem duplication of tRNA genes may represent a contemporary mechanism supporting this evolutionary trajectory, potentially enabling the incorporation of novel amino acids or the refinement of translation efficiency under specific environmental conditions.

Protocols

Genome-Wide Identification of Tandem Duplicated Genes

Principle: This protocol enables systematic identification and characterization of tandem duplicated genes (TDGs) from plant genome sequences using a combination of sequence similarity search and genomic location analysis [10] [11].

Materials:

- Plant genome sequence in FASTA format

- Genome annotation in GFF/GTF format

- Computing infrastructure with adequate storage and memory

- BLAST+ suite (v2.0 or higher)

- MCScanX software

- Perl and Python scripting environments

- R statistical platform with clusterProfiler package

Procedure:

Data Preparation

- Obtain protein sequence files and General Feature Format (GFF) files for the target species [10].

- For genes with multiple transcripts, select the longest transcript for subsequent analysis to ensure consistent comparison [10].

- Format the genome sequences and create BLAST databases using makeblastdb command.

Homologous Gene Identification

- Perform an all-against-all BLASTP search using protein sequences with an E-value cutoff of 1e-10 and retain the first 10 matches [10].

- Execute the following command:

Tandem Duplication Detection

Evolutionary Analysis

- Calculate non-synonymous (Ka) and synonymous (Ks) substitution rates for identified TDG pairs using ParaAT software [10].

- Compute approximate dates of duplication events using the formula T = Ks/2λ, where λ represents the clocklike rate of synonymous substitutions (typically 1.5 × 10⁻⁸ for plants) [10].

- Determine selection pressure by calculating Ka/Ks ratios for each gene pair.

Functional Enrichment Analysis

- Perform Gene Ontology (GO) and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis using the clusterProfiler R package [10].

- Calculate the "rich factor" as the ratio of the number of differentially expressed genes annotated in a term to the number of all genes annotated in that term.

- Apply false discovery rate (FDR) correction for multiple testing, with FDR ≤ 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If MCScanX produces insufficient TDG calls, adjust the BLASTP E-value threshold to 1e-5 to capture more distant homologs.

- For large genomes, consider parallelizing BLAST searches by chromosome.

- Verify ambiguous TDG calls by manually inspecting genomic coordinates in a genome browser.

Identification and Analysis of Tandemly Duplicated tRNA Genes

Principle: This protocol enables comprehensive identification and characterization of tandemly duplicated tRNA genes using specialized tRNA detection software and phylogenetic analysis [1].

Materials:

- Nuclear genome sequences of target plant species

- tRNAscan-SE software (v2.0.12 or higher)

- RNAfold software

- MMseqs2 software

- IQ-TREE (v2.0 or higher)

- KaKs_Calculator (v3.0)

- R software with ggplot2 and ComplexHeatmap packages

Procedure:

tRNA Gene Identification

Sequence and Structural Analysis

- Calculate GC content using a sliding window approach (5 bp window, 1 bp step) and normalize against total tRNA gene length [1].

- Generate fitting curves and confidence intervals for average GC content using the 'loess' method in ggplot2.

- Visualize secondary structures of representative tRNA genes using VARNA GUI [1].

Tandem Duplication Identification

- Identify tRNA gene pairs and clusters located on the same chromosome or scaffold with physical distance less than 1 kb [1].

- Define clusters where different combinations of tRNA genes recur, and where tRNA genes sharing the same anticodon exhibit identical sequences, as tandem repeats [1].

- Classify tandem arrays by repetition pattern (double-, triple-, or quintuple-tRNA genes).

Phylogenetic and Evolutionary Analysis

- Create a database of all tRNA genes using MMseqs2 createdb function [1].

- Cluster sequences with minimum sequence identity of 0.9 and coverage of 0.8.

- Perform multiple sequence alignment for tRNA genes with specific anticodons using clustalo.

- Identify best substitution models using ModelFinder in IQ-TREE.

- Construct phylogenetic trees with 1000 bootstrap replicates using the best-fit models [1].

- Calculate Kn/Ks ratios using KaKs_Calculator 3.0 with default parameters [1].

Comparative Genomics

- Statistically analyze the number of tRNA-coding genes with specific anticodons across species.

- Visualize results using heatmaps generated with ComplexHeatmap [1].

- Correlate tRNA abundance with genomic features such as genome size and codon usage bias.

Validation Methods:

- Verify tandem clusters by PCR amplification and Sanger sequencing of selected loci.

- Validate expression of duplicated tRNA genes using Northern blotting or RT-qPCR.

- Confirm structural predictions using chemical mapping or enzymatic probing for representative tRNAs.

Expression Analysis of Tandem Duplicated Genes Under Stress Conditions

Principle: This protocol assesses the expression patterns of TDGs in response to environmental stressors using RNA sequencing and differential expression analysis [10].

Materials:

- Plant materials subjected to stress treatments and controls

- RNA extraction kit with DNase treatment

- RNA quality assessment equipment (e.g., Bioanalyzer)

- Library preparation kit for RNA-seq

- High-throughput sequencing platform (e.g., Illumina HiSeq 2000)

- HISAT2 alignment software

- DESeq2 R package

- Computer with adequate RAM for processing large datasets

Procedure:

Experimental Design and Stress Treatment

- Grow plants under controlled conditions for two months [10].

- Apply stress treatment (e.g., 400 mM NaCl for salt stress) or mock treatment as control for varying durations (8, 12, 24, 48 hours, or 5 days) [10].

- Harvest tissues of interest with at least three biological replicates for each condition and time point.

RNA Sequencing

- Extract total RNA using quality-controlled methods ensuring RIN > 8.0.

- Prepare paired-end cDNA libraries using standard protocols.

- Sequence libraries on an appropriate platform (e.g., HiSeq 2000) to generate at least 20 million reads per sample [10].

Expression Quantification

- Align clean reads to the reference genome using HISAT2 with default parameters [10].

- Quantify gene expression levels using FPKM (fragments per kilobase per million mapped reads) or TPM (transcripts per million) values [10].

