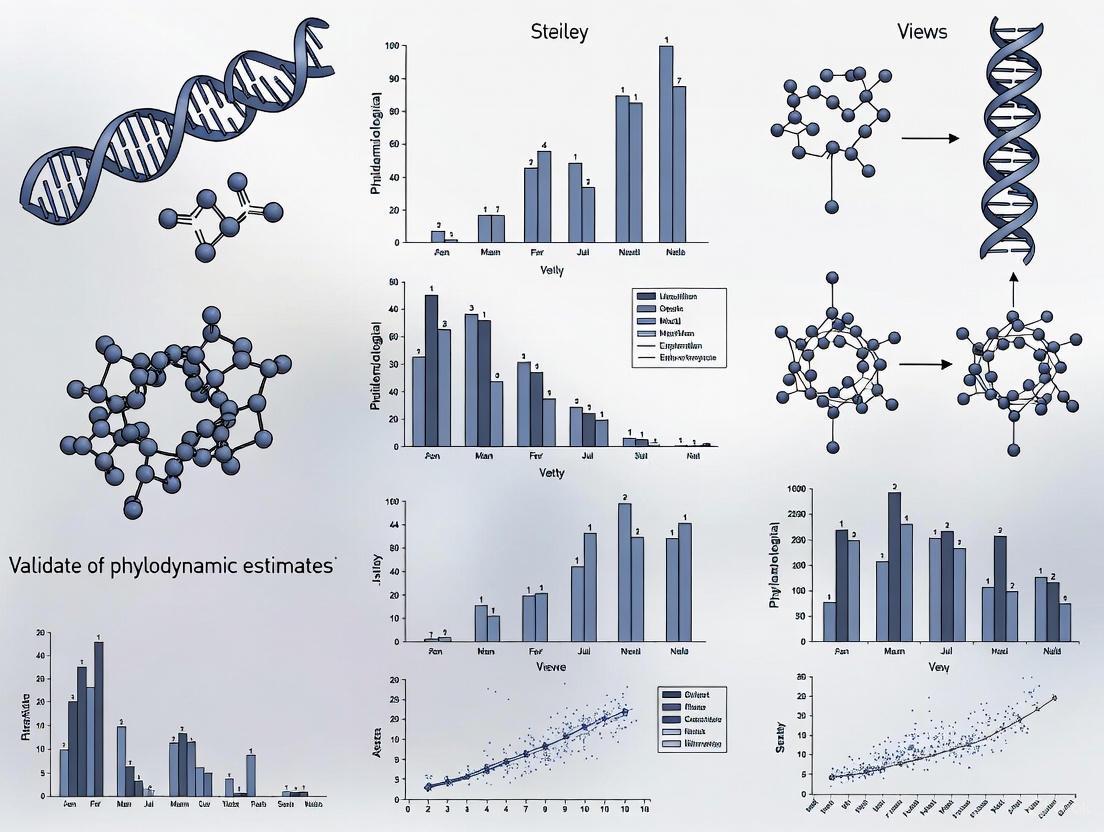

Validating Phylodynamic Estimates with Epidemiological Data: Methods, Challenges, and Best Practices for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive framework for validating phylodynamic inferences against epidemiological data, addressing critical needs for researchers and drug development professionals.

Validating Phylodynamic Estimates with Epidemiological Data: Methods, Challenges, and Best Practices for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for validating phylodynamic inferences against epidemiological data, addressing critical needs for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles connecting genomic evolution to transmission dynamics and examines cutting-edge methodological approaches from scalable Bayesian inference to deep learning. The content systematically addresses troubleshooting for model misspecification and computational bottlenecks while presenting rigorous validation techniques and comparative analyses of prevailing software tools. By synthesizing insights from recent tuberculosis, HIV, and SARS-CoV-2 studies, this guide establishes best practices for ensuring phylodynamic estimates robustly inform public health interventions and therapeutic development.

Bridging Genomic Evolution and Transmission Dynamics: Core Principles for Validation

{: .no_toc}

Phylodynamic models provide a powerful quantitative framework that integrates genetic sequence data with epidemiological and evolutionary theories to reconstruct infectious disease transmission dynamics. The core mechanistic principle underpinning these approaches is that epidemiological processes leave distinctive signatures in pathogen genomes, which can be decoded through phylogenetic analysis and population genetic models [1]. This guide objectively compares the major phylodynamic modeling frameworks, evaluates their performance against epidemiological data, and details the experimental protocols essential for validation research.

Key Advances in Phylodynamic Inference

The field has evolved significantly from early coalescent models to increasingly sophisticated frameworks that address complex epidemiological scenarios:

| Modeling Framework | Core Mechanism | Epidemiological Parameters Estimated | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coalescent Models (e.g., Skyline) [2] [1] | Models the time to common ancestry of sampled sequences within a changing effective population size ((N_e(t))). | Effective population size through time ((Ne(t))), growth rates, basic reproduction number ((R0)) [1]. | Assumes negligible within-host diversity; biased when transmission bottlenecks are imperfect [2]. |

| Birth-Death (BD) Models [3] [1] | Models transmission (birth) and recovery/removal (death) as stochastic processes; directly reflects epidemic dynamics. | Effective reproduction number ((R_e(t))), prevalence of infection, birth (transmission) and death (removal) rates [3]. | Computationally intensive for large datasets; requires careful model specification to avoid bias [3] [4]. |

| Multi-Scale Coalescent Models (MSCoM) [2] | Separately models within-host population dynamics and between-host transmission process. | Number of infected hosts, within-host effective population size ((N)), transmission bottleneck size [2]. | Increased model complexity; requires sophisticated statistical inference. |

| Structured Models (Phylogeography) [5] [6] | Incorporates discrete or continuous traits (e.g., location, host type) into the evolutionary model to trace dispersal. | Migration rates between locations, drivers of spatial spread, diffusion rates [5]. | Sensitive to sampling bias across populations; high computational cost [7]. |

Comparative Performance in Epidemiological Validation

Quantitative comparisons reveal that model performance and accuracy are highly dependent on the epidemiological context and data quality.

Table 1: Performance comparison of phylodynamic models when validated against reported case data.

| Pathogen & Context | Model Applied | Key Performance Finding | Reported Consistency with Epidemiological Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-1 Outbreak [2] | Conventional Coalescent (CoM12) | Substantial upward bias in estimated number of infected hosts | Low |

| HIV-1 Outbreak [2] | Multi-Scale Coalescent (MSCoM) | Greater consistency with reported diagnosis trends | High |

| Ebola Virus Outbreak [2] | Both Conventional & Multi-Scale Coalescent | Little influence of within-host diversity on estimates | High for both models |

| SARS-CoV-2 (Diamond Princess) [3] | Birth-Death (Timtam package) | Recovered estimates consistent with previous analyses | High |

| Poliomyelitis (Tajikistan) [3] | Birth-Death (Timtam package) | Estimates consistent with independent analysis; provided novel prevalence estimates | High |

| Non-Avian Dinosaurs [8] | Various Mechanistic Models | Conclusions on diversity decline highly sensitive to model assumptions and phylogeny | Inconclusive |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Validating phylodynamic estimates requires rigorous methodologies. Below are detailed protocols for key experiments cited in this guide.

Protocol: Multi-Scale Model Inference for HIV-1 and EBOV

This protocol is adapted from the study that developed the Multi-Scale Coalescent Model (MSCoM) to address violations of standard phylodynamic assumptions [2].

- Objective: To estimate epidemiological parameters (e.g., number of infected hosts, reproduction number) while accounting for within-host genetic diversity and imperfect transmission bottlenecks.

- Input Data Requirements:

- Genetic Sequences: A time-stamped multiple sequence alignment (MSA) of pathogen genomes (e.g., HIV-1 p17 or EBOV gene sequences).

- Genealogy: A bifurcating genealogy ( G ) reconstructed from the MSA, with known sampling times ( (t1, ..., tn) ) and internal node times ( (\tilde{t}1, ..., \tilde{t}{n-1}) ).

- Epidemiological Model Specification:

- Model the number of infected individuals ( y(t) ) using a birth-death demographic process with time-dependent birth rate ( f(t) ) (population-level transmission rate) and constant per-capita death rate ( \gamma ) (recovery/removal rate).

- Use a flexible spline model for ( \log(f(t)) ) (the "skyspline") to approximate non-linear epidemic dynamics.

