Unraveling Microbial Evolution: A Metagenomics Guide for Researchers and Drug Developers

This article explores the transformative role of metagenomics in studying microbial evolution, moving beyond traditional culture-based methods to analyze genetic diversity directly from environmental and clinical samples.

Unraveling Microbial Evolution: A Metagenomics Guide for Researchers and Drug Developers

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of metagenomics in studying microbial evolution, moving beyond traditional culture-based methods to analyze genetic diversity directly from environmental and clinical samples. It covers foundational concepts of how metagenomics captures evolutionary mechanisms, dives into advanced methodologies like genome-resolved metagenomics and long-read sequencing for strain-level resolution, and addresses key technical challenges in data analysis and interpretation. A comparative analysis of sequencing platforms and their applications in clinical diagnostics and antimicrobial resistance (AMR) surveillance is provided. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this guide synthesizes current advancements and practical strategies to harness metagenomics for evolutionary insights with significant implications for biomedical research and therapeutic discovery.

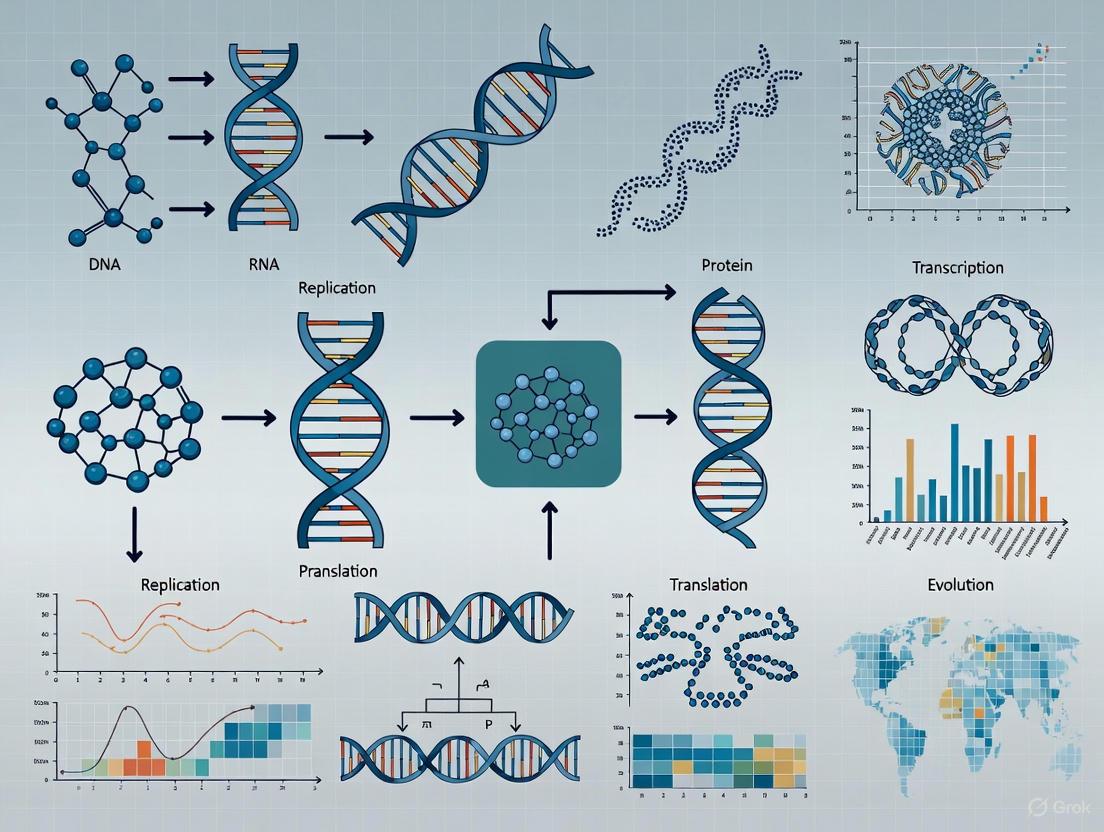

From Genes to Ecosystems: How Metagenomics Reveals Evolutionary Mechanisms

In microbial ecosystems, evolution is driven by a complex interplay of mechanisms that generate and redistribute genetic diversity across populations. Metagenomics, the direct analysis of genetic material from environmental samples, provides a powerful lens to study these processes without the need for laboratory cultivation [1]. This approach has revealed that a substantial fraction of Earth's microbial diversity remains unexplored, with metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) contributing nearly 50% of known bacterial diversity and over 57% of archaeal diversity beyond what cultivated isolates provide [2]. Understanding evolutionary mechanisms in a metagenomic context requires examining how mutation, horizontal gene transfer, and selection operate within complex communities, and developing methodologies to accurately quantify these processes amid technical challenges. This article outlines the key mechanisms, analytical frameworks, and practical protocols for studying microbial evolution through metagenomics.

Core Mechanisms of Genetic Diversity in Microbial Communities

Microbial communities maintain genetic diversity through several interconnected mechanisms that operate across different taxonomic and temporal scales.

Mutation and Recombination serve as fundamental engines of diversity, with single-nucleotide polymorphisms accumulating in populations over time. In metagenomic studies, these variations can be tracked through single-nucleotide variant calling across aligned reads or assembled genomes, providing insights into population dynamics and selection pressures. The mutation rate varies significantly across different microbial taxa and is influenced by environmental factors such as stress, which can increase mutation rates and subsequently accelerate adaptive evolution.

Horizontal Gene Transfer (HGT) represents a dominant force in microbial evolution, enabling the rapid acquisition of novel traits across taxonomic boundaries. Metagenomic studies have revealed that HGT occurs frequently through mobile genetic elements including plasmids, transposons, and integrons [3]. These elements facilitate the spread of adaptive functions, most notably antibiotic resistance genes, which can transfer between commensal and pathogenic bacteria in diverse environments from human guts to agricultural soils. The metagenomic approach allows researchers to identify HGT events by detecting identical gene sequences in distantly related genomes or by associating mobile genetic elements with specific resistance determinants.

Gene Loss and Genome Reduction represent important evolutionary strategies in specialized niches. Symbiotic and parasitic microorganisms often undergo substantial genome reduction, eliminating redundant metabolic pathways while retaining genes essential for their specific lifestyle. Metagenomics can detect these patterns through comparative analysis of MAGs from similar environments, revealing how environmental constraints shape genome architecture.

Table 1: Key Mechanisms of Genetic Diversity Accessible Through Metagenomic Analysis

| Mechanism | Detectable Signals | Metagenomic Approach | Evolutionary Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutation | Single nucleotide variants (SNVs) | Read mapping and variant calling | Measures evolutionary rates and selective pressures within populations |

| Horizontal Gene Transfer | Identical genes in divergent genomes | Association of genes with mobile genetic elements | Rapid dissemination of adaptive traits like antibiotic resistance |

| Gene Family Expansion | Variation in copy number of specific genes | Functional annotation and comparative genomics | Adaptation to specific environmental conditions through gene duplication |

| Genome Reduction | Loss of metabolic pathways | Comparison of MAGs from similar habitats | Specialization to specific ecological niches |

Quantitative Frameworks for Metagenomic Analysis of Evolution

Accurate interpretation of evolutionary processes in metagenomics requires robust quantitative frameworks that account for technical biases and biological variables.

Normalization by Average Genome Size

Comparative analysis between metagenomes is complicated by differences in community structure, sequencing depth, and read lengths. The normalization of metagenomic data by estimating average genome size provides a critical adjustment that enables meaningful quantitative comparisons [4]. This approach calculates the proportion of genomes in a sample capable of particular metabolic traits, relieving comparative biases and allowing researchers to determine how environmental factors affect microbial abundances and functional capabilities. The method involves identifying universal single-copy genes present in all microorganisms to estimate the average genome size for a given community.

Addressing Technical Bias in Metagenomic Studies

Technical bias represents a significant challenge in metagenomic studies, potentially distorting the observed community composition and hindering accurate evolutionary inferences. Experimental studies have demonstrated that using different DNA extraction kits can produce dramatically different results, with error rates from bias exceeding 85% in some samples [5]. The effects of DNA extraction and PCR amplification are typically much larger than those due to sequencing and classification.

A proposed protocol for quantifying and characterizing bias involves creating mock communities with known compositions to assess distortions introduced during sample processing [5]. This approach enables researchers to develop statistical models that predict true community composition based on observed proportions, significantly improving the accuracy of downstream evolutionary analyses.