- Compile expression values into a count matrix for differential expression analysis.

Differential Expression Analysis

- Identify differentially expressed genes using DESeq2 with FDR ≤ 0.05 and |log2FC| ≥ 1 as significance thresholds [10].

- Classify tissue-specific expression patterns based on the following criteria:

Integration with TDG Data

- Overlap differentially expressed genes with previously identified TDGs.

- Perform functional enrichment analysis specifically on stress-responsive TDGs.

- Visualize expression patterns using heatmaps and cluster analysis.

Quality Control Measures:

- Monitor sequencing quality using FastQC.

- Remove low-quality reads and adapters using Trimmomatic or similar tools.

- Verify sample correlation through PCA and clustering analysis.

- Validate key findings using RT-qPCR on independent biological samples.

Visualization

Workflow for Genome-Wide Analysis of Tandem Duplicated Genes

Diagram 1: Comprehensive workflow for genome-wide identification and analysis of tandem duplicated genes in plant species.

Evolutionary Trajectory of Tandem Duplication in Plant Genomes

Diagram 2: Evolutionary pathways and fate of tandem duplicated genes in plant genomes under selective pressures.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for TDG Analysis

| Category | Tool/Reagent | Specific Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome Analysis Software | MCScanX | Detection and classification of tandem duplicated genes | Identifying TDGs from genomic sequences [10] |

| Sequence Alignment | BLAST+ Suite | Homology search and sequence similarity analysis | Identifying homologous gene pairs for TDG detection [10] |

| Evolutionary Analysis | ParaAT | Calculation of Ka/Ks ratios and divergence times | Estimating selection pressure and duplication timing [10] |

| tRNA Specialized Tools | tRNAscan-SE | Annotation of tRNA genes in genomic sequences | Identifying tRNA-coding genes and their locations [1] |

| Phylogenetic Analysis | IQ-TREE | Phylogenetic tree construction with model selection | Inferring evolutionary relationships of duplicated genes [1] |

| Expression Analysis | DESeq2 | Differential expression analysis of RNA-seq data | Identifying stress-responsive tandem duplicated genes [10] |

| Functional Enrichment | clusterProfiler | GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis | Determining functional biases in TDGs [10] |

| Sequence Clustering | MMseqs2 | Rapid clustering of large sequence datasets | Grouping related tRNA genes for duplication analysis [1] |

| Database Resources | PTGBase | Plant Tandem Duplicated Genes Database | Comparative analysis of TDGs across species [11] |

| Visualization | VARNA GUI | Visualization of RNA secondary structures | Examining structural features of duplicated tRNA genes [1] |

Within the broader framework of genetic code expansion (GCE) research, the duplication of transfer RNA (tRNA) genes presents a fundamental pathway for the evolution of novel translational components. Duplicated tRNA genes can serve as raw material for the development of orthogonal tRNA partners, which are crucial for incorporating unnatural amino acids (UAAs) into proteins [14]. The functional fate of duplicated genes is diverse; copies may be retained through subfunctionalization or neofunctionalization, or they may be lost [15]. A key conjecture in this field, the "least diverged ortholog" (LDO) conjecture, posits that following duplication, the copy that undergoes less sequence divergence is more likely to retain the ancestral function, while the more diverged copy (MDO) may acquire new, specialized roles [15]. Understanding the structural hallmarks of these duplicated genes—specifically their gene length, intron patterns, and GC content—is therefore not merely a descriptive exercise but a critical endeavor for rationally selecting and engineering tRNA duplicates for GCE applications. This Application Note provides detailed methodologies for the quantitative analysis of these structural features, equipping researchers with the tools to characterize and exploit tRNA gene duplications systematically.

Quantitative Analysis of Structural Hallmarks

The accurate quantification of tRNA pools, including duplicated genes, is hampered by technical challenges such as pervasive RNA modifications that block reverse transcription and the high sequence similarity among tRNA genes [16] [17]. The following methodologies are designed to overcome these hurdles and provide high-resolution data on tRNA abundance and sequence features.

Table 1: Key Methodologies for tRNA Abundance and Modification Profiling

| Method Name | Core Principle | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mim-tRNAseq [16] | Uses a thermostable group II intron reverse transcriptase (TGIRT) under optimized conditions for efficient readthrough of modified sites, capturing misincorporation signatures. | - Quantifying tRNA abundance- Profiling tRNA modification status- Assessing aminoacylation levels | - Applicable to any organism with a known genome- Captures abundance and modification data in one reaction- Full-length cDNA sequences | - Requires a comprehensive computational toolkit for analysis |

| Nano-tRNAseq [17] | Direct sequencing of native tRNA molecules using nanopore technology, with 5' and 3' adapter ligation to improve capture. | - Simultaneous quantification of tRNA abundance and modifications- Analysis of modification dynamics and crosstalk | - No reverse transcription or PCR bias- Detects modifications directly from native RNA- Single-molecule resolution | - Default sequencing settings can discard tRNA reads, requiring custom data reprocessing- Lower throughput compared to NGS |

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for tRNA Analysis

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Features / Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| TGIRT Enzyme [16] | Reverse transcriptase for mim-tRNAseq; enables readthrough of many Watson-Crick face tRNA modifications. | - High processivity- Template-switching capability- Optimal performance in low-salt buffers at 42°C |

| Barcoded DNA Adapters [16] | Ligation to tRNA 3' ends for library preparation; enables sample multiplexing. | - Designed to minimize co-folding with structured tRNAs- High ligation efficiency (89%–95%) |

| Orthogonal AARS/tRNA Pairs [14] | Core components for genetic code expansion; enable incorporation of unnatural amino acids. | - Must be orthogonal to host AARSs- Must function cooperatively with host translational machinery |

| tRNA Engineering Techniques [14] | Directed evolution and rational design to optimize tRNA orthogonality and efficiency in GCE. | - Targets interactions with AARS, EF-Tu, and the ribosome- Can alter identity elements and binding sites |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for mim-tRNAseq Library Construction and Analysis

This protocol is adapted from Behrens et al. (2021) for high-resolution quantitation of tRNA abundance and modification status, which is essential for characterizing duplicated genes [16].

