Troubleshooting Molecular Dynamics Simulations: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a systematic guide to diagnosing, resolving, and validating common issues in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations for biomedical and drug discovery applications.

Troubleshooting Molecular Dynamics Simulations: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a systematic guide to diagnosing, resolving, and validating common issues in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations for biomedical and drug discovery applications. Covering foundational principles, methodological choices, and advanced techniques, it addresses critical challenges such as simulation instability, force field selection, sampling inefficiency, and energy conservation. By integrating insights from traditional force fields to modern machine-learning potentials and validation pipelines, this guide equips researchers with practical strategies to enhance the reliability and predictive power of their computational studies, ultimately accelerating therapeutic development.

Understanding the Core Principles and Common Pitfalls of MD Simulations

The Basics of MD Integration Algorithms and Energy Conservation

FAQs: Core Concepts and Troubleshooting

What is the primary role of an integration algorithm in Molecular Dynamics? The integration algorithm numerically solves Newton's equations of motion to advance the simulation forward in time. It uses the current positions and velocities of atoms, along with the forces computed from the interaction potential, to predict their new positions and velocities after a small time increment (δt). This process is repeated for millions of steps to generate a trajectory of the system's evolution [1] [2].

Why is energy conservation a critical property for an MD integrator? In a closed system without external forces, the total energy should be constant. An integrator that conserves energy ensures that the simulation correctly models a physical, microscopic system. This correct physical behavior is the foundation for obtaining reliable thermodynamic and dynamic properties from the simulation [1] [3]. Poor energy conservation can lead to unrealistic system behavior, such as an unphysical heating or cooling trend.

My simulation "blew up" or crashed. Could a poor choice of integrator or time step be the cause? Yes, this is a common reason for simulation failure. If the time step is too large, the numerical integration becomes unstable. Atoms may move unrealistically fast, bonds can stretch too far, and the simulation will crash [4]. Integrators from the Verlet family are generally stable for time steps smaller than the fastest molecular vibration (often bonds with hydrogen atoms). A time step of 1-2 femtoseconds (fs) is common, which can be increased to 4 fs by constraining bonds involving hydrogens or using hydrogen mass repartitioning [2].

The total energy in my simulation shows a steady drift. What should I investigate? A steady energy drift often points to inaccuracies in the integration process or an inadequate equilibration period. First, verify that your time step is not too large. Second, ensure that your system has been properly minimized and equilibrated before the production run; an unrelaxed system with high-energy contacts can cause slow energy drift. Finally, check for potential cutoff issues; a discontinuous force at the cutoff radius can introduce numerical instabilities and energy errors [4] [3].

How does the Velocity Verlet algorithm differ from the Leap-Frog Verlet? While mathematically equivalent and producing identical trajectories, these algorithms differ in how they handle variables. Velocity Verlet calculates positions and velocities at the same point in time, making it more intuitive. In contrast, the Leap-Frog algorithm calculates positions and velocities at interleaved times; velocities are "leap" ahead of positions by half a time step. This means that in Leap-Frog, the positions and velocities are not synchronized, which can complicate analysis if not handled correctly [2]. The restart files for these two methods are also different and not directly interchangeable without adjustment.

What are the key criteria for selecting a good MD integrator? A good MD integrator should be [1] [3]:

- Fast and efficient, requiring only one force evaluation per time step.

- Memory efficient, as MD simulations often involve thousands of atoms.

- Stable, permitting a reasonably long time step for a given system.

- Energy-conserving over long simulation times.

- Time-reversible, a property linked to good long-term stability and energy conservation.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Integration Issues

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Simulation crash ("blow up") | Time step (δt) is too large. | Reduce δt (e.g., to 1-2 fs). Constrain bonds with hydrogen atoms to allow a larger δt [4] [2]. |

| Significant energy drift | Inadequate equilibration; Force discontinuity at potential cutoff. | Extend equilibration until energy, temperature, and density stabilize. Use a shifted-force potential to ensure forces go continuously to zero at the cutoff [4] [3]. |

| Poor energy conservation | Integrator is not time-reversible; Underlying force field issues. | Use a Verlet-based algorithm (e.g., Velocity Verlet, Leap-Frog). Validate the force field parameters for all system components [3]. |

| Discontinuity when switching software/integrator | Mismatch in how positions and velocities are synchronized between algorithms. | When switching from Leap-Frog to Velocity Verlet, be aware that a kinetic energy discontinuity will occur. It is best to start a new simulation from the equilibrated structure [2]. |

| "Out of memory" error during analysis | System is too large or trajectory is too long for available RAM. | Reduce the number of atoms selected for analysis. Analyze the trajectory in shorter segments. Use a computer with more memory [5]. |

Integrator Comparison and Selection Table

The following table summarizes key integrators used in molecular dynamics.

| Integrator Name | Key Algorithmic Features | Energy Conservation & Stability | Common Implementations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Velocity Verlet | Positions and velocities updated synchronously. Requires one force evaluation per step. | Excellent; Time-reversible. The most widely used algorithm [2] [3]. | GROMACS (md-vv), NAMD, AMBER. |

| Leap-Frog Verlet | Positions and velocities updated asynchronously (staggered). Requires one force evaluation per step. | Excellent; Time-reversible. | GROMACS (md), LAMMPS. |

| Euler | Simple forward-stepping algorithm. Uses current force to update position and velocity. | Poor; Not time-reversible. Not recommended for standard MD [2]. | Sometimes available for Brownian dynamics. |

| ABM4 (Adams-Bashforth-Moulton) | Predictor-corrector method, 4th-order. Requires two force evaluations and previous steps. | High accuracy but less stable for large δt. Not self-starting [1]. | Available in some software (e.g., historical Discover versions). |

| Runge-Kutta-4 | 4th-order, self-starting. Requires four force evaluations per step. | Robust but computationally expensive; requires very small δt [1]. | Used to start multi-step methods like ABM4. |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing and Validating an Integrator

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for setting up a simulation with the Velocity Verlet integrator in GROMACS and validating its energy conservation.

Objective: To run a stable molecular dynamics simulation with good energy conservation using the Velocity Verlet integration algorithm.

Software: GROMACS System: A solvated protein-ligand complex.

Methodology:

System Preparation:

- Obtain the initial structure (e.g., from a PDB file) and prepare it using

pdb2gmx. Carefully check for and correct any missing atoms, residues, or incorrect protonation states [4]. - Troubleshooting: If

pdb2gmxfails with "Residue not found in residue topology database," you may need to create parameters for the missing molecule (e.g., a ligand) and include them manually in the topology [5].

- Obtain the initial structure (e.g., from a PDB file) and prepare it using

Energy Minimization:

- Use the steepest descent or conjugate gradient algorithm to remove steric clashes and bad contacts.

- Run until the maximum force is below a reasonable threshold (e.g., 1000 kJ/mol/nm). Confirm that the potential energy has converged [4].

Equilibration:

- NVT Equilibration: Run a simulation in the NVT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature) for ~100 ps. Use a thermostat (e.g., Berendsen, later switching to Nosé-Hoover) to stabilize the temperature.

- NPT Equilibration: Run a simulation in the NPT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) for ~100-500 ps. Use a barostat (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman) to stabilize the pressure and density.

- Validation: Monitor the temperature, pressure, and density to ensure they have stabilized around the target values before proceeding [4].

Production MD with Velocity Verlet:

In your GROMACS

.mdpfile, set the following key parameters:Launch the production run.

Validation and Analysis:

- Energy Conservation: Plot the total energy, potential energy, and kinetic energy over time. A well-conserved total energy will fluctuate randomly around a stable mean without a systematic drift.

- Physical Realism: Calculate properties like the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) and radius of gyration (Rg) to ensure the protein remains structurally stable.