Table 2: Sources of Bias in Metagenomic Studies and Mitigation Strategies

| Bias Source | Impact on Community Composition | Recommended Mitigation Approach |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction | Kit-dependent, can suppress or amplify certain taxa by >50% | Use mock communities to quantify bias; perform triple DNA extraction |

| PCR Amplification | Preferential amplification of certain sequences; chimera formation | Reduce PCR cycles; use modified primers with balanced GC content |

| Primer Selection | Variable region selection affects taxonomic resolution | Test multiple primer sets; use species-specific primers for target organisms |

| Sequencing Depth | Incomplete representation of rare taxa | Increase sequencing depth; apply rarefaction analysis |

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Quantitative Metagenomic Analysis with Average Genome Size Normalization

Principle: This protocol enables quantitative comparison of microbial communities and functional traits across different samples by normalizing for variation in community structure and sequencing parameters [4].

Materials and Reagents:

- DNA extraction kit (multiple should be compared for optimal yield)

- Universal, single-copy gene reference databases (e.g., RpoA, RpoB, RplA, RplC, RplD, RpsG, RpsJ, RpsQ)

- BLASTALL and FORMATDB programs (NCBI)

- Perl software pipeline for metagenomic sequence analysis

- Metabolism-specific protein databases (e.g., Prk, RbcL for carbon fixation studies)

Procedure:

- Sequence Data Acquisition: Obtain metagenomic sequencing reads from environments of interest. Quality filter and remove host sequences if applicable.

Identification of Universal Single-Copy Genes: Use a Perl software pipeline to iterate through the metagenomic library and identify reads matching universal, single-copy genes. Apply BLASTX with relaxed parameters (-F F -e 1e-5) and require at least 30% amino acid identity and 50% similarity.

Average Genome Size Calculation: Estimate average genome size based on the abundance of universal single-copy genes, which should be present once per genome.

Normalization of Functional Gene Counts: Normalize the counts of target functional genes (e.g., metabolic markers) by the average genome size to calculate the proportion of genomes capable of a particular metabolic trait.

Comparative Analysis: Compare normalized gene abundances across samples to identify statistically significant differences in microbial capabilities, accounting for variations in community structure.

Applications: This approach has been successfully applied to characterize different types of autotrophic organisms (aerobic photosynthetic, anaerobic photosynthetic, and anaerobic nonphotosynthetic carbon-fixing organisms) in marine metagenomes, revealing how factors such as depth and oxygen levels affect their abundances [4].

Protocol: Bias Quantification Using Mock Communities

Principle: This experimental design quantifies technical bias in metagenomic studies using artificial microbial communities with known composition, enabling development of correction models [5].

Materials and Reagents:

- Pure cultures of 7-10 bacterial strains relevant to the study environment

- Multiple DNA extraction kits for comparison (e.g., Powersoil, Qiagen)

- Equipment for cell density measurement (spectrophotometer, flow cytometer)

- PCR reagents and primers targeting appropriate variable regions

- Sequencing platform and taxonomic classification tool (e.g., RDP classifier)

Procedure:

- Experimental Design: Create a D-optimal mixture design with at least (n choose 3) + (n choose 2) + n runs for n bacterial strains, including replicates.

Mock Community Preparation:

- Experiment 1 (Cell Mixture): Grow each isolate to exponential phase, determine cell density, and combine bacteria according to experimental design.

- Experiment 2 (DNA Mixture): Extract gDNA from pure cultures, measure concentration, and mix according to experimental design.

- Experiment 3 (PCR Product Mixture): Amplify DNA from pure cultures and mix PCR products according to experimental design.

Sample Processing: Subject all samples to DNA extraction (Experiment 1 only), PCR amplification, sequencing, and taxonomic classification.

Bias Quantification: Compare observed proportions with expected proportions for each experiment to quantify bias introduced at each processing step.

Model Development: Fit mixture effect models to predict true composition from observed data, applying these models to environmental samples.

Applications: This approach has been used to characterize bias in vaginal microbiome studies, revealing that DNA extraction introduces the largest bias, and enabling more accurate predictions of community composition in clinical samples [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Metagenomic Evolution Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Mock Communities | Quantification of technical bias | Should include 7-10 bacterial strains relevant to study environment; used for quality control |

| Universal Single-Copy Gene Markers | Normalization of metagenomic data | Genes like RpoA, RpoB, RplA present once per genome; enable average genome size calculation |

| Multiple DNA Extraction Kits | Assessment of extraction bias | Compare at least two different kits; Powersoil and Qiagen show significant differences in efficiency |

| Modified Primers with Balanced GC Content | Reduction of PCR amplification bias | Improve coverage of GC-rich or AT-rich genomes; enhance community representation |

| Metabolism-Specific Protein Databases | Functional annotation of metabolic traits | Curated databases for specific pathways (e.g., carbon fixation, antibiotic resistance) |

| Mobile Genetic Element Databases | Tracking horizontal gene transfer | Identify plasmids, transposons, integrons associated with antibiotic resistance genes |

Advanced Applications in Antimicrobial Resistance Research

Metagenomic approaches have revolutionized the study of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) evolution, revealing complex dynamics within uncultivated microbiota. Functional metagenomics can identify novel resistance genes from environmental samples, including previously uncultured microorganisms [3] [1]. This approach has demonstrated that AMR genes are widespread in diverse ecosystems, from clinical settings to rivers, ponds, and agricultural soils, supporting a One Health perspective on resistance evolution.

Recent studies applying metagenomic approaches have revealed:

- Significant correlations between socioeconomic parameters (e.g., GDP per capita) and the abundance of mobile genetic elements and antibiotic resistance genes in human gut microbiomes [3].

- Pervasive antimicrobial resistance determinants across different reservoirs (calves, humans, environment), with approximately 95% of antibiotic resistance genes detected across various sources [3].

- The identification of novel plasmid types carrying multiple resistance genes, such as the IncHI5-like plasmid containing both blaNDM-1 and blaOXA-1 found in clinical Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates [3].

Metagenomic approaches provide unprecedented insights into the mechanisms of genetic diversity and evolution in microbial communities. By leveraging protocols for quantitative analysis, bias correction, and functional screening, researchers can accurately track evolutionary processes including horizontal gene transfer, selection, and adaptation across diverse environments. The integration of these methods with advanced bioinformatic tools and carefully designed experimental protocols enables a comprehensive understanding of microbial evolution in its natural context, with significant applications in antimicrobial resistance research, ecosystem monitoring, and biotechnology development. As metagenomic technologies continue to advance, they will further illuminate the complex evolutionary dynamics that shape microbial world.

The Paradigm Shift from 16S rRNA to Whole-Metagenome Sequencing

The study of microbial communities has undergone a revolutionary transformation with the advent of culture-independent genomic techniques. For decades, 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene sequencing has served as the cornerstone of microbial ecology, providing insights into the composition of prokaryotic communities across diverse environments [6] [7]. This amplification-based approach targets the highly conserved 16S rRNA gene, utilizing its variable regions to differentiate between bacterial and archaeal taxa [8] [9]. However, the rapidly evolving field of metagenomics is now experiencing a significant paradigm shift toward whole-metagenome sequencing (WMS), also known as shotgun metagenomics, which enables comprehensive sampling of all genetic material within a given environment [10] [6]. This transition is driven by the increasing demand for functional insights and higher taxonomic resolution in microbial ecology, evolution, and drug development research.

The limitations of 16S rRNA sequencing have become increasingly apparent as researchers seek to understand not only "which microbes are present" but also "what they are capable of doing" functionally. While 16S sequencing excels at providing cost-effective taxonomic profiles, it offers limited functional information and cannot resolve strain-level variations critical for understanding microbial evolution and pathogenicity [11] [12]. In contrast, WMS provides a comprehensive view of both taxonomic composition and functional potential by sequencing all DNA fragments in a sample, enabling researchers to reconstruct nearly complete genomes, identify novel metabolic pathways, and discover genes with biotechnological and pharmaceutical relevance [10] [6] [7]. This paradigm shift is fundamentally changing how researchers approach microbiome studies across clinical, environmental, and industrial contexts.

Technical Comparison: 16S rRNA Sequencing vs. Whole-Metagenome Sequencing

Fundamental Methodological Differences

The core distinction between these approaches lies in their scope and methodology. 16S rRNA sequencing is an amplicon-based technique that employs PCR to amplify specific variable regions of the 16S rRNA gene (e.g., V3-V4, V4, or full-length V1-V9) followed by high-throughput sequencing [8] [9]. This method leverages the fact that the 16S rRNA gene contains both highly conserved regions (for primer binding) and variable regions (for taxonomic differentiation) [9]. The resulting sequences are clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) or amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) and compared against reference databases for taxonomic classification [11].

