Unveiling the Hidden Resistome: Advanced Strategies for Identifying Novel Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Wastewater

The global rise of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) poses a severe threat to public health, and wastewater is now recognized as a critical reservoir and amplifier for antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs).

Unveiling the Hidden Resistome: Advanced Strategies for Identifying Novel Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Wastewater

Abstract

The global rise of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) poses a severe threat to public health, and wastewater is now recognized as a critical reservoir and amplifier for antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs). This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and drug development professionals on the cutting-edge methodologies and challenges in identifying novel ARGs in wastewater systems. We explore the foundational role of wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) as hotspots for ARG diversity, detail advanced functional and computational metagenomic techniques like fARGene and CRISPR-enriched sequencing for gene discovery, address key troubleshooting and optimization challenges in analysis, and present rigorous validation frameworks for confirming gene function and clinical relevance. Synthesizing insights from recent global studies, this work underscores the imperative of wastewater surveillance as an early warning system for emerging resistance threats and a vital component of the One Health approach to combating AMR.

Wastewater as a Hotspot for Novel Antibiotic Resistance Genes

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) represents one of the most pressing global public health threats of our time, with resistant bacterial infections linked to an estimated 4.71 million deaths worldwide in 2021 [1]. The One Health perspective recognizes that the health of humans, animals, plants, and the environment are interconnected, and that the challenge of AMR cannot be contained within any single domain. The resistome—the comprehensive collection of all antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) and their precursors in both pathogenic and non-pathogenic microorganisms—flows freely across these artificial boundaries [2]. Understanding this dynamic interchange is critical for developing effective strategies to combat the global AMR crisis.

The United Nations General Assembly reinforced AMR as a global public health priority in its 2024 Political Declaration, emphasizing the need to simultaneously monitor and address AMR within and across all One Health sectors [1]. This complex problem requires broad One Health stewardship from local to global levels, encompassing infection prevention together with stewardship across the six stages of the antimicrobial lifecycle: (1) research and development, (2) production, (3) registration evaluation and market authorization, (4) selection, procurement and supply, (5) appropriate and prudent use, and (6) disposal [1].

Wastewater systems represent a critical interface and amplification point for AMR transmission, receiving resistance genes from human, animal, and industrial sources [3] [4]. This makes wastewater research particularly valuable for identifying novel ARGs and understanding their dissemination pathways across the One Health spectrum.

Quantitative Profiling of Global Resistomes

Human and Wastewater Resistomes

Wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) serve as significant reservoirs and mixing points for antibiotic resistance genes from human populations. A comprehensive global study analyzing activated sludge samples from 142 WWTPs across six continents revealed a core set of 20 ARGs that were present in all facilities and accounted for 83.8% of the total ARG abundance [3]. The resistance genes for beta-lactam (46.5%), glycopeptide (24.5%), and tetracycline (16.2%) were the most abundant classes identified [3].

Table 1: Core Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Global Wastewater Treatment Plants

| Rank | ARG | Drug Class | Relative Abundance | Presence Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tetracycline Resistance MFS Efflux Pump | Tetracycline | 15.2% | Global (100% of WWTPs) |

| 2 | ClassB | Beta-lactam | 13.5% | Global (100% of WWTPs) |

| 3 | vanT (vanG cluster) | Glycopeptide | 11.4% | Global (100% of WWTPs) |

| 4-20 | Various ARGs | Multiple classes | 43.7% | Global (100% of WWTPs) |

Advanced studies of hospital wastewater systems using hybrid sequencing technologies have revealed even more complex resistomes. One such analysis identified 175 ARG subtypes conferring resistance to 38 different antimicrobial classes, including last-resort antibiotics [5]. A striking 85% of 131 metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) carried ARGs, demonstrating the pervasive nature of resistance in these environments [5].

Animal and Agricultural Resistomes

The animal sector represents a substantial reservoir of antimicrobial resistance genes, with striking variations across species and geographies. A massive global analysis of 4,017 livestock manure metagenomes from 26 countries revealed distinct patterns in both the diversity and abundance of ARGs [2]. The study employed a sophisticated risk scoring system (0-4) that integrated mobility potential, clinical importance, and host pathogenicity to assess the potential threat of identified ARGs [2].

Table 2: Global Livestock Resistome Profile by Species

| Species | ARG Diversity Rank | ARG Abundance Rank | Highest Risk Regions | Noteworthy Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chicken | Highest | Highest | South America, Africa, Asia | Elevated risk scores (>3.0 in multiple regions) |

| Swine | Intermediate | Intermediate | Africa, Western Europe | Moderate risk scores (2.0-2.5 range) |

| Cattle | Lowest | Lowest | Limited regional variation | Consistently lower risk scores |

The analysis revealed that poultry samples easily led the livestock sector in both diversity and abundance of ARGs, followed by swine, with cattle demonstrating significantly lower resistance potential [2]. This hierarchy correlates with the intensity of antimicrobial use in these production systems and highlights the need for species-specific intervention strategies.

Environmental and Cross-Sectoral Comparisons

Comparative resistome analysis across different habitats reveals distinct patterns that reflect the interconnected nature of One Health compartments. Wastewater treatment plant resistomes show greater similarity to soil and sewage resistomes than to human gut or ocean environments [3]. This pattern underscores the role of wastewater systems as interfaces connecting human and environmental resistomes.

A focused study in Nepal examining human, animal, and environmental samples identified 53 ARG subtypes across the studied samples, with poultry samples exhibiting the highest number of unique ARG subtypes [6]. This suggests that intensive antibiotic use in poultry production contributes disproportionately to the dissemination of AMR across multiple domains. The same study detected 72 virulence factor genes and observed frequent horizontal gene transfer events, with gut microbiomes serving as key reservoirs for ARGs [6].

Methodologies for Resistome Surveillance and Analysis

Sample Collection and Preservation Protocols

Field Sampling Procedures:

- Wastewater Sampling: Collect grab samples (500 mL) using automated samplers or manual collection methods. For river water adjacent to WWTPs, collect both water and sediment samples using sterile spatulas [6].

- Human and Animal Fecal Samples: Collect fresh specimens in sterile plastic containers and immediately transfer to preservation media. For optimal DNA preservation, divide samples into two vials: one containing 5 mL RNAlater and another with glycerol buffer [6].

- Transport Conditions: Maintain cold chain (2-8°C) during transport to the laboratory. Process samples within 24 hours of collection or store at -80°C for long-term preservation [6].

Ethical Considerations: For human subjects research, obtain appropriate ethical approvals (e.g., from institutional review boards or equivalent ethics committees). Secure informed consent from all participants or their legal guardians before sample collection [6].

DNA Extraction and Sequencing Strategies

Nucleic Acid Extraction:

- Fecal Samples: Use commercial kits such as QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit, following manufacturer's instructions with modifications as needed for sample type [6].

- Environmental Samples: Employ specialized kits designed for complex matrices, such as the PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit, to overcome PCR inhibitors commonly found in environmental samples [6].

- Quality Assessment: Quantify DNA concentration using fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit Fluorometer) and assess integrity through agarose gel electrophoresis (0.8% gel) [6].

Sequencing Approaches:

- 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing: Amplify the V3-V4 hypervariable regions using archaeal and bacterial primers (515F and 806R) in triplicate reactions. Pool PCR products, clean with Ampure XP magnetic beads, and sequence on Illumina MiSeq platform with V3 chemistry (2×300 bp) [6].

- Shotgun Metagenomics: Use 1 ng of genomic DNA with Illumina Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit to construct paired-end libraries with 500 bp insert size. Perform paired-end sequencing (2×151 bp) on Illumina platforms [5].

- Hybrid Sequencing: For comprehensive analysis, combine short-read (Illumina) and long-read (Oxford Nanopore or PacBio) technologies to improve assembly quality and resolve mobile genetic elements [5].