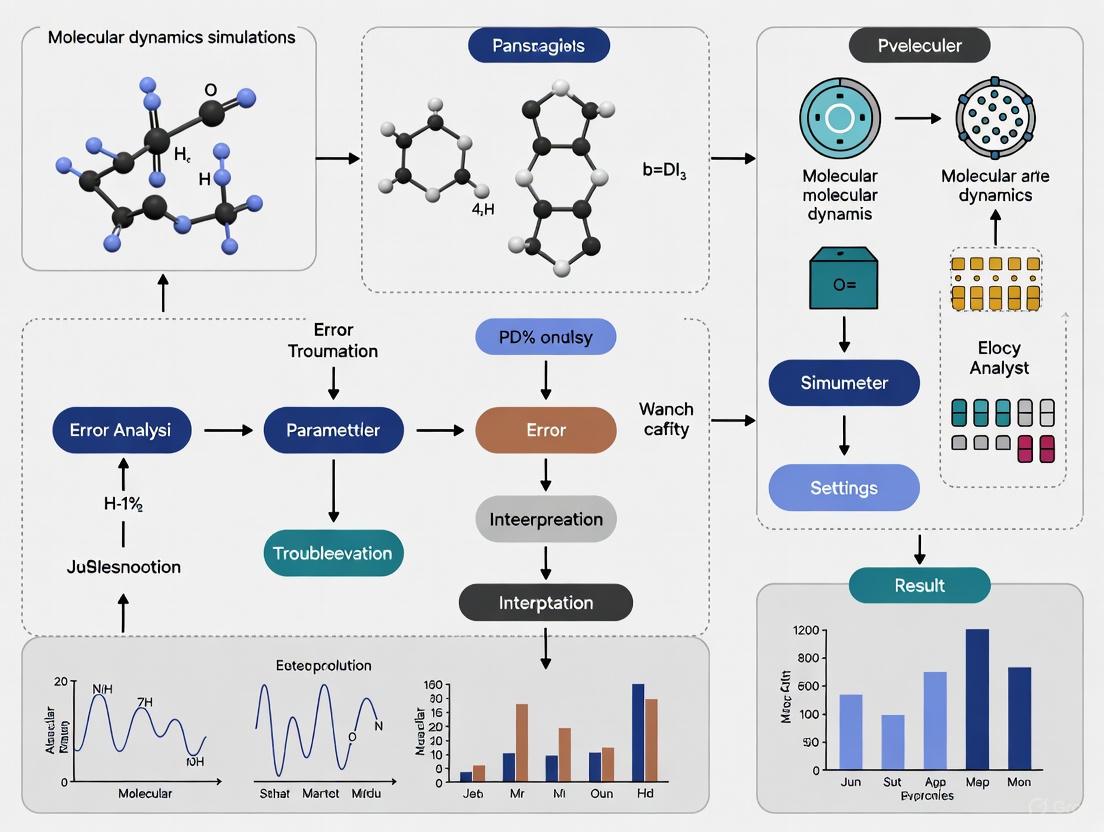

Workflow Diagram: Integrator Selection and Validation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in MD Integration |

|---|---|

| Verlet Integrator | The foundational algorithm for most modern MD simulations. It is time-reversible and energy-conserving, providing long-term stability [3]. |

| Velocity Verlet | A variant of the Verlet algorithm that explicitly calculates and stores velocities at the same time as positions, simplifying the calculation of energy-related observables [2]. |

| LINCS/SHAKE | Constraint algorithms used to fix the lengths of bonds involving hydrogen (or all bonds). This allows for a larger integration time step by eliminating the fastest vibrational frequencies from the system [2]. |

| Thermostat (e.g., Nosé-Hoover) | A "reagent" to control temperature. While a microcanonical (NVE) ensemble requires energy conservation, most biological simulations are run at constant temperature (NVT), which requires a thermostat to mimic energy exchange with a bath. |

| Time Step (δt) | The finite time interval for numerical integration. Its choice is a critical trade-off between computational speed (larger δt) and numerical accuracy and stability (smaller δt) [4] [2]. |

Navigating the Potential Energy Surface and Identifying Local Minima

Welcome to the Technical Support Center for Molecular Dynamics Research. This guide provides essential knowledge and troubleshooting support for researchers navigating Potential Energy Surfaces (PES)—a fundamental concept for understanding molecular geometry, stability, and reaction pathways in computational chemistry and drug development. The PES describes the energy of a system as a function of the positions of its atoms [6]. Effectively finding and characterizing local minima on this surface is crucial for identifying stable molecular structures and intermediates. This resource addresses common challenges encountered in this process, offering clear FAQs and guided solutions to keep your simulations on track.

Core Concepts FAQ

Q1: What is a Potential Energy Surface (PES) and why is it critical in my simulations?

A Potential Energy Surface (PES) is a conceptual and mathematical representation of a molecule's energy as a function of its atomic coordinates [6]. Think of it as a multi-dimensional "energy landscape" where the height corresponds to energy. Your molecular dynamics (MD) or energy minimization simulations work to move the system across this landscape. The key points of interest are the stationary points, where the energy gradient is zero [6]. Among these, local minima correspond to stable molecular conformations, while saddle points (transition states) represent the highest energy point on the lowest energy pathway connecting two minima [6] [7].

Q2: What is the mathematical definition of a local minimum on a PES?

A point on the PES is a local minimum if two conditions are met [7]:

- First Derivatives (Gradient): The slope of the energy function with respect to all geometric coordinates must be zero. ( \left( \frac{\partial E}{\partial qi} \right) = 0 ) for all coordinates ( qi ).

- Second Derivatives (Curvature/Hessian): The matrix of second derivatives (the Hessian) must be positive definite. In practice, this means all its eigenvalues are positive, indicating positive curvature in all directions. This distinguishes a minimum from a saddle point, which has negative curvature in one direction [7].

Q3: How does the Born-Oppenheimer approximation relate to the PES?

The Born-Oppenheimer approximation is a foundational concept that makes the PES a useful tool. It states that due to their much greater mass, atomic nuclei move much more slowly than electrons. This allows us to separate their motions and calculate the electronic energy for a fixed set of nuclear positions [7]. The PES is essentially the result of this calculation—it is the electronic energy plus nuclear repulsion, plotted against nuclear geometry [7].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common PES Navigation Errors

Problem: Energy Minimization Fails to Converge to a Local Minimum

Symptom: Your minimization algorithm (e.g., steepest descent, conjugate gradient) stops without reaching a minimum energy, cycles endlessly, or produces a structure with unrealistic geometry.

Investigation & Solutions:

- Check the Gradient Norm: A true minimum requires a gradient of zero. Most minimization algorithms report the norm of the gradient upon termination. If it is not close to zero (within the tolerance of the software, e.g., 100 kJ mol⁻¹ nm⁻¹ in GROMACS), the minimization has not converged.

- Analyze the Hessian Eigenvalues: Compute the vibrational frequencies (the square roots of the eigenvalues of the mass-weighted Hessian). The presence of one or more negative eigenvalues confirms the structure is a saddle point, not a minimum. A true local minimum will have only positive frequencies.

- Verify Initial Geometry: The minimization may be failing due to a highly unrealistic starting structure with atoms too close together, leading to extreme repulsive forces.

- Review Force Field Parameters: Incorrect or missing parameters for your molecule (e.g., a novel drug ligand) can create an unphysical PES. Ensure all residues and atoms in your system are correctly defined and parameterized in the chosen force field [8].

Problem: "Residue Not Found in Topology Database" Error in GROMACS pdb2gmx

Symptom: When using

gmx pdb2gmxto generate a topology, the program fails with an error that a residue (e.g., 'LIG') is not found in the residue topology database (rtp) [8].Root Cause: The force field you selected does not contain a definition for the molecule or residue you are trying to simulate. This is common for non-standard amino acids, drug molecules, or cofactors [8].

Solutions:

- Check Residue Naming: Ensure the residue name in your PDB file matches the name used in the force field's database.

- Find an Existing Topology: Search literature or force field repositories for a compatible topology file (.itp) for your molecule and include it in your system's top file [8].

- Parameterize the Molecule Yourself: If no topology exists, you must create one. This involves defining atom types, charges, and bonded parameters, which is a non-trivial task that often requires quantum chemical calculations.

- Use a Different Force Field: A different force field might already have parameters for your molecule of interest [8].

Problem: "Atom Index in Position Restraints Out of Bounds"

Symptom: The GROMACS preprocessor

gromppfails with an error about position restraints.Root Cause: This is typically an error in the ordering of

#includestatements in your master topology (.top) file. A position restraints file (posre.itp) is specific to a single[ moleculetype ]and must be included immediately after the corresponding molecule's topology is included [8].Incorrect Topology Structure:

Corrected Topology Structure:

Source: Adapted from GROMACS user guide on common errors [8].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Characterizing a Stationary Point on the PES

This protocol verifies whether a structure obtained from an optimization is a local minimum or a transition state.

- Geometry Optimization: Use an energy minimization algorithm (e.g., via GROMACS, Gaussian, ORCA) to converge a structure to a stationary point (gradient ≈ 0).

- Frequency Calculation: Perform a vibrational frequency calculation on the optimized structure. This calculation computes the eigenvalues of the Hessian matrix.

- Result Interpretation:

- Local Minimum: All vibrational frequencies are real (positive).

- Transition State (Saddle Point): Exactly one imaginary frequency (negative eigenvalue).

Protocol 2: Constructing a Model PES for a Simple Reaction (H + H₂)

The H + H₂ → H₂ + H reaction is a classic example for visualizing a PES [6] [7].