I. tRNA Purification and 3' Adapter Ligation

- Purification: Isolate mature tRNA pools from total RNA by gel size selection for RNAs between 60–100 nucleotides.

- Adapter Ligation: Ligate barcoded DNA adapters to the 3' end of deacylated tRNAs using T4 RNA ligase 2. The adapter design should limit potential secondary structure formation with tRNA.

- Efficiency Check: Confirm ligation efficiency (typically 89-95%) by analytical gel electrophoresis.

II. Reverse Transcription with TGIRT

- Pooling: Pool samples ligated with different barcoded adapters.

- Primer Annealing: Anneal a primer complementary to the 3' adapter to the pooled tRNA.

- cDNA Synthesis: Perform reverse transcription using TGIRT enzyme in a low-salt buffer at 42°C for an extended reaction time (e.g., 3 hours) to nearly eliminate premature RT stops at modified nucleosides.

III. Library Completion and Sequencing

- cDNA Circularization: Circularize the synthesized cDNA. The primer for cDNA synthesis should contain a 5′ RN dinucleotide to facilitate this step.

- Amplification and Sequencing: Amplify the library and sequence using an Illumina platform.

IV. Computational Analysis

- Use the dedicated mim-tRNAseq computational toolkit for read alignment, which accounts for modification-induced misincorporations to accurately assign reads to highly similar tRNA genes, including duplicates.

- Analyze output data for tRNA abundance, modification sites (from misincorporation patterns), and isodecoder dynamics.

Protocol for Functional Interrogation of Duplicated tRNA Genes

This protocol outlines a computational and experimental workflow to determine the functional fate of duplicated tRNA genes, based on the LDO conjecture [15].

I. Sequence Divergence Analysis

- Identification: Identify tRNA gene duplicates from genomic databases (e.g., using tRNAscan-SE).

- Alignment: Perform multiple sequence alignment of the duplicated tRNA genes.

- Ancestral Reconstruction: Reconstruct the ancestral sequence and calculate the evolutionary rates (number of substitutions per site) for each duplicate.

- Classification: Classify duplicates as "Least Diverged" (LDO) or "Most Diverged" (MDO) based on their branch lengths from the ancestral node [15].

II. Structural and Expression Profiling

- Gene Architecture: Analyze the LDO and MDO for differences in:

- Gene Length: Note variations in the length of the variable arm.

- Intron Patterns: Identify the presence or absence of introns and their sequences.

- GC Content: Calculate the GC content, particularly in the acceptor stem and anticodon loop, as it can influence tRNA stability and interactions with the ribosome and elongation factors.

- Expression Correlation: Integrate the structural data with expression profiles (e.g., from mim-tRNAseq or Nano-tRNAseq) to determine if structural divergence correlates with functional specialization.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Visualization and Workflow

A core component of analyzing duplicated tRNA genes is a clear experimental workflow that integrates computational predictions with empirical validation. The diagram below outlines this logical pathway.

Diagram 1: Analysis of Duplicated tRNA Genes

The strategic analysis of structural hallmarks in duplicated tRNA genes—gene length, intron patterns, and GC content—provides a powerful foundation for advancing genetic code expansion research. By applying the detailed protocols for mim-tRNAseq and functional interrogation outlined in this document, researchers can move beyond simple sequence identification to a deeper understanding of the evolutionary forces shaping the tRNA repertoire. This enables the rational selection and engineering of specialized tRNAs from duplicated pairs, particularly the neofunctionalized MDOs, for developing highly efficient orthogonal translation systems. The integration of robust quantitative profiling, computational evolutionary analysis, and a clear understanding of tRNA structure-function relationships, as detailed in the provided toolkit and workflows, will accelerate the design of novel biologics and therapeutic agents through the site-specific incorporation of unnatural amino acids.

The evolution of the genetic code represents one of biology's most fundamental transitions, yet its origins remain actively debated. Contemporary research has undergone a paradigm shift from an mRNA-centric to a tRNA-centric model of code evolution, which posits that cloverleaf tRNA served as the molecular archetype around which translation systems evolved [18]. This framework suggests that the genetic code is a triplet code specifically because the structure of the tRNA anticodon loop forces a triplet register for two adjacent tRNAs paired to mRNA in the ribosome's decoding center [18]. The evolutionary trajectory proceeded from a primitive system utilizing a limited amino acid repertoire toward the complex modern code through mechanisms including tRNA gene duplication, anticodon modification, and functional specialization.

This application note situates the evolutionary trajectory of tRNA within the context of modern genetic code expansion research, providing researchers with both theoretical frameworks and practical methodologies for investigating and manipulating tRNA-based coding systems. We present quantitative analyses of tRNA gene conservation and duplication patterns across species, detailed protocols for experimental tRNA evolution, and visualization of key evolutionary and engineering concepts to facilitate research in synthetic biology and therapeutic development.

Evolutionary Foundations: From Proto-tRNA to Modern Diversity

The Proto-tRNA Hypothesis and Code Expansion

The polyglycine hypothesis proposes that the initial product of the genetic code may have been short-chain polyglycine synthesized to stabilize protocells [18]. Under this model, archaeal tRNAGly appears closest to the root of the tRNA evolutionary tree, suggesting that a primordial cloverleaf tRNA (tRNAPri) most strongly resembling tRNAGly diversified by mutation to include all permitted anticodons [18]. The initial 3-nucleotide code may have functioned primarily to synthesize short polyglycine chains (typically ~5 residues in length for structural stabilization), with translational processivity limited by primitive machinery [18].

Code expansion followed a sectoring-degeneracy hypothesis, whereby the code sectors from a 1→4→8→∼16 letter code [18]. At initial stages, strong positive selection existed for wobble base ambiguity, supporting convergence to 4-codon sectors and approximately 16 letters. Subsequently, approximately 5-6 additional letters, including stops, were added through innovation at the anticodon wobble position [18]. The initial expansion was physically constrained by negative selection against adenine in the tRNA wobble position, limiting the primordial code to approximately 48 anticodons rather than the full 64 potential codons [18].