- Within-Host Model: Model evolution within hosts as a neutral coalescent process with a constant effective population size ( N ).

- Inference Procedure:

- Use a likelihood-based approach (e.g., maximum likelihood or Bayesian inference) to jointly estimate the parameters ( \theta ), which include the initial number of infected ( y(0) ), the death rate ( \gamma ), spline parameters for ( f(t) ), and the within-host effective population size ( N ).

- Calculate the effective reproduction number as a derived parameter: ( R(t) = f(t) / (\gamma y(t)) ).

- Validation: Compare the estimated number of infected hosts ( y(t) ) and ( R(t) ) to officially reported case numbers and diagnosis trends through time.

Protocol: Joint Inference from Genomic and Time Series Data

This protocol is based on the method implemented in the BEAST2 package Timtam, which combines phylogenetic information with time series of case counts [3].

- Objective: To estimate the historical prevalence of infection and the effective reproduction number by combining unscheduled genomic data and scheduled case count data.

- Input Data Requirements:

- ( D{MSA} ): A multiple sequence alignment of time-stamped pathogen genomes.

- ( D{cases} ): A time series of confirmed case counts (which may include unsequenced infections).

- Model Parameters:

- ( H ): The number of hidden lineages (infected, unsequenced individuals) through time.

- ( T ): The time-calibrated reconstructed phylogeny from ( D{MSA} ).

- ( \theta{evo} ): Evolutionary model parameters (e.g., molecular clock rate, substitution model).

- ( \theta_{epi} ): Epidemiological model parameters (e.g., transmission rate, sampling rate).

- Likelihood Approximation:

- The method uses an efficient approximation to evaluate the joint posterior distribution: ( P(T, H, \theta{evo}, \theta{epi} | D{MSA}, D{cases}) ).

- This approximation properly weights the contributions of each dataset, avoiding the assumption of conditional independence.

- Output:

- Joint estimates of the effective reproduction number ( Re(t) ) and the prevalence of infection ( kt + H_t ) (sum of sampled and hidden lineages) through time.

- Validation: In a simulation study, this method was shown to be well-calibrated, with approximately 95% of the 95% highest posterior density intervals containing the true parameter value [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Successful phylodynamic analysis relies on a suite of specialized software and reagents.

Table 2: Key research reagents and software solutions for phylodynamic inference.

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Application in Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| BEAST2 [3] [1] | Software Package | Bayesian evolutionary analysis sampling trees; implements a wide range of phylodynamic models. | Core platform for model inference; used in birth-death and coalescent analyses. |

| Timtam [3] | BEAST2 Package | Efficient approximation for joint analysis of genomic data and epidemiological time series. | Enables estimation of historical prevalence from sequences and case counts. |

| Multi-Scale Coalescent (MSCoM) [2] | Statistical Model / Method | Inference framework accounting for within-host evolution and between-host transmission. | Correcting bias in estimated number of infected hosts (e.g., in HIV-1 analysis). |

| Generalized Linear Model (GLM) [5] | Statistical Model | Formal statistical testing of predictors for migration rates in phylogeography. | Identifying significant drivers of viral spread (e.g., trade, population size). |

| Structured Coalescent Models [4] | Statistical Model | Infers migration rates between populations while adjusting for demographic dynamics. | Estimating robust migration rates in structured epidemics (e.g., HIV in San Diego). |

Operational Workflows and Logical Frameworks

The following diagrams map the core logical relationships and operational workflows in phylodynamic model specification and validation.

Phylodynamic Model Inference Logic

Model Validation Workflow

The mechanistic basis of phylodynamic models rests on formal relationships between epidemiological processes and pathogen genetic evolution. The choice of model—coalescent, birth-death, or multi-scale—is not merely technical but fundamentally shapes the epidemiological conclusions drawn from genetic data. Performance varies significantly: multi-scale models can correct critical biases in conventional approaches for pathogens like HIV-1, while simpler models may suffice for others like EBOV. Robust validation requires rigorous simulation studies and comparison with traditional surveillance data, as inconsistencies often reveal model limitations or underlying biological complexities. Future progress hinges on developing more efficient inference algorithms, comprehensive models of sampling bias, and the integration of diverse data sources to improve the accuracy of phylodynamic estimates for public health decision-making.

The integration of pathogen genomic sequencing into public health has revolutionized infectious disease epidemiology. Modern investigations into disease outbreaks now almost routinely combine genome sequence data with traditional epidemiological data to reconstruct nearly every aspect of transmission dynamics [9]. This synergy enables researchers to move beyond historical reconstructions and formally test epidemiological hypotheses about the origins, transmission, and evolution of infectious diseases [10]. By applying phylodynamic and phylogeographic models to pathogen genomes, key epidemiological parameters such as detailed transmission trees, epidemic growth rates, and spatial migration patterns can be inferred, providing powerful insights for targeted public health interventions. This guide compares the methodologies, applications, and validation of these inferable parameters within the broader context of phylodynamic research.

Transmission Trees: Inferring Who-Infected-Whom

Core Concepts and Definitions

A transmission tree depicts the history of transmission events in an outbreak, where nodes represent infected hosts and directed edges represent transmission events between them [11]. Reconstructing these "who-infected-whom" relationships is fundamental to understanding transmission dynamics and appropriately targeting control measures [11]. It is crucial to distinguish transmission trees from phylogenetic trees, as internal nodes in phylogenetic trees represent hypothetical common ancestors rather than transmission events, and the timing of nodes corresponds to within-host diversification events which often precede transmission [11].

Methodological Approaches for Inference

Methods for reconstructing transmission trees from genomic and epidemiological data fall into three main families [11]:

- Non-Phylogenetic Family (NPF): These methods use pairwise genetic distances between pathogen sequences without reconstructing a phylogenetic tree. Examples include

outbreaker2[11]. - Sequential Phylogenetic Family (SeqPF): These methods involve a two-step approach where a phylogenetic tree is first reconstructed, and then used as a source of information to infer the transmission tree. Examples include

TiTUS[11]. - Simultaneous Phylogenetic Family (SimPF): These methods jointly infer the phylogenetic and transmission trees simultaneously. An example is

BORIS(Bayesian Outbreak Reconstruction Inference and Simulation) [11].

Table 1: Comparison of Transmission Tree Reconstruction Methods

| Method Family | Core Principle | Example Tools | Key Data Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Phylogenetic (NPF) | Uses pairwise genetic distances | outbreaker2 |

Sampling times, genetic distances, contact data (optional) |

| Sequential Phylogenetic (SeqPF) | Phylogenetic tree reconstructed first, then used for transmission inference | TiTUS |

Sampling times, pre-existing phylogenetic tree, contact data (for TiTUS) |

| Simultaneous Phylogenetic (SimPF) | Phylogenetic and transmission trees inferred jointly | BORIS |

Sampling times, removal times, intrinsic host characteristics |

Experimental Protocol for Transmission Tree Inference

A standard workflow for inferring a transmission tree using a Bayesian phylogenetic framework involves:

- Data Preparation: Collect and curate pathogen genome sequences from infected hosts. Compile an epidemiological line list containing at least sampling times for each host, and ideally, additional data such as symptom onset, location, and possible exposures [9].

- Multiple Sequence Alignment: Align the genome sequences using tools like MAFFT or Clustal Omega to identify homologous positions.

- Phylogenetic Model Selection: Determine the best-fit nucleotide substitution model (e.g., GTR, HKY) using software like ModelTest-NG.

- Molecular Clock Calibration: Use sampling dates to calibrate a molecular clock model (e.g., strict or relaxed clock) to estimate the evolutionary rate and place the phylogeny in real time.

- Tree Inference (for SeqPF/SimPF): For Sequential methods, reconstruct a time-scaled phylogenetic tree using software like BEAST, MrBayes, or RAxML. For Simultaneous methods, this is integrated with the next step.

- Transmission Model Parameterization: Define a transmission model that specifies the probability of transmission between hosts based on epidemiological parameters (e.g., generation time distribution) and, if available, contact data [11].

- Joint Inference (for SimPF): Using a tool like

BORIS, perform a joint inference of the phylogenetic and transmission trees within a single statistical framework, typically via Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling. - Analysis and Visualization: Analyze the posterior distribution of transmission trees to identify robustly supported transmission links and summarize key statistics (e.g., reproduction number per case, super-spreading events). Visualize the maximum clade credibility tree or a sample of posterior trees.