Bioinformatic Analysis Workflow

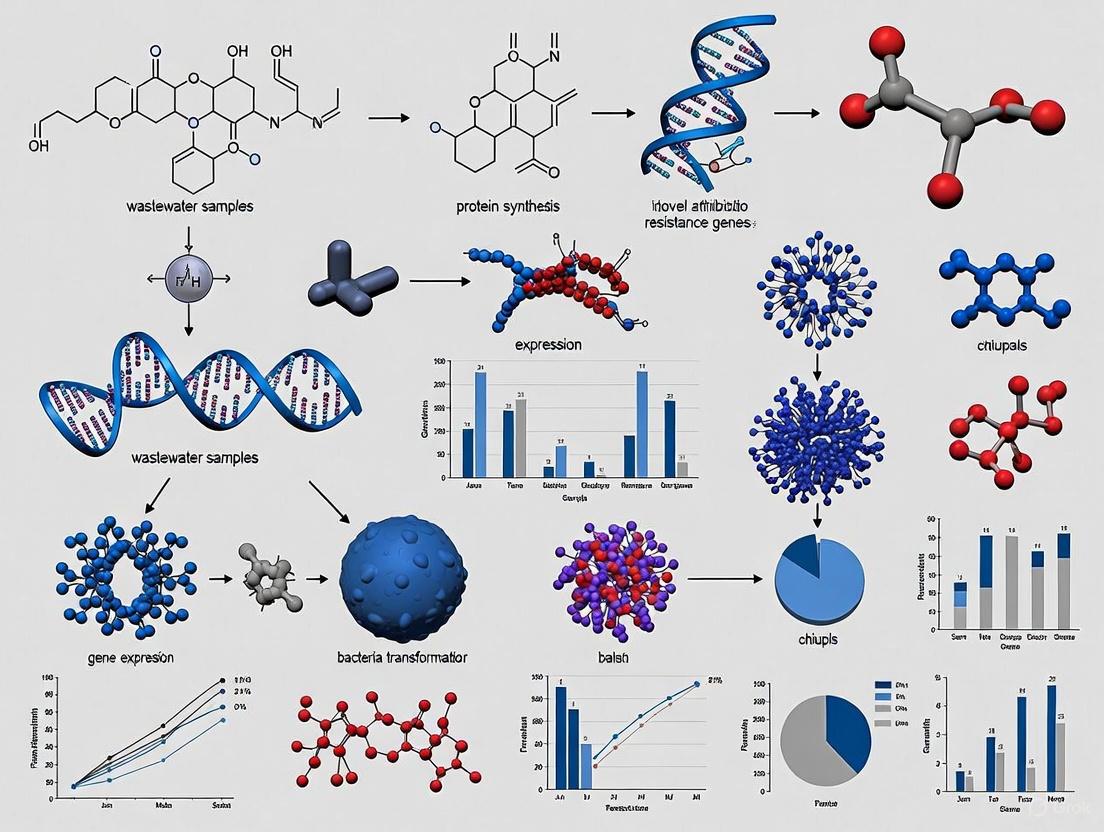

The following workflow diagram illustrates the comprehensive process for resistome analysis from sample collection to data interpretation:

Key Analytical Steps:

- Quality Control and Preprocessing: Use tools like FastQC and Trimmomatic to assess read quality and remove adapter sequences [3].

- Assembly and Gene Prediction: Perform metagenomic assembly using MEGAHIT or metaSPAdes. Predict open reading frames (ORFs) from contigs longer than 1 kb using Prodigal or similar tools [3].

- ARG Identification and Annotation: Annotate predicted ORFs against curated ARG databases (e.g., CARD, ARG-OAP) using BLAST or Diamond with optimized e-value thresholds [2].

- Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs): Reconstruct MAGs using binning tools like MetaBAT2, CheckM for quality assessment, and categorize using GTDB-Tk [2].

- Mobile Genetic Element Analysis: Identify plasmids, integrons, and transposons associated with ARGs using tools like MobileElementFinder and IntegronFinder [5].

- Statistical Analysis and Visualization: Conduct multivariate statistics (PERMANOVA, PCoA) in R with vegan package, and create visualizations using ggplot2 [3].

Interconnections and Transmission Dynamics

Pathways of Resistome Exchange

The interconnectivity of human, animal, and environmental compartments creates multiple pathways for ARG dissemination. Wastewater systems serve as critical convergence points where resistance genes from various sources mix and potentially recombine. A global analysis of wastewater treatment plants demonstrated that ARG composition strongly correlates with bacterial taxonomic composition, with Chloroflexi, Acidobacteria and Deltaproteobacteria identified as major ARG carriers [3]. The study also found that 57% of 1,112 recovered high-quality genomes possessed putatively mobile ARGs, highlighting the extensive potential for horizontal transfer [3].

The role of mobile genetic elements (MGEs) in facilitating the spread of ARGs cannot be overstated. Research on hospital wastewater revealed strong co-occurrence patterns between ARGs and MGEs, particularly for genes conferring resistance to sulfonamide, glycopeptide, macrolide, tetracycline, aminoglycoside, and β-lactam antibiotics [5]. The identification of novel genomic islands, such as the GIAS409 variant carrying transposases and heavy metal resistance operons, reveals significant mechanisms for co-selection and dissemination of resistance determinants [5].

Environmental and Socioeconomic Drivers

Multiple abiotic and biotic factors influence the development and spread of antimicrobial resistance across One Health compartments. Research indicates that resistome variations appear to be driven by a complex combination of stochastic processes and deterministic abiotic factors [3]. Climate change represents an emerging driver, with evidence that rising temperatures can accelerate horizontal gene transfer and expand the geographic spread of water-borne pathogens [1].

Socioeconomic factors and infrastructure deficiencies significantly impact AMR transmission dynamics. Studies in Northwest Ecuador demonstrated that inadequate water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) infrastructure increases exposure to antimicrobial resistance [7]. Researchers found that pregnant women with access to sewer systems or septic tanks and piped drinking water had fewer unique ARGs compared to those without these infrastructures [7]. Similarly, longer duration of drinking water access was associated with lower total ARG abundance [7].

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Resistome Analysis

| Category | Specific Product/Platform | Application in Resistome Research |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit | Optimal DNA extraction from fecal samples |

| PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit | DNA extraction from complex environmental matrices | |

| Library Preparation | Illumina Nextera XT DNA Library Prep Kit | Metagenomic library construction for Illumina platforms |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina MiSeq/NovaSeq | Short-read sequencing for high-throughput metagenomics |

| Oxford Nanopore Technologies | Long-read sequencing for resolving mobile genetic elements | |

| Bioinformatic Tools | MetaPhlAn 3.0 | Metagenomic taxonomic profiling using clade-specific markers |

| ARGs-OAP v3.0 | Online analysis pipeline for antibiotic resistance genes | |

| DADA2 (QIIME2 pipeline) | 16S rRNA amplicon sequence analysis and OTU clustering | |

| Reference Databases | CARD | Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database |

| SILVA 132 | Reference database for 16S rRNA gene taxonomic assignment | |

| GTDB | Genome Taxonomy Database for MAG classification |

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

Novel Intervention Strategies

Conventional wastewater treatment methods demonstrate limited efficacy in removing ARGs, with one study reporting only 42% ARG removal efficiency [5]. This deficiency has stimulated research into advanced treatment technologies, particularly nanotechnology-based approaches that show promise for eliminating antibiotic-resistant bacteria and genes from municipal effluents [8].

Various nanomaterials, including graphene-based structures, carbon nanotubes, noble metal nanoparticles (gold and silver), silicon and chitosan-based nanomaterials, as well as titanium and zinc oxide nanomaterials, demonstrate potent antimicrobial effects [8]. These materials offer multiple mechanisms of action, including photocatalytic degradation of genetic material, physical disruption of bacterial membranes, and generation of reactive oxygen species. Additionally, nanosensors utilizing these nanomaterials enable precise detection and monitoring of ARB and ARGs in wastewater streams [8].

Integrated Surveillance Frameworks

The future of resistome research lies in developing integrated surveillance systems that capture data across the entire One Health spectrum. Wastewater surveillance (WWS) has emerged as a powerful approach for monitoring AMR across entire communities or WWTP catchments [4]. A comprehensive review identified 177 reports on this topic between 2014 and 2024, with 136 (76.8%) appearing after 2019, indicating rapidly growing interest in this methodology [4] [9].

Recent technological advances have enabled more sophisticated monitoring approaches. Digital PCR (dPCR) and multiplex ligation-dependent amplification (dMLA) assays provide enhanced quantification of specific ARG targets [4]. Meanwhile, whole-genome sequencing (WGS) and metagenomic assembly facilitate the reconstruction of complete resistance elements and their genomic context, enabling better risk assessment of novel ARGs [5] [2].

The development of machine learning models that incorporate factors such as antimicrobial use in food animal production, climate patterns, and infrastructure quality will enhance our ability to predict emerging AMR threats [2]. However, these models require more direct measurements of antimicrobial use and microbial sampling across under-resourced regions to improve their predictive accuracy and global applicability [2].

The One Health perspective provides an essential framework for understanding the complex dynamics of antimicrobial resistance gene flow among human, animal, and environmental compartments. Wastewater systems serve as critical observation points where these interactions converge and become measurable. Through advanced metagenomic approaches and integrated surveillance strategies, researchers can identify novel resistance genes, track their dissemination pathways, and assess their potential risk to human and animal health.