Conserved Structural Transitions in tRNA Evolution

The evolutionary trajectory from proto-tRNA to modern diversity maintained remarkable structural conservation while permitting functional diversification. The cloverleaf tRNA structure is proposed to have evolved through a gradual, Fibonacci process-like elongation from a primordial coding triplet and 5'DCCA3' quadruplet to the eventual 76-90 base cloverleaf [19]. The conserved L-shaped tertiary structure comprises two functional branches: the acceptor branch (acceptor stem and T arm) where amino acids are charged, and the anticodon branch (D arm and anticodon arm) responsible for mRNA decoding [14].

Table 1: Evolutionary Trajectory of Genetic Code Expansion

| Evolutionary Phase | Amino Acid Diversity | tRNA Complexity | Key Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Glycine Phase | 1 amino acid (Glycine) | Single proto-tRNA species | Non-specific charging, polyglycine synthesis |

| Early Sectoring | 4 amino acids | Limited anticodon diversity | Wobble position ambiguity, initial duplication |

| Intermediate Expansion | 8-16 amino acids | Specialized isoacceptors | Anticodon modification, sectoring degeneracy |

| Modern Code | 20+ amino acids | Full isoacceptor/isodecoder families | tRNA gene duplication, synthetase coevolution |

Analysis of RNA secondary structures reveals an evolutionary axis from tRNA-like to rRNA-like configurations, with tRNA-like structures representing more primitive forms characterized by short RNAs with high proportions of external loops topping stems [20]. The relative similarity of tRNAs to this primitive structural class correlates with genetic code inclusion orders of tRNA cognate amino acids, confirming the biological relevance of this evolutionary axis [20].

Quantitative Analysis of tRNA Gene Evolution

Conservation and Duplication Patterns Across Species

Systematic analysis of tRNA genes across 50 plant species encompassing eight divisions within the plant kingdom reveals profound evolutionary conservation alongside dynamic duplication mechanisms [21]. A total of 28,262 high-confidence tRNA genes identified across these species demonstrate that tRNA gene abundance exhibits no significant correlation with genome size (r = 0.18, p = 0.21), indicating specific evolutionary pressures shaping tRNA copy number independent of general genome expansion [21].

Table 2: tRNA Gene Conservation and Duplication Across Phylogenetic Divisions

| Phylogenetic Division | Number of Species Analyzed | Total tRNA Genes Identified | Gene Length Range (bp) | Tandem Duplication Prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angiospermae | 36 | 14,827 | 62-98 | High (Proline anticodon clusters widespread) |

| Bryophyta | 4 | 3,215 | 70-92 | Moderate |

| Chlorophyta | 4 | 298 | 65-88 | Low |

| Lycopodiophyta | 2 | 537 | 68-90 | Moderate |

| Marchantiophyta | 1 | 824 | 71-95 | High |

| Pinophyta | 1 | 387 | 69-89 | Moderate |

| Pteridophyta | 1 | 483 | 67-91 | Moderate |

| Rhodophyta | 1 | 56 | 62-79 | Minimal |

Identical tandemly duplicated tRNA gene pairs are abundant across plant species, with 578 identified pairs grouped into 410 clusters containing up to 26 identical tRNA genes [21]. Different duplication types include double-, triple-, and quintuple-tRNA genes repeated variably, with tandemly located tRNA gene pairs with anticodons to proline widespread in 33 plant species across both lower and higher plants [21].

Experimental Evolution of tRNA Genes

Landmark experimental evolution studies in Saccharomyces cerevisiae demonstrate the rapid adaptive capacity of tRNA genes when faced with novel translational demands [22]. Deletion of the single-copy tRNA gene decoding the AGG arginine codon initially reduced fitness, but evolved populations recovered wild-type growth rates after ~200 generations through a strategic mutation that changed the anticodon of another tRNA gene (normally decoding AGA arginine) to match the deleted AGG anticodon [22].

This anticodon switching mechanism represents a fundamental evolutionary strategy for adapting the tRNA pool to meet novel translational demands. Computational analysis of hundreds of genomes confirms that anticodon mutations occur throughout the tree of life, indicating this represents a general adaptive mechanism rather than a laboratory-specific phenomenon [22]. Beyond meeting translational demand, the evolution of tRNA pools is also constrained by the need to properly couple translation to protein folding, maintaining deliberately suboptimal "slow codons" at domain boundaries to facilitate proper cotranslational folding [22].

Experimental Protocols for tRNA Evolution Studies

Protocol: Experimental Evolution of tRNA Gene Function

This protocol adapts methodology from Yona et al. (2013) for investigating tRNA gene evolution in response to gene deletions or novel translational demands [22].

Materials and Reagents

- Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain with deletion of specific tRNA gene (e.g., ΔtRNA-AGG-Arg)

- Appropriate rich and selective media (YPD, SC)

- Chemostat or serial transfer apparatus

- DNA extraction kit

- PCR reagents

- tRNA-specific sequencing primers

- Computational resources for genome analysis

Procedure

- Strain Construction: Delete target tRNA gene (e.g., tRNA-AGG-Arg) from S. cerevisiae genome using standard gene replacement techniques.

- Evolution Initiation: Inoculate mutant strain into appropriate medium and initiate evolution under either:

- Chemostat conditions: Maintain continuous culture for 200+ generations

- Serial transfer: Dilute 1:100 into fresh medium daily for 200+ generations

- Fitness Monitoring: Sample populations every 20 generations to assess growth rates relative to wild-type

- Genomic Analysis: Extract genomic DNA from evolved populations showing fitness recovery

- tRNA Gene Sequencing: Amplify and sequence all tRNA genes with anticodons cognate to deleted tRNA

- Variant Identification: Identify anticodon mutations and validate causative mutations through reconstruction

Applications and Limitations This approach directly demonstrates how tRNA gene families evolve to meet translational demands but requires specialized expertise in microbial evolution and may produce strain-specific findings.