Figure 1: A generalized workflow for inferring transmission trees from genomic data, integrating phylogenetic and epidemiological inference.

Growth Rates: Estimating Epidemic Dynamics

Phylodynamic Inference of Population Size

Phylodynamics studies how pathogen population genetic diversity is shaped by the interaction of within-host immunological and between-host epidemiological dynamics [2]. A key parameter inferred in phylodynamic analyses is the effective number of infections ((Ne(t))) through time, which is derived from the pathogen genealogy and is related to the true number of infected hosts, (y(t)) [2]. According to one coalescent framework, (Ne(t) = \frac{y^2(t)}{2f(t)}), where (f(t)) is the population birth rate (incidence) [2].

Addressing the Challenge of Within-Host Diversity

A critical challenge in phylodynamics is that conventional models assume nodes in a time-scaled phylogeny correspond to transmission events. This assumption is violated when there is non-negligible within-host genetic diversity, causing internal nodes to pre-date transmission events (the pre-transmission interval) and leading to biased estimates [2]. To address this, multi-scale coalescent models (MSCoM) have been developed. These models account for within-host evolution as a neutral coalescent process and can accommodate imperfect transmission bottlenecks, providing more accurate estimates of the true number of infected hosts and reproduction numbers [2].

Experimental Protocol for Skyline Analysis

The Skyline Plot family of methods is commonly used to estimate changes in effective population size through time.

- Genealogy Estimation: Obtain a time-scaled phylogenetic tree of the pathogen sequences, for example, from a BEAST analysis.

- Coalescent Model Selection: Choose an appropriate coalescent model for the Skyline analysis (e.g., Bayesian Skyline, Skygrid). These are flexible models that do not assume a constant or smoothly changing population size.

- Grouping Intervals: Define the number of grouped intervals ("epochs") for the analysis. More intervals allow for more resolution but require more data.

- MCMC Sampling: Run an MCMC analysis to sample the posterior distribution of the effective population size within each interval, jointly with other phylogenetic parameters.

- Plotting and Interpretation: Generate the skyline plot, which displays the median estimate and credible intervals for (N_e(t)) through time. A sharp increase indicates exponential growth of the epidemic, while a decrease suggests successful control.

Table 2: Methods for Inferring Epidemic Growth from Genomes

| Method | Core Principle | Key Output | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coalescent-based (e.g., CoM12) | Infers effective population size ((N_e(t))) from the pattern of coalescence in a genealogy [2]. | Effective number of infections through time. | Computationally efficient; works with a single sample per host. | Assumes transmission tree ~ phylogeny; biased by within-host diversity [2]. |

| Birth-Death (BD) Models | Models the processes of transmission (birth) and removal/recovery (death) to explain the observed phylogeny. | Time-varying reproduction number (R(t)), incidence. | Directly estimates epidemiologically relevant parameters (R0). | Requires assumptions about the removal process. |

| Multi-Scale Coalescent (MSCoM) | Explicitly models within-host evolution as a separate coalescent process from between-host spread [2]. | Unbiased estimates of (y(t)) and (R(t)), within-host (N_e). | Accounts for within-host diversity; more robust. | More complex, computationally intensive. |

Migration Patterns: Reconstructing Spatial Spread

Phylogeographic Inference

Phylogeography places time-scaled phylogenies in a geographical context to reconstruct the dispersal history of viral lineages across a landscape [10]. This allows researchers to infer the routes and rates of spatial spread, identifying sources, sinks, and corridors of transmission. This approach has been used to trace the global spread of influenza A/H3N2 from East and Southeast Asia [9] and the invasion dynamics of West Nile virus across North America [10].

Formal Hypothesis Testing: Landscape Phylogeography

Moving beyond descriptive maps, landscape phylogeography provides a formal statistical framework to test the impact of environmental factors on dispersal patterns [10]. For example, one can test whether viral lineages tend to disperse faster or are attracted to/repelled by specific environmental conditions such as temperature, precipitation, or land cover type.

Experimental Protocol for Phylogeographic Analysis

The following protocol outlines the process for a Bayesian phylogeographic analysis:

- Data Annotation: Assign discrete location traits (e.g., country, state, district) or continuous spatial coordinates to each taxon in the phylogenetic tree.

- Spatial Model Selection: For discrete traits, select a model of discrete diffusion (e.g., symmetric vs. asymmetric rates). For continuous traits, select a diffusion process (e.g., Brownian Motion).

- Phylogeographic Inference: Using software like BEAST, perform a joint inference of the time-scaled phylogeny and the spatial diffusion process. This will reconstruct the likely location of each internal node.

- Visualization: Visualize the resulting "spread" tree using tools like SpreaD3 or cartography software, animating the spread through time and space.

- Statistical Testing (Landscape Phylogeography):

a. Extract a posterior set of spatially-annotated trees.

b. For a given environmental raster (e.g., temperature), extract the environmental value at the location of each node in each tree.

c. Compute a test statistic (e.g.,

E, the mean environmental value across nodes). d. Compare the posterior distribution ofEagainst a null distribution generated by simulating stochastic diffusion histories along the same tree topologies. A significant difference indicates the environmental factor influences dispersal [10].

Figure 2: A workflow for testing the impact of environmental factors on viral dispersal using landscape phylogeography.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Phylodynamic Studies

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Application in Parameter Inference |

|---|---|---|---|

| BEAST / BEAST2 | Software Package | Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees; the core platform for phylodynamics. | Infers time-scaled phylogenies, population sizes (Skyline plots), and phylogeography. |

| Nextstrain | Open-source Platform | Real-time tracking of pathogen evolution; integrates bioinformatic workflows and visualization [12]. | Provides standardized pipelines for generating transmission trees and spatial spread narratives. |

| outbreaker2 | R Package | Reconstructs transmission trees from outbreak data (case reports, contacts, genomes) [11]. | Infers who-infected-whom in an outbreak (Non-Phylogenetic Family). |

| ANNOVAR | Software Tool | Functional annotation of genetic variants from sequencing data [13]. | Identifies mutations of epidemiological interest (e.g., concerning variants, antimicrobial resistance). |

| Illumina Sequencing | Technology | Second-generation sequencing; high-throughput, short reads [13]. | Workhorse for generating whole-genome or whole-exome sequence data for phylogenetic analysis. |

| Oxford Nanopore | Technology | Third-generation sequencing; long reads, real-time, portable [13]. | Enables rapid genomic surveillance in the field for near real-time phylodynamic analysis. |

| The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) | Data Repository | Repository of cancer genomics and clinical data [13]. | (Analogous) Source of integrated genomic and epidemiological data for analysis. |

Pathogen genomes are a rich source of epidemiological information, enabling the inference of transmission trees, epidemic growth rates, and migration patterns. Each parameter requires specific methodological approaches—from non-phylogenetic to multi-scale coalescent models—and faces unique challenges, particularly in reconciling the differences between phylogenetic and transmission timescales. The field is moving decisively from descriptive historical reconstructions toward formal, statistically rigorous hypothesis testing about the factors driving epidemic spread. As sequencing technologies continue to become more accessible and analytical frameworks more sophisticated, the synergy of genomic and epidemiological data will play an increasingly vital role in guiding public health interventions and controlling infectious disease outbreaks.

The Role of Genomic Data Quality and Sampling Strategies in Validation Outcomes

Phylodynamics, defined as the "melding of immunodynamics, epidemiology, and evolutionary biology," has emerged as a cornerstone technique for understanding infectious disease transmission dynamics by combining phylogenetic analysis with epidemiological models [1]. This approach fundamentally relies on the premise that epidemiological processes occur on a similar timescale to observable genomic change, leaving distinct signatures in pathogen genomes that can be decoded to infer transmission patterns, population sizes, and spatial spread [1]. The validation of phylodynamic estimates against standard epidemiological data represents a critical challenge in the field, with genomic data quality and sampling strategies serving as pivotal determinants of analytical reliability.