- Define Coordinates: For the collinear reaction (atoms in a straight line), the system can be described with two internal coordinates, such as the two H-H bond lengths.

- Energy Calculation: Use quantum chemical methods (e.g., DFT, CASSCF) to compute the single-point energy for a grid of many possible values of these two bond lengths.

- Visualization:

- Create a 2D contour plot where the axes are the bond lengths and the contour lines represent isoenergetic points [7].

- Alternatively, create a 3D plot with energy as the vertical axis.

- Analysis: Identify the energy "valley" of reactants (H + H₂), the "valley" of products (H₂ + H), and the saddle point that connects them (the H-H-H transition state) [7].

Table 1: Key Features of a Potential Energy Surface and Their Significance.

| Feature | Mathematical Condition | Physical/Chemical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Local Minimum | Gradient = 0; All Hessian eigenvalues > 0 [7] | A stable reactant, product, or reaction intermediate. Represents a molecular conformation that is stable to small distortions. |

| Global Minimum | Gradient = 0; Lowest energy value on the entire PES | The most thermodynamically stable structure of the system. |

| Saddle Point (Transition State) | Gradient = 0; One Hessian eigenvalue < 0; All others > 0 [7] | The highest-energy point on the lowest-energy reaction path between two minima. Confirms a single negative eigenvalue [6] [7]. |

| Reaction Path | Path of steepest descent from saddle point to minima | The most probable pathway for a chemical reaction. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for PES Exploration.

| Tool / "Reagent" | Function in PES Exploration | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Force Field | An empirical function that calculates the potential energy ( U(\vec{r}) ) as a sum of bonded and non-bonded terms [9]. It defines the topography of the PES. | Using a Class I force field like AMBER or CHARMM to model protein-ligand binding energy. |

| Energy Minimizer | An algorithm (e.g., Steepest Descent, Conjugate Gradient) that finds nearby local minima by following the negative energy gradient. | Relaxing a crystal structure of a protein before solvation and simulation to remove steric clashes. |

| Frequency Analysis Code | A routine that computes the second derivatives (Hessian) of the energy to determine if a stationary point is a minimum or saddle point. | Verifying that a proposed drug conformer is stable (a true minimum) and not a transition state. |

| Reaction Coordinate | A geometric parameter (e.g., bond length, angle, or combination) that describes the progression of a chemical reaction. | Tracking the distance between a protein's catalytic residue and a substrate during an enzyme mechanism study. |

PES Navigation Workflow and Energy Landscape

The following diagram illustrates the logical process of navigating a PES to locate and verify a local minimum, integrating the troubleshooting steps and protocols outlined above.

Diagram 1: Workflow for locating and verifying a local minimum on a PES, including key troubleshooting loops.

The following diagram provides a simplified 2D conceptual view of a PES, showing the key features researchers aim to identify.

Diagram 2: A conceptual 2D view of a PES showing minima and a transition state connected by a reaction path.

Recognizing Early Signs of Simulation Instability and Artifacts

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing Energy Instability

Problem Symptoms

Simulation exhibits unrealistic energy fluctuations, system "blows up" (coordinates become NaN), or particles behave erratically.

Diagnostic Protocol

Check Energy Conservation

- Calculate total energy (kinetic + potential) over time

- Acceptable: Small fluctuations around a stable mean

- Problematic: Drifting total energy or explosive growth

Analyze Temperature Drift

- Compare actual temperature to target value from thermostat

- Investigate deviations exceeding 5-10% from target

Monitor Constraint Violations

- Check bond length and angle deviations

- Investigate significant deviation from equilibrium values

Resolution Procedures

Immediate Actions:

- Reduce time step to 0.5-1.0 femtoseconds [10]

- Verify initial velocity assignment follows Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution [10]

- Check for overlapping atoms in initial configuration

Advanced Troubleshooting:

- Switch to more stable integrator (Verlet or leap-frog algorithms) [10]

- Verify force field parameters and compatibility

- Increase collision frequency in thermostat if using Langevin dynamics

Guide 2: Identifying Physical Artifacts

Common Artifact Patterns

Structural Artifacts:

- Unphysical clustering of water molecules

- Artificial ordering at box boundaries

- Unexpected phase transitions on short timescales

Dynamic Artifacts:

- Abnormal diffusion coefficients

- Unphysical conformational transitions

- Artificially frozen degrees of freedom

Diagnostic Methodology

Quantitative Analysis Framework:

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My simulation "explodes" within the first 100ps. What are the most likely causes?

Primary Causes and Solutions:

- Time step too large: Reduce to 0.5-1.0 fs, especially with hydrogen atoms [10]

- Initial steric clashes: Use energy minimization before dynamics

- Incorrect initial velocities: Ensure proper Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution [10]

- Force field mismatch: Verify parameters for all molecular components

Q2: How can I distinguish real physical phenomena from simulation artifacts?

Discrimination Framework:

- Reproducibility: Test with different initial conditions

- Timescale analysis: Artifacts often occur on unphysically short timescales

- System size dependence: Artifacts may disappear with larger simulation boxes

- Sensitivity analysis: Check consistency across different force fields or integrators

Q3: What are the early warning signs of an unstable simulation?

Early Detection Metrics:

| Metric | Normal Range | Warning Sign | Critical Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy drift | < 0.1 kJ/mol/ps | 0.1-1.0 kJ/mol/ps | > 1.0 kJ/mol/ps |

| Temperature fluctuation | ±5K from target | ±5-10K from target | > ±10K from target |

| Bond constraint deviation | < 0.01 Å | 0.01-0.05 Å | > 0.05 Å |

| Pressure oscillation | ±50 bar | ±50-100 bar | > ±100 bar |

Quantitative Stability Assessment Tables

Table 1: Stability Threshold Indicators

| Monitoring Parameter | Stable Range | Caution Range | Unstable Range | Check Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Energy Drift | < 0.05 kJ/mol/ps | 0.05-0.2 kJ/mol/ps | > 0.2 kJ/mol/ps | Every 10ps |

| Temperature RMSD | < 2K | 2-5K | > 5K | Every 1ps |

| Max Bond Length Error | < 0.001 Å | 0.001-0.01 Å | > 0.01 Å | Every 100 steps |

| Volume Fluctuation | < 1% | 1-3% | > 3% | Every 10ps |

| Force Spike Frequency | < 1/100ps | 1-5/100ps | > 5/100ps | Continuous |

Table 2: Artifact Classification and Severity

| Artifact Type | Early Signs | Progressive Symptoms | Critical Level Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Divergence | Small energy drift | Visible temperature rise | Stop; Reduce timestep by 50% |

| Numerical Instability | Occasional force spikes | Frequent coordinate overflow | Switch to Verlet integrator [10] |

| Sampling Artifact | Limited conformational diversity | Trapped in local minimum | Implement enhanced sampling [11] |

| Boundary Artifact | Minor surface ordering | Artificial crystallization | Increase box size by 20% |

| Force Field Artifact | Slight parameter deviation | Unphysical structures | Validate/change force field |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Systematic Stability Assessment

Objective: Establish simulation stability baseline before production runs.

Methodology:

- Equilibration Phase Monitoring

- Run 100ps equilibration with tight tolerance

- Track: Energy, Temperature, Density, Constraints

- Acceptance criteria: All parameters stable for final 20ps

Sensitivity Analysis

- Test time steps: 0.5, 1.0, 2.0 fs

- Compare integrators: Verlet vs. Leap-frog [10]

- Validate with multiple random seeds for initial velocities

Constraint Validation

- Monitor bond length and angle preservation

- Verify SHAKE/LINCS algorithm performance

- Check for cumulative integration error

Protocol 2: Artifact Identification Workflow

Implementation:

Diagnostic Visualization

Simulation Health Dashboard

Simulation Health Assessment Workflow

Artifact Diagnostic Decision Tree

Artifact Diagnostic Decision Tree

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Simulation Components and Their Functions

| Component | Function | Stability Impact | Common Issues |

|---|---|---|---|

| Integrator Algorithms (Verlet, Leap-frog) [10] | Time evolution of equations of motion | Critical: Poor choice causes energy drift | Time step sensitivity; Resonance artifacts |

| Thermostats/Barostats | Maintain constant T/P | High: Artifacts from aggressive coupling | Flying ice cube; Oscillatory behavior |

| Force Fields | Calculate interatomic potentials [10] | Fundamental: Incorrect physics | Parameter transferability; Missing terms |

| Constraint Algorithms (SHAKE, LINCS) | Fix bond lengths/angles | Important: Accumulated error | Linear momentum violation; Iteration failure |

| Periodic Boundary Conditions | Model bulk systems | Moderate: Finite size effects | Artificial ordering; Surface effects |

| Long-Range Electrostatics (PME, Ewald) | Handle Coulomb interactions | Significant: Truncation artifacts | Artificial ordering; Energy drift |

| Enhanced Sampling Methods [11] | Accelerate rare events | Implementation-dependent | Poor collective variables; Sampling bias |