The fight against AMR requires sustained global commitment to One Health stewardship across the entire antimicrobial lifecycle—from research and development to appropriate use and disposal. By maintaining this comprehensive perspective and leveraging emerging technologies, the scientific community can develop more effective strategies to preserve antimicrobial efficacy and protect global health security for future generations.

Wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) represent critical interfaces between human activities and the natural environment, functioning as significant reservoirs for antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs). These facilities receive wastewater from diverse sources including homes, hospitals, and pharmaceutical manufacturing, creating unique ecological niches where selective pressures from antibiotic residues, heavy metals, and other contaminants promote the evolution and dissemination of antimicrobial resistance [3] [10]. The activated sludge process, while effective for nutrient removal, maintains high microbial density and diversity under conditions that favor horizontal gene transfer (HGT), effectively making WWTPs "bioreactors" for the development and propagation of ARGs [10]. Understanding the mechanisms driving ARG development and transfer in these environments is crucial for mitigating the global spread of antibiotic resistance, identified by the World Health Organization as a major threat to public health [11].

This technical review examines the complex interplay of biotic and abiotic factors that establish WWTPs as evolutionary crucibles for ARG development. We analyze the genetic mechanisms facilitating HGT, identify key ARG carriers, quantify the distribution of high-risk resistance elements across geographic regions, and evaluate the efficacy of current treatment technologies in mitigating ARG dissemination. The findings presented herein aim to inform research strategies for novel ARG identification and support the development of targeted interventions to disrupt resistance transmission pathways.

Drivers of ARG Development and Horizontal Gene Transfer in WWTPs

Environmental Selection Pressures

The WWTP environment subjects microbial communities to multiple, simultaneous selection pressures that drive the development and enrichment of ARGs:

Antibiotic Residues: Partial metabolism of administered antibiotics (30-90% excreted by humans, 75% by animals) results in continuous influx of antibiotic residues into WWTPs, exerting direct selective pressure for resistance mechanisms [12].

Heavy Metals and Biocides: Co-selection from heavy metals (e.g., copper, zinc) and disinfectants promotes the maintenance and proliferation of ARGs through co-resistance (different resistance genes located together on the same genetic element) and cross-resistance (single genetic determinant conferring resistance to multiple antimicrobials) mechanisms [10] [13].

Emerging Contaminants: Microplastics and per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) have been increasingly implicated in enhancing HGT. Microplastics provide physical substrates for biofilm formation and facilitate ARG transfer by inducing oxidative stress and enriching MGE-harboring microorganisms in the "plastisphere" community [10]. Pharmaceuticals adsorbed onto microplastic surfaces can have synergistic effects, with studies showing significantly increased MGEs and ARGs compared to exposure to pharmaceuticals alone [10].

Table 1: Key Abiotic Drivers of ARG Development and HGT in WWTPs

| Driver Category | Specific Factors | Mechanism of Action | Impact on ARGs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibiotics | Residual fluoroquinolones, β-lactams, tetracyclines | Direct selective pressure for resistance mutations | Enrichment of specific ARG variants |

| Heavy Metals | Copper, zinc, mercury | Co-selection via linked resistance genes | Maintenance of multi-resistance gene clusters |

| Disinfectants | Chlorine, triclosan | Induction of oxidative stress and SOS response | Increased HGT frequency |

| Emerging Contaminants | Microplastics, PFAS | Biofilm formation, membrane permeability alteration | Enhanced conjugative transfer and transformation |

Mobile Genetic Elements as HGT Vectors

Horizontal gene transfer is primarily mediated by mobile genetic elements (MGEs) that facilitate the movement of ARGs between bacterial taxa through conjugation, transduction, and transformation:

Plasmids: Self-replicating extrachromosomal elements that frequently carry multiple ARGs alongside complete transfer machinery. Studies of activated sludge microbiomes have revealed that 57% of high-quality metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) carry putatively mobile ARGs, with Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes particularly prone to plasmid-mediated transfer [3] [13].

Integrons: Genetic platforms that capture and express gene cassettes, notably the clinically relevant class 1 integrons that frequently carry ARG cassettes. The intI1 integrase gene has been observed enriched up to 4.5-fold on microplastics incubated in WWTP environments, indicating their role in HGT acceleration [10].

Bacteriophages: Viruses that infect bacteria can facilitate ARG transfer through transduction. Recent research demonstrates that bacteriophages in WWTPs contribute to HGT through both specialized transduction and by lysing bacterial cells to release extracellular DNA that can be taken up by competent bacteria through transformation [14].

The interaction between these MGEs creates a complex network for gene flow, with analysis of 686 plasmids from wastewater systems revealing that only 3.36% were conjugation-type plasmids, suggesting that transduction and transformation may play more significant roles in HGT than previously recognized [14].

Microbial Ecological Factors

The unique ecological conditions of WWTPs create an environment conducive to HGT:

High Microbial Density and Diversity: Activated sludge systems maintain exceptionally high bacterial concentrations (typically 10³-10⁴ mg/L mixed liquor suspended solids) with diverse taxonomic composition, dramatically increasing intercellular contact frequencies and opportunities for gene exchange [3].

Trophic Interactions: Predation by protozoa and bacteriophage infection pressure may induce bacterial stress responses that increase competence for DNA uptake, thereby enhancing transformational gene transfer [10] [14].

Biofilm Formation: The floccular structure of activated sludge provides structured microenvironments where closely associated bacteria can form stable conjugation junctions and share genetic material, with extracellular polymeric substances offering protection from environmental stressors [11].

Global Distribution and Diversity of ARGs in WWTPs

Core Resistome of Wastewater Treatment Plants

Global analysis of 226 activated sludge samples from 142 WWTPs across six continents has revealed a conserved set of 20 core ARGs present in all facilities, accounting for 83.8% of total ARG abundance [15] [3]. The most abundant ARGs confer resistance to critically important antibiotic classes:

- TetracyclineResistanceMFSEffluxPump (15.2% of total ARG abundance)

- ClassB β-lactamase (13.5%)

- vanT gene in vanG cluster (glycopeptide resistance, 11.4%)

When aggregated by resistance mechanism, genes encoding antibiotic inactivation predominate (55.7%), followed by antibiotic target alteration (25.9%) and efflux pumps (15.8%) [3]. This distribution reflects the strong selective advantage of enzymatic resistance mechanisms in wastewater environments where extracellular enzymes can provide community-level protection.

Table 2: Global Distribution of High-Risk ARGs in WWTPs

| ARG | Drug Class | Primary Mechanisms | Geographic Distribution | Transfer Potential |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ermF | Macrolides | rRNA methylation | Widely distributed in Asia and the Americas | High (facilitated by MGEs) |

| tla-1 | Tetracyclines | Ribosomal protection | Primarily detected in Asia | High (facilitated by MGEs) |

| sul1 | Sulfonamides | Target bypass | Global distribution | Moderate-High (associated with class 1 integrons) |

| tet(M) | Tetracyclines | Ribosomal protection | Global distribution | Moderate (chromosomal and plasmid locations) |

| blaOXA | β-lactams | Antibiotic inactivation | Global distribution | Variable (multiple variants) |

Geographic and Habitat-Specific Patterns

Significant geographic variation in ARG composition has been observed despite the conserved core resistome:

Continental Divergence: PERMANOVA analysis reveals significant differences (p < 0.05) in resistome composition between all paired continents, with PCoA showing strong regional separation at the individual gene level [3]. Asia exhibits significantly higher ARG richness than other continents except Africa, suggesting regional influences on resistance diversity [15] [3].

Regional Patterns: Specific ARGs demonstrate distinct geographic distributions. The ermF gene is widely distributed in Asia and the Americas, while tla-1 is primarily detected in Asia; both are barely detected in European WWTPs [16]. These patterns may reflect regional differences in antibiotic usage, industrial discharge, or microbial community structure.

Habitat Specificity: Comparative resistome analysis demonstrates that WWTP communities are distinct from human gut and ocean microbiomes but show similarity to sewage and soil resistomes, suggesting environmental connectivity and shared selection pressures [3]. This indicates a degree of ecological isolation between clinical and wastewater resistance pools, though with significant overlap through sewage inputs.

Key Bacterial Hosts of ARGs

Microbial taxa belonging to the Proteobacteria phylum, particularly the classes Deltaproteobacteria and Gammaproteobacteria, serve as major ARG reservoirs in WWTPs [3] [13]. Metagenome-assembled genome analysis has identified several bacterial families as prominent ARG carriers:

Pseudomonadaceae: Multiple genera within this family demonstrate exceptional multi-resistance capabilities, frequently harboring ARGs alongside biocide resistance genes and virulence factors, designating them as "super-carriers" of resistance traits [13].