The foundational assumption of phylodynamics is that the branching times in a phylogenetic tree reflect underlying transmission dynamics, enabling researchers to estimate key parameters such as the effective reproduction number (Rt) and growth rates (rt) from genetic sequence data [1] [14]. These genomic-derived estimates are increasingly used to supplement or validate traditional surveillance data, particularly when case and death data are compromised by disparities in diagnostic surveillance and notification systems between regions [14]. However, the accuracy of these phylodynamic inferences is heavily contingent on both the quality of genomic data and the strategic approach to sampling, creating a complex validation landscape that researchers must navigate to produce meaningful public health insights.

Sampling Strategy Implementation: Methodological Approaches

The selection of viral sequences for phylodynamic analysis can introduce significant biases that detract from the value of these rich datasets, raising fundamental questions about how sequences should be chosen for validation-focused research [14]. Different sampling strategies impose distinct trade-offs between computational feasibility, representativeness, and statistical power, making the choice of approach a critical determinant of validation outcomes.

Core Sampling Frameworks

Proportional Sampling: This approach selects sequences in proportion to case incidence across time periods, ensuring that sampling intensity matches the epidemic curve. In practice, this method resulted in N=54 sequences for Hong Kong and N=168 for Amazonas in SARS-CoV-2 studies [14]. This strategy theoretically enhances representativeness but may oversample dominant lineages during peak transmission periods.

Uniform Sampling: This method distributes sampling evenly across time points regardless of case incidence, yielding N=79 sequences for Hong Kong and N=150 for Amazonas in comparative studies [14]. By ensuring temporal coverage, this approach better captures lineage diversity throughout an epidemic but may underrepresent periods of intense transmission.

Reciprocal-Proportional Sampling: This strategy intentionally oversamples during low-incidence periods to enhance statistical power for detecting transitions and emerging variants. Implementation resulted in N=84 sequences for Hong Kong and N=67 for Amazonas [14]. This approach is particularly valuable for capturing rare transmission events but may distort overall incidence patterns.

Unsampled Datasets: Utilizing all available sequences without strategic selection (N=117 for Hong Kong; N=196 for Amazonas) seems intuitively optimal but introduces significant computational challenges and potential overrepresentation of well-sampled periods [14].

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Sampling Strategies for Parameter Estimation

| Sampling Strategy | Temporal Signal Strength | Computational Efficiency | Rt Estimation Bias | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportional | Moderate | High | Low to Moderate | Endemic periods; incidence-based validation |

| Uniform | Strong | Moderate | Low | Epidemic transitions; variant emergence |

| Reciprocal-Proportional | Variable | Moderate to High | Moderate | Rare variant detection; elimination verification |

| Unsampled | Strongest | Lowest | Highest | Small outbreaks; maximal data availability |

Adaptive Validation Sampling

Beyond these core frameworks, adaptive validation sampling represents a methodological innovation that determines when sufficient validation data have been collected to yield a bias-adjusted effect estimate with a prespecified level of precision [15]. This approach monitors validation data as they accrue until specific stopping criteria are met, allowing researchers to optimize resource allocation while ensuring statistical rigor. In practical application, this method has been used to address exposure misclassification in studies of transmasculine/transfeminine youth and self-harm, with stopping criteria based on the precision of the conventional estimate and allowing for wider confidence intervals that would still be substantively meaningful [15].

Quantitative Impact of Sampling on Parameter Estimation

The influence of sampling strategies on phylodynamic inference is not uniform across parameters, with some estimates demonstrating robustness to sampling variation while others exhibit significant sensitivity. Understanding these differential effects is crucial for designing validation studies that produce reliable epidemiological insights.

Parameter-Specific Sensitivity Analyses

Research comparing sampling schemes for SARS-CoV-2 genomic analysis has revealed that the time-varying effective reproduction number (Rt) and growth rate (rt) are particularly sensitive to changes in sampling strategy [14]. Analysis of sequences from Hong Kong and Amazonas demonstrated that unsampled datasets resulted in the most biased Rt and rt estimates, while uniform sampling generally produced the most stable and reliable estimates for these parameters [14]. This sensitivity stems from the direct relationship between sampling distribution and the inferred timing of transmission events in birth-death models.

In contrast, the basic reproduction number (R0) and the date of origin (time to most recent common ancestor, TMRCA) demonstrate relative robustness to variations in sampling strategy [14]. For instance, molecular clock dating of Hong Kong SARS-CoV-2 datasets indicated that the estimated TMRCA was around December 2020 regardless of sampling scheme, a finding consistent with the known epidemiology of the pandemic in that region [14]. Similarly, estimates of R0 remained stable across sampling approaches, suggesting that this foundational parameter can be reliably inferred from genomic data even when sampling is suboptimal.

Table 2: Parameter Sensitivity to Sampling Strategies in SARS-CoV-2 Studies

| Epidemiological Parameter | Sensitivity to Sampling | Most Robust Strategy | Performance Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time-varying Reproduction Number (Rt) | High | Uniform sampling | Mean absolute error relative to case data |

| Growth Rate (rt) | High | Uniform sampling | Correlation with epidemiological estimates |

| Basic Reproduction Number (R0) | Low | All strategies | Relative standard deviation across methods |

| Date of Origin (TMRCA) | Low | All strategies | Range of estimates across sampling schemes |

| Substitution Rate | Low to Moderate | Uniform sampling | Bayesian credible interval width |

Quantifying Data Source Contributions

Recent methodological innovations enable researchers to quantify the relative contributions of sequence data versus sampling dates to phylodynamic inference. The Wasserstein metric framework isolates these effects by comparing posterior distributions derived from complete data, date-only data, sequence-only data, and marginal priors [16]. This approach reveals that sampling times often drive epidemiological inference under birth-death models, particularly for parameters like Rt [16]. In a comprehensive analysis of 600 simulated outbreaks, most data sets (372/600) were classified as date-driven, underscoring the critical importance of temporal sampling distribution in phylodynamic validation [16].

Fundamental Data Quality Challenges in Phylodynamic Inference

Beyond strategic sampling considerations, several fundamental data quality issues routinely complicate the validation of phylodynamic estimates against epidemiological data. These challenges represent persistent sources of bias and uncertainty that researchers must address through methodological refinements and careful study design.

Preferential Sampling Bias

Preferential sampling occurs when sampling times probabilistically depend on effective population size, creating a systematic relationship between sampling intensity and underlying epidemic dynamics [17]. In practice, this manifests when infectious disease samples are collected more frequently during high-incidence periods and less frequently during low-incidence periods, violating the assumption of most phylodynamic methods that sampling times are either fixed or follow a distribution independent of population size [17].

Through simulation studies, researchers have demonstrated that ignoring preferential sampling can significantly bias effective population size estimation, with the magnitude and direction of bias depending on local properties of the effective population size trajectory [17]. To address this challenge, innovative models have been developed that explicitly account for preferential sampling by modeling sampling times as an inhomogeneous Poisson process dependent on effective population size [17]. Implementation of these sampling-aware models not only reduces bias but also improves estimation precision, particularly for pathogens with strong seasonal dynamics like influenza [17].

Temporal Signal Decay

The strength of the temporal signal in genomic data, measured by the correlation between genetic divergence and sampling dates, varies substantially across outbreaks and significantly impacts parameter estimation precision [14]. Analyses of SARS-CoV-2 sequences from Hong Kong and Amazonas revealed striking differences in temporal signal strength, with Hong Kong datasets demonstrating correlation coefficients (R²) between 0.36 and 0.52 compared to just 0.13-0.20 for Amazonas datasets [14]. This discrepancy was attributed to Hong Kong's wider sampling interval (106 days versus 69 days for Amazonas), highlighting how sampling duration influences fundamental data quality for phylodynamic inference [14].

Computational Trade-offs

The unprecedented scale of modern genomic sequencing efforts—exemplified by over 11.9 million SARS-CoV-2 sequences available in GISAID—creates significant computational challenges for phylodynamic analysis [14]. Popular Bayesian approaches often converge slowly on large datasets, frequently necessitating sub-sampling that introduces additional methodological choices and potential biases [14]. This creates an inherent tension between data comprehensiveness and analytical tractability, forcing researchers to balance statistical power against computational feasibility when designing validation studies.

Experimental Protocols for Sampling Strategy Evaluation

To systematically evaluate the impact of sampling strategies on phylodynamic inference, researchers have developed standardized experimental protocols that enable direct comparison across approaches and parameters.

Sampling Scheme Implementation Protocol

Case Data Collection: Compile complete epidemiological data including case counts, sampling dates, and geographical information for the population and time period of interest [14].