In contrast, whole-metagenome sequencing takes an untargeted approach by fragmenting and sequencing all DNA present in a sample, including bacterial, archaeal, viral, fungal, and host genetic material [10] [7]. This technique employs shotgun sequencing without prior amplification of specific marker genes, generating millions of short reads that can be assembled into contigs or mapped directly to reference genomes for both taxonomic and functional analysis [10] [6]. The random nature of DNA fragmentation ensures representation of all genomic regions, providing access to protein-coding genes, regulatory elements, and mobile genetic elements that are inaccessible through 16S sequencing alone [7].

Comparative Performance and Applications

Table 1: Technical comparison between 16S rRNA sequencing and whole-metagenome sequencing

| Parameter | 16S rRNA Sequencing | Whole-Metagenome Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Taxonomic Resolution | Genus-level (sometimes species) [13] [12] | Species-level and strain-level (with sufficient depth) [10] [13] |

| Taxonomic Coverage | Bacteria and Archaea only [13] | All domains (Bacteria, Archaea, Viruses, Fungi, Eukaryotes) [10] [13] |

| Functional Insights | Limited to predicted functions from marker gene [11] | Direct assessment of functional genes and pathways [10] [6] |

| Cost per Sample | Lower cost, high-throughput [11] [13] | Higher cost, requires greater sequencing depth [11] [13] |

| Bioinformatics Complexity | Beginner to intermediate [13] | Intermediate to advanced [13] |

| Host DNA Contamination Sensitivity | Minimal impact [13] | Highly sensitive; affects microbial read coverage [13] |

| Primer/Amplification Bias | Moderate to high (depends on primer selection) [11] [13] | Minimal (no amplification step) [13] |

| Reference Database Dependence | Established, well-curated databases [13] | Evolving, less complete databases [13] |

Table 2: Sequencing platform comparisons for microbiome studies

| Platform | Read Length | Common 16S Regions | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina MiSeq | 2×300 bp | V3-V4 (≈428 bp) [9] | Standard 16S profiling, low-cost WMS |

| Illumina NovaSeq | 2×150 bp | V4 (≈252 bp) [9] | High-depth WMS, large studies |

| PacBio Sequel II | 10-20 kb HiFi reads | Full-length V1-V9 (≈1,500 bp) [12] [9] | High-resolution full-length 16S, metagenome assembly |

| Oxford Nanopore | >10 kb reads | Full-length V1-V9 (≈1,500 bp) [14] [15] | Real-time sequencing, complete genome reconstruction |

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Recent comparative studies highlight key performance differences between these methodologies. A 2022 study comparing full-length 16S rRNA metabarcoding (using Nanopore sequencing) with WMS (using Illumina platform) for analyzing bulk tank milk filters found that while WMS detected a larger number of bacterial taxa and provided greater diversity resolution, full-length 16S rRNA sequencing effectively profiled the most abundant taxa at a lower cost [14]. The two methods showed significant correlation in both taxa diversity and richness, with similar profiles for highly abundant genera including Acinetobacter, Bacillus, and Escherichia [14].

In human microbiome research, a 2024 study demonstrated that full-length 16S rRNA sequencing using PacBio technology achieved substantially higher species-level assignment rates (74.14%) compared to Illumina V3-V4 sequencing (55.23%), though both platforms detected all genera with >0.1% abundance and showed comparable clustering patterns by sample type rather than by sequencing platform [12]. For pediatric gut microbiome studies, 16S rRNA profiling has been shown to identify a larger number of genera, with several genera being missed or underrepresented by each method [11]. This research also indicated that shallower shotgun metagenomic sequencing depths may be adequate for characterizing less complex infant gut microbiomes (under 30 months) while maintaining cost efficiency [11].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing Workflow

Sample Collection and DNA Extraction

- Sample Collection: Collect samples (stool, saliva, soil, water) using appropriate stabilization buffers such as RNAlater or proprietary preservation solutions (e.g., OMR-200 tubes for stool) to prevent microbial community shifts [11] [12]. For human subjects research, obtain appropriate ethical approvals and informed consent [11] [12].

- DNA Extraction: Use specialized kits designed for microbial DNA extraction, such as FastDNA Spin Kit for Soil, PureLink Microbiome DNA Purification Kit, or ZymoBIOMICS DNA Miniprep Kit, which effectively lyse diverse microbial cell walls while minimizing host DNA contamination [6]. Include negative extraction controls to monitor contamination.

- DNA Quality Control: Assess DNA purity using spectrophotometry (A260/A280 ratio ~1.8-2.0) and fluorometry for quantification. Verify DNA integrity via agarose gel electrophoresis, looking for high-molecular-weight DNA without significant degradation.

PCR Amplification and Library Preparation

- Primer Selection: Choose primers targeting appropriate variable regions based on desired taxonomic resolution. For full-length 16S sequencing, use primers 27F (5'-AGRGTTTGATYMTGGCTCAG-3') and 1492R (5'-RGYTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3') [12]. For Illumina platforms, select region-specific primers such as 341F/805R for V3-V4 regions [12] [9].

- PCR Amplification: Perform amplification in triplicate 25-μL reactions containing: 10-50 ng template DNA, 1× PCR buffer, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 0.5 μM each primer, and high-fidelity DNA polymerase. Use the following cycling conditions: initial denaturation at 95°C for 3 min; 25-30 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, 72°C for 60 s; final extension at 72°C for 5 min [12] [9].

- Library Preparation: Purify PCR products using magnetic beads (e.g., AMPure XP beads) and quantify using fluorometric methods. For Illumina platforms, attach dual indices and sequencing adapters via a second limited-cycle PCR step. Pool equimolar amounts of each sample based on quantified values.

Sequencing and Data Analysis

- Sequencing: Load pooled libraries onto appropriate sequencing platforms (Illumina MiSeq for short-read, PacBio Sequel II or Oxford Nanopore for full-length 16S) following manufacturer's recommendations. For Illumina V3-V4 sequencing, aim for 50,000-100,000 reads per sample to capture rare taxa [11].

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Quality Filtering: Use DADA2 [11] or QIIME 2 to remove low-quality reads, trim primers, and filter chimeric sequences.

- ASV/OTU Clustering: Generate amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) using DADA2 or operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at 97% similarity threshold.

- Taxonomic Assignment: Classify sequences against reference databases (Greengenes, SILVA, or RDP) using classifiers like naïve Bayes with confidence thresholds ≥0.7.

- Diversity Analysis: Calculate alpha-diversity (Shannon, Chao1) and beta-diversity (Bray-Curtis, UniFrac) metrics and visualize using PCoA plots.

Figure 1: 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing workflow

Protocol 2: Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing Workflow

Sample Preparation and Library Construction

- Sample Processing: Homogenize samples thoroughly before aliquoting for DNA extraction. For samples with high host DNA contamination (e.g., biopsies), consider implementing host DNA depletion methods using commercial kits such as the NEBNext Microbiome DNA Enrichment Kit.

- DNA Extraction: Use mechanical lysis (bead beating) combined with chemical lysis for maximum DNA yield across diverse microbial taxa. Extract DNA using kits specifically designed for metagenomic studies, such as the MagAttract PowerSoil DNA KF Kit or DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit, which efficiently remove PCR inhibitors [6].

- Library Preparation: Fragment DNA to desired size (typically 300-800 bp) using acoustic shearing or enzymatic fragmentation. Use Illumina DNA Prep or NEBNext Ultra II FS DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina according to manufacturer's instructions. For Nanopore sequencing, use the Ligation Sequencing Kit without fragmentation to maintain long read lengths.

Sequencing and Computational Analysis

- Sequencing Strategy: For Illumina platforms, sequence with 2×150 bp reads on NovaSeq 6000 to achieve 10-20 million reads per sample for complex communities. For long-read technologies, use PacBio Sequel II in HiFi mode or Oxford Nanopore PromethION for real-time analysis [10] [15].

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Quality Control: Remove adapter sequences and low-quality reads using Trimmomatic or Fastp, and eliminate host-derived reads by mapping to host reference genome.

- Assembly: Perform de novo assembly using metaSPAdes or MEGAHIT for short reads, or Canu/Flye for long reads. Assess assembly quality using N50 and check for presence of universal single-copy marker genes with CheckM.

- Binning: Group contigs into metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) using metabat2 or MaxBin based on sequence composition and abundance. Refine bins using DAS Tool and check for contamination and completeness with CheckM.

