Validating Transmission Clusters: Integrating Contact Tracing and Molecular Data for Epidemic Control

This article provides a comprehensive framework for validating infectious disease transmission clusters by synthesizing traditional contact tracing with advanced molecular epidemiology.

Validating Transmission Clusters: Integrating Contact Tracing and Molecular Data for Epidemic Control

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for validating infectious disease transmission clusters by synthesizing traditional contact tracing with advanced molecular epidemiology. Aimed at researchers and public health professionals, it explores foundational cluster definitions, methodological approaches for integration, strategies for optimizing real-world operations, and rigorous validation techniques. By examining evidence from COVID-19, HIV, and other pathogens, the content offers practical guidance for enhancing cluster detection accuracy, improving resource allocation, and strengthening outbreak response systems for future epidemic preparedness.

Defining Transmission Clusters: Concepts and Public Health Significance

Understanding the dynamics of infectious disease spread requires a precise grasp of key epidemiological concepts, from the fundamental definition of a "contact" to the complex thresholds that govern the emergence of transmission clusters. This guide provides a structured comparison of these core concepts, framed within the critical context of validating transmission chains through contact tracing research. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, accurately defining and measuring these elements is not merely an academic exercise; it is essential for designing effective interventions, forecasting epidemic trajectories, and evaluating the success of public health programs. The following sections break down the terminology, methodologies, and quantitative thresholds that form the foundation of modern infectious disease epidemiology, with a specific focus on how contact tracing data can be validated through advanced techniques like phylogenetic analysis.

Core Definitions: From Contact to Cluster

Foundational Epidemiological Terms

- Contact: A contact is defined by the physical proximity and interaction with an infected person that presents a risk of disease transmission. Definitions often specify a duration of exposure (e.g., more than 15 minutes of close contact) and can include household members or sexual partners [1].

- Contact Tracing: The process of identifying, assessing, and managing individuals who have been exposed to an infected person to prevent onward transmission. It is a cornerstone public health strategy for breaking chains of transmission [1] [2].

- Case (or Index Case): An instance of a particular disease, injury, or other health condition that meets selected clinical criteria. The index case is the first case to come to the attention of health authorities [3].

- Transmission Cluster: An aggregation of cases of a disease in a circumscribed area during a particular period. The term does not inherently imply that the number of cases is more than expected, as the expected number is often not known [3].

- Epidemic Threshold: The critical value of the basic reproduction number (R₀) or other model parameters, above which epidemics are possible and below which epidemics cannot occur [4] [5]. It marks the transition between a disease dying out and becoming self-sustaining in a population.

Defining Contact Proximity and Its Implications

The definition of a "contact" is operational and can vary depending on the pathogen's mode of transmission. For respiratory diseases like COVID-19, it is commonly based on physical proximity and the duration of contact [1]. This often translates to being within 1-2 meters of an infected person for a cumulative period, typically 15 minutes or more. For sexually transmitted infections, the definition centers on sexual partnerships. The precision of this definition directly impacts the efficiency and effectiveness of contact tracing; an overly broad definition can overwhelm systems with low-risk contacts, while an overly narrow one can miss genuine transmission events [6] [2].

Quantitative Thresholds and Their Impact on Transmission Dynamics

The Basic Reproduction Number (R₀) and Epidemic Thresholds

The basic reproduction number, R₀, is a cornerstone concept, defined as the expected number of secondary infections from an initial infectious individual in a completely susceptible population [4]. The epidemic threshold is the critical value of R₀ (typically R₀=1) above which an epidemic is possible [4] [5]. However, in structured populations, this threshold is not absolute. In network models, a more relevant measure is often R*, the expected number of secondary infections from an individual infected early in an epidemic (but not the very first case), who is typically selected with probability proportional to their number of contacts [4].

Table 1: Key Thresholds in Epidemiological Models

| Concept | Definition | Epidemic Implication | Key Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Reproduction Number (R₀) | Average number of secondary cases from one infected individual in a fully susceptible population [4]. | An epidemic is possible if R₀ > 1; the disease dies out if R₀ < 1 [4] [5]. | Transmission rate, recovery rate, contact patterns. |

| Epidemic Threshold (R*) | Critical value of R₀ or other parameters (e.g., transmissibility) marking the phase transition [4]. | Determines the potential for an outbreak to occur and become sustained. | Network structure, contact heterogeneity, disease dynamics [4]. |

| Cluster Threshold | The point at which a group of cases transitions from sporadic to a recognized transmission cluster. | Helps in outbreak detection and resource allocation for control measures. | Contact intensity, population susceptibility, pathogen transmissibility. |

The Role of Network Structure and Contact Dynamics

The structure of contact networks profoundly influences epidemic thresholds. In static network models, the threshold depends on the degree distribution. For uncorrelated annealed networks, the threshold for contagion transmissibility (λc = β/μ) is given by λc =

Experimental Protocols for Validating Transmission Clusters

Methodologies for Assessing Contact Tracing Precision

A novel genomic pipeline has been developed to assess the precision of contact tracing, defined as the proportion of suggested transmission events not contradicted by genomic analysis [6] [8].

Protocol Workflow:

- Case-Contact Pair Identification: Conduct interviews with confirmed index cases to identify their close contacts (case-contact pairs) during their infectious period [6] [2].

- Sample Collection and Sequencing: Collect biological samples from both index cases and their identified contacts. Perform whole-genome sequencing of the pathogen (e.g., SARS-CoV-2) from these samples [6].

- Phylogenetic Analysis: Construct a time-scaled phylogeny (evolutionary tree) using the genomic sequences from all collected samples [6] [8].

- Variant Identification: Classify the sequences by circulating variants (e.g., Omicron BA.1, BA.2) to ensure comparisons are made within the same lineage [8].

- Cluster Validation: Determine if the case-contact pairs identified through tracing cluster together within the phylogeny with high statistical support. Pairs that do not cluster are considered genomically invalidated [6].

- Precision Calculation: Calculate precision as the proportion of traced pairs that are not invalidated by the phylogenetic analysis [6].

Protocol for Evaluating Backward Contact Tracing

Backward contact tracing aims to identify the source of an index case's infection (the parent case) and others infected by the same source (sibling cases) [2].

Experimental Protocol:

- Study Cohort Definition: Define a population cohort for observation, such as a university student body [2].

- Extended Tracing Window: For each index case, extend the contact tracing window backward in time (e.g., to 7 days before symptom onset or diagnosis) instead of the standard 2 days [2].

- Contact Identification and Management: Identify close contacts from this extended window. Refer these "backward-traced" contacts for testing and/or quarantine [2].

- Data Collection: Record the outcome (positive or negative test result) for all contacts, categorizing them as from the standard window or the extended window [2].

- Efficiency Analysis: Calculate the positivity rate (PR) for both groups. Compare the PR of the backward-traced group to a control group (e.g., symptomatic individuals from the general population) to assess efficiency. Also, track metrics like the number of tests per case found and the time from exposure to identification [2].