Sequence Selection: Apply each sampling strategy (proportional, uniform, reciprocal-proportional) to select subsets from the full sequence dataset, ensuring that strategy-specific sample sizes are recorded for comparative power analyses [14].

Temporal Signal Assessment: Perform root-to-tip regression for each sampling scheme to calculate the correlation (R²) between genetic divergence and sampling dates, quantifying the strength of the temporal signal [14].

Phylodynamic Inference: Implement standardized birth-death or coalescent models (e.g., in BEAST2) using identical priors and computational settings across all sampling schemes to estimate key parameters including Rt, R0, TMRCA, and substitution rates [14].

Benchmark Comparison: Compare genomic-derived parameter estimates against those obtained from traditional surveillance data, calculating performance metrics including bias, precision, and coverage probability [14].

Wasserstein Metric Analysis Protocol

Data Treatment: Conduct four separate analyses for each dataset: complete data (sequences + dates), dates only (integrating over tree topology), sequences only (estimating sampling dates), and neither (marginal prior) [16].

Posterior Distribution Calculation: Estimate posterior distributions for parameters of interest (e.g., R0) under each data treatment using consistent MCMC settings and convergence diagnostics [16].

Distance Quantification: Calculate the Wasserstein distance between posterior distributions under reduced data treatments and the complete data posterior, using the formula: [ WD = \int0^1 |FD^{-1}(u) - FF^{-1}(u)| du ] where (FD) and (FF) are cumulative distribution functions for the parameter under date-only and complete data, respectively [16].

Classification: Identify the driving data source (dates or sequences) as the one with the smallest Wasserstein distance to the complete data posterior, with the classification boundary defined by (min(WD, WS)) [16].

Research Reagent Solutions for Phylodynamic Validation

Successful implementation of phylodynamic validation studies requires specialized analytical tools and resources. The following table catalogues essential research reagents with demonstrated utility in assessing and improving the reliability of genomic epidemiology.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Phylodynamic Validation Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Primary Function | Application in Validation | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| BEAST2 | Bayesian evolutionary analysis | Estimation of evolutionary parameters and demographic history | Requires careful prior specification and MCMC convergence assessment [14] |

| phybreak | Transmission tree inference | Determination of SNP cut-offs for transmission clustering | Assumes same time-to-detection for observed cases [18] |

| Wasserstein Metric | Distance measurement between distributions | Quantification of date vs. sequence data contributions | Sensitive to posterior distribution shape; requires subsampling validation [16] |

| Adaptive Validation Sampling | Precision-based sample size determination | Optimization of validation subsample size | Requires prespecified stopping criteria based on substantive meaningfulness [15] |

| Structured Coalescent Models | Phylogeographic inference | Reconstruction of spatial transmission routes | Performance depends on sampling uniformity across locations [19] |

| Birth-Death Sampling Models | Epidemiological parameter estimation | Inference of reproduction numbers from genomic data | Sensitive to preferential sampling; requires sampling-aware extensions [17] |

The validation of phylodynamic estimates against epidemiological data remains a complex endeavor fundamentally shaped by genomic data quality and sampling strategies. Based on current evidence, uniform sampling emerges as the most robust approach for parameters sensitive to temporal distribution, such as Rt and growth rates, while multiple strategies perform adequately for stable parameters like R0 and TMRCA [14]. The development of methods to quantify data source contributions, particularly the Wasserstein metric framework, represents a significant advance in diagnostic assessment of phylodynamic analyses [16].

Future methodological development should prioritize sampling-aware models that explicitly account for preferential sampling [17], optimized sub-sampling strategies for massive genomic datasets [14], and standardized validation protocols that enable cross-study comparability. Additionally, greater attention to the computational trade-offs inherent in phylodynamic analysis will be essential as genomic surveillance continues to expand globally. By addressing these fundamental challenges at the intersection of data quality and sampling methodology, researchers can enhance the reliability and public health utility of phylodynamic approaches to infectious disease surveillance.

Phylodynamics has emerged as a pivotal discipline at the intersection of pathogen genomics and epidemiology, enabling researchers to infer transmission dynamics, population history, and evolutionary parameters from genetic sequence data. The complete inference pipeline—from raw sequence alignment to the reconstruction of transmission networks—represents a complex workflow with multiple methodological choices that significantly impact results. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of tools and methods across this pipeline, framed within the critical context of validating phylodynamic estimates with epidemiological data. As technological advancements make pathogen whole-genome sequencing increasingly accessible, understanding the strengths, limitations, and appropriate applications of each analytical component becomes essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working to combat infectious diseases.

Sequence Alignment and Pre-processing

Alignment Tool Selection

The initial step in the phylodynamic inference pipeline involves aligning raw sequencing reads to a reference genome, a process that fundamentally shapes all downstream analyses. Recent benchmarking studies have evaluated platform-agnostic alignment tools on datasets from both nanopore and single-molecule real-time sequencing platforms, revealing significant differences in performance characteristics [20].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Long-Read Alignment Tools

| Tool | Computational Efficiency | Platform Compatibility | Strength | Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimap2 | Lightweight, fast | Nanopore, PacBio | Ideal for large-scale studies | Varies in unaligned read management |

| Winnowmap2 | Lightweight | Nanopore, PacBio | Effective for repetitive regions | Different genomic view from Minimap2 |

| NGMLR | High resource demand, slow | Nanopore, PacBio | Consistent alignment production | Not suitable for time-sensitive projects |

| LRA | Fast | PacBio only | Rapid processing for PacBio data | Limited platform compatibility |

| GraphMap2 | Computationally intensive | Nanopore, PacBio | Produces reliable alignments | Not practical for whole human genomes |

The selection of alignment tools involves critical trade-offs between computational efficiency, sensitivity, and platform-specific optimization. Notably, no single tool independently resolves all large structural variants (1,001–100,000 base pairs), suggesting that a combined approach using multiple aligners provides more comprehensive genomic characterization [20]. For instance, leveraging both Minimap2 and Winnowmap2 offers different views of the genome, while NGMLR serves as a valuable third option when computational resources permit.

Quality Control and Variant Calling

Following alignment, rigorous quality control measures are essential. For bacterial pathogens like Mycobacterium tuberculosis, recommended practices include excluding sites with low Empirical Base-level Recall scores (<0.9), removing regions in mobile genetic elements, and filtering SNP sites with excessive missing data (>10% of strains) [18]. These steps reduce false positives in subsequent transmission analyses. The resulting genotypes matrix forms the foundation for phylogenetic inference and transmission reconstruction.

Phylogenetic Inference and Evolutionary Models

Molecular Clock Models and Tree Priors

Phylogenetic inference constitutes the core of phylodynamic analysis, with methodological choices significantly impacting parameter estimation. Studies comparing tree-prior models for influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 have demonstrated that birth-death models with informative epidemiological priors produce substantially different estimates of the basic reproduction number (R0) compared to coalescent models [21]. Birth-death models incorporating prior knowledge about infection duration (mean ≥1.3 to ≤2.88 days) yielded R0 estimates that showed no significant difference (p = 0.46) from surveillance-based estimates, while coalescent models consistently produced lower values (mean ≤1.2) [21].

The selection of evolutionary models also critically impacts inference accuracy. Structured coalescent models like SCOTTI (Structured Coalescent Transmission Tree Inference) explicitly incorporate host and environmental structure, enabling more realistic reconstruction of transmission pathways in complex epidemics [22]. These models account for differences in mutation rates and population dynamics between host and non-host environments, which otherwise obscure phylogenetic inference when pathogens can persist or reproduce in environmental reservoirs [22].

Multi-scale Coalescent Frameworks

Conventional phylodynamic approaches often assume negligible within-host genetic diversity, but this simplification can introduce substantial bias. Multi-scale coalescent models (MSCoM) address this limitation by simultaneously modeling within-host evolution and between-host transmission [2]. These approaches estimate the distribution of lineages occupying individual hosts rather than simply the effective number of infections, accommodating non-negligible within-host effective population sizes and imperfect transmission bottlenecks [2].

For pathogens like HIV-1, where within-host diversity is significant, conventional coalescent models show upward bias in estimating the number of infected hosts, while multi-scale models demonstrate greater consistency with reported diagnosis rates [2]. This framework also enables estimation of within-host effective population size from single sequences per host, expanding analytical possibilities from commonly available outbreak data [2].