- Taxonomic Classification: Use Kraken2 or MetaPhlAn for read-based classification, or GTDB-Tk for genome-based taxonomy of MAGs.

- Functional Annotation: Predict protein-coding genes with Prodigal, then annotate against databases such as KEGG, COG, and CAZy using eggNOG-mapper or DRAM. Identify antibiotic resistance genes with CARD or MEGARes, and virulence factors with VFDB.

Figure 2: Whole-metagenome sequencing workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for metagenomic studies

| Category | Product/Kit | Specific Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction | FastDNA Spin Kit for Soil [6] | Difficult-to-lyse environmental samples | Effective against inhibitors, bead-beating mechanism |

| DNA Extraction | PureLink Microbiome DNA Purification Kit [6] | Samples with high host contamination | Selective enrichment of microbial DNA |

| DNA Extraction | MagAttract PowerSoil DNA KF Kit [6] | High-throughput soil and stool samples | Magnetic bead technology, 96-well format |

| Library Preparation | Illumina DNA Prep [8] | Illumina shotgun metagenomics | Tagmentation-based, fast workflow |

| Library Preparation | Ligation Sequencing Kit (Oxford Nanopore) [15] | Long-read metagenomics | Maintains long fragment lengths, real-time sequencing |

| Host DNA Depletion | NEBNext Microbiome DNA Enrichment Kit | Host-contaminated samples | Selective binding of methylated host DNA |

| Targeted Amplification | 16S rRNA PCR Primers (27F/1492R) [12] | Full-length 16S sequencing | Comprehensive coverage of 16S gene |

| Targeted Amplification | 16S rRNA PCR Primers (341F/805R) [9] | V3-V4 hypervariable regions | Optimal for Illumina MiSeq platforms |

| Quality Control | Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit | Accurate DNA quantification | Fluorometric, RNA-insensitive |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina NovaSeq 6000 [14] | High-depth shotgun metagenomics | Ultra-high throughput, 2×150 bp reads |

| Sequencing Platforms | PacBio Sequel II [12] | Full-length 16S and metagenomics | HiFi reads, long insert sizes |

| Sequencing Platforms | Oxford Nanopore PromethION [15] | Real-time metagenomics | Ultra-long reads, portable options |

Advanced Applications in Microbial Evolution and Drug Development

Tracking Microbial Evolution and Strain-Level Variation

The shift to whole-metagenome sequencing has revolutionized studies of microbial evolution by enabling strain-level resolution that was previously unattainable with 16S rRNA sequencing. While 16S rRNA gene sequences often cannot differentiate between closely related bacterial species (e.g., Escherichia coli and Shigella species, or various Streptococcus species) due to highly conserved 16S sequences [12], WMS can identify single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), genomic rearrangements, and horizontal gene transfer events that drive microbial adaptation [10] [7]. This resolution is critical for understanding pathogen evolution, tracking outbreaks, and studying microbial adaptation to environmental stressors, antibiotics, and host immune responses.

For evolutionary studies, WMS facilitates the reconstruction of metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) that provide near-complete genomic context for uncultured microorganisms [6] [7]. This approach has revealed extensive previously hidden microbial diversity, including candidate phyla that lack cultured representatives. By comparing MAGs across different environments or time points, researchers can track evolutionary trajectories, identify positively selected genes, and understand population genetics within complex communities. The functional annotations derived from MAGs further illuminate how metabolic capabilities evolve in response to environmental pressures and ecological interactions.

Drug Discovery and Precision Medicine Applications

The pharmaceutical applications of whole-metagenome sequencing are transforming drug discovery pipelines by providing direct access to the biosynthetic potential of microbial communities. Environmental metagenomes, particularly from extreme or underexplored niches, have become rich sources of novel biocatalysts, antimicrobial compounds, and therapeutic molecules [6]. Functional metagenomics approaches—expressing metagenomic DNA in heterologous hosts—have yielded numerous novel enzymes with industrial applications and antibiotic candidates with unique mechanisms of action [6] [7].

In human health, the shift to WMS enables microbiome-based therapeutic development through comprehensive characterization of microbial communities associated with disease states. Unlike 16S sequencing, WMS can identify specific microbial strains encoding virulence factors, antibiotic resistance genes, and metabolic pathways that interact with host physiology [10] [13]. This information is critical for developing targeted probiotics, prebiotics, and microbiome-based diagnostics. For example, WMS can track the carriage and transfer of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) genes within gut microbiomes, providing insights into resistance dissemination patterns and potential interventions [13] [15]. The ability to reconstruct complete bacterial genomes from metagenomic data further enables the identification of microbial taxa and functions that correlate with drug efficacy and toxicity, paving the way for microbiome-informed precision medicine.

Integrated Approaches and Future Perspectives

Hybrid Strategies for Comprehensive Microbiome Analysis

Rather than representing mutually exclusive alternatives, 16S rRNA and whole-metagenome sequencing are increasingly employed as complementary approaches in comprehensive microbiome studies [13]. Researchers often implement a tiered strategy where 16S rRNA sequencing provides initial community profiling across large sample sets, followed by WMS on selected samples of interest for in-depth functional analysis [13]. This hybrid approach maximizes resources by focusing expensive deep sequencing where it provides the most scientific value while still gathering taxonomic data across the entire experimental design.

Emerging shallow shotgun sequencing methodologies offer an intermediate solution, providing higher discriminatory power than 16S sequencing while remaining more cost-effective than deep WMS [10] [11]. This approach is particularly valuable for large-scale epidemiological studies or longitudinal interventions where both taxonomic and functional insights are needed across hundreds or thousands of samples. For specific applications requiring high taxonomic resolution without the need for comprehensive functional data, full-length 16S rRNA sequencing using third-generation platforms provides species-level identification that bridges the gap between short-read 16S and complete WMS [14] [12].

Technological Advances and Future Directions

The paradigm shift from 16S rRNA to whole-metagenome sequencing is accelerating due to several technological developments. Long-read sequencing technologies from PacBio and Oxford Nanopore are overcoming historical limitations in accuracy while providing reads spanning entire genes and operons, simplifying metagenome assembly and enabling more complete genome reconstruction [12] [15]. Single-cell metagenomics is emerging as a powerful complementary approach that resolves microbial heterogeneity within communities by sequencing individual cells, completely bypassing assembly challenges [7].

The integration of metatranscriptomics, metaproteomics, and metametabolomics with metagenomic data is creating multi-omics frameworks that reveal not only microbial community potential but also their actual activities and functional states [10] [6]. These advances, combined with improved computational methods and expanding reference databases, will continue to enhance our ability to decipher the functional potential and evolutionary dynamics of microbial communities across diverse ecosystems. As sequencing costs decline and analytical methods mature, whole-metagenome sequencing is poised to become the new gold standard for microbial community analysis, particularly for studies requiring functional insights and high taxonomic resolution in the context of microbial evolution and drug development.

The resistome, defined as the comprehensive collection of all antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) and their precursors in both pathogenic and non-pathogenic microorganisms, represents a critical interface for understanding microbial adaptation [16]. The study of resistome evolution has been revolutionized by metagenomic approaches, which enable researchers to investigate the genetic basis of resistance across entire microbial communities without the limitations of culture-based methods [3] [16]. This paradigm shift is particularly important given that the majority of microbial life cannot be cultivated under standard laboratory conditions, a phenomenon known as the "great plate count anomaly" [3]. The dynamics of resistome evolution are driven by complex interactions between horizontal gene transfer, mobile genetic elements (MGEs), and selective pressures from antimicrobial usage across human, animal, and environmental domains [3] [17].

Metagenomic analysis reveals that resistomes are not static but rather highly dynamic components of microbial genomes that continuously evolve in response to environmental stressors [18] [17]. The One Health framework integrates these complex interactions by recognizing the interconnectedness of human, animal, and environmental health in the amplification and dissemination of ARGs [17]. This perspective is essential for understanding the full scope of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) evolution, as environmental resistomes serve as reservoirs for resistance determinants that can ultimately transfer to human pathogens [19] [17]. Tracking these evolutionary pathways requires sophisticated methodological approaches that can capture the diversity, abundance, and mobility of ARGs across diverse ecosystems and temporal scales.

Advanced Methodologies for Resistome Capturing and Analysis

Sample Collection and Metagenomic DNA Sequencing

Protocol 2.1.1: Sample Collection and Preservation

- Sample Type Selection: Collect samples representative of the ecosystem under investigation (e.g., fecal samples for gastrointestinal resistomes, soil/sediment for environmental resistomes, water for aquatic systems) [19] [18]. For comprehensive One Health assessments, implement synchronized sampling across human, animal, and environmental interfaces.