Table 4: Diagnostic Tools and Validation Methods

| Tool/Method | Application | Detection Capability | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Radial Distribution Function [10] | Structural validation | Local ordering artifacts | g(r) calculation from coordinates |

| Mean Square Displacement [10] | Diffusion analysis | Abnormal mobility | MSD from particle trajectories |

| Principal Component Analysis [10] | Collective motion identification | Artifactual dynamics | Covariance matrix diagonalization |

| Energy Decomposition | Force field validation | Parameter imbalance | Per-component energy analysis |

| Cluster Analysis | State identification | Spurious sampling | Conformational clustering |

| Autocorrelation Analysis | Sampling efficiency | Inadequate decorrelation | Time correlation functions |

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations serve as a cornerstone in computational chemistry, biophysics, and drug development, enabling researchers to study the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time. Selecting the appropriate MD software is a critical first step in any simulation workflow, as it directly impacts everything from the force fields you can use to the hardware required for efficient computation. Within the broad ecosystem of available packages, AMBER, GROMACS, and LAMMPS have emerged as three of the most widely used simulation engines. Each possesses distinct strengths, specialized capabilities, and unique troubleshooting considerations that researchers must navigate to ensure successful simulations.

This technical support guide provides a structured comparison and troubleshooting resource tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. The content is framed within the broader context of troubleshooting molecular dynamics simulations research, offering practical solutions to specific, commonly encountered challenges. By understanding the fundamental differences between these software packages and recognizing typical failure modes, researchers can make informed decisions that enhance the reliability and efficiency of their computational experiments.

Software Comparison: Capabilities and Performance Profiles

The choice between AMBER, GROMACS, and LAMMPS depends heavily on your specific research goals, system characteristics, and available computational resources. The table below summarizes their core attributes and performance considerations to guide your selection.

Table: Molecular Dynamics Software Comparison

| Feature | AMBER | GROMACS | LAMMPS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Classical biomolecular simulation (proteins, DNA, nucleic acids) [12] | High-performance biomolecular simulation; known as a "total workhorse" [12] | General-purpose atomic/molecular simulator for materials modeling [13] |

| Typical Force Fields | AMBER (ff19SB, etc.) [12] | AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS, GROMOS [12] | CHARMM, AMBER, COMPASS, DREIDING, OPLS, and many others [14] [12] |

| Key Strengths | Well-optimized for its native force fields; widely used in academic research [12] | Extremely fast, highly parallelized, excellent GPU acceleration [12] | Extremely modular and flexible; easy to extend and modify [13] [12] |

| GPU Acceleration | Yes (pmemd.cuda) [15] |

Excellent, with sophisticated multi-GPU support [16] [15] | Yes, for many styles and packages [13] |

| Scalability | Good on single GPU; multi-GPU mainly for replica exchange [15] | Excellent on both CPU and GPU, for very large systems [12] | Designed for efficient parallel execution on everything from laptops to supercomputers [13] |

| Enhanced Sampling | Variety of methods integrated | Extensive, but method availability depends on implementation [12] | Highly modular, with many community-developed methods [12] |

Performance and Hardware Considerations

Hardware selection profoundly impacts simulation efficiency. For CPU-based workflows, prioritizing processor clock speeds over core count is often beneficial, with AMD Ryzen Threadripper and Intel Xeon Scalable processors being strong contenders [16]. For GPU-accelerated workflows, which can dramatically reduce simulation times, NVIDIA's offerings are dominant:

- NVIDIA RTX 4090: Offers a strong balance of price and performance with 24 GB of GDDR6X VRAM, suitable for many simulation sizes [16].

- NVIDIA RTX 6000 Ada: The top contender for large-scale simulations, featuring 48 GB of GDDR6 VRAM, ideal for the most memory-intensive tasks [16].

Multi-GPU setups can further enhance throughput for GROMACS and LAMMPS, allowing for more extensive simulations or simultaneous runs [16]. In contrast, AMBER's multi-GPU support is primarily intended for methods like replica exchange rather than speeding up a single simulation [15].

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Force Field and Energy Inconsistencies

Problem: Inconsistent potential energies or forces when simulating the same system in different software packages.

This is a common issue when attempting to reproduce a simulation, such as a Potential of Mean Force (PMF) calculation, across different engines like GROMACS and LAMMPS [17].

Diagnosis Methodology:

- Single-Point Force Comparison: Start with an identical atomic configuration (same PDB file). Use both software packages to perform a single-point energy and force calculation without any dynamics. Compare the values for individual atoms [17].

- Unit Conversion Check: Meticulously verify the units for all input parameters, including force constants, particle charges, and Lennard-Jones parameters. Ensure consistency with the internal unit system of each MD package (e.g., nm vs. Ångström in GROMACS) [17] [18].

- Bonded and Non-Bonded Parameter Audit: Systematically compare every term in the potential energy function. Pay close attention to:

- 1-2, 1-3, and 1-4 neighbor exclusions and their scaling factors (e.g.,

special_bondsin LAMMPS vs.fudgeLJandfudgeQQin GROMACS) [17]. - Dihedral angle representations (e.g., proper vs. improper, periodicity).

- Long-range electrostatics and van der Waals treatments, including cutoff schemes, switching/shifting functions, and the specific pair styles used [14].

- 1-2, 1-3, and 1-4 neighbor exclusions and their scaling factors (e.g.,

Solutions:

- NVE Simulation Test: As a debug step, run a short simulation in the NVE ensemble (without a thermostat) in both packages and compare the forces and energies. This removes the variability introduced by thermostating algorithms [17].

- Consult Force Field Documentation: Cross-reference your input parameters with the official documentation for your specific force field (e.g., CHARMM, AMBER) to confirm the intended functional forms and parameters [14].

- Leverage Conversion Tools: Use tools like

charmm2lammps.pl(for CHARMM) ormsi2lmp(for COMPASS) to help generate correct LAMMPS input, but be aware that these tools can become outdated [14].

Software-Specific Topology and Parameterization Errors

Problem: Errors during system setup, such as topology generation or parameter reading.

In GROMACS (

pdb2gmx,grompp):- "Residue 'XXX' not found in residue topology database": The chosen force field does not contain topology information for the residue or molecule 'XXX'. Solutions include checking for alternative residue names in the database, manually providing a topology (

.itpfile), or using a different, more comprehensive force field [18]. - "Invalid order for directive [defaults]": The topology (

.top) file has directives in an incorrect order. The[defaults]directive must appear first, followed by atomtypes, then moleculetype definitions. Rearrange your topology file and its included (.itp) files to follow the required sequence [18]. - "Atom index in position_restraints out of bounds": Position restraint files are included in the wrong order in the master topology file. Each

[ position_restraints ]block must immediately follow the[ moleculetype ]block to which it applies [18].

- "Residue 'XXX' not found in residue topology database": The chosen force field does not contain topology information for the residue or molecule 'XXX'. Solutions include checking for alternative residue names in the database, manually providing a topology (

In LAMMPS:

- "AMBER Force Field Compatibility": LAMMPS support for AMBER force fields is often contributed by users and may not be fully compatible with all variants. If a specific term (e.g., CMAP in newer AMBER force fields) is not supported, you may need to use the native AMBER (

pmemd) software or contribute the necessary code to LAMMPS [19]. - "Bond/Atom Missing": Carefully check the data file or input script for missing coefficients or typos in atom IDs. LAMMPS requires all parameters to be explicitly defined.

- "AMBER Force Field Compatibility": LAMMPS support for AMBER force fields is often contributed by users and may not be fully compatible with all variants. If a specific term (e.g., CMAP in newer AMBER force fields) is not supported, you may need to use the native AMBER (

Performance and Optimization Issues

Problem: Simulation is running slower than expected on available hardware.

- Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Hardware Configuration: Ensure you are using a GPU-accelerated version of the code if a capable GPU is available. For GROMACS, use flags like

-nb gpu -pme gpu -update gputo offload tasks to the GPU [15]. For CPU-only runs, match the number of MPI processes and OpenMP threads to your hardware; using too many can degrade performance [15]. - Increase Time Step with Hydrogen Mass Repartitioning: You can safely increase the simulation time step to 4 fs by using a tool like

parmed(for AMBER topologies) to redistribute mass from heavy atoms to the bonded hydrogens. This keeps the total mass constant but allows faster dynamics [15]. - Check Neighbor Listing Frequency: An overly frequent neighbor list update (e.g., every step) can cripple performance. Adjust the neighbor list skin distance (

rlistin GROMACS,neigh_modify skinin LAMMPS) to a sensible value so the list can be updated less frequently.