Transmission Network Reconstruction

Reconstruction Method Comparison

The translation of phylogenetic trees into transmission networks represents the culminating stage of the inference pipeline. Multiple computational tools exist for this purpose, with performance characteristics that vary substantially across different epidemiological contexts. A systematic comparison of six transmission reconstruction models for Mycobacterium tuberculosis revealed significant variability in the number of transmission links predicted with high probability (P ≥ 0.5) and generally low accuracy against known transmission events in simulated outbreaks [23].

Table 2: Performance of Transmission Reconstruction Tools for Tuberculosis

| Tool | Sensitivity | Specificity | Notable Features | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TransPhylo | Moderate | High | Identifies unobserved cases | Suitable for outbreak settings |

| Outbreaker2 | Moderate | High | Flexible model specification | Various transmission scenarios |

| Phybreak | Moderate | High | Accounts for source population | Ideal for low-incidence settings |

| SCOTTI | Varies with diversity | High | Incorporates environmental transmission | Complex transmission pathways |

Notably, models like TransPhylo, Outbreaker2, and Phybreak demonstrated that a relatively high proportion of their predicted transmission events represented true links, despite overall challenges in sensitivity [23]. The performance of these tools depends critically on sufficient between-host genetic diversity, which sets a lower bound on when accurate phylodynamic inferences can be made [22].

SNP Threshold Approaches

For specific pathogens like Mycobacterium tuberculosis, SNP distance thresholds provide an alternative approach for identifying transmission events. Phylodynamic assessment using the phybreak model to infer transmission events has suggested that a SNP cut-off of 4 captures 98% of inferred transmission while reducing false links, while distances beyond 12 SNPs effectively exclude direct transmission [18]. This approach offers valuable validation for threshold-based methods commonly used in public health investigations of tuberculosis outbreaks.

Validation with Epidemiological Data

Hypothesis Testing Frameworks

A critical advancement in phylodynamics is the development of formal frameworks for testing epidemiological hypotheses using phylogenetic data. Spatially explicit phylogeographic analyses enable researchers to quantitatively assess the impact of environmental factors on pathogen dispersal [10]. For West Nile virus in North America, such approaches have demonstrated that viral lineages tend to disperse faster in areas with higher temperatures while avoiding regions with higher elevation and forest coverage [10].

These landscape phylogeographic techniques employ statistical tests comparing observed phylogenetic patterns against null dispersal models, providing rigorous evidence for environmental drivers of transmission. Similarly, phylodynamic models can identify temporal variation in temperature as a predictor of viral genetic diversity through time, establishing critical connections between environmental variables and evolutionary dynamics [10].

Multi-scale Model Integration

The most robust validation comes from integrating phylodynamic inference with multi-scale modeling frameworks that capture complex epidemiological dynamics. Agent-based models coupled with phylodynamic components, such as the Phylodynamic Agent-based Simulator of Epidemic Transmission, Control, and Evolution (PhASE TraCE), can replicate essential features of pandemics while incorporating pathogen evolution within individual hosts [24].

These integrated frameworks demonstrate how feedback loops between public health interventions, population behavior, and pathogen evolution shape transmission dynamics, enabling validation through comparison with real-world surveillance data [24]. Such approaches have replicated the punctuated evolution of SARS-CoV-2, capturing the emergence and dominance of variants of concern in alignment with observed epidemiological patterns [24].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Simulated Epidemic Analysis

Purpose: To evaluate transmission reconstruction accuracy under controlled conditions with known transmission history [22] [23].

Methodology:

- Simulate epidemics using stochastic network models with predefined direct/indirect transmission proportions

- Incorporate pathogen evolution with specified mutation rates in host and non-host environments

- Generate whole-genome sequence data from simulated outbreaks

- Apply multiple transmission reconstruction tools (e.g., SCOTTI, TransPhylo, Outbreaker2, Phybreak)

- Compare inferred transmission networks to known simulated transmission history

Key Parameters: Direct/indirect transmission ratio, mutation rate, population structure, sampling density [22]

Validation Metrics: Sensitivity, specificity, proportion of true links correctly identified, accuracy of transmission directionality [23]

Protocol 2: SNP Threshold Validation

Purpose: To determine optimal SNP cut-offs for identifying transmission events using phylodynamic inference as reference [18].

Methodology:

- Collect whole-genome sequences from surveillance (e.g., 2,008 M. tuberculosis sequences)

- Perform transitive clustering with conservative SNP threshold (e.g., 20 SNPs) to define genetic clusters

- Apply phylodynamic model (e.g., phybreak) to infer transmission events within clusters

- Calculate proportion of inferred transmission events below various SNP cut-offs (1-12 SNPs)

- Identify optimal cut-offs for ruling in and ruling out transmission

Key Parameters: Genetic distance threshold, lineage-specific mutation rates, epidemiological parameters [18]

Validation Metrics: Proportion of inferred transmissions captured, reduction in non-transmission links, cluster size distribution [18]

Workflow Visualization

Figure 1: Phylodynamic Inference Pipeline

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Computational Tools

| Item | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Illumina HiSeq2500 | Short-read sequencing (2 × 125bp) | Bacterial WGS (e.g., M. tuberculosis) [18] |

| Oxford Nanopore | Long-read sequencing | Structural variant detection [20] |

| Pacific Biosciences | SMRT CCS (HiFi) sequencing | High-accuracy long reads [20] |

| BWA mem | Read alignment to reference | Pre-processing for variant calling [18] |

| fastp | Read trimming and quality control | Data pre-processing [18] |

| Pilon | Variant calling | SNP identification [18] |

| BEAST2 | Bayesian evolutionary analysis | Phylogenetic inference [22] |

| Phybreak | Transmission tree inference | Outbreak reconstruction [18] |

| TransPhylo | Transmission network inference | Incorporating unobserved cases [18] |

| Sniffles | Structural variant calling | Long-read alignment evaluation [20] |

The complete inference pipeline from sequence alignment to transmission network reconstruction encompasses multiple methodological decision points, each with implications for the validity and interpretation of results. This comparison guide has highlighted how tool selection at each stage—from alignment through phylogenetic inference to transmission reconstruction—affects the accuracy and epidemiological relevance of phylodynamic estimates. Critical evaluation of methods through simulation studies and validation against epidemiological data remains essential as the field advances. The integration of multi-scale models that account for within-host diversity, environmental transmission, and complex population structure represents the most promising direction for bridging the gap between sequence-based inference and epidemiological reality. Researchers must carefully consider these methodological considerations when designing studies and interpreting phylodynamic results for public health decision-making and drug development.

Advanced Computational Frameworks for Phylodynamic Inference and Validation

The rapid expansion of pathogen genomic data, fueled by advancements in next-generation sequencing, has created an pressing need for phylodynamic methods that can scale efficiently to large outbreaks without sacrificing inferential accuracy. Phylodynamic models, which integrate epidemiological transmission dynamics with evolutionary genetic processes, provide a powerful framework for reconstructing unobserved transmission trees (who-infected-whom) and estimating key epidemiological parameters [25]. These inferences are critical for understanding superspreading events, estimating reproductive numbers, and informing public health interventions during ongoing outbreaks.

However, many existing phylodynamic approaches face significant computational constraints that limit their practical application to large-scale outbreaks. Existing methods often rely on non-mechanistic or semi-mechanistic approximations of the underlying epidemiological-evolutionary process, while those employing exact Bayesian mechanistic frameworks typically encounter exponential scaling issues with increasing outbreak size [25] [26]. This review examines ScITree, a recently developed scalable Bayesian framework that addresses these computational barriers while maintaining high inference accuracy, positioning it as a transformative tool for contemporary genomic epidemiology.

Methodological Framework: How ScITree Achieves Scalability

Core Computational Innovation: Infinite Sites Assumption

ScITree's breakthrough in computational efficiency stems primarily from its strategic approach to modeling genetic mutations. Unlike the previous method by Lau et al. which explicitly modeled mutations at the nucleotide level—requiring computationally intensive imputation of all unobserved transmitted sequences for each base pair—ScITree adopts the infinite sites assumption for mutation modeling [25] [26] [27].