Moraxellaceae and Xanthomonadaceae: These families are significant hosts for aminoglycoside and β-lactam resistance genes, with Acinetobacter species (Moraxellaceae) frequently carrying carbapenem resistance determinants [13].

Enterobacteriaceae: Known pathogens including Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter nosocomialis, and Escherichia coli persist as abundant multi-drug resistant organisms in wastewater, comprising approximately 10.2% of the microbial community in raw influent [13].

Notably, Chloroflexi and Acidobacteria — often considered environmental bacteria rather than human pathogens — are also identified as major ARG carriers in global analyses, highlighting the potential for environmental bacteria to serve as reservoirs for clinically relevant resistance genes [3].

Methodologies for Investigating ARGs and HGT in WWTPs

Microfluidic-Based Mini-Metagenomics Approach

Conventional metagenomic sequencing faces limitations in complex environmental samples like activated sludge due to extremely high microbial diversity that hinders complete genome binning [16]. Microfluidic-based mini-metagenomics addresses this challenge by partitioning complex samples into numerous simplified subsamples containing one or a few bacterial cells, enabling higher-quality genome assembly and more accurate association of ARGs with their bacterial hosts [16].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ARG and HGT Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| DNeasy PowerSoil Kit (Qiagen) | DNA extraction from complex environmental samples | Standardized DNA extraction from activated sludge [12] |

| Microfluidic devices | Partitioning complex samples into simplified subsamples | Mini-metagenomics for improved genome assembly [16] |

| NEBNext Ultra II Q5 master mix | Library preparation for high-throughput sequencing | Metagenomic sequencing of WWTP samples [12] |

| Illumina universal primers | Amplification of sequencing libraries | Shotgun metagenomics of wastewater resistomes [12] |

| AMPure beads | Purification and size selection of nucleic acids | Library clean-up post-amplification [12] |

Experimental Protocol: Microfluidic-Based Mini-Metagenomics

Sample Preparation: Activated sludge samples are pretreated to disaggregate flocs while maintaining cellular integrity, followed by serial dilution to optimize cell density for microfluidic partitioning [16].

Microfluidic Partitioning: Diluted samples are loaded into microfluidic devices that generate nanoliter-scale droplets, each potentially containing a single bacterial cell or simple community [16].

Whole Genome Amplification: Multiple displacement amplification (MDA) is performed within droplets using φ29 polymerase to amplify genomic DNA from individual cells [16].

Sequencing Library Preparation: Amplified DNA from droplets is pooled, fragmented, and converted into Illumina-compatible libraries using commercial kits (e.g., NEBNext Ultra II) [16].

Bioinformatic Analysis: Sequence data undergoes assembly, gene prediction, and annotation, with ARGs and MGEs identified through comparison to curated databases (e.g., CARD, INTEGRALL) [16].

This approach successfully identified ermF and tla-1 as high-transfer-potential ARGs in activated sludge, demonstrating its utility for uncovering ARG transfer dynamics that are obscured in conventional metagenomic studies [16].

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for microfluidic-based mini-metagenomics analysis of ARGs in WWTPs.

Global Resistome Profiling

The Global Water Microbiome Consortium (GWMC) has established standardized protocols for worldwide comparison of WWTP resistomes:

Experimental Protocol: Global Resistome Profiling

Standardized Sampling: Activated sludge samples are collected from full-scale WWTPs, immediately placed on ice, and processed uniformly to ensure comparability [3].

DNA Extraction and Sequencing: Community DNA is extracted using standardized kits (e.g., DNeasy PowerSoil), with libraries prepared for shotgun sequencing on Illumina platforms (HiSeq 4000) to generate ~12.3 Gb per sample [3] [12].

Contig Assembly and ORF Prediction: Sequence reads are assembled into contigs (>1 kb) followed by prediction of non-redundant open reading frames (ORFs) [3].

ARG Annotation: ORFs are compared against ARG databases (e.g., using ARG-ANNOT, CARD) with manual curation to identify putative resistance genes [3].

Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs): High-quality MAGs are reconstructed from metagenomic assemblies to associate ARGs with specific taxonomic groups and determine chromosomal versus mobile locations [3].

Statistical Analysis: Diversity metrics, ordination techniques (PCoA), and correlation analyses are applied to identify resistome patterns and their relationships to environmental variables [3].

This standardized approach enabled the identification of 20 core ARGs present in all WWTPs analyzed and revealed that temperature and urban population size significantly promote ARG enrichment, while pH and sludge retention time exert suppressive effects [3].

Interventional Strategies: Current and Emerging Approaches

Advanced Treatment Technologies

Conventional wastewater treatment processes provide incomplete removal of ARGs and ARBs, necessitating advanced treatment strategies:

Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOPs): Ozonation, UV/H₂O₂, and photocatalytic oxidation generate hydroxyl radicals that damage bacterial DNA, reducing the potential for HGT. These methods typically achieve 1-3 log reductions in ARG abundance but exhibit variable efficacy depending on specific ARGs and operational parameters [11].

Membrane Filtration: Ultrafiltration and reverse osmosis provide effective physical barriers for bacterial cell removal, achieving >4 log reduction of ARBs. However, they are less effective for extracellular DNA removal unless combined with enzymatic or oxidative treatments [11].

Constructed Wetlands: Nature-based solutions function through combined mechanisms including filtration, adsorption, microbial degradation, and plant uptake. Studies show vertical flow constructed wetlands followed by UV disinfection reduce ARG abundance from 58 genes in influent to 21 in effluent [12].

Anaerobic Digestion: Upflow anaerobic sludge blanket (UASB) reactors operated at 10.5 hours hydraulic retention time demonstrate moderate ARG removal, particularly when coupled with post-treatment wetlands [12].

Comparative Performance of Treatment Technologies

Evaluation of parallel treatment trains reveals significant differences in ARG removal efficacy:

Conventional vs. Advanced Treatment: Comparative metagenomic analysis shows conventional trickling filter technology reduces ARGs from 58 in influent to 46 in effluent, while advanced systems integrating UASB, constructed wetlands, and UV/anodic oxidation achieve greater reduction to 21 ARGs [12].

Disinfection Methods: Chlorination effectively inactivates ARBs but often fails to eliminate ARGs and may even select for resistant populations due to differential susceptibility among bacterial taxa. UV irradiation demonstrates superior performance for DNA damage but requires sufficient fluence to fragment ARGs [11].

Technology Integration: The most effective approaches combine multiple treatment mechanisms. For example, anaerobic digestion followed by constructed wetlands and UV/AOP disinfection achieves synergistic effects through sequential physical, biological, and chemical ARG removal mechanisms [12].

Figure 2: Comparative ARG removal in conventional versus advanced wastewater treatment processes.

Wastewater treatment plants function as significant evolutionary crucibles where diverse selection pressures, high microbial densities, and abundant mobile genetic elements converge to drive the development and dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes. The identification of a global core resistome present in all WWTPs highlights the ubiquitous nature of this challenge, while geographic variations in ARG distribution reflect regional influences including antibiotic usage patterns, industrial discharge, and environmental conditions.

Critical research gaps remain in understanding the complex interactions between emerging contaminants (e.g., microplastics, PFAS) and HGT frequency, the role of bacteriophage-mediated transduction in ARG spread, and the efficacy of integrated treatment technologies in disrupting ARG transmission pathways. Future research should prioritize the development of standardized methodologies for ARG risk assessment, elucidate the mechanisms by which specific environmental factors modulate HGT efficiency, and validate innovative treatment approaches that specifically target the mobile gene pool rather than just bacterial hosts.

The insights generated from advanced methodologies like microfluidic-based mini-metagenomics and global resistome profiling provide a foundation for evidence-based interventions to mitigate ARG dissemination from WWTPs. As antibiotic resistance continues to pose grave threats to public health worldwide, understanding and addressing the role of wastewater treatment systems as hotspots for resistance evolution remains an urgent research priority.

Global Surveys Reveal a Core and Diverse Resistome in Activated Sludge

Activated sludge (AS) in wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) is a critical reservoir for antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs), posing a significant challenge to global public health. Recent global metagenomic surveys reveal that these environments harbor a "core resistome"—a set of ARGs ubiquitous across all sampled plants—alongside a highly diverse "rare resistome" that carries substantial risk due to its mobility and association with pathogens. This whitepaper synthesizes findings from large-scale studies across six continents, detailing the composition, drivers, and distribution of this resistome. It further provides standardized methodologies for resistome characterization, essential for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to identify novel ARGs and mitigate the spread of antimicrobial resistance (AMR).

Wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) receive wastewater from diverse sources, including domestic, industrial, and pharmaceutical effluents, making them immense reservoirs for antibiotics, antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB), and ARGs. The activated sludge process, a microbial enrichment system, is particularly conducive to the proliferation and exchange of ARGs due to high bacterial density, diversity, and activity [17]. It is estimated that WWTPs collect sewage from approximately 52% of the global population, underscoring their significance as a key interface between human activities and the natural environment [3]. Understanding the structured diversity of the resistome in AS is a critical step within the broader thesis of identifying novel, clinically relevant ARGs and developing strategies to curb their dissemination.

Global Diversity and Distribution of the Activated Sludge Resistome

The Core and Rare Resistome

Global metagenomic analysis of 226 AS samples from 142 WWTPs across six continents has delineated the resistome into two key components: the core resistome and the rare resistome.

- The Core Resistome: A study identified a core set of 20 ARGs present in every AS sample analyzed. Despite their low taxonomic diversity, these core genes accounted for a dominant 83.8% of the total ARG abundance found in the global survey [3]. This core resistome is characterized by high abundance and stability across different environments.

- The Rare Resistome: In contrast, a study of the Yangtze River ecosystem (encompassing water, sediment, and bank soil) found that the rare resistome—ARGs not universally present—exhibited higher diversity and greater risk than the core resistome. The rare resistome is more frequently carried on plasmids, suggesting stronger transfer potential and a closer association with mobile genetic elements (MGEs) [18].

Table 1: Core Resistome Profile in Global Activated Sludge [3]

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Number of Core ARGs | 20 |

| Contribution to Total Abundance | 83.8% |

| Top ARGs by Abundance | TetracyclineResistanceMFSEffluxPump (15.2%), ClassB (13.5%), vanT gene in vanG cluster (11.4%) |

| Dominant Resistance Mechanisms | Antibiotic inactivation (55.7%), antibiotic target alteration (25.9%), efflux pumps (15.8%) |

| Dominant Drug Classes Targeted | Beta-lactam (46.5%), Glycopeptide (24.5%), Tetracycline (16.2%) |

Table 2: Contrasting Core and Rare Resistomes [18]

| Characteristic | Core Resistome | Rare Resistome |

|---|---|---|

| Diversity | Low | High |

| Relative Abundance | High | Low |

| Genetic Location | Primarily chromosomes | Primarily plasmids |

| Mobility & Transfer Potential | Low | High |

| Association with Pathogens | Lower | Higher (22 ARGs of high clinical concern identified) |

| Typical Genes | Multidrug efflux pumps, bacitracin resistance | aac(6')-I, sul1, tetM |

Global Biogeography and Drivers

The composition of ARGs differs significantly across geographic regions. A principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) at the gene level revealed a strong regional separation of resistomes across continents [3]. This geographic distribution is influenced by a complex combination of stochastic processes and deterministic abiotic factors.

Notably, the total abundance of ARGs does not vary significantly across continents, but richness and diversity are higher in Asia compared to other regions [3]. Furthermore, the AS resistome is distinct from those found in the human gut and oceans but shows greater similarity to sewage and soil resistomes, indicating interconnections between these environments [3].

Reservoirs and Hosts of ARGs

The primary carriers of ARGs in AS are bacterial taxa, with major phyla including Chloroflexi, Acidobacteria, and Deltaproteobacteria identified as major carriers [3]. The strong correlation between bacterial community structure and resistome composition (Procrustes analysis, ( p < 0.001 )) confirms that the taxonomy of the microbiome is a key determinant of the ARG profile [3].

Beyond bacteria, viruses have been identified as crucial reservoirs of ARGs in AS systems. Metagenomic studies of viral genomes in AS have revealed a high abundance of ARGs, suggesting that viruses are key players in storing and facilitating the horizontal gene transfer of resistance traits [19].

Methodologies for Resistome Characterization

A consistent and rigorous methodological pipeline is fundamental for comparative global surveys and the identification of novel ARGs.

Standardized Metagenomic Workflow

The following workflow, employed by the Global Water Microbiome Consortium (GWMC), provides a robust framework for resistome analysis [3].

Diagram 1: Experimental Workflow for Resistome Analysis

Step 1: Sample Collection and DNA Sequencing

- Protocol: Collect activated sludge samples from a globally representative set of WWTPs. Immediately preserve samples as per protocol (e.g., freezing at -80°C). Extract community DNA using a standardized kit (e.g., DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit). Perform shotgun metagenomic sequencing on platforms like Illumina NovaSeq to a depth of approximately 12.3 Gb per sample [3].

- Rationale: Consistent protocols at this stage prevent biases and enable valid cross-continental comparisons.

Step 2: Bioinformatics Processing

- Protocol: Quality-trim raw sequencing reads using tools like Trimmomatic. Assemble high-quality reads into contigs (>1 kb) using metaSPAdes. Predict open reading frames (ORFs) from assembled contigs with prodigal [3].

- Rationale: This generates the fundamental data units (contigs, ORFs) for downstream annotation and analysis.

Step 3: ARG Annotation and Quantification

- Protocol: Annotate predicted ORFs against a curated ARG database (e.g., CARD, ARGs-OAP) using homology-based tools like BLAST or DeepARG. Normalize ARG abundance to copies per bacterial cell to account for variations in microbial density and sequencing depth [3] [2].

- Rationale: Homology-based searches allow for the identification of both known and novel ARG variants. Normalization is critical for accurate abundance comparisons.

Step 4: Host Identification and Mobility Assessment

- Protocol: Bin contigs into Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs) using tools like MaxBin or MetaBAT. CheckM can be used to assess MAG quality. To assess mobility, annotate contigs for MGEs (plasmids, integrons, transposons) and analyze the co-localization of ARGs and MGEs [3] [20].

- Rationale: Linking ARGs to their microbial hosts and genetic context is essential for evaluating transmission risk and ecological impact.

Advanced Screening Methods

- Functional Metagenomics: This culture-independent method involves cloning environmental DNA into an expression vector, transforming it into a heterologous host (e.g., E. coli), and selecting for clones that confer resistance to antibiotics. The cloned DNA is then sequenced to identify novel resistance genes without prior sequence knowledge [21].

- Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) for Novel Gene Families: For discovering divergent members of ARG families (e.g., novel β-lactamases), HMMs constructed from multiple sequence alignments of known families can be used to probe metagenomic data, as demonstrated by the discovery of 478 novel β-lactamases in Arctic sediments [20].

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Resources

| Item / Resource | Function / Application | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kit | Isolation of high-quality community DNA from complex sludge. | DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit |

| ARG Reference Database | Homology-based annotation and classification of ARGs. | CARD, ARGs-OAP v3.0 [2] |

| Bioinformatics Software | Data processing, assembly, binning, and analysis. | metaSPAdes (assembler), CheckM (MQA), Prokka (annotation) |

| Metagenomic Library Kit | Functional screening for novel ARGs. | Commercial vector-host systems (e.g., in E. coli) |

| Risk Assessment Framework | Ranking the human health risk of identified ARGs. | Integrates ARG mobility, clinical importance, and host pathogenicity [2] |

Discussion and Future Perspectives

The delineation of a core and rare resistome in activated sludge refines our understanding of AMR dynamics. The high-abundance, low-diversity core resistome may represent genes intrinsic to the ecosystem's microbial community, while the highly diverse, mobile, and clinically concerning rare resistome represents the frontline of emerging resistance threats [3] [18]. The strong correlation between resistome and microbiome structures indicates that abiotic factors (e.g., temperature, pH, antibiotic levels) likely shape the resistome indirectly by selecting for specific bacterial taxa that carry characteristic ARGs [3] [22].

Future research must focus on several key areas:

- Standardization: The success of global consortia like the GWMC highlights the need for continued methodological consistency to enable longitudinal surveillance.

- Linking Environment to Clinic: Enhanced tracing of specific, high-risk ARGs (e.g., plasmid-borne

sul1ortetMfrom the rare resistome) from WWTPs to clinical settings is crucial for a complete One Health risk assessment. - Intervention Strategies: Research into advanced treatment processes (e.g., advanced oxidation, ozonation, membrane filtration) should be prioritized to evaluate their efficacy in removing not just the abundant core resistome but also the high-risk rare resistome [17].

In conclusion, global surveys have provided an unprecedented map of the activated sludge resistome, revealing a stable core and a dynamic, high-risk rare component. The application of consistent, sophisticated metagenomic protocols is essential for identifying novel resistance genes and understanding their trajectories, ultimately informing public health actions and antibiotic stewardship policies on a global scale.