- Hardware Configuration: Ensure you are using a GPU-accelerated version of the code if a capable GPU is available. For GROMACS, use flags like

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table: Essential Computational Materials for MD Simulations

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Force Field Parameter Set (e.g., ff19SB, CHARMM36) | Defines the potential energy function, describing atomic interactions, bonded terms, and partial charges. The choice is critical for simulation accuracy [14] [12]. |

| Solvent Model (e.g., TIP3P, OPC, SPC/E) | Represents the water environment in explicit solvent simulations. The model must be compatible with the chosen force field to avoid artifacts [14]. |

| Molecular Topology File | Describes the chemical structure of each molecule in the system, including atom types, bonds, angles, and dihedrals. Generated by tools like pdb2gmx (GROMACS) or tleap (AMBER). |

| Molecular Dynamics Input Script | Contains the simulation protocol: integration parameters, temperature/pressure control, output frequency, and analysis commands. Specific to each MD engine. |

| Coordinate File (e.g., .pdb, .gro, .rst7) | Provides the initial 3D atomic coordinates for the system, typically originating from a crystal structure, NMR model, or previous simulation. |

Experimental Protocol: A Workflow for Diagnosing Force Inconsistencies

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology to diagnose the root cause when a simulation produces different results in AMBER, GROMACS, and LAMMPS, even with "identical" inputs.

Objective: To systematically identify the source of energy or force discrepancies between two or more molecular dynamics software packages.

Background: Differences can arise from subtle variations in unit implementations, treatment of non-bonded interactions, 1-4 scaling factors, or algorithmic differences in long-range electrostatics [17] [14].

Diagram: A logical workflow for diagnosing force and energy inconsistencies between different MD software packages.

Materials:

- An identical atomic structure file (e.g., PDB format) for a small test system (e.g., a solvated amino acid).

- Identical topology and parameter files for the chosen force field, carefully converted for each software.

- Access to AMBER, GROMACS, and LAMMPS installations.

Procedure:

- System Preparation:

- Prepare the topology and input files for each software package. Use official conversion tools where possible (e.g., from CHARMM-GUI for LAMMPS) [14].

- Explicitly document all unit conversions and parameter assignments.

Single-Point Calculation:

- In each software, set up a calculation that computes the energy and forces for the initial structure without any motion. In GROMACS, use

mdrun -rerun; in LAMMPS, use arun 0command. - Extract the total potential energy and the force vector on each atom from each program.

- In each software, set up a calculation that computes the energy and forces for the initial structure without any motion. In GROMACS, use

Analysis and Comparison:

- Quantitative Comparison: Calculate the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of the force vectors for all atoms between the two software outputs. An order-of-magnitude difference indicates a serious problem, such as incorrect units or a major parameter mismatch [17].

- Component Analysis: If possible, break down the total energy by component (bond, angle, dihedral, electrostatic, van der Waals). A discrepancy in one component pinpoints the problematic term.

NVE Simulation Test:

- If single-point forces match, run a short (e.g., 100-step) simulation in the NVE (microcanonical) ensemble in both packages.

- Compare the conservation of total energy and the trajectories. Significant divergence suggests differences in the integration algorithms or their implementation.

Troubleshooting:

- If forces do not match at the single-point stage, focus on unit conversions and the specific functional forms of the non-bonded and bonded potentials [17] [14].

- If forces match but NVE trajectories diverge, investigate the numerical integrators (e.g., Verlet variants) and any default tolerance settings.

- If NVE is stable but NPT/NVT simulations diverge, the issue likely resides in the thermostat or barostat implementation.

Selecting and Applying Force Fields, Thermostats, and Barostats

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

General Force Field Questions

Q: What is a molecular mechanics force field and what are its core components? A: A molecular mechanics (MM) force field is a set of mathematical functions and empirical parameters used to calculate the potential energy of a system of atoms. It is foundational to Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations. The core components of a standard all-atom, fixed-charge force field include [20]:

- Bonded Terms: These describe the energy associated with the covalent structure of molecules.

- Bond Stretch: Energy required to stretch or compress a chemical bond from its equilibrium length.

- Angle Bending: Energy required to bend the angle between two adjacent bonds from its equilibrium value.

- Dihedral/Torsion: Energy associated with rotation around a central chemical bond.

- Non-Bonded Terms: These describe interactions between atoms that are not directly bonded.

- Van der Waals (VDW) Forces: Modeled by functions like Lennard-Jones potential to account for attractive and repulsive forces.

- Electrostatic Interactions: Modeled using Coulomb's law with fixed partial charges assigned to each atom center.

Q: What are the main categories of biomolecular force fields and their primary focuses? A: The workhorses of modern biomolecular simulations are all-atom, fixed-charge force fields, which can be categorized by their development focus [20]:

Table 1: Major Biomolecular Force Field Families

| Force Field Family | Primary Development Focus | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| AMBER | Accurate structures and non-bonded energies for proteins and nucleic acids [20]. | Uses RESP charges fitted to quantum mechanical (QM) electrostatic potential without empirical adjustment [20]. |

| CHARMM | Accurate structures and non-bonded energies for proteins and nucleic acids [20]. | Parameters derived to reproduce QM and experimental data on small molecules and condensed phases [20]. |

| OPLS | Accurate thermodynamic properties of liquids [20]. | Geared toward properties like heats of vaporization, liquid densities, and solvation [20]. |

| GROMOS | Accurate thermodynamic properties [20]. | Similar to OPLS, parameterized for thermodynamic properties of biomolecules [20]. |

Traditional Force Field Troubleshooting

Q: My simulation of a protein is over-stabilizing α-helical structures. What could be wrong and how can I fix it? A: This is a known issue in several AMBER force fields. The original ff94 and ff99 parameter sets were found to over-stabilize α-helices [21]. This was largely traced to limitations in the backbone φ/ψ dihedral parameters, which were initially fit only to low-energy conformations of glycine and alanine dipeptides that lack a local minimum in the α-helical region [21].

- Solution: Use a refined force field that has addressed this imbalance. For example, the ff99SB force field was developed to correct this by refitting the φ/ψ dihedral terms against high-level QM calculations of glycine and alanine tetrapeptides, leading to a better balance of secondary structure elements [21]. If you are using an older force field, upgrading to a more recent variant like ff99SB, ff14SB, or later is recommended.

Q: Why does my glycine-rich peptide show unreasonable conformational sampling? A: This is a subtle but critical issue related to how dihedral terms are defined in AMBER force fields. The problem arises because non-glycine amino acids have an extra set of dihedral terms (φ' and ψ') that branch to the Cβ carbon, which are used to adjust backbone preferences for residues like alanine [21]. However, glycine lacks a Cβ atom and therefore does not have these φ'/ψ' terms. Many post-ff94 modifications (e.g., ff96, ff99) only changed the primary φ/ψ terms, but these new parameters were optimized in the presence of the original ff94 φ'/ψ' terms. When applied to glycine, the parameters are used without the accompanying terms they were fit for, leading to unphysical behavior [21].

- Solution: Ensure you are using a force field that has systematically refit the dihedral parameters accounting for this distinction, such as ff99SB [21].

Q: How do I choose the best traditional force field for simulating a system containing organic solvents or drug-like molecules? A: The choice depends on the specific molecule and the properties you wish to reproduce accurately. It is critical to consult the literature for benchmarks on molecules similar to yours.

- Example Protocol: A 2024 study compared force fields for simulating diisopropyl ether (DIPE), a component of liquid membranes [22]:

- System Preparation: Build a cubic unit cell containing a large number of molecules (e.g., 3375 DIPE molecules) to ensure low statistical fluctuation.

- Simulation: Perform MD simulations in a temperature range of interest (e.g., 243–333 K) using multiple force fields (GAFF, OPLS-AA/CM1A, CHARMM36, COMPASS).

- Benchmarking: Calculate key properties (density, shear viscosity) and compare against known experimental data.

- Selection: The study concluded that CHARMM36 provided the most accurate density and viscosity, making it most suitable for ether-based membrane systems, whereas GAFF and OPLS-AA overestimated these properties [22].

Table 2: Force Field Performance for Diisopropyl Ether (DIPE) [22]

| Force Field | Density Accuracy | Shear Viscosity Accuracy | Recommended for Ether Membranes? |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAFF | Overestimated by ~3% | Overestimated by 60-130% | No |

| OPLS-AA/CM1A | Overestimated by ~5% | Overestimated by 60-130% | No |

| CHARMM36 | Accurate | Accurate | Yes |

| COMPASS | Accurate (but less so than CHARMM36) | Accurate (but less so than CHARMM36) | Possible Alternative |

Neural Network Potential (NNP) Troubleshooting

Q: What are Neural Network Potentials and what advantages do they offer over traditional force fields? A: Neural Network Potentials (NNPs) are a class of machine learning potentials that use neural networks to approximate the potential energy surface derived from high-level Quantum Mechanical (QM) calculations [23]. Their key advantages include:

- High Accuracy: They can achieve accuracy close to their reference QM method (e.g., DFT) for organic molecules, often outperforming general small molecule force fields (GAFF, OPLS) [23].