This fundamental shift in modeling strategy reduces the parameter space dramatically. Rather than tracking individual nucleotide changes, ScITree models mutations as accumulating through time according to a Poisson process, where each genetic site mutates at most once in the entire outbreak history [27]. This approach significantly decreases the computational burden associated with exploring the high-dimensional parameter space during Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling, enabling the method to scale linearly with outbreak size compared to the exponential scaling of the Lau method [25].

Integrated Epidemiological-Evolutionary Model

ScITree implements a fully Bayesian mechanistic framework that integrates both epidemiological and evolutionary processes using an exact likelihood function [25]. The model incorporates:

- Stochastic SEIR Framework: A continuous-time spatio-temporal Susceptible-Exposed-Infectious-Removed (SEIR) compartmental model that accounts for individual-level infection dynamics [25] [27]

- Spatial Transmission Kernel: An exponentially-decaying spatial kernel function that modulates transmission probability based on distance between individuals [25]

- Data-Augmentation MCMC: A computationally efficient algorithm that infers key model parameters and unobserved dynamics, including the complete transmission tree [25] [26]

This integrated approach enables joint inference of epidemiological parameters and evolutionary dynamics without relying on the sequential or iterative approximation schemes employed by many other phylodynamic methods [25].

Comparative Methodological Approaches

Table 1: Comparison of Phylodynamic Methodological Frameworks

| Methodological Feature | ScITree | Lau Method | Timtam | Phybreak |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutation Model | Infinite sites assumption | Nucleotide-level explicit modeling | Birth-death process with phylogenetic information | SNP distance-based |

| Epidemiological Framework | Fully mechanistic SEIR | Fully mechanistic SEIR | Birth-death process | Individual-based transmission |

| Inference Approach | Full Bayesian with exact likelihood | Full Bayesian with exact likelihood | Approximate likelihood | Bayesian inference |

| Computational Scaling | Linear with outbreak size | Exponential with outbreak size | Varies with dataset | Moderate scaling |

| Tree Inference | Transmission tree | Transmission tree | Phylogenetic tree | Transmission tree |

Performance Benchmarking: Experimental Validation and Comparative Analysis

Computational Efficiency and Scaling Performance

ScITree's computational advantages have been rigorously validated through multiple simulated outbreak datasets [25] [26]. The experimental results demonstrate that while ScITree achieves inference accuracy comparable to the Lau method, it does so with dramatically improved computational efficiency.

Table 2: Computational Performance Comparison Across Phylodynamic Methods

| Method | Outbreak Size | Computational Time | Transmission Tree Accuracy | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ScITree | ~500 cases | Linear scaling | ~95% accuracy (simulated data) | Infinite sites assumption may not fit all pathogens |

| Lau Method | ~100 cases | Exponential scaling | ~96% accuracy (simulated data) | Computationally prohibitive for large outbreaks |

| Timtam | Varies with sampling | Moderate scaling | Estimates consistent with previous analyses | Requires phylogenetic tree as input in some implementations |

| EpiFusion | Large outbreaks | Particle filter-based | High accuracy in benchmarks | Cannot estimate phylogenetic tree simultaneously |

| Phybreak | ~2,000 sequences | Efficient for cluster analysis | Identifies transmission events missed by contact tracing | Assumes same time-to-detection distributions |

The critical computational advantage of ScITree lies in its scaling behavior. Where the Lau method exhibits exponential increases in computation time with growing outbreak size, ScITree demonstrates linear scaling, making it feasible for application to large-scale outbreaks that are increasingly common in the era of widespread pathogen genomic surveillance [25] [26].

Inference Accuracy Assessment

Despite its computational efficiencies, ScITree maintains high inference accuracy across multiple performance metrics:

- Transmission Tree Reconstruction: In simulation studies, ScITree achieved approximately 95% accuracy in reconstructing transmission trees, comparable to the 96% accuracy of the Lau method despite its simplified mutation model [25] [26]

- Parameter Estimation: Key epidemiological parameters, including reproductive numbers and spatial kernel parameters, were accurately estimated with well-calibrated uncertainty quantification [25]

- Robustness to Incomplete Sampling: The method maintains reasonable accuracy in transmission tree estimation even under moderate sampling coverage, reflecting real-world surveillance conditions where not all infections are observed [25]

These results demonstrate that ScITree's computational advantages do not come at the expense of inferential accuracy, addressing a common trade-off in phylodynamic method development.

Experimental Protocols and Validation Frameworks

Simulation Studies for Method Validation

The development and evaluation of ScITree followed rigorous computational experimental protocols [25]:

- Outbreak Simulation: Multiple outbreak scenarios were generated using stochastic SEIR models with varying population sizes, spatial configurations, and transmission parameters

- Sequence Evolution: Pathogen genetic sequences were simulated along transmission chains using both the infinite sites model (for ScITree validation) and nucleotide-level substitution models (for comparative validation)

- Performance Metrics: Method performance was quantified using transmission tree accuracy, parameter estimation error, computational time, and scaling behavior

- Sampling Scenarios: Different surveillance intensities were simulated to assess performance under varying sampling proportions

This comprehensive validation framework ensures that performance claims are robust across diverse outbreak scenarios and sampling conditions.

Empirical Validation with Foot-and-Mouth Disease Outbreak

To demonstrate real-world utility, ScITree was applied to an empirical dataset from the 2001 Foot-and-Mouth Disease (FMD) outbreak in the United Kingdom [25] [26] [27]. This validation followed a rigorous protocol:

- Data Integration: The analysis incorporated epidemiological data (infection times, farm locations) with genetic sequences from FMD viruses

- Model Implementation: ScITree was deployed to reconstruct the transmission tree between farms and estimate key transmission parameters

- Comparative Benchmarking: Results were compared against previous analyses using the Lau method and epidemiological investigations

- Validation Assessment: Reconstruction accuracy was assessed through consistency with known epidemiological links and previous phylogenetic analyses

The application demonstrated that ScITree could generate estimates consistent with the prior Lau method while requiring substantially less computational resources [25] [27], validating its practical utility for real-world outbreak analysis.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Phylodynamic Inference

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Bayesian Phylodynamic Research

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| ScITree R Package | Implements scalable transmission tree inference | Large-outbreak phylodynamics with sequence data |

| BEAST2 Platform | Bayesian evolutionary analysis sampling trees | General phylogenetic and phylodynamic inference |

| Timtam BEAST2 Package | Combines phylogenetic information with case count time series | Estimation of prevalence and reproduction numbers |

| Phybreak R Package | Transmission tree inference from sequence and epidemiological data | Outbreak cluster investigation and SNP threshold assessment |

| GISAID/GenBank | Public repositories of pathogen genetic sequences | Source of genomic data for phylodynamic analyses |

| ESPALIER Python Package | Reconstruction of ancestral recombination graphs | Phylogenetic analysis in presence of recombination |

Methodological Workflow and Implementation

Comparative Advantages in Different Research Contexts

Application-Specific Method Selection

The appropriate choice among scalable Bayesian methods depends on specific research objectives and data characteristics:

- Large-Outbreak Transmission Inference: ScITree provides optimal performance for outbreaks with hundreds to thousands of cases where detailed transmission tree reconstruction is prioritized [25] [26]

- Prevalence and Reproduction Number Estimation: Timtam offers specialized functionality for integrating case count time series with phylogenetic data to estimate historical prevalence trajectories [3]

- SNP Threshold Determination: Phybreak enables data-driven determination of genetic distance thresholds for transmission clustering, particularly valuable for pathogens like Mycobacterium tuberculosis [18]

- Complex Evolutionary Modeling: BEAST X supports sophisticated evolutionary models with time-dependent rates and accommodates various molecular clock assumptions [28]

Integration with Emerging Methodological Frontiers

ScITree represents part of a broader movement toward more scalable and accurate Bayesian methods in epidemiology. Recent advances in approximate Bayesian inference—including Approximate Bayesian Computation (ABC), Bayesian Synthetic Likelihood (BSL), Integrated Nested Laplace Approximation (INLA), and Variational Inference (VI)—offer complementary approaches for balancing computational efficiency with statistical accuracy [29]. The field is increasingly moving toward hybrid exact-approximate inference methods that combine methodological rigor with the scalability needed for real-time outbreak response.