The relentless expansion of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) presents a critical global health threat. In the fight against resistant infections, the environment plays a crucial role as a reservoir and breeding ground for antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs). Wastewater systems, particularly those receiving effluent from hospitals and communities, are significant hotspots for the evolution and dissemination of ARGs. This whitepaper synthesizes recent, groundbreaking research demonstrating the global scale of novel ARG discovery, from the remote sediments of the Arctic to the complex chemical milieu of hospital wastewater. It provides a technical guide for researchers and drug development professionals, detailing the methodologies and analytical frameworks used to identify and characterize these genes, which is essential for risk assessment and the development of novel countermeasures.

Global Distribution of ARGs in Wastewater Systems

Wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) are convergence points for ARGs from human and animal sources. A landmark 2025 study analyzing activated sludge from 142 WWTPs across six continents provides a comprehensive baseline of the global wastewater resistome [3].

Table 1: Core Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Global Activated Sludge (2025 Study)

| Rank | ARG Identifier | Primary Drug Class Targeted | Average Relative Abundance (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | TetracyclineResistanceMFSEffluxPump | Tetracycline | 15.2% |

| 2 | ClassB | Beta-lactam | 13.5% |

| 3 | vanT (vanG cluster) | Glycopeptide | 11.4% |

| 4 | Not Specified | Beta-lactam | 9.8% |

| 5 | Not Specified | Tetracycline | 7.5% |

| ... | ... | ... | ... |

| Core Set Total (20 Genes) | 83.8% |

This research identified a core set of 20 ARGs that were present in every WWTP sample analyzed, constituting 83.8% of the total ARG abundance [3]. The composition of ARGs was found to be distinct from other environments, such as the human gut and oceans, and was strongly correlated with the local bacterial community structure, with phyla like Chloroflexi, Acidobacteria, and Deltaproteobacteria being major ARG carriers [3]. Furthermore, the abundance of ARGs showed a positive correlation with mobile genetic elements (MGEs), with 57% of recovered high-quality genomes containing putatively mobile ARGs, highlighting a significant potential for horizontal gene transfer [3].

Case Study 1: Hospital Effluents as ARG Reservoirs

Hospital wastewater (HWW) is a critical surveillance point due to the high density of antibiotic residues and antibiotic-resistant bacteria. A meta-analysis of HWW from multiple countries confirmed that effluents from healthcare facilities contribute high levels of diverse ARGs to the aquatic environment [23].

Key Findings and Quantitative Analysis

Hospital effluents show a unique resistome profile, often characterized by an overabundance of genes resistant to last-resort antibiotics like carbapenems and glycopeptides [23]. A spatiotemporal study of a UK hospital effluent found that gene and transcript abundances were highly correlated (ρ = 0.9, p<0.0001), and that two β-lactamase genes, blaGES and blaOXA, were consistently overexpressed in all samples [24]. This high expression was linked to hospital antibiotic usage patterns over time, and the effluent was confirmed to contain antibiotic residues, creating a persistent selective pressure [24].

Table 2: Prevalent ARG Types in Hospital Wastewater Effluents

| Drug Class | Example ARGs | Relative Abundance in HWW | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbapenems | blaKPC, blaNDM | High (>10⁻⁴ copies/16S rRNA) | Associated with last-resort treatments. |

| Sulfonamides | sul1, sul2 | High (>10⁻⁴ copies/16S rRNA) | Often linked to mobile genetic elements. |

| Tetracyclines | tet(M), tet(O) | High (>10⁻⁴ copies/16S rRNA) | Abundance reported to be increasing. |

| Extended-Spectrum β-Lactams | blaCTX-M, blaTEM | Variable | Abundance reported to be decreasing. |

| Glycopeptide | vanA | High (>10⁻⁴ copies/16S rRNA) | Targets last-resort drug vancomycin. |

| Mobile Genetic Elements | intI1 | High | Facilitates horizontal gene transfer. |

Experimental Protocol: Metagenomic & Metatranscriptomic Analysis of HWW

The following workflow details the methodology used in the cited hospital effluent study [24]:

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Sample Collection: Collect grab or composite samples from the hospital effluent source (e.g., combined sewage pit) into sterile containers. Preserve immediately on ice or at -80°C until processing [24].

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Perform parallel extraction of high-quality genomic DNA and total RNA from a standardized volume or biomass of wastewater. RNA extracts require DNase treatment to remove genomic DNA contamination [24].

- Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Metagenomics (DNA): Prepare sequencing libraries from the extracted DNA. Sequencing is typically performed using shotgun metagenomics on an Illumina or similar platform to achieve high depth (e.g., 50-100 million reads per sample) [24] [25].

- Metatranscriptomics (RNA): First, synthesize cDNA from the extracted RNA. Then, prepare sequencing libraries from the cDNA for shotgun RNA sequencing. This captures the community-wide gene expression profile [24].

- Bioinformatic Processing: Process raw sequencing reads through a quality control pipeline (e.g., Trimmomatic). Quality-controlled reads are then assembled into contigs using tools like MEGAHIT or metaSPAdes. Open Reading Frames (ORFs) are predicted from the assembled contigs [24] [3].

- ARG Annotation: Predicted ORFs are compared against curated antibiotic resistance databases, such as the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD), using tools like the Search Engine for Antimicrobial Resistance (SEAR) or DeepARG, to identify and quantify ARGs [24] [26].

- Data Integration and Analysis: ARG abundance (from DNA) and expression levels (from RNA) are correlated using statistical methods (e.g., Spearman correlation). Abundance can be normalized to 16S rRNA gene copies for cross-study comparisons. Data is integrated with metadata, such as local antibiotic consumption data, to identify potential drivers [24] [23].

Case Study 2: Novel Gene Discovery in the Arctic

The Arctic, once considered a pristine environment, is now recognized as a significant reservoir for AMR. A pivotal 2025 study on the sediments of Adventfjorden in Svalbard revealed a vast and previously uncharacterized resistome, demonstrating the global reach of antibiotic resistance [27].

Key Findings and Quantitative Analysis

This research uncovered 888 clinically relevant ARGs, including those conferring resistance to last-resort antibiotics like carbapenems, colistin, and vancomycin [27]. Most strikingly, computational models identified 478 novel β-lactamases belonging to 217 novel families. Host prediction analysis successfully linked 69 of these novel families to specific bacteria prevalent in the Arctic sediments [27]. This finding is critical as it shows these novel resistance genes are not merely present but are hosted by native microbial communities. The source of this resistome is attributed to a combination of human influence (e.g., wastewater discharge from local communities), the input of ARBs from preserved permafrost due to glacial melting, and horizontal gene transfer [27] [28].

Table 3: Novel ARG Discovery in High Arctic Fjord Sediments

| Metric | Finding | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Clinically Relevant ARGs | 888 genes identified | Arctic is a reservoir for diverse resistance threats. |

| Novel β-lactamase Families | 217 families discovered | Vast, untapped diversity of β-lactam resistance. |

| Novel β-lactamase Genes | 478 genes discovered | Potential for new resistance mechanisms. |

| Novel Bacterial Taxa (MAGs) | >97% of 644 MAGs were novel taxa | Novel hosts for novel ARGs. |

| Primary Driver of Discovery | Computational modeling with HMMs | Essential tool for finding distant ARG homologs. |

Experimental Protocol: Metagenomic Mining for Novel ARGs

The discovery of novel genes in low-abundance environmental samples requires a methodology that moves beyond standard alignment-based techniques.

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Sample Collection and DNA Extraction: Collect sediment cores from the target fjord. Subsample and perform intensive mechanical and chemical lysis to extract community DNA from the complex sediment matrix [27].

- Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing: Sequence the extracted DNA using a high-throughput platform (e.g., Illumina) to generate a deep metagenomic library, which is crucial for assembling genomes from low-abundance organisms [27].

- Metagenomic Assembly and Binning: Assemble quality-filtered reads into long contigs. These contigs are then binned into Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs) based on sequence composition and abundance. This step is vital for linking ARGs to their microbial hosts and assessing novelty at the taxonomic level [27].

- Novel ARG Discovery with Hidden Markov Models (HMMs):

- Standard Annotation: For comparison, ORFs from contigs and MAGs are screened against known ARG databases using BLAST-based tools [27].

- HMM-Based Profiling: To find novel genes that are distantly related to known ARGs, profile Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) of known resistance gene families are used. HMMs are statistical models of the consensus of a multiple sequence alignment and are highly effective at detecting remote homologs that would be missed by simple sequence similarity searches (e.g., BLAST) [27].