- Transferability: As universal approximators, they can, in principle, learn complex quantum mechanical interactions without relying on pre-defined functional forms.

- Speed: While computationally heavier than MM, they are orders of magnitude faster than the QM calculations they are trained to emulate [23].

Q: My NNP/MM simulation is extremely slow. How can I optimize performance? A: The high computational cost of NNP evaluations is a major limitation. However, significant performance gains are possible through optimized implementations [23].

- Solution: Utilize software with dedicated NNP/MM optimizations. An optimized implementation in ACEMD using OpenMM-Torch and PyTorch demonstrated a ~5x speed increase. Key optimizations include [23]:

- Full GPU Computation: Ensure all NNP and MM terms are computed on the GPU without CPU-GPU data transfer.

- Custom CUDA Kernels: Use optimized kernels (e.g., via the NNPOps library) for featurization instead of standard PyTorch operations.

- Parallelization: Parallelize computations across the ensemble of networks (e.g., ANI-2x uses 8 networks) and atoms within a single molecule, moving from a batch-processing to a low-latency computing model.

Q: What are the current limitations of NNPs I should be aware of? A: Despite their promise, NNPs have several key limitations [23]:

- Limited Elements: Many NNPs, like ANI-2x, support only a limited set of elements (H, C, N, O, F, S, Cl).

- No Long-Range Interactions: They typically use a fixed cutoff (e.g., 5.1 Å) and do not properly account for long-range electrostatic interactions.

- Charge States: Some NNPs, including ANI-2x, are parameterized only for neutral molecules.

- Computational Cost: They remain significantly more expensive than traditional MM force fields.

Q: What is a typical protocol for running an NNP/MM simulation on a protein-ligand complex? A: The NNP/MM approach is analogous to QM/MM, where a critical region is treated with a high-accuracy method.

- Protocol (based on [23]):

- System Partitioning: Divide the system into an NNP region (e.g., the ligand or a small molecule of interest) and an MM region (e.g., the protein and solvent).

- Energy Calculation: The total potential energy (V) is calculated as a sum of three terms:

V = V_NNP(r_NNP) + V_MM(r_MM) + V_NNP-MM(r)

- Coupling: The interaction between the NNP and MM regions (

V_NNP-MM) is typically handled using a mechanical embedding scheme, applying standard MM non-bonded potentials (Coulomb and Lennard-Jones) between the atoms in the two regions [23]. - Software: Use MD software that supports NNP/MM, such as the optimized implementation in ACEMD that integrates OpenMM for MM, PyTorch for NNP inference, and TorchANI for ANI-2x models [23].

Diagram 1: NNP/MM Simulation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 3: Key Software and Model Resources for Advanced MD Simulations

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Key Features / Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| ANI-2x | A neural network potential for organic molecules [23]. | Provides DFT-level accuracy for molecules containing H, C, N, O, F, S, Cl; used for the NNP region in NNP/MM [23]. |

| OpenMM | A high-performance, GPU-accelerated library for MD simulations [23]. | Serves as the engine for running MM and hybrid (NNP/MM) simulations; provides excellent performance on GPUs [23]. |

| OpenMM-Torch | A plugin for OpenMM [23]. | Allows PyTorch-based models (like ANI-2x) to be directly used as force terms within an OpenMM simulation [23]. |

| TorchANI | A PyTorch-based implementation of ANI models [23]. | Used to create and execute the PyTorch model for ANI potentials [23]. |

| NNPOps | A library of optimized CUDA kernels [23]. | Accelerates critical computations in NNP evaluation, such as featurization, significantly improving simulation speed [23]. |

| GAFF | General Amber Force Field [22]. | A traditional force field for drug-like small molecules; often used as a baseline for comparison against NNPs [22]. |

Diagram 2: Force Field Selection Strategy

Configuring Thermostats (Berendsen, NHC) and Barostats for Ensemble Control

FAQ: Troubleshooting Thermostat and Barostat Configuration

Q1: My simulation temperature is unstable, oscillating wildly. What could be wrong with my Nose-Hoover Chain (NHC) thermostat settings?

Unstable temperatures with NHC thermostats often result from improper coupling parameters. The NHC thermostat uses a chain of variables to mimic a heat bath, and poor choices for the chain length or coupling time can cause large temperature fluctuations [24]. To resolve this:

- Increase the chain length. A longer chain of thermostats better suppresses oscillations [24] [25]. For example, in CONQUEST, increasing

MD.nNHCto 5 or more is a common solution [25]. - Adjust the coupling time constant (

tau_t). This parameter should be set close to the time period of the highest frequency motion in your system [25]. If it's too short, it can cause erratic behavior. - Check your integrator settings. Using a higher-order integration scheme (like setting

MD.nYoshidain CONQUEST) can improve energy conservation and stability [25].

Q2: Why am I getting incorrect kinetic energy distributions in my production run, and how is the thermostat choice involved?

Some thermostats, by design, do not produce the correct kinetic energy distribution of a canonical (NVT) ensemble. The Berendsen thermostat is known for this issue; it provides robust and exponential temperature relaxation but yields an energy distribution with a lower variance than a true NVT ensemble [24] [26]. It is excellent for system relaxation and heating/cooling protocols but should be avoided for production simulations where correct ensemble properties are critical [24].

For production runs, use thermostats that correctly sample the canonical ensemble, such as:

- Nose-Hoover Chains [24] [25]

- Stochastic Velocity Rescaling (Bussi thermostat) [27] [24] [25]

- Langevin dynamics [27] [24]

Q3: My system has a "flying ice cube" effect, where kinetic energy is unevenly distributed. How can I fix this?

The "flying ice cube" effect, where some parts of the system become very hot while others are very cold, can occur when using a global thermostat if heat transfer within the system is slow [24]. This is because a global thermostat controls the temperature uniformly, which may not address local heating or cooling effectively.

Solutions include:

- Using a local thermostat. Some MD packages like NAMD and GROMACS allow you to define different temperature coupling groups (

tc-grpsin GROMACS) or even specify coupling parameters per atom using a PDB file (langevinFile,tCoupleFilein NAMD) [27] [24]. This is particularly useful for large solutes in solvent [24]. - Switching to the Lowe-Andersen thermostat. This stochastic thermostat conserves momentum and perturbs system dynamics less than the original Andersen thermostat, leading to more realistic diffusion [27] [24].

Q4: I'm using the Berendsen barostat for pressure control, but my pressure fluctuations seem unphysical. Is this expected?

Yes, this is a known limitation. The Berendsen barostat uses a weak-coupling scheme to steer the pressure toward a target value, but it does not generate a correct isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensemble [26]. It suppresses pressure fluctuations and results in an ill-defined ensemble. While it is efficient for initial pressure equilibration, it should not be used for production simulations where accurate pressure fluctuations and ensemble properties are needed [26].

For production NPT simulations, use barostats that produce a correct ensemble, such as the Parrinello-Rahman barostat [25].

Q5: How do I choose the right coupling time constant (tau_t or tau_p) for my thermostat and barostat?

The coupling constant determines how tightly the system is coupled to the bath.