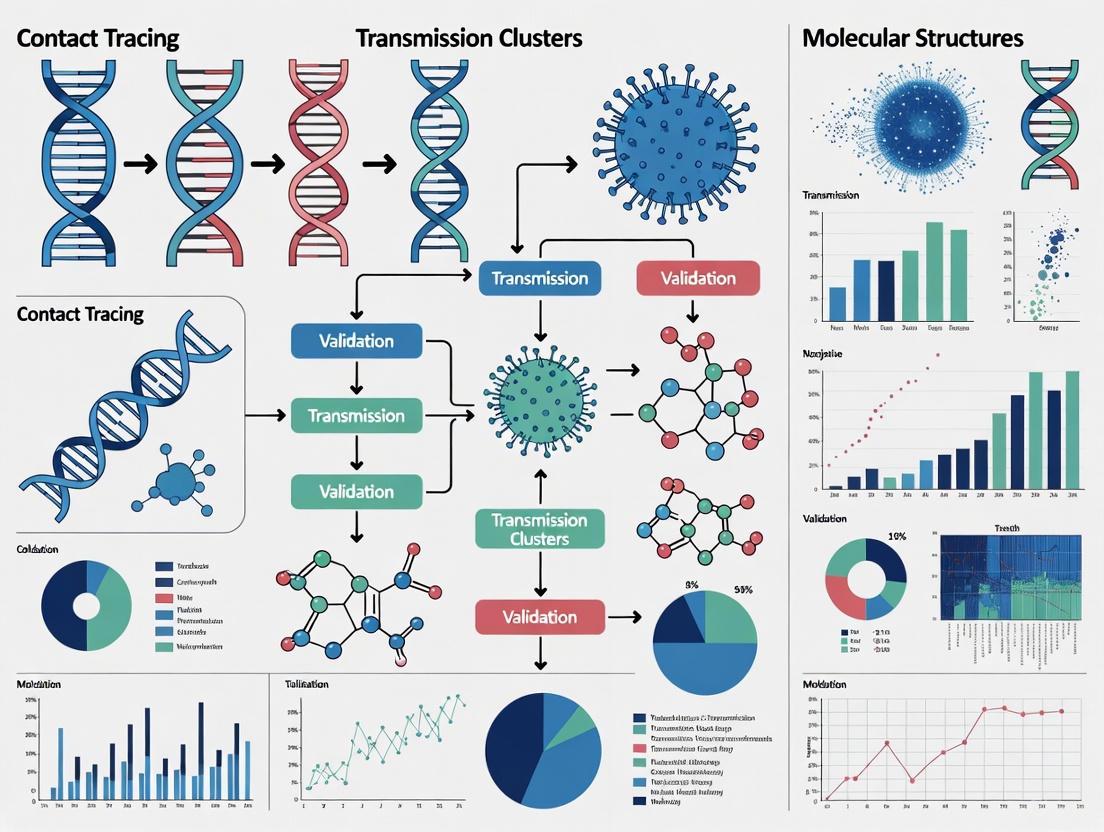

Figure 1: Workflow for Phylogenetic Validation of Contact Tracing Precision

Comparative Effectiveness of Contact Tracing Strategies

Contact tracing is not a monolithic intervention. Its effectiveness varies significantly based on the tracing method used, the context of the outbreak, and the resources available. The following table and analysis compare the performance of different approaches.

Table 2: Comparison of Contact Tracing Methods and Their Documented Effectiveness

| Tracing Method | Definition / Protocol | Context / Scenario | Documented Effectiveness | Key Experimental Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forward Tracing | Identifies contacts of a known index case exposed during the standard contagious period (e.g., 2 days before onset) [9] [2]. | Low case-ascertainment, testing contacts [9]. | Reduced transmission by 12% [9]. | Found to be the least effective method in several comparative scenarios [9]. |

| Extended Tracing | Extends the contact tracing window further back in time (e.g., 16 days before isolation) to find the source of infection [9]. | Low case-ascertainment, quarantine of contacts [9]. | Reduced transmission by 50% [9]. | More effective than forward tracing but less than cluster methods; higher cost in one study [9]. |

| Cluster Tracing | Combines forward tracing with cluster identification, focusing on groups of cases and their shared exposures [9]. | Low case-ascertainment, quarantine of contacts [9]. | Reduced transmission by 62% [9]. | Most effective method in multiple scenarios, sufficient to bring the reproduction number close to unity [9]. |

| Backward Tracing | Aims to identify the infector of the index case (parent case) and other individuals infected by the same source (sibling cases) [2]. | Real-world cohort study in a student population [2]. | Identified 42% more cases as direct contacts of an index case [2]. | Positivity rate among backward-traced contacts was similar to forward-traced contacts and higher than a symptomatic control group [2]. |

| Bidirectional & Secondary Tracing | Combines forward and backward tracing. Secondary tracing involves tracing the contacts of contacts [10]. | Modelling studies and systematic reviews [10]. | Highly effective in modelling studies [10]. | Mathematical modelling identifies it as a highly effective policy for averting cases [10]. |

Synthesis of Comparative Data

The data reveals that cluster tracing consistently demonstrates high effectiveness, particularly in scenarios with quarantine of contacts, where it can reduce transmission by over 60% and bring the reproduction number close to 1 [9]. Backward contact tracing receives strong empirical support, with one large cohort study showing it can identify 42% more cases than standard forward tracing alone [2]. This efficiency is attributed to its ability to find "sibling" cases from a common source, which is crucial for containing pathogens with superspreading potential.

The overall effectiveness of any contact tracing operation is heavily dependent on the implementation context. Operations are most effective when implemented with high case-ascertainment rates and quarantine of contacts, which can stop transmission early and make operations more manageable and less costly [9]. Furthermore, hybrid manual and digital contact tracing with high app adoption is identified as a highly effective policy, especially when combined with effective isolation and social distancing [10].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Transmission Cluster Studies

| Tool / Resource | Category | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Whole-Genome Sequencer | Laboratory Equipment | Determines the complete DNA/RNA sequence of the pathogen from clinical samples for phylogenetic analysis [6] [8]. |

| Phylogenetic Analysis Software | Computational Tool | Builds evolutionary trees from genomic sequences to infer transmission relationships and validate clusters [6] [8]. |

| Contact Tracing Data System | Data Management | A database for storing, managing, and analyzing interview-based contact data, case details, and outcomes [9] [2]. |

| Statistical Computing Package | Analytical Software | Performs statistical analyses, calculates key metrics (e.g., positivity rates, serial intervals), and generates visualizations [2]. |

| Diagnostic Assays | Laboratory Reagent | Confirms active infection in index cases and traced contacts (e.g., RT-qPCR tests for SARS-CoV-2) [2]. |

Figure 2: Core Resources for Contact Tracing Research

In the domain of infectious disease control, cluster validation is the critical process of confirming that identified groups of cases, or "clusters," represent genuine transmission events linked by a common source or chain of infection. This process moves beyond simple case clustering to provide epidemiological confirmation that connections between cases are biologically plausible and not merely coincidental. Within contact tracing research, validation transforms raw data from case interviews into reliable intelligence about transmission patterns. The imperative for rigorous cluster validation stems from the resource-intensive nature of public health interventions; without validation, health agencies risk misdirecting limited resources toward false leads while missing genuine outbreaks. As countries worldwide have implemented diverse contact tracing approaches during the COVID-19 pandemic, the critical importance of validating identified clusters has emerged as a consistent theme in outbreak management [11] [1].

The fundamental challenge in cluster investigation lies in distinguishing true transmission chains from coincidental case aggregations. This challenge is particularly acute for highly transmissible pathogens like SARS-CoV-2, where asymptomatic transmission and overdispersion (superspreading events) can create complex transmission patterns that defy conventional investigation methods [12] [13]. Cluster validation provides the methodological framework to address this challenge, incorporating approaches from genomic epidemiology, bioinformatics, and statistical modeling to confirm suspected outbreaks. As public health systems evolve toward more sophisticated surveillance capabilities, cluster validation represents the essential quality control mechanism that ensures epidemiological insights translate into effective disease control.

Comparative Effectiveness of Cluster Investigation Methods

Quantitative Outcomes of Different Tracing Strategies

The effectiveness of cluster-based approaches compared to standard contact tracing methods varies significantly across diseases and operational contexts. The following table summarizes key performance metrics from recent studies comparing these methodologies:

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Cluster vs. Standard Contact Tracing

| Tracing Method | Disease Context | Contacts Identified per Case | Key Performance Metrics | Study Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotyped Cluster Investigation | Tuberculosis (Florida, 2009-2023) | 4.82 contacts/case | 81.5% contacts evaluated; 20.4% LTBI diagnosis rate; 92.9% treatment initiation [14] | |

| Standard Contact Investigation | Tuberculosis (Florida, 2009-2023) | 3.79 contacts/case | 85.5% contacts evaluated; 21.5% LTBI diagnosis rate; 95.9% treatment initiation [14] | |

| Cluster Tracing Method | COVID-19 (Modelling, Singapore) | N/A | 62% transmission reduction (low ascertainment, quarantine); most effective of three methods [9] | |

| Exposure Cluster Surveillance | COVID-19 (England, 2020-2021) | N/A | 25% genetically validated; 81% not otherwise recorded; 1-day earlier detection [13] |

Cluster investigations demonstrate a clear advantage in contact identification volume, particularly for tuberculosis control, where genotyped clusters identified approximately 27% more contacts per case than standard investigations [14]. This expanded reach enables public health systems to cast a wider net around potential transmission chains. However, the quality of subsequent engagement and care progression shows nuanced differences, with standard contact investigations achieving slightly higher rates of contact evaluation and treatment initiation in the TB care cascade [14]. This suggests that while cluster methods excel at case finding, maintaining the quality of downstream interventions remains essential.