Protocol: Identification and Analysis of Tandem tRNA Duplications

This protocol describes bioinformatic identification and analysis of tandem tRNA gene duplications from genomic data, based on methods from plant tRNA genomics studies [21].

Materials and Reagents

- Genomic sequences in FASTA format

- High-performance computing cluster

- tRNAscan-SE software (v2.0.12)

- MMseqs2 for sequence clustering

- R scripting environment with ggplot2, ComplexHeatmap

- IQ-TREE for phylogenetic analysis

Procedure

- tRNA Gene Identification:

- Annotate tRNA genes using tRNAscan-SE with eukaryotic parameters:

tRNAscan-SE -H -y genome.fasta - Filter for high-confidence sets using EukHighConfidenceFilter

- Annotate tRNA genes using tRNAscan-SE with eukaryotic parameters:

Tandem Duplication Identification:

- Identify tRNA genes located on same chromosome with <1 kb intergenic distance

- Calculate sequence identity for proximal genes using Needle alignment

- Define tandem duplicates as genes with >90% sequence identity and >80% coverage

Sequence and Evolutionary Analysis:

- Calculate GC content using 5bp sliding windows normalized against total tRNA length

- Perform multiple sequence alignment using clustalo

- Construct phylogenetic trees using IQ-TREE with best-fit models identified by ModelFinder

- Calculate Kn/Ks ratios using KaKs_Calculator 3.0 with default parameters

Visualization and Interpretation:

- Generate heatmaps of tRNA abundance by anticodon across species

- Plot GC content variation across tRNA structures

- Visualize phylogenetic relationships of tandem duplicates

Applications and Limitations This protocol enables systematic comparison of tRNA gene evolution across species but requires quality genome assemblies and may miss evolutionarily recent duplicates under annotation thresholds.

Visualization of Evolutionary and Engineering Concepts

Evolutionary Trajectory of tRNA Gene Function

Evolution of tRNA Gene Function

tRNA Engineering Workflow

tRNA Engineering Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions for Genetic Code Expansion

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for tRNA and Genetic Code Expansion Studies

| Reagent/Category | Function/Application | Key Characteristics | Experimental Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Orthogonal tRNA/synthetase Pairs | Genetic code expansion with unnatural amino acids | Species-cross reactive, non-immunogenic to host AARS | Requires directed evolution for orthogonality and efficiency |

| tRNA Gene Deletion Strains | Studying tRNA evolution and essentiality | Single-copy tRNA gene deletions in model organisms | Fitness defects often observed; enables experimental evolution |

| tRNAscan-SE Software | Bioinformatics annotation of tRNA genes | Covariance model-based prediction, cloverleaf scoring | Standard for genomic tRNA identification; requires parameter optimization |

| Directed Evolution Systems | tRNA engineering for improved function | Library generation, orthogonality selection | Critical for optimizing tRNA efficiency in non-native hosts |

| Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetase Libraries | Expanding substrate specificity | Mutant libraries for novel amino acid incorporation | Enables genetic code expansion to non-canonical amino acids |

The evolutionary trajectory from proto-tRNA to modern diversity reveals fundamental principles governing genetic code expansion and adaptability. The documented mechanisms of tandem gene duplication, anticodon switching, and structural conservation provide both explanatory power for natural code evolution and engineering strategies for synthetic biology applications. The experimental and computational protocols presented here enable researchers to directly investigate tRNA evolution and harness these principles for genetic code expansion.

For drug development professionals, these insights facilitate engineering of novel tRNA-based therapeutics and optimization of heterologous protein expression systems. The conservation of tRNA duplication mechanisms across the tree of life suggests generalizable approaches to manipulating translational systems for industrial and therapeutic applications, including readthrough of disease-causing nonsense mutations and incorporation of novel amino acids for biologics engineering.

Transfer RNA (tRNA) serves as the fundamental molecular bridge that translates genetic code into functional proteins. The conserved functional modules of tRNA—specifically the acceptor stem and anticodon loop—work in concert with specific identity elements to ensure the fidelity and efficiency of protein synthesis. Within the context of genetic code expansion (GCE), these modules provide both a framework of natural constraints and a platform for engineering. GCE technologies aim to incorporate non-canonical amino acids (ncAAs) into proteins, requiring the development of orthogonal translation systems (OTSs) that function outside the natural machinery while adhering to its core principles [23]. Research into tRNA gene duplication events reveals an evolutionary pathway that has diversified the tRNA repertoire while conserving these critical functional modules, offering valuable insights for synthetic biology [21]. This application note provides a detailed analysis of these modules, supported by quantitative data and experimental protocols, to facilitate advanced research in genetic code expansion.

Quantitative Analysis of Conserved tRNA Modules

Genome-Wide tRNA Gene Conservation

A comprehensive analysis of 50 plant species identified 28,262 high-confidence tRNA genes, revealing significant conservation across the plant kingdom. The abundance of tRNA genes showed a weak, non-significant correlation with genome size (r = 0.18, p > 0.05), indicating that factors beyond genome scale govern tRNA gene copy number [21]. The study also documented 578 identical tandemly duplicated tRNA gene pairs, grouped into 410 clusters, with some clusters containing up to 26 repeated tRNA genes. These duplication events were observed across both lower and higher plants, suggesting tandem duplication serves as a fundamental evolutionary mechanism for tRNA gene family expansion [21].