ScITree represents a significant advancement in scalable Bayesian phylodynamics, addressing a critical methodological gap for large-outbreak transmission tree inference. By combining the infinite sites assumption with a fully mechanistic epidemiological model and efficient MCMC sampling, ScITree achieves linear computational scaling while maintaining inference accuracy comparable to more computationally intensive methods.

For researchers and public health professionals facing large-scale outbreaks with substantial genomic surveillance data, ScITree provides a practical tool for reconstructing transmission trees and estimating key epidemiological parameters. Its integration within the R ecosystem enhances accessibility for applied researchers, while its open-source implementation supports methodological transparency and further development.

As pathogen genomic surveillance continues to expand globally, scalable methods like ScITree will play an increasingly vital role in translating sequence data into actionable public health insights. Future methodological developments will likely focus on further improving computational efficiency while incorporating additional biological realism, such as recombination-aware phylodynamics and non-neutral evolution models [30], creating an increasingly sophisticated toolkit for understanding and controlling infectious disease outbreaks.

The integration of molecular sequence data with epidemiological information has revolutionized our ability to reconstruct the spread and evolution of pathogens. Bayesian evolutionary analysis software has been at the forefront of this revolution, enabling researchers to co-estimate phylogenetic history, evolutionary rates, and population dynamics. The release of BEAST X represents a significant leap forward in this field, introducing a more flexible and scalable platform for evolutionary analysis with a strong focus on pathogen genomics [31]. For researchers and drug development professionals, validating phylodynamic estimates with independent epidemiological data is a critical step in ensuring the reliability of inferences about epidemic spread, intervention effectiveness, and evolutionary trajectories. BEAST X facilitates this validation through advanced modeling capabilities that more accurately capture complex evolutionary and spatial dynamics, thereby generating testable hypotheses that can be directly compared with traditional epidemiological observations.

BEAST X: Core Technological Advances

BEAST X introduces salient advances over previous software versions by providing a substantially more flexible and scalable platform for evolutionary analysis [31]. Its development is motivated by the rapid growth of pathogen genome sequencing, which demands tools capable of delivering real-time inference for the emergence and spread of rapidly evolving pathogens. The advances in BEAST X can be categorized into two thematic thrusts: (1) state-of-science, high-dimensional models spanning multiple biological and public health domains, and (2) new computational algorithms and emerging statistical sampling techniques that notably accelerate inference across this collection of complex, highly structured models [31].

Enhanced Substitution Models

BEAST X incorporates several extensions to existing substitution processes to model additional features affecting sequence changes:

- Markov-Modulated Models (MMMs): These constitute a class of mixture models that allow the substitution process to change across each branch and for each site independently within an alignment [31]. MMMs are made up of K substitution models to construct a KS × KS instantaneous rate matrix used in calculating the observed sequence data likelihood. This approach captures different selective pressures over site and time and has been shown to substantially improve model fit compared with standard continuous-time Markov chain (CTMC) substitution models [31].

- Random-Effects Substitution Models: These extend common CTMC models into a richer class of processes capable of capturing a wider variety of substitution dynamics [31]. Given that random-effects substitution models are generally overparameterized, shrinkage priors can be used to regularize the random effects, pulling them toward zero when the data provide little information. This enables a more appropriate characterization of underlying substitution processes while retaining the basic structure of biologically motivated base models [31].

Advanced Molecular Clock and Coalescent Models

BEAST X complements flexible sequence substitution models with advanced extensions to nonparametric tree-generative models:

- Time-Dependent Evolutionary Rate Model: This novel molecular clock model accommodates evolutionary rate variations through time, a phenomenon widely recognized in various organisms with particular prevalence in rapidly evolving viruses [31]. The model builds upon phylogenetic epoch modeling to specify a sequence of unique substitution processes throughout evolutionary history.

- Improved Relaxed Clock Models: BEAST X enhances classic clock models with a newly developed continuous random-effects clock model, a more general mixed-effects relaxed clock model, and a more tractable shrinkage-based local clock model [31]. These improvements better capture various sources of rate heterogeneity on the phylogenetic tree.

- Coalescent Model Advances: The platform includes extensions to nonparametric tree-generative coalescent models that correct for preferential sequence sampling as a function of time and high-dimensional episodic birth-death sampling models [31].

Computational Innovations

A key innovation in BEAST X is the implementation of newly introduced preorder tree traversal algorithms that enable linear-time (O(N)) evaluations of high-dimensional gradients for branch-specific parameters of interest [31]. These scalable gradients, where N represents the number of taxa, enable high-performance Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC) transition kernels to efficiently simulate phylogenetic, phylogeographic, and phylodynamic posterior distributions for parameters that were previously computationally burdensome to learn [31].

Table: Performance Comparison of Sampling Methods in BEAST X

| Model Type | Sampling Method | Relative Efficiency (ESS/unit time) | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nonparametric coalescent (Skygrid) | HMC | 3.2x faster [31] | Inferring past population dynamics |

| Mixed-effects clock models | HMC | 2.8x faster [31] | Capturing rate heterogeneities |

| Continuous-trait evolution | HMC | 3.5x faster [31] | Learning branch-specific rate multipliers |

| Classic approaches | Metropolis-Hastings | 1.0x (baseline) [31] | Standard phylogenetic inference |

Comparative Performance Analysis: BEAST X vs. Alternative Platforms

Comparison with Previous BEAST Versions

BEAST X represents a substantial evolution from its predecessors, particularly in handling complex models and large datasets:

Table: Feature Comparison: BEAST X vs. BEAST 1.x/2.x

| Feature | BEAST X | Previous BEAST Versions |

|---|---|---|

| Gradient Computation | Linear-time (O(N)) algorithms [31] | Slower, less efficient methods |

| Sampling Efficiency | HMC for many models [31] | Primarily Metropolis-Hastings |

| Clock Model Flexibility | Time-dependent, mixed-effects, and shrinkage-based local clocks [31] | Standard relaxed clocks |

| Substitution Models | Markov-modulated and random-effects models [31] | Standard CTMC models |

| Online Analysis | Not explicitly mentioned in search results | Supported via checkpointing [32] |

| Visualization | Compatible with FigTree [33] | Compatible with FigTree [33] |

Experimental Validation of Performance Claims

The quantitative advantages of BEAST X are demonstrated through benchmark experiments comparing its performance across various model configurations and dataset sizes. Applications of linear-time HMC samplers in BEAST X achieve substantial increases in effective sample size (ESS) per unit time compared with conventional Metropolis-Hastings samplers that previous versions of BEAST provide [31]. It's important to note that these speedups are indicative and can be sensitive to the size and nature of the dataset, and to the tuning of the HMC operations [31].

Online Bayesian Phylodynamic Inference

While not explicitly confirmed for BEAST X in the search results, online Bayesian phylodynamic inference represents a crucial capability for epidemiological validation studies, allowing researchers to incorporate new sequence data as it becomes available without completely restarting analyses [32]. This functionality is particularly valuable for ongoing outbreak investigations where new sequences are generated regularly.

The online inference procedure in BEAST (available as of version v1.10.4) involves:

- Generating State Files: Using the

-save_everyand-save_statearguments during BEAST execution to create checkpoint files at regular intervals [32]. - Adding New Sequences: Using the CheckPointUpdaterApp with an existing checkpoint file and an updated XML file containing new sequences to generate a modified checkpoint file [32].

- Resuming Analysis: Loading the updated checkpoint file into BEAST along with the updated XML file to continue the analysis with the expanded dataset [32].

This approach significantly reduces the time to incorporate new data, facilitating more timely comparisons between phylodynamic estimates and emerging epidemiological observations.

Experimental Protocols for Methodological Validation

Protocol 1: Validating Phylogeographic Inference

Objective: To assess the accuracy of spatial spread patterns inferred by BEAST X against known epidemiological data.

Workflow:

- Model Specification: Configure a discrete-trait phylogeographic analysis in BEAST X using the generalized linear model (GLM) extension to parameterize between-location transition rates as log-linear functions of environmental or epidemiological predictors [31].

- Handling Missing Data: Utilize BEAST X's Hamiltonian Monte Carlo approach to jointly sample missing predictor values from their full conditional distribution when parameterizing between-location transition rates [31].

- Accounting for Sampling Bias: Apply novel modeling strategies to address geographic sampling bias sensitivity, a common concern in phylogeographic analyses [31].

- Validation: Compare posterior estimates of migration rates and routes with independently observed case importation data from epidemiological surveillance.