For respiratory pathogens like SARS-CoV-2, modeling studies indicate that cluster tracing methods outperform both forward tracing (identifying future potential cases) and extended tracing (covering longer periods before case isolation), particularly in scenarios with low case ascertainment. When combined with quarantine of contacts, cluster tracing reduced transmission by 62%—enough to bring the reproduction number close to unity—and proved to be the least costly approach among alternatives [9]. This demonstrates the pivotal role of cluster-focused strategies in pandemic control when resources are constrained.

Validation Rates Across Settings and Methodologies

The accuracy of cluster detection varies substantially across different environmental contexts and methodological approaches. The following table compares validation rates from multiple studies:

Table 2: Cluster Validation Rates Across Methodologies and Settings

| Validation Methodology | Setting/Context | Cluster Validation Rate | Key Influencing Factors | Study Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic Phylogenetics | University setting (Belgium, Omicron waves) | 34.6% precision | Combined phylogenetic + SNP analysis; serial interval refinement [8] | |

| Exposure Data Matching | Community settings (England, 2020-2021) | 25% genetic validity | Workplace and educational settings showed highest validity [13] | |

| Digital Contact Tracing | National rollout (Norway, 2020) | 80% technological efficacy | Varying detection by phone type (Android: 74%, iOS: 54%) [15] | |

| Bayesian Case Linking | Synthetic network simulation | Varying by parameters | Household size, population size, algorithm parameters [12] |

The setting of potential transmission events significantly influences validation likelihood. In England's enhanced contact tracing programme, exposure clusters occurring in workplaces (aOR = 5.10, 95% CI 4.23–6.17) and educational settings (aOR = 3.72, 95% CI 3.08–4.49) demonstrated the strongest association with genetic validity in multivariable analysis [13]. This highlights the epidemiological importance of these environments for SARS-CoV-2 transmission and suggests that setting-based risk assessment can prioritize investigation resources.

The validation methodology itself substantially impacts measured accuracy. Genomic approaches provide high-resolution validation but may be resource-intensive for routine application. Belgium's phylogenetic validation of a university contact tracing program achieved a precision rate of 34.6%, meaning just over one-third of epidemiologically-identified case-contact pairs were not contradicted by genomic evidence [8]. This underscores both the value of genomic validation for refining transmission understanding and the potential for over-estimation of linkage in purely epidemiological assessments.

Experimental Protocols for Cluster Validation

Genomic Validation Pipeline

Genomic methods provide the gold standard for cluster validation by establishing biological relatedness between cases. The following workflow outlines a phylogenetically-validated assessment approach:

Figure 1: Genomic Validation Pipeline for Transmission Clusters

This pipeline was implemented in a study of SARS-CoV-2 transmission at Belgium's largest university during Omicron BA.1 and BA.2 waves. Researchers analyzed 459 case-contact pairs identified through contact tracing, then used combined phylogenetic and single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) analysis to determine whether pairs infected with the same variant clustered together within a time-scaled phylogeny [8]. This approach calculated precision as the proportion of transmission events suggested by contact tracing that were not contradicted by genomic analysis, yielding a validation rate of 34.6% [8]. The genomic data enabled more accurate estimation of epidemiological parameters like serial intervals, with refined estimates showing smaller standard deviation than those derived from all case-contact pairs [8].

Automated Cluster Detection Algorithm

For rapid assessment during outbreaks, automated computational approaches can provide preliminary cluster validation:

Figure 2: Automated Cluster Detection Workflow

This algorithm utilizes a Bayesian approach to probabilistically link cases using either the serial interval or generation interval [12]. The method was developed and tested using synthetic social networks created with the epinet R package, representing geography, households, and primary spoken language [12]. Outbreak simulation employed an SEIR (Susceptible-Exposed-Infected-Removed) model with parameters including a contact rate (β) of 0.2 (representing exponentially distributed 5 days of infection), gamma-distributed latency period (average 0.14 days), and recovery period (average 5.44 days) [12]. The "connectprobablecases" function from the autotracer package returns transmission pairs with the highest posterior likelihood of being true transmission events, with unlikely pairs truncated using a default threshold of 30 days between recorded cases [12]. Performance is assessed by comparing the actual versus detected number of clusters and average cluster size using root mean squared error (RMSE) [12].

Exposure Cluster Surveillance System

England's Enhanced Contact Tracing Programme implemented a systematic approach to cluster surveillance based on case exposure data:

Figure 3: Exposure Cluster Surveillance System

This system analyzed data from cases occurring between October 2020 and September 2021, extracting exposure information from the national contact tracing system [13]. The methodology identified exposure clusters algorithmically by matching two or more cases attending the same event, using postcode and event category matching within a 7-day rolling window [13]. Genetic validity was defined as exposure clusters with two or more cases from different households with identical viral sequences [13]. The system identified 269,470 exposure clusters, with 25% (3,306/13,008) of eligible clusters proving genetically valid [13]. Crucially, 81% (2,684/3,306) of these validated clusters were not recorded in the national incident management system and were identified on average one day earlier than officially recorded incidents [13], demonstrating the added value of systematic exposure cluster surveillance.

Technical Implementation and Research Toolkit

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

The experimental protocols described require specialized reagents, software tools, and analytical frameworks. The following table details key solutions for implementing cluster validation methodologies:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Cluster Validation

| Tool/Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic Sequencing | Whole genome sequencing; Spoligotyping; MIRU-VNTR; wgMLST | Genotype characterization; Cluster definition | Tuberculosis [14]; SARS-CoV-2 [8] [13] |

| Bioinformatic Packages | epinet R package; autotracer package; outbreaker2 R package; igraph package | Network simulation; Bayesian case linking; Transmission tree analysis | Synthetic network modeling [12]; Clustering algorithms [12] |

| Cluster Validation Indices | SLEDgeH (Support, Length, Exclusivity, Difference) | Categorical data validation; Semantic cluster description | Non-metric cluster validation [16] |

| Digital Tracing Frameworks | Exposure Notification System (ENS); Smittestopp; Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) | Proximity detection; Contact event logging | Digital contact tracing [15] |

| Statistical Platforms | R version 4.1.3; Bayesian probabilistic models; Multivariable logistic regression | Statistical analysis; Model parameterization; Uncertainty quantification | Performance assessment [12] [13] |

The bioinformatic packages enable critical analytical functions. The epinet R package facilitates synthetic social network generation and outbreak simulation, while the autotracer package implements Bayesian approaches for probabilistic case linking [12]. The outbreaker2 R package utilizes Bayesian methods to probabilistically link cases using serial intervals or generation intervals, and the igraph package implements greedy clustering algorithms for transmission tree analysis [12]. For genomic validation, phylogenetic analysis tools combined with SNP calling pipelines provide the biological resolution needed to confirm or refute epidemiological links [8] [14].

For categorical data validation, recent advances in cluster validation indices like SLEDgeH (an enhanced version of the SLEDge framework) provide specialized approaches for evaluating clustering quality in categorical data common in epidemiological records [16]. Unlike conventional distance-based indices, SLEDgeH uses optimized weighting of semantic descriptors derived from frequent patterns, combining four indicators—Support, Length, Exclusivity, and Difference—through weight optimization to improve cluster discrimination [16]. This approach is particularly valuable for patient record data where traditional distance metrics may fail to capture meaningful relationships.

Technological Efficacy in Digital Tracing Systems

Digital contact tracing systems present unique validation challenges and opportunities. Analysis of Norway's Smittestopp app rollout revealed a technological tracing efficacy of 80%, with significant variation between mobile operating systems: Android devices detected other Android devices with 74% probability, while iPhone-iPhone detection was 54% [15]. The overall effectiveness followed a quadratic relationship with app uptake, with the detection probability for different device pairings being: pii = 0.54 (iPhone detects iPhone), pai = 0.53 (Android detects iPhone), pia = 0.53 (iOS detects Android), and paa = 0.74 (Android detects Android) [15]. This technological efficacy represents the upper bound of performance for digital tracing systems, which also depends on population uptake and adherence.