- A sequence is considered a novel family member if it scores above the trusted cutoff for the HMM but has very low identity to any known sequence in public databases.

- Host Assignment and Curation: Novel ARGs identified on contigs are assigned to a host MAG if the contig is included within that MAG's bin. This allows researchers to determine the phylogenetic identity of the novel gene's host and confirm that these genes are integrated into the genomes of novel Arctic bacteria, not just transient genetic material [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Methods for ARG Research

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Wastewater Resistome Studies

| Category / Item | Specific Examples / Methods | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction | Kits for soil/sludge (e.g., DNeasy PowerSoil), with bead-beating. | Efficiently lyses tough environmental microbes for high-yield, inhibitor-free DNA/RNA. |

| Sequencing Technology | Illumina platforms (MiSeq, NextSeq); PacBio; Oxford Nanopore. | Provides high-throughput, accurate sequencing for metagenomics (Illumina) or long reads for assembly (PacBio/Nanopore) [25]. |

| Targeted Enrichment Panels | AmpliSeq for Illumina Antimicrobial Resistance Panel; Respiratory Pathogen ID/AMR Panel. | Enables highly sensitive, cost-effective profiling of predefined sets of pathogens and ARGs from complex samples [25]. |

| Bioinformatics Databases | Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD); SEAR. | Curated repositories of reference ARG sequences for functional annotation of metagenomic data [26]. |

| Computational Tools | Hidden Markov Model (HMM) tools (HMMER); Assemblers (metaSPAdes, MEGAHIT); Binning tools (MaxBin). | Essential for novel gene discovery (HMM), reconstructing genomes from complex mixtures (assemblers & binning) [27]. |

| Phenotypic Validation | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) tests; Disk Diffusion; E-test. | Gold-standard methods to confirm the resistant phenotype of bacterial isolates in culture [26]. |

The evidence is clear: the hunt for novel antibiotic resistance genes must extend beyond the clinic into global environmental reservoirs. Hospital effluents, with their high concentration of antibiotics and resistant bacteria, are local epicenters for resistance selection. Conversely, the remote Arctic, impacted by climate change and global pollution, is a newly revealed reservoir of immense and novel genetic diversity, including hundreds of previously unknown β-lactamase families. The methodologies outlined—advanced metagenomics, metatranscriptomics, and sophisticated computational modeling like HMMs—are no longer niche but essential tools for public health surveillance and antimicrobial discovery. Sustaining and expanding wastewater and environmental surveillance capabilities, as argued for systems like the CDC's NWSS, is not merely an academic exercise but a critical investment in global health security, providing an early warning system for emerging resistance threats that know no borders [29]. For drug development professionals, this environmental resistome represents both a challenge and an opportunity: a challenge in the form of a vast, evolving genetic arsenal against our current antibiotics, and an opportunity to proactively identify new resistance mechanisms to target with next-generation therapeutics.

Cutting-Edge Techniques for Novel ARG Discovery and Reconstruction

The escalating global antimicrobial resistance (AMR) crisis necessitates innovative surveillance strategies that can identify both known and novel resistance determinants. Functional metagenomics has emerged as a powerful, culture-independent approach that enables unbiased screening for resistance phenotypes by directly cloning and expressing environmental DNA in heterologous hosts. This methodology is particularly transformative for wastewater research, as Wastewater Treatment Plants (WWTPs) are recognized as significant hotspots for the persistence and dissemination of antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) [30]. Unlike sequence-based methods that detect only known genes, functional metagenomics allows for the discovery of novel ARGs without prior sequence knowledge, making it indispensable for comprehensive resistome characterization.

The application of this technique within the "One Health" framework is crucial, as it bridges human, animal, and environmental health by tracking resistance reservoirs. Studies have demonstrated that sewage offers a convenient and ethical way to monitor AMR across large human populations, integrating waste from humans, animals, and their surrounding environment [31]. This review provides an in-depth technical guide to functional metagenomics, detailing its methodologies, applications, and significant findings in wastewater research, thereby equipping scientists with the tools to uncover the latent resistome threatening public health.

Quantitative Evidence: Global Insights from Functional Metagenomic Studies

Large-scale studies utilizing functional metagenomics have revealed critical insights into the abundance and distribution of ARGs in global sewage. A comprehensive analysis of 1240 sewage samples from 351 cities across 111 countries provided a direct comparison between acquired ARGs (known to be mobilized) and FG ARGs (identified via functional metagenomics) [31].

Table 1: Comparison of Acquired ARGs and FG ARGs in Global Sewage

| Metric | Acquired ARGs | Functional Metagenomics (FG) ARGs |

|---|---|---|

| Total ARGs Detected | 1,052 | 3,095 |

| Average Read Fragments per Sample | 0.015 million | 0.019 million |

| Geographical Distribution | Distinct regional patterns | More evenly distributed globally |

| Regional Variance Explained (Beta Diversity) | 12% | 7.4% |

| Association with Bacterial Taxa | Weaker | Stronger |

| Core Resistome | 23% of pan-resistome | 12% of pan-resistome |

This data demonstrates that FG ARGs represent a vast and diverse reservoir of resistance. Their stronger association with bacterial taxa suggests many may be intrinsic genes of environmental bacteria that have not yet mobilized into human pathogens, representing a latent reservoir of resistance [31]. Furthermore, the more uniform global distribution of FG ARGs implies different dispersal dynamics compared to acquired ARGs, which show strong geographical clustering, particularly high abundance in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), the Middle East & North Africa (MENA), and South Asia (SA) [31]. This latent reservoir underscores the importance of functional metagenomics in proactive surveillance.

Experimental Protocol: A Guideline for Functional Metagenomic Screening

Following a standardized protocol is essential for the reproducibility and reliability of functional metagenomic experiments. The guideline below, synthesized from best practices and applied studies, outlines the key steps for unbiased screening of antibiotic resistance genes from complex wastewater samples [32].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Functional Metagenomics

| Reagent/Material | Function | Critical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental Sample (e.g., WWTP Influent) | Source of microbial community DNA and novel ARGs | Collect aseptically; record parameters (pH, temp); process immediately or store at -80°C. |

| DNA Extraction Kit (e.g., for Metagenomics) | Isolate high-molecular-weight, pure DNA from complex samples | Must be effective for Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria; minimize bias. |

| Vector (e.g., Fosmid or Cosmid) | Clone large, random fragments of environmental DNA | Capable of carrying large inserts (30-40 kb); contain suitable promoters for expression in host. |

| Host Strain (e.g., Escherichia coli) | Propagate metagenomic library and express cloned genes | Must be highly transformable and susceptible to the antibiotics used for selection. |

| Selection Antibiotics | Phenotypically screen for resistance conferring clones | Use a range of antibiotics at clinically relevant concentrations; include positive and negative controls. |

Detailed Methodological Workflow

Sample Collection and Processing:

- Collect wastewater samples (e.g., raw influent, primary sludge, treated effluent) in sterile containers.

- Metadata Recording: Document sampling date, location, temperature, pH, and chemical oxygen demand (COD) if possible [30].

- Concentrate microbial biomass via filtration or centrifugation. Store pellets at -80°C until DNA extraction.

Metagenomic DNA Extraction:

- Use a kit or protocol designed to maximize DNA yield and purity from diverse bacterial communities while shearing DNA minimally.

- Assess DNA quality using spectrophotometry (e.g., Nanodrop) and fluorometry (e.g., Qubit). Verify high molecular weight via gel electrophoresis.

Metagenomic Library Construction:

- Partial Digestion: Use restriction enzymes that generate cohesive ends to create random, large-sized fragments (30-40 kb).

- Size Selection: Perform agarose gel electrophoresis to isolate and purify DNA fragments of the desired size to maximize cloning efficiency.

- Ligation and Packaging: Ligate size-selected DNA into a fosmid or cosmid vector. If using phage vectors, package the recombinant DNA into phage particles.

- Transformation/Transfection: Introduce the constructed library into a competent E. coli host strain.

Phenotypic Screening for Resistance:

- Plate the library members onto LB agar plates containing a sub-inhibitory concentration of a specific antibiotic (e.g., fluoroquinolones, beta-lactams, macrolides) [30].

- Incubation: Incubate plates at 37°C for 16-48 hours.

- Selection of Clones: Pick colonies that grow on antibiotic-containing plates for further analysis.

Sequence Analysis and Validation:

- Sequencing: Sequence the inserted DNA from resistant clones using Sanger or next-generation sequencing.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Compare obtained sequences to databases (e.g., ResFinderFG, PanRes) to identify known ARGs or novel candidates [31].