Table 1: Conservation of Intron-Containing tRNA Genes and Tandem Duplication Events in Plants

| Analysis Category | Findings | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Total tRNA Genes Identified | 28,262 genes across 50 plant species | Demonstrates widespread presence and conservation [21] |

| Gene Length Conservation | Ranged from 62 to 98 bp, peaking at 72 bp and 82 bp | Indicates strong structural conservation [21] |

| Abundant Intron-Containing tRNAs | tRNAMet_CAT and tRNATyr_GTC were most abundant | Specific tRNA families are consistently intron-containing [21] |

| Tandem Duplication Events | 578 identical tandemly duplicated tRNA gene pairs (410 clusters) | Tandem duplication is a key evolutionary driver [21] |

| Widespread Tandem Duplication | tRNAPro anticodon pairs found in 33 species | Highlights a conserved duplication event [21] |

Functional Coding of Acceptor Stems and Anticodon Loops

The acceptor stem and anticodon loop encode distinct physicochemical properties of amino acids, implementing a dual-level proofreading system. Research demonstrates that the anticodon primarily encodes the hydrophobicity of the amino acid side-chain, represented by its water-to-cyclohexane distribution coefficient (ΔGw>c) [24]. In contrast, the acceptor stem codes preferentially for the size or surface area of the side-chain, as represented by its vapor-to-cyclohexane distribution coefficient (ΔGv>c) [24]. These orthogonal properties are both necessary to satisfactorily account for the exposed surface area of amino acids in folded proteins. Furthermore, the acceptor stem correctly codes for β-branched and carboxylic acid side-chains, while the anticodon codes for a wider range of properties but not for size or β-branching [24].

Table 2: Functional Coding Properties of tRNA Modules

| tRNA Module | Encoded Amino Acid Property | Experimental Measure | Contribution to Protein Folding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acceptor Stem | Side-chain size / Surface area | Vapor-to-cyclohexane transfer equilibrium (ΔGv>c) | Determines van der Waals contacts in folded state [24] |

| Anticodon Loop | Side-chain hydrophobicity / Polarity | Water-to-cyclohexane transfer equilibrium (ΔGw>c) | Governs hydrophilic character and solvent interaction [24] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Genome-Wide Identification and Analysis of tRNA Genes

Objective: To identify tRNA genes, characterize their structural features, and detect duplication events in genomic sequences.

Materials:

- Nuclear genome sequences in FASTA format

- tRNAscan-SE software (v2.0.12 or higher)

- RNAFold software

- Computing environment with R and ggplot2 package

- MMseqs2 software for sequence clustering

Procedure:

- Data Acquisition: Download nuclear genome sequences, coding sequences, and protein sequences for target species from databases such as Phytozome [21].

- tRNA Gene Identification: Annotate tRNA genes using tRNAscan-SE with parameters "-H" and "-y" optimized for eukaryotic tRNAs. Filter results for high-confidence sets using EukHighConfidenceFilter [21].

- Structural Characterization:

- Sequence Conservation Analysis:

- Perform multiple sequence alignment of identical-sequence tRNA genes using Multialin or similar tools.

- Calculate sequence identity between tRNA gene pairs using global alignment tools such as Needle [21].

- Estimate non-synonymous (Kn) and synonymous (Ks) substitution rates using KaKs_Calculator 3.0 to evaluate evolutionary pressure [21].

- Phylogenetic Analysis:

- Cluster tRNA sequences using MMseqs2 with a minimum sequence identity of 0.9 and coverage of 0.8.

- Construct phylogenetic trees using IQ-TREE 2 with appropriate substitution models and 1000 bootstrap replicates [21].

- Tandem Duplication Detection:

- Identify tRNA gene pairs and clusters located on the same chromosome with a physical distance of less than 1 kb.

- Define tandem repeats as clusters where tRNA genes with the same anticodon exhibit identical sequences or where different combinations of tRNA genes recur [21].

Protocol 2: Analyzing Identity Elements and Editing Mechanisms

Objective: To characterize tRNA identity elements and their role in aminoacylation fidelity and editing.

Materials:

- Purified aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (ARSs) and editing enzymes

- In vitro transcription system for tRNA variants

- Radiolabeled or fluorescent-labeled amino acids

- HPLC system with appropriate columns

- Stop-flow quenching instruments for kinetic assays

Procedure:

- tRNA Variant Design: Design tRNA mutants with systematic alterations at known identity element positions (e.g., positions 1, 72, 73 in the acceptor stem; positions 34, 35, 36 in the anticodon loop) [25].

- In Vitro Aminoacylation Assays:

- Charge wild-type and mutant tRNAs with cognate and non-cognate amino acids using purified ARSs.

- Quantify aminoacylation efficiency and mischarging rates using radiolabeled amino acids or other detection methods [25].

- Editing Assay Setup:

- Incubate mischarged tRNAs with cis-editing domains of ARSs or trans-editing enzymes.

- Monitor deacylation kinetics using stop-flow quenching techniques or HPLC to separate aminoacyl-tRNAs from free amino acids [25].

- Specificity Determination:

- Compare editing rates for cognate versus non-cognate aa-tRNAs.

- Identify specific tRNA identity elements recognized by editing domains through kinetic analysis of mutants [25].

- Data Analysis: Calculate kinetic parameters (kcat, KM) for both aminoacylation and editing reactions to determine how identity elements contribute to overall fidelity.

Protocol 3: tRNA Engineering for Genetic Code Expansion

Objective: To engineer orthogonal tRNA/synthetase pairs for incorporation of non-canonical amino acids.

Materials:

- Library of tRNA variants (e.g., with mutations in anticodon stem-loop)

- Orthogonal aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase (aaRS) library

- Non-canonical amino acid of interest

- Reporter plasmid with target codon (e.g., amber stop codon UAG)

- Host cells (E. coli, yeast, or mammalian cells)

- Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) equipment

Procedure:

- tRNA Library Construction: Create a diverse library of orthogonal tRNA variants (e.g., pyrrolysyl-tRNA) with randomized mutations in the anticodon stem-loop region to recognize non-standard codons [26].

- Selection System Setup: Co-express the tRNA library with a cognate aaRS library and a reporter gene containing the target codon (e.g., Ψ-modified stop codon for RCE systems) [26].

- High-Throughput Screening:

- For efficiency screening: Use fluorescent reporter genes (e.g., GFP) whose full-length production depends on successful ncAA incorporation at the target codon. Sort high-efficiency clones via FACS [23].