The research indicated that at least 11.0% of discovered close contacts could not have been identified by manual contact tracing alone [15], highlighting the added value of digital approaches. The study also suggested that digital contact tracing can flag individuals with excessive contacts, potentially helping to contain superspreading-related outbreaks [15]. While the overall effectiveness of digital tracing depends strongly on app uptake, significant impact can be achieved at moderate uptake levels (40%) when combined with fast and effective case isolation [15].

Cluster validation represents more than a technical exercise in epidemiological methodology—it establishes the fundamental unit of analysis for effective outbreak control. As the comparative evidence demonstrates, validated clusters provide the precision necessary to target interventions toward genuine transmission events rather than coincidental case aggregations. The experimental protocols detailed—from genomic pipelines to automated detection algorithms—provide a methodological toolkit for transforming raw case data into confirmed transmission chains.

The future of cluster validation lies in integrated approaches that combine the complementary strengths of genomic confirmation, algorithmic pattern recognition, and digital exposure assessment. As validation methodologies become more sophisticated and accessible, they will increasingly form the backbone of evidence-based outbreak response. For researchers and public health professionals, investing in robust cluster validation capabilities represents not merely a technical specialization but a foundational commitment to precision public health—where limited resources are deployed with maximum impact based on rigorously validated transmission intelligence.

Cluster typology analysis is a foundational tool in infectious disease epidemiology, enabling researchers to dissect the heterogeneous nature of disease transmission. In the context of SARS-CoV-2, the identification and characterization of distinct cluster types—particularly household, occupational, and super-spreading events—has proven critical for developing targeted interventions. This guide provides a systematic comparison of these transmission settings, drawing upon contact tracing data and cluster analysis methodologies to validate their unique characteristics. By objectively examining the performance of different intervention strategies across settings and presenting supporting experimental data, this analysis aims to equip researchers and public health professionals with evidence-based frameworks for outbreak management.

The substantial variation in transmission dynamics across different environments underscores the importance of moving beyond population-wide averages to setting-specific understandings of spread. Cluster analysis, an unsupervised learning algorithm that groups data points based on their similarities without pre-defined categories [17], provides the methodological foundation for this approach. When applied to COVID-19 outbreaks, this technique allows for the identification of inherent patterns in transmission data, revealing critical differences in transmission potential, overdispersion, and intervention effectiveness across settings [18] [19].

Comparative Analysis of Cluster Typologies

Quantitative analysis of transmission clusters reveals significant differences in transmission potential and heterogeneity across settings. The following comparison synthesizes data from multiple studies to provide a comprehensive overview of these typologies.

Table 1: Transmission Parameters by Cluster Typology

| Transmission Setting | Effective Reproduction Number (R) | Dispersion Parameter (k) | Superspreading Threshold Probability | Proportion of Cases Causing 80% of Spread |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Population | 0.56 (0.50-0.64) [18] | 0.22 (0.19-0.26) [18] | 1.75% (1.57-1.99%) [18] | 13.14% (11.55-14.87%) [18] |

| Household | 0.14 (0.11-0.17) [18] | 0.14 (0.10-0.21) [18] | 0.07% (0.06-0.08%) [18] | 30% responsible for 80% of spread [19] |

| Healthcare Facilities | 0.19 (0.08-0.41) [18] | 0.004 (0.002-0.006) [18] | 0.67% (0.31-1.21%) [18] | 15-20% responsible for 80% of spread [19] |

| Restaurants/Social Dining | Not reported | 0.1-0.5 [19] | Not reported | 25% responsible for 80% of spread [19] |

| Close-Social Indoor Activities | 7.1 [19] | ~0.3 [19] | Not reported | ~10% responsible for 80% of spread [19] |

| Retail & Leisure | 0.58 (0-1.17) [19] | 0.05 (0.01-0.09) [19] | Not reported | 5% responsible for 80% of spread [19] |

| Office Work | 0.38 (0.26-0.50) [19] | ~0.3 [19] | 0.32% (0.21-0.60%) [18] | 15-20% responsible for 80% of spread [19] |

Table 2: Cluster Distribution and Size by Setting (Hong Kong Data, 2020-2021)

| Transmission Setting | Number of Identified Clusters | Percentage of All Clusters | Maximum Observed Cluster Size | Asymptomatic Proportion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Household | 3,318 | 87.1% | Small to medium | 12-39% [19] |

| Office Work | 365 | 9.6% | ≤10 cases | 12-39% [19] |

| Restaurants | 282 | 7.4% | Medium | 12-39% [19] |

| Manual Labour Work | 253 | 6.6% | ~50 cases | 12-39% [19] |

| Retail & Leisure | 108 | 2.8% | ~50 cases | 12-39% [19] |

| Nosocomial | 80 | 2.1% | Medium | 12-39% [19] |

| Close-Social Indoor | 61 | 1.6% | 395 cases | 12-39% [19] |

| Residential Care Homes | 59 | 1.5% | ~50 cases | 12-39% [19] |

Key Observations from Comparative Data

- Household transmission demonstrates the lowest reproduction number but accounts for the vast majority of clusters (87.1%), representing the most common but least explosive transmission setting [19].

- Close-social indoor settings (including bars, social gatherings, and religious events) show the highest mean number of new infections per cluster (CZ = 7.1) and have been associated with the largest documented clusters (up to 395 cases) [19].

- Occupational settings display variable transmission patterns, with office work showing lower transmission potential (CZ = 0.38) compared to manual labor settings (CZ = 1.0-1.5) [19].

- Retail and healthcare environments exhibit extreme transmission heterogeneity (k = 0.05 and 0.004, respectively), indicating high superspreading potential where a very small percentage of cases (5% and 0.44%, respectively) generate the majority of infections [18] [19].

Experimental Protocols for Cluster Validation

Contact Tracing Methodologies

Contact tracing serves as the primary experimental protocol for validating transmission clusters and establishing links between cases. Different methodological approaches yield varying levels of effectiveness:

Table 3: Contact Tracing Method Effectiveness Under Different Scenarios

| Tracing Method | Low Case-Ascertainment with Testing | Low Case-Ascertainment with Quarantine | High Case-Ascertainment with Testing | High Case-Ascertainment with Quarantine |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forward Tracing (2 days before isolation) | 12% transmission reduction | 46% transmission reduction | 20% transmission reduction | Equally effective (All methods bring R<1) |

| Extended Tracing (16 days before isolation) | Intermediate effectiveness | 50% transmission reduction (Highest cost) | Intermediate effectiveness | Equally effective (All methods bring R<1) |

| Cluster Tracing (Forward + cluster identification) | 22% transmission reduction (Most effective) | 62% transmission reduction (Most effective, least costly) | 26% transmission reduction (Most effective) | Equally effective (All methods bring R<1) |

Protocol Details:

- Case Identification and Interview: Laboratory-confirmed cases are interviewed to identify their contacts and exposure settings. In the Hong Kong protocol, cases were classified based on detailed contact histories [19] [20].

- Contact Categorization: Contacts are classified by setting (household, workplace, social, etc.) and exposure risk level.

- Transmission Pair Construction: Infector-infectee pairs are established based on epidemiological links, with verification through symptom onset dates and exposure windows [18].

- Cluster Definition: Clusters are defined as ≥2 linked cases with evidence of local transmission, distinguished from sporadic cases or imported infection chains [20].

- Data Analysis: The number of secondary cases generated by each infector is fitted to a negative binomial distribution to estimate the effective reproduction number (R) and dispersion parameter (k) using Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods [18].

Cluster Analysis and Statistical Modeling

The validation of transmission clusters relies on sophisticated statistical approaches that account for the overdispersed nature of SARS-CoV-2 transmission:

Cluster Validation Workflow

Negative Binomial Modeling Protocol:

- Data Preparation: Clean and structure contact tracing data into infector-infectee pairs, excluding cases with incomplete information [18] [21].

- Model Selection: Select the negative binomial distribution to model the number of secondary cases, as it accommodates overdispersion better than the Poisson distribution [18] [19].

- Parameter Estimation: Use maximum likelihood estimation or Bayesian methods (e.g., MCMC) to estimate the effective reproduction number (R, the mean of the distribution) and dispersion parameter (k, measuring heterogeneity) [18].

- Setting-specific Analysis: Conduct subgroup analyses for different transmission settings (household, workplace, social) to estimate setting-specific R and k values [18] [19].