- Collection Methodology: For fecal samples from livestock or humans, collect fresh material using sterile swabs or containers. For pooled farm samples (as in EFFORT study), combine 25 individual pen-floor fecal samples into a single representative pool [18]. For water samples, filter appropriate volumes (typically 100-1000 mL depending on particulate load) through 0.22μm membranes.

- Preservation: Immediately freeze samples at -80°C or preserve in DNA/RNA stabilization reagents to prevent microbial community shifts and nucleic acid degradation. Document all metadata including sampling location, date, temperature, pH, and relevant anthropogenic factors.

- Storage and Transport: Maintain an unbroken cold chain during transport to the laboratory. Store at -80°C until DNA extraction to preserve community structure and genetic material integrity.

Protocol 2.1.2: Metagenomic DNA Extraction and Quality Control

- Cell Lysis: Employ mechanical lysis methods (bead beating) combined with enzymatic lysis (lysozyme, proteinase K) to ensure comprehensive disruption of diverse microbial cell types, including Gram-positive bacteria with robust cell walls.

- DNA Extraction: Use commercial kits specifically validated for metagenomic studies (e.g., DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit) with modifications for maximum yield. Include extraction controls to monitor contamination.

- Quality Assessment: Verify DNA integrity through agarose gel electrophoresis (check for high molecular weight DNA) and quantify using fluorometric methods (Qubit dsDNA HS Assay). Assess purity via spectrophotometric ratios (A260/280 ≈ 1.8-2.0, A260/230 > 2.0).

- Fragment Analysis: Utilize automated electrophoresis systems (e.g., Agilent TapeStation, Bioanalyzer) to determine DNA fragment size distribution and confirm absence of excessive degradation.

Protocol 2.1.3: Library Preparation and Sequencing

- Library Construction: Prepare sequencing libraries using amplification-free protocols when possible to reduce bias [18]. For Illumina platforms, use dual-indexed adapters to enable multiplexing while minimizing index hopping.

- Size Selection: Perform rigorous size selection (typically 350-550 bp insert sizes) to optimize sequencing efficiency and downstream assembly.

- Quality Control: Quantify final libraries using qPCR with library-specific standards for accurate quantification prior to sequencing.

- Sequencing Platform Selection: Utilize high-throughput platforms (Illumina NovaSeq 6000 or HiSeq 3000/4000) with 2×150 bp paired-end sequencing for sufficient coverage and read length [18]. For improved assembly of repetitive regions, consider supplementing with long-read technologies (Oxford Nanopore, PacBio).

Table 1: Comparison of Targeted Enrichment Approaches for Resistome Analysis

| Method | Targets | Sensitivity Enhancement | Cost Efficiency | Best Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CARPDM allCARD Probe Set [20] | All CARD protein homolog models (n=4,661) | Up to 594-fold increase in ARG-mapping reads | Moderate (potential for in-house synthesis savings) | Comprehensive resistome characterization |

| CARPDM clinicalCARD Probe Set [20] | Clinically relevant subset (n=323) | Up to 598-fold increase for clinical ARGs | High | Clinical surveillance and diagnostic applications |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Enrichment [17] | User-defined target sequences | Variable depending on target design | High for small target sets | Focused studies on specific resistance mechanisms |

| Whole Metagenome Sequencing [21] [16] | Entire genetic content | No specific enrichment | Lower for broad resistance detection | Discovery-based studies, unknown ARGs |

Bioinformatics Processing and Resistome Annotation

Protocol 2.2.1: Raw Data Preprocessing and Quality Control

- Adapter Trimming: Remove adapter sequences and low-quality nucleotides using tools such as BBDuk2 with parameters optimized for metagenomic data [18].

- Quality Filtering: Discard reads with average quality scores

- Duplicate Read Removal: For libraries involving PCR amplification, remove identical read pairs using tools such as Picard Tools to reduce amplification bias [18].

- Host DNA Depletion: For host-associated samples, align reads to host reference genomes (e.g., human, bovine) and remove matching sequences to enrich for microbial content.

Protocol 2.2.2: Resistome Profiling and Annotation

- Reference Database Selection: Curate appropriate ARG databases based on research objectives. Key resources include:

- Read Alignment and Quantification: Map quality-filtered reads to ARG databases using alignment tools such as Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA) or Bowtie2 with sensitive parameters. For MGmapper, require properly paired reads with at least 50-bp alignment in each read [18].

- Normalization: Convert raw read counts to normalized values such as Fragments Per Kilobase per Million (FPKM) to account for gene length and sequencing depth variations [18].

- ARG Contextual Analysis: Implement tools such as ARGContextProfiler to distinguish ARGs integrated into chromosomes from those associated with mobile genetic elements, providing insights into mobility potential [3].

Protocol 2.2.3: Advanced Analysis and Integration

- Taxonomic Profiling: Simultaneously analyze microbial community composition using tools such as Kraken or MetaPhlAn to enable integration of resistome and microbiome data [19].

- Mobile Genetic Element Analysis: Identify plasmids, integrons, transposons, and insertion sequences associated with ARGs to understand horizontal transfer potential.

- Assembly-Based Approaches: For high-quality metagenomes, perform de novo assembly using metaSPAdes or MEGAHIT, followed by gene prediction and annotation to discover novel resistance determinants.

- Statistical Normalization: Address compositionality and uneven library sizes using appropriate methods including Cumulative Sum Scaling (CSS), log-ratio transformations, or other techniques implemented in tools such as ResistoXplorer [21].

Data Analysis Frameworks and Interpretation

Analytical Workflows for Resistome Evolution

The following workflow diagram illustrates the comprehensive process for capturing and analyzing resistome data to track AMR evolution:

Statistical Analysis and Data Interpretation

Protocol 3.2.1: Compositional and Diversity Analysis

- Alpha Diversity Metrics: Calculate resistome richness (number of unique ARGs), Shannon diversity index, and Simpson dominance index using count data after proper normalization.

- Beta Diversity Analysis: Perform principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) based on Bray-Curtis dissimilarity or Jaccard distance matrices to visualize resistome similarities between samples.

- Rarefaction Analysis: Generate rarefaction curves to assess sampling completeness and determine whether sequencing depth adequately captured resistome diversity.

- Statistical Testing: Use permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) to test for significant differences in resistome composition between sample groups or experimental conditions.

Protocol 3.2.2: Comparative and Differential Analysis

- Normalization for Comparison: Address compositionality challenges using appropriate methods such as center-log ratio transformation or isometric log-ratio transformation in conjunction with tools designed for metagenomic data (e.g., metagenomeSeq, DESeq2, or edgeR) [21].

- Differential Abundance Testing: Identify ARGs that significantly differ in abundance between conditions using zero-inflated Gaussian mixture models (metagenomeSeq) or negative binomial models (DESeq2) with multiple testing correction (FDR < 0.05).

- Temporal Analysis: For longitudinal studies, implement multivariate approaches to identify resistome trajectories over time and associate changes with external drivers (antimicrobial usage, environmental factors).

Protocol 3.2.3: Advanced Analytical Approaches

- Source Attribution Modeling: Apply machine learning algorithms such as Random Forests to attribute human resistomes to potential animal or environmental sources based on resistome signatures [18].

- Network Analysis: Construct and visualize ARG-microbe co-occurrence networks to identify potential hosts and ecological relationships within microbial communities.

- Functional Profiling: Aggregate ARG abundances by drug class (e.g., tetracyclines, beta-lactams) and resistance mechanisms (e.g., efflux, enzymatic inactivation) to facilitate higher-level interpretation and comparison with antimicrobial usage patterns.