- For orthogonality screening: Use negative selection markers (e.g., toxin genes) to eliminate clones with cross-reactivity to endogenous amino acids or tRNAs [23].

- Characterization of Engineered Pairs:

- Measure ncAA incorporation efficiency and fidelity using western blotting and mass spectrometry.

- Assess protein yields and incorporation accuracy at multi-site locations [6].

- System Optimization: Iteratively evolve both tRNA and synthetase components to improve orthogonality, efficiency, and specificity for the desired ncAA [6].

Visualizing tRNA Modules and Experimental Workflows

Diagram 1: Integrated workflow for analyzing conserved tRNA modules and engineering for genetic code expansion.

Diagram 2: Functional modules of tRNA and their interaction with cellular machinery, highlighting key identity elements.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for tRNA and Genetic Code Expansion Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Bioinformatics Tools | tRNAscan-SE, RNAFold, MMseqs2, KaKs_Calculator, IQ-TREE 2 | tRNA gene identification, structural prediction, evolutionary analysis [21] |

| Orthogonal tRNA/synthetase Pairs | Pyrrolysyl-tRNA/synthetase pair, Engineered M. jannaschii tyrosyl pair | Core components for genetic code expansion and ncAA incorporation [23] [26] |

| Non-Canonical Amino Acids | Photo-crosslinkers, Bio-orthogonal handles (azides, alkynes), Fluorescent analogs | Expanding chemical functionality of synthesized proteins [23] |

| Selection & Screening Systems | GFP-based reporters, Toxin counter-selection, FACS, Compartmentalized partnered replication | High-throughput identification of efficient orthogonal systems [23] |

| In Vitro Translation Systems | PURE system (Reconstituted E. coli components), Cell lysates | Flexible genetic code reprogramming without cellular constraints [23] |

| Analytical Techniques | HPLC-MS for modified nucleosides, NMR, X-ray crystallography | Quantifying tRNA modifications and determining 3D structures [27] [25] |

Engineering the Code: Methodologies for Harnessing tRNA Duplication in GCE

Genetic Code Expansion (GCE) technology enables the site-specific incorporation of non-canonical amino acids (ncAAs) into proteins, thereby overcoming the limitations of the standard genetic code and creating novel protein functions and properties [6] [14]. This technique has matured into a versatile tool with applications across protein science, therapeutic engineering, and synthetic biology [28]. At the heart of every GCE system lies the orthogonal aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase/tRNA pair (aaRS/tRNA), a fundamental component that acts as an autonomous translation system within the host organism [28] [29]. For successful GCE, this pair must function without cross-reacting with the host's native translational machinery; the orthogonal aaRS must specifically charge the ncAA onto its cognate orthogonal tRNA, which in turn must be aminoacylated only by its orthogonal partner and not by any endogenous host aaRSs [6] [30]. The tRNA must also specifically recognize a "blank" codon—most commonly the amber stop codon (UAG)—that is not assigned to a canonical amino acid [28]. The strategic sourcing and engineering of these pairs from diverse biological origins are therefore critical for expanding the scope and efficiency of GCE.

Sourcing Orthogonal Pairs from Nature

Orthogonal aaRS/tRNA pairs are typically sourced from organisms across different phylogenetic domains to ensure they do not cross-talk with the host's native translation systems [6] [14]. The underlying principle is that aaRS/tRNA pairs from distantly related species (e.g., archaea transplanted into bacteria) have evolved distinct identity elements, making them functionally independent in the new host environment [31] [29].

Table 1: Naturally Sourced Orthogonal aaRS/tRNA Pairs and Their Applications

| Orthogonal Pair | Organism of Origin | Common Hosts | Key Features and Applications | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pyrolysyl-tRNA Synthetase/tRNAPyl (PylRS/tRNAPyl) | Methanosarcina species (e.g., barkeri, mazei) | E. coli, Yeast, Mammalian Cells | - Naturally incorporates pyrrolysine [29].- Extremely versatile substrate specificity [28].- Used to incorporate >200 distinct ncAAs [28]. | [28] [29] [30] |

| Tyrosyl-tRNA Synthetase/tRNATyr (TyrRS/tRNATyr) | Methanocaldococcus jannaschii (Mj) | E. coli | - One of the first pairs developed for GCE [29].- Used to incorporate various phenylalanine and tyrosine analogs [29]. | [31] [29] |

| Tyrosyl-tRNA Synthetase/tRNATyr (TyrRS/tRNATyr) | E. coli | Yeast, Mammalian Cells | - Demonstrates orthogonality in eukaryotic hosts [29].- Bacterial identity elements differ from eukaryotic counterparts. | [29] |

| Tyrosyl-tRNA Synthetase/tRNATyr (TyrRS/tRNATyr) | Methanosaeta concilii (Mc) | E. coli | - A newly developed pair for incorporating para-azido-L-phenylalanine (AzF) [30].- Broadens the pool of available orthogonal pairs. | [30] |

The PylRS/tRNAPyl pair is exceptionally prominent in GCE due to its unique natural function and remarkable plasticity. It was originally discovered in methanogenic archaea, where it charges the rare amino acid pyrrolysine into proteins in response to an in-frame amber codon [29]. Its versatility and high orthogonality across diverse hosts, from bacteria to mammalian cells, have made it a cornerstone for incorporating a vast range of ncAAs [28] [29].

Experimental Protocol: Establishing and Validating Orthogonality

This protocol outlines the key steps for establishing a new orthogonal aaRS/tRNA pair in a host organism, such as E. coli, and validating its functionality and orthogonality.

Computational Identification and Library Construction

- Step 1: In Silico Screening. Screen millions of tRNA sequences from genomic databases (e.g., from bacteria, archaea, bacteriophages) to identify candidate tRNAs with low similarity to the host's identity elements. A scoring system based on known identity elements for host aaRSs can predict orthogonality; tRNAs scoring below a threshold (e.g., +0.5) for all host synthetases are strong candidates [31].