- Superspreading Threshold Calculation: Define superspreading events (SSEs) using the 99th percentile of the Poisson distribution with the estimated R as the threshold [18].

- Validation: Assess model fit using goodness-of-fit tests and compare observed versus expected cluster size distributions [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for Transmission Cluster Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Contact Tracing Data | Provides line-list of cases with epidemiological links | Construct transmission chains and identify settings [18] [19] |

| Negative Binomial Model | Statistical framework for overdispersed count data | Estimate reproduction number (R) and dispersion parameter (k) [18] [20] |

| Cluster Analysis Algorithms | Unsupervised learning to identify natural groupings | Segment transmission events into typologies without pre-defined categories [17] |

| Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) | Bayesian parameter estimation method | Generate posterior distributions for R and k with credible intervals [18] |

| Generation Interval Data | Time between successive cases in a transmission chain | Understand transmission dynamics and timing of interventions [19] |

The validation of transmission clusters through contact tracing research reveals fundamental insights into the heterogeneous nature of SARS-CoV-2 transmission. Household settings, while numerically dominant, demonstrate relatively limited transmission potential compared to occupational and social environments. Conversely, superspreading events, particularly in close-social indoor settings and environments with high interaction densities, drive a disproportionate share of transmission despite representing a small minority of clusters.

This comparative analysis underscores the critical importance of setting-specific interventions. Rather than uniform approaches, effective outbreak control requires tailored strategies that address the unique transmission dynamics of each typology. For researchers and public health professionals, the methodological frameworks presented here provide actionable tools for identifying, analyzing, and responding to diverse transmission scenarios in ongoing and future infectious disease outbreaks.

In infectious disease epidemiology, the serial interval and reproduction number serve as fundamental metrics for quantifying transmission dynamics. The serial interval represents the time between symptom onset in a primary case and a secondary case, providing crucial information about the speed of disease spread [22]. The effective reproduction number (Rt) indicates the average number of new infections generated by each infected individual at a specific time within a population. Accurate estimation of these parameters is essential for designing effective public health interventions, forecasting epidemic trajectories, and assessing the impact of control measures.

The validation of transmission clusters represents a critical challenge in epidemiological research, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. Traditional methods relying on contact tracing data alone face significant limitations, including incomplete sampling, recall bias, and resource constraints that vary substantially across jurisdictions [23]. Emerging approaches that integrate genomic epidemiology with traditional methods offer promising avenues for overcoming these limitations, providing higher resolution estimates of transmission parameters and strengthening the validation of inferred transmission clusters [22] [13].

Comparative Analysis of Estimation Methods

Traditional Contact Tracing Approaches

Traditional methods for estimating serial intervals and reproduction numbers predominantly rely on epidemiological investigations and contact tracing data. These approaches typically involve identifying infector-infectee pairs through detailed interviews and then calculating the time difference between their symptom onsets. A systematic review and meta-analysis of COVID-19 serial intervals found a pooled estimate of approximately 5.19-5.40 days based on data from the early pandemic phase [24]. These estimates, however, demonstrated considerable heterogeneity across studies, reflecting methodological differences and varying transmission contexts.

The effectiveness of traditional contact tracing varies significantly based on implementation. A modelling study comparing contact tracing methods found that cluster tracing (combining forward tracing with cluster identification) reduced transmission by up to 62% when implemented with quarantine of contacts, outperforming both forward and extended tracing methods [9]. However, the same study highlighted that effectiveness was highly dependent on case-ascertainment rates and compliance levels, with performance dropping substantially under low ascertainment scenarios.

Table 1: Comparison of Serial Interval Estimates from COVID-19 Studies

| Study Reference | Study Region | Time Period | Sample Size | Mean Serial Interval (Days) | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nishiura et al. [24] | Multiple | Up to Feb 2020 | 28 | 4.7 | 3.7 - 6.0 |

| Du et al. [24] | China | Jan-Feb 2020 | 468 | 3.96 | 3.53 - 4.39 |

| Li et al. [24] | Wuhan | Up to Jan 2020 | 6 | 7.5 | 4.1 - 10.9 |

| Ki [24] | Korea | Up to Jan 2020 | 7 | 6.3 | 4.1 - 8.5 |

| Zhang et al. [24] | China | Jan-Feb 2020 | 35 | 5.1 | 1.3 - 11.6 |

| Zhao et al. [24] | Hong Kong | Jan-Feb 2020 | 21 | 4.4 | 2.9 - 6.7 |

| Ganyani et al. [24] | Singapore | Jan-Feb 2020 | 27 | 5.2 | 3.6 - 7.6 |

Genomic Epidemiology Framework

Genomic epidemiology offers an alternative framework for estimating serial intervals without requiring direct knowledge of transmission pairs, instead using virus sequences to infer who infected whom [22]. This approach constructs "transmission clouds" of plausible infector-infectee pairs based on genomic distance and symptom onset timing, then samples plausible transmission networks to estimate serial interval distributions while accounting for incomplete sampling through a mixture model.

This method demonstrated that cluster-specific serial intervals can vary estimates of the effective reproduction number by a factor of 2-3, highlighting the importance of context-specific parameter estimation [22]. The approach also revealed systematic differences in transmission dynamics across settings, with shorter serial intervals observed in schools and meat processing plants compared to healthcare facilities, suggesting different transmission patterns or ascertainment biases in these environments [22].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Estimation Methods

| Method Characteristic | Traditional Contact Tracing | Genomic Epidemiology Framework |

|---|---|---|

| Data Requirements | Detailed exposure histories from contact tracing | Viral sequences and symptom onset times |

| Sampling Assumptions | Often assumes complete sampling of transmission pairs | Explicitly accounts for incomplete sampling through mixture model |

| Key Advantages | Direct observation of transmission pairs; Established methodology | Does not require resource-intensive contact tracing; Provides high-resolution, cluster-specific estimates |

| Key Limitations | Resource-intensive; Privacy concerns; Vulnerable to recall bias | Requires sequencing infrastructure and expertise; Computational complexity |

| Contextual Flexibility | Limited by quality of contact tracing data | Can be applied across various transmission settings and sampling scenarios |

| Validation Approaches | Comparison with known transmission pairs; Epidemiological plausibility | Genomic validation; Simulation studies; Comparison with contact tracing data |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Genomic Estimation of Serial Intervals

The genomic epidemiology framework for serial interval estimation involves a multi-step process that integrates virological, epidemiological, and statistical approaches [22]:

Sequence Data Processing and Cluster Identification: Whole-genome SARS-CoV-2 sequences are obtained from cases and processed through quality control measures. Cases are grouped into transmission clusters based on genomic similarity and epidemiological links, with clusters defined as groups of cases with minimal genomic differences and plausible epidemiological connections.

Transmission Cloud Construction: For each cluster, researchers create a "transmission cloud" containing all plausible transmission pairs that meet predetermined criteria for genomic distance and temporal relationship between symptom onset times. This step acknowledges uncertainty in direct transmission links while incorporating biological constraints on plausible transmission pairs.

Network Sampling and Parameter Estimation: From the transmission cloud, multiple plausible transmission networks are sampled, with each infectee assigned an infector with probability inversely proportional to their genomic and symptom onset time distance. For each sampled network, a mixture model is fitted to estimate the serial interval distribution parameters, accounting for both direct transmission and transmission through unsampled intermediate cases. Finally, estimates are combined across all sampled networks to generate cluster-specific serial interval distributions.

Enhanced Contact Tracing for Cluster Detection

England's Enhanced Contact Tracing (ECT) programme implemented a systematic approach to cluster detection that combined exposure data from routine contact tracing with genomic validation [13]. The methodology involved:

Exposure Data Collection: During routine contact tracing for COVID-19, cases were interviewed about their exposures during the pre-symptomatic period (3-7 days before symptom onset). Data included locations visited, nature of activities, and timing of exposures.

Algorithmic Cluster Identification: Exposure clusters were identified by algorithmically matching two or more cases reporting attendance at the same event or location, using postcode matching and event categorization within a 7-day rolling window. This systematic approach allowed for detection of potential transmission events that might be missed through conventional forward contact tracing alone.

Genomic Validation: The genetic validity of exposure clusters was assessed by examining whether clusters contained two or more cases from different households with identical viral sequences, providing molecular evidence for shared transmission events. This validation step confirmed that approximately 25% of algorithmically identified exposure clusters represented genuine transmission events [13].