- For the Berendsen thermostat,

tau_tis the temperature relaxation time. A value that is too small (e.g., under 0.1 ps) will overly constrain temperature fluctuations, while a value that is too large may lead to a temperature drift. Values on the order of 0.1 ps are typical for condensed-phase systems [26]. - For the Stochastic Velocity Rescaling (SVR) thermostat,

tau_tis also a coupling timescale. A larger value results in slower, gentler coupling. Values between 20–200 fs are generally reasonable [25]. - For the Nose-Hoover Chain thermostat,

tau_tshould be set close to the period of the highest frequency motion in your system (in femtoseconds) [25]. - For barostats, the pressure coupling time

tau_pis typically longer. For the Parrinello-Rahman barostat,tau_pis often set to a value higher thantau_t, for example, 200 fs, but requires testing for optimal energy conservation [25].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Errors and Solutions

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Unstable temperature with large oscillations | NHC thermostat chain is too short or time constant is poorly chosen. | Increase the chain length (nh-chain-length). Adjust tau_t to match the system's highest frequency period [25]. |

| Systematic temperature drift | Thermostat coupling is too weak (e.g., tau_t is too large in Berendsen/SVR). |

Decrease the value of tau_t to strengthen the coupling to the heat bath [26] [25]. |

| Artificially suppressed energy/temperature fluctuations | Use of the Berendsen thermostat, which does not generate a correct canonical ensemble. | Switch to a canonical ensemble thermostat (Nose-Hoover Chains, Bussi, Langevin) for production simulations [24] [26]. |

| "Flying ice cube" effect: uneven temperature | Use of a global thermostat with slow internal heat transfer. | Apply a local thermostat to different groups of atoms or use the Lowe-Andersen thermostat [27] [24]. |

| Pressure does not converge or fluctuates unrealistically | Use of the Berendsen barostat, which suppresses correct fluctuations. | Use a correct ensemble barostat like Parrinello-Rahman for production runs [26] [25]. |

| Poor energy conservation in NPT ensemble | Incorrect combination of tau_t and tau_p for the Parrinello-Rahman barostat. |

Systematically test combinations of tau_t and tau_p to find parameters that give the best energy conservation [25]. |

Thermostat Comparison and Configuration Parameters

The table below summarizes key thermostats, their characteristics, and how to enable them in different MD packages.

| Thermostat | Ensemble Correctness | Key Parameters | GROMACS (tcoupl) |

NAMD | CONQUEST (MD.Thermostat) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berendsen | Weak-coupling; incorrect ensemble [26] | tau_t (coupling time, ~0.1 ps) [26] |

berendsen |

tCouple on [27] |

berendsen [28] |

| Nose-Hoover Chains (NHC) | Canonical (NVT) [24] [25] | tau_t, chain-length (e.g., 5) [25] |

nose-hoover |

nhc [25] |

|

| Stochastic Velocity Rescaling (Bussi) | Canonical (NVT) [27] [25] | tau_t (coupling time) [25] |

v-rescale |

stochRescale on [27] |

svr [25] |

| Langevin | Canonical (NVT) [27] [24] | damping coefficient (e.g., 1/ps) [27] |

sd (as integrator) [29] |

langevin on [27] |

|

| Andersen | Canonical (NVT) [24] [26] | collision frequency (nu) [26] |

andersen |

Experimental Protocol: Equilibrating a System for Production NPT Simulation

This protocol outlines a robust method for equilibrating a solvated protein-ligand system, a common scenario in drug development.

Energy Minimization:

- Purpose: Remove any bad steric clashes and incorrect geometry in the initial structure.

- Method: Use a steepest descent or conjugate gradient algorithm. A tolerance of 100-1000 kJ/mol/nm is typically sufficient.

NVT Equilibration (Berendsen Thermostat):

- Purpose: Relax the system and stabilize the temperature at the target value (e.g., 300 K).

- Method: Run a short simulation (50-100 ps) with the Berendsen thermostat. Use a time constant

tau_tof 0.1-1 ps. Restrain the heavy atoms of the solute (protein/ligand) to their initial positions to allow the solvent to relax around them.

NPT Equilibration (Berendsen Thermostat & Barostat):

- Purpose: Adjust the system density and stabilize the pressure at the target value (e.g., 1 bar).

- Method: Run a simulation (100-200 ps) using the Berendsen thermostat (

tau_t= 0.1-1 ps) and Berendsen barostat (tau_p= 1-2 ps). Continue with positional restraints on solute heavy atoms.

Unrestrained NPT Equilibration (Canonical Thermostat/Barostat):

- Purpose: Allow the entire system to equilibrate fully under production-like conditions.

- Method: Run a simulation (1-5 ns) with all restraints removed. Switch to a production-quality thermostat (e.g., Nose-Hoover Chains or Stochastic Velocity Rescaling) and barostat (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman). Monitor the potential energy, density, and RMSD of the protein backbone for stability.

Production Simulation:

- Continue with the settings from Step 4 for the duration of your production run.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Components for Ensemble Control

| Item | Function in Simulation |

|---|---|

| Thermostat Algorithm | Controls the system temperature by adjusting particle velocities, allowing energy exchange with a heat bath [24]. |

| Barostat Algorithm | Controls the system pressure by adjusting the simulation box size and shape [26] [25]. |

Coupling Time Constant (tau_t, tau_p) |

Determines the strength of coupling to the thermal or pressure bath. Smaller values mean tighter, faster coupling [26] [25]. |

| Ensemble | Defines the thermodynamic state (e.g., NVE, NVT, NPT) of the system being simulated [24]. |

| Stochastic Term | A random force (in Langevin dynamics) or velocity reassignment (in Andersen thermostat) that adds noise to the system to maintain temperature [27] [26]. |

Extended System Mass (W or Q) |

A fictitious mass associated with the extra variable in extended system thermostats/barostats like Nose-Hoover; affects the dynamics of the thermostat itself [25]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the most common cause of a simulation "blowing up" or crashing? A simulation often crashes due to an excessively large time step, which makes numerical integration unstable. This can cause bonds to stretch too far and atoms to move unrealistically fast [4]. Other common causes include poor initial structure preparation with steric clashes, inadequate energy minimization, and incorrect force field parameters [4].

How can I tell if my time step is appropriate? A good rule of thumb is that your time step should be less than half the period of the fastest vibration in your system (Nyquist's theorem) [30]. For biomolecular systems with constrained bonds to hydrogen, 2 femtoseconds (fs) is standard. You can verify your choice by running a constant energy (NVE) simulation and checking for significant drift in the conserved quantity, which indicates an overly large time step [30].

My simulation ran without crashing. Does that mean my setup is correct? Not necessarily. Molecular dynamics engines will simulate a system even with incorrect protonation states, unsuitable force fields, or other subtle issues [4]. Always validate your simulation against known experimental observables, such as NMR data or B-factors, and ensure key thermodynamic properties have stabilized before starting production runs [4].

What are periodic boundary condition (PBC) artefacts, and how do I fix them?

PBCs can cause molecules to appear artificially split across the edges of the simulation box, which distances, angles, and analysis [4]. Most MD software (e.g., GROMACS' gmx trjconv or AMBER's cpptraj) includes tools to "make molecules whole" again before analysis to correct for these effects [4].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Simulation is Unstable or Crashes

1. Check Your Time Step:

- Cause: A time step that is too large is a primary cause of instability [4].

- Solution:

- For all-atom simulations with constrained bonds to hydrogen, start with 2 fs [30].

- If you are using hydrogen mass repartitioning (HMR), you may use a time step of 4 fs, but be aware this can alter kinetics for processes like ligand binding [31].

- For systems with very light atoms (e.g., hydrogen dynamics), a time step as small as 0.25 fs may be required [30].

2. Verify System Preparation:

- Cause: Poor starting structure with steric clashes, missing atoms, or incorrect protonation states [4].

- Solution:

- Use tools like

pdbfixerto add missing atoms and residues. - Carefully assign protonation states appropriate for your simulation pH.

- Perform sufficient energy minimization until the potential energy converges to a stable minimum [4].

- Use tools like

3. Validate Equilibration:

- Cause: Rushing into production before the system is equilibrated [4].

- Solution: Monitor temperature, pressure, density, and total energy during equilibration. Only begin production runs once these properties have stabilized and are fluctuating around a steady average [4].

Problem: Simulation Results Do Not Match Experimental Data

1. Re-evaluate Your Force Field:

- Cause: Using a force field that is not designed for your specific molecule (e.g., using a protein force field for a carbohydrate) [4].

- Solution: Consult the literature to select a force field validated for your system type (e.g., CHARMM36 for proteins, GAFF2 for organic ligands, etc.) [4]. Do not mix incompatible force fields.

2. Ensure Adequate Sampling:

- Cause: A single, short simulation is often insufficient to capture the true thermodynamics of a system, leading to non-representative results [32] [4].

- Solution:

3. Check for PBC Artefacts in Analysis:

- Cause: Incorrectly analyzing a trajectory without correcting for molecules that have crossed periodic boundaries [4].

- Solution: Always process your trajectory with a tool like

gmx trjconv(GROMACS) orcpptraj(AMBER) to make molecules whole before calculating properties like RMSD, radius of gyration, or distances [4].

Problem: Simulation is Too Slow

1. Optimize Time Step and Constraints:

- Cause: Using an unnecessarily small time step wastes resources [4].

- Solution: Use a 2 fs time step with bond constraints (e.g., SHAKE, LINCS) for bonds involving hydrogen. Consider HMR for a 4 fs time step, but only if the kinetics of your process of interest are not the primary focus [31].

2. Benchmark Performance:

- Cause: Inefficient hardware or software configuration.

- Solution: Run a short test simulation (e.g., 1 hour) to determine the simulation speed in nanoseconds per day. Use this to estimate total run time [33]. Allocate computational resources wisely, as using too many CPU cores can sometimes reduce efficiency due to communication overhead [33].