Table 2: Key Analytical Tools for Resistome Data Analysis

| Tool/Platform | Primary Function | Key Features | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| ResistoXplorer [21] | Comprehensive resistome analysis | Composition profiling, functional profiling, integrative analysis, network visualization | Web-based interface |

| ARGContextProfiler [3] | Contextual analysis of ARGs | Distinguishes chromosomal vs. MGE-associated ARGs, mobility potential assessment | Standalone pipeline |

| Random Forests [18] | Machine learning for source attribution | Identifies reservoir-specific signatures, predicts sources of human resistomes | R package |

| MGmapper [18] | Read mapping and classification | Handles metagenomic reads, ResFinder database integration, FPKM normalization | Standalone pipeline |

Research Reagent Solutions for Resistome Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Resistome Analysis

| Category | Specific Product/Resource | Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probe Sets | CARPDM allCARD Probe Set [20] | Targeted enrichment of comprehensive resistome | 4,661 targets, 594-fold enrichment, in-house synthesis protocol |

| Probe Sets | CARPDM clinicalCARD Probe Set [20] | Focused enrichment of clinically relevant ARGs | 323 targets, 598-fold enrichment, cost-effective for diagnostics |

| Reference Databases | ResFinder Database [18] | ARG annotation and classification | 3,026 reference sequences, updated regularly |

| Reference Databases | Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD) [20] | ARG annotation and mechanism analysis | Protein homolog models, resistance ontology, regular updates |

| Bioinformatics Tools | ResistoXplorer Platform [21] | Downstream resistome data analysis | Web-based, multiple normalization methods, statistical analysis |

| Bioinformatics Tools | ARGContextProfiler [3] | ARG mobility context analysis | Assembly graph-based, distinguishes chromosomal/MGE associations |

| Sequencing Kits | Illumina NovaSeq 6000 Reagents | High-throughput metagenomic sequencing | 2×150 bp paired-end, amplification-free protocols available |

| DNA Extraction | DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit | Metagenomic DNA extraction | Mechanical and chemical lysis, inhibitor removal |

Applications and Case Studies in Resistome Evolution

Tracking Cross-Domain ARG Transmission

Case Study 5.1.1: One Health Resistome Surveillance A comprehensive study of beef production systems demonstrated distinct resistome profiles across the production chain, with cattle feces exhibiting predominance of tetracycline and macrolide resistance genes reflecting antimicrobial use patterns [19]. The research identified increasing divergence in resistome composition as distance from the feedlot increased, with soil samples harboring a small but unique resistome that showed minimal overlap with feedlot-associated resistomes. This spatial patterning provides insights into the environmental filtration of resistance determinants and highlights the importance of geographical factors in resistome evolution.

Case Study 5.1.2: Source Attribution Using Machine Learning A groundbreaking European study applied Random Forests algorithms to fecal resistomes from livestock and occupationally exposed humans, successfully attributing human resistomes to specific animal reservoirs [18]. The research identified country-specific and country-independent AMR determinants, with pigs emerging as a significant source of AMR in humans. The study demonstrated that workers exposed to pigs had higher levels of occupational exposure to AMR determinants than those exposed to broilers, and that exposure on pig farms was higher than in pig slaughterhouses. This approach enables targeted interventions by identifying predominant transmission routes.

Temporal Studies of Resistome Dynamics

Case Study 5.2.1: Anthropogenic Impact on Aquatic Resistomes Analysis of the Holtemme river in Germany revealed significant impacts of wastewater discharge on resistome composition, identifying specific ARGs (including OXA-4) in plasmids of environmental bacteria such as Thiolinea (Thiothrix) eikelboomii [3]. This study highlighted the role of environmental microbiota as reservoirs and vectors for ARG transmission, with measurable changes in resistome structure corresponding to anthropogenic inputs. Such temporal and spatial tracking provides critical insights into how human activities shape resistome evolution in natural ecosystems.

Case Study 5.2.2: Agricultural Practices and Soil Resistomes Investigation of agricultural soils under different nitrogen fertilization regimes revealed that while bacterial communities varied with fertilizer type, key ARGs exhibited relative stability [3]. This suggests a resilience in soil resistomes that may maintain resistance determinants even after removal of selective pressures. The study also identified correlations between nitrogen-cycling genes and ARGs, indicating potential indirect selection mechanisms that maintain resistance in the absence of direct antimicrobial selection pressure.

Future Directions in Resistome Research

The field of resistome evolution research is rapidly advancing with several promising technological and methodological innovations. CRISPR-Cas9 enrichment techniques are being developed to enhance the detection of specific resistance determinants in complex samples [17]. The integration of long-read sequencing technologies promises to improve resolution of ARG contexts within mobile genetic elements, providing better understanding of horizontal transfer mechanisms. Additionally, the development of standardized reference materials and inter-laboratory proficiency testing will enhance reproducibility and comparability across resistome studies.

There is growing recognition of the need to expand resistome surveillance beyond clinical and agricultural settings to include more diverse environmental compartments, particularly in low- and middle-income countries where environmental dimensions of AMR have been largely overlooked [17]. Future research must also focus on integrating resistome data with comprehensive metadata on antimicrobial usage, environmental conditions, and ecological parameters to build predictive models of resistome evolution and transmission. Finally, the development of real-time resistome tracking platforms could enable early warning systems for emerging resistance threats, potentially transforming how we monitor and respond to the global AMR crisis.

The methodologies and applications presented in this protocol provide a robust foundation for capturing and analyzing resistomes to understand the evolution and transmission of antimicrobial resistance genes. By implementing these standardized approaches, researchers can generate comparable data across studies and contribute to a comprehensive understanding of resistome dynamics within the One Health framework.

Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs) as Units of Evolutionary Analysis

Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs) represent a transformative approach in microbial genomics, enabling researchers to reconstruct genomes directly from environmental samples without the need for laboratory cultivation. This capability has fundamentally expanded the tree of life, revealing unprecedented microbial diversity and providing new units of analysis for evolutionary studies. By bypassing the "great plate count anomaly"—where over 99% of prokaryotes resist traditional culturing—MAGs allow for the genome-level exploration of previously inaccessible microbial lineages [22]. The integration of MAGs into evolutionary biology has facilitated discoveries regarding horizontal gene transfer, population genetics, niche adaptation, and the evolutionary history of microbial communities across diverse ecosystems from the human gut to extreme environments.

The MAG Revolution in Microbial Evolutionary Studies

Technical Foundations and Methodological Advances

The reconstruction of MAGs from complex microbial communities relies on sophisticated computational approaches that assemble short-read or long-read sequencing data into contiguous sequences, followed by binning procedures that group contigs into putative genomes based on sequence composition and abundance patterns. Recent methodological refinements have significantly enhanced MAG quality and utility for evolutionary inference. Long-read sequencing technologies from Oxford Nanopore and PacBio resolve repetitive genomic elements and structural variations, enabling more complete genome assemblies from complex samples [23]. The establishment of rigorous quality standards, particularly the MIMAG (Minimum Information About a Metagenome-Assembled Genome) criteria, has standardized the field, with high-quality MAGs defined as those exceeding 90% completeness while containing less than 5% contamination [22].

The scalability of MAG generation is evidenced by recent repository collections. The MAGdb resource consolidates 99,672 high-quality MAGs from 13,702 metagenomic samples spanning clinical, environmental, and animal categories [22]. Similarly, the gcMeta database has integrated over 2.7 million MAGs from 104,266 samples across diverse biomes, establishing 50 biome-specific catalogs comprising 109,586 species-level clusters, 63% of which represent previously uncharacterized taxa [24]. These vast genomic resources provide the raw material for large-scale evolutionary analyses across the microbial domain.

MAGs as Units for Evolutionary Inference

MAGs serve as critical data sources for multiple dimensions of evolutionary analysis:

Phylogenetic Placement and Taxonomic Discovery: MAGs have dramatically expanded known microbial diversity, revealing novel phyla and refining evolutionary relationships. Taxonomic annotation of MAGdb's 99,672 HMAGs covered 90 known phyla (82 bacterial, 8 archaeal), 196 classes, 501 orders, and 2,753 genera, with a significant proportion of diversity remaining unclassified at the species level, particularly from environmental samples [22]. This expanded genomic sampling reduces phylogenetic artifacts and improves resolution of deep evolutionary relationships.

Population Genomics and Pangenome Dynamics: MAGs enable population-level analyses by recovering multiple conspecific genomes from complex communities. Single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) patterns, gene content variation, and recombination frequencies can be quantified across populations, revealing evolutionary forces acting within and between microbial lineages.

Horizontal Gene Transfer (HGT) Detection: Comparative analysis of MAGs facilitates identification of recently transferred genomic islands, phage integrations, and plasmid-borne genes. The ability to reconstruct mobile genetic elements from metagenomes provides insights into the dynamics of HGT and its role in microbial adaptation.

Positive Selection and Adaptive Evolution: Coding sequences predicted from MAGs can be analyzed using codon substitution models to identify genes under positive selection, linking genetic adaptation to environmental parameters and ecological niches.

Application Notes: Evolutionary Analysis of MAG Datasets

Workflow for Evolutionary Inference from MAGs

The following protocol outlines a standardized workflow for deriving evolutionary insights from MAG datasets, from quality assessment through phylogenetic reconstruction and selection analysis.

Protocol 1: Evolutionary Analysis Workflow for MAGs

Input Requirements: High-quality MAGs (completeness >90%, contamination <5%) in FASTA format.