Risk Assessment and Public Health Action: Validated clusters underwent risk assessment by local public health teams to inform targeted interventions. Multivariable analysis identified that exposure clusters occurring in workplaces (aOR = 5.10) and educational settings (aOR = 3.72) were most strongly associated with genetic validity, guiding resource allocation for cluster investigation and management [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Transmission Cluster Studies

| Research Reagent / Tool | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Whole-genome Sequencing Platforms | Generation of complete viral genetic sequences | Genomic cluster identification; Mutation tracking; Transmission link validation [22] [13] |

| Phylogenetic Analysis Software | Reconstruction of evolutionary relationships between viral sequences | Inference of transmission chains; Identification of cryptic transmission; Estimation of evolutionary rates [22] |

| Contact Tracing Data Systems | Structured collection and management of exposure and contact information | Identification of potential transmission pairs; Exposure cluster detection; Epidemiological linkage assessment [9] [13] |

| Statistical Mixture Models | Estimation of parameters accounting for multiple transmission scenarios | Serial interval estimation with unsampled cases; Correction for incomplete sampling; Uncertainty quantification [22] |

| Network Analysis Algorithms | Mining relationships between transmission clusters | Identification of superspreading events; Cascade propagation analysis; Intervention targeting [25] |

| Genomic Distance Metrics | Quantification of genetic differences between viral isolates | Determination of plausible transmission pairs; Cluster definition; Outbreak boundary delineation [22] [13] |

Validation of Transmission Clusters

The integration of multiple data streams and methodologies significantly enhances the validation of transmission clusters. Research demonstrates that genomic validation serves as a robust approach for confirming epidemiologically-identified clusters, with studies reporting that approximately 25% of exposure clusters identified through enhanced contact tracing showed genetic evidence of shared transmission events [13]. This integration of epidemiological and genomic data provides a more comprehensive understanding of transmission dynamics than either approach could deliver independently.

Cluster characteristics significantly influence validation outcomes. Analyses reveal that workplace and educational settings show stronger associations with genetically valid clusters compared to other environments, highlighting the importance of context in transmission cluster validation [13]. Additionally, the size of exposure clusters and the timing of case detection serve as important predictors of validation success, enabling more efficient prioritization of public health resources.

Methodological innovations continue to advance cluster validation capabilities. The development of algorithms for mining relationships between transmission clusters enables the identification of superspreading events and cascade propagation patterns across multiple linked clusters [25]. These approaches facilitate a more comprehensive understanding of outbreak dynamics beyond individual clusters, revealing patterns of spread across communities and informing targeted intervention strategies.

The field of disease cluster analysis has undergone a profound transformation, evolving from simple descriptive maps to sophisticated computational algorithms that identify outbreaks with increasing speed and precision. Spatial epidemiology, now a cornerstone of public health, was famously exemplified by John Snow's 1854 cholera map, which visually identified a contaminated water pump on Broad Street in London as the outbreak source [26]. For more than a century, the geographical distribution of disease was primarily analyzed using thematic maps with darker colors indicating higher case concentrations—an approach easily misled by visual misclassification and the omission of critical temporal factors [26]. The integration of geographic information systems (GIS) has since enabled a more nuanced understanding of the relationships among agent, host, and environment [26].

In recent decades, this evolution has accelerated with the adoption of temporal clustering algorithms, phylogenetic methods, and mathematical modeling, fundamentally enhancing our ability to detect and interpret infectious disease transmission clusters. This progression mirrors a broader shift in public health surveillance from reactive documentation to proactive intervention, where the primary goal is the early detection of aberrant case patterns to trigger timely public health responses [26]. This guide objectively compares the performance and methodologies of key clustering approaches that have shaped the modern landscape of disease surveillance, with a particular focus on their validation within contact tracing research frameworks.

Comparative Analysis of Clustering Methodologies

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, strengths, and limitations of the major classes of cluster analysis methods used in disease surveillance.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Disease Cluster Analysis Methodologies

| Method Category | Representative Tools | Core Clustering Principle | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temporal Aberration Detection | Historical Limit, CUSUM, Moving Average [26] | Identifies case counts exceeding a statistical baseline or threshold [26] | Simple implementation; provides early warning signals; some variants (e.g., CUSUM) require little historical data [26] | Baseline can be skewed by past large outbreaks; may produce over-alerts; requires verification [26] |

| Genetic Distance-Based | HIV-TRACE, MicrobeTrace [27] [28] | Groups sequences with pairwise genetic distances below a user-defined threshold [27] | Computationally fast; generalizable across pathogens; does not assume a transmission tree [27] | Dependent on an arbitrary distance threshold; no penalty for unrealistic numbers of introductions [27] |

| Phylogenetic Heuristic | ClusterTracker [27] | Uses ancestral trait inference and heuristics to assign cluster membership from a phylogeny [27] | Designed for scalability on large datasets (e.g., millions of sequences) [27] | No correction for biased sampling; clusters constrained to a single region [27] |

| Phylogenetic Model-Based (Maximum Likelihood) | Nextstrain's augur [27] | Models trait migration (e.g., location) as a continuous-time Markov process along a time-scaled phylogeny [27] | Represents a balance between simplistic and complex models; widely used for live outbreak monitoring [27] | Region does not influence tree reconstruction; complicated to correct for sampling bias [27] |

| Phylogenetic Model-Based (Bayesian) | BEAST [27] | Co-infers phylogeny and migration history in a Bayesian framework, allowing traits to influence tree structure [27] | Accounts for phylogenetic uncertainty; considered highly robust for scientific inference [27] | Computationally intensive; does not scale well with many samples or regions [27] |

| Threshold-Free Phylogenetic | Phydelity [29] | Identifies groups of sequences more closely related than the ensemble distribution without a fixed distance threshold [29] | Eliminates need for arbitrary cutpoints; identifies monophyletic and paraphyletic clusters; high purity in simulations [29] | Interpretation limited to fully connected transmission networks without directionality [29] |

Performance Benchmarking and Empirical Concordance

The theoretical differences between methods lead to measurable variations in their outputs. Empirical comparisons are essential for understanding these discrepancies and selecting the right tool for a given public health scenario.

Concordance Across HIV-1 Molecular Cluster Methods

A study comparing 12 analytical approaches for identifying HIV-1 transmission clusters revealed significant variability in outcomes depending on the method and parameters used [28]. The study evaluated clustering based on topological support (a measure of confidence in tree branches) and genetic distance thresholds (e.g., 0.015 substitutions/site for strict criteria) [28].

Table 2: Performance of Selected Methods on an HIV-1 Dataset (n=1886 sequences)

| Method | Proportion of Sequences Clustered (Strict Thresholds) | Proportion of Sequences Clustered (Relaxed Thresholds) | Number of Clusters (Strict Thresholds) | Number of Clusters (Relaxed Thresholds) | Mean Concordance with Other Methods (Strict Thresholds) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-TRACE | 36% | Not Specified | 172 | Not Specified | 65% |

| RAxML | 22% | 38% | 156 | 223 | 88% |

| IQ-Tree (ultrafast) | 30% | 54% | 187 | 234 | 86% |

| PhyML aLRT | 24% | 54% | 167 | 234 | 86% |

| MEGA | 22% | 38% | 156 | 223 | 82% |

Key findings from this benchmarking include:

- Distance threshold was the dominant factor influencing clustering proportions, more so than topological support [28].

- Model-based methods (e.g., RAxML, IQ-Tree) generally clustered fewer sequences than the distance-based HIV-TRACE under strict thresholds, but often more under relaxed thresholds [28].

- Concordance between methods was variable. While some method-pairs agreed on over 90% of clustered sequence pairs, others, like MEGA and HIV-TRACE, shared as few as 17% of pairs under strict thresholds [28].

- The authors concluded that no single method is universally superior, and the choice of analytical approach should be tailored to the specific public health goal and epidemic context [28].