Parameter Selection Guide

The table below summarizes key guidelines for setting up a robust molecular dynamics simulation.

| Parameter | Recommended Value / Method | Key Considerations & Troubleshooting Tips |

|---|---|---|

| Time Step | 2 fs (standard with constraints) [30].4 fs (with HMR) [31].0.25-1 fs (for light atoms/unconstrained) [30]. | • Too large: Causes instability/crashes [4].• Too small: Wastes computational resources [4].• Check stability with an NVE simulation for energy drift [30]. |

| Simulation Duration | System-dependent; requires convergence testing [32]. | • A single short run is often misleading [4].• Run multiple replicates with different initial velocities [4].• Monitor properties (e.g., RMSD, energy) for stability. |

| Boundary Conditions | Periodic Boundary Conditions (PBC). | • Artefact: Molecules can appear split at box edges [4].• Solution: "Make molecules whole" during trajectory analysis [4]. |

| Force Field | System-specific (e.g., CHARMM36, AMBER, GROMOS). | • Do not mix incompatible force fields [4].• Choose a force field parameterized for your molecule type [4]. |

| Validation | Compare simulation observables with experimental data [32]. | • Use experimental data (NMR, B-factors, etc.) for validation [4].• A running simulation does not guarantee physical accuracy [4]. |

Essential Protocols and Workflows

Protocol 1: Validating Your Time Step

This protocol is adapted from established community best practices [30].

- Set Up: Begin with a fully equilibrated system under NVE conditions (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Energy).

- Run Short Simulation: Run a short simulation (e.g., 10-100 ps) using your chosen time step.

- Monitor Conserved Quantity: Plot the total energy (or other relevant conserved quantity for your ensemble) over time.

- Analyze for Drift:

- A good time step will show small fluctuations but no significant long-term drift.

- A rule of thumb is that the long-term drift should be less than 1 meV/atom/ps for publishable results [30].

- If you observe a significant drift, your time step is likely too large.

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for this validation process:

Protocol 2: Correcting Periodic Boundary Condition (PBC) Artefacts

This protocol is essential for accurate analysis and is a common feature in MD software [4].

- Identify the Problem: Before analysis, visually inspect your trajectory. Look for molecules that are split, with atoms on opposite sides of the simulation box.

- Choose a Tool: Use your MD package's trajectory processing tool (e.g.,

gmx trjconvfor GROMACS orcpptrajfor AMBER). - Apply Corrections: When running the tool, select options to:

- Make molecules whole: This reassembles molecules that have been split across periodic boundaries.

- Center the system: This is often done to ensure the protein or main molecule of interest is in the center of the box before making molecules whole.

- Remove jumps: This corrects for entire molecules that have "jumped" across the box due to PBC.

- Output a Corrected Trajectory: Write a new, corrected trajectory file. All subsequent analysis (RMSD, distances, etc.) should be performed on this corrected file.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists key "reagents" or components essential for setting up and troubleshooting molecular dynamics simulations.

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Constraint Algorithms (SHAKE, LINCS, SETTLE) | Algorithms that hold the lengths of bonds (and sometimes angles) involving hydrogen atoms fixed. This allows for a larger integration time step (2 fs) by eliminating the fastest vibrations from the system [31]. |

| Hydrogen Mass Repartitioning (HMR) | A technique that increases the mass of hydrogen atoms (e.g., to 3 amu) and decreases the mass of the bonded heavy atom, keeping the total mass constant. This allows for time steps up to 4 fs but may alter kinetic properties [31]. |

| Virtual Sites | An approach where hydrogen atoms are treated as massless particles whose positions are reconstructed geometrically. This can also enable longer time steps but is a more severe approximation [31]. |

| Thermostat (e.g., Nosé-Hoover, Berendsen, v-rescale) | A algorithm that maintains the temperature of the simulation system at a desired value by scaling velocities or acting as a thermal reservoir [4]. |

| Barostat (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman, Berendsen) | A algorithm that maintains the pressure of the simulation system at a desired value by adjusting the volume of the simulation box [4]. |

| Neighbor Searching Algorithm | An algorithm (e.g., cell decomposition) that efficiently lists all atom pairs within the force cutoff distance, a critical step for calculating non-bonded interactions that dominates computational cost [34]. |

Protein-Ligand Dynamics: Molecular Dynamics Simulation Troubleshooting

This section addresses common challenges researchers face when running Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, specifically for studying protein-ligand interactions.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) for Protein-Ligand MD

Q: I encounter an error with

gmx distancefor interaction analysis: "Selection ... does not evaluate into an even number of positions." What is wrong?- A: This inconsistency arises from the selection syntax. Ensure your

-selectcommand specifies two complete atom groups. For example,'resname "LIG" and name OA' plus 'protein and resid 102 and name OE1'correctly selects atoms from the ligand ("LIG") and the protein (residue 102). Verify the atom names (e.g.,OA,OE1) in your structure files ( [35]).

- A: This inconsistency arises from the selection syntax. Ensure your

Q: Why does my molecule appear to be leaving the simulation box or why are there holes when I visualize the trajectory?

- A: This is a common visualization artifact caused by Periodic Boundary Conditions (PBC). Molecules moving across a box boundary "re-enter" from the opposite side. This is not an error in the simulation. You can fix the visualization for analysis using the

trjconvutility to remolecules into a continuous image ( [36]).

- A: This is a common visualization artifact caused by Periodic Boundary Conditions (PBC). Molecules moving across a box boundary "re-enter" from the opposite side. This is not an error in the simulation. You can fix the visualization for analysis using the

Q: The total charge of my system is a non-integer value (e.g., -0.000001). Is this a problem?

- A: A very small deviation from an integer charge is typically a result of floating-point arithmetic and is not a cause for concern. However, if the deviation is larger (e.g., above 0.01), it usually indicates an error occurred during system preparation, and you should re-check the process of adding ions or constructing your topology ( [36]).

Q: How do I extend a completed simulation to a longer time?

- A: You do not need to start over. You can prepare a new run input file (

.tpr) for an extended simulation using theconvert-tprtool or by creating a new.mdpfile that uses the final state of the previous simulation as its starting point ( [36]).

- A: You do not need to start over. You can prepare a new run input file (

Troubleshooting Common MD Simulation Errors

The table below summarizes specific errors and their solutions in protein-ligand MD simulations.

Table 1: Common MD Simulation Errors and Solutions

| Error / Problem | Likely Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Bonds appearing/breaking in visualization | Visualization software determining bonds based on atomic distances, not the topology. | The bonding pattern defined in your topology file is authoritative. If the software read the .tpr file, the displayed bonds should be correct. Ignore automatic bond creation based on distance ( [36]). |

| "Missing atom" error during preprocessing | The coordinate file (e.g., .pdb) is missing coordinates for atoms defined in the topology. |

Use external programs like Chimera with Modeller, Swiss PDB Viewer, or Maestro to model in the missing atoms. Do not run a simulation with missing atoms ( [36]). |

| Minimization fails with constraints | The Conjugate Gradient minimization algorithm is incompatible with constraints. | Use the steepest descent algorithm for energy minimization when your system contains constraints, as it is capable of handling them ( [36]). |

| Unphysical parameters for exotic species (e.g., metal ions) | Parameters for the ion or cluster are not available in the standard force field. | Do not mix parameters from different force fields. Parametrize the new molecule yourself according to your force field's methodology and validate it thoroughly ( [36]). |

Research Reagent Solutions for Protein-Ligand MD

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Tools for MD System Preparation

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

Solvent Boxes (e.g., spc216.gro) |

Pre-equilibrated boxes of water molecules (e.g., SPC water model) used to solvate the protein-ligand complex in a periodic box ( [36]). |

| Force Field Definition Files | Files (e.g., amber99sb-ildn.ff/) containing the parameters for bonds, angles, dihedrals, and non-bonded interactions for all molecules in the system ( [36]). |

| Residue Topology File (.itp) | A file that defines the molecular topology—atoms, bonds, and interaction parameters—for a specific molecule, such as a unique ligand, that is not in the standard force field. |

vdwradii.dat file |

A file containing van der Waals radii for atom types. A local copy can be modified to prevent solvate from placing water molecules in undesired locations (e.g., within lipid membranes) ( [36]). |

Workflow: Troubleshooting a Protein-Ligand MD Simulation

The diagram below outlines a logical workflow for diagnosing and resolving common issues in a protein-ligand MD setup.

Polymer Design: Molding and Material Failure Analysis

This section provides troubleshooting guidance for the processing and design of polymeric materials, from commodity plastics to engineering polymers.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) for Polymer Processing

Q: My molded plastic part is warping. What are the primary causes?