Step 1: Quality Assessment and Curation

- Assess MAG quality using CheckM2 or similar tools to verify compliance with MIMAG standards [22].

- Filter MAGs with completeness <90% or contamination >5% from downstream evolutionary analyses.

- For population-level analyses, ensure adequate representation (≥5 conspecific MAGs).

Step 2: Taxonomic Classification and Functional Annotation

- Perform taxonomic classification using GTDB-Tk (reference database release 214 or newer) [22].

- Annotate functional potential using eggNOG-mapper, InterProScan, or similar tools against KEGG, COG, and Pfam databases.

Step 3: Phylogenomic Matrix Construction

- Identify single-copy orthologous genes using OrthoFinder or BUSCO.

- Align protein sequences with MAFFT or Clustal Omega.

- Trim alignments with TrimAl or BMGE.

- Concatenate alignments into supermatrix using FASconCAT or similar tools.

Step 4: Phylogenetic Inference

- Construct maximum-likelihood trees with IQ-TREE (ModelFinder plus ultrafast bootstrapping).

- Alternatively, employ Bayesian inference with MrBayes or PhyloBayes for complex models.

Step 5: Evolutionary Analyses

- For gene gain/loss analysis: Use Count with stochastic mapping or GLOOME for gain-loss models.

- For positive selection: Identify sites under positive selection using CodeML (site models) or FUBAR for large datasets.

- For ancestral state reconstruction: Reconstruct ancestral character states for metabolic traits or habitat preferences using ape or phytools in R.

Step 6: Integration and Visualization

- Integrate phylogenetic trees with metadata using iTOL or ggtree in R.

- Test evolutionary hypotheses with phylogenetic comparative methods.

Table 1: Major MAG Repositories for Evolutionary Studies

| Database | MAG Count | Sample Sources | Key Features | Access URL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| gcMeta | >2,700,000 MAGs | 104,266 samples; human, animal, plant, marine, freshwater, extreme environments | 50 biome-specific catalogs with 109,586 species-level clusters; >74.9 million novel genes; AI-ready datasets | https://gcmeta.wdcm.org/ |

| MAGdb | 99,672 high-quality MAGs | 13,702 samples; clinical (76.2%), environmental (12.0%), animal (11.4%) | Manually curated metadata; taxonomic assignments using GTDB; precomputed genome information | https://magdb.nanhulab.ac.cn/ |

Research Reagent Solutions for MAG Studies

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for MAG Analysis

| Category | Tool/Resource | Primary Function | Application in Evolutionary Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quality Assessment | CheckM2 | Assess MAG completeness and contamination | Filter appropriate units for evolutionary analysis |

| Taxonomic Classification | GTDB-Tk | Standardized taxonomic assignment | Phylogenetic placement and diversity assessment |

| Functional Annotation | eggNOG-mapper | Functional annotation of predicted genes | Reconstruction of metabolic traits for ancestral state reconstruction |

| Orthology Inference | OrthoFinder | Identification of orthologous groups | Construction of phylogenomic matrices |

| Sequence Alignment | MAFFT | Multiple sequence alignment | Preparation of data for phylogenetic analysis |

| Phylogenetic Inference | IQ-TREE | Maximum likelihood tree inference | Reconstruction of evolutionary relationships |

| Selection Analysis | CodeML (PAML) | Detection of positive selection | Identification of adaptively evolving genes |

| Gene Family Evolution | GLOOME | Evolutionary models for gain and loss | Inference of trait evolution across phylogenies |

Advanced Protocols for Specific Evolutionary Questions

Tracking Horizontal Gene Transfer Events Across MAGs

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) represents a fundamental mechanism of microbial evolution. The following protocol enables systematic identification of recent HGT events in MAG collections.

Protocol 2: HGT Detection in MAG Collections

Step 1: Gene Prediction and Annotation

- Predict protein-coding genes in all MAGs using Prodigal.

- Annotate genes against comprehensive databases (NCBI NR, KEGG, COG).

Step 2: Comparative Genomics

- Perform all-vs-all BLASTP of all predicted proteins (e-value cutoff: 1e-5).

- Cluster proteins into orthologous groups using OrthoMCL or similar.

Step 3: HGT Detection

- Compositional deviation: Identify genes with atypical GC content or codon usage relative to host genome using window-based analysis ( Alien_Hunter or similar).

- Phylogenetic incongruence: Construct single-gene trees for potential HGT candidates and compare to species tree using consensus methods (Consel) or topological tests.

- Mobile genetic element association: Annotate transposases, integrases, and phage-related genes adjacent to candidate HGT regions.

Step 4: Validation and Quantification

- Calculate HGT rates as transfers per gene per million years using phylogenetic reconciliation methods (ALE or similar).

- Statistically validate putative HGT events through parametric bootstrapping.

Population Genetic Analysis from Conspecific MAGs

The recovery of multiple MAGs from the same species enables population genetic analyses previously restricted to cultured isolates.

Protocol 3: Population Genetics from MAG Collections

Step 1: Population Identification

- Cluster MAGs into putative populations using average nucleotide identity (ANI >95%) and alignment fraction (AF >60%).

- Verify population coherence with genomic similarity metrics.

Step 2: SNP Calling and Filtering

- Map metagenomic reads to reference MAGs using BWA or Bowtie2.

- Call SNPs with SAMtools/bcftools or specialized metagenomic SNP callers (metaSNV).

- Apply rigorous filters: minimum mapping quality (Q≥30), base quality (Q≥20), and read depth (≥10x).

Step 3: Population Genetic Statistics

- Calculate nucleotide diversity (π), Tajima's D, and FST statistics using PopGenome or VCFtools.

- Identify regions under selection using cross-population composite likelihood ratio (XP-CLR) or similar methods.

Step 4: Evolutionary Inference

- Infer population structure with ADMIXTURE or similar tools.

- Detect recombination rates using ClonalFrameML or similar approaches.

- Model population demographic history with ∂a∂i or similar methods.

Integration with Complementary Approaches

The evolutionary insights derived from MAGs can be significantly enhanced through integration with complementary methodologies. Metatranscriptomics links evolutionary patterns to expressed functions, while metaproteomics and metabolomics provide direct evidence of biochemical activities [23]. Additionally, single-cell metagenomics isolates individual microbial cells, bypassing cultivation biases and revealing genomic blueprints of uncultured taxa, thereby providing reference genomes to improve MAG reconstruction [23]. The integration of microbial co-occurrence networks with functional trait analysis, as implemented in gcMeta, can identify keystone taxa central to biogeochemical cycling and environmental adaptation, providing ecological context for evolutionary patterns [24].

MAGs have established themselves as fundamental units for evolutionary analysis in the microbial world, providing unprecedented access to the genetic diversity and evolutionary dynamics of previously inaccessible lineages. The protocols and resources outlined herein provide a framework for employing MAGs in evolutionary studies, from basic phylogenetic placement to complex analyses of horizontal gene transfer and population dynamics. As MAG quality and availability continue to improve through repositories like MAGdb and gcMeta, and as analytical methods become more sophisticated, MAG-based approaches will increasingly illuminate the patterns and processes that shape microbial evolution across Earth's diverse ecosystems.

Advanced Workflows: From Sample to Evolutionary Insight

Genome-resolved metagenomics has emerged as a transformative approach in microbial ecology and evolution studies, enabling researchers to reconstruct individual microbial genomes directly from complex environmental samples without the need for cultivation. This paradigm shift moves beyond traditional 16S rRNA sequencing by providing access to the full genetic blueprint of uncultivated microorganisms, thereby illuminating the functional potential and evolutionary adaptations of microbial dark matter. By employing sophisticated computational algorithms for assembly and binning, this approach allows for the taxonomic and functional characterization of previously inaccessible microbial lineages. As a cornerstone of modern microbiome research, genome-resolved metagenomics provides the foundational genomic context necessary for investigating microbial evolution, ecological dynamics, and host-microbe interactions, ultimately accelerating the development of microbiome-based therapeutics and diagnostic tools.

The study of microbial communities has undergone a revolutionary transformation with the advent of genome-resolved metagenomics. While conventional 16S rRNA gene sequencing has served as a valuable tool for taxonomic profiling, it presents significant limitations including insufficient resolution for species-level differentiation, inability to perform direct functional analysis, and exclusion of non-bacterial community members [25]. These constraints have historically impeded comprehensive understanding of microbial ecosystem functioning and evolutionary dynamics.