Performance on Bacterial and Viral Outbreak Case Studies

A separate comparison of four methods on real-world bacterial (Klebsiella aerogenes) and viral (SARS-CoV-2) outbreaks further highlighted methodological differences [27]. All methods (HIV-TRACE, ClusterTracker, Nextstrain's augur, and BEAST) successfully identified a singular, monophyletic transmission cluster for the 15-case K. aerogenes hospital outbreak [27]. However, the HIV-TRACE cluster was the least specific, including the 15 outbreak strains plus one unlinked hospital strain and 14 other context strains from the same region [27]. In contrast, the phylogenetic methods defined the cluster more strictly as the monophyletic clade of the 15 outbreak cases, demonstrating higher specificity [27].

This illustrates a key trade-off: distance-based methods like HIV-TRACE can be highly sensitive but may lack specificity, while phylogenetic methods can provide a more epidemiologically plausible cluster boundary but may require more computational expertise.

Experimental Protocols for Cluster Validation

Protocol for Phylogenetic Cluster Analysis with Phydelity

Phydelity is a threshold-free algorithm designed to identify putative transmission clusters from a phylogenetic tree without relying on arbitrary genetic distance thresholds [29].

Detailed Methodology:

- Input Preparation: The input is a phylogenetic tree, typically inferred from pathogen genome sequences.

- Calculate Maximal Patristic Distance Limit (MPL):

- For each sequence tip in the tree, compute the patristic distances to its closest k-neighbouring tips (including itself).

- Autoscale the k parameter to find the largest value that still yields a distribution of low divergence among neighbours.

- The MPL is calculated as:

MPL = μ¯ + σ, whereμ¯is the median of this kth core distance distribution andσis a robust estimator of its scale [29].

- Evaluate Putative Clusters: Every internal node

iin the tree is considered a putative cluster. Its within-cluster diversity, measured by the mean pairwise patristic distance (μi) of its descendant tips, is evaluated. Ifμiis less than the MPL, the node is considered for clustering [29]. - Dissociate Distant Sequences: The algorithm dissociates (prunes) distantly related subtrees from putative clusters to ensure all internal and tip nodes within a cluster have a mean pairwise nodal distance ≤ MPL [29].

- Integer Linear Programming (ILP) Optimization: An ILP model is run to find the clustering configuration that assigns sequences to the fewest number of clusters possible while satisfying the relatedness criteria. This favors the designation of larger, well-supported clusters [29].

- Output: The final output is a set of putative transmission clusters, interpreted as fully connected networks of likely transmission pairs [29].

Protocol for Benchmarking Multiple Clustering Tools

The comparative study on HIV-1 clusters provides a robust framework for benchmarking method performance and concordance [28].

Detailed Methodology:

- Dataset Curation: A set of 1886 HIV-1 pol sequences from Rhode Island (2004–2018) was compiled.

- Method Selection and Parameterization: Twelve different analytical approaches were selected, including model-based phylogenetic methods (e.g., RAxML, IQ-Tree) and the distance-based HIV-TRACE. Each method was run across a matrix of 49 different parameter combinations, varying topological support (0.00 to 0.95) and genetic distance thresholds (0.000 to 0.045 substitutions/site) [28].

- Define Cluster Criteria: Two specific scenarios were defined for focused comparison:

- Strict Thresholds: Topological support ≥ 0.95 and genetic distance ≤ 0.015 substitutions/site.

- Relaxed Thresholds: Topological support between 0.80–0.95 and genetic distance between 0.030–0.045 substitutions/site [28].

- Performance Metrics Calculation:

- Clustering Proportion: The proportion of the total 1886 sequences assigned to any cluster was calculated for each method and threshold.

- Concordance Analysis: For each pair of methods, the concordance was measured in three ways:

- Sequence Pair Concordance: The proportion of pairs of sequences that were grouped together in a cluster by both methods.

- Identical Cluster Concordance: The proportion of clusters identified by one method that were exactly identical to clusters found by another method.

- Non-clustered Sequence Concordance: The proportion of sequences not assigned to any cluster that were agreed upon by both methods [28].

- Robustness Testing: To ensure robustness, key steps like phylogenetic reconstruction with RAxML were repeated 100 times with different random seeds to measure variance in the resulting cluster proportions [28].

Integration with Contact Tracing for Cluster Validation

Contact tracing (CT) serves as a critical ground-truthing mechanism for validating molecularly inferred transmission clusters. It is defined as the identification, evaluation, and management of people exposed to a disease to prevent subsequent transmission [1]. The effectiveness of CT as a public health intervention creates a feedback loop, where clustering algorithms identify potential outbreaks, and contact tracing investigations confirm or refute these putative transmission links [26] [1].

Mathematical models, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, have explicitly parameterized CT to evaluate its impact on transmission dynamics. A systematic review found that 49.1% of such models were compartmental models (often placing traced contacts in a separate compartment), 34% were agent-based models, and 9.4% used branching processes [30]. These models demonstrate that when integrated with quarantine, CT acts at both individual and population levels, leading to earlier diagnosis and a decrease in the effective reproduction number (Re) of an outbreak [30]. This modeled impact aligns with the goal of phylogenetic cluster detection, which is to find groups of sequences linked by direct transmission or shared risk factors that represent active transmission chains [31] [29].

However, a significant challenge is that standard phylogenetic clustering methods assume homogeneous transmission dynamics, while real-world transmission clusters exhibit dynamic behavior over time [31]. A study evaluating phylogeny-based tools on simulated dynamic clusters found their combined sensitivity and specificity to be low, indicating a pressing need for novel methods that can reliably detect individuals linked by changing transmission dynamics [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

The following table details key computational tools and data resources essential for conducting cluster analysis in disease surveillance.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Solutions for Cluster Analysis

| Tool/Resource Name | Category/Type | Primary Function in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| HIV-TRACE [27] [28] | Software Tool (Distance-Based) | Detects transmission clusters by grouping sequences with genetic distances below a user-defined threshold; often applied to HIV but generalizable. |

| Phydelity [29] | Software Tool (Phylogenetic) | Identifies putative transmission clusters from a phylogenetic tree without requiring an arbitrary genetic distance threshold. |

| Nextstrain (augur) [27] | Bioinformatics Pipeline | Builds time-scaled phylogenies, infers ancestral traits, and tracks pathogen spread in real-time for public health surveillance. |

| BEAST [27] | Software Package (Bayesian Evolutionary Analysis) | Co-infers phylogenetic trees, evolutionary rates, and ancestral history in a Bayesian framework, accounting for uncertainty. |

| ClusterTracker [27] | Software Tool (Phylogenetic Heuristic) | Identifies clusters corresponding to introduction events on very large phylogenies (e.g., millions of SARS-CoV-2 sequences). |

| Context Genomes [27] | Reference Data | A set of pathogen sequences from general circulation, used as a background for comparison to determine if cases are more closely related to each other than to circulating strains. |

| Simulated Epidemic Datasets [29] [28] | Benchmarking Data | Computer-generated outbreaks with known transmission history, used to validate and benchmark the performance of clustering algorithms. |

Logical Workflow for Cluster Analysis and Validation

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow of data processing, cluster analysis, and validation that is central to modern disease surveillance.

Diagram 1: Integrated workflow for transmission cluster analysis and validation, showing how molecular data and contact tracing interact.

The evolution of cluster analysis in disease surveillance reveals a clear trajectory from simple spatial and temporal methods toward integrated, phylogenetically-informed frameworks. The empirical data shows that no single clustering algorithm is universally superior; each carries distinct strengths and limitations that make it suitable for different public health scenarios [28]. Distance-based methods like HIV-TRACE offer speed and simplicity, while model-based phylogenetic tools like BEAST provide statistical robustness at a computational cost. Threshold-free algorithms like Phydelity represent a significant advance in reducing subjective parameter choices [29].

A critical finding from recent research is the low concordance between different clustering methods and their current inability to fully capture the dynamic nature of transmission clusters [31] [28]. This underscores the necessity of using contact tracing as a validation scaffold to ground-truth computationally derived clusters [1]. The future of cluster analysis lies in the development of more dynamic phylogenetic methods and the tighter integration of molecular data with traditional epidemiological fieldwork. This synergy will be essential for transforming cluster detection from a descriptive exercise into a predictive, intervention-driven science capable of disrupting transmission chains in real-time.