- Functional Confirmation: Re-clone the putative ARG into a clean vector and re-transform to confirm it confers the resistance phenotype.

Advanced Applications and Integrative Approaches

While functional metagenomics is powerful alone, its integration with other high-resolution techniques provides a more comprehensive view of resistome dynamics. Genome-resolved metagenomics, which involves reconstructing metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) from sequence data, can be used in tandem to identify the specific bacterial hosts carrying ARGs [30] [33]. This combination has revealed that anaerobic digestion decreases the abundance of human-associated ARG carriers in WWTPs, though many ARGs remain transcriptionally active [30]. Furthermore, this approach has successfully identified "microbial dark matter"—yet-uncultivated microorganisms—acting as reservoirs for clinically relevant ARGs in hospital and municipal wastewater [33].

Another powerful integration is with metatranscriptomics, which sequences the total RNA of a community. This allows researchers to determine which ARGs are not just present but are also highly expressed and likely functionally relevant under specific conditions. For instance, in WWTPs, genes like adeF and vancomycin homologues have been found to remain highly expressed across different types of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, highlighting their potential clinical significance [30]. This multi-omic approach provides a foundational framework for integrated AMR monitoring, moving beyond mere presence/absence to understand expression, host-association, and the potential for horizontal gene transfer via mobile genetic elements like plasmids [34].

Functional metagenomics stands as an indispensable tool in the ongoing battle against antimicrobial resistance. By providing an unbiased, phenotype-driven approach to discover novel ARGs, it illuminates the vast and latent resistome present in wastewater environments that sequence-based methods would overlook. The integration of this technique with genome-resolved metagenomics and metatranscriptomics offers an unparalleled, high-resolution view of the carriers, expression, and dissemination potential of resistance determinants. As the global AMR crisis intensifies, adopting and refining these advanced surveillance methodologies is paramount for informing targeted public health interventions, understanding resistance dynamics within the One Health framework, and safeguarding the efficacy of existing antibiotics for future generations.

Antibiotic resistance poses a critical threat to global public health, with projections suggesting antibiotic-resistant infections could cause over 10 million deaths annually by 2050 [35]. Wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) represent significant reservoirs where antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) accumulate and potentially disseminate back into the environment through treated effluent discharge [36] [3]. These environments contain diverse bacterial communities that maintain extensive collections of uncharacterized ARGs, constituting a vast and largely unexplored resistance reservoir [37].

The challenge in monitoring this reservoir lies in the limitations of conventional methods. Culture-based approaches fail to capture approximately 90% of bacterial species, while molecular methods like PCR and qPCR primarily detect known ARGs, missing novel genes with low sequence similarity to database references [38]. This gap is particularly problematic for environmental surveillance, where functionally novel ARGs may transfer from non-pathogenic to pathogenic bacteria [36]. Shotgun metagenomics enables cultivation-independent analysis but generates highly fragmented data, making ARG reconstruction difficult, especially for genes embedded in repetitive genetic contexts like integrons, transposons, and plasmids [37].

fARGene: Methodological Framework and Innovation

Core Algorithm and Workflow

fARGene represents a computational breakthrough specifically designed to address the challenge of identifying and reconstructing previously uncharacterized antibiotic resistance genes directly from fragmented metagenomic data [37]. The method employs optimized gene models that enable high-accuracy identification of novel resistance genes, even when their sequence similarity to known ARGs is low [37].

The methodology operates through three principal phases:

- Read Classification and Identification: Metagenomic reads are translated into amino acid sequences in all six reading frames. ARG-specific Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) then score and classify each fragment, with models optimized for sensitivity to divergent genes while maintaining specificity against evolutionarily related non-resistance genes [37].

- Targeted Assembly: Reads identified as potential ARG fragments, along with their paired-end mates, undergo quality assessment and are reconstructed into full-length sequences using paired-end assembly, circumventing the need for whole-metagenome assembly [37].

- Quality Assurance and Extraction: Reconstructed sequences undergo a second classification using models optimized for full-length genes. Open reading frames are predicted, and both nucleotide and amino acid sequences are extracted for downstream analysis [37].

Model Optimization and Threshold Determination

A critical innovation in fARGene is its systematic approach to model optimization. The method includes functionality to create ARG-specific models and determine optimal classification thresholds based on the trade-off between sensitivity and specificity [37]. Sensitivity is estimated through leave-one-out cross-validation where reference genes are consecutively excluded from model building, randomly fragmented, and then classified. Specificity is evaluated using a negative set of sequences from evolutionarily related genes that lack resistance functionality [37].

This optimization is particularly crucial for analyzing short metagenomic reads. For 100-nucleotide reads, fARGene achieves a sensitivity of 0.81-0.94 while maintaining specificity above 0.95 for most β-lactamase models, though sensitivity for B3 β-lactamases is approximately 0.70 to achieve specificity above 0.90 [37].

Figure 1: The fARGene analytical workflow, illustrating the three-stage process from metagenomic read input to reconstructed ARG sequences.

Performance Benchmarking and Experimental Validation

Case Study: β-lactamase Reconstruction

To demonstrate fARGene's practical utility, researchers conducted a large-scale case study focusing on β-lactamase genes across five metagenomic datasets comprising more than five billion DNA reads [37]. Six specialized models were developed covering the four β-lactamase Ambler classes (A, B, C, and D), with class B divided into two models to account for parallel evolution and class D separated into two models to capture their substantial diversity [37].

The results were striking: fARGene reconstructed 221 β-lactamase genes, of which 58 (26.2%) represented previously unreported sequences with less than 70% sequence similarity to any gene in NCBI GenBank [37]. This demonstrates the method's unique capability to expand the catalog of known resistance genes beyond what is achievable through homology-based searches alone.

Experimental validation confirmed the functional relevance of these discoveries. When 38 novel ARGs reconstructed by fARGene were expressed in Escherichia coli, 81% conferred a measurable resistance phenotype [37]. This high validation rate confirms that fARGene identifies not just homologous sequences but functional resistance determinants.

Comparative Performance Analysis

fARGene demonstrates superior performance compared to existing methods for ARG detection in metagenomic data [37]. In benchmark analyses, fARGene showed significantly higher sensitivity for detecting novel β-lactamases compared to deepARG and four other methods [37]. Unlike deepARG, which can identify novel ARG fragments but lacks assembly capabilities, fARGene provides the crucial functionality of reconstructing complete gene sequences necessary for functional characterization and evolutionary studies [37].

Table 1: Performance Metrics of fARGene for β-lactamase Identification

| Metric | Class A | Class B | Class C | Class D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity (full-length genes) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Specificity (full-length genes) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Sensitivity (100nt reads) | 0.94 | 0.70-0.81 | 0.85 | 0.81 |

| Specificity (100nt reads) | >0.95 | >0.90 | >0.95 | >0.95 |

| Experimentally validated novel genes | 81% functional in E. coli |

Implementation in Wastewater Resistome Surveillance

Integration with Wastewater Monitoring Frameworks

Wastewater treatment plants worldwide have been identified as critical hotspots for antibiotic resistance dissemination [39] [35] [36]. Quantitative studies have consistently detected high abundances of specific ARGs in wastewater, with intI1, sul1, blaTEM, and tetQ among the most abundant genes across diverse geographical locations [35]. These genes persist despite treatment processes, with studies showing significant but incomplete reduction of ARG concentrations (0.62->4.05 log reduction values) through WWTPs [35].

fARGene enhances standard wastewater monitoring by enabling discovery of previously undetectable resistance determinants. While conventional qPCR and metagenomic approaches typically monitor known targets, fARGene's ability to reconstruct divergent ARGs provides a more comprehensive assessment of the resistome in these critical environments [37]. This is particularly valuable for tracking emerging resistance threats before they become established in clinical settings.

Global Resistome Context

Recent global analysis of WWTP resistomes reveals a core set of 20 ARGs present in all treatment plants across six continents, with ARG composition varying geographically but maintaining consistent functional profiles [3]. The most abundant resistance mechanisms in WWTPs include antibiotic inactivation (55.7%), target alteration (25.9%), and efflux pumps (15.8%) [3]. Genes conferring resistance to beta-lactams (46.5%), glycopeptides (24.5%), and tetracyclines (16.2%) dominate these environments [3].

fARGene provides the methodological framework to move beyond cataloging known ARGs toward discovering the full diversity of resistance determinants in these complex microbial communities. Its application to wastewater samples could substantially expand our understanding of the mobile resistome and its potential for transmission to pathogens.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources for fARGene Implementation

| Resource Type | Specific Tool/Database | Application in Analysis |

|---|---|---|