Genome-resolved metagenomics addresses these limitations by reconstructing metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) directly from whole-metagenome sequencing data, providing a comprehensive view of the genetic repertoire of complex microbial communities [25]. This approach has proven particularly valuable for studying the human gut microbiome, where it has revealed unprecedented microbial diversity and functional capabilities. The reconstruction of MAGs enables researchers to investigate microbial evolution through the lens of genetic variations, horizontal gene transfer events, and adaptive mutations that occur within specific host environments [25]. As the volume of public whole-metagenome sequencing data continues to grow exponentially—exceeding 110,000 samples for the human gut microbiome by 2023—the potential for evolutionary insights through comparative genomics has expanded accordingly [25].

Key Methodologies and Computational Frameworks

The construction of MAGs from metagenomic sequencing data involves a multi-step computational process that transforms raw sequencing reads into curated genomes, each representing an individual microbial population within the sampled community.

Assembly and Binning Workflow

The initial assembly step pieces together short reads into longer contigs using either the overlap-layout-consensus (OLC) model or De Bruijn graph algorithms [25]. Specialized assemblers such as metaSPAdes and MEGAHIT employ De Bruijn graphs by breaking short reads into k-mer fragments and assembling these fragments into extended contigs [25]. Following assembly, the binning process clusters contigs into genome bins based on sequence composition and abundance patterns across multiple samples.

Advanced protocols implement subsampled assembly approaches to improve genome recovery from complex communities. This iterative process targets progressively less abundant populations, enhancing total community representation in the final merged assembly [26]. Hybrid binning strategies that combine nucleotide composition with differential coverage information significantly strengthen contig clustering through the application of multiple independent variables [26]. The resulting draft genomes undergo rigorous quality assessment and curation, including error correction and gap closure, to produce high-quality genomic representations suitable for evolutionary analysis.

Enhanced Strategies for Challenging Communities

For particularly complex communities or rare microbial members, advanced techniques have been developed to improve genome recovery:

Stable Isotope Probing (SIP) with Metagenomics: DNA stable isotope probing enables targeted enrichment of active microbes based on uptake and incorporation of isotopically labeled substrates, allowing researchers to link metabolic functions to specific microbial lineages [27]. Genome-resolved DNA-SIP tracks labeled genomes instead of marker genes, distinguishing functional activities among closely related populations with high 16S rRNA similarity [27].

Mini-metagenomics through Cell Sorting: Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) and microfluidic partitioning generate "mini-metagenomes" by separating small groups of cells into low-diversity subsets before DNA extraction and sequencing [27]. This approach reduces complexity and enables recovery of rare members that might otherwise be overlooked in traditional bulk metagenomic analyses.

Long-read Sequencing Technologies: Single-molecule long-read and synthetic long-read technologies help resolve repetitive genomic elements and link mobile genetic elements to host microbial cells, providing crucial insights into horizontal gene transfer and genome evolution [27] [23].

Table 1: Quantitative Overview of Genome-Resolved Metagenomics Applications

| Application Domain | Key Metrics | Representative Findings | Evolutionary Insights |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Gut Microbiome | >110,000 public WMS samples by 2023; 50% subspecies-level classification achieved by 2025 [25] [23] | Discovery of novel bacterial lineages; strain-level variations linked to host phenotypes [25] | Within-species diversity reflects microbiome adaptation to host environments; SNVs associated with host phenotypes [25] |

| Environmental Microbiomes | Reconstruction of genomes from >15% of domain Bacteria [26] | Identification of novel metabolic pathways in uncultivated phyla [26] | Evolutionary adaptations to extreme environments; horizontal gene transfer networks [27] |

| Functional Activity Mapping | Tracking of isotopically labeled genomes [27] | Correlation of specific metabolic functions with microbial lineages [27] | Functional specialization and niche adaptation among closely related strains [27] |

| Mobile Genetic Elements | Linkage of plasmids to host chromosomes [27] | Revelation of horizontal gene transfer networks [27] | Plasmid-mediated evolution and spread of antibiotic resistance genes [27] |

Experimental Protocols for Genome-Resolved Metagenomics

Protocol: Subsampled Assembly and Hybrid Binning for Complex Communities

This protocol outlines a robust method for reconstructing genomes from complex metagenomic datasets, with particular efficacy for abundant community members [26].

Materials and Reagents:

- Multiple metagenomic samples from the same community (recommended: 10-20 samples)

- High-molecular-weight DNA extraction kits

- Library preparation reagents compatible with Illumina, PacBio, or Oxford Nanopore platforms

- Computational resources with sufficient memory and storage (minimum 64GB RAM, 1TB storage)

Procedure:

Sample Preparation and Sequencing:

- Extract DNA from multiple samples representing the same microbial community using standardized protocols to minimize bias.

- Prepare sequencing libraries ensuring appropriate insert sizes for the chosen platform.

- Sequence using either short-read (Illumina) or long-read (PacBio, Oxford Nanopore) technologies, with recommended coverage of 20-50Gbp per sample for complex communities.

Subsampled Assembly Process:

- Perform initial assembly on individual samples using dedicated metagenomic assemblers (e.g., MEGAHIT, metaSPAdes).

- Merge assemblies from multiple samples to create a comprehensive contig set.

- Implement iterative subsampling to target progressively less abundant populations:

- Identify contigs from abundant organisms in initial assembly.

- Filter reads mapping to these contigs.

- Reassemble remaining reads to recover genomes from less abundant community members.

- Repeat this process until no significant new contigs are recovered.

Hybrid Binning Approach:

- Map reads from all samples back to the merged assembly to generate coverage profiles.

- Calculate tetranucleotide frequencies for all contigs >2.5kbp.

- Perform initial binning using composition-based methods (e.g., MetaBAT).

- Refine bins using differential coverage patterns across samples:

- Identify co-abundance patterns among contigs.

- Cluster contigs with similar coverage profiles across multiple samples.

- Apply manual curation tools (e.g., Anvi'o) to inspect and refine bin boundaries.

Genome Curation and Quality Assessment:

- Assess genome completeness and contamination using CheckM or similar tools.

- Perform error correction on draft genomes.

- Attempt gap closure using long-read data or specialized assemblers.

- Annotate curated genomes using standardized pipelines (e.g., PROKKA, RAST).

Troubleshooting Notes:

- For communities with high strain heterogeneity, consider strain-resolved assembly algorithms.

- If binning results show high contamination, adjust coverage covariance parameters and increase sample number.

- For low-abundance populations, incorporate targeted enrichment strategies such as fluorescence-activated cell sorting or stable isotope probing.

Workflow Visualization: Genome-Resolved Metagenomics Pipeline

Diagram 1: Genome-Resolved Metagenomics Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Successful implementation of genome-resolved metagenomics requires both wet-lab reagents and computational resources. The following table details key components of the methodological pipeline.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Genome-Resolved Metagenomics

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Technologies | Illumina short-read platforms; PacBio SMRT; Oxford Nanopore | Generate sequence data from metagenomic samples | Short-read for cost-effective coverage; long-read for resolving repeats and structural variants [27] [23] |

| DNA Extraction Kits | High-molecular-weight DNA extraction kits | Obtain high-quality, high-molecular-weight DNA | Critical for long-read sequencing and minimizing bias in community representation [23] |

| Assembly Software | metaSPAdes, MEGAHIT, IDBA-UD | Reconstruct contigs from sequencing reads | MEGAHIT for large datasets; metaSPAdes for complex communities [25] [26] |

| Binning Tools | MetaBAT, MaxBin, CONCOCT | Cluster contigs into genome bins | Differential coverage binning with multiple samples significantly improves results [26] |

| Quality Assessment | CheckM, BUSCO | Assess genome completeness and contamination | Essential for benchmarking MAG quality before downstream analysis [26] |

| Annotation Pipelines | PROKKA, RAST, DRAM | Functional annotation of MAGs | Prediction of metabolic pathways and functional capabilities [25] |

| Specialized Reagents | Stable isotopes (13C, 15N) for DNA-SIP; Cell sorting reagents | Target active community members | Linking metabolic function to specific populations; enriching rare members [27] |

Advanced Applications in Microbial Evolution Studies

Genome-resolved metagenomics provides unprecedented opportunities for investigating microbial evolution directly in natural environments. By reconstructing genomes from complex communities over time or across different environmental conditions, researchers can track evolutionary processes in real-time.

Tracking Microbial Transmission and Evolution

The application of genome-resolved metagenomics to longitudinal studies enables the tracking of bacterial transmission and within-host evolution. Comparative genomic analyses of MAGs reconstructed from the same individual over time or between connected individuals reveal patterns of:

- Within-host evolution: Single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and structural variants (SVs) that accumulate in microbial genomes during colonization of specific host environments [25].