- Step 2: Library Construction. For the candidate aaRS, create mutant libraries. This can involve:

- Site-Specific Mutagenesis: Target residues in the aaRS active site known to be critical for substrate recognition based on homologous pairs (e.g., Tyr32, Asp158, and Leu162 in M. jannaschii TyrRS) to disrupt binding to canonical amino acids [30].

- Random Mutagenesis: Use error-prone PCR or an orthogonal DNA replication system (e.g., OrthoRep in yeast) to generate diverse aaRS variants [28] [30]. OrthoRep continuously mutates the aaRS gene at a high rate (∼10⁻⁵ substitutions per base), enabling rapid, open-ended evolution [28].

Experimental Validation of Orthogonality and Function

- Step 3: tRNA Orthogonality Assessment. Use the tRNA Extension (tREX) method to determine the in vivo aminoacylation status of candidate tRNAs [31].

- Principle: Fluorescent DNA probes are designed to selectively invade the acceptor stem of the target tRNA and anneal to its 3'-end. The presence of an amino acid on the tRNA blocks this annealing, allowing differentiation between charged and uncharged tRNA [31].

- Procedure: Extract total RNA from host cells expressing the candidate tRNA. Incubate the RNA with Cy5-labelled DNA probes. Analyze the samples using gel electrophoresis. A charged tRNA will show no shift, while an uncharged tRNA will form a probe-tRNA complex with a mobility shift. Orthogonal tRNAs should remain uncharged in the host unless their cognate aaRS is present [31].

- Step 4: Selection for Functional aaRS/tRNA Pairs. Use a dual positive/negative selection system in the host organism to isolate aaRS variants that charge the ncAA onto the orthogonal tRNA.

- Reporter System: A common method uses a fluorescent reporter gene (e.g., super-folder GFP, sfGFP) containing an amber codon at a permissive site [28] [30].

- Positive Selection: Grow cells in the presence of the ncAA. Cells with a functional aaRS/tRNA pair will incorporate the ncAA, produce full-length fluorescent protein, and can be isolated via Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) [28] [30].

- Negative Selection: Grow sorted cells in the absence of the ncAA. Cells where the aaRS charges the orthogonal tRNA with a canonical amino acid will read through amber codons in essential genes, leading to cell death or reduced fitness. Only cells with highly specific aaRSs survive [28].

Diagram 1: Directed evolution workflow for orthogonal aaRS using dual selection.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of GCE requires a suite of specialized reagents and molecular tools.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for GCE Experiments

| Reagent / Tool | Function in GCE | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Orthogonal aaRS/tRNA Pair | The core engine for ncAA incorporation; must be orthogonal and efficient in the host. | PylRS/tRNAPyl from M. barkeri; TyrRS/tRNATyr from M. jannaschii; E. coli TyrRS/tRNA pair in eukaryotes [29] [30]. |

| Reporter Plasmid | Reports on the efficiency and fidelity of ncAA incorporation, enabling selection and screening. | Plasmids encoding sfGFP with an amber codon [30]; Ratiometric RFP-GFP (RXG) reporters for quantifying readthrough efficiency [28]. |

| Selection System | Enriches for functional, specific aaRS variants from large libraries. | FACS for fluorescent reporters [28] [30]; growth-based selection with antibiotic resistance genes containing amber codons. |

| Hypermutation System | Accelerates directed evolution by introducing targeted mutations into the aaRS gene. | OrthoRep (an orthogonal error-prone DNA polymerase system in yeast) [28]. |

| tRNA Analysis Tool | Directly measures the aminoacylation status of tRNAs to confirm orthogonality. | tRNA Extension (tREX) method with fluorescent DNA probes [31]. |

Engineering and Optimization Strategies

Sourcing pairs from nature is only the first step. Extensive engineering is often required to enhance orthogonality, improve ncAA incorporation efficiency, and adapt the pair for new hosts or ncAAs.

tRNA Engineering for Enhanced Performance

While early GCE efforts focused predominantly on aaRS engineering, optimizing the tRNA is equally critical for high efficiency [6] [14]. tRNA engineering focuses on two conflicting demands: maintaining orthogonality to host aaRSs while ensuring efficient cooperation with the host's transcriptional and translational machinery [14].

- Modifying Identity Elements: Identity elements are specific nucleotides within a tRNA that are recognized by its cognate aaRS [31] [14]. Mutating these elements in the orthogonal tRNA can reduce its mis-aminoacylation by host aaRSs, thereby improving orthogonality [29]. For example, mutating the tRNA's acceptor stem and anticodon loop can enhance its exclusive recognition by its engineered aaRS [14].

- Optimizing for Host Machinery: The orthogonal tRNA must be efficiently transcribed, processed, and interact with host elongation factors (EF-Tu in bacteria) and the ribosome. Engineering the tRNA's promoter, 5' and 3' sequences, and bases that interact with EF-Tu (e.g., positions in the acceptor stem and T stem) can significantly boost the yield of full-length protein [6] [14].

Diagram 2: Key targets for engineering functional orthogonal tRNAs.

aaRS Engineering for Novel Specificity

The aaRS active site must be redesigned to accommodate a specific ncAA, which is typically achieved through directed evolution [29] [30]. The general workflow involves:

- Creating a large library of aaRS mutants.

- Using a selection system (as described in Section 3.2) to isolate variants that enable ncAA-dependent protein synthesis.

- Iteratively cycling through positive and negative selection to evolve aaRS mutants that are both highly active and specific for the target ncAA [28] [30].

Advanced platforms like OrthoRep streamline this process by enabling continuous in vivo mutagenesis and selection, leading to the rapid discovery of highly efficient aaRSs that can rival the performance of natural translation systems [28].

The deliberate sourcing and sophisticated engineering of orthogonal aaRS/tRNA pairs are foundational to the power and success of Genetic Code Expansion. By strategically selecting pairs from disparate branches of the tree of life and refining them through state-of-the-art directed evolution and engineering protocols, researchers can reliably create custom translation systems. These systems serve as programmable engines for installing novel chemical functionalities directly into proteins, thereby pushing the boundaries of synthetic biology, therapeutic development, and fundamental biological research.