Integrating Methodologies: Contact Tracing and Molecular Cluster Analysis

Contact tracing is a cornerstone public health intervention for breaking chains of transmission during infectious disease outbreaks. While digital tools have expanded tracing capabilities, traditional methods remain fundamental to epidemic response. This guide provides a systematic comparison of three traditional contact tracing methodologies—forward, backward, and cluster tracing—focusing on their operational mechanisms, effectiveness metrics, and implementation protocols. The analysis is situated within the broader research context of validating transmission clusters, a critical process for verifying epidemiological linkages identified through contact tracing activities. Understanding the comparative performance of these approaches provides researchers and public health professionals with evidence-based guidance for selecting context-appropriate strategies during outbreak responses.

Conceptual Frameworks and Definitions

Forward contact tracing, the most widely implemented method, identifies and manages individuals potentially infected by a known index case. This approach aims to interrupt onward transmission by identifying "child cases" (persons infected by the index case) [32] [2]. Operational protocols typically define the exposure window based on the pathogen's infectious period; for COVID-19, this commonly included contacts exposed from 2 days before symptom onset or diagnosis until case isolation [9] [2].

Backward contact tracing (also called bidirectional when combined with forward tracing) identifies the source of infection and individuals potentially infected by the same source. This method aims to identify "parent cases" (the infector of the index case) and "sibling cases" (others infected by the same parent case) [32] [2]. This approach is particularly valuable for pathogens exhibiting superspreading dynamics, as it efficiently uncovers transmission clusters [33] [2].

Cluster tracing integrates forward tracing with systematic cluster identification and investigation. This method focuses on detecting and containing transmission events involving multiple cases linked to specific settings or events [9] [11]. Rather than solely tracking individual transmission chains, cluster tracing employs analytical techniques to identify epidemiological linkages across cases, enabling targeted interventions in high-transmission settings [11].

The diagram below illustrates the conceptual framework and logical relationships between these three contact tracing methods within an outbreak investigation context.

Figure 1: Conceptual Framework of Contact Tracing Methodologies. This diagram illustrates the operational workflows and logical relationships between forward, backward, and cluster tracing methods in outbreak investigation.

Comparative Effectiveness Analysis

The effectiveness of contact tracing methods varies significantly based on operational context, including case ascertainment rates, contact management strategies, and resource availability. The following tables summarize quantitative performance data from modeling studies and empirical evaluations.

Table 1: Comparative Effectiveness of Tracing Methods Under Different COVID-19 Scenarios (Modelling Data)

| Tracing Method | Low Case-Ascertainment with Testing | Low Case-Ascertainment with Quarantine | High Case-Ascertainment with Testing | High Case-Ascertainment with Quarantine |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forward Tracing | 12% transmission reduction | 46% transmission reduction | 20% transmission reduction | Equally effective (All methods bring Reff <1) |

| Extended/Backward Tracing | 17% transmission reduction | 50% transmission reduction | 23% transmission reduction | Equally effective (All methods bring Reff <1) |

| Cluster Tracing | 22% transmission reduction | 62% transmission reduction | 26% transmission reduction | Equally effective (All methods bring Reff <1) |

| Provider Costs (per infection prevented) | US$2,944-$5,227 | Below US$4,000 | US$1,873-$3,165 | Below US$800 |

Source: Adapted from [9]

Table 2: Empirical Performance Metrics from Contact Tracing Implementation

| Performance Metric | Forward Tracing | Backward/Bidirectional Tracing | Cluster Tracing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Additional Cases Identified | Baseline | 42% more cases than forward alone [2] | Highly variable based on setting |

| Optimal Tracing Window | 2 days before symptom onset | 6-7 days before symptom onset [33] [2] | Event-based investigation |

| Impact on Effective Reproduction Number (Reff) | Moderate reduction | 85-275% improvement over forward tracing [33] | Largest reduction in high-cluster scenarios [9] |

| Resource Efficiency | Higher testing/quarantine requirements | Fewer tests and shorter quarantine per identified case [2] | Highly efficient when clusters are correctly identified |

| Precision (Phylogenetic Validation) | Not directly assessed | 34.6% precision in identified transmission pairs [8] | Not directly assessed |

Contextual Factors Influencing Effectiveness

The comparative performance of tracing methods depends heavily on several contextual factors. Case ascertainment rates significantly impact effectiveness; under high ascertainment with quarantine, all methods can bring the reproduction number below unity, stopping transmission early [9]. Pathogen characteristics also influence method selection; backward tracing proves particularly valuable for pathogens with superspreading potential, as identifying source cases and events can efficiently break multiple transmission chains simultaneously [33] [2]. Operational resources determine feasibility; while bidirectional tracing with an extended window shows superior effectiveness, it demands greater investigative capacity and rapid response capabilities [9] [33].

Experimental Protocols and Validation Methodologies

Transmission Network Modeling Protocol

Objective: To quantitatively compare the effectiveness of forward, backward, and cluster tracing methods under varied epidemic conditions [9].

Methodology Overview:

- Model Structure: Develop a stochastic transmission network model incorporating population contact structure and disease characteristics.

- Intervention Arms: Simulate three tracing approaches: forward tracing (2 days before case isolation), extended tracing (16 days before isolation), and cluster tracing (combining forward tracing with cluster identification).

- Scenario Analysis: Construct combinations of operational scenarios: (1) low vs. high case-ascertainment rates, and (2) testing vs. quarantine of contacts.

- Outcome Measures: Quantify impact on disease transmission (reproduction number, infection rates) and resource utilization (cost per infection prevented).

Implementation Details:

- Case isolation occurs after diagnosis, preventing further transmission.

- Contacts are identified, notified, and managed according to scenario specifications (testing or quarantine).

- Cluster investigation identifies epidemiological links between cases and targets interventions to shared exposure settings.

- Model calibration uses empirical contact tracing data and disease parameters.

This protocol enables direct comparison of method performance while controlling for contextual variables, providing robust evidence for public health decision-making [9].

Phylogenetic Validation Framework

Objective: To assess the precision of contact tracing by quantifying the proportion of identified transmission pairs supported by genomic evidence [8].

Methodology Overview:

- Sample Collection: Obtain pathogen genetic sequences from confirmed cases and their identified contacts.

- Molecular Analysis: For cases infected with the same variant, perform time-scaled phylogenetic analysis to determine if case-contact pairs cluster together.

- Precision Calculation: Compute precision as the proportion of epidemiologically-linked pairs not contradicted by genomic analysis.

Implementation Details:

- Genetic Sequencing: Amplify and sequence target gene regions (e.g., pol gene for HIV, spike protein for SARS-CoV-2).

- Phylogenetic Reconstruction: Construct phylogenetic trees using maximum likelihood or Bayesian methods with appropriate evolutionary models.

- Cluster Identification: Define molecular clusters using genetic distance thresholds and bootstrap support values.

- Concordance Assessment: Compare epidemiological linkages identified through contact tracing with molecular clustering patterns.

This validation framework provides critical quality assessment for contact tracing programs, identifying potential limitations in interview methods, contact identification, or data interpretation [8] [34].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Analytical Tools for Contact Tracing Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Application | Specific Function | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pathogen Genetic Sequences | Phylogenetic validation | Enable molecular comparison of isolates from different cases | HIV-1 pol gene sequencing [34]; SARS-CoV-2 whole genome sequencing [8] |

| Evolutionary Analysis Software | Molecular cluster identification | Reconstruct transmission trees and identify genetically similar isolates | HYPHY (gene distance calculation) [34]; FastTree (phylogenetic reconstruction) [34] |

| Network Visualization Tools | Data interpretation and presentation | Illustrate transmission networks and relationships between cases | Cytoscape (molecular network visualization) [34] |

| Transmission Modeling Platforms | Intervention comparison | Simulate disease spread and evaluate counterfactual scenarios | Stochastic branching process models [33]; Network transmission models [9] |

| Epidemiological Investigation Protocols | Field data collection | Standardize case interviews, contact identification, and data recording | Structured questionnaires, contact elicitation methods, outbreak investigation guidelines [11] |

Implementation Considerations

Operational Adaptability

Successful contact tracing systems maintain flexibility to adapt methods to evolving outbreak conditions. Research indicates that rather than relying on a single approach, health authorities should develop capacity to switch strategies based on resource availability and epidemiological situation [9] [11]. During COVID-19, East and Southeast Asian countries demonstrated this adaptability by implementing multi-faceted approaches that combined direct contact identification, source investigation, and cluster analysis tailored to local transmission patterns [11].